Simon B. Jones's Blog: Slings and arrows, page 7

March 12, 2013

Rudolf Caracciola – The Original Meister

Well a new Grand Prix season is almost upon us and I for one am very excited. Many are asking whether anyone can stop the prodigiously talented German who has swept all before him over the past three seasons. This is, of course, a question that has been asked before in recent history but long before Vettel and Schumacher another German racer was regarded by many as the greatest of his generation.

Rudolf Caracciola 1901-1959

Rudolf Caracciola 1901-1959Rudolf Caracciola was born in Remagen in 1901. He began his career with Daimler-Benz as a humble car salesman but his passion was for racing cars rather than selling them. Thanks to his powers of persuasion he was able to secure modest support from his employers for his racing career and in 1926, by which time he was already a proven winner, he entered the inaugural Grand Prix of Germany at AVUS in a borrowed Mercedes M218 as a privateer. In spite of stalling on the opening lap and requiring a push start from his mechanic the 25 year old Caracciola nevertheless pulled off an incredible feat to fight his way through the forty four strong field in heavy rain to take the lead. Further drama ensued as Caracciola developed a miss-fire and was forced to pit for lengthy repairs. Back out on track he resumed his incredible progress and once more stormed into a lead he would hold until the end. With this remarkable victory Caracciola announced his arrival on the international racing scene and established a reputation for peerless driving in wet conditions.

Caracciola's 1926 German GP Win Caracciola’s victory proved to be life changing in every way. With the prize money from the race he was able to set up his own business and also married his girlfriend Charlotte. He continued to race in hill climbs and road races, winning the inaugural race on the new Nurburgring but suffering mechanical failure in the 1927 German Grand Prix on the same circuit. He shared victory in the 1928 event in spite of pulling out of the race suffering from heat exhaustion as his team mate Christian Werner took over his car and continued on to win the race.

Caracciola's 1926 German GP Win Caracciola’s victory proved to be life changing in every way. With the prize money from the race he was able to set up his own business and also married his girlfriend Charlotte. He continued to race in hill climbs and road races, winning the inaugural race on the new Nurburgring but suffering mechanical failure in the 1927 German Grand Prix on the same circuit. He shared victory in the 1928 event in spite of pulling out of the race suffering from heat exhaustion as his team mate Christian Werner took over his car and continued on to win the race.Caracciola remained a Mercedes stalwart, winning the European hill climbing championship in 1930 and competing in endurance racing. He competed at Le Mans and in the Mille Miglia thousand mile road race run on public roads between Rome and Brescia as well as continuing to win victories on the track.

By 1931 Mercedes had been forced to scale down their racing efforts in the face of global economic melt-down but they continued to support Caracciola and he did not disappoint; winning the German Grand Prix against the superior Bugattis of Louis Chiron and Achille Varzi by over a minute when the elements once more presented him with an opportunity to demonstrate his unrivalled ability to keep a racing car on track in the wet. Caracciola also triumphed in the 1931 Mille Miglia, becoming along with co-driver Wilhelm Sebastian the first non-Italian winners of the event. Driving his Mercedes SSKL at an average speed of 101km/h Caracciola won the race in record time.

Caracciola/Sebastian 1931 Mille Miglia

Caracciola/Sebastian 1931 Mille MigliaThe Italians took note and with the complete withdrawal of Mercedes Benz from racing in 1932 Caracciola was snapped up by Alfa Romeo although he would compete initially as a semi-independent and with inferior machinery to the leading Italian drivers. After a number of impressive performances however Caracciola was offered a place within the works team and went on to win four Grands Prix for Alfa Romeo that year including another German Grand Prix victory.

In the following year Alfa Romeo too felt the pinch and withdrew from racing, leaving Caracciola without a contract. Undaunted, he set out as a privateer outfit again; racing customer Alfas along with his friend Louis Chiron. In practice for the Monaco Grand Prix however, Caracciola suffered a serious accident, slamming into a wall at the Tabac corner and shattering his femur. As he was carried from the wreckage a bystander reassured Caracciola that Monte Carlo had an excellent hospital and that many famous people had died there. It would take him a year to recover and he would be left with a limp for the rest of his life. Further tragedy struck him during his recuperation in Switzerland when his wife Charlotte was killed in an avalanche whilst skiing, plunging Caracciola into deep despair.

The rise of the Nazis breathed new life into the sporting programmes of Mercedes Benz and their rivals Auto Union as the party willingly poured funds into motorsport as an ideal theatre to showcase German engineering and sporting prowess on the international stage and Caracciola was persuaded to return to racing and public life. For the sake of their careers Caracciola and his German contemporaries were obliged to join the NSKK; the Nazi party’s motorsport wing, although Caracciola never joined the Nazi party itself.

In 1934 Caracciola was back in a works Mercedes Benz although he struggled at times with the pain from his leg injury and a second place finish in the Spanish Grand Prix was his best result on the track.

Caracciola 1935 Tripoli GP In the following year however the German was back to his very best at the Tripoli Grand Prix which was a heavily wagered-upon race with starting grid positions being decided by lottery. The race was run to Formula Libre regulations and was not part of the more tightly regulated European Drivers Championship; forerunner of today’s World Championship. Caracciola drove a canny race on the rough and dusty desert track. Recovering from an early puncture just five laps into the race, Caracciola combined a blistering pace; at times lapping ten seconds a lap faster than his rivals, with an ability to look after his tyres that his modern equivalents would appreciate, to find himself in the lead when the Alfas of Nuvolari and Varzi struggled with tyre wear towards the end of the race.

Caracciola 1935 Tripoli GP In the following year however the German was back to his very best at the Tripoli Grand Prix which was a heavily wagered-upon race with starting grid positions being decided by lottery. The race was run to Formula Libre regulations and was not part of the more tightly regulated European Drivers Championship; forerunner of today’s World Championship. Caracciola drove a canny race on the rough and dusty desert track. Recovering from an early puncture just five laps into the race, Caracciola combined a blistering pace; at times lapping ten seconds a lap faster than his rivals, with an ability to look after his tyres that his modern equivalents would appreciate, to find himself in the lead when the Alfas of Nuvolari and Varzi struggled with tyre wear towards the end of the race.The European Drivers Championship for 1935 comprised five races of which Caracciola in his Mercedes W25 won three. In the penultimate event, the Spanish Grand Prix, Caracciola was required to start from the back of the grid as starting places were decided by lottery. By the first corner he was in the lead having mistaken the throttle for the brake pedal but somehow still made it around the turn and went on to win both the race and the championship.

In 1936 the European title went to Caracciola’s friend and rival Bernd Rosemeyer who drove for Auto Union although Caracciola banished his Monaco demons by winning the race. Caracciola went on to win a further two European championships in 1937 and 1938; being the only driver to achieve this feat. In 1937 he also married his second wife Alice.

As the rivalry between Mercedes Benz and Auto Union intensified, their battle embraced the quest for the world land speed record. On January 28th1938 on a stretch of newly constructed autobahn between Frankfurt and Darmstadt the two manufacturers set out to fight head to head for the record. Rudolf Caracciola made his attempt first, driving a stream-lined Mercedes W125 at a speed of 268.9 mph (432.7km/h) over a measured kilometre; setting a record for speed on a public road which stands to this day. It was a bitter-sweet achievement however for Rosemeyer was killed attempting to beat the record for Auto Union when cross-winds swept his car into a deadly somersault. The death of his friend caused Caracciola to question the value and purpose of a racer’s life but in the end he fatalistically accepted that the risk-taking Rosemeyer had inevitably run out of luck.

Rosemeyer prior to fatal 1938 world speed record attempt The advent of the Second World War brought such trivial pursuits to an end. Caracciola sat the war out in Switzerland and made plans to race in America at the war’s end. In 1946 he travelled to America and entered the Indianapolis 500 in a borrowed car, unfortunately hitting the wall during practice for the race in an accident which left him in a coma for several days.

Rosemeyer prior to fatal 1938 world speed record attempt The advent of the Second World War brought such trivial pursuits to an end. Caracciola sat the war out in Switzerland and made plans to race in America at the war’s end. In 1946 he travelled to America and entered the Indianapolis 500 in a borrowed car, unfortunately hitting the wall during practice for the race in an accident which left him in a coma for several days.In 1952 he made a return to racing in Europe, competing once more in the Mille Miglia but a crash in the Swiss Grand Prix of that year in which he hit a tree and suffered a serious fracture, this time in his other leg, proved to be a career-ending injury. Caracciola continued to work for Mercedes Benz, resuming his sales role and making use of his celebrity status. Sadly his health deteriorated rapidly and he died from liver failure in 1959, aged just 58.

He is remembered as one of the most talented and accomplished drivers of his own, or any generation; a three times European Grand Prix champion and a three times European hill climb champion; the fastest man on four wheels over a single mile or over a thousand miles, peerless in the rain and indomitable in the desert. A six time winner of the German Grand Prix; Rudolf Caracciola quite simply was the master.

Caracciola’s first Grand Prix victoryhttp://www.grandprixhistory.org/cara_bio.htm

Caracciola wins in Tripolihttp://forix.autosport.com/8w/caracciola.html

Caracciola and the land speed recordhttp://www.classicdriver.com/uk/magazine/3200.asp?id=11459

Caracciola wins the Mille Migliahttp://www.theautochannel.com/news/2006/03/12/000379.html

Published on March 12, 2013 02:12

March 5, 2013

By Jove - The Story of Jupiter

On a crisp winter’s evening a few days after Christmas, my wife Adele and I carefully carried my new telescope outside into the back garden. After a few trips back and forth to the house to fetch hats and gloves and a torch we were ready to take our first tottering steps into the world of astronomy.

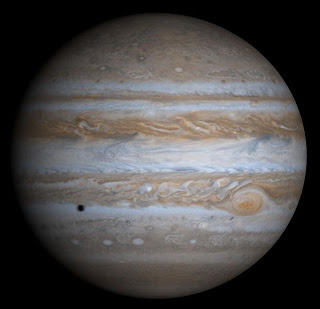

After a little trial and error, peering through the star pointer and twiddling the declination and right ascension knobs, we at last experienced a sudden eureka moment as the planet Jupiter all at once came into focus. Big and bright in the centre of the eyepiece there it was, with its dark bands of raging clouds clearly visible. We were very chuffed indeed. A few nights ago (at time of writing) I was even more excited when I once more brought the planet into focus and was able to observe all four of its moons.

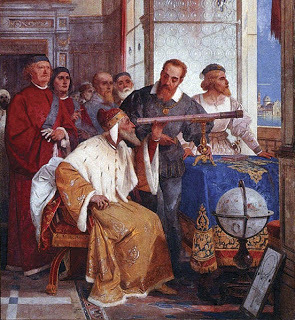

It was exciting enough for me. Just imagine therefore how chuffed another keen astronomer was one night in January 1610 when he pointed his new telescope skywards to investigate that same bright spot in the heavens and beheld for the first time through such an instrument the shining disc of Jupiter.

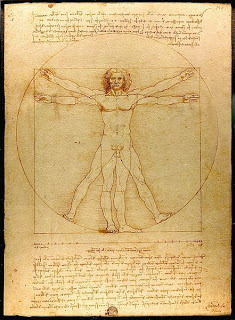

Galileo Galilei had already had some success with his shiny new toy which he had fashioned himself following a recently patented Dutch design rather than purchasing it from the internet as I had done. After carrying out observations of the lunar surface, Galileo turned his attention to Jupiter and was soon intrigued by the fact that the three stars around the planet were changing their positions relative to Jupiter and each other on a nightly basis. Galileo conducted nightly observations of Jupiter over the next eight weeks, during which he sketched the position of these Medician Stars as he had dubbed them in honour of his patron Cosimo di Medici. As he traced the movements of these bodies, which he observed did not twinkle like other stars, Galileo was able to conclude that there were in fact four rather than three of them and that they were orbiting around the planet Jupiter. This was a remarkable revelation, for it leant great weight to the highly inflammatory theory of Copernicus which proposed that the planets circled around the sun rather than the Aristotelian position favoured by the Catholic Church which maintained that the earth itself was the centre of the universe.

Galileo demonstrates a telescope to the Doge of Venice

Galileo demonstrates a telescope to the Doge of VeniceGalileo published his findings in his treatise Sidereus Nuncius. His work was immediately seized upon with great enthusiasm by one Johannes Kepler, who was at that time Imperial Mathematician at the university of Prague. Kepler was a keen adherant of Copernicus' theory and having obtained a telescope of his own soon published a response to Galileo supporting his findings. All at once the universe had been shown to possess not a single point around which all other heavenly bodies rotated but at least two. The earth-centric Aristotelian viewpoint had been shaken to the core.

Various unsatisfactory naming systems were put forward for the newly discovered satellites of Jupiter but it was Kepler who proposed the pleasing classical monikers that stuck. The moons of Jupiter, drawn irresistibly towards it as they were, Kepler suggested should be named after that notoriously seductive god’s best known sexual conquests: Io, Calisto and Europa. The fourth he proposed should be named Ganymede; after the young shepherd boy who was borne aloft by an eagle to serve as cup bearer to the greatest of the Gods.

Like Galileo, Kepler later suffered for his beliefs. He was hounded from his University position in 1626 as a result of his Protestant faith and his mother was even tried as a witch. One can only imagine how a man at the forefront of the enlightenment felt when faced with such barbarous superstition.

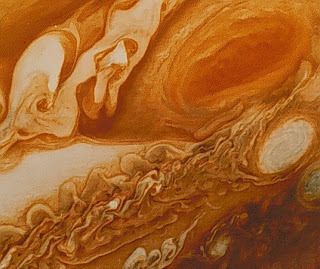

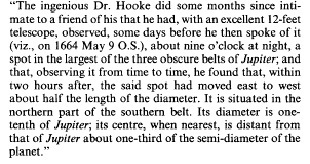

The best known of Jupiter’s landmarks is of course its great red spot. This remarkable surface feature; a giant storm the size of three earths, was first observed by English polymath and Royal Society founding member Robert Hooke in 1664. Hooke noted that the position of the spot changed over the course of several hours, leading him to conclude that the planet was rotating on its axis.

The best known of Jupiter’s landmarks is of course its great red spot. This remarkable surface feature; a giant storm the size of three earths, was first observed by English polymath and Royal Society founding member Robert Hooke in 1664. Hooke noted that the position of the spot changed over the course of several hours, leading him to conclude that the planet was rotating on its axis.

Proceedings of the Royal Society 1664 Also taking an interest in the progress of the red spot was Gian Domenico Cassini in Bologna. By tracking the spot's movements Cassini was able in 1665 to calculate Jupiter’s rotation period at 9hrs and 56 minutes. Cassini also studied the movements of Jupiter’s moons and was puzzled by the refusal of their orbits to conform to his predictions. In 1676 the eminent scholar, now based in Paris, found himself upstaged by his brilliant young pupil Olaus Roemer who proposed that the reason for the apparent variability in the orbit of Jupiter’s moons was due to the varying distance between Earth and Jupiter at different times according to their respective orbits. Because light travels at a finite speed, Roemer suggested, the light from the moons would sometimes take longer to reach the earth. Cassini dismissed the suggestion but Roemer was proved right when he correctly predicted that on a given date the moon Io would emerge from behind Jupiter ten minutes later than Cassini’s model suggested that it should. There was in fact nothing wrong with Cassini’s reckoning but due to the increased distance between the two planets, the moon was not visible at the time that it emerged as the light reflected from it took longer to reach the earth.

Proceedings of the Royal Society 1664 Also taking an interest in the progress of the red spot was Gian Domenico Cassini in Bologna. By tracking the spot's movements Cassini was able in 1665 to calculate Jupiter’s rotation period at 9hrs and 56 minutes. Cassini also studied the movements of Jupiter’s moons and was puzzled by the refusal of their orbits to conform to his predictions. In 1676 the eminent scholar, now based in Paris, found himself upstaged by his brilliant young pupil Olaus Roemer who proposed that the reason for the apparent variability in the orbit of Jupiter’s moons was due to the varying distance between Earth and Jupiter at different times according to their respective orbits. Because light travels at a finite speed, Roemer suggested, the light from the moons would sometimes take longer to reach the earth. Cassini dismissed the suggestion but Roemer was proved right when he correctly predicted that on a given date the moon Io would emerge from behind Jupiter ten minutes later than Cassini’s model suggested that it should. There was in fact nothing wrong with Cassini’s reckoning but due to the increased distance between the two planets, the moon was not visible at the time that it emerged as the light reflected from it took longer to reach the earth. Gian Domenico Cassini So there you have it. From the mere process of gazing up at a distant planet in the heavens and observing the movements of its surface features and moons, far greater minds than mine had deduced that the planets revolved around the sun, that Jupiter revolved upon its axis in a little under ten hours and that light travelled at a finite speed. By contrast I had merely pointed my telescope in the right direction, gawped up at the planet and been very pleased with myself at having observed it at all. Ah well, we can’t all be geniuses can we?

Gian Domenico Cassini So there you have it. From the mere process of gazing up at a distant planet in the heavens and observing the movements of its surface features and moons, far greater minds than mine had deduced that the planets revolved around the sun, that Jupiter revolved upon its axis in a little under ten hours and that light travelled at a finite speed. By contrast I had merely pointed my telescope in the right direction, gawped up at the planet and been very pleased with myself at having observed it at all. Ah well, we can’t all be geniuses can we?Galileo's observations of Jupiter's moons

http://home.comcast.net/~erniew/astro/sidnunj.html

The Great Red Spot

http://www.universetoday.com/15163/jupiters-great-red-spot

Cassini, Roemer and the Speed of Lighthttp://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/trying-to-measure-the-speed-of-light.html

Published on March 05, 2013 00:53

February 25, 2013

Justinian II - Mad, Bad and Dangerous

History is littered with infamous rulers; despots and madmen who brought terror and ruination to their subjects. One could endlessly debate the list of those whose deeds earn them a place in the Mad, Bad and Dangerous Hall of Fame. Here is the case for Justinian II; Emperor of Byzantium from 685 until his deposition and exile in 695. Following his bloody return to power in 705 his reign of terror continued until his final overthrow in 711.

Justinian came to power aged just sixteen; an age at which it seems that the world is at your feet even without the additional encouragement of imperial power being bestowed upon you. He bore a famous name and followed a very capable father whose achievements were considerable. Constantine IV had both defeated a mighty Arab host sent to lay siege to Constantinople and had presided over the reconciliation of the eastern and western Churches. He had been the epitomy of a Christian warrior emperor. Now his son was left with the unenviable task of filling his father’s prematurely vacated purple buskins.

The young emperor made a very promising start; securing an advantageous peace with his counterpart Abd al Malik, the newly established Caliph in Damascus. Abd Al Malik was in the process of fighting for universal recognition of his right to succeed his father as Commander of the Faithful and his need to secure his frontiers in order to focus on his internal problems obliged him to agree to the continuing payment of tribute to Byzantium. Empire and Caliphate may have been at peace for the moment, but Justinian was taking no chances.

He therefore embarked upon an effort to repopulate and restore the defences of Anatolia through large scale resettlement; strengthening the bulwark against future Arab attacks should the peace fail to hold up. In search of settlers Justinian had looked westward, to the burgeoning Slavic population in Thrace and the Balkans. Thousands of Slav families were relocated to Anatolia where they were given land in exchange for military service, replenishing the manpower reserves of the empire with hardy soldier farmers who had a real stake in defending the land from invasion, not that they had been given much choice in the matter.

Justinian II

Justinian IIIt was not long however before the cracks began to appear. The young emperor was determined to live up to the memory of his illustrious predecessors; his namesake Justinian I, his great-great-grandfather Heraclius, his grandfather Constans II and of course his father Constantine IV. In his youthful ambition to emulate the deeds of these forebears he was driven to rash acts. He spent vast sums which his treasury could not support on ostentatious building projects in imitation of the first Justinian. He antagonised the Pope and unsuccessfully sought to have him arrested after a trivial dispute over matters of doctrine; seeking to repeat both Justinian I’s and Constans’ bold exercises of imperial prerogative when recalcitrant Popes had defied them. He rejected the Caliph’s tribute payment which came in the form of unfamiliar new coins and tore up the treaty upon which the ink was barely dry; launching expeditions to attempt to regain control of Armenia and Cyprus in search of a war with the infidel to make his name glorious like that of his father. His insatiable demand for money to fund all of these enterprises prompted him to unleash a reign of terror upon his subjects, both rich and poor alike. The newly transplanted settlers were taxed beyond their means whilst the wealthy of Constantinople were forced to part with vast sums through a campaign of intimidation, arrest, torture and imprisonment. The loyalty of both was stretched to breaking point.

Justinian II well and truly staked his claim for inclusion in the Mad, Bad and Dangerous Hall of Fame following the defeat of his army at Sebastopolis on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia. The Muslims advanced with copies of the defunct peace treaty attached to their spears and were victorious when twenty thousand Slavic troops understandably deserted the imperial cause and joined them. In the aftermath of this military disaster the ruler of Armenia transferred his undivided allegiance to the caliph. The emperor did not take the news of this development well. The defeated Byzantine commander Leontius was flung into prison and in his fury Justinian ordered the massacre of the families of the Slav deserters in Nicomedia. Thousands of women and children were slaughtered and their bodies thrown into the sea; innocent victims of the emperor’s impotent rage.

After three years Leontius was released from gaol since Justinian had need of his generalship in the Balkans. If the emperor thought that there would be no hard feelings he was very much mistaken for Leontius was feeling somewhat bitter after his incarceration and lost no time in setting out to overthrow the man who had unjustly locked him up. The emperor’s behaviour had not improved in the interlude and support for a coup was not difficult to find. Leontius and his supporters forced their way into the prison of Constantinople and released all those held there at the emperor’s pleasure. Arming themselves they then went forth into the city and called upon the citizens to make their way to the great cathedral of Hagia Sofia. There Leontius was crowned as emperor by the patriarch and the mob then set off to storm the palace of Justinian. Those cronies who had earned the hatred of the people through carrying out Justinian’s bidding were dragged through the streets and burned at the stake whilst the erstwhile emperor was brought before the jeering crowds in the hippodrome and publically mutilated. He suffered a fate known as rhinocopia; the slicing off of his nose. This grizzly operation was intended to render him physically imperfect and therefore unfit for imperial office. Justinian then received the sentence of exile and was dispatched to distant Cherson in the Crimea; there to reflect on his misfortune, nurse his resentment and contemplate his revenge.

The fall of the isolated imperial outpost of Carthage to the Arabs in 698 precipitated further upheaval in Constintinople. A relief force had been dispatched to reinforce Carthage but had arrived too late to save the city. With a large military force at their disposal and nothing to show for their efforts, the Byzantine commanders had reservations about returning to Constantinople to report the failure of the expedition. It would be far better they decided, to make use of their forces to rebel against the incumbent emperor. Electing one of their number whom they declared as Emperor Tiberius III, the fleet turned for home flying the flag of revolt. In the city the Green faction rose up in support of the rebel fleet as it sailed into the harbour and Leontius was overthrown with minimal resistance. He now suffered the same fate which he had inflicted upon Justinian and was banished, noseless, to a monastery.

Meanwhile in Cherson the exiled Justinian, complete with golden false nose, was plotting his comeback. After eight years of languishing in this backwater on the edge of the empire his desire for revenge was undimmed and he had made no secret of the fact. Fearing that he may be returned to Constantinople and deprived of his head as well as his nose by the new regime of Tiberius, Justinian decided that it was time for a change of scene and slipped away, taking ship eastwards along the Black Sea coast to the land of the Khazars. These were a formally nomadic people who had settled around the northern shores of the Black Sea and had curiously embraced the Jewish faith. Their ruler the Khagan was happy to receive Justinian as an honoured guest and even married his sister to the fugitive emperor.

For the next two years Justinian lived the quiet life of a happily married man but then the assassins came; sent by the Khagan in response to demands from Constantinople to surrender Justinian dead or alive. Justinian however was ready for them and was able to dispatch his two would-be killers with his bare hands. The time had clearly come for him to make his attempt to regain his throne and there was no time to waste. Stealing a boat, he made his way back to Cherson and was able to make contact with his supporters in the city. With this single vessel and a handful of companions Justinian set out across the Black Sea, into the teeth of a fearsome storm. As the storm raged and the waves threatened to swamp the boat, Justinian was encouraged by one of his companions to made a pledge to forgive his enemies if God should spare them from the sea. ‘If I should spare a single one of them, then may God drown me!’ spat the emperor by way of response.

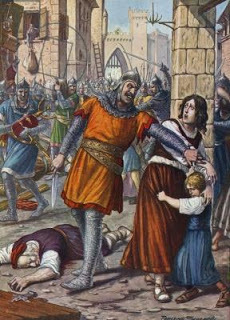

Justinian and Terval Bedraggled and vengeful, Justinian fetched up on the western shore of the Black Sea in the domain of the Bulgars. Here too he was welcomed with open arms and soon he had contracted an alliance with their Khan Tervel, promising him the title of Caesar as well as the hand of his daughter from his previous marriage if the Bulgars would march on Constantinople. Naturally Terval agreed to help Justinian regain his throne and prepared for war. All at once the former emperor had gone from being a hunted man fleeing for his life in a lonely boat to having an army at his back. He knew however that it was one thing to appear before the walls of his capital at the head of a horde of barbarians but it was quite another to actually take the city. It had been tried unsuccessfully before and so the gates remained closed in the face of Justinian’s demands for surrender as Tiberius determined to resist. The wily Justinian therefore once more took his fate in his own hands and boldly led a small raiding party which made its way through a water conduit under the defences where the Theodosian Walls met the sea walls along the Golden Horn. Emerging on the other side, Justinian’s force surprised and killed the guards and took control of the Blachernae Palace. The city awoke to a fait accompli. Justinian was now inside the walls and was quite able to admit his Bulgar allies to wreak destruction if he met with any resistance whilst Tiberius had fled. The usurper was soon run to ground as was his predecessor Leontius and both were brought before the baying crowds of the hippodrome and there beheaded.

Justinian and Terval Bedraggled and vengeful, Justinian fetched up on the western shore of the Black Sea in the domain of the Bulgars. Here too he was welcomed with open arms and soon he had contracted an alliance with their Khan Tervel, promising him the title of Caesar as well as the hand of his daughter from his previous marriage if the Bulgars would march on Constantinople. Naturally Terval agreed to help Justinian regain his throne and prepared for war. All at once the former emperor had gone from being a hunted man fleeing for his life in a lonely boat to having an army at his back. He knew however that it was one thing to appear before the walls of his capital at the head of a horde of barbarians but it was quite another to actually take the city. It had been tried unsuccessfully before and so the gates remained closed in the face of Justinian’s demands for surrender as Tiberius determined to resist. The wily Justinian therefore once more took his fate in his own hands and boldly led a small raiding party which made its way through a water conduit under the defences where the Theodosian Walls met the sea walls along the Golden Horn. Emerging on the other side, Justinian’s force surprised and killed the guards and took control of the Blachernae Palace. The city awoke to a fait accompli. Justinian was now inside the walls and was quite able to admit his Bulgar allies to wreak destruction if he met with any resistance whilst Tiberius had fled. The usurper was soon run to ground as was his predecessor Leontius and both were brought before the baying crowds of the hippodrome and there beheaded.Justinian’s revenge against all those whom he felt had betrayed him was terrible and his list was long. Executions, burnings, blindings, hangings and drownings ensued by the hundred as the emperor settled every last score. As the reign of terror continued, it became apparent that the emperor was losing his grip on reality. Soon his malice was being unleashed against whole cities as reason steadily abandoned him. In 709 Ravenna was sacked on his orders after its bishop had displeased him. Two years later it was the people of Cherson, against whom he had long held a grudge from his days of exile, who felt his wrath.

The Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor probably gets a little carried away relating the terrors perpetrated on the citizens of Cherson on the orders of the emperor during his final descent into raving madness, but even allowing for some artistic licence it is clear that a monster was reigning in Constantinople. Arriving in Cherson, the punitive expedition rounded up every civilian they could find and put them to the sword, sparing only the very young who were enslaved. The leading citizens were put to death either by being roasted alive on spits or tied up on board a ship which was taken out to sea and sunk.

On its return voyage the Byzantine fleet was wrecked in a storm and thousands of sailors were drowned. When he was brought the news of the disaster Theophanes tells us that Justinian burst into hysterical laughter; his mind utterly unhinged. Dissatisfied with the level of bloodshed inflicted in Cherson Justinian ranted and raved. Soon he was planning a second expedition to return to the city and finish the job; wiping out the population and leaving not a stone standing.

The majority of the citizens of Cherson had sensibly taken to the hills upon the approach of the first Byzantine fleet, forewarned of the emperor’s intentions. Not surprisingly, having so far escaped Justinian’s wrath they now rebelled against him and sought an alliance with the Khazars who sent an army to the defence of the city. An exiled Byzantine general named Philippicus was proclaimed as a rival emperor and when Justinian’s second fleet arrived in Cherson in 712 charged with its total destruction, their commander soon decided to side with the rebels since the Khazars were too numerous to be defeated. The emperor’s fate was sealed as the fleet turned about and sailed back to Constantinople to overthrow him. Justinian was in Sinope on the Black Sea when he heard news of the rebellion and by the time he had hurried back to Constantinople he was too late for Philippicus had already taken the city. Abandoned by his troops, the emperor was apprehended outside the city and summarily executed. His six year old son Tiberius, the offspring of his second marriage to the Khazar princess, was dragged from the church where he had been taken for sanctuary and had his throat slit ‘like a sheep’.

So ends the story of Justinian II; a cautionary tale that if you overthrow a tyrant you should cut off more than just his nose.

Sack of Ravenna 709 by Scarpelli

Sack of Ravenna 709 by ScarpelliI was lazy for this article and reused material from my own book The Battles are the Best Bits, but if you liked it please check out the book. http://www.amazon.com/The-Battles-Best-Bits-ebook/dp/B008GT05IY

Published on February 25, 2013 11:53

February 18, 2013

Another Pair of Aces - Lavrinenko and Knispel

As a follow up to my post on the top scoring German and Soviet aerial aces of World War II, I thought I would check out the respective top scoring Soviet and German tank aces of the war. They were, so the readily available statistics tell me, Dmitri Lavrinenko and Kurt Knispel.

Statistics however do not tell much of a story on their own. There is a dearth of information online in English on Lavrinenko, whose 52 confirmed kills make him the highest scoring allied ace of the conflict. This is due to two reasons. Firstly in comparison to a number of German tank aces Lavrinenko’s tally is quite low. The reason for this and for his relative obscurity is that Dmitri Lavrinenko lost his life early in the war; being killed by flying shrapnel from an exploding mine on 18thDecember 1941. At the time of his death the twenty seven year old former school teacher had been at war for just two and half months and had seen action on 28 occasions. He was therefore a remarkable tank fighter indeed.

Lavrinenko had endured a baptism of fire in Ukraine, nursing his damaged tank back to safety as the Russians retreated before the German blitzkrieg.

As the Wehrmarcht closed in on Moscow, Lavrinenko joined the First Guards Brigade charged with the defence of the capital. He found himself almost constantly in battle as the German attempt to capture Moscow gradually bogged down in the face of the fearsome Russian winter before the defenders began to turn the tide as the counter-offensive commenced in December. Fearless in engaging the enemy and prodigious in the accuracy of his aim, on one occasion taking out seven enemy tanks with seven rounds when ambushing a German column in the open field; his white painted T34 invisible against the snow, Lavrinenko soon came to the attention of his superiors and shortly before his death had earned the Order of Lenin. He was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1990 having played a significant role in the salvation of his nation’s capital. In contrast to Larinenko the top scoring German tank ace of the war Kurt Knispel survived to within days of the war’s end. The former mechanical apprentice joined the German army in 1940 and trained as a gunner and loader, seeing action for the first time in a Panzer IV during operation Barbarossa in 1941. By the time his unit reached the gates of Stalingrad, Knispel was a tank commander with 12 credited kills. Knispel escaped the debacle of the defeat at Stalingrad, having been returned to Germany for training in operation of the new Tiger tank. He was back on the eastern front in time to take part in the Battle of Kursk and its aftermath before being transferred west to fight in the defence of Normandy, seeing fierce fighting around Caen.

As the Wehrmarcht closed in on Moscow, Lavrinenko joined the First Guards Brigade charged with the defence of the capital. He found himself almost constantly in battle as the German attempt to capture Moscow gradually bogged down in the face of the fearsome Russian winter before the defenders began to turn the tide as the counter-offensive commenced in December. Fearless in engaging the enemy and prodigious in the accuracy of his aim, on one occasion taking out seven enemy tanks with seven rounds when ambushing a German column in the open field; his white painted T34 invisible against the snow, Lavrinenko soon came to the attention of his superiors and shortly before his death had earned the Order of Lenin. He was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1990 having played a significant role in the salvation of his nation’s capital. In contrast to Larinenko the top scoring German tank ace of the war Kurt Knispel survived to within days of the war’s end. The former mechanical apprentice joined the German army in 1940 and trained as a gunner and loader, seeing action for the first time in a Panzer IV during operation Barbarossa in 1941. By the time his unit reached the gates of Stalingrad, Knispel was a tank commander with 12 credited kills. Knispel escaped the debacle of the defeat at Stalingrad, having been returned to Germany for training in operation of the new Tiger tank. He was back on the eastern front in time to take part in the Battle of Kursk and its aftermath before being transferred west to fight in the defence of Normandy, seeing fierce fighting around Caen.

As the Soviets advanced into Czechoslovakia, Knispel once more found himself on the eastern front, resisting the Soviet onslaught, in one engagement his Tiger was hit 24 times. Finally his luck ran out. On 28th April 1945 even as Hitler was making his preparations for suicide, Knispel was fatally wounded in an explosion during fighting near Wostitz and died shortly afterwards in a field hospital. He was just 23 years old. During his remarkable career as a tank commander Knispel is credited with an incredible 168 kills. In spite of this achievement and of being recommended for the Knights Cross on four occasions, Knispel never received the honour. His general lack of military bearing and respect for authority have been blamed for this. His assault on an SS officer whom he witnessed mistreating Soviet POWs especially blotted his copybook with officialdom. In the eyes of posterity however it is this incident which stands out as the mark of the man and it is for that rather than the number of tanks that he destroyed that we can respect him as a man and as a soldier.

Kurt Knispel and Dmitri Lavrinenko

Kurt Knispel and Dmitri LavrinenkoBTW if any WW2 buffs can make a positive identification of the two tank photographs that would be cool as I was not feeling sufficiently confident in their provenance to give them a caption.

Any suggestions for future 'Pair of Aces' features also very welcome.

Battle for Moscowhttp://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=37

Lavrinenkohttp://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=5689

Knispelhttp://celebritymemorials.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=285&Itemid=85

Published on February 18, 2013 07:31

February 12, 2013

Iconoclasm – a Byzantine Tragedy – Part Three

In the last post I told of how the empress Irene overturned iconoclasm only to be consumed by her lust for power. Following Irene’s deposition and exile in 802 the reins of power in Constantinople had been taken up by a one-time treasury official named Nicephorus. Having been driven to take action by the empress’ fiscal abuses, the new emperor swiftly found himself having to put aside his ledger and take up his sword in defence of the empire against a potent new threat.

Krum is brought the skull of Nicephorus

Krum is brought the skull of Nicephorus The rise of the Bulgars under their charismatic and warlike leader Krum would prove to be the greatest challenge for the house of Nicephorus and would ultimately bring about its downfall. Krum had succeeded in uniting his people as never before, bending petty warlords to his will in order to assemble an unprecedented level of military might. Nicephorus had faced the challenge head on, but his pre-emptive strike against the Bulgars had ended in the slaughter of his army and the sack of the imperial city of Serdica. Nicephorus soon struck back, leading his armies in person against the Bulgar capital Pliska and razing it to the ground. Two years later in 811 he returned with a greater army still and repeated the exercise, pursuing Krum’s forces into the mountains. As he encamped in the pass of Verbitza however, the emperor found his army entrapped and encircled by the Bulgars who then fell upon them with great slaughter. Nicephorus was killed in the fighting and Krum later had the emperor’s skull fashioned into a drinking cup in celebration of his victory. His son and successor Stauracius lingered on for six months, paralysed by his wounds until he too succumbed. The empire then passed to Nicephorus’ son in law Michael who proved an incapable ruler. Having failed to inspire his troops to follow him against Krum, Michael returned to Constantinople following a mutiny. He nevertheless rejected peace terms from the Bulgar Khan, but then vacillated as Krum laid siege to and captured the city of Messembria on the Black Sea.

It seemed that the military fortunes of the empire were at an all-time low. The depredations of Harun al Rashid had been ended only by that great Caliph’s death and now a barbarian chieftain was rampaging across imperial territory with impunity, swigging his wine from a dead emperor’s skull. It was to their sins that the people of the empire must look for the reason for their misfortune and many concluded that it was the resumption of the veneration of icons that had so displeased the almighty and caused him to turn his face from the Romans. During a service in the Church of the Holy Apostles a mob surrounded the tomb of Constantine V; loudly imploring the iconoclast emperor to rise from his tomb and lead them in battle against the Bulgars.

In the absence of the risen Constantine, Michael would have to do and the emperor duly led his armies out once more to meet the Bulgars on the plain of Versinicia in the summer of 813. At first the battle seemed to be going well but then the entire Byzantine right wing, which consisted of the iconoclastically minded Anatolian troops, turned tail and fled the field, leaving the emperor with little choice but to follow them. This left the Byzantine left wing, who had been making good progress, to be slaughtered by the Bulgars. In the aftermath Michael, convinced that he had lost the backing of both God and his people, was persuaded to abdicate and was succeeded on the throne by Leo, the commander of the treacherous right wing.

Having escaped a Byzantine assassination attempt, Krum embarked on a campaign of devastation right up to the walls of Constantinople but with no hope of breaching them he was forced to return home and within a year he was dead.

What further proof could be needed of the support of the Almighty for the regime of Leo than this change in imperial fortunes? Iconoclasm was firmly back on the agenda and Leo, finding that the Patriarch refused to cooperate with his plans, had him arrested. Leo then summoned a synod dominated by iconoclastically minded bishops who deposed the Patriarch and condemned the findings of the Second Council of Nicaea. Those who sought to oppose the motion were beaten up and spat upon. The emperor let it be known that any holy image could be destroyed with impunity, sparking another orgy of destruction as more precious artwork was reduced to firewood. Irene was no doubt turning in her grave.

Thomas the Slav is brought before Michael II

Thomas the Slav is brought before Michael II Leo himself fell victim to a coup on Christmas day 820; cut down in the palace chapel in the midst of the service whilst desperately defending himself from his attackers with a golden cross which he had seized from the altar. His fate however did not presage a change in religious policy and the usurper Michael II maintained an iconoclast stance. He soon faced rebellion led by a charismatic rabble rouser known as Thomas the Slav who raised a large force against him and marched on the capital. Thomas succeeded in gathering his immense support through endevouring to be all things to all people; at times claiming to be the murdered emperor Constantine VI back from the dead and promising social revolution. He also promised the restoration of the icons. Thomas’ revolt was ultimately unsuccessful. This would-be champion of the cause of icon worship was defeated beneath the walls of Constantinople, run to ground and beheaded.

Under Michael II and his son and successor Theophilus, iconoclasm remained the entrenched position of the rulers of Byzantium but they did not prosecute it with the fervour of their predecessors and generally displayed tolerance to those who chose to worship icons in the privacy of their own homes. Examples were none the less made when they needed to be. A monk named Methodius who attempted to secure the support of the Pope for the restoration of the icons was scourged and imprisoned during the reign of Michael and under Theophilus the celebrated icon painter and future saint Lazarus had his hands branded with white-hot horseshoes after refusing to destroy an icon he had painted.

The iconoclasts by Morelli shows the punishment of Lazarus

The iconoclasts by Morelli shows the punishment of Lazarus That for the most part the second succession of iconoclast emperors practiced a greater degree of tolerance towards their icon venerating subjects than had Leo III and Constantine V is perhaps an indication that they had little choice. If the first iconoclastic movement was a crusade against idolatry, the second was far more a reaction to prevailing public opinion and as a result the iconoclasts trod more carefully amongst a population which still harboured a great many icon lovers. The cause of the icons was championed by the venerable Abbot Theodore of the Studium who, having endured torture and imprisonment under Leo V, was at liberty to appeal for their restoration under his successors.

Slowly but surely, the tide began to turn in favour of the veneration of images once more.This may in part have been due to the resurgence in the east of the forces of Islam. Under Michael II, Sicily and Crete had fallen to freebooting Arab invaders. Theophilus had been obliged throughout his reign to wage war against the Abbasid Caliphs Mamun and Mutasim who led their forces deep into imperial territory. The emperor had celebrated his modest victories over the Saracens with great pomp, triumphal processions and races in the hippodrome in which he himself took part. It was an inescapable fact however that the empire was on the back foot, brought home in 838 when the emperor’s ancestral city of Amorium fell to the armies of Mutasim and was brutally sacked, with the terrorised citizens burned alive in the church where they had sought refuge. Another group of prisoners were later beheaded beside the Tigris for refusing to convert to Islam and are celebrated as the 42 Martyrs of Amorium. At such a time, with rumours of a great fleet being gathered against Constantinople, the people of the empire looked increasingly towards the familiar comfort of their icons and their saints for their salvation. They doubtless remembered how, in times of peril, the precious icon of the Virgin had been carried around the walls of the city and her divine protection had seen the terrible designs of Persians and Avars, Saracens and Bulgars brought to destruction and ruin.

The siege of Amorium

The siege of Amorium Meanwhile within the palace itself, under the emperor’s very nose, his wife and mother made little secret of their practice of venerating icons. Theophilus died in 842, leaving his widow Theodora as regent for the young emperor Michael. With power in her hands the empress swiftly convened a council which deposed the iconoclast patriarch, electing in his place that Methodius who had suffered torture and imprisonment for his beliefs in the reign of Michael II and upholding the findings of Irene’s Second Council of Nicaea. The age of iconoclasm was ended and in a great outpouring of thanksgiving icons were carried high in procession through the streets to the great church of St Sofia. In time the image of Christ above the palace gate first destroyed on the orders of Leo III and torn down once more by Leo V was replaced a final time, crafted anew by the brand-scarred hands of St Lazarus.

St Lazarushttp://iconreader.wordpress.com/2011/11/17/lazarus-of-constantinople-the-first-iconographer-saint/

The 42 Martyrs of Amoriumhttp://www.losttothewest.com/?p=37

Published on February 12, 2013 00:54

February 4, 2013

The Intrepid has landed – the Apollo 12 Mission

We all know about Apollo Eleven; “One small step for man…” and all that. And we all know about Apollo “Houston we have a problem!” Thirteen. Somewhat overlooked in between the epoch-making triumph of the first moon landing and the against-the-odds survival story that made the failed Apollo 13 mission Hollywood blockbuster material, came the very successful second moon landing conducted by the crew of Apollo 12 just four months after Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins made history.

Being in the process myself of developing an interest in matters astronomical having recently acquired my first telescope I found myself wondering this very thing as I contemplated a map of the lunar surface and found that Apollo 12 has an interesting story of its own to tell, albeit without the drama of the missions which immediately preceded and followed it.

Apollo 12 astronaut Alan Bean on the moon

Apollo 12 astronaut Alan Bean on the moonWithin less than a minute of the mighty Saturn V rocket carrying the crew of Apollo 12 launching from Cape Kennedy, disaster threatened the mission. Astronauts Alan Bean, Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad aboard the command module named Yankee Clipper experienced a sudden loss of power to electrical systems and controllers on the ground briefly lost telemetry as the rocket was struck by lightning. The situation proved recoverable with no permanent damage and the rocket, watched by President Nixon, continued on its journey into the heavens. This was the first time that a serving president had been present for an Apollo launch.

Docking with the lunar module Intrepid was successful and gave the crew the opportunity to inspect the command module for damage. The onward journey to the moon passed uneventfully enough as the crew broadcast TV pictures back to earth.

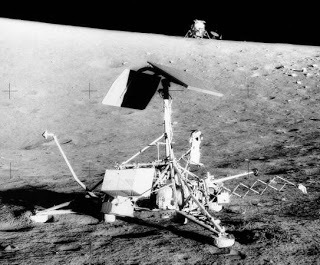

On November 19th1969 the Intrepid, piloted by Conrad with Bean accompanying him, made its descent to the lunar surface. For this second mission a landing site in the region known as the Ocean of Storms had been selected. The crew of the Intrepid were tasked with landing close to and recovering parts from the lunar probe Surveyor III. In an impressive display of pilot skill Conrad brought the landing module down within six hundred feet of Surveyor III. On stepping from the ladder Conrad commented that it may have been a small step for the taller Armstrong but it was a long one for him! Bean and Conrad spent 31 hours in total on the lunar surface, far longer than the Apollo 11 mission. During that time they conducted three moonwalks; setting up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), recovering samples from the surface and retrieving parts from Surveyor III.

Surveyor III with Intrepid in background

Surveyor III with Intrepid in backgroundHaving made a successful return to orbit and reunited with Gordon aboard the Yankee Clipper the crew made a photographic study of the moon from orbit to aid future landings and monitored the seismic impact of the ascent stage of the lunar module as it plummeted back to the lunar surface. On November 24th the Yankee Clipper made a successful return to earth, splashing down in the Pacific to be recovered by the USS Hornet. At this point Bean proved that misfortunes come in threes as he was hit on the head and knocked unconscious by a flying camera. Earlier in the mission Bean had accidentally destroyed the crew’s cine-camera by pointing it at the sun and had misplaced the camera timer intended to take a picture of both astronauts on the moon from the lunar module.

Both Bean and Conrad went into space again with the Skylab missions but Gordon, who was scheduled to walk on the moon with the cancelled Apollo 18 mission, never made it into space again.

Apollo 12 Splashdown in the Pacific

Apollo 12 Splashdown in the PacificBritish Pathe footage of Apollo 12 launchhttp://www.britishpathe.com/video/apollo-12-blast-off/query/apollo+12

NASA Apollo 12 Pagehttp://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo12.html

The Apollo 12 mission in detailhttp://history.nasa.gov/SP-4029/Apollo_12a_Summary.htm

Published on February 04, 2013 03:23

January 29, 2013

Iconoclasm - A Byzantine Tragedy - Part Two

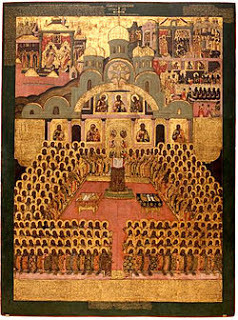

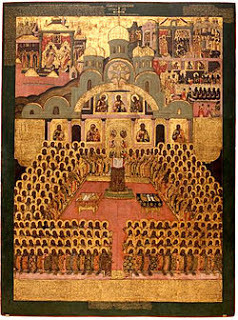

The image below depicts the Second Council of Nicaea in 787; an event celebrated in the Greek church to this day as the triumph of orthodoxy. It was nominally presided over by the young Byzantine emperor Constantine VI but was the crowning glory in the career of his mother the Empress Irene. An inveterate schemer, Irene the widow of Leo IV had overseen the restoration of icon worship following the death of her husband in 780.

7th Ecumenical Council Nicaea 787 Leo had taken a moderate stance in comparison to his arch-iconoclast father Constantine V; ending the persecution of the monasteries. Nevertheless as he reached the end of his days he took a harder iconoclastic line as he pondered the fate of his soul and distanced himself from his icon-loving Athenian wife.

7th Ecumenical Council Nicaea 787 Leo had taken a moderate stance in comparison to his arch-iconoclast father Constantine V; ending the persecution of the monasteries. Nevertheless as he reached the end of his days he took a harder iconoclastic line as he pondered the fate of his soul and distanced himself from his icon-loving Athenian wife.

With Leo dead, Irene assumed the regency of the empire for her ten year old son Constantine and immediately embarked upon the course of reform; systematically sidelining all of those who would oppose her agenda both for the restoration of the icons and to establish herself as the de-facto ruler of the empire.

Sympathy for the iconoclastic cause remained strong, particularly in the empire’s eastern provinces where the majority of Irene’s armies were stationed. Following the old emperor’s death some of these troops had attempted a revolt with the intention of placing his brother on the throne. This had been swiftly put down and Irene thereafter had set out to purge the army. Her willingness to dismember the empire’s forces; removing capable commanders and disbanding troops whose loyalty was suspect, sparked widespread mutiny and rendered the imperial frontiers vulnerable to invasion. The highly capable Abbasid prince Harun al Rashid led an invasion in 782 which swept into Byzantine territory meeting with little opposition and indeed many of the imperial forces defected to the enemy. Irene was forced to buy peace from the future Caliph.

For those who were dismayed by the Empress’ actions, her son Constantine was an obvious focal point. The armies in the east remained staunchly iconoclast and those in the capital who longed to overturn Irene’s reforms therefore had a ready source of manpower to call upon and a suitable figurehead in the form of Constantine. Matters came to a head in 790 when Irene attempted to seize supreme power for herself; flinging her son into prison when a plot by leading iconoclasts for her overthrow and exile came to light. With Constantine behind bars, Irene demanded an oath of loyalty from all of her armies. This galvanised the eastern opposition who marched on the capital and restored Constantine to his throne. Irene, deposed, was left to stew in the confinement of her palace and plot her revenge.

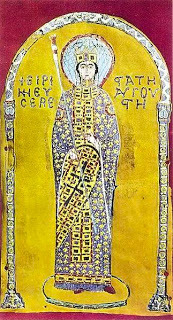

She did not have long to wait. Within two years her son had shown himself to be hopelessly incapable of government and had her recalled. For the next five years mother and son resumed their uneasy partnership but Constantine through military blunders and an ill-advised divorce steadily lost support until finally Irene felt safe enough to make her move. For a second time Constantine was seized and imprisoned but this time his mother was taking no chances and ordered her son blinded. The punishment was carried out, in the very room in which he had been born, with such brutality as to cause his death. It was a crime which sent a shockwave through the empire and it left Irene as empress and sole ruler. (shown left depicted as such)

She did not have long to wait. Within two years her son had shown himself to be hopelessly incapable of government and had her recalled. For the next five years mother and son resumed their uneasy partnership but Constantine through military blunders and an ill-advised divorce steadily lost support until finally Irene felt safe enough to make her move. For a second time Constantine was seized and imprisoned but this time his mother was taking no chances and ordered her son blinded. The punishment was carried out, in the very room in which he had been born, with such brutality as to cause his death. It was a crime which sent a shockwave through the empire and it left Irene as empress and sole ruler. (shown left depicted as such)

Her actions had an unintended and far reaching consequence. Three years later as Pope Leo III was contemplating how best to honour and reward his champion and saviour; Charles King of the Franks, the son

of Pepin the Short, he could observe that the title of Emperor of the Romans was conveniently vacant, for the Pope did not recognise the right of a woman to hold that title.

On Christmas Day 800 therefore, since Irene remained the sole ruler in Constantinople, Leo was able to confer the imperial title upon Charles; whose efforts in the cause of Christianity had gone a considerable way towards the restoration of a western empire.

In Constantinople such presumption seemed ludicrous. Who was this semi-literate barbarian who laid claim to the legacy of Augustus and Constantine? Nevertheless Irene had continued to alienate her subjects. Her continuing appeasement of the now-Caliph al-Rashid with ever greater payments of protection money and her increasingly desperate attempts to buy her subjects’ affections through unaffordable tax breaks, convinced many that her deposition would be vital for the future wellbeing of the empire. When two years after his coronation Irene began seriously to entertain proposals of marriage from Charlemagne; an act which would unite the rival eastern and western claimants to the Empire of the Romans and place the Frankish ruler on the throne of Byzantium, she had at last gone too far. Her own officials convened an assembly in the hippodrome and declared her deposed. She was exiled to an island in the Marmara and died a year later.

Irene has gone down in history as a wicked schemer, driven by ambition to commit the worst crime any mother could commit; the cold-blooded murder of her own child. In the iconoclastic struggle however, she struck the decisive, if not the final blow. Although the findings of the council she had convened in Nicaea in 787, anathemitizing the writings of the iconoclasts, would be challenged anew within a decade of her death and ultimately overturned, it would in the end stand as the final word on the veneration of icons.

The present Canon decrees that all the false writings which the iconomachists composed against the holy icons and which are flimsy as children’s toys, and as crazy as the raving and insane bacchantes — those women who used to dance drunken at the festival of the tutelar of intoxication Dionysus — all those writings, I say, must be surrendered to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, to be put together with the other books by heretics — in such a place, that is to say, that no one will ever be able to take them therefrom with a view to reading them. As for anyone who should hide them, with a view to reading them himself or providing them for others to read, if he be a bishop, a presbyter, or a deacon, let him be deposed from office; but if he be a layman or a monk, let him be excommunicated.

Leo III crowns Charlemagne The Seventh Ecumenical Council in full

Leo III crowns Charlemagne The Seventh Ecumenical Council in full

http://www.intratext.com/IXT/ENG0835/__P4V.HTM

Some good sites featuring iconographic art

http://www.mountathos.gr/active.aspx?mode=en{2aee45f1-c81e-4f0c-9cf9-c2efe471cfd1}View

http://econcept.dk/icon/dox.html

7th Ecumenical Council Nicaea 787 Leo had taken a moderate stance in comparison to his arch-iconoclast father Constantine V; ending the persecution of the monasteries. Nevertheless as he reached the end of his days he took a harder iconoclastic line as he pondered the fate of his soul and distanced himself from his icon-loving Athenian wife.

7th Ecumenical Council Nicaea 787 Leo had taken a moderate stance in comparison to his arch-iconoclast father Constantine V; ending the persecution of the monasteries. Nevertheless as he reached the end of his days he took a harder iconoclastic line as he pondered the fate of his soul and distanced himself from his icon-loving Athenian wife.With Leo dead, Irene assumed the regency of the empire for her ten year old son Constantine and immediately embarked upon the course of reform; systematically sidelining all of those who would oppose her agenda both for the restoration of the icons and to establish herself as the de-facto ruler of the empire.

Sympathy for the iconoclastic cause remained strong, particularly in the empire’s eastern provinces where the majority of Irene’s armies were stationed. Following the old emperor’s death some of these troops had attempted a revolt with the intention of placing his brother on the throne. This had been swiftly put down and Irene thereafter had set out to purge the army. Her willingness to dismember the empire’s forces; removing capable commanders and disbanding troops whose loyalty was suspect, sparked widespread mutiny and rendered the imperial frontiers vulnerable to invasion. The highly capable Abbasid prince Harun al Rashid led an invasion in 782 which swept into Byzantine territory meeting with little opposition and indeed many of the imperial forces defected to the enemy. Irene was forced to buy peace from the future Caliph.

For those who were dismayed by the Empress’ actions, her son Constantine was an obvious focal point. The armies in the east remained staunchly iconoclast and those in the capital who longed to overturn Irene’s reforms therefore had a ready source of manpower to call upon and a suitable figurehead in the form of Constantine. Matters came to a head in 790 when Irene attempted to seize supreme power for herself; flinging her son into prison when a plot by leading iconoclasts for her overthrow and exile came to light. With Constantine behind bars, Irene demanded an oath of loyalty from all of her armies. This galvanised the eastern opposition who marched on the capital and restored Constantine to his throne. Irene, deposed, was left to stew in the confinement of her palace and plot her revenge.

She did not have long to wait. Within two years her son had shown himself to be hopelessly incapable of government and had her recalled. For the next five years mother and son resumed their uneasy partnership but Constantine through military blunders and an ill-advised divorce steadily lost support until finally Irene felt safe enough to make her move. For a second time Constantine was seized and imprisoned but this time his mother was taking no chances and ordered her son blinded. The punishment was carried out, in the very room in which he had been born, with such brutality as to cause his death. It was a crime which sent a shockwave through the empire and it left Irene as empress and sole ruler. (shown left depicted as such)

She did not have long to wait. Within two years her son had shown himself to be hopelessly incapable of government and had her recalled. For the next five years mother and son resumed their uneasy partnership but Constantine through military blunders and an ill-advised divorce steadily lost support until finally Irene felt safe enough to make her move. For a second time Constantine was seized and imprisoned but this time his mother was taking no chances and ordered her son blinded. The punishment was carried out, in the very room in which he had been born, with such brutality as to cause his death. It was a crime which sent a shockwave through the empire and it left Irene as empress and sole ruler. (shown left depicted as such)Her actions had an unintended and far reaching consequence. Three years later as Pope Leo III was contemplating how best to honour and reward his champion and saviour; Charles King of the Franks, the son

of Pepin the Short, he could observe that the title of Emperor of the Romans was conveniently vacant, for the Pope did not recognise the right of a woman to hold that title.

On Christmas Day 800 therefore, since Irene remained the sole ruler in Constantinople, Leo was able to confer the imperial title upon Charles; whose efforts in the cause of Christianity had gone a considerable way towards the restoration of a western empire.

In Constantinople such presumption seemed ludicrous. Who was this semi-literate barbarian who laid claim to the legacy of Augustus and Constantine? Nevertheless Irene had continued to alienate her subjects. Her continuing appeasement of the now-Caliph al-Rashid with ever greater payments of protection money and her increasingly desperate attempts to buy her subjects’ affections through unaffordable tax breaks, convinced many that her deposition would be vital for the future wellbeing of the empire. When two years after his coronation Irene began seriously to entertain proposals of marriage from Charlemagne; an act which would unite the rival eastern and western claimants to the Empire of the Romans and place the Frankish ruler on the throne of Byzantium, she had at last gone too far. Her own officials convened an assembly in the hippodrome and declared her deposed. She was exiled to an island in the Marmara and died a year later.

Irene has gone down in history as a wicked schemer, driven by ambition to commit the worst crime any mother could commit; the cold-blooded murder of her own child. In the iconoclastic struggle however, she struck the decisive, if not the final blow. Although the findings of the council she had convened in Nicaea in 787, anathemitizing the writings of the iconoclasts, would be challenged anew within a decade of her death and ultimately overturned, it would in the end stand as the final word on the veneration of icons.

The present Canon decrees that all the false writings which the iconomachists composed against the holy icons and which are flimsy as children’s toys, and as crazy as the raving and insane bacchantes — those women who used to dance drunken at the festival of the tutelar of intoxication Dionysus — all those writings, I say, must be surrendered to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, to be put together with the other books by heretics — in such a place, that is to say, that no one will ever be able to take them therefrom with a view to reading them. As for anyone who should hide them, with a view to reading them himself or providing them for others to read, if he be a bishop, a presbyter, or a deacon, let him be deposed from office; but if he be a layman or a monk, let him be excommunicated.

Leo III crowns Charlemagne The Seventh Ecumenical Council in full

Leo III crowns Charlemagne The Seventh Ecumenical Council in fullhttp://www.intratext.com/IXT/ENG0835/__P4V.HTM

Some good sites featuring iconographic art

http://www.mountathos.gr/active.aspx?mode=en{2aee45f1-c81e-4f0c-9cf9-c2efe471cfd1}View

http://econcept.dk/icon/dox.html

Published on January 29, 2013 03:21

January 22, 2013

Bish Bash Bosh – Ancient Artillery Part Two

These angry little fellas are making use of a simple tension catapult in order to propel themselves at their smug green nemesis. As we saw in Part One however, engineers in the classical world had devised a means of harnessing the energy held in tightly coiled bundles of rope made from hair or sinew in order to increase the power of a catapult significantly. These torsion catapults had reached the pinnacle of their development by the end of the First Century AD and the armies of Trajan would have terrorised the defenders of Sarmizegethusa and Ctesiphon with the ultimate in torsion artillery technology. The cheiroballista was built on the same lines as the earlier examples but its frame was constructed from iron and the torsion bundles or skeins were protected from the elements by being housed in metal cannisters. This more robust weapon was also smaller and more mobile than the equivalent wooden examples. We can see here depicted on Trajan’s column a cheiroballista being transported on a cart.

Optimising the design of such machines was dependant on a thorough understanding of the mathematical relationship between the diameter of the torsion spring, the length of the bow arms and the weight or length of the projectile. Men such as Trajan’s chief engineer Apollodorus of Damascus, who famously constructed a magnificent stone bridge across the Danube, were well versed in such reckoning. By the late Roman Empire however, such knowledge was beginning to be lost and masterpieces of the siege engineer’s craft such as the cheiroballista were disappearing from the battlefield.

Instead the torsion artillery of choice for the Roman army was a brute of a siege engine known as the onager; ‘wild ass’, so named for its vicious kick.

The onager was a simpler device possessing just a single arm as opposed to the two arms of the ballistae. The throwing arm was held upright in a skein stretched between two beams, the tension of which could be adjusted with a crank mechanism. A second crank mechanism allowed the throwing arm to be pulled back and a slip-hook mechanism then allowed the missile to be released from a sling suspended from the end of the throwing arm.

Nevertheless there is evidence for the continuing use and continuing deadly accuracy of bolt throwing ballistae in the late Roman and early Byzantine world. Ammianus Marcellinus; writing in the Fourth Century AD describes both one and two armed torsion catapults being used in the defence of Amida on the Tigris and two hundred years later Procopius describes ballistae being used to defend Rome from the Goths.

In the late Sixth Century the Avars; terrifying horsemen from the Eastern Steppe, began raiding across the Danube into the Balkans. These invaders brought with them a new type of siege engine originally developed in China. The trebuchet had arrived. These early examples were traction trebuchets, powered by men heaving in unison on ropes to pull the throwing arm of the machine up and over the top of the frame and release the missile from the sling. At the siege of Thessalonika in 597 AD these machines, which he refers to as petroboles; stone throwers, are described in some detail by the Archbishop John who was an eye witness.

These petroboles were tetragonal and rested on broader bases, tapering to narrow extremities. Attached to them were thick cylinders well clad in iron at the ends, and there were nailed to them timbers like beams from a large house. These timbers had the slings from the back and from the front strong ropes, by which, pulling down and releasing the sling, they propel the stones up high and with a loud noise. And on being fired they sent up many great stones so that neither earth nor human constructions could bear the impacts. They also covered those tetragonal petroboles with boards on three sides only, so that those inside firing them might not be wounded with arrows by those on the walls. And since one of these, with its boards, had been burned to a char by a flaming arrow, they returned, carrying away the machines. On the following day they again brought these Petroboles covered with freshly skinned hides and with the boards, and placing them closer to the walls, shooting, they hurled mountains and hills against us. For what else might one term these extremely large stones?

Medieval Weapons: An Illustrated History of their Impact By Kelly De Vries & Robert D. Smith Copyright 2007 by ABC-CLIO, Inc.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/15778880/Medieval-Weapons-An-Illustrated-History-of-Their-Impacttqwdarksiderg

Smashing the Bridge between Roman and Medieval Artillery: The Onager by Brian Pangburnhttp://bit.csc.lsu.edu/~pangburn/onager.pdfAmmianus Marcellinus on Roman artilleryhttp://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Ammian/23*.htmlAmmianus Marcellinus on the siege of Amida

http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/ammianus_19_book19.htm

More on catapults

http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/war/CatapultTypes.htm

Published on January 22, 2013 00:36

January 12, 2013

Iconoclasm – a Byzantine Tragedy – Part One

Byzantium today is renowned for two things; its brutal politics and its artistic legacy, in particular its religious art. It was an empire plagued by intrigues and obsessed with icons. During two turbulent periods in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries however, the Byzantines turned against and wilfully destroyed these precious and venerated objects. The repercussions from these destructive movements went beyond the spiritual life of the Empire to have a profound impact on both its politics and its relations with the west.

The Arab conquests of the Seventh Century had seen vast tracts of formerly Christian territory come under Islamic rule. Of the four Patriarchates of Eastern Christendom, three; Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria lay within the territories of the Umayyad Caliphate. As ‘people of the book’, Christians living under Arab rule were generally tolerated but under the reign of the austere and pious Caliph Umar II interference with Christian practices which were offensive to Islam had increased. In 723 AD Umar's successor Yazid had issued a decree that all holy images in Christian churches within his territories should be destroyed and his brother Hisham who succeeded Yazid upon his death in 724 took an equally hard line. This reaction of the Muslim rulers against what they saw as flagrant idolatry also struck a chord with many Christians, fuelling a growing movement in the east which would sweep across the Byzantine Empire with profound consequences.

Iconoclasm as it is known to posterity; literally the smashing of icons, was a policy first adopted by Emperor Leo III in response to the growing cult of icon worship amongst his subjects. The emperor was of Syrian descent and as such was likely to have Monophysite leanings, seeing Christ as wholly divine with no mortal aspect. He may also have been influenced by being exposed to Islamic and Jewish thought. He therefore took a dim view of the widespread practice among his fellow Christians of openly worshipping icons of Christ, the Virgin and the saints; treating these inanimate representations of the divine as divine objects in their own right. For Leo and those who shared his views this was a clear violation of the commandment which forbade bowing down before graven images. In 726 he made his feelings clear by ordering the violent and shocking destruction of Constantinople’s largest and most beloved icon of Christ which was displayed above the main gate of the imperial palace.