Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 99

February 12, 2023

Ongoing notes: mid-February, 2023: Sarah Burgoyne + ej kneifel

Good morning! Wait, where did January go?

Good morning! Wait, where did January go? And you’ve been catching the slew of above/ground press chapbooks out recently,yes? The press’ thirtieth year of operation!

Montreal QC: Sarah Burgoyne’s latest is the chapbook Air’s Error (Toronto ON: Anstruther Press, 2023), a title subtitled “A Dance in Fourteen Poems” that responds, as she writes in her notes at the end, as “a poem-to-dance translation of an improvised performance by Hilary Bergen on Montreal’s St-Hubert Plaza, March 3, 2021.” I’m curious about the occasional book or chapbook poem-offerings that respond to dance, a list I’m not even sure I can list beyond more than a title or two; Chicago poet Carrie Olivia Adams’chapbook Grapple (above/ground press, 2016) comes to mind, certainly. As with much of her other work—chapbooks including A Precarious Life on the Sea(above/ground press, 2016), TENTACULUM SONNETS (above/ground press, 2020) and Double House (Turret House, 2022) [see my review of such here], as well as full-length collections Saint Twin (Mansfield Press, 2016) [see my review of such here] and Because the Sun (Coach House Books, 2021) [see my review of such here]—Burgoyne takes an idea or a subject and comes at it fully, working to explore, dismantle and dislodge across a wide canvas of sentences, composing a lyric to worm underneath her subject’s surface. And here, she utilizes the movement of a specific dance performance as both subject and prompt: “It takes a moment for the gaze / to settle,” she writes, in her opening poem “0:00 – 0:59,” “but when it does it / lands on you.” There is such a fine precision to Burgoyne’s lyric, a flow that contains and allows for a wide array of movement, even propulsion. Including a video link to the performance in her notes, Burgoyne’s thirteen improvisations, each less than a page long, take their titles as time-stamps, and it would be interesting to follow along to see how the text corresponds with the full performance. “Your hands are winged / as they sculpt space.” she writes, as part of “12:00 – 12:59,” “You / conjure now an animal who / once bowed her head to feed / here.” The chapbook closes with the six-page accumulation, “Epilogue: Instructions for Recognition,” that begins:

Your arm must follow the flight of balloons to a silver trumpet suspended in air.

You must pull it down and blow to awaken the danceless, shaped as mannequins.

The gesture upsets Time’sCapital’s dialectric.

Dance it.

There were entities that were powered through breath or wind, were mechanical and then appeared living to the people viewing them.

Film the dance in gown-surround.

Be ornate jellyfish in a glass pond.

Montreal QC: The latest from the delightful ej kneifel[see where we discussed the prose poem at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics] is the chapbook VIO-LETS (Anstruther Press, 2023). I’ve long enjoyed the quirky twists and sweeps of kneifel’s lyric prose that is somehow simultaneously neither a straightforward “lyric” nor “prose,” and yet, somehow both, mingling and mangling in a deceptively easygoing manner of steps and stops and starts. Across fourteen prose poems, kneifel composes a specifically and concretely abstract space around a shape of the prose poem, one held and halting, rushing like a mouthful of water or caught breath.

CATCH

little’s favourite time of day is when we agree that a saturday feels like a sunday. big won’t tell us his but we know he’s trying to keep mornings a secret. me, i like blue. i like when my shadows are tall as they want to be. or no, i like when water’s the air but i know they’re around cause they howl their whale songs. i’m not usually very good at just catching (i tip over light i trip over) but today i caught something so big even little had to go wow. we were under the oak when its shadow caved ours, when a new one ducked both and we swam in the shade. little said when i see something falling it’s always a bird, as, i can’t say what it was, but i caught it. i let it go too, and that taught them something. i know cause their bellies were wide.

February 11, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sophie Crocker

Sophie Crocker is a writer and performance artist based on stolen Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ land. They hold a BFA from University of Victoria. Their publications include The Malahat Review, The Fiddlehead, Best Canadian Poetry 2022, and elsewhere. Their first poetry collection,

brat

, was released in September 2022 from Gordon Hill Press. Find them online at sophiecrocker.com or on Twitter and Instagram as @goblinpuck.

Sophie Crocker is a writer and performance artist based on stolen Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ land. They hold a BFA from University of Victoria. Their publications include The Malahat Review, The Fiddlehead, Best Canadian Poetry 2022, and elsewhere. Their first poetry collection,

brat

, was released in September 2022 from Gordon Hill Press. Find them online at sophiecrocker.com or on Twitter and Instagram as @goblinpuck.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

This most recent publication was my first book. It’s been a really affirming experience to have a full collection go out in the world. It’s scary, too, because when all those poems reach a larger audience, I give up control over them. They become a shared experience. I’ve felt so much support from my community, which has been so beautiful. I dedicated this book to the people I love, and I’m feeling that love in return.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually majored in fiction with a secondary focus in screenplay. Poetry was what I did to relax when I needed a break from other forms. I started to get really into Richard Siken, Mary Oliver, and Warsan Shire — they just happened to be the first poets I absolutely adored — and from there I just became this big poetry nerd.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Every once in a while, when I’m lucky, I get a fast first draft that looks a lot like the final version. Those are often my favourite poems. Otherwise I go the notes route. The notes app on my phone and my little hardcover notebook are both strictly for my eyes only. I do some of my messiest, draftiest writing in them.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ve never intentionally started a book. Most of the time, I’ll get excited about a certain feeling, aesthetic, or character that’s hard to put into words. The fact that it’s difficult is what makes me want to put it into words. Then it becomes a book from there.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. When I’m not writing, I do improv, theatre, and standup comedy. Readings are a great opportunity to combine performance and writing.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

God(s); personal responsibility; reincarnation; what we owe each other; how to stand up to oppression; and, in the words of Chen Chen, how to “stay tender-hearted, despite despite despite.”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think most artists resist “should”s. The moment there’s a “should,” we find a way around it, and I think that that’s part of what makes art really powerful. I quote Kaveh Akbar’s lecture TOWARDS THE REVELATORY BREAK a lot, and it’s relevant again here: “It wouldn’t be a stretch to call the English language itself one of the deadliest, most murderous colonial weapons ever invented.” So, I think, the role of the writer — at least in English, which is my primary language, and also in French, which is my secondary language and also a colonial tool — is to take responsibility. Whatever we do, we must do carefully and with great attention to intention and potential impacts.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love working with an outside editor. I’ve been lucky enough to work with a lot of great editors, and I work as an editor as my day job. A second pair of eyes is incredibly valuable. Much of writing is about connection, so why not invite that during the creation stage? I’m pretty hard on myself, so actually constructive criticism is a welcome change. My writing/editing partners Shaelin, LJ, Alex, Ciarán, Kurtis, and Ben are deeply treasured people in my life.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My dad always says to always give people the benefit of the doubt up until they have given you every reason not to. He also says: always punch Nazis.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I used to primarily write fiction, but since the pandemic began, I’ve mostly had the energy for poetry. I write a few lines and then go back to hibernation.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every day, even if it’s only a few lines. I make sure to read and get outside/get active every day too, because otherwise I don’t have any motivation to write. I’m working on living in the moment as much as possible. That helps me notice small details about the world and about how I’m feeling.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Some poets make me want to write whenever I read them — Morgan Parker, Alex Dimitrov, and Paige Lewis, especially — so I’ll read or re-read their work. Other than that, I’ll go on a long walk or try to have a new experience that pushes me out of my comfort zone.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The fragrances of the ocean, fresh coffee, and my mom’s unscented hand lotions for gardening.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature is a huge influence. I think that’s probably true for most poets. And I view cities and city life as the other side of that coin. I love reading or writing an urban pastoral, as much as that sounds like an oxymoron. History influences me a lot, since I’ve worked quite a bit in historical research and education. The Working Class History book and podcast have inspired quite a bit of my work. I also listen to music while drafting, especially Mitski and Phoebe Bridgers.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I want to write in a way that feels as fantastical as children’s stories felt when I was growing up. It’s hard to find that feeling as an adult. As a kid, the books that made me feel that way included The Secret World of Og and the Bone graphic novels, among many others. The sense of world-building and atmosphere were really strong in those. Novels I’ve read as an adult that made me feel a similar sense of wonder include French Exit, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, Bel Canto, and basically everything by Nicola Maye Goldberg. They aren’t similar in form or content to the stories I read as a child, but they install a comparable sense of wonder and surprise, which I think is difficult to do in a book written for adults.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want to publish a novel. I want to be a Gucci poet — one of those poets who is invited to Gucci parties via a confusing high-fashion invitation. I want to make a short film.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d honestly love to act and perform more. I get a real runner’s high from being on stage or in front of a camera. I just love to play pretend.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The first job I ever wanted to have was wizard. Once I found out that that wasn’t an option, writer was the next best thing. I wanted to create. Books were a huge comfort and constant in my childhood. Once I figured out how books were made — that they didn’t just spontaneously appear out of nothing — I wanted to be the person who made them.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I watch a lot of A24. Bodies Bodies Bodies , Marcel the Shell With Shoes On , and Everything Everywhere All At Once all blew me away. For books, I actually reached out to the authors of some of my favourite recent releases for my book blurbs. If you have a chance to pick up My Grief, The Sun by Sanna Wani; Exhibitionist by Molly Cross-Blanchard; and All Day I Dream About Sirens by Domenica Martinello, then please read all three.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on my next poetry collection, which hopefully will be my thesis. I’m also working on two novels that I’m really excited about.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 10, 2023

Ben Estes, ABC Moonlight

With empathy as the cornerstone

of good design, let’s look there for meaning,

down into this sloping bowl of a field

funneling into my rainbow-painted tunnel.

Where was the nuance? (“Twelve Folded Poems”)

The latest from Kingston, New York poet, editor and publisher Ben Estes is

ABC Moonlight

(Kingston NY: The Song Cave, 2022), following the chapbooks

Lamp like l’map

(2009), Cymbals (2010),

The Strings of Walnetto Arrangements

(2011), and 8 Poems (2012) as well as his full-length debut,

Illustrated Games of Patience

(The Song Cave, 2015) [see where I mentioned such here]. Set in three sections—“Twelve Folded Poems,” “Sixteen Pickup Pocket Quarry” and “A Shadow Theater”—the collection opens with an alternating sequence of poems numbered “1” and “2,” flipping back and forth across twenty-four individual poems set in pairs. “There wasn’t yet a sun.” the third poem (and the second poem titled “1”) in the sequence offers, “The sky was still empty. // The man who did this job / before me could stand so quietly. // He could make a whistle from the seed of any fruit. / Once he made a kite out of newspaper // and he told stories about the stars, and about the earth. / He told them to pass the night, // and because his heart was a reflection / in the soul of the world.” The poems offer a binary that evades easy narrative, turning in on itself even as it progresses. And yet, Estes’ poems, both in this particular sequence and throughout the collection, display a cadence of ease even across longing and heartbreak, through repetition and rhythm, almost held as a metronome tic of accumulation and pinpoint accuracy. Or, as the opening poem to the opening sequence reads, in full:

The latest from Kingston, New York poet, editor and publisher Ben Estes is

ABC Moonlight

(Kingston NY: The Song Cave, 2022), following the chapbooks

Lamp like l’map

(2009), Cymbals (2010),

The Strings of Walnetto Arrangements

(2011), and 8 Poems (2012) as well as his full-length debut,

Illustrated Games of Patience

(The Song Cave, 2015) [see where I mentioned such here]. Set in three sections—“Twelve Folded Poems,” “Sixteen Pickup Pocket Quarry” and “A Shadow Theater”—the collection opens with an alternating sequence of poems numbered “1” and “2,” flipping back and forth across twenty-four individual poems set in pairs. “There wasn’t yet a sun.” the third poem (and the second poem titled “1”) in the sequence offers, “The sky was still empty. // The man who did this job / before me could stand so quietly. // He could make a whistle from the seed of any fruit. / Once he made a kite out of newspaper // and he told stories about the stars, and about the earth. / He told them to pass the night, // and because his heart was a reflection / in the soul of the world.” The poems offer a binary that evades easy narrative, turning in on itself even as it progresses. And yet, Estes’ poems, both in this particular sequence and throughout the collection, display a cadence of ease even across longing and heartbreak, through repetition and rhythm, almost held as a metronome tic of accumulation and pinpoint accuracy. Or, as the opening poem to the opening sequence reads, in full: Dear Nature,

did love make me?

Estes’ accumulations shape and form narrative out of a sequence of pinpoints, reminiscent (in form, at least) to the work of Philadelphia poet ryan eckes, or even across the work of the late American poet Robert Creeley: one phrase following and threading immediately after and upon another. As Estes writes near the end of the second section/sequence: “with you this life who // as a kid thought // could be ours you & me // in the world riding alongside // everything but all of it up broken // in my life I could never // admit equal to everything // I had taken or been given ever since [.]” Estes manages subtle moments and phrases, some of which rattle, others that sink deep in the skin. In many ways, this is a book-length tryptich on longing and heartbreak, loss and recollection, attempting to clarify and document the threads of how one gets from there to here, composing long stretches of narrative across what might be described as a thousand individual accumulated and finely-hewn points. “before your things,” he writes, “were gone i guess // you had too much // else to say in order // to say goodbye [.]”

February 9, 2023

Jason Purcell, swollening

fertility

I pleasure over a row of white caps containing themselves. I tongue my own holes. Dislodge a tooth with a filling in it and grind it out to see its cavern, pushing against the walls of enamel with my thumb until the entire structure of the filling crumbles. Gape it enough that it splits in two, a thick rush of saliva on the tongue, alkaline and sweet. Holding my own dead self in my hands. An artifact of neglect that rots and teems with life. The slick of the mouth, its dirty floor mushrooming, iridescent beetles just under the log, under the filling’s wet dark suddenly lifted, skeletal scuttling from the searching sun, from the rising dental light.

From Edmonton poet and bookseller Jason Purcell comes the full-length debut,

swollening

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022), a collection that “rests at the intersection of queerness and illness, staking a place for the queer body that has been made sick through living in this world.” swollening is built as three sections of first person lyric narratives, and Purcell composes poems that echo and flow into each other; poems that ripple across surfaces, running deep into each other across the length of the lake of this book. “Even this memory is queer.” he writes, to close the poem “North of Nipissing Beach,” “These are the terms of this space.” And through such, Purcell sets down the terms of his lyric from the offset: composing poems that swirl around a central core of illness, writing a devastating array of dental pain and carnage (I can’t tell if it is irony or purpose that has me posting this review on the morning of my own latest dental appointment), but one that utilizes illness as a way through which to examine what feels the book’s true purpose: to examine and articulate loss, grief and growing pains. Purcell writes the breaks, pains and pauses that come with simply becoming an eventual self-realized adtult (including the threads of growing up and coming out), and allowing grief and trauma its own space to move through, and be moved through in turn. Purcell writes on first loves, masculinity, a father’s response and a mother’s love, and the distance of siblings. “How to retrace / a relationship and then to stay present?” he asks, to close the poem “Kids in the back seat,” “How to repair? I always push away / from the pain, but she reaches through and can see / me, can connect what I can’t by a very long road.” swollening is not simply a book around illness and pain but a collection of poems on attempting to understand the path travelled-to-date, sketched across childhood recollection, burgeoning queerness and heartbreak, composed as much as a way through understanding and a way forward as an articulation of where he currently stands, now.

From Edmonton poet and bookseller Jason Purcell comes the full-length debut,

swollening

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022), a collection that “rests at the intersection of queerness and illness, staking a place for the queer body that has been made sick through living in this world.” swollening is built as three sections of first person lyric narratives, and Purcell composes poems that echo and flow into each other; poems that ripple across surfaces, running deep into each other across the length of the lake of this book. “Even this memory is queer.” he writes, to close the poem “North of Nipissing Beach,” “These are the terms of this space.” And through such, Purcell sets down the terms of his lyric from the offset: composing poems that swirl around a central core of illness, writing a devastating array of dental pain and carnage (I can’t tell if it is irony or purpose that has me posting this review on the morning of my own latest dental appointment), but one that utilizes illness as a way through which to examine what feels the book’s true purpose: to examine and articulate loss, grief and growing pains. Purcell writes the breaks, pains and pauses that come with simply becoming an eventual self-realized adtult (including the threads of growing up and coming out), and allowing grief and trauma its own space to move through, and be moved through in turn. Purcell writes on first loves, masculinity, a father’s response and a mother’s love, and the distance of siblings. “How to retrace / a relationship and then to stay present?” he asks, to close the poem “Kids in the back seat,” “How to repair? I always push away / from the pain, but she reaches through and can see / me, can connect what I can’t by a very long road.” swollening is not simply a book around illness and pain but a collection of poems on attempting to understand the path travelled-to-date, sketched across childhood recollection, burgeoning queerness and heartbreak, composed as much as a way through understanding and a way forward as an articulation of where he currently stands, now.

February 8, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brian Ang

Brian Ang wrote The Totality Cantos (Atelos 2022). totalitycantos.netincludes the complete text, links to buy copies, and a generator that randomizes assemblages of its one thousand sections. Interview for Eastwind Books of Berkeley. Prose: Brian Ang’s Favorite Books and Assemblage Poetics. Readings:

The Totality Cantos

: Brian Ang and Alex Abalos on the Avant-Garde, with Caleb Beckwith at Woolsey Heights, and with Anne Lesley Selcer at Your Mood Gallery.Current poetic project: A Thousand Records, open to the totality of music.

Brian Ang wrote The Totality Cantos (Atelos 2022). totalitycantos.netincludes the complete text, links to buy copies, and a generator that randomizes assemblages of its one thousand sections. Interview for Eastwind Books of Berkeley. Prose: Brian Ang’s Favorite Books and Assemblage Poetics. Readings:

The Totality Cantos

: Brian Ang and Alex Abalos on the Avant-Garde, with Caleb Beckwith at Woolsey Heights, and with Anne Lesley Selcer at Your Mood Gallery.Current poetic project: A Thousand Records, open to the totality of music. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, The Totality Cantos, has changed my life by helping me be in the world by signifying what I’m about. It is continuous with my previous work through bringing together methods in my previous work such as sampling, word counting, and the randomizing generator, but more extensively, and through articulating my poetics concerns in practice.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry blew my mind first. I read T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in college and was amazed by its assemblage of discourses.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I conceived of The Totality Cantos in 2011 and drafted half of the poem through 2013. I focused on editing and criticism through 2017; developing my poetics revealed inadequacies in the poem’s method and I discarded its drafts and restarted it that year. Once I figured out how to write it, writing came quickly. Of the poem’s one hundred cantos, I set a production rate of a canto every ten days, completing two-fifths of the poem in a year. I then adjusted the rate to a canto every two weeks and completed the poem on New Year’s Eve 2020. This writing was close to its finished form, the product of planning.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem begins for me with conceiving its concept and form. Right now I’m only interested in writing book-length poems.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings are part of my creative process in that they are opportunities to blow people’s minds and bring creativity into the world. I enjoy doing them.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes. My work is concerned with questioning the present and its possibilities for poetics. I’m interested in how totality is organized and could be reassembled otherwise.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I see the current role of the writer in larger culture as aiming to articulate what is singular from the position of the writer, in contrast to other roles. The writer can act with language and minimal equipment.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. Atelos invited me to contribute to their series in 2014 and that was constitutively essential to writing The Totality Cantos in knowing where it would be published. Difficult in that working with others is challenging because of differing perspectives.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“The challenge of creativity, as far as I’m concerned, is to move towards the greatest thought that you can think of.” Anthony Braxton, my favorite musician.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s been easy for me to move between poetry and prose because I focus on one at a time. From 2013 to 2017 I focused on prose, especially writing my “Post-Crisis Poetics” essay. From 2017 to 2020 I focused on poetry, writing The Totality Cantos. In 2021 I wrote the prose piece “Assemblage Poetics,” published in Rabbit: a journal for nonfiction poetry. In 2022 I began writing my next book of poetry, A Thousand Records, open to the totality of music in five hundred sections. I see writing poetry and prose as relays for each other, furthering each other’s possibilities. My poetry writing is fast, my prose writing is slow.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I set schedules for completing certain amounts of writing in certain amounts of time: a certain amount every day, every week, and by certain dates. A typical day for me begins with making food, giving me energy to write for as long as I can. When I have free time in a day I prioritize writing. A full day spent writing is a good day to me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

My writing doesn’t stall. I have enough ideas to work on for years. It’s mainly a matter of organizing my life to have energy and time to write. Books, family, food, friends, and music are energy sources for me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My parents’ cooking.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I try to be influenced by everything. I’m especially influenced by food, music, philosophy, and politics.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Louis Zukofsky, Jackson Mac Low, Gilles Deleuze, Bruce Andrews, and writers I consider in my “Assemblage Poetics” essay: Caleb Beckwith, a.j.carruthers, Tom Comitta, alex cruse, Paul Ebenkamp, Angela Hume, Carrie Hunter, Michael Leong, and Divya Victor.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to find a partner who we’re mutually right for.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Musician.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t have to rely on others to write. It’s never let me down. It’s how I’ve best been able to be creative. What I do in it is mine.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Let's Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste by Carl Wilson. Film: Everything Everywhere All at Once directed by Daniels.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Promoting The Totality Cantos and “Assemblage Poetics,” writing A Thousand Records, and editing an Assemblage Sampler to develop “assemblage poetics” further.

February 7, 2023

Sarah Heady, Comfort

: o love you are large

it mellows me out

warm purpose but no expectation

dissection of the plane

that is my chest a mail-order cure-all that comes

with a snap of my fingers a sharp

in-draw of breath

but i don’t stop

painting a room when

the walls are covered

—give me more credit than that (“: DAY :”)

Produced as a triptych of fragment-accumulations—“: sunup :,” “: day :” and “: dusk :”—San Francisco poet and editor Sarah Heady’s [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here] latest poetry collection is the full-length Comfort (New York NY: Spuyten Duyvil, 2022), a collage/response work that plays off the language of a New England journal produced for farm housewives. As she writes to open her “NOTES” at the back of the collection:

Comfort magazine was published in Augusta, Maine between 1888 and 1942. Its tagline was “The Key to Happiness and Success in Over a Million Farm Homes.” Aimed at rural housewives, it began as a thinly-veiled vehicle for selling Oxien, a cure-all snake oil, with subscribers receiving discounts and bonus gifts for signing up their female friends—perhaps an early multi-level marketing scheme. At the same time, it provided a valuable source of virtual companionship for women who led isolated lives all across the United States. Much of the found language in this book comes from issues of Comfort published in the 1910s and 1920s.

The initial structure of the collection, as she notes as well, was influenced by Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy, specifically her

marybones

(Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2013) [see my review of such here]. To open her “ACKNOWLEDGMENTS,” Heady notes that: “Comfort would not exist without the work of Pattie McCarthy. I am indebted especially to her book Marybones, which directly inspired the form of this book’s prose blocks. Thank you for showing me new ways to work with found language and the historical record.” On her part, Heady collages elements from the archive and found language to weave together a boundless expansion of fragments and accumulations, pinpoints and sweeps of prose lyric. As with McCarthy, Heady writes around the marketing directed towards historical women, offering insight into the possibilities of the realities of their labour and lives, and the ways that they were depicted through this particular journal. The poems in Comfort articulate that divide through collage and collision of found and archival material, propelled through language and a staccato of disconnect that thread their way across the length and breadth of her book-length canvas. There is something interesting in how her exploration through a borrowed structure opens her lyric, allowing for the spaces between and amid her lyric to be as populated and powerful as the words she sets down. Blending concrete description and scattered collage, she writes of rural women and the weather; she writes of recipes and the wish for a new stove, all stretched taut across each distance like a drum. As she writes:

The initial structure of the collection, as she notes as well, was influenced by Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy, specifically her

marybones

(Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2013) [see my review of such here]. To open her “ACKNOWLEDGMENTS,” Heady notes that: “Comfort would not exist without the work of Pattie McCarthy. I am indebted especially to her book Marybones, which directly inspired the form of this book’s prose blocks. Thank you for showing me new ways to work with found language and the historical record.” On her part, Heady collages elements from the archive and found language to weave together a boundless expansion of fragments and accumulations, pinpoints and sweeps of prose lyric. As with McCarthy, Heady writes around the marketing directed towards historical women, offering insight into the possibilities of the realities of their labour and lives, and the ways that they were depicted through this particular journal. The poems in Comfort articulate that divide through collage and collision of found and archival material, propelled through language and a staccato of disconnect that thread their way across the length and breadth of her book-length canvas. There is something interesting in how her exploration through a borrowed structure opens her lyric, allowing for the spaces between and amid her lyric to be as populated and powerful as the words she sets down. Blending concrete description and scattered collage, she writes of rural women and the weather; she writes of recipes and the wish for a new stove, all stretched taut across each distance like a drum. As she writes: is waiting for the mails. is disappointed wishing they’d write more often. is seeing the ghost of the fence. is mending until plum midnight. is three nights setting a bucket of water on the bedroom floor to collection miasmas. is exhausted, entirely worn away. is making the best of & making the beds. is scratching along the riverbed for finds : from buckshot to walnuts, submergence, emergence : i therefore desire more solid comfort : agate, cornelian, jasper, alluvial soil. is roaming the pomological fair, pressing into the skins. is detecting a thickness to the season. is checking future wind with saplings, measuring winter minima. is all sunsets & auroras & how much farther westward he is not prepared to say : the drift, the lacustrine, or loess, alluvium : puzzles : colored pictures or pieces of pictures : catarrh & lumbago, falling of the womb : oval, oblong, obvate, abruptly pointed in a short, close cluster : we have no connection whatever with any other company : dried currants, eggs repacked : putty in bladders & batten per linear foot. oxien was, and still is, the only true food for the nerves. it ranges in thickness : perfectly homogenous, exposed, rubbed fine, the size of a shot : COMFORT : “the key to a million and a quarter homes” : a strengthener & a friend to women : a truly formidable list (“: SUNUP :”)

February 6, 2023

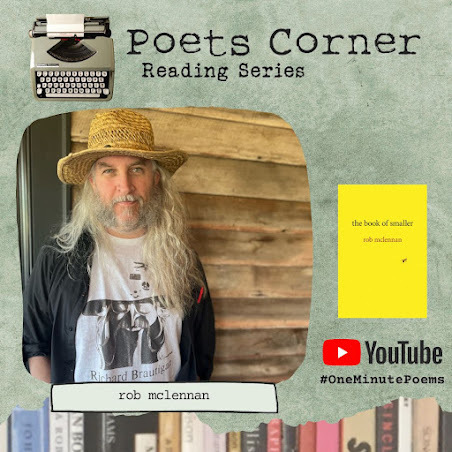

two upcoming (zoom) readings: Feb 15 (Poets Corner Reading Series) + Mar 15 (Lunch Poems at SFU)

So apparently I'm reading (virtually) twice in Vancouver over the next few weeks!

So apparently I'm reading (virtually) twice in Vancouver over the next few weeks!February 15: reading at Poets Corner Reading Series with Zoe Dickinson, Hannah Yerington and Catherine Lewis (a hybrid event, so in-person is possible for those in the Vancouver area). And there's even an open set! And I even recorded a video of me reading a short poem for the sake of their promotion, which they've posted to their YouTube channel. 7:30pm Pacific time. And who knows? I might even have a new chapbook by then.

March 15 (my birthday!): reading at Lunch Poems at SFU with Calgary poet and publisher Kyle Flemmer! noon-1pm Pacific time.

February 5, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Erica McKeen

Erica McKeen

was born in London, Ontario. She studied at Western University, and her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, longlisted for the Guernica Prize, and shortlisted for The Malahat Review Open Season Awards. Her stories have been published in PRISM international, filling Station, The Dalhousie Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Vancouver, British Columbia on the unceded and ancestral lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Peoples.

Tear

is her first novel.

Erica McKeen

was born in London, Ontario. She studied at Western University, and her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, longlisted for the Guernica Prize, and shortlisted for The Malahat Review Open Season Awards. Her stories have been published in PRISM international, filling Station, The Dalhousie Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Vancouver, British Columbia on the unceded and ancestral lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Peoples.

Tear

is her first novel.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

At the time of writing this interview, there is still a week before my first book hits the shelves on September 6th, so I’m sure the response I give now will be vastly different than the one I would give in a couple of months. So far, the writing, editing, and promotion of my first book has been such a validating experience, and more than anything I have learned to trust my instincts while writing and to reach out to others for help. (Essentially, I’ve learned not to hide away in a psychological writer’s cave of self-doubt.) As a result, my more recent work feels broader, in a sense—more willing to engage with topics that I would have previously felt to be too big or out of my reach.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

For a long time I wrote in all genres (fiction, poetry, and creative non-fiction), but I soon became uncomfortable with the closeness of poetry and non-fiction. I didn’t enjoy writing explicitly about myself, and the work I produced was often flat or overly dramatic. Fiction, in contrast, allows me to use the stylistic techniques of both poetry and non-fiction (the lyricism of poetry and the narrative considerations of non-fiction) while simultaneously being able to filter my experiences through the lenses of surrealism, horror, and the otherworldly. Fiction feels unending and expansive to me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Writing projects happen slowly for me. Ideas that could constitute something as large as a novel are shadowy at first and hang around ill-formed in notebooks until they’re combined with other ideas and become “thick” enough. I like to take my time with every sentence and often self-edit (despite the advice from every writer in history telling me not to do this). I like to pause and reread. Fortunately, because of this habit, my projects are cohesive and decently polished in their first-draft form.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Despite recently completing a project that combined short stories into a larger narrative and manuscript, I usually know from the beginning that I’m working on a “book”—I like to have a central idea, concept, or question in mind while writing. A work of prose often begins for me with an image that is representative of this central question. Everything sprawls from there.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings aid my creative process in the way that they connect me with other writers and thinkers in the community—they help me to understand that I’m a part of a larger network of creative work, and that I’m not entirely on my own (writing can be lonely work). I mostly enjoy doing readings in retrospect, after they’re finished. Although I’ve “performed” in various ways throughout my life, I always feel more than a little anxious about presenting myself to other people.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Is it possible for human beings to know/understand one other? What about the natural world? Can they know/understand themselves?

Is this knowledge helpful, or does it overburden?

Is it possible to find peace amid traumatic memory? What does that feel like? Are human beings actually able to change?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I can only speak for fiction writing, but for that I believe the role of the writer is to shape experience and make it more manageable. I see it as a healing craft. When I write, I want to soothe, and, when I read, I want to be soothed. This doesn’t mean that the writing must be relaxing, or quiet, or peaceful. It means that I want to witness something moulded satisfyingly into being. I don’t need answers, just texture and intention

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Working with an outside editor is essential. I need another brain (or many other brains) to poke and mash and stretch my writing. I find the process of working with an editor to be challenging but rewarding—always worthwhile. I should note, however, that I’ve had some amazing editors, which I’m sure makes the experience more enjoyable.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Trust someone as far as you can throw them.” (I’m waiting for it to be proven wrong.)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I love the novel genre and have always wanted to focus my attention on longer pieces of writing, so transitioning from short stories to the novel was an exciting change for me. I enjoy digging deep into character backstory, which you can’t always do in a short story, and I feel driven by the challenge of sustaining a compelling narrative over so many pages. My brain appreciates the rhythm and consistency of returning to the same project day after day.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A typical day begins early with green tea and a book, and then a walk with my dog. I don’t have a writing routine because my schedule changes so frequently depending on school or work. The last time I had a schedule that remained the same for more than a year was in high school. I have learned to be gentle with myself: I write when I can, and when I’m not too tired.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I turn to really good books, and I turn to walking. The walking part is easy because you just have to go outside and do it, wander around with the Notes app on your phone until the words start to come. Finding a really good book can be more difficult and takes time, but there’s always one out there. Sometimes when I’m really stuck I combine the two and read while walking.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Hay and dust and sun-bleached grass. It reminds of me of my grandma’s run-down farm that my brothers and I used to play at as children.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My work is primarily influenced by books, movies, and TV. Essentially, I draw a lot of inspiration from other stories, even those told in passing by friends and colleagues. I love anecdotes—the brief, punchy surprise of them—and often include similar “flash narratives” in my writing.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Virginia Woolf—always Virginia Woolf! And, in no particular order, Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, Everything Under by Daisy Johnson, The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje, All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews, writings on hauntology by Mark Fisher, and “Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang have had a huge impact on me.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Have a child. Live in nature. Travel the world more thoroughly.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I must have another occupation while working as a writer (both for financial and psychological reasons). My job for a while now has been teaching, but presently I’m transitioning to librarian and archival work because that profession requires less unpaid overtime on a day-to-day basis. I suppose if I was more mathematically inclined, I would have liked to work as an architect.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s difficult for me to the answer this question because I’ve wanted to write since before I was able to read or put words on a page. The best answer I can provide is that, after beginning my university education in psychology (and then quickly switching out of it), I found that writing satisfied my compulsion to understand human beings intensively, thoroughly—while also not demanding any concrete or evidence-based conclusions. Writing allows me to exist in a space of uncertainty and complexity that other aspects of my life do not.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Road by Cormac McCarthy and a re-watch of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a novel that is currently in its very small, fetal stages. Set in Vancouver, it will be about private schools, class differences, memory and inheritance, unusual forms of love, suicide, and octopuses.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 4, 2023

Tony Mancus, All the Ordinariness

How magic is performed for an audience

but practiced alone so many times

it becomes mundane (“AFTER ECHO”)

I was curious to see Colorado poet and editor Tony Mancus’ full-length debut,

All the Ordinariness

(Grand Rapids MI: The Magnificent Field, 2022), following the publication of a handful of chapbooks. Set with an opening untitled single-page poem and three lengthy accumulations of fragments, sentences and lyric collage—“AFTER ECHO,” “HEARTBROKER” and “CROSSING OUT NOW”—All the Ordinariness holds an expansive lyric, blending words that play at rhythm, sound and meaning through small points of collision. “pick a passthrough and feel the imposter,” he writes, as part of the opening poem, “post up inside set your bones // right still [.]” The poems are constructed as accumulations and even collisions of sentences, bursts, breaks and phrases, one atop another to form and shape a kind of disjointed meaning, and disjointed narrative. This book-length poem writes on the daily and the immediate, but through the concrete and abstract of language and ideas that propel the line as much as the specifics of daily action. There is such a staggered musicality to his rhythms, and something quite compelling on how this poem writes around and through particular narrative space, enough to outline what might not otherwise be seen, or even there. As he writes as part of the second section: “Saying something makes it real. Saying nothing makes it quiet. All the volleys / built into space there.” Or, a few pages prior:

I was curious to see Colorado poet and editor Tony Mancus’ full-length debut,

All the Ordinariness

(Grand Rapids MI: The Magnificent Field, 2022), following the publication of a handful of chapbooks. Set with an opening untitled single-page poem and three lengthy accumulations of fragments, sentences and lyric collage—“AFTER ECHO,” “HEARTBROKER” and “CROSSING OUT NOW”—All the Ordinariness holds an expansive lyric, blending words that play at rhythm, sound and meaning through small points of collision. “pick a passthrough and feel the imposter,” he writes, as part of the opening poem, “post up inside set your bones // right still [.]” The poems are constructed as accumulations and even collisions of sentences, bursts, breaks and phrases, one atop another to form and shape a kind of disjointed meaning, and disjointed narrative. This book-length poem writes on the daily and the immediate, but through the concrete and abstract of language and ideas that propel the line as much as the specifics of daily action. There is such a staggered musicality to his rhythms, and something quite compelling on how this poem writes around and through particular narrative space, enough to outline what might not otherwise be seen, or even there. As he writes as part of the second section: “Saying something makes it real. Saying nothing makes it quiet. All the volleys / built into space there.” Or, a few pages prior: Here this bag of stone, here a cricket saw, a claw from a crayfish, the log to jump from into a hole filled with water 20 feet or something more. Thin nature into its slivers. Here a roadsign for Shoneys gone dust and disuse, a boy wearing a confederate flag for a hat, the fear boned into a few dayswimmers at what would happen. When not if. The world we share and don’t.

I am putting another basket full of eggs in front of you. I am asking them to talk, tell me a story little round, make the news, change the channel, buy the fabric softener and color the walls with your insides. I don’t expect reason, I don’t inspect the cracks and delays, just notice how time changes. A catalogue.

February 3, 2023

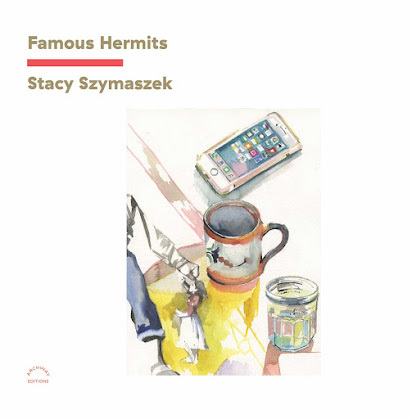

Stacy Szymaszek, Famous Hermits

New York was hell on earth today

trash fire on the F track a black substance perhaps

mastic asphalt oozing from vents along the C/E

but I’m only reading about it I slipped

on the ice down to one knee they don’t believe in salt

or plows and I forgot the chains for my feet “At Night the States”

closes with Montana a word I have always liked the state

grows on me like adulthood still I confess I hate hot

cereal out of a pot at midnight and it tasted

like and was the same color as the rug in here so when a glob

fell I left it there so I wouldn’t lose my thought it was Marlowe’s

birthday yesterday and I heard the ground hog

insinuated early spring my love cares to visit the pleasures

of going down on me like a vine

I spiral all over the house (“CENTURION FACE”)

The latest from Hudson Valley, New York poet Stacy Szymaszek is

Famous Hermits

(Brooklyn NY: Archway Editions, 2022), following more than a half-dozen trade collections, as well as numerous chapbooks, including

austerity measures

(Fewer & Further Press, 2012) [see my review of such here],

JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST

(Projective Industries, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals

(Albany NY: Fence Books, 2016) [see my review of such here], as well as the more recent

The Pasolini Book

(NC/NY: Golias Books, 2022). The eleven poems that make up Famous Hermits extend Szymaszek’s engagement with a variation on the day book or lyric journaling, furthering a thread of New York School poetics (I’ve been reading and rereading Bernadette Mayer lately, so can really see the linkages) across lengthy lines and sentences in an expansive and even continuous ongoingness (think, also, of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, although it seems less likely Szymaszek aware of his decades of work, or elements of Fred Wah). There is something compelling with Szymaszek’s use of personal material (whether actual or otherwise), and one might even see a way how her books could fit neatly against each other across an autobiographic spectrum; it would be interesting for someone to more closely examine the length and breadth of her published work to chart the evolution of her particular variation of the lyric journal. She utilizes the details of reading, living, responding and being as the building blocks through which her poems emerge, propelled by language and rhythm, a cadence that flows easily across and down each page. “in the sloppy middle of life,” she writes, to close the three-page poem “STOP MAKING PEACE,” “is a dialogue in view of Santa Catalina // I woke to find // an elder woman selling her soap /// mine has more / pine tar / in it / because frankly / I am / a master // of my trade [.]”

The latest from Hudson Valley, New York poet Stacy Szymaszek is

Famous Hermits

(Brooklyn NY: Archway Editions, 2022), following more than a half-dozen trade collections, as well as numerous chapbooks, including

austerity measures

(Fewer & Further Press, 2012) [see my review of such here],

JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST

(Projective Industries, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals

(Albany NY: Fence Books, 2016) [see my review of such here], as well as the more recent

The Pasolini Book

(NC/NY: Golias Books, 2022). The eleven poems that make up Famous Hermits extend Szymaszek’s engagement with a variation on the day book or lyric journaling, furthering a thread of New York School poetics (I’ve been reading and rereading Bernadette Mayer lately, so can really see the linkages) across lengthy lines and sentences in an expansive and even continuous ongoingness (think, also, of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, although it seems less likely Szymaszek aware of his decades of work, or elements of Fred Wah). There is something compelling with Szymaszek’s use of personal material (whether actual or otherwise), and one might even see a way how her books could fit neatly against each other across an autobiographic spectrum; it would be interesting for someone to more closely examine the length and breadth of her published work to chart the evolution of her particular variation of the lyric journal. She utilizes the details of reading, living, responding and being as the building blocks through which her poems emerge, propelled by language and rhythm, a cadence that flows easily across and down each page. “in the sloppy middle of life,” she writes, to close the three-page poem “STOP MAKING PEACE,” “is a dialogue in view of Santa Catalina // I woke to find // an elder woman selling her soap /// mine has more / pine tar / in it / because frankly / I am / a master // of my trade [.]” “I am I because my landlord is my accountant,” she writes, as part of the poem “CENTURION FACE,” “he knows me / in the tyranny of paperwork gesticulate over a plank / of leather [.]” Szymaszek stitches together her poems-as-collage, travelling across an expansive distance of daily offerings, deep reading and language; hers is an exploration as much temporal, writing personal space both internal and external, rippling well beyond the immediate into wider considerations of city, landscape and culture. In certain ways, this is also a collection coming to terms with relocation, moving out of a lengthy period of New York City for the Hudson Valley, offering a journal on and around such an enormous personal and professional shift; one that feels akin to hermiting, perhaps, which is why she invokes so many across the text. As the back cover offers: “The concept of the famous hermit is born out of a desire to experience integrity, to not go forgotten, yet with a fierce need to separate from liberal ideas of what poetry should publicy perform. She invokes other kindred artists such as Dante, Bob Kaufman, Tina Modotti, and Jean Seberg as guisdes as she writes her own statements of renunciation and ultimately of middle-aged self-love.”