Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 57

September 14, 2016

Expect to gather round Djur’s bonfire for a sci-fi fable

The campfire story has been resurrected in videogames recently. A rush of independent games have taken their own spin on the sit-around-and-talker, and the idea of making a game out of a fable is currently being tested by upcoming games like Forest of Sleep. The recently-announced game Djur expands this area of thinking, and aims to combine the quiet calm of fantasy worlds with sci-fi, and explore the meaning of myth and humanity through folk tales.

it attracts the uncanny

So far we don’t know much about Djur besides the unusual moniker of “sci-fi fable.” But that’s okay, because the little we do know sounds really, really cool. The initial description says that you “manage a place of respite” in the woods where creatures and humans gather to rest during their journey. Like most liminal spaces, it attracts the uncanny. The player listens to the stories these pilgrims tell and learns of the world outside her resting place, whether the tales are true or not.

The fable side of Djur is inspired by the team’s own environment: they’re located in Sweden, and consequently have taken cue from Scandinavian folktales in order to create a suitably cozy fantasy environment. The sci-fi parts are a bit more evasive. You can see in early art some sort of device that can be deconstructed, and there are hints of ancient technology within the concepts of buildings. The first screenshot seems to look into an overgrown swamp, with scant hint of either magic or technology besides the central hooded figure.

Djur’s only been in development for a few months, so we may have a while to wait before we hear more from it, but you can keep an eye out on the website for more art as we wait for the fable to be told.

The post Expect to gather round Djur’s bonfire for a sci-fi fable appeared first on Kill Screen.

Sanjay’s Super Team brings Indian mythology into the digital age

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Pixar’s Oscar-nominated animated short Sanjay’s Super Team (2015) premiered last year, delivering a personal story about Indian culture and spirituality to a global audience. A largely autobiographical tale directed by Sanjay Patel, it centers around the duality of his Indian-American identity, a largely underrepresented demographic in the Western-dominated field of animation and digital storytelling.

In an interview with The Verge, Patel said “It felt really important to me to have America see this, and have Pixar and Disney say it’s normal.” In the short, little Sanjay is enamored by a Transformers-like superhero action figure and TV show, only reluctantly joining his father for a prayer session. Midway through Sanjay’s feigned meditation, he falls into a dream-like trance, where he confronts a demon (or rakshasa) while being defended by the great Hindu deities Vishnu, Durga and Hanuman. In the end, Sanjay makes it out just fine, as he and his father come to not only understand but also respect each other’s cultural differences. Sanjay even gets to see his Transformers-like toy placed in the prayer cabinet, showing audiences how new and old idols can coexist side by side.

blends popular Western themes and aesthetics with classic Indian folklore

Sanjay’s Super Team not only casts a spotlight on Indian cultural experiences, but also on the artistic talent Indian creators can bring to digital storytelling. Choreographed by celebrated dancer Katherine Kunhiraman, the epic fight scene between good and evil brings classical Indian dance forms such as Bharatanatyam, Odissi and Kathakali into the world of Disney. However, Sanjay’s Super Team does more than just introduce a genuine and nuanced Indian experience into popular Western culture. It paves the way forward for a new kind of storytelling in India as well, helping older generations digitise their most ancient cultural traditions so they connect with the new, tech-enabled and increasingly global generations.

Gamaya Inc., founded by Narayanan Vaidyanathan, also brings Indian mythology to life with a quest-based videogame featuring Indian divinities on a mission to restore the sacred Ramayana text to safety. Aside from citing the Amar Chitra Katha comic books as a major source of inspiration, Vaidyanathan said that “my grandmother’s storytelling has always played a big part in inspiring me to make a product using Indian folklore.” Gamaya Legends allows Vaidyanathan to pass down his grandmother’s storytelling onto his daughter. “As a kid, I listened to many stories from my grandmother that inspired and entertained me,” he explained. “As a parent, I want my kid to have the same experience. But today’s kids are harder to please—they are used to slick animation and engaging games.” Vaidyanathan sought a way to help kids in the modern world connect with these important cultural traditions. “We set out to create an experience that spoke in a language our kids [could] understand—with a highly engaging presentation that blends the real and virtual worlds.”

Echoing the sentiments (and even the story beats) of Sanjay’s Super Team, Gamaya Legends not only allows kids to explore these legends in a mobile action game, but also brings real-world toys to life. Following the smart electronic toys trend popularised by Skylanders and Nintendo’s Amiibos, inGamaya Legends kids can buy internet-connected figurines of their favourite mythological heroes that, when placed on the designated toy station, spring to action in the digital world. According to Vaidyanathan, Gamaya Legends “gives kids a cool action game where their real-world toys come to life and they discover the true legend of one of the greatest epics.”

The future of digitising Indian culture and storytelling only promises to evolve

At the same time, Gamaya Legends also blends popular Western themes and aesthetics with classic Indian folklore, addressing the interests of a generation that consumes pop culture from around the world. The art for the Ramayana scrolls in the game was even created by a concept artist who previously worked on World of Warcraft. “The characters are incredibly limited by what caste they are in—the idea is that you don’t choose your caste. So when the [the game] starts, you are given a little information about your character. This is the hand that [you’ve] been dealt and [you] have to adapt to it.”

The future of digitising Indian culture and storytelling only promises to evolve. As the country becomes increasingly internet-connected, younger generations must learn how to integrate their unique cultural influences into the largely Western-dominated tech space. By combining the rich cultural complexity of a modern Indian identity with the mass appeal of mainstream videogames and animated films, this digital storytelling crosses new frontiers and breaks old barriers. While helping to preserve Indian culture, it also challenges the grittier societal norms, issues, and assumptions of tradition.

Hopefully, epic Indian sagas like Sanjay’s Super Team can soon be extended into full-length feature films, allowing global audiences to experience and applaud the various layers of Indian culture.

The post Sanjay’s Super Team brings Indian mythology into the digital age appeared first on Kill Screen.

No! Please don’t take the weeds out of Animal Crossing

I’ve heard many lovers of Animal Crossing: New Leaf (2012) express a desire to go back and play some more. What’s stopping them? It’s the fear of what state their town will be in after the mayor disappeared for six months (or more).

Animal Crossing’s infamous weeds are the personification of this guilt, growing in your town every day you’re absent; a grand public exhibition for your neglect. But an upcoming update to Animal Crossing: New Leaf will remove them forever. Whoopee, you might say. But no, don’t be so hasty, as this may actually diminish what makes Animal Crossing so special to so many people.

In February of this year, I desperately needed something to hold onto. My brother had been in a car accident that had wreaked havoc on his mental health, while my grandmother’s health was also rapidly declining. My anxiety disorder was revealing itself to have new and terrible symptoms that were destroying me mentally and physically. I needed control. Perhaps in some sick attempt at putting myself through even further pain, I returned to my village in Animal Crossing, after not having played for a year. I braced myself for the rage of my villagers at leaving them without help for so long. I held my breath, waiting for the crushing weight of the impossible task of pulling all those weeds.

But all that guilt never came to fruition. Instead, my villagers greeted me joyfully, happy that I’d finally come back. They said they missed me, they wondered where I’d gone—but they weren’t angry. Surely the blow would come with the weeds—but no. Leif, the gardener, revealed a mini-game where, upon pulling all the weeds, he rewarded me with a piece of furniture.

A world with endless forgiveness

Animal Crossing sets up the expectation of punishment and guilt for your negligence. But what is always revealed is a world with endless forgiveness and kindness. Your village will always take you back, and they don’t hate you. They’re just glad you’re finally home. Removing the weeds takes away a key part of that, even if it seems to fix the guilt problem most players cite as the reason for not returning. Cleaning up the weeds in Animal Crossing is like doing the dishes after Thanksgiving. You were worried your parents would be mad at you for not calling more often, but when you do this little thing to help out, they thank you and give you a hug. And that makes your return even warmer.

The post No! Please don’t take the weeds out of Animal Crossing appeared first on Kill Screen.

The next game from the creators of This War of Mine looks ice cold

11 bit Studios, the creators of This War of Mine (2014), has announced its latest game: Frostpunk. 11 bit Studios have been fairly mum about the contents of the game (or even how it will play out exactly), and aside from the announcement trailer, a tagline—“Frostpunk takes on what society is capable of when pushed to the limits”—and a logo that closely resembles an energy drink brand, there is little to go on.

inspired by the cruel, frozen world of Snowpiercer

The name itself, Frostpunk, indeed feels rather different than their previous serious fare. Frostpunk is another in those terms, the -punk naming conventions originally coined by Bruce Bethke with the creation of cyberpunk (and continuing on to things like steampunk, dieselpunk, and elfpunk). In this case, the 11 bit seems more inspired by the cruel, frozen world of Snowpiercer (2013) than 1980s speculative fiction, though only time will tell.

The studio promises to continue bringing the maturity that they brought to This War of Mine, with a focus on what happens in a frozen world with a society reliant on steam power. On the announcement for the game on the This War of Mine Steam forum, the studio wrote “What is culture when morality stands in the way of existence?” It’s a similar kind of feel to the morality that weighed down your decisions in This War of Mine, a game that had you follow the struggle of innocent civilians in a war-torn country rather than a fearless Marine (as is usually the case in videogames).

For such a complicated sentiment, the announcement trailer is a study in contrast. 11 bit pairs the sight of a man frozen to death with a fairly innocuous poem, “Now Winter Nights Enlarge” by Thomas Campion about the ending of fall and the beginning of winter, about cuddling up safely in warm homes as winter slides its icy fingers along windowpanes.

Frostpunk is still in its very early stages and is due out in 2017. If you want to find out more, you can check out its official website.

The post The next game from the creators of This War of Mine looks ice cold appeared first on Kill Screen.

No Man’s Sky and the Naming of God

In Darren Aronofsky’s 1998 film Pi, a mathematician is doomed by a recitation of the divine name. Young Max Cohen, the Icarus of New York City, is a socially anxious shut-in who devotes his time and his ultra-sophisticated computer technology to finding a predictable pattern in the stock market. Cohen names his computer Euclid; both the name of a Greek geometrist and the starting galaxy in No Man’s Sky. His conviction, expressed as a tidy syllogism in a recurring voiceover fragment, is that since nature is made of patterns, and math is the language of nature, everything in nature has a pattern. The universe is a veritable theater of processes, governed only by the purity of numbers and the unthinkable infinity of the possible relations between them.

Cohen eventually finds his pattern in the form of a 216-digit number. As he internalizes the numerals and their relations, it destroys him: lifelong cluster headaches intensify, hallucinations disrupt his days, and paranoia finds its realization in persecution. Although it was the stock market he wanted to predict, Cohen doesn’t try to capitalize on his gains. He even refuses to explain his understanding of the pattern when a group of investors who provided him with a piece of critical technology hold him at gunpoint. Cohen is saved from the investors by a group of Hasidic Jews who reveal that the 216-digit number he’s found is nothing less than the true name of God. But he is unimpressed by their request for the number, and the Messianic Age it heralds: “I found it,” he says. “It was given to me.” In the end, however, he gives it back. At the film’s climax, we see a shot of Cohen against a pure, white light serenely reciting the divine digits. Then he wakes up, racked by the worst of migraines, and sticks a power drill in his head.

What is Max Cohen’s sin? The investors wanted to profit from the pattern, but even when they get a copy of the number, they are unable to use it properly: they crash the market instead of conquering it. They are victims of their own sense of entitlement, demanding that the world conform to their expectations when they throw money at it. As for the Hasids, their lust was for a kind of power that their people had been deprived of since the Roman destruction of Judea. Their resort to violence and threats in the face of Cohen’s refusal to cooperate belies their own claim to legitimacy. Unlike either of these groups, Cohen didn’t want money or power—only knowledge. But by refusing to share his wondrous knowledge with anyone else, Cohen ultimately lost what it had to offer, and the world lost it with him. Had it been a few years later, he might have avoided all the trouble without ever stepping outside his apartment door. It takes no time at all to post a 216-digit number on Reddit.

The universe is a veritable theater of processes

No Man’s Sky is a game about naming things. It can be about many other things, if you like: discovery, wandering, existential angst, shooting stuff, grinding, pantheism, crafting, not grinding, blasting your rocket pack and falling repeatedly to the ground, feeding the dogs, dogfighting, fighting the dogs. But many people seem unable or unwilling to see what the game is, rather than what they wanted it to be, or thought it might be. Like the investors in Pi, they are too focused on the immediate returns on their temporal and monetary investment, as if they had been salivating over No Man’s Sky for the last three years as a personal favor to Sean Murray. One critic has even called the game “anti-consumer,” presumably with the implication that this is a bad thing. And beneath all of the discontent is the insistent refrain that there is nothing to do in this galaxy-sized game.

So here’s a thing you can do in No Man’s Sky: you can name things. You name star systems, you name planets, you name plants and animals of every form and hue. You have the opportunity to name more things than you could possibly come up with names for. And you get points for naming things, but that isn’t the point. The point is to name them well. And that requires a bit of thought about what makes a name, and what a name makes.

In Western culture, the paradigmatic naming scenario is in the first few pages of the Bible. Here, God creates the world by naming it piece by piece: “Let there be light,” he says, and light there is. This cycle repeats until he creates Adam, the first man, who lives in the Garden of Eden. Adam, made in God’s image, is God’s surrogate in creation, so he adopts some of his authority. God gives Adam dominion over “every beast of the field and every bird of the sky,” and marks this dominion by making Adam—who has nothing better to do anyway—give a name to every type of creature there is.

There are two distinct functions played by names in these verses from the Book of Genesis. When God names something, he brings it into existence. This association between God’s language and his creative power is reinforced by a famously obscure verse from the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” This verse seems to make even God subservient to “the Word,” as if his own name preceded him. On the other hand, mortals are not given the power of creation. Ours is the power of possession. And for Adam in the Garden, the universal act of naming is an assumption of ownership over nature. This territorial function of naming, mythologized in Genesis, later served as a model for the colonial appropriation of indigenous land throughout the world: plant a flag someplace you’ve never been, call it something new, and it is yours to reap.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see the universe of No Man’s Sky as a new, virtual Garden of Eden, replete with more beasts than even Adam had time to meet. Its uncivilized wilds and lonely trading posts reinforce the sense that you are one of a few to have just awakened in existence for the first time. But No Man’s Sky encourages you to constantly uproot and explore, while Eden was meant to be a permanent paradise. The Garden was resplendent with light, God’s first creation, while No Man’s Sky makes you feel the distance between your character and the radiance at the center of the universe. For all the time you spend lasering plants and rocks into resources, the game doesn’t allow you to maintain any kind of dominion over these planets. And your limited inventory doesn’t let you keep more than what you require for the task at hand. You, needy and fragile, are no conquistador; No Man’s Sky is not a campaign. If there is any meaning to the names you leave behind, it isn’t explicable through the paradigm of Genesis.

No Man’s Sky encourages you to constantly uproot and explore

In A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), the first volume in Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy series, we find a version of an older, more mystical function for naming. In Le Guin’s world, creatures human and otherwise are typically known by many names. The protagonist begins as Duny, then becomes Sparrowhawk, and is rechristened as Ged when he comes of age. But Ged is his unique “true name,” and anyone who knows him by this name can assume control of his actions. Ged later draws on this power when he wards off the dragon Yevaud by naming him: “When he spoke the dragon’s name it was as if he held the huge being on a fine, thin leash, tightening it on his throat.” Naming functions here as a mechanism of power rather than possession. But the structure of the act is different. For Adam, possession was coequal with the original christening; for Ged, the power comes from knowledge of the true name that is coequal with the dragon’s very existence.

This conception has roots in a different current of religious thought that recurs in different forms across Judaism, Russian Orthodoxy, and Islam. In this tradition, the dragon is God. God has a true name, and to know and speak that name is to assert a kind of power over God. This is why the Hasids are so determined to acquire Max Cohen’s pattern in Pi: by translating the pattern into letters through the obscure art of gematria and intoning them, they hope to bring God’s power to earth to begin an apocalyptic Messianic Age. This fictional scenario illustrates the real belief in traditional Judaism that God’s name somehow contains God’s essence, and must therefore be treated with care. Meanwhile, a sect of Russian Orthodox Christians called the “Name-Worshippers” accord an even greater power to the name of God. For these believers, “the name of God is God,” and through ritually repeating it, we can gain enlightenment and greater understanding. Moreover, if God truly is his name, then to utter that name is to continually recreate our creator.

The bridge between name-worshipping and No Man’s Sky is mathematics. When Georg Cantor demonstrated in the late 19th century that there are different infinities, math and theology began to mingle in strange ways. If we can prove that, say, the set of all natural numbers and the set of all real numbers are infinite, but that there must always be more real than natural numbers, then we admit the existence of different infinities. But what is that “existence?” Does a particular infinity have a reality of its own, or is it a construct of thought? For the Moscow School of Mathematics, whose list of founders includes several prominent Name-Worshippers, both answers were true: mathematical objects like different infinities are real because we can name them. In this way, they are no different than God.

No Man’s Sky is not an infinitely large game, but the size of its universe so exceeds human standards of comprehension that it might as well be. Some have suggested that the size is irrelevant to the game’s quality, as if a game with 18 quintillion procedurally generated planets is no more interesting than a game with eight. In my opinion, this argument doesn’t hold because human beings are not infinite, and neither are our memories or imaginations. Infinity lives only in our equations, and can only be approximated through the technologies that do what we cannot.

The equation at the core of No Man’s Sky which generates the game’s unthinkable diversity provides such an approximation, but it needs the player to fully do so. Most of what we loosely refer to as the universe of No Man’s Sky exists in a purely virtual, purely potential form—even its creators don’t know what’s there, because what’s there isn’t really “there” yet. It only exists as a pure variation of an algorithm. It isn’t until a player ends up in the right spot, whether through the lottery of spawn points or through deliberate exploration, that the corresponding systems are generated—and that player can be anyone. You are the ontological catalyst.

You are the ontological catalyst

This puts a democratic twist on the theology of naming, and creates a new model with few precedents. It is a model of pure discovery, unsullied by either possession or power. To name something in No Man’s Sky is not a matter of saying “I was here first,” or “This is mine.” It is a pure affirmation: “This exists.” And what “this” is, its individual nature apart from the process which generated it, is what you help to determine by naming it. A player that touches down in some distant future on a planet you named will have a different experience of the environment depending on whether you name it “Heaven,” “Hell,” or “Harambe.” So when you leave the system or turn off the game, the objects you actualized don’t slip back into the virtual ether because they are no longer the same objects. And the mark of that change, should you choose to leave it, is a name.

Does this leave a place for God in the cosmos of No Man’s Sky? If a god is a creator, then everyone who plays the game is a god and the apostolically bearded Sean Murray merely our shepherd. Or perhaps God is contained in the equation itself, as he was in Max Cohen’s 216-digit pattern. I’m no Cohen, but my personal conviction is that God is everywhere in this game, just as the equation is. We need not long for the bright center of the galaxy, for its light suffuses the cosmos. One name for such a belief is pantheism. But if God is everything, then so is that name. Like the universe of this bountiful game, it speaks, and it says that everything new is a return. That it doesn’t matter if you don’t play No Man’s Sky, because you are, and you have, and you will forever. Call that a stretch, if you like. But call it something.

The post No Man’s Sky and the Naming of God appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 13, 2016

Get your eyes all over the hand-drawn world of The Collage Atlas

The paper illustrated world of John Evelyn’s The Collage Atlas looks a lot like a Victorian parkscape as envisioned by A-Ha. But Evelyn, a UK-based illustrator and game creator, is looking to invite players into his hand-drawn world and perhaps share with them an interesting experience tinged with a little nostalgia, and maybe even a little sadness.

“Even as adults we still see fairy tale scenes when we allow our minds to wander—those trees that look like giants, and those clouds that look like shoals of fish,” Evelyn said. Drawing from these natural observations, Evelyn is creating a puzzle game that comes to life before players eyes.

Almost like a pop-up children’s book

Traveling through an illustrated world, players must find their way through this monochromatic dreamscape by finding the correct path home. His previous title, a mobile game called A Skyrocket Story, utilized the same hand-illustrated look seen in The Collage Atlas. Unlike Skyrocket, which was limited to a 2D plane, The Collage Atlas is a traversable 3D world that comes more into existence the further players go. Almost like a pop-up children’s book.

Nostalgia, Evelyn says, is the main driving force behind his design work. Citing Japanese artists like Naohisa Inoue and Hayao Miyazaki, as well as French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Evelyn explains that he “tend[s] to be inspired by nostalgic, sentimental and reflective works.”

While Evelyn has been working as a designer and developer for years, The Collage Atlas is by far his most ambitious project. It’s a challenge for sure for the one-person developer, but the idea for Atlas has been rolling around in Evelyn’s head for far too long to not make. The coming title is meant to serve as a sort of, prelude, to what Evelyn envisions will be the beginning of a much larger game.

The post Get your eyes all over the hand-drawn world of The Collage Atlas appeared first on Kill Screen.

A new retro-style platformer lets other players control the monsters

Game jams are filled with sleepless nights. Designers and artists gather for a short period of time, like a weekend, then work non-stop to create something playable in that limited time frame. A game jam is an intense and challenging way to create a game. And yet, it’s how many fantastic videogames are born, like Surgeon Simulator (2013), SUPERHOT, and Nuclear Throne (2015). One of the latest game jam ideas turned retail release is Don’t Crawl, from Nick Belorusov and Vadim Dyachenko

“Ideas that spring to mind at 4AM when waking up for a game jam, are rarely truly original,” Belorusov explained when I asked him where the idea for Don’t Crawl came from. He wanted to see how the multiplayer elements from Crawl would work in a 2D platformer. And when he pitched the idea to Dyachenko and asked for his help, Dyachenko agreed. It sounded like it could be a good idea for a game. “Seems like I wasn’t wrong!” Dyachenko said.

Dont’ Crawl offers two ways to play. Like a traditional platformer, you can play as the main character—the one who runs and jumps through the level, avoiding any hazards in their way. But other players take on the role of the enemies and traps in the world. So, as one player tries to jump across a gap, others can try to stop them. That’s the basic idea behind Don’t Crawl: a group of players trying to stop one player who is attempting to reach the end of the level. Think Super Mario World (1990) but the Goombas are being controlled by other players over the internet.

As I spoke to Belorusov and Dyachenko it emerged that they both love Spelunky (2008). Belorusov is a big fan of the popular platformer and even though he is only 18-years-old he described a feeling of “nostalgia” for old-school platformers, like the Megaman series. Dyachenko is such a big fan of Spelunky he actually created a mod for the original release of the game. This mod allowed two people to play cooperativley. As Dyachenko explained “Spelunky in general sets high standards for what a game of it’s kind can be, and very few games can stand [in] line with it.”

“THE SCALE OF THE GAME WE WANTED TO ACHIEVE MADE CREATING IT A NIGHTMARE”

Belorusov and Dyachenko’s love of Spelunky and retro platformers can easily be seen in Don’t Crawl. The game has a similar retro look and sound. That passion meant it was quite easy for them to pull off the aesthetic—it was the online multiplayer they struggled with, especially when trying to hack it together during the chaos of a game jam. “You don’t usually see online multiplayer games made for jams,” Dyachenko said. “Because doing online multiplayer is hard (even harder to do right).” Unsurprisingly, then, it was the online multiplayer that the pair worked on the most when making the bigger version of Don’t Crawl.

The biggest issue with Don’t Crawl‘s online components that needed tackling was connectivity. “It is commonly said that you can’t make online multiplayer in a fast-paced game like this,” Dyachenko. His aim was to prove that statement false, ensuring that Don’t Crawl‘s online multiplayer wasn’t brought down by lag. And for those players who don’t want to play online, Belorusov and Dyachenko were quick to point out that Don’t Crawl also supports local play on a single PC.

Don’t Crawl has come a long way since being an idea born at four in the morning. The game now has a level editor and will support Steam Workshop. Belorusov and Dyachenko aren’t done working on it, either. Don’t Crawl is currently available in Steam Early Access and will continue to receive updates. They’re excited to bring Don’t Crawl to Mac and Linux in the future.

Don’t Crawl is currently available on Steam Early Access. You can also follow Nick and Vadim on Twitter where they share info about Don’t Crawl and other games they are working on.

The post A new retro-style platformer lets other players control the monsters appeared first on Kill Screen.

I Love Fur lets you pet the coats of imaginary creatures

Most people have owned a pet at some point in their life. And even if you haven’t, you’re probably familiar with the passion that erupts inside children when they see a fluffy dog or a well-groomed cat—they must be smothered with love, their fur tousled and stroked to make them feel good. But children don’t always want to pet normal creatures, and sometimes their imagination runs wild with dreams of petting dragons, unicorns, or perhaps something slightly more in reach like a polar bear.

Well, Nina Geometrieva, an artist located in Singapore, decided to create an iOS app that lets you pet virtual exotic and imaginary creatures. The app is named “I Love Fur,” and features creatures that include an evolved Sea Cucumber, a Bipolar Bear, and also a Supernova-Eating Fungus. In a brief interview, she revealed that her inspiration came from the way she saw people scroll their feeds, with their fingers scrolling as if they are gently petting their smartphones.

it won’t start glowing until you play with it the way it likes

She also discussed her future plans for I Love Fur, and confirmed there will be more creatures added later on, with “totally different, unrealistic fur properties, like elasticity or strands that lengthen when touched, or glow or change color, or break the confines of physics and reality.” She then went on to offer a sneak peek at two of the upcoming creatures, which are an Unshaven Cthulhu and a Snowphobic Yeti. You can check out a picture of the latter below.

Each one of the furs will have its own needs and demands, which you will need to fulfill in order to strengthen your relationship with them. For example, if you are petting a creature with glowing fur, it won’t start glowing until you play with it the way it likes. You start off as a complete stranger but should slowly turn into best friends as you get to know each other. I Love Fur should amuse some children, and will surely finds its way into the hearts of fur-loving adults.

You can download the app for free on the App Store. You can find out more on its Behance page.

The post I Love Fur lets you pet the coats of imaginary creatures appeared first on Kill Screen.

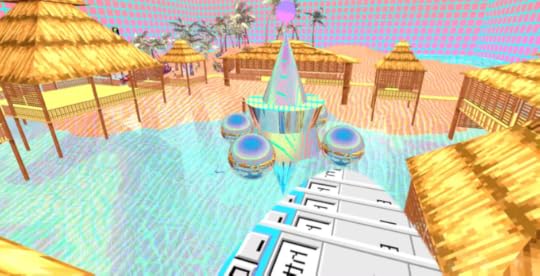

Broken Reality wants to take you on an adventure through ’90s internet

So, last time we saw the game—experiment? accident? digital hellbeast?—Broken Reality, it was more of a hyper-animated art collage than anything. A game lurked somewhere behind all the faux-Myspace popups, it was said, but there were no actual details to be found. A vague teaser trailer gave a glimpse of the attitude of the beast, and the game’s Tumblr certainly promoted the aesthetic, but anything beyond that was radio silence.

it was more of a hyper-animated art collage than anything

Luckily, it seems that Broken Reality has re-emerged from its bizarre technicolor web-cave and has come out with something a bit easier to digest, namely a Kickstarter for the final product of what now amounts to multiple years of work. None of the carefully-curated digital incoherency has been lost, of course, but it does now have a shape: a single-player adventure game taking place in a literalization of the internet, where different types of websites become individual level types with their own mechanics. It has screenshots now, too—lots of neon pink, perpetually-glitching skies, and beautifully tacky font choices—though they look a lot like the teaser trailer.

Broken Reality has no shortage of material, either. The creators have a boatload of backer rewards lined up, as well as achievements (!) for various social media milestones. That makes sense, as the game itself emphasizes the social aspect; that is, the social aspect of meeting strangers on the internet in a hazy chatroom, which they mimic with shiny avatars that you’ll meet throughout their world. And this is all without mentioning more standard videogame fare like collectibles, minigames, and easter eggs—all in tribute to their psychedelic ’90s aesthetic, of course.

If this sounds like your kind of thing, fear not: the creators of Broken Reality have promised a demo by the end of the year, and they’ve come out of hibernation with new material galore. You can support their Kickstarter campaign for another 17 days.

The post Broken Reality wants to take you on an adventure through ’90s internet appeared first on Kill Screen.

Drive through the roaring Italian 70s when Wheels of Aurelia arrives this month

Milan-based studio Santa Ragione has revealed its game Wheels of Aurelia will be out in full this month on September 20th for PC. It’ll cost $9.99. That price includes the game’s full soundtrack, comprising four songs written, composed, and performed in the style of Italian 70s music. The game is also coming to PlayStation 4 and Xbox One on October 5th.

Wheels of Aurelia puts players in control of Lella and Olga, girls caught in the midst of Italy’s 70s social revolution on their road trip to France. Taking place on the Via Aurelia, Lella picks up various hitchhikers and learns their motivations along the way. Part isometric racing game, part interactive fiction, Wheels of Aurelia allows players to both learn the backstories of Italian locals living in a “time of terrorism, kidnappings, and political turmoil,” as well as desperately evade whatever pursuers may follow.

illegal street races and intense debates with a catholic priest

Santa Ragione co-founder Pietro Righi Riva adds that you can expect car chases, illegal street races, and intense debates with a catholic priest. The only way you can get to experience each of the different possibilities the game has to offer is to replay it and make different choices—Righi Riva notes that each playthrough lasts around 15 minutes but there are 16 different endings to discover.

We got a chance to go hands-on with Wheels of Aurelia’s beta last year, noting that while trying to select dialogue options while racing down the coast’s often-curving roads made it feel like a “texting-while-driving simulator,” it did portray the banter of Lella and Olga in a way that captures a “burgeoning relationship to each other and the rest of the world as it evolves.”

For more on Wheels of Aurelia, follow developer Santa Ragione on Twitter.

The post Drive through the roaring Italian 70s when Wheels of Aurelia arrives this month appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers