C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 22

March 12, 2020

For Love and Money

Like many young women, I read romances by the cartload in high school and college. Not bodice rippers, for the most part, but everything by Georgette Heyer I could get my hands on, as well as Emilie Loring, Barbara Cartland (a real guilty pleasure, those), and more Harlequin romances than I care to count.

Like many young women, I read romances by the cartload in high school and college. Not bodice rippers, for the most part, but everything by Georgette Heyer I could get my hands on, as well as Emilie Loring, Barbara Cartland (a real guilty pleasure, those), and more Harlequin romances than I care to count.In recent years, I’ve rather lost my taste for the classic romance. With rare exceptions, they seem too predictable and, in the case of many historical romances, too disconnected from the moral standards of the time periods they claim to depict. But I still write romance into my novels, because I can’t imagine a story that isn’t enhanced by the love and conflict that characterize an emerging relationship. And the fiction I prefer to read—mostly historical, not least because of the demands of this podcast—almost always includes romantic elements as well.

So, as I wrote last summer, it’s been a great pleasure to discover the thoughtful, well-crafted historical romances penned by Maya Rodale. It was only when I began preparing for this week’s New Books in Historical Fiction interview with her, though, that I also discovered her nonfiction study of romances, which we used to kick off our conversation. So listen to the interview; read her latest Gilded Age Girls Club novel, An Heiress to Remember , when it comes out at the end of this month; and watch for the follow-up post on the Literary Hub, which should go up next week.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

As Maya Rodale notes early in this interview, romance novels tend not to get the same respect as other categories of fiction, historical or otherwise. Here, and in her Dangerous Books for Girls , she argues persuasively that this bad reputation is an attempt by life’s insiders to undermine the central message of most romance novels: that outsiders, too, have the right to love, success, and happiness. But the message is nowhere more evident than in her Gilded Age Girls Club series, in which a small group of wealthy women make it their goal in life to support female-run businesses and their staffs.

In An Heiress to Remember, the heroine, Beatrice Goodwin, suffers from no lack of money; her family has plenty of it—enough to insist that their beautiful daughter wed a duke to bring them prestige in society, even though Beatrice has fallen in love with Wes Dalton, one of her father’s employees. At twenty, Beatrice gives in to her parents’ demands, but sixteen years later, she is back in New York, having scandalously divorced her duke. It is 1895, and wives are not supposed to take that kind of initiative.

Beatrice finds her family situation much changed. The man she loved has gone on to build a wildly popular department store directly opposite her own, and the combination of his desire for revenge and her brother’s mismanagement has placed the family fortune in jeopardy. But Beatrice has no intention of standing by while Dalton buys her father’s cherished store out from under her and destroys it. She sets out to beat Dalton at his own game, because if anyone knows what women want from a department store, she does. And before long, Dalton has to worry that she may succeed in her quest.

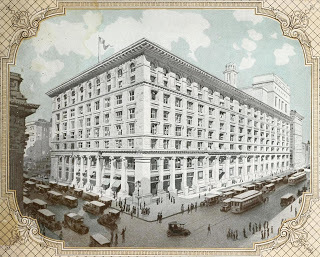

Image: B. Altman’s, one of the department stores anchoring the Ladies’ Mile, New York City, ca. 1915, via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on March 12, 2020 09:05

March 6, 2020

The Fifties Mystique

After almost eight years as host of New Books in Historical Fiction, I’m in the delightful position of receiving more books from publishers and publicists than I can ever hope to cover in my podcast interviews—at least until I retire and can bump up the number to one a week instead of a couple of times a month. Meanwhile, my attempts to sustain regular blog posts require a constant stream of new material. This happy coincidence bears fruit this week in a pair of summaries of books too new even to have made it onto my most recent quarterly Bookshelf post—although now that I think of it, spring is not far away, meaning that the springtime roundup should follow early next month.

Both books came to me from William Morrow, a steady supplier of great historical fiction whose efforts I greatly appreciate. Otherwise, the two novels have little in common except that the main action takes place in 1951–52 and features a quite ordinary woman who finds herself in circumstances she didn’t anticipate, confronting secrets that threaten to undermine her family and her own peace of mind.

Kayte Nunn’s

The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant

came out this past Tuesday, March 3. In 2018, Rachel Parker, a young marine biologist, leaves New Zealand for a research project counting clams on the Scilly Isles, off England’s southwestern coast. When her boat goes down in a storm, she winds up on an almost deserted island where she discovers a cache of unsent letters written more than sixty years before. But who was the writer, and who the unknowing recipient?

Kayte Nunn’s

The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant

came out this past Tuesday, March 3. In 2018, Rachel Parker, a young marine biologist, leaves New Zealand for a research project counting clams on the Scilly Isles, off England’s southwestern coast. When her boat goes down in a storm, she winds up on an almost deserted island where she discovers a cache of unsent letters written more than sixty years before. But who was the writer, and who the unknowing recipient?

The novel shifts back and forth between Rachel’s academic and romantic journey and the attempts by a young Londoner named Eve to record the memoirs of her grandmother, one of the first female mountaineers. But the heart of the story is Esther Durrant, first seen traveling with her husband to the Scilly Isles in 1951, where she wakes up the next morning and discovers that her husband has left her in the care of his friend, an innovative psychiatrist who treats a handful of patients—mostly male war veterans—in what is, to all intents and purposes, a mental institution on the island. Esther suffers from depression caused by the loss of her infant son to SIDS, a condition not yet named and recognized in 1951, and the doctor believes that life on the island may help her come to terms with her loss.

Esther, Rachel, and the people they encounter are richly imagined, complex characters, and the atmosphere of the isolated and largely depopulated islands that bring both Esther and Rachel, in a sense, back into the world is both pervasive and haunting. Also visible are the long-term effects of World War II, six years ended by the time the book opens, on the men who fought. The hidden secrets, where Eve and her grandmother fit in, and the identity of the letter writer you will have to find out for yourselves.

In some ways, Gretchen Berg’s debut novel,

The Operator

, which is due out next week but already available to preorder, couldn’t be more different. Here the war forms at most part of the backdrop, which matches the vastly different experience of war in Europe and the American Midwest.

In some ways, Gretchen Berg’s debut novel,

The Operator

, which is due out next week but already available to preorder, couldn’t be more different. Here the war forms at most part of the backdrop, which matches the vastly different experience of war in Europe and the American Midwest.

Set in Ohio, The Operator begins in 1952 but moves backward and forward in time to include the childhood and early womanhood of its heroine, Vivian Dalton. Unlike Esther Durrant, who has a college education and lives a relatively affluent life in London, Vivian has to leave school in her early teens to help support her family through the Great Depression. She lands a job as a telephone operator, an occupation that from the standpoint of 2020 seems as archaic as that of coal stoker for a steam-powered locomotive.

Yet at the risk of dating myself, I can remember the first in-house telephone my parents owned when I was a child. It had no rotary dial and certainly no keypad. It was merely a handset, which you picked up. When the operator answered, you gave the number you were calling—Oxford 402, say—and the operator made the connection, just as Vivian does in this novel. Not surprisingly, perhaps, operators could listen in on the calls, although they were supposed to do no such thing.

And that’s exactly what Vivian is doing when she hears gossip that personally affects her family. And although the secret, when it’s finally revealed, is itself a relic of the 1950s which it’s hard to imagine having quite the same impact in our scandal-ridden and “everything out in the open” time, like all hidden truths it has consequences that no one could have predicted when the events first happened.

Here too the writing is vivid and engaging, Vivian and her trials and triumphs (not least with her older sister, Vera) beautifully realized and sympathetic, and this glimpse of a time that is irretrievably gone yet still with us in the form of older relatives and friends bittersweet.

As a professional woman, I can’t say that I’ve ever dreamed of returning to the 1950s, and some of the incidents in these novels remind me of why. But as virtual journeys to an almost forgotten and perhaps unmourned past, these books offer excellent reads.

Both books came to me from William Morrow, a steady supplier of great historical fiction whose efforts I greatly appreciate. Otherwise, the two novels have little in common except that the main action takes place in 1951–52 and features a quite ordinary woman who finds herself in circumstances she didn’t anticipate, confronting secrets that threaten to undermine her family and her own peace of mind.

Kayte Nunn’s

The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant

came out this past Tuesday, March 3. In 2018, Rachel Parker, a young marine biologist, leaves New Zealand for a research project counting clams on the Scilly Isles, off England’s southwestern coast. When her boat goes down in a storm, she winds up on an almost deserted island where she discovers a cache of unsent letters written more than sixty years before. But who was the writer, and who the unknowing recipient?

Kayte Nunn’s

The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant

came out this past Tuesday, March 3. In 2018, Rachel Parker, a young marine biologist, leaves New Zealand for a research project counting clams on the Scilly Isles, off England’s southwestern coast. When her boat goes down in a storm, she winds up on an almost deserted island where she discovers a cache of unsent letters written more than sixty years before. But who was the writer, and who the unknowing recipient? The novel shifts back and forth between Rachel’s academic and romantic journey and the attempts by a young Londoner named Eve to record the memoirs of her grandmother, one of the first female mountaineers. But the heart of the story is Esther Durrant, first seen traveling with her husband to the Scilly Isles in 1951, where she wakes up the next morning and discovers that her husband has left her in the care of his friend, an innovative psychiatrist who treats a handful of patients—mostly male war veterans—in what is, to all intents and purposes, a mental institution on the island. Esther suffers from depression caused by the loss of her infant son to SIDS, a condition not yet named and recognized in 1951, and the doctor believes that life on the island may help her come to terms with her loss.

Esther, Rachel, and the people they encounter are richly imagined, complex characters, and the atmosphere of the isolated and largely depopulated islands that bring both Esther and Rachel, in a sense, back into the world is both pervasive and haunting. Also visible are the long-term effects of World War II, six years ended by the time the book opens, on the men who fought. The hidden secrets, where Eve and her grandmother fit in, and the identity of the letter writer you will have to find out for yourselves.

In some ways, Gretchen Berg’s debut novel,

The Operator

, which is due out next week but already available to preorder, couldn’t be more different. Here the war forms at most part of the backdrop, which matches the vastly different experience of war in Europe and the American Midwest.

In some ways, Gretchen Berg’s debut novel,

The Operator

, which is due out next week but already available to preorder, couldn’t be more different. Here the war forms at most part of the backdrop, which matches the vastly different experience of war in Europe and the American Midwest.Set in Ohio, The Operator begins in 1952 but moves backward and forward in time to include the childhood and early womanhood of its heroine, Vivian Dalton. Unlike Esther Durrant, who has a college education and lives a relatively affluent life in London, Vivian has to leave school in her early teens to help support her family through the Great Depression. She lands a job as a telephone operator, an occupation that from the standpoint of 2020 seems as archaic as that of coal stoker for a steam-powered locomotive.

Yet at the risk of dating myself, I can remember the first in-house telephone my parents owned when I was a child. It had no rotary dial and certainly no keypad. It was merely a handset, which you picked up. When the operator answered, you gave the number you were calling—Oxford 402, say—and the operator made the connection, just as Vivian does in this novel. Not surprisingly, perhaps, operators could listen in on the calls, although they were supposed to do no such thing.

And that’s exactly what Vivian is doing when she hears gossip that personally affects her family. And although the secret, when it’s finally revealed, is itself a relic of the 1950s which it’s hard to imagine having quite the same impact in our scandal-ridden and “everything out in the open” time, like all hidden truths it has consequences that no one could have predicted when the events first happened.

Here too the writing is vivid and engaging, Vivian and her trials and triumphs (not least with her older sister, Vera) beautifully realized and sympathetic, and this glimpse of a time that is irretrievably gone yet still with us in the form of older relatives and friends bittersweet.

As a professional woman, I can’t say that I’ve ever dreamed of returning to the 1950s, and some of the incidents in these novels remind me of why. But as virtual journeys to an almost forgotten and perhaps unmourned past, these books offer excellent reads.

Published on March 06, 2020 06:00

February 28, 2020

Elemental Magic

The line between historical fiction and historical fantasy at times seems rather slim. I consider my own novels straight historical fiction—admittedly with a large dollop of romance, but the romance is never the whole point of the story. Yet the world of the sixteenth century, in any part of the world, was saturated with religion and spiritual forces and flat-out magic.

My characters believe in all of it, none more so than Grusha in Song of the Shaman, who doesn’t quite subscribe to the idea that she actually ventures into realms beyond our own but who nonetheless behaves in every respect as if otherworldly spirits exist and she can contact them. The people she interacts with believe it too; their faith, more than anything else, is the source of her healing power.

Let’s move now to the wholly fictional world of Gabrielle Mathieu’s new Berona’s Quest trilogy, which forms the subject of my most recent interview on the New Books Network. Gabrielle is, in addition to a fellow member of Five Directions Press, the host of New Books in Fantasy and Adventure. So her channel is the main location of her interview, but it is cross-posted to mine.

And that seems appropriate. It’s true that at no time in our world have we seen a vicious Water Demon, mother of all life on earth but mad as hell after spending six hundred years in a cage under the ocean after her last attempt to wipe out her human creations. Nor do we have to flee the destructive (or are they constructive?) efforts of massive ogre-like creatures called Elementals. We are like the residents of Mathieu’s Vendrisi, scholars and scientists and traders.

Yet the land of Berona’s birth, Trea, has definite parallels to medieval Europe, although its priest cult serves a goddess rather than a god. Trea, the magical heartland, hosts scattered communities of farmers and vineyard keepers, lords and ladies, merchants and townsfolk. They all use swords and plowshares, keep their women under wraps and their men in positions of authority, and dole out education, privileges, and luxuries according to accidents of birth. The politics are as vicious and self-serving, the capacity for treachery as great, the pleasures of love as delicious, and the pains of loss as devastating as in the world we know—despite the presence of an occasional dwarf, magician, or elfin Elder.

So even if you like your fiction without a dose of spells and sorcery, you may well enjoy Girl of Fire , the first novel starring Berona and her comrades. Or just listen to the interview, summarized below.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Fantasy and Adventure.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Fantasy and Adventure.In the fantasy medieval land of Trea—a conservative society that despite its worship of the goddess Amur respects her human daughters only as wives and mothers—eighteen-year-old Berona has limited expectations for her future. Securing a handsome husband who will win her heart and teach her to dance seems like enough of a challenge, given that her father keeps presenting her with candidates who can neither appeal to nor appreciate her fiery nature. But Berona remains hopeful until a nighttime encounter at the stream that runs near her house brings her face-to-face with humanity’s ancient enemy, the Water Demon, desperate for revenge after six hundred years locked deep in the world’s oceans.

The Demon threatens Berona and her family, and to protect her parents and younger sister, Berona accepts help from a magician, member of an outlawed sect with a philosophy of life very different from that of the Intercessors of Trea. The magician has been searching for the Girl of Fire, who according to ancient prophecy is the only person who can defeat the Water Demon, and he becomes convinced that Berona is the one he seeks.

But Berona is untrained, and the Demon already on the move. As the Elemental forces of Nature awaken and treachery splits those committed to help her, Berona struggles to reconcile her own essential strengths, the demands placed on her, and the lessons she must master against a foe who destroys from within, by manipulating her victims’ deepest fears and appealing to their hidden desires.

Gabrielle Mathieu, the author of the Falcon Trilogy and host of New Books in Fantasy and Adventure, kicks off her new series, Berona’s Quest, with Girl of Fire, a deeply researched and endlessly inventive exploration of a world in which disrespecting the environment can, quite literally, get you killed.

Published on February 28, 2020 06:00

February 21, 2020

Broken Dreams

Climate change, colonialism, imperialism, industrialization: these intertwined issues have deep roots extending back into the eighteenth century, if not longer. One gift of fiction, in my view, is the author’s ability to take these vast sweeping trends—the results of which are often disputed or poorly understood—and bring them down to the individual level where we as humans naturally live. This is part of what Joan Schweighardt and I discuss in my most recent interview for New Books in Historical Fiction.

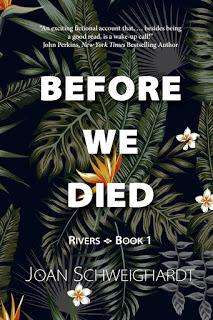

Climate change, colonialism, imperialism, industrialization: these intertwined issues have deep roots extending back into the eighteenth century, if not longer. One gift of fiction, in my view, is the author’s ability to take these vast sweeping trends—the results of which are often disputed or poorly understood—and bring them down to the individual level where we as humans naturally live. This is part of what Joan Schweighardt and I discuss in my most recent interview for New Books in Historical Fiction.In the first book in this trilogy, Before We Died , Joan approaches the story of the Amazon rubber-tapping industry and its devastating effects on the local population and ecology by imagining two Irish brothers, Jack and Baxter Hopper, who take ship from their home town of Hoboken, NJ, in the belief they will make their fortune in a year and return home.

Life doesn’t quite work out as they expect. In a novel, that’s hardly a surprise, but the specifics of what they encounter are compelling. In one scene after another, Jack and Baxter experience the damage and dangers firsthand. And their adventures pull us into a world that headlines about the rain forest burning don’t even begin to capture. Through our empathy for Jack and Baxter, we see the piranha in the waters; feel their dread of a tarantula in a hammock; experience their awe at the jaguar emerging from the jungle, lit only by the moon, or their despair as they realize they may not, in the end, make it home.

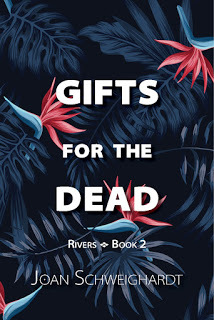

The story continues in Gifts for the Dead , the main topic of our interview. Here many of the incidents reflected in the lives of Jack Hopper and Nora Sweeney, the woman once engaged to Baxter, come from the history books: World War I, the women’s suffrage movement, the Spanish flu. But here, too, the story eventually finds it way back to the Amazon River and the ongoing destruction of the natural world.

To find out more about Gifts for the Dead, listen to the interview or read the rest of this post, which comes from New Books in Historical Fiction:

Last summer, massive fires in the Amazon rain forest provoked environmental concerns around the world. But the history of exploitation—of the natural world of the rain forest and the people living in it—goes back at least to the rubber boom of the early twentieth century. This setting forms the backdrop for Joan Schweighardt’s compelling and well-written Rivers trilogy, which starts with Before We Died and continues with Gifts for the Dead nd the forthcoming River Aria.

As Gifts for the Dead opens, it is 1911 and the heroine, Nora Sweeney, is waiting for bad news in Hoboken, NJ. A fortuneteller has prophesied that any day two dock workers will appear on the doorstep to report that both the man Nora loves, Baxter Hopper, and his brother, Jack, have died during their work as rubber tappers in Brazil. But when the dock workers arrive, it’s to deliver the comatose body of Jack, on the brink of death.

Nora and Jack’s mother, Maggie, nurse him back to health, and life goes on. With help from Maggie, Nora and Jack restore the family that was broken when the brothers left on their grand adventure. Through World War I, the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, and the Roaring Twenties, the trio perseveres. Everyone assumes Baxter died in the rain forest. Only Jack knows that his brother’s fate is less certain than he’s given the women reason to believe. And that one day he must go and find out the truth.

Published on February 21, 2020 06:00

February 14, 2020

Interview with Philip Cioffari

And here, just in time for Valentine’s Day, we have a post about the joys and sorrows of first love.

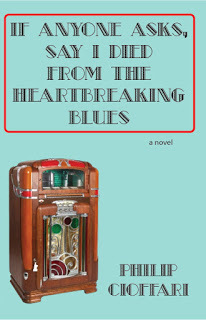

And here, just in time for Valentine’s Day, we have a post about the joys and sorrows of first love.When Philip Cioffari’s publicist first sent me an advance copy of his latest novel, If Anyone Asks, Say I Died from the Heartbreaking Blues , the title caught my attention immediately. Who could ignore such a catchy title?

Learning that the book begins in the Bronx in 1960—when I was already on the planet—was a little alarming, simply because I don’t like to think about my life as historical fiction. But nonetheless I dove into the story of eighteen-year-old Joey Hunter, his hopes, his friends, and his family.

To find out more about Philip Cioffari’s latest book and his plans for it, just read on.

That’s a wonderful title. Where does it come from, and what does it tell us about the novel?

The title comes from an African-American folktale about two mythical lovers, Betty and Dupree. Betty wants a diamond engagement ring, so Dupree, who is very much in love with her and has no money, goes into town and steals one, in the process shooting the store clerk. At his sentencing, he explains he was done in by the heartbreaking blues. In my novel, I wanted the title to reflect the young main character’s struggle to find true love. I wanted it to convey, in a mostly comic and ironic way, the blues he suffers on that journey, as well as the more general and inevitable blues of adolescence.

The Bronx in the 1960s: what made you want to set a story there?

For one thing, it is a period I know well, having lived through it. More importantly, though, I think of the year 1960 as the beginning of a decade that served as a turning point in American culture. The postwar cultural mores were beginning to slip away, being replaced by newer customs and more progressive values. The conformity of the 50s was giving way to a more personalized, individualistic kind of freedom. Especially for the young, it was a time of bright hope and anticipation that one’s destiny was less a prefabricated mold and more a malleable substance that could be shaped according to one’s need.

Tell us about your protagonist, Joey Hunter, better known as Hunt. Where is he in his life at the opening of the novel?

Hunt, on this his eighteenth birthday and senior prom night, is on the cusp of manhood. He is experiencing for the first time what he thinks of as love. We would call it infatuation, but he doesn’t yet know the difference. He also longs for independence. The one thing he asks for on his birthday, and is given it, is the right to stay out all night. This night he takes important steps in becoming a man. He moves from infatuation to a deeper sense of what love really is. He understands the ways, despite his own struggles, he can be a support and comfort to others.

And how would you describe his personality?

His personality is basically upbeat and optimistic, though he suffers through bouts of what he calls the Deep Blues—the result of his insecurities and uncertainties—that cause him to feel disconnected and alone.

Hunt, when we meet him, is anticipating his first date with a girl named Debby Ann Murphy. What can you tell us about her—particularly in terms of how Hunt sees her and what she means to him?

He’s infatuated with her: her looks, her clothes, her blossoming womanhood. The reality is, though, that she’s absolutely the wrong mate for him. They share none of the same values. He wants to be a writer and thinker, and she has little tolerance for school or things intellectual. He has a creative mind and wants to live, in all ways, an adventurous life, while she sticks to the basics. She sees her life as already planned out for her: marriage, pregnancy, motherhood. None of these things deters him, however. All love might be blind, but certainly first love is. He pursues her till she shuts the door.

Hunt also has two pals, Augie and Johnnie Jay. Who are they, and how do they help him handle the various mishaps that he endures in the course of this story?

Johnnie Jay is the best friend of his teenage years. They share the same love of adventure, the same intellectual pursuits, the same desire for girls who, in one way or another, are beyond their reach. But Johnnie Jay’s more carefree approach to life and love lightens Hunt’s more serious personality. If a girl refuses Hunt’s invitation to dance, he’s crushed; Johnnie Jay, on the other hand, takes a “no” as a challenge to try harder. They complement one another, a fact that has made them such close friends.

Ten year-old Augie is Hunt’s sidekick. He is the only African-American kid in the neighborhood, the smartest student in the fifth grade, who in his free time is either playing his harmonica or reading his pocket dictionary. Because Augie’s parents leave him mostly on his own, Hunt “adopts” him. Augie serves, in some ways, as a substitute for the younger brother Hunt has lost. He is a cunning, street-smart boy who helps Hunt survive a number of difficult situations, some funny, some quite serious.

You already have one independent film to your credit, Love in the Age of Dion. Would you consider turning this book into a film? Why or why not?

I would certainly consider doing another movie, and I’d love to do this one. The main obstacle, of course, is the cost of making a film. It’s one thing to have a character perform an action on the page—it merely takes a few sentences to describe. To render that same action in real life on film, takes considerable effort and financial resources. So I guess the short answer is that it’s more economical to sit at my desk and write novels and stories.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Philip Cioffari grew up in the Bronx. He is the author of the novels Catholic Boys, Dark Road, Dead End, Jesusville, and The Bronx Kill, as well as the story collection A History of Things Lost or Broken, which won the Tartt First Fiction Prize and the D. H. Lawrence Award. His stories have appeared widely in anthologies, literary journals, and commercial magazines. He wrote and directed the independent feature film Love in the Age of Dion, which won a number of film festival awards, including Best Picture at the Long Island International Film Expo and Best Director at the NY Film and Video Festival. He is professor of English at William Paterson University in New Jersey. Find him online at http://www.philipcioffari.com/.

Published on February 14, 2020 06:00

February 7, 2020

Divided Loyalties

A year ago, I discovered the detective Ian Rutledge and his mother/son duo of creators, who publish under the name Charles Todd. You can find that first post here on this blog, “The Black Ascot,” and more information about Charles Todd and the fictional context of Rutledge’s world in my New Books in Historical Fiction interview from last year.

A year ago, I discovered the detective Ian Rutledge and his mother/son duo of creators, who publish under the name Charles Todd. You can find that first post here on this blog, “The Black Ascot,” and more information about Charles Todd and the fictional context of Rutledge’s world in my New Books in Historical Fiction interview from last year. In short, I was hooked, and for an avid reader like myself few things are more fun than discovering a series that already has twenty books in it—especially when the mysteries are as complex yet ultimately satisfying, the writing as good, and the characters as fascinating and full of human frailty as these.

I wanted to dive in right away, but other interviews and books demanded my time, so it wasn’t until a lucky sale brought the first two Rutledge novels to my e-reader, I found another readily available on Overdrive, and the latest landed in my mailbox as an advance review copy that I was able to follow up. So my main goal here is to report on the latest book, A Divided Loyalty , which came out just this last Tuesday (February 4, 2020). But to me the development of the series is also interesting, and I’ll mention a few words about that in passing.

A Divided Loyalty is clearly the work of an experienced and accomplished team. As someone just beginning a collaboration with another author, I’m in awe at the sophisticated communication that must drive the planning and execution of thirty-five or more novels. In this one, the suspicious death that incites the plot is that of a young woman discovered at Avebury—then (1921) considered a kind of lesser Stonehenge without the popularity of the better-known site.

The local police want nothing to do with the case, and Scotland Yard is called in. But the first detective sent to handle the investigation is not Rutledge, and he insists that he can’t find any evidence that points to a killer or even an identification of the victim. The case rests, but murder cases never close, and in due course the chief superintendent sends Rutledge to revisit the scene of the crime and review the earlier investigation—never a comfortable position to occupy when the man being reviewed stands higher in the department than the one doing the reviewing.

It’s a delightful puzzle, in itself a reason to read this compelling series. But as always in Rutledge’s world there are wheels within wheels: office politics, conflict caused by differences in class and education, city/village confrontations, and always the lingering effects of the Great War—on society as a whole and on its individual members, including Rutledge himself.

This last element—the scars that Rutledge carries from his military service, the sacrifices he made and the decisions he regrets having to make—carries throughout the series and gives it a special edge. It’s already visible in the first book, A Test of Wills, which is itself a fine mystery story and character study although still maturing compared to the later entries in the series. And it pushes the action forward here as well. Or, as Hamish—the inescapable voice in Rutledge’s shell-shocked mind—might put it: “Ye just might learn something from yon policeman.”

And don’t miss my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Joan Schweighardt about her novels Before We Died and Gifts for the Dead , set along the Amazon and Hudson rivers during the first third of the twentieth century. I’ll post about the books in more depth in a couple of weeks.

And if you’d like to learn more about me and how I came to write the fiction I do, check out this interview on Occhi Magazine. Wouldn't you love to see The Golden Lynx turned into a film? I would! And while it may never happen, feel free to leave casting suggestions in the comments. One day, I’ll reveal my picks for Nasan and Daniil.

Published on February 07, 2020 06:00

January 31, 2020

Bits and Bobs

In general, I juggle a lot of tasks. I have a lot of energy, I enjoy being occupied, and people who know me often remark on how much I get done in a day—or a week. Most of the time, too, I make it work, balancing the editing and the writing and the podcast and the various tasks I perform for Five Directions Press. I’ve learned when to say “no,” and I do.

In general, I juggle a lot of tasks. I have a lot of energy, I enjoy being occupied, and people who know me often remark on how much I get done in a day—or a week. Most of the time, too, I make it work, balancing the editing and the writing and the podcast and the various tasks I perform for Five Directions Press. I’ve learned when to say “no,” and I do.But I’m not superhuman, and sometimes the pretty juggling pins crash to the floor. This was one of those weeks. So instead of the usual themed blog post, I’m offering some hints of what to expect in the weeks to come.

Interviews: I talked with Gabrielle Mathieu about her new YA fantasy novel, Girl of Fire, just before the New Year. That interview will post on her New Books Network channel, possibly with a cross-post to mine, in a few weeks. Meanwhile, I talked with Joan Schweighardt yesterday about her latest historical fiction trilogy, Rivers— Before We Died and Gifts for the Dead are out, with River Aria to follow sometime this year. I expect to see that interview on New Books in Historical Fiction next week or the week after.

Reading: I’ve been expanding my acquaintance with the fictional detective Ian Rutledge, the creation of Charles Todd. I made Ian’s acquaintance in last year’s The Black Ascot and interviewed the author team that created him this past fall (about another series of theirs). Since then I’ve read the first book in the Rutledge series, purchased the second, and am currently reading another Rutledge novel, The Confession, on Overdrive, courtesy of my local public library. Next week I’ll be discussing Ian’s latest adventure, A Divided Loyalty , here on this blog.

Blog: In addition to the Divided Loyalty post, you can expect to see a written Q&A with the English professor, film director, and novelist Philip Cioffari on Valentine’s Day, followed by individual posts on the Schweighardt and Mathieu interviews. That should take us into March.

Writing: This, of course, is the fun part, and although I have to restrict it mostly to weekends, I’ve actually made great progress. Song of the Shaman is out (as is Song of the Siren , if you missed that last year), and the third book in that series, Song of the Sisters , is essentially done. I’m revising the third draft chapter by chapter with comments from my writing group, but it’s a complete novel with a story and character arcs. I’m starting to think about Songs 4 (Song of the Sinner—Solomonida’s story), but in the meantime P.K. Adams and I have written the first half of the rough draft of our Tudors meet Romanov ancestors murder mystery, tentatively titled These Barbarous Coasts. We’re keeping the details under wraps for now, but stay tuned.

That’s it on the novel-writing front. The rest is family and exercise and work, not to mention boring tasks like housework and enjoyable tasks like putting food on the table. But those, as they say, are a story for another day—or, in this case, another venue.

Published on January 31, 2020 07:06

January 24, 2020

Bookshelf, Winter 2020

Three months have passed since my last Bookshelf post, and the book deluge continues unabated. Here are a few selections from the huge pile that occupies various parts of my house (not counting my e-reader). A departing neighbor even left another bookcase for me, which I filled within twenty minutes. But at least the main bookcases in the hall are now only double-deep, not triple....

Michelle Cox, A Veil Removed (She Writes Press, 2019)

Back in 2016, I read the first two in this series about a young woman in 1930s Chicago who meets and eventually falls in love with a member of the local police force while she’s dodging criminals and dancing at a nightclub—a job that keeps her family in food but would scandalize them if they ever realized where she was getting the money. Henrietta and Inspector Howard have come a long way since then, and I’m looking forward to reading this fourth book. The fifth, A Child Lost, is due out in April, at which point I plan to interview the author again for New Books in Historical Fiction.

You can find my earlier interview with Michelle Cox on the New Books Network.

H. G. Parry, The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

(Redhook, 2020)

I’m just about to start this one, which I discovered through another New Books Network interview, this one conducted by Rob Wolf for New Books in Science Fiction and cross-listed on the Literary Hub, which is where I found it.

As for why I’m reading it, well, any book where literary characters can escape into the real world and interact with the likes of you and me is guaranteed to get my attention. I loved the Thursday Next novels by Jason Fforde; I created a virtual reality game where modern grad students channeled characters from a classic novel in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel; this one’s a natural fit for me.

Maya Rodale, An Heiress to Remember (Avon, 2020)

I mentioned in a previous post, “Summer Romance,” being pleasantly surprised by the second in Maya Rodale’s Gilded Age Girls Club romances, Some Like It Scandalous, because it had such a fresh take and well-developed characters with real problems to which they produced intelligent responses. So I asked to interview her when the next book comes out, and this is it. I also plan to read her Duchess by Design (Gilded Age Girls Club 1) before talking to her at the end of February. Stay tuned for more information about that.

Lara Prescott, The Secrets We Kept (Knopf, 2019)

This one I discovered through the author’s interview with Scott Simon, a favorite of mine, on NPR. Despite several efforts, an interview didn’t come off for various reasons (timing, the racket on my deck while it was under repair, timing again). But Knopf did send me the book, and I have been enjoying reading about the early days of the CIA and its plans to subvert Soviet communism by publishing and distributing Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago, which ultimately won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

That award was political too, but much as the politics fascinates me, what’s even more interesting is the portrayal of women trying to make their way and find their place in what is still largely a man’s world. In particular, the nascent love affair between Irina, a naturalized Russian raised in the United States, and Sally Forrester, a former OSS operative, is an interesting twist to an already fascinating story.

Michelle Cox, A Veil Removed (She Writes Press, 2019)

Back in 2016, I read the first two in this series about a young woman in 1930s Chicago who meets and eventually falls in love with a member of the local police force while she’s dodging criminals and dancing at a nightclub—a job that keeps her family in food but would scandalize them if they ever realized where she was getting the money. Henrietta and Inspector Howard have come a long way since then, and I’m looking forward to reading this fourth book. The fifth, A Child Lost, is due out in April, at which point I plan to interview the author again for New Books in Historical Fiction.

You can find my earlier interview with Michelle Cox on the New Books Network.

H. G. Parry, The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

(Redhook, 2020)

I’m just about to start this one, which I discovered through another New Books Network interview, this one conducted by Rob Wolf for New Books in Science Fiction and cross-listed on the Literary Hub, which is where I found it.

As for why I’m reading it, well, any book where literary characters can escape into the real world and interact with the likes of you and me is guaranteed to get my attention. I loved the Thursday Next novels by Jason Fforde; I created a virtual reality game where modern grad students channeled characters from a classic novel in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel; this one’s a natural fit for me.

Maya Rodale, An Heiress to Remember (Avon, 2020)

I mentioned in a previous post, “Summer Romance,” being pleasantly surprised by the second in Maya Rodale’s Gilded Age Girls Club romances, Some Like It Scandalous, because it had such a fresh take and well-developed characters with real problems to which they produced intelligent responses. So I asked to interview her when the next book comes out, and this is it. I also plan to read her Duchess by Design (Gilded Age Girls Club 1) before talking to her at the end of February. Stay tuned for more information about that.

Lara Prescott, The Secrets We Kept (Knopf, 2019)

This one I discovered through the author’s interview with Scott Simon, a favorite of mine, on NPR. Despite several efforts, an interview didn’t come off for various reasons (timing, the racket on my deck while it was under repair, timing again). But Knopf did send me the book, and I have been enjoying reading about the early days of the CIA and its plans to subvert Soviet communism by publishing and distributing Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago, which ultimately won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

That award was political too, but much as the politics fascinates me, what’s even more interesting is the portrayal of women trying to make their way and find their place in what is still largely a man’s world. In particular, the nascent love affair between Irina, a naturalized Russian raised in the United States, and Sally Forrester, a former OSS operative, is an interesting twist to an already fascinating story.

Published on January 24, 2020 06:00

January 17, 2020

Love and Magic on the Steppe

It’s always tremendous fun to release a new novel. The blood and angst that went into creating and revising the story washes out in production, leaving a finished text that looks like any other printed book. One by a bestselling author, say, or a prizewinner. (We can dream, right?) Except that it isn’t by someone else. It’s one’s own work, sent out like a beloved child to take its chances in the big, wide world.

It’s always tremendous fun to release a new novel. The blood and angst that went into creating and revising the story washes out in production, leaving a finished text that looks like any other printed book. One by a bestselling author, say, or a prizewinner. (We can dream, right?) Except that it isn’t by someone else. It’s one’s own work, sent out like a beloved child to take its chances in the big, wide world. And the thrill never gets old. The thrill of holding a physical book in your hand and knowing that you wrote it, especially. It’s one reason I hope print books never go away—at least during my lifetime. Seeing a book on an e-reader or tablet is cool, too, but nothing like the joy of hefting a novel in one’s hand, flipping through the pages, admiring the crisp text and vivid cover, the carefully chosen type ornaments and fonts—then placing it on a shelf next to all the other books.

Tuesday’s release of Song of the Shaman is the tenth time I’ve had that pleasure, not counting the second editions and the box sets—fifteen books or collections all told. In some ways, this novel is special: it took a long time to connect with the heroine, Grusha, despite having known her since I typed the first words to The Golden Lynx back in 2008. Finding her character eight years after her original appearance in a major secondary role, even an antagonist (although far from the main one), and her conflict in her new role as the shaman of Ogodai’s Tatar horde took time and multiple rewrites and rethinks. But here she is at last, and I hope her search for happiness, for herself and her young son, will pull you in and make you want to spend a few hours or days accompanying her on her journey.

But don’t take my word for it. Terry Gamble, author of The Eulogist and other novels, puts it so nicely in her endorsement on the back of the book: “A vividly told tale full of magic and mysticism, passion and betrayal. The story of Grusha will grab you by the heart and throat as you travel through the medieval world of Russia and the steppe.” You can find out more about Terry’s wonderful books from her interview at New Books in Historical Fiction.

So, may you enjoy the excerpt below and the novel itself. While you read, I’ll be rereading and revising Song of the Sisters so I can revel in the excitement of publication again this time next year.

And here is an excerpt from chapter 1 of Song of the Shaman .

East of the Don, June 1542

Smoke—stinging, acrid, redolent with sage and the heavy odor of dried dung—filled my nostrils. Flakes of ash floated before my eyes, and I coughed as I reached for my drum. All around me, the tent rocked with the pounding rhythm of an instrument not my own, held in hands more experienced than mine, summoning me to the dance. Suzukei—the shaman of this camp, my teacher—whispered to the spirits of the hearth fire, the ancestors of the horde.

Squinting, I settled the plaits over my face to remind the snake spirits, guardians of wisdom, that they had chosen me, too, to serve them as a journeyer among the realms above and below. When I’d hidden my features, I lifted the rimmed circle, large enough to conceal my torso from waist to shoulder. The familiar heft of the drum, the smooth wood clapper in my other hand, the steady bam-bam-bam-bam as I beat the tanned hide—these things drew me out of myself despite the blistering smoke. The rhythm of my strokes, regular as the beat of my own heart, worked its way into my body, resonating in my chest and pulling me away from the present, into the places that lie beyond the middle lands of earth and water.

Against the crackle of the fire, each upward leap of the flames releasing another swarm of ash flakes, I heard the steady croon of Suzukei’s voice. Moving to the outer rim of the tent, I joined her song, matching her tone as best I could, adding the stamp of my own felt-clad feet. Strings of beads and shells, interspersed with metal shapes etched with sacred symbols, hung from the drum’s rim, adding sounds soft and sharp. I imagined them whispering my name to the listening spirits—Gru-sha, Gru-sha, Gru-sha. I loved the shushing of those beads and shells.

As Suzukei and I danced around each other, I watched her for clues. I couldn’t see her face, because like me she had concealed it behind several dozen plaits—black tinged with gray in her case, light brown in mine. Although half a head shorter than I, she appeared taller, the result of the red felt circle stitched with beaded eyes, nose, and mouth tied around her head and extended by a set of plumes as long as my forearm. Her leather robe, which fell loose from her shoulders, added to the sense of her being larger than life.

“O ancestors,” she called to the spirits of the hearth fire. “O grandmothers, save this child.”

“O grandmothers,” I echoed. “Return his soul to his body. Make him well.” Bam-bam-bam-bam, bam-bam-bam-bam—I punctuated each word with a drumbeat. Suzukei nodded her approval.

In response to a second nod, I redirected my dance in an inward spiral, aiming for a spot closer to the fire, beating my drum with every step and adding my prayers to Suzukei’s. She had charged me with monitoring the condition of our patient, the three-year-old Sibai Sultan—second son of Ogodai Khan, ruler of our horde. The child lay sick unto death on a pile of felts next to the rough stones that contained the fire, motionless except for the occasional sobbing breath and croaking cough. As I moved in, she spiraled out, as if we were two puppets pulled by the same set of strings.

“Grandmothers—bam—come to us—bam—see the child—bam-bam—your own descendant—bam-bam—save his life—bam-bam-bam—so that he can grow strong—bam-bam—and one day sire children to continue your line.” Bam-bam-bam-bam. I spoke to the drum as much as the ancestors, and the drum spoke to me, a wordless conversation.

https://www.fivedirectionspress.com/song-of-the-shaman

Published on January 17, 2020 06:00

January 10, 2020

Sisters, Alone and Together

What would you do to reunite with a beloved sister? Very few of us—encountering the choice that faces Effie Tildon in The Girls with No Names, released this past Tuesday—would go to the lengths Effie does. As the book’s author, Serena Burdick, explains in my latest

But Effie’s choice has dire consequences. The child of a well-off Gilded Age family, Effie comes up with a plan to secure her own commitment to New York City’s House of Mercy, a home for wayward girls and women. She does this because she’s been raised all her life with the bogeyman-type threat that bad behavior will lead to her parents’ sending her to the home. Lively, outgoing, rebellious Luella has often been the target of such efforts at verbal “correction.” So when Luella disappears not long after a blazing row with her father, what could be more logical than Effie’s belief that Dad has sent his disobedient daughter to the House of Mercy?

Furthermore, Effie suffers from a heart defect. No one knows when she will die, but since birth she’s been living, in effect, on borrowed time. The chances that she will survive to adulthood have always been poor, and her frequent “fits” of breathlessness constrict her actions. In the House of Mercy, however, hard work and harsh punishments are a way of life. The older girls enforce the rules every bit as savagely as the nuns who run the penitential laundry that is the central element in the House of Mercy’s financial success. And two of those older girls decide that Effie just might be their key to escape.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Effie Tildon loves her older sister, Luella. Sixteen to Effie’s thirteen, Luella has long taken the leading role in deciding what the two sisters do, even when it leads them in directions their parents would not approve of. Those three extra years are one reason that Luella directs Effie rather than the reverse, but another important reason is that Luella is strong and healthy and rebellious, whereas Effie has lived in the shadows since her birth—the result of a congenital heart defect that, although entirely curable in our own century, in 1900 has left everyone in the family certain that Effie may die any minute.

So when Luella leads Effie to a Roma camp on the outskirts of New York City, then disappears one day without letting her sister know where she’s headed, Effie is determined to find her, even if it means confronting her fear that their father has had Luella committed to New York’s notorious House of Mercy, a home for wayward women and girls. Effie comes up with a plan to abandon her privileged Gilded Age life and check herself into the House of Mercy. Her plan succeeds admirably—until the moment she discovers her sister is not there. That’s when Effie realizes that getting out of the House of Mercy is a lot more difficult than getting in.

In The Girls with No Names, Serena Burdick, whose previous novel Girl in the Afternoon won the International Book Award for Historical Fiction in 2017, turns a spotlight on the world of “Magdalene laundries” and the many nameless women who passed through them between their founding in the Victorian era and their abolition in the 1990s. In so doing, she paints an absorbing portrait of relationships within families and the ways they can go awry, as well as the hidden strength on which even the seemingly weakest and most damaged among us can draw in times of need.

But Effie’s choice has dire consequences. The child of a well-off Gilded Age family, Effie comes up with a plan to secure her own commitment to New York City’s House of Mercy, a home for wayward girls and women. She does this because she’s been raised all her life with the bogeyman-type threat that bad behavior will lead to her parents’ sending her to the home. Lively, outgoing, rebellious Luella has often been the target of such efforts at verbal “correction.” So when Luella disappears not long after a blazing row with her father, what could be more logical than Effie’s belief that Dad has sent his disobedient daughter to the House of Mercy?

Furthermore, Effie suffers from a heart defect. No one knows when she will die, but since birth she’s been living, in effect, on borrowed time. The chances that she will survive to adulthood have always been poor, and her frequent “fits” of breathlessness constrict her actions. In the House of Mercy, however, hard work and harsh punishments are a way of life. The older girls enforce the rules every bit as savagely as the nuns who run the penitential laundry that is the central element in the House of Mercy’s financial success. And two of those older girls decide that Effie just might be their key to escape.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Effie Tildon loves her older sister, Luella. Sixteen to Effie’s thirteen, Luella has long taken the leading role in deciding what the two sisters do, even when it leads them in directions their parents would not approve of. Those three extra years are one reason that Luella directs Effie rather than the reverse, but another important reason is that Luella is strong and healthy and rebellious, whereas Effie has lived in the shadows since her birth—the result of a congenital heart defect that, although entirely curable in our own century, in 1900 has left everyone in the family certain that Effie may die any minute.

So when Luella leads Effie to a Roma camp on the outskirts of New York City, then disappears one day without letting her sister know where she’s headed, Effie is determined to find her, even if it means confronting her fear that their father has had Luella committed to New York’s notorious House of Mercy, a home for wayward women and girls. Effie comes up with a plan to abandon her privileged Gilded Age life and check herself into the House of Mercy. Her plan succeeds admirably—until the moment she discovers her sister is not there. That’s when Effie realizes that getting out of the House of Mercy is a lot more difficult than getting in.

In The Girls with No Names, Serena Burdick, whose previous novel Girl in the Afternoon won the International Book Award for Historical Fiction in 2017, turns a spotlight on the world of “Magdalene laundries” and the many nameless women who passed through them between their founding in the Victorian era and their abolition in the 1990s. In so doing, she paints an absorbing portrait of relationships within families and the ways they can go awry, as well as the hidden strength on which even the seemingly weakest and most damaged among us can draw in times of need.

Published on January 10, 2020 06:00