A one-year anniversary – let there be light

A new navigational beacon was installed at Grief Point Nov. 29, 2023 by the Marine Civil Infrastructure unit of the Canadian Coast Guard, 87 years after the first one was installed in 1936. There is, they tell me, no record of what precipitated its establishment, of what particular grief signaled the need for a light.

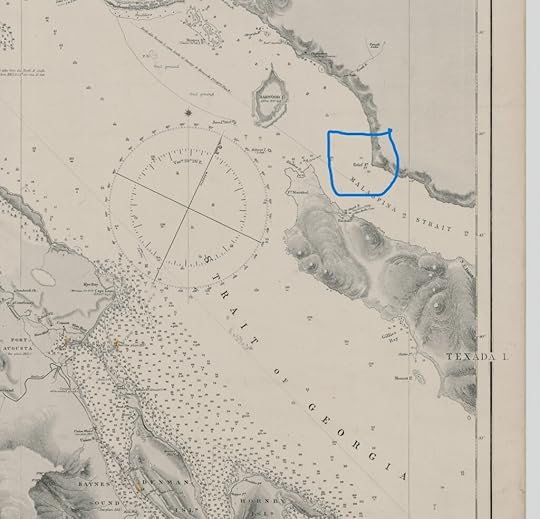

There is much speculation about why this rather innocuous point is so named. It’s a low shelf reaching out into Malaspina Strait, whose only danger to navigation is that an unwary boat might be pushed onto the shifting gravel that makes up its beach. Anyone shipwrecked could just walk a few feet up onto solid ground.

The BC Geographical Place Names database says the name was officially adopted in 1945 “based on British Admiralty Chart 580, 1862 et seq. Origin/significance not known.” The database also refers to historian Athelstan Harvey, who speculated that its name came because “it is an exposed spot in a westerly wind, causing grief to many a mariner.”

That may well be the case. Further correspondence with BC Geographical Place Names says, “The version of British Admiralty Chart 580 we have in our office is from 1860, with corrections in 1864, and has Grief Point labelled, so I think it’s safe to say the name existed by 1864.”

The men behind the early coastal mapping expeditions are named on the charts themselves and their work led to the establishment of the first beacons on the coast in the 1860s. Captain G. H. Richards, conducted the Vancouver Island Survey between1860 – 1862. Another name on the 1860’s chart was Pender.

In Boats, Bucksaws and Blisters by Bill Thompson (1990), Golden Stanley (GS) interviewed Roy Padgett (RP) in 1982 about Grief Point’s name:

“RP: When they were logging from Fiddlers, that road came straight down and the log dump was right where Gus Courte used to live … Well, apparently, when they dumped the logs in there, every so often they’d get caught with a westerly, and they’d get around the point [the logs would]and they got in the habit of saying there’s nothing but grief here,” and that’s the story I heard.

“GS: Well, it goes back further than that because … I think it was Pender who came up on the Trumpet to survey the coast at that time … and his log is lost, but the name goes back into the eighties [1880s] and from there on it’s called Grief Point. Before that, there’s no name on it. It was during his survey that the name became Grief Point. His log, apparently, went over to England and became lost. There’s no record of it …”

qathet Museum and Archives’ website also has notes on the naming.

“There is some speculation as to where the name Grief Point comes from. One possibility was that it refers to an epidemic within the indigenous population, another is of a wreck in which three men perished, while another is that it refers to the tugs and boats that would shelter behind the point during storms, to get away from the ‘grief’.”

Mom’s late friend, Fran Gregory, who used to live just above the point, painted five or six tugs lined up there with their boom stretched out behind them.

The museum site goes on to say, “At one point the area was also referred to as ‘Pneumonia Flats’ and referred to the flat area by the lighthouse in Grief Point. This area was a farm from the 1880’s and was sold in the middle 1960’s for a sub-division.”

Oddly enough, the references to the Tla’amin peoples’ use of the area talk about the protection it provided. Sliammon Life, Sliammon Land by Dorothy Kennedy & Randy Bouchard, states:

“The Sliammon name for Grief Point is Xákwuem, “having cow parsnip” referring to the abundance of “Indian rhubarb” (cow parsnip) that used to grow here. This was an important camping site because it afforded good protection from the southeast wind. In more recent years, before the area was developed, the Indian people planted gardens here.”

I’ve never understood the reference to protection. When my grandfather, who had lived many years in Shetland before bringing his family first to Hernando Island and then to Powell River, a man who undoubtedly knew something about wind, found out my mom and dad were planning to build a house in the new subdivision down at Grief Point, he exclaimed. “Surely you’re not going to build in yon windy hole!”

And windy it is. In rough weather we’ve seen tugs trying to round the point, sometimes looking as if they’re not moving at all. Other times, they actually start to slip back and end up executing a rather perilous looking turn to head into the shelter below Penticton Avenue.

The new lighthouse is the third one we’ve seen since my family moved down to the new subdivision in 1968. I think, from the photos, there was at least one between the first in 1936, and the one removed to make way for the 1968 version. TJ Courte, whose family lived at the point for many years, said her mom always said the beacon belonged to the queen, and they weren’t to climb on it!

I’ve tracked down a couple of old photos and of course, there was one when we built down here. My dad wrote several letters trying to get the lighthouse plot tidied up so it fit more neatly into the new subdivision, which they finally did. And they took up his offer to mow the lawn around the beacon in exchange for the use of the electrical outlet in the body of the tower, an outlet connected to the BC Hydro grid.

The first (I think) beacon.

The first (I think) beacon.

The beacon in the distance in the market garden days.

The beacon in the distance in the market garden days.

The second beacon behind the 1968 version.

The second beacon behind the 1968 version.

The new tower is nowhere near as dramatic a landmark as the old red and white rocket ship blinking its white light out into the strait (as well as into many of the houses in the neighbourhood). The new light flashes red and is much less intrusive. Its blocky silhouette with the solar panels and battery look a bit like a cheerful robot holding its hands out in greeting to the passing boats. We’ve decided to name it Brent after a dearly loved red-headed friend who died suddenly just a month before it was installed. A sturdy, stalwart beacon of light. Shine on, Brent.