On reading, for Mother’s Day

My mother taught hundreds of children to read, her own favourite pastime, over her long career as a Grade One teacher. She instilled that love in all three of her children. Just yesterday I mentioned to a friend the oddity of meeting someone who didn’t read at all for pleasure. We looked at each other in amazement. “What do they do?” we both wondered.

Since Mom is no longer here to thank once again for encouraging me to bury my head in books as a child and for sending me books as gifts as an adult, I’m sharing some thoughts about reading and writing triggered by two wonderful writers. A friend introduced me to Helen Humphreys a couple of years ago. My sister sent me a poem by Marie Howe a few weeks ago. Thank you both!

They’re very different writers – Helen Humphreys is a Canadian poet and novelist with deep ties to England. The Frozen Thames strings together snapshots of events staged on the Thames River the forty times it froze solid between 1142 and 1895. It’s a unique and fascinating perspective on English history. She has also set several of her novels in WW II England: The Lost Garden (2002), Coventry (2008) and The Evening Chorus (2015). They shine with the kind of luminescence found in works by Michael Ondaatje and Anne Michaels.

Marie Howe, for a time the poet laureate of New York, was raised in a Catholic family, the oldest of nine children. Her poetry, too, is luminescent at times, but also glints with the sly wit of Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska. I loved her New and Selected Poems (which just won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry) and was taken by one poem in particular. In“Why the Novel is Necessary but Sometimes Hard to Read” Howe’s combination of humour and deep insight admits to the complexity reading novels presents. In the poem, she writes about how all the paraphernalia a novel requires – character, plot, setting – can be intimidating or just plain tedious:

You come upon the person the author put there

as if you’d been pushed into a room and told to watch the dancing—

—pushed into pantries, into basements, across moors, into

the great drawing rooms of great cities, into the small cold cabin or

to here—beside the small running river where a boy is weeping,

and no one comes . . .

and you have to watch without saying anything he can hear.

One by one the readers come and watch him weeping by the running river,

and he never knows

unless he too has heard the story where a boy feels himself all alone.

How many children have been comforted by books as the weeping boy might have been? Comforted by kind librarians, by thoughtful teachers like my mom, and by writers willing to put in the work to create the magic allowing them to enter those other worlds.

Helen Humphreys takes the connections a step further in this excerpt from The Lost Garden (2002) when the main character, gardener Gwen Davis, sits listening to a young Land Girl read To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf to a young Canadian soldier.

The book is the shared experience, the shared intimacy. There is Virginia Woolf, dipping her pen in ink, looking up from the page with Lily on the lawn, to the view out her window. Here am I, looking across the room to the summer dark beating against these mullioned panes. There is Jane reading the words aloud to a young soldier sitting beside her. It is a place we have all arrived at, this book. The characters fixed on the page. The author who is only ever writing the book, not gardening or walking or talking, and while the reader is reading, the author is always here, writing. The author is at one end of the experience of writing and the reader is at the other, and the book is the contract between you.

Humphreys goes on to say that, in order to write,

… all of life is kept back, all the petty demands of the day-to-day. The heart is a river, the act of writing is a moving water that holds the banks apart, keeps the muscle of words flexing so that the reader can be carried along by this movement. To be given the space and the chance to leave one’s earthly world Is there any great freedom than this?

I thank them all, those writers, for the ways in which they have opened up my life, offered not only insights into the lives of others, but also comfort in my own. And I thank their mothers and mine.

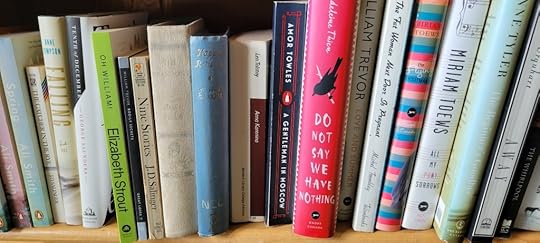

Elizabeth Hazlette photo

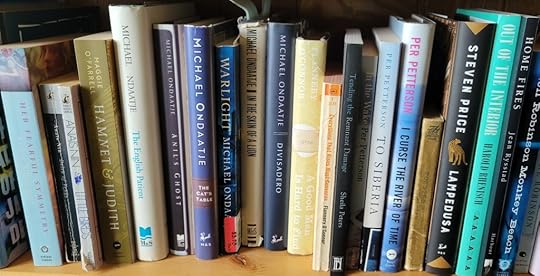

Elizabeth Hazlette photo