Simon B. Jones's Blog: Slings and arrows, page 3

December 23, 2014

Shackleton's forgotten men - The Ross Sea Party - Part One

I thought I should post something suitably wintery for the last post of 2014, which is a double bill. So turn up the heating, make a cup of tea and enjoy this less well known story of polar endurance.

The tale of Sir Ernest Shackleton's remarkable journey of survival following the wreck of his ship Endurance has assumed legendary status and is celebrated as a triumph over adversity. Less well known however is the story of the men who Shackleton sent to the Ross Sea, on the far side of the Antarctic continent. The Ross Sea Party were charged with laying supply depots along the last 365 miles of the route of Shackleton's doomed Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. This effort was crucial to the success of the whole enterprise, since the men of Shackleton's party, making landfall from the Weddell Sea and proceeding via the South Pole, would not be able to carry sufficient supplies to make it all the way across.

The 28 men of the expedition set out from Hobart on Christmas Eve 1914 aboard the SY Aurora, which Shackleton had purchased from fellow Antarctic explorer Douglas Mawson.

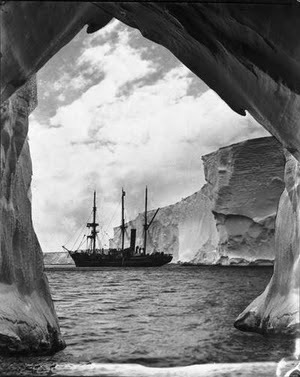

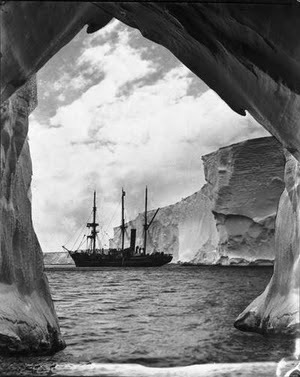

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

The Aurora, under the command of Aeneas Mackintosh, made her way to Ross Island and anchored off Cape Evans, from where Scott had launched his fatal attempt on the Pole. Here Scott's hut would provide a base for the shore party of 12 men. Across the ice at Hut Point; the closest point of Ross Island to the main land at the head of McMurdo Sound, a second hut built by Scott on his earlier 1902 expedition provided a base from which expeditions inland could set out.

The 35 year old Mackintosh was no stranger to polar exploration. He had sailed with Shackleton before on his unsuccessful 1909 expedition, on which Shackleton had reached 88 degrees south before turning back. He had earned a reputation for fortitude, not least after losing an eye in a shipboard accident, as well as for being something of a risk taker.

Mackintosh, believing wrongly that Shackleton could be setting out to make the crossing already, immediately set to the task of establishing depots. Supplies were transferred to Hut Point and from there three sledging expeditions set out in January 1915 with the objective of establishing two depots, which would provide the bare minimum of supplies required by Shackleton.

The operation was beset by difficulties. One party were thwarted by the breakdown of their motorised sledge, whilst the other two parties led by Mackintosh and experienced polar explorer Ernest Joyce made their way across the Great Ice Barrier to lay depots at 79 and 80 degrees south. Some of the supplies had to be abandoned along the way, whilst the inexperienced crews struggled in heavy snow and suffered from frost bite.

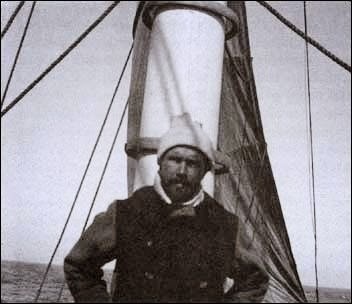

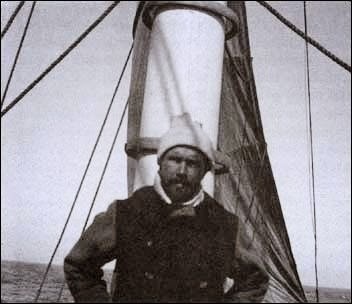

Aeneas Mackintosh - commander of the Ross Sea Party

Aeneas Mackintosh - commander of the Ross Sea Party

Joyce and Mackintosh had quarrelled over the details of the expedition. Joyce was the most experienced of the party, having served with both Scott and Shackleton. He attempted to claim that he had been given authority over land operations by Shackleton and advised against pushing the dogs too hard. He would later write an account in which he was highly critical of Mackintosh's leadership.

The return trip was particularly miserable and of the ten dogs that had set out all perished from exhaustion as they struggled through the deep snow. Blizzards confined the men to their tents at times and with rations running short they were forced to raid the depots they had established. This despondent entry from Mackintosh's diary for 25th February sums up the hardships of the journey.

Outside is a scene of chaos. The snow, whirling along with the wind, obliterates everything. The dogs are completely buried, and only a mound with a ski sticking up indicates where the sledge is. We long to be off, but the howl of the wind shows how impossible it is. The sleeping-bags are damp and sticky, so are our clothes. Fortunately, the temperature is fairly high and they do not freeze. One of the dogs gave a bark and Joyce went out to investigate. He found that Major, feeling hungry, had dragged his way to Joyce's ski and eaten off the leather binding. Another dog has eaten all his harness, canvas, rope, leather, brass, and rivets. I am afraid the dogs will not pull through; they all look thin and these blizzards do not improve matters. . . . We have a week's provisions and one hundred and sixty miles to travel. It appears that we will have to get another week's provisions from the depot, but don't wish it. Will see what luck to-morrow.

On March 25th 1915 the exhausted and frost bitten Mackintosh and his companions made it back to Hut Point and the safety of Scott's hut. Here they and the other men of the sledging parties would remain until mid June, when the sea ice was once more thick enough for them to make the journey across the ice and rejoin their companions at Cape Evans. They supplemented their meagre rations with seal meat and kept warm by burning seal blubber. The thick smoke from the blubber fire and lamps ensured that the men's skin was soon blackened with a thick layer of oily grime. When at last Mackintosh made it back to Cape Evans he was in for a shock, for the Aurora was gone.

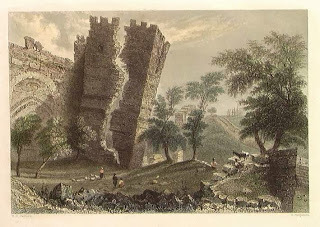

Scott's hut at Cape Evans In Mackintosh's absence the Aurora had been under the command of First Officer Joseph Stenhouse. After exploring various possible anchorages around McMurdo Sound, the Aurora had been anchored to the shore off Cape Evans and became encased in the sea ice. Cape Evans was an exposed anchorage but Shackleton had advised against anchoring further inshore due to the risk of the ship becoming trapped in the ice as Scott's ship Discovery had been. The crew took what they thought to be adequate precautions, cementing anchors into the ground and securing the ship with 'enough hawsers to hold a battleship.'

Scott's hut at Cape Evans In Mackintosh's absence the Aurora had been under the command of First Officer Joseph Stenhouse. After exploring various possible anchorages around McMurdo Sound, the Aurora had been anchored to the shore off Cape Evans and became encased in the sea ice. Cape Evans was an exposed anchorage but Shackleton had advised against anchoring further inshore due to the risk of the ship becoming trapped in the ice as Scott's ship Discovery had been. The crew took what they thought to be adequate precautions, cementing anchors into the ground and securing the ship with 'enough hawsers to hold a battleship.'

On 6th May a blizzard blew up and the forces of nature made a mockery of their preparations. With a sound like gunfire the shore hawsers snapped and a large ice flow broke away from the shore, carrying the entrapped ship with it. Ten of the shore party were left stranded in Scott's hut, with two of their number and much of their supplies including all their spare clothing still on the ship. It was not until the blizzard abated the next day that they realised the ship had gone.

Aboard the Aurora there was consternation. With the crew thinking themselves settled in for the winter, the engines had been partially dismantled for maintenance. These were now hurriedly pressed back into service but the ship was unable to break free of the ice flow in which she was trapped. So began the Aurora's long drift. Held fast in the ice, she drifted north with the floes, whilst Stenhouse and his men could only hope for the best and prepare for the worst. There was every chance that the ship could share the fate of Endurance on the far side of the continent and be crushed in the ice. Sledges and supplies were prepared in case the crew had to abandon ship and make for landfall on the Antarctic coast. They had plentiful supplies of food, supplemented by hunting seals and penguins on the ice, but fresh water had to be collected by gathering snow. Stenhouse toyed with the idea of an expedition to an iceberg he could see in the distance but gave up the scheme. Throughout he kept his men busy and kept their morale up. From his log it is clear that the fate of the men left behind was always on his mind. Stenhouse's hope was that the ship would be freed from the ice and that he would be able to head back to Cape Evans.

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

As the ship drifted further this became an increasingly forlorn hope. The movement of the ice was a cause for both hope and fear. This entry from Stenhouse's log for 22nd July 1915 shows how the situation changed constantly.

Ship in bad position in newly frozen lane, with bow and stern jammed against heavy floes; heavy strain with much creaking and groaning. 8 a.m.—Called all hands to stations for sledges, and made final preparations for abandoning ship. Allotted special duties to several hands to facilitate quickness in getting clear should ship be crushed. Am afraid the ship's back will be broken if the pressure continues, but cannot relieve her. 2 p.m.—Ship lying easier. Poured Sulphuric acid on the ice astern in hopes of rotting crack and relieving pressure on stern-post, but unsuccessfully. Very heavy pressure on and around ship (taking strain fore and aft and on starboard quarter). Ship, jumping and straining and listing badly. 10 p.m.—Ship has crushed her way into new ice on starboard side and slewed aslant lane with stern-post clear of land-ice. 12 p.m.—Ship is in safer position; lanes opening in every direction.

The polar winter wore on, with the ship battered by the grinding ice floes and blizzards. The rudder was completely destroyed by the ice and the mizzen mast was carried away by the wind. By September the return of the sun and warmer temperatures once more gave cause for hope that the ship would be freed from the ice. Stenhouse's entry for 22nd September finds him in a better mood. He notes that the Aurora has drifted 705 miles from Cape Evans and looks on the bright side that the experience will serve the cause of human knowledge about the movement of the polar ice. As winter turned to summer, open water was often sighted in the distance but the ship remained trapped. The wireless aerials occasionally picked up snatches of weather reports from the radio station at Macquarie Island over 800 miles away but they were unable to make contact. Christmas came and went and as the sun began to dip below the horizon again, the crew of the Aurora faced the grim possibility of another winter trapped in the ice.

This map from the Daily Telegraph from 1916 ponders the whereabouts of Shackleton and the Ross Sea Party

This map from the Daily Telegraph from 1916 ponders the whereabouts of Shackleton and the Ross Sea Party

Meanwhile at Cape Evans, the ten members of the shore party were making the best of it and remained committed to carrying out the task allotted to them. Throughout September supplies were moved across the ice from Cape Evans to Hut Point with the intention of setting out to lay depots at 81, 82 and 83 degrees south, the last being at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier, which Shackleton's party were expected to descend on their journey from the Pole. On 9th October 9 men set out dragging between them three sledges loaded with 2000lbs of supplies and equipment, which they intended to drag to the base depot at Minna Bluff. It was hard going and Joyce prevailed upon Mackintosh to divide the loads and press on in two teams. Between October and December the men of the Ross Sea Party made three journeys between Hut Point and Minna Bluff, a return journey of 140 miles. They succeeded in depositing almost 3000lbs of stores ready to establish the depots further to the south. Little did they know it but all of their efforts were already in vain. On 27th October 1915, with Endurance holed and sinking, Shackleton had finally given the order to abandon ship and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was over. For those charged with ensuring his success on the far side of the continent and those aboard the Aurora, the mission went on.

To be continued.

A merry Christmas and a happy New Year to all my readers.

The tale of Sir Ernest Shackleton's remarkable journey of survival following the wreck of his ship Endurance has assumed legendary status and is celebrated as a triumph over adversity. Less well known however is the story of the men who Shackleton sent to the Ross Sea, on the far side of the Antarctic continent. The Ross Sea Party were charged with laying supply depots along the last 365 miles of the route of Shackleton's doomed Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. This effort was crucial to the success of the whole enterprise, since the men of Shackleton's party, making landfall from the Weddell Sea and proceeding via the South Pole, would not be able to carry sufficient supplies to make it all the way across.

The 28 men of the expedition set out from Hobart on Christmas Eve 1914 aboard the SY Aurora, which Shackleton had purchased from fellow Antarctic explorer Douglas Mawson.

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913The Aurora, under the command of Aeneas Mackintosh, made her way to Ross Island and anchored off Cape Evans, from where Scott had launched his fatal attempt on the Pole. Here Scott's hut would provide a base for the shore party of 12 men. Across the ice at Hut Point; the closest point of Ross Island to the main land at the head of McMurdo Sound, a second hut built by Scott on his earlier 1902 expedition provided a base from which expeditions inland could set out.

The 35 year old Mackintosh was no stranger to polar exploration. He had sailed with Shackleton before on his unsuccessful 1909 expedition, on which Shackleton had reached 88 degrees south before turning back. He had earned a reputation for fortitude, not least after losing an eye in a shipboard accident, as well as for being something of a risk taker.

Mackintosh, believing wrongly that Shackleton could be setting out to make the crossing already, immediately set to the task of establishing depots. Supplies were transferred to Hut Point and from there three sledging expeditions set out in January 1915 with the objective of establishing two depots, which would provide the bare minimum of supplies required by Shackleton.

The operation was beset by difficulties. One party were thwarted by the breakdown of their motorised sledge, whilst the other two parties led by Mackintosh and experienced polar explorer Ernest Joyce made their way across the Great Ice Barrier to lay depots at 79 and 80 degrees south. Some of the supplies had to be abandoned along the way, whilst the inexperienced crews struggled in heavy snow and suffered from frost bite.

Aeneas Mackintosh - commander of the Ross Sea Party

Aeneas Mackintosh - commander of the Ross Sea PartyJoyce and Mackintosh had quarrelled over the details of the expedition. Joyce was the most experienced of the party, having served with both Scott and Shackleton. He attempted to claim that he had been given authority over land operations by Shackleton and advised against pushing the dogs too hard. He would later write an account in which he was highly critical of Mackintosh's leadership.

The return trip was particularly miserable and of the ten dogs that had set out all perished from exhaustion as they struggled through the deep snow. Blizzards confined the men to their tents at times and with rations running short they were forced to raid the depots they had established. This despondent entry from Mackintosh's diary for 25th February sums up the hardships of the journey.

Outside is a scene of chaos. The snow, whirling along with the wind, obliterates everything. The dogs are completely buried, and only a mound with a ski sticking up indicates where the sledge is. We long to be off, but the howl of the wind shows how impossible it is. The sleeping-bags are damp and sticky, so are our clothes. Fortunately, the temperature is fairly high and they do not freeze. One of the dogs gave a bark and Joyce went out to investigate. He found that Major, feeling hungry, had dragged his way to Joyce's ski and eaten off the leather binding. Another dog has eaten all his harness, canvas, rope, leather, brass, and rivets. I am afraid the dogs will not pull through; they all look thin and these blizzards do not improve matters. . . . We have a week's provisions and one hundred and sixty miles to travel. It appears that we will have to get another week's provisions from the depot, but don't wish it. Will see what luck to-morrow.

On March 25th 1915 the exhausted and frost bitten Mackintosh and his companions made it back to Hut Point and the safety of Scott's hut. Here they and the other men of the sledging parties would remain until mid June, when the sea ice was once more thick enough for them to make the journey across the ice and rejoin their companions at Cape Evans. They supplemented their meagre rations with seal meat and kept warm by burning seal blubber. The thick smoke from the blubber fire and lamps ensured that the men's skin was soon blackened with a thick layer of oily grime. When at last Mackintosh made it back to Cape Evans he was in for a shock, for the Aurora was gone.

Scott's hut at Cape Evans In Mackintosh's absence the Aurora had been under the command of First Officer Joseph Stenhouse. After exploring various possible anchorages around McMurdo Sound, the Aurora had been anchored to the shore off Cape Evans and became encased in the sea ice. Cape Evans was an exposed anchorage but Shackleton had advised against anchoring further inshore due to the risk of the ship becoming trapped in the ice as Scott's ship Discovery had been. The crew took what they thought to be adequate precautions, cementing anchors into the ground and securing the ship with 'enough hawsers to hold a battleship.'

Scott's hut at Cape Evans In Mackintosh's absence the Aurora had been under the command of First Officer Joseph Stenhouse. After exploring various possible anchorages around McMurdo Sound, the Aurora had been anchored to the shore off Cape Evans and became encased in the sea ice. Cape Evans was an exposed anchorage but Shackleton had advised against anchoring further inshore due to the risk of the ship becoming trapped in the ice as Scott's ship Discovery had been. The crew took what they thought to be adequate precautions, cementing anchors into the ground and securing the ship with 'enough hawsers to hold a battleship.'On 6th May a blizzard blew up and the forces of nature made a mockery of their preparations. With a sound like gunfire the shore hawsers snapped and a large ice flow broke away from the shore, carrying the entrapped ship with it. Ten of the shore party were left stranded in Scott's hut, with two of their number and much of their supplies including all their spare clothing still on the ship. It was not until the blizzard abated the next day that they realised the ship had gone.

Aboard the Aurora there was consternation. With the crew thinking themselves settled in for the winter, the engines had been partially dismantled for maintenance. These were now hurriedly pressed back into service but the ship was unable to break free of the ice flow in which she was trapped. So began the Aurora's long drift. Held fast in the ice, she drifted north with the floes, whilst Stenhouse and his men could only hope for the best and prepare for the worst. There was every chance that the ship could share the fate of Endurance on the far side of the continent and be crushed in the ice. Sledges and supplies were prepared in case the crew had to abandon ship and make for landfall on the Antarctic coast. They had plentiful supplies of food, supplemented by hunting seals and penguins on the ice, but fresh water had to be collected by gathering snow. Stenhouse toyed with the idea of an expedition to an iceberg he could see in the distance but gave up the scheme. Throughout he kept his men busy and kept their morale up. From his log it is clear that the fate of the men left behind was always on his mind. Stenhouse's hope was that the ship would be freed from the ice and that he would be able to head back to Cape Evans.

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913

SY Aurora photographed by Frank Hurley in 1913As the ship drifted further this became an increasingly forlorn hope. The movement of the ice was a cause for both hope and fear. This entry from Stenhouse's log for 22nd July 1915 shows how the situation changed constantly.

Ship in bad position in newly frozen lane, with bow and stern jammed against heavy floes; heavy strain with much creaking and groaning. 8 a.m.—Called all hands to stations for sledges, and made final preparations for abandoning ship. Allotted special duties to several hands to facilitate quickness in getting clear should ship be crushed. Am afraid the ship's back will be broken if the pressure continues, but cannot relieve her. 2 p.m.—Ship lying easier. Poured Sulphuric acid on the ice astern in hopes of rotting crack and relieving pressure on stern-post, but unsuccessfully. Very heavy pressure on and around ship (taking strain fore and aft and on starboard quarter). Ship, jumping and straining and listing badly. 10 p.m.—Ship has crushed her way into new ice on starboard side and slewed aslant lane with stern-post clear of land-ice. 12 p.m.—Ship is in safer position; lanes opening in every direction.

The polar winter wore on, with the ship battered by the grinding ice floes and blizzards. The rudder was completely destroyed by the ice and the mizzen mast was carried away by the wind. By September the return of the sun and warmer temperatures once more gave cause for hope that the ship would be freed from the ice. Stenhouse's entry for 22nd September finds him in a better mood. He notes that the Aurora has drifted 705 miles from Cape Evans and looks on the bright side that the experience will serve the cause of human knowledge about the movement of the polar ice. As winter turned to summer, open water was often sighted in the distance but the ship remained trapped. The wireless aerials occasionally picked up snatches of weather reports from the radio station at Macquarie Island over 800 miles away but they were unable to make contact. Christmas came and went and as the sun began to dip below the horizon again, the crew of the Aurora faced the grim possibility of another winter trapped in the ice.

This map from the Daily Telegraph from 1916 ponders the whereabouts of Shackleton and the Ross Sea Party

This map from the Daily Telegraph from 1916 ponders the whereabouts of Shackleton and the Ross Sea PartyMeanwhile at Cape Evans, the ten members of the shore party were making the best of it and remained committed to carrying out the task allotted to them. Throughout September supplies were moved across the ice from Cape Evans to Hut Point with the intention of setting out to lay depots at 81, 82 and 83 degrees south, the last being at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier, which Shackleton's party were expected to descend on their journey from the Pole. On 9th October 9 men set out dragging between them three sledges loaded with 2000lbs of supplies and equipment, which they intended to drag to the base depot at Minna Bluff. It was hard going and Joyce prevailed upon Mackintosh to divide the loads and press on in two teams. Between October and December the men of the Ross Sea Party made three journeys between Hut Point and Minna Bluff, a return journey of 140 miles. They succeeded in depositing almost 3000lbs of stores ready to establish the depots further to the south. Little did they know it but all of their efforts were already in vain. On 27th October 1915, with Endurance holed and sinking, Shackleton had finally given the order to abandon ship and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was over. For those charged with ensuring his success on the far side of the continent and those aboard the Aurora, the mission went on.

To be continued.

A merry Christmas and a happy New Year to all my readers.

Published on December 23, 2014 05:04

December 2, 2014

Dreamers and Schemers - the search for longitude

The final plate of Hogarth's A Rake's Progress from 1735 depicts a madhouse, in which the protagonist has finally found himself after squandering his riches and losing his mind. In the background of the scene is a detail I had not noticed before, until my attention was drawn to it at the excellent Ships Clocks and Stars exhibition currently running at the Maritime Museum. On the back wall of the scene, a deranged inmate is puzzling over solutions to the great challenge of the age; how to accurately determine longitude at sea.

A Rake's Progress - 8th plate 1735 Such is the way in which the search for longitude was viewed by satirists such as Hogarth; as a fools quest. The vast sums in prize money promised by the Board of Longitude, formed in 1714, were a veritable pot of gold that tempted dreamers and schemers to devise solutions to the problem. In the coffee houses of London schemes for solving the longitude challenge were a popular topic of conversation and the more outlandish proponents were fair game for lampooning.

A Rake's Progress - 8th plate 1735 Such is the way in which the search for longitude was viewed by satirists such as Hogarth; as a fools quest. The vast sums in prize money promised by the Board of Longitude, formed in 1714, were a veritable pot of gold that tempted dreamers and schemers to devise solutions to the problem. In the coffee houses of London schemes for solving the longitude challenge were a popular topic of conversation and the more outlandish proponents were fair game for lampooning.

No man was a more popular target for derision than William Whiston. Far from being a crackpot, Whiston succeeded to the Cambridge professorship of no less a luminary than Isaac Newton in 1702. Nevertheless he did hold unorthodox religious beliefs and was fascinated by miracles and prophecies. He caused alarm in 1736 by claiming that a comet was about to hit the earth. His other enduring fascination was with the problem of longitude and he was behind a number of proposals to the board.

Whiston's first proposal was as straightforward as it was impractical. Along with mathematician Humphrey Ditton, Whiston proposed using a system of anchored rocket ships around the globe. These ships, at positions of known longitude, would send up rockets at regular intervals. Ship's captains, observing the explosion of the rocket, would calculate their position based upon the time it took for the sound of the rocket to reach them. The admiralty, it need hardly be said, were unimpressed. Where were the funds and the thousands of men required to crew these ships to be found, they demanded. And how long would it be before they mutinied out of sheer boredom?

Halley's chart of magnetic variation

Halley's chart of magnetic variation

Unperturbed, Whiston next proposed using magnetism to find longitude. By producing charts showing the lines of magnetic variation across the globe, it would be possible for ship's captains to compare true north, established through solar observation, with the magnetic north determined by their compasses and then refer to the chart to find their longitude. Indeed these lines of magnetic variation had already been charted in the Atlantic by Edmund Halley during his command of HMS Paramour in 1698-99 on the first ever purely scientific naval mission. Whiston received approval from the board of longitude to produce a chart of magnetic variation for southern England in 1719. Unfortunately for Whiston this idea too was ultimately doomed, for the variation in the earth's magnetic field would render any charts produced obsolete within a matter of years, requiring the entire painstaking process to begin again. The board eventually paid him £500 for his trouble.

In 1730 Whiston brought forth another proposal, this time based upon observing the regular motion of the moons of Jupiter. By noting the local time of an eclipse of one of the four moons as it passed behind or in front of the planet and comparing it to a table of the known times based on Greenwich, it would be possible to determine longitude. Once again there was nothing wrong with the theory, Galileo himself had suggested the use of Jupiter's moons as a celestial timepiece and it works perfectly well on land. The practicality however of observing the moons of Jupiter from the deck of a ship in anything other than perfect conditions, once again condemned the idea to the dustbin of longitude history. Whiston was not unaware of the difficulties and suggested using up to 7 telescopes in combination to ensure that the observer could keep Jupiter in their sights.

Whiston's unorthodox religious views eventually caused him to fall from establishment favour and he spent the rest of his life engaging in increasingly outlandish theological speculation. He died in 1752.

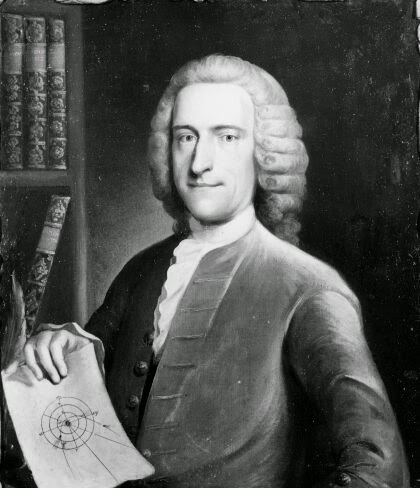

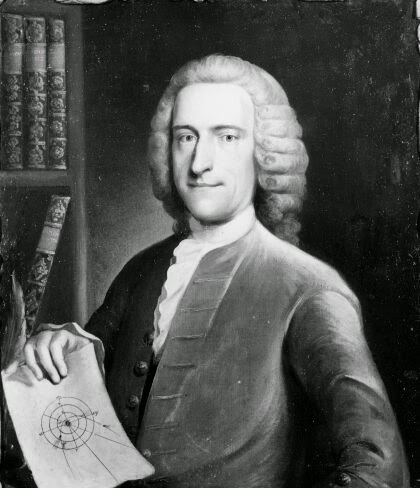

Whiston brandishes another cunning plan Ultimately the solution to the longitude problem boiled down to two methods; lunar distance and marine chronometers. The lunar distance method, couched as it was in mathematics and astronomy, was more attractive to the gentleman scientists of the Royal Society, who struggled to overcome their disappointment that 'Harrison's blasted watch', as third astronomer royal James Bradley described it, could provide a complete solution. In 1761 the Royal Society dispatched astronomer Neville Maskelyne to the island of St Helena to observe the transit of Venus. During the voyage Maskelyne was keen to try out the ideas of one Tobias Mayer. Mayer was a remarkable individual. Having come from poor and humble beginnings, he was entirely self taught and published his first mathematical work when he was just eighteen, subsequently obtaining work as a mapmaker. By the 1750's Mayer was the director of Gottingen observatory and had turned his mind to the issue of longitude. Mayer focussed on the lunar distance method, which allowed longitude to be determined by observing the angle between the moon and a chosen star, typically Regulus. By comparing the observed angle with tables compiled from Mayer's exacting observations, the mariner would be able to establish their precise local time and thereby their longitude. Mayer sent his tables to the Board of Longitude in 1755. They were assessed by Bradley, who had succeeded the great Edmund Halley in 1742, and were found to be most accurate. Bradley continued to build on Mayer's work, compiling further tables based on Greenwich. He was assisted in this work by Charles Mason, best known for his later partnership with Jeremiah Dixon in establishing the line that bears their names.

Whiston brandishes another cunning plan Ultimately the solution to the longitude problem boiled down to two methods; lunar distance and marine chronometers. The lunar distance method, couched as it was in mathematics and astronomy, was more attractive to the gentleman scientists of the Royal Society, who struggled to overcome their disappointment that 'Harrison's blasted watch', as third astronomer royal James Bradley described it, could provide a complete solution. In 1761 the Royal Society dispatched astronomer Neville Maskelyne to the island of St Helena to observe the transit of Venus. During the voyage Maskelyne was keen to try out the ideas of one Tobias Mayer. Mayer was a remarkable individual. Having come from poor and humble beginnings, he was entirely self taught and published his first mathematical work when he was just eighteen, subsequently obtaining work as a mapmaker. By the 1750's Mayer was the director of Gottingen observatory and had turned his mind to the issue of longitude. Mayer focussed on the lunar distance method, which allowed longitude to be determined by observing the angle between the moon and a chosen star, typically Regulus. By comparing the observed angle with tables compiled from Mayer's exacting observations, the mariner would be able to establish their precise local time and thereby their longitude. Mayer sent his tables to the Board of Longitude in 1755. They were assessed by Bradley, who had succeeded the great Edmund Halley in 1742, and were found to be most accurate. Bradley continued to build on Mayer's work, compiling further tables based on Greenwich. He was assisted in this work by Charles Mason, best known for his later partnership with Jeremiah Dixon in establishing the line that bears their names.

Mr Irwin's marine chair undergoes testing So off sailed Maskelyne aboard the Prince Henry bound for St Helena, putting Mayer's methods to practical use and becoming in the process an advocate of the lunar distance method. Two years later he was dispatched to Barbados aboard HMS Princess Louisa. He took with him Harrison's final chronometer H4, the culmination of 30 years of work, the accuracy of which would be compared directly with the lunar distance method. Maskelyne also took with him Mr Christopher Irwin's marine chair for testing. This gimballed chair was designed to allow astronomical observations to be made more easily from the pitching and rolling deck of a ship. Maskelyne found the chair to be completely useless. On arrival, Maskelyne would determine the longitude of Bridgetown using Jupiter's satellites and see which of the rival methods came closest. Harrison's chronometer was found to be accurate to within 10 miles, whereas the lunar distance calculations were only within 30. Maskelyne, who succeeded to the post of astronomer royal upon his return, has been somewhat vilified by posterity for his opposition to Harrison's clocks. Whilst Harrison is celebrated today as the man who solved the longitude problem, in reality the high cost of producing accurate marine chronometers ensured that both methods would continue to be employed for finding longitude at sea. Maskelyne oversaw the completion of the first Nautical Almanac containing lunar tables for determining longitude in 1766.

Mr Irwin's marine chair undergoes testing So off sailed Maskelyne aboard the Prince Henry bound for St Helena, putting Mayer's methods to practical use and becoming in the process an advocate of the lunar distance method. Two years later he was dispatched to Barbados aboard HMS Princess Louisa. He took with him Harrison's final chronometer H4, the culmination of 30 years of work, the accuracy of which would be compared directly with the lunar distance method. Maskelyne also took with him Mr Christopher Irwin's marine chair for testing. This gimballed chair was designed to allow astronomical observations to be made more easily from the pitching and rolling deck of a ship. Maskelyne found the chair to be completely useless. On arrival, Maskelyne would determine the longitude of Bridgetown using Jupiter's satellites and see which of the rival methods came closest. Harrison's chronometer was found to be accurate to within 10 miles, whereas the lunar distance calculations were only within 30. Maskelyne, who succeeded to the post of astronomer royal upon his return, has been somewhat vilified by posterity for his opposition to Harrison's clocks. Whilst Harrison is celebrated today as the man who solved the longitude problem, in reality the high cost of producing accurate marine chronometers ensured that both methods would continue to be employed for finding longitude at sea. Maskelyne oversaw the completion of the first Nautical Almanac containing lunar tables for determining longitude in 1766.

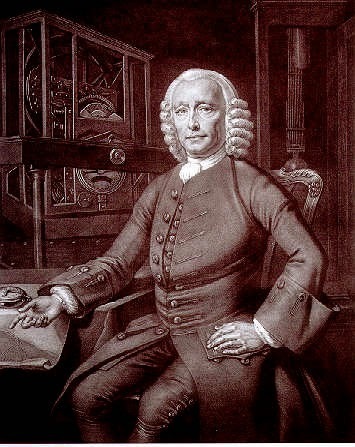

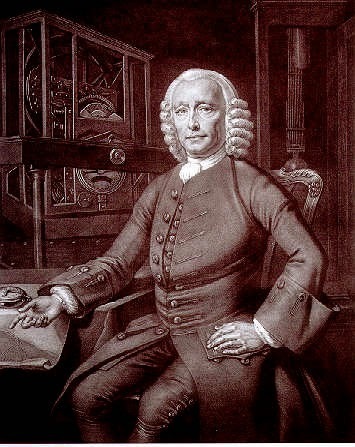

Mr Harrison poses proudly with his chronometers Both Harrison and Mayer were ultimately awarded prizes by the Board of Longitude, although Harrison would require the intervention of the king to receive his £9,000 reward and Mayer's award of the same amount would be paid to his widow after his death aged just 39. Ships, Clocks and Stars is on at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich until 5th January. Go see it if you have the chance. The highlight is undoubtedly the sight of all four of Harrison's beautiful chronometers together in the same place but as I found out, there was more than one dog in the hunt. The RMG longitude blog http://blogs.rmg.co.uk/longitude/ You may also enjoy - The Hourglass Sea http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/the-hourglass-sea.html?utm_source=bp_recent&utm-medium=gadget&utm_campaign=bp_recent

Mr Harrison poses proudly with his chronometers Both Harrison and Mayer were ultimately awarded prizes by the Board of Longitude, although Harrison would require the intervention of the king to receive his £9,000 reward and Mayer's award of the same amount would be paid to his widow after his death aged just 39. Ships, Clocks and Stars is on at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich until 5th January. Go see it if you have the chance. The highlight is undoubtedly the sight of all four of Harrison's beautiful chronometers together in the same place but as I found out, there was more than one dog in the hunt. The RMG longitude blog http://blogs.rmg.co.uk/longitude/ You may also enjoy - The Hourglass Sea http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/the-hourglass-sea.html?utm_source=bp_recent&utm-medium=gadget&utm_campaign=bp_recent

A Rake's Progress - 8th plate 1735 Such is the way in which the search for longitude was viewed by satirists such as Hogarth; as a fools quest. The vast sums in prize money promised by the Board of Longitude, formed in 1714, were a veritable pot of gold that tempted dreamers and schemers to devise solutions to the problem. In the coffee houses of London schemes for solving the longitude challenge were a popular topic of conversation and the more outlandish proponents were fair game for lampooning.

A Rake's Progress - 8th plate 1735 Such is the way in which the search for longitude was viewed by satirists such as Hogarth; as a fools quest. The vast sums in prize money promised by the Board of Longitude, formed in 1714, were a veritable pot of gold that tempted dreamers and schemers to devise solutions to the problem. In the coffee houses of London schemes for solving the longitude challenge were a popular topic of conversation and the more outlandish proponents were fair game for lampooning.No man was a more popular target for derision than William Whiston. Far from being a crackpot, Whiston succeeded to the Cambridge professorship of no less a luminary than Isaac Newton in 1702. Nevertheless he did hold unorthodox religious beliefs and was fascinated by miracles and prophecies. He caused alarm in 1736 by claiming that a comet was about to hit the earth. His other enduring fascination was with the problem of longitude and he was behind a number of proposals to the board.

Whiston's first proposal was as straightforward as it was impractical. Along with mathematician Humphrey Ditton, Whiston proposed using a system of anchored rocket ships around the globe. These ships, at positions of known longitude, would send up rockets at regular intervals. Ship's captains, observing the explosion of the rocket, would calculate their position based upon the time it took for the sound of the rocket to reach them. The admiralty, it need hardly be said, were unimpressed. Where were the funds and the thousands of men required to crew these ships to be found, they demanded. And how long would it be before they mutinied out of sheer boredom?

Halley's chart of magnetic variation

Halley's chart of magnetic variationUnperturbed, Whiston next proposed using magnetism to find longitude. By producing charts showing the lines of magnetic variation across the globe, it would be possible for ship's captains to compare true north, established through solar observation, with the magnetic north determined by their compasses and then refer to the chart to find their longitude. Indeed these lines of magnetic variation had already been charted in the Atlantic by Edmund Halley during his command of HMS Paramour in 1698-99 on the first ever purely scientific naval mission. Whiston received approval from the board of longitude to produce a chart of magnetic variation for southern England in 1719. Unfortunately for Whiston this idea too was ultimately doomed, for the variation in the earth's magnetic field would render any charts produced obsolete within a matter of years, requiring the entire painstaking process to begin again. The board eventually paid him £500 for his trouble.

In 1730 Whiston brought forth another proposal, this time based upon observing the regular motion of the moons of Jupiter. By noting the local time of an eclipse of one of the four moons as it passed behind or in front of the planet and comparing it to a table of the known times based on Greenwich, it would be possible to determine longitude. Once again there was nothing wrong with the theory, Galileo himself had suggested the use of Jupiter's moons as a celestial timepiece and it works perfectly well on land. The practicality however of observing the moons of Jupiter from the deck of a ship in anything other than perfect conditions, once again condemned the idea to the dustbin of longitude history. Whiston was not unaware of the difficulties and suggested using up to 7 telescopes in combination to ensure that the observer could keep Jupiter in their sights.

Whiston's unorthodox religious views eventually caused him to fall from establishment favour and he spent the rest of his life engaging in increasingly outlandish theological speculation. He died in 1752.

Whiston brandishes another cunning plan Ultimately the solution to the longitude problem boiled down to two methods; lunar distance and marine chronometers. The lunar distance method, couched as it was in mathematics and astronomy, was more attractive to the gentleman scientists of the Royal Society, who struggled to overcome their disappointment that 'Harrison's blasted watch', as third astronomer royal James Bradley described it, could provide a complete solution. In 1761 the Royal Society dispatched astronomer Neville Maskelyne to the island of St Helena to observe the transit of Venus. During the voyage Maskelyne was keen to try out the ideas of one Tobias Mayer. Mayer was a remarkable individual. Having come from poor and humble beginnings, he was entirely self taught and published his first mathematical work when he was just eighteen, subsequently obtaining work as a mapmaker. By the 1750's Mayer was the director of Gottingen observatory and had turned his mind to the issue of longitude. Mayer focussed on the lunar distance method, which allowed longitude to be determined by observing the angle between the moon and a chosen star, typically Regulus. By comparing the observed angle with tables compiled from Mayer's exacting observations, the mariner would be able to establish their precise local time and thereby their longitude. Mayer sent his tables to the Board of Longitude in 1755. They were assessed by Bradley, who had succeeded the great Edmund Halley in 1742, and were found to be most accurate. Bradley continued to build on Mayer's work, compiling further tables based on Greenwich. He was assisted in this work by Charles Mason, best known for his later partnership with Jeremiah Dixon in establishing the line that bears their names.

Whiston brandishes another cunning plan Ultimately the solution to the longitude problem boiled down to two methods; lunar distance and marine chronometers. The lunar distance method, couched as it was in mathematics and astronomy, was more attractive to the gentleman scientists of the Royal Society, who struggled to overcome their disappointment that 'Harrison's blasted watch', as third astronomer royal James Bradley described it, could provide a complete solution. In 1761 the Royal Society dispatched astronomer Neville Maskelyne to the island of St Helena to observe the transit of Venus. During the voyage Maskelyne was keen to try out the ideas of one Tobias Mayer. Mayer was a remarkable individual. Having come from poor and humble beginnings, he was entirely self taught and published his first mathematical work when he was just eighteen, subsequently obtaining work as a mapmaker. By the 1750's Mayer was the director of Gottingen observatory and had turned his mind to the issue of longitude. Mayer focussed on the lunar distance method, which allowed longitude to be determined by observing the angle between the moon and a chosen star, typically Regulus. By comparing the observed angle with tables compiled from Mayer's exacting observations, the mariner would be able to establish their precise local time and thereby their longitude. Mayer sent his tables to the Board of Longitude in 1755. They were assessed by Bradley, who had succeeded the great Edmund Halley in 1742, and were found to be most accurate. Bradley continued to build on Mayer's work, compiling further tables based on Greenwich. He was assisted in this work by Charles Mason, best known for his later partnership with Jeremiah Dixon in establishing the line that bears their names.

Mr Irwin's marine chair undergoes testing So off sailed Maskelyne aboard the Prince Henry bound for St Helena, putting Mayer's methods to practical use and becoming in the process an advocate of the lunar distance method. Two years later he was dispatched to Barbados aboard HMS Princess Louisa. He took with him Harrison's final chronometer H4, the culmination of 30 years of work, the accuracy of which would be compared directly with the lunar distance method. Maskelyne also took with him Mr Christopher Irwin's marine chair for testing. This gimballed chair was designed to allow astronomical observations to be made more easily from the pitching and rolling deck of a ship. Maskelyne found the chair to be completely useless. On arrival, Maskelyne would determine the longitude of Bridgetown using Jupiter's satellites and see which of the rival methods came closest. Harrison's chronometer was found to be accurate to within 10 miles, whereas the lunar distance calculations were only within 30. Maskelyne, who succeeded to the post of astronomer royal upon his return, has been somewhat vilified by posterity for his opposition to Harrison's clocks. Whilst Harrison is celebrated today as the man who solved the longitude problem, in reality the high cost of producing accurate marine chronometers ensured that both methods would continue to be employed for finding longitude at sea. Maskelyne oversaw the completion of the first Nautical Almanac containing lunar tables for determining longitude in 1766.

Mr Irwin's marine chair undergoes testing So off sailed Maskelyne aboard the Prince Henry bound for St Helena, putting Mayer's methods to practical use and becoming in the process an advocate of the lunar distance method. Two years later he was dispatched to Barbados aboard HMS Princess Louisa. He took with him Harrison's final chronometer H4, the culmination of 30 years of work, the accuracy of which would be compared directly with the lunar distance method. Maskelyne also took with him Mr Christopher Irwin's marine chair for testing. This gimballed chair was designed to allow astronomical observations to be made more easily from the pitching and rolling deck of a ship. Maskelyne found the chair to be completely useless. On arrival, Maskelyne would determine the longitude of Bridgetown using Jupiter's satellites and see which of the rival methods came closest. Harrison's chronometer was found to be accurate to within 10 miles, whereas the lunar distance calculations were only within 30. Maskelyne, who succeeded to the post of astronomer royal upon his return, has been somewhat vilified by posterity for his opposition to Harrison's clocks. Whilst Harrison is celebrated today as the man who solved the longitude problem, in reality the high cost of producing accurate marine chronometers ensured that both methods would continue to be employed for finding longitude at sea. Maskelyne oversaw the completion of the first Nautical Almanac containing lunar tables for determining longitude in 1766.

Mr Harrison poses proudly with his chronometers Both Harrison and Mayer were ultimately awarded prizes by the Board of Longitude, although Harrison would require the intervention of the king to receive his £9,000 reward and Mayer's award of the same amount would be paid to his widow after his death aged just 39. Ships, Clocks and Stars is on at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich until 5th January. Go see it if you have the chance. The highlight is undoubtedly the sight of all four of Harrison's beautiful chronometers together in the same place but as I found out, there was more than one dog in the hunt. The RMG longitude blog http://blogs.rmg.co.uk/longitude/ You may also enjoy - The Hourglass Sea http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/the-hourglass-sea.html?utm_source=bp_recent&utm-medium=gadget&utm_campaign=bp_recent

Mr Harrison poses proudly with his chronometers Both Harrison and Mayer were ultimately awarded prizes by the Board of Longitude, although Harrison would require the intervention of the king to receive his £9,000 reward and Mayer's award of the same amount would be paid to his widow after his death aged just 39. Ships, Clocks and Stars is on at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich until 5th January. Go see it if you have the chance. The highlight is undoubtedly the sight of all four of Harrison's beautiful chronometers together in the same place but as I found out, there was more than one dog in the hunt. The RMG longitude blog http://blogs.rmg.co.uk/longitude/ You may also enjoy - The Hourglass Sea http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/the-hourglass-sea.html?utm_source=bp_recent&utm-medium=gadget&utm_campaign=bp_recent

Published on December 02, 2014 03:16

November 3, 2014

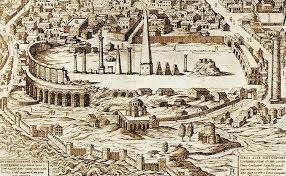

Born in the Purple - Constantine VII Part One

Let's get back to Byzantium. It's been a while.

This post follows on from my Enemies at the Gate series which ended with the troubled reign of Leo VI, known as 'the Wise'. That emperor’s controversial fourth marriage had at last secured the succession with the birth of his longed-for son, at the cost to his dignity of exclusion from the sacrament. The boy Constantine was known to posterity as Porphyrogenitus ‘born in the purple’ to underline the legitimacy of his father’s marriage and his own birth. For the first three decades of his reign, Constantine would be a marginalised spectator on the side lines and a bit part player in his own story. He was only four years old at the time of his father Leo’s death and so the throne was taken by his dissolute uncle Alexander.

The brief reign of Alexander, depicted right in a mosaic from the Hagia Sofia, would prove an unmitigated disaster. Such had been his resentment of his late brother that the new emperor would overturn every one of Leo VI’s policies with little thought for the consequences. His most damaging action was to insultingly dismiss an embassy from the Bulgars, breaking off peaceful relations. He also restored his late brother’s implacable opponent Patriarch Nicholas, who began plotting once more to overthrow the ruling dynasty. Alexander died from a stroke after just thirteen months, most of which he spent in debauchery and idle pursuits.

The brief reign of Alexander, depicted right in a mosaic from the Hagia Sofia, would prove an unmitigated disaster. Such had been his resentment of his late brother that the new emperor would overturn every one of Leo VI’s policies with little thought for the consequences. His most damaging action was to insultingly dismiss an embassy from the Bulgars, breaking off peaceful relations. He also restored his late brother’s implacable opponent Patriarch Nicholas, who began plotting once more to overthrow the ruling dynasty. Alexander died from a stroke after just thirteen months, most of which he spent in debauchery and idle pursuits.All of this left the young emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in a precarious position. On his death bed his uncle had appointed the Patriarch as regent in a final effort to spite his brother’s memory. Nicholas had lost the patriarchate over his opposition to Leo VI’s fourth marriage. Finding himself now as regent for the royal offspring of that union, his first action was to try to supplant Constantine, who he regarded as illegitimate.

Soon Nicholas was conspiring with Constantine Ducas, the son of that Andronicus with whom he had been accused of colluding against Leo. Just a few days after the young emperor’s coronation in the summer of 913, Ducas entered the city with a small force with the intention of seizing control of the palace. His plot had been discovered however and his party was set upon by a mob in the streets outside the hippodrome. The rebels managed to advance as far as the palace gate where a loyal force raised from the fleet engaged them in battle. Ducas lost his head in the fighting. With this first gambit having failed, the Patriarch attempted to distance himself from the plot by unleashing a bloody purge of Ducas’ supporters in the army.

Patriarch Nicholas as depicted by Nikolai Pavlovic 1917 The Patriarch’s assumption of the regency was marked by bitterness and spite. He had humiliated his predecessor Euphemius, having him publically stripped of his robes and beaten. He had flung the admiral Himerius into prison as punishment for his defeat by the Muslim convert turned privateer admiral Leo of Tripoli and had completely excluded the empress Zoe from the council of regency.

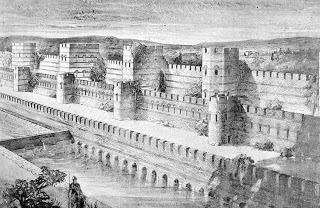

Patriarch Nicholas as depicted by Nikolai Pavlovic 1917 The Patriarch’s assumption of the regency was marked by bitterness and spite. He had humiliated his predecessor Euphemius, having him publically stripped of his robes and beaten. He had flung the admiral Himerius into prison as punishment for his defeat by the Muslim convert turned privateer admiral Leo of Tripoli and had completely excluded the empress Zoe from the council of regency.Meanwhile, the second of Alexander’s blunders had come home to roost for Symeon of Bulgaria had marched upon the capital. The Bulgars laid siege to Constantinople and as tradition dictated they laid waste to the lands outside the Theodosian Walls but could make little impression upon them. The Patriarch went out to meet with Symeon and with his desire to retain his Episcopal jurisdiction over the Bulgarian church overriding all other considerations, he found himself putty in the Bulgar ruler’s hands. Nicholas agreed to the resumption of tribute and also promised that Constantine would marry Symeon’s daughter. Well pleased with the bargain that would make him the emperor’s father in law, Symeon marched away.

The Patriarch however had gone too far in taking such action and found himself outmanoeuvred. The empress Zoe, who he had banished to a convent, swept back into power and Nicholas found his activities restricted to the ecclesiastical sphere. Zoe, known as Carbonopsina ‘the black-eyed’ was a legendary beauty and was used to asserting her will. Throwing aside her habit, Zoe took a firm grip on affairs of state. Nicholas’ agreement with Symeon was repudiated. The empress would have no barbarian princess marrying Constantine. Un-phased, the Bulgar Tsar prepared for war.

The forces of the caliphate had taken advantage of the empire’s preoccupation to overrun the buffer zone of Armenia, intervening in an Armenian civil war and subjugating the entire country to Abbasid rule. Zoe threw her weight behind Ashot II, depicted right, the exiled claimant to the Armenian crown and provided him with a large army with which to take back his land. Ashot was successful in his campaign, driving out the Arab troops and their allies and establishing himself as king of Armenia, earning himself the nom de guerre of Yerkat‘the iron’ in the process. A retaliatory raid by the forces of the caliph into Anatolia launched from Tarsus was also defeated and following this a treaty of peace was concluded with the caliph on reasonable terms. Zoe could congratulate herself on the success of her foreign policy.

The forces of the caliphate had taken advantage of the empire’s preoccupation to overrun the buffer zone of Armenia, intervening in an Armenian civil war and subjugating the entire country to Abbasid rule. Zoe threw her weight behind Ashot II, depicted right, the exiled claimant to the Armenian crown and provided him with a large army with which to take back his land. Ashot was successful in his campaign, driving out the Arab troops and their allies and establishing himself as king of Armenia, earning himself the nom de guerre of Yerkat‘the iron’ in the process. A retaliatory raid by the forces of the caliph into Anatolia launched from Tarsus was also defeated and following this a treaty of peace was concluded with the caliph on reasonable terms. Zoe could congratulate herself on the success of her foreign policy.The Bulgars remained the greatest threat however and soon Symeon was on the move once more, harassing the empire’s Thracian territories and seizing the city of Adrianople, which he abandoned upon payment of a large ransom. With peace secured in the east, troops were available for a campaign against the Bulgars. A grand strategy was devised to defeat Symeon through encirclement. The governor of Cherson was instructed to gather a force from amongst the fearsome Pechenegs who had settled down beside the Dnieper in the lands from which they had driven the Magyars. With these mercenary recruits, doubtless eager at the prospect of loot, he was to march to the Danube where he would rendezvous with the imperial fleet. Meanwhile another force under the command of Leo Phocas, the latest scion of that house to rise to the supreme command of the Byzantine armies, having replaced the late Constantine Ducas as Domestic of the Scholai, would march northward from the capital. The Bulgars would be caught between the two forces and crushed. Like many an overcomplicated plan, it all went wrong. The Pechenegs turned up on the Danube as planned but the fleet commander Romanus Lecapenus, for reasons which are unclear, failed to transport them across the river and they returned home. Meanwhile, unaware of the unravelling of the Byzantine strategy, Phocas marched on to confront the Bulgar army alone. Battle was joined in the late summer of 917 at Achelous on the Black Sea coast. The Byzantine sources claim that all was going well until Phocas lost control of his horse which galloped riderless through the army and started a panic as men feared their commander was dead. This is a story which crops up too often in tales of Byzantine defeat to be true every time but whatever the reason, the pursuit of the retreating Bulgars became disorderly. Symeon rallied his army and they counterattacked, putting the Byzantine forces to rout and slaughter. Phocas lived to fight another day, so must have found another horse from somewhere.

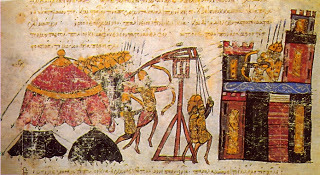

Rout at Achelous - Madrid Skylitzes Symeon advanced in pursuit of the retreating Byzantine army and gave them another mauling although by all accounts Leo’s men fought bravely. The son of Constantine Ducas is said to have died a hero’s death in this engagement, restoring his family honour.

Rout at Achelous - Madrid Skylitzes Symeon advanced in pursuit of the retreating Byzantine army and gave them another mauling although by all accounts Leo’s men fought bravely. The son of Constantine Ducas is said to have died a hero’s death in this engagement, restoring his family honour. Despite his somewhat patchy military record, it seems that Phocas had caught the empress’ eye and was being sized up as potential husband material. For those who mistrusted the Anatolian landed aristocracy, amongst which the Phocas clan was at present pre-eminent, this was not a desirable situation. Theodore, the tutor of young Constantine Porphyrogenitus, feared for his pupil’s life if Phocas were to ascend the throne and so sent an appeal to Romanus Lecapenus who, despite his recent disgrace, still commanded the Byzantine fleet.

Romanus was now presented with a remarkable opportunity to turn around his fortunes. From having only narrowly escaped a sentence of blinding for his part in the Achelous fiasco he was now in a position to present himself as the protector of Constantine. Zoe’s response was to order the fleet disbanded but the her instruction was disobeyed and those she sent to enforce it were arrested. With her authority in tatters she once more found herself completely sidelined by Nicholas who reassumed the regency. The Patriarch however was no longer in control of the situation which had descended into a power struggle between Leo Phocas and Romanus Lecapenus.

By the spring of 919 Romanus felt secure enough in his support to enter the palace of the Bucoleon and seize control of the reins of empire. He married his daughter Helen to the thirteen year old Constantine and assumed the title ofBasileopater ‘father of the emperor’. Phocas rose in revolt but his army refused to follow him and instead he was handed over to his enemies and blinded. As for empress Zoe, she soon found herself accused of attempting to poison Romanus and was forced back into her hated habit and dispatched once more into the seclusion of a convent; out of sight and out of mind.

To undermine the empress’ position as far as possible her marriage to Leo VI was condemned in the strongest terms by the church and fourth marriages were henceforth outlawed. The legitimacy of Constantine was however upheld, for after all, the authority of Romanus as Basileopaterwas dependent upon it and so Nicholas was denied a complete victory.

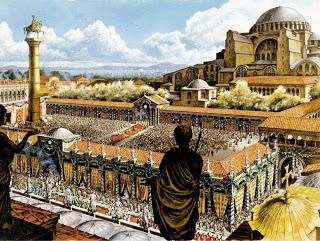

A 20th Century reimagining of Tsar Symeon

A 20th Century reimagining of Tsar Symeon Under Romanus, who was granted the title of Caesar by a compliant Constantine a year after his usurpation and crowned co-emperor just a few months later, the empire would enjoy a resurgence in its fortunes. His tenure as emperor began auspiciously and appropriately with a naval victory that saw the final demise of Leo of Tripoli, removing a persistent thorn from the side of the empire. Romanus followed this up by securing peace with Symeon, who in 924 had once more advanced to the walls of the capital. A summit was held between the two rulers on a jetty constructed on the shore at Blachernae for the purpose, with Romanus arriving by ship. The emperor gave the Bulgar Tsar a tongue lashing. Magnificent in the imperial regalia, Romanus castigated Symeon for making war on his fellow Christians and warned him to look to the salvation of his soul. The emperor told the Tsar that if it was treasure that he wanted then he could have all that he desired but implored him in God’s name to keep the peace. Feeling very small, Symeon consented and departed forthwith and never raised his hand against the empire again. Such at any rate is how the Byzantines would have us see this encounter. A more cynical observer could point out that, under the guise of his tirade, Romanus had offered tribute in exchange for peace and Symeon had consented. Nevertheless the peace held as Symeon became embroiled in conflict with the Slavic states on his western border, whose restlessness had doubtless been encouraged through Byzantine intrigue.

The capture of Melitene - Madrid Skylitzes This freed up the forces of the empire to turn against the caliphate once more. Romanus had appointed his Armenian countryman John Curcuas as Domestic of the Scholai and employed him in rooting out his opponents. In 926 Curcuas was sent at the head of a large force between fifty and eighty thousand strong to menace the petty kingdoms and cities of the frontier territories into switching their allegiance from the caliph to the emperor, demanding tribute and then following this up with armed invasion. The cities of Melitene and Samosata on the upper Euphrates were put to the sack before Curcuas turned his armies towards the kingdoms to the south and east of Ashot’s Armenia, sacking the Arab stronghold of Dvin.

The capture of Melitene - Madrid Skylitzes This freed up the forces of the empire to turn against the caliphate once more. Romanus had appointed his Armenian countryman John Curcuas as Domestic of the Scholai and employed him in rooting out his opponents. In 926 Curcuas was sent at the head of a large force between fifty and eighty thousand strong to menace the petty kingdoms and cities of the frontier territories into switching their allegiance from the caliph to the emperor, demanding tribute and then following this up with armed invasion. The cities of Melitene and Samosata on the upper Euphrates were put to the sack before Curcuas turned his armies towards the kingdoms to the south and east of Ashot’s Armenia, sacking the Arab stronghold of Dvin.Romanus meanwhile continued to strengthen his grip on power by establishing his family as a ruling dynasty. He had appointed his eldest son Christopher as co-emperor alongside himself and the increasingly marginalised Constantine and would elevate his two younger sons to the purple in due course. His youngest son, who had been gelded with a view to a career in the church; a not uncommon practice, would be installed as Patriarch. All the while the bookish Constantine, isolated and withdrawn, seemed all but forgotten. When a terrible famine accompanied by biblical swarms of locusts swept down upon the empire it was Romanus who arranged relief and shelter for the poor. When the worst was past it was Romanus who forced the aristocracy who had snapped up lands from the destitute peasantry at knock down prices to hand it back with compensation, earning the gratitude of his people. When Curcuas once more successfully besieged and annexed Melitene in 934 it was Romanus who basked in the glory of victory.

Igor sets out to attack Constantinople - Ratziwill chronicle War on the frontier settled into tit for tat raiding with the highly capable Abbasid governor of Amida, Sayf ad Daula, proving a worthy rival to Curcuas. The spring of 941 found both fleet and army engaged in campaigns against the Arabs when once more over the horizon there appeared a Rus fleet descending upon the capital.

Igor sets out to attack Constantinople - Ratziwill chronicle War on the frontier settled into tit for tat raiding with the highly capable Abbasid governor of Amida, Sayf ad Daula, proving a worthy rival to Curcuas. The spring of 941 found both fleet and army engaged in campaigns against the Arabs when once more over the horizon there appeared a Rus fleet descending upon the capital. Following the death of Oleg, Igor the son of Rurik had come into his inheritance as Prince of Kiev. Keen to demonstrate to his followers that he was made of the same uncompromising Viking stuff as his father, he embarked upon a new expedition to Constantinople. The Russian Primary Chronicle relates that Igor sailed into the Black Sea with an improbable armada of ten thousand ships. Only fifteen serviceable ships were available to the emperor but these proved sufficient to deter the Rus armada from an assault on Constantinople itself. An attack by the Protovestiarios Theodore with Greek fire destroyed many of the Rus ships with large numbers of their crews drowning as they leapt overboard to escape the flames. Turning away from the capital which remained inviolate behind its walls, Igor landed on the Bithynian coast of Asia Minor and set about doing what Vikings did best. According to their own chronicle, which was no doubt based on Byzantine sources, the Rus; waged war along the Pontus as far as Heraclea and Paphlagonia, and laid waste the entire region of Nicomedia, burning everything along the gulf. Of the people they captured, some they butchered, others they set up as targets and shot at, some they seized upon, and after binding their hands behind their backs, they drove iron nails through their heads. Many sacred churches they gave to the flames, while they burned many monasteries and villages, and took no little booty on both sides of the sea.

Fighting the Rus - Madrid Skylitzes

Fighting the Rus - Madrid SkylitzesWhen Curcuas arrived at the head of his troops both sides acknowledge that the fighting was hard but eventually the Rus were driven back to their ships. By now the Byzantine fleet had arrived and the Rus were chased from the shores of the empire with heavy losses. Undeterred, Igor began raising fresh forces but accepted the offer of a renewed treaty from the emperor rather than face another dose of Greek fire. It was probably at this point that the trading concessions ascribed to Oleg in 911 were in fact obtained.

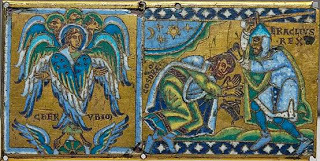

Curcuas meanwhile had returned to the east and had swept all before him in an invasion of Mesopotamia which saw the former imperial frontier strongholds of Amida and Dara sacked and plundered, if not permanently regained. Laying siege to the city of Edessa in 944, Curcuas agreed to spare the city when the largely Christian populace offered to hand over the sacred relic known as the Mandylion. This was a cloth bearing a portrait believed to be an actual likeness of Christ, obtained when the Edessan ruler Abgar had sent a delegation to Jesus, asking him to come to Edessa and heal the king. Much miraculous legend had subsequently sprung up around the Mandylion, which had been lost for centuries and recovered just in time to save the city from a Persian attack. Now it was borne back to Constantinople in triumph accompanied by scenes of pious exultation.

Abgar with the Mandylion from an icon at St Catherines, Sinai In this charged atmosphere the aging Romanus began to ponder the fate of his soul. His eldest son Christopher had died ten years earlier and his younger sons Stephen and Constantine now expected to succeed to the empire in turn, pushing the hapless Porphyrogenitusaside. Romanus now declared that Constantine Porphyrogenitus would succeed him as senior emperor. Man of the moment John Curcuas was to marry his daughter to Porphyrogenitus’ son and thereafter serve as protector to the legitimate regime. Alarmed at the prospect of the imperial gravy train grinding to a halt, Romanus’ sons mobilised their supporters in an attempt to thwart their father. Poor Curcuas found himself out-manoeuvred. Not only was the wedding off but he was replaced as Domestic by Stephen’s nominee, the splendidly named Pantherius. Romanus found himself forcibly side-lined by his sons and was shipped off to an island monastery, protesting feebly.

Abgar with the Mandylion from an icon at St Catherines, Sinai In this charged atmosphere the aging Romanus began to ponder the fate of his soul. His eldest son Christopher had died ten years earlier and his younger sons Stephen and Constantine now expected to succeed to the empire in turn, pushing the hapless Porphyrogenitusaside. Romanus now declared that Constantine Porphyrogenitus would succeed him as senior emperor. Man of the moment John Curcuas was to marry his daughter to Porphyrogenitus’ son and thereafter serve as protector to the legitimate regime. Alarmed at the prospect of the imperial gravy train grinding to a halt, Romanus’ sons mobilised their supporters in an attempt to thwart their father. Poor Curcuas found himself out-manoeuvred. Not only was the wedding off but he was replaced as Domestic by Stephen’s nominee, the splendidly named Pantherius. Romanus found himself forcibly side-lined by his sons and was shipped off to an island monastery, protesting feebly.Stephen and Constantine expected the Porphyrogenitus to continue in his passive acceptance of their usurpation, lending legitimacy to the rule of the Lecapeni but playing no active role in affairs of state. They reckoned however without the influence of their sister, the empress Helena, who urged her retiring husband to find his backbone. By now the emperor was in his late thirties and if he was ever going to assert his rights, now was the time. Once he had been stirred into action by his wife, Porphyrogenitus found a willing champion in the form of Bardas Phocas, brother of Romanus’ blinded rival Leo. Within months of their seizure of power, disaster overtook the regime of Stephen and Constantine. Mobs rioted in the streets in protest at their treatment both of their father and of Porphyrogenitus. Meanwhile their man Patherius proved to be a paper tiger. Brought to battle by Sayf ad Daula whilst raiding near Aleppo, his forces suffered a major defeat and he withdrew from Syria. Marching west in support of the Lecapeni he then suffered a further defeat at the hands of Bardas Phocas. The game was up and Stephen and Constantine soon shared the fate of their father, exiled to separate monasteries to contemplate their misdeeds.

The Edessenes surrender the Mandylion - Madrid Skylitzes A story which no doubt grew up in later years is told in the Byzantine sources of how Stephen had looked blankly at the Mandylion when it arrived in Constantinople, unable to see any image upon it. Constantine Porphyrogenitus however had immediately identified the features of Christ and pointed them out to the embarrassment of the young Lecapenus. It thus seemed that heaven decreed that the Porphyrogenitus had been born to rule, but after a lifetime on the side lines, was he up to the challenge?

The Edessenes surrender the Mandylion - Madrid Skylitzes A story which no doubt grew up in later years is told in the Byzantine sources of how Stephen had looked blankly at the Mandylion when it arrived in Constantinople, unable to see any image upon it. Constantine Porphyrogenitus however had immediately identified the features of Christ and pointed them out to the embarrassment of the young Lecapenus. It thus seemed that heaven decreed that the Porphyrogenitus had been born to rule, but after a lifetime on the side lines, was he up to the challenge?You may also enjoy Enemies at the Gate

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/enemies-at-gate-part-two-reign-of.html

and Rise of the Rus

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/rise-of-rus.html?utm_source=bp_recent&utm-medium=gadget&utm_campaign=bp_recent

Published on November 03, 2014 02:26

October 1, 2014

Black Spartans - the rise of the Zulu Nation

And now for something completely different. I have recently been watching the '80's miniseries Shaka Zulu. It is an enjoyable romp and a bold piece of television for the time, in which whole hour long episodes pass without the 'stars' Edward Fox and Robert Powell making an appearance and instead centre stage being given to the cast of African newcomers to tell the story of Shaka's remarkable rise to power.

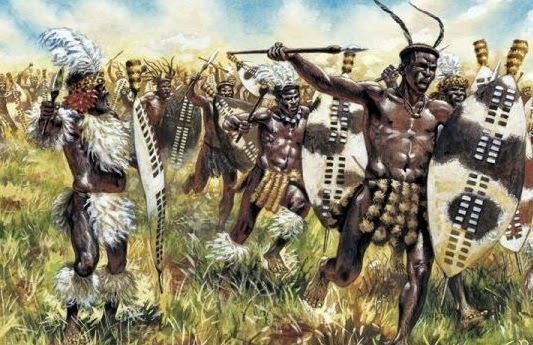

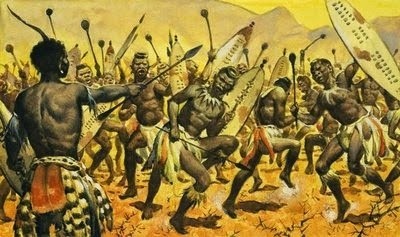

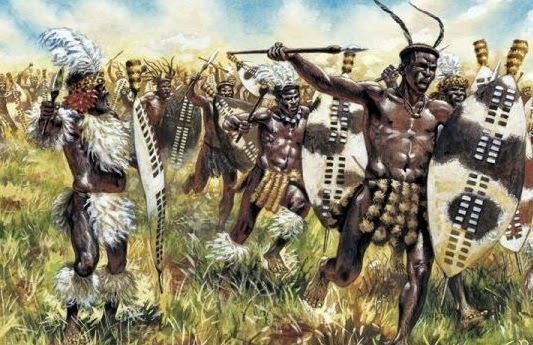

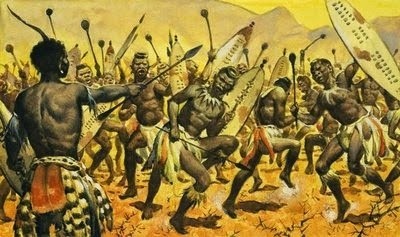

The Zulu war machine As I watched, I mused that the story of the rise of the Zulus had many coincidental parallels in classical history. On the plains of Southern Africa in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries there occurred something akin to the hoplite revolution of ancient Greece, where ideas on organisation, weapons and tactics evolved in similar way, albeit with different causes and consequences. The man who drove this revolution forward more than any other was Shaka, who was born in approximately 1787 in not entirely promising circumstances. He was a bastard, albeit of noble parentage. His father was the Zulu prince Sengzangakhona. At the time the Zulu were a relatively small and insignificant tribe, just one of a hundred Nguni chiefdoms scattered across the plains between the Drakensburg Mountains and the Indian Ocean.

The Zulu war machine As I watched, I mused that the story of the rise of the Zulus had many coincidental parallels in classical history. On the plains of Southern Africa in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries there occurred something akin to the hoplite revolution of ancient Greece, where ideas on organisation, weapons and tactics evolved in similar way, albeit with different causes and consequences. The man who drove this revolution forward more than any other was Shaka, who was born in approximately 1787 in not entirely promising circumstances. He was a bastard, albeit of noble parentage. His father was the Zulu prince Sengzangakhona. At the time the Zulu were a relatively small and insignificant tribe, just one of a hundred Nguni chiefdoms scattered across the plains between the Drakensburg Mountains and the Indian Ocean.

Each tribe lived a pastoral existence. Settlements were centred around the kraal of the chief, with the beehive shaped huts of the people radiating outwards in concentric circles. Wealth and status was measured above all in cattle, the tending of which was the responsibility of men folk, particularly the young boys, whilst the raising of crops was the preserve of the women. The Nguni male was also a hunter and a warrior. Wars were fought between tribes on a strictly limited basis, generally over control of pasture or to settle some insult. Fighting largely took place over long range with the throwing of spears and consisted of more posturing than actual combat. The womenfolk of the tribes would come to watch from a distance. Occasionally one side might charge the other to drive them from the field. The defeated enemy was not generally pursued. If a tribe was driven from their lands they simply moved on. Shaka would change all of this.

Shaka's path to the leadership of his people would not be easy however. His mother Nandi was the daughter of the chief of the neighbouring Langeni tribe. Her illicit dalliance with Sengzangakhona was regretted by the Zulu prince, who at first attempted to deny Nandi's pregnancy. He instead claimed that the woman was fantasizing and that she was suffering from a swelling of the stomach caused by the iShaka beetle. When the boy was born, Nandi's ironic choice of name was a tongue in cheek riposte to his father's protestations. Sengzangakhona was eventually forced to acknowledge his paternal responsibilities and took Nandi as his third wife. The reconciliation was short-lived however and Shaka and his mother were driven out into a life of exile.

A portrait of Shaka by Nathaniel Isaacs The rejection of his father and the humiliation of his mother lit the fire of a lifelong resentment in young Shaka. Relentless bullying at the hands of the youths of the Mthethwa people, amongst whom Nandi took refuge in the home of her aunt, served to stoke this resentment into a dark rage. In the opening years of the Nineteenth Century the Mthethwa were one of two large rival power groups amongst the Nguni. Under the leadership of their paramount chief Dingiswayo, the foundations of the military system that Shaka would create were being put into place. When Shaka took his place amongst the young warriors of the Mthethwa, he would find the perfect outlet for his inner fury.