Three Basics Will Revive Dead Dialogue

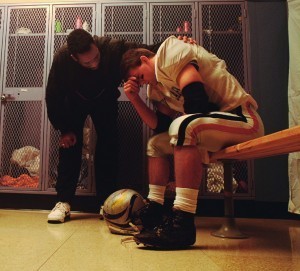

What’s that coach saying? In a gripping scene like this, you can bet it’s great dialogue.

10 ESSENTIALS OF A DYNAMITE STORY #6 GREAT DIALOGUE

“You ate my cookie.”

“No, I didn’t!”

“Yes, you did!

“No, I didn’t.”

“You did, too.”

“I did not.”

“Did, too.”

“Did not.”

“Did, too.”

“Not.”

“Too.”

“Not!”

“Too!”

“Not, not, not, not, not, not!”

“I’m telling!”

This exchange illustrates the first requirement of great dialogue—it must sound like people really talk. Unfortunately, it also violates the Alfred Hitchcock principle. The words of the rotund king of cinematic terror are never far from me—they’re written on a plaque above my desk: “A great story is life with the dull parts taken out.”

Mangle his maxim slightly and it can apply to talking on paper: “Great dialogue is speech with the dull parts taken out.”

Dialogue must sound like—defined as comparable to—the way people really talk. Though it will give your story a sense of verisimilitude to construct dialogue exactly like real conversations, the result will have Loyal Reader nodding and drooling in under three pages.

Perhaps this happens to you, too. There comes a point when I’m writing a first draft that the characters start talking to each other. Before that point, they are my creations, mere puppets on a string. But after that point, they take on lives of their own. They know each other and I find they have lots of things they want to talk about. It is then that I say I “transcribe” dialogue rather than write it, typing as fast as I can to get it all on the page. That’s a truly glorious feeling for a writer. However, when I go back through the manuscript on my second draft, I take an editing machete to that dialogue and red ink flows like I’ve sliced an artery. To write good dialogue, you have to freeze dry it. Dehydrate it. Take out all the puffy moisture until the only thing that’s left is the essence, the absolute bare minimum. Then—and this is the best part–you add some fairy dust and make that bare minimum sparkle.

“You ate my cookie.”

“See any crumbs on my shirt? Smell chocolate on my breath?”

“I’m telling!”

“You do that. She’s putting the fuse in a car bomb. She’ll appreciate the interruption.”

This reconstructed exchange serves the dual purpose of illustrating the second requirement of great dialogue, too—it must move the plot forward. What your characters say must matter to the action. It needs to advance the story, tell us something we didn’t know about what’s happening. There’s no place for “chatting” in a novel. Every word of dialogue must serve a function or you must mercilessly cut it out.

Of course, it’s acceptable for your dialogue to look like it’s chatting, when in fact it is serving the third function of great dialogue—revealing something about the characters involved.

“You ate my cookie.”

“No, I didn’t. I’d never do a thing like that.”

“I’m telling.”

“No! Oh, please, don’t. Ok, I took it–but I’m sorry. I’ll get you another cookie. I’ll bake you a dozen more cookies. A barrel full of cookies. Just don’t tell! You know what Cookie Monster’s like when he gets angry.”

Great dialogue sounds like people talk, advances the plot and reveals character. And best of all, you already know how to use it. You’ve been practicing dialogue your whole life. So listen to yourself. Listen to the people around you. What is it about one person’s speech that’s distinctive? And particularly if you’re writing dialect—what is it about the sentence construction that defines the region? Read great screenplays—they’re almost nothing but dialogue. And read Hemmingway; he was a master.

There are boatloads of never’s and always’s regarding the use of dialogue and I told myself I wasn’t going to go there. But allow me just this one, please. This word usage is as irritating to me as Justin Bieber. (No, nothing is as irritating as Justin Bieber. Either his hair is on backwards or his head is.) NEVER use an adverb to modify the word “said.” Put another way, if you need an adverb to make the dialogue understandable to Loyal Reader, what you need more is to go back and rewrite it. Adverbs modifying “said” are, at the very least, redundant and at worst totally ludicrous.

“Do that one more time and I’ll break your arm off and beat you to death with the bloody stump,” his mother said menacingly.

“Drop that AK47 right now,” the Navy Seal said forcefully.

“You’re in a good mood—must have run over a nun on the way here,” his persnickety aunt said sarcastically.

“I feel so bad for Waldo. I can’t believe his parents named him ‘Where’s,’” his blonde date said dumbly.

“That thing on your face isn’t a mole—it’s a Milk Dud,” the bully said mockingly.

‘Nuff said. Next week, we will talk about theme.

Write on!

9e