Sheila Peters's Blog

May 11, 2025

On reading, for Mother’s Day

My mother taught hundreds of children to read, her own favourite pastime, over her long career as a Grade One teacher. She instilled that love in all three of her children. Just yesterday I mentioned to a friend the oddity of meeting someone who didn’t read at all for pleasure. We looked at each other in amazement. “What do they do?” we both wondered.

Since Mom is no longer here to thank once again for encouraging me to bury my head in books as a child and for sending me books as gifts as an adult, I’m sharing some thoughts about reading and writing triggered by two wonderful writers. A friend introduced me to Helen Humphreys a couple of years ago. My sister sent me a poem by Marie Howe a few weeks ago. Thank you both!

They’re very different writers – Helen Humphreys is a Canadian poet and novelist with deep ties to England. The Frozen Thames strings together snapshots of events staged on the Thames River the forty times it froze solid between 1142 and 1895. It’s a unique and fascinating perspective on English history. She has also set several of her novels in WW II England: The Lost Garden (2002), Coventry (2008) and The Evening Chorus (2015). They shine with the kind of luminescence found in works by Michael Ondaatje and Anne Michaels.

Marie Howe, for a time the poet laureate of New York, was raised in a Catholic family, the oldest of nine children. Her poetry, too, is luminescent at times, but also glints with the sly wit of Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska. I loved her New and Selected Poems (which just won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry) and was taken by one poem in particular. In“Why the Novel is Necessary but Sometimes Hard to Read” Howe’s combination of humour and deep insight admits to the complexity reading novels presents. In the poem, she writes about how all the paraphernalia a novel requires – character, plot, setting – can be intimidating or just plain tedious:

You come upon the person the author put there

as if you’d been pushed into a room and told to watch the dancing—

—pushed into pantries, into basements, across moors, into

the great drawing rooms of great cities, into the small cold cabin or

to here—beside the small running river where a boy is weeping,

and no one comes . . .

and you have to watch without saying anything he can hear.

One by one the readers come and watch him weeping by the running river,

and he never knows

unless he too has heard the story where a boy feels himself all alone.

How many children have been comforted by books as the weeping boy might have been? Comforted by kind librarians, by thoughtful teachers like my mom, and by writers willing to put in the work to create the magic allowing them to enter those other worlds.

Helen Humphreys takes the connections a step further in this excerpt from The Lost Garden (2002) when the main character, gardener Gwen Davis, sits listening to a young Land Girl read To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf to a young Canadian soldier.

The book is the shared experience, the shared intimacy. There is Virginia Woolf, dipping her pen in ink, looking up from the page with Lily on the lawn, to the view out her window. Here am I, looking across the room to the summer dark beating against these mullioned panes. There is Jane reading the words aloud to a young soldier sitting beside her. It is a place we have all arrived at, this book. The characters fixed on the page. The author who is only ever writing the book, not gardening or walking or talking, and while the reader is reading, the author is always here, writing. The author is at one end of the experience of writing and the reader is at the other, and the book is the contract between you.

Humphreys goes on to say that, in order to write,

… all of life is kept back, all the petty demands of the day-to-day. The heart is a river, the act of writing is a moving water that holds the banks apart, keeps the muscle of words flexing so that the reader can be carried along by this movement. To be given the space and the chance to leave one’s earthly world Is there any great freedom than this?

I thank them all, those writers, for the ways in which they have opened up my life, offered not only insights into the lives of others, but also comfort in my own. And I thank their mothers and mine.

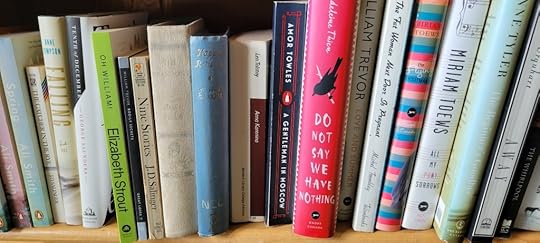

Elizabeth Hazlette photo

Elizabeth Hazlette photo

November 29, 2024

A one-year anniversary – let there be light

A new navigational beacon was installed at Grief Point Nov. 29, 2023 by the Marine Civil Infrastructure unit of the Canadian Coast Guard, 87 years after the first one was installed in 1936. There is, they tell me, no record of what precipitated its establishment, of what particular grief signaled the need for a light.

There is much speculation about why this rather innocuous point is so named. It’s a low shelf reaching out into Malaspina Strait, whose only danger to navigation is that an unwary boat might be pushed onto the shifting gravel that makes up its beach. Anyone shipwrecked could just walk a few feet up onto solid ground.

The BC Geographical Place Names database says the name was officially adopted in 1945 “based on British Admiralty Chart 580, 1862 et seq. Origin/significance not known.” The database also refers to historian Athelstan Harvey, who speculated that its name came because “it is an exposed spot in a westerly wind, causing grief to many a mariner.”

That may well be the case. Further correspondence with BC Geographical Place Names says, “The version of British Admiralty Chart 580 we have in our office is from 1860, with corrections in 1864, and has Grief Point labelled, so I think it’s safe to say the name existed by 1864.”

The men behind the early coastal mapping expeditions are named on the charts themselves and their work led to the establishment of the first beacons on the coast in the 1860s. Captain G. H. Richards, conducted the Vancouver Island Survey between1860 – 1862. Another name on the 1860’s chart was Pender.

In Boats, Bucksaws and Blisters by Bill Thompson (1990), Golden Stanley (GS) interviewed Roy Padgett (RP) in 1982 about Grief Point’s name:

“RP: When they were logging from Fiddlers, that road came straight down and the log dump was right where Gus Courte used to live … Well, apparently, when they dumped the logs in there, every so often they’d get caught with a westerly, and they’d get around the point [the logs would]and they got in the habit of saying there’s nothing but grief here,” and that’s the story I heard.

“GS: Well, it goes back further than that because … I think it was Pender who came up on the Trumpet to survey the coast at that time … and his log is lost, but the name goes back into the eighties [1880s] and from there on it’s called Grief Point. Before that, there’s no name on it. It was during his survey that the name became Grief Point. His log, apparently, went over to England and became lost. There’s no record of it …”

qathet Museum and Archives’ website also has notes on the naming.

“There is some speculation as to where the name Grief Point comes from. One possibility was that it refers to an epidemic within the indigenous population, another is of a wreck in which three men perished, while another is that it refers to the tugs and boats that would shelter behind the point during storms, to get away from the ‘grief’.”

Mom’s late friend, Fran Gregory, who used to live just above the point, painted five or six tugs lined up there with their boom stretched out behind them.

The museum site goes on to say, “At one point the area was also referred to as ‘Pneumonia Flats’ and referred to the flat area by the lighthouse in Grief Point. This area was a farm from the 1880’s and was sold in the middle 1960’s for a sub-division.”

Oddly enough, the references to the Tla’amin peoples’ use of the area talk about the protection it provided. Sliammon Life, Sliammon Land by Dorothy Kennedy & Randy Bouchard, states:

“The Sliammon name for Grief Point is Xákwuem, “having cow parsnip” referring to the abundance of “Indian rhubarb” (cow parsnip) that used to grow here. This was an important camping site because it afforded good protection from the southeast wind. In more recent years, before the area was developed, the Indian people planted gardens here.”

I’ve never understood the reference to protection. When my grandfather, who had lived many years in Shetland before bringing his family first to Hernando Island and then to Powell River, a man who undoubtedly knew something about wind, found out my mom and dad were planning to build a house in the new subdivision down at Grief Point, he exclaimed. “Surely you’re not going to build in yon windy hole!”

And windy it is. In rough weather we’ve seen tugs trying to round the point, sometimes looking as if they’re not moving at all. Other times, they actually start to slip back and end up executing a rather perilous looking turn to head into the shelter below Penticton Avenue.

The new lighthouse is the third one we’ve seen since my family moved down to the new subdivision in 1968. I think, from the photos, there was at least one between the first in 1936, and the one removed to make way for the 1968 version. TJ Courte, whose family lived at the point for many years, said her mom always said the beacon belonged to the queen, and they weren’t to climb on it!

I’ve tracked down a couple of old photos and of course, there was one when we built down here. My dad wrote several letters trying to get the lighthouse plot tidied up so it fit more neatly into the new subdivision, which they finally did. And they took up his offer to mow the lawn around the beacon in exchange for the use of the electrical outlet in the body of the tower, an outlet connected to the BC Hydro grid.

The first (I think) beacon.

The first (I think) beacon.

The beacon in the distance in the market garden days.

The beacon in the distance in the market garden days.

The second beacon behind the 1968 version.

The second beacon behind the 1968 version.

The new tower is nowhere near as dramatic a landmark as the old red and white rocket ship blinking its white light out into the strait (as well as into many of the houses in the neighbourhood). The new light flashes red and is much less intrusive. Its blocky silhouette with the solar panels and battery look a bit like a cheerful robot holding its hands out in greeting to the passing boats. We’ve decided to name it Brent after a dearly loved red-headed friend who died suddenly just a month before it was installed. A sturdy, stalwart beacon of light. Shine on, Brent.

November 10, 2024

Telephone of the Wind

In 2010, Japanese garden designer Itaru Sasaki placed an old phone booth in his garden and installed an unconnected rotary phone. He’d go out to talk to his cousin who had died of cancer the year before. He called it The Telephone of the Wind. The next year, he made it available to the thousands of people who never had a chance to say goodbye to loved ones they’d lost in the huge earthquake and tsunami of 2011. Over 1200 people were killed in his village alone, about 20,000 in total. His project struck a chord; since then, over 30,000 people have used his phone. Hundreds of wind phones, of every imaginable design, have been installed around the world. They are a way to say goodbye, to say you’re sorry, to offer forgiveness, to give good news, to share your grief.

qathet’s Telephone of the Wind was welcomed into the Cranberry Cemetery on Sunday, November 3, 2024. Tla’amin elder Les.Pet Doreen Point said a prayer to bless its installation on Tla’amin territory where it gives people another way of communicating with loved ones they have lost.

Ours is an old rotary phone (donated kindly by the PR Health-Care Auxiliary Economy Shop) sitting on a shelf built into a beautiful slab of local maple (donated by hospice volunteer Roger Langmaid). It stands on a stone donated by T & R Contracting. But most importantly it was Harvey Chometsky who designed and built the phone with Roger’s support. I got to help inset the spiral of beach pebbles above the phone, a spiral that changes from grey to white to signal the lightening of your spirit as your words are carried on the wind to the one you miss. Or that Harvey says draws a link between the earth and the spirit.

To give you a sense of how an unconnected phone might be a way to channel grief or honour the memory of someone you’ve lost, let me tell you a story.

In 1956, when I was three, my dad was able to come home from a Vancouver hospital where he’d been in rehabilitation after contracting polio just before I was born. We moved into the new house he’d begun building before he got sick and that others had helped finish. We also got a new phone number, one we children had to memorize in case we needed to call home. It followed us when we moved down to Grief Point a dozen years later. It was the number I always called to talk to my mother, and it stayed hers until she died last year. We still have that number on our landline. My cell phone lists it as Mom. When I think of all the times I dialed it over the years and all the stories we shared, it’s easy to feel the connection is still, in some way, there.

A couple of months ago, on our way to catch the ferry home, we received a phone message from Mom. My sister was staying at our house, so I assumed it was her. But when we played the message through the Bluetooth, my mom’s voice filled the car. “I don’t know why you would be calling me,” she began. We were stunned because Mom had been gone for almost a year. I remember hearing and deleting that message when we first received it. But there it was, a year later. We were more than a little shaken. It seemed especially poignant because we were in the midst of this wind phone project.

While it seems the first person I’d call would be my mom, I think it will be my dad, who died almost 55 years ago. If I could, I’d put the phone on speaker and introduce him to my husband, sons and grandson and tell him about all the things we’ve done over the years, not to mention the surprise of finding myself back here in the house he had built for my mom just a couple of years before he died. Standing in the cemetery where her ashes are buried, his name on her gravestone too.

Who would you call?

Harvey Chometsky building the telephone of the wind in his outdoor studio

Sheila, right, tells the story of this telephone of the wind.

Sheila, right, tells the story of this telephone of the wind. Roger lowers the stone from his van

Roger lowers the stone from his van

Thanks to the qathet Regional District Board of Directors and staff who gave us permission to install the phone and to Four Tides Hospice for their support.

August 1, 2024

Layers of life

The house next door is on the move.* Yes, really. Men set blocks and jacks, scramble inside, under, high on the roof, kicking aside the old moss where killdeer nested one summer. Like worker ants tending to the queen. They cut it into sections, raise it up on big blue beams laid at right angles, and swivel it around after rubbing Ivory soap between opposing beams. They tuck wheels underneath and pull it off the basement – the house organs exposed: furnace, water heater and copper pipes.

Ivory soap bars lubricate the turning of the house

Ivory soap bars lubricate the turning of the house

A hive of activity

A hive of activityLights festoon the massive bulk. Come midnight, it will glitter like Christmas. The 1980 Kenworth T800 with its blue stripes will rumble into life and pull it off the lot along the subdivision road to climb a hill so steep it’s marked with Do not enter signs. Small for a house, the driver says. 40 feet x 25. Only 30 tons. It will be accompanied like a royal procession.

About 375 horsepower and an auxiliary transmission. The Kenworth.

Our Vauxhall Victor was a lighter blue. Robin’s egg. Forty horsepower and three on the tree. It was eight years old when we moved into our new house down here at Grief Point in 1968. Learning to drive, we had to make it climb those same hills. Front tires hanging onto the rim of the cross road at the stop signs. Brake, clutch, brake, clutch. Heel and toe. Stall. Start again.

The Kenworth will have traffic stopped when it makes its midnight crossings, an advance crew to remove any unexpected obstacles.

The house next door used to be the same blue as the beams it now rests on. It wasn’t here when we moved down to the new subdivision. Just the tall grass growing on what had last been a market garden and a few houses scattered along the new road. Built by Frank and Bessie Bemrose in 1971, the blue house was a bright bungalow filled with glitter and glamour. Bessie’s grey-blue hair was bobbed short; her big beaded necklaces clicked and clanked in bright colours, sharp facets on her rings. Bracelets to her elbows. She’d been my Grade 3 teacher. Frank was a tonsured twinkler who sang O Holy Night every Christmas at our church, a revelation for this cynical non-believer. And what a gardener. Within a few years he’d grown a productive cherry tree, long gone now, and a wonderful apple tree. We made applesauce with its apples just last year, the final harvest. The tree was felled so Frank’s house, the old blue paint showing through the newer green layer flaking off, could be moved.

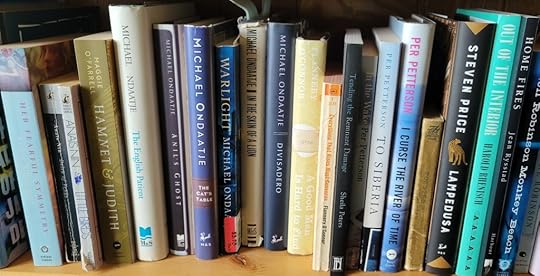

My brother Herb showing off his catch in front of Bemrose’s house in the early 70s. That pine tree is now enormous, but the fruit trees are gone. Lee and Mike Hill bought the house around 1985. They sold it to Fred and Terri Formosa in 2000 who subsequently rented it out until they were ready to build a new house there; hence, the move.

Harry Nickel was the first settler to occupy the point. His obituary was published in the Powell River News after his 1933 suicide.

He cultivated a number of acres of land at Grief Point, and also raised a number of sheep. His home is a famous spot on the coast. He was one of the first, if not the first white settler in this district, coming here over forty years ago. He took up a homestead at Grief Point, which has quite a history, of which little is known. It is said to be the site of a former Indian village, and that traces of Indian huts have been found.Mr. Nickel took up a homestead of 160 acres on the point, and later sold several parcels, retaining the point for his residence. He has lived practically alone as a bachelor, as far as can be learned. We understand he has left the estate to Mrs. Courte, who is another pioneer of this district, and the first white woman to reside here [supposedly she taught him English].

When Mr. Nickel first arrived, transportation was negligible, and he made occasional journeys to Vancouver for supplies in a canoe, which occupied several days. He left a number of trees on the place when he cleared part of the land. These, and some fruit trees he planted, are splendid specimens. Grief Point forms a shelter [on its north side] for tugs with booms of logs in stormy weather. On the beach there are clam shell deposits about 10 feet deep and several hundred yards long. Scow loads of these have been taken away several times.

Victor (VI) Courte bought the property from his parents in the mid-forties and lived there with his family for many years. In the early sixties he offered to sell it to the town for a park, but the taxpayers refused the asking price of $58,000. So a consortium of locals pooled their funds and created the subdivision, each member putting their names into a lottery to see what waterfront lot they’d receive. They also got a dividend as other lots were sold. Aside from my family, June Vogl is the only other original investor still living here.

The archaeologists are digging test pits around the excavation. They will find artifacts. Everyone who grew up in the older houses up the hill collected them over the years before and during the subdivision’s construction. Colonial artifacts too – old cars were, they say, buried in the gravel, which likely explains the dips in our oceanside lawn. Beach gravel was trucked out to facilitate various city building projects.

Layers upon layers. Local geologist Tom Kolezar says the point is a fluvial fan likely left over from a melting glacier 10,000 years ago. All of our homes rest on this unstable blend of sand and gravel, a deposit that slipped just offshore in the 1946 earthquake and severed the telephone cable to Van Anda. Apparently before Nickel planted his trees and gardens, cow parsnip, from which it received its Tla’amin or ʔayʔaǰuθəm name, xah kwoom, grew here in abundance. One source says it was an important camping site where the Tla’amin people also planted gardens.

The layers in the soil pits produced flaked stones and cultural soil, evidence of hundreds if not thousands of years of habitation. Like the abundance of clam shells referenced in Nickel’s obituary, they can only hint at the layers of meaning and memory that predate the houses in this subdivision. That predate the market gardens.

Grief Point is a vantage point where everything meets – the winds, the tides, the subterranean slips. The debris of our lives here will one day join the archeological evidence illustrating a tenure that, I suspect, will be much shorter than that of the Tla’amin. More like that of Bemrose’s house. Fleeting.

… a difficult manouever

… a difficult manouever

… raised on a new foundation

… raised on a new foundation

… farther from the water, but still a view

… farther from the water, but still a viewKudos to Steve Skorey of Bolder Contracting who arranged to have the house moved and the Belton crew for managing a difficult project – we wish the house well in its new home high above Cranberry where Steve is planning to turn it into a wilderness lodge.

*The house was moved in late May and early June.

April 22, 2024

Earth Day and poetry month – what’s not to like?

Donna Kane’s new book of poetry, Asterisms, (Harbour Publishing) is a beautiful collection that takes us out into the far reaches of the universe and close up to the pollen stuck to a bee’s feet “like grains of floor wax.” She investigates old adages like knocking on wood and explores the ramifications of bombing asteroids to see if we can deflect them. From a microscopic grain in her greenhouse to the vision of the James Webb Telescope at the Lagrange Point, she brings her keen eye and generous heart to make poems of amazing dexterity.

Virtually every poem is a love song to our world, though she’s not always so thrilled with what we’re doing to it. There’s humour and anger and worry here, but most of all love, the love that’s demonstrated by paying close attention to what our planet and the universe in which it exists offers.

To illustrate this, I’m sending all of you “Cleaning up before you Go” in honour of Earth Day.

Thanks, Donna.

January 16, 2024

Kilisët Violet Marie Gellenbeck

In 2017 Creekstone Press joined forces with a truth and reconciliation project already well underway. The book that became Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973, focused on the story of Indiantown, a small community on the edge of Smithers where Witsuwit’en families tried to make a place for themselves in spite of systemic racist opposition. In 2010s both Witsuwit’en and longtime settlers formed a working group to bring their stories to light and consult with the young geography professor who authored the book, a Smithers man who grew up in the subdivision built after the erasure of Indiantown. The consultation was thorough, demanding and fraught with difficulty. There were times I thought the book was never going to be finished. But it was, and we launched it with a march from Smithers to Witset (the closest Wet’suwet’en community) and a feast welcoming over 200 people from the settler community in September 2018.

Many good people shared their often painful stories and worked across cultural misunderstandings to bring this book to fruition. Witsuwit’en sisters Violet Gellenbeck and Charlotte Euverman were especially helpful to me as I struggled with the project’s complexity. It was heartbreaking to hear of Violet’s death on Jan. 4. Tyler McCreary, the geographer whose name is on the cover of Shared Histories, wrote this eulogy for her funeral held January 11 in Witset. In it he encapsulates her life’s joy and heartbreak, and her commitment to the long struggle to enable Indigenous people to live peaceably in their territories. The photograph below shows her welcoming the marchers to Witset.

On January 4, 2024, Violet Gellenbeck died peacefully in her home at the age of 86. A matriarch within the Wit’suwit’en community, she will be remembered for her dedication to the cause of Indigenous peoples. Over her life, she made countless contributions to advancing Indigenous concerns, including in Native education and employment services, Witsuwit’en language and cultural revitalization, protection of Indigenous women and girls, and defence of Witsuwit’en yintah.

Born on September 1, 1937, Violet descended from the proud lineage of Kwin Begh Yikh within the Likhsilyu. Her maternal grandmother, Mary Mooseskin, belonged to a chiefly family; Mary’s brothers Round Lake Tommy and Louie Tommy carried the name Ut’akhkw’its. Violet’s mother, Lucy Bazil-Verigin, took the name Gguhe’ at 12 years of age, and upheld that name through her life.

Violet was also born in a time of turbulence and change. Attempting to adapt of the lifestyles of the newcomers, her uncles had built a farm on Kwin Begh Yikh territories by Round Lake. However, settlers coveted the land and racist land policies in the period prioritized the rights of immigrants over Indigenous peoples. Displaced from those lands, Ut’akhkw’its Round Lake Tommy would establish another home at Johnson Lake, while Louie Tommy and his siblings Jack Joseph and Eva Isadore would become among the founders of the Indiantown community alongside Smithers. Violet’s grandmother Mary Mooseskin and grandfather Mooseskin Jim became part of a Witsuwit’en community on Buck Flats adjacent to Houston.

While the arrival of settlers had dramatic impacts on Kwin Begh Yikh, house members nonetheless sought to integrate into the emerging economy. Violet was born at Beamont, a camp in the Bulkley Canyon where Witsuwit’en workers cut poles for the railway. Her parents, Lucy and Frank Bazil, would move from Beamont to the community at Buck Flats, then Indiantown, and a series of rental houses around Smithers before eventually purchasing their own home on Railway Avenue.

While the Bazils lived on Witsuwit’en territories, and attended the balhats in Witset, they remained distinct from the reserve community during these years. In 1946, the family was enfranchised, taking away their Indian Status. Both Frank and Lucy had attended Lejac Indian Residential School and experienced the traumatic impacts of assimilationist government schooling. Conditions there were atrocious. Two of Frank’s siblings, Mary and Agnus, died in the residential schools. Enfranchised children were able to attend public schools, protecting them from conditions at residential schools, but it also meant that the family was no longer allowed to stay on reserve or access band services.

Violet was one of the first Witsuwit’en students to attend public school in the Bulkley Valley. Starting school in Houston and continuing at Muheim in Smithers, she developed a lifelong love of learning. She held fond memories of school. Education broadened her horizons and opened new possibilities for the future. Violet dreamed of being a nurse.

However, family circumstances intervened. The family did not have access to Indian health services, and medical debts had accumulated. The first of 14 children, Violet had to leave school to help support the family. Violet took a job at Sacred Heart Hospital in Smithers. She had reached Grade 7.

Sacred Heart Hospital would introduce Violet to the great love of her life, Werner Gellenbeck. Werner was born in 1933, the child of a miner in Gladbeck, Germany. He migrated to Canada in search of industrial work, which he found in Northern British Columbia. An accident brought him to the hospital. With an injured hand, he needed Violet’s help to cut up his food.

This chance encounter slowly developed into a love. It was, in many ways, an unexpected romance fostered with the unlikely assistance of the hospital priest, Father Godfrey. Werner, a recent German immigrant, did not speak English well. So, he wrote letters, in German, which Father Godfrey then translated to Violet, continually admonishing that he was not an appropriate man for her to date. Violet listened to the warmth of Werner’s words and ignored the old priest.

Dating Werner, Violet charted her own path. Her parents had been planning an arranged marriage to, in Violet’s words, an “old guy.” Always independent, Violet found her own love in the young Werner. In 1953, they moved to Prince Rupert together.

Prince Rupert were the happiest years of Violet’s life. She married Werner in 1955. They had three children in Prince Rupert: Bernie in 1956, Ingrid in 1958, and Gordon in 1962. Violet worked in the salmon canneries, Werner in the pulp mill. Initially, they lived in a two-room cabin, but over time they saved up money and bought a bigger, two-story, three-bedroom home. As a parent, she always emphasized the value of training and hard work, setting a model for her children.

In 1966, they took their first vacation, travelling south and visiting Bellingham, Vancouver, Victoria, and Port Alberni. They loved the island and decided to move, finding an old house in Ladysmith built in 1906. They lived there from 1966 until 1971.

On Vancouver Island, Violet returned to her long-delayed dream of education. In 1968 and 1969 she took the practical nursing program in Nanaimo and did a practicum at Duncan General Hospital. She then went on to work at Ladysmith Hospital in 1969 and Saltair Hospital in 1970.

In this period, Violet also began to get politically involved. In 1969, she began to attend meetings of the British Columbia Association of Non-Status Indians (BCANSI). Legal enfranchisement had deprived non-Status Indians of accessing rights under the Indian Act, including reserve residence and band services and funding. However, non-Status Indians continued to suffer from poverty and discrimination. BCANSI sought to improve access to education and employment, as well as fight discrimination in the Indian services. Violet participated in these campaigns and began public speaking on these issues.

In the fall of 1971, the Gellenbeck family relocated to Terrace. Violet continued organizing with BCANSI and also became involved with another Indigenous rights organization, the Union of Native Nations (UNN). She was a founder of the Kermode Indian Friendship Center in Terrace, serving as organization president for several years.

Living in the North, Violet was able to become more involved in traditional governance in the bahlats. Taking greater duties within the Kwin Begh Yikh, Violet took the name of Ghukelen in 1974. She was also connected to traditional foods, preserving salmon and making medicinal teas. A great cook, she intermixed Witsuwit’en and German dishes, making fantastic fusion foods.

Tragically, through these years, Werner struggled with addiction. This eventually led to his premature death in 1980. His loss was a sadness that Violet would carry through the rest of her life.

She channeled her love into work to improve the lives of others. She took a position with Canada Manpower in 1979, working as a Native employment specialist. In 1983, she took a promotion and relocated to Vancouver to expand the scope of her work. However, life in Vancouver was isolating; after three years, Violet took a demotion in order to move to Kelowna where she could be with her daughter Ingrid.

Following the organizing of BCANSI and UNN and other groups, the Canadian government revised the Indian Act, enabling disenfranchised families to regain their status. In 1986, Violet got her status back. This allowed her to live and work on reserve. Subsequently, she decided to move to Witset in 1988.

She took a position as Moricetown Band Manager. Violet wanted to bring the knowledge that she gained working for Canada Manpower to support the Witsuwit’en community. While she was a strong leader with passion for the role, it was not the right time in the community for her style of leadership and she left the band office. Later she took a position with the Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en Government Commission, directing economic development initiatives for the eight member bands.

She remained an active member of the Witset community. She was a consistent defender of band members, particularly vulnerable women and children, helping ensure that the community was a safe space.

Simultaneously, she was involved in major Aboriginal title litigation that would transform Canadian and international conversations about Indigenous rights. Through the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Witsuwit’en hereditary chiefs, alongside their Gitxsan neighbors, took the government to court claiming unceded ownership and jurisdiction over their traditional territories. The case was known as Delgamuukw, Gisday’wa, named after the lead Gitxsan and Witsuwit’en plaintiffs. Delgamuukw, Gisday’wa advanced the hereditary chiefs’ claims on the basis of Indigenous legal traditions.

In the case, hereditary chiefs took the stand as experts on their own legal traditions. Violet’s mother, Gguhe’ Lucy Bazil, was one of the Witsuwit’en witnesses and Violet played a vital role in supporting her. The Delgamuukw, Gisday’wa case radically transformed Aboriginal policy in Canada and led to modern treaty negotiations.

In 1993, the Gitxsan and Witsuwit’en hereditary chiefs split into two organizations to negotiate their respective claims. Violet served as Executive Director of the Office of Wet’suwet’en, working closely with and taking guidance from hereditary chiefs such as Gisdaywa Alfred Joseph, and Wigetimschol Dan Michel, and Sats’an Herb George. Later she would serve as chairperson of treaty negotiations for four years.

The treaty negotiation process stalled due to a government treaty framework that aimed to force Indigenous peoples to abandon their responsibilities for the majority of their territories. The Witsuwit’en hereditary chiefs were adamant that reconciliation was not just about money. It required negotiating a shared land management process that recognized the chiefs’ responsibilities in stewarding the yintah.

Stepping back from the treaty process, Violet focused on caring for her aging mother, Gguhe’ Lucy Bazil-Verigin, and helping preserve her knowledge and teachings for future generations. She remained active in traditional governance through the bahlats. After the passing of her mother’s cousin Eva Isadore, Violet took her name, Kilisët, in 1990. She carried that name with honour. She also supported others. A skilled seamstress, she made regalia for other chiefs, including Lho’imggin Alphonse Gagnon and Wigidimst’ol Dan Michel. She preserved traditional medicines and continued to learn new skills, like Tlingit weaving.

Although Kilisët retired from the workforce, she never stopped contributing to the community. She was an active researcher collaborating in numerous projects. She helped establish the Witsuwit’en Culture and Language Society, working with the Bulkley Valley School District to create Witsuwit’en curriculum. She collaborated with anthropologist Melanie Morin in the creation of Niwhts’ide’nï Hibi’it’ën: The Ways of Our Ancestors, a textbook introducing students to Witsuwit’en people and their history. She guided geographer Tyler McCreary in his research for Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973, a book that acknowledged the history of Witsuwit’en families in Indiantown. She worked with linguist Sharon Hargus to publish Witsuwit’en Hibikinic, a Witsuwit’en-English dictionary.

Kilisët continued working on Witsuwit’en language and cultural revitalization projects until her final days. For the last year and half of her life, Kilisët advised UBC PhD student, Sarah Panofsky, on the project “Ts’ienï Kwin Ghinen Dïlh (Everyone Coming Back Home to the Fireside).” In the project, she guided and mentored a research circle of Witsuwit’en hereditary chiefs, frontline workers, and social service leaders. “Ts’ienï Kwin Ghinen Dïlh” renews and develops distinctly Witsuwit’en approaches to caring for vulnerable children and families, helping facilitate the exercise of Witsuwit’en jurisdiction over child welfare. She also sought to reintegrate families disrupted by the intergenerational effects of residential schools and the foster care system. She described the work as dedicated to “those people, children growing up that are lost out there, just to bring them back to the point of knowing who they are.”

Kilisët was a consistent and powerful voice for Witsuwit’en and other Indigenous peoples. She had friends across the Northwest, including among the Carrier Sekani, Gitxsan, Haida, Nisga’a, Tsimshian, and Tlingit. She also worked to build bridges with the settler community, sharing Witsuwit’en traditions with them and always eagerly learning lessons about the different cultures of immigrants to the yintah.

Through her life, Kilisët was an advocate for those at the margins, such as the unemployed, women, and children. The legacy she leaves us is one of deep commitment to upholding Witsuwit’en traditions and laws. She was persistent, some might even say stubborn. She fought for things to happen in the right way, according to inuk’ niwh i’t’en. But her actions were guided by her love and respect to each person’s fundamental human dignity. Let us grieve her loss but also never forget her. Let us use her life as a lesson for how we conduct ourselves. Violet always said it best. Let her words be a message to guide us into the future.

Today as we work together, we’re not making things up new to teach our people. What we’re doing today is we’re following the knowledge passed down to us from our ancestors and we’re making it stronger so that our Nation becomes stronger.

Let’s come back together because this work that we’re doing is very important. It’s not for us, it’s not for us to use in the future. But it’s for our children, for our children’s children—your grandchildren, their children—your great grandchildren, and those babies not yet born, that’s who you’re working for. That’s who you are going to leave the yintah to.

January 12, 2024

A lesson in creative resilience: Knots and Stitches by Kristin Miller

Salt Lakes was a place I always wanted to visit over the years our family enjoyed visiting friends in Prince Rupert. We’ve been to Dodge Cove, CBC Hill and many of the other places Kristin brings to live in her memoir, and now feels as if I’ve been to Salt Lakes too. Below is a review of Kristin’s book I wrote for qathet Living.

Kristin will be showing slides of the people, quilts and boats as she tells the story of Knots and Stitches at the Powell River Public Library on January 20 from 2-3 pm. Books will be available there and can also be purchased at Pocket Books on Marine or through Chapters and Amazon.

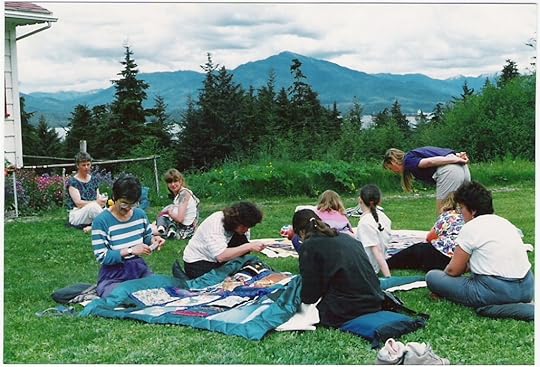

Quilting Day on CBC hill across the harbour from Prince Rupert. Kristin is in the striped shirt on the left.

A 45-year friendship brought Kristin Miller to Powell River in 2017. She was looking for a place to land after a long-term relationship ended, and her friend’s offer to split the purchase of a Wildwood home was a “perfect solution.”

Her new book, Knots and Stitches: Community Quilts Across the Harbour, loops back to and in some ways echoes the beginning of that friendship. Kristin had been working as an occupational therapist in Nanaimo when she took up quilting. She found she enjoyed it and brought quilting with her when she moved to Prince Rupert to join a boyfriend, soon to be husband, in 1979. A chance encounter led them to Salt Lakes, a tiny community across the harbour where they bought a ramshackle cabin for $3500.

“We kept our tiny apartment in Rupert and played house at Salt Lakes, spending romantic candlelit evenings at the cabin, then going back to our real life in town. We imagined settling down in this slipshod paradise, but as it turned out, I ended up living there alone.”

After much trying, Kristin got pregnant, but nearly died from the complications of an abdominal pregnancy. After surgery, she was told she’d be unlikely to have children, information that completely changed the image she had of herself. Her faltering relationship and deep feelings of loss led her to move alone to the cabin. “I wanted to get away from everything,” she said.

Get away she did, to a leaky cabin without plumbing or electricity, accessible only by water. And the waters of Prince Rupert harbour can get very treacherous. Learning the boating skills needed to make that crossing and doing the chores necessary to stay warm and dry consumed much of her emotional and physical energy. The knowledge she needed came, in part, from the other women who lived there.

“Lorrie, Linda, and Margo were my three friends at Salt Lakes and were tremendous friends to each other. Their cabins stood three in a row, directly opposite mine, on the far side of the cove.” The most important kind of support they gave, she said, was by treating her as normal, not a tragedy.

Lorrie, Linda, and Margo’s cabins, on a wintry day at Salt Lakes in 1987. Kristin’s skiff is tied to the dock.

As she slowly healed, some of the women asked her for help finishing a baby quilt. They weren’t sure how to connect the individual squares, which were not all the same size. Kristin’s relaxed approach gave them the confidence to sew strips around the smaller squares and fit them together in whatever way seemed to work. She then showed them how to make “pass-the-medallion” quilts: one woman made a central panel and subsequent borders were attached by other quilters. There were no rules and the quilts became more and more creative, sometimes with applique and three-dimensional forms added. “They were all beautiful,” Kristin said. Often made from whatever materials were at hand in some of the women’s more remote locations, the very fabric of the quilts spoke to their makers’ creativity and resilience.

Over the next years, many women joined in to make dozens of quilts. Quilts for babies, quilts for weddings, and, as the women aged, quilts to comfort those who were ill and the families of those who had died.

“These robust, vigorous women might not fit the stereotype of the dainty, ladylike quilter, but their quilts embodied warmth, love and caring in a practical as well as symbolic way,” she writes.

Kristin began recording their stories as part of a project to display and document the work they had done. A visitor to their quilting show at the Prince Rupert Museum in 1992 invited Kristin to write a research paper, which she presented at an international conference in 1993. “If you’re writing about the quilts, you have to write about the quilters.”

Mia, who was given her own baby quilt in 1986, is delighted to receive a baby quilt for her son Levi in 2019.

“I thought about turning it into a book back then and ended up with fifteen or twenty so-called chapters. But the project became so big with about 100 quilts and a 100 people involved, I stowed it in a box. But when I reread those chapters a couple of years ago, I thought they were really good and decided to take up the project again.”

And they are good. The characters, the adventures, the feasts, the parties, all come to vivid life in her book. Anecdotes about some of her dating adventures are equally entertaining. But throughout she writes respectfully of the relationships she and others had. “That was one of the guiding principles of my writing; Don’t write anything hurtful,” she said. And she found she wanted to tell the story of her own pain and loss at not having children of her own. “I think I needed to do that,” she said.

That decision makes Knots and Stitches a candid memoir as well as an important addition to the history of the north coast. These adventurous women lived precariously in the tiny communities spread across the small islands out beyond Prince Rupert’s harbour. Like Kristin, they found themselves teaching each other how to survive and thrive in the challenging marine environment with its big tides and big weather. But as they aged and their families grew, most of them left those rigors behind and moved south, many to the gentler southern coast.

Most of these women are still linked and are still making quilts together. Kristin certainly hasn’t slowed down, especially after she progressed from the treadle sewing machine and wood-stove-heated flatirons of her Salt Lakes days. “I’ve made at least 500 big quilts of my own,” she said.

The friendships connect her still. She shares a house with Lorrie, her old friend from Salt Lakes. They have brought the warmth and connections formed all those years ago and are now stitching themselves into our community.

Kristin, (left) Jane Wilde and Lorrie Thompson still quilting together.

November 26, 2023

Disposition of the Dead*

I first came to this topic because Lynn and I were trying to decide what to do. We’d always thought we’d be cremated, but green burials seemed like a good idea and if I’m honest, it was the lovely basket coffin with its cotton bedding we saw on a hospice tour of Stubberfields Funeral Home that really attracted me. So tasteful. So comfortable.

And the Cranberry cemetery is beautiful. A little sedate – not much room for flair – but peaceful and sunny. If we were cremated, we could also go to the Kelly Creek cemetery. It is lovely and crazy. But do our kids want to do something zany to remember us by? It’s not really their style. We’ll have to take them there and see what they think.

The Holy Cross Cemetery on Nassichuk Road in Kelly Creek

The Holy Cross Cemetery on Nassichuk Road in Kelly CreekWhile researching this, my mother, who was 99 and in good health, suddenly declined and we were, while mourning her death, busy putting into action her wishes about cremation, burial, and funeral. It brought back lots of memories, or their lack.

When my dad died in 1970, it was very sudden – post-polio syndrome. He was right upstairs when my mom came down to tell us, but I didn’t go to see him. I don’t know why. My brother remembers going. I was in a very strange place. Friends came by and what I mostly remember is I wasn’t wearing my usual mascara and eyeliner. Of course, no one noticed, but I stopped wearing it after that. It seemed pointless. Went back to school within a day or two.

Dad wasn’t cremated until his parents were able to get here from Saskatchewan. They wanted to see him. I think they asked me if I wanted to go with them to the funeral home, but I didn’t. Was he in the church for the funeral? I don’t remember. As I said, I was in a strange sixteen-year-old frame of mind.

I must have had some notion that cremation meant the body disappeared – that there was nothing left. There was no talk of ashes, of burying them or of spreading them. I didn’t think much about it until years later. I asked Mom. She’d left them at the funeral home. He was gone, she said. The ashes held no significance for her. After that Stubberfields tour, I asked the director Patrick Gisle what he did with ashes left behind. I actually wondered if they could still be there, fifty years later. He told me it happens regularly and he has a few quiet places he spreads them.

I suspect Dad’s parents would have liked to bury them in the lovely little prairie cemetery where they’re now buried. There’s something beautiful about the expanse of land and that big prairie sky. Dad might have liked it too. He was at heart, I think, a prairie man. My friend Margaret’s family has a private graveyard in Manitoba, near what’s left of the family farm. On her regular trips to the small town where her brother David lived until his death a couple of years ago, she tends to the graves, which go back at least four generations. She has a deep sense of attachment to the place and its history. She’s thinking she’ll have her ashes buried there.

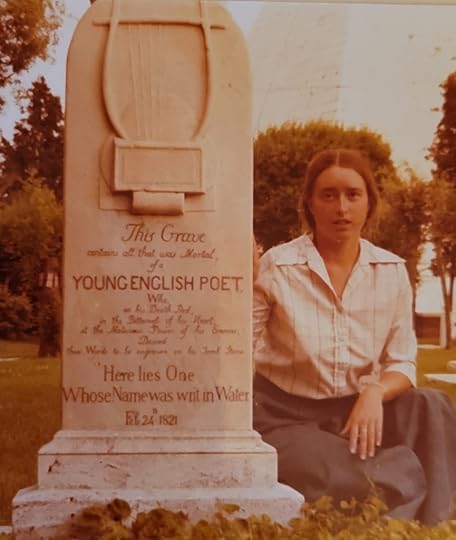

Cemeteries give a kind of permanence to the disposition. They form part of the historical record and can become places of both private and more public pilgrimages. I remember visiting, in 1977, the grave of the poet John Keats in the Protestant cemetery in Rome just after going to the rooms beside the Spanish Steps where he died of TB in 1821. He was 25, a year older than I was then. I’d been reading his letters. His friend, painter Joseph Severn, described his death: In the afternoon he uttered his last words ‘Severn-I–lift me up–I am dying–I shall die easy–don’t be frightened–be firm, and thank God it has come!’ That night he expired, ‘so quiet’ that Severn still thought he slept. I found myself in tears – so moved by his youth and his generous heart. His epitaph broke my heart: Here lies one whose name is writ in water.

Although tombs can become the focal points of terrible conflict, visiting the graves of celebrated figures connects us to our cultural and religious communities, whether it’s Jim Morrison in Paris or the Taj Mahal in Agra. On a local level, participating in the cremation, the interment of the body or the spreading of ashes connects us on a more intimate level to our family and friends.

The past fifty years, at least in North America and Europe, have seen the creation of rituals to replace the Christian traditions many of us have left behind. Children decorate their grandparents’ coffins, ashes are turned into jewelry or sculpture, spread from helicopters (or in the case of Hunter S. Thompson, shot out of a cannon). Notes are tucked into urns, shrouds are woven by the intended user and proudly displayed, coffins are built in distinctive shapes; a popular example can be used as a bookcase until it’s needed for burial.

To reduce both financial and environmental expenses, Community Supported Dying qathet lends out a handmade and decorated coffin to transport an enshrouded body to its burial site at the Cranberry Cemetery.

Borrowing a Tibetan tradition, we started hanging prayer flags after a trip to Nepal, liking the idea of the wind carrying prayers out into the world, helping us all in the work of practicing compassion, of relieving suffering. The spot we chose on our property near Smithers funneled the wind blowing through from one mountain range down the canyon of the creek we lived beside into the watershed of the Wedzin Kwa and on to the great Skeena passage. I sewed together my mother-in-law’s beautiful hankies in her memory; we made flags out of old linen napkins with poems and blessings written on them. We spread ashes among the willows and aspens facing into the sunniest opening in the canyon walls. We created our own sacred place.

But then we moved. It’s on someone else’s property now.

We hung prayer flags from the lighthouse beside our house at Grief Point, or χakʷum by its ʔayʔaǰuθəm name, but it doesn’t have the same sense of private pilgrimage. The land was alienated in the 1890s and our subdivision was built in the 1960s. Tla’amin artifacts were found during the extensive excavation work, underscoring the ways in which precious places can be overrun, lost.

Cemeteries are perhaps an attempt to keep that sense at bay. My grandma, aunt and soon my mom’s ashes will be buried in Cranberry. My sister has reserved a plot there too. I suspect in one form or another Lynn and I will end up there. Still not sure what form that might take.

Mom and I visited the Cranberry Cemetery just a month before she died.This piece came out of research done for an article by the same name published in qathet Living for its Memento Mori issue in November 2023 and a gathering I led for one of the qathet Art Centre‘s Memento Mori events November 15, 2023.

Mom and I visited the Cranberry Cemetery just a month before she died.This piece came out of research done for an article by the same name published in qathet Living for its Memento Mori issue in November 2023 and a gathering I led for one of the qathet Art Centre‘s Memento Mori events November 15, 2023.

November 16, 2023

Knitting socks

I was in the kitchen I think, when Mom walked in with her old knitting bag. She pulled out a ball of variegated sock yarn and behind that, three needles carrying a tangle of stitches. The fourth needle dangled from their midst. It was heartbreaking. After she couldn’t read anymore, she could still knit. And she did. Socks for her grandsons. But now she couldn’t, not even the socks she’d been knitting for decades. Stitches dropped, yarn carried across the gaps, needles turned so the most important part of a sock, the hole into which you place your foot, was gone. I almost cried. There was so little left.

Just a few months earlier, she was still able to knit if I was nearby. She knew when something went wrong. She knew, but couldn’t see what it was or figure out what to do. I’d take it from her, fix it up and hand it back. Watch for a moment to see she was back on track. Together, we’d also been able to finish a huge blanket she made for one of her grandsons, Chris. She gave it to him just a couple of months before she died. We had so much knitting fun over the years, visiting wool shops, sitting together knitting, talking about patterns.

I just read an Ann Patchett essay, How Knitting Saved My Life. Twice, in which she describes how she’d come back to knitting when travelling in Ireland. When she made a mistake, she’d hand her knitting to any woman who happened to be nearby and ask for help. They could always fix it, she said, and if they had time they’d teach her how to fix it. I remember Lynn, when he was learning and I wasn’t nearby, going into yarn shops and asking for help. Always freely given.

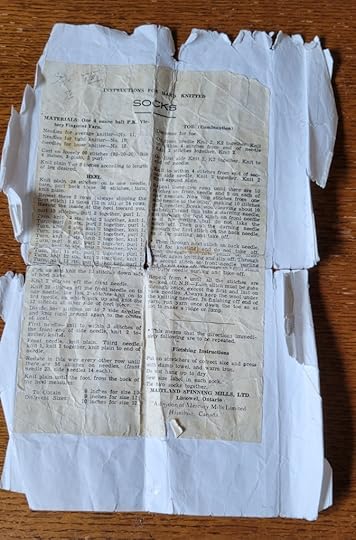

It wasn’t until I was going through Mom’s belongings after she died in September that I came across her sock pattern. She never referred to unless it was time to turn the heel. Over the years, how many times did I hear that phrase, just wait until I’ve turned the heel? It required concentration and careful counting. My heart broke all over again to see the raggedness of the paper onto which the pattern had been glued how many years ago? The pattern calls for P.K. Victory Fingering Yarn and must have dated back to the 1940s, when girls knit socks for soldiers. It refers to Maitland Spinning Mills, Ltd. Listowel, Ontario. A division of Mercury Milled Limited. Hamilton, Canada. She’d likely have knit a few socks back then, for she knew men who were overseas fighting. One, Leslie McLean, whose letters I found in a box tucked away in a drawer in her bedside table, was killed in action in 1944.

Mom, Leslie McLean, Hilda Nuttall, and Frank Dickson, 1942

Mom, Leslie McLean, Hilda Nuttall, and Frank Dickson, 1942I don’t recall her knitting much when I was a kid. My grandma did, and she could make the needles clack, she was so fast. The socks just whizzed off her needles. I tried using her old steel needles and the knitting belt an admirer made for her, but was never fast enough to make them sing.

When Mom lived on Vancouver Island in the late 1940s, she and her best friend Flo rode their bikes from Victoria to Powell River. Did they ride them back too? Did they take a Union Steamship across? I never did get the story straight. But for the next 70 years they visited back and forth and exchanged patterns and wool and went out for a Dairy Queen Blizzard whenever they were together.

But just as she lost her sight, she’d lost many of those memories unless you found the right questions to ask. Always tricky, that. Finding the right questions. And now we’ve lost her too.

It’s hard remembering her walking into the kitchen that morning, wanting to knit, and not being able to help her. I feel now, I should have let her knit up that tangle, fixed it as best I could and let it grow and grow. Since I can’t do that, I’ve taken up the wool and the needles a friend gave to her a couple of years ago, and am knitting up the socks, following the old pattern. These are for her great-grandson.

October 30, 2023

A year of losses

The past few months have been difficult. We’ve lost close friends, all of them much too soon. And during those months, we were also slowly losing my mother. At 99, it wasn’t unexpected. She didn’t have dementia exactly, but she was getting confused and seemed to be spending more and more time deep inside herself. It is, I’ve been told, a characteristic of people who will soon leave.

And leave us she did. One Monday morning in September, she woke up as usual, ate breakfast, walked to the park just down the road, and continued her typical day. When she woke up the next morning, she didn’t want breakfast. Then she didn’t want lunch or her usual rye and water. Or dinner. And that was that. Ten days later, September 23, resting in her bedroom of over 50 years with my sister nearby, she quietly stopped breathing.

As we sort through the markers of her long life – letters, photographs, jewellery, clothes, books – I keep thinking about her. About our lives together and apart. About the last four and half years when we shared a home. Remembering, wondering, and mourning. Feelings I want to write about and will, but first I want to give you a sense of her by sharing the eulogy my husband, Lynn Shervill, wrote for her funeral.

Born on the Shetland Islands north of Scotland in 1924, Elizabeth Malcomson Berger (nee Anderson), or the blonde Viking as her second husband called her, emigrated to Canada with her parents in 1929. The family was sponsored by former North Island MLA Mike Manson and spent their first months in a tent on Hernando Island before moving to Westview. That was 95 years ago, back in the days of the Union steamships. Today, Betty is gone, just shy of her 100th birthday. But her family continues to receive reminders of the impact she had as a teacher on students in her beloved community.

For instance, when Stubberfield funeral home director Patrick Gisle was notified of Betty’s death, his immediate response was ”She was my Grade 1 teacher.” Another time, as Betty and I were leaving the hospital, an ambulance attendant walked up to her and said “JC Hill was the best school I ever went to and it was because of you.” When one of Betty’s care aides arrived at the house a few weeks ago she told us Betty had been her principal at JC Hill. One of her former students, Mike Slade, along with his wife Ulie, was a regular dinner companion. Such was Betty’s career she sometimes taught three generations of students from the same family.

Hundreds, probably thousands, of Powell River young people benefited from Betty’s 40-plus years as a teacher mostly at JP Dallos and JC Hill schools here in Powell River. This would not be surprising but for the fact she had always expected to settle into the traditional role of housewife for her first husband, Saskatchewan farm-boy Herb Peters, and their three children, Susan, Herb Jr. and Sheila. But it was not to be. Herb Sr, fell victim to polio in 1953 and, while he was able to live at home, he was unable to return to work and needed lots of physical assistance. Betty went back to teaching in order to support the family and somehow managed to earn a Bachelor of Education degree through summer school sessions at UBC and be promoted to principal at JC Hill.

Her family were an ever-present support to her and Herb over these years, arranging for the completion of the house Herb had been building on Quebec Street when he got sick, helping sell their little house on Butedale, taking care of the kids when Betty went back to work. Her mother, Kate, kept house for the family on and off over those years and even welcomed the whole bunch of them back into her home when they sold their Quebec Street house in order to build the beautiful waterfront home at Grief Point, a place Betty adored in spite of her father’s warning about building “in yon windy hole.”

Only two years later, Herb’s ability to breathe was severely compromised by post-polio syndrome and he died in his sleep just hours before they were to leave for Vancouver to seek medical advice.

While missing him greatly (she had two teenagers still living at home!), she kept her sense of adventure. Her mother, Kate, was a passionate fan of Robert Service. In 1969 Kate, Betty, 17-year-old Herb and 16-year-old Sheila set out in their 1968 Acadian for Dawson City, 3200 km away, half of it on gravel roads, with communities about 200 miles apart. After a stop in Barkerville to stoke the goldrush fever, they continued north. Herb Sr. must have been watching over them because, although they carried no more than a few snacks assuming they could stop at restaurants along the way, they never went hungry and always found a hotel room. The car did well and Sheila remembers only one flat tire along the way, though they met many people along the Alaska Highway, waiting days for car parts.

Betty survived a couple of years as a single mom of two teenagers still at home before they left for university. A year or two later, a local mill worker and avid reader by the name of Albert Berger came into her life. She wasn’t interested at first, but he was persistent and finally, instead of closing the door on him as he stood in the howling wind on her porch, she invited him in. Albert brought his two adult children, Alison and Lawrence, into the family along with a lot of humour and adventure. They had thirty wonderful years together. He and Betty played bridge, danced at the Beach Gardens, and were members of the Myrtle Point Golf Club. But their favourite activity was frequenting casinos in Las Vegas and Reno. Betty especially liked watching the musical headliners in Vegas and Albert, with his betting systems, was a star at the Craps table. He was such a good gambler that Betty didn’t have to get any cash from her bank for a year after Albert died, she kept finding money in pockets, envelopes, drawers and cupboards as she sorted through his belongings.

Another of Betty’s passions was swimming in the ocean, something she as a child in Shetland and did right up until last year when she went for a dip with Sheila. A couple of years earlier, she tried to talk Alison into joining her. Alison is not a fan of cold water and believes something scary is going to rise from the ocean deeps to get her. “Alison,” Betty said, “There’s nothing to worry about” and dove in, swimming right into a big jellyfish. She flew out of the water with stinging welts over her face and neck. As Alison tended to her, we know she was feeling at least a modicum of vindication.

One of Betty’s favourite pastimes was bridge. She played with both Herb Sr. and Albert and continued on even after Albert’s passing. She admitted she wasn’t a very good player but never, until about two years ago, missed a Friday afternoon game at the home of neighbour June Vogl. Her eyesight was failing and she had trouble hearing. As the months ticked by she was easily disoriented and had memory problems. But up until a month ago she would still sit at the breakfast table and help us with the New York Times crossword puzzle and Wordle, using our verbal clues to divine the correct answers.

Betty was the middle child of five. Her four siblings, two sisters and two brothers, all pre-deceased her but she was able to connect and say goodbye to her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren in the weeks before she died. She was loved by all and we will carry her in our hearts forever.