Ninie Hammon's Blog, page 6

January 9, 2013

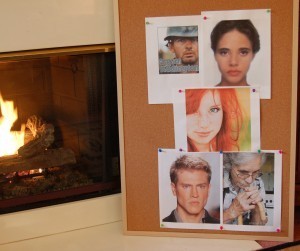

Five Strangers Stare At Me

As I type these words, five people stare at me from the other side of the room, four grownups and a little red-haired girl.

As I type these words, five people stare at me from the other side of the room, four grownups and a little red-haired girl.

One of the grownups is a soldier. His name’s Grayson, a young man, but his face is worn and haggard, his eyes older than his years. He looks hollow and burdened and oh, so very tired.

The other young man is quite the opposite. Carter is clean-cut and commanding. His face is severe only because it is one of those bony faces, high cheekbones, patrician nose, square jaw, that is stern even in repose. The kind of face a smile can light hotter than a bonfire.

Marian, the young men’s mother does not look well. Her hair is the color of a gun barrel and hangs limp around her face, her eyes are sunk deep into dark hollows, cross hatched by a web of wrinkles. But her skin is more than wrinkled; it sallow. Her eyes are more than sunken, they’re red-rimmed. She’s obviously sick, and whatever it is, it’s bad.

Piper is Grayson’s wife. She is dark, like there must have been some Cherokee in her linage somewhere, shiny black hair—long, held in a ponytail that stretches to the middle of her back. Hers are the kind of plump, red-without-lipstick lips men grow stupid over and her eyes are dark and mysterious, so large she resembles the 80’s pictures of big-eyed dolls. Studies have shown that humans are naturally attracted to creatures with big eyes. It’s why we love babies of all kinds—our own along with puppies and fawns. Piper has eyes like that. Look in, fall in, and you could drown in the depths of them.

The little girl is by far the most striking of the four. Hafwen looks like a life-sized raggedy Ann doll. Her hair is the color of the flames rising from the fireplace nearby. Her eyes an odd shade of green with yellow around the irises so it looks like there are daisies in her eyes. Long lashes—black, not the red of her eyebrows, and a spray of sequin-sized freckles on her nose, but only on her nose. There’s a little bit of a smile on her face, just a hint, like maybe she knows a secret, like maybe she knows something wonderful and mysterious that you don’t, that you don’t even know you don’t.

The four people—Grayson, Carter, Marian, Piper and Hafwen—are the characters in my WIP (that means work in progress), they’re the people who will come to life in When Butterflies Cry. But they really are on the other side of the room looking at me. I’m not imagining them.

All the other things I’ve told you about how I write a novel are the trial-and-error methods I’ve used for six years as a novelist and another 25 as a professional journalist. This particular technique is brand new. I’m trying it for the first time with When Butterflies Cry. I have put up pictures of the main characters on a a bulletin board and they stare across the room at me while I write.

I got the idea from my son, who is a Christian film maker. I went by his office one day just before he started casting a movie and happened into the conference room. The names of the movie’s main characters were printed on a a big bulletin board. Half a dozen pictures—from newspapers, magazines, head shots, etc.—were pinned beneath each name. My son explained that he needed to know the “look” he was after, that long before auditions, he had to know what he was looking for.

That made sense to me. So as soon as I had written the synopsis of the book I’m working on, I started scouring magazines and the internet for my characters. It took a surprisingly long time to find just the right people, but I knew instantly when I’d found one. Now, every day they watch me tell their story.

Is it a good practice to have pictures of your characters? Does it help you get more into their heads to see their faces? Does it keep you focused, and help you not to stray from the description you gave on page 3 when you’re on page 300? Or is it stifling? Does lit limit your creativity? Does your mind need a blank slate on which to paint your characters, not a real-life image?

I didn’t know the answers to those questions when I started this novel—or when I began to write this series of blog posts months ago. Now I do. The verdict is in: I suspect I will never again write a novel without pictures of my characters watching over me as I write! It has been amazingly encouraging. As I’ve created their lives, they have come to life for me. In the beginning, they were five strangers—just like all our characters are in the beginning. But not anymore. Now, these people are family.

January 3, 2013

Line Up The Pearls

In my head, I see each scene of a novel as a pearl.

In my head, I see each scene of a novel as a pearl.

A pearl is born in conflict. Something, some irritant, a grain of sand or a tiny piece of grit somehow gets inside the clam. Once it’s in there, it causes instant problems, irritates the soft, sensitive tissue. So the clam secrets some substance, the name of which I don’t know and don’t care about, to coat the irritating piece of grit. Slathers it with layer upon layer of the un-named coating until the offending irritation is covered over, and in its place is a pearl.

Scenes in a novel are born in conflict, too. At the center of every scene is some discordant note, something that invades the status quo, the ordinary world and becomes an irritant. That discord causes such discomfort that something has to be done about it. Conflict and the response to it. That, my friends, is your story.

Once you have written the synopsis of your novel, you know what happens, when and to whom, your next step is to make what I call the List of Necessary Scenes. It think this may be where other writers and I part company. I keep hearing the words “outline” from writing circles and I’m not certain what that means in terms of writing a novel. I don’t write an outline; I make a scene list. I’d suggest you do a little research on outlining a story and you might discover that you prefer that instead. As I’ve said all along, I have no idea how to write a novel. I just do it. Have done it seven times so far. And I’m sharing the how with you. But if it doesn’t seem to fit, by all means go out and see if you can find a method that suits you better.

For me, the scene list is the next logical step after the synopsis. Now that you know the story, what scenes will it take to tell that story? My film-maker son knows exactly what I mean by that question. In a movie, every scene has to be listed and individually, meticulously defined. Where will it be shot? What characters are needed, equipment, special effects, camera angles, etc. As a novelist, you provide all the “camera angles” and “special effects” with words, but before you can begin you have to know what the scenes are.

Surely, you’ve figured this out already, but if not let me own this bit of personal trivia: Ninie Hammon’s picture appears in the dictionary beside the term “low tech.” I’d write with a duck quill on parchment if it weren’t so time-consuming. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to anybody that I don’t make a scene list on a laptop, iPad, IPhone or IAnythingElse. I use Post-It notes on butcher paper. I begin by drawing a timeline. The line starts in the “past,” the timeframe before the book begins. Say your main character is haunted by the time he was supposed to be caring for his little brother and the little boy drowned, and throughout the book, he keeps flashing back to that event. That scene goes on the timeline before the action begins.

You’re only interested in the scenes you will actually use to tell the story. Just because the character went to college for four years and then joined the Navy, doesn’t mean any of that timeframe will be a scene unless it’s relevant to your story. But what scenes are relevant?

In Five Days in May, Mac, a minister, visits a death row inmate named Princess every day of the last week of her life. Obviously, every one of those visits will be an individual scene. As will all the flashbacks that occur within those visits when Princess reminds Mac of his wife and he flashes back to when she died. Or when Princess remembers the little sister she was convicted of murdering.

I use one Post-It note for each scene, different colors for each character from whose point of view that scene will be told and then stick the notes on the timeline where they belong. When I’m finished with that process, I have the whole book laid out in chronological order before me. But that DOES NOT mean that’s the way I’ll tell it. Once I have the timeline of scenes to look at, I can decide exactly where I want to start the story. And it can be anywhere on the line. You can move back and forth along the line at will so long as you make it clear to the reader where you are, what’s happening in real time and what is a memory.

As I go through and decide where the story will begin and where I will proceed step by step from there, I make my official List of Necessary Scenes. What is Scene One in the book and Scene Two and Scene Three—not the chronological order of events, but the order in which I’m going to tell my reader what happened.

My job, then, is to write one scene and attach it to next and the next, like pearls on a necklace, each one born in conflict.

So what is the difference between a scene list timeline and a Character Timeline? Glad you asked. We’ll talk about that next week.

December 26, 2012

Take Your Reader On A Journey

In my first blog for December, we talked about seat-of-the-pants writers, that rare breed of writer who sits down at a keyboard … and writes a novel, with little or no planning. I said they are rare, and later heard from a whole herd of them that they absolutely are NOT rare, thank you very much! Even so, most of the rest of what I’m going to say about how to write a novel will be directed at the larger group of writers out there who—like me—plan out what they write before they set to work.

In my first blog for December, we talked about seat-of-the-pants writers, that rare breed of writer who sits down at a keyboard … and writes a novel, with little or no planning. I said they are rare, and later heard from a whole herd of them that they absolutely are NOT rare, thank you very much! Even so, most of the rest of what I’m going to say about how to write a novel will be directed at the larger group of writers out there who—like me—plan out what they write before they set to work.

So, where does that plan start? It starts with the plot. It starts with the story.

Two schools of thought on this. There are those who say you should go from simple to complex. And there are those who say you should go from complex to simple. Plan A makes the most sense to me.

Write down what your story is about in one sentence. Don’t go postal on me, here. I’m serious. If you can’t tell me—more importantly, if you can’t tell YOURSELF—what your story’s about in a single declarative sentence (without a bunch of clauses and phrases—that’s cheating) then you don’t have a clear enough understanding of your story to write a novel about it.

For example:

The Memory Closet: A woman risks her sanity and her life to remember her childhood.

Home Grown: A journalist declares war on marijuana growers to save her community.

The Last Safe Place: A novelist fights a deranged fan to save her son.

Sudan: A journalist joins a father’s desperate effort to rescue his daughter from slavery.

See, it can be done.

The next step is to expand that sentence (called a logline) into a paragraph. Then into a one-page synopsis. Then into a two-to-four page treatment, in which you describe what happens to whom, how and when.

One of my favorite activities after I finish a novel is to go back and read that original synopsis—and see how little resemblance it bears to the finished product. It is my belief that once you start writing, a story takes on a life of its own. My characters always hijack my story and take it in directions I never dreamed it would go. But you have to START somewhere, and that somewhere is a synopsis.

The other school of thought on this says you should write down everything that happens in your story—a treatment—and keep condensing it until you end with one sentence.

I can almost hear you howling in pain. I won’t bother to explain here that if you ever plan to get a book contract on your great American novel, you’ve going to have to be as good at condensing your story as you are at telling it. Most literary agents/publishers aren’t interested in plowing through an entire manuscript from an unknown novelist. They’ll read a synopsis … maybe even a treatment. If that impresses them, then they’ll ask to see the whole shebang.

But even if there were no publishing house mandate, even if you never intend for anybody but your immediate family and the guys on your bowling league to read our novel—YOU have to know what the story’s about—clearly and succinctly. That’s the bare bones of your novel and unless you can understand and articulate that clearly, you’ll wander off on all manner of rabbit trails and never engage your reader in the drama of your tale.

When you write that one sentence, when you boil the whole thing down to a handful of words, you’ll notice something. (At least you will if your story’s any good.) You’ll see that in its most elemental form, your story is about conflict. It is somebody fighting against something. When you write the longer versions you’ll see that your story is about change. If your main character emerges from the conflict the same man he was when he started, you have no story, at least not one anybody will want to read.

You see, the fine art of story-telling boils down to taking your reader on a journey. You drag him into the story by making your characters so real the reader cares what happens to them, and then the reader travels through the story at your character’s side, fights alongside him, changes along with him.

In the end, neither your character nor your reader, will ever be quite the same again.

December 21, 2012

Another massacre like Sandy Hook almost happened

The parents of the children massacred in Sandy Hook Elementary School a week ago today had no idea their little ones were in danger.

The parents of the children massacred in Sandy Hook Elementary School a week ago today had no idea their little ones were in danger.

The parents of children in a South Carolina elementary school four years ago had no idea their children were in danger, either, would never have dreamed that a mentally unstable gun nut had his car loaded with automatic weapons and was prepared to chain the school doors shut from the inside so he wouldn’t be interrupted. And so his prey could not escape.

It began on a normal school day in a suburban community near the state capitol. A father walked into the building, said he’d come to pick up his son. But he was not the custodial parent, it had been an ugly divorce and the man had caused trouble before. When the principal refused to let him take the child, he got angry, cursed at her and stormed out. The man returned the next day with the same demand and when she refused a second time, he said he would come back and kill everybody in the building. He left the school, went home and loaded the trunk of his car with hand guns, assault rifles and ammunition. He also loaded up heavy chains and padlocks to secure the school doors once he was inside.

But you didn’t read about the massacre of dozens of small children four years ago. The families of those youngsters were not devastated by a blow from which they’d never recover. The whole country did not go into morning for a grieving community. A South Carolina police officer shot and killed the man before he had a chance to commit mass murder.

The parents in that South Carolina community did not know that a police officer saved their children’s lives, or that for the next six months that officer questioned whether or not he wanted to remain in law enforcement. Although he’d spent years in the military and was a combat veteran, this gunman was the first person he’d ever shot at such close range the man’s blood splattered in his face.

I know this police officer well and he would not allow me tell this story unless I promised not to use his name or identify the community where he serves. “If I could, I would erase that whole day from my memory,” he told me yesterday. “I’m not proud of killing a man.”

The officer did not act alone, of course. He was a member of the SWAT team called out when the gunman threatened the school. The principal had called the police the day before when the man went into a rage and officers from several jurisdictions had been searching for him ever since. Now, they deployed a barricade of officers around the school—and then got lucky. A neighbor questioned by police the previous day called to report that the man had returned home.

As the SWAT team approached the man’s house they passed his car. The trunk lid was open. Lying inside were enough weapons and ammunition to take down a small army, heavy chains and padlocks.

When the leader of the SWAT team stepped from the living room of the man’s house into the hallway leading to his bedroom, the gunman opened fire. His first round slammed into the Kevlar vest on the first officer’s chest. The force of the bullet spun him around and knocked him breathless to the floor. The second round caught the second officer in the thigh. But the gunman didn’t have a chance to shoot the third SWAT team member. Still unable to breathe, the lead officer rolled over on the hallway floor, lifted his rifle and fired three shots at almost point-blank range.

I don’t know if the parents in that community ever really understood how much danger their children had been in. There was news coverage of the event, of course, but they might not have put it together in their heads, might not have grasped such a horror could actually happen. Until Sandy Hook, how many of us could have countenanced that kind of evil?

I don’t know if they realized that a group of brave police officers put their own lives at risk to save the lives of who knows how many children.

And I wonder how many times a similar scenario has been played out in other communities across America. In Iowa, maybe. Arizona. Maine. Anytown, USA. How many times has a thin blue line been all that stood between our children and the forces of insanity, depravity and evil that lurk out there just beyond our ugliest nightmares?

I don’t know the answer to that question. But I do know that the next time I see a police officer, any police officer, I’m going to tell him thanks.

December 13, 2012

A Popcorn String Christmas Story

The spaces between the yellowed kernels get bigger every year where the knots of popcorn have crumbled away. The cotton sewing thread grows more and more fragile. But then we weren’t making anything to last the Christmas of 1973. Just popcorn strings, decorations to hang on the tree that year and then throw away. The strings were temporary, like the lives of those who made them.

The spaces between the yellowed kernels get bigger every year where the knots of popcorn have crumbled away. The cotton sewing thread grows more and more fragile. But then we weren’t making anything to last the Christmas of 1973. Just popcorn strings, decorations to hang on the tree that year and then throw away. The strings were temporary, like the lives of those who made them.

* * * * *

Both the little boy and the old woman had daisies in their eyes. I remember noticing that for the first time as the 3-year-old looked up adoringly into his grandmother’s face. The little boy had inherited her deep hazel eyes, with gold highlights that sparkled like the pedals of a flower around a black center.

And I remember noticing how at home in her hands the needle and thread looked. Whenever I tried to sew, I was so clumsy I’d poke myself in the finger, drawing blood so the child would offer to kiss it to make it well. But she never poked herself, not once the whole time she sat in the wide oak platform rocker, balancing a squirming child in her lap as she strung lengths of popcorn to put on the Christmas tree.

There was no snow on the ground outside the windows as she worked. Clouds the color of pewter hung just above the treetops, dripping dreary winter drizzle into the red Mississippi mud. The magnolia tree in the front yard still had a few yellowed blossoms scattered among the seed pods. The grass was still green. It was a strange, disorienting first-Christmas-away-from-home for a young couple and their 3-year-old child. The only sense of family and tradition in the season was the grandmother’s presence, the sight of her arthritic hands stringing popcorn on long pieces of cotton sewing thread, her off-key voice singing Christmas carols in the comforting Texas twang that was already beginning to fade into Deep South mush in the speech of the towheaded youngster in her lap.

When each popcorn string was complete, it was placed just-so on the tree, with much backing-up-and-eyeballing to make sure the drape and swag were perfect enough to satisfy and imperfect enough to imply a lack of planning and a carefree spirit. The little boy got to eat all the candy canes whose position on the tree interfered with the popcorn strings, and he crawled around on the carpet beneath the tree, munching happily on stray pieces of popcorn gleaned from among the fallen pine needles.

That Christmas is etched in my memory with rich, joyful laughter, the smell of hot cider and home-baked cookies and Texas chili bubbling on the stove. The grandmother’s eyes never strayed far from the little boy. She slipped him extra cookies when she thought I wasn’t looking. She pretended not to notice when his squirming on her lap pained her arthritic legs. She hugged him tight and dried his tears when she left to go back home to Muleshoe after Christmas, telling him that she’d be back, that they’d make new popcorn strings for the tree next year.

But they didn’t. Her heart failed in May. She died in a Texas nursing home without ever seeing the little boy with flowers in his eyes again.

* * * * *

The popcorn strings are always the first decoration to go on the tree. Right after the lights. My three sons know that. They’ve always known. It’s been that way every Christmas any of them except the oldest can remember. They also know the strings are precious beyond measure to their mother and their oldest brother. And that the strings are fragile and growing more fragile with every passing year.

And they know the story. But it usually gets told every year anyway. The story of how the first Christmas after the death of their grandmother—the grandmother two of them never knew—was a very sad Christmas. And how their mother discovered the popcorn strings the grandmother had made the year before, tucked away in one of the Christmas decoration boxes.

I never did find out, I’ve told them for almost 40 Christmases now, how it was that the popcorn strings wound up in the Christmas decoration box. I know I intended to throw them away. In fact, I thought I did throw them away. But apparently their oldest brother wanted to keep them and sneaked them into the box. He does not remember.

All I know is that when I spotted them in the box, I began to cry. I cried a long time, great gulping, heaving sobs. Then I took my 4-year-old son by the hand and together we put the strings on the tree with the other decorations—in my mother’s memory.

It has been the same every year since. When the oldest went away to college, the popcorn string tradition passed to my middle son. When he joined the Army, the job fell to the youngest. Even after they were all gone, one or the other of them always has been home at Christmas to put the strings on the tree.

The little boy with daisies in his eyes is 42 years old now and has five children of his own. After Christmas last year, his wife repaired the strings, interspersed the old, crumbling yellow kernels with fresh popcorn—on new sewing thread. And this year, the popcorn string tradition will pass down to the next generation. My youngest grandson is 5 years old—a year older than his father was the year after my mother died. It will be his job to put the strings on the tree.

Oh, his little hands aren’t as big as his father’s and uncles’ hands. His little fingers won’t be as gentle—he’ll probably twist the sewing thread as he works and crumble some of the popcorn under foot.

I figure his great-grandmother understands.

December 6, 2012

To Plan Or Not To Plan … That Is The Question

I’ve only known a few, which isn’t surprising given that I suspect they’re a very rare breed. They’d have to be because theirs is such a unique gift there couldn’t possibly be many of them. In the writing trade, they’re called seat-of-the-pants writers.

I’ve only known a few, which isn’t surprising given that I suspect they’re a very rare breed. They’d have to be because theirs is such a unique gift there couldn’t possibly be many of them. In the writing trade, they’re called seat-of-the-pants writers.

*Note to my British friends: Yeah, I know what you’re thinking: “You Americans! The proper word is trousers. Pants are … well, they’re under garments!” But the thing is, it’s not my phrase. I didn’t make it up so I don’t get to change it. Besides, “seat-of-the-trousers” writers … just doesn’t have the right zing to it. Sorry.

What I’m about to describe is a massive oversimplification. EVERY novelist is unique, with their own methods, strategies, strengths and weaknesses. We ALL approach and accomplish the task of writing a novel in different ways, but in general terms, here’s how seat-of-the-pants writers differ from the mainstream.

When seat-of-the-pants writers start a novel, they sit down at a keyboard and start typing. Period. They might have a handful of characters in mind. They might have only one. Or they might assume they’ll meet the characters along the way. Seat-of-the-pants writers may have a vague story fluttering on the edges of their consciousnesses, they might have a fairly concrete plot in their heads or they might not have a clue what the plot is or how the story will turn out in the end.

If you are a seat-of-the-pants writer, what I’m going to describe about my method of putting together a novel will seem as absurd to you as putting tights on a sperm whale. It will feel constricting and confining and … downright silly. I know, because I once described my system to a seat-of-the-pants writer. She listened attentively and when I’d finally wound down, she had a one-word response: why? Why on earth did I go to all that trouble? She could no more understand why I had to than I could understand why she didn’t.

The difference between seat-of-the-pants writers and the rest of us is in planning. To a greater or lesser degree, other novelists plan out their work. Some have massive outlines and elaborate file-card systems. Some work out the intricacies of their plots on big, erasable white-boards. Others use post-it notes they can arrange and re-arrange. I have always believed that Stephen King’s novel IT had to be masterfully planned because it traces the lives of seven people as adults and as children, switching back and forth from one character to another, one time frame to another. I can’t imagine that anybody could keep that amount of complexity in their heads.

I developed my own system of planning a novel. That was massively stupid. I’m sure I could have saved myself untold HOURS of time and energy if I’d just done a little research and found out how other writers do it. Let me URGE you to do just that. Why re-invent the wheel? Don’t just go by what I’m going to describe in the weeks to come—go out and read how other writers do it and pick and choose the parts of half a dozen systems that feel right for you.

My system begins at the beginning. It starts with the plot, the story. The story is the engine of your novel. No matter how colorful or lyrical your language, how engaging your characters or how believable your setting, if your plot can’t move it all forward, you might want to consider going into real estate.

Novelists tell stories. No story, no novel. So next week, we’ll discuss just how you grab hold of that story, wrestle it to the ground and hog-tie it.

November 27, 2012

Merry Christmas NOT Happy Holidays

I walked into a store yesterday and the sales clerk greeted me with “Happy Holidays!” I ground my teeth, of course. It’s CHRISTMAS, folks. That’s what we’re celebrating. Then I got home and read an email from a friend about the principal of the school where her children attend–who zapped the celebration of all holidays! And I was off to the races.

I walked into a store yesterday and the sales clerk greeted me with “Happy Holidays!” I ground my teeth, of course. It’s CHRISTMAS, folks. That’s what we’re celebrating. Then I got home and read an email from a friend about the principal of the school where her children attend–who zapped the celebration of all holidays! And I was off to the races.

Seems the principal decided that because of “diversity” concerns, students would not be allowed to celebrate any holidays at all. None. Not Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Thanksgiving, Easter or Halloween. Not even Groundhog Day.

When parents pitched justifiable fits about her decree, she issued a statement explaining that her decision was an effort “to respect each individual’s uniqueness but also to help us look for and celebrate those things our uniqueness has granted us in common.”

Say what?

The only time that kind of education-speak gobbledygook passes for reason is when you’re not paying attention. And America hasn’t been paying attention to the homogenizing of our schools—and our culture–for way too long.

Though the principal claims banning school holidays is an effort to respect each individual’s uniqueness, it actually accomplishes the exact opposite. Far from respecting uniqueness, the ban venerates the lack of it. The decision to “celebrate those things we have in common,” is actually a determination to shun anything and everything that’s uncommon—that’s special, different, unique. Hers is the siren song of bland, beckoning us to a world of blah.

Of course, dull is safe. Oh my, yes.

There are landmines everywhere else. Witness the bludgeoning of communities that dare to celebrate Christmas. Put up a manger scene, sing a Christmas carol or send a kid to school wearing a “Jesus is the reason for the season” pin, and the wrath of the social sanitizers will descend on you like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

I see all around me hostility to the celebration of Christmas I never dreamed I’d see, antagonism that goes beyond jettisoning manger scenes and forbidding school kids to sing “O, Little Town of Bethlehem.” As I’m sure you’ve noticed, every major retail chain has instructed employees to bleat “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas.” After all, any reference to Christmas might offend a Muslim or a Buddhist—or an atheist. And the culture police have become so maddeningly determined not to offend anybody that the result is offensive to everybody. The historical reality that Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Christ—not the birth of Mohamed or Buddha—has become totally irrelevant.

I suppose it was predictable that the zeal to eliminate Christianity from “that holiday at the end of December” would spill over into other holidays as well, that schools and other public arenas would mow down other celebrations like a gardener with a new weed-eater—all in the name of diversity, of course.

It has been my experience that if power can be abused it usually is, that common sense is neither common nor sense by the time it goes through the blender of political correctness, and that if there is an extreme position to be taken, somebody probably will.

Complainers aren’t hard to find. No matter what the issue or occasion, you can find somebody who doesn’t like it. Somebody whose “rights” are violated by having to listen to a prayer at a football game—or an inauguration—or pass some guy ringing a bell and holding out a bucket at Christmastime. Somebody who is offended by any reference to God or Jesus Christ that is not an obscenity. All those somebodys combined have been quietly snipping away at all the sharp corners of our culture. Over time, they’ve created an atmosphere in which a handful of offended people can call the shots for everybody else.

In a misguided effort to “protect” the few, the rights of the many have been trampled. If we continue to toss out holidays, blow off traditions and sanitize festivities, what’s left will be a sterile environment where there’s no longer anything unique to celebrate.

That’s not diversity; that’s homogenization.

The Japanese have a saying that once stood in stark contrast to the American philosophy of rugged individualism—“If one nail sticks out of the board, pound it down.” More and more, that philosophy has come to typify our culture. The offended few have long been on a crusade to pound down any spiritual nail they can find. But along with the spiritual, they’re pounding down the celebrations honoring the rich variety of America’s multicultural heritage, too.

I, for one, do not intend to go gentle into that good night. When the sales clerk wished me “Happy Holidays,” I replied with a far cheerier, “Merry Christmas.” She smiled and said, “Yes, Merry Christmas.”

But she said it quietly. So no one but me could hear.

*Next week, we’ll talk about novel-writing. Promise.

November 15, 2012

Always Always Language

It’s always, always on my computer desktop and the top Note in my IPhone. I keep it handy because my Always, Always Language List is very important to me. The double “always” is to remind me of two things: how often I should listen for great language usage and how often I should WRITE IT DOWN when I hear it. (You think you don’t have to write it down, that you’ll remember. Trust me on this one, people—you won’t.)

It’s always, always on my computer desktop and the top Note in my IPhone. I keep it handy because my Always, Always Language List is very important to me. The double “always” is to remind me of two things: how often I should listen for great language usage and how often I should WRITE IT DOWN when I hear it. (You think you don’t have to write it down, that you’ll remember. Trust me on this one, people—you won’t.)

Wherever I am, whatever I’m doing, I always, always jot down cool phrases that I hear or read or dream or make up. Right now, the list is at 30,000 words. The information is geological—oldest on the bottom. I cross out whatever I use in a book but don’t ever remove anything. Never know when you might need a variation of something you’ve used before.

Here are the current top items. They’ll move down if I hear anything really cool today.

The shadow tacked to his heels was long and grotesquely thin. (From a novel I’m reading.)

He had this infectious laugh, a cross between a hyena and a saxophone. (Overheard in a restaurant.)

If what doesn’t destroy you makes you stronger, I should be able to bench press a Buick. (TV comedian.)

The wind hurried wet leaves past her feet that tickled her bare ankles like kittens with milk on their whiskers. (Made it up while running.

Frost polished the night until it sparkled. (I think I dreamed it; I know I jotted it down right after I woke up.)

Ok, I hear it. The Indignation Alarm is going off in your brain, clanging ding, ding, ding! You’re thinking, “I thought every word in your novels came out of your own head. But with this language list thingy—are you saying … they didn’t?”

No, that’s not what I’m saying at all. Of course, every word in my novels comes out of my head. But the words in my head came out of the world! Everything I’ve ever heard or thought, or dreamed or read is churning around between my ears and somehow comes out in a totally unique way on the page that is distinctively Ninie Hammon.

What jotting down great language does is make you aware of it all around you. It primes the pump, gets your creative juices flowing, creates a rhythm of syntax in your head that flows out in your own distinctive way on the page. Then, in your own words, you come up with:

“Trailer houses, alone or in small herds, were affixed to the mountainsides with white stickpins. He’d heard the satellite dish had been declared the official flower of West Virginia and it was clear the seeds had blown across the state line.” Black Sunshine

“Everything Piper knew about coal mining would have fit in a bikini with enough room left over for Mahalia Jackson.” When Butterflies Cry

“Theo would rather face down a serial killer with a sinus infection and poison ivy on his privates than ride up that goat trail in a jeep!” The Last Safe Place

Language is what you’ve got, it’s all you’ve got, the bricks and mortar of your story. You have to be a master at it. One way—one of the BEST ways—is to jot down every cool usage you hear or read, every sentence that makes your heart sing. Then analyze what’s so good about it, why it appeals to you. Read it over and over to get the rhythm into your head. When you’re writing, something similar to what you wrote down may wind up on your page. That’s ok, too. It’s not any more plagiarism than milk is plagiarizing grass. There was a cow in between the grass and the milk. Not to beat a dead analogy, but you’re the cow.

There are other pre-writing activities besides making an Always Always Language list that you need as preparation before your fingers type, “Once upon a time…” We’ll talk about those next week.

But first, I have a question for you. Can you think of even one cool usage of language—in the grocery store, on television, out of your grandson’s mouth—that you’ve heard in the past week? What was it?

November 8, 2012

You Need A Book For Your Book

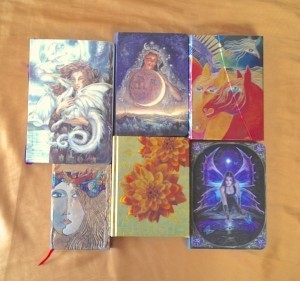

The one for Sudan got lost when we moved from Surrey to Buckinghamshire. But I remember it. It had a soft, brown leather cover. Dignified, befitting the seriousness of the subject matter. The rest didn’t reflect the content, though. They were just cool books.

The one for Sudan got lost when we moved from Surrey to Buckinghamshire. But I remember it. It had a soft, brown leather cover. Dignified, befitting the seriousness of the subject matter. The rest didn’t reflect the content, though. They were just cool books.

That’s the first thing I do when I start a novel. I go out and buy a Book For My Book. No, not Novel-Writing for Dummies, a book with no words in it at all. Because over the course of the next four to six months, I’m going to fill it with words, dates and numbers. Lots of them.

Every one of my novels has had one. As you can see from the picture, they are all different, though at the time, I always thought that the Book For My Book for the novel I was just starting was the prettiest one I’d ever seen. And it needs to be something that strikes your fancy because you’re going to be looking at it many times a day for many months. I spare no expense—meaning I don’t settle for a spiral notebook with Justin Bieber’s picture on the front, the kind used by junior high kids in English class. But I don’t go looking for a diary made out of yak leather with hand stitched parchment pages, either.

The reason getting a Book For My Book is the first thing I do when I start a novel is that I keep track of my time from the very beginning, and that’s what the book’s for. It’s to keep track of your time—or your word count, whichever side of that coin you happen to land on.

Anybody can eat an elephant. You just have to take one bite at a time. Writing a novel is an African elephant, a bull elephant, an overweight bull elephant. On steroids. The spoon you’re going to use to eat that puppy one bite at a time is the Book for Your Book.

Writers fall into two categories when it comes to tracking or measuring their writing. Some have a daily quota of words. They sit down at their writing desks, or stand as I do, and they won’t allow themselves to leave until they’ve written X amount of words. That method is particularly attractive because it allows you to plan with some degree of accuracy when the book will be finished. If you write 1000 words a day and you’re shooting for a 100,000-word manuscript, then you know it’ll take you 100 working days.

That method never appealed to me. I tried it, but found myself stretching paragraphs out unnecessarily just so I could make the daily word count. And I find I need to go back and read at least some of what I’ve already written—to get me back into the world of the book–before I start every writing session. In the word-count method, that time doesn’t count. Neither does the time it takes to edit while I’m reading what I wrote the day before, because there’s no way to read it without seeing immediately something that needs to be changed.

So I opted instead for a time book. I have determined that I will work for eight hours every day. Period. I clock in like a factory worker in my Book For My Book: 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.—four hours; 7- to 9–two hours; 11 to 1–two more hours. I picked that method in the beginning because I wanted to know how long it took to write a novel, so I timed the first one to give me some kind of road map for the second.

I also like this method better than the word-count method because I really don’t care how many words the novel is. Yeah, publishers want between 80,000 and 100,000 for your first novel. Hover around 100,000 and it’ll keep them happy for subsequent novels. But I learned as a journalist that a story has to be like a woman’s skirt—long enough to cover the subject and short enough to keep your interest. So my novels have varied considerably in word length. Sudan was 120,000 words, The Memory Closet , Five Days in May, Black Sunshine and The Last Safe Place have all hovered around 105,000 to 108,000 words–not by design, it just worked out that way. Home Grown was 115,000.

When I tracked the time it took to write each draft of all my novels, I discovered there was no consistent “normal” time there, either. The CFD (stands for Crappy First Draft; most writers call it the SFD) of Sudan took 650 hours. But it was the first and I was learning on that one. The CFD of the next book, The Memory Closet took 260 hours. But four books later, the CFD of The Last Safe Place took 392 hours. Go figure. Total writing times were all over the map, too. The longest, of course, was Sudan at 1,070 hours. Shortest was Five Days in May at 568 hours.

The point of the Book For Your Book is that you have to keep track—of something. Hours worked. Words written. Doesn’t matter, but you must hold yourself accountable, or that great American novel floating around in your head will never find its way onto the page.

Next week, we’ll talk about what happens next. After the Book For Your Book, THEN what do you do?

November 1, 2012

Stephen King’s Boys in The Basement/Ninie Hammon’s California Raisins (Part 2)

“Heard it through the grapevine, ta-da, ta-da…heard it through…” Got to be one of the most golden of oldies. Listen to it in your head. “… the grapevine, ta-da, ta-da.”

I suspect the last original thought anybody ever had was probably something like: “I think I’ll call that one with the tall, skinny neck a hippopotamus and the short, fat one a giraffe …naaa, make it the other way around.”

What I’m going to explain is not an original thought. It’s not my idea. I got it from my son, who is a Christian filmmaker. And I don’t think it was his idea either. But the origin of the idea isn’t important. What is important is that it makes a whole lot of sense.

But first, I promised last week I’d tell you about the California Raisins who are my muses. When I went to work as a reporter at The Lebanon Enterprise in the 1980s (I was three or four years old at the time.), I passed a Hardees every morning on my way to work. Ok, it wasn’t exactly between me and work…in fact, I had to pass work to get to it, but I couldn’t help myself because Hardees had cinnamon raisin biscuits on their breakfast menu. (Along with Krispie Kreme doughnuts and British yogurt, I will eat cinnamon raisin biscuits in Heaven.) At the time, Hardees gave away a little plastic California Raisin guy with every order. I collected roughly ten thousand of them. I kept a full set of four. They lived beside my typewriter (If you’re younger than 30, Google “typewriter.” There’ll be pictures.) and later my computer for the next quarter of a century. I told people I couldn’t write without them, which was true. Eventually, they became like a lucky penny, a baseball player’s special bat or a golfer’s putter. Couldn’t write unless those little purple dudes were singing silently for me. But I also told people the Raisins were the source of the stories in my head, and that wasn’t true.

Have you ever thought about the fact that story—and laughter—are the only elements of our common humanity that transcend culture, language, geography—even time. Cave paintings of stick-figure hunters with spears and saber-toothed tigers are what? Stories! Every people group on the planet tells stories. In every language. Why is that? I believe the answer’s pretty simple. I believe God hardwired story into human beings, designed it as a doorway for real truth into the human heart. I believe God created us to respond to story and then used stories to reveal Himself to us.

Stephen King may believe his stories come to him from The Boys in the Basement; I may joke that mine are delivered by the California Raisins. The truth is story itself is part of our hardwiring, it was issued as standard equipment to every human being.

But while story itself may be hardwired, plots are not. Characters are not. Structure is not. Telling stories may be intuitive, but HOW you tell a story is learned. We have all read enough stories to be able to sense something about characterization, plot, tension, foreshadowing, climaxes, pace and timing. However, it’s one thing to recognize it when you see it; it’s another thing altogether to create it out of thin air. And it’s in another whole galaxy to take your hardwired sense of story and your life experience of story and apply that in a systematic, structured way to the story floating around in your head.

I promised in my first blog that we’d talk here about the creative process, about where stories come from. I also said we’d talk about how to formulate an idea big enough for a novel, how to set it up, design it and execute the design.

If you’d like to join me here in the weeks to come, we’ll do just that. Pull up a chair, sip your tea or coffee or Diet Coke and we’ll chat. If you’ll ask questions, I’ll answer the best I can, and we’ll keep at it until we make some sense of this novel-writing thing. We will heed the words of that great theologian Dorie The Fish…”just keep swimming, just keep swimming, just keep swimming …”