V. Moody's Blog, page 92

March 18, 2013

Tell The Reader Why

While showing, rather than telling, is an excellent technique when it

comes to moments of action, drama and emotion, there are times when telling is a

far more useful and efficient approach to take.

One of those times is when dealing with motivation. Why a character

does what he does is going to be a key part of any scene.

It’s important that you make the reader aware of the character’s

reasons as quickly as possible. As a writer, you may think you can withhold that

information and that the reader will assume you will fill them in later and not

be too bothered. You would be wrong.

It’s incredibly annoying not knowing the reasons for a character’s

actions, and it directly affects how you view what they’re doing. It's much more difficult to engage or empathise with a character when you don’t know their reasons.

But it’s hard to show motivation, especially if there are subtle or

complex reasons behind a character’s behaviour. And in most cases it’s just a

matter of practical necessity.

If a character is unscrewing an air vent in order to escape from a

locked room, or if he’s doing it to hide a bag full of money in there, a

longwinded demonstration of his reasons is less important than just letting the

reader know which it is.

Waiting until he’s finished taking down the vent cover before telling

us why he’s doing it may not seem like a big deal, but not knowing what’s going

on isn’t a desirable state to be in. And holding back and then revealing fairly

mundane information isn’t very impressive.

Far more effective to just tell the reader he’s hiding the money from

his wife who’ll only ask where the money came from, and since he promised her

he wouldn’t rob any more banks, she wouldn’t like the answer. And then move on.

Trying to ‘show’ that motivation wouldn’t be difficult and totally

unnecessary. And not telling the reader until later would gain nothing and just

make the story seem vague.

It’s obvious why aspiring writers often take the vague approach. The idea

of not knowing what’s going on and then finding out seems like a narrative

structure that will keep readers engaged, but it’s an artificial way to do it.

If a guy is searching under his bed for something there’s no point in making a

mystery out of it if all he’s doing is looking for his shoes.

There’s also the issue of POV. If the character knows why they’re

doing what they’re doing, so should the reader (assuming we’re in that

character’s POV). Not revealing the reasons just feels unnecessarily coy.

Of course, if the POV character doesn’t know why they’re doing what

they’re doing then neither will the reader, but then someone should ask them

(or they should ask themselves) why they’re acting in this way. You don’t have

to provide an answer, but showing the reader you are aware of the lack of

motivation will buy you time. Not for very long though.

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on March 18, 2013 11:11

March 14, 2013

The Little Reasons A Story Works

It’s not enough to have something dramatic happen in a story. The

reason why it happens is also important.

In terms of impact on a reader, there’s a big difference between a

character getting upset about losing their house to the bank and getting upset

because their favourite tv show got cancelled.

What happens keeps the reader interested in the short term. Why it

happens is what keeps them interested over the course of an entire novel.

For the big things, the major plot points, the premise, the reasons

why it’s happening will be something the writer is probably already aware of

and working on to make sure its importance is clear.

The guy doesn’t want the girl to leave because he loves her, the

secret agent wants to find the bomb before it kills everyone, the cop wants to

catch the serial killer because yada yada.

Obviously, being aware you need a reason is only part of it. You still

have to come up with decent ideas and execute them well, but as long as you

know where to make those reasons clear and interesting, you’ll have as good a

chance of making it work as is possible.

However, the big moments aren’t the only moments in a story.

Characters have to go about doing stuff, getting to places, interacting with

each other. Those scenes also require characters to have reasons for doing what

they’re doing.

Since those moments aren’t of such great consequence, it can be easy

to let them slide. Make them as short and quick as possible and get them out of

the way. You need a guy to go to the store because once he gets there he finds

the place overrun with Martians and the story gets going. So he tells his wife

he’s going to get some milk and off he goes.

And that’s perfectly plausible. It won’t have readers throwing the

book down in disgust, they’ll keep reading, probably, as long as things don’t

get too pedestrian. But not turning them off isn’t really where you want to aim

for. The question is, will it keep them engrossed and turning the pages?

Because flat, generic, emotionally bland scenes don’t tend to hold the

attention. And just because we haven’t got to the bit with the aliens yet,

doesn’t mean it’s okay to coast.

If, for example, the wife wants him to get five things from the store

and tells him to write them down so he won’t forget, and he gets pissed off

because she has no faith in him and he refuses to write a list but she texts

him the list, so he takes a photo of a dog taking a dump in the street and

sends it to her... well, maybe you don’t have to go quite that far. My point is

you can create tension and emotion and reveal character and have a dynamic

already in place using the smallest of scenes.

That way, when he does get to the Martians in the 7-11, he’s not going

to arrive like he’s idling in neutral, and the reader isn’t still waiting for

the story to start.

In real life, people do things for the same reasons as everyone else.

If I say I’m eating a sandwich you won’t require an explanation, you’ll just

assume I’m hungry and eating is what you do when you’re hungry. As a writer,

though, there is room in the seemingly ordinary to stimulate the reader’s interest.

If a man says he’s going to the bank, there’s no reason why the bank

scene can’t be interesting and engaging.

If man says he’s going to the tanning salon, there’s no reason why

that won’t be an entertaining scene.

But if a man says he’s going to the bank, but he drives past the bank

and pulls up outside a tanning salon, you’ve already got the reader’s interest

before the scene has started.

You can get away with giving characters the usual, familiar reasons for doing things, but the potential for the unexpected or unfamiliar to engage a reader often goes unexploited.

If you look at any moment in a story and the reason why the person is

doing what they’re doing, and then just ask yourself if the reason could be

something more interesting, or if the character’s mood could be better shown, chances

are you’ll be able to engage the reader and start building momentum so that

you’re already up and running by the time you get to the take off point.

If you found this post useful, please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on March 14, 2013 11:00

March 11, 2013

When To State The Obvious In A Story

Not only is it difficult to know how much information to give readers

so they know what’s going on, it’s also tricky knowing when to give it to them.

There are many ways to do it right, but there are two very specific

ways to do it wrong.

One is signposting, where you say up front what’s about to happen, and

then it happens. You end up stealing your own thunder.

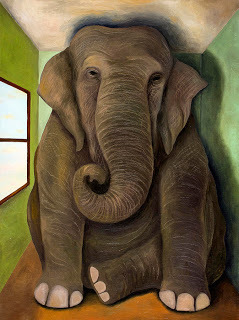

The other is burying the lead, where you put off mentioning the

elephant in the room, so that when you do eventually bring it up not only is

everyone taken by surprise, but now it appears to be a teleporting elephant.

Signposting is usually due to a feeling that things won’t be clear unless

you point out what’s about to happen.

This can take the form of a preamble: The story I’m about to tell you changed my life forever...

Or it can be a case of telling readers what you plan to show them anyway:

Mary was angry. She clenched her fists, stormed

over to where Tina was having lunch, and spat in her face.

The root cause is insecurity.

Deep down you suspect if you don’t preface what you’re about

to say maybe your intention won’t be clear.

And you could well be right. But

explaining a joke doesn’t make it funnier. And neither will blurting out the

punchline before the set-up.

It’s a case of having to trust in what you’ve written, and if it doesn’t

work (which it won’t a lot of the time), taking your lumps and learning from

it.

Burying the lead is the opposite problem. This is where you mention

something important much later than you should have.

Often this is just an oversight. As the writer you know what’s going

on, who and what is in a scene, but you can forget the reader isn’t aware of

these things. A critique partner is the best cure for this.

But sometimes a writer can get so carried away describing the cave

they don't mention the dragon that’s living there. And when they finally

do, it seems odd no one noticed the big, scaly monster for so long.

It can be an easy thing to convince yourself you’re building up

to a big reveal. Tension, suspense, anticipation—these are all solid narrative

techniques. But it has to make sense. Choosing not to reveal the obvious for effect will seem contrived.

As long as you pay attention to the POV, you should be able to avoid

this, or at least be able to recognise it when it’s pointed out. If the POV

character is aware of something then the reader should be too.

Both signposting and burying the lead can be used to a writer’s advantage,

if you use them to misdirect or to add voice.

For example, in the case of signposting:

His parents had called him Quiet

Joe because he was such a noisy child. He was always shouting or screaming or

laughing for no reason and eventually someone would say, “Quiet, Joe” and the

name stuck.

Even though the first line provides an explanation, it doesn’t make

very much sense until the rest of the story.

Or, for burying the lead, something like:

When he got home everything was

as he’d left it. The dishes were unwashed in the kitchen, his clothes were on

the bedroom floor, his wife’s body was in the lounge, the lawn still needed

cutting. He couldn’t decide which to deal with first, so he made a list.

Revealing the wife’s body so far down sets the tone for the story. But

it has to be clear that the approach is deliberate. Not that that guarantees it

will work, but a reader might at least give you a few paragraphs to see if it

goes anywhere interesting.

In both these examples, going against expectation is what makes it

work. First, though, you need understand the form and know what the expectation is.

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

*

Check out more posts on the craft of writing from numerous bloggers at The Funnily Enough.

Published on March 11, 2013 11:00

March 7, 2013

The Perfectly Balanced Story

When you tell someone a story in person, you probably know the person

you’re talking to. You will at least have a rough idea of how familiar they are

with the people and places you’re referring to. And if you misjudge, they can

always ask you questions.

In fiction, it’s much harder to know exactly how much information a

reader needs or wants. And even if you did, it would be impossible to provide

since you’ll have more than one reader, and each will have different

requirements.

You can’t get the balance right, because there is no way to please

everyone.

However, that doesn’t mean you can’t get it wrong. You may not be able

to please all the people all the time, but you can certainly piss them all off.

You can treat the reader like someone who knows nothing about the

world you’re writing about and start from scratch, explaining every little

thing, and for some types of stories that works fine (perhaps by having a

character who’s new and needs to be instructed in how things work). But that can still feel plodding and

pedestrian.

As with most techniques, deciding on the approach is only the first

step—you still have to make it interesting and entertaining.

The right method poorly executed is no better than the wrong method.

In my own experience, I find what usually pulls me out of a story that seems to be rolling along just fine is either too much information (and it gets boring), or too

little (and I get confused).

And while you can’t please everyone, you can at least be aware of potential

problem areas that nobody enjoys.

Too much info breaks down into three areas:

Rambling

You start describing something, whether an object or a philosophy or

the inner workings of a combine harvester, and you just can’t stop. You’ve read

long, sweeping passages by other writers that seemed poetic and lyrical, so

maybe what you’re writing will be received in the same way.

I think for most writers have trouble policing themselves but getting

someone to read your work will usually bring it to their attention. And if no

one says it’s terrible, are they telling you it’s great or not saying anything

at all? Because if it was worth spending all those words describing the

sunlight shimmering on the lake, don’t you think someone would have mentioned

it?

Redundancy

In the real world you often have to repeat yourself. A guy tells his wife what happened at work, then

he tells his mate down the pub, then he has to explain it to the police. And

then there’s the lawyer, and the judge and jury...

For a reader, seeing the same information in various different

contexts is the same thing over and over. That’s not to say you should never

repeat yourself on the page. Readers occasionally need a reminder, or a plan

might be complicated enough to bear clarifying, but there are ways of investing

each version with its own uniqueness.

The man might tell his wife about the girl who ran out of the boss’s

office screaming, but he might add that it was the same girl he slept with at

the office party, and deny the same to the police when she turns up dead.

When information gets repeated, it’s the parts that change that

attract the attention.

Irrelevancy

Going off on a tangent or providing supplementary details that fill

out the picture can be quite interesting, even entertaining.

But most of the time it slows things down and isn’t as interesting as

the writer thinks.

If the story’s working, the reader will want to get on with it. If you

indulge yourself in Tarantinoesque banter and nobody minds, what does that say

about how engaged the reader is with the main action?

If it’s done well, and if the pacing and structure are designed to

accommodate it, I definitely think it can work, but it has to be concise and it

helps if it’s funny.

Too little information is usually due to the following:

Assumptions

By the second or third draft the writer knows pretty much everything

there is to know about the world he’s created and the people in it. This

knowledge can make things appear to be clear when they aren’t.

Personal bias can make arguments seem logical when they aren’t.

Motivations for the way characters behave may be in the writer’s head but not

in the text. Information that was in old drafts may have been removed, but feel

like it’s still in there.

This is probably the easiest one to fix. Nobody will understand what’s

going on.

Intentional Vagueness

In order to make things mysterious and intriguing why not make things

a little obscure?

Holding back information is of course a tries and tested way to hook

the reader, but there are only so many questions a person can take before they

start requiring a few answers.

There’s nothing wrong with needing to find things out—it’s a key part

of most stories—but you can’t keep piling up the mysteries without any

development. It makes the character seem stupid and the reader feel like

they’re wasting their time.

Unimportance

A character goes off to do something but it’s got nothing to do with

the story, you just needed them out of the way for a while. It doesn’t matter

what they do in that time, it has no bearing on the narrative so why waste time

mentioning it?

The reader, however, does not know whether it’s relevant to the story

or not, and since things the reader doesn’t know often turn out to be

important, it’s a nagging distraction and a source of frustration to have

something brought up and then never referred to again.

If it’s important enough to mention, it’s important enough to go into

detail. If it isn’t worth going into detail, it isn’t worth mentioning in the

first place.

When it comes down to it, I would say it’s better to have too much

information rather than too little. Neither is great, but with too much you

still know what’s going on, even if some readers end up skimming. With too little, once you get lost

or confused, it can put you off reading any further. Yes it might all make

sense in the end, but who wants to struggle through another couple of hundred

pages to find out?

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

*

Don't forget to check out The Funnily Enough for the latest blog posts on writing from around the web.

Published on March 07, 2013 10:00

March 4, 2013

Worst Case Scenario Is Something To Aim For

Sometimes in life we get worried and worked up about something and it

turns out not to be as bad as we had feared. The terrible thing we were

convinced was about to happen doesn’t materialise. It’s good when it turns out

that way. In real life.

In a story, however, that kind of build up and release is not rewarding,

it’s disappointing.

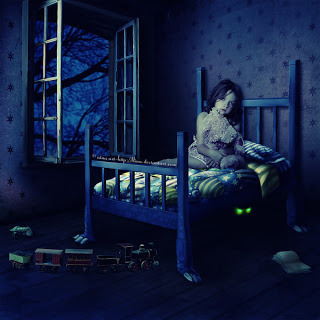

When a character thinks: I hope the killer doesn’t look in this closet

where I’m hiding... definitely have the killer open the closet door.

On a basic level, you always want to choose the path of most conflict.

If a robber is trying to sneak past security guards, having him slip past

without any problems isn’t going to be a very interesting robbery. You need

problems and for things to go wrong in order to create an interesting

narrative.

But this principle also applies to a character’s reason for being in

the story in the first place.

Let’s take a woman at her younger sister’s wedding. Seeing all this love

and romance and happily ever after stuff makes her freak out that she’ll be alone

and single for the rest of her life.

That fear drives her to get involved with the wrong guy, to do what he

wants, whatever it takes to make him happy. But in the end she realises it’s

better to have no man than the wrong man.

You might think the fear she had at the beginning is enough to show motivation

for what happens to her, and it comes full circle when she has her epiphany.

And you could do it that way— I’m sure readers will get why she does

what she does.

But you’d have far more impact on the reader if you showed her getting

everything she wanted—the rich handsome, the beautiful house, the posh new

friends—and showed how she changed and did whatever it took to get all this.

But she had to abandon her friends, lost contact with her embarrassing

family, ended up stuck in her new home entertaining people she doesn’t even

like.

Then the fact she’s utterly alone and unhappy, the feeling she did all

this to avoid, will resonate strongly with the both the character and the

reader.

Then her realisation at the end will carry weight.

Whenever a writer brings a fear or warning to the reader’s attention,

it’s tantamount to an agreement with the reader that just such a thing will

take place. The reader might not be all that aware of this agreement and the

writer may have just mentioned it in passing to add motivation, but the

expectation has been created, and it needs to be met.

Even if there is a way to avoid the horrible outcome in a plausible and

entertaining way, don’t. Falling into the worst possible situation is the best

thing for a story. It’s not easy to write and it may not be fun for the

characters involved, but it’s the most entertaining version for the reader.

In fact, the only time you shouldn’t have it work out the way the

character was most afraid of is to have it turn out even worse.

Making the character aware of the possible negative outcomes (and

through them, also making the reader aware) enables you to set up foreshadowing,

create tension and anticipation and establish stakes. But all that dissolves

very quickly if they just stroll through the story never having to face those

fears.

Whatever the character dreads most is what they should end up having

to deal with at some point.

This is by no means a hard and fast rule. It’s just that if the character

is worried about a monster under the bed, it tends to be a more fun if there

really is a monster under the bed.

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on March 04, 2013 10:00

February 28, 2013

A Plot Problem Is A Character Problem

If a story seems a little dull, if the plot doesn’t seem to be very engaging,

you could deal with it by having more stuff happen, more people running around,

new characters, additional subplots and so forth.

Usually, though, the problem is not in what’s happening, the problem

is who’s doing it.

If the character hasn’t been created with enough depth, what they get

up to will feel arbitrary and unsatisfying. If the plot isn’t holding people’s

attention, the first place you should look is character.

Let’s say my story is about a man who sees a murder being committed.

He goes to the police but then he becomes a target for the murderer.

Pretty standard sort of story. Maybe seeing the murder will be a

suspenseful scene. And once the murderer comes after him, things will probably

be quite exciting.

But what about the bits in between? How do we stop all the

setting up we need to do from feeling mechanical and perfunctory? It’s part of

the story, you can’t just skip it.

Thing is, at the moment our character is just ‘a guy’. We don’t really

know anything about him.

Who would be a good person to have witness a murder?

Maybe someone who is also committing a crime at the time, say a thief. So he

can’t really go to the police. Come to think of it, why would he care anyway?

Well, let’s say there’s a big reward. He’s a thief, he likes money. But the police

might ask awkward questions.

Maybe he can tell a buddy what he saw, the buddy can tell the cops, collect

the reward and they split the money. But then the murderer targets the buddy

and kills him. Now our thief is pissed off and feeling guilty...

I don’t know how many movies I just ripped off there, but as I developed my main character, the story automatically developed a more

interesting plot.

He went from being some guy to being a thief who has a close

buddy, he feels guilt and wants revenge, plus he has a particular set of skills

and contacts in the underworld. The options for what happens have become more specific

but also more interesting.

On the other hand, maybe I start with an MC already in mind. Let’s say

I’m getting driving lessons and my driving instructor is a bit of a character.

I think he’d make a good lead in a story. I already know what he looks like and

the kind of sarcastic jokes he makes, all I need to do is slot him in fully

formed.

So, I come up with a story. A driving instructor is giving lessons to

a woman, but she insists on being picked up at strange times from strange

places. Eventually she confides in him that she’s learning to drive in secret

so she can get away from her abusive husband. If he found out, he’d kill her.

Our hero is glad to be of help. But then one day she misses her lesson

and then she turns up on the news dead, her husband crying and vowing to hunt

down her killer.

I could probably come up with a reason for the instructor to go to the

police or even confront the husband directly, but I could just as easily not. Why

wouldn’t he learn of her death and just shrug his shoulders? Making him go

after the husband because that’s what I want him to do won’t necessarily make sense.

Why would he pursue the guy? Maybe he’s an ex-cop who was kicked off

the force for sticking his nose where he shouldn’t and driving instructor was

the only job he could get. Maybe the husband is connected to organised crime,

the same crime organisation that arranged to have him fired.

That’s a little corny, I know, but my point is I can still keep the

qualities of my real life driving instructor, and work in more specific qualities

that make his actions more plausible.

But it’s worth bearing in mind that the things I’m coming up with are

designed to be relevant to the type of story I’m telling. That’s not by accident.

I’m also coming up with other characteristics and rejecting them.

My driving

instructor could have been captain of his high school football team, loves

pickles on everything and have a mad crush on Dame Helen Mirren, but those

things won’t have much effect on how he deals with his dead student.

I could keep all those little details if they appeal to me, certainly

they’ll give me a fuller picture of who this guy is, but I’m aware that they

won’t make the plot any more interesting—so I need to come up with something else,

either instead of or as well as.

Or at least, I can’t see how it would affect the story. You might see

it differently.

If the story was about a girl in love with a guy who rejects her, and

she was captain of her high school basketball team where she was infamous for

playing dirty and winning at any cost, then that approach to life could very

well affect how she behaves as a grown up.

The important thing is to add depth through things that change the way

a character behaves. You can also add other details, but it’s the behavioural idiosyncrasies

that are going to help the story become more interesting. If it doesn’t affect

their actions, it won’t impact the plot.

If you found this post vaguely interesting, please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on February 28, 2013 10:00

February 25, 2013

A Character Needs A MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is the thing a character wants. It’s what he sets out to find,

hide, build or destroy. Its existence is what drives a story forward.

It was a term coined by Alfred Hitchcock, and the reason he gave it

such a silly name is because he believed it didn’t really matter what it was,

just as long as it existed and the need it represented was clear.

The important thing is that it’s tangible. An object, a person, a place. Some thing. If a character wants to be happy,

that isn’t a MacGuffin. If he wants to be happy by stealing the Hope Diamond

and becoming rich, then the diamond is the MacGuffin.

But you could replace the diamond with any similar object and it would

work just as well. The important thing to remember is that it needs to be a

thing, not an idea or an attitude.

Hitchcock’s films demonstrate exactly which parts of MacGuffin are

essential and which aren’t. In the movie North

By Northwest, the main character, Roger Thornhill (played by Cary Grant),

is being chased because of a top secret microfilm. It’s never explained what’s

on the microfilm or what the bad guys intend to do with it, but the fact all

these shady characters are after it provides enough of a MacGuffin for the

audience to buy the events of the story.

It’s not the relevance of the microfilm to world safety that keeps the

audience engaged, it’s what Cary Grant does about it. That’s not to say you can’t

make the MacGuffin something the audience can care about, but it’s far more

important that we are aware that these characters care about it in their world.

One of the easiest ways of achieving that is to have more than one person after

it.

That’s an extreme example where the actual reason why the MacGuffin is

such a big deal is left out of the equation. When the stakes are big enough,

the reason tends to be self evident. The Ark of the Covenant in Raiders has to

be kept safe form the Nazis. The asteroid in Armageddon has to be destroyed before

it hits Earth. You don’t really need to go into great detail to persuade an

audience that these are goals worth pursuing.

Once the audience believes the need of the character to obtain their chosen

MacGuffin, it can provide purpose for the entire story. You don’t really need

to worry about it anymore. People are much more interested in the journey than

the destination. You still need a destination, and one worth going to, but it’s

the journey, and more importantly, the difficulties overcome on that journey,

that interests readers.

It can end up that the MacGuffin wasn’t worth pursuing—In The Maltese Falcon, the falcon statue

turns out to be a fake.

Or you can switch MacGuffins—Star wars starts as a search for R2D2,

then rescuing a princess, then destroying a moon (hold on, that’s not a

moon...)

And in North By Northwest,

everyone’s after the microfilm except the main character, who has no idea what’s

going on. What he wants is his life back. But the only way to do that is...

exactly.

There needs to be this thing

people want and you have to be able to name it at any point in the story. It

may change, it may never have existed, but no matter where you are in the

story, you should be able to say, What’s happening now is because of this.

Not a desire or an emotion or an outcome. If a woman is kept captive

and want to escape (not a MacGuffin) and the only way is to kill the captor (he’s

the MacGuffin) but she needs a weapon (a more immediate MacGuffin) and she dreams

about getting back to her wonderful rich boyfriend (unnecessary backstory) who used

to whip her in his private sex dungeon (Bestseller!).

As long as it’s clear what they want to obtain (whether to find it or

kill it or rescue it) and the reason carries a believable imperative, the

reader will engage with what the characters do about getting there.

You have to be able to believe the MacGuffin is important in the lives

of these people you’re reading about. You may need to go to great lengths to

establish that, or you may not need to say anything beyond: They have the

President’s daughter. But you have to crystallise it into a solid, real world

object that the reader can understand and appreciate.

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on February 25, 2013 10:00

February 21, 2013

Starting A Story In The Middle

Starting a story in the middle of action is fine if that’s the kind of story you’re telling. Generally, that'd probably be something in the adventure/thriller genre. But not all stories suit the kind of opening where assassins are chasing a monkey over the rooftops of Buenos Aires (although I

have no doubt that book would be a huge hit).

And even if you are writing in that genre, you might prefer to build up to those kind of scenes. Having someone hanging from a twelfth storey window ledge can feel very hackneyed. We don’t know the character, we don’t know why he’s up there, and frankly, we don’t care. It’s not always enough to just put some random person in peril.

A high tempo opening scene might not be right for your story and it quite often reads like an attempt by the writer to inject the story with drama

it hasn’t really earned and can feel contrived.

But an energetic set-piece out of an action movie isn’t the only way to make the reader feel they’re in the middle of something interesting. Another way a story can benefit from starting in the middle is to start in the middle of emotion.

Unless a character is a newly produced replicant, chances are they will enter your first scene in a particular mood. You can use that mood to pull in the reader. It doesn’t really matter what that mood is, as long as it isn’t neutral.

Often, because the story starts in normal mode, with weird stuff to happen later, the main character is fairly relaxed. They may have certain issues to deal with, but they’re dealing with them. While that’s perfectly plausible and realistic, it’s also quite dull to read.

Just because they aren’t running for their life, doesn’t mean they should just be treading water.

An easy way to lift them out of that kind of flat introduction is to have them already emotionally affected by something. It doesn’t have to be a big emotion, they don’t have to be angry and shouting, it can be sad, vengeful, jealous, whatever. It depends on their personality and what situation they’re

in, that is to say it helps if you choose their emotional state to reflect he

type of person they are, and then express that emotion in a character specific way.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that how you show the emotional state to the reader makes a difference. Literally showing the emotion, i.e. tears on the face of a sad person, spittle flying out of the mouth of an angry person and so on, isn’t very engaging. It’s just vivid description (nothing wrong with that, just not useful for our purposes here).

What works much more effectively is to show emotion through behaviour. What are they doing because of the emotions they’re experiencing? Having them sitting there thinking about stuff (which emotionally wrought people often do)is not going to help you get the reader caught up in the start of the story.

And just because this technique can catch a reader’s attention doesn’t mean it will without a little creativity on your part. A guy with a gun is scary in real life, in fiction it’s any crappy TV show.

A direct cause and effect (he says he’s been cheating on her, she bursts into tears) doesn’t offer much in the way of intrigue.

If a policeman knocks on a woman’s door and tells her they’ve found her husband murdered and she punches the air and whoops with joy, that’s a bit more attention grabbing.

And it makes for a more dynamic scene if the character’s emotions interfere with what she needs to do. If the husband tells the wife he’s leaving her at a wedding where she’s supposed to give a speech on the power of love, you can get a lot of mileage out of how she reacts.

You can make this technique work for just about any emotion, but it’s important to avoid anything that’s along the lines of stunned, traumatised, bored, shy, icy, or any other emotion which is expressed through non-action.

Either that or find an active way to express it. Heart-broken people do spend a lot of time in bed, but they also set fire to their ex-lover’s car.

Obviously, those “leave me alone” emotions exist and may be relevant to characters in your story, but my point is specific to openings and using emotions to hook readers. “Crawl into a hole” emotions won’t serve you there so don’t use them.

Right, I'm off to finish my new Argentinian spy thriller Orangutango!

If you found this post useful, please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on February 21, 2013 10:00

February 18, 2013

What Makes An Idea Worthwhile?

Let’s say you have a character who is hungry. You decide to show the reader that he’s hungry by having him stare into a baker’s window looking at all the lovely cakes.

So he’s drooling, stomach rumbling and all these delicious cakes, which you describe in great detail, are just out of his reach.

You ask yourself, does what I’ve written convey my intention? And if you think it does, then that’s that.

But when other people read what you’ve written, they may not like it. They may say, yes, he’s hungry, but so what? It’s a lot of lovely cake description, but I know what a cake looks like. Yes his need for food is apparent, I get it. But why are you telling me?

And at that point you look back at the story and you ask yourself, why did I want the reader to know my character is hungry?

Because the decision to portray a particular element to the reader is only a small part of the writing process. Much more important is why you think the reader needs to know this. It can be tempting to assume the thoughts that occur to you wouldn’t have popped into your head if they didn’t have a reason to be there. That you don’t need to know what those reasons are, you’re just the conduit.

Which would be fine if those thoughts really did all fall into place without your involvement, but that’s rarely the case.

If I have the same hungry man steal a loaf of bread and that leads to him being chased by a singing French policeman (for example), does the stealing of the bread show him to be more or less hungry than him staring at cakes? I would say there is no obvious difference in that regard. Both show his desire for food.

But taking the bread leads to a series of events. Standing, looking, drooling, doesn’t.

What a scene does in isolation is only of use if you’re writing about a singular event. But a story is not about one moment. It is not a series of unrelated events. And it’s the writer’s job to work out the connections and connect them.

And while the poetic side of you might want to express itself through beautifully written description of dark, rich chocolate swirls that both capture the bitter desires of a man who hasn’t eaten for days and the decadence of the society in which he lives, that isn’t enough. Where do you want to go with that feeling?

Only when you know that can you look at what you’ve written and ask yourself: does this truly convey my intention? And while that answer may be a little more difficult to work out, it will also be a much better indication of whether what you’ve written will be worth reading.

If you found this post useful, please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on February 18, 2013 10:00

February 14, 2013

Readers Have Needs

Different readers will have

different things they like to read. Genres, style, subject matter – all these

things will vary from person to person.

But there are some qualities in

fiction that are the same for everyone. These are the things we all look for in

a story, and they are also how we judge whether something is a good read.

A Need For New Information

On a basic level we all like to

learn things. Obviously, not everyone is interested in the same subjects, but

generally speaking, most people gravitate towards information they weren’t

aware of before. Whether it’s the news or practical advice or just a piece of

trivia.

That’s not to say any random fact

is going to have people rapt with attention, but knowing that we all have a

genuine fascination with learning things can help when writing a story. And

conversely, telling people stuff they already know can make their minds wander.

It’s going to make a difference

if the thing you’re telling the reader has substance. If one character tells

another an easy way to defrost a freezer without having to take out all the

food, even though it may have little to do with the plot of the story, it will

interest the reader (no, I don’t actually have a way of doing that).

If you can work it into the

narrative, it will have a much stronger effect. If the ballistics report

reveals the bullet that killed the president is untraceable because the killer

soaked it in washing up liquid before loading it in the gun, which prevent

striation marks from forming, readers are going to go, Oh, I didn’t know you

could do that (you can’t do that, I just made it up).

The need for information goes

beyond this kind of extra detail. If a character decides to go and do something

or find something out, if they are in the process of discovering something new

themselves, that will be of interest to the reader to. And conversely, if the

character is going to do something they’ve done before (wake up, brush teeth

get dressed, take the kids to school), that will allow the reader’s mind to

wander.

Need To Connect With Characters

You probably noticed I just did a

series of posts on this topic, so I won’t go into great detail about how to do

this, but you should bear in mind that readers want a character they can spend

time with.

Even a Mary Sue or painfully

corny wish fulfilment type of character is preferable to someone who whines and

complains and doesn’t like anything. As in real life, those people may have a

valid reason to be like that, but they’re not much fun to be around.

Even a tortured soul who has

great depth and hidden qualities is going to lose the reader’s interest if

those qualities remain hidden too long.

Most readers actively want to

relate to the characters in some way. They aren’t sitting there thinking, Come

on then, impress me. They’ve already committed time just by turning the page

and they’re hoping it’ll be worth it.

Need For Solutions

Dramatic storytelling consists of

problems. Whether a conflict or a threat or a search, something has to be done

or there’s going to be trouble. The reader wants to see the problem sorted out.

They want the conflict resolved.

How it’s resolved, what solutions

are employed and whether they succeed or not, is a matter of individual choice

for the writer. But that’s what the reader is waiting to find out.

Every answer you come up with may

lead to more questions, more problems, but that’s okay. As long as new

questions are asked, new answers will be expected.

What isn’t okay is to set up the

problem and then go off and deal with a bunch of other stuff. Because a problem

that doesn’t have to be sorted out isn’t really a problem.

Need For Understanding

Readers want to know what

happened. They want it to make sense, and they want to understand who did what

and why.

Sometimes that isn’t completely

possible, and that’s okay. But the reader didn’t spend all that time to be

told, And the mystery remains to this day...

But as well as the story having a

purpose to it, readers also want it to be consistent and logical. They want the

world to feel like a real world (even if it isn’t) and to be able to see it and

have a clear picture of where everything is.

There are writers who insist the

reader needs to decipher what’s going on and where they are, which is fine,

mostly people go in knowing that’s the expectation with that kind of writer.

But that tends to end up feeling more like doing a puzzle than reading a story.

Need For Closure

You can keep a story going

through various ups and downs (in fact you should do that), but eventually you

need to come to some sort of end.

Readers want an ending. Even

though it isn’t like real life, and it can sometimes feel a bit pat, that’s

what they want.

That doesn’t mean it has to be a

Hollywood, they all lived happily ever after type of ending (although those are

pretty popular). It can be quite vague

and open-ended if you want, but it has to convey a definite sense of the

journey being over (even if it’s going to start again with a sequel).

The thing to remember about

satisfying endings is that they need to be set up. A guy investigating a murder

can’t just drop dead of a heart attack before he catches the murderer. You have

to introduce some kind of goal, and it’s that goal that will provide the

closure (even if it’s not in the way the reader was expecting).

Need To

Be Entertained

This is

obviously a big umbrella word for lots of different things. But it should still

be seen as an important aim for a writer, to entertain the reader.

People

read a lot of different types of books but the reason we absorb words to create

ideas and picture in our heads is because we enjoy it.

Whether it

a sense of wonder, visceral emotional reactions (which can be anything from

laughter to comfort to being thrilled), provoking thoughts, or a transcendent

moment that changes the way you view the world, stories provide a way to live

through other people, and those people need to provide enough stimulation for a

reader to feel like they had a worthwhile experience.

Easier

said than done, I know. But try to remember you’re putting on a show, and open

strong. Not in any particular place or in any particular style, just with

something you think is interesting and captures the tone of what you’re trying

to do.

If you found this post useful, please give it a retweet. Cheers.

Published on February 14, 2013 10:00