Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 101

January 23, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rebecca Griswold

Rebecca Griswold

is an MFA candidate at Warren Wilson. Her debut collection of poems,

The Attic Bedroom

, is out with Milk & Cake Press. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Cimarron Review, Superstition Review, Blood Orange Review, Revolute, Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel and others. She was a finalist for the River Styx International Poetry Contest. She’d describe herself as equal parts Valentine’s Day and Halloween. She owns and operates White Whale Tattoo alongside her husband in Cincinnati.

Rebecca Griswold

is an MFA candidate at Warren Wilson. Her debut collection of poems,

The Attic Bedroom

, is out with Milk & Cake Press. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Cimarron Review, Superstition Review, Blood Orange Review, Revolute, Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel and others. She was a finalist for the River Styx International Poetry Contest. She’d describe herself as equal parts Valentine’s Day and Halloween. She owns and operates White Whale Tattoo alongside her husband in Cincinnati.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The process of writing my first book, The Attic Bedroom, was transformative for multiple reasons. When I chose the subject matter, I had a realization that there was this experience I hadn’t fully explored or reckoned with, and in fact, I was holding it in the very tissues of my body. Choosing to tackle the subject matter opened pathways for me creatively. I followed those pathways with each poem until I found a way out of the woods and into the wide open. It forced me to look the beast straight in the eyes. Additionally, I’d never written on a subject to the extent that I did for my book. Instead of exploring broad themes at a bird’s eye view, I found myself breaking poems down further and further into the minutiae. This has served my work well. I have absolutely grown as a writer and I am thankful to those poems and to that book.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My Uncle and cousin are both poets, and I’d pulled their books from the shelves at my parents’ house from a young age. In high school I was the singer in a band, and I wrote the lyrics for our songs. After we broke up, as bands often do, I was left with the desire to write, but without an outlet. I kept a notebook and that practice has remained with me. Eventually I took poetry courses in college which helped me further find my footing in the genre.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

This varies greatly. I’d say my work is generally a slower process, however some poems fall from the sky for me and that is always an exhilarating experience. When writing feels like a spirit has possessed you and is writing through you, that’s when the best work comes out in my opinion. I don’t mind working for a poem, though.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I always saw myself as an author of short pieces that could sit beside each other in a book, but I’ve become the latter. With The Attic Bedroom, I knew the subject the book would deal with and I wrote on that theme. Currently, I have poems surrounding a new theme and I can see the book in the distance. I have pieces that don’t fit into this theme though, and I’d like to find a home for them as well.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings! I’ve found it encourages me to prepare poems that are close to being ready. It also helps me edit poems that felt ready on the page, but upon reading them aloud I realize they need tweaked. Additionally, I love the community aspect that is inherent in readings: you’re reading with other poets or interacting with attendees. I love the connection as writing is such a solitary act, and I am not a solitary creature.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Do people have answers for this one? I don’t think I know what questions I’m seeking answers to until I arrive at them. Even then, the work often remains a mystery to me.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

We, as writers, are called to different roles. Some entertain, some take on the political, others challenge the status quo. I hesitate to give us a role or a purpose as we often float in and out of these categories. I think a writer’s work has individual purpose, but the writer’s purpose is to write.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I personally like working with an outside editor. I seek the feedback of multiple friends while editing initial drafts, but once I’ve exhausted these avenues, I seek an editor who can look at my work as a whole. I utilized two editors with The Attic Bedroom and it was invaluable.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Leave the self-conscious critic at the door of your writing room. Fear keeps us from writing what we must say, and often keeps us from writing at all. If we can write with complete freedom, we will access our essential work.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I do my best to have multiple writing windows weekly. As a mom with a preschool-aged child, my day begins after I drop him at school. We live within walking distance, and the walk really activates me. I’m like most in that I also need a cup of coffee. I write best in the morning and early afternoon. I’ll light some incense to center myself. I try to offer myself options when I sit at my desk. As long as I am working toward a writing related activity, I count it as progress. Some days I may write, other days I may edit, or I may not feel creative and will send in submissions instead. Either way, I’ve served my writing in some manner.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading poetry is a constant source of inspiration. I have a huge TBR pile that I’m always adding to. Additionally, there are prompts that jumpstart poems for me without fail. One, shared with me in a course by Gerry Grubbs, is “14 first lines.” With this prompt, you choose 14 starting lines from 14 different poems and lay them out on the page. You then write what you think would naturally follow each line, additionally trying to consider what you’ve written already. Once you have these followup lines, you erase the borrowed lines and see what you have. Sometimes multiple poems are born out of this. It usually only takes me 4-5 lines before I end up going down a rabbit hole, never needing all 14.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of a bonfire reminds me of home as we always had wood burning fireplaces.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music is such a source of inspiration for me. So many musicians are incredible lyricists and poets in their own right: Joanna Newsom, Sufjan Stevens, Conor Oberst, just to name a few. My husband is a painter and we regularly visit museums, providing another source of inspiration as well.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Nickole Brown’s poetry had a massive impact on me. Marie Howe, David Young, Kim Addonizio, Jericho Brown, and Ada Limón are also huge in my rotation.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to publish a novel. I would also like to have a hobby farm. Two very different things, but I want them both!

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I was a teacher prior to a deeper focus on my writing, so probably that? I did study photography and worked for a photographer for 6 years, so I could see myself wandering further down that path as well.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing is fulfilling to me. I find pleasure, joy and gratification in the act of writing. Ultimately, I’m doing what I love. I’m grateful to be dedicating much of my time to it, as it know many cannot.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Billy Collins’ Picnic, Lightningwas an incredible recent read. My daughter was in the NICU for 2 weeks following her birth, and that book was a companion to me for some of that time. The Hand of God is the movie that comes to mind for me. My husband will be pleased at this answer, as this was his suggestion.

19 - What are you currently working on?

My current work surrounds the pregnancy and birth of my daughter, Hazel. This pregnancy was fraught with difficulties as she had a rare condition that required close monitoring. Writing through the experience was the only way I could stay afloat.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

January 22, 2023

Sawako Nakayasu, Pink Waves

4

it was a wave all along

a passing moment reveals itself to have cued the long apology

i sat with a friend the loss of her child

sliding between the heat of now and surrender

and then somebody holds your wild you

closer to the range

the specs of a body don’t reveal what it means, so which

body do you want to wear today?

the extent that we need another dollar

I’ve been an admirer of the work of poet and translator Sawako Nakayasu for some time, ever since discovering her remarkable

Texture Notes

(Letter Machine Editions, 2010) [see my review of such here]. Since then, I’ve followed her work through her subsequent

Some Girls Walk Into The Country They Are From

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], Yi Sang: Selected Works, edited by Don Mee Choi (Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here],

The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa

(Canarium Books, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

The Ants

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues Press, 2014) [see my review of such here]. Set in three lettered section-sequences—“A,” “B” and “A’”—lyrics of her latest,

Pink Waves

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2022), exist in a kind of rush, one that nearly overwhelms through a wash or wave of sequenced text; a sequence of lyric examinations that come up to the end of each poem and retreat, working back up to the beginning of a further and lengthier crest. The first sequence, for example, offers an accumulation of eight poems, each opening returning to the beginning, with the line “it was a wave all along.” Each piece in sequence builds upon that singular line as a kind of mantra, rhythmically following repeating variations of what had come prior and adding, akin to a childhood memory game. As the fourth poem of the opening sequence begins: “it was a wave all along // a passing moment reveals itself to have cued the long apology // i sat with a friend and the loss of her child // sliding between the heat of now and surrender [.]” The repetitions, something rife throughout her work to date, provides not only a series of rippling echoes throughout, but allows for the ability to incorporate variety without reducing, and perhaps even expanding, the echo. The fifth poem, in turn, opens:

I’ve been an admirer of the work of poet and translator Sawako Nakayasu for some time, ever since discovering her remarkable

Texture Notes

(Letter Machine Editions, 2010) [see my review of such here]. Since then, I’ve followed her work through her subsequent

Some Girls Walk Into The Country They Are From

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], Yi Sang: Selected Works, edited by Don Mee Choi (Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here],

The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa

(Canarium Books, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

The Ants

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues Press, 2014) [see my review of such here]. Set in three lettered section-sequences—“A,” “B” and “A’”—lyrics of her latest,

Pink Waves

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2022), exist in a kind of rush, one that nearly overwhelms through a wash or wave of sequenced text; a sequence of lyric examinations that come up to the end of each poem and retreat, working back up to the beginning of a further and lengthier crest. The first sequence, for example, offers an accumulation of eight poems, each opening returning to the beginning, with the line “it was a wave all along.” Each piece in sequence builds upon that singular line as a kind of mantra, rhythmically following repeating variations of what had come prior and adding, akin to a childhood memory game. As the fourth poem of the opening sequence begins: “it was a wave all along // a passing moment reveals itself to have cued the long apology // i sat with a friend and the loss of her child // sliding between the heat of now and surrender [.]” The repetitions, something rife throughout her work to date, provides not only a series of rippling echoes throughout, but allows for the ability to incorporate variety without reducing, and perhaps even expanding, the echo. The fifth poem, in turn, opens: it was a wave all along

a passing moment reveals itself to have cued the long apology

the extent that we need another dollar

it’s haptic; it’s your membrane

sliding between the heat of now and surrender

and then somebody holds your wild you

which parts available for naming

atop a sharp manicured nail

Perhaps everything about her work can be described as through water: from waves, eddys and ripples. Throughout Pink Waves, Nakayasu’s poems explore boundaries both physical and temporal, as well as the edges of grief, as the press release offers: “Moving through the shifting surfaces of inarticulable loss, and along the edges of darkness and sadness, Pink Waves was completed in the presence of audience members over the course of a three-day durational performance. Sawako Nakayasu accrues lines written in conversation with Waveforms by Amber DiPietro and Denise Leto, and micro-translations of syntax in the Black Dada Reader by Adam Pendleton, itself drawn from Ron Silliman’s Ketjak.” Given its response structure, there is something fascinating to Nakayasu exploring a work as an ongoing part of a previous conversation, responding not only to particular works, but a work that is itself a response to another. Through this, she allows this work a direct lineage of response, as she offers in her “NOTES & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS” at the end of the collection:

Pink Waves is a structured improvisation: the form, the sentence, the microtranslation, the language from the sources, are the structure with which I improvised in writing, on stage, with others. It is my attempt to be true to the thickness as I move through time and space, in cross-sections of wave upon wave. Some forms of otherness are more specific to my own history, some arrive through the discourse of others. All these spreading differences.

There is something curious in the way her poems, at times, actually stretch across the boundary between the left and right page, bridging the centre and to the other side in a way I’ve scarcely seen beyond the works of a variety of poets experimenting with visual and concrete—bpNichol, for example, who worked very deliberately with the boundaries of the printed page through his work with Coach House. As well, each of Nakayasu’s sequences are structured via eight numbered parts. Toronto poet Stephen Cain has long been known for working sequences as decalogues, but it was Nichol, again, who worked in sequences with eight as his base number over the established ten. And wasn’t it Sting who sang that love is the seventh wave, pushing that every seventh wave from the ocean is stronger than the rest? For Nakayasu, it would seem, her waves are accumulative, offering a build-up that brings an eighth to include all that had come prior; the wave with the most and final power. As the fourth poem in the third sequence offers:

it was a wave, one snapped, who blistered

passing moment reveals itself to have extinguished the

occasional light

that turned stranger into child

sliding between ceremony

and languagelight

world without cold

the specs of a body

and the extent to which it delivers

January 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anvesh Jain

Anvesh Jain was born in Delhi and moved to Calgary when he was one year old. His poems have appeared in literary magazines in Canada, United States, United Kingdom, Portugal, India, and South Africa. He was an editor at The Hart House Review from 2018 to 2021. Anvesh is a chai enthusiast, and loves cricket. Pilgrim to No Country, published by Frontenac House Press in fall 2022, is his first book.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When I was younger—though I am still young—I had certain milestones in mind that seemed to suggest fullness, a life well-lived (or at least, better-lived). I wanted to produce a movie, perform a hit song, write a book. At the time of this interview, my debut poetry book, Pilgrim to No Country, is one month away from shipping. I suspect having it in my hands will fill me with relief; the kind of relief that comes with physicality and undeletability. My first book will be a physical tether. An indicator, I hope, of a life in the process of being better-lived.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In my choice of reading, I’m obsessed with building my foundations and reading lengthy classics. Perhaps it’s an immigrant’s impulse—to demonstrate mastery in the language of the new country, to ingratiate oneself in the traditional canon, to build roots through literature. Whatever it is, I gravitate towards poetry in my writing because of its inherent liberty. Poetry frees me from the trappings of classical foundation.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

In Ottawa’s Byward Market there’s a see-through craft noodle shop by the name of Le Mien. Sometimes I take a moment to peer through the windows and appreciate the process of twisting and pulling and shaping. It’s a fantastic metaphor for writing poetry: starting with the dough of an idea and stretching it to the limits of its possible shape. Some days the kitchen is overflowing with dough, and other times you’ll have to be content settling for ready-made cereals and bread-jam. I’m not sure if I’m still talking about poetry. Perhaps I’m just hungry.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My poems are inspired by my experiences or through interactions with other art and artists from across mediums. I will give an example. The other day, a wasp drowned itself in my drink. So I wrote a poem about it. An hour or two later, a friend happened to join me and the incident repeated itself. This time he fished the wasp out of his drink, and it flew away, grateful for the temporary reprieve. So I changed the ending of my original poem.

I never wrote with the intention of publishing a book. I simply wrote, and one day I realized I had more than enough content to justify a manuscript. Pilgrim to No Country reckons, in large part, with my familial past and the cultural schema in which I’ve been raised. If there is a next book, I will endeavour for it to be more forward-looking in its principles and theme.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Publishing one’s work is paradoxical. I want my work to be read, but not by anyone who knows me. I like public readings, but would much rather read to strangers than to family or friends. I’ve recently begun going to and performing at Jeff Blackman and Bardia Sinaee’s 2-for-1 poetry nights on the last Thursday of each month. Hearing from other writers undoubtedly inspires. I keep reminding myself to bring a notepad, though I seldom remember to follow-through.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Is it trite to answer a question with a quote? In my cover letters to various publishers, I frequently mentioned one by Hanif Kureishi:

And indeed I know Pakistanis and Indians born and brought up here who consider their position to be the result of a diaspora: they are in exile, awaiting return to a better place, where they belong, where they are welcome. And there this ‘belonging’ will be total. This will be home, and peace.

My writing, like Kureishi’s productions, is animated by what it means to be a result of a diaspora. Exile is an anguished word, holding vast resonance in the Indic tradition. Our Lord Rama endured vanvaas for fourteen years; like him, we await our return to that place called Ayodhya, synonymous with the concept of total belonging. In the diaspora, we say that India is our Janma-bhumi(land of birth), and that Canada is our Karma-bhumi(land of karmic destiny). We owe a responsibility to both. I write poetry of place, which attempts to reconcile this home-making with myth-making, and this Canada with India.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I see a role for the writer analogous to that of the professional documentarian. My work is meant to preserve in literature certain essential facts: that there was an Indian community in Canada in the 1990s and 2000s, that we lived in certain places, practiced our faith and culture in certain manners, believed in certain ideas, and contributed to Canadian nation-hood in our own multifarious ways. Though writing ought to be universally resonant, I believe it has to be grounded in the local and the particular in order to achieve true authenticity.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Editors and bureaucrats—can’t do with them, can’t do without them, and together constituting the twin banes of one’s existence. Working with an editor is anger-inducing. It’s a savage and adversarial process. That being said, I am eternally grateful to my editor John Wall Bargerfor his patience and his immense expertise. He knew when to push back, and when to relent. My book is better for his involvement, full-stop and without question.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

That unconventional outcomes require unconventional inputs. I heard that this summer, in an entirely different context to writing, and have since made it my new mantra.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I never force my writing. When it comes, I give myself to my poetry. I allow myself to be subsumed by it. Then there are long and desolate stretches where it never seems to arrive. I took a one-year hiatus after editing Pilgrim to No Country that lasted until this past July. I’m glad to say I’m writing again, though never with any routine in mind.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Writing is my distraction from the stresses and strains of daily life. There are times when I need a distraction from my distraction too. I don’t overly concern myself with dry veins or stalled writing. In those times, I turn to the energetic business of the day-to-day; investing in my legal studies, in my friendships, in cinema, in good books, in social occasions, in religious healing. When the vein runs dry, there is no shame in turning to the replenishments of quotidian being.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Tulsi, neem, sandalwood powder, agarbatti incense sticks. A vacuumed rug. My mother’s cooking. Fallen pines and prairiegrass.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Every interaction has the potential to spark new creative undertakings. Being open and observant allows you to draw inspiration from all the sources you’ve mentioned, and more. I, for one, am especially fascinated by Indian street food vloggers on Facebook.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Hindu liturgy and scripture comforts me. I’m in the process of getting my hands on a faux-leather bound translation of the Valmiki Ramayana. The post-colonial literature of Salman Rushdie, A.K Ramanujan, and V.S Naipaul are of perpetual delight. Mordecai Richler’s work has instantiated Canada within me. In poetry, I like Margaret Atwood, Seamus Heaney, Billy Collins, Bänoo Zan, and Matthew Olzmann.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have a dream of taking a sabbatical from my career one day to write a full-fledged fiction novel. I think I would really, truly like that.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I don’t suppose it’s too late for me to become an international cricket commentator. Whatever line of work I end up in, I’d like to travel. I want to meet interesting people in interesting places. I want to construct the good-life, well-lived and well-worn.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

We write because we are compelled to. It’s as necessary as that. Writing helps us box in our many insanities and neuroses.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Over the past months I’ve managed to get through my first great Canadian novel, that being Solomon Gursky Was Here by Mordecai Richler. The last great film? Probably Superbad (2007).

19 - What are you currently working on?

Law school, finding an internship, finding a suitable answer for my parents when they ask me why I don’t have a girlfriend yet. Getting back into writing poetry and appreciating all the other sources of beauty for which we ought to express thanks.

To keep up with my comings and goings, please visit me at https://anveshjain.com/.

January 20, 2023

i've been solo with the young ladies all week,

so responses a bit slower, in case you require one. Christine is two weeks at the Banff Writers Studio working on poems (from edits to her forthcoming third title to sketching out poems for her potential fourth), as I am solo with our young ladies until January 28th. Most of it is fine, although it is a bit tricky to convince both children into the car for 7:40am, to transport Rose over to school, over an hour before Aoife and I need to leave the house. Otherwise, I am working on my usual slew of reviews, my book-length essay (have you checked out my substack?) and even some poems (accidentally), as well as various house-cleanings (easier, a bit, when dear wife away). The young ladies and I have had a couple of adventures since Christine left on Saturday, including a visit to my sister out by the homestead, and even brought her one of the many cakes the young ladies insisted on baking that morning (we still have a couple of those cakes). Is it too late to start giving out any of these cakes? And what other adventures might we get up to?

so responses a bit slower, in case you require one. Christine is two weeks at the Banff Writers Studio working on poems (from edits to her forthcoming third title to sketching out poems for her potential fourth), as I am solo with our young ladies until January 28th. Most of it is fine, although it is a bit tricky to convince both children into the car for 7:40am, to transport Rose over to school, over an hour before Aoife and I need to leave the house. Otherwise, I am working on my usual slew of reviews, my book-length essay (have you checked out my substack?) and even some poems (accidentally), as well as various house-cleanings (easier, a bit, when dear wife away). The young ladies and I have had a couple of adventures since Christine left on Saturday, including a visit to my sister out by the homestead, and even brought her one of the many cakes the young ladies insisted on baking that morning (we still have a couple of those cakes). Is it too late to start giving out any of these cakes? And what other adventures might we get up to?

January 19, 2023

Meredith Stricker, REWILD

How the Invisible sanctuaries sight

protects

the infinitely small

preserves us (fission-stained)

from ourselves, from our burrowing into the visible

like weevils in spilled flour who would unhusk

every atom, crack open every geode, leave nothing dark

and hidden and its own

the sound of eagles over the Mississippi

a biplane treefrogs at dusk

o star fall (“UNDERTOW”)

I’m very pleased to be able to move deeper through American artist and poet Meredith Stricker’s “cross-genre media” work, specifically through her recent poetry title,

REWILD

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2022). REWILD follows an array of prior collections, including Alphabet Theater (Wesleyan University Press, 2003),

Tenderness Shore

(LSU Press, 2003),

mistake

(Caketrain Press, 2012),

Our Animal

(Omnidawn, 2017) and Anemochore (Newfound Press, 2018). This is a collection that splices genre across the lyric, layering details of narrative, memoir, fragment and essay, providing echoes that provide her lyric such fine texture. Through four sections of fractured, staggered lyrics—“STARING INTO THE ATOM,” “ASHES,” “DARK MATTER” and “”UNBUY YOURSELF”—Stricker explores open questions on capitalism, science, language, human history and environmental concerns, offering a lyric of such precise movement and quick wit, propelled across of points of crafted acceleration. There is something of Stricker’s assemblage of blended genre reminiscent of the work of American poet Lori Anderson Moseman, specifically her poetry collection

DARN

(Delete press, 2021) [see my review of such here], working to blend from such myriad shapes and sources into a similar kind of collage. There is something of the visual use of space on the page and the staggered fragment that both poets seem to share, also. Time moves differently across Stricker’s lyric, it would seem; a pacing that steps, stops, leaps and staggers while simultaneously propulsive, even across staggers that read like steps, such as the ending to the short poem “I’M MAKING AN INVENTORY / OF THE WORLD,” that reads:

I’m very pleased to be able to move deeper through American artist and poet Meredith Stricker’s “cross-genre media” work, specifically through her recent poetry title,

REWILD

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2022). REWILD follows an array of prior collections, including Alphabet Theater (Wesleyan University Press, 2003),

Tenderness Shore

(LSU Press, 2003),

mistake

(Caketrain Press, 2012),

Our Animal

(Omnidawn, 2017) and Anemochore (Newfound Press, 2018). This is a collection that splices genre across the lyric, layering details of narrative, memoir, fragment and essay, providing echoes that provide her lyric such fine texture. Through four sections of fractured, staggered lyrics—“STARING INTO THE ATOM,” “ASHES,” “DARK MATTER” and “”UNBUY YOURSELF”—Stricker explores open questions on capitalism, science, language, human history and environmental concerns, offering a lyric of such precise movement and quick wit, propelled across of points of crafted acceleration. There is something of Stricker’s assemblage of blended genre reminiscent of the work of American poet Lori Anderson Moseman, specifically her poetry collection

DARN

(Delete press, 2021) [see my review of such here], working to blend from such myriad shapes and sources into a similar kind of collage. There is something of the visual use of space on the page and the staggered fragment that both poets seem to share, also. Time moves differently across Stricker’s lyric, it would seem; a pacing that steps, stops, leaps and staggers while simultaneously propulsive, even across staggers that read like steps, such as the ending to the short poem “I’M MAKING AN INVENTORY / OF THE WORLD,” that reads: yellow flowered fennel covered in road dust

you can’t pay for the dust, it comes for free

the roar of crickets on a back road –

what would you pay for this

night and its impenetrable

avalanche of stars

There is such impulse through the work of this collection, one that presents an urgency as well as a clarity, simultaneously through form and through concerns around the impact of ongoing human conflict and environmental plunder. “how lucky when the wind turned and the scent was lost,” she writes, as part of the poem “DARK MATTER,” “the wind that rushes now insensate through interstate / exchanges, dear fleet-foot, you gave us everything / and you were always coursing bright and red [.]”

January 18, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Marshall Bood

Marshall Bood

lives in Regina, Saskatchewan with his beautiful cat. His debut collection is

Spring Cleaning

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021).

Marshall Bood

lives in Regina, Saskatchewan with his beautiful cat. His debut collection is

Spring Cleaning

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021).1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

UDP placed so much care into creating my hand-bound chapbook — my sense of gratitude increased.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Not long after my uncle played a Leonard Cohen album for me, I soon found the Cohen poetry volumes in my Mom’s library.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s usually very fast. Usually there is only one draft.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Most of my poems will probably never be in a book form. I look ahead to deadlines of journals.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Bad stage fright — hoping to overcome this with more practice.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. I ask myself questions like is litter more beautiful inside or outside.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I can really speak only for myself, but I think that poetry is healing.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

All of the poems in my chapbook were previously published so there weren’t a lot of edits. My editor did a great job helping me select the poems and minor edits.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was recovering from psychosis and I wanted to get back to reading so badly, another patient told me, “Sometimes you just hold onto a book.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try to stay alert throughout the day. Taking my notebook and pen out in the morning seems to help — my cat thinks they are toys.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I go for long walks. I also try to turn my ruminating into poetry — lemonade out of lemons.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Coffee — my Mom was a high school teacher.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Maybe film because my poetry is very visual.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The beats including the lesser known ones like Jack Micheline and Lew Welch —even though most of them didn’t like the term beat. Charles Bukowski also. I think Alan Pizzarelli has inspired me a lot. I agree with most that Sanford Goldstein is the greatest English language tanka poet. Buson is my favourite haiku master. My earliest poems all sounded a bit like Leonard Cohen. I went through a Frank O’Hara and other New York School Poets phase.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have a bucket list of books. I keep finding more books to read.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think comedian because I like making people laugh. I use humour in my poetry sometimes.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I love reading!

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Glamorama by Bret Easton Ellis. It is his greatest book. Titane would be my film choice. I usually go to the discount theatre and see them on the big screen to get the full experience.

19 - What are you currently working on?

A collection of micropoetry. The one’s that will never fit into a book are just as important to me, though.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

January 17, 2023

(no subject), by Peter Burghardt

My review of (no subject), by Peter Burghardt (Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2022) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of (no subject), by Peter Burghardt (Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2022) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.January 16, 2023

WJD, by Khashayar Mohammadi / The OceanDweller, by Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Khashayar Mohammadi

My review of WJD, by Khashayar Mohammadi / The OceanDweller, by Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Khashayar Mohammadi (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of WJD, by Khashayar Mohammadi / The OceanDweller, by Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Khashayar Mohammadi (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.January 15, 2023

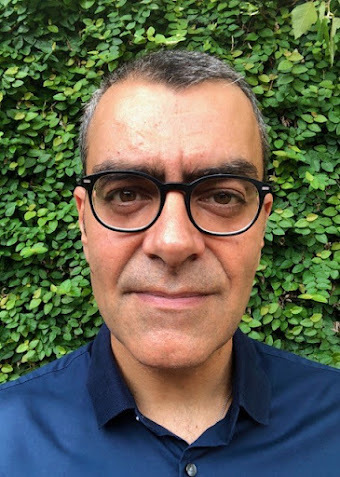

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Hayan Charara

Hayan Charara is a poet, children’s book author, essayist, and editor. His poetry books are These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit (Milkweed Editions 2022), Something Sinister (Carnegie Mellon Univ Press 2016), The Sadness of Others(Carnegie Mellon Univ Press 2006), and The Alchemist’s Diary (Hanging Loose Press 2001). His children’s book, The Three Lucys (2016), received the New Voices Award Honor, and he edited Inclined to Speak (2008), an anthology of contemporary Arab American poetry. With Fady Joudah, he is also a series editor of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. His honors include the Arab American Book Award, a literature fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Lucille Joy Prize in Poetry from the University of Houston Creative Writing Program, and the John Clare Prize.

Born in Detroit in 1972 to Arab immigrants, he studied biology and chemistry at Wayne State University before turning to poetry. He spent a decade in New York City, where he earned a master’s degree from New York University’s Draper Interdisciplinary Master’s Program. In 2004, he moved to Texas, where he eventually earned his PhD in literature and creative writing at the University of Houston.

He has taught at a number of colleges and universities, including Queens College, Jersey City University, the City University of New York-La Guardia, the University of Texas at Austin, Trinity University, and Our Lady of the Lake University. He is a professor in the Honors College at the University of Houston, where he also teaches creative writing. He is married, with two children.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

No huge changes came about because of my first book, though I suppose that’s a relative perspective. For example, my saying “I’m a poet” became a more acceptable response to the question, “What do you do?” But you can be a poet without a book—poets know that. And honestly, I wouldn’t really answer the question that way—the conversation to follow is usually insufferable.

My first book, The Alchemist’s Diary, came out a few days the September 11thattacks, and I was living in New York at the time. That event—more than my book or me—shaped how others saw my identity, as an Arab. Unfortunately, it became more integral to how people saw me or my poetry than my poetry itself.

My most recent book, These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit, to me at least, feels lightyears away from my first book. Two decades on, I am a different person in significant ways—the same in some, sure, but I am more aware, have more knowledge, am a deeper, sharper thinker, am better skilled at making poems and knowing how they work, have children, have been married, divorced, married again, have a career (as opposed to a slew of bad-paying dead end jobs), and so on. It would be disappointing and seemingly impossible if after twenty years of life I didn’t feel differently or make poems differently. The biggest difference is that I know what I’m doing now to a degree that was unimaginable in my twenties—or, more accurately, that as a young poet I didn’t realize and didn’t care about. Again, you hope this is typical of any practice, and I hope it continues. If I’m still around and writing poems in another twenty years, I would love to be able to look back and see that I my handle on poetry got stronger.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I write both, and wrote both early on, and even though I felt writing poetry to be more taxing on me, I improved as a poet far more quickly than as a prose writer. It’s as simple as that. It probably isn’t, but that’s good enough for me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am a slow writer, and my revision process is even slower. Some poems go through dozens of drafts and take years to arrive at their final version. In some cases, even with very short poems, I have up to fifty drafts. More importantly, I’m in no rush whatsoever for a poem to be done. As an example, the long, centerpiece work in These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit, “Fugue,” took about 12 years to finish.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually, my poems begin with a realization or an idea, one that comes about outside of me thinking about poetry or setting about to write a poem, which is not an act I am very good at. I have had very little success, if any, at sitting down to write, with the intention of creating a poem, and then actually doing so.

And I’ve never worked on a book, not strictly speaking. I think and work one poem at a time. The idea of a book project, or a series of poems, that gives me anxiety. This may explain, in part, why it has taken me so many years to pull together each of my books.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like getting up in front of people and talking and knowing that they want to hear me talk or read. This makes being a poet and a teacher a lot easier. I have my limits, though. It’s emotionally draining to read my poems, and to give a lecture (something I do at the Honors College at the University of Houston, where I’m part of a year-long course, which I teach with several other professors, and we give traditional lectures, nearly an hour-long each, in front of 300 students). So ideally, I’m doing a limited number of each. Anyhow, the readings, I don’t think they are part of my creative process—they are performances. I’m reading, not creating in the moment. Giving a lecture is a different story because while I have much of what I want to say already down in notes, I am also thinking on the spot, and ideas will come to me and lead me to other ideas, realizations, and so on that I would otherwise have not gone to.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

All my books, in their own way, dwell on and participate in a variety of concerns, from identity to violence to ecology. I find it close to impossible to read any work of literature and not uncover such concerns, if not simply see them on the surface, the exception being those writings that go out of their way to demystify just about everything—and even then, they still speak to somethingoutside the work itself.

I’ve read and taught ancient literature for many years, and those works reveal that our many of our concerns today are old as dirt. Some are new, obviously, but if they are described generally enough, it becomes clear that we’ve been dealing with similar problems as the ancients, just differently. I’m not 100% sure, for example, that my children, if they choose to raise children of their own, can even live where we now live. Another way to state this concern: our world is falling apart, is fragile. We live in Houston, and there’s a strong possibility that in a few decades, the geography will change so dramatically, because of the climate crisis, that the city as we know—portions of it, at least—may not be inhabitable or else may be too dangerous, too unpredictable to live in. It already feels that way. Only a few years ago, Hurricane Harvey dumped 60 inches of rain on parts of Houston—that’s 33 trillion gallons of water, in about a week. Places that have never flooded, not since records began being made, were under water. That’s a concern. But is it new? No.

I’ve also always been very concerned with political violence, the history of which has unfortunately touched the lives of my family all too closely. And that kind of violence, from the perspective of the last few decades, seems ever more likely. It was always present in my family’s homeland (Lebanon), and in my hometown (Detroit), and it seems to be more pervasive today, more spread out, targeting more people, more groups, and the rules have changed, the technology on which violence thrives has become more sophisticated.

The list of concerns goes on and on.

What I won’t do, as far poetry goes is allow the concerns to take the reins. I’m not writing theory, I’m not writing newspaper stories, or history, or memoir, or political manifestos. Yes, genres blend. Yes, disciplines inform each other. Yes, the boundaries are porous, and at times they disappear. But I write poetry, which is to say that’s what I have in mind when I am making a poem. This informs not only what I do and how I do it, but also what I knowingly resist.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

After years and years of thinking about this question, because we’ve been asking it of writers for a long time, I’ve arrived at a very simple reply, one that I believe wholeheartedly. First, we should do good. Second, “we” is not limited to “writer”—by “we” I mean all of us, everyone, regardless of our many titles or roles (no one is only a writer, after all). What doing good requires is constant and continual reassessments of the good we do, the good we believe in, the good that we may not know, the good that’s required of us. It’s never-ending, constantly changing work—being and doing good.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

During the “draft” period, I only show my poems to a few people—less than a handful. And even then, they only see drafts that have gone through many revisions. Once those poems make it into a book, which has so far happened four times for me, I’ve only worked closely with editors or readers twice—once with my first book and the second time with These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit.

Hanging Loose Press published my first book, The Alchemist’s Diary, and I spent a couple hours on the phone with an editor going over line edits. That was it. My second and third books, The Sadness of Others and Something Sinister received no editorial feedback other than what I had sought out from friends. With These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit, I received excellent copy-editing feedback from a few of the readers at Milkweed Editions, and minor as the changes were, they strengthened the poems, and I’m grateful. Both instances, by the way, with Hanging Loose and Milkweed, were pleasant, and for that I’m grateful.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t seek the admiration of people whose work you do not admire.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to children's books to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I feel comfortable moving between genres, though I haven’t always. The transition from poetry to prose proved to be the most challenging mainly because some of my habits as a poet, which became ingrained in my writing practices, turned out to be obstacles to writing the kind of prose I wanted to write. The way that poems can condense story into a few stanzas or even a few lines doesn’t necessarily work well with fiction. Even an epic poem does not do narrative, plot, characterization, and so on the way that a novel or short story does. Simply, the readerly expectations differ, dramatically, and it took lots of practice, and failure, for me to learn how to adjust my writerly habits accordingly.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

In my 20s, I wrote late at night, sometimes until the early morning hours. In my 30s, I wrote for several hours each day, in between work, classes, after waking up, before going to sleep. I became a father at age 38, and it was around then that the writing routines vanished. Now, I write when I can, however much I can. And if I cannot write, I don’t sweat it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I have no problem at all going long periods without writing. I don’t think of these periods as writer’s blocks or being stalled, either. I am just not writing. I’m still thinking, reading, being in the world, and those things have always determined what I write, how I write. If I haven’t written in a while, those will perhaps lead to something. If that happens, great. If not, that’s fine, too, and at that point I suppose I will be done writing.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

When I hear the word “home,” I invariably think about my childhood home, in Detroit. And cliché as it may be, I go to my mother’s cooking. Her food was delicious. Friends would gladly drive long distances to eat her food. She almost always used sauteed garlic in her dishes, and loved to use olive oil, so those two things, especially together in a frying pan, that’s the scent of home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

That’s so true, so often—our own ideas, stories, myths, and so on growing out of, coming from other writings. It’s why we know so much about our ancestors, however far back we go; it’s why we can know so much—almost all our ideas, stories, myths, gods, devils, philosophies, discoveries, were preserved and passed down through the written word. But, yes, other forms inform and influence my work. The one that I’ve become much more attuned to than ever before doesn’t quite fit the categories above, and in fact it’s more a lack of form than the presence of one. I have aphantasia, which is the inability to make mental images or to be able to form a mental image of an abstraction. When I close my eyes, and I “think” of a person, object, place, thing, or even an abstract image (counting sheep), I cannot see anything in my mind’s eye. There’s only darkness. If I think of a tree, I know what a tree is, and I’ve seen many obviously—my mind understands “tree”—but I cannot form the image.

This is something I realized only several years ago. I also took phrases like “mind’s eye” and “picture in your head…” to be figurative, not literal. Then I discovered that people do in fact see images—that people can recall images in their minds, that they actually see narratives unfolding when they read stories. That is amazing. It’s amazing because I cannot.

This realization about myself led to another: that my inability to make mental images has influenced how I use images in my own writing. Which is to say, imagery is central to my work. When I’ve admitted my aphantasia to others and suggested a strong link between this condition and the imagery found in my writings, people have usually responded with surprise. Their surprise, I translate as follows: “How can you write imagery if you can’t see it?” To me, the opposite seems to be truer: How can a writer who cannot not make images in their mind not insist on them in their writings?

As a reader, I am grateful for vivid, exact, and unforgettable images and descriptions precisely because I cannot see them in my mind. If the writer makes me feel images more deeply, more viscerally, then the “images” stick with me, resonate with me, and impress upon me. If a piece of writing is impoverished, in terms of imagery, then I don’t see anything. So I took it as a given that in order for imagery to make an impact, it had to be very well-written, and clear, and concise, and memorable.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love and admire great stand-up comedy. Over the last several years, I’ve been listening to comedians the way I read poets, paying attention to what they do, how they do it, and that’s impacted my own writing. For a story to be funny, for a joke to land, it has to be well written; it relies on structure, on pattern, or timing, on sound, and so on.

The best stand-up comedians have made me laugh out loud, to cry tears of laughter, even as they’ve touched difficult subjects. But they could also be talking about the dumbest, most ridiculous thing you can think of. Either way, they bring joy. And there’s not enough of that in the world.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Move to another country.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wanted to teach early on, though I did not pursue that until graduating from college. As an undergraduate, I thought I would become a doctor. My parents thought so too, and so when I decided to quit pursuing that path—about three years into a pre-medicine curriculum as a college student—it upended the dreams my parents had for me. By then, I was sure, too, that I wanted to be a poet. And I pursued the two, teaching and poetry.

For several years, I used to make furniture (stand-alone cabinets, beds, chairs), and I sold a few pieces to the few people who came across what I had made or heard about my woodwork through word of mouth. For half a minute I considered going to a woodworking school. But I wanted to make fine furniture, unique pieces, and I assumed, rightly or not, that I wouldn’t be able to make a living doing that—instead, to make ends meet, I figured I would have to churn out kitchen cabinets or built-in bookcases, which I didn’t want.

I love watches, and I’ve learned how to repair them. I’m not an expert, but I can buy watches that need repair, whether new or vintage, and most of time I can bring them back to life and make them look and run like new. But, again, to do watch repair, or watchmaking, or watch design as an occupation means getting into business and that has never interested me.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

When I came to writing, my life was chaotic, out of control, and out of my hands. I needed something that would allow me to impose some measure of control and order to my life. Writing did that. Other practices may have achieved the same thing, but I found writing first. Had it just been writing in and of itself, I doubt I would have stuck with it. That is, along with writing poetry came new relationships and friendships, with other poets, with teachers, with communities.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Every Fall, I teach texts from antiquity, and I just finished rereading The Iliadand am starting Antigone—both great books. A more recent book I read that was incredible: The Trembling Answers, a poetry collection, by Craig Morgan Teicher.

As for films, while it’s not that recent, I just watched Ziad Doueiri’s West Beirut, which made me laugh out loud and broke my heart.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Trying to stay sane while raising pre-teens. I may not be succeeding.

January 14, 2023

Spotlight series #81 : Nathanael O'Reilly

The eighty-first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly.

The eighty-first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi and Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee.

The whole series can be found online here.