C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 19

October 9, 2020

Romance, Murder, and Politics in Renaissance Poland

I’ve written before about P.K. Adams’s Jagiellonian Mystery series and how much I enjoy reading a fast-paced detective story set not in the well-traveled (fictionally speaking) halls of sixteenth-century Western Europe but in Renaissance Poland-Lithuania, a time and place much closer to my own area of historical interest.

I’ve written before about P.K. Adams’s Jagiellonian Mystery series and how much I enjoy reading a fast-paced detective story set not in the well-traveled (fictionally speaking) halls of sixteenth-century Western Europe but in Renaissance Poland-Lithuania, a time and place much closer to my own area of historical interest.When the first book, Silent Water , came out in the summer of 2019, I interviewed the author on this blog. You can find out more about the genesis of the series and its setting in that interview.

But when Jagiellon Mystery no. 2, Midnight Fire, appeared this month, it seemed like a good time to reach out to people who prefer to listen to interviews while they’re working or exercising or just letting off steam. Hence my latest New Books in Historical Fiction podcast episode, which explores some of the same territory as the written Q&A but extends the story forward by twenty-five years, just as the series takes a leap from 1518–1520 to 1545.

So read on to find out more, and stay tuned for future announcements about the joint murder mystery that P. K. and I have produced and hope to see published over the course of the next year or two. Yes, as I’ve mentioned before, we decided it was too good a coincidence to waste—she knowing a lot about sixteenth-century Poland and I about sixteenth-century Russia. Magical things can happen if you take a ride outside your comfort zone, and reading about Bona Sforza and her troubled relationship with her son, Zygmunt August, is one place to start.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Most novels about the sixteenth century written in English take place in Italy, France, or England—with the occasional foray into Spain or Portugal. P. K. Adams’ Jagiellonian Mystery series is a welcome exception. Set at the glittering Italianate court of King Zygmunt I of Poland/Lithuania and his son, Zygmunt August, these books map fictional plots onto real historical incidents to create fast-paced, fluid stories that are as much about the tensions of a culture in transition as what drives a person to commit murder.

In Midnight Fire (Iron Knight Press, 2020), the heroine, Caterina Konarska (formerly Sanseverino) returns to Zygmunt I’s court twenty-five years after the events of Silent Water, the first book in the series. Caterina and her husband undertake the long journey from Italy in search of a cure for their young son, Giulio, who suffers from mysterious fevers that have stumped the doctors in Bari.

In Kraków Caterina discovers a court far different from the one she left a quarter-century before. The old king is dying; his wife, Bona Sforza of Milan and Bari, struggles to hold on to power; and their son, Zygmunt August, threatens to cause an international scandal by marrying his beautiful but disreputable Lithuanian mistress, Barbara Radziwiłł.

Queen Bona offers Caterina a deal: persuade Zygmunt August to give up Barbara, and Bona will arrange an appointment for Giulio with Poland’s premier physician. Seeing no alternative, Caterina accepts. But as she sets off for Vilnius with her son, she has no idea of the danger she faces or the layers of treachery she will encounter in Zygmunt August’s Renaissance palace.

October 2, 2020

The Unknown Degas

A run-down house, an old diary offering insights into late nineteenth-century social life, a boyfriend with secrets, and a young heroine graduating from college on the brink of the Second Wave of the Women’s Liberation Movement, in a decade almost as dramatic as our present—these ingredients intertwine with the historically attested but little-known story of the painter Edgar Degas’s visit with the New Orleans branch of his family in Linda Stewart Henley’s sparkling debut novel Estelle.

A run-down house, an old diary offering insights into late nineteenth-century social life, a boyfriend with secrets, and a young heroine graduating from college on the brink of the Second Wave of the Women’s Liberation Movement, in a decade almost as dramatic as our present—these ingredients intertwine with the historically attested but little-known story of the painter Edgar Degas’s visit with the New Orleans branch of his family in Linda Stewart Henley’s sparkling debut novel Estelle. In our New Books Network interview, Henley reveals how she found out about Degas’s journey and researched his family relationships. We also talk about how she became a fiction writer, why she added the more contemporary angle, how New Orleans itself has changed over time, and what made this short period in Degas’s life so crucial to his development as an artist. So read on to get a sense of the story, then listen to the interview. You can also read a short transcript and hear the whole through the New Books Network tab on the Literary Hub.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

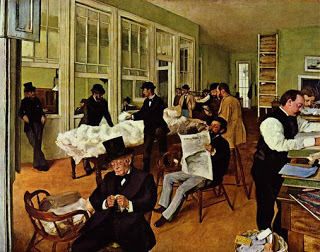

Most people think of Edgar Degas as a French painter of ballerinas. But few have heard that his mother came from New Orleans or that he spent five months in the city between October 1872 and February 1873. That five-month period proved crucial to Degas’s career, moving him from the status of a relative unknown dabbling in the not-quite-respectable world of the Paris Opera into an artist of renown. And although he went back to painting ballerinas—many of his most famous works date from 1873 and later—it was his study of his brothers, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, that won him the critical acclaim that pushed him into the next stage of his career.

In Estelle (She Writes Press, 2020), Linda Stewart Henley takes this vital transition as her starting point for a dual-time story in which a young woman named Anne Gautier, twenty-two years old and fresh out of college, inherits an old house on Esplanade Avenue in New Orleans in 1970. While overseeing renovations and dealing with protestors opposed to urban renewal that displaces the poor, Anne discovers an old journal that sheds light on Degas, his friends and family and sojourn in the city—in a house just down the street from hers. Her attempts to uncover more information reveal mysteries both personal and artistic, and soon Anne must tackle some very basic questions regarding what she wants from life.

Interspersed with Anne’s story is the narrative of Degas’s sister-in-law, the Estelle of the title, as she welcomes her visiting brother-in-law and observes his adjustment to family life. Estelle has troubles of her own: she’s pregnant with her third child, she’s losing her eyesight, and her marriage suffers as the family cotton business struggles to stay afloat in the aftermath of the US Civil War. Yet she perseveres, and these relatively quiet domestic scenes contrast well with Anne’s more dramatic conflicts and with the occasional diary entries reproduced from the journal Anne has discovered. The end result is a thoroughly enjoyable tale of the changing fortunes of a great city and the life of an artist, told through the perspectives of three women governed by expectations that are in some ways quite similar, although the options available to them are not similar at all.

Image: Edgar Degas, A Cotton Office in New Orleans (1873), public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

September 25, 2020

Interview with Clare McHugh

I love a good novel about Tudors or Windsors as much as the next person. But I also admire—and enjoy books by—novelists who go beyond the “short list” of literary favorites to explore the lives of often undeservedly ignored historical figures. Princess Vicky, the eldest daughter of Britain’s Queen Victoria, is one such personage. Raised in the knowledge that, no matter how competent or knowledgeable she might be, she would probably never have the opportunity to fill her mother’s shoes, Vicky entered into a typical royal marriage and did her best to cope with the expectations of a country that had little use for her strong personality or her liberal ideas. It is in some ways not a happy story, but as told by Clare McHugh in A Most English Princess, it is both a compelling and a rewarding one.

Clare was kind enough to answer my questions about her book and how she came to produce it. Read on to find out more.

A Most English Princess is your first novel. How did you get into writing fiction?

I have a dog-eared copy of John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist that I read repeatedly and carried around for years. But I struggled to believe that I could write a decent book: I revere too many authors. The abrupt end of my career as a magazine editor made me think: if not now, when? I just jumped in. I was lucky to find a good teacher and a good editor who helped me a lot. Fiction is very different from journalism, which I practiced for thirty years.

And what drew you to the story of Princess Vicky?

Like Vicky, I am the eldest in my family and have a brother just a year younger. I could relate to how painful it would be to be passed over—as she was for the throne—because she was considered “lesser,” a girl. It’s a good thing that the law was changed after Prince William married Kate Middleton, and now the eldest child of either sex inherits. It’s interesting to note that Vicky was the last person passed over because she was female. The monarchs since Victoria either had boys first, or in the case of the current queen’s father, only girls.

When we first meet Vicky, she is at the end of her life and the empress of Germany. What made you decide to start there?

I aimed to heighten the stakes by showing readers that this is not a happily-ever-after story, and that Vicky, a very privileged person, had to cope with some terrible disappointments. Being a princess is not all it’s cracked up to be, even in the old days. I also wanted to contrast her relationship with her surrogate son, her godson Fritz Ponsonby, and her actual son, Kaiser Wilhelm. The former revered her, and the latter opposed her. How did that come about? I hoped readers would be intrigued by this question and read on.

We soon go back in time and encounter Vicky as a young girl. How would you describe her, and what is the basis of her grievance against her brother Bertie?

Vicky was a very confident, very talkative, very bossy little girl. As a child she was well aware she was the superior student and physically more able than her younger brother—she could ride, swim, and climb better than he. Bertie struggled, especially in the schoolroom. Today, we would describe Bertie as having mild learning disabilities. But Bertie had a very affectionate personality, and while Vicky thought she would be a better heir and as the eldest deserved the throne, when she was a young child it was explained to her why that could not be. After that she contented herself with telling Bertie what to do and recruiting him for various games of her own devising. They were good friends their whole lives long except when politics interfered!

How does Vicky relate to her famous parents, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert?

It was a tricky dynamic between the three of them. Prince Albert adored Vicky and showered her with praise and attention. Queen Victoria often felt jealous, and it’s hard to blame her because Prince Albert was in the habit of scolding his wife for her perceived shortcomings! But after Vicky left home, she and her mother became very close, exchanging letters several times a week, as they commiserated on the challenges of royal life, Vicky’s difficult in-laws, and the raising of many children.

And how does Vicky get to Prussia? What are the highlights (or low lights) of her experience there? What makes her story “tragic,” to quote your book description?

Vicky marries Fritz, the heir to the Prussian throne, and moves to Berlin with him, but from the very first the Prussian royal family treats Vicky badly. In some ways it echoes what happened between Meghan Markle and the British royals—a bad fit. Vicky was a liberal, trained by her father to believe in democratic government, freedom of speech and religion, and more rights for women. Not only did many Prussians disagree with these ideas, they resented that this teenage princess presumed she could arrive and tell them how to run their country. And Vicky sometimes lacked tact. But her predicament was made much worse by bad luck. Her and Fritz’s firstborn son was born with a withered arm, the Prussian government was taken over by the autocratic Otto von Bismarck, who was deeply suspicious of Vicky, and then three wars made Prussia the dominant power in Germany. The German nation was united under a very militaristic and bellicose Prussian regime, and Vicky’s damaged son was subsumed into this nationalistic atmosphere, rejecting the liberal ideas of his parents. The whole world suffered because of the way history played out in this family, in this country.

This book has just come out. Are you already working on something new?

I am toggling between two things. I am outlining a second book about Vicky, concerning her husband’s ninety-nine-day reign as Kaiser, and her efforts to protect him and advance his liberal ideas. I will go forward with it if readers seem to like Vicky. I am also writing a historical novel set in 1970s and 1980s America, a period I know much about first hand.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Before turning to fiction, Clare McHugh worked as a journalist, magazine editor, and history teacher. Born in London, she grew up in the United States and graduated from Harvard with a degree in European history. A Most English Princess is her first novel. Follow her on Twitter (@Claremch) and check out her website claremchugh.com for blog posts, details of her research into the royal families of Britain and Germany, and her book reviews of both fiction and nonfiction.

September 18, 2020

Interview with Heather Bell Adams

When Heather Bell Adams wrote to me suggesting an interview for her new novel,

The Good Luck Stone

, I have to admit that my first reaction was “Oh, no, not another WWII book!” But in this case, I’m so glad I took the plunge. It’s something of a cliché to say that one can’t put a novel down, yet these characters are so strongly and beautifully portrayed that I couldn’t wait to get back to reading their story. Read on to find out more.

When Heather Bell Adams wrote to me suggesting an interview for her new novel,

The Good Luck Stone

, I have to admit that my first reaction was “Oh, no, not another WWII book!” But in this case, I’m so glad I took the plunge. It’s something of a cliché to say that one can’t put a novel down, yet these characters are so strongly and beautifully portrayed that I couldn’t wait to get back to reading their story. Read on to find out more.

Your first novel, Maranatha Road, appeared in 2017. Could you give us a short summary of that book?

Maranatha Road is about Sadie Caswell, whose son dies shortly before his wedding, and Tinley Greene, the young stranger who shows up claiming she’s pregnant with his child. It’s set in western North Carolina, where I’m from.

The Good Luck Stone just came out. What made you want to tell a story about World War II nurses in the Philippines?

There are so many wonderful World War II stories set in Europe. I wanted to try something different. Obviously, in addition to the European theater, there was a lot happening in the South Pacific, and it’s intriguing to explore how war looks in what otherwise might be considered a tropical paradise.

I did quite a bit of research about the nursing units who served in that area of the world and tried to incorporate historical events as much as I could. As I dug into the research, I was surprised to learn about the Army and Navy nurses who were taken prisoner of war by the Japanese. I knew I wanted to include that piece of history in The Good Luck Stone.

We first meet your main character, Audrey Thorpe, late in life. How would you describe her at this stage of her development?

At ninety years old, Audrey is a society woman in Savannah, Georgia—on all the right boards and committees around town. But she’s beginning to wonder about the legacy she will leave behind, particularly to her great-grandson. This leads her to re-assess the big secret she’s kept since the war. When we first encounter her, nobody knows the real Audrey.

Next we flip back in time. Audrey is landing in the Philippines. By the end of chapter 2, she has met Kat and Penny, forming a relationship that is central to the story. Tell us a bit about the friendship that develops among these three young women. What is their mission and what causes them to bond?

The friendship between Audrey, Kat, and Penny is the central driving force of the narrative. They meet in the bustling capital of Manila at a time when war lurks on the horizon. When they open up to each other about their fears, that vulnerability forms the basis of a meaningful friendship. Of course, as the hardships and sacrifices of war intervene, the promises they’ve made will be sorely tested.

Her family has doubts about Audrey’s ability to take care of herself, which brings Laurel Eaton into the story. She’s very differently situated from Audrey. What can you tell us about her?

Laurel, a middle-aged mother, is a bit down on her luck when we first meet her. She’s so grateful to be hired as Audrey’s caretaker and, much to her surprise, the two women seem to bond, despite their difference in circumstances. Laurel clashes a bit with her husband, who cautions her not to get in too deep.

It’s a devastating blow when Laurel arrives at Audrey’s mansion one day to find that the older woman has disappeared. Originally, I had that scene as a prologue, but my agent convinced me to keep the narrative chronological, which I believe was absolutely the right choice.

Dual-time stories can be difficult to handle, because the historical plot so often outweighs the contemporary one in terms of dramatic tension. That’s not true in this case. Without giving away spoilers, can you hint at how the two narratives intertwine?

Thank you so much for saying that! It’s something I worked hard on, trying to keep both narratives interesting. I always admire that as a reader when I pick up a dual timeline story.

In The Good Luck Stone, the past and present intertwine when Audrey’s secret from the war begins to unravel. As Laurel sets out to look for her, she’ll discover that the real Audrey Thorpe is not the same woman who appears in the society pages.

As I worked on the first draft, I realized that the theme of friendship was revealing itself in the present-day timeline as well, in the sense that Laurel and Audrey have the opportunity to become much more than employer/employee.

Also, Laurel’s ten-year-old son, Oliver, is attending a new school and he’s understandably concerned with how to make friends. Along the way, he learns something about that from watching his mother interact with Audrey. I didn’t necessarily plan this subplot, but I was delighted as it developed.

Are you already working on something new?

Yes, I’m working on a third novel, which is set in western North Carolina and (at least for now) revolves around a reclusive artist. I’m excited about it—and definitely thankful to have writing as an outlet during these unsettling times.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Heather Bell Adams is the award-winning author of the novels Maranatha Road and The Good Luck Stone. Her short stories and literary scholarship have appeared in numerous literary magazines and reviews. A native of Hendersonville, North Carolina, she lives in Raleigh, where she works as a lawyer.

September 11, 2020

In Memory of 9-11

Nineteen years ago on this date, in what seems now like another universe—so much has happened in the interim—I was getting ready to walk upstairs and start my workday when my husband came in and turned on the TV. It was 8:45 AM, give or take a minute or two, and I objected. “Since when do you watch TV in the morning?”

Nineteen years ago on this date, in what seems now like another universe—so much has happened in the interim—I was getting ready to walk upstairs and start my workday when my husband came in and turned on the TV. It was 8:45 AM, give or take a minute or two, and I objected. “Since when do you watch TV in the morning?”“Something’s happening in New York,” he said. And as we watched, the second plane crashed into the World Trade Center. One could have been an accident, but two made the conclusion inescapable: someone had done this on purpose. From the moment it happened, on a clear blue day with no signs of rain, the nightmare was immediate and all-encompassing. A third plane attacked the Pentagon; a fourth, commandeered and diverted by its passengers, crashed in a field in western Pennsylvania. The images played nonstop on the news broadcasts for days.

Two weeks before, we had attended a family wedding in the city. I remember pointing out the Twin Towers to our then young son. The wedding itself was held in Lower Manhattan, the area most devastated by the attack. It was not the first terrorist attack using planes or even the first on the World Trade Center, but even now, almost two decades later, the loss of three thousand people, many of whom were just going to work and minding their own business is shocking, horrifying.

So let’s take a moment to remember those workers as well as the first responders, the orphaned children and widowed spouses, and the many other deaths caused by the attack through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—all casualties of 9/11, together with our lost innocence, our sense that such atrocities could never happen.

Perhaps we were naive to believe that we were immune from danger. People inflict horrors on one another throughout the world and throughout time. The United States has been both perpetrator and victim, and the current unrest over the very real abuses committed against US citizens of color shows that even internally the country has a long history of violence. In that sense, the safety of the pre-9/11 world was as much illusion as fact. It’s not enough to recall and honor the past. We also need to craft a better future.

An entire generation has grown up since then. Some of its members are the children of those who died. Like the ordinary workers and their families, and especially the heroes who willingly sacrificed themselves to help others, they too deserve their moment of homage, our acknowledgment of what they lost.

Image: World Trade Center, New York, aerial view, March 2001 © Jeffmock - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

September 4, 2020

Interview with Linda Kass

The significance of World War II, seventy-five years after its ending, continues to inspire novelists as well as historians. Just last weekend, the New York Times Book Review devoted its entire issue to works—mostly historical but in some cases fictional—about the war. Yet enterprising and creative people continue to find new ways to approach the issues raised by that massive conflict.

The significance of World War II, seventy-five years after its ending, continues to inspire novelists as well as historians. Just last weekend, the New York Times Book Review devoted its entire issue to works—mostly historical but in some cases fictional—about the war. Yet enterprising and creative people continue to find new ways to approach the issues raised by that massive conflict.Because of the intense trauma and agony inflicted by the Holocaust and the death camps, one area that often receives less attention is families that managed to escape Europe before war was declared. This week’s interview with Linda Kass, however, explores this angle. Read on to find out about A Ritchie Boy , released by She Writes Press on September 1, the eighty-first anniversary of Hitler’s invasion of Poland, and the book that preceded it, which also took place in a setting that has often been ignored in World War II novels.

Your first novel, Tasa’s Song, came out in 2016. Readers can find out more about that novel from our podcast interview at New Books in Historical Fiction, but can you give us a short summary here?

Sure! Tasa’s Song tells the story of aspiring Jewish violinist Tasa Rosinski, whose secure world unravels amid the gathering storm of World War II. After an initial scene of her family escaping their home in the darkness of night in frigid winter, the narrative reverts back to her peaceful village in eastern Poland, where she lives among her loving family. The story marches along history’s trail to reveal a young Jewish prodigy caught between the Nazi threat to the west and the Soviets to the east as Tasa comes of age in the shadow of encroaching war and finds redemption in her music and through deep love, despite the horrors that draw near. In the end, it is a story of resilience and survival, celebrating the bonds of love, the power of memory, the solace of music, and the enduring strength of the human spirit.

In the new novel, we meet your main character, Eli Stoff, as an old man. We find out early on that there is a connection between him and the first novel, although I won’t ask you to say what it is. But where is he at this point in his life, and why did you decide to start here?

Great question! My book could actually be called a “novel-in-stories,” as different characters tell interrelated stories that, together, form a multi-layered portrait of Eli Stoff and his journey from one homeland to another, and from boyhood to manhood. Theoretically, each of these stories could be read as stand-alone stories, all linked to Eli and related to the decade between 1938 and 1948. (Two stories were actually published as independent stories in literary journals prior to the publication of A Ritchie Boy.) While I didn’t write the stories in the order they appear, they are arranged chronologically and that gives the book a very novel-like presentation. Each story reveals the particulars that influence Eli’s life—the circumstances and people that he encounters from his boyhood in Vienna to New York, where immigrants first encounter America; to Ohio, where his family settles; to Maryland and Camp Ritchie, where he joins thousands of others like him—young immigrants from Germany or Austria who have an understanding of the German language and culture and are trained as military intelligence officers and end up helping the Allies win World War II. The narrative continues with Eli’s travel to war-torn Europe as an American soldier before he returns to the Midwest to set down his roots.

I decided to begin in the near present, in 2016, when Eli is ninety-three, as he receives an unexpected letter inviting him to a Ritchie Boy reunion. His memories of that important decade in his life come flooding back, disrupting his predictable routine at Hillside Senior Living Residences, where he lives. Beginning this way provides a container for all the stories to come, a vessel that transports the reader into all those crucial moments of Eli’s life, beginning with his tense boyhood in Vienna.

As we get older, we look back and see how we got to be who we are, but that future eludes us when we are young. It seemed fitting for the telling of this story about Eli’s journey to begin at that late point in life. I used a quote from Shakespeare for my epigraph that explains this best, “We know what we are, but not what we may be.”

The novel then snaps back to 1938, where Eli is a teenager living in Vienna. What is his situation at this time?

In 1938, Eli and his family, who are secular Jews, live in Vienna where anti-Semitism is spreading. Eli’s best friend is Toby Wermer, a non-Jew who lives in the same apartment building, a friend since they were six and attending Volksschule together. An undercurrent of tension has been brewing at their school all year, with Eli being taunted by other students. And that is the backdrop for an optional school-sponsored ski trip Eli takes with Gentile classmates—all of them around fifteen years of age—during a weekend in early March. The ten boys travel by train, with a supervising teacher, to a medieval Alpine village in western Austria on the cusp of the Anschluss, where some semblance of camaraderie turns somber by the time they return to Vienna.

How do Eli and his family get to the United States?

A childhood friend of Eli’s mother, Zelda Muni, who had earlier immigrated to America with her husband, seeks help from a powerful Jewish businessman, John Brandeis, to sponsor the Stoffs’ escape from the growing peril in Vienna. Brandeis signs affidavits for the Stoffs. He had been helping other Jews escape Europe, ensuring each family would not become a public burden. Brandeis’ altruistic act, for people he didn’t know and expecting nothing in return, left an indelible mark on Eli for the rest of his life.

Eli begins his education in at Ohio State University but leaves partway through to become “a Ritchie boy,” as per your title. What was a Ritchie boy, and what does his new status require of Eli?

I alluded to what a Ritchie Boy was in the answer to the second question. I’ll get more specific here. The book title and the name of the soldiers come from Camp Ritchie, a military training facility near Hagerstown, Maryland, where the US Army centralized its intelligence operations beginning in June 1942, not long after US forces landed in North Africa and helped drive the German Army off the continent. In the early part of World War II, the Army sought soldiers familiar with the German culture, thinking, and language to carry out a variety of needed duties, including interrogation of prisoners and counterintelligence. Many recent immigrants from Germany or Austria who had this ability to speak or comprehend the language of the enemy got routed to Camp Ritchie on secret orders. There thousands were trained to perform specialized tasks, which provided advanced intelligence to allied forces regarding German war plans and tactics. Thus their nickname—the Ritchie Boys.

And what drew you to tell this story?

My father was a Ritchie Boy and is the inspiration for this fictional story. He, too, grew up in anti-Semitic Vienna in the 1920s and ’30s, escaped with his parents thanks to the kindness of a stranger, lived his teenage years in the Midwest as World War II began, was recruited and trained by the US Army at Camp Ritchie, and returned to the theater of war just six years after coming to this country to fight the very enemy he barely escaped in 1938. My father died in early 2017. Many of his comrades are gone as well now that we have reached the seventy-fifth anniversary of the war’s official ending (September 2, 1945). These brave soldiers contributed to our victory in World War II, yet many are not aware of this. One Army study estimates that almost sixty percent of the intelligence collected in Europe came from interrogations conducted by Ritchie Boys. Telling this history through fiction builds a human story and allows the reader to experience, and be present in, that narrative. The stories in A Ritchie Boy are an attempt to bring that time and those characters to life so others, too, can remember their sacrifice.

This book has just come out. Are you already working on something new?

Yes, I am in the early stages

of my third novel. It will again be historical fiction, during that time period I seem to gravitate toward: 1936 to 1946, in this case. It is based on a real, and fairly well-known, character whose early life I find fascinating.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Linda Kass, a writer of both fiction and nonfiction, is an assistant editor of the online literary magazine Narrative and the owner of Gramercy Books—an independently minded, carefully curated neighborhood bookstore in Bexley, Ohio. She Writes Press published her first novel, Tasa’s Song, in 2016 and her second, A Ritchie Boy, in 2020. Find out more about her at her website (https://www.lindakass.com).

Linda Kass, a writer of both fiction and nonfiction, is an assistant editor of the online literary magazine Narrative and the owner of Gramercy Books—an independently minded, carefully curated neighborhood bookstore in Bexley, Ohio. She Writes Press published her first novel, Tasa’s Song, in 2016 and her second, A Ritchie Boy, in 2020. Find out more about her at her website (https://www.lindakass.com).August 28, 2020

The Many Faces of Love

The trials and tribulations of the English royal family never fail to fill tabloids and news broadcasts. But while today’s Windsors are guaranteed media bait, few of the current flaps can match that of 1938, when Edward VIII abdicated the throne not long after his succession so that he could marry a divorced American, Wallis Simpson. In doing so, he capped a spectacular romantic career filled with many affairs, mostly with married women, to the utter embarrassment and despair of his family.

The trials and tribulations of the English royal family never fail to fill tabloids and news broadcasts. But while today’s Windsors are guaranteed media bait, few of the current flaps can match that of 1938, when Edward VIII abdicated the throne not long after his succession so that he could marry a divorced American, Wallis Simpson. In doing so, he capped a spectacular romantic career filled with many affairs, mostly with married women, to the utter embarrassment and despair of his family. In my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview, Bryn Turnbull—whose debut novel, The Woman before Wallis , came out with MIRA Books just this past Tuesday—talks about the events leading up to King Edward falling for Simpson, in the days when he was still the Prince of Wales, known to his friends and family as David. The outline of the story appears below, but as Turnbull notes toward the end of our interview, the book is actually less about David and Thelma, the woman that Wallis replaced, than about the bond between two sisters, each caught up in her own international scandal of massive proportions. It also explores the complex relationships between husbands and wives, mothers and children, and even stepmothers and stepchildren. In that sense, this is a novel about far more than one almost-forgotten royal mistress.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Most modern Americans can identify the names Wallis Simpson and Gloria Vanderbilt. But Simpson was not the first divorced American to win the heart of Great Britain’s future if short-reigned King Edward VIII, known to his family as David. This debut novel explores the life and loves of Thelma Morgan, whose twin sister Gloria married Reggie Vanderbilt and became the mother of the well-known fashion designer.

After the ending of what these days we would call a “starter marriage,” Thelma accepts a proposal from Viscount Duke Furness, who takes her to his country estate and introduces her to his children. He also, in due course, introduces her to David and, when she and the prince fall for each other, steps aside and chooses not to contest their affair. The reality that Lord Furness has not himself practiced fidelity is one of the factors driving Thelma away from him.

Meanwhile, Gloria and Reggie have taken refuge from the twins’ mother in France, where they are raising their daughter, Little Gloria. Reggie dies prematurely, and Gloria becomes involved in the kind of knock-down, drag-out contest over his inheritance that only dysfunctional families can produce. Desperate to support her sister, Thelma abandons the UK for New York City, David’s assurances of love ringing in her ears. Unfortunately, not long before she leaves England, she introduces David to her friend Wallis Simpson …

Bryn Turnbull does a wonderful job of portraying this history, which is in some ways more dramatic than any made-up story could be.

August 21, 2020

Interview with Gill Paul

I discovered Gill Paul almost by accident, when her publicist for The Lost Daughter wrote to me asking if I was interested in interviewing her. At the time, I was booked solid, so I passed the opportunity on to fellow New Books Network host Jennifer Eremeeva. But I read both The Lost Daughter and its predecessor, The Secret Wife, with great interest. So when I received an advance copy of Gill’s latest,

Jackie and Maria

, I followed up immediately.

I discovered Gill Paul almost by accident, when her publicist for The Lost Daughter wrote to me asking if I was interested in interviewing her. At the time, I was booked solid, so I passed the opportunity on to fellow New Books Network host Jennifer Eremeeva. But I read both The Lost Daughter and its predecessor, The Secret Wife, with great interest. So when I received an advance copy of Gill’s latest,

Jackie and Maria

, I followed up immediately.Alas, the message got lost in transit, and months passed before I found out what had happened. But Gill was kind enough to answer my written questions instead. And since William Morrow released her book just this past Tuesday, the timing couldn’t be better. Read on, and find out more about three fascinating women and at least one equally fascinating man.

Last I heard, you were writing about the Russian imperial family. What drew you to the story of Jackie Kennedy, Aristotle Onassis, and Maria Callas?

It’s quite a leap, I agree! The idea of writing about the Kennedy/Callas/Onassis love triangle was suggested to me by a reader in Athens, who got in touch via Twitter, and immediately I was desperate to do it. The story is most often told from Jackie Kennedy’s point of view, but I wanted to explore the other angles, filling out Ari’s character and telling Maria’s side too. I love writing unconventional love stories, with heartbreak, betrayal and infidelity—not sure what that says about me. This story ticked all the boxes, and it had glamorous locations too. Fortunately I wrote it in 2019 when I was still able to travel to the Mediterranean and explore them.

You’re quite explicit in your Historical Afterword that this novel is your own take on the world you depict. How would you describe your Jackie Kennedy and how she decides to marry Aristotle Onassis?

I’ve been a fan of Jackie Kennedy for decades, but her decision to marry Onassis always puzzled me. We know she was an intelligent woman, who had many well-qualified suitors in the years after Jack Kennedy died, yet she chose a man with whom she had little in common. Was it solely for the money? Her mother had raised her to prioritize wealth, and Jackie was a compulsive shopper, so Ari’s bank balance was definitely a factor, but if that were the only reason it makes her seem very cold-hearted. In the end, I was persuaded by biographer Barbara Leaming’s theory that Jackie was suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder when she married for the second time. She wanted to feel safe and thought Ari’s millions could provide security—but it soon transpired that they couldn’t.

Jackie knows that her sister Lee had an affair with Onassis, yet this doesn’t deter her. What does this tell us about them and their relationship?

Isn’t it odd? In the unlikely event that I wanted to date one of my sister’s exes, I would at the very least ask if she minded. It seems to me that the Bouvier sisters were never especially intimate: they both liked clothes and holidays in sunny locations, but any friendship was on a superficial level. Lee was always competitive, trying to outdo her older sister. I suspect Jackie didn’t approve of Lee’s extramarital affairs during her marriage with Stas Radziwill, especially since she had personally interceded with the Pope to help get Lee’s first marriage annulled. Although Lee was supportive after Dallas, the rift between them widened throughout the 1960s. It’s widely documented that Jackie asked Onassis to telephone and tell Lee they were getting married, rather than calling herself, implying that she knew Lee would be upset. Gore Vidal reported Lee screaming, “How could she do this to me?”

I learned a lot about Onassis from reading this novel; he was always a name to me before. How would you summarize his character? What’s important to know about his past?

Ari had a tragic childhood: his mother died when he was three, and many family members were murdered when the Turks drove the Greeks out of Smyrna in 1922. He had a difficult relationship with his father and set off alone to make his fortune in South America, through a mixture of hard work, shrewd investment, and innate canniness. He didn’t treat women with much respect, but in that he was no different from many other men of his era. A key to his character is that he always wanted the best of everything, from champagne to yachts to women, and I have Maria comment in the novel that it’s as if he’s still trying to prove himself to his father. In marrying Jackie Kennedy, he hoped to establish himself as a great lover, worthy of the world’s respect, and instead he became an object of ridicule.

The real love of Onassis’s life, at least in this book, is not Jackie or Lee but the opera star Maria Callas. I would guess that most of my readers have heard her name, but as with Onassis may not know much about her as a person. What would you like us to understand about her and her long relationship with Onassis?

The first thing to know about Maria is that many opera experts still judge her to have been the greatest first soprano of all time. The voice is spectacular, giving me goose bumps whenever I listen. Her life wasn’t easy, but her years with Ari were her happiest. His closest friends liked her the best of all his women, and I think that says a lot. Their relationship was volatile—glasses were thrown and faces were slapped—but they were lovers in the true sense, as well as close companions. I hadn’t realized till I began researching this book that they were still a couple at the beginning of August 1968, just over two months before he married Mrs Kennedy—and that he tried to win Maria back three weeks after the wedding. Talk about wanting to have your cake and eat it! In my opinion, he made a big mistake in not marrying Maria. She is the woman who would have looked after him through the illness and tragedy that beset him as he grew older, the only one who loved him for himself instead of his money.

This book has just come out. Are you already working on something new?

I’ve delivered the next one but I’m not allowed to divulge the subject yet. And I’ve started researching the one after, which will be my eleventh novel. I feel incredibly lucky!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Gill Paul’s historical novels have reached the top of the USA Today, Toronto Globe & Mail, and UK Kindle charts, and been translated into twenty-one languages. She specializes in relatively recent history, mostly twentieth-century, and enjoys re-evaluating real historical characters and trying to get inside their heads.

Gill Paul’s historical novels have reached the top of the USA Today, Toronto Globe & Mail, and UK Kindle charts, and been translated into twenty-one languages. She specializes in relatively recent history, mostly twentieth-century, and enjoys re-evaluating real historical characters and trying to get inside their heads.Gill also writes historical nonfiction, including A History of Medicine in 50 Objects and a series of Love Stories. Published around the world, this series includes Royal Love Stories, World War I Love Stories, and Titanic Love Stories. Find out more about her at http://www.gillpaul.com.

August 14, 2020

Writing in the Time of Coronavirus

There’s a meme going around the Internet: a writer’s (or editor’s) life before and after Covid-19. The two images are exactly the same: a harried woman, alone at her desk, stares at a computer screen.

There’s a meme going around the Internet: a writer’s (or editor’s) life before and after Covid-19. The two images are exactly the same: a harried woman, alone at her desk, stares at a computer screen.As with most memes, this one strikes at a core of truth. I worked from home before the pandemic, and I work from home now. I got most of my social contacts through e-mailing a far-flung collection of authors and editors multiple times a day then, and the same now. After years of traveling outside several times a week to attend ballet class, my teacher retired at about the time when I could no longer perform every step required, so I even exercise at home (still ballet, but toned down to fit my capabilities). And when I am neither working nor exercising nor goofing off through the usual collection of lightweight literature, movies viewed on my tablet, and crossword puzzles, I type madly into my Mac recording the thoughts, speech, and actions of imaginary people.

And yet … even for me, life in lockdown doesn’t feel the same as it did before. Not going out during the workday used to be a choice; now it’s become an avoidance of risk, if not a necessity—even a commitment to protect others. Social distancing doesn’t come easily to writers anymore than it does to nonwriters. I find myself eager for movies where people crowd a dance floor, throw their arms around each other, stand far closer than current standards permit, never think of donning a mask to accept a bag of vegetables from the neighbor with diabetes. I yearn for the world I took for granted, in which calling a plumber or electrician or making a hair appointment didn’t feel like a radical step.

And yet … even for me, life in lockdown doesn’t feel the same as it did before. Not going out during the workday used to be a choice; now it’s become an avoidance of risk, if not a necessity—even a commitment to protect others. Social distancing doesn’t come easily to writers anymore than it does to nonwriters. I find myself eager for movies where people crowd a dance floor, throw their arms around each other, stand far closer than current standards permit, never think of donning a mask to accept a bag of vegetables from the neighbor with diabetes. I yearn for the world I took for granted, in which calling a plumber or electrician or making a hair appointment didn’t feel like a radical step.

Then there are the Covid dreams: vivid and enthralling and so real I have to shake myself when I wake up to be sure that didn’t happen. I even asked Sir Percy once what someone had said when he came to the door, only to have him look at me and say, “Someone came to the door last night? I think I’d remember that.” And he was right: it was a dream.

So as we work our way through these crazy times, hoping for a cure or a vaccine and the chance to resume our normal lives—to send the kids back to school or return to the office (although personally I much prefer working from home)—let’s take a moment to appreciate the world we used take for granted, the one where we hugged friends on greeting and visited family members or friends, where the neighborhood block party was held every year without fail.

Come to think of it, that’s one perk a historical novelist does have: we can retreat into an imagined past, where all the plagues are virtual and where we call the shots. Time to send some characters to a New Year’s Eve celebration, where you can be sure they won’t stand six feet apart …

Images: woman and ballet dancers purchased by subscription from Clipart.com; color spiral from Pixabay (no attribution required).

August 7, 2020

The Perils of Collecting

Although I was sad to see Elsa Hart moving away from her wonderful series of mystery novels set in early Qing China, it’s always fun to explore a new fictional arena in the hands of such a gifted storyteller. In my latest interview with her for the New Books Network, she discusses why she moved her literary focus west (and a few years earlier), to Queen Anne’s London in 1703.

Although I was sad to see Elsa Hart moving away from her wonderful series of mystery novels set in early Qing China, it’s always fun to explore a new fictional arena in the hands of such a gifted storyteller. In my latest interview with her for the New Books Network, she discusses why she moved her literary focus west (and a few years earlier), to Queen Anne’s London in 1703.In fact, The Cabinets of Barnaby Mayne is, in a sense, a prequel to Jade Dragon Mountain and its sequels. Dedicated readers of the earlier (and, I hope, ongoing) series will enjoy a cameo appearance by one of the characters; others will appreciate the new book on its own terms.

In short, this is a book about collectors—not the everyday kind who accumulate more owl statues than most people ever imagine needing or aim for a complete set of 1893 coins or stamps. Collectors like Barnaby Mayne grab everything they can find: fossils and ferns, snake skins and pickled body parts, skulls and statuettes. Mayne’s house is less a carefully curated museum than a madhouse of objects stored in and on every available surface and coveted by his fellow collectors all over London.

So when he shows up dead one day, the immediate question becomes what to do with all this stuff. His widow can’t wait to sell it to the highest bidder; solving the crime takes a back seat, in her view. (One imagines Sir Barnaby might not have been the kind of spouse one would miss. On the page he is unremittingly self-centered.) Only Lady Cecily Kay, an amateur botanist mining the collector’s plants for specimens that match those she’s brought back to England, can’t resist the intellectual puzzle of who, exactly, murdered Sir Barnaby and why.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Lady Cecily Kay has just returned to England when she encounters Sir Barnaby Mayne. It’s 1703, Queen Anne is on the throne, and London’s coffee houses are buzzing with discussions of everything from science and philosophy to monsters and magic. Of course, Cecily has no plans to join the ongoing conversations; coffee houses bar the door to female visitors, however intelligent and learned. But she has secured something better: an entrée to the house of the city’s most influential collector, where she can compare her list of previously unknown plants to his rooms filled with specimens and, with luck, identify them.

On Cecily’s first day in the Mayne house, however, Sir Barnaby is stabbed to death. His meek curator confesses to the crime, and even the victim’s widow seems willing to ignore any discrepancies in the evidence. With assistance from Meacan Barlow, an illustrator also living in Sir Barnaby’s house, Cecily sets out to tie up the loose ends on a murder that far too many people would prefer to remain unsolved. Her quest leads her into the shadowy world of London’s collectors, who will stop at nothing to cut out the competition and have no qualms about silencing a pair of nosy women who are coming too close to the truth.

Elsa Hart, the author of the famed Li Du novels, here brings her talent for spinning a great yarn and crafting a compelling mystery to a new place, which—as you will learn in the interview—is in fact her original literary destination, attained at last.