Simon B. Jones's Blog: Slings and arrows, page 5

November 4, 2013

The first bones - early dinosaur discoveries

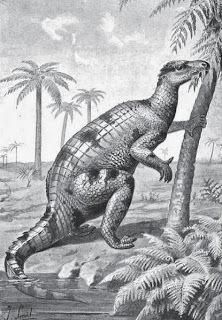

Iguanodon

IguanodonI got wondering the other day, as I do, who the first people were to come across the remains of dinosaurs. What did they make of them? Who was the first to realise that they had unearthed a long extinct creature from the distant past? My initial google search soon had me reading deeper into the story and as often happens I have ended up writing another blog post on a random subject that I wasn't planning to cover. Perhaps that is the best way to do it? So here we go. Ironically enough, our story begins with a man of the cloth.In 1676 the Reverend Robert Plot, who was also professor of Chemistry at Oxford University, published his work Natural History of Oxfordshire. Within it he discussed an unusual discovery that he had once come upon in a local quarry. Clearly identifiable as the top part of a femur, the fossilised bone fragment was far too large to have come from any creature native to Britain that Plot was aware of. Falling back on his history, Plot opined that perhaps the specimen was the remains of one of the elephants which Tacitus tells us were brought over to overawe the natives during Claudius’ invasion of 51 AD. It was such a good piece of deduction that it deserved to be right but Plot would have been astounded to learn that what he had actually described was the first recorded discovery of dinosaur remains.He would have scoffed at the idea of a seven metre long, one and a half ton giant lizard roaming around the Oxfordshire countryside. Indeed, having dismissed his reasonably sensible Roman elephant idea as fanciful, Plot had eventually decided that his bone must have belonged to a British Goliath. Giants after all were attested in the Bible whereas enormous lizards patently were not.

Robert Plot 1640-1696 In an age before the concept of evolution, the idea that the earth and all the creatures upon it had not remained precisely as God had made them, unchanged since the day of creation, was considered risible even by some of the most learned of men. As the enlightenment gathered pace however, it became harder for some to deny the evidence of their own eyes. James Hutton was such a man. This well-travelled geologist came to the conclusion that the very rocks of the earth were part of an ever changing ‘great geological cycle’ in which the twin forces of erosion and volcanic activity shaped and renewed the landscape. Hutton was convinced that such processes had taken place over long millennia and that the evidence in the rocks belied the prevailing biblical view of an earth that was just six thousand years old. In an even greater leap of logical deduction recorded in his work of 1794 Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge Hutton wrote:If an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be the most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.He was thus a man well ahead of his time. The work was never published and the proposal of the mechanism of evolution by natural selection would not appear in print until Charles Darwin’s 1859 Origin of Species.

Robert Plot 1640-1696 In an age before the concept of evolution, the idea that the earth and all the creatures upon it had not remained precisely as God had made them, unchanged since the day of creation, was considered risible even by some of the most learned of men. As the enlightenment gathered pace however, it became harder for some to deny the evidence of their own eyes. James Hutton was such a man. This well-travelled geologist came to the conclusion that the very rocks of the earth were part of an ever changing ‘great geological cycle’ in which the twin forces of erosion and volcanic activity shaped and renewed the landscape. Hutton was convinced that such processes had taken place over long millennia and that the evidence in the rocks belied the prevailing biblical view of an earth that was just six thousand years old. In an even greater leap of logical deduction recorded in his work of 1794 Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge Hutton wrote:If an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be the most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.He was thus a man well ahead of his time. The work was never published and the proposal of the mechanism of evolution by natural selection would not appear in print until Charles Darwin’s 1859 Origin of Species. James Hutton 1726-1797 Despite Hutton’s insight into these essential truths, the study of geology continued within the constraints of a biblical framework. William Buckland, another Oxford man who combined the seemingly contradictory duties of a clergyman with the pursuit of scientific enquiry, set out to reconcile the two. In his treatise of 1820 Vindiciae Geologiae Buckland was obliged, in order to secure the academic future of the discipline, to explain the stratification of sedimentary rock formations and the presence of fossilised animal remains within them as evidence of the great flood of Noah. The presence of creatures not native to Britain was put down to their bodies having been swept here from far off lands by the flood waters.The evidence however told a different story and Buckland was later convinced by the quantity of remains that he had found that these creatures must have lived here all along. By comparison of similar features of the British landscape with those he had seen during a visit to Switzerland, Buckland was persuaded that the land had been gradually shaped and that layers of rock had been laid down by the action of glaciers over thousands of years, rather than by a single catastrophic event. Buckland’s arguments met with much hostility but he had made one electrifying discovery over the course of his investigations into the remains of long dead creatures. In 1815 at Stonesfield Quarry in Oxfordshire, teeth and bones of a previously completely unknown beast had been uncovered. After a decade of painstaking reconstruction Buckland announced that he had found the remains of a giant carnivorous lizard. He named it Megalosaurus. Although the name dinosaur had not yet been coined, the first example of their kind had been found.

James Hutton 1726-1797 Despite Hutton’s insight into these essential truths, the study of geology continued within the constraints of a biblical framework. William Buckland, another Oxford man who combined the seemingly contradictory duties of a clergyman with the pursuit of scientific enquiry, set out to reconcile the two. In his treatise of 1820 Vindiciae Geologiae Buckland was obliged, in order to secure the academic future of the discipline, to explain the stratification of sedimentary rock formations and the presence of fossilised animal remains within them as evidence of the great flood of Noah. The presence of creatures not native to Britain was put down to their bodies having been swept here from far off lands by the flood waters.The evidence however told a different story and Buckland was later convinced by the quantity of remains that he had found that these creatures must have lived here all along. By comparison of similar features of the British landscape with those he had seen during a visit to Switzerland, Buckland was persuaded that the land had been gradually shaped and that layers of rock had been laid down by the action of glaciers over thousands of years, rather than by a single catastrophic event. Buckland’s arguments met with much hostility but he had made one electrifying discovery over the course of his investigations into the remains of long dead creatures. In 1815 at Stonesfield Quarry in Oxfordshire, teeth and bones of a previously completely unknown beast had been uncovered. After a decade of painstaking reconstruction Buckland announced that he had found the remains of a giant carnivorous lizard. He named it Megalosaurus. Although the name dinosaur had not yet been coined, the first example of their kind had been found.

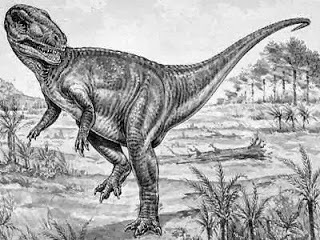

Megalosaurus Bucklandii

Megalosaurus BucklandiiIn 1922 a quarry in Tilgate Forest Sussex, not a stone’s throw from where I grew up, began to yield up fragments of another strange beast. Gideon Mantell, a doctor by profession and keen amateur fossil digger by inclination had already turned up a variety of extinct marine creatures in the Sussex chalk when his long suffering wife Mary Ann one day brought him a large fossilised tooth that she had come across during a walk. Mantell was convinced that this must belong to an entirely new type of creature; a giant herbivorous reptile. Comparison with the teeth of the modern iguana convinced him that the creature must have resembled a larger version of the lizard, perhaps as large as one hundred feet long.

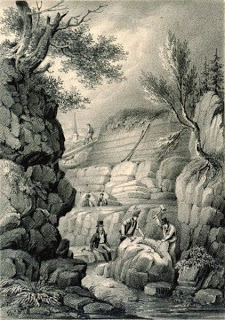

Mantell's dig in Tilgate Forest

Mantell's dig in Tilgate ForestFor the next decade Mantell laboured to turn up more fragments of the beast and eventually succeeded in making the case for his discovery in the face of opposition from the doyen of the zoological academic establishment and later founder of the Natural History Museum Richard Owen. The debate between the two turned bitter as Owen, the anatomical expert, argued that the Iguanodon, as it had come to be known, could not have been so large and that it had walked upon all fours like modern large mammals. Mantell conceded defeat on the size of the creature, having initially based his estimate on an up-scaled iguana and come up with Godzilla. He later proved however that the iguanodon’s forelimbs were shorter than its hind limbs and re-envisioned the creature as standing upright. In reality it probably spent most of its time on all fours but at the time it was Mantell’s interpretation, as depicted in the Victorian illustration at the top of this post, that prevailed. The Sedgwick Museum’s example specimen pictured below was mounted in a bipedal posture in accordance with this view.

Iguanodon - Sedgwick Museum Cambridge

Iguanodon - Sedgwick Museum CambridgeMantell is something of a tragic figure. Mary Ann finally left him after he reduced his family to penury, having abandoned his successful practice in Lewes and moved to Brighton where the family home was turned into a museum with the family forced into a single room. One can hardly blame the poor woman for taking the very unusual step of divorcing her husband in 1839. Mantell was later crippled in a carriage accident and in a supreme irony, following his death in 1852 from an overdose of opiates, he ended up as a specimen himself with his scoliosis-wracked spine preserved in a jar in the collection of his nemesis Richard Owen.It was Owen therefore who ended up as the public face of the study of dinosaurs, having coined the word itself in 1842 and presided over the creation of full scale models of iguanodon and megalosaurus to be exhibited in Crystal Palace Park in 1853. Six years later however his opposition to Darwin’s theories would leave his credibility permanently tarnished in the eyes of a new generation of scientists.Overlooked and somewhat sneered at in the refined air of academic circles at the time was another tireless bone digger named Mary Anning, who today is probably better known than most of those mentioned above for the same reason that she was scorned at the time. As a woman in a man's world and lacking a university education to boot, Mary Anning could never hope for inclusion at the top table. Dependant for much of her life upon charity and reliant on searching the cliffs of Lyme Regis for fossil remains which she could then sell to wealthy collectors, Mary could be dismissed as merely a finder and seller of fossils. Those who knew better knew her to be an expert in the location and identification of fossil remains and a first rate self-taught anatomist. Buckland, Mantell and Owen all beat a path to her door and her abilities were respected throughout the academic world. Her discovery of ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and pterosaurs in the Dorset cliffs introduced prehistoric creatures of the deep and of the air into the public consciousness.

Mary Anning 1799-1847Mary Anning died from breast cancer in 1847, fondly remembered by the academic establishment but hardly lauded. Her story alone however was the only one it was deemed necessary for me to have been taught about school, a fact which doubtless had more to do with her gender than her accomplishments. From my viewpoint the greatest compliment one can pay notable women from the pages of history is neither to tolerate the prejudices that they endured in their own day, nor to subscribe to the modern agendas that seek to put them on a pedestal, but simply to give them their due. That, after all, is all most of them ever wanted. This example of an ichthyosaur discovered by Anning which today resides in the Sedgwick Museum illustrates the lack of recognition that she received for her discoveries. It is not Anning's name writ large upon the slab but that of the donor Thomas Hawkins;author of a fanciful work entitled The Book of Great Sea Dragons, whom William Buckland described as 'A young man with more money than wit.' Hawkins was in the habit of adding extra bones to the specimens he purchased from Anning to make them appear more complete, a practice which Anning herself frowned upon.In her own lifetime Mary Anning described herself as 'ill-used' by the academic community. In modern times she has found a measure of restitution. And when we look upon the treasures she unearthed, who would begrudge her that?

Mary Anning 1799-1847Mary Anning died from breast cancer in 1847, fondly remembered by the academic establishment but hardly lauded. Her story alone however was the only one it was deemed necessary for me to have been taught about school, a fact which doubtless had more to do with her gender than her accomplishments. From my viewpoint the greatest compliment one can pay notable women from the pages of history is neither to tolerate the prejudices that they endured in their own day, nor to subscribe to the modern agendas that seek to put them on a pedestal, but simply to give them their due. That, after all, is all most of them ever wanted. This example of an ichthyosaur discovered by Anning which today resides in the Sedgwick Museum illustrates the lack of recognition that she received for her discoveries. It is not Anning's name writ large upon the slab but that of the donor Thomas Hawkins;author of a fanciful work entitled The Book of Great Sea Dragons, whom William Buckland described as 'A young man with more money than wit.' Hawkins was in the habit of adding extra bones to the specimens he purchased from Anning to make them appear more complete, a practice which Anning herself frowned upon.In her own lifetime Mary Anning described herself as 'ill-used' by the academic community. In modern times she has found a measure of restitution. And when we look upon the treasures she unearthed, who would begrudge her that?

Ichthyosaur - Sedgwick Museum Cambridge

Ichthyosaur - Sedgwick Museum Cambridge Robert Plothttp://www.strangescience.net/plot.htmJames Huttonhttp://www.amnh.org/education/resources/rfl/web/essaybooks/earth/p_hutton.htmlWilliam Bucklandhttp://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/learning/pdfs/buckland.pdfGideon Mantellhttp://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/geology/chamber/mantell.htmlMary Anninghttp://www.sdsc.edu/ScienceWomen/anning.html

You may also enjoy: Austen Henry Layard - Discover of Ninevehhttp://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/austen-henry-layard-discoverer-of.html

Published on November 04, 2013 23:58

October 14, 2013

Andromeda Rising

Winter is coming as they say in Westeros and with the return of dark evenings I found myself on Saturday night scurrying back and forth from the garden where the trusty scope had been trained on the patch of sky above the neighbour’s fence, frowning at the scudding clouds.

At last the sky cleared at least for a while and I cranked, swivelled and twiddled my way through the rising constellation of Andromeda until finally I beheld a cloud-like entity amongst the stars. Having repeatedly checked that the object of interest was neither a rogue regular cloud drifting across my field of view nor a greasy spot on the eyepiece, I pronounced myself satisfied that I had indeed eyeballed the Andromeda galaxy and wished as usual that I had invested in a larger telescope. Even so, it was still another tottering step forward in my astronomical adventures and one has to start somewhere.

Andromeda Galaxy as photographed by Isaac Roberts 1888 Just then the clouds closed in once more and ended my observations for the evening and I retired to the comfort of the living room. Whenever I feel like grumbling about the limitations of my present technology I remind myself that the pioneers of astronomy would have killed to have a telescope as good my much disparaged 76mm and that they made incredible discoveries and deductions using far more primitive instruments.

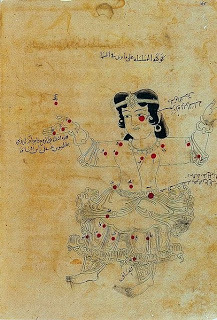

Andromeda Galaxy as photographed by Isaac Roberts 1888 Just then the clouds closed in once more and ended my observations for the evening and I retired to the comfort of the living room. Whenever I feel like grumbling about the limitations of my present technology I remind myself that the pioneers of astronomy would have killed to have a telescope as good my much disparaged 76mm and that they made incredible discoveries and deductions using far more primitive instruments.The first man known to have observed the Andromeda galaxy did not even have a telescope. Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, known in the west as Azophi, was a Persian astronomer living in Isfahan during the Tenth Century. Having studied and augmented the works of Ptolemy, Al Sufi compiled his own Book of Fixed Stars, which was completed in 962 AD. Within it he describes a small cloud located within the constellation of Andromeda.

The Constellation of Andromeda as pictured in the Bodleian Library's copy of Al Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars It was not until 1612 that the Andromeda galaxy was observed by a European astronomer; Simon Marius, who is best known for infuriating Galileo by claiming to have observed the moons of Jupiter prior to Galileo’s own discovery which he announced in his seminal Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Marius’ claim to have been the first was largely discredited but his re-discovery of Andromeda stands as his signal achievement.

The Constellation of Andromeda as pictured in the Bodleian Library's copy of Al Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars It was not until 1612 that the Andromeda galaxy was observed by a European astronomer; Simon Marius, who is best known for infuriating Galileo by claiming to have observed the moons of Jupiter prior to Galileo’s own discovery which he announced in his seminal Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Marius’ claim to have been the first was largely discredited but his re-discovery of Andromeda stands as his signal achievement.Andromeda, designated M31, is flanked by two satellite dwarf galaxies. The first of these M32 was discovered by French astronomer Guillaume le Gentil , who was perhaps the unluckiest man in the history of astronomy.

Le Gentil set out in 1760 to observe the 1761 transit of Venus from Pondicherry, India. Prevented from reaching his destination by the outbreak of war between England and France, Le Gentil was at sea at the time of the transit and his efforts to observe it from the deck of the ship in rough weather were hopeless. Undeterred, he determined to wait for the next transit in eight years’ time. He spent the intervening years fruitfully, travelling the Indian Ocean on mapmaking expeditions, carrying out astronomical observations and recording details of flora and fauna. When the time came around for the next transit, Le Gentil returned to Pondicherry only to be thwarted once more by storm clouds. His frustration can only be imagined. When at last he returned to France he found that he had been given up for dead and his relatives were squabbling over his estate.

That is the fate that often awaits astronomers. I had gone more than ten thousand leagues; it seemed that I had crossed such a great expanse of seas, exiling myself from my native land, only to be the spectator of a fatal cloud which came to place itself before the Sun at the precise moment of my observation, to carry off from me the fruits of my pains and of my fatigue.Guillaume le Gentil 1769

Caroline Herschel The second satellite galaxy of Andromeda, designated M110, was discovered in 1783 by Caroline Herschel, sister of William, who through the course of assisting her more celebrated brother became an accomplished astronomer in her own right. Caroline blazed a trail by becoming the first woman to receive a state salary for undertaking scientific endeavours. As she moved from under her brother’s shadow and began to make her own independent discoveries Caroline identified eight new comets as well as the galaxy M110. Following her brother’s death Caroline, who never married, returned to Germany and lived to the ripe old age of 97, receiving a gold medal from the King of Prussia for her scientific efforts.

Caroline Herschel The second satellite galaxy of Andromeda, designated M110, was discovered in 1783 by Caroline Herschel, sister of William, who through the course of assisting her more celebrated brother became an accomplished astronomer in her own right. Caroline blazed a trail by becoming the first woman to receive a state salary for undertaking scientific endeavours. As she moved from under her brother’s shadow and began to make her own independent discoveries Caroline identified eight new comets as well as the galaxy M110. Following her brother’s death Caroline, who never married, returned to Germany and lived to the ripe old age of 97, receiving a gold medal from the King of Prussia for her scientific efforts.I was interested to learn that the reason all deep sky objects are given a number with a prefix M, is due to one Charles Messier - 1730-1817 - another good innings! Messier was a prodigious hunter of comets, indeed he discovered thirteen of the things and to aid fellow comet hunters he helpfully created a catalogue of nebulous objects in the night's sky. It is for Messier therefore that M31 and all other nebulous celestial phenomena are so named. For his achievements Messier received the Legion d'Honeur. He is buried in Pere Lachaise cemetery.

Charles Messier

Charles MessierAndromeda’s beautiful spiral structure was first elucidated by Welsh astrophotography pioneer Isaac Roberts whose magnificent long exposure photograph appears at the top of this post. It was taken in 1888 by mounting a photographic plate in the prime focus position within his twenty inch telescope housed in a purpose built observatory at the bottom of his garden.

Roberts had shown the Andromeda galaxy in detail but it was still thought to be a nebula within the Milky Way rather than an entirely separate and far more distant galaxy. The debate was soon raging however as to whether our own galaxy comprised the universe entire or whether it was just one of many galaxies in an infinitely larger ‘island universe’. In 1924 Edwin Hubble, by observing the Andromeda Galaxy through the 100 inch Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, discovered the means to settle the argument once and for all.

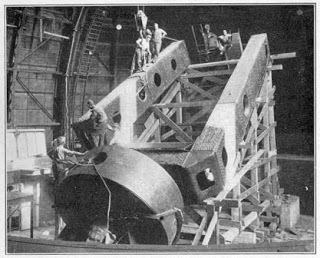

The Hooker Telescope under construction

The Hooker Telescope under construction Hubble identified the presence of Cepheid variable stars within the Andromeda Galaxy, whose brightness varies over time in regular pulses. By measuring their pulsation periods, Hubble was able to calculate their luminosity since the two are relative. By comparing the observed and expected luminosities of the stars, Hubble was able to deduce their distance from the earth at some 900,000 light years. He thus demonstrated that they were so distant that they must lie outside of the Milky Way, the size of which had already been estimated at 100,000 light years. Hubble had proved that the universe was comprised of many galaxies and was a bigger place than anyone had previously imagined. Indeed he underestimated in his calculations, for Andromeda is now known to be two million light years away.

And when I think about that I am definitely impressed to have seen it at all!

Al Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/al%20sufi%20van%20gent.pdfThe ordeal of Guillaume le Gentil

http://princetonastronomy.wordpress.com/2012/02/06/the-ordeal-of-guillaume-le-gentil/Edwin Hubble

http://cosmology.carnegiescience.edu/timeline/1929You may also enjoy

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/by-jove-story-of-jupiter.html

Published on October 14, 2013 17:05

October 2, 2013

Turning back the tide - The rule of Julian the Apostate

Of all the rulers of the Roman world one of the most remarkable must be Julian the Apostate; a man who sought to turn the clock back and restore Rome to a past glory which he believed had been lost with the coming of Christianity. It is difficult not to develop an admiration for Julian, who for a brief time turned the Roman world on its head. Ultimately Julian was unsuccessful in his efforts and has gone down as something of a failure who struggled against the tide of history but nevertheless he was a man of courage and integrity whose misfortune was perhaps to have been born too late.

The emperor JulianJulian was raised to power by his cousin Constantius; last surviving son of the great Christianising emperor Constantine. The sole reign of Constantius over the Roman world began in 351 AD and soon became a reign of terror. Good men met their deaths as a result of vicious court gossip and were on occasion driven to rebel simply because they had been left with no other choice. Most infamous of Constantius’ informants was a man known as Paul the Chain, due to his ability to fabricate such a weight of evidence against even innocent men that it became inescapable. In such an atmosphere of dread then, grew up Constantius’ cousins Gallus and Julian. They had already seen every male member of their family murdered upon the accession of Constantine’s sons in a bloody purge reminiscent of the days of the Julio-Claudians. It must have seemed to them only a matter of time until they would be considered a threat and eliminated. Shortly after taking sole power however Constantius elected to make Gallus his junior colleague; investing him with the rank of Caesar and dispatching him to Antioch to administer the east. The new Caesar promptly embarked upon a reckless course of debauchery and corruption which led inexorably to his downfall. His growing unpopularity soon sparked a whispering campaign in the court of Constantius and Gallus’ days were henceforth numbered. Lured westwards to a conference with Constantius in 354, Gallus was intercepted by his cousin’s henchmen and found himself bound and beheaded like a common criminal. His body was then mutilated and his head sent to Constantius in Milan.

The emperor JulianJulian was raised to power by his cousin Constantius; last surviving son of the great Christianising emperor Constantine. The sole reign of Constantius over the Roman world began in 351 AD and soon became a reign of terror. Good men met their deaths as a result of vicious court gossip and were on occasion driven to rebel simply because they had been left with no other choice. Most infamous of Constantius’ informants was a man known as Paul the Chain, due to his ability to fabricate such a weight of evidence against even innocent men that it became inescapable. In such an atmosphere of dread then, grew up Constantius’ cousins Gallus and Julian. They had already seen every male member of their family murdered upon the accession of Constantine’s sons in a bloody purge reminiscent of the days of the Julio-Claudians. It must have seemed to them only a matter of time until they would be considered a threat and eliminated. Shortly after taking sole power however Constantius elected to make Gallus his junior colleague; investing him with the rank of Caesar and dispatching him to Antioch to administer the east. The new Caesar promptly embarked upon a reckless course of debauchery and corruption which led inexorably to his downfall. His growing unpopularity soon sparked a whispering campaign in the court of Constantius and Gallus’ days were henceforth numbered. Lured westwards to a conference with Constantius in 354, Gallus was intercepted by his cousin’s henchmen and found himself bound and beheaded like a common criminal. His body was then mutilated and his head sent to Constantius in Milan. Given the fate of his half-brother, it must have been with some trepidation in the following year that the scholarly Julian, who had been living the laid back life of a student philosopher in Athens, received his call up; being elevated to the purple as Caesar in Gallus’ stead. Unlike his unfortunate sibling Julian was not to be entrusted by Constantius with control of the east. Unwilling to risk his becoming a second Gallus, Constantius instead dispatched Julian westwards to Gaul whilst himself taking control of matters on the Danube frontier where the Sarmatians were making trouble.

On the face of it, the troops stationed on the Rhine might not have made much of the unassuming twenty four year old bearded intellectual sent to take over their destiny. He would not have seemed like much of a soldier but would prove to be something of a revelation, taking to military life like a duck to water.

In the campaigning season of 357, Julian found himself in command of a small army of thirteen thousand men tasked with taking the fight to the Alamanni who were at this time united under the strong leadership of a king named Chnodomarius. This strongman had extended his authority over seven other principle kings of the Alamanni and a number of lesser ones and had assembled an unusually large force with which he had advanced into Gaul. Julian was supposed to be acting in concert with a larger Roman force of twenty five thousand men under the command of the Master of Soldiers Barbatio, who as the experienced military man in the western theatre was in theory meant to be keeping an eye on the young Caesar. Instead Barbatio was busy doing everything in his power to undermine and hinder Julian, refusing to march to his aid and burning supplies and equipment required by his forces. Julian therefore found himself outnumbered by perhaps as many as three to one as he advanced to confront the Alamanni near Strasbourg.

Unperturbed and encouraged by his officers Julian attacked at dawn and a fierce battle developed. The Alamanni had the best of the early action, routing the Roman cavalry on the right wing. Julian himself rallied the fleeing horsemen and led them back into the battle where the Alamanni, led by their kings, were battering the Roman infantry with sword and axe and the Romans were desperately hanging on. For a time the battle hung in the balance but as the barbarian horde began to lose cohesion, the superior discipline of the Romans began to tell and the Alamanni were driven back against the banks of the Rhine where many drowned attempting to escape. Chnodomarius was captured and sent to Rome where he died a prisoner. It was a glorious victory which shattered Alamannic power for a generation and confirmed Julian’s military reputation whilst cementing the loyalty of his troops. He continued to lead them in punitive expeditions against the Alamanni and the Franks, who were also stepping up their incursions into northern Gaul.

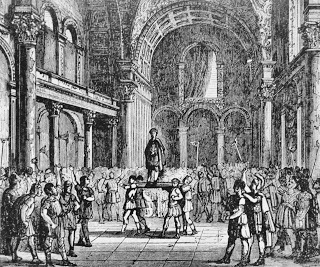

Julian crowned - 19th century engraving depicting the raising on a shield

Julian crowned - 19th century engraving depicting the raising on a shieldIn the following year the Persians under their new king Shapur II made a serious incursion into Roman territory. Shapur had subjected the city of Amida on the Tigris to a vicious sack after the son of one of his client kings was skewered by a bolt from a Roman catapult, having ridden too close to the walls of the besieged city in order to taunt the defenders. As Constantius prepared to respond, he requested that Julian send him several units of auxillia from his own forces to augment the effort against the Persians. Julian pointed out that these Gallic units had received guarantees as part of their terms of enlistment that they would not be asked to serve beyond the Alps. Constantius nevertheless insisted and Julian had no choice but to comply with the predictable result that his troops rioted. Surrounding his headquarters they demanded that Julian show himself and when he appeared before them they loudly proclaimed him as Augustus. We are told that Julian accepted his elevation only with great reluctance and attempted to placate Constantius with assurances that the army had left him with no choice but to acquiesce to their wishes. An outraged Constantius was having none of it and demanded that his upstart cousin renounce the purple at once, upbraiding him for his ingratitude and reminding him that it was he who had arranged for Julian’s care and education when he had been an orphaned child. This last outrageous statement was too much for Julian who incredulously declared to his troops that it was because of the murderous conduct of Constantius and his brothers that he had been made an orphan in the first place. Now he raised the standard of revolt and marched against his cousin; launching a lightning campaign which saw his troops reach the Danube and lay siege to the city of Sirmium before word reached Constantius that he had even left Gaul. In Rome the Senate acknowledged Julian as their sovereign and were gratified by the respectful tone in which he addressed his communications to them. Constantius at last responded to the threat and began to make his way westward. On his way to confront Julian however he fell ill and died at Tarsus in 361. On his deathbed he acknowledged Julian as his rightful successor, sparing the empire further bloodshed.

From unlikely beginnings the scholar turned soldier had found himself as master of the Roman world. Julian now lost no time in setting about turning the clock back, for in what had become a largely Christian empire, the new emperor was unashamedly pagan. The old temples were reopened and across the empire smoke rose once more from sacrificial alters. Where pagan temples had been demolished to make way for churches the process was reversed and the Christians made to foot the bill. The Jews too were given permission to rebuild their temple in Jerusalem although this was never accomplished. When Syrian Christians retaliated against these measures by allegedly burning the temple of Apollo at Daphne there were ruthless reprisals but generally Julian sought a return to tolerance rather than persecution. The emperor understood that this was a more sensible policy since oppression would only unite the Christians whereas allowing schismatic groups to practice freely would deepen their divisions. Naturally the emperor favoured fellow pagans over Christians and many who had been appointed to positions of authority now found themselves out of favour. Julian also barred Christians from educating the young since he considered them unfit to do so by virtue of their rejection of the classical past. All of this naturally made the new emperor deeply unpopular with the Christian church although the Senate enjoyed something of a renaissance under Julian, who showed them more respect than any emperor had for generations as he indulged his nostalgia for the old Republic.

Julian the philosopher emperor

Julian the philosopher emperorIn 363 Julian prepared to invade Persia. He was keen to emulate the achievements of Alexander and Trajan whom he greatly admired and hoped that by doing so he could usher in a new golden age in which the gods and the fortunes of Rome would be restored. To this end he assembled a substantial force of perhaps as many as sixty thousand men, to be supplied by a thousand barges which would make their way down the Euphrates and strike at Ctesiphon. A second force of thirty thousand men were to advance from Armenia supported by the Armenian king in order to draw the forces of Shapur northwards whilst Julian swept down upon the poorly defended Persian capital.

At first everything went well as Julian’s army marched down the Euphrates overcoming all opposition and capturing the Persian strongholds that stood in his way. The emperor was conspicuous in his daring to the point of recklessness, missing no opportunity to be at the heart of the action and exposing himself to danger. On one occasion Julian was surprised by two would-be Persian assassins whilst on a scouting mission and fought them off; felling one of the assailants with a sword thrust.

As the army drew closer to Ctesiphon, Persian resistance stiffened and the pace of advance slowed. The Romans nevertheless continued to clobber their way into the fortified towns along the Euphrates with ram and ballista or sometimes negotiate the garrisons’ surrender through the persuasive eloquence of Hormisdas; an exiled Persian noble with a tenuous claim to the throne who perhaps hoped that Julian would place him upon it.

The defence of the capital had been entrusted to the Surenas; Shapur’s leading general. His forces now began to harass the column and to burn crops in the Roman line of advance but Julian pressed on unperturbed, comfortably supplied from his barges. He made use of a disused canal which had originally been dug by Trajan in order to move his fleet from the Euphrates into the Tigris so that they could continue to support his advance. The approach to Ctesiphon was guarded by a formidable fortress by the name of Maogamalcha to which the Romans laid siege. With the chances of success for a direct assault looking slim, Julian’s engineers commenced digging a tunnel under the walls. Julian’s forces then mounted a diversionary attack on the walls whilst a force of fifteen hundred picked men made their way through the tunnel and emerged in the unsuspecting enemy’s rear, overwhelming the surprised defenders and opening the gates.

The army moved on to the old capital of Seleucia where they forced a crossing of the Tigris at night. The attack almost met with disaster when the advance party sent across the river was intercepted by the Persians and their boats were set ablaze. Thinking on his feet, the emperor announced to his troops that the fire that they could see across the river was the agreed signal for a successful landing and ordered them all forward. Those who could not make it into a boat swam across using their shields as floats and the Persians were beaten back. The Romans then engaged the forces of the Surenas in battle within sight of the walls of Ctesiphon. The Romans had the best of the battle with Julian fighting in the front line and the Persians fled into the city.

With victory in sight however, the expected troops who were supposed to be advancing from Armenia failed to materialise and without them Julian was not confident of taking the Persian capital. Neither however was the emperor ready to make peace and he rejected envoys from the Surenas. Persuaded instead by Persian deserters who encouraged him to march further into their land with assertions that support for Shapur would crumble in the face of a bold Roman advance, Julian gave orders for the fleet to be burned, since it could not make its way back up the Tigris against the current.

The soldiers were much disheartened by this turn of events as they marched away from the smouldering remains of their fleet, advancing through a land stripped bare of supplies. The Persian deserters, who in reality remained loyal to their king, treacherously led the Romans in circles and then abandoned them as Shapur’s army moved in. Now desperately short of supplies, Julian decided to retreat towards the Tigris. As the Persians harassed the Roman column Julian once again became careless of his personal safety and whilst leading a counter attack was fatally wounded by a javelin. It took the emperor several hours to die, facing death calmly and stoically and declaring that he had no regrets. He named no successor and only expressed his hope that a suitable candidate may be found.

So passed Julian the Apostate, one of the most remarkable men to rule over the Roman world and one whose passing marked the end of an era. His attempts to turn back the tide of Christianity died with him as did his dream of reviving the military glories of the past. From here on in Rome would be on the defensive.

Monument of Shapur II thought to depict the fallen Julian Julian left no heir and since he was the last surviving male member of the house of Constantine there was no obvious choice of successor. The army settled on an obscure officer by the name of Jovian who seems to have been elected almost by accident and did little to distinguish himself subsequently. Shapur had the new emperor right where he wanted him and extracted from Jovian a most dishonourable peace in return for the army’s safe passage. And so the army turned for home. The remains of Julian were laid to rest in the city of Tarsus along the way.

Monument of Shapur II thought to depict the fallen Julian Julian left no heir and since he was the last surviving male member of the house of Constantine there was no obvious choice of successor. The army settled on an obscure officer by the name of Jovian who seems to have been elected almost by accident and did little to distinguish himself subsequently. Shapur had the new emperor right where he wanted him and extracted from Jovian a most dishonourable peace in return for the army’s safe passage. And so the army turned for home. The remains of Julian were laid to rest in the city of Tarsus along the way. Julian has left us one insight into his mind through his comic sketch ‘The Caesars’ in which all the past rulers of Rome attend a banquet with the Gods of Olympus along with Alexander the Great. Whilst some are cast down for their crimes, the greatest amongst them compete for the recognition of the Gods as the foremost of their company. In the end Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius and Constantine make their cases. Caesar and Alexander bicker like schoolboys over the top honours but Julian’s admiration for both shines through. Augustus shows himself to be wise and Trajan is too quick tempered whilst Constantine ends up as a laughing stock. It is Marcus Aurelius however whom the Gods most favour. Of all his predecessors, it was the philosopher emperor whom Julian most admired and most closely sought to emulate. I should like to think that when Julian took his own place amongst the Caesars at the great Olympian banquet, he gave a good account of himself and was not found wanting.

The trial that begins

Awards to him who wins

The fairest prize to-day.

And lo, the hour is here

And summons you. Appear!

Ye may no more delay.

Come hear the herald's call

Ye princes one and all.

Many tribes of men

Submissive to you then!

How keen in war your swords!

But now 'tis wisdom's turn;

Now let your rivals learn

How keen can be your words.

Wisdom, thought some, is bliss

Most sure in life's short span;

Others did hold no less

That power to ban or bless

Is happiness for man.

But some set Pleasure high,

Idleness, feasting, love,

All that delights the eye;

Their raiment soft and fine,

Their hands with jewels shine,

Such bliss did they approve.

But whose the victory won

Shall Zeus decide alone.

The Caesars

http://www.attalus.org/translate/caesars.html

Ammianus Marcellinus on Julian

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Ammian/23*.html

You may also enjoy: Justinian II - Mad, Bad and Dangerous

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/justinian-ii-mad-bad-and-dangerous.html

I was lazy for this article and reused material from my own book The Battles are the Best Bits, but if you liked it please check out the book. http://www.amazon.com/The-Battles-Best-Bits-ebook/dp/B008GT05IY

Published on October 02, 2013 01:06

September 1, 2013

Operation Torch in Morocco

As I am off to Morocco later this week, here is another Morocco related post. This one is on a more recent subject.

On 8th November 1942 a US Invasion fleet launched an amphibious assault on Moroccan soil against the occupying Vichy French forces in one of the three prongs of the North African landings known as Operation Torch. The other landings occurred simultaneously on the coasts of Tunisia and Algeria.

US Tanks on the quayside waiting to embark on Operation Torch The level of expected resistance was unknown. Furtive diplomatic efforts had been undertaken in the hope of persuading the Vichy French command not to resist but the level of success of these overtures was difficult to ascertain with any certainty. It was therefore decided that the initial landings should be undertaken by US forces since the Vichy French defenders were less likely to bear any ill will towards Americans rather than the British. The assault on Casablanca under the command of General George Patton would be the only one of the three to be an entirely American operation. A total force of a little under 45,000 men sailed directly from the US, escorted by a naval task force under the command of Admiral Henry Hewitt. The invasion fleet numbered 102 ships in total. They would face a defending force made up mostly of native troops under French officers. In addition the port contained a collection of French warships and submarines of which the partially built battleship Jean Bart was the largest. Having fled St Nazaire in 1940 to escape capture, the Jean Bart had been laid up in Casablanca ever since. One turret of her main armament of 15 inch guns was operational and able to pose a threat to American shipping.

US Tanks on the quayside waiting to embark on Operation Torch The level of expected resistance was unknown. Furtive diplomatic efforts had been undertaken in the hope of persuading the Vichy French command not to resist but the level of success of these overtures was difficult to ascertain with any certainty. It was therefore decided that the initial landings should be undertaken by US forces since the Vichy French defenders were less likely to bear any ill will towards Americans rather than the British. The assault on Casablanca under the command of General George Patton would be the only one of the three to be an entirely American operation. A total force of a little under 45,000 men sailed directly from the US, escorted by a naval task force under the command of Admiral Henry Hewitt. The invasion fleet numbered 102 ships in total. They would face a defending force made up mostly of native troops under French officers. In addition the port contained a collection of French warships and submarines of which the partially built battleship Jean Bart was the largest. Having fled St Nazaire in 1940 to escape capture, the Jean Bart had been laid up in Casablanca ever since. One turret of her main armament of 15 inch guns was operational and able to pose a threat to American shipping.Patton planned to land his troops on three sites. The principle landing at Fedala (Codename Brushwood), 18 miles north of Casablanca would see the majority of the troops put ashore to advance upon the city. A second force would land at Safi (Codename Blackstone), 140 miles to the south with the objective of seizing the port and putting tanks ashore which would then race to attack Casablanca. A third force landing at Port Lyautey (Codename Goalpost), was tasked with the capture of a key airfield which would allow supporting air forces to be flown in from Gibraltar.

Patton and Hewitt aboard USS Augusta On the night of 7th November an attempted coup by pro-Allied French elements failed to capture the headquarters of the Vichy commander Gen. Nogues.

Patton and Hewitt aboard USS Augusta On the night of 7th November an attempted coup by pro-Allied French elements failed to capture the headquarters of the Vichy commander Gen. Nogues.The Safi landing under Gen. Harman was completed successfully for the loss of only 4 American lives. The port was swiftly taken although sporadic resistance continued for a further two days.

At Port Lyautey the assault on the airfield under Gen. Truscott was held up by stiff resistance mounted by 85 defenders occupying an ancient kasbah. These defenders were finally circumvented when the destroyer USS Dallas was able to make its way up the Sebou River before running aground and turning her guns on the kasbah whilst commandos advanced to the airfield by boat. Resistance from the kasbah was finally overcome by a combination of shelling and bombing by land, sea and air.

At Fedala the landings began smoothly enough with early morning fog providing cover for the landing craft and three and a half thousand men were put ashore before dawn. At approximately 7am however the defenders opened fire upon the landing troops. Shore batteries opened up supported by the guns of the Jean Bart.

The standing orders for the invaders had been to fire only once fired upon by the defenders in the hope of a bloodless victory. As the first shots were fired however the coded message ‘Batter Up!’ crackled over the airwaves to be greeted by the response, ‘Play Ball!’ The order to return fire had been given.

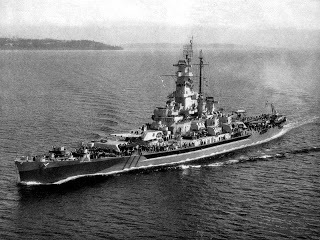

USS Massachusetts

USS MassachusettsJean Bart managed to fire seven salvos before a shell from the USS Massachusetts, the only battleship in the US task force, succeeded in jamming the rotating mechanism of the turret and putting it out of action. 3 French submarines were destroyed at their moorings by shelling and aerial attack.

A sortie by the remaining operational 1 French light cruiser, 6 destroyers and 5 submarines had little effect on the US force. Heavily outgunned by the American cruisers and battleship and under attack by aircraft from the carriers Ranger and Suwannee the destroyers were all sunk or forced by damage to run aground. The light cruiser Primauguet and two destroyers made it back into port but all were badly damaged. The cruiser was ablaze and was run aground and the two destroyers subsequently capsized. Those submarines which were armed with torpedoes made unsuccessful attacks on the American ships before making a run for the open sea. One was destroyed.

Aircraft on the flight deck of USS Ranger The defenders of Fedala surrendered the port in the face of heavy bombardment from the American ships and the town was swiftly taken. By the end of the first day 8000 men were ashore but only 5 of 77 tanks had been landed and many landing craft had been lost as conditions had deteriorated.

Aircraft on the flight deck of USS Ranger The defenders of Fedala surrendered the port in the face of heavy bombardment from the American ships and the town was swiftly taken. By the end of the first day 8000 men were ashore but only 5 of 77 tanks had been landed and many landing craft had been lost as conditions had deteriorated.On the following day heavy seas made landing supplies increasingly difficult and in the afternoon operations had to be abandoned altogether. The troops were left critically short of many supplies in particular ammunition and radios. Over half of the landing craft had been lost and lifeboats from the fleet had to be pressed into service to bring supplies ashore.

By the end of the day on 10th November the ground troops had advanced to within five miles of Casablanca, under fire from Vichy French artillery. Meanwhile the Jean Bart, which had completed repairs to her turret, resumed firing on the US fleet. The response was a sortie by dive bombers from USS Ranger who scored two direct hits with 1000lb bombs, causing the battleship to settle on the harbour bottom. She would later be refloated and completed and enjoy a long career with the French navy.

Jean Bart docked in Casablanca

Jean Bart docked in Casablanca The final assault on Casablanca was planned for the following morning but the dawn brought the surrender of the city and hostilities were over. Patton was free to turn his troops eastwards and advance towards Tunisia and Rommel’s retreating Afrika Korps. An unexpected blow was dealt to the invasion force when a German U-boat the U130 slipped through the escorts and succeeded in sinking three troop transports.

For Patton it had been a successful operation with minimal loss of life but the logistical nightmares had seen the general lose his famous temper, storming ashore threatening to ‘Flay the idle, rebuke the incompetent and drive the timid.’ He would keep them on their toes all the way to Germany!

An account of the air battle

http://airgroup4.com/torch.htm

Some good pics of the Jean Bart

http://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/france/battleships/jean_bart/jean_bart.htm

More on Operation Torch

http://www.gcsu.edu/history/docs/geog_cap/geog4970_thesis_lubin_2011.pdf

You may also enjoy: Last of the Giants - Yamato and Musashihttp://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/last-of-giants-yamato-and-musashi.html

Published on September 01, 2013 17:52

August 19, 2013

Who were the Saadian Dynasty?

Who indeed? When investigating this question I found that the Saadi were a powerful ruling dynasty responsible for uniting Morocco in the 16th Century in the face of attempted Ottoman pan-Islamic domination and opportunistic Portuguese imperialism. They left behind them the most impressive surviving monuments in the city of Marrakesh, which I shall be visiting next month. Hence my initial query.

I have been to Marrakesh before, twelve years ago, but the visit was relatively fleeting and I did not have time to take in its more historic attractions of which the Saadian tombs and Al Badi Palace are the foremost. Memories of the visit to be truthful are a little hazy if you know what I mean and so I am looking forward to re-making its acquaintance in a more cultured frame of mind.

So, anyway, to return to the question at hand: Who were the Saadian Dynasty?

The archetypal Moorish warrior leader

The archetypal Moorish warrior leader

The Saadian Dynasty began as the major power in the south of Morocco, who mounted a challenge both to the incumbent ruling dynasty of the Wattasid Sultanate centred on Fez and to the Portuguese who had established a number of enclaves along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts from which they sought to control the hinterland and gain access to the riches of the caravan trade in gold and slaves from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The presence of the Portuguese was a key driver behind the emergence of the Saadi as they put pressure on the tribes to select a leader with whom they could negotiate. This leader was regional strongman Abu Abdullah al Qaim who, rather than proving tractable, united the tribes of the south in jihad against the Portuguese. Following his death in 1517 his eldest son Mohammed ash Sheikh succeeded to his position and took up the mantle of jihad. In 1524 the Saadian forces conquered Marrakesh. Three years later Mohammed's rule over the south was acknowledged by the Wattasid regent in Fez, ostensibly as governor, recognising the suzerainity of the Wattasids, but effectively as lord of the south.

The Saadi leader was happy to trade with other European powers in his quest to oust the Portuguese and acquired western gunpowder weapons for his campaigns. In 1541 he turned his weapons against the colony of Agadir. The Saadian forces, bolstered by Ottoman trained freebooters, approached the siege with unexpected professionalism. A Kasbah was constructed atop the hill which dominated the port from which the Saadian artillery could pound away at the Portuguese defences. When a barrel of gunpowder exploded the walls were breached and the city was taken.

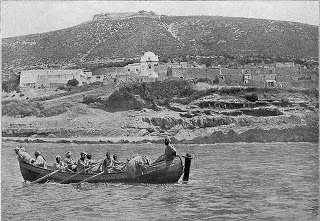

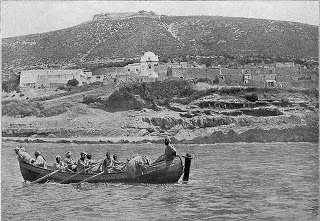

This 1905 photograph shows the commanding position of the Kasbah above Agadir In 1549 Mohammed turned his army against the Wattasid capital of Fez which also fell to his artillery. The city was briefly retaken by the Wattasids with Ottoman assistance five years later but Mohammed marched against them once more and defeated and killed the last Wattasid ruler in the Battle of Tadla fought close to Fez.

This 1905 photograph shows the commanding position of the Kasbah above Agadir In 1549 Mohammed turned his army against the Wattasid capital of Fez which also fell to his artillery. The city was briefly retaken by the Wattasids with Ottoman assistance five years later but Mohammed marched against them once more and defeated and killed the last Wattasid ruler in the Battle of Tadla fought close to Fez.

Mohammed ash Sheikh was seen as a threat by the Ottomans due to his claim of descent from the Prophet through the Fatimid line. He therefore did not recognise the Ottoman claim to the universal Caliphate and refused to acknowledge the Sultan in Constantinople as his nominal overlord. During a tax gathering expedition in the Atlas mountains in 1557 he was assassinated by his Janissary bodyguards.

Mohammed was succeeded by his son Abdullah al-Ghalib who successfully saw off an attempted Ottoman invasion in the following year. Al-Ghalib's reign was marked by political manoeuvring to counter Ottoman aggression by seeking alliance with the Spanish. His brothers al-Mansur and Abd al-Malik found themselves exiled during his reign and made their way to the Ottoman court. Both would fight in the Ottoman fleet at Lepanto in 1571. Abd al-Malik was taken prisoner by the Spanish but later escaped and returned to Constantinople. Al Ghalib died from an asthma attack in 1574 to be succeeded by his son Abdullah Mohammed.

In that same year Abd al-Malik arrived in Tunis with an Ottoman invasion fleet and following the successful capture of the port led a force of ten thousand Ottoman troops inland to take Fez, overthrowing his nephew who fled northwards; eventually finding his way to the court of the young King Sebastian of Portugal.

Sebastian I of Portugal

Sebastian I of Portugal

The 24 year old Sebastian had been raised on dreams chivalric glory combined with Jesuit zeal and the opportunity to lead a military expedition against the infidel, albeit with the aim of restoring Abdullah to the throne was irresistible. The political advantages of expelling the pro-Ottoman Abd al-Malik and replacing him with a Portuguese backed candidate were obvious and so Sebastian set out in 1578 at the head of an army perhaps as large as 20,000 men. It was a mixed force of Portuguese and mercenary troops from all over Europe attracted by the Papal blessing for the expedition and the prospect of loot.

The campaign was a complete disaster. At the Battle of Alcacer Quibir, also known as the Battle of the Three Kings, Sebastian's forces, tired and hungry from their march inland from Tangier, nevertheless mounted a bold but reckless charge against a Muslim force which out-numbered them by perhaps as many as three to one. Having initially driven their enemies back, the Portuguese and their allies were ultimately enveloped and overwhelmed by the superior numbers of the enemy, whose crescent formation allowed them to surge around the flanks. Sebastian himself fought furiously, with three horses being killed under him before at last, wounded in the arm, he was surrounded, overwhelmed and cut to pieces.

In the ensuing rout his army was annihilated. It was a disaster for Portugal which ultimately saw the kingdom annexed by Sebastian's uncle, Philip II of Spain.

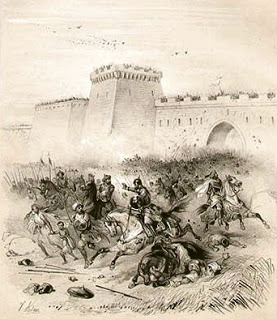

Battle of Alcacer Quibir

Battle of Alcacer Quibir

Abd al-Malik did not live to see his victory however. Already fatally ill at the commencement of hostilities, the Sultan had to be tied onto his horse to keep him upright. By the battle's end he was dead. His brother al-Mansur was declared his successor on the battlefield. The deposed Abdullah Mohammed had also fallen in the battle.

Under Al-Mansur the Saadian dynasty knew its golden age. Enriched by the ransoms of wealthy European prisoners taken at Alcacer Quibir, Al-Mansur was able to beautify his capital of Marrakesh, constructing the magnificent Al Badi Palace, the remains of which stand to this day. He was a ruler with imperial ambitions and sought alliances as far afield as England, dispatching envoys to the court of Elizabeth I to seek an alliance against Spain. In 1591 he sent forth an expedition against the gold-rich Songhai Empire of Mali commanded by a Spanish born eunuch named Judar Pasha. This bold enterprise, marching an army of four thousand soldiers and an additional two thousand non-combatants using eight thousand camels to carry their supplies and equipment which included arquebuses and canons on a 135 day crossing of the Sahara, caught the Songhai ruler entirely unprepared. At Tondibi the opposing forces met and the Malian defenders attempted to disrupt the Moroccan lines by sending ten thousand cattle in a stampede towards them. A volley of canon fire sent the stampede back towards the Malian lines and thus their own tactic rebounded upon them. The superior professionalism and firepower of the mostly mercenary Moroccan army carried the day. Reinforcement by a second expedition led to the swift collapse of the Songhai Empire and the occupation of its legendary cities of Gao, Djenne and Timbuktu which the Moroccans would control for the next thirty years before the logistical demands of maintaining such a far flung imperial possession proved too much.

A Nineteenth Century depiction of Timbuktu

A Nineteenth Century depiction of Timbuktu

Al Mansur died from the plague in 1603. He was succeeded by two of his sons ruling separately in Marrakesh and Fez and so began the inevitable decline of the Saadian Dynasty as twenty five years of civil war beckoned, at the conclusion of which their empire was left fragmented and largely in the hands of local potentates, the Spanish or the Turks.

Rise of the Saadians

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=jdlKbZ46YYkC&pg=PA211&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Battle of Alcacer Quibir

http://warfarehistorian.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/battle-of-ksar-el-kebir-morocco-1578.html?spref=tw

Expedition to Mali

http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/morco_1591.html

You may also enjoy - Austen Henry Layard - Discoverer of Nineveh

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/austen-henry-layard-discoverer-of.html

I have been to Marrakesh before, twelve years ago, but the visit was relatively fleeting and I did not have time to take in its more historic attractions of which the Saadian tombs and Al Badi Palace are the foremost. Memories of the visit to be truthful are a little hazy if you know what I mean and so I am looking forward to re-making its acquaintance in a more cultured frame of mind.

So, anyway, to return to the question at hand: Who were the Saadian Dynasty?

The archetypal Moorish warrior leader

The archetypal Moorish warrior leaderThe Saadian Dynasty began as the major power in the south of Morocco, who mounted a challenge both to the incumbent ruling dynasty of the Wattasid Sultanate centred on Fez and to the Portuguese who had established a number of enclaves along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts from which they sought to control the hinterland and gain access to the riches of the caravan trade in gold and slaves from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The presence of the Portuguese was a key driver behind the emergence of the Saadi as they put pressure on the tribes to select a leader with whom they could negotiate. This leader was regional strongman Abu Abdullah al Qaim who, rather than proving tractable, united the tribes of the south in jihad against the Portuguese. Following his death in 1517 his eldest son Mohammed ash Sheikh succeeded to his position and took up the mantle of jihad. In 1524 the Saadian forces conquered Marrakesh. Three years later Mohammed's rule over the south was acknowledged by the Wattasid regent in Fez, ostensibly as governor, recognising the suzerainity of the Wattasids, but effectively as lord of the south.

The Saadi leader was happy to trade with other European powers in his quest to oust the Portuguese and acquired western gunpowder weapons for his campaigns. In 1541 he turned his weapons against the colony of Agadir. The Saadian forces, bolstered by Ottoman trained freebooters, approached the siege with unexpected professionalism. A Kasbah was constructed atop the hill which dominated the port from which the Saadian artillery could pound away at the Portuguese defences. When a barrel of gunpowder exploded the walls were breached and the city was taken.

This 1905 photograph shows the commanding position of the Kasbah above Agadir In 1549 Mohammed turned his army against the Wattasid capital of Fez which also fell to his artillery. The city was briefly retaken by the Wattasids with Ottoman assistance five years later but Mohammed marched against them once more and defeated and killed the last Wattasid ruler in the Battle of Tadla fought close to Fez.

This 1905 photograph shows the commanding position of the Kasbah above Agadir In 1549 Mohammed turned his army against the Wattasid capital of Fez which also fell to his artillery. The city was briefly retaken by the Wattasids with Ottoman assistance five years later but Mohammed marched against them once more and defeated and killed the last Wattasid ruler in the Battle of Tadla fought close to Fez.Mohammed ash Sheikh was seen as a threat by the Ottomans due to his claim of descent from the Prophet through the Fatimid line. He therefore did not recognise the Ottoman claim to the universal Caliphate and refused to acknowledge the Sultan in Constantinople as his nominal overlord. During a tax gathering expedition in the Atlas mountains in 1557 he was assassinated by his Janissary bodyguards.

Mohammed was succeeded by his son Abdullah al-Ghalib who successfully saw off an attempted Ottoman invasion in the following year. Al-Ghalib's reign was marked by political manoeuvring to counter Ottoman aggression by seeking alliance with the Spanish. His brothers al-Mansur and Abd al-Malik found themselves exiled during his reign and made their way to the Ottoman court. Both would fight in the Ottoman fleet at Lepanto in 1571. Abd al-Malik was taken prisoner by the Spanish but later escaped and returned to Constantinople. Al Ghalib died from an asthma attack in 1574 to be succeeded by his son Abdullah Mohammed.

In that same year Abd al-Malik arrived in Tunis with an Ottoman invasion fleet and following the successful capture of the port led a force of ten thousand Ottoman troops inland to take Fez, overthrowing his nephew who fled northwards; eventually finding his way to the court of the young King Sebastian of Portugal.

Sebastian I of Portugal

Sebastian I of PortugalThe 24 year old Sebastian had been raised on dreams chivalric glory combined with Jesuit zeal and the opportunity to lead a military expedition against the infidel, albeit with the aim of restoring Abdullah to the throne was irresistible. The political advantages of expelling the pro-Ottoman Abd al-Malik and replacing him with a Portuguese backed candidate were obvious and so Sebastian set out in 1578 at the head of an army perhaps as large as 20,000 men. It was a mixed force of Portuguese and mercenary troops from all over Europe attracted by the Papal blessing for the expedition and the prospect of loot.

The campaign was a complete disaster. At the Battle of Alcacer Quibir, also known as the Battle of the Three Kings, Sebastian's forces, tired and hungry from their march inland from Tangier, nevertheless mounted a bold but reckless charge against a Muslim force which out-numbered them by perhaps as many as three to one. Having initially driven their enemies back, the Portuguese and their allies were ultimately enveloped and overwhelmed by the superior numbers of the enemy, whose crescent formation allowed them to surge around the flanks. Sebastian himself fought furiously, with three horses being killed under him before at last, wounded in the arm, he was surrounded, overwhelmed and cut to pieces.

In the ensuing rout his army was annihilated. It was a disaster for Portugal which ultimately saw the kingdom annexed by Sebastian's uncle, Philip II of Spain.

Battle of Alcacer Quibir

Battle of Alcacer QuibirAbd al-Malik did not live to see his victory however. Already fatally ill at the commencement of hostilities, the Sultan had to be tied onto his horse to keep him upright. By the battle's end he was dead. His brother al-Mansur was declared his successor on the battlefield. The deposed Abdullah Mohammed had also fallen in the battle.

Under Al-Mansur the Saadian dynasty knew its golden age. Enriched by the ransoms of wealthy European prisoners taken at Alcacer Quibir, Al-Mansur was able to beautify his capital of Marrakesh, constructing the magnificent Al Badi Palace, the remains of which stand to this day. He was a ruler with imperial ambitions and sought alliances as far afield as England, dispatching envoys to the court of Elizabeth I to seek an alliance against Spain. In 1591 he sent forth an expedition against the gold-rich Songhai Empire of Mali commanded by a Spanish born eunuch named Judar Pasha. This bold enterprise, marching an army of four thousand soldiers and an additional two thousand non-combatants using eight thousand camels to carry their supplies and equipment which included arquebuses and canons on a 135 day crossing of the Sahara, caught the Songhai ruler entirely unprepared. At Tondibi the opposing forces met and the Malian defenders attempted to disrupt the Moroccan lines by sending ten thousand cattle in a stampede towards them. A volley of canon fire sent the stampede back towards the Malian lines and thus their own tactic rebounded upon them. The superior professionalism and firepower of the mostly mercenary Moroccan army carried the day. Reinforcement by a second expedition led to the swift collapse of the Songhai Empire and the occupation of its legendary cities of Gao, Djenne and Timbuktu which the Moroccans would control for the next thirty years before the logistical demands of maintaining such a far flung imperial possession proved too much.

A Nineteenth Century depiction of Timbuktu

A Nineteenth Century depiction of TimbuktuAl Mansur died from the plague in 1603. He was succeeded by two of his sons ruling separately in Marrakesh and Fez and so began the inevitable decline of the Saadian Dynasty as twenty five years of civil war beckoned, at the conclusion of which their empire was left fragmented and largely in the hands of local potentates, the Spanish or the Turks.

Rise of the Saadians

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=jdlKbZ46YYkC&pg=PA211&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Battle of Alcacer Quibir

http://warfarehistorian.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/battle-of-ksar-el-kebir-morocco-1578.html?spref=tw

Expedition to Mali

http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/morco_1591.html

You may also enjoy - Austen Henry Layard - Discoverer of Nineveh

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/austen-henry-layard-discoverer-of.html

Published on August 19, 2013 01:25

August 7, 2013

Enemies at the Gate Part Three – The troubled reign of Leo VI

Leo VI, known as the Wise, ascended to the Byzantine throne in 886 following the suspicious death in a hunting accident of the man who officially at least was recognised as his father, Basil I. Leo himself however, whose relations with Basil had been fraught to say the least, seems to have been in little doubt as to the identity of his true father as he presided over the reburial in Constantinople with much pomp and ceremony of Basil’s murdered predecessor Michael III.

A penitent Leo VI

A penitent Leo VILeo endured a troubled family life, despised by his ‘father’ Basil before the latter’s death and saddled with a pious bore of a wife whom he detested. He found brief happiness when he married his mistress Zoe following his first wife’s death but lost her in childbirth only two years later. Leo then embarked upon a long and bitter dispute with his own church that would have brought a nod of sympathy from Henry VIII as he undertook a third and then a fourth marriage in pursuit of an heir, defying and eventually overthrowing an outraged Patriarch who had railed against the Emperor’s fornication.

International matters were scarcely more edifying. In 894 Leo’s trusted chief minister Stylian Zautses gave mortal offence to the new Bulgar ruler Symeon when he banished Bulgar merchants from Constantinople and forced them into conducting all trade with the empire through the city of Thessalonica. No longer able to move their goods by sea but obliged instead to undertake an arduous overland journey to Thessalonica instead, where they were greeted by increased duties, the Bulgar merchants understandably protested to their king. Receiving no satisfaction from the emperor, Symeon, who was eager for an excuse to do so, embarked on an invasion of Thrace.

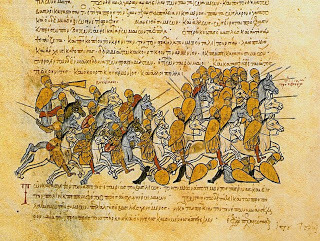

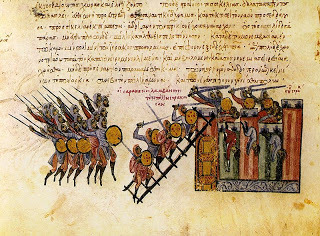

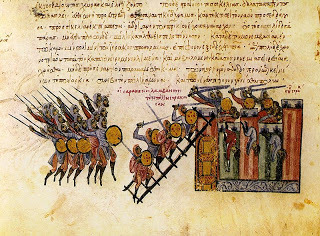

The Bulgar victory at Adrianople

The Bulgar victory at AdrianopleImperial forces were ill prepared. The finest general of the time Nicephorus Phocas was at the time in the east to counter the Arab threat and only inexperienced and poorly led troops were available to face the Bulgars. Outside Adrianople Symeon’s forces inflicted defeat upon the Byzantines, killing both commanders and cutting off the noses of those taken captive and sending them back towards Constantinople as a grizzly message to the emperor.

Leo summoned Phocas and his army from the east to the defence of the capital but also sought to employ cunning diplomacy against Symeon by courting the enemies arrayed on his northern border. An embassy was sent to the Magyars, inviting them to fall upon the undefended Bulgar lands and even promising to provide imperial ships to ferry the rampaging horsemen across the Danube. Leo even warned Symeon of the impending Magyar invasion in the hope of precipitating his withdrawal from Byzantine territory but the Bulgar king did not believe the threat until the Magyars had swarmed across the river .

Returning north, Symeon faced the Magyars at Dobruja where he was defeated and forced to flee, holing up in fortress whilst the Magyars and Byzantines advanced upon his capital Preslav from north and south. The Magyars sold thousands of Bulgar captives to Phocas.

Symeon sued for peace and was able to secure a Byzantine withdrawal from his territories but then was able spring a surprise attack of his own upon the Magyars by appealing to their own northern neighbours, the fearsome Pechenegs to fall upon them from the rear. Symeon now attacked the Magyars and in a savage fight that saw the loss of some twenty thousand of his own troops he nonetheless inflicted such an annihilating defeat upon them that they were driven westwards to seek a new homeland in what is now Hungary.

In 896, with Phocas now dead, Symeon once more launched his forces into Thrace. They met with the Byzantine forces at Bulgarophygon and utterly routed them in a shameful defeat for the Empire. Leo had no choice but return the Bulgar prisoners and restore the trading rights as well as agreeing a payment of tribute to the Bulgars. Under Basil the Bulgars had been turned into a peaceful satellite state of the empire; Christianised and pacified. Now they had humbled their more illustrious neighbours.

Defeat at Bulgarophygon

Defeat at BulgarophygonLeo’s troubles were not at an end. In 904 an Arab fleet under the renegade commander Leo of Tripoli sailed up the Marmara. The imperial fleet set out to meet the threat and succeeded in driving them back. On his return voyage however Leo of Tripoli decided not to go quietly but instead fell upon the city of Thessalonica. A convert to Islam following capture in an Arab raid, Leo pressed home the attack with determination. Having reconnoitred the defences from the sea, the Arabs pressed their attack where a combination of deep water and low walls allowed them to avoid underwater obstacles and land troops who attempted to scale the city walls. They were nevertheless repulsed by the defenders who held the walls with ferocious courage.

Leo now landed his siege equipment and battered away at the walls of Thessalonica which were in a poor state of repair. The defenders returned fire with their own siege engines and again an assault on the walls was repulsed. The Arabs next succeeded in burning down one of the outer gates of the city by pushing carts filled with flammable material up against them and setting them ablaze. The inner defences nevertheless held firm. Finally Leo returned to amphibious assault, lashing ships together to create floating siege towers and assaulting the walls from platforms lashed to the mast tops. This last furious assault ultimately succeeded in capturing a section of wall when the defenders lost heart and fled for their lives and the attackers swarmed into the city.

Leo of Tripoli took some thirty thousand prisoners and captured sixty Byzantine ships which were gleefully towed away. The captives were sold into slavery on Crete. One of their number John Kaminiates, who was later ransomed, wrote an extensive account of the siege which survives to this day.

Leo of Tripoli attacks Thessalonica