Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 65

August 30, 2016

The wordless beauty of Pan-Pan

There are no words in Pan-Pan—just bubbling variations of boops and beeps. After crash landing on Pan-Pan’s colorful low-poly world, you’ll be introduced to a bunch of little dudes with bushy ‘staches. They’ve come to your aid after the crash, and despite there being a language barrier, they’re trying to fix your ship. But you’ll have to help. Scattered through Pan-Pan’s knotted puzzles are the pieces needed to fuel your ship and head home.

Curiosity is the language in Pan-Pan. It’s a curiosity powered by the world’s design. Developer Spelkraft uses a visual language to express its intentions; it’s not always obvious, but that’s the point. You’re not meant to solve Pan-Pan’s puzzles in 20 minutes. It’s not always clear where to start: at times, you’ll have to go at it with brute force, wandering around with your stick, hitting everything in your path. Click anything and everything until something starts to make sense. And most of the time, Pan-Pan’s design language is enough to give the clues needed to solve its puzzles, for something to make sense.

A cleverly-placed vase. An apple core tossed to the side.

One of the first puzzles I encountered—and it might be different for you, as Pan-Pan lets you untangle its obstacles as you choose to—required me to work myself through a graveyard-like maze of tombstones. Each tombstone has an eye, or doesn’t. Some eyes are sleepy with drooped lids. Some eyes are caffeine-fueled and wide awake. And some have no eyes. A garden of tombstones in front of the maze serves as an environmental primer for players; it doesn’t give the exact path, but it does give enough information to solve the puzzle. Sometimes you won’t have all the information available to solve a puzzle, though. You’ll have to wander more. But the clues are there, and when you get it, you’ll get it.

Visual cues of this kind are strewn across Pan-Pan’s candy-colored world. For the most part, they work; many of the cues embedded in the environment are important in solving the puzzles. Each area is distinct in its color and mood, so finding an object outside that visually aligns with that area may provide clues as to where it’s to go. There are moments, though, when an object’s significance can be muddled or inflated.

Take the forest area where you meet a strange little woodland fellow as example. This particular bit of land sticks out from a design perspective—visually, it’s much more green than the rest of the space. Fir trees dot the landscape. There’s a pond teeming with life. An owl-like creature watches you as you move through the environment. Fireflies flit around. There’s a tent, too—there’s a character outside, with the same suspiciously-pointed legs as you. These visual clues seem to belong to the game’s puzzle language at first glance but that’s not necessarily the case. I spent more time than I’d like to admit trying to reach the owl and collecting the fireflies; pursuits that the rest of the game’s puzzles would indicate were my goals in this area. But that wasn’t the case.

I wanted to keep exploring the world of Pan-Pan. Spelkraft is successful in creating a place I want to learn to live in, even if it’s frustrating at times. The clues are there—study the language, and you’ll see it. A cleverly-placed vase. An apple core tossed to the side. Nothing means nothing in Pan-Pan and so my time spent wandering in Pan-Pan wasn’t time wasted. It’s time spent learning a design language and that takes time. It’s trial and error; there are hiccups and missteps. Get curious and take your time. There’s no rush, really.

Pan-Pan is available on Steam for $12.99.

The post The wordless beauty of Pan-Pan appeared first on Kill Screen.

Look upon the terror of Pokémon Bones

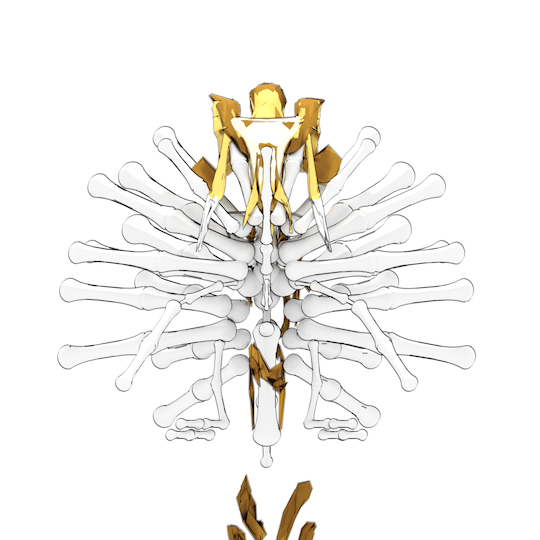

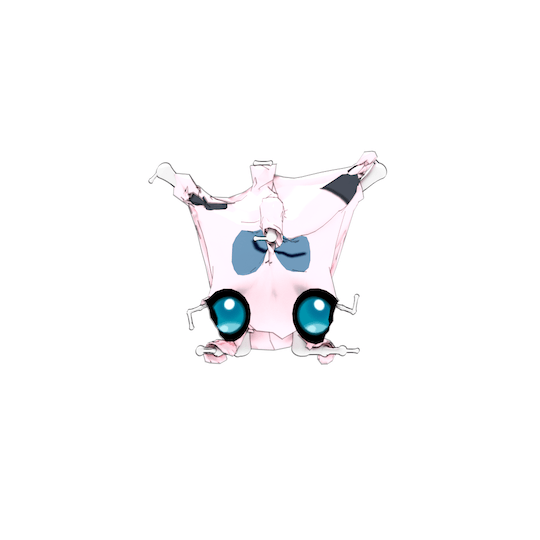

Pokémon don’t have internal organs. At least, that’s what Miles Peyton—a Fine Arts and Computer Science student at Carnegie Mellon—found out when he pulled the skin back on different character models from Pokémon X and Pokémon Y (2013) exposing “skin balloons without flesh or internal organs.”

Peyton told me his project, appropriately named Pokémon Bones, is about how 3D models are just hollow, balloon-like representations of things. Using the site The Models Resource, a community-run website where users upload models and assets they’ve ripped from games, he wanted to look at the armature of each Pokémon, the skeleton that determines how a model will be able to move around. From there, he got creative.

“I’d drape the Pokémon over its bones”

“Normally the armature is invisible,” he explained, “so I wrote a script to replace the invisible bones with visible bones. After I had a visible skeleton, I’d drape the Pokémon over its bones.” The finished product is fascinating, albeit a little macabre. Each Pokémon has its own individually built skeleton, unique to its physiology. Some Pokémon only have a couple of bones, such as Metapod, while others, like in the case of Sandslash (shown below), have more complex structures making up their in-game model.

The project, Peyton tells me, was inspired by artists like Brody Condon and Cory Arcangel, both of which have made videogame art using games such as Half-Life (1998) and Super Mario Bros. (1985), respectively. He also cites Michael Craig-Martin’s 2015 book, “On Being An Artist” and his line drawings of everyday objects.

Pokémon Bones isn’t Peyton’s first videogame-inspired art piece—earlier this year he released a piece revolving around Utada Hikaru’s song “Simple and Clean,” the theme from Kingdom Hearts (2002). But Pokémon Bones is his largest project to date, with over 100 Pokémon being featured in the piece. On why videogames inspire his work, Peyton said, “[I] had lots of formative social and aesthetic experiences in game worlds, so it’s kind of unavoidable.”

Currently, Peyton doesn’t plan to do anything similar with other games. He did tell me, however, about an upcoming project he’s working on where he simulates the formation of clouds. He plans to livestream this project in the coming months.

To keep up with Miles Peyton and his work, you can follow him on Twitter or visit his website.

The post Look upon the terror of Pokémon Bones appeared first on Kill Screen.

Cosmic Express will give you the opportunity to swear at cute space trains

There’s something magical about travelling by train. It’s something that participants in the yearly Train Jam—a 52-hour game jam set on a train ride between Chicago and San Francisco—try to harness to make games. Alan Hazelden’s latest game, Cosmic Express, has it origins in that very train jam, and is consequently a “puzzle game about planning the train route for the world’s most awkward space colony.”

Back in 2015, Hazelden found himself boarding for the 52-hour train journey less than 24 hours after releasing his game A Good Snowman Is Hard To Build for the PC. “In hindsight, perhaps it wasn’t the best idea in the world,” he said. “I spent a lot of time being distracted, worrying about the launch of that was going, but since the Wi-Fi on the train cuts out for long periods of time, I decided to prototype a train-related game for the jam.”

“People far too rarely have the opportunity to swear at a piece of train track”

That prototype was Train Braining, a prototype built in Puzzlescript that’s still available to play. I got to level three, before my sleep-addled brain refused to suss out the puzzles. Hopefully you’ll fare better. “Over a year later,” said Hazelden, “I was talking to Benjamin Davis about doing another project together, working with an artist this time.” Davis had previously worked with Hazelden on A Good Snowman Is Hard To Build. “We met many of the people from [French game collective] Klondike at GDC and they’re all incredibly talented people so we were excited to work with Tyu (Typhaine Uro) on a small project.”

The team threw a lot of different ideas into the mix before realizing they already had a great idea in Train Braining, and that the prototype was ripe for remaking. The plan was to improve the art, and more puzzles and mechanics, and “definitely more cute aliens,” according to Hazelden.

Cosmic Express has you building the train route for a space colony, with lots of alien colonists needing to be picked up and dropped off at their respective destinations. This sounds simple, but as anyone that’s ever tried to board a train in real life can tell you, train travel can be prone to unexpected problems. Here, the key challenge is that you start with space for only one alien at a time, you can’t cross the tracks over themselves, and thoughtlessly, the aliens themselves might not be in the most convenient of positions.

If you thought keeping the trains running on time would be easy, you’re mistaken. “People far too rarely have the opportunity to swear at a piece of train track because it can’t go there and pick up that alien and drop them off there because then there’s no space to go back and pick up *that* alien,” Hazelden said. Although I haven’t done my research, I’m willing to believe he’s right.

Hazelden draws comparisons between his earlier game Sokobond (2014) and Cosmic Express. “Where A Good Snowman focuses on one mechanic and does just that one thing really well,” Hazelden said, “with Sokobond and Cosmic Express it felt right to explore variants and similar possibility spaces. Planning out the order in which levels unlock is a tough problem when you have half a dozen.”

While Hazelden prototyped the game, he’s keen to highlight how invaluable his partnership with Davis and Tyu has been: Davis working on code and Uro on the game’s art style. The result is a cutesy puzzler that’s likely going to make you pull your hair out (if my adventures with the prototype are anything to go by), but the strength of the puzzle design should keep you crawling back for more.

Cosmic Express is coming soon to iPhone, iPad and Android. Find out more on its website.

The post Cosmic Express will give you the opportunity to swear at cute space trains appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Banner Saga 2 still goes at it hard

The world is breaking. This is what you’re told at the outset of The Banner Saga 2. It’s delivered in a sigh, an exhale, and carries with it the weight of responsibility you bear—not all of those entrusted to your care will make it through the ordeal. There’s an inevitable doom to the proceedings but your choices will give those that follow you a chance, at least. Those choices are there in the dialogue, in the small esoteric details of conversation, in the events that unfold, and in the combat that ensues. Decision-making is woven into the tapestry of play and it finds meaning in the story that unfurls before you.

Stoic, the studio behind The Banner Saga series, has made an odd choice in genre for laying out such a complex and fluid world, and one susceptible to change. These are tactical RPGs, a genre famed for its stringent compartmentalization rather than emotional resonance. Yet, in spite of the potential limitations that framework might present, The Banner Saga series goes beyond the seemingly unavoidable artifice of the genre to deliver an experience in which you feel for the characters. These characters grow, and when they die, you genuinely care for the loss of their personality.

Decision-making is woven into the tapestry of play

The first entry in The Banner Saga series did slog extremely well. Resources would dwindle as your party trudged through the thick snow, a ticking timer to starvation. And morale would slip not only when you lost fighters and clansmen, but also as your decisions adversely affected the plight of those who were now dependent on you. Depression was built into a system that rarely gave you an opportunity to rectify the situation.

That first game’s battles, too, were a nightmare. The turn-based nature of combat stretched time, dragging out the skirmishes. You’d chip away incrementally at the armor of your enemy, laboring to maneuver your characters about the grid. But there was a crushing inevitability to a blow wrought by the Dredge, that moment of impact given more meaning by the slowness of everything else occurring around you. This combat was routinely criticized for its repetitive nature but, to me at least, it was a beautifully if heftily-designed creation. It felt arduous, you felt tired playing it, and it compounded the feelings that were wrought from the game in its narrative stretches. Life is shitty for these people and you will get, at the very least, some sense of it.

Tom Bissell, in his book Extra Lives: Why Videogames Matter (2010), spoke about challenge being antithetical to narrative, a barrier to both the progression of story and emotional investment. In the case of that first game, though, he’s wrong. Through its combat, The Banner Saga (2014) gave you, however small, some insight into the situation—it managed to convey something of your party’s plight. But, in The Banner Saga 2, narrative is better integrated into the combat. Characters will appear, Dredge will lurch from the darkness, dialogue will play out, and the environment will shift opening up new, previously inaccessible areas. It makes for a more streamlined experience, one that turns out to be more engaging, but there was a graceful monotony to combat in the first game, a feeling that is lost this time round. It shouldn’t, in essence, be this enjoyable—it should aim to be more harrowing—and it’s this that detracts, ironically, from the narrative that is unfolding.

That isn’t to say that The Banner Saga 2 is a bad game. It’s not. At all. In fact, it develops many of the themes of the first game that elevated it above the usual fare of fantasy role-playing titles. Central to this is the idea of displacement. In this game, you play as either Rook or his daughter, Alette. Their village was wiped out by a party of Dredge—they have no home. Over the course of the game you travel to many destinations in search of refuge. Some are welcoming and some are hostile. But it’s never easy to attain hospitality—negotiation is always key. Throughout this journey you encounter many more displaced peoples whose homes have been ravaged by war. Smoldering settlements loom in the background, a common feature of the landscape, and often you are given the decision to help these people—to invite them into your party of refugees—or to leave them to fend for themselves in an openly hostile environment, at the mercy of a seemingly ravenous foe.

Stoic is extremely good at obscuring the potential outcome of your decision

Decision-making in the game is hard. Partly, this is down to Stoic’s mostly excellent writing; not only the depth of characterization, but the relationships between those characters. Near the beginning of the game, Iver attempts to comfort Alette, the newly appointed leader, with stories of her recently deceased father and long-deceased mother. “She made him smile; he made her laugh,” he says, in one of the game’s warmest exchanges. And as a woman of power in a deeply masculine world, Alette is subject to frequent challenges to her authority, but Stoic handles these encounters carefully and, on the whole, successfully. “What does she really know about getting us to Arberrang safely?” says one critic. “She should be looking for a husband, not telling me what to do.” Alette’s response is combative, asserting her power, while Oddleif, her friend and mentor, offers a smile in support. And like in the Kentucky Route Zero games, unchosen dialogue options are not necessarily wasted—they still give insight into the thought processes and psychology of the characters you are controlling. You may, in the climactic moments, wince through a decision as the relationships are stretched and tested.

The other big factor is that Stoic is extremely good at obscuring the potential outcome of your decision. There is no right or wrong, no good or bad. Decision-making is a fuzzy, imperfect affair, and you’re edging your way through this world as much as Alette is. You share her uncertainties. Near the beginning of the game, you come across a bank of driftwood on the river, obstructing your boats. I was impulsive—I chose to break through the barrier, figuring it better to do that than risk any time on land where my party was vulnerable. The hull of one of my boats cracked and we were forced to move to land anyway. Dredge descended and, after a long fight, we made it out alive. But not without losing men, women, supplies, and morale. Moments like this underscore the fate of your party and reinforce the irrefutable hopelessness of it all. There’s no respite and it grinds you down. You feel beaten throughout almost the whole of the game. But it’s a welcome change in tone from the power fantasies that typify the current videogame landscape.

There are occasional moments of relief, though. Generally, these come when you encounter the statues of fallen gods. As monuments of the past, they offer time for reflection, for stories to be passed around, and for laughter to take hold. Importantly, it’s a shared cultural artifact to bring your disparate party together in a world where day-to-day bonds are being broken. It’s moments like this that emphasize what’s been lost. Come morning, it’ll be back to the road.

Duality lies at the heart of The Banner Saga series. There’s the spreadsheet artifice of combat and character progression, and there’s the world that the art and story muster. The combat, this time round, might feel as if it’s pulling in a different direction to the story—unable to reinforce the narrative in the same way as the first game—but it doesn’t stop the game effectively exploring its story of displacement and asylum. It’s the decisions that bind the experience; enabling The Banner Saga 2 to transcend its videogame construct. You’re left with an experience that feels not only alive, but alive with the complexities of the real world.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post The Banner Saga 2 still goes at it hard appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 29, 2016

Try to fix NYC’s subway system in a new historical simulation game

I didn’t know much about Robert Moses before playing Confetti with the Brick Bats. The creators of the game, New York Game Center students Alexander King and Noca Wu, didn’t know much about him either. That is, not before Tim Hwang’s “Power Broker” contest, which offered cash prizes to those that could turn Robert Caro’s 1,336 page biography of Robert Moses into a game. And so that’s what they did.

However, the game started out differently: it was planned to be a strategy game about building. But the team soon realized, through Robert Heller—a friend that stepped in to advise and later write the game—that Moses wasn’t much of a builder. It turns out he was more of a shrewd politician and a Machiavellian political operator. Moses didn’t so much build as will the city into shape around him as he sat in his office, making phone calls and sending out letters with ferocity.

the first time many of the documents have been digitized

This is the feeling the team then looked to capture, and that desire birthed Confetti with the Brick Bats, a narrative adventure. “We wanted to immerse the player in the mindset of Robert Moses,” said King. “So the game puts the player in Moses’s office, listening to the music that Moses enjoyed, and seeing the same correspondence that came across his desk. Each document represents a course of action for the problem Moses is facing, and after they’ve picked three they see the results of their choices as a newspaper headline and article.” It plays like a visual novel and the choices it asks you to make lead to between 50-60 different headlines.

There are no outside influences to inform your decisions and no real way to ascertain exactly what will happen as a result of your actions. That doesn’t stop the game asking you to look through the documents for three of Moses’s biggest choices. “We applied for access to the Robert Moses papers at the New York Public Library,” King said. “We only scratched the surface of the collection. It’s 200 boxes in all and we went through a chunk of those and ended up finding so many historical documents relevant to the time.”

It’s these letters that you end up virtually pawing at in the game. Perhaps most exciting for history nerds like myself is that, in many cases, the letters you read in the game are the first time many of the documents have been digitized.

It’s knowing this that had me feel like a detective while I played the game myself, choosing between the less crappy option of several choices laid out on the virtual table in front of me—bearable only because I knew the only thing I was doing damage to was the world inside my browser. And thank god. If you’re into political intrigue, investigation, and historical documents, you know what to do.

You can play Confetti with the Brick Bats right now on itch.io for Mac and Windows.

The post Try to fix NYC’s subway system in a new historical simulation game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Odd noir adventure game Jazzpunk comes frolicking to PS4 soon

The adventure game most likely to puzzle your eyeballs with a noir-inspired pixel odyssey—Jazzpunk—is coming to PS4 on September 20th.

The trailer for the PS4 release is weird in that quintessentially Jazzpunk way; a combination of live-action shenanigans, a smidge of gameplay, and a dash of construction paper-looking papercraft in an atomic-age package. It sets the tone for the odd game that is 2014’s Jazzpunk, albeit re-released in a shiny updated package.

The version hitting PS4 virtual shelves is a “Director’s Cut,” and as Jesse Brouse, of Necrophone Games, puts it: “Some of the new content was resurrected from our faithful cutting-room floor, while others tidbits were decompressed fresh, straight out of our Brain.zip files! In either case, by distilling reams of precious User Data we’ve been able to strategically shoe-horn in the smattering of new content we’d always dreamed of—but didn’t know was scientifically plausible!”

“bizarre gadgets and deadly marital aids”

In addition to the new and culled content that will be a part of 2016’s Jazzpunk, the game will also feature an arena deathmatch mode inspired by weddings. Brouse promises “couch-friendliness” in the deathmatch modes, which will allow for a “gaggle of bizarre gadgets and deadly marital aids to help you tie the matrimonial noose with your friends.” Maps are Honeymoon Destinations, and characters play in a 2-4 player split screen while shooting each other with gatling guns made of tiered wedding cake and champagne corks.

Jazzpunk is already out on PC. You can find more information about the game at the Jazzpunk website.

The post Odd noir adventure game Jazzpunk comes frolicking to PS4 soon appeared first on Kill Screen.

The rise of VHS horror games

The introduction of VHS cassettes in the 1970s was a revolution in bringing horror closer to people. Two decades before, television became the primary medium for affecting public opinion, trumping newspapers and radio. This bore a generation eager to sit around a humming electronic box in their living rooms, allowing all kinds of foreign images to infiltrate their homes. But these broadcasts were typically newsreels and government-approved screenings—images under state control. VHS put more power to the viewer, who could decide what to watch and when, just by inserting a box-shaped pack of plastic into a tape player and letting its innards uncoil.

It wasn’t long until VHS led to new scares. These weren’t confined to the grody, bootleg horror titles that ambitious, sick-minded amateurs distributed in hopes of getting a name for themselves. It included urban legends of serial killers and haunted tapes. The term “snuff film” came about in the ’70s after the Manson family were reported to have recorded their murders on camera. The idea spread and inevitably got tangled up with VHS as it grew more popular—rumors were that any innocent-looking tape could house footage of an actual, brutal murder; you wouldn’t know until it was too late.

a motif for death through technology

Beyond that, VHS tapes were known for their degradation, as is the case with any analog media. You played a tape too much and it would begin to decay. The images would be interrupted with static grain and piercing scanlines that clambered all over the screen as if a creature teasing its prey. The affect of this, to most people, is annoying: your favorite film is ruined, and so you’d have to buy another copy of it. But for some it changed the nature of the images to something else. The distorted images became a motif for death through technology—the visible signs of data rot. The nightmares and ghost stories came soon after.

Since the heyday of VHS, it has become a reference point in horror due to its associations. VHS glitches and tapes of real murders are plots in many horror fictions of the ’90s and new millennium. And it hasn’t slowed down, either. Within the past couple of weeks we’ve had the new Resident Evil VII demo making use of found footage to build up its scares and a trailer for the reboot of The Ring, which, if you didn’t know, involves a spirit that kills anyone who watches a certain videotape.

But that’s not all. VHS horror seems to be a rising trend in videogames especially. It came about in some bigger horror games of the aughts but, in the past couple years, has began to sprout its ugly flower (of flesh and blood) in the realm of independent games. Below, we’ve outlined the most significant titles in this emerging sub-genre, including the earlier examples that started it off and the more recent ones keeping it going. Between them is a combination of grindhouse aesthetics, actual tape horrors, and scares found inside recorded footage.

Silent Hill 2

The internet doesn’t need another impassioned love letter to Silent Hill 2 (2001), so let’s be as brief as possible. A VHS tape—a snuff film, actually—features at the heart of the game’s Freudian nightmare. The entire thing leads to that tape, peeling back layers of repression and psychosis until the truth is revealed in tracking lines and white noise.

After the physical grind of playing Silent Hill 2, with its combative controls, alienating obtuse dialogue, and endless staircases, you may wonder what it can reveal to top the shit it’s already piled on you. Don’t worry. It’ll deliver.

Manhunt (purchase)

The kind of experiment Rockstar doesn’t bother with anymore, Manhunt (2003) was a loving homage to grindhouse and found footage horror; a sort of mashup of August Underground (2001) and The Running Man (1987). Playing it now, it seems juvenile and clunky; but on release it caught a whole boatload of that sweet, sweet public outcry, as if the sight of one polygonal convict shoving a broken bottle into another polygonal man’s throat, blood gushing out in great MS Paint gouts, could singlehandedly undermine society as we know it.

The game was clever to couch its violence in crackling, snowy surveillance footage, letting the player enact po-faced executions for the pleasure of The Director; and of course, their own sadistic impulses, thank you very much. It’s Funny Games (1997) without the didactic finger-pointing; it’s Hotline Miami (2012) without the style. It’s frankly not much fun, and that counts as some sort of coup. How many games have the balls to strip murder down to its pathetic, depraved bones?

Lone Survivor (purchase)

One of the hundred thousand videogames that would love to be compared to David Lynch and Silent Hill; one of the handful that earns it. Designed (and scored) by Jasper Byrne—who notably cut his teeth on a lo-fi demake of Silent Hill 2—Lone Survivor (2012) is a resolutely grimy horror game. It doesn’t feature actual VHS tapes; instead its grainy visuals evoke the degraded wrongness you might find on an unmarked cassette in an abandoned, smoke-yellowed apartment complex.

A man with a box on his head; a theater lined in rich blue curtains; copious pills; strange dreams; a disturbing party. Lone Survivor is filled with surreal curlicues that adorn its unreliable, hazy narrative, piling atop one another—but are they distractions? Clues? You’ll get answers, eventually, but you may not like them.

Hotline Miami (purchase)

Hotline Miami is desperate to feel dangerous. It may place you way above the action with its top-down view, but that’s only so you can better see the spread of bodies and blood once you’ve bludgeoned your way through the living. Everything is right up in your face—teeth bared—despite the lack of proximity.

But to achieve this effect the game’s creators had to find a way to make the pixel-art murder feel genuinely nasty. The tool they sliced it with? Grindhouse. Hotline Miami embraces its lo-fi aesthetic by borrowing a trick from Manhunt and framing its gory setpieces as a lone killer coaxed to decimate seedy street gangs. While the first game doesn’t go quite so far as having each massacre filmed on CCTV (as with Manhunt), the second one, Wrong Number (2015), recounts the events of the first as a slasher film in which you’re the star. And if that wasn’t enough, when you pause the game the menu is stylized as if a VHS tape, complete with static grain.

Five Nights At Freddy’s (purchase)

Before Five Nights at Freddy’s became the unexpected, viral, hurled-on-stage success (and major peeve for some) that it is now, it was a simple horror game with a neat idea. That idea is grounded in the game’s use of CCTV to unnerve you and, eventually, catch you off guard. You’re a security guard who must sit in an office, at night, and flick through the various video feeds that give you limited perspective of the pizza restaurant around you. It should be boring as heck. But, soon, you notice that the animatronic animals start to move around.

They’re creepy enough as is, but once you realize they’re alive and stalking you, they mount up to the level of terrifying. What doesn’t help is that your view is hindered slightly by low lighting and the static feed of the cameras. That degraded VHS aesthetic gives enough uncertainty to make you double take at times: did I just see a large duck peeking around that dark corner? No, surely not. Better check. Moments later you’re dead and you barely saw it coming.

Outlast (purchase)

Ugh. It’s been two years since Outlast (2014) came out and the spasms it embeds in the nervous system still haven’t gone away. Part of the reason why is due to how it makes use of the camera. You’re a journalist who sneaks into an asylum where the patients are running wild and getting their vengeance on whoever messed them up. Questionable horror tropes aside, this journalist carries a camera with him (to, you know, journalize), which is often your only way to see in the dark due to its night-vision mode. Problem is that the camera absolutely devours batteries. That thing is hungry. And so if you want the safety of being able to see in the dark at all you’ll need to hustle every corner of that depraved place to find batteries to replace the fresh ones you put in there only 10 minutes ago.

Not only that, but having to view a large part of the game through a camera means Outlast resembles found footage films such as The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Quarantine (2008). That association is immediately unnerving as you get the sense that you’re the one creating the footage that someone will later find, once you’re dead. You imagine them, as you play, watching back your final moments, terrified of their own fate as they watch yours play out. The viewfinder of the camera you peer through also emphasizes how limited the first-person perspective is and how vulnerable you are in every given situation. Not that you need a reminder.

Sylvio (purchase)

Sylvio is basically ASMR horror, never rising above a whisper. You play as ghosthunter Juliette Waters, whose soft voice is a salve amid creepy seances, inexorable black orbs, and massive phantasmal shades. The texture of the game is defiantly analog; it crackles and fizzes and distorts with the reality-bending intrusion of the uncanny.

Playing Waters forces you to look, to investigate. Even if you get freaked out, she’s there to do a job. Scrubbing through the reel-to-reel she lugs around to record the voices of the dead, she automatically writes down what they say. You can only observe from behind a curtain of static and haze, at arm’s length from a professional doing her work.

Dead End Road (purchase)

Y’know the credit sequence in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997)? The camera hurtles forward into the void, drunkenly capturing the play of headlines over the pavement, lane markers going rat-a-tat-tat right at you. Dead End Road is a game full of that. You drive all over a small town in an effort to rid yourself of a witch’s curse. Your car putters through heavy night, headlights struggling to cut the gloom. It’s never clear which lane the next car will come flying down.

It’s stressful! The lo-fi aesthetic adds a layer of claustrophobia: leaves and rain cutting across your view as the road twists queasily, the hard impenetrable dark always looming a few yards away. Smeary stretched textures, abrupt hallucinations, fake bluescreen errors, and the insistent waver of VHS tape combine to turn a series of, essentially, errands into something hypnotic and eerie.

Power Drill Massacre (download)

Power Drill Massacre is straight up not fucking around. That’s in terms of both its fuck-off-no horror and its callback to VHS slashers. You know how, in slashers, you moan at the actors on screen “oh, don’t go in there” or “of course she fell over right then”? Well, you are one of the actors this time around. You’re a teen lost in the woods who decides to find refuge inside an abandoned mansion. That would be a fine idea except a maniac with a drill cruises around there in bloodied overalls. Of course.

Sex is all about the climax. So, too, is horror. Theorists have written in the past of how these two opposite acts are connected in this way. It explains a lot of horror films and their many sex scenes. But the point here is that Power Drill Massacre lives for its climax. It comes so sudden that you’ll scream. A Michael Myers-looking dude comes out of nowhere and you’re dead. That’s the good ending, really. As if he chases you it can be much worse. Hurtling around corners not knowing whether he’s still behind you or if he has diverted to some other path in this hellish labyrinth in order to cut you off. You cannot endure that kind of tension for very long.

Anatomy (purchase)

If there was any one title on this list that epitomized the VHS horror sub-genre then Anatomy is it. Perhaps the strongest horror game from Kitty Horrorshow yet, it has you creeping around a darkened house, collecting tapes, and then playing them back to hear an eerie tale. The first playthrough isn’t all that bad. It’ll be slow going as you creep around, dreading just about everything, but you’ll get through it. The hard part is going back.

And you will want to go back in, as Anatomy actually requires four playthroughs to experience everything. This structure is meant to mimic the act of playing a tape over and over, the visible static bands that hang over the screen worsening each time, the tape steadily chewed by the machine. All of those visual effects happen in Anatomy. But more than that changes too. Though, to say exactly what happens would be to undermine the whole point of the game. Give it a go and fear every minute you’re inside. You should. That’s how it’s meant to be.

The post The rise of VHS horror games appeared first on Kill Screen.

Are videogames ruining Sleep No More?

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

— To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.

-Macbeth

Nestled in the deep dark corners of Chelsea, a faux hotel houses an experience that changed the way people saw theater. Sleep No More (2011), created by Punchdrunk’s Felix Barrett, tells the story of Macbeth (1611) but set in the 20th century. Billed as an “interactive play,” it allows viewers to discover the story at their own pace, breaking the linearity of the story in favor of a more modern form of storytelling. The actors flight from room to room, the audience scrambling after them to inspect all the objects and rooms around them or to watch their wordless performances. Required to wear plague doctor masks and forbidden from speaking, each viewer has their identity and individuality stripped away.

Yet, some audience members proved more compliant than others. It only takes one videogame player in the crowd to really test the limits of the “interactive” label. Kill Screen decided to throw several videogame players into the mix, by bringing the entire editorial team to a showing the night before Kill Screen Festival this past April. At the conference, a panel on horror took place between Barrett and independent game maker Kitty Horrorshow, where they discussed the intimate relationship between theater and games, horror and interactivity. Afterward, I caught up with Barrett to dig deeper into the question of how the increased prevalence of videogames is changing the nature of Sleep No More.

///

KS: I don’t know why—maybe because I knew I was going to interview you, but I went into Sleep No More with this very investigative approach. I wanted to break it. Not break the immersion; I was fully immersed. But I needed to see how far I could take it.

That’s exactly what Kitty [Horrowshow] said.

KS: Really?!

She had the same response. And I think that’s because it’s from a games perspective. I’m not totally a gamer myself, but there’s always that desire to kind of hack a game or try to mod it or find the glitch. It’s all about how you can control it—control someone else’s world. And with theater, it’s just this completely passive experience. It’s two polar approaches. And whatever baggage or cultural background people have informs the way they watch the show.

Macbeth by timechaser via Flickr

KS: I feel that. The minute we got in there—it was me and one other Kill Screen editor in the first room—and we just started ransacking the place like we were in a survival horror game.

Did you get a one-on-one?

KS: I didn’t get a one-on-one. But I got pulled into something with like the drinks at the bar, when a character lays out three drinks—I forget exactly what the context was. I was very overwhelmed. But he poured a drink for one guy, and when the guy went to drink it, the performer slapped it out of his hand. The second guy went to take the drink and he did nothing. Then when he gave the drink to me I had this bizarre freak out where I was so enraptured and so terrified of getting tricked… I literally poured the drink out!

Do you know what I think is really weird? The show’s been on for five years now and the world has really shifted in those five years. So when we first started, it was crazy enough to just have people walking around and not sitting down. Now people are used to that and we need to do more. We didn’t design Sleep No More for people to go against the grain. We designed it so that people would walk slowly with a crowd. And what we’re looking into now for future Punchdrunk shows, like the one we just did in London, is to actually embed more of that gaming mentality and even give the audience the ability to level up. Wouldn’t it be cool if there’s a room that you can’t get into because you’re on level one, but as soon as you’re a level three—[makes an unlocking noise]. It’s optional, so it’s a secret, but if you speak that language, then there’s something there for you. All the technology that wasn’t around five years ago now lets us to do stuff like that.

People review Sleep No More like it’s a game sometimes now. And I played Resident Evil (1996) as a kid, and it’s so informative now. We actually had an away-day with the team where we just played games and looked at the mechanics and said, “Fuck, alright, how would you stage this?” It’s been so revelatory. How would you stage Candy Crush (2012) or Clash of Clans (2012)? How do you take that set of mechanics and make it applicable to the real world?

KS: Wow that’s crazy. Well what I think you already have in common with the game designer is that you both know some secrets about human curiosity. What’ve you learned over the years about how to guide people’s curiosity?

When we were first trying things out in the early years of Punchdrunk, we did a show in the daytime outdoors in this gorgeous summer sun. And it profoundly failed. Because you can’t discover something if you can see it in the distance. Once you get there, it’s like “Oh, well, yeah, that’s what I expected.” What I immediately learned is that you need the shroud of darkness.

you need the shroud of darkness

KS: Kitty knows something about that too.

Exactly. The base emotion you need to create for curiosity is apprehension. Fear. You can’t be relaxed. When we did a Sleep No More in Boston, the fire department said the lights were too dark. So, the first night, we made them 5 percent brighter and it was a disaster. It fundamentally didn’t work. Because just a couple more notches of brightness and you have people just meandering around like it was a fun little show. It turned into this light, artistic romantic comedy. Curiosity is about the desire to seek out versus the fear of being caught, or the fear of something bad happening.

KS: Right. And in your talk, you described darkness as both threatening and promising. In your opinion, is that curiosity driven by genuine fear or more of the pleasure of fear?

I think it’s equal parts.

KS: What’s interesting is that Macbeth is such a superstitious play already. Lots of fear around it in the theater world. Do you all call it by its name or do you call it the Scottish play?

Well the irony is that we’ve treaded on so many superstitions in that theater that the place is cursed five times over. When we were building Sleep No More, one of the producers brought over a TV spiritualist, a medium. I don’t know why they brought her out. She was quite old, late 70s, and she had a panic attack. She was screaming and had to be physically ejected from the building. “People are gonna die, people are gonna die,” all while borderline frothing at the mouth. I’ve never seen anything like it. She just understood what all the superstitious iconography we had around meant. Half the rooms have things that are literally enticing demons or witches, so if you speak that language it’s quite full on. But it’s not real, is it? It’s theater. So we can say Macbeth because, if we were cursed, it would have happened by now.

Although we did have a ghost in the beginning.

Earthbound Souls by sanna.tugend via Flickr

KS: Explain that please!

The space that we took over used to be the club Bed—it was in an episode of Sex and the City—and it was a lounge where people lay in bed and drank cocktails. There was a rumble and some guy got drunk and a bouncer pushed him up against the elevator shaft. But in a classic horror movie cliché, the doors opened and the elevator wasn’t there and he died. So they closed the space that day and we were the first people to move in three years later. There were loads of weird things. And I really do not believe in ghosts but a lot of the staff refused to do things in certain rooms.

There’s one room in the detective agency on the fourth floor with loads of fans. And when we were rehearsing, the cast would keep saying, “Can you just switch all the lights and the fans off? It’s so hot and windy we can’t work.” So they called the technician and said, “Alright there’s no way the lights and fans will go off anymore because nothing’s plugged in yet.” We went back and started running the show and there were all manner of lights going on and off randomly. We genuinely thought that the explanation was that there was someone living in the building, but no one ever saw them. And then there was one door on the fourth floor that would not stay closed. You’d lock it and it’d pop open. It got to the point where we put a person to guard it, and even then when the shifts changed, the 30 seconds where people weren’t watching over it, it’d open. At the end of the day they had to seal it shut.

KS: I love it.

I’ve got a question for you.

KS: Go for it.

With your gaming mindset, what did you respond to?

KS: Weirdly, I really responded to the tactile experience of it. I just wanted to touch everything.

Did you follow the cast or follow the space?

KS: The space.

That’s the other thing, gamers don’t want to follow rules.

KS: Yeah I didn’t—gamers generally don’t want to be like everybody else. They don’t want to be like the masses.

Exactly. The dream way is that you’d be in there by yourself, like it was a videogame.

KS: Now I’ve got another one for you: How do you train your actors to react to assholes like me—to that gaming mentality?

Well they’re supposed to be looking for the people who are more curious, who deserve it most, so they can have a one-on-one moment with them and give them a key from around [the actor’s] neck that opens secret doors. The actors seek out the people who are really tuned into the rhythm and the tempo, grab their hand, and take them out. That’s the reward. You can literally end up in an embrace with them, feel their breath, be in a position you’ve only ever been in with a lover.

Image by Herman Beun via Flickr

KS: I was really curious about the time period you picked, too.

Well, did you see the scene with the witch and the drum and the strobes?

KS: Yeah, the blood orgy. Sorry—we called it the blood orgy.

It’s interesting because for that scene—you said you tried to break the show. We do too. And that scene is us setting rules and then breaking all of them. So when you build a set in the 30s, people get comfortable with that. Then if, all of a sudden, you’re in a different time and place. Now you fear it again. It’s there to keep you on your toes.

How was the blood orgy for you?

KS: The blood orgy was my favorite. I was leaning in so much that I actually got some of the blood on me. It was great.

Whenever I come into town with a bit of jet lag, that scene always peps me up.

When you look at a naked room, how do you identify the threatening versus the safe spaces?

I think it’s instinctual. It’s literally like I’m a child again.We do a thing with our cast—we rehearse offsite in a studio, then we take them to the space and layer them into the fabric of the world—and the first game we play with them is hide and seek. Three hours of crazy, full on hide and seek where the entire room is super dark. Everything’s in show mode, and the cast is creeping around scaring each other. People go totally rogue. We also give them tasks and one is to console a frightened little boy in the corner and tell him a fairytale. Obviously, there’s no little boy. But you’re in a dark space, and we’re prompting them to fill in the gaps. When I look at a space, I’m trying to find where the bogeyman could be hiding. Where are the shadows a little too dark? Where would I not want to go?

Can I ask you a question?

KS: Yeah.

So as a games person, did you come out more frustrated than satisfied?

KS: No, no, I was very satisfied. I actually left very ashamed. I felt like I’d done it wrong. I felt like I had ruined the experience for myself. I left wanting more.

And did you all stay together?

It’s profoundly out of control

KS: No, we all split up instantly.

Was there a range of different responses from the team? Did some people reject it? We’ve been trying to think, if we could remake this show for that interactive mindset, how would it be different?

KS: Honestly, I think it might ruin it. The minute you started talking about gamifying it, I hesitated. There’s this beautiful quality of being invisible. Of being completely ignored. As a games person, that felt different and I liked it. I guess all I would change is preparing for that mentality. If I had known I was a ghost more than a participant…

That’s so weird. That’s exactly what Kitty said. She kept referring to the audience as ghosts.

KS: Do you think the internet changed Sleep No More at all? Because, I mean, for one thing, people can just give away all the secrets online.

It’s interesting because our audiences used to be quite lone wolves in the early days. Now, they go as packs. They all meet before, there are fan groups. But everyone has different experiences. Part of the fun is speaking to everyone at the end and finding out what they did, what happened to them. The internet corrals that in a way, but it doesn’t mean the spoilers are out. We’re trying to think of how we could flip the shows we have coming up on their head again by incorporating the virtual. How do we make a digital space dangerous? Or what if the show is just the beginning? It’s that space between the fictional and the real. What happens if you go to the show, then you go home that night, go on the subway, get back home, and then at one in the morning your phone rings, and it’s one of the characters you’ve seen and they say, ”I’m round the corner, come meet me.” Now that is where it gets really dangerous.

KS: I’m gonna tell you right now, I’d be the player that causes lawsuits for you because I am so down. I’m too down.

[Laughing] It could go really wrong. The problem is that, if it’s the real world, how do you as the audience know you’re talking to a performer or not? You could have some crazy guy run up to you and say, “Come back to my place.” I mean so much can happen in the real world. But that’s what’s so exciting about it. It’s profoundly out of control. What I’m trying to do is create this synthesized state of a loss of control, but enough safety mechanisms to ensure it stays within the lines. It’s all about the contract between you and the audience. How do you protect an audience so they still obey the rules of civilized society while being in this fictional world? We’ve been testing it…

The post Are videogames ruining Sleep No More? appeared first on Kill Screen.

How to stealthily infiltrate a real-life 1970s cult? Let The Church in the Darkness show you

The Church in the Darkness has been pitched as an “action-infiltration” game based on a real-life cult since its announcement. But even though what we knew of it was colorful—far-left radicalist group in the 70s moves to Latin America to create a socialist utopia, goes full cult—we still didn’t know much at all. The game would include some element of stealth, but there would be options on how to play it, and you would never be forced into combat. The moral status of the Collective Justice Mission’s leadership would remain in question, and could even change from playthrough to playthrough. Until now, that’s all we knew.

you can see both the guards that approach you and the possible avenues of escape

Released late last week, The Church in the Darkness’s first video footage shows the stealth mechanisms that you can take advantage of in order to infiltrate Freedom Town. One cheeky move shows the player winding up an alarm clock and tossing it into the road in order to distract guards. You can also take advantage of open houses and the shadows cast on the ground to make sneaking easier. Though many stealth games are first-person and rely heavily on patience and precise timing to get past enemies, the overhead view of The Church in the Darkness also allows spur-of-the-moment tactical planning, as you can see both the guards that approach you and the possible avenues of escape.

However, The Church in the Darkness does apparently sport multiple play styles, and combat is also possible. The player character does have a gun, though it’s best reserved for a last resort as the noise will draw the attention of enemies. Lethal takedowns are also possible, both stealthy and overt. However, an attack-oriented character must be wary of their surroundings: the player character is relatively vulnerable, and the video shows the player mobbed and captured with ease after a gunshot attracted a crowd.

The most interesting part of The Church in the Darkness is still its backwoods cult setting. We catch a glimpse of a postcard from the main character’s nephew; the catalyst for the plot and objective of our infiltration. Throughout the new video, Freedom Town’s charismatic leader Isaac Walker is mentioned multiple times and later shows up to threaten the captured player. A defaced devotional card with of Isaac, “LIAR” and “ADULTERER” scribbled over his face, is later found in a chest in an empty house. Out in the forest, a clearing has “HELP US” stenciled out in sticks, to be seen from above. Even such a brief glimpse of the game reeks of its unique character and the air of mystery that The Church in the Darkness has been cultivating all along.

We still have a while until The Church in the Darkness is released in 2017, but it will have a demo at PAX West. You can watch the first gameplay video here and check out its website for more.

The post How to stealthily infiltrate a real-life 1970s cult? Let The Church in the Darkness show you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Niche, a survival game based on the real science of genetics

There are a lot of educational games out there that might teach you a thing or two about biology, evolution, and how genetics work. But they can be easy to disregard due to the often boring and dull methods of delivering that information. Well, Team Niche—a small five-person independent studio located in Switzerland—thinks it has found a way to make learning about genetics and species evolution a little bit more engaging.

Niche is described as a “fresh blend of turn-based strategy and simulation combined with roguelike elements.” The game puts you in control of an animal species in a certain landscape, ranging from snowy mountains to heavily cultivated areas, with the goal of trying to “keep your tribe alive against dangers, such as hungry predators, climate change and spreading sickness.”

you have to take into account proper genetics thinking

As everything in Niche is based on real genetics—which is the educational bit—you’ll need to employ smart breeding choices to survive. And to make sure you’re actually taking in all the information when making these decisions, the worlds and all the animals are procedurally generated. You can’t just learn the tics of the game; you have to take into account proper genetics thinking.

To help you along with this, when accessing the game’s menu you will be able to see “all the genes and abilities of a selected animal.” You’ll be in pursuit of unlocking more genes, and this is done by completing challenges, such as spending a lot of time in the savanna or the desert to develop big ears for your animal to cool down their body temperature. Collecting food, fighting, scouting, and mating also unlock more genes.

As you progress through the game and unlock more genes, animals can evolve and perform different tasks—for example, “when they develop stronger paws, they earn the ability to dig holes in the ground, which helps with finding food,” according to the game’s creators. Selective breeding to acquire these kinds of traits is a big part of the game and keeping your tribe alive, however, the studio did have to consider the possibility that players would pursue incest. This was taken care of by implementing a system that sees the offspring of closely-related family members more prone to sickness and might die younger.

Other dangers you’ll have to face in Niche’s world are predator animals, who have their own behavior module and motivations to eat the members of your tribe. Beyond that, the game world is divided into unique biomes, and “each biome requests different sets of survival skills and adaptions,” according to the creators. Nature-related events, such as temperature and weather changes, will affect each environment and require you to overcome new challenges.

But the creators of Niche can’t say exactly what these challenges might be as all of the game’s systems are meant to “lead to a simulated world in which various situations can emerge.” In other words, it’s unpredictable, just as the real-life science that the game is based on. All that can be said for sure is that the game “features various forms of heredity and is based on the five pillars of population genetics (genetic drift, genetic flow, natural selection, sexual selection and mutation).” Learn those and your tribe might stand a fighting chance at survival.

Niche is planned for release on PC in early 2017, with the studio planning on expanding to mobile and handheld consoles too. You can find out more on its website.

The post Niche, a survival game based on the real science of genetics appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers