Layers of life

The house next door is on the move.* Yes, really. Men set blocks and jacks, scramble inside, under, high on the roof, kicking aside the old moss where killdeer nested one summer. Like worker ants tending to the queen. They cut it into sections, raise it up on big blue beams laid at right angles, and swivel it around after rubbing Ivory soap between opposing beams. They tuck wheels underneath and pull it off the basement – the house organs exposed: furnace, water heater and copper pipes.

Ivory soap bars lubricate the turning of the house

Ivory soap bars lubricate the turning of the house

A hive of activity

A hive of activityLights festoon the massive bulk. Come midnight, it will glitter like Christmas. The 1980 Kenworth T800 with its blue stripes will rumble into life and pull it off the lot along the subdivision road to climb a hill so steep it’s marked with Do not enter signs. Small for a house, the driver says. 40 feet x 25. Only 30 tons. It will be accompanied like a royal procession.

About 375 horsepower and an auxiliary transmission. The Kenworth.

Our Vauxhall Victor was a lighter blue. Robin’s egg. Forty horsepower and three on the tree. It was eight years old when we moved into our new house down here at Grief Point in 1968. Learning to drive, we had to make it climb those same hills. Front tires hanging onto the rim of the cross road at the stop signs. Brake, clutch, brake, clutch. Heel and toe. Stall. Start again.

The Kenworth will have traffic stopped when it makes its midnight crossings, an advance crew to remove any unexpected obstacles.

The house next door used to be the same blue as the beams it now rests on. It wasn’t here when we moved down to the new subdivision. Just the tall grass growing on what had last been a market garden and a few houses scattered along the new road. Built by Frank and Bessie Bemrose in 1971, the blue house was a bright bungalow filled with glitter and glamour. Bessie’s grey-blue hair was bobbed short; her big beaded necklaces clicked and clanked in bright colours, sharp facets on her rings. Bracelets to her elbows. She’d been my Grade 3 teacher. Frank was a tonsured twinkler who sang O Holy Night every Christmas at our church, a revelation for this cynical non-believer. And what a gardener. Within a few years he’d grown a productive cherry tree, long gone now, and a wonderful apple tree. We made applesauce with its apples just last year, the final harvest. The tree was felled so Frank’s house, the old blue paint showing through the newer green layer flaking off, could be moved.

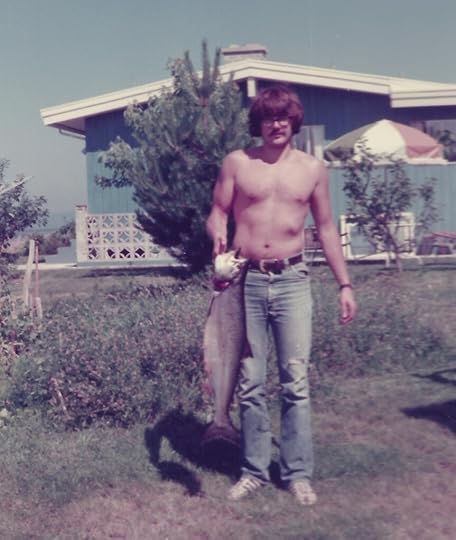

My brother Herb showing off his catch in front of Bemrose’s house in the early 70s. That pine tree is now enormous, but the fruit trees are gone. Lee and Mike Hill bought the house around 1985. They sold it to Fred and Terri Formosa in 2000 who subsequently rented it out until they were ready to build a new house there; hence, the move.

Harry Nickel was the first settler to occupy the point. His obituary was published in the Powell River News after his 1933 suicide.

He cultivated a number of acres of land at Grief Point, and also raised a number of sheep. His home is a famous spot on the coast. He was one of the first, if not the first white settler in this district, coming here over forty years ago. He took up a homestead at Grief Point, which has quite a history, of which little is known. It is said to be the site of a former Indian village, and that traces of Indian huts have been found.Mr. Nickel took up a homestead of 160 acres on the point, and later sold several parcels, retaining the point for his residence. He has lived practically alone as a bachelor, as far as can be learned. We understand he has left the estate to Mrs. Courte, who is another pioneer of this district, and the first white woman to reside here [supposedly she taught him English].

When Mr. Nickel first arrived, transportation was negligible, and he made occasional journeys to Vancouver for supplies in a canoe, which occupied several days. He left a number of trees on the place when he cleared part of the land. These, and some fruit trees he planted, are splendid specimens. Grief Point forms a shelter [on its north side] for tugs with booms of logs in stormy weather. On the beach there are clam shell deposits about 10 feet deep and several hundred yards long. Scow loads of these have been taken away several times.

Victor (VI) Courte bought the property from his parents in the mid-forties and lived there with his family for many years. In the early sixties he offered to sell it to the town for a park, but the taxpayers refused the asking price of $58,000. So a consortium of locals pooled their funds and created the subdivision, each member putting their names into a lottery to see what waterfront lot they’d receive. They also got a dividend as other lots were sold. Aside from my family, June Vogl is the only other original investor still living here.

The archaeologists are digging test pits around the excavation. They will find artifacts. Everyone who grew up in the older houses up the hill collected them over the years before and during the subdivision’s construction. Colonial artifacts too – old cars were, they say, buried in the gravel, which likely explains the dips in our oceanside lawn. Beach gravel was trucked out to facilitate various city building projects.

Layers upon layers. Local geologist Tom Kolezar says the point is a fluvial fan likely left over from a melting glacier 10,000 years ago. All of our homes rest on this unstable blend of sand and gravel, a deposit that slipped just offshore in the 1946 earthquake and severed the telephone cable to Van Anda. Apparently before Nickel planted his trees and gardens, cow parsnip, from which it received its Tla’amin or ʔayʔaǰuθəm name, xah kwoom, grew here in abundance. One source says it was an important camping site where the Tla’amin people also planted gardens.

The layers in the soil pits produced flaked stones and cultural soil, evidence of hundreds if not thousands of years of habitation. Like the abundance of clam shells referenced in Nickel’s obituary, they can only hint at the layers of meaning and memory that predate the houses in this subdivision. That predate the market gardens.

Grief Point is a vantage point where everything meets – the winds, the tides, the subterranean slips. The debris of our lives here will one day join the archeological evidence illustrating a tenure that, I suspect, will be much shorter than that of the Tla’amin. More like that of Bemrose’s house. Fleeting.

… a difficult manouever

… a difficult manouever

… raised on a new foundation

… raised on a new foundation

… farther from the water, but still a view

… farther from the water, but still a viewKudos to Steve Skorey of Bolder Contracting who arranged to have the house moved and the Belton crew for managing a difficult project – we wish the house well in its new home high above Cranberry where Steve is planning to turn it into a wilderness lodge.

*The house was moved in late May and early June.