Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 98

February 22, 2023

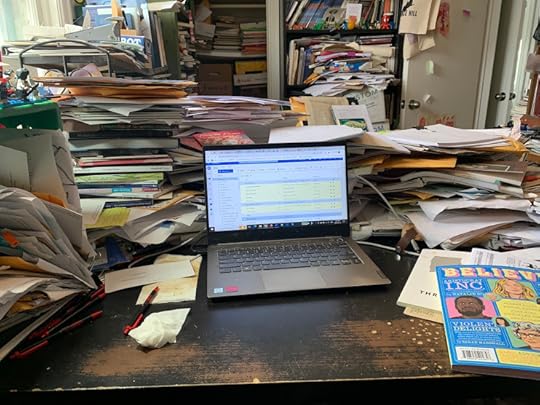

the state of my desk :

The stacks upon my desk are perpetual, with layerings of books, chapbooks, journals, unread newspapers, manuscript pages, correspondence and other ephemeral literary sediment across weeks, months and even years, depending on how far down one might attempt to excavate.

The desk itself is handed-down, inherited from Christine’s brother Michael when we took over his apartment on McLeod Street, back in 2011. I had an office that sat above a maple that turned orange and red in the autumn, a neighbour’s backyard skating rink for an array of grandchildren. Two years later, we transported the desk and all else here to Alta Vista, where it has remained. It is strange to think of this as only my third writing desk across fifty-some years. This replaced a 1980s particleboard IKEA structure that my parents picked up during my high school days, a desk scuffed and loosened with every move across a variety of Ottawa neighbourhoods and living situations, from the original homestead to Ottawa’s Heron Road and Flora Street, Pretoria Avenue to Fifth Avenue, Rochester Street to Somerset Street West. By the end, the desk was barely holding together, and Michael’s offer was as good a reason as any to let it, finally, go. Upon leaving my eleven years of terrible one-room apartment along that stretch of street-level Chinatown, that old desk was one of a number of items dismantled, pulled apart and left at the curb. Where any of it ended up next became a story for someone else.

My original desk, of course, handmade and handpainted white by my father, a desk with Mickey Mouse stickers on either side, gifted around the time I was five. The desk sat in the upstairs hall of the farmhouse, by the north-facing window. I remember preschool afternoons watching the rain as I sat and worked on my colouring, or flipped through my Dr. Seuss volumes, gifted from one of my grandmothers as a monthly subscription. The books sat on the desk, along with crayons and coloured paper. I suspect the desk was eventually inherited by my younger sister, although I have no further recollection of it. I haven’t even a photograph.

This current desk, now a dozen years benenth my fingertips, is entirely straightforward: black wood and solid with three sides, no drawer. I’ve slipped smaller shelving beneath for files, outgoing correspondence, comic books and other items to be close-at-hand. A plastic milk crate on its side to my left, to hold letters, postcards, scraps and other detritus. My lamp and Lego figures atop, along with a cow-shaped Holstein award retrieved from the top of my father’s desk as we dismantled the house, an award presented him in 1954, most likely as part of his 4-H club membership. A stack of trade comics underneath to the right, just by a tin garbage can I’ve had since before I can recall, set in my homestead bedroom before I landed, thus becoming one of my touchstones. It is strange, the things we decide to carry with us as we go. Sometimes we get to choose, and other times, less so.

I can’t remember the last time I cleared off this particular desk, although I might have attempted a fraction of such last year, when the new printer landed. It took a whole day, and the box of books set aside still sits where it lay. Papers and manuscripts and books and journals and chapbooks replenish like lichen, or morning glory. I marvel at the outcrop. I hack at the runners.

February 21, 2023

Milton Acorn and bill bissett, I Want to Tell You Love, A Critical Edition, eds. Eric Schmaltz and Christopher Doody

This introduction will acquaint readers with I Want to Tell You Love along with the places, figures, and ideas that were central to the creation of the book. It begins by providing an overview of the tradition and milieu within which Acorn and bissett were writing in the 1960s. It then moves on to chronicle the convergence of events that let to their meeting in Vancouver. Next, it provides a detailed textual history of I Want to Tell You Love’s creation and its subsequent history of dismissal. Penultimately, it advances a short treatise that underscores the book’s significance and its contributions to the discourse of Canadian Literature and the history of avant-garde writing. It concludes with a few points regarding bissett’s and Acorn’s careers and friendship after their time in Vancouver. Despite their aesthetic differences, bissett and Acorn both hold a fundamental belief in poetry’s transformative capacities for stimulating social change. This edition fosters greater attention to I Want to Tell You Love as a significant meeting of discordant voices, but more importantly as a significant record of Canadian avant-garde activity that engages with, and documents, the frenzy and exhilaration of the 1960s in Canada. (Eric Schmaltz, “Critical Introduction”)

Admittedly, I wasn’t sure what to expect upon first hearing of I Want to Tell You Love, A Critical Edition, eds. Eric Schmaltz and Christopher Doody (Calgary AB: University of Calgary Press, 2021), the previously-unpublished early 1960s collaborative work done by two of Canada’s more important poets to emerge out of the social, political and cultural mimeo-propelled burst of 1960s literary production: Milton Acorn (1923-1986) and bill bissett (b. 1939). On the surface, the two writers couldn’t be any more different, whether through their personalities or how their work sits on the page, but both this project and Schmaltz’s incredible introduction provide a wealth of argument for how the two connect, as well as their overt interest in engaging exactly with those differences. Acorn had already produced a book or two by the time the two poets met up in Vancouver, but it is curious to consider, that had this book-length collaboration actually been accepted by the publishers of the day, it would have pre-dated bissett’s two 1966 solo collections. According to Schmaltz, the main argument for the array of rejection this collection managed was exactly the strength of this collaboration, as potential publishers misunderstood that this is not simply a work by two wildly different poets, but a conversation around where their work actually meet, allowing their work (including bissett’s drawings) to connect into and around each other.

Of the universe, one spirit

should be held up, to the many

stars we know shine within

ourselves.

One love can be known

all loves pay homage to.

The rose, the sea, white or deep,

the colors are many and one

in resolve; the fire, demons, past

for an angel, all human

in spirit. You can speak beauty

of any flower.

Young girls, rose

again, and boys play summer evening

games outside. And they are inside, the

walls are that artificial, useful

to believe in. (bill bisssett, “Crossing Directions”)

As well, it has been a joy to see a small handful of critics over the past few years—I’m thinking not just of Schmaltz, but of British poet/critic Tim Atkins, who offered an incredible piece on bissett’s early influences at the 2018 Kanada Koncrete: Material Poetries in the Digital Age conference at the University of Ottawa [see my notes around such here], as well as a foreword to bissett’s 2019 selected with Talonbooks, breth : th treez uv lunaria: selektid rare n nu pomes n drawings, 1957–2019—have finally been starting to provide bill bissett some proper critical acknowledgment and assessment, all of which is wildly overdue, especially when one considers that bissett is still producing, touring and publishing.

As well, it has been a joy to see a small handful of critics over the past few years—I’m thinking not just of Schmaltz, but of British poet/critic Tim Atkins, who offered an incredible piece on bissett’s early influences at the 2018 Kanada Koncrete: Material Poetries in the Digital Age conference at the University of Ottawa [see my notes around such here], as well as a foreword to bissett’s 2019 selected with Talonbooks, breth : th treez uv lunaria: selektid rare n nu pomes n drawings, 1957–2019—have finally been starting to provide bill bissett some proper critical acknowledgment and assessment, all of which is wildly overdue, especially when one considers that bissett is still producing, touring and publishing. I Want to Tell You Love, A Critical Edition is a remarkable edition, and in certain ways, for reasons far larger than the presentation of this particular collaboration, offering context on and around a specific and hugely engaged period of Canadian writing, politics and culture. Through his remarkably thorough sixty-page critical introduction, Schmaltz examines the political and social landscape that opened up different ideas of culture that led to this particular moment, from the post-war period and the emergence of hippy culture to the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts, circling in on Canadian literature and into British Columbia politics, all before landing on how these two vastly different poets from Canada’s East Coast ended up in Vancouver, and what they did once they landed. Schmaltz writes of the centres of Canadian literature during that period, and how both poets, however active, still existed well on the fringes (even in the context of perpetual-fringe Vancouver), well before the creation of such an oddball collection, which neither could get anyone interested in (apparently each pulled poems from the work to land in their own future solo collections). With the inclusion, as well, of an afterword by and a contemporary interview with bill bissett, this might just be a must-have edition, not only for the purposes of a broader comprehension of Acorn and bissett’s individual careers, but of the hefty examination of the emergence of a particular period of Canadian writing and culture.

Untitled by Milton Acorn

Lover that I hope you are … Do you need me?

For the vessel I am is like of a rare crystal

that must be full to will any giving. Only

such a choice at the same time is acceptance,

as it is a demand high and arrogant.

Christ! I talk about love like a manoeuver of

armored knights, with drums and banners!

Is it for you whose least whisper against my skin

can twang me like a guitar-string? for

myself? or for something stronger than the saw

that cuts diamonds, yet is only a thought of perfection?

And this is not guarantee, only a promise

made by one who can’t judge either his weakness

or his strength … but must throw them

like dice, one who never intended to play

for small stakes, but once having made the second greatest gamble

and lost, lives for the next total throw.

February 20, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brody Parrish Craig

Brody Parrish Craig is the author of the chapbook

Boyish

(Omnidawn 2021) and edited

TWANG

, a regional anthology of TGNC+ creators in the south/midwest. Their first book, The Patient is an Unreliable Historian, is forthcoming from Omnidawn Publishing in 2024. More on their work can be found at brodyparrishcraig.com.

Brody Parrish Craig is the author of the chapbook

Boyish

(Omnidawn 2021) and edited

TWANG

, a regional anthology of TGNC+ creators in the south/midwest. Their first book, The Patient is an Unreliable Historian, is forthcoming from Omnidawn Publishing in 2024. More on their work can be found at brodyparrishcraig.com. 1 - How did your first chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When I was writing Boyish, I rarely thought about audience/publishing. Like sure, in my MFA I was told it’s something you do, but I never really thought about how it would land or expected it to happen for me quite honestly. I was just writing what I needed to get out there & letting it take whatever shape it needed to take—I think the biggest joy I got out of it being put into the world was getting those poems into the hands of other TLGBQ+ folks like me who needed those poems, and the biggest growth came from the simultaneous shock of what it’s like to let such a personal work live on its own in the world…I see publishing Boyish as a book-end in my own path as a person--not just in the writing sense, but the sense of letting something go. Usually my writing is whatever I’m chasing down, whatever questions I personally need answers for or my own way of reckoning. The questions I’m stuck on now are much different, but the process feels iterative in that way—I’ve written my way out of this, so what’s next on my heart and mind? This next book I just finished wrapping up deals a lot with disability & abolition. Even though some poems in Boyish talked about madness and that aspect of my experience, I wasn’t quite ready to write through my experience with disability until recently. In this next book, the dam has broken, and the poems go deeper in that sense…Writing tends to pull the truth right out of me, over time.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve always loved writing—in many genres. So it’s not so much that I’d say that I came to poetry first, as it is I stayed because I love the emphasis on language. I feel like poetry gives a density of sound & play that is harder to hone in prose. I also like the associative nature of poetry, and how that’s heightened in a way that’s not as common for me when I’m going to write an essay. I can create my own realm of connotation or specificity, versus trying to work with the language constraints that are given to me in the borrowed form of definitive prose. When I write a poem, I access an altered state, and none of the conventional rules of communication matter. I think poetry is uniquely suited for invoking experiences of madness. I think it’s the one form of writing for me where I don’t have to mask what I mean.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m not sure I start with a project in mind, as much as the project finds me. When it comes to an individual poem, I usually write from a place of the subconscious & then find where the poem is. From there, the process could take days, weeks, or years, before I decide where it’s hitting. My first drafts are fast, the revision slow. I think longer projects come out of obsession—what I’m thinking on, what shows up over time, and then I intentionally lean into that direction once it appears to me.

4 - Where does a work of prose or a play usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Prose usually starts with a concept for me. I’ve been writing more essays lately, and usually I have a thought out plan of what I want to communicate and write my way into it. I have a slow-going essay collection in my head right now, and I’d say I know what it is even though only a few essays are written. Prose comes the opposite as poems to me—I think first, write later. With poetry, I usually write first, and figure out what I’m doing later on.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love going to readings, and sometimes being a part of readings, but more than anything it’s the community component I’m drawn to more than the actual performing—most of my favorite readings I attend are the ones I’m slumping against a wall listening to others, and chatting with folks between. I feel the same about art events in general—my favorite times I’ve read usually there’s another artistic discipline involved, whether it’s visual art or music. One of the favorite times I’ve read a poem to a crowd was at the Arkansas Capitol—it was part of a rally for trans rights, and we did a call/response with the crowd…I think reading poetry in places that aren’t just about poetry is where it’s at for me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Disruption, questioning the status quo, and especially questioning the power structures as they are and how they show up in our language/syntax…My goal is often to upheave or challenge the reader, not to create a place of comfortability.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think that poetry is uniquely situated to interrogate how power shows up in our language. The English language preserves so many fucked up stories of our culture and history, from pithy sayings we take for granted to the etymology of a single word, and I think the poet can challenge or disrupt those spaces/narratives if they choose. Ultimately, I think the poet can be a conduit for conversation in the world and political education/consciousness building. I go to books looking for conscious dialogue, and all writing is political for me. It’s a matter of who is choosing to disrupt or disengage.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it depends! On how well they see the work. Working with Rusty/Omnidawn was lovely, but I’ve also been in situations where I’ve felt that we were speaking in two different worlds, and it’s hard to walk the tightrope in those moments so to speak.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Do the next right thing for the right reason.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try to write as often as I can. Sometimes life gets in the way. But when I’m able, the best writing habits mean I’m churning out new poems several times a week. Otherwise, my brain feels clogged, and there’s this like backlog that causes my day-to-day to suffer until I put it out on the page again.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A professor in grad school told us when we get stuck write a sonnet as fast as we can. I thought he was crazy for it, but now it’s been half a decade & it’s still my go-to method. Oddly, prosody?!

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Swamp water.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music especially. I learned a lot about sound & musicality in poems by studying song lyrics. A friend once even tried to teach me how to battle rap, and I’m not saying I was any good, but I am saying that learning how to write a rap verse entirely changed my understanding of rhythm.

I haven’t tried to translate in quite some time, and I honestly doubt I could now, but working in translation & studying other languages completely changed how I see writing as well.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Diane di Prima & the tao te ching.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to blend my poetry with visual art! I’ve been really tempted to get into printmaking, but so far haven’t found the time.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

There was a time I thought I’d get into policy/law. I was a debate nerd as a child. I don’t think that’d be my route today, but I do think nonprofit work or social justice work is important to me. I could see myself diving into a justice org if I wasn’t teaching/writing now. I still spend time working in the community on the side wherever I can.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I can’t make it stop. It’s like a trance for me. I go somewhere I can’t reach elsewise.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi. I hate to say it, but I rarely watch films. It’s been awhile, but the last one I really recall watching and changing me is Moonlight .

19 - What are you currently working on?

I just wrapped up revisions of my first full-length, The Patient is an Unreliable Historian! God-willing, it will be out with Omnidawn in 2024!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 19, 2023

Nathanael O’Reilly, BOULEVARD

46.

squirrels snicker, chuckle & squawk

scamper up tree trunks across limbs

& boughs, jump from trees to fence-tops

sprint across lawns, duck under hedges

& shrubs, scurry along sidewalks

with acorns gripped between teeth, zig-

zag across the boulevard, dance

along black powerlines with erect

tails, descend onto leaf-strewn lawns

burrow into brown grass with front paws

digging up worms, swivel heads & prick

ears when dogs bark & cars brake, chase

each other up the alley, squat

atop blue recycling bins, grip

branches swaying in the wind, bouncing

beneath their weight, leap from rooftops

speed like furry animals through the air

I recently saw a copy of Texas-based Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly’s pandemic-era BOULEVARD (Co. Tipperary, Ireland: Beir Bua Press, 2021), a sequence of seventy-six numbered poems that narratively speak to his immediate local in a relatively straightforward manner, offering a sequence as a kind of lyric montage of the locked-down hyperlocal across a period he is unable to travel either to his home-geographies of Ireland or Australia. “a young woman emerges / from a backdoor wrapped in a green // blanket,” he writes in “26.,” “runs across the boulevard / holding a blanket across her chest // returns twenty seconds later / with a puppy tucked in her armpit [.]” There is something of the narrative structure to his sequence that is reminiscent of the work of the late Fredericton poet Joe Blades, specifically his

river suite

(Toronto ON: Insomniac Press, 1998), a book-length sequence on the hyperlocal that also included long stretches of montage narrative, both of which are constructed around a geographic thread or through-line as its central anchor, from Blades’ Saint John River to O’Reilly’s Benbrook Boulevard, in his adopted home of Fort Worth, Texas (I should arguably also mention Vancouver writer Michael Turner’s classic 1995 poetry collection

Kingsway

, which also utilizes this particular through-line structure). As such, it is O’Reilly’s “boulevard” from and through which the entire poem ripples, simultaneously moving beyond and returning, yet again, offering descriptive moments and scenarios involving neighbours, squirrels, crosswalks, university students and fathers with strollers. It is as though O’Reilly composes the length and breadth of this sequence from the safety of his window, seeking beyond what he can see, but held to what the situation of a global pandemic might allow. As the sixth poem in the sequence reads:

I recently saw a copy of Texas-based Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly’s pandemic-era BOULEVARD (Co. Tipperary, Ireland: Beir Bua Press, 2021), a sequence of seventy-six numbered poems that narratively speak to his immediate local in a relatively straightforward manner, offering a sequence as a kind of lyric montage of the locked-down hyperlocal across a period he is unable to travel either to his home-geographies of Ireland or Australia. “a young woman emerges / from a backdoor wrapped in a green // blanket,” he writes in “26.,” “runs across the boulevard / holding a blanket across her chest // returns twenty seconds later / with a puppy tucked in her armpit [.]” There is something of the narrative structure to his sequence that is reminiscent of the work of the late Fredericton poet Joe Blades, specifically his

river suite

(Toronto ON: Insomniac Press, 1998), a book-length sequence on the hyperlocal that also included long stretches of montage narrative, both of which are constructed around a geographic thread or through-line as its central anchor, from Blades’ Saint John River to O’Reilly’s Benbrook Boulevard, in his adopted home of Fort Worth, Texas (I should arguably also mention Vancouver writer Michael Turner’s classic 1995 poetry collection

Kingsway

, which also utilizes this particular through-line structure). As such, it is O’Reilly’s “boulevard” from and through which the entire poem ripples, simultaneously moving beyond and returning, yet again, offering descriptive moments and scenarios involving neighbours, squirrels, crosswalks, university students and fathers with strollers. It is as though O’Reilly composes the length and breadth of this sequence from the safety of his window, seeking beyond what he can see, but held to what the situation of a global pandemic might allow. As the sixth poem in the sequence reads: at the corner of University

& the boulevard a group of twenty-

ish students throw a birthday bash

during lockdown in the parking lot

behind their apartment building

play beer pong & twerk to a pumping

sound system, yeehaa down a twenty-foot;

high inflatable slide, carouse in swim-

suits while the virus kills

Adding to a growing list of pandemic-era compositions, including Nicholas Power’s chapbook ordinary clothes: a Tao in a Time of Covid (Toronto ON: Gesture Press, 2020) [see my review of such here], Zadie Smith’s Intimations: Six Essays (2020), Australian poet Pam Brown’s Stasis Shuffle (St. Lucia, Queensland: Hunter Publishers, 2021) [see my review of such here], Lillian Nećakov’s il virus (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2021) [see my review of such here] and Lisa Samuels’ Breach (Norwich England: Boiler House Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], O’Reilly’s deliberately aims his project outward, allowing any other considerations of beyond or within to sit within the particular bounds of the view beyond his window. As he offers in his short introduction: “Boulevard explores the life of a street and neghbourhood over the course of a year during the pandemic. I forced myself to write about events happening in front of my house, in nearby backyards, a couple of blocks to the east and west along the boulevard. Instead of travelling in search of subject matter, poetry came to me.”

February 18, 2023

ryan fitzpatrick, Sunny Ways

No I wasn’t in great shape before I signed the

contract but

no the Frank Slide didn’t happen but

no we may have worked there but

no we never lived there but

no we don’t have to pull out but (“Hibernia Mon Amour”)

The latest from Toronto-based and displaced Calgary/Vancouver poet and critic ryan fitzpatrickis

Sunny Ways

(Toronto ON: Invisible Publishing, 2023), following an array of chapbooks as well as his full-length collections Fake Math (Montreal QC: Snare Books, 2007),

Fortified Castles

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Coast Mountain Foot (Talonbooks, 2021) [see my review of such here]. Constructed out of two extended long poems—the thirteen-page “Hibernia Mon Amour” and eighty-page “Field Guide”—the paired duo critique and examine resource extraction, and rightly savage a corporate ethos simultaneously bathed in blood and oil, and buried deep (as one’s head in the sand), where corporations might pretend that no critique might land. Across a continuous stream of language-lyric, fitzpatrick writes of ecological devastation and depictions, planetary destruction, industry-promoted distractions and outright lies. Composed in 2014, the first sequence, “Hibernia Mon Amour,” as his notes at the back of the collection offer, was “originally commissioned by Daniel Zomparelli and Poetry is Deadmagazine to coincide with an exhibition of Edward Burtynsky’s work at the Vancouver Art Gallery. I was struck by the ways Burtynsky’s massively scaled photographs of the Alberta Tar Sands differed from another set of photographs appearing on Instagram at the same time under the hashtag #myhiroshima. The hashtag was used by Fort McMurray residents after Neil Young compared the Alberta Tar Sands to the effects of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima, Japan at the end of World War II. The hashtagged photos shared scenic natural views, keeping any work sites or toxic sinks safely out of frame.” The poem is set as short burst of accumulations, all approached from the level of a refusal of corporate responsilibity, instead issuing what appear no more than a series of corporate excuses and self-justifications:

The latest from Toronto-based and displaced Calgary/Vancouver poet and critic ryan fitzpatrickis

Sunny Ways

(Toronto ON: Invisible Publishing, 2023), following an array of chapbooks as well as his full-length collections Fake Math (Montreal QC: Snare Books, 2007),

Fortified Castles

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Coast Mountain Foot (Talonbooks, 2021) [see my review of such here]. Constructed out of two extended long poems—the thirteen-page “Hibernia Mon Amour” and eighty-page “Field Guide”—the paired duo critique and examine resource extraction, and rightly savage a corporate ethos simultaneously bathed in blood and oil, and buried deep (as one’s head in the sand), where corporations might pretend that no critique might land. Across a continuous stream of language-lyric, fitzpatrick writes of ecological devastation and depictions, planetary destruction, industry-promoted distractions and outright lies. Composed in 2014, the first sequence, “Hibernia Mon Amour,” as his notes at the back of the collection offer, was “originally commissioned by Daniel Zomparelli and Poetry is Deadmagazine to coincide with an exhibition of Edward Burtynsky’s work at the Vancouver Art Gallery. I was struck by the ways Burtynsky’s massively scaled photographs of the Alberta Tar Sands differed from another set of photographs appearing on Instagram at the same time under the hashtag #myhiroshima. The hashtag was used by Fort McMurray residents after Neil Young compared the Alberta Tar Sands to the effects of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima, Japan at the end of World War II. The hashtagged photos shared scenic natural views, keeping any work sites or toxic sinks safely out of frame.” The poem is set as short burst of accumulations, all approached from the level of a refusal of corporate responsilibity, instead issuing what appear no more than a series of corporate excuses and self-justifications: No we have decades of research that makes us

horny to test at this scale but

no we wont be able to submerge Stanley Park

to a depth of three metres but

no can you do thirty but

no there’s going to be pressure to extract all

of it but

no way we’re fucking waiting for spring melt

fitzpatrick’s work increasingly embraces an aesthetic core shared with what has long been considered a Kootenay School of Writing standard—a left-leaning worker-centred political and social engagement that begins with the immediate local, articulated through language accumulation, touchstones and disjointedness—comparable to the work of Jeff Derksen, Stephen Collis, Christine Leclerc, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Colin Smithand Rita Wong, among others. Whereas most of those poets I’ve listed (being in or around Vancouver, naturally; with the Winnipeg-centred exception of Colin Smith) centre their poetics on more western-specific examples—the trans-mountain pipeline, say—fitzpatrick responds to the specific concerns of his Alberta origins, emerging from a culture and climate that insists on enrichment through mineral extraction even to the point of potential self-annihilation. Offering an explanation to the book’s title, to open his “NOTES” at the end:

Sunny Ways takes its title from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2015 election victory speech where he exclaimed to a crowd of true believers: “Sunny ways, my friends! Sunny ways! This is what positive politics can do!” Trudeau references Wilfrid Laurier’s tactical turn away from political sniping and toward a greater spirit of cooperation within government—a hope that the warm rays of the sun will prove more effective than the cold threat of the wind. In an 1895 speech, Laurier asks, “Do you not believe that there is more to be gained by appealing to the heart and soul of men rather than to compel them to do a thing?” There’s a lot of hope in Laurier and Trudeau’s shared appeal to positivity, but the more I turn this sunniness over, I find less to be hopeful about. The political hopefulness espoused by Trudeau feels potent, but can it combat the sunny ways of rising temperatures and smoke-filled cities?

“[…] you sit in the window,” he writes, as part of “Field Guide,” “of whatever Starbucks this is // one frame unfolding // across the scene of another // as the Climate Strike passes // because you can’t take crowds // and have a history of panic attacks […]” Composed as a continuous line, a continuous thread, the ongoing “Field Guide” writes the oil sands but also allows itself as a kind of catch-all, allowing for a multitude of fragments, concerns, complaints and threads, built out of an endless array of lines stacked and run down the length of each page. As page sixty-one of the collection, mid-point through the long poem, reads, in full:

and this time it’s much safer in

listening to the way Kate Bush rhymes

plutonium with every lung

it doesn’t get too hot here

so long as you make friends with the A/C

tuck into your draft

the first heat event of the season

that upswings the temperature

between the cooling stations

laid out on the city’s online map

a continuous path between spray parks

across Metro Toronto

your new mode of urban exploration

looks for the hidden pockets of cold air

folded into the entropies

of the traffic in the street

you canter where you please

teeth on the eve of activity

February 17, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jaclyn Desforges

Jaclyn Desforges

[photo credit: Jesse Valvasori] is the author of

Danger Flower

(Palimpsest Press/Anstruther Books), one of CBC's picks for the best Canadian poetry of 2021. She's also the author of a picture book,

Why Are You So Quiet?

(Annick Press, 2020), which was shortlisted for a Chocolate Lily Award. Jaclyn is a Pushcart-nominated writer and the winner of a 2022 City of Hamilton Creator Award, a 2020 Hamilton Emerging Artist Award for Writing, two 2019 Short Works Prizes, and the 2018 RBC/PEN Canada New Voices Award. Her writing has been featured in Room Magazine, THIS Magazine, The Puritan, The Fiddlehead, and others. She is an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia’s School of Creative Writing and lives in Hamilton with her partner and daughter.

Jaclyn Desforges

[photo credit: Jesse Valvasori] is the author of

Danger Flower

(Palimpsest Press/Anstruther Books), one of CBC's picks for the best Canadian poetry of 2021. She's also the author of a picture book,

Why Are You So Quiet?

(Annick Press, 2020), which was shortlisted for a Chocolate Lily Award. Jaclyn is a Pushcart-nominated writer and the winner of a 2022 City of Hamilton Creator Award, a 2020 Hamilton Emerging Artist Award for Writing, two 2019 Short Works Prizes, and the 2018 RBC/PEN Canada New Voices Award. Her writing has been featured in Room Magazine, THIS Magazine, The Puritan, The Fiddlehead, and others. She is an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia’s School of Creative Writing and lives in Hamilton with her partner and daughter. How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’ve had publishing baby steps. I don’t have a clear before and after. I started off with my chapbook, Hello Nice Man, which came out with Anstruther Press in 2019. That was a wonderful experience, not just because I got to work with Jim Johnstone on my poems, but because I got to go through the whole cycle of launching something without the immense crushing weight of it being a full-length book. Strangely it ended up being a more public launch than my subsequent two books, because those came out during the pandemic.

So with Hello Nice Man, I ended up throwing a big party here in Hamilton and inviting everyone I knew. Family, friends, writers. My mentor Miranda Hill came and introduced my reading and said such nice things. My brother sang songs. It was really a blast. I’m grateful that I did that, that I hired a caterer and everything and made a big thing of it. At the time it was all just for fun, but those memories are really important to me now.

After HNM, Why Are You So Quiet? (Annick Press, 2020) came out. That felt higher stakes than the chapbook experience, but in some ways it felt lower stakes than the release of Danger Flower the following year. Writing the picture book wasn’t something I planned on (though a psychic did predict it, back when I was a teenager.) So that whole thing just felt really fun. Danger Flower was the culmination of a wildly improbable goal I’d set for myself when my daughter was a baby. The idea of me actually having a real live poetry collection published by an actual publisher seemed impossible. I wanted it too badly to even think about.

Mostly I felt relieved when my books came out. I'd always had some tiny secret faith in my future as a writer, I think? But I wasn't conscious of it. Most of me thought it was highly unlikely that I would both desperately want to be a writer and also be capable of being a writer, and also have all those necessary synchronicities line up in order for this stuff to actually happen. Like, what are the odds? I remember having those thoughts in grade 4.

Now my understanding of reality is such that I think my early longing to be a writer in the world was a kind of premembering. But having my books come out — especially Danger Flower — allowed me to relax finally, because something I always privately believed inside myself — I will write a book of poems— finally existed in the world. It sort of reminds me of when I was first pregnant with my daughter, being as careful as possible on the subway stairs. She was only the size of a grain of rice and I said to her silently, I know you are real. But it was terrifying because I was the only person in the universe who knew she was real. You know? She was the realest anything. She was my grain of rice. And this book was real before now, too. All these years. Why Are You So Quiet? was real, too. I’m so relieved that my creations are out in the world now being perceived by others, because it is a lot to carry the weight of something’s realness all alone.

How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve done every kind of writing. It’s hard to know what came first. My first self-published work was a how-to guide for collecting Beanie Babies. That was probably grade three. My mother printed it out and distributed it to various family members. I won a poetry contest through the library when I was in high school, but I was too embarrassed to show up to the award ceremony. My mom still has that poem framed. It wasn't awful.

After university I went to journalism school, I wrote for magazines, I did ghostwriting. But when I decided to really make an effort at creative writing I chose poetry because I have always had an internal radio station of poetry in my head, I guess the way other people have an internal monologue. It used to frustrate me because I wondered why I wasn’t daydreaming about characters like other writers. The things I wanted to write about didn’t have anything to do with people, for the most part. I wanted to write about what I felt and how I experienced the world. I didn’t see myself reflected in three acts or a hero’s journey. My inner world isn’t particularly plotty.

Plus, I’m really concise. Maybe not in this interview, but generally. I’m traumatized by bullshitting my way through essays in school, trying to hit the word count. I just wanna say what I wanna say and get outta there. Poetry is good for that.

How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to write in quick bursts. A first draft of anything is generally pages and pages of meandering non-linear thoughts. Partway through I’ll start writing at the top of a document instead of continuing at the bottom. It’s sort of a collecting process — ideas, lines. It’s messy and it has to be. If I let the control-y part of myself get involved at that point, she’ll control the life right out of the project.

It has to be dark and not looked at directly. It’s a mess. It’s not a shitty first draft because it’s not even on the continuum of good and bad yet. It just is what it is, and I let my pile of pages grow until I start to get a nagging sensation that it’s time. And then I print the whole thing out, highlight the parts I like, and then I open up a new document and start writing it from the beginning.

Before I got comfortable with this process I would do only the bare minimum of collecting and I would get to arranging and put all of my energy there. Because I wanted so badly to make a new poem. Now I’ve made lots of poems so I can play in the muck for longer. My new poems are longer and fuller than my earlier ones. I’m letting them stretch their legs a bit. I’m giving a light touch when it comes to editing. My goal used to be make good poems. My new goal is to make poems that feel alive.

Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems always come from the same place, which is some physical felt sensation in my body — like some tightness on my throat or whatever — which turns out to be where emotions and images and memories are stored. So I start with the physical sensation, see what lives in there, write those things down and then arrange the lines into a poem. It’s very somatic. I’m glad it is. I find it exhausting to approach poetry as an academic exercise these days. I’m just not as interested in my own thoughts as I used to be. I’m trying to reach past my intellect as much as possible for something else.

Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. I love reading poetry out loud, especially my poetry, because it’s written in my own kind of music. I’m grateful people want to hear them. Reading poems out loud is the culmination of the creative process for me. I think my poetry is best experienced out loud.

Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think the question I'm always getting at is, what is true? I'm always trying to say the truest thing as plainly as I can.

I try not to get too theoretical these days. I'm trying to stay as rooted as possible. But the themes that come through in my work tend to be about bodies, quietness, nature, mothering, sexuality, trauma, neurodivergence and consciousness.

What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think there are different kinds of writers and they occupy different kinds of public roles. I have a clear sense at this point of what my role is as a person/writing person in public, but I wouldn’t say it’s what anybody should be. It just sort of is who I am. I think my role as a poet is to stay in tune with what I’m picking up energetically, what I’m thinking about and feeling, and getting it down on the page. The best feeling is when people recognize their own complex emotions in my poems. They read and feel seen. That matters to me a lot.

I’ve said before that I feel sort of like a mermaid, like I occupy two different worlds, one normal one on shore in which I go grocery shopping and stuff, and another underwater life. And I feel kind of weird and like I don’t belong in either world, but it’s okay because I have an important job to do. I have to dive for shiny things and bring them back to shore. And the shiny things help people get through, I hope.

Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I like working with an editor, especially for fiction. Usually by the time I get to the submissions stage, I have been staring at whatever project for so long that I can’t make heads or tails of it. So it’s nice to have an external person. Poetry-wise, I have worked with so many wonderful teachers and mentors. I feel now like I am very in tune with my poems. I don’t seek outside feedback as much with poetry anymore. I have loved ones to whom I send poems, usually in audio format, but I don’t ask for feedback. And poetry editing is such a tricky thing. It requires a light touch. Edit a poem too much and it ceases being the same poem. I like creating iterations instead of fiddling with each one for too long.

What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I can’t remember if this was Margaret Atwood or somebody else. Maybe it was a chorus of people. Take care of your body so you aren’t in pain while you’re writing. I have to meditate and do yoga and eat properly and sleep properly to keep my mind clear and able to write things. If I don’t do my stretches I’m hunched over in agony at the keyboard. Eat soup, make a story. I think we tend to forget how physical we are. I think I tend to forget how physical I am. I live in my head a lot. I’m constantly trying to bring my consciousness down into my body. But it’s complicated in here and uncomfortable sometimes.

How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to children's books)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s pretty easy. I’ve written in all kinds of genres. It’s fun to shake things up. I think writing in different genres is great because it also opens you up to new audiences. There are some folks who just aren’t into poetry and who wouldn’t think of buying a collection. That’s cool. I think my fiction is infused with my poetry, and my picture book, too. It’s just a different form. I’m still bringing the sparkly treasures onto the shore.

What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

These days I wake up at six and do meditation and yoga. Then I write for an hour, with coffee. Get my kiddo ready for school, drop her off. Walk in the woods. Then I work for a few hours, nap at one. Pick the kiddo up from school. Rinse and repeat.

I’m not the kind of writer who writes for a long time every day. It’s never more than an hour or two. Most of my work involves teaching, doing public appearances, reviewing poetry for the Hamilton Review of Books, and the usual sort of administrative stuff of life. I like being out in the world, teaching and speaking. I’ve tried in the past to cut that stuff away and be a writer who just writes all day, but I get bored and lonesome. I can write a lot in a very short period of time. A a few thousand words in an hour. I can’t sit there and do that all day. I like having other things to do.

When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Writing for me is just listening to the poetry radio station in my head and writing down what I hear. So if it’s not coming through, it’s for a reason —- usually my nervous system is all wound up, and I’m suffering in other ways too in addition to not writing. So I have to solve the nervous system problem. Which sucks usually because it means I’ve been avoiding some kind of pain or issue, and now I have to face it.

The act of writing itself is easy. It’s opening an app on my phone and typing some words. If I can’t do that it’s because there is something wrong. Maybe I’m making up some big story about what people will think about me or my work. If it’s a problem like that, I need to surrender to the reality that I can't control what people think about it. That can be very uncomfortable. I prefer to be certain about things. But that’s not reality.

Things that don’t work to jumpstart my writing these days: deadlines, competitiveness, the desire to meet social expectations. I can't scare myself into compliance anymore. I have to solve the problem directly.

What fragrance reminds you of home?

Library books. Hamburger helper. That post-vacuum smell.

David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes. Yes and yes and yes. All the things. Being in nature is important to me. Science especially is really nourishing for my writing as a source of metaphor. I love reading about insects and their strange, unfamiliar lives. I also really love surrealism in all its forms. And horror movies! Hereditary is one of my favourites. I think it’s really important for me to not get too caught up in one particular form of expression. It’s important for me to play around in other forms and spheres of life. Not everything is writing.

What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are too many to count so I'll just name a handful. Autobiography of Death, which was written by Kim Hyesoon and translated by Don Mee Choi. All The Gold Hurts My Mouth by Katherine Leyton. Mary Oliver. Ariel Gore. Angela Carter. Carmen Maria Machado.

What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Record an audiobook. Start a chapbook press. Write a novel. Edit an anthology. Write a video game. I mostly just want to keep making stuff forever.

If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

When I was in grade eight, we had to do this online career quiz. My recommended careers included writer, psychotherapist or clergy. So probably something like that. There's also an alternate universe Jaclyn who became a massage therapist. In real life, I tried to be a journalist, but I wasn't cut out for it.

What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I tried to fight it. I really did. It was way too scary to become a writer. I had absolutely no faith that I would be able to do it. I was terrified of opening the box and seeing if the Schrödinger's cat of my writing talent was alive or dead. I'm pretty sure it was alive. I keep feeding it, anyway.

I tried to do something else, anything else. But all my abilities seemed to converge around writing and speaking. I'm not a linear thinker. Physical reality bores me. All I want to do is write and think and talk. Eventually I had to really give this a shot, stop dancing around it. Eventually it was scarier to not do it than to do it.

What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I'm reading Brat (Gordon Hill Press, 2022) by Sophie Crocker right now and really enjoying it. And the other night I watched Knives Out and loved it.

What are you currently working on?

I am writing a book about how to write poetry. It's also kind of a memoir about growing up in the 90s as an undiagnosed autistic girl, and how learning to make poems offered me a way back to myself after years of masking and self-abandonment. I'm also still tinkering with my short story collection, Mothworld, which was my MFA thesis. It's got ghosts and fig wasps and talking hamsters. Ultimately it's all about complex, offbeat, traumatized characters who find love and connection in unexpected places.

February 16, 2023

Elena Karina Byrne, If This Makes You Nervous

IF CONTENTS IN / JOSEPH CORNELL’S BOX

I won’t give way

to false teeth left in a champagne glass after a fight

nor fall from the shadow box into the boxer’s black gloves

smoke your pipe in the tortoise north darkness

between stars

deranged on the moon’s Geographiquemap of your face rising like

one scrap planet one startled bluing childhood doll head that calls for

recriminating light Cassiopeia’s soul over another lover’s bent knee

I can’t find a contagion of wanderlust the plumage-distance in a red

bird’s body now aviary-flown because we knew how long it would

take an apothecary’s colors to come bottling home

You underestimate

me my family’s inheritance of feeling its open airless universe &

you pay the color white a visit you startled deadout-you collecting

keys & coin are afflicted by newsprint flesh waiting for stacks of

matches to strike light under the skirt’s twirl & heat’s abyss

I can’t for this, be contained!

Los Angeles, California poet and editor Elena Karina Byrne’s fifth poetry collection (and the first I’ve seen), following

The Flammable Bird

(Zoo Press, 2002),

MASQUE

(Tupelo Press, 2008), Squander (Omnidawn, 2016) and If No Don’t (What Books Press, 2020), is

If This Makes You Nervous

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), a book composed and curated as an art gallery within the bounds of a poetry collection. Set in three sections—“Rock,” “Paper” and “Scissors”—Byrne composes each of her lyrics focusing on and across a particular visual artist and their work, writing as celebration, description and critique, as well as weaving in layerings of the author’s own responses. As she writes towards the end of the poem “FAREWELL FACE & ONE OF PICASSO’S”: “Picasso knew so well what he had in front of him: women neither / affirmed or denied belonging. That’s why his painting could destroy them.” Byrne layers her own details in through each lyric, offering how these particular artworks and aritsts may have impacted her own thinking and life, allowing certain works to burrow deep, as the best kind of art hopes to do. “But who will witness / an error in these repetitions,” she offers, as part of the poem “INSTEAD, THE HEAD: LORNA SIMPSON,” “in all circles as you fall square, feel your / body parts, feel the ground sliding from under you like the very last part / of your photo skin wishing itself forward & away, its last text turned / film-back through US history’s hate still smelling like your burnt hair of / chip cookies & baby milk.”

Los Angeles, California poet and editor Elena Karina Byrne’s fifth poetry collection (and the first I’ve seen), following

The Flammable Bird

(Zoo Press, 2002),

MASQUE

(Tupelo Press, 2008), Squander (Omnidawn, 2016) and If No Don’t (What Books Press, 2020), is

If This Makes You Nervous

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), a book composed and curated as an art gallery within the bounds of a poetry collection. Set in three sections—“Rock,” “Paper” and “Scissors”—Byrne composes each of her lyrics focusing on and across a particular visual artist and their work, writing as celebration, description and critique, as well as weaving in layerings of the author’s own responses. As she writes towards the end of the poem “FAREWELL FACE & ONE OF PICASSO’S”: “Picasso knew so well what he had in front of him: women neither / affirmed or denied belonging. That’s why his painting could destroy them.” Byrne layers her own details in through each lyric, offering how these particular artworks and aritsts may have impacted her own thinking and life, allowing certain works to burrow deep, as the best kind of art hopes to do. “But who will witness / an error in these repetitions,” she offers, as part of the poem “INSTEAD, THE HEAD: LORNA SIMPSON,” “in all circles as you fall square, feel your / body parts, feel the ground sliding from under you like the very last part / of your photo skin wishing itself forward & away, its last text turned / film-back through US history’s hate still smelling like your burnt hair of / chip cookies & baby milk.” Comparable to George Bowering’s infamous Curious (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1973), in which he composed poems for and around individual poets, Byrne’s poems write on and around each of her chosen subjects, and she moves through artists such as Andrew Wyeth, Laurie Anderson, Francis Bacon, Salvatore Dali, Diane Arbus, Caitlin Berrigan, Damien Hirst, Cindy Sherman and multiple others—sixty-six poems in total—across a space widely populated by an array of artists contemporary and historic. Each poem is thick with resonance and language twists, evocative with rhythm and sound across a visually descriptive narrative measure. As her powerful poem “STYLE OF IMPRISONMENT: DIANE ARBUS / PREDICTED THIS VIRUS” ends: “Even Jane Mansfield’s hair bow & my doctor’s Venice / bird mask hung for one cousin plague are not alone. It’s her / best shot at showing freaks alike where nature mirrors // our bathroom life & sets fire to itself in the heat.” [misspelling of “Jayne Mansfield” exists in the original text].

There are numerous questions and prompts that flow through these poems, questions and reactions that shift around parents, parenting, childhood, friends and losses, as well as a curious thread on mothering that works through the collection, as the poem “MOTHERWELL BLACK” ends: “Because maternal love is meant / to be echo-endless, something you want to throw yourself down into. / Because I’d throw myself in front of a revolver for them, dropping coins / like pulled fingernails or the memory of scars, still holding hands in / Spanish Franco’s frozen streets just to see black.”

February 15, 2023

Spotlight series #82 : Tom Prime

The eighty-second in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Canadian poet Tom Prime.

The eighty-second in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Canadian poet Tom Prime.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee and Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly.

The whole series can be found online here.

February 14, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Justene Dion-Glowa

Justene Dion-Glowa

is a queer Metis poet, artist and beadworker. They were born in Winnipeg and currently live in BC, Canada. They are a Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity Alumnus. Their microchap,

TEETH

is available from Ghost City Press.

Trailer Park Shakes

, their first poetry collection, is available from Brick Books.

Justene Dion-Glowa

is a queer Metis poet, artist and beadworker. They were born in Winnipeg and currently live in BC, Canada. They are a Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity Alumnus. Their microchap,

TEETH

is available from Ghost City Press.

Trailer Park Shakes

, their first poetry collection, is available from Brick Books. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Trailer Park Shakes is my first official book of poetry. While I wouldn't say my life is hugely different, I do think about my 11 year old self writing poetry, and how crazy it would be to let that kid know they one day they have a real book. I have also had lots of opportunity to connect with people through this work, which has dispelled a lot of the imposter syndrome I have felt as a new poet without a local scene to support me.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry as a means of coping with my childhood trauma all the way back in grade 6. I think at the time it offered me an opportunity to create something interesting or beautiful - and I had a lot of support from my teacher at the time to continue writing. He also encouraged me to speak openly about the content of the work with my class, which has served me well now that I have to read for strangers.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don't approach my work as projects, but more like collections. I tend to work on one poem until I feel satisfied with it, and then move on to the next. In this way the collection builds and becomes a project.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem is really a moment in time for me, captured. So while this book is certainly not a collection I planned out, I do have ideas about collections that have a more uniform subject matter across the whole work.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have really enjoyed public readings, and I think as I continue to do them, they will definitely become an important piece of the poetry things for me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don't concern myself with much besides the moment I'm writing about in terms of theory. I don't know that my work answers deep questions, only ensures people with similar experiences don't feel alone.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I believe that all art in general is the last place people can actually be themselves and express their real thoughts. We live very compartmentalized and individualized lives now, and my hope is to connect to community through the writing. Connection is the role of the writer.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

While having my first book edited was challenging for me, it was absolutely essential. We become attached to our work and I think the editing process can make a person feel misunderstood and underestimated in some ways. But I certainly feel the book has benefitted in amazing ways because of my two editors.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best advice I've ever received was to get paid to be me. Poetry is one piece of that, workshops are too, and so are other forms of art. I am fortunate to have the privilege to do this at least some of the time!

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a routine because as mentioned, I tend to write about moments, or in moments of inspiration. I need to put more effort into making time for writing, though.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I turn to the writing of others for sure. Some folks with completely different writing than my own can be very inspiring.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Home as a concept is too fractured for me. I can't answer this.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Definitely music has inspired my work, and nature as well. As I said reading the work of others is inspiring as well.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Indigenous poets tend to create work that I find deeply meaningful and relatable.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A hybrid work that's both literary and visual - art gallery style.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I could make enough money doing it I would be a barista - I absolutely adore coffee and the craft of making it.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I do a lot of different creative things. I think the main reason I returned to it was because of how fulfilling it was in my past.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I'm currently reading Bent Back Tongue by Garry Gottfriedson, and I just keep picking it back up again and again.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I'm currently doing art workshops and developing more intensive poetry workshops, as well as more poetry of course.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 13, 2023

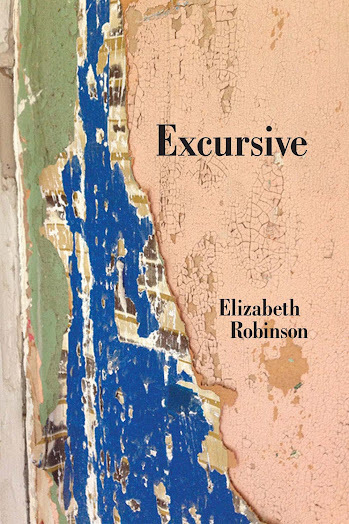

Elizabeth Robinson, Excursive

On January 1

for Norma Cole

Time is light,

that’s all. Her tongue

a version, a map

version, where star maps

are always off-history whether

translating light

from a far galaxy or a local

starlet. “Oh!”

she said, a figure of herself,

“Yes.” Whereupon the light

threw itself down and pierced

her tongue, where it remained

like a stud, that she licked against

her teeth as she spoke.

The latest from Bay Area poet and editor Elizabeth Robinson [see the recent festschrift I produced on her work here] is

Excursive

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2023). Excursive follows an array of Robinson’s chapbooks and full-length collections, including

blue heron

(Center for Literary Publishing, 2013) [see my review of such here],

On Ghosts

(Solid Objects, 2013) [see my review of such here] and Rumor (Free Verse Editions, Parlor Press, 2018) [see my review of such here]. Subtitled “Essays [Partial & Incomplete],” with addendum “(on Abstraction, Entity, Experience, Impression, Oddity, Utterance, &c.),” the seventy-seven poems in Excursion include titles such as “On Beauty,” “On Depression,” “On Epiphanies,” “On Happiness” and “On Mortality.” Robinson has been playing the form of “On _____” for a while now, threading through multiple of her published full-length collections, allowing the structure as a kind of linked “catch-all” across her poetic. The “On ____” is reminiscent of Anne Carson’s infamous collection Short Talks (London ON: Brick Books, 1992), with each Carson prose poem in the collection titled “Short talk on _____,” but the ongoingness across multiple collections that Robinson employs is comparable to Ontario poet Gil McElroy’s ongoing “Julian Days” sequence, one that has extended through the entire length and breadth of his own publishing history across more than three decades. “While the body,” Robinson writes, as part of the extended “On [a theory of] Resolution,” “why, it // remains aligned to its // thirst. You know this. // You deny this. The theory // of resolution is meteorological / and not eternal.”

The latest from Bay Area poet and editor Elizabeth Robinson [see the recent festschrift I produced on her work here] is

Excursive

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2023). Excursive follows an array of Robinson’s chapbooks and full-length collections, including

blue heron

(Center for Literary Publishing, 2013) [see my review of such here],

On Ghosts

(Solid Objects, 2013) [see my review of such here] and Rumor (Free Verse Editions, Parlor Press, 2018) [see my review of such here]. Subtitled “Essays [Partial & Incomplete],” with addendum “(on Abstraction, Entity, Experience, Impression, Oddity, Utterance, &c.),” the seventy-seven poems in Excursion include titles such as “On Beauty,” “On Depression,” “On Epiphanies,” “On Happiness” and “On Mortality.” Robinson has been playing the form of “On _____” for a while now, threading through multiple of her published full-length collections, allowing the structure as a kind of linked “catch-all” across her poetic. The “On ____” is reminiscent of Anne Carson’s infamous collection Short Talks (London ON: Brick Books, 1992), with each Carson prose poem in the collection titled “Short talk on _____,” but the ongoingness across multiple collections that Robinson employs is comparable to Ontario poet Gil McElroy’s ongoing “Julian Days” sequence, one that has extended through the entire length and breadth of his own publishing history across more than three decades. “While the body,” Robinson writes, as part of the extended “On [a theory of] Resolution,” “why, it // remains aligned to its // thirst. You know this. // You deny this. The theory // of resolution is meteorological / and not eternal.” The poems are also set alphabetically by titled subject, throwing off the collection’s easy narrative or thematic sequence, allowing the collage of her lyric to hold the collection together, akin to a fine tapestry. Throughout, she utilizes her declared subject-title as a kind of jumping-off point into far-flung possibilities: choosing at times the specificity of her declared subject, but refusing to be held or limited by it. “To her who assumes / this identity,” she writes, to close the poem “On Numbness,” “a citizen // befuddled by destination, / it’s not possible / to have arrived here from anywhere, // not possible to assimilate to new fluency.” In many ways, this is a book about the body and how the body reacts, moving from physical to physiological reaction, action and purpose, allowing the echoes of references and sentences to form a coherence that a more straightforward narrative might never allow. “I was a lung,” she writes, to end the poem “On Extinctions,” “a hardening lobe, while // the moving air curved as though an ivory horn // and lay still.” She writes out the body, using her titles as markers, and at times, anchors, providing a weight that occasionally prevents her lyrics from floating away entirely. At times, it seems she works from specifics into a rippling beyond the limitations of how each poem begins, as though the title is the pebble dropped into the pond, and the poem is the rippling effect on the water. She writes the body, and even the betrayal of the body, one that echoes across a prior period of illness, perhaps; and there is almost something of being only able to write of something directly by coming at it from the side. “Time was a tumor in its very own landmass.” she writes, to begin the poem “On Krakatoa,” “It couldn’t have been more intrepid.”