Ninie Hammon's Blog, page 3

September 1, 2013

I FINISHED My Novel So Why Do I Feel Like Crying?

Two events on different sides of the planet happened at exactly the same instant on Monday, August 11, 1969. One of them was in the Vale of Amberclewydd, Wales, where it was 10:33 a.m.

Alastair Shelbourne stopped in his daily trek up the mountain to the ridge when he heard voices rising out of the fog that lay like clotted cream in the valley at his feet. On the first day of the school year, children in the Gaynor Junior School were singing All Things Great And Beautiful and their voices, drifting eerily up through the thick white mist into the bright morning sunshine, were the voices of angels. The 62-year-old grandfather stood still, listening. Then he smiled. It was the last time he ever would.

Seconds later, he heard a grinding, rumbling sound. When he looked up, his final smile melted off his face like wax from a flickering candle flame. The gigantic pile of coal waste on the mountain above the village—above the school—was moving! More than a million tons of slurry had begun to slide, to flow down into the fog below in great liquefied waves, a thundering avalanche of black death.

That’s how When Butterflies Cry begins. I typed The End on the final draft of it today, FINISHED it—as in hit “send” to the publisher. My seventh novel, at 108,600 words it tips me over the top of 750,000 published words. Of course, when I told my grandson that, he judiciously pointed out, “Yeah, but you can’t count all those words because you used some of them more than once.”

Do you feel sad when your novel’s done?

There is a cherished tradition among authors—the tradition of… well, traditions. We writers like to come up with some “ritual” we perform every time we finish a manuscript. I don’t want to sound judgmental here, but I’m not completely certain you’re allowed to call yourself an author unless you do something.

Didn’t Hemmingway lean back and light up a cigar whenever he typed “the end?” Maybe that was Faulkner. Or Chaucer. Or Homer. (Think Illiad, not Simpson.)

I attended a writer’s conference not too long ago and sat down to lunch at a table with five strangers—two men and three women. We six represented a fair cross section of genre. Two romance writers, a paranormal, a YA, a scifi, a mystery and Ninie, the suspense author.

The topic turned to manuscript-completion traditions and we went around the table sharing.

The YA guy went first, said he had a tradition but it wasn’t one he could tell in mixed company. Moment of awkward silence … moving on.

The first romance writer said she didn’t know she was supposed to have a tradition but if she was supposed to have a tradition, well, my goodness, she would most certainly go out right now and find herself one, or make one up, or … did we have any suggestions?

The Irish mystery writer said he always went to the neighborhood pub and “stood a pint of Guiness” for everybody in the house.

The Irish mystery writer said he always went to the neighborhood pub and “stood a pint of Guiness” for everybody in the house.

The second romance writer said that when she completed each of her first two books, she poured herself a glass of wine, took it out to the deck and watched the sun set over the ocean. Then she moved. It lost some pizzazz, she said, drinking wine and watching the sun set over west Waxahachie.

The paranormal writer said hers was a one-word tradition: chocolate. In any form, whatever she can lay her hands on. She said she bought a box of chocolate-covered cherries and set it on her desk when she started her first novel, the cherries to be her reward for finishing it. They lasted almost to the end of Chapter Three.

Then it was my turn and I described my tradition, the one that hangs out there ahead of me as soon as I type “It was a dark and stormy night.” I pull up the manuscript to the title page. When Butterflies Cry by Ninie Hammon. I watch the cursor blink, blink, blink next to the final n on my name. And I let myself be sad.

I will miss these people. Grayson, the returning-from-Vietnam soldier and his brother Carter, the bootlegger. The beautiful Piper, the only woman either brother ever loved and the mysterious red-haired child known only as Maggie. I have spent 578 hours (I keep track, http://bit.ly/9eBook4Book ) with these people and all the other folks who inhabit the world between the covers of this book. We’ve endured grief and pain and terror together. We’re family. It’s like when your children move away from home. Oh, sure, it’s not like you’ll never see them again. But it will never be the same as scrubbing their jelly handprints off the wall or picking out their prom dress.

I hate goodbyes.

And I’m sad for another reason, too. I feel like I’ve just stamped an M on my book’s chest and tossed it into a bowl the size of Cleveland filled to the brim with M&Ms. As unique as all the flavors around it, my book has just the taste certain readers will love—but will they manage to find it among the millions and millions of others?

Tomorrow, I’ll get excited about the new people I will meet in The Knowing, folks I’ll live with, laugh with, suffer with and nurture through a tale to “the end.”

But today, I feel like crying.

Do you have a book-completion tradition? Wouldn’t you like to know what other writers do? Please do leave a comment below, describe yours and we can share.

August 25, 2013

The BEST–and WORST–ways to use back story

You DON’T want your reader to throw your novel at his sleeping cat.

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS

#1 BACK STORY

It was a dark and stormy night. Ellen felt her way across the room in the shadows and reached out to turn on the light. Someone else’s hand was already on the switch.

Ellen had been afraid of storms ever since her grandfather went out to fix a shutter flapping in the wind and was never heard from again. He had come to America from Scotland as a lad after his father was mysteriously murdered by the Black Watch because he had six fingers on his left hand. He had inherited the extra digit from his mother, whose own father accused her of being a witch because she looked just like her grandmother, who had …

AGGGHHHH! Enough with the shutters and fingers and witches already! Whose hand did Ellen feel on the light switch? (Imagine the whooshing sound of your novel flying through the air toward a sleeping cat.)

You DON’T want your reader to bump her head in your story.

The preceding is an example of an info dump and the likely reaction to one by Loyal Reader. An info dump is the hands-down worst way to introduce back story into your novel—for several reasons, the most notable being that it totally disrupts the flow of action. Any time you cause a reader to bump her head in your narrative, you’ve screwed something up and you need to go back and fix it. Info dumps are notoriously low ceilings.

I’m not saying you don’t use back story in your fiction. Of course you do. It is crucial, one of the ten ways to create unforgettable characters. Loyal Reader wants to know what happened in the hero’s life that made him arachnophobic, why the heroine hates men and what made the wimpy teenager decide to become a Navy SEAL.

What I am saying is that back story is like jalapeños, colonoscopies and other people’s pets. A little goes a long way. Your task regarding back story is two-fold.

First, you must decide what is the bare minimum back story you can provide in order for the reader to understand the character’s motivations and behavior. Don’t think snowsuit, think bikini—one that’s the size of two Band Aids and a hockey puck. Yeah, it’s cool to wax eloquent about the hero’s experiences spelunking in Peru or how the little old lady drove a tank during World War II. And if you’ve really done your homework, you know all that stuff because you have actually made up a complete history of each of your characters for your own use. But as soon as you type “It was a dark … ” you must decide how much of that information is necessary/enlightening for your reader.

And after you figure that part out, you must decide how you’re going to dispense that information through your story. Info dump is out. Scratch that one. But there are three other methods.

1. Prologue

Writers debate prologues like meteorologists debate global warming. Some writers hate them. Some writers can’t live without them. Some writers can’t live without hating them. We’re not going there. Perhaps you believe that before you start your story, it’s essential for your reader to know certain information or history. Or maybe you want to hook the reader with drama that occurs later in the book. Either way, the prologue is the only piece of real estate prior to Chapter One where you can park it.

I used prologues in three of my seven novels. Five Days in May is the story of four people who have penciled in death in one form or another on their calendars for Friday. Chapter One starts on Monday, but I wanted to hook the reader with the drama of a tornado that will change all the characters’ plans on Friday—so the tornado is in the prologue. In The Memory Closet, I wanted the reader to see before Chapter One the incident that marked the loss of all the memories from the first decade of the main character’s life because the story begins with the heroine’s bold plan to remember.

2. Memory

If something that happened in the past explains your character’s behavior in the present, the character can remember it. Done well, memories are glorious devices because they can be rendered internally or in dialogue. The important thing to keep in mind about memories is that they are totally a product of how a character perceived what happened. Two characters can recall the same event with totally different memories.

3. Flashback

While a memory is filtered through the point of view of the character and what is going on in the active story, a flashback is an instant replay, the event exactly as it occurred. A flashback will only work if it flows naturally from the narative. The present-day action is what the book’s about. I’ve read novels in which the action served as nothing more than a life-support system for cool flashbacks. If the past is more interesting than the present, set the book in the past.

4. Seasoning

You can sprinkle back story into your novel, a little here, a little there. It really does help to think of back story as salt—too much and you’ve ruined the soup.

Or you can give your reader back story based on the criteria the government uses to allow access to highly classified documents–on a need-to-know basis. When you’re dispensing back story, only tell the reader what he needs to know to be able to understand what’s going on at that point in the story.

Shhhh. Be vewry, vewry quiet.

So you won’t disrupt the flow of the tale.

Loyal Reader won’t bump his head.

And his cat can keep sleeping.

Write on!

9e

August 19, 2013

Ten Ways to Create Unforgettable Characters

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS

My oldest son and his friends used to play Dungeons and Dragons back when it was a game that came in a box with dice, a game board and little metal game figures—a pre-digital version. (We painted pictures of it on the walls of our cave.)

From what I observed while refilling their bowls of Fritoes and bean dip, it appeared that each of the boys had a character, a warrior who possessed all manner of weapons, spells and powers.

Apparently, the game consisted of dispatching these characters into dank and dusty caverns in search of treasure. Or out to do battle with the requisite fire-breathing dragon guarding a creepy castle stuffed to the parapets with gold.

How, exactly, I was coerced into playing the game myself is still a matter of hot debate in our family. (I’m thinking some sort of out-of-body experience.) But there did come a day when I sat with six pre-teen boys and asked, “Ok, who am I—who’s my character?”  I assumed I’d be some sort of warrior princess, armed with spear and sword or maybe a sorceress with a pocket full of toad’s earlobe and hair of aardvark.

I assumed I’d be some sort of warrior princess, armed with spear and sword or maybe a sorceress with a pocket full of toad’s earlobe and hair of aardvark.

“You’re nobody, Mom,” my son responded, “…yet.”

Seems I had to build my character. And that construction consisted of a maddening sequence of rolling the dice to determine the level of my strength, what equipment I had, what weaponry I could take into battle—even what life form I was. That was the deal killer. When it turned out I was an asthmatic troll with a slingshot, I bailed.

You see, I wanted to go on quests and adventures, slay dragons, find treasure—maybe even do a little side-jobbing as a looter/pillager. I did not want to waste an afternoon just getting to the point where I was able to engage the game.

You can see where this is going, can’t you.

There are several clear parallels between playing Dungeons and Dragons and writing a novel. The most obvious, of course is that a writer must know the characteristics of his hero before he sends the poor schlep out to fight the bad guy. But equally obvious is the fact that the writer can’t expect to back a dump truck up to Loyal Reader and unload all the details of the hero into her lap before he allows her to play the game.

We must know something about our characters before we begin their story—true. But the key word in that sentence, folks, is “something”—NOT “everything.” The tricky part, as anyone who’s ever written a novel will tell you, is that characters change as the story unfolds. Sometimes, perhaps even most of the time, they surprise you. They grow, reveal passions and foibles, interests and strengths, quirks, ticks, weaknesses and amazing humor you never imagined they had when you first typed “It was a dark and stormy night.”

Consequently, it’s not only a bad idea to unload the whole character-trait truck in Chapter One—you can’t. You don’t know all the character’s traits yet. What you should do, and all you can do, is give readers just enough information to get them started and reveal more and more as the tale plays out.

There are as many different methods of designing a novel as there are novelists. Some writers start with a character and build a story around her. Others start with a story and come up with characters to execute the plot. Still others start with theme, a point they want to make, and design a story and characters to convey that message. There even are a handful of writers who sit down at the keyboard and type “It was a dark … ” with absolutely no idea if it ever stops raining. But it doesn’t really matter where you start, at some point in the process you WILL have to come up with characters and it is your job to make those characters compelling, interesting and realistic or Loyal Reader will nod off and start drooling on page three.

I’m not here to tell you that great characters are more important to your novel that a great plot. The best characters in the world eventually have to DO something. But I am 100 percent certain that if you can create characters the reader cares passionately about, characters who grab him by the lapels and drag him into the story to live it with them, characters Loyal Reader still considers family years later—you, my friend, have captured lightening in a mason jar.

How do you do that? How do you design great characters and then express those characters in your story? There are dozens of ways, of course, but I’ve narrowed my own list down to ten. (Why ten? For the same reason Jules Verne didn’t write Nineteen Thousand Five Hundred and Seven Leagues Under the Sea and God didn’t give us the Eleven Commandments. As I said last week, some things just is what they is.)

I believe you reveal the personality of your characters through:

1. Name

2. Back story

3. Physical description

4. Actions

5. Dialogue

6. Thoughts

7. Abilities and skills

8. What he wants most, fears most, loves most and most despises

9. The reactions of others to the character

10. The character’s reaction to other people

We’ll plop the suitcase filled with these ten elements up on the bed next week and start unpacking it.

Write on!

9e

August 11, 2013

Every Writer Has One–What’s Yours?

Every writer has one. From Tolkein to Stephen King and every scribe before or since. We all have a story about what it was that made us decide to become writers. Mine isn’t a what story. It’s a who.

Every writer has one. From Tolkein to Stephen King and every scribe before or since. We all have a story about what it was that made us decide to become writers. Mine isn’t a what story. It’s a who.

* * *

From the first of October every year until the end of February, my brother and I did everything we could to keep our grandmother from laughing on Thursdays. That was no easy task given there was little in life the old woman liked better than a good belly laugh. Said it prevented indigestion, promoted solid bowel movements and reduced suicidal urges.

“Laugh and the world laughs with you,” she’d say. “Cry and all you get’s snot on your lip.”

Her name was Bobo–for no reason anybody in the family could recall–and she was my hero, my role model and my best friend. She was also the first writer I ever knew, though not in the traditional definition of the word.

My great aunts and uncles claimed that Bobo came into the world squalling so loud and so hard she blew out all her “filters.” From that moment on, whenever she opened her mouth, her unedited thoughts flopped out. Even as a child, she said exactly what was on her mind as soon as it crossed her mind—a trait she displayed well into her nineties.

But what made a lasting impression on me, what shaped me and motivated me to become a writer myself was not so much what she said as what she wrote down.

Some of my most vivid childhood memories are images of my white-haired, hunch-backed grandmother with a for-real “fountain pen,” the stub of a No. 2 lead pencil or one of those fancy, clicking, ball-point thingys in her hand jotting something down in her little notebook. Or on a gum wrapper, a paper napkin, or the back of a grocery store receipt. She used whatever she could lay hands on to capture what she called “shiny talk,” her phrase for a particularly colorful use of language.

Much of the colorful language in our house wasn’t fit for repetition much less preservation. My father had been a Marine Corps Drill Instructor. Didn’t matter, though. The whole world was the source of Bobo’s material.

“This lawn mower sounds like a chain saw cutting through tin,” she jotted down in scrawling, arthritic handwriting on the back of an envelope after our next-door neighbor dropped by to return the one he’d borrowed. When she saw me reading it, she added, “Charlie’s right. I heard it. Felt like somebody was shaving my ears off with a cheese grater.”

“… the truth in long-johns with the butt flap down.” She overheard that remark at the table next to ours in a Mexican food restaurant and printed it in ink on a napkin—a cloth napkin that she proceeded to stuff into her coat pocket.

I always thought the best “shiny talk” was her own. When she took out her false teeth, her face from the nose down imploded and she looked like one of those Appalachian apple dolls. Her toothlessness gave her speech a peculiar flubbery sound I can still hear in my head, urging me to eat more.

I always thought the best “shiny talk” was her own. When she took out her false teeth, her face from the nose down imploded and she looked like one of those Appalachian apple dolls. Her toothlessness gave her speech a peculiar flubbery sound I can still hear in my head, urging me to eat more.

“Sugar, you’re skinny as a fried egg, you know that don’t you. Flat-chested as one, too.”

Or to behave properly. “You don’t straighten up, young lady, I’ll skin you alive with a potato peeler and screw your head off your shoulders like a lid off a pickle jar.”

Or to say grace before a meal. “You got to pray over it cause eatin’ unblessed food’ll give you the runs.”

I don’t know when I started to jot down shiny talk on my own. Seems now I’ve always done it. I once had yellowed spiral notebooks full of words and phrases in little-kid scrawl. Though a lifetime of moves eventually ate the notebooks, the habit that created them years ago remains. I have an Always Always Language List on my IPhone and on the desktop of my computer. (Always Always—to remind me how often to listen for creative language usage and how often to write it down.)

The only time I ever asked Bobo why she wrote down shiny talk, she shook her head and looked at me sadly, as if it was truly pitiful that I didn’t understand something so obvious to her.

“It’s catchin’ a firefly in a Mason jar, Sugar,” she said. “So you can watch it glow, all shiny—like words glow. Then you got to let it go.”

There was a heartbeat of awed silence before she burst out laughing.

“I swear, chile, you’d believe me if I told you dust bunnies was spiders turned wrong side out. Lots of life don’t make no sense. Some things just is what they is. ”

I glanced over at my brother. You see, it was Thursday. And Bobo was laughing. Just come in out of the cold after her weekly hair appointment, she was shivvering and hurried to the floor furnace to stand on the grate, letting the hot air billow her skirt out around her. But the problem was … well … Bobo had a weak bladder. As soon as she started laughing, the dreaded psssst, psssst, pssst sound, and accompanying stench, rose up from the grill.

Please believe me when I say that I tried, I really did, to come up with some shiny talk to describe this heartwarming domestic scene. Couldn’t do it. Some things just is what they is.

Those of you who’ve read The Memory Closet have already met Bobo, or a reasonable facsimile. She showed up unannounced on page three of my only first-person novel, unpacked her bags and moved in. Out of dozens of characters in seven novels, Bobo stands out. Many readers say she’s their favorite. I’m rather partial to her myself.

Next week in this space, we’ll begin a ten-week discussion of characters. How to make them as real, individual and memorable as … well, as your own grandmother.

Write on!

9e

August 3, 2013

Looking for your writer’s voice? Here’s how to find it.

July 18, 2013

One Thing You MUST Do After the Climax of Your Novel

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #9 RESOLUTION

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #9 RESOLUTION

No, wait—what about the little dog?

What dog?

The dog you introduced in Chapter 5. You remember, Sparky. The mutt the kid found at the rest stop and the kidnapper thought it would calm the boy down so he let him keep it. Did the kid take Sparky with him when he got away?

Uh … well …

And the old couple—what happened to them?

There was an old couple?

The old couple at the gas station! Maude and Clarence Higginbotham. Maude recognized the boy from his picture on television but Clarence said it wasn’t the same kid and they argued about calling the police. Did they? Is that why that State Trooper pulled up? And when the kidnapper blew up the propane tanker to get rid of the Trooper, did Maude and Clarence die in the fire?

Well … I guess they … I don’t know.

You don’t know! How can you not know, you wrote it.

The preceding is not a conversation you want to have with Loyal Reader at a book-signing. Or worse—a conversation you never have with anybody so you have no idea why the proceeds from your book sales only inhabit the right side of the decimal point.

Unless you want your reader to throw your book at the cat, don’t leave him hanging at the end. After he has become invested in the characters and engrossed by the story, it’s absolutely maddening not find out what happens. Loose ends are a result of muddy thinking and sloppy writing and they’re as deadly to your novel as holes in the plot.

*Indulge me, here. I have a personal rant about holes in a plot. I’m not one of those readers who goes out looking for them, but sometimes the little buggers come running up and kick you in the shin. Stephen King (in my opinion one of the all-time best writers on the planet) left a hole you could drive a forklift through in the plot of Black House. The room is pitch dark. The bad guy uses his victim’s blood (from a puddle of it where the victim was hiding, which, oh by the way, the bad guy couldn’t have found in the dark) to write a message on the wall to the good guy. I’m ok with something like “you die!” Maybe even “I’ll kill you,” though that’s a stretch. But this guy writes a sentence—uses the good guy’s name, which is nine characters long. How do you do a thing like that—in blood, on a wall, when you can’t see? You don’t. End of rant.*

*Indulge me, here. I have a personal rant about holes in a plot. I’m not one of those readers who goes out looking for them, but sometimes the little buggers come running up and kick you in the shin. Stephen King (in my opinion one of the all-time best writers on the planet) left a hole you could drive a forklift through in the plot of Black House. The room is pitch dark. The bad guy uses his victim’s blood (from a puddle of it where the victim was hiding, which, oh by the way, the bad guy couldn’t have found in the dark) to write a message on the wall to the good guy. I’m ok with something like “you die!” Maybe even “I’ll kill you,” though that’s a stretch. But this guy writes a sentence—uses the good guy’s name, which is nine characters long. How do you do a thing like that—in blood, on a wall, when you can’t see? You don’t. End of rant.*

The place to tie up loose ends is after the climax. That’s why they call this part of a story “the resolution.” It’s the answer to the question “now what?” It’s what’s left of the story after the hero wins the battle or the girl or throws the ring into the Cracks of Doom on Mount Doom (in the Land of Mordor, where the shadows lie).

Some resolutions are fairly drawn out. In The Return of The King (the book, not the movie) the resolution involves the company of hobbits returning to the Shire where they must fight the final battle of the Great War and Tolkein ties up the loose end of what happened to Saruman and Worm Tongue.

Others are brief. In Lord of the Flies, Ralph runs from the savage boys in the burning jungle out onto the beach and there stands a British Naval officer. Ralph and the other boys begin to cry. And that’s it—the book’s over.

Others are brief. In Lord of the Flies, Ralph runs from the savage boys in the burning jungle out onto the beach and there stands a British Naval officer. Ralph and the other boys begin to cry. And that’s it—the book’s over.

For obvious reasons, the movie versions of books cut the resolution down to sound bytes. The resolution of Gone With The Wind goes on for several pages, very small print. It’s the part after Scarlet figures out she’s spent her life with her wagon hitched to the wrong horse, romantically speaking, and Rhett dumps her. The movie version is more succinct: Scarlet tells Rhett she loves him, he tells her he doesn’t give a damn and she determines to “think about that tomorrow.” Badda boom, badda bing, it’s over.

It is my personal preference to keep the resolutions in my novels brief. After the climax, I try to get out as quick as I can. As a reader, I don’t like lingering resolutions so I try not to write them. As a writer, I particularly like to tie up some loose end in an astonishing way right before the two words centered on the last page. In The Last Safe Place, something is explained that the reader may have suspected, but it is astonishing nonetheless and two sentences later the book is finished. In my WIP, When Butterflies Cry, a loose end from the first 100 words of the book is tied up in a red ribbon, hopefully leaving Loyal Reader with her mouth hanging open.

A word of caution here—if you decide to employ that technique, it can’t be artificial, something you tacked on just to end with a flourish. Unless the reader does a duh forehead slap at your reveal, you’re better off tying your loose ends with a simple square knot. But do tie them; don’t leave any of them dangling.

Write on!

9e

July 14, 2013

There’s Only One Door into Your Story–Build It RIGHT!

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #8 INCITING INCIDENT

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #8 INCITING INCIDENT

You and your date snuggle down into comfy seats. On the screen in front of you, the Pixar desk lamp comes hop, hop, hopping into its spot between the P and the X, looks at you with its inscrutable light-bulb eye and the show begins.

Between handfuls of popcorn and Raisinettes, you watch as this little green eyeball monster and his furry turquoise friend do life in a world on the other side of closet doors. Then it’s night in the scream factory, furry turquoise monster sees a live door and steps inside to investigate—into a world where the mere touch of a human child is fatal.

You’re getting a little nervous at this point.

Furry monster trips, gets tangled up in mobiles and toys, barely makes it back out into the factory. He leans against the closed closet door panting, and then … he stops by the office to leave the paperwork with Roz the Slug, goes home and orders a pizza. For the next 83 minutes, you watch daily life in Monstropolis.

You leave the theater … unsatisfied.

Next night, you stay home and watch a classic on Netflix. There’s this young man on a desert planet who has bought these two droids—a tall, gold one with a British accent and a blue one the size and shape of a fire hydrant that speaks in honks and beeps. The young man is cleaning sand out of the blue droid’s gears when suddenly … he pulls out a potato chip stuck in the hard drive. Rather than watch the young man cut doughnuts with his land cruiser on an endless expanse of desert sand for the next 75 minutes, you flip off the TV and head to bed.

And you think–didn’t movies used to be better? There was that one about the little girl in Kansas who runs away from home and there’s a tornado and … it takes the roof off the barn. Or the one about the doctor who builds a man out of dead body parts and then lightening … strikes a nearby oak tree. Or that proper British man who wants a proper British nanny for his children and … gets one.

Who knows what’s missing here? Yup, the single element without which all the great characters and wonderful settings in the world won’t take off into a story. What’s missing is an inciting incident.

The characters in a story are sailing along in their “normal world” when something happens. Usually, it is not something the characters do, but something that happens to them, something that jolts the hero out of his everyday routine and lights the fuse of the plot for the whole rest of the story.

In Monsters, Inc, the inciting incident is Boo announcing the presence of a human child in the monster world by picking up Sully’s tail and dropping it. Plunk. After that, life cannot proceed normally for any of the characters.

Before the inciting incident, there is an equilibrium, a relative peace that the characters in a story have grown accustomed to. When something happens that upsets the balance of things, suddenly there is a problem to be solved.

Luke Skywalker in Star Wars sees the holographic message from Princess Leia—“Help me, Obe Wan, Kenobe, you’re my only hope.” And like it or not, Luke is forced to act. He can choose to ignore the message. He can go back and tell the Jawas they sold him a defective droid and demand his money back. Or he can get involved.

Luke Skywalker in Star Wars sees the holographic message from Princess Leia—“Help me, Obe Wan, Kenobe, you’re my only hope.” And like it or not, Luke is forced to act. He can choose to ignore the message. He can go back and tell the Jawas they sold him a defective droid and demand his money back. Or he can get involved.

A tornado picks up Dorothy’s house and deposits it in Oz. Now, like it or not, Dorothy is forced to do something. She can begin life anew in a land populated by short, fat people with squeaky voices or she can find a way to go back home to Kansas. The Frankenstein monster comes to life—now what? Once the “proper British nanny” turns out to be Mary Poppins, can life go on as-is in that household?

Like every other story element, there are great inciting incidents and also-rans. These are some of the characteristics of a great inciting incident.

1. It must grab your reader’s attention. Pull out the stops and make it dramatic, an event with stakes so high Loyal Reader has to keep turning pages to find out what happens.

2. It has to create conflict. When Dorothy’s house drops down on top of the Wicked Witch of the East, that causes serious relational problems between Dorothy and the Wicked Witch of the West. Mary Poppins popping into a proper British household and Boo popping into the monsters’ world turn everything in the characters’ lives upside down.

2. It has to create conflict. When Dorothy’s house drops down on top of the Wicked Witch of the East, that causes serious relational problems between Dorothy and the Wicked Witch of the West. Mary Poppins popping into a proper British household and Boo popping into the monsters’ world turn everything in the characters’ lives upside down.

3. It must generate action. Luke doesn’t just sit there looking at the holographic image of a white-robed woman with brown Honey Buns over her ears. He does something. He tries to help her. Sully and Mike do something—they try to return Boo to her bedroom in the human world.

The inciting incident is the door into your story. Without it, Loyal Reader is left to watch Luke cut doughnuts in the sand, Dorothy milk cows and “Googly Bear” marry the dreadful one-eyed purple Celia with rattlesnake hair.

The inciting incident is the door into your story. Without it, Loyal Reader is left to watch Luke cut doughnuts in the sand, Dorothy milk cows and “Googly Bear” marry the dreadful one-eyed purple Celia with rattlesnake hair.

Write on!

9e

July 6, 2013

What’s Lurking Deep in the Guts of Your Story?

Is your novel about a guy who climbed to the top of the corporate ladder , only to discover it was leaned against the wrong building? So what’s the theme of the story?

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #7 COMPELLING THEME

Elevator doors open.

Woman gets in.

Elevator doors close.

This woman’s got to be a literary agent! She looks like an agent, has that …. agenty thing going on, you know what I mean. Or a publisher. Yeah, agent or publisher, one or the other.

She glances at your The Only Writing Conference on the Planet That Really Matters nametag, then at the title page of the three-inch-thick manuscript you’re clutching to your chest like the seat-cushion life preserver on a 747. She gets it.

“You write that?” she asks.

The woman’s quick! Knew she was an agent. Ok, act like a pro. Give her a this-ain’t-my-first-rodeo glance.

“Write what …? Oh, you mean this? The book? Uh huh, I wrote it.”

“What’s it about?”

Ding! Ding! Ding! The Big Chance alarm begins to shriek in your head so loud it’s hard to concentrate, but you take a deep breath and …

“This is my first novel,” you say, and thrust it at her like a dead fish on a stick. “And it’s about this guy who … well, he and his best friend are on this boat, see. Only it’s not really a boat but they don’t find out it’s not until after the tsunami wipes out the island. Oh, and the guy’s friend is really his twin brother—they were separated at birth—and they don’t know that part either. But they do know they’re both in love with the same woman. Only, she’s got AIDS, which she tells them in the suicide note she leaves beside the safety deposit box key in her pilot’s seat on the Blackhawk helicopter. Anyway, this guy—his name’s Jonah, which I picked because of the boat that’s not really a boat. Jonah—get it? So Jonah turns to his friend and says in Hebrew—”

Elevator doors open.

“This is my floor,” the woman says.

***

Let’s push pause on this little scenario right here. We’ll come back to it later.

Yes, you must have an elevator pitch. You must be able to describe the plot of your book in under 30 seconds. And I’m of the opinion that plot planning needs to start with an elevator pitch and grow from that. (That’s another blog post. http://bit.ly/4ReaderJourney )

But right now, I don’t care if you can describe your plot in 30 seconds. I’m much more interested in your answer to the fundamental question in this scenario: what’s your book about? What’s it really about? And you shouldn’t need an elevator ride to describe it. A sentence or two, maybe just a word, should get the job done.

Is your book about injustice? Intolerance? Diversity? The theme is the point the book makes about those things.

Is yours a book about courage? Sacrifice? Greed? Intolerance? Does it make a point about the nature of man or the influence of culture? Is it about fading beauty, the futility of chasing fame or change versus tradition?

In other words, what is the theme of your book, the universal message that stretches out across your novel? It may appear in the outcome of the story, or in a pattern of scenarios with the same result within the plot, or in the lessons the story teaches. Often there is more than one theme in a novel, but usually there’s an overarching message that knits them all together. Theme may even be directly stated—almost always as an off-hand remark.

One of the themes in Five Days in May popped out of the mouth of the main character, Princess: “Don’t never underestimate the power of doin’ the right thing, Rev. Sometimes, it’s the only gift life gives you.”

I say “popped out” because even if you don’t consciously put a theme in your novel, chances are there’s one in it because theme arises organically from the story. Some writers even start with theme—and I’m one of them. After the theme hijacked Five Days in May, I began my next three novels with a theme in mind.

Black Sunshine is about the destructive power of lies and the healing power of forgiveness—told with the story of a coal mine disaster.

The Last Safe Place is about internal versus external beauty and real change that comes from a transformed heart—told with the story of a deranged fan stalking a novelist.

When Butterflies Cry (releases this fall) is about forgiving yourself and the power of sacrifice. It’s told with the story of a soldier in Vietnam, a disaster in Wales and a mysterious little girl in West Virginia.

Your novel has a theme. If you don’t know what it is, find it. Nurture it. Theme is your truth. Either consciously or unconsciously you wanted to tell that truth to the world—that’s why you wrapped it in a story.

* * *

The woman leaps out of the elevator as if her skirt’s on fire.

The doors close.

Ok, you blew this one. But you know what you did wrong, so next time, you’ll be ready.

The elevator doors open.

A man steps in. Might be in publishing, might be a taxidermist. But you’re not taking any chances. As soon as the elevator doors close, you reach over and punch the emergency stop button.

“Relax,” you say. “This could take awhile. This is my first novel and it’s about this guy who … well, he and his best friend are on this boat, see. Only it’s not really …”

Write on!

9e

June 29, 2013

Three Basics Will Revive Dead Dialogue

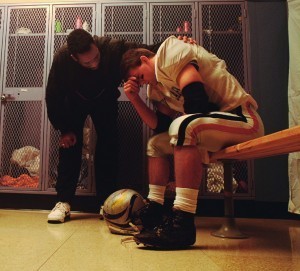

What’s that coach saying? In a gripping scene like this, you can bet it’s great dialogue.

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #6 GREAT DIALOGUE

“You ate my cookie.”

“No, I didn’t!”

“Yes, you did!

“No, I didn’t.”

“You did, too.”

“I did not.”

“Did, too.”

“Did not.”

“Did, too.”

“Not.”

“Too.”

“Not!”

“Too!”

“Not, not, not, not, not, not!”

“I’m telling!”

This exchange illustrates the first requirement of great dialogue—it must sound like people really talk. Unfortunately, it also violates the Alfred Hitchcock principle. The words of the rotund king of cinematic terror are never far from me—they’re written on a plaque above my desk: “A great story is life with the dull parts taken out.”

Mangle his maxim slightly and it can apply to talking on paper: “Great dialogue is speech with the dull parts taken out.”

Dialogue must sound like—defined as comparable to—the way people really talk. Though it will give your story a sense of verisimilitude to construct dialogue exactly like real conversations, the result will have Loyal Reader nodding and drooling in under three pages.

Perhaps this happens to you, too. There comes a point when I’m writing a first draft that the characters start talking to each other. Before that point, they are my creations, mere puppets on a string. But after that point, they take on lives of their own. They know each other and I find they have lots of things they want to talk about. It is then that I say I “transcribe” dialogue rather than write it, typing as fast as I can to get it all on the page. That’s a truly glorious feeling for a writer. However, when I go back through the manuscript on my second draft, I take an editing machete to that dialogue and red ink flows like I’ve sliced an artery. To write good dialogue, you have to freeze dry it. Dehydrate it. Take out all the puffy moisture until the only thing that’s left is the essence, the absolute bare minimum. Then—and this is the best part–you add some fairy dust and make that bare minimum sparkle.

“You ate my cookie.”

“See any crumbs on my shirt? Smell chocolate on my breath?”

“I’m telling!”

“You do that. She’s putting the fuse in a car bomb. She’ll appreciate the interruption.”

This reconstructed exchange serves the dual purpose of illustrating the second requirement of great dialogue, too—it must move the plot forward. What your characters say must matter to the action. It needs to advance the story, tell us something we didn’t know about what’s happening. There’s no place for “chatting” in a novel. Every word of dialogue must serve a function or you must mercilessly cut it out.

Of course, it’s acceptable for your dialogue to look like it’s chatting, when in fact it is serving the third function of great dialogue—revealing something about the characters involved.

“You ate my cookie.”

“No, I didn’t. I’d never do a thing like that.”

“I’m telling.”

“No! Oh, please, don’t. Ok, I took it–but I’m sorry. I’ll get you another cookie. I’ll bake you a dozen more cookies. A barrel full of cookies. Just don’t tell! You know what Cookie Monster’s like when he gets angry.”

Great dialogue sounds like people talk, advances the plot and reveals character. And best of all, you already know how to use it. You’ve been practicing dialogue your whole life. So listen to yourself. Listen to the people around you. What is it about one person’s speech that’s distinctive? And particularly if you’re writing dialect—what is it about the sentence construction that defines the region? Read great screenplays—they’re almost nothing but dialogue. And read Hemmingway; he was a master.

There are boatloads of never’s and always’s regarding the use of dialogue and I told myself I wasn’t going to go there. But allow me just this one, please. This word usage is as irritating to me as Justin Bieber. (No, nothing is as irritating as Justin Bieber. Either his hair is on backwards or his head is.) NEVER use an adverb to modify the word “said.” Put another way, if you need an adverb to make the dialogue understandable to Loyal Reader, what you need more is to go back and rewrite it. Adverbs modifying “said” are, at the very least, redundant and at worst totally ludicrous.

“Do that one more time and I’ll break your arm off and beat you to death with the bloody stump,” his mother said menacingly.

“Drop that AK47 right now,” the Navy Seal said forcefully.

“You’re in a good mood—must have run over a nun on the way here,” his persnickety aunt said sarcastically.

“I feel so bad for Waldo. I can’t believe his parents named him ‘Where’s,’” his blonde date said dumbly.

“That thing on your face isn’t a mole—it’s a Milk Dud,” the bully said mockingly.

‘Nuff said. Next week, we will talk about theme.

Write on!

9e

June 21, 2013

Do the Unexpected: Twist & Turn Your Plot

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #5 TWISTS AND TURNS

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #5 TWISTS AND TURNS

zzzzzzzzzzzzz …snort, cough ….

Oh, hello. It’s you. Sorry about that. I was reading a novel where everything turned out exactly like I thought it would and I dozed off.

#5 in the Ten Elements of a Dynamite story is “unexpected twists and turns”—in characterizations as well as plot. Very little will kill your novel quicker and deader than predictability. Story in any form—novel, television show, movie, cave painting–is best served piping hot, spiced liberally with surprise.

Consider:

So we’re sailing along through Finding Nemo when Marlin and Dory encounter three hungry sharks.

What should happen next? Crunch. Gulp. Marlin and Dory slide down the nearest gullet on a fast track to shark guano.

What does happen? The sharks, Bruce, Chum and Anchor have formed something like Carnivores Anonymous and have sworn off eating fish.

So a young man from a small town helps a beautiful princess save her people from an evil villain. They conquer the bad guy, fall in love in the process, get married and live happily every after.

You asleep yet?

But what if the young man turns out to be the twin brother of the beautiful princess? And the evil villain is their father? Throw in a master warrior who’s a green, cupie-doll-looking dude the size and shape of a fire hydrant, a mercenary whose best friend looks like Sasquatch and a robot without a line of dialogue whose beeps and squeaks steal the show and you have an edge-of-your-seat rather than a nod-off-and-drool story. George Lucas would be proud of you.

Every television doctor who’s graced the screen since Ben Casey and Dr. Kildare has been kind, gentle and self-sacrificing. House works because he’s a jerk.

Did you ever dream George would shoot Lenny in the final scene of Of Mice and Men? That Othello would strangle his own wife? That the three-eyed-green aliens from the machine at Pizza Planet would save all the other toys from a fiery death?

Predictable is booooring. If your story is going to hook Loyal Reader and drag him into the action, it better be a story that keeps him off balance, a story where he can’t begin to imagine what happens next.

So how do you craft stories with unexpected twists and turns? Learn from the masters: don’t start with stock characters. Ken and Barbie only work for five-year-olds. Need the driver of an 18-wheeler in a cameo role? Forego burly, hairy and tattooed in favor of blonde and petite. (Actually, Barbie might work here.)

My favorite technique to add spice to a plot is the imagine-the-worst method. Your characters are doing splendidly—which is the point right before Loyal Reader goes comatose. So ask yourself, what is the absolute worst thing that could happen right now? John is down on one knee about to propose to Mary–what’s the worst-case scenario here? Mary says no, she’s dying of a horrible disease and by the way, John’s got it now, too. His wife shows up with their quadruplets. Her ex-husband shoots John, and Mary gets beamed into the 14th century? The moon rises and John turns into a werewolf. The sun comes up and Mary leaps into a convenient coffin.

You have to keep the “unexpected” rubber band pulled tight all the way through your tale. Every scene must surprise the reader in some way, while remaining tethered to the reality of the plot. Which means you must lay a groundwork of hints, like breadcrumbs tossed out to lead the reader to the climax. When you yank him in an unexpected direction, you want Loyal Reader to think: “Oh…THAT’s why …”

Which brings me to Dan Brown’s newest release—Inferno. Don’t read it without a neck brace handy, the plot twists in the story will give you whiplash. Perhaps even more artfully than Brown’s other books, Inferno is a study in the unexpected, where nothing that happens is what it seems and none of the characters are fighting on the side you think they are. If you haven’t read Inferno, perhaps you should. It demonstrates how to tangle up a plot like last year’s Christmas lights.

But I have to admit that by the time the switcho-chango elements in the book began to kick in, I was too brain dead to fully appreciate the effect. After roughly 5,500 (conservative guess) intricately detailed descriptions of artworks/historic buildings/long-dead rulers/popes/artists, I only had a handful of synapses still firing. Unfortunately, Inferno is also a case study in allowing the setting to hijack a book, an example of how to get so carried away with grandiose descriptions (to show off what an expert you are) that you totally lose sight of the fact that Loyal Reader just flat doesn’t care.

Let that be a learning experience for you, too.

Next week, #6: Dialogue

Write on!

9e