Ninie Hammon's Blog, page 2

November 24, 2013

There’s ONLY ONE WAY to create unforgettable characters

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #10 THE ONLY WAY

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #10 THE ONLY WAY

This is the final in a ten-week series about characterization. We’ve talked about all manner of techniques and skills but here, at the end of it, we need to get real. How do you create unforgettable characters?

You might not like the answer to that question.

Creating characters isn’t the same as designing a plot, describing a setting or developing a theme. You can come up with all that in your head, use your brain and never engage your emotions. Actually, you can do that with characters, too, and if you’re clever enough, your reader might even be interested in what happens to them. But if you want Loyal Reader to care what happens to them, to climb into the book and live the experiences with them, to view them as family, to miss them when the story’s done and to carry them in his heart for the rest of his life, you have to engage his emotions, not his intellect. There is only ONE way to do that. You have to pull your characters up out of your own soul—from one of three places:

YOUR PAST:

Who were you? No, not the you everybody knew—the you nobody knew. The you on the other side of whatever mask you wore. What happened to you, hurt you, embarrassed you, shocked you, humiliated you? What awful, unforgivable mistakes did you make? Who did you hurt? What bridges did you burn?

What are your memories? Examine them. No, not the prettified daydreams, water color paintings that cover up the ugly you’d rather forget. I’m not talking about skating on the glossy surface of remembrance. I’m talking about climbing through the water color into the ugly, to see it, smell it and feel it. Were you sexually abused?

Were you sexually abused?

Bullied?

Hated for your skin color or ethnicity?

Or were you ignored, dismissed, a shadow in your family’s life that nobody ever really looked at.

Were you pampered and spoiled and totally unprepared for a world that didn’t give a rip whether you lived or died?

Were you the fat kid everybody made fun of? The un-athletic kid who always sat on the bench? The ugly girl nobody asked to the prom?

You have to plumb the guts of who you used to be and rediscover what all those experiences felt like. It may take some digging. You likely buried them deep. But they are treasure, your treasure, and you must reclaim them.

What frightened you, scared you so bad you almost wet your pants—maybe did wet your pants? What ate a hole of terror all the way through your belly to your backbone? No one knows fear the way a child does, the helpless, vulnerable way a child does.

Own all the visceral emotions of your past and USE them.

YOUR PRESENT

Are you who you thought you’d be when you were sixteen? What dreams did time dash on the rocky coastline of reality? What promise still lies unfulfilled?

Who let you down you knew you could depend on? Whose trust did you betray?

Twenty, maybe 30 pounds heavier probably wasn’t what you dreamed of being when your were sixteen. Neither was broken, disillusioned and scared. But what frightens you now is different from what frightened you before, right? Now you fear for others—your children, your spouse. What are you afraid will happen to them? When nightmare images wake you in the midnight dark, heart pounding, gasping—what do you see?

What did you do you now regret? What didn’t you do you wish you had? What are bitter you about? What makes you feel helpless, hopeless and totally lost?

What did you do you now regret? What didn’t you do you wish you had? What are bitter you about? What makes you feel helpless, hopeless and totally lost?

What can’t you do now you once could do? Sure, your jump shot’s gone, but is your ability to make love gone, too?

How does it feel to look into the mirror and see someone losing the battle against smile wrinkles, bald spots and gravity’s relentless sag?

Are your children tattooed and pierced and contemptuous of all the values you taught them? Do they resent you because you couldn’t make it perfect for them when you were doing the best you knew how?

Did your husband trade you in for a trophy wife?

Did your husband trade you in for a trophy wife?

Did your wife run off with a tennis pro?

Or did you just wonder, worry every time he worked late or she had a night out “with the girls.” What did that feel like—no, not the surface easy emotions, the deep, ugly, unspeakable ones.

What have you failed at? What have you lost? What sicknesses, injuries or physical pain have you suffered?

Dig deep for all those feelings—and USE them.

YOUR FUTURE

What’s it like to face death? To know that if this lump or that pain doesn’t get you something else will?

What’s it like to turn that pivotal age—whatever it is—and realize that the likelihood you’ll continue to dodge the fatal bullet grows less with every breath you take?

What’s it like to turn that pivotal age—whatever it is—and realize that the likelihood you’ll continue to dodge the fatal bullet grows less with every breath you take?

What’s it like to be careful now. You used to climb trees, mountains, careers with wild abandon. What’s it like to walk more slowly, to know that an injury now could put you permanently out of the game?

What’s it like to lose your friends, to watch them drop around you one by one until one day you will be the only one left standing. And will that make you the lucky one? Or are they?

What’s it like to watch your lifelong partner forget who you are? What does an empty house sound like, an empty bed feel like?

What’s it like to watch your lifelong partner forget who you are? What does an empty house sound like, an empty bed feel like?

What’s it like to pick out a casket?

No, I’m not being needlessly morose. I’m focusing on the negatives because the positives—happiness, joy, success—are simple. And positives usually aren’t the stuff of novels anyway. Most novels aren’t about the ones who made it. They’re about the ones who didn’t, barely missed maybe, or perhaps realized when they grabbed the brass ring that it wasn’t what they thought it’d be. Novels are about people who struggle, people for whom life’s abundance doesn’t come easy or cheap. Novels are about people who hurt and what they do about that hurt, about people in difficult circumstances and how they perservere—or don’t.

I seriously doubt anyone reading these words is writing Greek tragedy, but no matter what your genre, EVERY ONE of your characters has some hurt, some brokenness. They’re battling some kind of difficult circumstance or there’d be no conflict in your story. What I’m saying is that you have to find the pain in your own life to be able to write convincingly about pain in the lives of your characters, even though what they’re suffering is an altogether different kind of pain than you have ever known. Everything that’s ever happened to you, everything you’ve ever seen or felt, wanted or lost is what you bring to the characters you create on the page.

What’s the best way to create unforgettable characters? Actually, it’s the only way. Everything else is a technique you can learn, advice you can follow, skill you can acquire. If you want to create unforgettable characters, there’s just one way to do it: you have to give them life. And the only life you have to give them is your own.

Write on!

9e

November 14, 2013

One Critical Tip From Professional Gamblers Will Make Your Characters Unforgettable

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #9 THE TELL

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #9 THE TELL

You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away and know when to run.

You never count your money when you’re sittin’ at the table. There’ll be time enough for countin’ when the dealin’s done.

If these words don’t instantly conjure the image of a crooning Kenny Rogers, his eyes, nose and mouth peeking out a small opening in his all-around surround hair, you might want to check out the nearest community college for a remedial life course.

You know, novelists could learn a lot from professional gamblers. Consider the intensity a pro brings to the observation of his opponents. Does the other player always pick up the cards with the same hand? Does he shove chips to the pile carefully or throw them into the pot. Does his opponent make direct eye contact, stare into space, drum his fingers?

A professional gambler is always searching for his opponent’s “tell.”

He’s watching for a too-broad smile that means his opponent’s bluffing, sudden friendliness that indicates the guy across the table is hoping nobody calls his bluff, or a quiet reserve that’s a sure sign of a great hand. In the world of royal flushes and king-high straights, a tell refers to an unconscious mannerism that gives away a player’s assessment of his cards.

In the world of plots, backstories, and characterization, a tell refers to absolutely nothing. At least not as far as I know. But in NinieLand, a tell is a characteristic that instantly identifies a character, almost like a radioactive chip in the dark. And its repeated use resonates with Loyal Reader, draws an ever more detailed, layered picture of the character in his mind and strengthens the bond between them.

I imagine the common term for what I’m talking about is “quirk.” Go online and you can find lists of them. Here’s one.

*Drumming fingers

*Crossing and uncrossing legs

*Unpleasant, high voice, distinctive laugh

* Making strange faces

*Eyebrow lifting

*Knuckle-popping, eye rolling, limping

*Burping, farting, yawning, eating with mouth open

Some lists give even more detailed descriptions of quirks. You could, perhaps, create a character who:

*Carries a large coin he is constantly rolling over his knuckles

*Regularly looks up at the sky to check the position of the sun/moon and then comments on it

* Bites fingernails, hers and other people’s

* Bites fingernails, hers and other people’s

*Has a weakness for rescuing stray dogs, cats and injured forest creatures

*Strongly dislikes the sound of chewing and hums while eating

*Only drinks from plastic or paper cups and cannot stand the feel of glass in her hand

*Wears only new socks, doesn’t eat anything green or red, uses toenail clippers to trim the rose bushes and lists “Who Stole The Kishka?” as favorite song.

*Responds to every crisis by shrugging his shoulders and saying, “Whatcha gonna do? S**T happens.”

No, I did not make those up. Google “quirk” and see for yourself.

My quarrel with quirks (I could get serious Scrabble points with that phrase!) is that I don’t believe you can give a character a tell like pinning a tale on a donkey. You can’t decide what the tell is and then shape the character around it. A tell must blossom organically from who your character is, what he wants, what he’s done and where he’s going. You must use the character to define the tell, not the other way around.

Once it’s established, you reinforce a tell by its continued use throughout the story. Just remember, a tell is like chili peppers, tax audits and colonoscopies—a little goes a long way.

A tell can be anything you choose. It can be a quality that’s almost indefinable but discernible nonetheless, something observable.

Something as simple as stillness.

She sat as still as a windsock on a foggy morning, simply looked at him, her face benignly expressionless. The moment stretched out, elongated, didn’t seem to be governed by the cranking of the earth on its axis.

Then she spoke. “Yes,” she said. Just the one word, an affirmation almost like an “ahhhh,” a sigh so soft it didn’t disturb the air in the room.

Then reinforce the tell in later scenes.

She walked slowly back to the table and sat down and the absolute quiet and centeredness gathered around her, disturbed bees settling back on the hive.

***

“Well, I finally did understand how you could love that much,” she said.

Princess was wrapped in expectant stillness again, almost … humming—maybe producing a sound that’d cause a dog to whine and scratch at its ears.

He managed to say, “Tell me about her.”

The warm honey of her voice bubbled up out of the center of her perfect quiet.

“She was so beautiful she broke your heart.”

Five Days in May

A tell can be a characteristic behavior or speech pattern. Be creative, though, don’t settle for something as lame as thumb-twiddling, nail-biting or stuttering.

“I’m James Bowman Sparrow, sir, named after my granddaddy, but ever-body calls me Jamey. Well, most ever-body. ’Cept JoJo and sometimes she calls me mow-ron, but she don’t mean nothin’ by it, and sometimes Granny calls me Jamey Boy.” He paused to get a breath. “But you can call me Jamey. The end.”

The monologue was delivered in a cheery voice, but the young man never looked at Will, kept his head down, and his gaze roamed the room like a searchlight on a guard tower, up and down the baseboards of every wall, never move than six inches off the floor.

* * *

Jamey looked confused, wagged his head back and forth and looked at no one. Then his face cleared. “I can use the watch JoJo give me for Christmas, a Mickey Mouse watch and when both the little hand and the big ’un point straight up it plays “M-I-C, K-E-Y, M-O-U-S-E” and that means it’s time for lunch. The end.”

He looked at the bottom of the kitchen chairs as he spoke.

Black Sunshine

A tell can be a physical trait.

Granny sat piano-teacher erect with those big, man’s hands folded in her lap as prim as Cinderella waiting for Prince Charming to ask her to dance

. * * *

“Didn’t we just agree we was gonna work up to that? We got plenty of time.” She reached out and touched his cheek, her big hands soft as a butterfly kiss.

* * *

She continued to maneuver the hooks in delicate movements that should have looked clumsy but didn’t, working so fast it was almost impossible to follow the hooks’ progress.

“I figure if they’s to put needles and yarn in yore coffin during visitation,” Lloyd said, fascinated by the movements of her big, square fingers, “you’d likely make up a right nice sweater ’fore they started shovelin’ in the dirt.”

Black Sunshine

In short, the character-driven, creative and consistent use of a tell is a great way to create characters your reader will remember forever. The key words in that sentence, folks, all start with C.

We’d all love to hear about “tells” you used in your fiction. Do share in the comments below so we can learn from each other.

Write on!

9e

November 5, 2013

One Question: Answer It Well And Your Characters Will Be Unforgettable

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #8 WHAT DOES HE WANT?

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #8 WHAT DOES HE WANT?

To find Nemo.

To save Jews.

To go back to Kansas.

To kill the great white whale.

To destroy the ring.

To catch the one-armed man.

To get back to Andy’s Room.

Every good story begins with a character who wants something.

Somebody Famous said that, not me, so you needn’t bother giving me a byline when you print it on a plaque and hang it on the wall. Which you should, because it’s a character’s overarching desire that will propel the action in your story. And there won’t be much action if you can’t come up with something more spellbinding than gee-I-need-to-get-the-oil-changed-in-the-Buick.

When divers scoop up the little clown fish and whisk him away, his father wants his son back. And all the rest of the action in the movie centers around his efforts to find Nemo. Dorothy and her rag-tag troop of misfits traipse all over Munchkin Land, down the yellow brick road to the Emerald City and into the castle of the wicked witch—all because Dorothy wants to go home.

Arthur Schindler wants to save Jews from the gas chambers. Captain Ahab gives his own life and the lives of his crew in his single minded obsession with killing Moby Dick.

Arthur Schindler wants to save Jews from the gas chambers. Captain Ahab gives his own life and the lives of his crew in his single minded obsession with killing Moby Dick.

Great novels are about characters who want something badly, something that’s massively important to them, and the conflict in those stories springs from the clash between what the character wants and whatever stands in the way of his getting it. That’s why there is no better way for a writer to create unforgettable characters than devising compelling answers to these questions.

What does the hero want?

What is he willing to do to get it?

What will it cost him to give it up?

Or, conversely, what does the character NOT want and what is he willing to do to avoid it?

All the forces of the Dark Lord stand between Frodo and destroying the ring. We only find out the fur-footed little dude is made of sterner stuff than anyone supposed when we see him persevere. Every police department in America plus the dogged pursuit of U.S. Deputy Marshal Sam Gerard stand between Dr. Richard Kimbell and finding the man who killed his wife. We come to care about Dr. Kimbell by watching him struggle through.

Sid, the plastic-soldier torturer, and his evil dog stand between the cowboy doll and the spaceman action figure and their home with the child who loves them. We watch Buzz and Woody bond as they win the day together.

The what-does-the character-want element in your story should be blatantly obvious. It can, in fact, be stated outright.

There’s certainly nothing subtle or tentative about Captain Ahab’s speech to the crew of the doomed Pequod as he stood wild-eyed on the deck, brandishing a harpoon. “I seek the great white whale and I’ll follow him around the Horn, and around the Norway maelstrom, and around perdition’s flames before I give him up.”

Or about Anne Mitchell’s single desire.

Over the years, I’d cataloged hundreds, maybe even thousands of other people’s recollections and filed them away so I could pull one out, dust it off and pretend it was mine whenever people started talking about what they did as children.

Every time I listened to tales of other people’s growing-up years, I felt a tangled mixture of envy and terror. Envy because I ached to have a past, too, a mental library of sunsets at the beach, Christmas mornings, birthday cakes, chicken pox, spankings, hugs and most-embarrassing-moments that were uniquely my own. And terror because I understood that something profoundly evil lurked in the swirling purple of my recollections, in the deepest dark ditch there.

All I want, all I need, all is ask is to remember.

The Memory Closet

But the motivating desire doesn’t have to be stated so long as it is clear and Loyal Reader is never in doubt about what it is. If you’re a beginning writer and you’re not sure exactly what it is your character wants, you might not be ready to write your story yet. Can you state her desire in a single declarative sentence?

Ron Wolfson in Sudan wants to photograph a slave auction. Anne Mitchell in The Memory Closet wants her childhood memories back. Sarabeth Bingham in Home Grown wants to stop the dope growers. Will Gribbins in Black Sunshine wants to confess what he did. Gabriella Carmichael in The Last Safe Place wants to escape the deranged fan. (Five Days in May—stating the real one would give away the switcheroo at the end.)

The hero goes after his goal and forces get in his way—how he deals with those forces defines who he is. But sometimes over the course of pursuing his goal, the goal changes. When that happens, it reveals even deeper layers of characterization. Michael Corleone begins The Godfather bent on remaining uninvolved in the family business, but his father’s near assassination changes what he wants and he ends the story as the family patriarch. Shrek wants to be left alone to live peacefully in all his glorious green orge-ness in his swamp, but as the story progresses, what he wants changes. He wants Fiona.

What the character wants will best reveal who he is if the cost of getting it is high. What Andy Defresne in the Shawshank Redemption wants is freedom. To get that, he spends 18 years chipping away at a wall with a tiny rock hammer, then crawls through a sewer pipe to the outside. The higher the stakes, the more compelling the character and there are no greater stakes than life and death.

In every Indiana Jones movie since 1981, Indy is constantly putting his life on the line to get the Ark of the Covenant/Sacred Stone/Holy Grail/Crystal Skull. And his character is defined by his dogged determination to get what he wants.

Well, that and his hat.

Write on!

9e

October 26, 2013

Four Ways to Reveal Your Character’s Personal Boogie Man

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #7 FEAR

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #7 FEAR

Her thoughts stopped spinning so abruptly they slammed into the back of each other like train cars crashing into a stalled engine.

This wasn’t about her! It never had been.

“That’s just scared talkin’,” Princess said aloud. Her husky voice sounded shaky, but she kept speaking and it grew stronger with each word. “Just fear a-babblin’, talkin’ things it don’t know nothin’ about! Can’t listen to scared. It lies. Scared lies and mad lies and hate lies. But love don’t lie.”

She lifted her head and shouted into the shadows of her cell, “My last night on this earth, I ain’t gonna listen to lies!”

Five Days in May

What is your character afraid of? What your character fears and how he reacts to that fear provides a wealth of insight, a window into your character’s soul. It is a powerful tool to craft characters your reader never forgets. And don’t you forget to scare Loyal Reader, too. Unless your reader is terrified that something awful is about to happen to the characters he cares about, there’s no compelling reason to hang around and see how it all comes out. Making the reader fear The Bad Thing Coming has a name. It’s called suspense.

Writers need to become masters at revealing the fear a character is experiencing and using that fear to add depth and complexity to characterization.

The uses of fear in your novels are limited only by your own imagination. The most obvious, of course, is to heighten tension. We do that by making characters face what they fear most.

In Hunger Games, Catniss is afraid her little sister will be selected as the tribute–and leaps up to take her place when that’s exactly what happens.

The Wizard of Oz is all plotted around characters’ fears. The Strawman’s fear of fire, the Tin Man of water, the Lion of everything and Dorothy of losing Toto.

The Wizard of Oz is all plotted around characters’ fears. The Strawman’s fear of fire, the Tin Man of water, the Lion of everything and Dorothy of losing Toto.

In a suspense novel, you place characters in steadily increasing peril and the reader knows only what the character knows. In a thriller, the character is dropped into a scary situation on page one and often the reader knows what the character does not. The reader watched the guy put the bomb under the car, saw the murderer hide in the cellar. The fear in readers tightens as the un-knowing hero goes blithely into that danger. Loyal Reader wants to grab him and shout, “Don’t do that! Don’t open that … oh, man.”

Here are four ways to show your reader that a character is afraid.

1. THROUGH THOUGHTS:

The audience in a movie has to rely on what they observe to find out what the character is afraid of. As fiction writers, we would be wise to emulate the silver screen and use show-don’t-tell to communicate fear. Don’t tell me Joe’s scared, show me the drink he spilled in his lap because his hands were shaking.

But novelists rock. (You already knew that.) We’re not limited to what Loyal Reader can see. As we talked about last week, we can take the reader into a character’s mind and show him what the character is thinking.

Something profoundly evil lurked in the swirling purple depths of my recollections, in the deepest dark ditch there. Fear of facing that secret trumped the yearning in my heart to be like everybody else and the niggling itch of curiosity.

Fear trumps everything; always does, always has, always will. Fear held me hostage for a quarter of a century. Like a schoolyard bully, it twisted my arm behind my back until I cried “give!” It forced me to accept that my life began at age 11, on my knees in the dirt on the side of the road with the wind blowing smoke into my face from the gulley where our old Dodge station wagon was burning like hell had opened a crack in the world right there in the back seat.

The Memory Closet

2. THROUGH ACTION

What a character does reveals the fear in his heart.

Exactly how the slave trader would kill them, Ron couldn’t imagine but he couldn’t pretend any longer that it wouldn’t happen. He was going to die.

The sun was setting. Only a little light shone from the lone window high above his head. Masapha lay on his side facing the wall—either asleep, unconscious or on his own private journey. Ron knew the room would soon be blind-man black. While he still could see, he forced his pain-wracked body to move. Leaving a bloody snail trail in his wake, he crawled/scooted across the room to where Masapha lay. When all the light was gone, Ron had to be able to reach out in the darkness and touch another human being. He couldn’t be alone; not now. After the torture he’d endured, he couldn’t be here in the blackness by himself.

Sudan

3. THROUGH DIALOGUE

“Me? Afraid?” Theo looked sideways at Gabriella and sighed. “Not ’xactly afraid. More like scared spitless. I look down into that valley out there, it’s all I can do not to spew my breakfast all over my shoes.”

“Theo, why didn’t you tell me? What else are you scared of you didn’t tell me?”

“Water.” It just popped out. He bristled instantly at the incredulity on Gabriella’s face. “Now, don’t look like you ain’t never heard nothing so pitiful in all your life. I ain’t scared of water like bathwater or rainwater, puddles, creeks, things like that. Just … deep water.”

“Heights and deep water. Did you fall off a cliff into a lake?”

“Wasn’t a lake. And didn’t nobody fall.”

The Last Safe Place

For my money, Monster’s Inc. wins the award for the cleverest use of fear—turning it wrong side out. The monsters in the closets are terrified of children.

For my money, Monster’s Inc. wins the award for the cleverest use of fear—turning it wrong side out. The monsters in the closets are terrified of children.

But we need to keep in mind that fear doesn’t ignite only a fight or flight response. The stranglehold of fear can choke the life out of a character’s every waking moment. And the sleeping moments, too.

Fear of the Boogie Man was the wallpaper of my life, the canvas on which every day was painted. Over the years, I offered the monster one peace treaty after another, a host of mutual co-existence agreements. If the Boogie Man would leave me alone, I’d leave him alone. Trouble was, the Boogie Man never lived up to his end of the bargain. He always figured out new ways to reach out of that dark closet into my wide-awake life. Anorexia. Bulimia. Cutting. Withdrawal. Depression. A period when I actually stuttered, debilitating migraine headaches, scary images on the edge of my vision, a knot in my stomach 24/7, sleep walking and night terrors.

I never questioned fear. Fear just was, a relentless predator that stalked the halls and alleyways of my mind. Eventually, I resigned myself to the reality that the Boogie Man would never stop messing with me; I’d spend the rest of my life dealing with his surprise attacks.

The Memory Closet

How have you used fear in your novels? Do leave a comment below so we can all learn from each other.

October 16, 2013

Three Ways to Use Thoughts to Create Unforgettable Characters

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #6 THOUGHTS

“Have dinner with me and we can talk about what Karen said.”

“Have dinner with me and we can talk about what Karen said.”

I was too thunderstruck to speak.

“My intentions are honorable. I’m not inviting you to go snipe hunting or cow tipping or back to my place to see my etchings.”

Don’t do it! Make up an excuse. You’re sick. You’re tired. Your left leg just fell off. You have to wash your yak. Something! Say NO.

“Yes, I’d love to. Have dinner, I mean. Can’t wait.”

The Memory Closet

In the 1997 movie Liar Liar, Jim Carey plays a character who’s been magically compelled to tell the truth, who cannot lie or even mislead—whatever he thinks comes out his mouth. Novelists have even greater magical power. We can show what a character is really thinking regardless of the words that come out his mouth.

We can take our readers on a journey inside a character’s mind.

That makes inner dialogue—thoughts—a powerful tool to create unforgettable characters. Through thoughts, we can show Loyal Reader not merely what’s happening to a character but what the character thinks about what’s happening to him. Thoughts can provide information only the character knows, can show how the character has changed over the course of the story, can lighten or darken a scene or raise the stakes in it, can provide insight into all manner of things that don’t readily translate into action.

Loyal Reader may not be able to identify with the conflict in your story, but he can identify—sympathize and empathize—with the internal turmoil your character experiences because of it.

Here are just three of the dozens of ways thoughts can create greater depth in your characters and build a bond with your reader.

1. Thoughts reveal emotions or beliefs too painful or private to share. More importantly, thoughts can explain how the character got to that place in his life.

He tried to puzzle it out. Because it mattered. A man ought to know where that crossroads was. When his life had been steaming down a channel in one direction at full throttle and then without warning stopped, turned and went down another river altogether.

Had he stopped believing even before he left for ’Nam? Wasn’t he merely going through the motions even then?

No, he’d believed, but it had been passive belief. Belief set in neutral. Just coasting. And you couldn’t take that kind of belief into battle with you. That kind of belief wouldn’t sustain you when Mattingly got his arm blown off and the squirting blood splashed in your face, and you hunkered down in the hole with him, trying to stop the bleeding. And then it did stop.

That kind of belief was nothing but the dregs left when real belief had leaked out a hole in the bucket. When Grayson really needed it, reached into the bucket for it, to scoop some up in a cup and feed it to men desperate for it—to drink some of it himself—the cup scraped on bare metal. Made a sound Grayson could hear now, deep in his soul.

When Butterflies Cry

2. The thoughts of a character grappling with a life-and-death situation show his internal struggle and reveal the cowardice or courage in the action he takes.

The engine driving Grayson’s thoughts screeched to a stop and all the thoughts behind slammed into it—bam, bam, bam. Was he nuts? Riley was facing the other way, but one wrong move, or maybe Riley just decides to walk this direction to take a leak—he’d spot Grayson and put a bullet in his brain.

So Plan B was?

There was no Plan B. Either he bailed out, left his brother to die, or he gave this a shot. Grayson’s heart began to bang, a stone pestle pounding a stone mortar, hammering his courage into dust. He turned quickly and crept off into the woods to find mud to blacken his face before he could change his mind.

When Butterflies Cry

3. A character’s thoughts reveal how the character sees the world—which may or may not be an accurate view. Thoughts can even grant the reader a window into a disturbed, delusional mind where reality is a stranger.

Yesheb felt strength pulse through his veins with every heartbeat as he reached the wooden sidewalk that ran the length of the pathetic cluster of buildings, deserted now as rain pelted them and puddled in potholes in the street. The power of his mind was so great he felt himself glide through the torrent between the raindrops and now stood perfectly dry as he reached for the knob on the door of St. Elmo’s Mercantile.

The bell on the Mercantile door jingled and Pedro looked up to see Yesheb standing in the doorway drenched to the skin, dripping water in a pool around him as if he had made no effort at all to stay dry.

The Last Safe Place

Of course, thoughts must be as much in your character’s voice as what he or she says aloud. Though you DON’T use quotation marks, there are half a dozen different ways to let the reader know that what follows are the character’s thoughts: dialogue tags, italics, italics with dialogue tags, italics without dialogue tags. The simplest is simply to say so.

So there was a tumor growing up there in his brain that could kill him. Theo thought for a moment. He’d call the tumor … Cornelius. Always did hate that name. A thing as important in your life as what could kill you had ought to have a name but no sense wasting a good one on it.

The Last Safe Place

Whatever method you choose, you need to keep it consistent through-out the book. I’ve used different methods in different books, but my preference is italics.

The smell of the Vicks and Mentholatum Bobo slathered on herself made my eyes water. I hoped Dusty was sufficiently upwind.

“She thinks you’re the Border Patrol and you’ve come to take Julia back to Mexico,” I told him.

“Julia ain’t done nothing wrong here,” Bobo whined, playing the poor-little-old-lady card. “She ain’t broke no law ’cept being a greaser and a wet-back.”

I cringed at the racial slurs.

Dusty, I’d like you to meet my grandmother. She’s a bigot, she stinks and she’s named after a clown.

I stepped in before Bobo could jam her foot further down her throat.

“Sheriff,” I said, “I think you need to come back next week.”

The Memory Closet

And I hope you’ll come back next week, too, when we’ll talk more about unforgettable characters. Leave a comment below and tell me what you think … about thoughts—a character’s, that is.

Write on!

9e

October 7, 2013

Three Ways to Use Dialogue to NAIL Great Characters

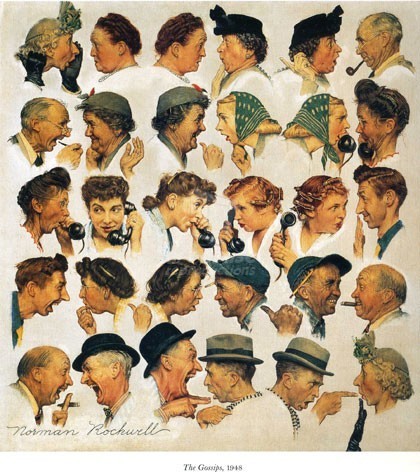

Norman Rockwell understood dialogue!

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #5 DIALOGUE

“One psycho with a nuke—that’s all it’s gonna take,” Steve said.

“Armageddon, huh?” Andrew rolled his eyes. “You’re an idiot.”

“Hey, no reason to get nasty,” said Jonathan. “You need to apologize.”

“When pigs fly.”

“Go on now, tell him you’re sorry.”

“Bomb-Making for Dummies—that’s a website!”

“Who appointed you Chicken Little?”

“The sky is falling. And you’re the idiot.”

“Come on, guys, play nice.”

By now, most of you are wondering how this inane conversation got the address of my blog.

But some of you are also saying, “I saw what you did there.”

What I did was drop the attributions. If you didn’t notice, it’s because the dialogue itself made it clear who was speaking. Good dialogue should do that. It should require only the bare minimum he said/she said because the character of the speaker is inherent in every line.

The first thing we need to understand about dialogue is what it isn’t. It isn’t a mirror image of real speech. It’s not dialogue’s job to mimic actual conversation. Dialogue is a literary construct that is “similar to” but not “the same as” real speech.

“Theo, this is … dangerous.”

“Ya think?”

“You won’t like where we’re going.”

“I don’t like where we been! You ever notice how many fat women they is in South Carolina?”

“Theo, I’m serious.”

“And you think I’m not? That woman over there, she got so much flab on her arms she look like a flying squirrel.”

Ty made an unsuccessful attempt to stifle a giggle.

“And them spandex pants. They’s stretched so tight over them thunder thighs, she try to run, her legs gone rub together and start a fire.”

From: The Last Safe Place

Snappy dialogue, but is that the way the people in your life talk? (If it is, invite me to your next party.) Where’s the stammering, the um, the uh, the you-know, the repetition—and totally, like where are all the interruptions and stuff? Can you make up lines like Theo’s on the fly, instead of when you’re lying awake at three in the morning and you nudge Mildred, “I shoulda told that guy…”

Perhaps it’s helpful to think of dialogue as freeze-dried speech—speech with the dull parts taken out. What we say and how we say it reveals volumes about who we are, so if dialogue is concentrated speech, it should give us a concentrated dose of characterization in each sentence. Dialogue should show Loyal Reader in only a line or two what it would take pages of exposition to reveal.

And so I give you the most famous line of dialogue in American film history, ta-da:

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Those eight words from the 1939 movie adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind tell you in one sentence where Rhett Butler’s journey through the story has finally taken him, from adoring Scarlett to not caring what happens to her.

This snippet of dialogue was voted the number one movie line of all time by the American Film Institute. Likely not for the right reason, though. It should be famous as a stellar example of the single most important role of dialogue in fiction—the sacred function of “show don’t tell.” Every writer should have those three words tattooed in 18 point Helvetica bold on a prominent body part, one he can see when he types. Don’t tell me Mary Anne was angry, show me the end-over-end flight of the Tiffany lamp as she hurls it across the room.

There are, of course, dozens of ways writers can employ the power of dialogue to create unforgettable characters. Absent the space to list and talk about them all, I’m forced to settle for my three personal favorites:

One, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell your character’s mood, state of mind, emotion. Agitated characters stutter, fumble for words, speak in short, staccato sentences, interrupt. Shy characters—and boys in the throes of puberty—speak in one-word, monosyllabic grunts. Scarlett’s frantic, “What shall I do, where shall I go?” is a portrait of uncertainty and fear. Rhett’s responding slam dunk, dialogue-ly speaking, reveals an emotionally wrung-out man unable to feel much of anything anymore.

One, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell your character’s mood, state of mind, emotion. Agitated characters stutter, fumble for words, speak in short, staccato sentences, interrupt. Shy characters—and boys in the throes of puberty—speak in one-word, monosyllabic grunts. Scarlett’s frantic, “What shall I do, where shall I go?” is a portrait of uncertainty and fear. Rhett’s responding slam dunk, dialogue-ly speaking, reveals an emotionally wrung-out man unable to feel much of anything anymore.

Two, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell Loyal reader all manner of basic information—that Jerry drinks too much and Stella is afraid of men. But what particularly delights me is the way you can craft a character’s choice of words, the speech patterns themselves to paint vivid pictures.

“You do have a plan, don’t you?” Ron asked.

“A plan, yes,” Masapha replied. “We need all of the money we can lay on our hands.”

“It’s lay our hands on.”

“First, we buy a jeep.”

“Do you know how much a jeep costs?”

“No jeep, no pictures. Can we chase the slave traders running on our feet?”

Ron gestured out the window at the remote little river village. “And where, pray tell, is the nearest dealership?”

Masapha sighed. “There is no dealer ship to the Arab oil fields,” he said. “No river launch or steamer either. It is no water there; it is desert. We need a jeep!” He paused. “It will not be easy to talk me from this.”

Ron didn’t try.

From Sudan

And three, you can craft dialogue to reveal the nuances of your characters’ relationships and show (don’t tell) how they subtly shift and change as they journey together through the pages.

“Bobo, can I ask you a question?”

“That is a question.”

It took me a moment to get it, then I plunged ahead. “Do you know why I’m here?”

“Ever body’s got to be somewhere.”

I put my spoon down carefully and spoke in a quiet voice. “Look, can we just talk? I’m tired of being the straight man in your vaudeville act—The Amazing Bobo and Her Trained Chimp.”

Bobo burst into uproarious laughter. Then I got tickled, too, and we laughed together. When we finally wound down, she was beaming at me.

“Well, you got some powder in your musket after all! I was beginning to wonder.” She reached over and patted my hand. “You ask anything you want and I’ll answer best as I can. But they’s days I don’t know my own self what’s real and what ain’t. Anymore, I can’t swear to nothing.”

From The Memory Closet:

I’ve had those days myself, Bobo, but I’m relatively certain we will be back here next week to talk about unforgettable characters. And I’m completely certain that every one of my writer friends has written dialogue that illustrates the above principles or other equally important ones. Please do share some of it in the comments below so we can all learn from your expertise.

Write on!

9e

September 28, 2013

Three powerful ways to use action to create memorable characters

What did it say about the little green eyeball monster that he rebuilt a door for his friend?

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #4 ACTION

True story. No, I’m serious, this really happened.

Four teenage boys go to a crowded movie. The house lights dim. The movie begins and Roger, the dude farthest from the aisle, feels a call of nature. He stands and edges down the row past his friends’ knees, to the accompaniment of goosing, butt slapping, wedgies, pinching and other indignities too numerous to mention.

When he returns, he figures to spare himself the abuse by facing his friends as he makes his way back to his seat. Halfway there, one of them whispers, “Hey, Rog, your fly’s unzipped.” Roger looks down—yup, wide open. The other boys begin to razz him, but Roger turns his back to them and hurriedly zips up. Or tries to. The zipper moves only a little way, then gets stuck. He yanks harder. Nothing.

The row in front of the boys is occupied by a big, husky guy with his arm around his girlfriend. She is seated directly in front of where Roger is standing. The girlfriend has long hair. Long, thick hair. Long, thick, big hair.

When Roger yanks on his zipper, the blonde girlfriend’s head snaps back. He pulls again; her head jerks again. He wrenches as hard as he can; she begins to squeal. Now, no one in the theatre is watching the movie. Soon, the house lights come on and the usher appears. Since Roger’s crotch is now welded to the head of a girl he has never met, the two are escorted out with the girl bent at the waist shuffling backward in front of Roger as her boyfriend threatens all manner of future mayhem.

While all this was going on, what did the other three boys do? For our purposes, it doesn’t really matter what they actually did do. If you were writing this as a fictional scene, what would you have them do? Would it matter, would Loyal Reader make any judgments about the characters of those boys based on what they did as their friend was hauled away, attached at the groin to a stranger?

Absolutely.

Who you are determines what you do and when you turn that wrong side out, it becomes what you do ILLUSTRATES who you are. Screenwriters apply that principle in Save The Cat moments. David Hewson, who wrote a book by the same name, defined the term in the forward.

Who you are determines what you do and when you turn that wrong side out, it becomes what you do ILLUSTRATES who you are. Screenwriters apply that principle in Save The Cat moments. David Hewson, who wrote a book by the same name, defined the term in the forward.

“Because liking the person we go on a journey with is the single most important element in drawing us into the story, screenwriters developed what I call the Save the Cat scene. It’s the scene where we meet the hero and the hero does something—like saving a cat—that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him.”

Hewson used as an example the classic thriller Sea of Love. In the opening scene, Al Pacino is a cop running a sting operation to capture parole violators with the promise of a locker-room visit with New York Yankee players. But when he sees one of the violators enter with an excited little boy wearing a Yankees cap, Pacino flashes his badge at the man, who nods in understanding and disappears.

Hewson used as an example the classic thriller Sea of Love. In the opening scene, Al Pacino is a cop running a sting operation to capture parole violators with the promise of a locker-room visit with New York Yankee players. But when he sees one of the violators enter with an excited little boy wearing a Yankees cap, Pacino flashes his badge at the man, who nods in understanding and disappears.

“Well, I don’t know about you,” Hewson wrote, “but I like Al. I’ll go anywhere he takes me now and I’ll be rooting for him to win. All based on a two-second interaction between Al and a Dad with his baseball-fan kid.”

The principle also applies in the reverse. The first paragraph of my novel Home Grown is a Drown the Cat scene that features one of the main characters and his Rottweiler guarding a marijuana patch.

Bubba Jamison reached down and scratched Daisy under the chin, just above the scar where he’d slit her throat when she was a puppy. Most dogs didn’t survive, maybe one out of a whole litter. But those that did became the perfect weapon—with slit larynxes, they couldn’t bark. Bubba didn’t want anybody to hear his guard dogs coming.

For my money, action is the most powerful tool writers have to create unforgettable characters. Consider how a single act In J.R.R. Tolkein’s Fellowship of the Rong illuminated the character of a little guy with furry feet.

Frodo Baggins stepped forward and spoke in a voice loud enough to be heard above the shouting. “I will take the ring,” he said, “… though I do not know the way.”

Frodo Baggins stepped forward and spoke in a voice loud enough to be heard above the shouting. “I will take the ring,” he said, “… though I do not know the way.”

Now that was a conversation stopper.

Or how about when Mike Wazowski in Monsters, Inc. put together all the pieces of Boo’s door so Sully could see the little girl again?

You can use every action, even small, inconsequential ones, to define and shape your character. Does your hero methodically put on a sock and a shoe and a sock and a shoe instead of sock, sock, shoe, shoe? Does that mean he’s quirky or full bore OCD? Loyal Reader absorbs those moments almost unconsciously, shifts and adjusts his perceptions of a character because of them. Our job as writers is to orchestrate specific actions so they flow naturally and organically from the story, giving Loyal Reader a constant stream of subtle clues that define and shape our character in his mind.

How do you do that? Here are three suggestions:

1. Know your character. Crawl into her skin and walk around and you’ll discover things. This woman would never cheat on her husband. This dude has a chip on his shoulder the size of Cleveland. This little boy would do anything just to be noticed.

2. Develop a plan for revealing the significant actions as you progress through the novel. Orchestrate circumstances that call for the kind of action from your character that will reveal his character.

3. And with each succeeding circumstance, raise the stakes. Again from The Lord of The Rings: In the safety of the Shire, Sam willingly accompanies his master to “see the elves.”

3. And with each succeeding circumstance, raise the stakes. Again from The Lord of The Rings: In the safety of the Shire, Sam willingly accompanies his master to “see the elves.”

Raise the stakes. What Will Sam do when the trip becomes a dangerous quest?

Raise the stakes: Is Sam willing to fight a giant spider to protect Frodo?

Raise the stakes. Will he remain steadfast to Frodo even if it means dying at his side? All of those actions defined Sam Gamgee as no dialogue or description ever could have done.

All of those actions defined Sam Gamgee as no dialogue or description ever could have done.

So now we have come full circle, back to Roger of the stuck zipper. How did the actions of his three friends illuminate their characters? Well, the first friend bailed as soon as the lights came up. Friend #2 almost asphyxiated from laughter, as did most of the other people in the theatre. But Friend #3 went along with Roger, appeased The Boyfriend and got Roger out of the building with all his body parts in tact. A young man of sterling character, that. I should know. I married him.

Write on!

9e

September 17, 2013

The Three Best Ways To Physically Describe Your Characters

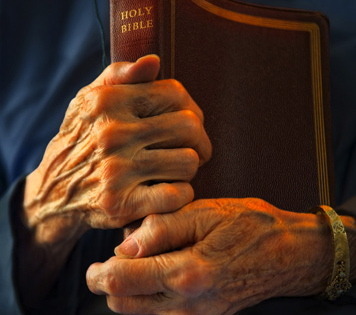

“She had hands like a man, big and strong, and they were only still when she held her Bible.”

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS

#3 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

“You had a visitor while you were out.”

“Who?

“Didn’t give her name.”

“What’d she look like?”

“She was about as tall as a five-foot, four-inch mop handle, with a windblown look—that look you get from standing outside in the wind. Her voice was the high-pitched sound a forklift makes when it backs up, but her laugh was throaty, like a cat hocking up a hairball. Her eyes were either the blue of that marker on a pregnancy test that says you’re not knocked up, or the green of a piece of okra floating in hollandaise sauce. She had serious hygiene problems, though, smelled like a rainy day at the petting zoo and her rotted teeth looked like she had a mouth full of crumbled Oreo cookies.”

So my question to you, my writer friends, is this: if we can all agree that nobody actually describes people this way in real life, why do we think it’s acceptable to do it in fiction? Granted, these particular analogies are as lame as a horse hit by a garbage truck. (Sorry, once you get going, it’s hard to stop.) But that may be obvious only because they’re all bunched together in one place. I suspect we’ve all read, and maybe even written, some equally bad descriptions that we sprinkled here and there in our prose.

The third in the list of Ten Ways to Create Unforgettable Characters is physical description. Of real people. I understand there are conventions in certain genres, that just about every romance hero has a chiseled grin and a grizzled chin, washboard abs and a piano-key smile.

The third in the list of Ten Ways to Create Unforgettable Characters is physical description. Of real people. I understand there are conventions in certain genres, that just about every romance hero has a chiseled grin and a grizzled chin, washboard abs and a piano-key smile.

The flip side of washboard abs.

But those of us in other genres have the task of describing the guy in line in front of the romance hero at the beer booth, the guy whose grin poking out of a mangy beard is missing key teeth and whose washboard abs have migrated south to become a washtub belly.

The reality all writers face is that we’re stuck with the basics in terms of physical descriptions—tall/short, fat/skinny, old/young. And body parts–eyes, nose, mouth, ears. Here are three simple suggestions to guide us:

Eyes.

1. No summary words. Ugly, beautiful, athletic. Don’t tell me the bad guy is ugly, tell me his face is so concave the tip of his nose and his eyebrows would hit the wall at the same time if he tripped and he has a mole the size of a Milk Dud right above his harelip.

2. If you use a metaphor, keep it simple and striking. And no more than one metaphor per character per scene.

Nose.

3. Don’t limit yourself to sight; give the reader kinesthetic details, too—how a character stands or moves. Will describes Granny in Black Sunshine:

She had hands like a man, big and strong, and they were only still when she held her Bible. Otherwise, they were in motion. They peeled potatoes, mended socks, scrubbed floors, planted flowers in the front yard and vegetables out back. But they’d always looked too large to fit on her mandolin, too awkward to evoke the haunting melodies of mountain music on summer evenings when Ricky Dan played his guitar and Bowman made a fiddle sing.

Mouth.

There are two decisions every writers has to make about character description—when and how much. Do you describe your character as soon as she is introduced, paint a detailed portrait so Loyal Reader can instantly picture her in his mind?

Or do you dribble description as you go along, noting only the basics at first—a man in his mid-thirties—and adding the rest as the story progresses?

Ears

I tend to be a Plan A writer. Marian describes her daughter-in-law, Piper, on page 3 of When Butterflies Cry.

Piper’s face, with them high cheekbones she got from her Cherokee grandmother, was likely pale as a clean sheet right now. No smile on them plump lips men went all stupid over. Her black hair hung loose in curls on her shoulders and Marian was sure there was a haunted look in her eyes ’cause you could read that girl’s soul in them big brown eyes. And when her temper flared—and Piper had a fearsome temper—she could pull them black eyebrows together to give you a look as would cause internal bleeding.

How much do you tell the reader? A portrait or a sketch? Is it your job to describe a character in such a way that the reader sees in his mind the same image you see in yours? Or is it your job to provide a few broad strokes so Loyal Reader can conjure up with his own image?

The choice is yours. But you do need to make it and stick to it.

One final description technique is to give a main character some characteristic, not strictly physical, that defines them, then use it in different circumstances throughout the story. Bobo, from The Memory Closet, had an unnerving habit of suddenly removing her dentures.

This woman’s toothlessness didn’t distort her face as profoundly as Bobo’s did.

That first time, when she reached into her mouth and pulled out her bottom plate, then the top, and placed them on the red gingham tablecloth between us, I tried not to look at them. But looking at her face was equally disturbing. Everything below her eye sockets had imploded, sunk into a cave of wrinkled skin below her nose. And when the corners of her cavernous mouth turned suddenly upward, I wondered frantically, “Is she smiling?” I smiled back, just in case.

Maybe you’re smiling at me right now, too. Maybe not. But I’m smiling back just in case. And if you have character description techniques that might be useful to other writers, share them in the comments below and we’ll all smile back at you.

Write on!

9e

THE THREE BEST WAYS TO PHYSICALLY DESCRIBE YOUR CHARACTERS

“She had hands like a man, big and strong, and they were only still when she read her Bible.”

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS

#3 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

“You had a visitor while you were out.”

“Who?

“Didn’t give her name.”

“What’d she look like?”

“She was about as tall as a five-foot, four-inch mop handle, with a windblown look—that look you get from standing outside in the wind. Her voice was the high-pitched sound a forklift makes when it backs up, but her laugh was throaty, like a cat hocking up a hairball. Her eyes were either the blue of that marker on a pregnancy test that says you’re not knocked up, or the green of a piece of okra floating in hollandaise sauce. She had serious hygiene problems, though, smelled like a rainy day at the petting zoo and her rotted teeth looked like she had a mouth full of crumbled Oreo cookies.”

So my question to you, my writer friends, is this: if we can all agree that nobody actually describes people this way in real life, why do we think it’s acceptable to do it in fiction? Granted, these particular analogies are as lame as a horse hit by a garbage truck. (Sorry, once you get going, it’s hard to stop.) But that may be obvious only because they’re all bunched together in one place. I suspect we’ve all read, and maybe even written, some equally bad descriptions that we sprinkled here and there in our prose.

The third in the list of Ten Ways to Create Unforgettable Characters is physical description. Of real people. I understand there are conventions in certain genres, that just about every romance hero has a chiseled grin and a grizzled chin, washboard abs and a piano-key smile.

The third in the list of Ten Ways to Create Unforgettable Characters is physical description. Of real people. I understand there are conventions in certain genres, that just about every romance hero has a chiseled grin and a grizzled chin, washboard abs and a piano-key smile.

The flip side of washboard abs.

But those of us in other genres have the task of describing the guy in line in front of the romance hero at the beer booth, the guy whose grin poking out of a mangy beard is missing key teeth and whose washboard abs have migrated south to become a washtub belly.

The reality all writers face is that we’re stuck with the basics in terms of physical descriptions—tall/short, fat/skinny, old/young. And body parts–eyes, nose, mouth, ears. Here are three simple suggestions to guide us:

Eyes.

1. No summary words. Ugly, beautiful, athletic. Don’t tell me the bad guy is ugly, tell me his face is so concave the tip of his nose and his eyebrows would hit the wall at the same time if he tripped and he has a mole the size of a Milk Dud right above his harelip.

2. If you use a metaphor, keep it simple and striking. And no more than one metaphor per character per scene.

Nose.

3. Don’t limit yourself to sight; give the reader kinesthetic details, too—how a character stands or moves. Will describes Granny in Black Sunshine:

She had hands like a man, big and strong, and they were only still when she read her Bible. Otherwise, they were in motion. They peeled potatoes, mended socks, scrubbed floors, planted flowers in the front yard and vegetables out back. But they’d always looked too large to fit on her mandolin, too awkward to evoke the haunting melodies of mountain music on summer evenings when Ricky Dan played his guitar and Bowman made a fiddle sing.

Mouth.

There are two decisions every writers has to make about character description—when and how much. Do you describe your character as soon as she is introduced, paint a detailed portrait so Loyal Reader can instantly picture her in his mind?

Or do you dribble description as you go along, noting only the basics at first—a man in his mid-thirties—and adding the rest as the story progresses?

Ears

I tend to be a Plan A writer. Marian describes her daughter-in-law, Piper, on page 3 of When Butterflies Cry.

Piper’s face, with them high cheekbones she got from her Cherokee grandmother, was likely pale as a clean sheet right now. No smile on them plump lips men went all stupid over. Her black hair hung loose in curls on her shoulders and Marian was sure there was a haunted look in her eyes ’cause you could read that girl’s soul in them big brown eyes. And when her temper flared—and Piper had a fearsome temper—she could pull them black eyebrows together to give you a look as would cause internal bleeding.

How much do you tell the reader? A portrait or a sketch? Is it your job to describe a character in such a way that the reader sees in his mind the same image you see in yours? Or is it your job to provide a few broad strokes so Loyal Reader can conjure up with his own image?

The choice is yours. But you do need to make it and stick to it.

One final description technique is to give a main character some characteristic, not strictly physical, that defines them, then use it in different circumstances throughout the story. Bobo, from The Memory Closet, had an unnerving habit of suddenly removing her dentures.

This woman’s toothlessness didn’t distort her face as profoundly as Bobo’s did.

That first time, when she reached into her mouth and pulled out her bottom plate, then the top, and placed them on the red gingham tablecloth between us, I tried not to look at them. But looking at her face was equally disturbing. Everything below her eye sockets had imploded, sunk into a cave of wrinkled skin below her nose. And when the corners of her cavernous mouth turned suddenly upward, I wondered frantically, “Is she smiling?” I smiled back, just in case.

Maybe you’re smiling at me right now, too. Maybe not. But I’m smiling back just in case. And if you have character description techniques that might be useful to other writers, share them in the comments below and we’ll all smile back at you.

Write on!

9e

September 9, 2013

Don’t Make These Four Mistakes When You Name Your Characters

Can you imagine giving this cutie pie an ugly name? Neither can I.

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS

#2 NAME

It’s clear that from the outset my parents never intended for me to amount to anything. How could I? With a name like “Ninie?” Please.

Fame and fortune do not come to people named Ninie Bovell (My maiden name.) Gabriella Bovary? You could work with that. Even something as pedestrian as Madeline Bovell or Rebecca Bovell or (though you’d lose points here for lack of originality) Elizabeth Bovell. But Ninie? I never had a chance.

If I sound a mite hostile, bear in mind that in one decisive stroke my parents sentenced their precious newborn daughter to a lifetime of explanations that began my first day at Muleshoe Elementary School. (Yeah, Muleshoe. The hits just keep on coming.) After a painful week, I had a rap down that I still use today:

“No, it’s not Ninnie like skinny and penny. It’s Ninie—rhymes with tiny and shiny. 9e…get it? And no, it doesn’t mean anything, it isn’t short for anything, long for anything, or a substitute for anything. It just is. (Pause here for the inevitable ‘Why?’) You got me, pal, I couldn’t tell you.”

So my question to you, my writer friends, is this: have you done something similar to the characters in your novel? Have you given serious thought to the names of the people who will live your tale—serious thought—or did you just glance up one day at a television commercial and now the dashing hero who rescues the beautiful countess in your French Revolution romance novel is Aflak Geico.

“A rose by any name would smell as sweet” does NOT apply to naming fictional characters. Here are four mistakes you can avoid when you name yours.

“A rose by any name would smell as sweet” does NOT apply to naming fictional characters. Here are four mistakes you can avoid when you name yours.

1. Names have to line up with the time, the culture and the setting of your novel. But remember to take it back a generation. If your novel is set in Atlanta during the Civil War, the characters were born in the 1840’s. Probably weren’t a lot of Georgia mamas naming their baby girls Lindsay or Shamika or their boys Shane or Tyrone in 1840. Check the origins of the names you choose. Sure, it’s a safe bet you can name an Irishman Patrick O’Malley. But if you pick Nguyen for an Asian character—is that a Vietnamese name? Cambodian, Chinese, Laotian?

2. Say the name out loud. Is it pronounceable? Loyal Reader will skip over it if he can’t say it in his head when he reads. (I refer you to War and Peace.) Check how the names of character combinations fit, so you don’t wind up with best friends Bert and Ernie or Ben and Jerry. Is the name an inadvertent tongue twister—Seth Sainsbury, Elizabeth Thornton, Keith Police. Don’t repeat first letters—Jeff, Jake, Jenny, Jessica—or ending sounds, Billy, Johnny, Becky, Shirley. Vary the number of syllables between first and last names and among characters. Change Caleb Wilson, Richard Jacobs and Lisa Martin to Caleb Wilkerson, Rick Jacobs and Lisa Martinelli.

3. Truth is, no matter what name you pick, you can’t stave off every adverse reaction. Though Isaiah Dunstable may be a dignified federal judge in your novel, he may also have been the kid in Loyal Reader’s third grade class who threw up his hot dog every Friday. But unless you’re trying to achieve a desired effect—humor or satire—you’re asking for trouble if you start pilfering names from the realm of the iconic. Yes, you absolutely can name your heroine Scarlett O’Hara. Just understand whose face will come into Loyal Reader’s mind every time the character is mentioned. No amount of elegant prose on your part will be powerful enough to change that. Name your hero Ricky Ricardo if you choose, and “you got some s’plainin’ to do, Lucy,” will echo behind every line of dialogue. And if you decide to name the bad guy in your Western adventure novel John Wayne—good luck with that.

3. Truth is, no matter what name you pick, you can’t stave off every adverse reaction. Though Isaiah Dunstable may be a dignified federal judge in your novel, he may also have been the kid in Loyal Reader’s third grade class who threw up his hot dog every Friday. But unless you’re trying to achieve a desired effect—humor or satire—you’re asking for trouble if you start pilfering names from the realm of the iconic. Yes, you absolutely can name your heroine Scarlett O’Hara. Just understand whose face will come into Loyal Reader’s mind every time the character is mentioned. No amount of elegant prose on your part will be powerful enough to change that. Name your hero Ricky Ricardo if you choose, and “you got some s’plainin’ to do, Lucy,” will echo behind every line of dialogue. And if you decide to name the bad guy in your Western adventure novel John Wayne—good luck with that.

4. My favorite gem of character-naming advice was gleaned from experience: don’t give any of them names that end in “s.” Or if you do, don’t let them own anything because making s-characters possessive is a bear. It looks strange on the page and saying it aloud gives you a lisp. The only thing worse than ending a character’s name with s is ending a character’s name with two s’s (s-es?). In Five Days in May, my main character was Princess. And when I wrote about Princess’s secrets, I thought I heard a Raven knocking, knocking at my chamber door—only this and nothing more.

The bottom line in character names is simple—be intentional. Don’t pick the first name that happens to pop into your mind. This character will carry whatever name you select through the life of your story and into the hearts and minds of your readers. If you discover a name doesn’t work or is awkward in combination with another character’s name, swap it for something more suitable. Why do you think God created global change?

So where do you go to find character names? Start with the phone book. From there move on to baby-naming books. Check the internet for most popular names 20 years prior to the timeframe of your novel. Look in the Bible.

So where do you go to find character names? Start with the phone book. From there move on to baby-naming books. Check the internet for most popular names 20 years prior to the timeframe of your novel. Look in the Bible.

And if all else fails, put some syllables together, wallow them around in your mouth and see how they sound. You can, after all, simply make up a name. Look how well it worked out for my parents.