Ninie Hammon's Blog, page 4

June 13, 2013

Three Ways to Grab Your Reader’s Heart

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

#4 GENUINE EMOTION

Granny Sparrow’s quiet voice got so soft it was almost a whisper. “I took to the closet. There in the beginnin’, I had to. The house was so quiet I could hear my own heartbeat. I’d turn on the television loud as it’d go in the living room and the radio in the bedroom. Then I’d plug in the vacuum cleaner …” She looked a little sheepish. “ … and I’d take it with me into the bedroom closet in Ricky Dan’s room, sit down on top of the shoes, the shirts and coats a-hangin’ down all around me. I’d hit the switch on the vacuum and that little bitty space’d fill up with noise…” There was a beat of silence. “ … and then I’d scream. Loud’s I could, scream and wail ’til my voice give plum out. I’d beat my fists against the wall ’til my hands was black and blue.” Then she was whispering. “I wanted to make more noise than the roar under the mountain, ’cause my hurt was bigger and powerfuler than the ’xplosion that took them from me.”

Black Sunshine

Grief. Rage. Joy. Love. Hate. Fear.

Genuine Emotion. It’s Number Four in the Ten Essentials of a Dynamite novel.

The characters in your novel have to feel.

More important, Loyal Reader has to feel. Engage his mind and he’ll be impressed with your command of the language, perhaps, intrigued by the twists and turns in your plot, interested in the resolution of the conflict. But engage his emotions and he’ll care what happens, he’ll suspend disbelief, step into the story with your characters and take the journey with them. And when he comes reluctantly to the two words centered on the last page, Loyal Reader will not be the same person he was at “once upon a time.” That’s powerful writing, my friend. That’s what you should be willing to swim through ten miles of bat guano to achieve.

And how, exactly, do you do that? The good news is that there are three essential steps. The even better news is that none of them involve excrement or winged nocturnal bloodsuckers.

The first essential step: you must create a plot that justifies an authentic emotional response. There’s little in writing that’s as futile as trying to conjure up emotion in your character when what is happening to him doesn’t warrant it. Make your plot so terrifying that any being with opposable thumbs would be scared spitless. Make it sad enough to elicit real grief. Make it so hopeless that despair is the only reasonable response. Fail in that and your characters will spew hyped-up, disproportionate emotions all over the landscape of your novel. And Loyal Reader will bail on your story in favor of a riveting tale from Farmer’s Almanac or Corporate Tax Law.

Second, you must create characters capable of an emotional response. Cardboard characters have no more emotional capacity than what they are– paper dolls. Stereotypes produce only stereotypical responses. The prom queen whose football-captain boyfriend invites another girl to the prom will suffer that sorrow with the same superficial tears that made her a one-dimensional character in the first place. A simple principle applies—what’s in the well comes up in the bucket.

Third, and perhaps most important, in order to produce genuine emotion in your novel you have to be willing to mine your personal life and soul for your own emotional responses. No, I am not suggesting that if you haven’t felt a given emotion you can’t write about it. But I am suggesting that unless you’ve felt something like the emotion your character feels, you’re shooting at a target you can’t see. Plumb your soul. What have you felt deeply in your life? USE it. Use your pain and your joy and your anger. The more varied the experiences you have faced in life, the richer your capacity to express emotion should be.

I’m not saying that young writers are unable to put emotional punch in their writing. But I am saying that those of us who have years of living under our belts, who’ve traveled many miles through life—mostly on roads that weren’t paved—should bring a depth of experience to our writing that has the clear ring of truth.

Have you ever been scared? No, I mean really scared. The day a tarantula spider crawled across my face, I was so terrified I was literally unable to move. And when I screamed, I could feel its hairy legs in my mouth. So when I write about a character who is frightened, I understand the emotion on a visceral level. My task then becomes crafting the images necessary to translate that emotion onto the page–where it will leap out and grab Loyal Reader by the throat.

Have you known grief. Horror? Rage? The day I watched flames eat up my world and sprinkle its remains in floating sparks across the night sky, I became intimately acquainted with all three of those emotions. You’ll find the grief in Granny Sparrow in Black Sunshine, the horror in Sarabeth Bingham in Home Grown and the rage in Ron Wolfson in Sudan.

My point is simply this: if you want to create authentic, believable emotion in your character, you need to find something like that emotion in your own soul. Then your task is to describe it as accurately and artfully as you can.

Think of emotion as the nuclear material of your novel. Craft it well and your novel will set off an emotional explosion in Loyal Reader’s heart he’ll remember always. Craft it poorly, however, and the puny pop of your firecracker will illicit nothing but a yawn and a bored, three-word response: get over it.

May 26, 2013

What EVERY writer MUST tell EVERY Fan

This blog post is for readers, not writers. But it’s one EVERY writer will love. It’s the post every writer wants to write and certainly needs to write … but usually doesn’t. I suspect my writer friends will post links to it on their blogs—so their readers get to hear it, but they don’t have to say it.

This blog post is for readers, not writers. But it’s one EVERY writer will love. It’s the post every writer wants to write and certainly needs to write … but usually doesn’t. I suspect my writer friends will post links to it on their blogs—so their readers get to hear it, but they don’t have to say it.

Why all the angst? One word: awkward. It’s awkward to explain to your Loyal Fans that your ability to continue in the art and craft of writing is more completely in their hands than they realize. Unless they are willing to partner with you, the books with stories that keep them up nights and with characters they remember forever won’t be written. Without the intentional support of Loyal Fans, Favorite Author could end up writing television commercials or obituaries for a living.

Along in here somewhere, the wonderful Loyal Fans reading these words are beginning to protest. But we do support the writers we love. We buy their books! We read their books! We love their books!

And writer or not, I find it hard to adequately express how much that means to me and to every writer I know. When you buy our books and tell us you liked them, it is glorious on steroids. And if you never did another thing but buy, read and like our books, we would remain forever grateful to you for it.

But it’s a hard truth that in today’s publishing world, Favorite Author needs more than that from his fans to survive.

What you as a reader might not know is that unless a writer’s name happens to be Stephen King or Danielle Steele or Karen Kingsbury, he or she is literally drowning in a sea of other writers’ books. In past decades, big publishing houses like Penguin-Putnam, Random House, Simon & Schuster and smaller houses like my publisher, Bay Forest Books decided how many books were published and the number was self-limiting. A book had to be good enough to make it down the gauntlet of agents, editors and marketing experts.

That day is gone.

With the advent of e-publishing, anyone on planet earth who can string a subject and predicate together can publish a book. Anyone! There’s great debate over the quality of e-published books (I’ve found indie authors who are fabulous!) but it doesn’t really matter whether the books are good or bad because it’s the sheer number of them that’s the issue—for indie authors and the traditionally published as well. And it’s staggering!

In 2006, the year my first book was published by Penguin Putnam, there were about 380,000 books published in the U.S. In 2012, there were 15,000,000.

FIFTEEN MILLION! In that massive, overwhelming sea of choices, potential readers get hopelessly lost and writers slowly sink below the horizon and are never heard from again. There was a time when the greatest challenge a writer faced was writing a book good enough to be published. Now, our greatest challenge is merely getting noticed!

The only hope we have in that effort is our fans. If—and ONLY if—a writer’s work is good enough to have developed a loyal following, the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t a train. You see, one thing in publishing HASN’T changed. The Number One reason a reader buys a book is the same now as it was 25 years ago. Readers buy books—whether traditionally published or an e-book—because someone they know recommended it. Word-of-mouth advertising—the keys to the kingdom. The math is simple. A reader tells two others about a wonderful book he just read. Those two readers tell two more… and two more … and eventually the royalty check is enough to survive on while you write the next book.

This is where it gets really awkward. Loyal Fan is now saying, “but I do recommend Favorite Author’s books to my friends.” And I have to explain tactfully that this conversation over coffee—“Hand me the sugar, would you, Thelma. Hey, I read Favorite Author’s new book the other day, really liked it. Billy, you stop that! Do you hear me? You hit your sister one more time and I’m going to screw your head off your shoulders like the lid off a pickle jar!”—will NOT get the job done.

Every writer needs readers who make the book of yours they just read the reason for a conversation with a friend—with lots of friends. Who annoy the librarian until she puts the book on the shelf. Who write a review on Amazon of every book of yours they read. Who tell their Sunday School class about it and the guys on their bowling team, their hair dresser and barber and personal trainer. Becoming a reader who’s willing to partner with your very own Favorite Author to make a book and the author successful doesn’t cost much in terms of time or effort for the reader but for an author it can make the difference between writing that next book and going into real estate.

I know writers who have teams of Loyal Fans who do just that—and much more. And those teams get the inside story on upcoming books, get to name characters and read sample chapters, win autographed copies and a Skype with the author. I’m planning to launch a team of my own soon. (Maybe call it 9e’s Nutcases?) But every reader who loves a book needs to understand that in the World of Publishing in 2013, their support—in big and little ways—is the only thing that allows a writer to produce the entertainment they enjoy. Those of us who don’t get that kind of support will sink in the jam-packed waters of publishing-dom. And our readers will be the only ones who notice that their Favorite Author is gone.

May 19, 2013

Heroes & Villains: You Need Both

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

#4 GOOD GUYS & BAD GUYS

Where would Luke Skywalker be without Darth Vader?

Harry Potter without Valdemort.

The Three Little Pigs without the Big, Bad Wolf?

Black hats, white hats; good guys, bad guys; heroes and villains. Protagonists and antagonists. Each plays a particular role in a story. Get that part right and Loyal Reader cheers for the good guy and hisses at the bad guy and stays up all night to see who wins. Get it wrong and Loyal Reader takes your great American novel along on camp-outs to use when he runs out of toilet paper.

Let’s start with the role of the protagonist, who is the character Loyal Reader identifies with, whose fate matters, the character who either has a goal we hope-hope-hope his relentless struggle will attain for him, or a catastrophe we hope-hope-hope his relentless struggle will succeed in averting. It is the protagonist who drives the plot forward, whether he is Frodo in Lord of the Rings who must succeed in his quest or the world will be covered in darkness or Woody in Toy Story III who must save his friends from a murderous teddy bear. Of course, protagonists like Batman and James Bond drive the plot as well, even though they are not engaged in striving toward a goal themselves but are caught in a deadly struggle to keep all manner of evil dudes from fulfilling theirs.

Let’s start with the role of the protagonist, who is the character Loyal Reader identifies with, whose fate matters, the character who either has a goal we hope-hope-hope his relentless struggle will attain for him, or a catastrophe we hope-hope-hope his relentless struggle will succeed in averting. It is the protagonist who drives the plot forward, whether he is Frodo in Lord of the Rings who must succeed in his quest or the world will be covered in darkness or Woody in Toy Story III who must save his friends from a murderous teddy bear. Of course, protagonists like Batman and James Bond drive the plot as well, even though they are not engaged in striving toward a goal themselves but are caught in a deadly struggle to keep all manner of evil dudes from fulfilling theirs.

Which brings us, of course, to the evil dudes, the antagonists whose job it is to thwart the protagonists. If the hero wants something, the villain is set in place to see that he doesn’t get it. If it is the antagonist who wants something, it’s his job to run smack through the middle of the protagonist in his headlong dash toward whatever it is he’s determined to have or do.

Which brings us, of course, to the evil dudes, the antagonists whose job it is to thwart the protagonists. If the hero wants something, the villain is set in place to see that he doesn’t get it. If it is the antagonist who wants something, it’s his job to run smack through the middle of the protagonist in his headlong dash toward whatever it is he’s determined to have or do.

There are several ways I’ve seen fledgling novelists stray from the middle of the road into the potholes in creating their white hat/black hat characters. One of those is the propensity of beginners to create a protagonist who is too perfect, a broad-shouldered, square-jawed, (dimples, a chin cleft and a widow’s peak, too) 6-foot 6-inch hunk with washboard abs who just exchanged his Super Bowl ring for a badge and now solves bloody, serial murders by day, writes gentle love songs to his chaste sweetheart by night and works in the soup kitchen at a homeless shelter on weekends.

Maybe all that perfection is why some beginners can get bogged down in the second most common mud hole in the road—they just flat out like their characters too much. Consequently, they’re unwilling to put their hero in real danger, allow him to suffer loss or be in pain—whether physical or emotional. Loyal Reader can smell that on page three, by the way, and ten pages in he’s stuffing your book in the duffle with his tent and sleeping bag. Where’s the fun for readers if they can’t possibly identify with the hero and know they can sail through the story without any real angst because Rock-Abs is going to come out of every fray without a scratch. Stereotyped, unscathed heroes make good Saturday morning cartoons and lousy novels.

But in truth, I have seen way more writers turn their villains into stereotypes than their heroes. Even writers who have the Normal-Hero gene often lack the Three-Dimensional Villain gene.

It is such an easy pothole to stumble into. After all, what better way to make the hero, well, heroic than by making the villain the absolute meanest dog in the junkyard, the kind of guy who’d spread oil on the floor in a nursing home or tear the bottom out of airplane air-sick sacks. And genuinely, seriously, much, much worse. So we pile on the vile attributes in an effort to make our hero’s triumph over the evil dude even more dramatic. Unfortunately, that doesn’t improve the victory, only cheapens it. Antagonists with real human attributes, who have mothers and goldfish and girlfriends and were once gap-toothed first graders and awkward teenagers make far better villains. When Loyal Reader can identify in some small way with the villain as well as the hero, he is much more engaged in the story and has a greater stake in its outcome.

The absolute bottom line about protagonists and antagonists is the four-letter word we will use to measure all our efforts when we come to the discussion of characters. That word is REAL. And how, exactly, do you make both hero and villain real? We’ll talk about that.

Until then …

Write on!

9e

May 12, 2013

Conflict: there are only four kinds

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

#3 CONFLICT

For the record, I don’t entirely agree with what I’m going to tell you about conflict. You could say, I suppose, that I’m in conflict with conflict.

It is the common wisdom in literary circles that there are only four types of conflict, that in all the annals of story-telling, from cave paintings to Finding Nemo, every conflict has fallen into one of four categories.

I have issues with the classifications for several reasons, one of them being that there’s often more than one type of conflict going on in any given story. But we won’t chase that rabbit today. As I’ve said here before, you have to know what the rules are before you can earn the right to disregard them. So let’s talk about the basic classifications, which are somewhat self explanatory, and some examples of each.

MAN AGAINST MAN

Into this category fall all those stories where good guy meets bad guy, they duke it out and the hero stands triumphant.

Think Luke Skywalker versus Darth Vader. Frodo versus Gollum. (And it is Frodo versus Gollum, not Frodo versus Sauron. We never SEE Sauron. Well, his eye now and then. But in the end, it is Gollum who fights to the death to prevent Frodo from accomplishing his quest.) In Silence of the Lambs, Special Agent Starling fights Dr. Hannibal Lextor—even though they never touch each other, but when Sara Connors goes up against The Terminator, there is tremendous physical violence. Les Miserables is a classic Man Against Man conflict, pitting Jean Valjean against the police detective Javert. The Fugitive is one, too, for the same reasons.

MAN AGAINST NATURE

In essence, this category encompasses all those stories where man must battle the elements, or some creature spawned by the elements. Three fishy examples of this category are Jaws, Moby Dick and The Old Man and the Sea. In each, man must do battle against a denizen of the deep in a life-and-death struggle. Same is true to some extent of The Life of Pi, in which the boy must battle both the sea and the tiger, and in Robinson Crusoe, where the island itself becomes the adversary. In The Perfect Storm, a ship’s crew battles a massive hurricane.

This is one of the places where I veer to the south of traditional thinking. I’m not so sure nature can be the antagonist in a story because nature has no free will. Nature itself is not bent on a particular man’s destruction. And if you dig into many Man Against Nature stories, you find that nature is the really the catalyst that brings out the true conflict—which is actually Man Against Himself. Yes, Captain Ahab was fighting the white whale. But waaay more important is the battle of pride he fought within himself—and lost. How about The Perfect Storm? Was the crew of the Andrea Gail battling a hurricane or their own pride and greed?

MAN AGAINST SOCIETY

These stories pit the protagonist in a struggle against the ideas, practices or customs of other people. In the children’s classic, Charlotte’s Web, it is Wilbur versus a society that eats pigs. In The Bee Movie, a lone bee takes on mankind’s practice of “stealing” honey. Think 1984. And The Hunger Games, which is both a Man Against Man and a Man Against Society conflict.

MAN AGAINST SELF

This is the conflict in all stories in which man struggles with his own soul, his ideas of right and wrong, his choices. It’s the conflict in A Beautiful Mind, where Dr. John Nash must confront and conquer his mental illness, and in Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde where the two halves of one man actually manifest themselves physically. In Julius Caesar, the protagonist, Brutus, goes to war with himself over his loyalty to his friend and his loyalty to his country. Only one side wins—the Brutus who believes murder is justified in the name of preserving democracy.

As I mentioned above, Man Against Self is often the root conflict in stories that seem to be about other things. For my money, any story is improved when there are layers of conflict—when the protagonist in a Man Against Man story must first conquer his own demons, win in the battle with himself before he takes on the world at large.

Write on! 9e

May 3, 2013

Three Roles of Setting in a Novel

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY

#2 SETTING

Why is setting so important in a novel?

Because it defines your characters.

Or exemplifies your characters.

Sometimes, actually becomes a character.

Setting both affects characters and is the effect of characters. (Yup, I know the difference between affect and effect. But lie/lay/lain … not so much. That’s why nobody ever goes to bed in my novels. Now’s not the place for a grammar lesson, though, so we’ll just blow by that and steer right into an example.)

I once ran a newspaper in a county that had five elementary schools and for a particular story, I visited the principals of all of them on one day.

In the first school, the principal’s office featured walls in bold, primary colors bedecked with “sweet art”—cherubic children offering apples to equally cherubic teachers, cuddly puppies, adorable kittens and mottos in cross-stitch. If you can read this, thank a teacher. Teachers water little acorns that grow into big oak trees. To find a seat, it was necessary to negotiate a path through a forest of hangle-dangle mobiles draped from the ceiling—butterflies, hummingbirds, bees—and toy fighter planes. (That was a disconnect.) Legions of Precious Moments figurines battled for prime real estate on the desktop.

Contrast that with the second principal’s office. Neat. Tidy. Orderly. Shelves with books arranged in alphabetical order by author’s last name.

Desk bare except for a Shafer pen-and-pencil set still in the box, a telephone, and In/Out trays—both empty. Behind her desk was a single black-and-white Ansel Adams’ picture. Otherwise, the walls were unadorned, painted the gray of tarnished silver.

Another principal actually had a deer’s head on one wall—a doe that bore, in my opinion, an uncanny resemblance to Bambi’s mother. One’s office was awash in a sea of kid art—Thanksgiving turkeys made out of kids’ handprints, orange construction-paper jack-o-lanterns, and Santa Claus faces made from the lids of peanut butter jars, cotton balls and red felt. The final office struck me as more befitting an absent-minded professor than an elementary school principal. A desk piled high with papers, books strewn all over the chairs and floor. I stood for the interview because the only available seat was a taken by a cookie sheet on which either the Alamo or the Taj Mahal had been constructed out of sugar cubes.

Obvious principle (not principal) here: people create the environments they live in. Our offices and homes and work spaces make statements about who we are.

The setting of your novel should tell the reader something about the character of your character.

Or perhaps the setting shapes the character of your character.

Consider this description from Black Sunshine.

As the empty coal truck bumped farther into the paint-splattered mountains, each twist and turn opened up a view more hauntingly familiar than the last.

They passed Pine Mountain Taxidermy Shop—“You rack it, we’ll pack it.” The farm-house/office of Lester Tungate’s Used Cars flew past the truck window. Five vehicles, half a dozen bird baths and a flock of concrete ducks sat in the front yard there awaiting adoption. A hand-painted sign nailed to a nearby fence post offered HAND-PAINTED SIGNS for sale. The Convenience Store just down the road promoted Kentucky lottery tickets—“Somebody’s got to win; might as well be you!”—as well as the Kentucky Fried Chicken Restaurant in Hazard—“Eat supper with the Colonel tonight.”

The sign out front of the Four Square Full Gospel Pentecostal—pronounced Penny-costal—Church proclaimed: “You not believing in hell don’t put the fire out!”

Trailer houses, alone or in small herds, were affixed to the mountainsides with round, white stick-pins. Will had heard they’d declared the satellite dish the official flower of West Virginia and it was plain the seeds had blown across the state line.

The sides of the valley rose so sharply on either side in some places there was room only for the creek, the road, the railroad tracks and the shaft of sunlight that shown down between the ridges.

Five hours of sun.

Will had grown to manhood in more shadow than light, in a hollow so deep the mountains only granted it direct sunlight five hours a day.

The setting so shaped the characters in this novel that the story could not have taken place anywhere else on the planet.

And finally, sometimes the setting actually becomes a character in your novel. No detailed example is necessary here. Consider the sea in The Old Man and The Sea or The Life of Pi, the island in Swiss Family Robinson, or the fog in Stephen King’s 1980 novella The Mist.

Does setting play an important role in your novels? How? Or can you think of novels where setting is an especially telling element? I’d love to hear about them in the comments below.

Next week, we’ll talk about hats, white ones, black ones and shades of gray.

April 26, 2013

10 Essentials of a Dynamite Story #1

You have to reach up out of the pages of your book, grab your Loyal Reader by the lapels and yank him out of his world into a place he’s never been, where he’ll be introduced to engaging people—both good and bad—who are in big trouble of some sort. And those people will haul Loyal Reader along with them as they face obstacles, grow, change, make stupid decisions, hurt the people they care about, are courageous, noble, selfish and intolerant, who behave really badly and surprisingly well and all the gradations in between. When those people finally get to the two little words The End on the last page, they absolutely will NOT be the same people they were when you intoned “Once upon a time” in Chapter one. But guess what, neither will Loyal Reader. If Loyal Reader isn’t transformed in ways both small and profound by the journey of your story, the conflicts overcome and the companionship of your characters, you need to back up to once upon a time and start over.

Sound easy. Of course not! But if it sounds hard, console yourself with the clear and certain knowledge that it is even harder to do than it sounds. It is, indeed, the hardest work you’ll ever do. It’s the most gratifying work you’ll ever do, too. Hey, this is why you became a novelist!

Let’s back up to two weeks ago when I said there are three legs on a Novel-Writing-Stool.

As novelists, we must:

1. Draw pictures in our readers’ heads.

2. Tell a run-away train story.

3. Introduce our readers to characters so real they become cherished family members.

Remove any of the legs of that stool and you wind up on your backside on the floor. If you don’t draw pictures, the reader will never see the story. If you don’t have a story to tell, maybe you should consider going into real estate. And if you don’t have characters to love/hate, the reader won’t care about the first two.

Which brings us to the run-away train story. We’re going to have to unpack this piece by piece for a few weeks because it is arguably the most complex part of the process.

You can come up with lists unnumbered about what constitutes a good story. (That’s why God created Google.) Over time, I’ve compiled my own checklist, which is probably a lot like and very different from the others.

We’ll talk about each one of these in more depth as we go along, but here are Ninie Hammon’s Essential Elements Of A Great Story. We could make that into an acronym, but unfortunately it doesn’t spell anything. NHEEOAGS? And I hate it when people twist and torture the names of things just to make the acronym work. But that’s a blog for another time. Here are the 10 Essentials:

1. Setting. So perfect the story absolutely couldn’t have happened anywhere else on the planet.

2. Protagonist/Antagonist. The good guy and the bad guy: white hat, black hat.

3. Conflict. There are only four to pick from: man against man, man against nature, man against God or man against himself. Those four are all you need; every story ever told has used one of them.

4. Genuine emotion. If your characters don’t feel anything, neither will Loyal Reader.

5. Unexpected twists and turns. Predictability is booooring.

6. Great dialogue, both internal and external. What your characters say must sound like people actually talk! And we need to know what they’re thinking, too.

7. Recognizable theme. What is your story about? Courage? Greed? Does it make a point about the nature of reality? Theme arises organically from the story, but some writers START with theme and wrap a story around it. I’m one of those writers.

8. Inciting incident. Your characters are sailing along on smooth water and your job is to get them into the rapids fast. The creek between the two is the inciting incident.

9. Resolution. After the climax, then what?

10. Authentic voice. We have to hear your voice so clearly it becomes the canvas on which everything else is painted.

Next week, we’ll start unpacking this list. Come and join me. And do leave a comment to let me know what you think or to ask questions. I’d love to interact with you.

10 Essentials of a Dynamite Story

You have to reach up out of the pages of your book, grab your Loyal Reader by the lapels and yank him out of his world into a place he’s never been, where he’ll be introduced to engaging people—both good and bad—who are in big trouble of some sort. And those people will haul Loyal Reader along with them as they face obstacles, grow, change, make stupid decisions, hurt the people they care about, are courageous, noble, selfish and intolerant, who behave really badly and surprisingly well and all the gradations in between. When those people finally get to the two little words The End on the last page, they absolutely will NOT be the same people they were when you intoned “Once upon a time” in Chapter one. But guess what, neither will Loyal Reader. If Loyal Reader isn’t transformed in ways both small and profound by the journey of your story, the conflicts overcome and the companionship of your characters, you need to back up to once upon a time and start over.

Sound easy. Of course not! But if it sounds hard, console yourself with the clear and certain knowledge that it is even harder to do than it sounds. It is, indeed, the hardest work you’ll ever do. It’s the most gratifying work you’ll ever do, too. Hey, this is why you became a novelist!

Let’s back up to two weeks ago when I said there are three legs on a Novel-Writing-Stool.

As novelists, we must:

1. Draw pictures in our readers’ heads.

2. Tell a run-away train story.

3. Introduce our readers to characters so real they become cherished family members.

Remove any of the legs of that stool and you wind up on your backside on the floor. If you don’t draw pictures, the reader will never see the story. If you don’t have a story to tell, maybe you should consider going into real estate. And if you don’t have characters to love/hate, the reader won’t care about the first two.

Which brings us to the run-away train story. We’re going to have to unpack this piece by piece for a few weeks because it is arguably the most complex part of the process.

You can come up with lists unnumbered about what constitutes a good story. (That’s why God created Google.) Over time, I’ve compiled my own checklist, which is probably a lot like and very different from the others.

We’ll talk about each one of these in more depth as we go along, but here are Ninie Hammon’s Essential Elements Of A Good Story. We could make that into an acronym, but unfortunately it doesn’t spell anything. NHEEOAGS? And I hate it when people twist and torture the names of things just to make the acronym work. But that’s a blog for another time. Here are the 10 Essentials:

1. Setting. So perfect the story absolutely couldn’t have happened anywhere else on the planet.

2. Protagonist/Antagonist. The good guy and the bad guy: white hat, black hat.

3. Conflict. There are only four to pick from: man against man, man against nature, man against God or man against himself. Those four are all you need; every story ever told has used one of them.

4. Genuine emotion. If your characters don’t feel anything, neither will Loyal Reader.

5. Unexpected twists and turns. Predictability is booooring.

6. Great dialogue, both internal and external. What your characters say must sound like people actually talk! And we need to know what they’re thinking, too.

7. Recognizable theme. What is your story about? Courage? Greed? Does it make a point about the nature of reality? Theme arises organically from the story, but some writers START with theme and wrap a story around it. I’m one of those writers.

8. Inciting incident. Your characters are sailing along on smooth water and your job is to get them into the rapids fast. The creek between the two is the inciting incident.

9. Resolution. After the climax, then what?

10. Authentic voice. We have to hear your voice so clearly it becomes the canvas on which everything else is painted.

Next week, we’ll start unpacking this list. Come and join me. And do leave a comment to let me know what you think or to ask questions. I’d love to interact with you.

April 19, 2013

Three Ways To Draw Pictures In Your Readers’ Heads

I suspect it’d be easier to sneak a pipe bomb through security at the Tel Aviv airport than to get any three authors to agree on a job description. Exactly what is it we get paid those megabucks to do? Toss that question out at a writing conference and watch the fireworks.

I suspect it’d be easier to sneak a pipe bomb through security at the Tel Aviv airport than to get any three authors to agree on a job description. Exactly what is it we get paid those megabucks to do? Toss that question out at a writing conference and watch the fireworks.

I say that to point out that what follows is The World According To Ninie. A quarter of a century in journalism, a biography and seven published novels into the writing profession, I’ve settled on what I think are the three most important elements. Like a three-legged stool. Those of you who’ve never had the privilege of milking a cow will miss the significance of that. A four-legged stool will stand up even if it’s missing one leg. A three-legged stool won’t. The other two legs aren’t positioned to carry the weight.

These are the three legs on my Novel-Writing Stool. We must:

1. Draw pictures in our readers’ heads

2. Tell a run-away-train story

3. Create characters so real they become cherished family members

This week, we’ll talk about the first one.

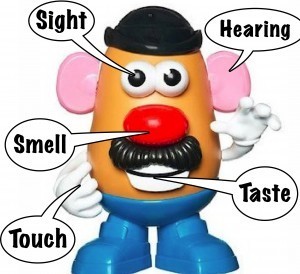

How do you draw a picture in a reader’s head? It starts with seeing the scene clearly yourself. If you have only a vague sense of it, that’s what you’ll convey to the reader—vague. Groceries. As we talked about last week, you can’t describe “groceries;” you CAN describe Fritos and bean dip. It’s called specificity. Know what the scene looks like—specifically—then transcribe it.

OK, you say, I see it. Now what?

You see it. Great.

Do you smell it?

Do you hear it?

What does it taste like? Feel like?

Drawing pictures in readers heads involves employing the senses. Not all of them at once, though. The rule of thumb is not to employ more than three in any given passage. If you show the reader what it looked, sounded and smelled like, they probably don’t need to know what it tasted or felt like, too. Too much attention to sensory detail and the reader will skip over descriptive passages and move on to the action.

You see it, you note sensory details, and finally, you use strong, active, concrete words. Let me insert a word of caution here. You’d be wise not to let description—drawing pictures in readers’ heads—bog you down in the first draft. What’s important in a first draft is to get black on white. The first draft is not the place to spend three hours figuring out how best to describe the ramshackle old house that is the setting for your whole book.

It’s easy to talk about these things—envisioning, appealing to the senses, using strong, concrete words. It’s another thing altogether to do it. Here are some examples of what I’m talking about, excerpts from some of my books, to help you see how you use different sensory details to draw pictures in your readers’ heads. Next week, we’ll talk about stories.

HEARING

A sudden clap of thunder ripped open the crisp autumn afternoon, banged harsh and loud—but not in the cloudless sky. The crack and boom roared in the tangled roots of Black Mountain, deep in the dark guts of the earth.

In the stunned stillness that followed, time shut down for an airless, eternal moment. Not a bird cheeped; not a dry leaf rattled.

Then the earth groaned, as a man might cry out in his sleep. Rumbled. And the rumble swelled, became a grating death rattle like gravel in a blender. The ground shook, dogs howled, kitchen cabinets flew open, glasses, plates and bowls clattered out and shattered in a tinkling symphony of breaking glass. Pictures and mirrors leapt off walls, clocks crashed to the floor and stopped—all of them at the same time: 12:18 p.m. Black Sunshine

SMELL

Half a dozen different tribal dialects babbled around him, mingled with the animal sounds from a menagerie of creatures—cows, pigs, goats, chickens, guinea hens—in a background noise he heard but didn’t really listen to.

But it was a lot harder to tune out the stink than the noise. The reek from the fish laid out on the dock when he stepped off the barge that morning had been heightened and magnified by the mid-day sun to create a stench that was foul beyond description. There was no wind, and the odor hung like a fetid fog in the air.

Ron began to make a mental list of all of his favorite smells: coffee brewing, honeysuckle after a spring rain, steaks on a backyard grill, the upholstery in a new car, a pretty girl’s hair . . . Sudan

SIGHT

The steep, tree-lined Appalachians rose around him like giant ramparts protecting a castle, their autumn splendor set against a blue sky dotted with cotton-ball clouds tethered like hot-air balloons to the treetops. The medley of color splashed on the hillsides—Claret-wine red, the gold of a Spanish doubloon, smiley-face yellow, the deep russet color of a chestnut foal’s coat or an auburn-haired toddler, pine green and an amber shade of brown—reminded Will of Scottish clan tartans. No, it was the other way around. The clan tartans he’d seen in tourist shops on the Isle of Skye had reminded him of autumn in the mountains. Black Sunshine

TASTE

Ron lifted the glass Masapha had set in front of him to his lips and took a big gulp. A sip would probably have been smarter; he wouldn’t have had quite so much liquid to spew back out of his mouth onto the floor and his shoes.

“What is this stuff?” he gasped.

“It is aragi, the local beer.”

Ron noticed that Masapha drank only water. “You knew this stuff tasted like paint stripper, didn’t you? That’s why you didn’t order any.”

“Yes, I have heard it has the flavor of goat urine.”

“I don’t know about goat pee, but it definitely tastes worse than moonshine!” Ron sputtered, and spit on the floor to get the last remnants of the foul liquid out of his mouth. Then he saw the blank look on Masapha’s face. “You don’t get moonshine, huh. Never mind. I just hope I don’t go blind.” Sudan

TOUCH

She sits down in the backseat by the open window and cradles the little girl in her arms. She turns and stretches her legs out on the leather-covered bench and wiggles a little to get comfortable. Then she relaxes.

And with every breath, she concentrates on feeling Angel in her arms. The weight of her. Her warm, soft skin. The smell of her silky hair.

She pats her back softly and sings into her ear quiet, nonsense words borne on strange, haunting melodies. She kisses her forehead or her cheek or her nose between verses.

Angel stirs now and then, wiggles. Once she opens her hand and grasps Princess’s finger and holds on, like she used to do when she was a newborn. Then she sighs and settles, the sweet scent of her warm breath a bouquet in Princess’s face. Five Days in May

April 12, 2013

Three Things Every Novelist MUST Do

I spent a lot of years telling rooms full of just-out-of-J-School reporters to “picture groceries.” For a decade, I gave up a few days every summer to teach at state press association “boot camps” where the goal was to whip the newbies into pros over the course of a single week. Impossible task, of course, but I do love a challenge.

I spent a lot of years telling rooms full of just-out-of-J-School reporters to “picture groceries.” For a decade, I gave up a few days every summer to teach at state press association “boot camps” where the goal was to whip the newbies into pros over the course of a single week. Impossible task, of course, but I do love a challenge.

I started every class the same way. I’d say just two words: picture groceries. And then I’d just stand there.

The room would get quiet. Silence is a great tool that few speakers use well. It’s best if you let it drag out until it’s teetering on the edge of uncomfortable before you say anything else. When you do, you’ll have the rapt attention of every person in the room.

“What comes into your mind when you think: ‘groceries?’”

Sometimes I’d pick on some poor schlep who demonstrated extremely poor judgment by sitting on the front row. I’d single her out—way too skinny, owlish glasses, look of studied concentration on her face.

“So Miss…”

“Susie Snodmotz,” she’d tell me helpfully.

“Yes, Miss Snodmotz, what picture forms in your head when I say the word: ‘groceries?’”

If she was smart, she’d just shrug and keep her mouth shut. But they’re never smart.

“Well…uh… I see…you know…I see ‘groceries.’”

“Really? And tell me, what do ‘groceries’ look like?”

“They look like … you know… like…”

By that time, she’d stewed in her own juices long enough and I’d made my point.

“Ok,” I’d say, “so tell me what you see in your head when I say, ‘a slice of watermelon pock-marked with seeds, pink Georgia peaches, ripe bananas, a shiny green pepper, bulbous grapes and fat cucumbers?”

For some in the class, the light comes on. Most still don’t even know where to look for the switch.

“You can see that, can’t you? The watermelon slice hanging out the top of the brown paper sack, or the pepper and cucumbers falling through a hole in the bottom of those Saran Wrap plastic bags. You can see it. But what else can you see?”

More silence.

Sigh.

“You can ‘see’ something about the person who bought the groceries, right,” I’d prod. “The items tell you something about him without any explanatory statement at all. Who buys watermelon, peppers, carrots and bananas? A wino? No. A hungry college student? Probably not. How about a health nut in jogging shorts and New Balance running shoes? You see where I’m going with this little illustration?”

Silence again.

“That, boys and girls, is what we get paid to do! We get paid to draw pictures in our readers’ heads by describing reality so specifically they can see what we see.”

As it turns out, the real dunce in the class was me, not the students. But it was years before I put it together in my head that the main reason the newspaper newbies didn’t get what I was talking about was that I was not one of them. I spent a quarter of a century as a novelist-in-journalist-clothing. My newspaper career was studded with writing awards because I intuitively knew how to do what every good novelist does every day—draw a picture in a reader’s head.

And that boys and girls, IS our job as novelists. We have to make our readers see what we see—even though we don’t really “see” anything at all. Well, actually, that’s only a third of our job. Another third is to tell a run-away train story that sweeps our readers off the steps of the station and carries them away. And the final third is to introduce them to characters so real they become cherished family members, so well loved they leave a vacant place in our reader’s heart when the novel’s over.

So exactly how is it that we manage to accomplish those three tasks? Ahh, I thought you’d never ask. We’re going to talk about that very subject in the weeks to come.

April 5, 2013

Don’t Break Your Promise To Your Readers

I spoke to a group of fledgling suspense novelists last week and loved their fire and enthusiasm. I tried hard not to dampen that fire when I answered the questions they’d submitted. A dose of reality can be a bit of a downer, but a clear view of the way the writing world functions is as necessary for a budding writer as knowing the difference between their, they’re and there.

I spoke to a group of fledgling suspense novelists last week and loved their fire and enthusiasm. I tried hard not to dampen that fire when I answered the questions they’d submitted. A dose of reality can be a bit of a downer, but a clear view of the way the writing world functions is as necessary for a budding writer as knowing the difference between their, they’re and there.

I’ll share some of their questions with you, give you an insight into genres, brands and the promise every writer makes to his reader when he writes his second book.

I HEAR THE TERMS MYSTERY AND THRILLER AND SUSPENSE—WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Though many novels combine a couple of these genres—because they’re closely related—the distinctions are fairly simple. In all three, there is danger and the main character is trying to find out something, some truth, or to prevent some bad thing from happening.

In a mystery novel, the main character must solve some sort of puzzle—usually about an unfortunate death or string of deaths. That character is not necessarily in any danger—though he might be as he nears the truth about who is responsible for the carnage. But other characters are often in great danger. Many times the detectives who solve the puzzle are themselves quite harmless, little old ladies like Miss Marple or child sleuths like Nancy Drew.

In a suspense novel, the danger grows as the book progresses. The screws tighten page by page. The main character in a mystery has the same information as the reader, but in a suspense novel, the reader often knows things the main character does not. The reader watched the terrorist plant the bomb or knows the murderer is waiting with an ax behind the door. The tension builds as the reader stands by helpless while the hero edges closer and closer to disaster.

A thriller is the easiest of the three to define. In a thriller, the main character starts the book in danger and stays in danger to the end.

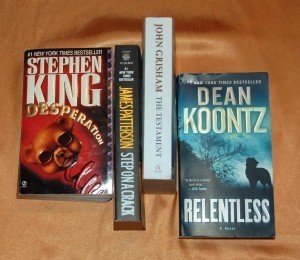

The grand masters of the mystery/thriller/suspense genres are Agatha Christi, James Patterson, Stephen King and Dean Koontz.

DOES A NOVELIST HAVE TO STAY IN A PARTICULAR GENRE OR CAN HE WRITE WHATEVER HE WANTS—A ROMANCE, THEN A PARANORMAL THRILLER, THEN A MYSTERY?

Of course, a novelist can write any book he wants. But if he chooses to hop like a frog from one lily pad to another, nobody’s ever going to read any of them. Hard truth here, folks. To be successful, a writer must stay within his genre. Before you start painting your protest sign you need to remember that nobody holds a gun to a writer’s head and forces him into a particular genre. Writers get to pick. But once you pick, you need to stick with it.

WHY?

Because if you don’t, you’re breaking your promise to your readers. When a reader likes your first book enough to purchase your second, he has a right to expect that the two will be reasonably similar. If Suzie Snodmotz bought your historical romance and loved it, she will be unpleasantly surprised when she purchases your new novel, Dark Love, and discovers that it’s dark because there are zombies, vampires and space aliens in it. After that experience, she won’t buy your third novel, no matter what it is.

It’s called branding and I’m not talking about the mark you burn into the backside of a cow with a hot poker.

Think Stephen King—what’s his brand? Suspense/ Horror. He wrote a book called The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon that was not in his brand and it sold less than any book he ever wrote.

John Grisham. His brand is legal thriller. When he wrote The Painted House outside his brand, the book bombed.

Often it takes a writer a book or two to settle into a genre. It did me. But once you find your preferred lily pad, you need to build a house on it, plant a garden and put up a white picket fence. From now on, it’s home.