Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 103

January 3, 2023

Ongoing notes: early January 2023: Lillian Nećakov + Miranda Mellis

The first notes of the new year! There are so many notes. And did you see my report of our recent holiday gathering via The Peter F Yacht Club? Or the next event on our calendar, a Covid-era memorial of the poets we've lost?

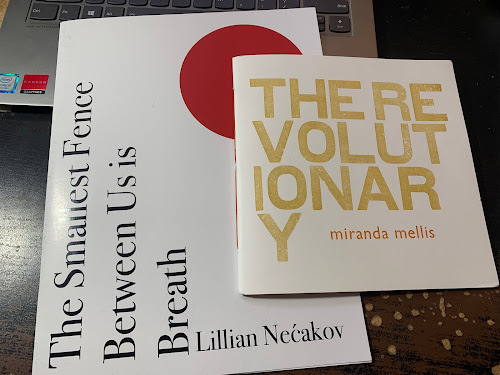

The first notes of the new year! There are so many notes. And did you see my report of our recent holiday gathering via The Peter F Yacht Club? Or the next event on our calendar, a Covid-era memorial of the poets we've lost? Hamilton/Toronto ON: Thanks to a package a while back from Gary Barwin, I’ve been going through Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov’s chapbook The Smallest Fence Between Us is Breath (serif of nottingham, 2022) [see my review of her most recent full-length collection here], a short assemblage of sixteen first-person prose poem observations and meditations on dailyness, with a shimmer of surrealism. “Remember when I wrote 1,000 times about those birds.” she writes, to begin the opening poem, “Myrna Loy,” “I thought I was building / you a lighthouse but you were mesmerized by the slow drag of darkening shoals / and inlets. And after an entire year of chirping I let go the voodoo, the inkwell, / your sulphur hair. I let the quicksand pull you into her muscly embrace as if it was / nothing more than a dream.” Nećakov’s sentence-stanzas appear to be constructed as singular breath-thoughts, each of which accumulate into something far larger, such as the seven standalone sentence-stanzas of “Magic Plants,” the first three of which read:

There is a ring of laughter around our street, day moves clockwise into evening, the empire settles like a déntente over drowsy dogs and magic plants.

Soon my daughter’s watermarked voice adorns the room with divine secrets and the golden filaments of threadbare languages.

Table abloom with cards of diligence and fortune, she leans down, presses her hand against the dog’s soft underbelly, there is a tiny village, here, filled with Slavic jazz operas and your mother, counting on you to remember.

In other poems, stanzas might include more than one sentence, yet she still employs the stanza itself as her breath-thought, something complete unto itself, a brick to set atop another to construct the larger narrative of each prose poem. Each break between stanzas, perhaps, a chance to catch breath. I’m really enjoying the shifts in her writing through these prose pieces, and am curious to see if and how a potential full-length collection of such pieces might emerge. And doesn’t she have a full-length collaboration with Gary Barwin out later this spring with Guernica Editions?

Charlottesville VA: The latest from Brian Teare’s Albion Books is The Revolutionary (2022) by American poet,writer and philosopher Miranda Mellis, produced as the third title in Albion Books’ series eight. The author of numerous titles [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], the only title of hers I’d seen prior is the extended sequence of numbered bursts of lyric philosophy, DEMYSTIFICATIONS (New York NY: Solid Objects, 2021) [see my review of such here]. The Revolutionary is built as an extended lyric memoir on and around grief that explores the effects and implications of being raised by revolutionaries, politics and childhood grief, and the Covid-era death of a father lost years before. There is such tenderness and care through Mellis’ lyric mode, one that sweeps with more openness than perhaps straighter prose might have allowed. “A school for the living by the dying: this is what it is; this is how it happens;” she writes, mid-way through the collection, “from the terminal diagnosis to the cessation of food and drink. From the wet rattling breath, to the liminality of the incommunicado, warm heart still beating, short fast breaths pulling the body up and down on the death bed.”

They were revolutionaries. How do revolutionaries raise children? We were raised not to expect or need too much, not to think of ourselves as special, to do our share of the work, to oppose exploitation and state violence. We were raised to understand police terror, to be angry, to be frustrated, to be shocked, to be outraged, to be militant, relentless, engaged, committed, to be freedom fighters.

What makes a person a revolutionary? What makes them, like Sophocles’ Antigone, volunteer for grief? What gives them the power to act, in the name of revolution, for revolution? What is it that calls a person to try to end not just their personal suffering, but all suffering?

We were not raised to be patient with sadness, sorrow, grief. Sadness, sorrow, and grief were to be gotten rid of in order to return to the fight. “Don’t mourn, organize.”

January 2, 2023

Dale Tracy, Derelict Bicycles

UNDER EVERY MYSTERY, ANOTHER

Thrown from my sled I skid through snow

on my knees. I look back at my tracks before

knowing I’ve come to rest on deer carcass.

Hating waste, I think perhaps I could eat it.

How did it die? There is a dead wolf, mouth

open, too, beneath the thin drift, but it missed.

A handle emerges from the deer’s shoulder:

I pull. The shovel opens the body into a round

tidy room, wood stove still smoking, TV on,

occupant gone.

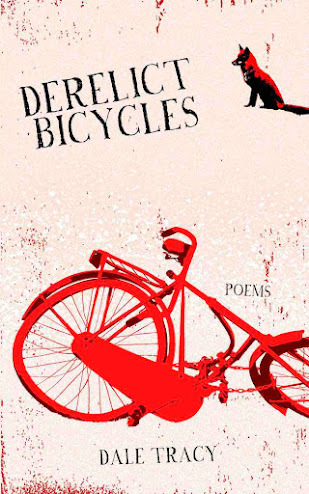

Following several chapbooks and a critical monograph comes the full-length debut from British Columbia-based poet and critic Dale Tracy, her

Derelict Bicycles

(Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2022), published recently as part of editor Stuart Ross’ series, A Feed Dog Book. Through nearly one hundred pages of short, first-person lyrics, Tracy’s narratives fold in and over themselves, offering a rhythm of furtive quickness, even as she slowly pulls and peels back layers of inquiry. “Breach the fussy haze / and tamp the cloud-winked light.” she writes, as part of the poem “THE ORDER OF MUSTARDS AND ALLIES IS MINE,” “End to end, I’m aging, wrapped in clear / violet film, ushering stunt authority, / the nutshell’s ache.” There’s a kind of carved, honed bounce to her language, rhythm and pacing, a deft way of moving across the line and the page through an array of fables and folk tales, observational sheens and surreal hints. “I ate my own shadow.” she offers, to open the poem “STOMACH END OF THE TONGUE,” “I feel it pulling on the stomach end of my tongue.”

Following several chapbooks and a critical monograph comes the full-length debut from British Columbia-based poet and critic Dale Tracy, her

Derelict Bicycles

(Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2022), published recently as part of editor Stuart Ross’ series, A Feed Dog Book. Through nearly one hundred pages of short, first-person lyrics, Tracy’s narratives fold in and over themselves, offering a rhythm of furtive quickness, even as she slowly pulls and peels back layers of inquiry. “Breach the fussy haze / and tamp the cloud-winked light.” she writes, as part of the poem “THE ORDER OF MUSTARDS AND ALLIES IS MINE,” “End to end, I’m aging, wrapped in clear / violet film, ushering stunt authority, / the nutshell’s ache.” There’s a kind of carved, honed bounce to her language, rhythm and pacing, a deft way of moving across the line and the page through an array of fables and folk tales, observational sheens and surreal hints. “I ate my own shadow.” she offers, to open the poem “STOMACH END OF THE TONGUE,” “I feel it pulling on the stomach end of my tongue.” Across a lyric populated with foxes, shadows and flyers posted to telephone poles, Tracy examines physical and psychological descriptions of the body’s usage, employing threads of surrealism almost as a way to clarify, sliding meaning up against uncertainty as a way to reveal conclusions that one might otherwise be unable to reach. “The crooked little valve at the front of my heart / greets you,” she writes, to open the poem “A MILLIMETRIC WELCOME,” “so a little blood leaks through / and back again. The heart’s courtyard grimes / in the wind, the pressure in the vessels. / Anyway, the opposite isn’t pure but emptier.” As part of her 2019 interview for Touch the Donkey, she explains that: “Because writing poetry is for me a kind of theoretical or philosophical endeavour, each poem is prompted by curiosity. A poem helps me figure something out (or at least think about it), so it responds to wonder (as in wondering and as in marvelling) and tries to capture that wonder.” Further on in the same interview, she offers:

Poetry is a way for me to sort out how to live or what I am living; at the same time, a poem often theorizes itself, sorting out in an observable way what a poem can do or is doing. In these ways, I think of poetry as being theory.

December 31, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sam Szanto

Sam Szanto

lives in Durham, UK. Her debut short story collection

If No One Speaks

was published by Alien Buddha Press in 2022. Over 50 of her stories and poems have been published/ listed in competitions. As well as her many published stories, in April 2022 she won the Shooter Flash Fiction Contest, was placed second in the 2022 Writer’s Mastermind Short Story Contest, third in the 2021 Erewash Open Competition, second in the 2019 Doris Gooderson Competition and was also a winner in the 2020 Literary Taxidermy Competition. Her short story collection Courage was a finalist in the 2021 St Lawrence Book Awards. She won the 2020 Charroux Prize for Poetry and the First Writers International Poetry Prize, and her poetry has appeared in a number of literary journals including The North. Find her on Twitter: @sam_szanto

Sam Szanto

lives in Durham, UK. Her debut short story collection

If No One Speaks

was published by Alien Buddha Press in 2022. Over 50 of her stories and poems have been published/ listed in competitions. As well as her many published stories, in April 2022 she won the Shooter Flash Fiction Contest, was placed second in the 2022 Writer’s Mastermind Short Story Contest, third in the 2021 Erewash Open Competition, second in the 2019 Doris Gooderson Competition and was also a winner in the 2020 Literary Taxidermy Competition. Her short story collection Courage was a finalist in the 2021 St Lawrence Book Awards. She won the 2020 Charroux Prize for Poetry and the First Writers International Poetry Prize, and her poetry has appeared in a number of literary journals including The North. Find her on Twitter: @sam_szanto1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

All my work has always been different - you'll be able to tell from reading my current story collection 'If No One Speaks' that all my stories feel very different and are about very different people, as well as being located all over the world. One reviewer said it was amazing that all the stories had been written by the same person - I believe that was meant as a compliment!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to novel writing first, but I've written poems for a long time too. Short stories came a little later.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I do everything fast, from speaking to walking to writing. Sometimes I'll leave a poem or story and come back to it with a slightly different idea that improves it immeasurably, sometimes things come fully formed. The MA in Writing Poetry course I'm currently taking has helped me work on shaping poems though, as rewriting is part of the craft we're learning.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Definitely the former, the stories have to find their own ways of threading together.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don't enjoy speaking in public, but it's something I want to get better at. I've put myself forward for a live Twitter reading that my publisher has organised in a few weeks' time so will see how that goes! I'm happy to pre-record a reading though - it's the live speaking rather than the being watched that makes me nervous!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don't write to answer questions, but I usually do realise what I've actually written about once I've finished a story - I've written quite a few stories that I thought were just about relationships that I realised later were about grief.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writing has many purposes. We are teachers, we are entertainers, we are role models. But what I do always think of when I consider this type of question is a comment a novelist once made to me, which is that most people only read books in bed (before they go to sleep) or in the bath. We all think our writing is terribly important and impactful, and sometimes it is, but I try not to forget that really people just want to hear a story, just as my little children do before they go to bed, just as people have always done.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I actually work in a freelance capacity as a copy-editor so see it from the other side - a lot of the time, people ignore my brilliant suggestions and just do what they want to do. I pretty much accept whatever an editor says to me, though - they're the reader, after all, the person I'm doing this for. Once I've finished writing a story and given it to an audience, it's not really mine. However, I have felt a bit patronised occasionally! This has never happened with poetry, actually, only short stories (but not often).

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Pretty much everything Ernest Hemingway had to say about writing. I love his advice to omit what you feel is the last part of the story to leave the reader wanting more.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

Easy, and necessary. Writing in the one genre constricts me if I do it all the time. Sometimes an idea just works as a poem but not as a story, or vice versa. It happened to me recently that I retold a piece of flash fiction as a prose poem and it worked to great acclaim.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't really have one, as I have young kids who have to take priority, plus occasional freelance work. I write when the kids are at school and as much as possible at all other times.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Other people's writing.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Fresh paint at the moment!

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, yes. Transport, too, I get a lot of creativity from journeys. People, though, are my main influences: their conversations, their mannerisms, their jobs, everything about them.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many! Tessa Hadley, Curtis Sittenfeld, Kate Atkinson, Rose Tremain, Simon Armitage, Carol Ann Duffy, Moniza Alvi, Rebecca Goss, my writing tutors and the other writers I know...

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Have a novel and a poetry book published, travel to Japan/Canada/New Zealand, help my children to grow up happy (hopefully this will happen!)

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I've done many things... worked in marketing for a blind charity, a school and an engineering corporation; sold ice cream and shoes. I still do freelance as a copy-editor and an English tutor so would still be doing that (more often) if I didn't also write.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had to write. There was never another goal.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I loved Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld. I'm not that into films, really - I was obsessed with The Doors film as a teenager, though. On TV, I currently love Mad Men .

20 - What are you currently working on?

A novel that wants to be a thriller but we'll see... I'm about to start the second year of my MA in Writing Poetry, though, so will be writing a lot of poetry pretty soon!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 30, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ned Baeck

Ned Baeckstudied Liberal Arts at Concordia University and Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia. His poetry has appeared in The Continuist, untethered, Sewer Lid, Ottawa Arts Review, Prism, The Nashwaak Review, Poetry Pause, and can be found in the Sunshine in a Jar Facebook page under The Story of Water, curated by Jessica Outram. Originally from Ontario, he has made his home in Vancouver, BC for most of the last 20 years. He partially fulfilled a dream in 2019, spending 5 months training in a Rinzai Zen temple in Okayama, Japan.

Ned Baeckstudied Liberal Arts at Concordia University and Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia. His poetry has appeared in The Continuist, untethered, Sewer Lid, Ottawa Arts Review, Prism, The Nashwaak Review, Poetry Pause, and can be found in the Sunshine in a Jar Facebook page under The Story of Water, curated by Jessica Outram. Originally from Ontario, he has made his home in Vancouver, BC for most of the last 20 years. He partially fulfilled a dream in 2019, spending 5 months training in a Rinzai Zen temple in Okayama, Japan. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was sort of a reckoning…of years of chronic alcoholism, homelessness, drifting, fear. Not that there wasn’t any love or light rising…I was able to look back with clear eyes and see the present breaking free of it. As I described it to a friend, it was my punch, after I had taken a good few. I wanted it to stand strong, and I think it did. Having Wait published by Guernica gave stolidity to the time capsule, and to the line I had crossed in righting my course. I’d published a chapbook with Luciano Iacobelli’s Lyricalmyrical press, but it was adolescent, this was my first real book, and it freed me, as I walked, of the tentacles I’d lopped off in creating it.

Cage of Light is a different animal. I didn’t work any less hard on it, but it didn’t come as smoothly. In Wait, I was looking back on a span of time from a position of privilege (having stopped drinking and flailing 3 years previous), and it emerged under the light of renewed consciousness. The new book, though it still contains poems about addiction and recovery, abuse and seeking, is ‘all about’ me now. Like surrounding me. And it’s more dispersed. If you know what parts of southern California are like, it rolls, it sprawls, has little nuclei all around, is less in a major key. Writing like that demands more of the reader. Asking more of the reader is not something I’m proud of, it just sort of turned out that way. It’s both more and less sober. Like a fog, if you walk around in it long enough, you’ll get wet, and I hope that is a pleasing if somewhat less crystalline experience.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In fact, I didn’t come to poetry first, at least not officially. I was in a short-fiction writing class in S.E.E.D. high school, and wrote a few short stories during that time. I’d get high at home and write surrealist poems, but it wasn’t till I got into a creative writing class taught by a poet (again, Luciano Iacobelli) that I was steered toward reading and writing poetry. Once I made the shift, felt the freedom and potential, it was for good.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The main body of any poem usually comes quickly, in one sitting, and sometimes appears looking close to its final shape, but usually undergoes copious edits. Getting the first draft on the screen is the first gate, and a kind of seal reopened by editing. Then it either floats and becomes more efficient and streamlined or falls away.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don’t really know where a poem usually begins, maybe an impression, a feeling, a word with something unknown behind it, something, as Eliot wrote, to be exorcised. I’m never really working on a book. I write poems. I then try to find siblings. Sometimes just appearing during the same time under the same concern is enough to group them together. This is a question of affinity and not laziness, I hope.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing public readings. The poem isn’t finally birthed until I’ve read it out loud to an audience. I’m with Mandelstam on that. That said, they live on after ectopic birth on the page.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think poetry as any art can address fundamental questions about being alive…what it is like, where it comes from and how it can change. So I think ‘where did it come from?’, ‘where is it going?’ and ‘what is it like along the way (and what can be done to REALIZE it)?’ are the perennial questions. I’m speaking of a relationship to others and the universe.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

If you look at history, it’s a bit of a death cult. Some writers and artists receive recognition in their lifetime, but others are shrouded in obscurity. I think especially now, when identity politics dominates what is curated by mainstream culture, much that is good will be seen as such only later, at least canonically. There’s that very neat phrasing about recognition…which I will butcher, but goes something along the lines of ‘first it is mocked, then it is murdered, then some time later it is considered self-evidently true. ‘ (I think that was about prophetic words and prophets, but it goes for art as well.) I think the role of the writer today is to remind us to be good by sedulous or apocryphal means, and that might be true for other times as well.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s essential. The editor needs to match the writer in dedication, even push them along.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

In Zen we go slowly.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t really have a writing routine, I bear the marks of the outdated romantic notion that it’s ‘just as the spirit takes you’. My days begin with Chinese herbs, Clif bars and an AA meeting, unless I’m on retreat, in which case only the Chinese herbs survive, and meditation takes the place of meeting.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I don’t feel like writing I just don’t write. I do other things. It is all a continuum anyway.

It all comes home.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Rainwater on a rose. Reminds me of here, which is home. And the smell of a pillow that needs washing.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above influence my work. To some degree I practice ‘found art’ or collage, even though my poems are usually narrative, some of them consist of things found here and there bound together by my own zeitgeist.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Zen literature. Ikkyu, hence the epigraphs in my new book. Rinzai, Dogen, Hakuin, Bassui, Ta Hui, Lao Tzu. The Heart Sutra. Cold Mountain. The Diamond Sutra. Joko Beck. And in poetry, Rumi. Kahlil Gibran. T.S. Eliot. Eugenio Montale. Nanao Sakaki. Bukowski. Al Purdy.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Surf.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A monk.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Besides writing and doing zazen, the only other thing I know how to do is wash dishes. Actually, I’m usually on the look-out for a good dishwashing job. It goes well with writing. I have a BA, and had things turned out differently with my state of mental health, I might have gone into teaching creative writing or language or Asian Studies. The monk thing still stands, and it is, unlike the other things listed, still probable.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Preparation for the Next Life by Atticus Lish, though I couldn’t finish it because of the sexual violence. So for one that I finished, Convenience Store Woman, by Suyaka Murata. As for film, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus or the 2010 film Alice in Wonderlandstarring Mia Wasikowska.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m editing a few long poems. They are about the reckoning of failed love. I want there to be more short pieces that are easily digestible to accompany these long poems, and I want to do the lion’s share of the work, so that the reader or listener just has to take it in without too much parsing. So maybe it’s not entirely true that I never have a book in mind. I guess I write and ride the waves until there’s some kind of consistency.

December 29, 2022

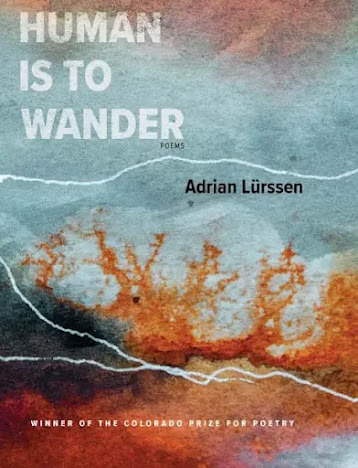

Adrian Lürssen, Human Is to Wander

Between I andyou comes

a sounding out against

picture frames, chanting in exchange

for landscape. She spoke

as if underwater: Here

is a map. Here, a spoonful

of honey. Lying in wait,

the curious air of a genie

unhindered by voice,

she was indifferent

as smoke and driftwood. (“NO LONGER A MOTHER TONGUE”)

Born and raised in apartheid-era South Africa and then Washington D.C., San Francisco Bay Area-based poet Adrian Lürssen’s full-length debut is the poetry collection

Human Is to Wander

(The Center for Literary Publishing, 2022), as selected by Gillian Conoley for the 2022 Colorado Poetry Prize. As I wrote of his chapbook earlier this year, NEOWISE (Victoria BC: Trainwreck Press, 2022), a title that existed as an excerpt of this eventual full-length collection, Lürssen’s poems and poem-fragments float through and across images, linking and collaging boundaries, scraps and seemingly-found materials. Composed via the fractal and fragment, the structure of Human Is to Wander sits, as did the chapbook-excerpt, as a swirling of a fractured lyric around a central core. “in which on / their heads,” he writes, to open the sequence “THE LIGHT IS NOT THE USUAL LIGHT,” “women carried water / and mountains // brought the sky / full circle [.]”

Born and raised in apartheid-era South Africa and then Washington D.C., San Francisco Bay Area-based poet Adrian Lürssen’s full-length debut is the poetry collection

Human Is to Wander

(The Center for Literary Publishing, 2022), as selected by Gillian Conoley for the 2022 Colorado Poetry Prize. As I wrote of his chapbook earlier this year, NEOWISE (Victoria BC: Trainwreck Press, 2022), a title that existed as an excerpt of this eventual full-length collection, Lürssen’s poems and poem-fragments float through and across images, linking and collaging boundaries, scraps and seemingly-found materials. Composed via the fractal and fragment, the structure of Human Is to Wander sits, as did the chapbook-excerpt, as a swirling of a fractured lyric around a central core. “in which on / their heads,” he writes, to open the sequence “THE LIGHT IS NOT THE USUAL LIGHT,” “women carried water / and mountains // brought the sky / full circle [.]” The book is structured as an extended, book-length line on migration and geopolitics, of shifting geographies and global awareness and globalization. He writes of war and its effects, child soldiers and the dangers and downside of establishing boundaries, from nations to the idea of home; offering the tragedies of which to exclude, and to separate. “The accidental response of any movement,” he writes, to open the poem “ARMY,” “using yelling instead of creases as a / means to exit. Or the outskirts of an enemy camp.” Set in three lyric sections, Lürssen’s mapmaking examines how language, through moving in and beyond specifics, allows for a greater specificity; his language forms akin to Celan, able to alight onto and illuminate dark paths without having to describe each moment. “A system of killing that is irrational or rational,” he writes, to open the poem “SKIRT,” “depending on the training.” As the same poem concludes, later on: “It is a game of answers, this type of love.” Lürssen’s lyrics move in and out of childhood play and war zones, child soldiers and conflations of song and singer, terror and territory, irrational moves and multiple levels of how one employs survival. This is a powerful collection, and there are complexities swirling through these poems that reward multiple readings, and an essential music enough to carry any heart across an unbearable distance. “The enemy becomes a song,” the poem “UNIT” ends, “held by time.”

December 28, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Shane Kowalski

Shane Kowalski

lives in Pennsylvania. He works for the United States Postal Service. He is the author of

Small Moods

(Future Tense Books).

Shane Kowalski

lives in Pennsylvania. He works for the United States Postal Service. He is the author of

Small Moods

(Future Tense Books). 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Not much has changed. I continue to work, continue to write. Of course, knowing I have a book out there in the world is a strange thought I remember from time to time and it does give me pleasure knowing there are people out there reading my weird, little stories. It's a surreal kind of space that I like to exist in.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Weirdly, I actually came to poetry first. In my undergrad years there was so much poetry being taught where I went to school, it just seemed like a good idea to write. Always, though, with an eye towards fiction in the back of my mind. A lot of those poems that I wrote were very prose-ish.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I actually cannot quite say. It's all very moody. Some pieces come really quick, others it's a more protracted process. I do a lot of drafting as I write, so the revision process is streamlined. It's rare that the final shape doesn't closely resemble most of what I started with.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I'm definitely a writer of short pieces that end up having to find a home. I always start with a small thing in a prose piece—an image, a phrase, but more times than not, it's a first sentence. What happens from there is the story.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing readings, weirdly. They end up being fun. Even though I don't quite look forward to them.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don't think I have any theoretical concerns. I just like doing voices.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have no clue, really. I always like taking a workmanlike approach to these types of questions. Simply: Use the language—Tell good stories. People will take it from there.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it's a cool process. Working with a really good editor is like putting on a pair of glasses and seeing your work more clearly.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I remember J. Robert Lennon saying, "Your novel is perfect until you write the first line, and then it is forever ruined."

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I usually try to write and post a very short story to my tumblr every day. My single writing habit I've sustained since 2011. Everything else has just been a mood or passing fancy.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I usually go back to the previous sentence. What's going on in it? What can I use? It is usually giving a direction forward.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

It's a fragrance I couldn't describe unless I was dreaming.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Absolutely. Music, paintings, movies, television—they all have at one point or another influenced my work.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Lydia Davis, Robert Walser, Jane Bowles, Chelsey Minnis, Jamaica Kincaid just to name a few.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write 10 novels in one year.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Probably some kind of mundane work you could disappear into. Custodian. Librarian. Postal worker. Butler. Who knows...

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was too much fun.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently finally read Kazuo Ishiguro's The Remains of the Day, which is a masterwork. I didn't think it could live up to the hype, but it is one of the finest examples of human storytelling. They should send it out into space. I also recently watched for the first time Ingmar Bergman's Cries and Whispers, which was beautiful and quietly harrowing.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Oh, a bunch of things. So many short fragments of pieces. A novella-length piece that I've been tinkering with for a few years now about a woman who is a peeping tom. I'm just surrounded by tiny, little pieces of work. Who knows where they'll lead—if to anything at all?

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 27, 2022

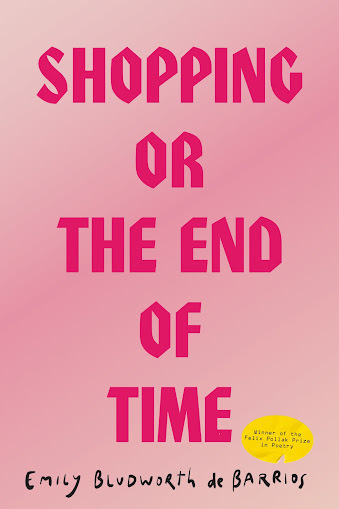

Emily Bludworth de Barrios, Shopping, or The End of Time

80 to 90 percent of my awareness

Is a delicate ear turned gently toward my son

Which means I ignore

What would have previously torn me asunder

You may imagine motherhood as a funnel of sand

Into which one is pulled

You may imagine a wrecked ship pulling the inhabitants down with her

Into the water

Except for this metaphor

You are willingly rinsing yourself in sand or heavy water

It is an ecstasy of familial love

Among the sand and water (“80 TO 90 PERCENT OF MY AWARENESS”)

The latest from poet Emily Bludworth de Barrios is the poetry collection Shopping, or The End of Time (Madison WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2022), a collection that works through the lyric of narrative monologue to examine personal space and interpersonal being, including new motherhood and ongoing parenting, as well as simply living as a human being in the world, with all the messy nonsense and possible beauty that goes along with existence. “With pleasure the young men,” she writes, to open the poem “WITH PLEASURE THE YOUNG MEN,” “dismantle the young women // With pleasure their sick slick grins drip over the wet idea // of humiliated flesh [.]” Raised in Houston, Cairo and Caracas and currently based in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, Bludworth de Barrios is the author of the full-length debut Splendor (H_NGM_N Books, 2015), as well as the chapbooks Extraordinary Power (Factory Hollow Press, 2014) and Women, Money, Children, Ghosts (Sixth Finch, 2016). Shopping, or The End of Time, her second full-length collection, is set, within an opening as well as closing poem, into four sections of narrative lyrics—“WOMEN,” “MONEY,” “CHILDREN” and “GHOSTS”—all of which are individually constructed as assemblages of short phrases and bursts; her narratives are less built as accumulations than as a cadence of narrative waves, rolling through rise and fall to either a final crescent, or a sweep up to the shore of the space beyond that final word.

My new blue kitchen cabinets painted blue

Black countertops, black granite flecked with dirty starlight

And Saltillo tile from Saltillo, Mexico, baked, glazed earth and still some little

imprints from the foot of a dog who passed probably 50 years ago

When the Earth had fewer dogs probably but more species, fewer people, but

more thick forest, more dark trees and the webs strung between the trees,

clumps of sticks pushed into nests with the vulnerable blue, white, or cream

eggs inside, speckled, warm, the squirrels’ nests that contain two entrances

that are also two exists, a burrow in the sky, warm and dry

A bird singing with its narrow throat, its voice a slender stem

The legs of the insects slander as stems

The stems numerous and dense moving in quick ticks

My thoughts numerous and dense

Thickly sprouting, dumb (“MY NEW BLUE KITCHEN CABINETS PAINTED BLUE”)

Throughout her poems, Bludworth de Barrios seems fond of the direct statement, whether set as a point from which her narrative can expand further, a counterpoint or even a side-step, depending, of course, on where the statement is set in those narrative waves of rise and fall, rise and fall. “To be a mother,” she writes, as part of the two-page poem “80 TO 90 PERCENT OF MY AWARENESS,” “Is to be a figure in a painting // Wrapped in a sacred blanket [.]” Later on in the collection, the poem “STATUES OR KNOTTED ROPES OR SCORED STONE” offers a slight variation, or even a continuation: “A person is a device / For storing information across time // The parent melts or dissolves / And up springs the child // A person // Is a phenomenal device / That assembles itself from dirt and air [.]”

Throughout her poems, Bludworth de Barrios seems fond of the direct statement, whether set as a point from which her narrative can expand further, a counterpoint or even a side-step, depending, of course, on where the statement is set in those narrative waves of rise and fall, rise and fall. “To be a mother,” she writes, as part of the two-page poem “80 TO 90 PERCENT OF MY AWARENESS,” “Is to be a figure in a painting // Wrapped in a sacred blanket [.]” Later on in the collection, the poem “STATUES OR KNOTTED ROPES OR SCORED STONE” offers a slight variation, or even a continuation: “A person is a device / For storing information across time // The parent melts or dissolves / And up springs the child // A person // Is a phenomenal device / That assembles itself from dirt and air [.]” In certain ways, this is very much a collection writing and exploring the trauma and beauty both large scale and small of parenting, children and interacting with and through the culture, the present, each other and the universe. It would be interesting to examine the ways through which her direct statements on self and being connect, and even conflict, to each other; evolving in the normal ways of human complication: we are never simply one thing, in one way or direction; often working multiple simultaneously. Note the poem, for example, “MY PREGNANCY WAS A LONG AND HAPPY NIGHTMARE,” a three-page extended lyric that opens: “My pregnancy / Was a long and happy nightmare // During which I ate / Pint-sized tubs of ice cream and walked around the block // Becoming more tubby and unwieldly / As if living in the skin of a drum // Wielding and propelling my belly / Feeling dreamy and druggy in the suburbs under the sun [.]” There is a swell and swoop of her narrative, but also a subtle music across that same lyric that itself fills and diminishes across such a lovely spectrum of her lines. One is nearly required to close one’s eyes to truly listen.

December 26, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jessica Gigot

Jessica Gigot

is a poet, farmer, and writing coach. Her second book of poems,

Feeding Hour

, was a finalist for the 2021 Washington State Book Award. Jessica’s writing and reviews appear in several publications such as The New York Times, The Seattle Times, Orion, Terrain.org, and Poetry Northwest. Her first memoir

A Little Bit of Land

was published by Oregon State University Press in 2022.

Jessica Gigot

is a poet, farmer, and writing coach. Her second book of poems,

Feeding Hour

, was a finalist for the 2021 Washington State Book Award. Jessica’s writing and reviews appear in several publications such as The New York Times, The Seattle Times, Orion, Terrain.org, and Poetry Northwest. Her first memoir

A Little Bit of Land

was published by Oregon State University Press in 2022. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first two books, Flood Patterns and Feeding Hour, are both poetry. My current book, A Little Bit of Land, started as a few poems I could never finish. They begged to be essays, so I finally decided to try to write something longer. That work eventually became a memoir after many years of experimenting. While I still consider myself a poet, primarily, I appreciate memoir as a genre. People relate to storytelling, so I feel like this book has expanded my readership and is in conversation with other books about land, place, and home.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was younger I loved rhyming and form and poets like Ogden Nash, Emily Dickinson, and Robert Frost were very inspiriting to me. I am also a song writer, so I appreciate short forms in general. I love the associative nature of poetry and its potential for discovery.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I joke sometimes that alternate titles to my poetry books could be “Poems Written Between 2010-2014,” etc. My poetry is autobiographical and so far has been born out of distinct time periods in my life. Some poems are almost direct downloads from an idea or specific incident, while I have several poems that have been worked and reworked with feedback from other writers. Once I have amassed seventy or so poems, I start to think about putting them together as a book and it has been really interesting to see how various themes emerge and how various poems speak to each other.

I recently started a second memoir and that has a heavy research component. My first memoir as well started as various essays and it took me a long time to arrange them and find a form that felt true to the story. I have a novel as well that is in a very early form. Both fiction and non-fiction take me a long time and are a seven to ten year process, generally.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The origins of my creative work varies widely. I just had a writing moment where I realized that eleven “poem ideas” were actually all one poem and that was very exciting and somewhat shocking, to be completely honest. For both of my memoirs, and the new novel project, I definitely start with a linear mindset, however that can change with progress. As an example, with A Little Bit of Land, I found myself playing with time and towards the end of that writing process I jumped around quite a bit. Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design Patterns in Narrative by Jane Alison has been very helpful and liberating for me.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. When Flood Patterns came out I had a new baby as well so I didn’t get to do a lot of readings for that book. Feeding Hour came out in the pandemic and all my readings for that book were online. This was convenient in some ways and I was able to read and collaborate with authors outside of the northwest. For A Little Bit of Land I ended up doing all in-person readings this fall and it has been an amazing experience, reconnecting with old friends and colleagues and also being in beautiful bookstores again. I definitely have not gotten a lot of new writing done during this fall, but now that things have quieted down I have some new pieces to sit down and finish and I hope to get back to a regular writing practice in January. I have learned that book promotion and generative writing do not work together well for me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I explore relationships between managed and natural ecosystems through my work. Food, at the confluence of science and art, is of particular interest to me. In my poetry and creative non-fiction, I am informed by my experiences in agriculture and the complexities of the landscape around me.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Farming, like writing, are undervalued vocations in modern life. However, I think that both roles have tremendous value. I wish we had more resources available to let writers be writers and to let farmers farm.Many writing friends are juggling other work and, in some cases, parenting and they fit writing in on the side.

Writers help us process our world and make meaning of it. They also entertain and illuminate ideas/issues that we need to consider.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love feedback, so I appreciate working with an editor. For all of my books I had a fantastic editing experience. I am grateful for all of the journal editors that have offered feedback on my individual pieces. I have only had one bad experience with an editor and it was largely because that person seemed short on time and patience and they were preoccupied with a new book coming out.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Show up for the work and it will show up for you.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to memoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

It has been a rough transition. It took a lot out of me to write my memoir, which by comparison is a shorter book than creative non-fiction works. I love reading memoirs, especially those written by poets, because they pay attention to line-level details and there is a certain precision and succinctness in those books that I appreciate. I am actually teaching a class about this next year: https://hugohouse.org/product/cross-pollination-poets-writing-memoir/

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My youngest daughter just started Kindergarten and my oldest is in Second Grade, so we are in a new chapter. I have other work that I do, but I am trying to schedule specific mornings for writing and also various days when I can meet with my writing group and dedicate blocks of time to editing and developing specific writing projects.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I love music, so listening to good songwriting is helpful to me when I am feeling stuck. I do ceramics and knitting as hobbies and that work with my hands helps to take me out of my head. In the Skagit Valley, where I live, there is an active visual arts community and I love being in conversation with the many painters, printmakers, and sculptors here.

Most times, taking a walk really helps. Either a stroll around the farm or down to the river is a great way for me to wake up a bit and find new inspiration. In the pandemic I learned how to play tennis, too, and that has been a great outlet for me, both physically and mentally. I considered myself an athlete when I was younger and reconnecting with that part of myself post-pregnancies has added a new sense of vibrancy to my life and writing. Andre Agassi’s Open is one of my favorite books!

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Hay and wool!

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

See #12

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass came out as I was writing my memoir and that had a deep effect on me. A Little Bit of Land is a conversation with Wendell Berry’s The Unsettling of America which was published the year I was born. These days, I am trying to read more fiction. I am loving Jenny Offill, Claire Vaye Watkins, and Kevin Wilson right now and I just started The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? 18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

This is all one question in my mind. I am a naturally curious person, so I have already explored a lot of activities in my life and worn a lot of hats, from cheesemaker to wedding singer to mom. I feel pretty content at this point and am in a phase of letting go of things so that I have more time to focus on writing. Personal growth is an underpinning of writing for me and one of my favorite responsibilities as a teacher was the one-on-one mentorship relationships I had with students. Recently, I opened a coaching practice which focuses on manuscript coaching, but also helps people recultivate a sense of wonder and place. It is easy to get bogged down in daily life and responsibilities, especially as we enter midlife, and as a creative person I am actively trying to stay open to new ideas and possibility. To answer your questions, I may have been a psychologist or naturopathic doctor had I not been a writer. The art of healing fascinates me and is at the heart of memoir and poetry in many ways. I am a creator and after years of searching realized that writing was what made me feel whole and complete versus other professions. https://www.ecointegralcoach.com/

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

E.J. Koh’s The Magical Language of Others is a masterpiece.

To be honest, this time of year I binge on holidays movies. It’s like a cleanse of sorts—they are so bad they are good. I am watching more TV than anything else, since there are so many great options out there. King Richard was a great movie, because the story of the Williams’ sisters is so phenomenal. The White Lotus is a hilarious and full of complicated characters.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I have a third poetry manuscript in the works, As Long As You Need Holding, that is focused on ecological grief and I hope to edit and submit that next year to various small presses. I am starting a second research-heavy memoir that is about reinhabiting the body after childbirth and the ecological challenges facing migratory Trumpeter and Bewick swans in the United States and UK.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 25, 2022

happy seasonal things, christmas + greetings,

From all of us to all of you: whatever it is you celebrate, if at all, I hope it is merry, healthy and all other good things. We can only improve from here, I think.

Photo credit: Elizabeth Fulton Photography.

December 24, 2022

from A river runs through it: a writing diary

, collaborating with Julie Carr

As part of my recent substack

, I’ve started posting (among other things) sections of this particular and lengthy essay-in-fragments, and thought it would be worth including a section here as well, to catch your attention. The essay is some forty-ish manuscript pages, and is currently out at a potential publisher for consideration. It reads real nice as a whole unit. Hopefully these fragment-sections read well also.

As part of my recent substack

, I’ve started posting (among other things) sections of this particular and lengthy essay-in-fragments, and thought it would be worth including a section here as well, to catch your attention. The essay is some forty-ish manuscript pages, and is currently out at a potential publisher for consideration. It reads real nice as a whole unit. Hopefully these fragment-sections read well also.

* * * * * *

On November 26, Julie emails an extended version of her “River,” writing: “It’s US thanksgiving - Already making pies.” Our thanksgiving, of course, sat a month earlier. We have American President Abraham Lincoln to thank for the original holiday, crafting a bit of sentimental acknowledgment and historic inaccuracy from Of Plymouth Plantation, the memoir/journal composed by Yorkshire-born Puritan William Bradford (1590-1657), founder of the Plymouth Colony after landing via the Mayflower. Bradford was known neither for his pies, nor for his easy relationships with the aboriginal peoples. He barely made it out alive, his soul far less intact than he himself might have hoped. Or even wished to admit.

She adds a half-page further to her original poem, shifting where I thought this might go. I had presumed, somehow, that her second “response” would be another stand-alone section, roughly the length of the first she’d sent along. The new sections include:

I give over to you. or could.

and then the phone alarms : a photo of a little girl in orange who is ours:

for we, they, she is legion, feathery and promiscuous and

*

light. I woke to the snow how it paints

the top sides of sturdy limbs

and draws the soft boughs down

wanting to fall

toward the something that is new.

Where does her river flow? I spend a day shaping, reshaping my own response. My “estuaries : two” includes:

these small mercies , nest

and shelter,

our two girls on their tablets,

a morning of personalized moments,

wrinkled pajamas,

a paint

of seawater, fresh I woke

to the snow,

*

sunroom: pressurized bursts

of carbonated cans of ice,

three season space: , a snowy

bricolage

of flavoured slush,

I’ve always favoured writing that exudes breath; writing that moves through the lyric with the understanding that language includes both music and breath. Akin to a flow of water, perhaps. One should spend a certain amount of time learning to listen to the water.

To state what might seem obvious: poems are constructed out of words, of language; before subject, tone or biographical elements. Before sentences, or any potential narrative or story. Writing is built out of words, and the words themselves, an evolution of agreed-upon sound and meaning. These are the block with which we build our houses. The houses in which we build, and choose to live.

To paraphrase Meredith Quartermain: “What the language poets miss is that words can’t help but mean.” The material of language and the elements of domestic, reference and collage.

Nepal and China have just announced that Mount Everest is taller than it used to be. How might I be able to use that in a poem?