Simon B. Jones's Blog: Slings and arrows, page 2

September 2, 2015

Harun al Rashid Part Two - Fall of the Barmakids

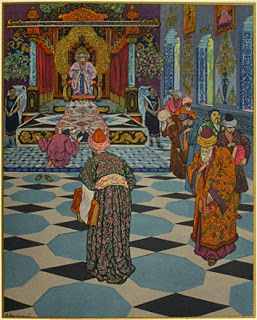

In the stories of the Arabian Nights, which are providing my current bedtime reading, the Caliph Harun al Rashid has a mischievous streak. He delights in going out incognito into the streets of Baghdad to join in the revels of others before revealing himself as the Commander of the Faithful and delivering justice or generosity to his unsuspecting subjects. In these adventures he is invariably accompanied by his best friend and closest advisor, Jaffar the Barmacid. Jaffar had grown up with Harun in the city of Rayy. His father Yahya had been the caliph’s tutor. He was tutor in turn to Harun’s son Mamun. He had served as governor of Syria for Harun and been the keeper of his royal seal. Along with his father and brother Fadl, Jaffar had administered the affairs of the caliphate efficiently. He had amassed great personal wealth whilst doing so, much of it in the form of personal gifts from the caliph. He had spent many, many nights in Harun’s company, enjoying all the finest things in life; talking long into the night, eating, drinking and gaming, listening to music and poetry and watching dancing girls. He was a good, close and loyal friend to the caliph, who owed a great deal to Jaffar and his family. Perhaps too much. Towards the end their relationship cooled, but that end when it came was shocking in its sudden ruthlessness.

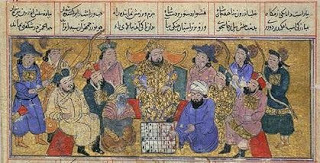

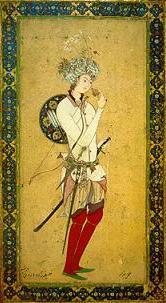

Jaffar holding court

Jaffar holding court

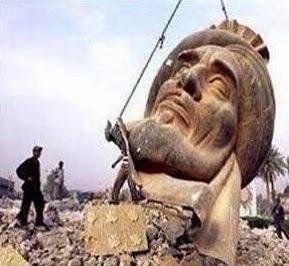

In Baghdad on a January night in 803, having parted from the caliph on good terms and returned to his home, Jaffar the Barmakid found himself summoned once more to the palace. Whilst he awaited Harun’s pleasure he was seized and his head was struck off. On Harun’s orders his body was then mutilated by being cut in two. The three parts of his body were ordered to be displayed on the bridges of Baghdad. They would rot there for the next two years until they were taken down and burned; a dire warning to all passers-by of the fickleness of absolute rulers and the dangers of flying too close to the sun. Following the execution of Jaffar, Yahya, his surviving sons and his brother were all thrown into prison. All of their vast wealth and property was confiscated.

What was their crime? No charges were ever made. Yahya and Fadl both died in prison. Fadl was possibly tortured to death in an attempt to make him reveal the location of hidden assets. The Barmakids had perhaps presumed too much for too long as they had wielded power in the caliph’s name, making decisions without asking his opinion. Old Yahya had perhaps been too familiar with the caliph, playing the father figure long after the son had grown up. Harun had not made a secret of his irritation. Yahya had seemed to be losing the caliph’s favour in recent times, having been repeatedly and pointedly insulted in the caliph’s presence by subtle means that were lost on no-one, whilst Fadl had seen his responsibilities given to men hostile to his family. The warning signs were there. They had enemies aplenty of course; jealous rivals, most notably the chamberlain Fadl ibn Rabi, son of Hadi’s murdered vizier, who capitalised on the Barmakid’s downfall to take their place. It is likely that he and others poured poison into the caliph’s ears against his former favourites.

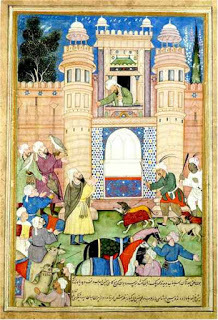

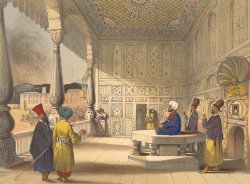

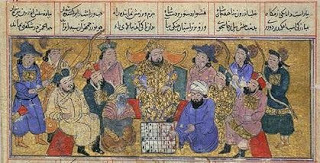

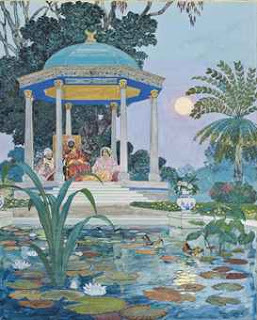

The Barmakids display their wealth - Akhbar i Barmakyan

The Barmakids display their wealth - Akhbar i Barmakyan

There is enough there perhaps to understand the Barmakids’ downfall, but why was Jaffar, who Harun had loved best of all, so savagely treated? Two particular accusations are levelled at Jaffar. One is that he protected the Alid rebel ibn Abdullah and lied to the caliph about his whereabouts. Certainly the Barmakids were more conciliatory towards the Alids in general than the caliph wished them to be, for he suspected that they plotted against him, but a lot of time had passed in the interim and it seems a long time to bear a grudge. Another story told is that Jaffar had an illicit affair with the caliph’s sister and that a child was born of the affair and was smuggled away to Mecca. When Harun discovered the truth he had the child killed and his sister buried alive and then took his revenge on Jaffar. This perhaps is too fanciful to be true but of all the reasons given it is the only one which seems to come close to providing Harun with a strong enough motive for his actions against Jaffar.

The timing of their downfall suggests there may have been another factor in Harun’s decision to take down the Barmakids. Just a month before turning against the Barmakids, Harun had publically settled his plans for the succession in a solemn ceremony at Mecca during the Hajj. Harun had children by twenty different mothers and like his father before him he had marked out two of them to be groomed for the succession. His eldest son was Abd Allah, known by the honorific title Mamun. He was the son of a Persian slave girl who had died in childbirth but as the caliph’s first born he enjoyed his father’s affection and showed great promise, with Jaffar as his mentor. His second son was named Mohammad, known by the title Amin and was his son by his favourite wife Zubayda. His education had been entrusted to Fadl the Barmakid. Younger and less academically gifted than Mamun he may have been but his superior pedigree ensured that Amin was the heir apparent.

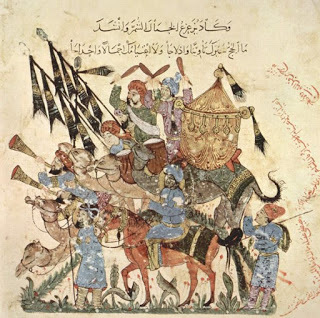

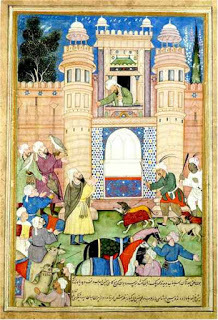

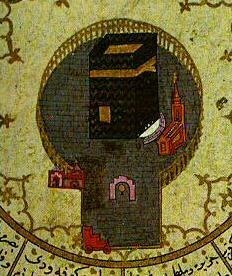

A later medieval depiction of the Hajj

A later medieval depiction of the Hajj

It seems odd given his own experiences with his elder brother Hadi, that Harun should seek to engineer precisely the same situation in the next generation that had led to bad blood and murder before his own accession. This however was what he did. Both sons had received the oaths of loyalty as boys but now Harun would have their oaths to each other. At Mecca he read out and had displayed on the walls of the Kabaa, the terms of the succession to which the two brothers swore before the assembled great men of the caliphate. Amin would succeed his father as caliph. He would have direct control over the western portion of Harun’s empire. His brother would be his heir and could not be supplanted by any sons born to Amin. Furthermore, Mamun would have complete control over Khurasan and the other eastern provinces of the caliphate; a vast and powerful territory. Mamun would appoint his own officials and have control over his own armies, which were substantial. Most critically he would not be required to send any tax revenues to his brother, to whom he would pledge his loyalty but little else. Harun had effectively divided the empire and set up an almost inevitable conflict between his two sons. He hoped that the public taking of oaths within the sacred enclosure of Mecca and their continuing display upon the walls of the Kabaa would awe his sons into keeping the peace. In this assumption he would be proved hopelessly naive.

Many ordinary folk, we are told in admittedly hindsight filled accounts, shook their heads and declared that a disaster had been stored up for the future and it didn’t take a prophet or a genius to see the likely outcome of Harun’s arrangement. Being as they were first rate political manoeuvrers, no doubt the Barmakids could see the writing on the wall and they surely cannot have thought Harun’s plans for the succession to be a good idea. Perhaps they gave voice to those doubts. Perhaps they decided that when the time came, they would make arrangements of their own and defy the caliph’s wishes. Perhaps the caliph knew of or suspected this. Perhaps Fadl ibn Rabi whispered in his ear that the Barmakids plotted to undermine his plan and when he returned to Baghdad he resolved at last to bring about their demise. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps...

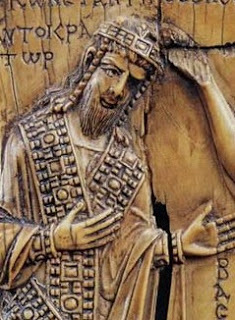

The Kabaa in Mecca was the scene for the oath taking Scarcely had Jaffar’s gruesome remains been spitted on the bridges of Baghdad then the caliph left the city once more for Raqqa. Here he received a letter from the new Emperor of the Romans Nicephorus I which sent him into a towering rage. Nicephorus, a onetime treasury official, having deposed the empress Irene, had set about reversing her ruinous policies, revoking the generous tax breaks she had given to the church and earning himself a truly diabolical write up from the monastic chroniclers of Byzantine history in the process. He also sought to reverse the flow of gold to the caliphate, ending the tribute payments that Irene had been making to the caliph since his campaign of 797. He had written to Harun to explain his position, framing his argument in an analogy through the common language of chess. Irene, Nicephorus explained, had behaved as if she were a mere pawn, paying out tribute to Harun, whom he described as a rook, when really Harun should have been paying tribute to her. The assertion was clear enough. If Harun was a mere rook then Nicephorus to whom he should be paying tribute was a king and Harun’s superior. The caliph contemptuously wrote his response on the back of Nicephorus’ letter.

The Kabaa in Mecca was the scene for the oath taking Scarcely had Jaffar’s gruesome remains been spitted on the bridges of Baghdad then the caliph left the city once more for Raqqa. Here he received a letter from the new Emperor of the Romans Nicephorus I which sent him into a towering rage. Nicephorus, a onetime treasury official, having deposed the empress Irene, had set about reversing her ruinous policies, revoking the generous tax breaks she had given to the church and earning himself a truly diabolical write up from the monastic chroniclers of Byzantine history in the process. He also sought to reverse the flow of gold to the caliphate, ending the tribute payments that Irene had been making to the caliph since his campaign of 797. He had written to Harun to explain his position, framing his argument in an analogy through the common language of chess. Irene, Nicephorus explained, had behaved as if she were a mere pawn, paying out tribute to Harun, whom he described as a rook, when really Harun should have been paying tribute to her. The assertion was clear enough. If Harun was a mere rook then Nicephorus to whom he should be paying tribute was a king and Harun’s superior. The caliph contemptuously wrote his response on the back of Nicephorus’ letter.

To Nicephorus the Roman Dog, I have read your letter. Oh disloyal son. My answer will reach you sooner than you wish.

It was fighting talk and the caliph followed it up with an immediate invasion which Nicephorus was in no position to do anything about. The troops of the Anatolian themes were in revolt against him having declared their commander Bardanes Turcus as a rival emperor. Turcus himself claimed to be fighting on behalf of Irene and on news of her death he desisted in his revolt and voluntarily entered a monastery but a year later was blinded. Harun meanwhile had taken advantage of the chaos to pillage and burn his way through Cilicia. Nicephorus was left with little choice but to agree to a humiliating resumption of Irene’s tribute payments in order to secure a truce. Harun could have asked for nothing better. Hostilities were resumed the following year and resulted in a defeat for Nicephorus when he was ambushed and barely escaped with his life at the battle of Krasos thanks to the efforts of his officers.

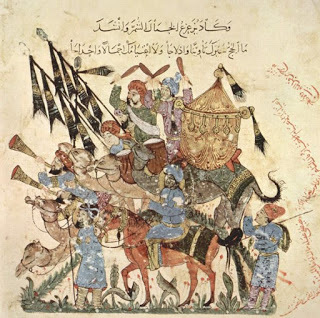

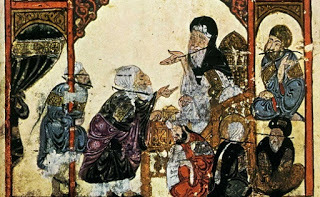

Chess - a perfect analogy for diplomacy?

Chess - a perfect analogy for diplomacy?

Now however it was the caliph’s turn to be distracted by internal dissent at the far end of his empire. Complaints reached Harun concerning the conduct of his governor of Khurasan Ali ibn Isa, an incompetent extortionist he had appointed in place of Fadl the Barmakid predominantly because he was a rival of the family. Harun decided to visit the province in person to discover the truth and he agreed a truce with Nicephorus in exchange for more tribute. In 805 he set out for Rayy. Here he met with Ali and found himself persuaded by rich gifts and sweet words that all was well. He confirmed his governor in his post and then found himself hitting the roof once more when news arrived that Nicephorus had taken advantage of his absence to breach the peace and had sacked the city of Tarsus as well as besieging Melitene and invading neutral Cyprus.

The following summer Harun led a massive invasion force reputed to be some 130,000 strong, an exaggeration to be sure but clearly the largest force sent across the border in living memory. Elements of the army advanced north as far as Ancyra whilst Harun settled down to besiege the fortified town of Heraclea in Cilicia, which proved to be a tough nut to crack. After two weeks of bombardment the town’s fortifications were still holding strong. On the seventeenth day a champion was sent out from Heraclea to challenge the Muslims to single combat and was defeated by an undistinguished volunteer from the ranks. Harun now resolved to terrorise the town into submission and rained flaming missiles down on the buildings within the walls. On the thirtieth day the populace abandoned their burning houses, threw open the gates and surrendered. The populace of Heraclea were taken away to be resettled as subjects of the caliph whilst the town was plundered and burned. Nicephorus meanwhile did no more than skirmish with isolated elements of the caliph’s forces and was overawed by the size of the army that the caliph had at his disposal. With the threat of further trouble on his western frontier from the Bulgars, Nicephorus had no choice but to make peace. He sent a deputation of churchmen to negotiate with the caliph who agreed to withdraw on resumption of an annual tribute of thirty thousand gold pieces, a promise not to rebuild Heraclea and a personal payment of the jizya poll tax of four gold pieces from the emperor himself, symbolic of his personal submission to the authority of the caliph. Nicephorus paid up. It was checkmate to Harun al Rashid.

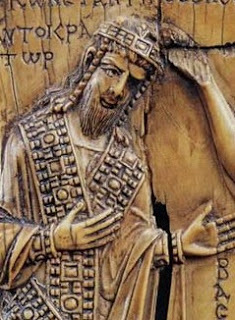

Nicephorus found himself handing over plenty of these

Nicephorus found himself handing over plenty of these

Having humbled the Byzantines, Harun once more turned his attention to Khurasan where a full scale revolt had now broken out against his governor Ali ibn Isa. The trouble had started in Samarkand when a local aristocrat was imprisoned for perfectly legitimate reasons but escaped and then whipped up a revolt in order to evade justice. The rebellion spread like wildfire through Transoxania and an army sent to restore order was defeated and the governor’s son killed. Harun dispatched an army from Baghdad to restore order under his most trusted general Harthama with orders to seize and depose the governor. This was done but the rebels still refused to return to the fold.

On receiving this news Harun decided to once more set out for the east himself. He charged his younger son Qasim with keeping an eye on the Byzantines from Raqqa and left his son Amin in charge in Baghdad. He then set out accompanied by Fadl ibn Rabi and his son Mamun, who was to take charge of his province, along with a vast entourage, making his slow progress towards Merv. The caliph was suffering from terrible stomach pains and knew that his days were numbered. By the time he reached Rayy it seemed unlikely that he would complete the journey. Mamun was sent on to Merv where his inheritance awaited and where he would reimpose control. Harun reached the town of Tus in northern Iran in March 809 and could go no further. Here on 24th March he died, aged forty three. He left his empire primed for chaos and when that chaos subsided nothing would quite be the same. In the centuries to follow, men would look back on his reign as an era of comparative peace and stability that would take on a golden hue and his reputation would attain that of a ruler of greatness. Was he truly great though, Dear Reader? I, for one, remain unconvinced.

Jaffar holding court

Jaffar holding courtIn Baghdad on a January night in 803, having parted from the caliph on good terms and returned to his home, Jaffar the Barmakid found himself summoned once more to the palace. Whilst he awaited Harun’s pleasure he was seized and his head was struck off. On Harun’s orders his body was then mutilated by being cut in two. The three parts of his body were ordered to be displayed on the bridges of Baghdad. They would rot there for the next two years until they were taken down and burned; a dire warning to all passers-by of the fickleness of absolute rulers and the dangers of flying too close to the sun. Following the execution of Jaffar, Yahya, his surviving sons and his brother were all thrown into prison. All of their vast wealth and property was confiscated.

What was their crime? No charges were ever made. Yahya and Fadl both died in prison. Fadl was possibly tortured to death in an attempt to make him reveal the location of hidden assets. The Barmakids had perhaps presumed too much for too long as they had wielded power in the caliph’s name, making decisions without asking his opinion. Old Yahya had perhaps been too familiar with the caliph, playing the father figure long after the son had grown up. Harun had not made a secret of his irritation. Yahya had seemed to be losing the caliph’s favour in recent times, having been repeatedly and pointedly insulted in the caliph’s presence by subtle means that were lost on no-one, whilst Fadl had seen his responsibilities given to men hostile to his family. The warning signs were there. They had enemies aplenty of course; jealous rivals, most notably the chamberlain Fadl ibn Rabi, son of Hadi’s murdered vizier, who capitalised on the Barmakid’s downfall to take their place. It is likely that he and others poured poison into the caliph’s ears against his former favourites.

The Barmakids display their wealth - Akhbar i Barmakyan

The Barmakids display their wealth - Akhbar i BarmakyanThere is enough there perhaps to understand the Barmakids’ downfall, but why was Jaffar, who Harun had loved best of all, so savagely treated? Two particular accusations are levelled at Jaffar. One is that he protected the Alid rebel ibn Abdullah and lied to the caliph about his whereabouts. Certainly the Barmakids were more conciliatory towards the Alids in general than the caliph wished them to be, for he suspected that they plotted against him, but a lot of time had passed in the interim and it seems a long time to bear a grudge. Another story told is that Jaffar had an illicit affair with the caliph’s sister and that a child was born of the affair and was smuggled away to Mecca. When Harun discovered the truth he had the child killed and his sister buried alive and then took his revenge on Jaffar. This perhaps is too fanciful to be true but of all the reasons given it is the only one which seems to come close to providing Harun with a strong enough motive for his actions against Jaffar.

The timing of their downfall suggests there may have been another factor in Harun’s decision to take down the Barmakids. Just a month before turning against the Barmakids, Harun had publically settled his plans for the succession in a solemn ceremony at Mecca during the Hajj. Harun had children by twenty different mothers and like his father before him he had marked out two of them to be groomed for the succession. His eldest son was Abd Allah, known by the honorific title Mamun. He was the son of a Persian slave girl who had died in childbirth but as the caliph’s first born he enjoyed his father’s affection and showed great promise, with Jaffar as his mentor. His second son was named Mohammad, known by the title Amin and was his son by his favourite wife Zubayda. His education had been entrusted to Fadl the Barmakid. Younger and less academically gifted than Mamun he may have been but his superior pedigree ensured that Amin was the heir apparent.

A later medieval depiction of the Hajj

A later medieval depiction of the HajjIt seems odd given his own experiences with his elder brother Hadi, that Harun should seek to engineer precisely the same situation in the next generation that had led to bad blood and murder before his own accession. This however was what he did. Both sons had received the oaths of loyalty as boys but now Harun would have their oaths to each other. At Mecca he read out and had displayed on the walls of the Kabaa, the terms of the succession to which the two brothers swore before the assembled great men of the caliphate. Amin would succeed his father as caliph. He would have direct control over the western portion of Harun’s empire. His brother would be his heir and could not be supplanted by any sons born to Amin. Furthermore, Mamun would have complete control over Khurasan and the other eastern provinces of the caliphate; a vast and powerful territory. Mamun would appoint his own officials and have control over his own armies, which were substantial. Most critically he would not be required to send any tax revenues to his brother, to whom he would pledge his loyalty but little else. Harun had effectively divided the empire and set up an almost inevitable conflict between his two sons. He hoped that the public taking of oaths within the sacred enclosure of Mecca and their continuing display upon the walls of the Kabaa would awe his sons into keeping the peace. In this assumption he would be proved hopelessly naive.

Many ordinary folk, we are told in admittedly hindsight filled accounts, shook their heads and declared that a disaster had been stored up for the future and it didn’t take a prophet or a genius to see the likely outcome of Harun’s arrangement. Being as they were first rate political manoeuvrers, no doubt the Barmakids could see the writing on the wall and they surely cannot have thought Harun’s plans for the succession to be a good idea. Perhaps they gave voice to those doubts. Perhaps they decided that when the time came, they would make arrangements of their own and defy the caliph’s wishes. Perhaps the caliph knew of or suspected this. Perhaps Fadl ibn Rabi whispered in his ear that the Barmakids plotted to undermine his plan and when he returned to Baghdad he resolved at last to bring about their demise. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps...

The Kabaa in Mecca was the scene for the oath taking Scarcely had Jaffar’s gruesome remains been spitted on the bridges of Baghdad then the caliph left the city once more for Raqqa. Here he received a letter from the new Emperor of the Romans Nicephorus I which sent him into a towering rage. Nicephorus, a onetime treasury official, having deposed the empress Irene, had set about reversing her ruinous policies, revoking the generous tax breaks she had given to the church and earning himself a truly diabolical write up from the monastic chroniclers of Byzantine history in the process. He also sought to reverse the flow of gold to the caliphate, ending the tribute payments that Irene had been making to the caliph since his campaign of 797. He had written to Harun to explain his position, framing his argument in an analogy through the common language of chess. Irene, Nicephorus explained, had behaved as if she were a mere pawn, paying out tribute to Harun, whom he described as a rook, when really Harun should have been paying tribute to her. The assertion was clear enough. If Harun was a mere rook then Nicephorus to whom he should be paying tribute was a king and Harun’s superior. The caliph contemptuously wrote his response on the back of Nicephorus’ letter.

The Kabaa in Mecca was the scene for the oath taking Scarcely had Jaffar’s gruesome remains been spitted on the bridges of Baghdad then the caliph left the city once more for Raqqa. Here he received a letter from the new Emperor of the Romans Nicephorus I which sent him into a towering rage. Nicephorus, a onetime treasury official, having deposed the empress Irene, had set about reversing her ruinous policies, revoking the generous tax breaks she had given to the church and earning himself a truly diabolical write up from the monastic chroniclers of Byzantine history in the process. He also sought to reverse the flow of gold to the caliphate, ending the tribute payments that Irene had been making to the caliph since his campaign of 797. He had written to Harun to explain his position, framing his argument in an analogy through the common language of chess. Irene, Nicephorus explained, had behaved as if she were a mere pawn, paying out tribute to Harun, whom he described as a rook, when really Harun should have been paying tribute to her. The assertion was clear enough. If Harun was a mere rook then Nicephorus to whom he should be paying tribute was a king and Harun’s superior. The caliph contemptuously wrote his response on the back of Nicephorus’ letter. To Nicephorus the Roman Dog, I have read your letter. Oh disloyal son. My answer will reach you sooner than you wish.

It was fighting talk and the caliph followed it up with an immediate invasion which Nicephorus was in no position to do anything about. The troops of the Anatolian themes were in revolt against him having declared their commander Bardanes Turcus as a rival emperor. Turcus himself claimed to be fighting on behalf of Irene and on news of her death he desisted in his revolt and voluntarily entered a monastery but a year later was blinded. Harun meanwhile had taken advantage of the chaos to pillage and burn his way through Cilicia. Nicephorus was left with little choice but to agree to a humiliating resumption of Irene’s tribute payments in order to secure a truce. Harun could have asked for nothing better. Hostilities were resumed the following year and resulted in a defeat for Nicephorus when he was ambushed and barely escaped with his life at the battle of Krasos thanks to the efforts of his officers.

Chess - a perfect analogy for diplomacy?

Chess - a perfect analogy for diplomacy?Now however it was the caliph’s turn to be distracted by internal dissent at the far end of his empire. Complaints reached Harun concerning the conduct of his governor of Khurasan Ali ibn Isa, an incompetent extortionist he had appointed in place of Fadl the Barmakid predominantly because he was a rival of the family. Harun decided to visit the province in person to discover the truth and he agreed a truce with Nicephorus in exchange for more tribute. In 805 he set out for Rayy. Here he met with Ali and found himself persuaded by rich gifts and sweet words that all was well. He confirmed his governor in his post and then found himself hitting the roof once more when news arrived that Nicephorus had taken advantage of his absence to breach the peace and had sacked the city of Tarsus as well as besieging Melitene and invading neutral Cyprus.

The following summer Harun led a massive invasion force reputed to be some 130,000 strong, an exaggeration to be sure but clearly the largest force sent across the border in living memory. Elements of the army advanced north as far as Ancyra whilst Harun settled down to besiege the fortified town of Heraclea in Cilicia, which proved to be a tough nut to crack. After two weeks of bombardment the town’s fortifications were still holding strong. On the seventeenth day a champion was sent out from Heraclea to challenge the Muslims to single combat and was defeated by an undistinguished volunteer from the ranks. Harun now resolved to terrorise the town into submission and rained flaming missiles down on the buildings within the walls. On the thirtieth day the populace abandoned their burning houses, threw open the gates and surrendered. The populace of Heraclea were taken away to be resettled as subjects of the caliph whilst the town was plundered and burned. Nicephorus meanwhile did no more than skirmish with isolated elements of the caliph’s forces and was overawed by the size of the army that the caliph had at his disposal. With the threat of further trouble on his western frontier from the Bulgars, Nicephorus had no choice but to make peace. He sent a deputation of churchmen to negotiate with the caliph who agreed to withdraw on resumption of an annual tribute of thirty thousand gold pieces, a promise not to rebuild Heraclea and a personal payment of the jizya poll tax of four gold pieces from the emperor himself, symbolic of his personal submission to the authority of the caliph. Nicephorus paid up. It was checkmate to Harun al Rashid.

Nicephorus found himself handing over plenty of these

Nicephorus found himself handing over plenty of theseHaving humbled the Byzantines, Harun once more turned his attention to Khurasan where a full scale revolt had now broken out against his governor Ali ibn Isa. The trouble had started in Samarkand when a local aristocrat was imprisoned for perfectly legitimate reasons but escaped and then whipped up a revolt in order to evade justice. The rebellion spread like wildfire through Transoxania and an army sent to restore order was defeated and the governor’s son killed. Harun dispatched an army from Baghdad to restore order under his most trusted general Harthama with orders to seize and depose the governor. This was done but the rebels still refused to return to the fold.

On receiving this news Harun decided to once more set out for the east himself. He charged his younger son Qasim with keeping an eye on the Byzantines from Raqqa and left his son Amin in charge in Baghdad. He then set out accompanied by Fadl ibn Rabi and his son Mamun, who was to take charge of his province, along with a vast entourage, making his slow progress towards Merv. The caliph was suffering from terrible stomach pains and knew that his days were numbered. By the time he reached Rayy it seemed unlikely that he would complete the journey. Mamun was sent on to Merv where his inheritance awaited and where he would reimpose control. Harun reached the town of Tus in northern Iran in March 809 and could go no further. Here on 24th March he died, aged forty three. He left his empire primed for chaos and when that chaos subsided nothing would quite be the same. In the centuries to follow, men would look back on his reign as an era of comparative peace and stability that would take on a golden hue and his reputation would attain that of a ruler of greatness. Was he truly great though, Dear Reader? I, for one, remain unconvinced.

Published on September 02, 2015 01:12

August 11, 2015

Harun al Rashid Part One - A Golden Age?

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights This post follows on from the previous Abbasid themed post Under the Black Banner which charted the rise to power of the Abbasid dynasty and the reign of Mansur, the founder of Baghdad. Following Mansur's death whilst on pilgrimage, his son Mahdi was confirmed on the spot as the new caliph.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights This post follows on from the previous Abbasid themed post Under the Black Banner which charted the rise to power of the Abbasid dynasty and the reign of Mansur, the founder of Baghdad. Following Mansur's death whilst on pilgrimage, his son Mahdi was confirmed on the spot as the new caliph. Mahdi was a more chilled out character than his formidable father Mansur. He liked girls, poetry and the occasional glass of wine with meals. This did not make him dissolute, however. Rather he was perhaps more well rounded in his outlook and had been well prepared for rule by governing the east on his father’s behalf from the city of Rayy. Certainly his initial approach towards his subjects was conciliatory, having made the grisly discovery of the remains of dozens of members of the Alid family, men women and children, murdered by his father and hidden in a store room in Baghdad; each with a label attached to their ear identifying them. Mahdi had the remains buried in secret in a mass grave and the site promptly built over. He then reached out to the surviving Alids, pardoning some of those who had joined the rebellion of the Pure Soul and even appointed one of their sympathisers as his vizier. He then embarked on a programme of restoration of mosques throughout the caliphate, in the process stripping away much ostentation added in the pomp of the Umayyad dynasty and returning the interior of buildings to their original simplicity. In 777 he set out on the pilgrimage to Mecca with the intention of winning hearts and minds in the old country, dispensing much largesse and restoring the Kaaba. Accompanying him on this important expedition and making his first appearance on the public stage was Mahdi’s son Harun, imagined below as a young man. Mahdi had many sons by wives and concubines but only two mattered and these were the sons of the former slave girl Khayzuran, who he had freed and married on his accession. She was a legendary beauty who had the caliph wrapped around her delicate finger. Harun and his elder brother Musa were groomed from the beginning to succeed their father in turn. Harun appears to have been especially favoured and there is no doubt that he was his mother’s golden boy. For whatever reason, Khayzuran and her older son Musa were never close and instead she used her considerable influence on behalf of Harun. As tutor to his second son Mahdi appointed his best friend Yahya the Barmakid who cultivated a network of support around his young pupil as factions began to develop in the Abbasid court.

In 780 Harun accompanied his father on a military expedition as Mahdi set out to show himself not just a pious leader of the Muslims but a warlike one as well, committed to the pursuit of jihad against the infidel. The Byzantine commander Michael Lachanodrakon had led a successful invasion of northern Syria two years before, capturing the settlement of Marash whilst the Arab response had achieved nothing of note. Leaving Musa in charge in Baghdad, Mahdi escorted Harun to the frontier and then sent him off at the head of a small raiding force to win his spurs. The raid was a moderate success. A small fortified settlement was captured and plundered and the troops were back across the frontier before any serious opposition could be marshalled by the Byzantines. Meanwhile a larger force was sent further into imperial territory where it suffered a significant defeat at the hands of Lachanodrakon.

In 780 Harun accompanied his father on a military expedition as Mahdi set out to show himself not just a pious leader of the Muslims but a warlike one as well, committed to the pursuit of jihad against the infidel. The Byzantine commander Michael Lachanodrakon had led a successful invasion of northern Syria two years before, capturing the settlement of Marash whilst the Arab response had achieved nothing of note. Leaving Musa in charge in Baghdad, Mahdi escorted Harun to the frontier and then sent him off at the head of a small raiding force to win his spurs. The raid was a moderate success. A small fortified settlement was captured and plundered and the troops were back across the frontier before any serious opposition could be marshalled by the Byzantines. Meanwhile a larger force was sent further into imperial territory where it suffered a significant defeat at the hands of Lachanodrakon.Two years later Mahdi launched a much larger expedition intended to reassert the dominance of the caliphate. His timing was good, the empress Irene, pictured below, was in the midst of purging her forces of iconoclasts and the Arab forces could hope to take advantage of the dearth of leadership amongst the Byzantines. Over ninety thousand men were sent across the border under the overall command of Harun, accompanied by his father’s trusted ministers Rabi ibn Yunus and Yahya the Barmakid. Rather than confining his activities to the border regions, Harun pushed westwards into the Byzantine heartland, whilst Yahya took a portion of the army northward and inflicted a defeat upon Lachanodrakon. Harun’s army won another victory near Nicaea and then he advanced all the way to the shores of the Bosporus, from where he could look across the straits to the capital of the infidel. That however was as far as he could go and without a fleet to carry him across to Constantinople, his advance to the sea was largely symbolic. After much plundering Harun turned for home but now found that Rabi, who had been left to guard his lines of supply had been defeated and driven back. The young Abbasid prince now found himself trapped between two Byzantine armies close to Nicaea. The most famous caliph of them all could have been reduced to an obscure footnote right then and there but his luck was in. The Armenian commander Tatzates had reason to fear that he would soon become another victim of Irene’s purges and so he took the opportunity to defect, taking many of his troops with him. The Byzantines now decided to negotiate and Irene’s chief minister Stauracios ventured into the enemy camp at the head of a delegation. Harun, having given no promise of safe conduct and advised by Tatzates of the empress’ reliance on the eunuch, took the envoys prisoner. Desperate to secure the release of her favourite, Irene agreed a humiliating three year truce with the caliphate, allowing Harun to withdraw triumphantly, having secured an annual tribute of seventy thousand gold pieces and ten thousand pieces of silk.

Back in Baghdad the court poets praised Harun’s achievement to the skies, declaring that he had advanced to the walls of Constantinople itself and placed his spear against them before sparing the city in return for tribute. He was given the epithet of al Rashid – the right guided. Oaths were taken to him as the heir to his elder brother. The favoured son had done well but yet he was not the first in line. It may have been that Mahdi had decided to elevate his second son to first place when he set out along with Harun in 785 to visit his eldest son Musa at Gurgan beside the Caspian, where he was busy putting down a rebellion. On the way however, so one story goes, the caliph set out hunting and pursued a gazelle amongst some ruins. As his horse galloped below a lintel, the caliph, absorbed by the chase, forgot to duck and that was the end of Mahdi who was laid to rest beneath a nearby walnut tree. An alternative version has the caliph accidentally poisoned by one of his concubines who had sent a poisoned pear to a rival. Mahdi, taking a fancy to the fateful pear, intercepted it on its way and ate it. Take your pick, Dear Reader, either way the end result was the same.

Back in Baghdad the court poets praised Harun’s achievement to the skies, declaring that he had advanced to the walls of Constantinople itself and placed his spear against them before sparing the city in return for tribute. He was given the epithet of al Rashid – the right guided. Oaths were taken to him as the heir to his elder brother. The favoured son had done well but yet he was not the first in line. It may have been that Mahdi had decided to elevate his second son to first place when he set out along with Harun in 785 to visit his eldest son Musa at Gurgan beside the Caspian, where he was busy putting down a rebellion. On the way however, so one story goes, the caliph set out hunting and pursued a gazelle amongst some ruins. As his horse galloped below a lintel, the caliph, absorbed by the chase, forgot to duck and that was the end of Mahdi who was laid to rest beneath a nearby walnut tree. An alternative version has the caliph accidentally poisoned by one of his concubines who had sent a poisoned pear to a rival. Mahdi, taking a fancy to the fateful pear, intercepted it on its way and ate it. Take your pick, Dear Reader, either way the end result was the same. At this point Harun played the part of the faithful brother, sending his father’s signet ring to Musa whilst returning to Baghdad to restore order. The troops in the city who had rioted at news of the caliph’s death were quieted with a large payment from the treasury and Harun took oaths of loyalty from the great and the good in his brother’s name. As always Rabi and Yahya were at the heart of events, pulling strings and greasing wheels. Taking the name of Hadi, the new caliph marched back from the east in just twenty days to take control in Baghdad. Hadi was tough and aggressive, the darling of the military, whilst the more cultured Harun enjoyed the support of the court bureaucracy and he was of course his mother’s favourite. Khayzuran now wielded considerable power as the widow of Mahdi and the mother of Hadi and Harun. At her sumptuous palace on the east bank of the Tigris she received suppliants each day, begging for favours and appointments and soon it seemed that all the business of the state was in the hands of the former slave girl, much to the annoyance of the caliph. Finally Hadi issued a threat that anyone approaching his mother looking for advancement would lose his head instead. Anyone doubting his word had only to glance at the permanently drawn swords of his bodyguard to know that he meant business. Hadi, set out to further marginalise his mother and brother by seeking to alter the plan of succession in favour of his own son Jaffar, who was the preferred choice of many of the army commanders, disinheriting Harun. Hadi was advised against this action by Yahya the Barmakid who pointed out that if the sacred oaths taken to Harun were disregarded, then no oath would ever have the same binding effect again. This argument gave the caliph pause for a time but then he lost his patience and decided to act. Having successfully poisoned the vizier Rabi, who was a key ally of Khayzuran, he then tried to do the same to his mother. Khayzuran took the precaution of feeding the dish of rice he sent her to her dog. Finally Hadi declared that Jaffar would succeed him and demanded oaths of allegiance to be taken to his son. He then had Harun and Yahya the Barmakid arrested when they attempted to flee the court. At his moment of triumph however, the caliph fell foul of his mother who returned his compliment with greater subtlety, using her contacts amongst the caliph’s harem to have him poisoned and then suffocated with pillows as he lay ailing. He had reigned for just over a year. Khayzuran now used her own contacts in the military to secure Harun’s succession. Jaffar was dragged from his bed at sword point and forced to renounce his claim to the caliphate and Harun was duly installed as the new Commander of the Faithful without further opposition.

Yahya the Barmakid was a critical influence in Harun's succession There now dawned a golden age, so posterity would have us believe. Peace descended upon the Muslim world and Harun ruled wisely in sumptuous splendour and refinement, surrounded by poets and scholars. His reign is perceived, through the rose tinted distortion of later generations’ nostalgia, as the highpoint of Arab cultural and intellectual achievement. There is however a darker tale to be told which reveals Harun to be far from the Solomon-like right-guided ruler of legend. Strip away the romance of the Thousand and One Nights and we are left with an insecure, jealous, vicious and naive ruler.

Yahya the Barmakid was a critical influence in Harun's succession There now dawned a golden age, so posterity would have us believe. Peace descended upon the Muslim world and Harun ruled wisely in sumptuous splendour and refinement, surrounded by poets and scholars. His reign is perceived, through the rose tinted distortion of later generations’ nostalgia, as the highpoint of Arab cultural and intellectual achievement. There is however a darker tale to be told which reveals Harun to be far from the Solomon-like right-guided ruler of legend. Strip away the romance of the Thousand and One Nights and we are left with an insecure, jealous, vicious and naive ruler. The Abbasids had swept to power on a tide of popular support, stirred up by their man in Khurasan Abu Muslim. Restoration of the leadership of Islam to the family of the Prophet from the dissolute Umayyads had been their rallying call. The masses had looked to the revolution to bring about an improvement in their fortunes but Abbasid rule had in the end merely delivered more of what had gone before. Mansur had fulfilled some of the early promise of the dynasty, appearing before his people and hearing their complaints in person, although he had ruthlessly persecuted the Alids. Mahdi too had made some efforts at restoring the simplicity of the faith, although he had been more pleasure-loving than his austere father. Neither had done much to better the lot of the vast majority of their subjects however and both had faced rebellion, seemingly forgetful of the discontent that had brought them to power in the first place.

For the rural poor the burden of taxation was heavy and in most places a system of tax farming left tax collection up to private enterprise, whereby rapacious officials sought to wring as much personal profit out of the unfortunate tax payers as they could. The result was impoverishment of the peasant farmers, who often abandoned the land or were deprived of their property when they could not repay the loans they were forced to take out in order to pay their taxes, for which the whole community was collectively responsible. The land was snapped up by the wealthy and vast estates became the personal property of the ruling family and their cronies. This was nothing new of course. The story is a familiar and recurring one. Across the frontier in the Byzantine Empire the same situation existed but the plight of these small farmers as the backbone of the military was periodically addressed and the trend reversed. In the caliphate the peasant farmer played no military role and the soldiers who had come west with the conquerors from Khurasan, known as theabna, were maintained by the state.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights Far from being a period of peace, Harun’s reign saw the caliphate plagued by rebellion from end to end. As their discontent and disillusionment grew, the rural peasantry of the caliphate were attracted to new revolutionary movements, which sprang up like mushrooms, all of them promising to make the caliphate anew and deliver a fairer future. In the east of the empire a succession of movements fused elements from the pre-Islamic Persian past with more recent history. The old ideals of Mazdakism; a Zoroastrian ideology akin to communism which had been ruthlessly repressed by the Sassanid rulers of Persia, were given an Islamic make-over by associating them with the memory of Abu Muslim, the man of the people slain by the ungrateful Abbasids. The first leader of these movements was the so-called veiled prophet, a former lieutenant of Abu Muslim from Merv, who claimed to be a reincarnation of his murdered commander. He had hidden his face behind a green silk veil either because, according to his adherents, his face was so radiant that it could not be seen by mere mortals or, according to his enemies, he was one-eyed, bald and ugly. Whatever the truth, through revolutionary rhetoric and cheap conjuror’s tricks he amassed a great following and some sixty cities in Khurasan and Transoxania joined his cause. The veiled prophet had been finally run to ground and had taken his own life in 779 but he spawned a succession of imitators whom the credulous peasantry were prepared to follow in the hope of a better lot in life. The cult of the Alids too was linked to ideals of social reform, for Ali had been the champion of the ordinary people and had stood for the equality of all Muslims. A rebellion raised in Medina in 786 by the Alid Yahya ibn Abdullah had garnered only lukewarm support following the good works of Mahdi and Khayzuran in the region. Evading capture, the rebel moved onto Daylam; the region south of the Caspian and here succeeded in sparking a widespread popular revolt. He was finally persuaded to give himself up in 792 whereupon he was promptly murdered. In many places across the caliphate, those perennial malcontents the Kharijites were resurgent, rejecting the authority of the caliph and condemning the luxury of his court. A Kharijite led rebellion began in northern Iraq shortly after Harun’s accession and then the rebels marched north into Azerbaijan and overran the province for a period of two years before they were finally put down. In Egypt there were repeated uprisings beginning in 789 in protest at the increases in land taxes. The rebels were crushed by pouring troops into the region before the taxes were increased again, sparking further revolt. When Harun decided to cut the pay of the troops stationed in Egypt they joined in with the rebels and burned the city of Fustat to the ground.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights Far from being a period of peace, Harun’s reign saw the caliphate plagued by rebellion from end to end. As their discontent and disillusionment grew, the rural peasantry of the caliphate were attracted to new revolutionary movements, which sprang up like mushrooms, all of them promising to make the caliphate anew and deliver a fairer future. In the east of the empire a succession of movements fused elements from the pre-Islamic Persian past with more recent history. The old ideals of Mazdakism; a Zoroastrian ideology akin to communism which had been ruthlessly repressed by the Sassanid rulers of Persia, were given an Islamic make-over by associating them with the memory of Abu Muslim, the man of the people slain by the ungrateful Abbasids. The first leader of these movements was the so-called veiled prophet, a former lieutenant of Abu Muslim from Merv, who claimed to be a reincarnation of his murdered commander. He had hidden his face behind a green silk veil either because, according to his adherents, his face was so radiant that it could not be seen by mere mortals or, according to his enemies, he was one-eyed, bald and ugly. Whatever the truth, through revolutionary rhetoric and cheap conjuror’s tricks he amassed a great following and some sixty cities in Khurasan and Transoxania joined his cause. The veiled prophet had been finally run to ground and had taken his own life in 779 but he spawned a succession of imitators whom the credulous peasantry were prepared to follow in the hope of a better lot in life. The cult of the Alids too was linked to ideals of social reform, for Ali had been the champion of the ordinary people and had stood for the equality of all Muslims. A rebellion raised in Medina in 786 by the Alid Yahya ibn Abdullah had garnered only lukewarm support following the good works of Mahdi and Khayzuran in the region. Evading capture, the rebel moved onto Daylam; the region south of the Caspian and here succeeded in sparking a widespread popular revolt. He was finally persuaded to give himself up in 792 whereupon he was promptly murdered. In many places across the caliphate, those perennial malcontents the Kharijites were resurgent, rejecting the authority of the caliph and condemning the luxury of his court. A Kharijite led rebellion began in northern Iraq shortly after Harun’s accession and then the rebels marched north into Azerbaijan and overran the province for a period of two years before they were finally put down. In Egypt there were repeated uprisings beginning in 789 in protest at the increases in land taxes. The rebels were crushed by pouring troops into the region before the taxes were increased again, sparking further revolt. When Harun decided to cut the pay of the troops stationed in Egypt they joined in with the rebels and burned the city of Fustat to the ground. In the administration of his empire Harun continued to rely primarily on the Barmakids. His old tutor Yahya would serve as Harun’s vizier whilst Yahya’s two sons Fadl and Jaffar, who was the caliph’s closest friend and favourite companion, held a succession of important offices of state and were trusted with the governorship of large territories. Fadl in particular would prove to be a capable administrator during his time as governor of Khurasan; quelling rebellion, ploughing funds into improving infrastructure, curbing the worst excesses of the tax collectors and winning hearts and minds, whilst keeping up the flow of funds to the treasury. The primary interest of the Barmakids however remained the feathering of their own nests and the strengthening of their own network of support.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights For many years Harun was content to let them get on with it. He kept up the conspicuous acts of piety expected of a caliph by dispatching the yearly raids, known as razias, across the frontier into Byzantine territory and undertaking the hajj on no less than eight occasions during his reign. Harun remained however, for the overwhelming majority of the time, in glorious isolation and devoted to pleasure. The caliph, his wives and concubines, his mother and relatives, his administrators and courtiers and hangers-on lived in a world of opulent palaces, exquisite gardens and massive excess. The quantities of wealth that were thrown around were obscene. Harun’s favourite wife Zubayda ate from golden plates, wore so many jewels that she could not walk unaided and had a staff of twenty simply to care for her pet monkey. She rewarded flatterers by filling their mouths with pearls. His mother Khayzuran had a reputation for pious works, financing shrines and way-stations along the pilgrimage route to Mecca. As such she was popular. Her personal wealth was immense however. As one of the greatest landowners in the caliphate she spent vast sums on land improvement and irrigation, although primarily for her own benefit and half of the land tax revenue of the caliphate is rumoured to have flowed straight into her coffers. When in a more frivolous mood, Khayzuran could spend up to fifty thousand dinars on a single piece of material and is said to have owned eighteen thousand dresses at the time of her death in 789. Such excess was not the preserve of the court women. Harun once rewarded an amusing poem by his feckless brother Ibrahim with a gift of a million dirhams from the treasury and showered his coterie of nadim; intelligent, cultured and witty drinking companions with palaces, wealth and status. Outside of the royal family the Barmakids enjoyed almost comparable wealth and practiced similar largesse.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights For many years Harun was content to let them get on with it. He kept up the conspicuous acts of piety expected of a caliph by dispatching the yearly raids, known as razias, across the frontier into Byzantine territory and undertaking the hajj on no less than eight occasions during his reign. Harun remained however, for the overwhelming majority of the time, in glorious isolation and devoted to pleasure. The caliph, his wives and concubines, his mother and relatives, his administrators and courtiers and hangers-on lived in a world of opulent palaces, exquisite gardens and massive excess. The quantities of wealth that were thrown around were obscene. Harun’s favourite wife Zubayda ate from golden plates, wore so many jewels that she could not walk unaided and had a staff of twenty simply to care for her pet monkey. She rewarded flatterers by filling their mouths with pearls. His mother Khayzuran had a reputation for pious works, financing shrines and way-stations along the pilgrimage route to Mecca. As such she was popular. Her personal wealth was immense however. As one of the greatest landowners in the caliphate she spent vast sums on land improvement and irrigation, although primarily for her own benefit and half of the land tax revenue of the caliphate is rumoured to have flowed straight into her coffers. When in a more frivolous mood, Khayzuran could spend up to fifty thousand dinars on a single piece of material and is said to have owned eighteen thousand dresses at the time of her death in 789. Such excess was not the preserve of the court women. Harun once rewarded an amusing poem by his feckless brother Ibrahim with a gift of a million dirhams from the treasury and showered his coterie of nadim; intelligent, cultured and witty drinking companions with palaces, wealth and status. Outside of the royal family the Barmakids enjoyed almost comparable wealth and practiced similar largesse. Despite inhabiting a world of palaces and gardens, Harun nevertheless tired of Baghdad. He disliked the heat and the proximity of the bustling masses and in 796 he established a new capital at Raqqa to the north. Here he could withdraw, accompanied by his household and his favourites and spend his days playing polo, hunting and practicing archery and his evenings in the convivial companionship of his nadim, enjoying poetry, discussion and chess. Raqqa was also closer to the frontier and Harun was once more taking a serious interest in war against the Byzantines. In 797 he sought to reprise the glorious campaign of his youth and once more crossed the frontier in person. He had chosen his moment perfectly for the empire was in a state of unrest. The empress Irene had just blinded and killed her son Constantine and her grip on power was tenuous whilst the loyalty of her armies was uncertain. The Byzantine response to Harun’s invasion was muted in the extreme and the caliph’s forces once more spread out into enemy territory with one column penetrating as far as Ephesus on the Aegean coast. Panicked, Irene sued for peace once more, agreeing to similarly humiliating terms as she had in 782 and Harun’s triumphant forces marched home unmolested, laden down with plunder.

The embassy of Charlemagne to Harun al Rashid Back in Raqqa, Harun now received an embassy from Charles, king of the Franks. Charles had little to offer Harun, who as the richest and most powerful ruler in the world vastly outstripped him in wealth and territory. If Charles already harboured pretentions towards the imperial crown of the west however, then establishing good relations with the greatest enemy of the eastern Roman Empire was a sound strategic move in the event of hostilities with Byzantium. For his part Harun welcomed a potential ally who could harass his sworn foes but was too far away to pose any threat to himself. Having given certain assurances concerning the safety of pilgrims visiting the Christian holy places in his territory, the caliph sent the envoys on their way laden down with gifts and accompanied by an elephant. The elephant, named Abul Abbas, made his way through north Africa and Italy, accompanied by the only member of the delegation to survive the return journey, arriving in Charles’ capital Aachen in 802. He lived for another eight years as a major celebrity at the Frankish court.

The embassy of Charlemagne to Harun al Rashid Back in Raqqa, Harun now received an embassy from Charles, king of the Franks. Charles had little to offer Harun, who as the richest and most powerful ruler in the world vastly outstripped him in wealth and territory. If Charles already harboured pretentions towards the imperial crown of the west however, then establishing good relations with the greatest enemy of the eastern Roman Empire was a sound strategic move in the event of hostilities with Byzantium. For his part Harun welcomed a potential ally who could harass his sworn foes but was too far away to pose any threat to himself. Having given certain assurances concerning the safety of pilgrims visiting the Christian holy places in his territory, the caliph sent the envoys on their way laden down with gifts and accompanied by an elephant. The elephant, named Abul Abbas, made his way through north Africa and Italy, accompanied by the only member of the delegation to survive the return journey, arriving in Charles’ capital Aachen in 802. He lived for another eight years as a major celebrity at the Frankish court. Harun appeared to be a man in control. He had overcome numerous rebels and malcontents, he had humiliated the empress and vast amounts of wealth were pouring into his treasury. But was he really in charge? It was time to make some very big decisions and show everyone who was boss.

To be continued.

Published on August 11, 2015 02:33

July 22, 2015

Born in the Purple Too

You never know what's coming next on Slings and Arrows, I've blogged about everything from dinosaurs to the space race. If it happened in the past it is fair game as far as I'm concerned but there is method in the madness. The general idea is that the blog is a roughly 50/50 split between continuing the Byzantine/Abbasid historical narrative from where my book The Battles are the Best Bits left off in 750 AD and completely random historical topics. This post follows on directly from the last Byzantine post Born in the Purple which charted the early part of the reign of Constantine VII. He had ruled in name only, dominated first by his mother and later by the usurper Romanus Lecapenus. Having finally got his hands on the reins of power at the age of 39 with the aid of the powerful, aristocratic Phocas clan, what sort of emperor would Constantine be after so many years on the sidelines?

Constantine Porphyrogenitus, depicted below, could never be described as a man of action. He is best known for a long and dull treatise on court ceremonial which is a treasure trove of information on the intricacies of the complex Byzantine socio-political hierarchy and for another on the administration of the empire, dedicated to his son Romanus. Preferring the pen to the sword, Constantine allowed the frontier to enjoy a period of peace rather than keeping up the momentum against the caliphate, which remained plagued by infighting between its regional warlords for control of the increasingly irrelevant caliph. The empire's principle antagonist amongst these warlords remained Sayf al Dawla, 'the Sword of the Dynasty' now established as Emir of Aleppo. Sayf al Dawla was occupied in a struggle to wrest control of Syria from al Ikhshid, governor of Egypt, who ruled the country as a personal fiefdom. The fortunes of war ebbed and flowed between these two. Sayf al Dawla twice took Damascus from al Ikhshid and twice lost it, as well as losing and regaining his own capital, before at last a treaty of peace recognised that perhaps the status quo, with Syria divided between them, was the best solution for both of them.In 949 the offensive against the caliphate was resumed in earnest. Porphyrogenitusset his eye upon the perennial reconquest objective of Crete and assembled an invasion fleet. The force sent to the island however was woefully inadequate in terms of both manpower and leadership. It was an expedition launched on the cheap and the predictable consequence was its failure. Despite landing unopposed, the force of 4000 soldiers were attacked and overrun in their poorly defended camp. The bedraggled survivors returned to Constantinople in disgrace. Warfare on the frontier between Byzantium and the Caliphate, effectively represented by the Emir of Aleppo, had in recent decades been waged with limited objectives. Permanent seizure of major settlements and large tracts of territory was certainly not the aim of Sayf al Dawla since he lacked the resources to hold on to such gains. Instead the aims of his razias or border raids were essentially threefold. Firstly he sought to limit the ability of his Byzantine enemies to make war upon him in turn by looting and destroying border fortifications and settlements. Secondly he sought to enrich himself and his followers by plundering the lands and settlements of the enemy and thirdly he sought to fulfil the obligation of jihad by making war upon the infidel. The promise of rewards both heavenly and earthly drew many volunteers to his banners during the campaigning season, swelling his numbers with irregulars, fired up with religious zeal and eager for booty.

The empire's principle antagonist amongst these warlords remained Sayf al Dawla, 'the Sword of the Dynasty' now established as Emir of Aleppo. Sayf al Dawla was occupied in a struggle to wrest control of Syria from al Ikhshid, governor of Egypt, who ruled the country as a personal fiefdom. The fortunes of war ebbed and flowed between these two. Sayf al Dawla twice took Damascus from al Ikhshid and twice lost it, as well as losing and regaining his own capital, before at last a treaty of peace recognised that perhaps the status quo, with Syria divided between them, was the best solution for both of them.In 949 the offensive against the caliphate was resumed in earnest. Porphyrogenitusset his eye upon the perennial reconquest objective of Crete and assembled an invasion fleet. The force sent to the island however was woefully inadequate in terms of both manpower and leadership. It was an expedition launched on the cheap and the predictable consequence was its failure. Despite landing unopposed, the force of 4000 soldiers were attacked and overrun in their poorly defended camp. The bedraggled survivors returned to Constantinople in disgrace. Warfare on the frontier between Byzantium and the Caliphate, effectively represented by the Emir of Aleppo, had in recent decades been waged with limited objectives. Permanent seizure of major settlements and large tracts of territory was certainly not the aim of Sayf al Dawla since he lacked the resources to hold on to such gains. Instead the aims of his razias or border raids were essentially threefold. Firstly he sought to limit the ability of his Byzantine enemies to make war upon him in turn by looting and destroying border fortifications and settlements. Secondly he sought to enrich himself and his followers by plundering the lands and settlements of the enemy and thirdly he sought to fulfil the obligation of jihad by making war upon the infidel. The promise of rewards both heavenly and earthly drew many volunteers to his banners during the campaigning season, swelling his numbers with irregulars, fired up with religious zeal and eager for booty.

The court of Sayf al Dawla - Skylitzes Chronicle The year 950 saw Sayf al Dawla assemble an unusually large force bolstered by jihadi volunteers, numbering some thirty thousand men, which he led across the border in a more ambitious raid than usual. He defeated a force under Bardas Phocas in eastern Armenia before turning for home, laden with plunder. It was now however that the Byzantine strategy for countering cross border invasions came into play. The defensive approach taken in this period and employed successfully on several occasions against Sayf al Dawla and his lieutenants was known as shadowing. With advance intelligence of enemy movements provided by a network of spies and look outs, the Byzantine commanders employed as much as possible a scorched earth policy in the face of the enemy advance. Civilians were evacuated, valuables and livestock removed and crops burned. The enemy was closely followed by small, mobile forces and his foragers and scouts harassed as he made his way through the valleys from settlement to settlement in search of loot. Generally, the Byzantines did not seek a major engagement at this time; allowing the razia to continue and merely attempting to limit the enemy's opportunities to plunder and forage. Sources of fresh water vital to the enemy were defended where possible by the shadowing forces. Meanwhile, the Byzantines gathered their full strength. The defenders were typically spread across numerous small garrisons throughout the frontier region but as the return route to be taken by the invader was discerned, these forces coalesced into an army which could be deployed in ambush at some suitably constricted point. So it was on this occasion that when Sayf al Dawla was making his way homeward, his forces heavily laden with booty, an ambush was sprung in a mountain pass between Lycandus and Germanicea by Leo Phocas, son of Bardas. Caught in a very bad position, Sayf al Dawla barely escaped with his life, losing 8000 men and most of his ill-gotten gains in the process. It was remembered by Sayf and his followers as ‘the dreadful expedition’ although it did not discourage him from raiding again the following year.Byzantine offensive strategy was similarly limited in its scope. Raids were launched with the aim of securing modest territorial gains in the frontier region if possible but more importantly to reduce the enemy’s ability to launch raids by taking and destroying his settlements and fortifications, inflicting casualties and taking plunder. In the years following the dreadful expedition, Bardas Phocas proved himself inept at these tactics, repeatedly being defeated by Sayf al Dawla, who was seemingly unbeatable on his home ground. Meanwhile, Byzantine efforts to make gains in southern Italy met only with defeats and further loss of territory.

The court of Sayf al Dawla - Skylitzes Chronicle The year 950 saw Sayf al Dawla assemble an unusually large force bolstered by jihadi volunteers, numbering some thirty thousand men, which he led across the border in a more ambitious raid than usual. He defeated a force under Bardas Phocas in eastern Armenia before turning for home, laden with plunder. It was now however that the Byzantine strategy for countering cross border invasions came into play. The defensive approach taken in this period and employed successfully on several occasions against Sayf al Dawla and his lieutenants was known as shadowing. With advance intelligence of enemy movements provided by a network of spies and look outs, the Byzantine commanders employed as much as possible a scorched earth policy in the face of the enemy advance. Civilians were evacuated, valuables and livestock removed and crops burned. The enemy was closely followed by small, mobile forces and his foragers and scouts harassed as he made his way through the valleys from settlement to settlement in search of loot. Generally, the Byzantines did not seek a major engagement at this time; allowing the razia to continue and merely attempting to limit the enemy's opportunities to plunder and forage. Sources of fresh water vital to the enemy were defended where possible by the shadowing forces. Meanwhile, the Byzantines gathered their full strength. The defenders were typically spread across numerous small garrisons throughout the frontier region but as the return route to be taken by the invader was discerned, these forces coalesced into an army which could be deployed in ambush at some suitably constricted point. So it was on this occasion that when Sayf al Dawla was making his way homeward, his forces heavily laden with booty, an ambush was sprung in a mountain pass between Lycandus and Germanicea by Leo Phocas, son of Bardas. Caught in a very bad position, Sayf al Dawla barely escaped with his life, losing 8000 men and most of his ill-gotten gains in the process. It was remembered by Sayf and his followers as ‘the dreadful expedition’ although it did not discourage him from raiding again the following year.Byzantine offensive strategy was similarly limited in its scope. Raids were launched with the aim of securing modest territorial gains in the frontier region if possible but more importantly to reduce the enemy’s ability to launch raids by taking and destroying his settlements and fortifications, inflicting casualties and taking plunder. In the years following the dreadful expedition, Bardas Phocas proved himself inept at these tactics, repeatedly being defeated by Sayf al Dawla, who was seemingly unbeatable on his home ground. Meanwhile, Byzantine efforts to make gains in southern Italy met only with defeats and further loss of territory.

Sayf al Dawla flees the field of battle -- Skylitzes Chronicle In 953, Sayf al Dawla avenged the dreadful expedition by turning the tables on the Byzantines. Having mounted a successful raid into Byzantine territory and on this occasion managing to avoid the ambush set for him by Constantine Phocas, the youngest son of Bardas, Sayf al Dawla managed to march safely back to his home territory by a circuitous route. He then turned the tables by intercepting a counter raid led by Bardas and Constantine which had penetrated deep into his territory and was now returning. At the battle of Marash, fought in northern Syria, the Emir of Aleppo, who is improbably credited with achieving the feat with just 600 men, inflicted a crushing defeat upon Bardas, from which he barely escaped with his life and with a severe wound to his face. His son Constantine was captured in the battle and paraded through the streets of Aleppo, where he later died in captivity.Following this defeat, the emperor had tired of Bardas’ bungling and replaced him as Domestic of the Scholae with his son Nicephorus. Citing his wound to maintain his honour, Bardas retired with dignity intact. The new domestic earned a brief reprieve whilst Sayf al Dawla had his hands full with a tribal revolt. By a mixture of diplomacy and ferocity, Sayf al Dawla pursued a policy of divide and conquer, driving some tribes into the desert to starve whilst winning others to his side with the promise of the lands and property of the vanquished. By 956 he was once more the master of his own territories but was now facing a renewed challenge from Nicephorus Phocas, who sent the promising young Armenian general John Tzimisces to seize the city of Amida. Sayf al Dawla launched a successful counter raid into Byzantine Mesopotamia, which saw the governor’s palace at Harput burned and large numbers of captives taken. Avoiding the principle ambushing force which had moved in behind him, Sayf al Dawla’s force then managed to fight their way through another pass, which the returning Tzimisces had occupied, routing the Byzantine forces with heavy losses and capturing their baggage. Whilst he had his hands full however, Leo Phocas had led another raid into his territory, defeating and capturing his cousin, who was paraded in Constantinople. The following year Nicephorus led a campaign to destroy the crucial border stronghold of Adata. Meanwhile he employed intrigue to undermine any counter-moves that the Emir might make. As he made his preparations, Sayf al Dawla discovered that a group of his followers had accepted a Byzantine bribe to capture him and hand him over to Nicephorus. Furious, he abandoned his campaign and returned to Aleppo to root out the conspiracy, killing or mutilating over 300 of his bodyguards in a brutal purge.

Sayf al Dawla flees the field of battle -- Skylitzes Chronicle In 953, Sayf al Dawla avenged the dreadful expedition by turning the tables on the Byzantines. Having mounted a successful raid into Byzantine territory and on this occasion managing to avoid the ambush set for him by Constantine Phocas, the youngest son of Bardas, Sayf al Dawla managed to march safely back to his home territory by a circuitous route. He then turned the tables by intercepting a counter raid led by Bardas and Constantine which had penetrated deep into his territory and was now returning. At the battle of Marash, fought in northern Syria, the Emir of Aleppo, who is improbably credited with achieving the feat with just 600 men, inflicted a crushing defeat upon Bardas, from which he barely escaped with his life and with a severe wound to his face. His son Constantine was captured in the battle and paraded through the streets of Aleppo, where he later died in captivity.Following this defeat, the emperor had tired of Bardas’ bungling and replaced him as Domestic of the Scholae with his son Nicephorus. Citing his wound to maintain his honour, Bardas retired with dignity intact. The new domestic earned a brief reprieve whilst Sayf al Dawla had his hands full with a tribal revolt. By a mixture of diplomacy and ferocity, Sayf al Dawla pursued a policy of divide and conquer, driving some tribes into the desert to starve whilst winning others to his side with the promise of the lands and property of the vanquished. By 956 he was once more the master of his own territories but was now facing a renewed challenge from Nicephorus Phocas, who sent the promising young Armenian general John Tzimisces to seize the city of Amida. Sayf al Dawla launched a successful counter raid into Byzantine Mesopotamia, which saw the governor’s palace at Harput burned and large numbers of captives taken. Avoiding the principle ambushing force which had moved in behind him, Sayf al Dawla’s force then managed to fight their way through another pass, which the returning Tzimisces had occupied, routing the Byzantine forces with heavy losses and capturing their baggage. Whilst he had his hands full however, Leo Phocas had led another raid into his territory, defeating and capturing his cousin, who was paraded in Constantinople. The following year Nicephorus led a campaign to destroy the crucial border stronghold of Adata. Meanwhile he employed intrigue to undermine any counter-moves that the Emir might make. As he made his preparations, Sayf al Dawla discovered that a group of his followers had accepted a Byzantine bribe to capture him and hand him over to Nicephorus. Furious, he abandoned his campaign and returned to Aleppo to root out the conspiracy, killing or mutilating over 300 of his bodyguards in a brutal purge.