When To State The Obvious In A Story

Not only is it difficult to know how much information to give readers

so they know what’s going on, it’s also tricky knowing when to give it to them.

There are many ways to do it right, but there are two very specific

ways to do it wrong.

One is signposting, where you say up front what’s about to happen, and

then it happens. You end up stealing your own thunder.

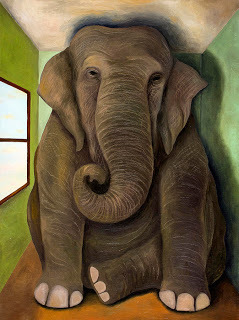

The other is burying the lead, where you put off mentioning the

elephant in the room, so that when you do eventually bring it up not only is

everyone taken by surprise, but now it appears to be a teleporting elephant.

Signposting is usually due to a feeling that things won’t be clear unless

you point out what’s about to happen.

This can take the form of a preamble: The story I’m about to tell you changed my life forever...

Or it can be a case of telling readers what you plan to show them anyway:

Mary was angry. She clenched her fists, stormed

over to where Tina was having lunch, and spat in her face.

The root cause is insecurity.

Deep down you suspect if you don’t preface what you’re about

to say maybe your intention won’t be clear.

And you could well be right. But

explaining a joke doesn’t make it funnier. And neither will blurting out the

punchline before the set-up.

It’s a case of having to trust in what you’ve written, and if it doesn’t

work (which it won’t a lot of the time), taking your lumps and learning from

it.

Burying the lead is the opposite problem. This is where you mention

something important much later than you should have.

Often this is just an oversight. As the writer you know what’s going

on, who and what is in a scene, but you can forget the reader isn’t aware of

these things. A critique partner is the best cure for this.

But sometimes a writer can get so carried away describing the cave

they don't mention the dragon that’s living there. And when they finally

do, it seems odd no one noticed the big, scaly monster for so long.

It can be an easy thing to convince yourself you’re building up

to a big reveal. Tension, suspense, anticipation—these are all solid narrative

techniques. But it has to make sense. Choosing not to reveal the obvious for effect will seem contrived.

As long as you pay attention to the POV, you should be able to avoid

this, or at least be able to recognise it when it’s pointed out. If the POV

character is aware of something then the reader should be too.

Both signposting and burying the lead can be used to a writer’s advantage,

if you use them to misdirect or to add voice.

For example, in the case of signposting:

His parents had called him Quiet

Joe because he was such a noisy child. He was always shouting or screaming or

laughing for no reason and eventually someone would say, “Quiet, Joe” and the

name stuck.

Even though the first line provides an explanation, it doesn’t make

very much sense until the rest of the story.

Or, for burying the lead, something like:

When he got home everything was

as he’d left it. The dishes were unwashed in the kitchen, his clothes were on

the bedroom floor, his wife’s body was in the lounge, the lawn still needed

cutting. He couldn’t decide which to deal with first, so he made a list.

Revealing the wife’s body so far down sets the tone for the story. But

it has to be clear that the approach is deliberate. Not that that guarantees it

will work, but a reader might at least give you a few paragraphs to see if it

goes anywhere interesting.

In both these examples, going against expectation is what makes it

work. First, though, you need understand the form and know what the expectation is.

If you found this post useful please give it a retweet. Cheers.

*

Check out more posts on the craft of writing from numerous bloggers at The Funnily Enough.

Published on March 11, 2013 11:00

No comments have been added yet.