Ninie Hammon's Blog, page 5

March 29, 2013

How To Survive Success As a Novelist

That’s me at a book-signing. The line stretched out so far I couldn’t see the end of it. Good times. At my next book-signing, I sat in a bookstore for two hours and not one person even glanced my way.

STEP FIFTEEN

I considered adding a subtitle: I’ll Let You Know As Soon As I Have Some and then leaving the space below blank.

Might have gotten a chuckle, but it’s not accurate. I have had success as a novelist and hope/plan to have even more in the future. Want to know why—my secret? Easy. I’ve had success because I know what success is. The question is: Do you? Just as important: Are you willing to do what it takes to get there?

Seems like a no-brainer, but it’s important to ask yourself what success as a writer means to you. Is it making the New York Times Bestseller List? Is it earning enough money so you can quit your day job and write full-time? Is it publishing a book even if the only people who read it are your mother, your best friend and that blow-hard on your bowling team who’s been saying for years you’d never finish it?

You have to decide for yourself what success looks like for YOU. It might very well be quite different from what success looks like for me. And you need to figure it out early in your writing career rather than late. Do it now. It’ll smooth out some of the bumps in the road later on.

If success for you is writing for the sheer joy of it with the hope that one day you’ll publish it, maybe to hand down to your children—then how you write, when you write, and what you do with the rest of your time will be quite different from the how, when and what of someone determined to write a bestseller.

Because if you plan for your book to be a bestseller, you have to knuckle down RIGHT NOW and conduct your writing career like a business. It IS a business. And you have to treat it like one from the git-go or you’ll soon be declaring Chapter 11 for your little enterprise and all your dreams of a successful writing career will go belly-up with it.

You don’t want to run a business, you say? You plan to write the Great American Novel and it will be such a breath-takingly profound work of art that literary agents and publishers will fight over the rights to it like sharks that smell blood in the water?

If that’s what you believe, I have two words for you: wake up.

Publishing doesn’t work that way. Hold onto your shorts, Mildred, cause I’m about to drop a bombshell on you: the quality of your work has very little to do with your success as a novelist.

Chew on that for a minute.

You see, the world of publishing has changed more dramatically in the past decade than in all the five-plus centuries since Johannes Gutenberg first put paper in a press. I don’t have space to explain it all here. If your goal is to earn money as a writer, you will have to go online and find out for yourself. But suffice it to say that a first-time novelist landing a book contract in today’s publishing climate is about as likely as successfully milking a chicken. And even if you did, the days of a novelist merely writing while his publisher does all the heavy lifting have gone the way of the buggy whip and cassette tape players.

Write this down: if you want to make money as a writer you will HAVE TO market your book yourself. A traditional publisher expects it; epublishing a book demands it.

You do marketing and badda bing, badda boom–you’re a business. Simple as that. If you want your business to thrive—to survive!—you will have to work as hard at setting goals, making strategic plans to reach those goals and learning the ropes of book marketing as you work at writing.

Don’t misinterpret what I’m saying. NOTHING is as important as writing a great book. It is your highest priority, your passion, your great love. Unless you write a great book, none of the rest of this matters. But the simple reality is that you will have to devote time, energy and brain power to the SECOND most important part of being a novelist—business savvy. Skip that part and your book’s toast.

The how-to is all out there on the internet. Go find it. There’s no secret formula. You just have to roll up your sleeves and get to work.

Think about how much your book means to you, how hard you worked on it, how you poured your very soul into it. You should be willing to crawl through two miles of broken Coke bottles and rusty razor blades to get that book into the hands of readers.

You can do this!

Blessings!

March 7, 2013

If You Have A Song to Sing, SING IT!

Perhaps this should have been the first post instead of the 14th out of 15. It is, after all, foundational to everything I have come to understand about writing in general and the writing of novels in particular.

It has to do with music. Sort of.

Let‘s have a little truth in advertising here. I am not a musician. I can strum a D chord on a guitar and whistle–that’s the extent of my musical ability. There are wonderful musicians in the family. My husband is incredibly gifted, could have been a professional jazz guitarist. Sons are all musical in one way or another; daughter majored in piano performance in college.

I am the weak link. The un-musician. But even though you don’t want me on your team for Name that Tune, a music analogy is the clearest way to explain my point.

For the 25 years I made my living as a minion in the “the working press,” I defined my job as “concert pianist.” I wrote thousands of news and feature stories and penned more than 1,200 weekly columns in those years. I developed, nurtured and clarified my writing voice (though at the time, I didn’t realize I was doing that) and perfected the art—and it is an art!—of writing under deadline pressure. And every word I wrote was a note from somebody else’s musical score. I spent my career telling somebody else’s story, playing somebody else’s music. I either told the story well and brought the people and events to life on the printed page, or I told it poorly and bored my readers into skipping to the classified ads or the obits. But either way, it was never MY story.

During all those years, I was a voracious reader, went through novels like Sherman marching through Atlanta. I absorbed story and form, characterization, timing, building suspense—like chapped skin soaking up hot oil.

And the answer to the question you haven’t asked yet is yes. Yes, I did wonder. As I spent the golden years of my working life singing other people’s songs, now and then I would stop to wonder—did I have a song to sing? Is it possible that instead of being a concert pianist I might actually be a composer?

But there were bills to pay and kids to raise and I made a living as a journalist and … Ok, truth—I didn’t ask the question because as long as I didn’t ask it, I didn’t have to find out that the answer was no. And deep down, I so wanted the answer to be yes. I so wanted to believe that somewhere inside me, there was, indeed, a story of my own.

Then, in 2006, my husband was asked to supervise Young Life in the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scandinavia—and we moved to England! I walked away from the editor’s job at a thriving newspaper I’d founded and just like that, badda bing, badda boom, my journalism career was over.

But I had written—something!—every day of my life for 25 years and after a month of not writing, the words started to back up in my brain like a clogged sewer. It became a life-and-death situation quick. I could either write or have a stroke. So I wrote. A book. Yep, a book. And another. And another.

You know what I discovered? I didn’t have a song to sing. I had a whole symphony! I had so many songs bubbling up I couldn’t keep track of them all. Story ideas chased each other around in my head like squirrels playing in the trees and I couldn’t get the words down on paper fast enough.

It has been that way ever since. If the well ran dry tomorrow, I’d have enough story ideas to write for another 50 years.

So what, the dear reader is wondering, is the point of this post? Poignant though the story may be, how does it relate to the Fifteen Steps To Get That Novel Out of Your Head and Onto the Page?

Simple. I tell you my story so you can learn from it and not make the same mistake. Don’t settle! If you have any inkling that you have a song to sing—sing it! Sing it loud and off key until your learn the melody. But SING. Don’t settle for listening to other people’s music—write your own. Do it NOW! Don’t wait until some fortuitous circumstance makes it possible for you to write—CREATE your circumstance. Ask the question! If the answer’s yes, you’re in for quite a ride!

We’re almost done here. This is Step 14 of 15 and I hope each step has given you practical tools to help you sing the song that’s in your heart.

BUT… (You could hear a “but” coming, couldn’t you.) Step 15 won’t show up on Thursday next week as all the other steps have done for the past 14 weeks. That’s because I won’t be here to write it. I’ve been faithful to my commitment to a weekly blog since September 1, 2012. But for the next two weeks I WILL BE IN ISRAEL!! Yep, I’m going to the Holy Land, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Laptops and internet and blogs and …and everything else, will just have to wait until I get back.

Look for my blog here the week of March 24. I’ll give you the final step…and SURELY I’ll have a story or two to tell.

February 28, 2013

Set It Free! No Little Dogs.

My mother was an artist. Though she passed through water colors, oils and acrylics on the way, she found her home in pastel chalk—not an easy medium. So many of my childhood memories center around my mother creating form and beauty on a blank, white page. On hot summer afternoons, I’d sit on a straight-back kitchen chair beside her as she worked, both of us lost to the world’s time. I’d watch shadows from the ceiling fan march resolutely across the floor and stare in fascination at azure, crimson and emerald dust filtering down through the beams of sunlight that stuck like flaming arrows in the floor.

She spent untold hours on each painting, worked with pieces of chalk the size of her thumb but somehow managed to create astonishingly small details—a bee on a flower in a picnic painting, individual faces of a whole crew of men on a Spanish galleon. She was a tireless perfectionist. I’d watch her cock her head to the side, shake it and then rub the chalk off down to the bare paper on some spot on a painting that wasn’t working, do it over time and time again until she finally had it like she wanted it.

She used some kind of spray on her paintings to seal the chalk in place when she was finished. She’d evenly cover the surface of the piece of artist’s paper on her easel, slowly, like she was applying a fine coating of spray paint. Then she’d step back and look at it, study the whole work from a different angle. I knew what was coming then. It happened countless times, the same scene played out from one painting to the next, again and again.

A pleat of concentration would staple itself between her eyebrows, she’d get a kind of puckery little frown of vexation on her face. Then she’d point to some bare spot in the painting and say some permutation of the following.

“You know … right there, I could have put a little dog (tree, boat, child, reindeer, octopus, glacier—you get the idea).”

And she’d be melancholy for days afterward, saddened that she’d thought of something she wanted to add to the painting when it was too late.

I asked her about it once, why she always wanted to change the painting when it was obviously finished and she stared at me like I wasn’t her child at all, like I was some creature assembled from spare parts in the garage.

“Oh, no, the painting isn’t finished, dear,” she said. “A painting is NEVER finished.”

I had reporters with that same mindset when I was in the newspaper business. I’d tell them it was deadline and I had to have their stories, but there was always “one more change” they had to make. Then when the pages were laid out to proof, they didn’t just want to correct errors—typos, misspelled words, attributions. They wanted to rewrite whole paragraphs.

That’s why what we talked about last week is so important. Printing your manuscript out in book form will allow you to see the changes you’ll want to make in it once the book is published—but you’ll still have an active manuscript to work on.

Even using that method, however, there comes a point when you have to let your story go. You’ve worked on it for months—maybe even years—but when it’s time to set it free, you need to do that. It will be harder than you think, the letting-go part. Not as gut-wrenching as sending your firstborn off to kindergarten, but painful in a way you shouldn’t waste your breath trying to explain to a non-writer. This offers no consolation whatsoever, but you need to know it feels just as bad with your seventh book as it did with your first.

But set it free you must. And once it’s lying there in your hand, covers on the front and back and your name in big, bold type—no little dogs! Ok? Those puppies will drive you daft.

Are there particular things you always seem to want to change once your novel’s been published?

February 21, 2013

Watch Your Novel Go From Caterpillar to Butterfly

It happened to me with my very first novel. I got it in the mail, shipped to my house in Godalming, Surrey, southwest of London, and for a full half hour I did nothing but stare at the cover. Not the art or the title—MY NAME on the front.

Then I opened the book almost reverently and started to read the first chapter. Three paragraphs in and I was silently shrieking. Three pages in and the shrieking was no longer silent. I never made it to the end of the chapter.

You see, every sentence needed work! The construction was so clumsy—why didn’t I see it?—and that transition … seriously? And it was too late now. I couldn’t fix it. There it lay in my hand, a dead pigeon, and there’d be no breathing life back into it. To this day, I have never read my first novel.

So what happened? Why did everything seem to need re-writing? (No, it didn’t just seem to need re-writing; it did need re-writing.) I had edited the manuscript over and over, polished it the best I possibly could before I sent it off to the publisher. Why couldn’t I see before it was published what was so in-my-face obvious afterward?

Let me run off down a rabbit trail for a bit. I’m sure you’ve all heard repeatedly that you should read your manuscripts out loud. Oh, how I hope you have taken that advice to heart. It makes a surprising difference. When newbie reporters used to ask me why I made them do it, I told them, “Your eye sees what you meant to say, but you ear hears what you really did say.”

I suspect that the mind plays a similar trick when you’re editing a manuscript. After you’ve gone over it countless times, you really do see on the page what you meant to say. But when the book shows up in a box on the porch, you find out what you really did say. Usually, the distance between the two is big enough for a sperm whale convention.

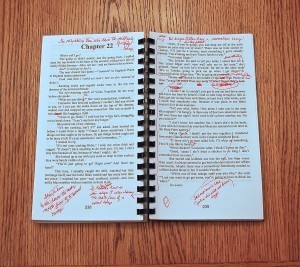

After I figured out what the problem was, the fix was relatively simple. If you can’t see the mistakes until the book’s printed … duh—print it! Now, on the fourth or fifth edit, I format the manuscript in book layout, take it to Kinkos and have it printed out. (It costs $31 and you can claim it as a business expense on your taxes.) When I open that “book” and start to edit, mistakes leap out at me like little kids yelling “Boo!” on Halloween. You can see in the picture above the red ink on one of my book-formatted manuscripts. There’s enough blood on those pages to attract sharks!

Aside from clumsy wording and awkward sentence structures, you’d be amazed at the things I catch that had blown by me through half a dozen previous edits.

I flipped through a couple of book-formatted manuscripts and found these gems:

*She whimpered like a baby rabbit … do baby rabbits make whimpering sounds?

*He has a mustache like Pancho Villa … did Pancho Villa have a mustache?

*A “looney tune triple dipped in psycho”? Please!

*What color are satellite dishes in Eastern Kentucky? Black or white?

I often have to print the book format several times. Editing is like combing tangles out of wet hair—you just keep combing until they’re all gone. Some manuscripts have more snarls than others and I don’t stop until the “book” I’m working on has only a few drips of crimson.

Printing it out makes possible that final transition, helps me transform my caterpillar manuscript into a butterfly.

Once the edits on that last book are complete, there’s only one more thing to do before I hand the manuscript off to the publisher—for more editing and proofing. Just one final step before I hit “send.”

And we’ll talk about that one next week.

Do any of you have tricks of your own that help you better edit your manuscripts? I’d love to hear about them.

February 15, 2013

Label ‘Em or Lose ‘Em

Don’t have a stroke trying to figure out why this picture is here. This pumpkin really doesn’t have anything to do with labeling. But it does bear a striking resemblance to the look I have on my face when I can’t find the most recent version of my manuscript.

STEP ELEVEN

So you’re going to write a novel. You sit down and type the title: “The Greatest Book Ever Written”. You slug it, “By Ninie Hammon,” and you’re off to the races. First day 500 words. Second day 750. After a few weeks, you’ve cranked out 35,000 … maybe 50,000 words. You’re feeling pretty good about your progress, so good, in fact, that you decide to make a major change in the plot, and you go happily off down that rabbit trail. But that new plot twist doesn’t work out and you realize the book was much better the way it was. Only the “way it was” doesn’t exist anymore. It vanished when you hit “save” on the day you chased the rabbit.

Or you cut out a scene, then figure out you can use that scene later in the book. But the scene’s gone, of course. It went the way of the buggy whip when you saved the manuscript the day you cut it out.

Or perhaps the reverse is true. Maybe you’re afraid to cut anything at all because you might need it later, so every day you save different versions of the manuscript. You call the version that remains unchanged the Old “Greatest Book Ever Written” and the version you changed the New “Greatest Book Ever Written.”

Using that technique of labeling manuscript versions, by the time you have 110,000 words, you’re trying to keep track of the Old, Old, Old, Old “Greatest Book Ever Written” and the New, Newer, Newest, Newest-Newest…

You get the idea.

The point is that you have to have a system of keeping track of different versions of your manuscript. When I was writing my first novel, I got so confused it was maddening. I’d be editing what I believed was the latest version of the book only to stumble upon a sentence I was sure I’d already rewritten, or a mistake I was certain I’d already corrected.

Like everything else I know about the nuts and bolts of writing a novel, I figured this one out for myself. I’m sure other writers have other systems, but this one has served me well through six novels.

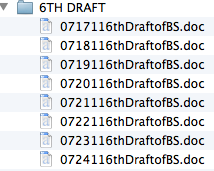

Day One on a new book, I make a folder called Crappy First Draft. When I’m finished writing for the day, I name the manuscript “021613CFDofWBC.doc,” and put it in the folder. The first six numbers are the date. We know what CFD means and WBC is the book title When Butterflies Cry.

Day Two on the new book, the FIRST thing I do when I call up the 021613CFDofWBC.doc document is change its name to 021713CFDofWBC.doc and save it … which leaves the previous day’s work untouched. By the time I’m finished with the CFD of a book I have 35-50 different versions of the manuscript, EACH of them dated and labeled. Then I start a second folder labeled 2ND DRAFT and label the first document in it 0218132ndDraftofWBC.doc. Depending on how many drafts the book requires, I could have folders for the 6th, 7th, 8th drafts—each of them full of dated versions of the manuscript.

This is a screen shot from the 6th Draft folder of Black Sunshine.

Using this labeling method, nothing I write is ever lost. With a little digging, I can find that scene where I wrote a great description of an explosion or an eclipse, or a train wreck, or the version of the manuscript where the little dog gets hit by a truck. I never have to wonder which version is the latest—they’re all dated.

And as an added bonus, this labeling method makes one of my favorite writing traditions possible. When I get the first printed copy of my latest book, I open it to Chapter One and read aloud the first page. Then I pull up the first CFD document of the manuscript and read the first page out loud. It’s funny, of course, to compare the two. But it’s encouraging, too. The memory of it helps me over the hump when I’m hacking my way through the CFD of the next book. It reminds me to chill out—almost nothing I’m writing will be there in the finished product.

February 8, 2013

Look for this ad in Publisher’s Weekly! The Last Safe Pla...

Look for this ad in Publisher’s Weekly! The Last Safe Place…coming soon to a jungle (Amazon) near you! Releases April 1, 2013. Ebook available NOW!!!

[image error]

February 7, 2013

The CFD–Crappy First Draft

Years ago, a famous columnist from a big metro daily and I co-taught a session on column-writing for the Kentucky Press Association Boot Camp. His approach to the craft and mine could not have been more different.

Bob described how he worked on his lead, probably spent a third of the time it took to write the whole column working on that one sentence. Then he crafted and polished a second sentence and hooked it to the first. And then a third. He worked his way through the column that way, paragraph by paragraph so that when he typed the final word in the last sentence, the column was finished.

I didn’t work that way. I described how I sat down at the typewriter (if you’re younger than 40, Google it. There will be pictures.), closed my eyes and started writing. I didn’t stop writing—not for missing information, grammar problems, misspelled words or anything else—until I was completely finished. But when I typed the final word in the last sentence, I was only at the end of the beginning. What followed was a 2nd draft, a 3rd, a 7th, a 12th… however many it took to polish that rough first draft into a column ready to publish.

Though it’s not my style, it’s easy for me to understand how a journalist could write a column the way Bob did. It’s far harder for me to understand how a novelist could write a book that way—and there are some who do. The difference, of course, is story.

Which brings us to the CFD. The Crappy First Draft. (Writers whose sensibilities are not as delicate as mine call it the SFD. I don’t think I have to translate.) When I write a CFD, I write it the same way I wrote columns years ago. Though it takes months rather than hours, I write as hard as I can go—ignoring mistakes or problems—until I have set down the whole thing. Then I go back over the manuscript again and again, like combing the tangles out of wet hair, until it is as perfect as I can make it.

The reason I have trouble understanding novelists who write books like Bob wrote columns is that the FIRST thing I get down on paper is THE STORY. I tell it fast, with as much energy and power as I can, letting it flow out of me raw and untamed onto the page. Polishing the prose, adjusting characterizations, rearranging scenes—all that comes later. If I stopped to do that as I went along, I fear the pacing would bog down in the language, the tone would be turgid and stodgy, and I’d so muddy up the tale there would be no resurrecting it. I fear the story itself would get lost. No story, no novel.

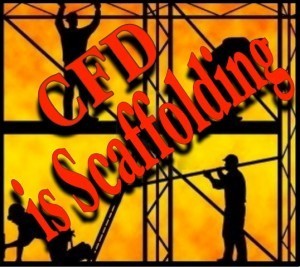

Over the course of eight books, I have come to see the CFD as scaffolding. It is the framework I set in place before I do anything else. Then I come back and use that framework to build the Eiffel Tower, The Taj Mahal, The Sistine Chapel … or a ramshackle hovel in the mountains of West Virginia.

Because I write until I run out of breath, throw in a semi-colon and keep going, I am dependant on my Working List—one list to rule them all—to keep track of all that must be fixed in the 2nd draft. In the CFD, I use the word “blank” dozens of times:

Grayson hopped into his blank and drove away. (Later, I’ll research cars built in 1969 and decide whether he’d drive a sedan or a convertible or a station wagon.)

Aaron froze when the music started. The band was playing blank. It had been Susan’s favorite song. (In the second draft, I’ll go to my list of songs from 1969, find a particularly poignant one, maybe even have Aaron mouth some of the lyrics as he listens.)

When I write the CFD, I avoid anything that will slow me down, anything that will hinder the flow of words onto the page. French author Guy de Maupassant said it best. His advice to fledgling writers was simple: “Get black on white!” That’s the purpose of the CFD.

Soooo, you ask, are we ready to write now? Are we? Are we? Huh, huh, huh?

Nope. Not yet. But soon, very soon. AFTER we learn in coming weeks how to keep track of changes over the course of 6-10 drafts, how to do those final edits … and how to set your novel free. (All coming soon to a blog near you.)

January 31, 2013

All Great Stories Are About Change

As the story opens, Gandalf the Gray provides the entertainment for Bilbo’s birthday party. He sets off fireworks—his specialty. Three books full of outrageous adventure and 1,000+ pages later, the bearded wizard emerges as Gandalf the White, fearsome, wise, stronger than Saruman and the Balrog.

Over the course of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Gandalf changed.

The narrator Amir in The Kite Runner is a spoiled rich kid jealous of Hassan, the “servant” he never calls friend. By the end of the tale, he risks his life to save the son of his “brother” Hassan.

Amir changed.

The black maid Aibileen in The Help, who is raising her 17th white child, never aspired to any other life. But as she writes down her stories for Miss Skeeter, things begin to shift inside her and when she loses her job because of what she has done, she is willing to countenance grander possibilities. “Maybe I ain’t too old to start over,” she thinks, laughing and crying at the same time.

Aibileen changed.

All great stories are about change. All good stories are about change. In fact—you heard this coming, didn’t you—ALL stories are about change. If nothing changes, nothing happens and there is no story to tell.

I’m not here to convince you that you need change in your story, or to teach you how to incorporate it into your tale. What I can help you do, however, is keep track of it. I can show you how I do it and you can devise your own system from there.

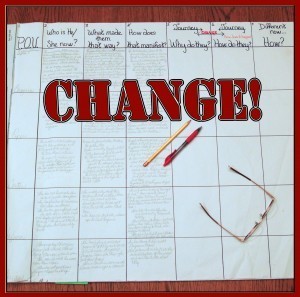

As you can see from the art that accompanies this post, I use a chart on a large tablet of butcher paper to plot/track change. I fill it out as I’m planning my novels. But be forewarned: not one of my seven books has EVER turned out exactly the way I plotted it on this chart. The chart, like most of my other systems, is just a jumping-off place. My first drafts never line up with it.

That’s ok. No, it’s more than ok. It’s the nature of creativity that it will ultimately take your story to places you never planned and to insights you didn’t even understand yourself when you began.

But my eternal maxim still holds: You have to START somewhere.

This is where I start, how I focus on the changes that will take place within my characters over the course of my story.

I list my main characters down the left side of the chart, then fill in for each of them information under six headings listed at the top:

1. WHO IS HE/SHE NOW? More than just shy, cheerful, angry, arrogant or psychotic. What are their demons? What are their odd quirks of behavior? What wakes them up at 2 in the morning?

2. WHAT MADE THEM THAT WAY? Did he witness his father’s suicide? Was she molested as a child? Was he responsible for his little sister’s death? Was he the kid who never got picked on the playground?

3. HOW DOES THAT MANIFEST? Is she terrified of men? Is he plagued by nightmares and sleepwalking? Does she suffer PTSD? Is he totally lacking in self confidence?

4. THE JOURNEY: WHY DO THEY CHANGE? Does he save another child from drowning? Does she go to therapy? Does he find God? Does she witness the unlikely sacrifice of someone else?

5. THE JOURNEY: HOW DO THEY CHANGE? How does it happen? Does she finally say “yes” to her childhood sweetheart? Does he forgive his brother? Does she step out and take the job or walk away from a bad relationship or buy a boat and sail to Bali?

6. DIFFERENT NOW…HOW? Is she finally at peace? Is he able to laugh at himself? Or stand up for himself? Or forgive himself. Does she finally have the confidence to do her own thing?

It’s important to me as a story-teller to make the changes in my characters clear to my readers. It’s just as important to make those changes BELIEVABLE. At the end of your book, if Joe’s willing to commit to a relationship when he was a hopeless player in the beginning, or Mary’s able to forgive her uncle’s abuse when she started the story plotting revenge, you HAVE to make those changes plausible. This little chart helps me do that.

January 25, 2013

One List to Rule Them All, One List to Find Them

One list to find them.

One list to bring them all and in your novel bind them.

In the land of fiction where the writers lie.

I guess I owe an apology to a certain J.R.R. Tolkein, but the imagery was too good to pass up. The One List isn’t gold, with flaming Elvish engraved in its shiny surface. But it is a list that rules them all—all the other lists, that is.

I think of it as a list because that’s what it was when I wrote my first novel. It was the list of all the other lists. Now the “one list” is a folder named “Working List” in my novel file. That folder contains all the information I need to write. Some elements are the same in every novel; others are specific to a particular book.

I know writers who use 4X6 cards in file card boxes for the same purpose and I’m sure there are other ways other writers accomplish the task of accumulating, sorting and storing information. This is how I do it. An example’s worth at least 500 words:

These are the documents in the Working List for my WIP When Butterflies Cry:

1. CHARACTER TIMELINE. I talked about this last week. It’s the document where all the characters are named and the important events in their lives set out in chronological order.

2. IDEAS/PLOT. You’ll find as you write, you’ll come up plot elements you didn’t think of at first. Novels GROW. You don’t set out a plan and write the book without varying from that blueprint. As you write, you think: maybe Mr. Warren has a handicapped daughter that he dotes on. Or maybe Carter comes out of the woods with his rifle just as the sheriff is telling Piper her brother has been shot.

3. ALWAYS ALWAYS LANGUAGE. This is the list of cool language usage I talked about in a previous post.

4. GO BACK AND FIX. I use this list more than any of the others. When I get to page 27 or page 130 or page 150 and realize I need to “go back and fix” something earlier in the manuscript, I jot it down here rather than constantly backtracking to make changes. By the end of the first draft, I might have 50 to 75 items on the list. In the second draft, I will fix everything in the list from the first draft. In the third draft, I’ll fix everything from the second draft, etc. For example:

*On Thursday, before Carter plays with Sadie, he needs to have “last talk” with his mother.

*Mention often that Sadie sucks her thumb so isn’t odd she does it in climax scene.

*Put in the Grayson hunting scene that he got his gear out of shed in the back, so Carter can plant evidence there.

5. FIND OUT. Particularly in the first draft, I don’t spend time looking up things I realize as I’m writing that I need to know. I just type the word BLANK in the manuscript and keep writing. Things like: How many soldiers are in a platoon? When was the full moon in June, 1969?

6. FIND A PLACE. This is for cool information you’d like to work into the plot somewhere, like the fact that because of inbreeding, there really were people in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky whose skin was a purple shade of blue.

7. CUT OUT AND PUT BACK. You’ll find some scenes don’t work and you end up cutting them. I always paste them on this document so if I need to, I can use them or pieces of them later on.

8. ORIGINAL PLOT SYNOPSIS. This is the diving board I use to jump into the novel.

9. 1969. My book is set in 1969 so this list contains a wealth of information: who was president? What was the most popular song? Were there computers? What did cars look like? What was the box office hit movie?

10. WEST VIRGINIA. My book is set in West Virginia. This document lists maps, flowers, trees, birds, politicians, important events of my locale.

11. POSSIBLE BOOK TITLES/CHARACTER NAMES.

12. VIETNAM WAR AND BUFFALO CREEK/ ABERFAN, WALES DISASTERS. These are specific to this particular novel. One of the main characters comes home from the war; the two disasters are part of the back-stories of other characters.

As is obvious from the definitions, some of these lists must be completed before you begin writing. Others are added to almost every day as you write.

Speaking of writing … are you ready to begin yet? Nope, there are a few more things you need to do first that we’ll talk about next week.

January 16, 2013

What Were They Doing When?

I’ve said it before but it bears repeating. Starting a new novel is a front-loaded activity. Every novelist does it differently, but only a handful sit down at the keyboard and type: “It was a dark and stormy night…” without a clue where the story’s going after that.

I’ve said it before but it bears repeating. Starting a new novel is a front-loaded activity. Every novelist does it differently, but only a handful sit down at the keyboard and type: “It was a dark and stormy night…” without a clue where the story’s going after that.

After you have written your logline, synopsis and treatment, you’ve completed your list of necessary scenes and you’ve even clipped pictures of your characters, you’re ready to … START WRITING??? Nope. You’re ready to set out your character timelines.

Simply put, you make a list of your major characters and map out the important events in their lives. When were they born. When did they graduate from high school? When did they get married? Have children?

Why go to so much trouble? Because it will save you a ton of trouble later on and keep you from making embarrassing mistakes.

A picture’s worth a thousand words, so here’s a cut-and-paste of the character timelines from Black Sunshine.

1. Will Gribbins—38

1963 Born

1970 Mother, Winona Calhoun, runs off with truck driver—5

1978 Father diagnosed with black lung—7

1978 to 1981 raised by Granny and Bowman 7 to 18

1981 Survives Harlan #7 explosion—18

1981 Joins Navy—18

1982-1990 Aircraft carrier—19 to 27

1987—father dies of black lung—24

1990—leaves Navy, work on oil rig coast Texas—27

1991—fired from oil rig job for drinking—28

1991-1998—painter, carpenter, farm worker—loses jobs—28-35

1998—first goes AA, still got a watch—35

1998-2000 homeless, booze and drugs, lives under bridge—35-37

2000—starts going to AA regularly—37

2000—back for 20-year Memorial Service Harlan #7 explosion—38

2. Granny (Ruby Lucille Johnson) Sparrow—76

1925 Born

1940 Marries Bowman Sparrow—15

1942 Daughter Stella born—17

1944 Daughter Ruth Ann born—19

1948 Daughter Charity born—23

1956 Son Ricky Dan born—31

1959 Stella (17) marries Bobby Mattingly—34

1960 Stella’s daughter Laurie Ann born—35

1962 Daughter Ruth Ann (18) marries Jody Simpson—37

1963 Ruth Ann’s daughter Della born, Stella’s daughter Dreama born (Granny had 3 granddaughters before age 40)

1964 Daughter Charity marries Clive Shepherd.

1965 Charity’s twin daughters Ruby and Marilou born.

1966 to 1980 Three daughters have five more children, two boys, three girls for a grand total of 9 girls and 3 boys

1981 Husband Bowman, son Ricky Dan, brother Ed, son-in-law Jody Simpson killed in Harlan #7 explosion—56

1981 Twin grandchildren Jamey, JoJo born—56

2001—Memorial service—75

3. Ricky Dan Sparrow—died at 18

1963 Born

1981 Girlfriend Joanna Darlene Dudley gets pregnant

1981 killed in Harlan #7 explosion—18

1981 Girlfriend Joanna killed car accident

1981 Twin children Jamey, JoJo

4. Jamey Sparrow—19 (mentally about 9 years old)

1982 Nov. 27 Born

1987 Gets canary ValVleen—5

5. JoJo Sparrow—19

1982 Nov. 27 Born

1997 quits school to marry Darrell Holland—16

1997 Darrell killed in mining accident—17

2000 Engaged to Avery Duncan—18

2000 Jesse busted for selling Oxycontin, sentenced to 15 years—18

2001 decides commit suicide before turns 20—19

6. LLoyd Crowder—38

1963 Born

1970 father beats him—ages 7-15

1972 to 1981 gravitates to Granny and Bowman ages 9 to 18

1981 Survives Harlan #7 explosion—18

1982-Marries Betty Ann Phelps—19

1983—Son Jesse born—20

1984—Daughter Amy born—21

1982-1991—drunk, lousy husband, father 22-28

1991 Sees movie The Mission (1986 movie)

1991—starts going Pentecostal church (Jesse 6, Amy 5)

2000—17-year-old son busted for drugs—37

2001 17-year-old daughter moves in w/boyfriend

2001 Memorial Service Harlan #7 explosion—38

It takes some time to work all this out, but once it’s done, you’re free. You don’t have to constantly calculate how old someone was when a given event happened in their lives, whether two characters could have met in college or if phonographs had been invented when a character was a teenager. Say I glibly write about two of my characters that “…they were high school sweethearts before he was shot down over Germany…” I can look at the timelines and realize that’s not going to work because she graduated from high school in 1958 and he was 8 years old when the Allies bombed Germany.

And timelines aren’t engraved in granite. If something doesn’t work, just change it. But timelines help you remember that if you change a character’s age or when they got married, you have to change everything else associated with those dates—graduation, marriage, their children’s ages, etc.

Hang in there, the pre-writing activities are ALMOST over. Pretty soon, you’ll be able to sit down and begin your “once upon a time…”