Simon B. Jones's Blog: Slings and arrows, page 6

June 20, 2013

Attila the Hun - Original Gangster

In 378 AD the Roman Empire suffered one of the most ignominious defeats in its long history with the annihilation of Emperor Valens' army at the hands of Fritigern’s Goths at Adrianople. It was a defeat in which the emperor himself perished. The Goths themselves however had of course been seeking refuge in imperial lands; fleeing from an even greater menace.

The dreaded Huns

The dreaded HunsOn the River Dniester some years before, far from the Roman frontier, the Gothic tribe of the Greuthungi had suffered their own crushing defeat in which two of their kings had fallen in battle. The Greuthungi had come under attack from a barbarian people who had exploded out of the Eastern Steppe and who seemed utterly unstoppable. These were the Huns; fierce nomadic tribesmen who practically lived in the saddle and were peerless in the art of fighting on horseback. They are described in Roman sources as being barely human; hideously ugly, bow legged from a lifetime on horseback and dressed in filthy, reeking clothes which were made improbably from the skins of mice. No one knew where the Huns had come from since that part of the known world from which they had appeared was a blank on the map. It has been suggested that they were descended from the Xiongnu; a fearsome nomadic people who had so terrorised the Chinese some centuries before that they had inspired the construction of the original Great Wall.

Whilst the Romans and even the Goths were happy to dismiss the Huns as savages, they soon learned to respect their martial prowess. In around 350 the Huns had crossed the Volga, initially in small raiding parties and then in greater numbers. They had smashed the power of the nomadic Alans who were tough warriors in their own right; sending them fleeing westwards. Now the Huns were moving into the territory of the Goths. Athanaric the leader of the Tervingi; another Gothic tribe who neighboured the Greuthungi to their west, had attempted to stand and fight but was driven back to the old defensive lines which had once protected the Roman province of Dacia. Still the Huns came on.

The Huns were a pastoral people accustomed to survival in the unforgiving environment of the Eastern Steppe and they were self-sufficient and hardy. From early childhood, every Hunnic boy would learn the skills essential to a life of driving livestock from one place to another and of hunting and raiding. He would learn to ride almost before he could walk and soon after would begin to learn to use a bow so that by the time he reached adulthood he would be an expert horseman and archer.

The Hunnic bow was the most powerful yet seen. It was a compound recurve bow with an unusual asymmetric design being shorter at the bottom to allow it to be used more easily from horseback. Based on the best efforts of modern re-enactment, Hunnic warriors could fire perhaps as many as thirty arrows per minute from horseback at speed. An army facing the Huns in battle would find itself facing a maelstrom of galloping horsemen who would fire arrow after arrow into their lines as they rode along them before wheeling away to resupply from carts in the Hunnic rear. Fresh horsemen would then take their place and continue the deadly hail of iron tipped shafts which were sent whistling through the air with enough power to pierce armour from a range at which their enemies’ counter fire was barely effective. The modern historian John Man has calculated that a force of a thousand Huns fighting in this way could unleash a rate of fire of twelve thousand shots per minute. The peoples whom they faced simply had nothing to match that kind of firepower. At close quarters the Huns employed the skills learned in rounding up horses on the steppe and wielded lassoes with which they ensnared their opponents before running them through with the sword.

With large numbers of Goths driven into imperial territory, where they would continue to have a cataclysmic impact culminating in Alaric’s sack of Rome in 410, the way was clear for the Huns to become the major power in the lands beyond the Danube. The disparate Hunnic groups under their own leaders and the Germanic populations who had chosen to remain in their lands and become subjects of the Huns rather than take their chances as migrants had been gradually drawn into the gravitational pull of an increasingly powerful and proportionally shrinking number of Hunnic warlords. This dog eat dog process of absorption of the weaker by the stronger continued towards its logical conclusion until the entire vast domain of the Huns, stretching from the shores of the Black Sea to the banks of the Elbe, was controlled by just two men who happened to be brothers. Their names were Attila and Bleda. The fact that Bleda the Hun is not a household name suggests his likely fate at the hands of his more famous brother.

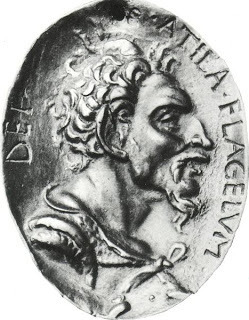

Attila the Hun

Attila the HunThe Hunnic Empire under Attila and Bleda operated as a giant protection racket. The Huns threatened to smash up the Danube provinces of the eastern empire unless the level of yearly tribute previously agreed with their Uncle Rua, who had bequeathed them their empire, was doubled from three hundred to seven hundred pounds of gold. The Romans agreed to this and then the Huns attacked anyway. Unlike previous barbarian invaders the Huns had mastered the siege craft necessary to take walled cities and had now added rams, towers and scaling ladders to their fearsome military repertoire. The cities of Margus, Vimanaceum, Sirmium, Constantia and Singidunum which is now Belgrade were all taken, plundered and reduced to smouldering rubble. Their people were led away into slavery. In the peace agreement of 442 which was concluded outside the blackened ruins of Margus where the whitening bones of the slaughtered still lay scattered over the ground, the Romans agreed to a further doubling of the tribute to fourteen hundred pounds of gold. The Huns did not even bother to dismount during the negotiations.

Two years later Attila disposed of his brother and assumed sole control of operations. Dispensing the vast quantities of loot from the eastern empire with great largesse he kept the leaders of his subject peoples on side with gifts of fine clothes, silver plate and elaborate weapons. As the Huns still lived an essentially nomadic existence there was not really much else to spend it all on, although one of Attila’s deputies had himself a Roman bath house constructed at one of the permanent royal settlements that Attila had established throughout his domains. Attila himself preferred substance to style and affected a simplicity in his dress and possessions, leaving it to his followers to outdo each other with bling. Like any good gangster Attila the Hun rewarded loyalty with generosity and swiftly eliminated any whom he had reason to suspect. Under the terms of the treaty, the Romans were obliged to return any of his subjects who sought asylum in their lands to face an immediate and nasty death by impalement. Like all successful empire builders Attila understood that fear and violence, magnanimity and generosity were all tools to be employed as the situation demanded. He kept the leaders of his subject peoples close by him, as honoured members of his inner circle, where he could keep an eye on them.

In 447 Attila was obliged to march into the eastern empire once again when the Eastern Emperor Theodosius II suspended tribute payments. This time the Huns raided as far south as Thermopylae and even threatened the walls of Constantinople itself although the mighty land walls, which had been hurriedly shored up following an earthquake, were formidable enough to deter the Huns. Two heavy defeats in the field and the destruction of more cities soon persuaded Theodosius to resume payments. Predictably, the amount of tribute demanded by Attila was again doubled.

Determined to free the empire from the menace of Attila, the imperial chamberlain in Constantinople; a eunuch by the name of Chrysaphius, decided to employ some gangster tactics of his own. Taking aside a member of a Hunnic delegation, Chrysaphius attempted to bribe one of Attila’s most trusted henchmen to arrange the murder of his master whilst accompanying Roman diplomats on an embassy to the Huns. This plan backfired spectacularly as the would-be assassin agreed to the plot but then reported the Romans’ intentions immediately to Attila upon his return. The Roman delegation’s translator was apprehended by the Huns whilst bringing the money to pay for the hit. Having caught the Romans red handed Attila enjoyed the moment; dispatching an embassy to Constantinople to publically castigate Theodosius in his own court, admonishing him as an unworthy and dishonourable vassal who had raised his hand against his rightful lord.

Attila's court In 450 the weak willed Theodosius II died and was succeeded by his Master of Soldiers Marcian who strengthened his claim to the purple by marrying Theodosius’ sister Pulcheria, who had always been the power behind her brother’s throne. The more militarily minded Marcian immediately declared that gold was for his friends whilst iron was for his enemies. There would be no more payments made to the Huns. Attila, ever the opportunist, decided that he had milked the eastern empire for long enough and that easier pickings could be found by now turning against the poorly defended west rather than by picking a fight with the defiant Marcian. Attila had an interesting pretext for making war on the west, for he had received an offer of marriage from the Princess Honoria, the sister of Western Emperor Valentinian III.

Attila's court In 450 the weak willed Theodosius II died and was succeeded by his Master of Soldiers Marcian who strengthened his claim to the purple by marrying Theodosius’ sister Pulcheria, who had always been the power behind her brother’s throne. The more militarily minded Marcian immediately declared that gold was for his friends whilst iron was for his enemies. There would be no more payments made to the Huns. Attila, ever the opportunist, decided that he had milked the eastern empire for long enough and that easier pickings could be found by now turning against the poorly defended west rather than by picking a fight with the defiant Marcian. Attila had an interesting pretext for making war on the west, for he had received an offer of marriage from the Princess Honoria, the sister of Western Emperor Valentinian III.Valentinian was another weak willed emperor who had initially been dominated by his mother, the formidable empress Galla Placidia and then presided as little more than a figure head as a trio of warlords divided up responsibility for the governance and protection of the western empire, although predictably they had soon fallen to fighting amongst themselves.

The man who eventually prevailed in this struggle to become de facto leader and protector of the west was Flavius Aetius. Aetius was well connected in barbarian circles, having spent time as a boy as a political hostage to both the Goths and the Huns. He was appointed initially to the Gallic command where he faced barbarian incursions on all fronts and where the footprint of Roman imperial control was steadily shrinking. The south-west had been gifted to the Visigoths whilst in Brittany a rebel state now existed where the locals had taken matters into their own hands and no longer recognised the sovereignty of Rome. To the north the Franks had occupied the Belgic provinces and on the Rhine frontier another Germanic group known as the Burgundians were encroaching onto Roman territory. Aetius thus had plenty to keep him busy and scant resources with which to defend his patch. As a result he relied heavily on his connections amongst the Huns in order to bolster his forces with large numbers of Hunnic mercenaries. These additional troops proved a decisive advantage, allowing Aetius to keep his various enemies at bay. He had been powerless however to prevent the loss of Roman North Africa to the predations of the Vandals under their swashbuckling king Gaiseric. In 439 the Vandals had taken Carthage and the rich province of Africa Proconsularis had been lost. This was a disaster which constituted a very large nail in the coffin of the Western Roman Empire.

Getting back to Honoria; having found her freedom curtailed following a series of scandalous liaisons culminating in an embarrassing pregnancy, the princess wrote to Attila; sending him a ring and imploring him to rescue her. This improbable turn of fortune prompted Attila to demand that Valentinian should hand over his sister to be the latest bride of the King of the Huns along with half of the remaining territory of the western empire by way of a dowry. Naturally Valentinian refused and so the Huns and the Western Romans prepared for war.

In 451 a vast force of Huns and allied peoples, which the Romano-Gothic historian Jordanes describes as being an unbelievable half a million strong, began marching on Gaul. They drove up the Moselle Valley, bypassing heavily fortified Trier and sacking Metz. As the Huns spilled out on to the plain of Champagne, Aetius desperately organised a coalition of Romans, Goths, Franks and Burgundians in order to resist the invader who was an enemy feared equally by them all.

By mid-June Attila had laid siege to the large and prosperous city of Orleans whilst the defenders desperately looked to the south for the approach of Aetius’ coalition. When the Roman and Gothic army appeared, Attila decided to retreat and retraced his steps eastwards towards Troyes. Here his forces ran into a contingent of advancing Franks and following heavy fighting which the Huns had the worst of, they made a fortified camp from their circled wagons in an area known as the Catalaunian Plains.

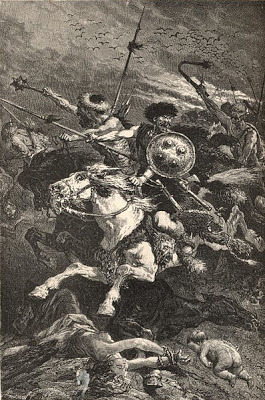

Battle of Catalaunian Plains

Battle of Catalaunian Plains Here Aetius caught up with the Huns and battle was joined. Both sides raced to claim an area of high ground in the centre of the battlefield, with the Visigothic cavalry reaching it first and driving off the Huns. The Hunnic cavalry then unleashed their storm of arrows against the advancing allies who somehow stood up to the battering and kept coming on. The battle was now a clash of infantry between the various allied contingents in the Hunnic force and those fighting under Roman colours. On Attila’s side were Goths, Rugi, Scirians, Gepids and those Franks who supported Attila’s preferred claimant to their disputed throne rather than Aetius’ man.

Battle raged until darkness fell and men could no longer identify each other in the gloom and ended with Aetius’ forces as masters of the field and the Huns driven back inside their circle of wagons. Somewhere in the confusion King Theodoric of the Visigoths was struck by a spear and as he fell from his horse was trampled under the hooves of friend and foe.

As dawn broke on the Catalaunian Plains Attila prepared to face the final onslaught of his enemies. He ordered a great pyre to be made from saddles and resolved to burn alive if his camp fell to the enemy. He was spared so dramatic an end however as the Visigoths came across the body of their fallen king in a heap of corpses and the threat of a succession crisis prompted them to return to Aquitaine. The Franks were similarly preoccupied and also retired and Attila was permitted to slip away to friendly territory. Aetius let him go, appreciating perhaps that the dreaded Hun was of more use to him alive than dead, given the foreboding he inspired amongst the other groups who threatened the west.

Attila however was not done yet and in the following year he once more led his forces onto Roman soil, this time invading Italy itself. The northern city of Aquileia was subjected to a typically brutal sack and Attila next contemplated the inviting target of Rome itself. Disease had broken out in his army however and supplies were short. Already laden with plunder, he decided to withdraw. This at any rate is a more plausible reason for his withdrawal than the intercession of Pope Leo I, who is credited with persuading the man the western church had dubbed the ‘Scourge of God’ to spare the city of Rome. Whatever the reason, the Romans had been given another reprieve.

Attila meets the Pope

Attila meets the PopeA year later came news of the biggest let off of all for Attila was dead. He had expired on his wedding night. Having just deflowered his latest teenage bride and sozzled with alcohol, the King of the Huns suffered a nosebleed and choked upon his own blood in his sleep. It has to be admitted that by the standards of the time this was a pretty good way to go.

The demise of its most formidable enemy was not enough to prevent the continuing collapse of the western empire. The foolish Valentinian III, jealous of Aetius’ talents and suspicious of his ambition, murdered the western empire’s most effective defender in 454. Unusually the emperor did his own dirty work and cut the unsuspecting Aetius down with his sword during an audience. Valentinian was then himself killed in reprisal by officers loyal to Aetius within a year of the deed. His passing marked the end of the Theodosian dynasty which had ruled in both east and west for over sixty years and left the western empire destabilised and vulnerable as enemies closed in from all sides.

As for the Huns, the death of Attila led to the rapid disintegration of his empire which it seemed had only been held together by the force of his personality. Within a year of his death a major battle took place on the River Nedao in modern Hungary in which an alliance under the King of the Gepids defeated the Huns under the command of Attila’s son Ellac and shattered Hunnic control over the various peoples settled along the Danube. Whilst bands of Huns would continue to serve as mercenaries in the wars of the Roman Empire, spreading terror wherever they went, their own days of empire were alas, or perhaps thankfully, at an end.

Priscus' account of the embassy to Attila

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/priscus1.asp

Jordanes' account of the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/451jordanes38.asp

I was lazy for this article and reused material from my own book The Battles are the Best Bits, but if you liked it please check out the book. http://www.amazon.com/The-Battles-Best-Bits-ebook/dp/B008GT05IY

You may also enjoy my Enemies at the Gate series of posts

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/enemies-at-gate-part-one-umayyad-sieges.html

Published on June 20, 2013 17:32

June 14, 2013

Saturn over the rooftops

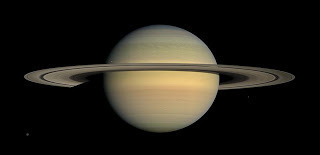

Once when we pointed out to my Mother-in-Law the presence of Mars in the northern sky she exclaimed. ‘Eee. Well I never knew Mars was up my road!’ I experienced a similar revelation the other week myself when I deployed my telescope to the top patio and aimed it just above the rooftop, which was helpfully hiding the bright moon. As I pointed the scope at the bright object that my handy mobile app' identified as the planet Saturn and twiddled the appropriate knobs to scan the heavens, all at once the planet came unmistakably into view.

I caught my breath. It was beautiful. I had not expected with my puny little 76mm telescope that I would have had such a fine view of Saturn but there it was, rings and all, shining brightly with its distinctive yellow hue. I could even make out one - no - two moons. To be able to look upon that impossibly distant world with my own eyes moved me more than I had known that it would. I still haven't tired of gazing at it as it shines brightly over my rooftop.

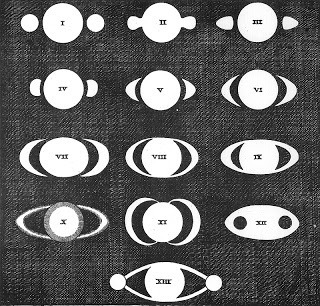

When Galileo turned his telescope towards Saturn in July 1610 he found himself greatly puzzled by its appearance. The limitations of his equipment meant that Galileo was not able to observe the rings with clarity but instead beheld what he described as a ‘planet triform’. Galileo supposed that Saturn was flanked by two smaller moons which never altered in their positions relative to the larger planet. Until such time as he could be confident of his findings, in a common practice amongst enlightenment thinkers at the time, Galileo circulated his theory in the form of an anagram. In the event that another astronomer came to the same conclusion and published their findings before him, Galileo could provide the solution to the anagram and reveal that he had been right all along! Two years later however, when he observed Saturn again, the great scholar was perturbed to find that the ‘moons’ had disappeared. Despite his puzzlement Galileo confidently predicted that the moons would return and so in due course they did. Indeed, as more curious observers turned their instruments towards the heavens a bewildering array of manifestations of the planet Saturn were described. What on earth were these strange phenomena?

Danish lens maker and astronomer Christiaan Huygens, from whose 1659 publication Systema Saturnium the above diagram is taken, was the first observer to finally be able to discern the truth of the mystery when he deduced that the planet Saturn was surrounded by a ring. Huygens was also the first to observe the moon Titan in orbit around Saturn. Huygens, like Galileo, at first released his findings in the form of an anagram whilst he continued his observations and firmed up his convictions regarding the planet. The solution to the anagram as he revealed in Systema Saturnium was Annulo cingitur, tenui, plano, nusquam cobaerente, ad eclipticam inclinator: It is encircled by a ring, thin, plane, nowhere attached, inclined to the ecliptic.

Huygens believed the ring to be a solid structure, although he was uncertain as to its composition; merely ascribing its existence to the ‘power and majesty of nature’.

I believe that I should digress here to meet the objection of those who will find it exceedingly strange and possibly unreasonable that I should assign to one of the celestial bodies a figure the like of which has up to this time not been found in any one of them, although, on the other hand, it has been believed as certain, and considered as established by natural law, that the spherical form is the only one adapted to them; and that I should place this solid and permanent ring (for such I consider it) about Saturn, without attaching it by any joints or ties, although imagining that it preserves a uniform distance on every side and revolves in company with Saturn at a very high rate of speed. These men should consider that I do not construct this hypothesis from pure invention and out of my own fancy, as the astronomers do their epicycles, which nowhere appear in the heavens, but that I perceive this ring very plainly with the eyes; with which, obviously, we discern the figures of all other things. And there is, after all, no reason why it should not be possible for some heavenly body to exist having this form, which, if not spherical, is at least round, and is quite as well adapted to the possession of circumcentral motion as the spherical form itself. For it certainly is less surprising that such a body should have assigned to it a shape of this kind than that it should have some absurd and quite unbeautiful shape. Furthermore, since, owing to the great similarity and relationship that exists between Saturn and our Earth, it seems possible to conclude quite conclusively that the former, like the latter, is situated in the middle of its own vortex, and that its centre has a natural tendency to reach toward all that is considered to have weight there, it must also result that the ring in question, pressing with all its parts and with equal force toward the centre, comes by this very fact to a permanent position in such a way that it is equally distant on all sides from that centre. Exactly so some people have imagined that, if it were possible to construct a continuous arch all the way around the Earth, it would sustain itself without any support. Therefore, let them not consider it absurd if a similar thing has happened of itself in the case of Saturn; let them rather regard with awe the power and majesty of Nature, which, by repeatedly bringing to light new specimens of its works, admonishes us that yet more remain.Christiaan Huygens Systema Saturnium 1659

Christiaan Huygens Next to turn his telescope towards Saturn was our old friend Gian Domenico Cassini, now overseeing the Paris observatory under the patronage of Louis XIV. Between 1671 and 1684 Cassini discovered four more moons of Saturn; Iapetus, Rhea, Tethys and Dione. He named these moons the Sidera Lodoicea or Louisean Stars in honour of his royal patron. He also discovered in 1675 that Huygens had been incorrect in his assertion that the ring was a single solid structure with his observation of a visible gap between the rings which still goes by the name of the Cassini Division. Cassini correctly deduced that the rings of Saturn were not a solid structure but rather were composed of millions of tiny satellites orbiting the planet.

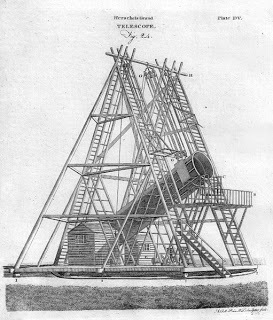

Christiaan Huygens Next to turn his telescope towards Saturn was our old friend Gian Domenico Cassini, now overseeing the Paris observatory under the patronage of Louis XIV. Between 1671 and 1684 Cassini discovered four more moons of Saturn; Iapetus, Rhea, Tethys and Dione. He named these moons the Sidera Lodoicea or Louisean Stars in honour of his royal patron. He also discovered in 1675 that Huygens had been incorrect in his assertion that the ring was a single solid structure with his observation of a visible gap between the rings which still goes by the name of the Cassini Division. Cassini correctly deduced that the rings of Saturn were not a solid structure but rather were composed of millions of tiny satellites orbiting the planet. In 1789, Hanoverian astronomer and composer William Herschel, a favourite of King George III best known for his discovery of Uranus, began observations with his famous Great Forty Foot Telescope. (Pictured above) On the very first night of using the giant instrument, Herschel discovered another moon of Saturn; Mimas. Within a month he had discovered a second; Enceladus. The forty footer was the largest telescope yet created. This great ‘penetrator of the heavens’ as Herschel described it, was a national sensation and challenged the Christian preconceptions of the day which still saw the universe as a cosy firmament which enclosed God’s creation, in which Earth remained of primary importance. Instead, Herschel, himself a firm believer in the possibility of extra-terrestrial life, was revealing a boundless universe filled with countless unknown and distant worlds. This new, bigger vision of the cosmos made many uncomfortable and Herschel’s scientific endeavours were criticised by more romantically inclined contemporaries such as Wordsworth and Blake who dismissed the giant telescope as a sideshow. King George III however thought that it was a marvellous device. ‘What what!’ And commissioned several smaller instruments from Herschel for his own use. With such enthusiastic royal support, a craze for studying the heavens was born in an Eighteenth Century equivalent of the ‘Brian Cox effect’. Of which I am myself a recent victim.

In 1789, Hanoverian astronomer and composer William Herschel, a favourite of King George III best known for his discovery of Uranus, began observations with his famous Great Forty Foot Telescope. (Pictured above) On the very first night of using the giant instrument, Herschel discovered another moon of Saturn; Mimas. Within a month he had discovered a second; Enceladus. The forty footer was the largest telescope yet created. This great ‘penetrator of the heavens’ as Herschel described it, was a national sensation and challenged the Christian preconceptions of the day which still saw the universe as a cosy firmament which enclosed God’s creation, in which Earth remained of primary importance. Instead, Herschel, himself a firm believer in the possibility of extra-terrestrial life, was revealing a boundless universe filled with countless unknown and distant worlds. This new, bigger vision of the cosmos made many uncomfortable and Herschel’s scientific endeavours were criticised by more romantically inclined contemporaries such as Wordsworth and Blake who dismissed the giant telescope as a sideshow. King George III however thought that it was a marvellous device. ‘What what!’ And commissioned several smaller instruments from Herschel for his own use. With such enthusiastic royal support, a craze for studying the heavens was born in an Eighteenth Century equivalent of the ‘Brian Cox effect’. Of which I am myself a recent victim.Huygens’ Systema Saturniumhttp://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Extras/Huygens_Saturn.html

Herschel’s Great Forty Footerhttp://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=kathleen-lundeen-on-herschels-forty-foot-telescope-1789

You may also enjoyhttp://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/by-jove-story-of-jupiter.html

Published on June 14, 2013 02:24

May 28, 2013

The First Roars – Early British and Irish Lions tours 1888-1910

It’s nearly time for the British and Irish Lions tour to begin and I am experiencing the usual surge of anticipation and optimism at the prospect. On the back of this year’s shirt is a logo declaring this to be the 125thanniversary of the first Lions tour.

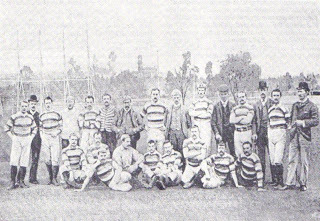

1888 British squad

1888 British squadThis first tour by a combined party comprising players from all four home nations to Australia and New Zealand in 1888 was a grand expedition, in which a squad of just 22 players would play in no less than 54 matches over a 21 week period. The tour was arranged by a triumvirate of English cricketing luminaries who had succeeded in turning a handsome profit from arranging cricketing tours to Australia and now sought to do the same with rugby union. Their proposal to offer players compensation for their loss of time in addition to covering their expenses, which were considerable with the tour lasting eight months including travel, caused outrage in the committee rooms of the home unions who denounced the venture as being tainted by professionalism. There was no dirtier word in sport in those days!

The players on this first tour were not known as Lions, neither did they travel with the blessing or endorsement of their home unions. Nevertheless the tour invoked the spirit which has continued down to this day. The tourists played 16 matches in Australia and 19 in New Zealand. In addition they took on the Aussies at their own game in 19 matches of ‘Victorian Rules football’ as the uniquely Australian variation of the game was then called.

Of the 35 rugby matches they won 27, although they were not always on form. Following a dismal performance to lose 4-0 against Auckland the British team were castigated by the tour manager for indulging in ‘too much whiskey and women!’ The tour was hit by tragedy when the team captain Bob Seddon drowned in a rowing accident whilst enjoying some leisure time on the Hunter River in New South Wales. The show nevertheless went on. Seddon’s replacement as captain was legendary all-rounder Andrew Stoddart who is better known for his cricketing exploits as an Ashes-winning captain but also captained the English rugby team in ten internationals. In addition to Seddon and Stoddart only two other members of the first British touring side would ever be capped by their home nations; Englishman Tom Kent and Welshman Willie Thomas.

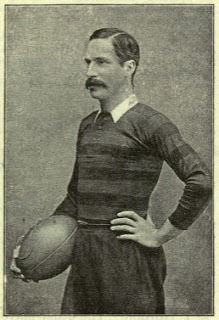

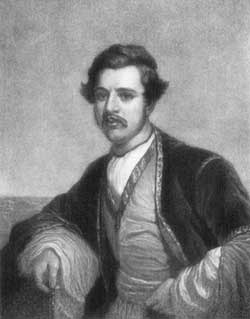

Andrew Stoddart

Andrew StoddartThe 1888 tour did not deliver the big payday that its organisers had hoped for, nevertheless the idea caught on. British touring sides continued to ply their trade in the Southern Hemisphere. A British tour to South Africa in 1891 was a remarkable triumph, in which the tourists won all three test matches against the Springboks as well as all 17 provincial matches played. Oh that we should see such times again! Another tour of South Africa in 1896 saw the first international victory for South Africa, winning a single test but losing the series 3-1. A winning tour of Australia followed in 1899 with a 3-1 series victory. The dominance was not set to last however and soon the colonials were fighting back. The British side lost the only test match in South Africa in 1903 and in 1904 on a tour of both New Zealand and Australia they whitewashed the Aussies 3-0 but were beaten by the All Blacks in a single test. In the three test match series against New Zealand four years later the British team could only manage a single draw and were twice beaten.

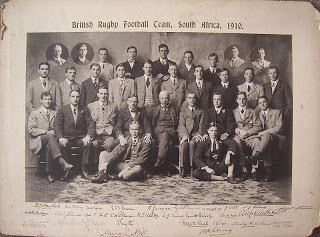

By 1910 the four home unions had at last all come around to the idea of a combined touring party from all four nations being a jolly spiffing one. The tour to South Africa in this year was therefore the first to set out with the formal blessing of all four unions and is seen as the first ‘true’ lions tour. The name ‘Lions’ was not coined until 1924 however, when journalists covering that year’s tour of South Africa noted the lion motif sported on the ties and blazers of the British team. The test series was a 2-1 loss. In the early days the British teams played in red, white and blue stripped jerseys and later in dark blue. The quartered crest with the emblems of the four nations was adopted in 1924 and the red jersey was first seen in 1950.

1910 British team

1910 British teamThe 14 year hiatus in British overseas touring activities following the 1910 tour heralds the shadow of the Great War across this story and as you might expect many of those who took part in these early tours were young and fit at the time that war broke out and naturally served in the conflict. Eleven of them made the ultimate sacrifice.

Alex Todd, who scored a try in the second test against South Africa in 1896 fell at Ypres. Charlie Adamson; the top points scorer of the 1899 tour with two test match tries, who was capable of playing in any of the back positions, died at Salonica just two months before the end of the war. Jimmy Hossack, a forward on the 1903 tour was killed at Kangata in East Africa.

Four players from the 1904 tour to Australia and New Zealand; Sidney Crowther, Blair Swannell, Ron Rogers and David Bedell-Sivright lost their lives in the Great War. Swannell (pictured below left) was a notoriously tough forward who had settled in Australia. He was capped once by that country and fell during the landing at Anzac cove on the first day of the Gallipoli campaign. Bedell-Sivright, the 1904 captain, was a Naval Surgeon who contracted septicaemia whilst serving in Gallipoli. Rogers also lost his life at Gallipoli whilst fellow English forward Crowther was killed whilst serving as a motorcycle dispatch rider in Flanders.

Johnnie Williams (right) was a Welsh winger with a signature swerve. He was the top try scorer on the 1908 tour to Australia and New Zealand. He fell at Mametz Wood.

Three of the 1910 Lions were killed in action. Scottish Scrum half Eric Milroy fell at Delville Wood serving with the Black Watch. Welsh forward Phil Waller, who played in all three tests, remained in South Africa and played for the Golden Lions before joining the South African Artillery. He was killed at Arras. Welsh fly half Noel Humphreys served as a captain in the tank corps and was awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry after remaining with his stranded tank and digging it out whilst under enemy fire; recovering the tank and rejoining the battle in spite of being wounded. Humphreys later died of his wounds in March 1918.

1910 full back Stanley Williams survived the war and was awarded the DSO. Scottish centre Charles Timms served as a medical officer and was awarded the Military Cross on four occasions. Irish forward William Tyrrell also served as a medical officer, was mentioned in dispatches on six occasions and was awarded the MC and DSO.

One other hero who is worthy of mention from the 1910 Lions squad is Welsh forward Harry Jarman, who played in all three tests. Jarman was killed in 1928 after he flung himself in front of a runaway coal truck which was careering towards a group of playing children.

Then as now, British Lions were a special breed of men. Enjoy the games.

http://www.lionsrugby.com/history/index.php

http://www.lionsrugby.com/history/index.phpYou may also enjoy: http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/rudolf-caracciola-original-meister.html

Published on May 28, 2013 03:34

May 22, 2013

Enemies at the Gate Part One – The reign of Michael III

Greetings Dear Reader. Let us resume the story of the Byzantine Empire’s efforts to resist all of those who sought to assail it throughout its long and illustrious history. I shall begin this post at the point at which the iconoclasm series left off. We find ourselves therefore in the reign of Emperor Michael III who ascended to the Byzantine throne in 842 as a two year old child. Power naturally rested with his widowed mother the Empress Theodora who, together with her ally and chief councillor the Logothete Theoctistus now held sway over the empire and presided over the triumphant restoration of the icons.

Theoctistus, like many a powerful Byzantine courtier was a eunuch, but this in no way debarred him from taking the lead of a military expedition. Since its capture by the Arabs the island of Crete had become a nest of pirates, whose activities included attacking Imperial shipping and raiding the Aegean islands and coastal settlements. In 843 Theoctistus set out at the head of an expeditionary force with the aim of retaking the island.

Arab fleet invades Crete

Arab fleet invades CreteThe expedition was initially successful and Theoctistus’ troops were able to virtually overrun the island. With victory in his grasp however, the Logothete lost his nerve when a rumour reached him of a plot to supplant him in the capital. Returning at once to Constantinople, Theoctistus left the expedition leaderless and in his absence the Arabs were able to fight back. Supported and reinforced by their co-religionists in Egypt the Arab defenders ultimately succeeded in annihilating the Byzantine expeditionary force. In the following year Theoctistus presided over another calamitous defeat at Mauropotamus in Cappadocia when his attempt to thwart an Abbasid invasion was crippled by mass desertions to the enemy. Following this defeat a period of truce was agreed between the Byzantine and Abbasid courts which allowed Theodora and Theoctistus to concentrate on the elimination of domestic enemies. The dualist sect of the Paulicians, whose numbers were on the increase in Cilicia, were subjected to a campaign of systematic persecution, causing many to flee to the lands of the Caliphate for protection. Those who remained faced a stark choice between conversion and death with most choosing the latter. The campaign against them was a short-sighted display of religious intolerance which drove the relatively harmless but numerous sect into the arms of the Arabs, depriving the empire of useful manpower.

In 853 came Theoctistus’ most notable triumph when he decided to strike against the port city of Damietta in the Nile Delta. It was a prime target; packed with ships and timber and the materials of war. Its destruction would severely hamstring Arab efforts to wage war against the empire at sea. Striking at the time of a major festival being held in Fustat, the Byzantine fleet commanded by another eunuch named Damianus fell upon the poorly defended port, disgorging five thousand troops to sack and burn the town in a two day orgy of destruction.

Theoctistus had redeemed his reputation but his continuing stranglehold on the affairs of the empire alongside Theodora was beginning to vex the young emperor Michael. By the time he had reached the age of fifteen Michael was giving vent to his frustration and found a sympathetic ear in the person of his uncle Bardas who was happy to arrange the arrest and cold-blooded murder of the Logothete and the confinement of Theodora to a nunnery. Michael was a weak-willed individual however and soon found that he had exchanged the dominance of his mother and her eunuch councillor for that of his uncle ,who would ultimately come to hold the rank of Caesar. The Patriarch Ignatius who opposed both Bardas’ increasing grip on affairs and his incestuous marriage to his own niece also soon found himself accused of conspiring with the emperor’s mother and was swiftly deposed and packed off to a monastery.

Michael III depicted as sole ruler on coin from British Museum collection (P Clayton) Under Bardas the empire remained on an aggressive footing. Bardas’ brother Petronas led a raid deep into Arab territory in 856, ostensibly against the Paulicians, reaching Amida on the Tigris and returning heavy with captives and plunder. Three years later another raid was launched across the Euphrates which the emperor himself accompanied and in the same year another amphibious attack was made on Damietta which once again devastated the port.

Michael III depicted as sole ruler on coin from British Museum collection (P Clayton) Under Bardas the empire remained on an aggressive footing. Bardas’ brother Petronas led a raid deep into Arab territory in 856, ostensibly against the Paulicians, reaching Amida on the Tigris and returning heavy with captives and plunder. Three years later another raid was launched across the Euphrates which the emperor himself accompanied and in the same year another amphibious attack was made on Damietta which once again devastated the port. In the summer of 860 whilst the emperor remained away from his capital in the east with Bardas, Petronas and most of his armed forces, a new threat to Constantinople itself appeared from an entirely unexpected direction. On the northern horizon there appeared a great swarm of sails and soon the terrorised citizens beheld the awful spectacle of a two hundred strong fleet of longships descending upon them. These were the Rus; adventurers of Scandinavian extraction who had set out to make a new home for themselves in the uncharted vastness of Russia. Here the hardy Vikings had both subjugated and been at least partially culturally assimilated by the indigenous Slavic population over the course of a generation or two. They had found plenty to trade in the form of furs, amber and slaves and had made use of the network of great rivers to explore southwards, reaching the Black Sea and establishing friendly commercial contacts with the peoples through whose lands they travelled. These particular raiders had been dispatched southwards by Rurik; the ruler of the settlement of Novgarod, to seize control of the commercially useful staging post of Kiev on the Dneiper. Having achieved this objective without difficulty, Rurik’s expeditionary force and their Slavic followers proceeded down the Dnieper into the Black Sea and thence to Constantinople. Swarming into the Bosphorus ‘like wasps’ as the Patriarch Photius described them, these invaders fell upon the vulnerable monasteries along the shore and on the islands in the Marmara. The imperial fleet was also absent and so the Rus burned and pillaged as they saw fit; destroying everything outside of the protective walls of the capital quite unopposed. The city itself remained invulnerable however and so once all of the easy pickings had been taken the Rus turned for home.

A later legend grew up around the raid, which is preserved in the Russian Primary Chronicle, in which the Patriarch Photius dipped the sacred relic of the robe of the Virgin Mary into the waters of the Golden Horn. All at once a storm blew up and scattered the ships. The Rus however would be back.

When the Emperor had set forth against the infidels and had arrived at the Black River, the eparch sent him word that the Rus were approaching Tsargrad, and the Emperor turned back. Upon arriving inside the strait, the Rus made a great massacre of the Christians, and attacked Tsargrad in two hundred boats. The Emperor succeeded with difficulty in entering the city. He straightway hastened with the Patriarch Photius to the Church of Our Lady of the Blachernae, where they prayed all night. They also sang hymns and carried the sacred vestment of the Virgin to dip it in the sea. The weather was still, and the sea was calm,but a storm of wind came up, and when great waves straightway rose, confusing the boats of the godless Rus, it threw them upon the shore and broke them up, so that few escaped such destruction and returned to their native land.

When the Emperor had set forth against the infidels and had arrived at the Black River, the eparch sent him word that the Rus were approaching Tsargrad, and the Emperor turned back. Upon arriving inside the strait, the Rus made a great massacre of the Christians, and attacked Tsargrad in two hundred boats. The Emperor succeeded with difficulty in entering the city. He straightway hastened with the Patriarch Photius to the Church of Our Lady of the Blachernae, where they prayed all night. They also sang hymns and carried the sacred vestment of the Virgin to dip it in the sea. The weather was still, and the sea was calm,but a storm of wind came up, and when great waves straightway rose, confusing the boats of the godless Rus, it threw them upon the shore and broke them up, so that few escaped such destruction and returned to their native land.Excerpt from Russian Primary Chronicle and detail from Kremlin fresco showing Photius dipping the robe of the Virgin in the sea.

With the capital once more safe and secure the emperor Michael could relax and enjoy himself; something in which he excelled. Leaving affairs of state in the hands of his uncle, the emperor spent his days drinking and attending the races with his closest companion Basil. Bardas meanwhile kept the empire on a war footing. In 863 the Caesar’s repeated stirring of the Muslim hornets’ nest elicited a response from Umar al Aqta; the Emir of Melitene and Islam’s most formidable warrior. Umar invaded the empire through Armenia and penetrated as far as the Black Sea coast, sacking the city of Amisus. Petronas was dispatched once more with a force of fifty thousand men and succeeded in pulling off a brilliant encirclement of Umar’s forces at Poson on the River Lalakaon. Cut down in the fighting, Umar was beheaded and his head was carried back to Constantinople on the tip of a lance to be presented to the emperor.

Defeat of Umar

Defeat of UmarFurther emboldened by this success, Bardas began planning a grand new expedition for the reconquest of Crete. Troops were gathered and the fleet was prepared. By the Spring of 866 all was in readiness and the army marched out of the city accompanied by the Emperor who would see the expedition off at its point of embarkation. Unknown to Bardas however, a plot against his life was already in motion. The emperor’s favoured companion Basil, whom the Caesar had dismissed as a harmless roustabout, harboured great ambitions; ambitions which would only be furthered by removing Bardas. Basil therefore had been whispering in Michael’s ear; whispering that his uncle wished to supplant him and make himself emperor in his stead. To these poisonous whisperings Michael gave credence all too readily and gave his tacit agreement to a conspiracy to assassinate Bardas. On the day of the embarkation a pavilion had been erected from which the emperor and his attendant courtiers would watch the expeditionary troops march past. At an agreed signal Basil and an accomplice drew their swords and set upon the Caesar Bardas; cutting him down at the emperor’s feet. With Bardas’ murder the grand expedition against Crete was forgotten and Michael III returned to Constantinople; there to raise up his uncle’s murderer, incredibly, as joint ruler alongside him. Michael, predictably enough, once more left affairs of state in the hands of Basil whilst he spent his days indulging in chariot racing and drinking himself insensible. It would prove to be a fatal decision for Basil’s ambition knew no bounds .Within a year Basil had tired of sharing the purple with his friend and benefactor and he struck once more; having Michael hacked to pieces in his own bed-chamber as he lay in a drunken stupor.

Assassination of Bardas Michael III ‘the Sot’ had been, by and large, a spectator to his own reign; sitting back with cup in hand whilst better men had seen the empire through the challenges that had faced it. Theoctistus and his uncles Bardas and Petronas had waged war against the Saracens whilst the highly capable Patriarch Photius had advanced the cause of Christianity amongst the Bulgars and Slavs to the west through an intense campaign of missionary activity and had perhaps even turned back the Rus with a miracle! The usurper Basil inherited an empire in good health, for which his predecessor was owed little and whose demise was largely unlamented. To his murdered friend Michael however, who had raised him up from a humble stable hand to the throne of empire, Basil owed everything.

Assassination of Bardas Michael III ‘the Sot’ had been, by and large, a spectator to his own reign; sitting back with cup in hand whilst better men had seen the empire through the challenges that had faced it. Theoctistus and his uncles Bardas and Petronas had waged war against the Saracens whilst the highly capable Patriarch Photius had advanced the cause of Christianity amongst the Bulgars and Slavs to the west through an intense campaign of missionary activity and had perhaps even turned back the Rus with a miracle! The usurper Basil inherited an empire in good health, for which his predecessor was owed little and whose demise was largely unlamented. To his murdered friend Michael however, who had raised him up from a humble stable hand to the throne of empire, Basil owed everything.The Damietta Raid

http://byzantinemilitary.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/War%20-%20Sack%20of%20Damietta%20Egypt

The Russian Primary Chronicle http://www.utoronto.ca/elul/English/218/PVL-selections.pdf To continue the story go to Enemies at the Gate Part Twohttp://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/enemies-at-gate-part-three-basil-i-and.html

Published on May 22, 2013 02:42

Enemies at the Gate Part Two – The reign of Michael III

Greetings Dear Reader. Let us resume the story of the Byzantine Empire’s efforts to resist all of those who sought to assail it throughout its long and illustrious history. Part One of this series dealt with the two great Arab sieges launched against Constantinople in 674 and 717, both of which were seen off decisively. The mighty Theodosian Walls had kept the attackers at bay on land whilst the terror weapon that was Greek Fire had reduced the Arab fleets to ashes.

Emperor Leo III who had overseen the second defence of Constantinople against the forces of the Umayyad Caliph is remembered mostly however not as a saviour of the city but as the man who instigated the iconoclastic movement. The story of iconoclasm has been told in a separate set of posts already so rather than repeat the travails of those times again I shall begin this post at the point at which the iconoclasm series left off. We find ourselves therefore in the reign of Emperor Michael III who ascended to the Byzantine throne in 842 as a two year old child. Power naturally rested with his widowed mother the Empress Theodora who, together with her ally and chief councillor the Logothete Theoctistus now held sway over the empire and presided over the triumphant restoration of the icons.

Theoctistus, like many a powerful Byzantine courtier was a eunuch, but this in no way debarred him from taking the lead of a military expedition. Since its capture by the Arabs the island of Crete had become a nest of pirates, whose activities included attacking Imperial shipping and raiding the Aegean islands and coastal settlements. In 843 Theoctistus set out at the head of an expeditionary force with the aim of retaking the island.

Arab fleet invades Crete

Arab fleet invades CreteThe expedition was initially successful and Theoctistus’ troops were able to virtually overrun the island. With victory in his grasp however, the Logothete lost his nerve when a rumour reached him of a plot to supplant him in the capital. Returning at once to Constantinople, Theoctistus left the expedition leaderless and in his absence the Arabs were able to fight back. Supported and reinforced by their co-religionists in Egypt the Arab defenders ultimately succeeded in annihilating the Byzantine expeditionary force. In the following year Theoctistus presided over another calamitous defeat at Mauropotamus in Cappadocia when his attempt to thwart an Abbasid invasion was crippled by mass desertions to the enemy. Following this defeat a period of truce was agreed between the Byzantine and Abbasid courts which allowed Theodora and Theoctistus to concentrate on the elimination of domestic enemies. The dualist sect of the Paulicians, whose numbers were on the increase in Cilicia, were subjected to a campaign of systematic persecution, causing many to flee to the lands of the Caliphate for protection. Those who remained faced a stark choice between conversion and death with most choosing the latter. The campaign against them was a short-sighted display of religious intolerance which drove the relatively harmless but numerous sect into the arms of the Arabs, depriving the empire of useful manpower.

In 853 came Theoctistus’ most notable triumph when he decided to strike against the port city of Damietta in the Nile Delta. It was a prime target; packed with ships and timber and the materials of war. Its destruction would severely hamstring Arab efforts to wage war against the empire at sea. Striking at the time of a major festival being held in Fustat, the Byzantine fleet commanded by another eunuch named Damianus fell upon the poorly defended port, disgorging five thousand troops to sack and burn the town in a two day orgy of destruction.

Theoctistus had redeemed his reputation but his continuing stranglehold on the affairs of the empire alongside Theodora was beginning to vex the young emperor Michael. By the time he had reached the age of fifteen Michael was giving vent to his frustration and found a sympathetic ear in the person of his uncle Bardas who was happy to arrange the arrest and cold-blooded murder of the Logothete and the confinement of Theodora to a nunnery. Michael was a weak-willed individual however and soon found that he had exchanged the dominance of his mother and her eunuch councillor for that of his uncle ,who would ultimately come to hold the rank of Caesar. The Patriarch Ignatius who opposed both Bardas’ increasing grip on affairs and his incestuous marriage to his own niece also soon found himself accused of conspiring with the emperor’s mother and was swiftly deposed and packed off to a monastery.

Michael III depicted as sole ruler on coin from British Museum collection (P Clayton) Under Bardas the empire remained on an aggressive footing. Bardas’ brother Petronas led a raid deep into Arab territory in 856, ostensibly against the Paulicians, reaching Amida on the Tigris and returning heavy with captives and plunder. Three years later another raid was launched across the Euphrates which the emperor himself accompanied and in the same year another amphibious attack was made on Damietta which once again devastated the port.

Michael III depicted as sole ruler on coin from British Museum collection (P Clayton) Under Bardas the empire remained on an aggressive footing. Bardas’ brother Petronas led a raid deep into Arab territory in 856, ostensibly against the Paulicians, reaching Amida on the Tigris and returning heavy with captives and plunder. Three years later another raid was launched across the Euphrates which the emperor himself accompanied and in the same year another amphibious attack was made on Damietta which once again devastated the port. In the summer of 860 whilst the emperor remained away from his capital in the east with Bardas, Petronas and most of his armed forces, a new threat to Constantinople itself appeared from an entirely unexpected direction. On the northern horizon there appeared a great swarm of sails and soon the terrorised citizens beheld the awful spectacle of a two hundred strong fleet of longships descending upon them. These were the Rus; adventurers of Scandinavian extraction who had set out to make a new home for themselves in the uncharted vastness of Russia. Here the hardy Vikings had both subjugated and been at least partially culturally assimilated by the indigenous Slavic population over the course of a generation or two. They had found plenty to trade in the form of furs, amber and slaves and had made use of the network of great rivers to explore southwards, reaching the Black Sea and establishing friendly commercial contacts with the peoples through whose lands they travelled. These particular raiders had been dispatched southwards by Rurik; the ruler of the settlement of Novgarod, to seize control of the commercially useful staging post of Kiev on the Dneiper. Having achieved this objective without difficulty, Rurik’s expeditionary force and their Slavic followers proceeded down the Dnieper into the Black Sea and thence to Constantinople. Swarming into the Bosphorus ‘like wasps’ as the Patriarch Photius described them, these invaders fell upon the vulnerable monasteries along the shore and on the islands in the Marmara. The imperial fleet was also absent and so the Rus burned and pillaged as they saw fit; destroying everything outside of the protective walls of the capital quite unopposed. The city itself remained invulnerable however and so once all of the easy pickings had been taken the Rus turned for home.

A later legend grew up around the raid, which is preserved in the Russian Primary Chronicle, in which the Patriarch Photius dipped the sacred relic of the robe of the Virgin Mary into the waters of the Golden Horn. All at once a storm blew up and scattered the ships. The Rus however would be back.

When the Emperor had set forth against the infidels and had arrived at the Black River, the eparch sent him word that the Rus were approaching Tsargrad, and the Emperor turned back. Upon arriving inside the strait, the Rus made a great massacre of the Christians, and attacked Tsargrad in two hundred boats. The Emperor succeeded with difficulty in entering the city. He straightway hastened with the Patriarch Photius to the Church of Our Lady of the Blachernae, where they prayed all night. They also sang hymns and carried the sacred vestment of the Virgin to dip it in the sea. The weather was still, and the sea was calm,but a storm of wind came up, and when great waves straightway rose, confusing the boats of the godless Rus, it threw them upon the shore and broke them up, so that few escaped such destruction and returned to their native land.

When the Emperor had set forth against the infidels and had arrived at the Black River, the eparch sent him word that the Rus were approaching Tsargrad, and the Emperor turned back. Upon arriving inside the strait, the Rus made a great massacre of the Christians, and attacked Tsargrad in two hundred boats. The Emperor succeeded with difficulty in entering the city. He straightway hastened with the Patriarch Photius to the Church of Our Lady of the Blachernae, where they prayed all night. They also sang hymns and carried the sacred vestment of the Virgin to dip it in the sea. The weather was still, and the sea was calm,but a storm of wind came up, and when great waves straightway rose, confusing the boats of the godless Rus, it threw them upon the shore and broke them up, so that few escaped such destruction and returned to their native land.Excerpt from Russian Primary Chronicle and detail from Kremlin fresco showing Photius dipping the robe of the Virgin in the sea.

With the capital once more safe and secure the emperor Michael could relax and enjoy himself; something in which he excelled. Leaving affairs of state in the hands of his uncle, the emperor spent his days drinking and attending the races with his closest companion Basil. Bardas meanwhile kept the empire on a war footing. In 863 the Caesar’s repeated stirring of the Muslim hornets’ nest elicited a response from Umar al Aqta; the Emir of Melitene and Islam’s most formidable warrior. Umar invaded the empire through Armenia and penetrated as far as the Black Sea coast, sacking the city of Amisus. Petronas was dispatched once more with a force of fifty thousand men and succeeded in pulling off a brilliant encirclement of Umar’s forces at Poson on the River Lalakaon. Cut down in the fighting, Umar was beheaded and his head was carried back to Constantinople on the tip of a lance to be presented to the emperor.

Defeat of Umar

Defeat of UmarFurther emboldened by this success, Bardas began planning a grand new expedition for the reconquest of Crete. Troops were gathered and the fleet was prepared. By the Spring of 866 all was in readiness and the army marched out of the city accompanied by the Emperor who would see the expedition off at its point of embarkation. Unknown to Bardas however, a plot against his life was already in motion. The emperor’s favoured companion Basil, whom the Caesar had dismissed as a harmless roustabout, harboured great ambitions; ambitions which would only be furthered by removing Bardas. Basil therefore had been whispering in Michael’s ear; whispering that his uncle wished to supplant him and make himself emperor in his stead. To these poisonous whisperings Michael gave credence all too readily and gave his tacit agreement to a conspiracy to assassinate Bardas. On the day of the embarkation a pavilion had been erected from which the emperor and his attendant courtiers would watch the expeditionary troops march past. At an agreed signal Basil and an accomplice drew their swords and set upon the Caesar Bardas; cutting him down at the emperor’s feet. With Bardas’ murder the grand expedition against Crete was forgotten and Michael III returned to Constantinople; there to raise up his uncle’s murderer, incredibly, as joint ruler alongside him. Michael, predictably enough, once more left affairs of state in the hands of Basil whilst he spent his days indulging in chariot racing and drinking himself insensible. It would prove to be a fatal decision for Basil’s ambition knew no bounds .Within a year Basil had tired of sharing the purple with his friend and benefactor and he struck once more; having Michael hacked to pieces in his own bed-chamber as he lay in a drunken stupor.

Assassination of Bardas Michael III ‘the Sot’ had been, by and large, a spectator to his own reign; sitting back with cup in hand whilst better men had seen the empire through the challenges that had faced it. Theoctistus and his uncles Bardas and Petronas had waged war against the Saracens whilst the highly capable Patriarch Photius had advanced the cause of Christianity amongst the Bulgars and Slavs to the west through an intense campaign of missionary activity and had perhaps even turned back the Rus with a miracle! The usurper Basil inherited an empire in good health, for which his predecessor was owed little and whose demise was largely unlamented. To his murdered friend Michael however, who had raised him up from a humble stable hand to the throne of empire, Basil owed everything.

Assassination of Bardas Michael III ‘the Sot’ had been, by and large, a spectator to his own reign; sitting back with cup in hand whilst better men had seen the empire through the challenges that had faced it. Theoctistus and his uncles Bardas and Petronas had waged war against the Saracens whilst the highly capable Patriarch Photius had advanced the cause of Christianity amongst the Bulgars and Slavs to the west through an intense campaign of missionary activity and had perhaps even turned back the Rus with a miracle! The usurper Basil inherited an empire in good health, for which his predecessor was owed little and whose demise was largely unlamented. To his murdered friend Michael however, who had raised him up from a humble stable hand to the throne of empire, Basil owed everything.The Damietta Raid

http://byzantinemilitary.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/War%20-%20Sack%20of%20Damietta%20Egypt

The Russian Primary Chronicle http://www.utoronto.ca/elul/English/218/PVL-selections.pdf You may also like: Iconoclasm - A Byzantine Tragedy Part Onehttp://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/01/iconoclasm-byzantine-tragedy-part-one.html

Published on May 22, 2013 02:42

April 22, 2013

Last of the giants – Yamato and Musashi

Watching the US Secretary of State arriving in Japan last week to discuss the increasingly troubling military posturing of North Korea, I was pondering the curious turn of history and thinking about a time when the rising power of Imperial Japan viewed the military might of the USA with equal suspicion and jealousy as the regime in Pyongyang now does.

Watching the US Secretary of State arriving in Japan last week to discuss the increasingly troubling military posturing of North Korea, I was pondering the curious turn of history and thinking about a time when the rising power of Imperial Japan viewed the military might of the USA with equal suspicion and jealousy as the regime in Pyongyang now does.

In an age when the capital battleship rather than the intercontinental ballistic missile was the ultimate expression of military power, Japan set out to achieve not only parity but ultimately superiority over the US Navy in their quest to dominate the Pacific.

Under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty drawn up in 1922 in order to curtail the naval arms race which had once more broken out in the aftermath of the First World War, the five signatories; Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the USA, had agreed to impose maximum limits on the displacement and armament of battleships, cruisers and aircraft carriers and the overall size of their fleets. In adhering to the treaty the signatories were obliged to scrap some existing warships and curtail the construction of others or convert partially constructed battleships and cruisers into aircraft carriers.

US warships being scrapped under the terms of the Washington Treaty

US warships being scrapped under the terms of the Washington Treaty

By the mid 1930’s Japanese naval strategists had become convinced that their treaty obligations consigned them to certain defeat should they find themselves in a war with the United States and believed that the treaty must be abandoned. One man who argued against this school of thought was the future mastermind of the Pearl Harbour attack Admiral Yamamoto, who believed that the industrial might of America was such that Japan could never hope to out-build her naval rival and that Japan should not antagonise America by breaking the treaty but rather should stay within its provisions and look to even the odds with the US through strategy by landing a knock-out blow when the time came…

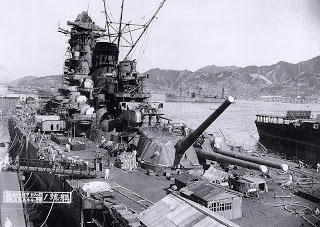

Yamamoto was outvoted and by 1936 an increasingly belligerent Japan had failed to turn up at the London conference which had aimed to extend the provisions of the Washington Treaty. Instead Japan now launched an ambitious building programme in which it intended to construct the largest battleships ever seen, armed with the largest guns yet created. The Yamato class was born.

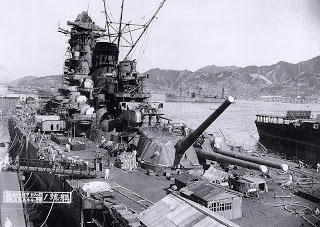

According to the terms of the Washington Treaty the main armament of a capital battleship could not exceed 16 inches in diameter. Japan intended the construction of six battleships armed with a main battery of nine 18 inch guns. These were to be succeeded in turn by a further four so-called Super Yamato class ships which would carry 20 inch guns. It was envisioned that these ten leviathans would all be commissioned by 1946, by which time the US, having stuck to the rules of the treaty and constructed nothing larger than a 16 incher, would find itself hopelessly outgunned in any encounter with the Imperial Japanese Navy. Yamato under construction Such grand plans amongst the naval strategists however made little allowance for the stark reality that was soon to intrude upon the Japanese warship programme. The war which broke out in 1941 with Yamamoto’s brilliant first strike against the US Pacific fleet, came five years too early for the Japanese planners, with not ten but only two of the planned battleships having been launched. Neither the Yamato, which was commissioned nine days after the outbreak of war nor her sister ship Musashi, commissioned on 5th August 1942, were ready to take the fight to the US navy. The Japanese had made unfeasibly long term plans in a world that was changing fast. The aircraft carriers which had been fortuitously absent when the attack on Pearl Harbour came from out of a clear blue sky, would turn out to be the crucial weapon in a conflict in which air power - not giant battleships - would provide the decisive edge.

Yamato under construction Such grand plans amongst the naval strategists however made little allowance for the stark reality that was soon to intrude upon the Japanese warship programme. The war which broke out in 1941 with Yamamoto’s brilliant first strike against the US Pacific fleet, came five years too early for the Japanese planners, with not ten but only two of the planned battleships having been launched. Neither the Yamato, which was commissioned nine days after the outbreak of war nor her sister ship Musashi, commissioned on 5th August 1942, were ready to take the fight to the US navy. The Japanese had made unfeasibly long term plans in a world that was changing fast. The aircraft carriers which had been fortuitously absent when the attack on Pearl Harbour came from out of a clear blue sky, would turn out to be the crucial weapon in a conflict in which air power - not giant battleships - would provide the decisive edge.

This was a reality reflected in the fate of the third of the Yamato class battleships, Shinano, which following the disastrous defeat at Midway, found itself converted into a much needed aircraft carrier. A fourth Yamato class was abandoned in mid construction and the none of the vaunted Super Yamatos ever made it off of the drawing board.

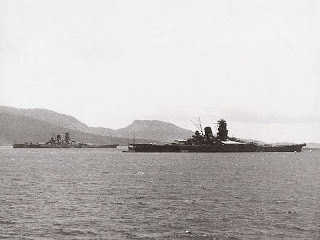

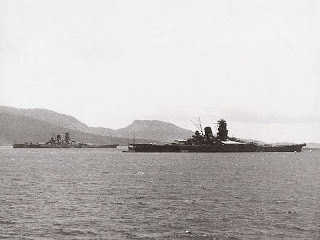

Battleship Yamato in 1941

Battleship Yamato in 1941

Yamato and Musashi then, were destined to be the largest and most heavily armed battleships ever constructed; the magnificent culmination of an era that was already fading. They were the last of the giants; born too late into a world at war that had already moved on to a new way of fighting in which great sea battles would be decided by swarms of carrier borne aircraft over even greater ranges than their colossal 18 inch guns could shoot. Floating follies though they may have been, what magnificent ships they were.

A Yamato class battleship was 862 feet in length with a displacement of 65,000 tons. It had a top speed of 27 knots and a range of over 7000 nautical miles. It carried a crew of 2,400 men. The main battery comprised nine 18 inch guns housed in three turrets, each of which weighed more than a typical destroyer of the period. The ships bristled with an array of six 6 inch secondary guns, a further twenty four 5 inch anti-aircraft guns and by the end of the war they had been fitted with one hundred and fifty machine guns. They also carried seven aircraft which could be launched from their two catapults.

The main guns could fire a shell weighing a little under 3000 pounds a distance of twenty five miles. Yamato and Musashi were also equipped with anti-aircraft shells for their big guns known as beehives. These burst in the air releasing a deadly cloud of steel splinters. Musashi's forward battery of 18 inch guns Yamato and Musashi were constructed in closely guarded secrecy at Kure and Nagasaki respectively. The ships were roofed over and screened from prying eyes and the main guns were referred to as ‘sixteen inch specials’ to mislead the intelligence services of rival nations. The true size of the guns was not known by the allies until the end of the war.

Musashi's forward battery of 18 inch guns Yamato and Musashi were constructed in closely guarded secrecy at Kure and Nagasaki respectively. The ships were roofed over and screened from prying eyes and the main guns were referred to as ‘sixteen inch specials’ to mislead the intelligence services of rival nations. The true size of the guns was not known by the allies until the end of the war.

These colossal weapons would have a long wait however to be fired in anger. Yamato put to sea in time to join in the Midway campaign but remained beyond the fringes of the battle whilst the Japanese carrier fleet met with disaster.

As the Japanese counter-attacking forces converged on Guadalcanal, Yamato languished at Truk Atol in the Caroline Islands, with neither the ammunition or the fuel being available for her to play a part in the coming struggle.

Here Musashi joined her in February 1943. Neither ship however would see combat as the tide of the war continued to flow inexorably against Japan. Spending long periods confined to port either in Truk or back in Japan, the ships undertook the occasional transportation role but otherwise were deemed either too precious to be risked or simply too fuel thirsty to embark on long operations. In spite of these mundane duties, both ships nevertheless fell prey to the attacks of US submarines. Yamato and Musashi in Truk Atol 1943 On Christmas Day 1943 as she was steaming towards Truk, Yamato was sighted by the submarine USS Skate which successfully torpedoed her. The impact on her aft starboard quarter caused 3000 tons of water to flood the hull but the Yamato, which was designed to be virtually unsinkable, was able to reach port and effect repairs before returning to Japan. Three months later, whilst en route from Palau to Kure, Musashi was torpedoed by the submarine USS Tunny. The impact tore a nineteen foot hole in the bow and Musashi limped back to her home port for extensive repairs and upgrades.

Yamato and Musashi in Truk Atol 1943 On Christmas Day 1943 as she was steaming towards Truk, Yamato was sighted by the submarine USS Skate which successfully torpedoed her. The impact on her aft starboard quarter caused 3000 tons of water to flood the hull but the Yamato, which was designed to be virtually unsinkable, was able to reach port and effect repairs before returning to Japan. Three months later, whilst en route from Palau to Kure, Musashi was torpedoed by the submarine USS Tunny. The impact tore a nineteen foot hole in the bow and Musashi limped back to her home port for extensive repairs and upgrades.

Both ships were back in action in time to join in the ill-fated attempt to thwart the US landings on Saipan which led to the disastrous losses of aircraft and carriers in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, but once again with matters decided by airpower at long range, the Japanese battleships did not fire a shot in anger. The time had come however for the decisive showdown which the Japanese command had always hoped would allow them to bring the superior firepower of Yamato and Musashi into play. As US forces closed in on the Philippines, the full might of the Imperial Japanese Navy was being prepared to be thrown against the invaders.

Yamato and Musashi joined Admiral Kurita’s Centre Force for Operation Sho Go. Their task was to force a passage through the San Bernardino Strait and fall upon the US invasion fleet in Leyte Gulf. A second attacking force would approach from the south whilst the surviving aircraft carriers would approach from the north. With almost all of their fighters lost however, the carriers posed no threat to the American forces but rather served as a diversion intended to draw Admiral Halsey’s powerful Third Fleet away from the vulnerable invasion forces, leaving them easy prey for Kurita’s mighty predators.

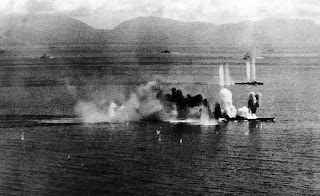

Yamato bomb impact during Battle of Sibuyan Sea As they steamed through the Sibuyan Sea on 24th October 1944, Centre Force was spotted by a scouting plane from the carrier USS Intrepid. As the American carriers scrambled their dive bombers and torpedo bombers in the direction of Centre Force, the Japanese ships soon came under attack by wave after wave of aircraft. Yamato took a bomb through the foredeck which ruptured the hull allowing the sea to flood in, although once again the toughness of her design allowed her to remain afloat. The Yamato class battleships were designed with over 1100 watertight compartments in order to minimise flooding resulting from bomb and torpedo impacts. Yamato steamed on. Musashi however was less fortunate.

Yamato bomb impact during Battle of Sibuyan Sea As they steamed through the Sibuyan Sea on 24th October 1944, Centre Force was spotted by a scouting plane from the carrier USS Intrepid. As the American carriers scrambled their dive bombers and torpedo bombers in the direction of Centre Force, the Japanese ships soon came under attack by wave after wave of aircraft. Yamato took a bomb through the foredeck which ruptured the hull allowing the sea to flood in, although once again the toughness of her design allowed her to remain afloat. The Yamato class battleships were designed with over 1100 watertight compartments in order to minimise flooding resulting from bomb and torpedo impacts. Yamato steamed on. Musashi however was less fortunate.

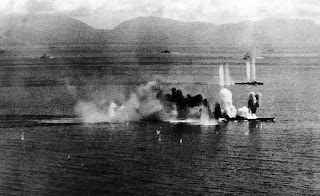

Despite adopting the novel defensive tactic of firing her 18 inch guns directly into the water to create huge waterspouts with the intention of knocking the low-flying torpedo bombers out of the sky, Musashi was eventually hit by 20 torpedoes and 17 bombs. The carnage aboard the ship was unimaginable. The greater the damage grew, the more Musashi slowed and listed and she was gradually left behind by the other ships of Centre Force as they turned about and headed away from the conflict zone. Finally the order to abandon ship was given before the crippled, blazing hulk of Musashi slipped beneath the waves, taking 1,023 of her complement with her to the bottom.

The sinking of Musashi

The sinking of Musashi

Halsey now assumed that Centre Force had been driven off and set out with his powerful fleet of carriers and battleships to hunt down and destroy the carriers of the Northern Force, not realising that these were paper tigers and that the Centre Force remained the principle threat. Kurita meanwhile swung his remaining ships around and under cover of darkness successfully negotiated the San Bernardino Strait.

On the following day the escort carriers and destroyers of the US flotilla known as Taffy 3; cruising off the island of Samar, whose role was to support the landings rather than engage in combat with the cream of the Japanese navy, were horrified to find the giant battleships of Centre Force steaming towards them.