Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 97

March 4, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Danni Quintos

Danni Quintos

is the author of the poetry collection, Two Brown Dots (BOA Editions, 2022), chosen by Aimee Nezhukumatathil as winner of the Poulin Poetry Prize, and

PYTHON

(Argus House, 2017), an ekphrastic chapbook featuring photography by her sister, Shelli Quintos. She is a Kentuckian, a mom, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet. She received her BA from The Evergreen State College, and her MFA in Poetry from Indiana University. Her work has appeared in Poetry Magazine, Cream City Review, Cincinnati Review, The Margins, Salon, and elsewhere. Quintos lives in Lexington with her kid & farmer-spouse & their little dog too. She teaches in the Humanities Division at Bluegrass Community & Technical College.

Danni Quintos

is the author of the poetry collection, Two Brown Dots (BOA Editions, 2022), chosen by Aimee Nezhukumatathil as winner of the Poulin Poetry Prize, and

PYTHON

(Argus House, 2017), an ekphrastic chapbook featuring photography by her sister, Shelli Quintos. She is a Kentuckian, a mom, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet. She received her BA from The Evergreen State College, and her MFA in Poetry from Indiana University. Her work has appeared in Poetry Magazine, Cream City Review, Cincinnati Review, The Margins, Salon, and elsewhere. Quintos lives in Lexington with her kid & farmer-spouse & their little dog too. She teaches in the Humanities Division at Bluegrass Community & Technical College. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook, PYTHON (Argus House 2017) gave me something to hold and read from. It was published after I finished my MFA and was feeling a bit like I might not be a poet anymore. I think it acted as a reminder that I made something, that I could keep making. This was very different from my debut collection, Two Brown Dots (BOA Editions Ltd., 2022), which was from a well-respected, established press. My book felt almost unreal to me, like a big dream realized, especially to be published with BOA, whose books I've thumbed through and loved since I was a budding poet.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I think I didn't really know I was a "poet" until I had a poet call me one. I wrote poems in middle school and high school, but I also enjoyed writing fiction and non-fiction. When I was an undergrad and worked at Governor's School for the Arts in the summer of 2010, Mitchell L. H. Douglas put me in his phone as "Danni Quintos, Awesome Poet" and I was so humbled and surprised. The "awesome" part obviously was flattering, but being called a poet by someone who had taught me, who I respected as an established poet, made me believe it.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My writing is a very slow process. I am not a regimented writer and a lot of the non-writer parts of my life often overshadow the writer parts. My oldest poem in my book is probably from 2012, which was 10 years before the book was published. I had some very productive writing years during my MFA, but ultimately my poems weren't ready or maybe my full book wasn't ready until I worked on the manuscript with BOA and Aimee Nezhukumatathil, who selected my book for the Poulin Prize.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For TBD, I would say that it began more as a short pieces that became a larger project. I am currently working on a larger project that started as a few poems and bloomed into something bigger.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings! I enjoy the adrenaline of getting up there and sharing my work with people who are interested, I like the conversations that come from readings. I think I used to be afraid of readings because it felt really bare and scary. Now, I do think they're an important part of my process, especially reading with other writers I admire. It's good to hear what worked and take notes on how the audience reacted (or didn't) to know what I should hold onto.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I recently read Shelley Wong's interview in Poets & Writers and I think she had some really beautiful advice for folks looking to get their first collection published. "This is often a despairing, expensive, and vulnerable process because of the contest system. And you get only one debut. Research the presses you are already reading and supporting. Go for your dream publishers. Ask questions. Take your time, but also don’t let publication stop you from working on other projects and living your life. Stay connected with at least one writer friend by sharing work, showing up for each other’s readings, commiserating, and giving each other advice. Take a week to revise your book in a cabin. Carry your manuscript with you. Do public readings to test the work out loud. But also take breaks. Above all, be kind to yourself and others."

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to read the ones that made me love poetry: Li-young Lee, Lucille Clifton, Nikky Finney, Ellen Hagan, Sandra Cisneros. I like to do writing prompts with friends, other writers I admire and trust. I like to also knit and draw or watercolor to make weird mistakes or creations. Lately I've been enjoying finding an excerpt from a poem/poet I love and making an illustrated/watercolor broadside for that excerpt. Lynda Barry has some wonderful drawing and writing exercises that help me out of any funk.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Honeysuckle, freshly cooked steamed rice, garlic and onions frying in oil, fall leaves starting to decay, tomato vine

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think knitting has influenced my process a lot in that sometimes one must unravel an ugly or misshapen or just not right thing, despite hours of work. To acknowledge that the hours of work spent weren't wasted but a learning process toward something better, that seems very applicable to writing, drafting, editing, and letting go of the ugly or misshapen things we write. I also love drawing and reading graphic novels, but I think because I don't feel like my expertise is in this area there is more room to play and learn and once again, make something ugly or misshapen. I mentioned her before, but Lynda Barry is a major inspiration to me and her work helps me to embrace the weird and unknown.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I think returning to teachers and peers who taught me gets me really excited to make things and teach. I've loved reading Ross Gay's essay collections, Ellen Hagan's fiction and novels-in-verse, Joy Priest's poetry and essays, Nikky Finney's poetry and ephemera, and the debut poetry collections of my dear friends like Anni Liu ( Border Vista ), Su Cho ( The Symmetry of Fish ), Kien Lam ( Extinction Theory ), Jan-Henry Gray ( Documents ), and Marianne Chan ( All Heathens ). I also love to return to Ai, Lucille Clifton, Aracelis Girmay, and Ruth Stone, for teaching students and myself.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd like to make something with poems + illustrations or images. I want to write another book.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, my day job is teaching at a community college, which I really love. Maybe in the multiverse I would've been in the nonprofit world. Don't tell my grandmother, but maybe I would've gone to law school.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I've always loved writing and storytelling. I used to make little books as a kid, usually they would be backwards because I'm left-handed. I think I stuck with writing because I had teachers recognize me and tell me I was good at it. Also because I loved it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great book: Alejandro Varela's The Town of Babylon or Ross Gay's Inciting Joy

Last great film: I enjoyed Nope and Emily the Criminal .

19 - What are you currently working on?

Currently working on a teen novel-in-verse! Oof, learning a lot about plot and conflict and character arc!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 3, 2023

Trevor Ketner, The Wild Hunt Divinations: a grimoire

[When forty winters shall besiege thy brow]

gowns web (herb hysteria)—let’s thin flowery

then—gaudy bicep—insistent herd—leaf dyed

to holy doorway—hunt syrups—doze—given

that i swallow debt, let me whorl—feed lard

/ ale / ill breath—they get eye winks—husband,

of thudhurt, eyeray, saltwar—sheets yell,

tan—nude hyphen—i knot woe; sinewy, it sees

fingernails (limp waters, a hand sea), leather sets,

he-messes—hewed out virus—debauchery: try a mop

or a match—i hot—i lucid—i wonderflush—stiffens:

exoskeleton / cum—my cuddly human mass—la,

sings a boyish brute in his coven—cut—yep,

hood him—we want a wren duet, to be shelter—

a cold thud (trans sob / melt)—oh welt / honeyed wife.

Manhattan-based American poet Trevor Ketner’s second full-length collection, following

[WHITE]

(The University of Georgia Press / Broken Sleep Books, 2021), is

The Wild Hunt Divinations: a grimoire

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), a book composed as a homolinguistic (English to English) translation of William Shakespeare’s one hundred and fifty four sonnets. As the back cover offers: “Comprised of 154 sonnets, each anagrammed line-by-line from Shakespeare’s sonnets, the book refracts these lines through the thematic lens of transness, queer desire, kink, and British paganism.” One might argue that the true measure of art or form is in the range of its mutability (of which the sonnet itself is the perfect example), or perhaps William Shakespeare’s work have such a hold on the western attention that we can’t help but return to, as generations of writers across the past four centuries continue their attempts to rework or trouble Shakespeare’s language or attentions, seeking new ways through which to approach or respond. With echoes of Tom Stoppard writing the spaces only he could see through Hamletto compose his infamous play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966), the most obvious comparison to Ketner’s collection might be with Vancouver poet, editor and critic Sonnet L’Abbé Sonnet’s Shakespeare (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], through which she reworked and subverted the same one hundred and fifty-four sonnets through a form of “reverse erasure” to explore matters of the canon, race, identity and colonialism.

Manhattan-based American poet Trevor Ketner’s second full-length collection, following

[WHITE]

(The University of Georgia Press / Broken Sleep Books, 2021), is

The Wild Hunt Divinations: a grimoire

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), a book composed as a homolinguistic (English to English) translation of William Shakespeare’s one hundred and fifty four sonnets. As the back cover offers: “Comprised of 154 sonnets, each anagrammed line-by-line from Shakespeare’s sonnets, the book refracts these lines through the thematic lens of transness, queer desire, kink, and British paganism.” One might argue that the true measure of art or form is in the range of its mutability (of which the sonnet itself is the perfect example), or perhaps William Shakespeare’s work have such a hold on the western attention that we can’t help but return to, as generations of writers across the past four centuries continue their attempts to rework or trouble Shakespeare’s language or attentions, seeking new ways through which to approach or respond. With echoes of Tom Stoppard writing the spaces only he could see through Hamletto compose his infamous play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966), the most obvious comparison to Ketner’s collection might be with Vancouver poet, editor and critic Sonnet L’Abbé Sonnet’s Shakespeare (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], through which she reworked and subverted the same one hundred and fifty-four sonnets through a form of “reverse erasure” to explore matters of the canon, race, identity and colonialism. Ketner’s approach, obviously, works through a far different lens, although one that still aims to open, subvert and rework the perspective of those original infamous sonnets, and utilize those forms as a way through which to critique. Whereas L’Abbé lyrically stretched and smoothed over the jagged elements of Shakespeare’s patter, Ketner maintains a staccato trajectory of bounce and gymnastic leaps that reverberate across a remarkable string of tightly-wound phrases. As the author offers to open their “Notes” at the end of the collection: “These poems, what I call ‘divinations,’ were created with the assistance of an online anagramming tool and the source text of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets. The first line of the corresponding Shakespearian sonnet is borrowed as the title for each divination. Using the line as the unit of meaning, the rule I set was to anagram line-by-line, so each line of the divination has all the same letters as the corresponding line in the Shakespearian sonnet.” Across a joyful space of patter, patterns and propulsive sound, Ketner writes a lyric energized as much as the original might have appeared to contemporary audiences in the Elizabethan era, updating content, concerns and perspectives, but allowing the elements of what might be possible through a language that could never have been previously imagined. “bled violent theme (tie testes, vibrate,” Ketner writes, to open the poem “[‘Tis better to be vile than vile esteem’d,],” “probe, observe)—he, erect in gown (into chafe)— / deerhush meets dawn’s cool pelt—i adjust his / to theirs—boy bulge softening—burn eye / (the letter for)—house’s dreadful holysea sway— […].”

March 2, 2023

George Bowering, Good Morning Poems

Most of a century ago, when my mother was a schoolgirl, Mr. Longfellow was still considered a serious and accomplished poet. He sold us Hiawatha and Evangeline and the midnight ride of Paul Revere, after all. He was growing up while Wordsworth was being groomed as poet laureate, and he soon set about making himself the most popular poet in the U.S.A. This would mean combining patriotism and easily consumable narratives and verse forms. He let it be known that his family came over on the Mayflower, and for most of his life he lived in George Washington’s old wartime headquarters. It worked, as he became the first U.S. poet to make a fortune by his verses. Most literature U.S. Americans know the first two lines of “The Arrow and the Song.” When I first heard the poem I thought it was pretty neat, but I had some questions. Isn’t it pretty reckless to shoot an arrow into the air? How can you say that it fell to earth if it was to be found long afterward (if this repeated word comes soon after “follow,” could he have been playing with his own name?) in a tree? Isn’t the third line of the first stanza misleading, and was the coming rime worth the confusion? Would it not be hearing rather than sight that would attempt, unsuccessfully perhaps, to follow the song chat that was to fall to earth? Isn’t it kind of amateurish or ungrammatical to say “unbroke” instead of “unbroken”? Wouldn’t the latter improve the poem, you know, breaking the tedium? The penultimate line – is its hobbling supposed to prepare us for the extra steps of the last line? Well, I guess this poem is a nice lesson in mythmaking or at least metaphor. I mean, it’s good for Longfellow’s reputation that it was not an arrow found in the heart of a friend. (“Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Arrow and the Song”)

Lately I’ve been going through Vancouver writer, editor, poet and critic George Bowering’s Good Morning Poems: A start to the day from famous English-language poets (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2023), a short critical anthology of forty-eight poems selected across five hundred years of English-language poetry, each of which include a page-long commentary by Bowering himself. In his short preface to the collection, he offers that he likes to begin each morning reading (or rereading) a poem. “Some people like to go for a walk in the woods or to the coffee shop in the morning. Some peoples have even written poems about morning walks.” he writes. “I’m not that extreme – I’ll settle for a chair at the table, a cup of dark coffee, and a page or two of Denise Levertov. Lots of poets have written to or about the early hours, which suggests that if you are working on the New York Times crossword and thus have a pen in your hand, it might be as pleasant to write a poem as to read one. I’d just as soon read a poem, though, say ‘January Morning’ by William Carlos Williams, any month of the year.”

Lately I’ve been going through Vancouver writer, editor, poet and critic George Bowering’s Good Morning Poems: A start to the day from famous English-language poets (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2023), a short critical anthology of forty-eight poems selected across five hundred years of English-language poetry, each of which include a page-long commentary by Bowering himself. In his short preface to the collection, he offers that he likes to begin each morning reading (or rereading) a poem. “Some people like to go for a walk in the woods or to the coffee shop in the morning. Some peoples have even written poems about morning walks.” he writes. “I’m not that extreme – I’ll settle for a chair at the table, a cup of dark coffee, and a page or two of Denise Levertov. Lots of poets have written to or about the early hours, which suggests that if you are working on the New York Times crossword and thus have a pen in your hand, it might be as pleasant to write a poem as to read one. I’d just as soon read a poem, though, say ‘January Morning’ by William Carlos Williams, any month of the year.” The selection includes forty-eight poems alongside Bowering’s commentary, offering his insight on a range of published works by Sir Thomas Wyatt, Queen Elizabeth I, John Donne and Ben Jonson to Alexander Pope, William Wordsworth, Leigh Hunt and John Keats, to Emily Brontë, Archibald Lampman, Gertrude Stein and Margaret Avison. As he offers on Archibald Lampman: “Some professors who should have known better dubbed him ‘The Canadian Keats.’ Yes, he was one of those who could not resist riming ‘life’ with ‘strife,’ but even with the challenging rime scheme he forced upon himself, he wrote in ‘We Too Shall Sleep’ an affective poem about his unfortunate son without harming the language overmuch.” Five hundred years is an enormous stretch of English-language literature, so the selection is curious, from the expected to the unexpected, offering a variety of poetic structures as well as a range of poems famous to lesser-known.

There has always been a liveliness to Bowering’s prose, especially appreciated across his numerous collections of criticism, and this book provides a glimpse into his teaching methods, managing not only to articulate a vibrant commentary upon older poems, providing commentary and context, but to pass along his own obvious enthusiasm and sheer reading pleasure on works that most of us have either ignored or simply not been exposed to. If a book such as this was presented to high school students when attempting to teach poetry, we might all be in a far better situation as far as poetry reading literacy. Bowering’s enthusiasm is infectious, and he manages to pack a great deal of information and nuance, offering not only a context but some of the limitations of both poem and perspective, in his commentaries with incredible, readable ease. As he ends his commentary on Edgar Allan Poe’s “Sonnet – To Science”: “A lot of people think of Poe as the author of horror stories and fanciful verse. They ought to read this sonnet aloud, its rhythm and sounds so moving, the near perfection of its last three lines. Sonnets were invented as love poems; Poe the critic never forgets that.” Or, as he offers on Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing”:

At first you might wonder whether Whitman means that he is hearing workers in the United States or workers in all of America from Tierra del Fuego to Baffin Island. I think it’s possible that he means both – the nineteenth-century Whitman followed the eighteenth-century Thomas Jefferson in looking forward to a time when his country will have gobbled up the whole hemisphere. Such gobbling was called Manifest Destiny by some, Lebensraum by some others. Whitman’s notion of song accompanying work is pretty common. Whistle while you work, sang Jiminy Cricket, remember? He was a fictional character in the movies, as were all those melodious slaves “singing on the steamboat deck,” and in the hot cotton fields, all among the stones they piled to build the White House. The slaves who had a lot to do with building Whitman’s country did not own anything, not even themselves, and so were not referred to in the ninth line, “Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else.” Whitman the patriot liked the idea of a country made of individual states, a nation made of individual workers, and so on. His favourite poetic form was the list, as found in the Bible, a volume made up of individual books. The Ten Commandments, the begats, the Sermon on the Mount are some influential lists. Whitman in his poem lists various individuals singing, to be echoed, you might say, in his famous poem “Song of Myself.” You may sometime hear someone reading “I Hear America Singing,” but I wonder whether you have tried singing it.

March 1, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nancy Stohlman

Nancy Stohlman is the author of six books including

After the Rapture

(2023), Madam Velvet’s Cabaret of Oddities (2018), The Vixen Scream and Other Bible Stories (2014), The Monster Opera (2013), Searching for Suzi: a flash novel (2009), and Going Short: An Invitation to Flash Fiction (2020), winner of the 2021 Reader Views Gold Award and re-released in 2022 as an audiobook. Her work has been anthologized widely, appearing in the Norton anthology New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction and The Best Small Fictions 2019, as well as adapted for both stage and screen. She teaches at the University of Colorado Boulder and holds workshops and retreats around the world. Find out more at http://www.nancystohlman.com

Nancy Stohlman is the author of six books including

After the Rapture

(2023), Madam Velvet’s Cabaret of Oddities (2018), The Vixen Scream and Other Bible Stories (2014), The Monster Opera (2013), Searching for Suzi: a flash novel (2009), and Going Short: An Invitation to Flash Fiction (2020), winner of the 2021 Reader Views Gold Award and re-released in 2022 as an audiobook. Her work has been anthologized widely, appearing in the Norton anthology New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction and The Best Small Fictions 2019, as well as adapted for both stage and screen. She teaches at the University of Colorado Boulder and holds workshops and retreats around the world. Find out more at http://www.nancystohlman.com 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The first book is like the first wedding–everyone comes! Everyone is so happy for you. You get to open up that first box of books, hold it in your hand. Smell the ink! See your name on that cover! Have a book release event! Change your bio to say things like: I published a book. It’s crazy and amazing. For me this was 2009.

Fast forward almost 15 years, and After the Rapture is almost nothing like that first book in content or process. My first book was realistic, fictional but plausible. Every book I’ve since then has gotten weirder and more absurd, which is I suppose a good reflection of where I am these days. And, not only does the work itself feel more mature, but my identity as a writer just feels natural, an inherent part of who I am. Before we have published a book we have all these fantasies about how our lives will change…which they do…but also they don’t. Published or not, we still have to get back to work.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I don’t think it was a choice. I’ve always been a storyteller, so I was always leaning towards narrative. And I’ve always been in love with novels, so writing novels was the natural first thing for me. I’ve dabbled quite a bit in journalism, and I appreciate the writing of reality, but for me, the fun of being a writer is the license to distort reality and make interesting shapes where there were no shapes before.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

No notes. It happens like a relationship–slow and flirty at first, then hot and heavy. Then maybe after the initial burst it stalls out…and the project and I are forced to sit down and have a heart-to-heart: what are we doing here? Are we a couple or what? Then we figure it out, I have some sort of crucial epiphany about the work that changes everything, and then I finally know what I’m doing.

Followed by…a second draft of that process. And a third. Most of my books take me about 4 years to complete from beginning to end. My best advice to others (and myself!) is to remember that you are never in charge of the story. The story is always in charge–you’re just there to write it all down.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Actually, both. I’m a huge fan of flash fiction, and I’ve been working and playing in the house of flash fiction for years. But, as I’m mentioned, I’m also a big fan of the novel, the sweeping story that you can’t finish in one setting. So this intersection has become my sweet spot: playing and writing at the crossroads between flash fiction and the novel. I’m basically always writing a large-scale idea made from pieces, like a puzzle or a mosaic, and After the Rapture is the perfect example of that kind of play.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love public readings! I even love Zoom readings. Reading your work and writing that work are really two completely different things, but when you can do them both well, it’s magic. I’m very lucky to have a performance background, both as an actress and a singer, so I’m very comfortable on the stage, and I think it’s a skill and a gift when someone is also able to bring their words to life in a reading. Ten years ago I started the Fbomb Flash Fiction Reading Series (www.fbombdenver.com), which was the first and now longest-running flash fiction reading series in the country, and one of my main objectives, besides spreading the gospel of flash fiction, was to foster a space where we could all become better readers.

Speaking of reading, I also did the audio narration for Going Short: An Invitation to Flash Fiction last year, and I had to tap into all my stage and musical training in the studio during an epic one-day recording. Yeah. My face hurt for a week, but it was an incredible experience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Hmmm…I think the theoretical concerns bloom from my observations of and the way I engage with the world. I don’t sit down and think: I have a theoretical concern I would like to express through a story…and then try to craft a story to hold the container of that concern. For me, that would be a disaster. No. Instead, I lean into what’s interesting to me, knowing our bodies and brains are a kind of theoretical sieve and social commentary is likely to bleed into the text. We are all political creatures, whether we want to admit it or not, and when I arrive at my final result in this organic way, I am often as surprised as the reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think the writer’s job is to hold a vision, and to create frames for others to see that vision. We hold up the frame and say: Look at that. Isn’t that amazing? (tragic, gorgeous, etc.) Which of course means that we need to always practice our own seeing, perpetually honing and polishing our own lenses of wonder and delight.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Ah…it all depends on the editor! I’ve been on the other side as the editor much more often than I’ve been on the receiving end, so when I do find myself on the receiving end, I am very empathetic and attuned to the delicate relationship that must transpire if editor and writer are going to do their dance in a profound way. On the receiving end, it’s so important to be in the right frame of mind, receiving it from someone you trust or who at least understands what you are trying to do with your work (as opposed to what they would do if it was theirs). Not all criticism is equal or even valid. But sometimes it’s crucial.

I try to pay attention to two reactions: the instant yes and the instant no. Both of those tend to hold heat for me. I work with a lot of writers who think critique should be painful, who let me know they can ”handle it” and then brace themselves like a linebacker. I think critique can be soft and inspirational and enlivening. It can be like your best friend telling you an important truth. It can be like a brainstorm that leaves you excited and ready to play. So I attempt to put critique, both the giving and receiving, in that frame of mind. And when it’s not, I recommend banana splits.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

As a young writer I was very inspired by Stephen King’s attitude towards writing as a job, one with good days and bad days. Your job is to show up to work, regardless. That attitude helped me take a little bit of the preciousness out of the writerly identity. Because yes, a whole lot of magic has to happen between concept and artifact…but it doesn’t happen at all if we are in some sort of “waiting for the muse” holding pattern. James Clear says in his book Atomic Habits that the difference between an amateur and a professional is that the amateur only shows up when it’s fun, and the professional shows up regardless. I also love this quote by W. Somerset Maugham — '”I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o'clock sharp.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (flash fiction to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

For me, extremely easy. I love both so much that crossing the streams was just an organic process for me. Any big story is made up of a million tiny stories–a life is made up of millions of tiny moments. In many ways it feels like a more accurate and natural way to approach a longer story, and it’s a method I teach (and love).

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every morning in bed while drinking coffee. Pretty much every day for 25 years. This happens in a journal, by hand, and it is messy and sloppy. And wonderful. It’s the way I plug my antenna into the universal goo each morning and say, ”Put me in coach, I’m ready to engage.” If I miss a morning due to travel or something I feel off all day.

The editing part, or more specifically the part that happens at a computer, comes later in the afternoons when my brain is sharper and more discerning, as opposed to the dreaminess of morning.

By the time the sun goes down I’m usually ready to read, listen to music, watch movies and disengage with the work until the next morning.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I absolutely love rereading and recommend it often, especially in those stalling moments. I know writers who lament that they don’t have enough years to finish all the books on their lists, let alone rereading! I get it. But there is a special magic that happens in the rereading process. The beauty of rereading is there is no risk–you aren’t trying to figure out the plot, you aren’t even trying to decide if you like the book or not. With all that out of the way, rereading becomes a comfortable reunion with an old friend, words and stories that have moved you (at least once) already. You don’t have to pay such close attention–you can just enjoy the scenery a little more and watch how the whole mechanism gets put together.

Also getting outside of my head and off the page does wonders for my creativity. A solo trip to the museum or the symphony (yes, try it solo!) does wonders for me. I also love taking myself on a weekend retreat to a simple hotel–a kind of marriage encounter between me and the work where we dive in deeply and re-emerge refreshed. It works every time.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Oh yes. All of them! I feel so lucky to be a creative individual in this life, because honestly everything is inspiration. Movies, especially the quiet foreign ones, the black and white ones, the dramas and the satires. Fashion, both wearing and contemplating it. Museums of all sorts. Classical music. Jazz. Smoky lights. Really beautiful food. Walking around the lake behind my house almost every day and becoming in tune with the miniscule changes of day-to-day nature. Photographs, both as the subject and the photographer. Travel in all forms. A good road trip, especially across the Zen flatness of the Midwest. I love to purposely wake up before sunrise and drive myself into the sunrise with coffee and Tom Waits’ Closing Time. Cathedrals and stained glass and carnivals and neon lights, and I get a lot of inspiration from Wikipedia, believe it or not.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Ride in a hot air balloon. Float down the Nile. Live by the ocean. Be an ex-pat. Watch my book be made into a movie.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

As I said I went to undergrad for theater; I was planning to end up in NYC or Hollywood and become an actress, stage or screen. But at one point in the hustle I realize if you are going to hustle THAT much, and do all that work to twist yourself into a product …then you better be REALLY sure. I realized I wasn’t excited enough about the process, I just liked being on stage. So…I ran off and joined the circus instead! And that’s when I started writing seriously. But I can’t tell you how often my theater training comes up, even now. Here are a few examples of how I have crossed acting with writing:

Going Short Book Trailer https://youtu.be/lxrMMX81YXg

Madam Velvet Book Trailer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZdOGFsjBlE&t=19s

The Monster Opera Book Trailer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWxln66wxeg&t=4s

17 - What are you currently working on?

I’ve been working on a new project for about a year—it was initially inspired on one of those long, Zen drive across Kansas last year to visit a friend, and it has since blossomed into a set of fictitious Tarot-like cards telling a sort of Midwestern Gothic story. I’m in the fun part—still discovering , still turning over rocks to see what lives underneath. So far there are lots of elements of mythology and familiar mythological tropes meets Corn, Tornadoes, Guns, Flags and Jesus—etc. I love it, and I can’t wait to see it come into its own maturity. I’m just really sitting back and writing down what it wants to say. It’s like I’m writing the instruction manual for a game that doesn’t exist.

I’m also getting ready to run three flash fiction writing retreats in 2023—in France, Iceland, and Colorado. My two favorite things: writing and travel both together!

It's been so much fun chatting with you, thanks for having me!

Buy After the Rapture from Mason Jar Press https://masonjarpress.com/chapbooks-1/after-the-rapture

Retreats website www.flashfictionretreats.com

February 28, 2023

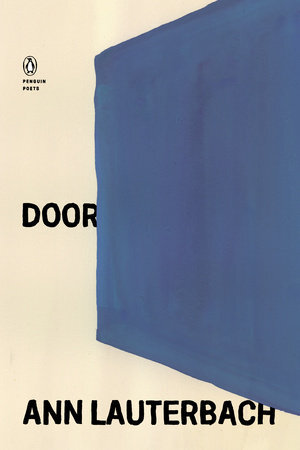

Ann Lauterbach, Door

TALLY

And then the dream was assessed

across a black-and-gold screen. It warned

not to look out a the veiled air, not

to recall the room

where she slept as a bear

came down the long dark hall.

This occurred in the retelling,

under the present image:

a smiling woman clutching her scarf

in front of blue mountains

and scant drifting clouds. It seemed

something had happened to give her joy.

In the dream, she was neither pardoned

nor included, trudging along the path,

dragging the pelt, as the young Icelandic man

pounded away at the partita, his fingers

routing the keys, hair agitated in wind.

As she reached the crest of the hill

she lay down on the stone cap

and began to hum, to tally the day

into the vertigo of the night’s cold vengeance.

The latest from American poet and essayist Ann Lauterbach, following ten previous collections of poetry and three books of essays, is the poetry collection Door(Penguin, 2023). Hers is a name I’ve heard for some time, although this is the first collection I’ve seen. There is something of the clarity and the tone across these poems that echoe, slightly, that of the work of American poet Caroline Knox, although each poet works with an entirely different kind of sharpness across their narrative lyrics. “So blind to consequence,” Lauterbach writes, as part of the poem “SYNTAX,” “wondering / what the difference is between care and trust.” Lauterbach writes syntax, gardens, dunes, apparitions, horizons and ethos, all through the framing of that particular image of the door, and there are ways through which her narratives float into the surreal, simultaneously anchored and seemingly-untethered, riding a fine line of possibility amid a shifting of perception. “The long rain of men keeps raining.” she offers, as part of “THE MINES (MAGRITTE),” “Have they looked down? Have you?” A few lines further on, writing:

The north wind, you were saying;

blisters on your heels? You

ran too far in the moonlight

under the sign of Magritte

and the petty grievances of small

river towns. The trees blacken,

high hills ram a backlit sky, bottles

fill with cloud, the same clouds

the big bird sets alight, the big eye

comes. […]

She seems to compose across a sequence of precisions across a wide landscape of narrative, allowing for a further subtlety, one might say, for not structurally highlighting phrases that other, lesser poets might have brought further into the light. Perhaps even to highlight a line out of context for the purposes of this review is to potentially reduce their remarkable power. And yet, how to provide without quoting whole poems? “Good we have eternal / so the gigabyte and its multiplication // can endure,” she writes, as part of the title sequence, “the motherboard / go dim without consequence.” Her lines are stronger for sitting as they lay, within those structures. Through forty-four first person lyric narratives, she writes through and around the image and suggestion of a door. As a further part of her eleven-part title sequence, she offers “Is Door a wound?” and it reminds of British Columbia poet Fred Wah’s own is a door(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2009) [see my review of such here], both of which echo, perhaps, a particular translation of Rumi, that reads: “A wound is a door through which the light comes in.” Indeed.

She seems to compose across a sequence of precisions across a wide landscape of narrative, allowing for a further subtlety, one might say, for not structurally highlighting phrases that other, lesser poets might have brought further into the light. Perhaps even to highlight a line out of context for the purposes of this review is to potentially reduce their remarkable power. And yet, how to provide without quoting whole poems? “Good we have eternal / so the gigabyte and its multiplication // can endure,” she writes, as part of the title sequence, “the motherboard / go dim without consequence.” Her lines are stronger for sitting as they lay, within those structures. Through forty-four first person lyric narratives, she writes through and around the image and suggestion of a door. As a further part of her eleven-part title sequence, she offers “Is Door a wound?” and it reminds of British Columbia poet Fred Wah’s own is a door(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2009) [see my review of such here], both of which echo, perhaps, a particular translation of Rumi, that reads: “A wound is a door through which the light comes in.” Indeed.

February 27, 2023

VERSeFest (Ottawa) 2023 : Volunteer Appreciation Night, March 4, 2023! w readings by Latour, Dumont, Andrews + Roach,

VERSeFest, Ottawa’s glorious poetry festival returns!

VERSeFest, Ottawa’s glorious poetry festival returns! Join us Saturday, March 4, 2023 (6:30 door/7pm reading) at Cooper's Creative Kitchen, Embassy Hotel & Suites, 25 Cartier Street, Ottawa, for an evening of poetry and drinks on us! (Yeah, we said drinks). Every year, VERSeFest is a huge success because of the tireless work and effort of our amazing volunteers. We couldn’t do it without you. This is our way of giving back and saying thanks for all that you do, you incredible beings you!

lovingly hosted by rob mclennan

With readings by:

current Ottawa poets laureate Gilles Latour and Albert Dumont

and poets Kimberly Quiogue Andrews and Leslie Roach

Now thirteen years old, our 2023 festival runs from March 18 to 26!

(details to appear on the website soon)

Win PRIZES! Books, tickets, and more…

Why volunteer for VERSeFest? Not only will you get to attend the planet’s most exciting poetry festival FREE on nights you volunteer, but you also get to meet your favourite writers, work with a fun crew, and attend awesome events like this one. Oh, and if you volunteer at more than one event, you get a free pass to the ENTIRE festival. Sweet, right?

We're looking for people who are willing to help out during the reading, tend bar, (wo)man the door and merch table, etc.

Bring your friends! Bring your flatmates! Bring your loved ones!

Author biographies:

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews

is a poet and literary critic. She is the author of A Brief History of Fruit, winner of the Akron Prize for Poetry from the University of Akron Press, and BETWEEN, winner of the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Prize from Finishing Line Press. She teaches creative writing and American literature at the University of Ottawa.

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews

is a poet and literary critic. She is the author of A Brief History of Fruit, winner of the Akron Prize for Poetry from the University of Akron Press, and BETWEEN, winner of the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Prize from Finishing Line Press. She teaches creative writing and American literature at the University of Ottawa.

Albert Dumont,Algonquin, Kitigan Zibi: Presently Albert is Ottawa's English Poet Laureate. He is an activist, spiritual advisor, volunteer and a poet who has published 6 books of poetry and short stories and 2 children’s books. Initiated poetry contest 'I am a Human Being' as English Poet Laureate for Ottawa in 2022, resulting in an anthology of the poems submitted. Albert has dedicated his life to promoting Indigenous spirituality and healing and to protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Albert Dumont,Algonquin, Kitigan Zibi: Presently Albert is Ottawa's English Poet Laureate. He is an activist, spiritual advisor, volunteer and a poet who has published 6 books of poetry and short stories and 2 children’s books. Initiated poetry contest 'I am a Human Being' as English Poet Laureate for Ottawa in 2022, resulting in an anthology of the poems submitted. Albert has dedicated his life to promoting Indigenous spirituality and healing and to protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Gilles Latour

, poète franco-ontarien né à Cornwall (Ontario) a grandi à Ottawa, à Montréal et à Paris, a étudié la littérature et la linguistique à l'Université de Montréal et à l’Université McGill, et a travaillé pour des organisations humanitaires et de développement international en Afrique, en Asie et en Amérique Latine. Il a aussi travaillé dans l’enseignement, comme expert conseil en développement international, et comme traducteur et rédacteur technique. Et aussi, brièvement, comme opérateur technique dans une raffinerie, comme plongeur dans un café, et comme chauffeur de taxi. Il vit à Ottawa depuis plus de quarante ans et a dirigé la collection Fugues/Paroles (poésie) aux Éditions L'Interligne (Ottawa) pendant quelques années. Après avoir publié des poèmes dans quelques revues québécoises pendant les années 70, 80 et 90, dont Éther et Trois, il a publié Maya partir ou Amputer aux Éditions L'Interligne en 2011, Mon univers est un lapsus(L’Interligne, 2014), Mots qu’elle a faits terre (L’interligne, 2015, finaliste au Prix Trillium de poésie, au Prix de la Ville d’Ottawa et au Prix Le Droit), de même que À la merci de l’étoile (L’Interligne, 2018, finaliste au Prix Trillium), et Débris du sillage (L’Interligne, 2020), finaliste su Prix de la Ville d’Ottawa et Feux du naufrage (L’Interligne, 2022). Ses poèmes ont également paru dans plusieurs recueils collectifs dont, entre autres : Poèmes de la Cité(David, 2020), Poèmes de la résisance (Prise de parole, 2019), et Cohues (Paris, 2014). Il est actuellemet Poète lauréat francophone de la Ville d’Ottawa (2021-2023).

Gilles Latour

, poète franco-ontarien né à Cornwall (Ontario) a grandi à Ottawa, à Montréal et à Paris, a étudié la littérature et la linguistique à l'Université de Montréal et à l’Université McGill, et a travaillé pour des organisations humanitaires et de développement international en Afrique, en Asie et en Amérique Latine. Il a aussi travaillé dans l’enseignement, comme expert conseil en développement international, et comme traducteur et rédacteur technique. Et aussi, brièvement, comme opérateur technique dans une raffinerie, comme plongeur dans un café, et comme chauffeur de taxi. Il vit à Ottawa depuis plus de quarante ans et a dirigé la collection Fugues/Paroles (poésie) aux Éditions L'Interligne (Ottawa) pendant quelques années. Après avoir publié des poèmes dans quelques revues québécoises pendant les années 70, 80 et 90, dont Éther et Trois, il a publié Maya partir ou Amputer aux Éditions L'Interligne en 2011, Mon univers est un lapsus(L’Interligne, 2014), Mots qu’elle a faits terre (L’interligne, 2015, finaliste au Prix Trillium de poésie, au Prix de la Ville d’Ottawa et au Prix Le Droit), de même que À la merci de l’étoile (L’Interligne, 2018, finaliste au Prix Trillium), et Débris du sillage (L’Interligne, 2020), finaliste su Prix de la Ville d’Ottawa et Feux du naufrage (L’Interligne, 2022). Ses poèmes ont également paru dans plusieurs recueils collectifs dont, entre autres : Poèmes de la Cité(David, 2020), Poèmes de la résisance (Prise de parole, 2019), et Cohues (Paris, 2014). Il est actuellemet Poète lauréat francophone de la Ville d’Ottawa (2021-2023). Franco-Ontarian poet Gilles Latourwas born in Cornwall (Ontario), grew up in Ottawa, Montreal and Paris, and studied literature and linguistics at the Université de Montréal and at McGill University. He has spent most of his working life with humanitarian and international development organizations in Africa, Asia and Latin America, but he has also worked as a teacher, a consultant in humanitarian affairs, a technical translator and writer and, briefly, as an oil refinery operator, a café dishwasher and a taxi driver. He has lived in Ottawa for four decades, where he was poetry editor for Les Éditions L’Interligne for a few years. During the 70s, 80s and 90s his poems appeared in Quebec Literary journals such as Revue Éther and Revue Trois. His first collection, Maya partir ou Amputer, was published by Les Éditions L'Interligne in 2011, followed by Mon univers est un lapsus in 2014, Mots qu’elle a faits terre in 2015 (nominated for the Trillium Poetry Prize, the City of Ottawa Book Award and the Prix Le Droit), as well as À la merci de l’étoile in 2018 (finalist for the Trillium Prize) and, most recently, Débris du sillage in 2020 (finalist for the Ottawa Book Award), and Feux du naufrage in 2022, all published by Les Éditions L’Interligne. His poems have also appeared in several collective publications and anthologies, most notably in : Poèmes de la Cité (Éditions David, 2020), Poèmes de la résisance (Éditions Prise de parole, 2019), and Cohues (Éditions Cohues, Paris, 2014). He is currently Ottawa’s Francophone Poet Laureate (2021-2023).

Leslie Roach

is an Ottawa-based poet and writer. Born and raised in Montreal to thoughtful and loving parents who immigrated to Canada from Barbados, Leslie has lived and worked in Italy, Mali, Tanzania, Kenya and Senegal, shaping her perspectives and worldview. She then moved to Ottawa, working for the International and Interparliamentary Affairs directorate of the Parliament of Canada, the Supreme Court of Canada and the National Gallery of Canada.

Leslie Roach

is an Ottawa-based poet and writer. Born and raised in Montreal to thoughtful and loving parents who immigrated to Canada from Barbados, Leslie has lived and worked in Italy, Mali, Tanzania, Kenya and Senegal, shaping her perspectives and worldview. She then moved to Ottawa, working for the International and Interparliamentary Affairs directorate of the Parliament of Canada, the Supreme Court of Canada and the National Gallery of Canada. As a lawyer, she previously worked for the United Nations for 10 years in law and HR, specializing in conduct and discipline related to sexual, physical and psychological abuse.

She started writing and journaling at a young age as a form of therapy to process the racist experiences she had growing up.

In 2020, she released her debut book Finish this Sentence, a collection of poetry about healing from the effects of racism, finding one’s voice and power, and claiming your human right to be happy. She has been featured on major media platforms, including CBC and CBC Books, and has partnered with national brands like DeSerres.

Today, she is an advocate for finding your power through practicing mindfulness, both at work and at home, as a way to respond effectively to situations. She is also a workshop facilitator on journaling and mindfulness at work, and journaling to find one’s true calling and purpose.

February 26, 2023

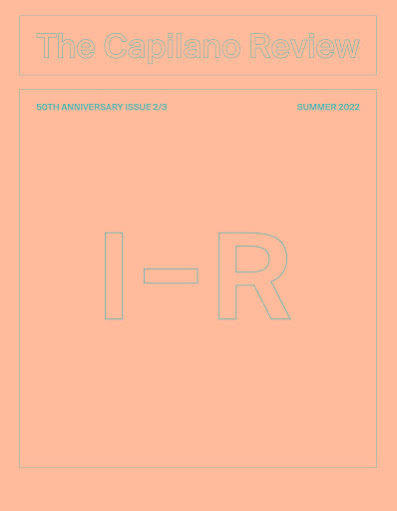

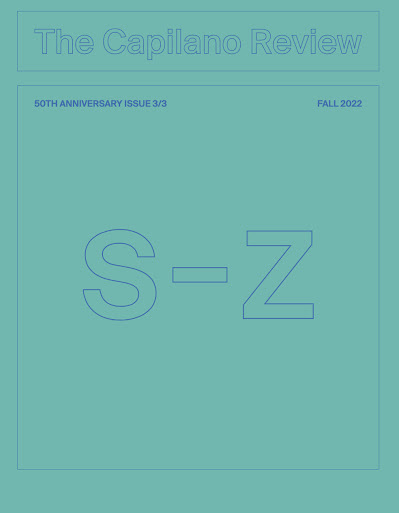

The Capilano Review : 50th Anniversary Issue(s) : 3:46-3:48

Last year, in anticipation of our 50th anniversary, we invited over a hundred of the magazine’s contributors to submit a term of their choosing to our special anniversary issues, the first of which you now hold in your hands. These terms would be collecting, we said, alongside notable selections from our archive into an experimental glossary—a form we hoped would index the creative practices that make up our literary and arts community while elucidating, as our invitation explained, “some of the questions, shifts, antagonisms, and continuities that have marked five decades of publishing.” Returning to our prompt now, I can’t help but also consider the term “experimental,” itself a point of ongoing discussion at the magazine and one that has generated lively debate: What are our criteria for “experimental” writing? What does it look like on the page, and how does it sound? Who does it include? What kinds of risks does it take, and how does it take them? (Matea Kulić, “Editor’s Note,” 3.46, Spring 2022)

Anniversaries, much like birthdays, are a good time to assess, reassess, examine and celebrate, and Vancouver’s The Capilano Review did just that last year, offering all three 2022 issues as a single, ongoing 50th anniversary celebratory project. Across a period that also included the shift from Matea Kulić to Deanna Fong as the journal’s main editor [see then-editor Jenny Penberthy's 2010 "12 or 20 (small press) questions" interview on the journal here], the three issues were released as “A – H” (Spring 2022; 3.46), “I – R” (Summer 2022; 3.47) and “S – Z” (Fall 2022; 3.48), producing a self-described triptych “featuring newly commissioned work alongside notable selections from our archive by over a hundred of the magazine’s past contributors.” The range and the ambition of this year-long project is stunning, providing an overview of contributions in a loosely-thematic alphabetical order that offers a vibrancy across each page. If you haven’t yet, or haven’t much, interacted with the journal, this might be the place to begin: the three volumes offer a combined four hundred and fifty-some pages’ worth of essays, poems, stories, visual art, statements, interviews and other works in a wild incredible wealth of material (and contributors too many to list across this particular space) that ripple from the journal’s core of Vancouver out across Canada and well into the international.

Anniversaries, much like birthdays, are a good time to assess, reassess, examine and celebrate, and Vancouver’s The Capilano Review did just that last year, offering all three 2022 issues as a single, ongoing 50th anniversary celebratory project. Across a period that also included the shift from Matea Kulić to Deanna Fong as the journal’s main editor [see then-editor Jenny Penberthy's 2010 "12 or 20 (small press) questions" interview on the journal here], the three issues were released as “A – H” (Spring 2022; 3.46), “I – R” (Summer 2022; 3.47) and “S – Z” (Fall 2022; 3.48), producing a self-described triptych “featuring newly commissioned work alongside notable selections from our archive by over a hundred of the magazine’s past contributors.” The range and the ambition of this year-long project is stunning, providing an overview of contributions in a loosely-thematic alphabetical order that offers a vibrancy across each page. If you haven’t yet, or haven’t much, interacted with the journal, this might be the place to begin: the three volumes offer a combined four hundred and fifty-some pages’ worth of essays, poems, stories, visual art, statements, interviews and other works in a wild incredible wealth of material (and contributors too many to list across this particular space) that ripple from the journal’s core of Vancouver out across Canada and well into the international. Introducing a special double issue (Nos. 8 & 9, Fall 1975/Spring 1976) to memorialize the loss of Bob Johnson, “the man responsible for the original graphic design of The Capilano Review,” then-editor and founder Pierre Coupey wrote: “When we first proposed a magazine at Capilano, I wanted one that would not only print good work, but also one whose design would treat that work with respect.” I would say that such a consideration has remained, thanks to the solid foundations that Coupey and Johnson (among others) originally set up, way back in 1973 over at Vancouver’s Capilano College (the journal and since-university have since parted ways).

The problem with defining yourself by the centre is that you are working backwards. That which is earlier is supposed to be better. Because it was before the erasure, its reinscription is sacrosanct. This is a handy cudgel for authoritarians. Look to the Duvaliers in Haiti for Afrocentrism as policy, where it served to quiet social criticism, where it was at first used to smash the Left, and later to smash democracy altogether. Let them eat Egyptology.

Fanon excorcised all this in “On National Culture,” espousing an anti-colonialism that is a pragmatic synthesis of old and new in the form of a “fighting phase” of the culture. Returning to previous tradiations is no panacea. The modernity of Fanon’s position leaves room for social change and challenges to old thinking—in other words, Fanon’s position makes space for innovations that Fanon could not himself yet imagine. Ideas are not good just because they’re African. They are good if they lead to liberation.

And liberation always needs the future. (Wayde Compton, “Afrocentripetalism & Afroperipheralism,” 3.46)

Even beyond considering the amount of other presses and journals that appear to be falling by the wayside lately (

Catapult

, Bear Creek Gazette, Ambit), it is important to acknowledge those journals (and presses) that are not only still around, but managing to consistently publish an array of stunning work, let alone for fifty years and counting [see my review of their 40th anniversary issue here]. And The Capilano Review isn’t the only one to celebrate, as

Arc Poetry Magazine

(b. 1978) will soon be releasing their special 100th issue, Derek Beaulieu recently produced an anthology celebrating twenty-five years of publishing through his combined housepress/№ Press, and even my own above/ground press (b. 1993) is working on some exciting project for this year’s thirtieth anniversary, including a third ‘best of’ anthology out this fall with Invisible Publishing (and don’t forget the pieces posted five years ago for above/ground press’ twenty-fifth, or even the array of pieces published not long after, to celebrate forty years of Stuart Ross’ Proper Tales Press). I wonder what Brick Books, as well, might attempt in two years’ time for their fiftieth?

Even beyond considering the amount of other presses and journals that appear to be falling by the wayside lately (

Catapult

, Bear Creek Gazette, Ambit), it is important to acknowledge those journals (and presses) that are not only still around, but managing to consistently publish an array of stunning work, let alone for fifty years and counting [see my review of their 40th anniversary issue here]. And The Capilano Review isn’t the only one to celebrate, as

Arc Poetry Magazine

(b. 1978) will soon be releasing their special 100th issue, Derek Beaulieu recently produced an anthology celebrating twenty-five years of publishing through his combined housepress/№ Press, and even my own above/ground press (b. 1993) is working on some exciting project for this year’s thirtieth anniversary, including a third ‘best of’ anthology out this fall with Invisible Publishing (and don’t forget the pieces posted five years ago for above/ground press’ twenty-fifth, or even the array of pieces published not long after, to celebrate forty years of Stuart Ross’ Proper Tales Press). I wonder what Brick Books, as well, might attempt in two years’ time for their fiftieth?

I haven’t seen a copy of the debut issue of The Capilano Review (despite my best efforts over the years), but as part of the “20th Anniversary Issue” (Series 2:10, March 1993), then-editor Robert Sherrin offered both a sense of quiet humility and forward thinking in his preface that seems the lifeblood of the journal’s ongoing aesthetic: “It is traditional at such a time to present a retrospective issue, but on this occasion the editors of TCRdecided that while it is appropriate the acknowledge those who have contributed significantly to our culture, it is equally important to present those who will extend, transform, and renew our culture. The present issue is our attempt to acknowledge the past and to welcome the future.” Too often, it seems, journals begin with such good and even radical intentions, and become tame as the years continue, some to the point of self-parody, something The Capilano Review has managed to avoid, remaining as vibrant, or perhaps even moreso, than it has ever been. Consistently working beyond the bounds of the straightforward literary journal, The Capilano Review has always seemed a space for a particular assemblage of shared aesthetic approach and rough geography, occasionally branching out into features on and by works by predominantly west coast writers and artists. Whether produced as combined or full-issues, some of these over the years have included features on George Bowering, Daphne Marlatt, Michael Ondaatje, Brian Fawcett, David Phillips, Barry McKinnon, Gathie Falk, Robin Blaser, Roy K. Kiyooka, Gerry Shikatani and Bill Schermbrucker, among numerous others, as well as a sound poetry issue, “With Record Included,” guest-edited by Steven [Ross] Smith and Richard Truhlar.

I haven’t seen a copy of the debut issue of The Capilano Review (despite my best efforts over the years), but as part of the “20th Anniversary Issue” (Series 2:10, March 1993), then-editor Robert Sherrin offered both a sense of quiet humility and forward thinking in his preface that seems the lifeblood of the journal’s ongoing aesthetic: “It is traditional at such a time to present a retrospective issue, but on this occasion the editors of TCRdecided that while it is appropriate the acknowledge those who have contributed significantly to our culture, it is equally important to present those who will extend, transform, and renew our culture. The present issue is our attempt to acknowledge the past and to welcome the future.” Too often, it seems, journals begin with such good and even radical intentions, and become tame as the years continue, some to the point of self-parody, something The Capilano Review has managed to avoid, remaining as vibrant, or perhaps even moreso, than it has ever been. Consistently working beyond the bounds of the straightforward literary journal, The Capilano Review has always seemed a space for a particular assemblage of shared aesthetic approach and rough geography, occasionally branching out into features on and by works by predominantly west coast writers and artists. Whether produced as combined or full-issues, some of these over the years have included features on George Bowering, Daphne Marlatt, Michael Ondaatje, Brian Fawcett, David Phillips, Barry McKinnon, Gathie Falk, Robin Blaser, Roy K. Kiyooka, Gerry Shikatani and Bill Schermbrucker, among numerous others, as well as a sound poetry issue, “With Record Included,” guest-edited by Steven [Ross] Smith and Richard Truhlar. The Capilano Review has always been unique in Canadian literature through offering, from the offset, an ethics of exploration, resistance and experiment; offering an aesthetic influenced by west coast social politics, critiques of colonialism, issues of race and environmental concerns, all of which have been shared with others in their immediate vicinity, including The Kootenay School of Writing, Writing, Raddle Moon and Line (and later, West Coast Line), and more recent journals such as Rob Manery’s SOME. And yet, unlike most of those examples, The Capilano Review is still publishing, still evolving, exploring and pushing, and seeking the possible out of what otherwise might have seemed impossible. Welcoming the future, indeed.

They will ask you what you ate. They will ask you where you walked, what you saw. The trees, for instance, so copious we assume they are free.

Take account, they will say. They will not ask who you are. Who you were. Were you queer. Did you matter.

Dear question mark you mark me.

It is a mix and match of images leading to a vanishing act. Expect the best is it evasion. It is a way of reversing fortunes.

I want to tell you the story of Lori because it is the opposite of nation-building. It is the opposite of canon.

She was in her room; it was just before midday in her life when the word opened.

How did she look. It was a hooked glance. it would not rhyme. It was another time.

Under the sun a hook of green eyes. No one wanted to be recognized. We all wanted to be seen.

Every day I do a now, and then it passes.

What is asking. An animation of statement. A transformation of intent.

I reach for my phone and vanish. (Sina Queyras, “DEAR QUESTION MARK,” 3.48)

February 25, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Su Cho

Su Cho is a poet and essayist born in South Korea and raised in Indiana. She has an MFA in Poetry from Indiana University and a PhD from University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She has served as the editor-in-chief of Indiana Review, Cream City Review and has served as guest editor for Poetry magazine. Her work has been featured in Poetry, New England Review, Gulf Coast, and Orion; the 2021 Best American Poetry and Best New Poets anthologies; and elsewhere. A finalist for the 2020 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Poetry Fellowship, recipient of a National Society of Arts and Letters Award, and a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, she is currently an assistant professor at Clemson University.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

In a way, the first book changed my life in the sense that it helped me come to terms with everything that I was processing. So now, I feel like my life can change, even though objectively, it has been changing this whole time.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Like a lot of people, I wanted to write songs, raps, and little love poems when I was younger. What I was really drawn to, I think, was the distillation of complex feelings and poetry could do that so quickly and intensely. Such a dramatic genre!

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It really depends. Some of the formal/narrative arcs in the book came together very quickly, in a matter of weeks or a few months. Some others took years. But they were all building toward one another and so I would characterize it as a very slow process, building these small poems into something larger.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I definitely lean more toward having a bundle of short pieces that build into something larger and more coherent. I find that I like to write poems along a feeling or journey. They’re like rest stops on an endless highway, and sometimes, it does feel like I don’t know when the next stop is coming.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I absolutely love readings (even though I still manage to get incredibly nervous beforehand). I find that it’s a very privileged space where I can talk out my ideas or see my poems in a different way, especially with the fortune of having different audience members. Sometimes during a reading, I’ll realize that I really hate one of my poems now but later I’ll rediscover my fondness for a poem. Readings are essential for that.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I always say that community building is worldbuilding, and the question I always ask is who is in this world of my poems and who do I want to invite?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writers exist to model a sense of curiosity and openness to anyone who will listen. Anyone who picks up a book wants to discover something, and writers are the ones waving people over.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s a blessing when poets can work with outside editors! Working with mine (Allie) was absolutely essential and I enjoyed every moment! I felt like I was too close to my book at that point so to have a different perspective was welcome and needed.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To get comfortable writing in your head.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think the appeal for me is the ease in which I can move between poetry and essays. It’s the matter of breadth each genre offers. If I find myself writing the same kind of poem again and again, I’ll switch to an essay trying to discover what it is that keeps pulling me to that subject matter.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I actually don’t have a writing routine. The one thing I’ve learned about myself is that I need lots of sleep and that I have seasons of writing energy. I used to feel a lot of shame and guilt around that, but I’ve come to terms with it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I always go back to writers like Galway Kinnell, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and Gabrielle Calvocoressi. I like to turn toward writers I wish I could write like but can’t.

February 24, 2023

Nathalie Khankan, quiet orient riot

said on these storied soils | I don’t spoil any seed | there is no pure race | a bride is still bridal | a checkpoint is STILL TORN HILL | in just a few weeks topographical categories shift & our bodies move toward a lid with a tighter seal | with the hill gone another concrete tower erupts & the militarized sanitized | it’s a border crossing running through continuous land | if i get married i will get stuck here & my wedding thōb against the bodies of busses jamming here | if i bear a child my engorged breasts here | the human count is a crucible

I’m just now going through San Francisco-based poet Nathalie Khankan’s quiet orient riot (Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), winner of the omnidawn 1st/2ndpoetry book prize, as judged by Dawn Lundy Martin. “Straddling Danish, Finnish, Syrian and Palestinian homes and heirlooms,” as her author biography describes her, Khankan’s book-length lyric is composed with a wonderfully-delicate urgency, pushing and agonizing across geopolitics and grief, and an attention to lyric flow that is both beautiful and devastating. “there’s no trace of saccharine in the teas of gaza,” she writes, “there is / nowhere safe to hide […]” As Dawn Lundy Martin offers as part of her introduction to the collection:

The search for “little justices” configures one narrative anchor across the book, and when they emerge—these little justices—they do so desperate and breathless as if all existence relies on them. this is because violence and loss permeate the landscape. We understand this from Khankan’s images of grief. They speak to the future of utterance amid chaos. “this is a picture of three men standing up coiling father | his hands empty & empty.” It’s altering to read a world where even the size of justice must be shrunken.

quiet orient riot

is composed through fifty-two individual prose lyrics, one to a page, and all seemingly each untitled, until one realizes (through the table of contents) that the titles sit within the body of each poem, almost as though each title sits as a fallen leaf, floating upon the surface of the poem’s small pool. She writes of, as Fady Joudah writes on the back cover, a “Palestinian book in Empire,” writing exile and anticipation, the West Bank and Gaza. In many ways, this is a quiet book that holds incredible power, resonance and urgency, writing out the possibilities of birth in a landscape rife with conflict, suffering and loss; writing out the possibilities of birth while holding to those cultures that surround, whether from outside or within; that particular geography, and the richnessess that live there, all intimately shared with her growing daughter. This book articulates, one might say, a growing hope amid ongoing realities of conflict. Hope, amid the possibility of something further. As she writes, close to the end of the collection:

quiet orient riot

is composed through fifty-two individual prose lyrics, one to a page, and all seemingly each untitled, until one realizes (through the table of contents) that the titles sit within the body of each poem, almost as though each title sits as a fallen leaf, floating upon the surface of the poem’s small pool. She writes of, as Fady Joudah writes on the back cover, a “Palestinian book in Empire,” writing exile and anticipation, the West Bank and Gaza. In many ways, this is a quiet book that holds incredible power, resonance and urgency, writing out the possibilities of birth in a landscape rife with conflict, suffering and loss; writing out the possibilities of birth while holding to those cultures that surround, whether from outside or within; that particular geography, and the richnessess that live there, all intimately shared with her growing daughter. This book articulates, one might say, a growing hope amid ongoing realities of conflict. Hope, amid the possibility of something further. As she writes, close to the end of the collection: it's a rain & you were born before it | you were born in your body | just like that | no one refutes these areas were made to carry letters & the | letters lapsed | in a world of fewer babies you were born | dear RIOT COSMOLOGY | i never thought i’d be a national vessel | febrile & inlaid | undulating so | we worked hard to be fruitful & plenty

February 23, 2023

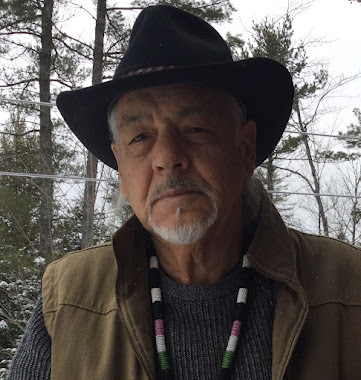

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Garry Gottfriedson

Garry Gottfriedson is from Kamloops, BC. He is strongly rooted in his Secwepemc (Shuswap) cultural teachings. He holds a Masters of Arts Education Degree from Simon Fraser University. In 1987, the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado awarded a Creative Writing Scholarship to Gottfriedson for Masters of Fine Arts Creative Writing. There, he studied under Allen Ginsberg, Marianne Faithful and others. Gottfriedson has 10 published books. He has read from his work across Canada, United States, South America, New Zealand, Europe, and Asia. Gottfriedson’s work unapologetically unveils the truth of Canada’s treatment of First Nations. His work has been anthologized and published nationally and internationally. Currently, he works at Thompson Rivers University.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The first book validated that my work had a place in Canadian literature. It gave me some hope that other Indigenous authors work would offer a place on the Canadian literary scene. I think my most recent work is much more toned down from my previous works. It feels differently because I think the more recent work feels more crafted in the art of writing.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to write poetry by being influenced by other Indigenous poets who had work published. And their work amazed me. When I first started writing, it was a struggle getting into the Canadian publishing world. Much has changed since then. Writing fiction or nonfiction calls for a totally different voice to write from. For me, writing free verse style of poetry comes naturally, and writing other genres is much more challenging for me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I continuously write, so one project bleeds into another. I seem to be a bit of a binge writer, too. I can write nonstop for several days, and then I start to edit the work and shape it. When I've gone through that process, I begin to write more, feeding off the poetry that has been written on that particular project. I also carry around a small notebook and write phrases of words that I might hear, and that line of phrase then becomes a poem later on.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem usually begins by hearing or thinking of a line or two and then it works itself into a poem. I just work with a continuation of poems. I don't think that I've premeditated a book of poetry. It just flows from one poem to the next.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?