C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 20

July 31, 2020

Echoes of the Past

In the history we learn (or, too often, endure) in school, the Renaissance is a shining light at the end of the medieval tunnel, itself an improvement over what came before. The names say it all, don’t they? The Roman Empire dies under the clashing swords of barbarians from the north, plunging Europe into the Dark Ages and a slow climb through that mixture of feudalism and religious monotheism known as the Middle Ages, ending in a burst of cultural creativity characterized as Rebirth.

In the history we learn (or, too often, endure) in school, the Renaissance is a shining light at the end of the medieval tunnel, itself an improvement over what came before. The names say it all, don’t they? The Roman Empire dies under the clashing swords of barbarians from the north, plunging Europe into the Dark Ages and a slow climb through that mixture of feudalism and religious monotheism known as the Middle Ages, ending in a burst of cultural creativity characterized as Rebirth.But rebirth of what? In school we learn about the return to classical learning, the restoration of humanity to the center of our understanding of the universe, a secular approach supposedly recovered from antiquity—as if the ancient Greeks and Romans had no gods and exercised no control over inconvenient naysayers who refused to honor the emperor as divine. We encounter Michelangelo and his David, Leonardo da Vinci and his flying machine (and so much else), Martin Luther and his Ninety-five Theses—and, admittedly, the Borgias, although even they come across as somehow “modern” compared to Charlemagne and bubonic plague.

But as Erika Rummel shows in her interview on New Books in Historical Fiction, and even more clearly in her latest novel, The Road to Gesualdo , which we discuss in that interview, the reality of the Renaissance—even in its Italian birthplace—was a great deal more complicated than the simplistic picture would indicate. And since fiction tends to benefit from forays into the less savory elements of human nature, the result is a fascinating literary journey into the past.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The Italian Renaissance introduced—or reintroduced—many valuable concepts to society and culture, giving rise eventually to our modern world. But it was also a time of fierce political infighting, social inequality, the subjugation of women, religious intolerance, belief in witchcraft, and many other elements that are more fun to read about than to experience. In The Road to Gesualdo, Erika Rummel draws on her years as a historian of the sixteenth century to bring this captivating story to life.

When Leonora d’Este, the daughter of the powerful family running the Italian city-state of Ferrara, receives orders from her brother to marry Prince Carlo of Gesualdo, she accepts the arranged match without protest. Her lady-in-waiting, Livia Prevera, does not. Prince Carlo, Livia argues, must have a secret, because the courtiers of Ferrara get quiet whenever his name comes up. Only after the wedding ceremony does Leonora discover that Livia is right. Prince Carlo murdered his first wife and her lover after finding them in bed together, his legal right at the time but an act committed with sufficient savagery to cast doubt on his mental health.

At first, Carlo and Leonora establish a bond through their love of music, but as time goes on, Livia becomes ever more concerned about a series of threats to her own health and, by extension, the future of those she cares about. Meanwhile, Pietro, the man she loves but cannot marry due to poverty on both sides, has been sent to Rome on a mission for Leonora’s brother: to discover whether the Gesualdo family really holds the power the d’Este clan expects and requires. Part of Pietro’s mission involves an arranged marriage with the daughter of a wealthy diplomat. Surrounded by plots and treachery, Livia and Pietro struggle to balance the demands of love, loyalty, and practicality—always hoping that fate will bring them together once more.

Image: Sixteenth-century portrait of Carlo Gesualdo by an unknown artist, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on July 31, 2020 06:00

July 24, 2020

Taking a Vacation

In normal years, July and August are prime time for summer vacations. Thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic, that is not the case in 2020, but I hope all of you can nonetheless find some room for relaxation amid the lockdowns and quarantines.

In normal years, July and August are prime time for summer vacations. Thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic, that is not the case in 2020, but I hope all of you can nonetheless find some room for relaxation amid the lockdowns and quarantines.For myself, the summer is prime writing time: with a week or two free of constant work-related demands, I can ease into the company of a new set of characters. The end of a workday can be productive in terms of revisions—as are weekends, especially the three- and four-day variety. But there’s nothing like an uninterrupted span of days to get the creative juices flowing. Characters come alive, start nattering in my head at night, and direct the plot in previously unimagined ways that spark new directions and possibilities.

Yet neither of those kind of vacations is the subject of this post. One often overlooked but invaluable tool in producing a finished book is to set a full draft aside for a couple of months, then go back to it with fresh eyes. Complicated explanations, twisty plot points, and characters who suddenly react in a way that is entirely out of character—all these flaws become visible after a writer creates enough space between the world inside her head and the response from a reader whose ability to understand inevitably depends on what actually gets onto the page.

By taking a break, the writer becomes that reader. I’m going through this process now with Song of the Sisters, the third novel in my Songs of Steppe & Forest series, and it’s a wonderfully rewarding experience. Unlike Songs 4, which exists in the ether and requires me to capture it with the author’s equivalent of a butterfly net, Songs 3 has a beginning, a middle, and an end; a protagonist and antagonist(s); a character arc. It’s been read by knowledgeable readers and critiqued from start to finish. I would have sworn it was done except for some last-minute vetting of the wording to avoid repetition and anachronisms.

By taking a break, the writer becomes that reader. I’m going through this process now with Song of the Sisters, the third novel in my Songs of Steppe & Forest series, and it’s a wonderfully rewarding experience. Unlike Songs 4, which exists in the ether and requires me to capture it with the author’s equivalent of a butterfly net, Songs 3 has a beginning, a middle, and an end; a protagonist and antagonist(s); a character arc. It’s been read by knowledgeable readers and critiqued from start to finish. I would have sworn it was done except for some last-minute vetting of the wording to avoid repetition and anachronisms. But coming back to it, I can see that it’s not. I’m finding plot points that don’t connect to those around them, character reactions left over from previous versions, doubled letters or meetings or conversations where one would serve just as well. And that’s not counting the few problems that the fine folks in my writers’ group already picked up but I held off on entering until I had time to read the whole.

It’s a fun exercise and, I hope, will lead in the end to a better book. If you’re a writer who rushes to publish, I strongly recommend that you too take a break in the middle. After all, what’s the worst that can happen? If your novel was perfect to start with, it won’t become less perfect over time.

But few novels are perfect at the end of the rough draft—or even the fourth draft. For those that aren’t, a vacation or two can work wonders.

And because it’s July, and with the help of our wonderful Five Directions Press cover designer, Courtney J. Hall, we now have a final cover for Song of the Sisters that I not only love but that reflects a crucial incident in the story, here is my “Christmas in July” cover reveal. The book itself should be available in January 2021.

Well, unless I make good use of that Christmas vacation …

And if you need a book cover (romance preferred, whether historical, romantic suspense, contemporary, or other), you can find Courtney’s terms and portfolio at The Magenta Quill.

Images: cat on beach purchased on subscription from iClipart.com; butterfly public domain via Wikimedia Commons; cover design property of C. P. Lesley, Courtney J. Hall, and Five Directions Press.

Published on July 24, 2020 06:00

July 17, 2020

Bookshelf, Summer 2020

Heather Bell Adams,

The Good Luck Stone

(Haywire Books, June 2020)Yet another WWII novel, but this one’s twist is that it begins with Audrey, a ninety-year-old woman still living semi-independently in her Savannah mansion. Her family hires a part-time caretaker, Laurel, and the two women establish a rapport—until Audrey disappears. Only then does it gradually become clear that Audrey has harbored a secret since her years as a nurse in the South Pacific and needs to face the truth to find peace. I’ll feature Heather Adams’ answers to my questions on this blog in early fall, but you can find the book already on Amazon; it came out last month.

Heather Bell Adams,

The Good Luck Stone

(Haywire Books, June 2020)Yet another WWII novel, but this one’s twist is that it begins with Audrey, a ninety-year-old woman still living semi-independently in her Savannah mansion. Her family hires a part-time caretaker, Laurel, and the two women establish a rapport—until Audrey disappears. Only then does it gradually become clear that Audrey has harbored a secret since her years as a nurse in the South Pacific and needs to face the truth to find peace. I’ll feature Heather Adams’ answers to my questions on this blog in early fall, but you can find the book already on Amazon; it came out last month.

Elsa Hart, The Cabinets of Barnaby Mayne (Minotaur Books, 2020)A departure—perhaps better characterized as a sidestep—from Jade Dragon Mountain and its sequels, a series I love. Here Hart, a young and talented mystery writer with a real gift for laying out the clues yet surprising me anyway, follows one of her characters west and back in time, to Queen Anne’s London in 1703.

Sir Barnaby Mayne, a noted collector of pretty much any bizarre object he can lay his hands on, is found stabbed in his study. His curator confesses to the crime, and the authorities are happy to let it go. Even the dead man’s widow asks no questions, but Lady Cecily Kay and her childhood friend Meacan Barlow are determined to find out the truth, even when the quest places their own lives at risk. I’ll be talking with Hart on New Books in Historical Fiction in early August.

Laurie R. King,

Riviera Gold

(Bantam, 2020)In this latest installment of another historical mystery series that I love, Sherlock Holmes and his much younger wife, Mary Russell, travel to the French Riviera, not far from Monte Carlo. There they re-encounter their housekeeper, Mrs. Hudson, who left England under a cloud a few books back and, lo and behold, has managed to attract new trouble to herself.

Laurie R. King,

Riviera Gold

(Bantam, 2020)In this latest installment of another historical mystery series that I love, Sherlock Holmes and his much younger wife, Mary Russell, travel to the French Riviera, not far from Monte Carlo. There they re-encounter their housekeeper, Mrs. Hudson, who left England under a cloud a few books back and, lo and behold, has managed to attract new trouble to herself. The joy of this series is Mary—Sherlock’s match in intellect, daring, and courage—and her relationship with her aging husband. Although their interactions often seem more business-like than passionate (and involve an element of competition), Mary and Holmes are so perfectly matched that their love for each other is never in doubt. The book came out last month, and I’m just waiting for a gap in my reading schedule before tearing into it with glee.

Gill Paul,

Jackie and Maria

(William Morrow, 2020)I enjoyed this author’s The Secret Wife and The Lost Daughter, which told semi-fantastical stories about how two of the Romanov princesses might have escaped Bolshevik bullets and bayonets and in the process explored the lives of Russians who escaped the revolution and who didn’t.

Gill Paul,

Jackie and Maria

(William Morrow, 2020)I enjoyed this author’s The Secret Wife and The Lost Daughter, which told semi-fantastical stories about how two of the Romanov princesses might have escaped Bolshevik bullets and bayonets and in the process explored the lives of Russians who escaped the revolution and who didn’t. Here Paul turns her focus to Jackie Bouvier Kennedy and the opera star Maria Callas—united, if that’s the right word, by their sequential attraction to Aristotle Onassis, the Greek shipping magnate. These fascinating stories to some extent took place in the background of my childhood, although mostly in ways I didn’t recognize then. A Q&A with Gill Paul should appear on this blog around the middle of August, when William Morrow releases the book.

Bryn Turnbull,

The Woman before Wallis

(MIRA Books, 2020)It would be hard to grow up in the English-speaking Western world without at some point hearing about Wallis Simpson and how she convinced the English king Edward VIII to abdicate his throne to marry her, a divorced woman. But Wallis was merely the most successful of a string of lovers that Edward, known to his family and friends as David, maintained during his tenure as Prince of Wales.

Bryn Turnbull,

The Woman before Wallis

(MIRA Books, 2020)It would be hard to grow up in the English-speaking Western world without at some point hearing about Wallis Simpson and how she convinced the English king Edward VIII to abdicate his throne to marry her, a divorced woman. But Wallis was merely the most successful of a string of lovers that Edward, known to his family and friends as David, maintained during his tenure as Prince of Wales.This new novel, due out next week, follows the story of Thelma, Lady Furness, whose twin sister, Gloria, married Reggie Vanderbilt and gave birth to the fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt. Thelma, an American divorced at a young age, was delighted to attract the attention of Viscount Furness, even if marriage to him meant moving to a drafty estate in England and acquiring two stepchildren. But once she gets there, she learns that her husband thinks nothing of affairs with other women. When the Prince of Wales falls in love with her, Lord Furness steps aside, and their marriage slowly crumbles. When Thelma introduces Prince David to Wallis Simpson, that relationship suffers as well. But it’s the escalating conflict between Thelma’s sister and their mother that really forces Thelma to define what matters most. I finished this compelling story last week, but I include it here because I will interview Bryn Turnbull for New Books in Historical Fiction in mid-August.

Published on July 17, 2020 06:00

July 10, 2020

Interview with James Ross

I’ve been conducting a lot of author interviews recently, the happy result of having been offered more good books than I can reasonably fit into my podcast schedule. Today I’m featuring James Ross, whose historical novel

Hunting Teddy Roosevelt

is due for release at the end of July. It’s not exactly a mystery, in that we learn the identity of the intended killer and the reasons behind the assassination attempt against the former US president early on: the unknowns are rather how the crime will take place, if it does—and, since this is a novel instead of a history book—whether the would-be assassin will succeed.

I’ve been conducting a lot of author interviews recently, the happy result of having been offered more good books than I can reasonably fit into my podcast schedule. Today I’m featuring James Ross, whose historical novel

Hunting Teddy Roosevelt

is due for release at the end of July. It’s not exactly a mystery, in that we learn the identity of the intended killer and the reasons behind the assassination attempt against the former US president early on: the unknowns are rather how the crime will take place, if it does—and, since this is a novel instead of a history book—whether the would-be assassin will succeed.There are contemporary overlaps to Ross’s story as well. Teddy Roosevelt’s decision to wipe out as much African wildlife as possible for the sake of the Smithsonian Institute and New York’s Natural History Museum now seems both ecologically disastrous and (unwittingly) offensive in its approach to what we now call the Third World. And as we discuss at the end of the interview, in the wake of the recent protests in the United States, the same Natural History Museum has removed its commemorative statue to Roosevelt because of its colonialist elements.

But the only way to overcome the shortcomings of our past is to face them, and the fact that these problems continue to exist in our present make this novel even more of a necessary and compelling read. So read on to find out more. Some of the answers may surprise you.

You have an interesting history. How did you come to write fiction?

I wrote my first book in college. I’m publishing my first one, Hunting Teddy Roosevelt, the same year I start to collect social security. It’s been a long haul. One of the reasons it took so long is that the common (and often only) advice given to new writers when I was starting out was to follow Hemingway's dictum: “Begin with one true sentence.” I did and, over the next decade, wrote a trunk full of manuscripts before realizing that without plot, characterization, drama, and other fundamentals of good storytelling, several hundred pages of true sentences are unreadable and unpublishable. Fortunately, and with the help of an excellent writing group called NovelPro, I finally learned the basic blocking and tackling of fiction and have made steady progress since then.

And what made you want to tell a story about Teddy Roosevelt, especially in the year after he stepped down from the presidency?

Quite by accident, I came across a 1909 Italian newspaper that contained an account of the arrest of an anarchist who had allegedly attacked Roosevelt with a knife while he was traveling by ship to Europe on his way to Africa. Today, we’re all too familiar with attempts to kill office seekers and office holders, but in 1909 Roosevelt was out of power and on his way to a part of the world that routinely killed 80% or more of the reckless adventurers who went off to challenge its jungles and deserts. So this obscure Italian newspaper account of a shipboard attempt on Roosevelt’s life raised some interesting questions. Among them: Why would someone go to the trouble of trying to kill an ex-office holder on his way to some place that was likely to kill him anyway? Who would do it? And how did an attempt to kill Teddy Roosevelt not make it into any American newspaper, history book, or Roosevelt biography? Was the story suppressed? And if so, by whom and how?

Hunting Teddy Roosevelt is a fictional attempt to answer these questions. And while I’m not a historian, I hope my book gives professional historians a decent head start on an intriguing mystery.

Why has Roosevelt gone to Africa, and what is he leaving behind?

Honoring George Washington’s precedent of declining to run for a third consecutive term, Roosevelt left office in March 1909 and turned the presidency over to his successor, William Howard Taft, with the promise to stay out of the public eye for a year to give Taft a chance to be his own man. To keep that promise, Roosevelt left America to lead the largest African safari ever assembled: 260 men and 20 tons of supplies and equipment, with the objective of gathering specimens of African game animals for the Smithsonian and New York Museum of Natural History.

Unknown to Roosevelt, the Smithsonian raised much of the safari’s funding from J. P. Morgan, the richest private citizen of that era. Morgan was happy to underwrite the cost of keeping Roosevelt out of the country for a year if that would give him time to work with the more business-savvy Taft administration to undo Roosevelt’s anti-business legislation. Morgan’s toast on TR’s departure was a pithy (and revealing): “America expects every lion to do its duty.”

Roosevelt was a larger-than-life character in an age that spawned more than its share: hero of the Spanish American War for leading a band of Badlands cowboys on a daring cavalry charge up San Juan Hill, Cuba; police commissioner of the City of New York, responsible for ending rampant police corruption and breaking the grip of Tammany Hall on New York politics; at age forty-three, the youngest president of the United States—who dismantled monopolies in railroad, oil, and other industries; won the Nobel Peace Prize for brokering an end to the Russo-Japanese War; and used a “speak softly but carry a big stick” foreign policy to ignite a revolution in Panama that secured for the United States the right to build a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

But Roosevelt’s aggressive style and controversial accomplishments created enemies as well as admirers, and first among them was J. P. Morgan. Morgan blamed Roosevelt’s assault on business monopolies (then known as trusts) for triggering the stock market panic of 1907 that nearly destroyed the country’s financial system. The Federal Reserve Bank did not then exist, and only Morgan’s daring use of his entire personal fortune to prop up the largest failing banks saved the country from financial collapse. The US economy had become as strong as any in Europe, but it was vulnerable to periodic booms and busts. Morgan’s view was that if the country was to realize the promise of its natural advantages, it must have modern and efficient business structures: a national bank, a national railroad, and an end to wasteful competition in basic commodities. Europe was once again headed toward war, and if America could avoid entanglement, it would have a chance to fulfill its destiny as the dominant global power with all the attendant rewards. But only if it could get its economic house in order; and only if that madman, Teddy Roosevelt, could be kept permanently away from the throttles of power.

Somewhere in that mix is the answer to the questions of who, why, and how?

On the trip, he runs into a childhood sweetheart—indeed, his first love, Maggie Dunn, an intrepid newspaper reporter who reminded me of Nellie Bly. What causes her to accept this assignment?

Maggie is a serious journalist, and she wants to cover serious stories—like the resurgence of slavery in the Sudan, Belgian colonial atrocities in the Congo, and German preparations for war in East Africa. But she has to make a living. To do that, she takes on an assignment for the sensationalist Hearst newspapers (the Fox News/National Enquirer of its time) to cover the colorful ex-president’s gargantuan safari as a means of getting her to Africa and paying her expenses while she pursues her serious journalism.

And what can you tell us about Jimmy Dooley?

Jimmy Dooley is a fictional character, loosely based on my paternal grandfather, an uneducated Irish tough who lived by his wits in the hardscrabble environment of turn-of-the-century New York. He had a brief career as a professional boxer, fighting under the name Tiger Ross. I only knew him later in life, but even in his 70s, he was as hard as a floor, with lean, ropy muscles and a permanent scowl. If he told you to hand over your wallet, you’d do it fast, no questions asked.

Teddy Roosevelt has been in the news lately because of the New York Museum of Natural History’s decision to take down his statue. Do you see any connection between this decision and your novel?

If Teddy Roosevelt was alive today, he’d help pull down that statue. He hated the idea of monuments to politicians. In fact, it was his expressed wish (ignored after his death) that no statue or other monument be erected of him. The one outside the New York Museum of Natural History is appalling: TR astride a whacking great horse with supplicant African and Native Americans below. TR would have been outraged and embarrassed.

This book has just come out. Are you already working on something new?

Yes! I’ve just signed a three-book contract with the mystery publisher Level Best Books. The first novel, Coldwater Revenge, is about two brothers involved with the same woman and the problems that ensue when they discover she’s a murderess and one brother begins to suspect the other of helping her cover it up. It’s due out in April 2022. The second and third books in the series should come out in April 2023 an 2024, respectively.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

James Ross has been at various times a Peace Corps volunteer, a Congressional staffer, and a Wall Street lawyer. His short fiction has appeared in numerous literary publications, he has appeared as a guest storyteller on the Moth Main Stage, and his short story “Aux Secours” has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He is a frequent contributor to, and occasional winner of, the Jackson, Wyoming, live storytelling competition, Cabin Fever Story Slam. Find out more about him at http://jamesrossauthor.com.

Published on July 10, 2020 06:00

July 2, 2020

Interview with Eliot Pattison

As we get ready to celebrate the birthday of the United States of America—just six years short of its 250th anniversary—it might be good to revisit what came before. On this day, July 2, a group of rebels met in Philadelphia and signed the Declaration of Independence drafted by Thomas Jefferson. (For those who may not know, the signing was made public two days later, which is why Independence Day falls on July 4.)

As we get ready to celebrate the birthday of the United States of America—just six years short of its 250th anniversary—it might be good to revisit what came before. On this day, July 2, a group of rebels met in Philadelphia and signed the Declaration of Independence drafted by Thomas Jefferson. (For those who may not know, the signing was made public two days later, which is why Independence Day falls on July 4.)The discontent among the colonists went back many years. The King’s Beast , the latest installment of Eliot Patterson’s Bone Rattler series, starts in 1769. Duncan McCallum, the hero of the series, has traveled to the Kentucky wilderness on a commission from Benjamin Franklin: to unearth a set of giant bones found in a mud pit and convey said bones to London. But a triple murder at the excavation site leads Duncan along a twisted path of deceit, revenge, and betrayal that affect not only himself but the Sons of Liberty, the underground revolutionary organization to which Duncan belongs.

One of the elements that make Duncan appealing is that he—and several other major characters in the series—have deep ties to the Native American and black (both slave and free) populations. In this sense, although he still considers himself a loyal subject of the English king, he is already occupying a different cultural and emotional space. Unlike many of his compatriots, Duncan and his friends welcome the complexities of that space.

Given the centuries-long history of racism and oppression in this country, which has tarnished the bright dreams of liberty and justice for all, it is reassuring to encounter a hero who understands that it takes more than one kind of person to build a nation. Eliot Pattison was kind enough to answer my questions about Duncan and his world. Please read on to find out more.

This is the sixth novel in your Bone Rattler series. What made you decide to write a mystery series set in the years leading up to the American Revolution?

Americans are alarmingly disconnected from their history, which perhaps is no wonder given the sterile way it is presented in our textbooks and most classrooms. In many ways these years before the outbreak of war were the true period of revolution, for this is the time of our extraordinary shift in self-identity, when the inhabitants of these shores began to think of themselves not as British colonists but as Americans. This was one of the most extraordinary periods of our past, when advancements in education, printing, and science were liberating people like never before. The period offers profound lessons for today, and I am convinced that when done well historical fiction can connect readers with the past much more effectively than any textbook. Reducing the complex humans of our past to shallow soundbites and classroom statistics diminishes ourselves as much as them. We need to grasp that except for differences in technology and material possessions, these people of the eighteenth century shared many of the same ambitions, appetites, frustrations and conflicts that we have today. This series not only allows me to make this vital period more relatable to readers, it offers them hands-on involvement with the birth of our country.

What specifically drew you to the story that became The King’s Beast?

My novels in this series are all built around authentic elements of the period—for example, the Stamp Tax, the repression of the native tribes, slavery, and the legacy of the bloody French and Indian War. This installment draws upon the wave of scientific discovery occurring during this time and the widespread effect of the nonimportation pacts which arose in reaction to London’s repressive restrictions on trade. I immerse myself in research before launching into a novel, and I was amazed at the remarkable events of 1769, including the opening of the Kentucky lands with their fabled bones of a mysterious beast, and the fierce competition between Philadelphia astronomers and the king’s royal scholars over the transit of Venus—all of which become plot elements in The King’s Beast.

Your main character is Duncan McCallum. He’s a Scotsman, an émigré. How did he end up in Pennsylvania, and how would you describe him as a character. What does he want in life?

Duncan McCallum was about to complete his medical education in Edinburgh when he was falsely arrested for supporting Jacobite traitors and put in chains for transportation to America as an indentured servant, effectively a form of slavery that was a common punishment for Scots who offended the government. Duncan is thrust into the frontier of New York and Pennsylvania, in the shadow of the fearsome wilderness, which everyone knows is populated by bloodthirsty savages. Duncan is forced into fearful confrontation with the natives, and to his surprise he finds them to be quite the opposite of the image portrayed in public accounts—in fact they remind him of his own compassionate, spirited Highland relatives. As he faces crisis after crisis, eventually using his skills to solve murders of colonists and natives which would otherwise be ignored by the government, he develops a profound respect for the tribes and begins to experience the unfamiliar freedom that the American lands seem to breed. Despite his legally imposed servitude Duncan cultivates that independence, and eventually experiences the complexities, and burdens, of colonial freedom as he is drawn into the affairs of the Sons of Liberty.

When we meet him in this novel, Duncan is searching for something known to those on his expedition only as the incognitum. Why are they looking for it, and how does their discovery lead to murder?

During the late 1760s accounts of the remains of a mysterious creature in the Kentucky lands are stirring excitement and controversy in both colonial towns and Europe. Benjamin Franklin, now in his long tenure as colonial envoy in London, has devised a plan to use the remains of this incognitum to elevate the colonial cause with the king, if someone can just perform the impossible task of secretly bringing them to him in London. Duncan reluctantly accepts this challenge and only when he arrives at the other-worldly Bone Lick of Kentucky does he discover that clandestine agents from London will stop at nothing, not even murder, to prevent him from getting the bones to Franklin.

In pursuit of the murderers, Duncan heads for Philadelphia, where he reconnects with Sarah Ramsey, the woman he loves. Like Duncan, she has links to the Iroquois, although that is only part of her story. What can you tell us about her?

Like all my primary characters, Sarah Ramsey is an amalgam of authentic figures of the period. The daughter of the wealthy London aristocrat who owns Duncan’s bond of indenture, Sarah was captured as a young girl and raised by the Iroquois, then in her late teen years was forced against her will to return to European society—reflecting the actual experience of a number of captives. Like Duncan, Sarah is fiercely independent. The two resist the forces of British society, and as they help each other recalibrate their lives their affection for one another grows. She forces her father to surrender Duncan’s ownership to herself and together they start building the community of Edentown, a frontier refuge for orphans and outcasts. Sarah remains deeply loyal to the Iroquois but, like Duncan, is drawn into the cause of American independence, hoping that driving out the British government will help preserve the tribes. By the time of this sixth installment Sarah has taken on a leadership role in the nonimportation resistance movement, a role so secret that not even Duncan knows of it—until he learns that she too has been targeted for death by spymasters in London.

Duncan belongs to the Sons of Liberty. What does that mean in 1769, and what does it have to do with Duncan’s journey to London?

Although the Sons of Liberty were formed to oppose the Stamp Tax of 1765, as London imposed new repressive measures on the colonies, the Sons revived and by 1769 were coordinating across colonial borders to advance their goals. Duncan has served as a secret emissary of the Sons on the frontier and is valued for his knowledge of the wilderness and the tribes. When Benjamin Franklin cryptically requests that the Sons retrieve the ancient bones for the colonial cause in London, Duncan is their obvious choice. Little does he know that this path will lead to murder and mayhem, and mark him for death.

This book came out in early April. Are you already working on something new?

There will be a seventh book in the series, set in the tumultuous year of 1770, when the Boston Massacre occurs. Meanwhile I am working on a new, more contemporary series.

An international lawyer by training, Pattison is the author of the Inspector Shan series, which includes ten novels—beginning with the award-winning The Skull Mantra. His longtime interest in eighteenth-century America, including its woodland tribes, gave rise to his Bone Rattler series, of which The King’s Beast is the sixth installment. Ashes of the Earth, a stand-alone post-apocalyptic mystery, appeared in 2011. He resides on an eighteenth-century farm in Pennsylvania with his wife, son and an ever-expanding menagerie of animals. Learn more about him at http://www.eliotpattison.com.

Image credit: Jerry Bauer.

Published on July 02, 2020 06:00

June 26, 2020

That Which Survives

Janie Chang’s latest novel discusses many important topics—some familiar, some less so. One of the reasons I wanted to interview the author, in fact, was precisely because it approaches well-known territory from a new and interesting angle. On the surface,

The Library of Legends

is a book about war: the Japanese occupation of China in the years leading up to World War II, in particular. Beneath the surface, though, it touches on a much broader range of issues both personal and political.

Janie Chang’s latest novel discusses many important topics—some familiar, some less so. One of the reasons I wanted to interview the author, in fact, was precisely because it approaches well-known territory from a new and interesting angle. On the surface,

The Library of Legends

is a book about war: the Japanese occupation of China in the years leading up to World War II, in particular. Beneath the surface, though, it touches on a much broader range of issues both personal and political.The basic premise is simple. A university in Nanjing decides to evacuate its students to protect them from the advancing Japanese army. In their baggage, each of them carries a single volume of an ancient encyclopedia. Their assignment is to convey their individual volume to its destination, a thousand miles to the west—but also to read it along the way and master its contents. Because the encyclopedia encapsulates the folklore of their nation: its heritage.

On this foundation, Janie Chang deftly weaves together themes of friendship and treachery, a murder and an arrest, a love story spanning centuries, the bonds of mother and daughter, even the involvement of spiritual forces. It sounds like it couldn’t work, yet it does.

But most of all, this is a novel about literature and legends—about books, what their survival mean to us as individuals and as cultures. In the midst of today’s pandemic and unrest, which can seem so overwhelming, it is worth remembering that ours is not the first generation to face such crises, nor—barring some unimaginable catastrophe—will we be the last. So let us protect our own Library of Legends, the essence of our culture, for those future generations.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Perhaps in anticipation of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the armistice, or just the reality that the last survivors will not be with us much longer, World War II has dominated the genre of historical fiction for some time. But two years before Hitler’s aggression against Poland set off the conflagration in Europe, imperial Japan occupied China, capturing Shanghai and Nanjing before launching bombing forays westward.

In The Library of Legends, Janie Chang draws on family stories and ancient legends to weave a fact-based yet mystical tale about this period in China’s long history. The novel focuses on a group of university students evacuated from Nanjing as the Japanese army approaches. Eager to defend their cultural heritage, the students embrace the task assigned to them: safeguarding an encyclopedia of lore compiled during the early Ming dynasty five hundred years before.

Hu Lian, a scholarship recipient from a single-parent family, encounters Liu Shaoming and his enigmatic former servant, Sparrow Chen, just as the students are starting on their long and difficult journey west. Friendship, even romance, blossoms between Lian and Shao—a love she does not trust because he comes from a background far wealthier than her own. But after a communist student agitator is murdered and suspicion falls on another of Lian’s friends, it is Shao and Sparrow who support Lian as she leaves the convoy to search for her mother. Only on the road east does Lian realize that the volume of the Legends entrusted to her includes a tale that may illuminate not only the elusive connection between her traveling companions but the destiny of China itself.

Published on June 26, 2020 06:00

June 19, 2020

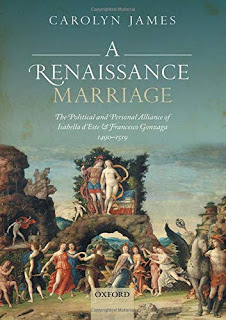

Interview with Carolyn James

Although I mostly write historical fiction these days, I am still a historian specializing in the early modern period (1500–1800), especially Russia. And as you may have noticed, most of my novels revolve around political marriages: young men and women pushed into them or striving to avoid them while their elders bend heaven and earth to arrange them. So it is no surprise that when I heard about Carolyn James’ new study

A Renaissance Marriage: The Political and Personal Alliance of Isabella d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga, 1490–1519

(Oxford University Press, 2020), I wanted to know more—not least because this book is based on something that historians of Russia cannot count on until at least the 1700s: a decades-long correspondence between husband and wife.

Although I mostly write historical fiction these days, I am still a historian specializing in the early modern period (1500–1800), especially Russia. And as you may have noticed, most of my novels revolve around political marriages: young men and women pushed into them or striving to avoid them while their elders bend heaven and earth to arrange them. So it is no surprise that when I heard about Carolyn James’ new study

A Renaissance Marriage: The Political and Personal Alliance of Isabella d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga, 1490–1519

(Oxford University Press, 2020), I wanted to know more—not least because this book is based on something that historians of Russia cannot count on until at least the 1700s: a decades-long correspondence between husband and wife.As often happens with academic books, my first search resulted in sticker shock. But the advantage of reviewing books is that publishers often send them free of charge, so I pursued this angle. My initial plan to interview the author for New Books in History, another podcast channel on the New Books Network, foundered on the reality of a fifteen-hour time difference, so I persuaded the author (who was actually willing, bless her heart, to get up at the crack of dawn to talk with me) to answer written questions instead.

So read on. This is not exactly the world behind my Legends novels, although Juliana and Felix, in Song of the Siren, would definitely feel quite at home. But even at a distance of fifteen hundred miles, there are principles operating here that my characters would recognize. After all, the second wife of Ivan III of Russia, Sophia (Zoë) Paleologina, left Italy, where she had grown up, to marry him in 1472. And she brought with her not only scholars and diplomats but those artists and architects whose work we can still see in the Moscow Kremlin.

Not such a great gulf after all!

So tell us, who were Isabella d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga, and what do we most need to know about them?

Isabella d’Este (1474–1519) was the eldest child of Ercole d’Este, duke of Ferrara (r.1471–1505), and of the Neapolitan princess Eleonora d’Aragona (1450–1493). Francesco Gonzaga (1466–1519) was heir to the neighboring marquisate of Mantua. The betrothal of Francesco and Isabella in 1480 continued a tradition whereby the Este and Gonzaga rulers married women from more illustrious families than their own. By doing so, they aimed to improve their bloodlines while bolstering their hold on power by forming alliances with major political dynasties. However, whereas in the previous two generations the Gonzaga had looked to Germany in their search for suitable brides for the future ruler, the third marquis, Federico Gonzaga, decided to strengthen relations with the neighboring duchy of Ferrara by agreeing to a match between his fourteen-year-old son, Francesco, and the duke’s six-year-old daughter, Isabella. The couple married in early 1490, after a decade-long betrothal.

Federico Gonzaga’s death in 1484 thrust Francesco into power at a young age. His mother had already died in 1479. During the remaining six years of the betrothal, Isabella’s parents encouraged their future son-in-law to spend long periods in Ferrara. They attempted to fill the emotional void that Francesco experienced in the aftermath of his parents’ death. The alliance between Ferrara and Mantua therefore became very close.

The political partnership of Isabella and Francesco was by no means unique. There were similar collaborations in earlier generations of their families. The duchess of Ferrara, Eleonora d’Aragona, supported her husband’s regime by taking charge of diplomatic relations with her Aragonese relatives and acting as Ercole d’Este’s occasional regent. Francesco’s mother, Margaret von Wittelsbach of Bavaria, and particularly his grandmother, Barbara of Brandenburg, who lived until 1481, also played important diplomatic and administrative roles. Isabella was carefully educated to ensure she would be able to do the same. The stark differences in literacy and levels of education between husband and wife that characterized most premodern marriages did not exist in that of Isabella and Francesco, or indeed in those of their immediate forebears. The letters exchanged by the couple show how well matched they were in terms of cultural sophistication and political acumen. My book explores the consequences of this parity in a marriage that was still subject to conventional notions about a husband’s absolute authority over his wife.

And what got you interested in them as subjects of your research? How did you discover their correspondence?

And what got you interested in them as subjects of your research? How did you discover their correspondence?Scholars have long been aware of the existence of correspondence between Isabella d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga. The late nineteenth-century archivist and antiquarian Alessandro Luzio used some of the couple’s letters in his many studies of Isabella, which characterized Francesco as a crude and violent soldier who did not deserve such a peerless wife. This exaggerated interpretation is not supported by the evidence.

The letters exchanged by Isabella and Francesco over the twenty-nine years of their marriage survive in many separate files of the Gonzaga archive. I became interested in the couple’s correspondence while I was working in the State Archive of Mantua on the Bolognese literary figure Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti. He wrote a collection of biographies of famous women modeled on Giovanni Boccaccio’s De Claris mulieribus (Concerning Famous Women). Boccaccio’s work, written in about 1360, focused on ancient classical heroines. In Gynevera de le clare donne (Ginevra among the Famous Women) Arienti wrote mostly about women near to his own time, many of them from Italy’s political dynasties. He sent Isabella d’Este a copy of his work in 1492. She was pleased by the gift, which showcased the virtue, political competence, and intelligence of women who, like her, were active in the public sphere. The biographies pushed back against an entrenched clerical tradition of misogyny, which insisted that the female sex was innately weak, prone to sin and unfit for political responsibilities of any kind. Arienti’s literary offering initiated a warm relationship with the marchioness in which she accepted him as a client who supplied her with regular political and other news that came his way in Bologna.

In searching for Isabella’s replies to Arienti’s letters, I became aware of the magnitude of her correspondence with Francesco. After a thorough search, I discovered that three thousand of the couple’s exchanges were extant, many of them in more than one copy. Outgoing letters were recorded before dispatch, and the originals were brought back by the couple’s secretaries for filing in the chancery once they had been read by the recipient. Thus almost the entire correspondence exists in one form or another—a very rare occurrence, even in modern times. It struck me that the letters were a unique record of the evolution of an elite marriage. The collection spoke of so many aspects of the couple’s lives and, although nearly all the letters were dictated to secretaries and were therefore not private documents, they nonetheless revealed an extraordinary range of the emotional currents that ran through this politically charged relationship and how those feelings changed over time.

Both Isabella and Francesco grew up in households where women played powerful political roles. For readers who may not expect that of Renaissance Europe, explain how that happened.

Isabella and Francesco came from families which had established their political dominance in the late medieval period through force of arms. The rulers of Mantua and Ferrara remained soldier-princes and earned much needed extra income by fighting as military captains for wealthier states such as the duchy of Milan and the republic of Venice. With economies that were mainly agriculturally based, taxation levied on crops, tithes paid by craft traversing the river Po, and imposts on commodities crossing their borders were simply not sufficient to fund the lavish courts and magnificent cultural patronage of the Este and Gonzaga princes.

Isabella and Francesco came from families which had established their political dominance in the late medieval period through force of arms. The rulers of Mantua and Ferrara remained soldier-princes and earned much needed extra income by fighting as military captains for wealthier states such as the duchy of Milan and the republic of Venice. With economies that were mainly agriculturally based, taxation levied on crops, tithes paid by craft traversing the river Po, and imposts on commodities crossing their borders were simply not sufficient to fund the lavish courts and magnificent cultural patronage of the Este and Gonzaga princes.The Gonzaga and Este rulers preferred to have their wives act as regents while they were on the battlefield, bitter experience having shown that male relatives were likely to use the temporary absences of the reigning prince to usurp power for themselves. A female consort had an investment in power devolving to her children and was therefore a far more trustworthy political lieutenant than a ruler’s younger brother or uncle.

Isabella, when she married, was fifteen, and Francesco a young man of twenty-three. How did that age difference affect the early years of their marriage?

The eight-year age difference that separated Isabella and Francesco would have been perceived by their contemporaries as unremarkable, indeed far less than the marital norm. In the republic of Florence, for example, it was common for forty-year-old men to marry girls of sixteen. Age difference between prospective partners was not a significant consideration for parents thinking about prospective matches, although the capacity of a woman to bear children was. Girls usually married when they reached physical maturity. The Gonzaga pressed for the wedding of Francesco and Isabella to take place when the latter was twelve. Eleonora refused to contemplate this possibility on the grounds that her daughter was too young and her health too delicate for such a profound change in her life. The duchess made various excuses to delay the wedding until Isabella was a few months short of sixteen. Even so, there is evidence that Isabella experienced the early phase of marriage as a physical and emotional trauma. She suffered acutely from homesickness and was terrified of becoming pregnant for fear of dying in childbirth, a fate she well knew took many young women to an early grave.

The Este and Gonzaga parents were proactive in trying to kindle love between their betrothed children. In the early years, the age gap between them yawned significantly, separating a coddled little girl from an adolescent man already sexually active and interested in vigorous outdoor sports. It took some years for the pair to bond after marriage, but eventually they did so.

Despite those initial difficulties, they succeeded in developing a functional political and personal partnership. What does their correspondence reveal about that process?

Although Isabella was slow to adapt to the emotional and procreative expectations of marriage, letters to Francesco show that she was far more forthcoming in embracing a political role. Francesco was pleased by her readiness to take on administrative duties and he gradually permitted her to help him more often.

The failure to produce a male heir during the first decade of marriage was a source of great anxiety for Isabella. Francesco was more relaxed, the birth of two daughters, the second of whom died in infancy, reassuring him that his wife was fertile and that a boy would eventually come along. The joy with which he greeted the birth of Federico in May 1500 suggests that he too may have been growing worried as the years rolled by with no heir to secure the Gonzaga succession.

The period between 1500 and 1506 were golden years in the couple’s relationship as their political collaboration prospered and their family grew. By 1508, they had produced eight children, although only six survived to become adults. Their correspondence documents the pleasure they took in bringing up their children, but also the satisfaction they took in working together politically. Against all the odds, the Gonzaga regime survived the early decades of the Italian Wars, an achievement due in no small part to canny strategizing by Francesco and Isabella who coordinated a campaign of double diplomacy to cultivate the protagonists of both sides of the conflicts.

In the end, though, they grew apart again. Why?

When their children were young, Francesco and Isabella had taken mutual delight in the joys of parenthood, especially savoring the satisfaction of having produced a male heir who in their view was both unusually intelligent and completely charming. The success of their biological collaboration was a source of comfort and pride in a period that witnessed a steady worsening of the Italian political scene. The couple cooperated cannily to deflect the dangers to the regime posed by the Italian Wars, with Francesco serving as a military commander during the early phase of the conflicts, and Isabella keeping the home fires burning with competence and persistence.

However, Francesco’s military career declined swiftly after 1508, when the symptoms of the Great Pox became so invasive and debilitating that, not only was he was unable to fight, but he had to retreat from public view by leaving his apartments in the Gonzaga castle to live in seclusion at a palace on the edge of the city. Here he was subjected to painful and ultimately futile treatments with only a small number of chancery bureaucrats to help him govern. It was Francesco’s secretary, Tolomeo Spagnoli, who now collaborated with him politically, not Isabella.

The couple had already experienced misunderstandings, and there were many earlier squabbles. However, Francesco’s isolation and the suffering imposed by his illness made him far more irritable and autocratic. Marital tensions became more frequent. During a brief period of remission in 1509, Francesco attempted to take to the battlefield in support of the French king, Louis XII. However, he was almost immediately captured and imprisoned by mercenaries in the employ of Venice. Isabella ruled Mantua during her husband’s captivity and negotiated doggedly for his release, which she secured by permitting the pope to take their ten-year-old son Federico into his care as guarantor of the pact that freed Francesco from captivity. Isabella expected to be able to build on the experience she had accumulated during the crisis created by her husband’s imprisonment in Venice. Instead, she was sidelined again. In the last years of the couple’s marriage, the marchioness spent long periods in Milan and Rome in protest at her political marginalization. Although she and Francesco occasionally recovered some of their former camaraderie in letter exchanges that expressed affection and sympathy for the other, the couple mostly lived separate lives. Cordial letters alone were not able to compensate for the lack of routine domestic contact that the couple had experienced when they lived in adjoining apartments within the Gonzaga castle.

What can we learn from their experience about political marriages more generally?

Political marriages were organized to cement strategic alliances, but the lack of consideration given to the personal compatibility of a prospective couple meant that the objectives of such unions were often not realized. Indeed, antipathy between a married couple could create serious diplomatic tensions between the regimes supposedly brought together by the union.

My book explores the ways in which the Gonzaga and Este parents attempted to foster amiable relations between their betrothed children in the long prelude to their marriage so the pair would eventually form a loving and cooperative bond. Francesco and Isabella continued the efforts of their parents and consciously strived to cultivate marital affection, especially through their shared enthusiasm for, and love of, their children. Few sources are as complete and richly evocative in revealing the internal dynamic of a premodern marital relationship as the correspondence between Isabella d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga.

And what of you? Does your new research project on the Italian Wars grow out of this one?

My current project does grow out of the study of the political and personal relationship of Isabella and Francesco, since all but four years of their marriage played out against the backdrop of the Italian Wars. This was a series of conflicts that began in 1494 with Charles VIII’s campaign to claim the kingdom of Naples from its Aragonese rulers and continued well beyond the end of the couple’s marriage in 1519. Francesco died that year from the Great Pox, likely contracted on the battlefield soon after the new disease appeared in Naples among French soldiers in the mid-1490s. It spread rapidly throughout Italy and then Europe. Francesco’s life was blighted by the disease, which at its worst rendered him an invalid, racked by intolerable pain and disfigured by disgusting open wounds.

The project on the Italian Wars examines not so much the military aspects of the conflicts which have been much studied, but rather their social, cultural, and political impact. The extreme violence experienced by the populations of Italy’s city states at the hands of the multiethnic mercenaries and their French and Spanish leaders was traumatizing for societies used to the idea that they could control their own political fate. The trophies of war that were ransacked from Italian cities, especially during the infamous sack of Rome in 1527, transported the fruits of the Italian Renaissance to many other parts of Europe, where they profoundly influenced local artistic and cultural traditions.

The political role that Isabella played during the first two decades of the conflicts, which saw the Gonzaga regime vulnerable to attack, especially after Francesco was taken prisoner by the Venetians and imprisoned for a year in 1509, was partly the result of extraordinary circumstances. However, similar crises thrust other elite women into major diplomatic and political roles. The project seeks to examine some of the themes of A Renaissance Marriage over a longer time frame and in various political contexts, not just in Italy but in Europe more generally.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Carolyn James is Cassamarca Associate Professor in the School of Philosophical, Historical, and International Studies at Monash University, Australia. She has edited the letters of the fifteenth-century Bolognese literary figure Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti and analyzed his literary works. With Antonio Pagliaro, she translated the late medieval letters of Margherita Datini. She has written on women's political and diplomatic roles in Renaissance Italy, as well as early modern women's relationship with letter-writing. She is presently engaged on a project focused on the Italian Wars, 1494–1559, with Professor Susan Broomhall and Dr Lisa Mansfield.

Images: Portrait of Francesco Gonzaga (n.d.); Isabella d'Este, by Titian (1535); Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, The Grand Captain after the Battle of Cerignola (Italian Wars, painted 1835)—all public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on June 19, 2020 06:00

June 12, 2020

Interview with Sara Ackerman

Seventy years after the end of World War II, it’s amazing how many new angles on the war writers are still discovering. Sara Ackerman, author of

Red Sky over Hawaii

, published by MIRA just this week, already has two books set on the islands in 1944 and November 1941. Now she tackles the invasion of Pearl Harbor from the perspective of civilians caught up in the conflict. In the midst of war and under threat of detention, her characters band together to protect one another, with a little help from Hawaii’s spiritual forces.

Seventy years after the end of World War II, it’s amazing how many new angles on the war writers are still discovering. Sara Ackerman, author of

Red Sky over Hawaii

, published by MIRA just this week, already has two books set on the islands in 1944 and November 1941. Now she tackles the invasion of Pearl Harbor from the perspective of civilians caught up in the conflict. In the midst of war and under threat of detention, her characters band together to protect one another, with a little help from Hawaii’s spiritual forces.I was delighted that Sara Ackerman agreed to answer my questions for this blog. Read on to find out more about what inspired her latest novel and where her literary journey will take her next.

This is your third novel set in Hawaii during World War II. What draws you to this time and place?

The place is easy. Hawaii is my home and I have a deep love for these islands. I was born and raised here and grew up on my grandparents’ stories of life during the war—from picking up hitchhiking marines with their lion, Roscoe, to nearly getting shot for being on the street at night, to housing homesick soldiers on weekends. Hawaii is the only state where war was literally on our doorstep. Many people view Hawaii purely as a sunny vacation spot, but we are so much more than beaches and coconut trees. As for the time period, it just happened that way. After Island of Sweet Pies and Soldiers , my publisher kept asking for more. Now I’m almost done writing Book 4, and there will be a fifth!

What gave you the idea for Red Sky over Hawaii, specifically?

I’ll start with saying that Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (the setting) is one of my favorite places. There is a vast and unearthly beauty there, and a very unique rainforest and ecosystem. I spend a lot of time exploring the backcountry and lava flows in the area. One day several years ago, I came upon a rustic old house tucked away in a remote part of the park. You would never even know it’s there. Needless to say, I was intrigued. When I dug deeper and found the house was originally built as a hideaway house in 1941 in case of a Japanese invasion, I knew I had to write a book about it someday. A year or so later, I met a woman who told me about her friend’s mother, who had been a little girl during the attack on Pearl Harbor and how her parents had been taken away and held for over a year by the FBI because they were German. I tracked down that story, which broke my heart, and decided I would merge the two and loosely base my story on them. Also, I’ve always been fascinated at how ordinary people band together during crises, and at the human capacity for resilience, so I wanted to explore this in my novel.

Tell us about Lana Hitchcock, your main character. How would you characterize her as a person?

To me, Lana embodies a young woman at a turning point in her life. She’s already faced some major struggles and now, with her father gone and the war underway, she suddenly feels like she has lost everything. I enjoyed seeing how she evolved through the story and began to slowly realize her inner strength. I love how her relationships with the kids evolves over time, and they become a sort of makeshift family. She’s courageous and smart and funny and imaginative, and I wish I could hang out with her!

And what brings her to Hilo at this moment in her life?

A phone call from her ailing father.

Within a day or so of Lana’s arrival on Hilo, the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor. Set the stage for us, please, as to what challenges she faces—and what she does about them.

Without giving much away, I’ll say that Lana arrives in Hilo and is quickly faced with her father’s German neighbors being hauled off by the FBI, leaving behind their two daughters and a Great Dane. She also knows that an old family friend, a Japanese fisherman, is in danger of being taken away—which would leave his teenage son alone. Armed with a cryptic map left by her late father, she has to decide how much she is willing to risk in order to help those in need.

The novel also contains elements of magic, which links Lana with Coco, the younger of the two German girls she is sheltering while their parents are in internment. What can you tell us about this plot thread?

A couple of years ago, I wrote a contemporary novel (not yet published) set at Volcano, which contains even more elements of magic. Red Sky over Hawaii is a sort of prequel, since it takes place in the same house and there is a familial connection. That is where the idea came from. I love magical realism, and if you’ve ever been to Volcano, you know it is quite an enchanting place. Stay tuned for more on that novel.

I can’t let you go without asking about Major Grant Bailey. Who is he, and what role does he play in your book?

All my books (so far) have love stories in them because I love a good love story. Who doesn’t? Grant is placed in a difficult situation because he gets to know Lana and the German girls, but he is also stationed at Kilauea Military Camp where detainees were held. I wanted to show the moral dilemmas that people faced at the time. For many folks, it wasn’t all black and white. Also, I live in the ranching town of Waimea, so I thought it would be fun to make him a cowboy. He’s my kind of guy! Manly and rugged but caring and sensitive, too.

Are you already working on something new?

I am! It’s currently called Radar Girls (titles have a tendency to change), and I’m very excited about it. The novel was inspired by true events of the Women’s Air Raid Defense (WARD), which was formed in the Hawaiian Islands by emergency Executive Order 9063 immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor. The brave women were sworn to secrecy and only told that they would be performing critical secret work for the army. More importantly, that they would be responsible for protecting their home and their country. Radar stations and command centers were formed on every island and staffed with local women, military wives, and recruits from the Mainland. Code name: Rascal.

I stumbled across their story while researching for The Lieutenant’s Nurse , and these women are my heroes! I was surprised I had never heard of them before. I should be finished with my first draft in a couple of weeks and it will release in late 2021. Publishing takes forever!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Sara Ackerman is the author of Island of Sweet Pies and Soldiers, The Lieutenant’s Nurse, and Red Sky over Hawaii. Born and raised in Hawaii, she studied journalism and later earned graduate degrees in psychology and Chinese medicine. Find out more about her at http://www.ackermanbooks.com.

Images: View of Halema’uma’u from Jaggar Museum by S. Geiger, public domain courtesy of the US National Parks Service; portrait of Sara Ackerman by Tracy Wright-Corvo (used with publisher's permission).

Published on June 12, 2020 06:00

June 5, 2020

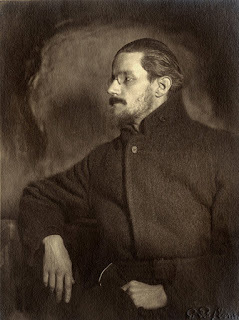

Tragic Muse

Being the child of a celebrity is seldom easy. Actor, writer, musician, business executive, lawyer, doctor—the profession hardly matters. If authors who achieve public acclaim with their first book struggle to match their own earlier success, how much more must the child of a famous father or mother fight the inner and outer voices of comparison, the hidden disappointment of never measuring up?

Being the child of a celebrity is seldom easy. Actor, writer, musician, business executive, lawyer, doctor—the profession hardly matters. If authors who achieve public acclaim with their first book struggle to match their own earlier success, how much more must the child of a famous father or mother fight the inner and outer voices of comparison, the hidden disappointment of never measuring up?Now imagine that your famous father is James Joyce, the author of Ulysses, a book widely banned in the English-speaking world at the time for its “filth” and “profanity”; that because of your parents’ desire to escape censure you have spent your childhood and youth in Italy and France; that you recognize you come a poor second to your older brother in your mother’s eyes; and that although you have managed to make a career and win praise for yourself as a modern dancer, when opportunity at last knocks on your door, you are horrified to learn that your parents have so little interest in your accomplishments that they expect you to drop everything to accompany them to Britain. When you resist, they guilt-trip you, pointing out that your father sees you as his Muse for the book described only as Work in Progress (known to us as Finnegan’s Wake), and his genius requires your sacrifice.

This is the situation Lucia Joyce faces in Annabel Abbs’s biographical novel

The Joyce Girl

, published in 2015 in the UK but reissued in the United States by William Morrow this past Tuesday. It is a tragic but riveting story of a young woman struggling to find her place in art and in love despite the demands of her family—a task complicated by her unerring ability to pick the wrong man. First Samuel Beckett (yes, the one who later wrote Waiting for Godot), then Alexander Calder (the painter), attract Lucia’s attention and desire, only to abandon her when she expresses her interest.

This is the situation Lucia Joyce faces in Annabel Abbs’s biographical novel

The Joyce Girl

, published in 2015 in the UK but reissued in the United States by William Morrow this past Tuesday. It is a tragic but riveting story of a young woman struggling to find her place in art and in love despite the demands of her family—a task complicated by her unerring ability to pick the wrong man. First Samuel Beckett (yes, the one who later wrote Waiting for Godot), then Alexander Calder (the painter), attract Lucia’s attention and desire, only to abandon her when she expresses her interest. Other affairs end no better. By 1930, Lucia—still no more than twenty-three—supposedly exhibits signs of psychiatric disturbance, starting a long progression that includes treatment by the analyst Carl Jung, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and decades in mental hospitals that last until her death in 1982. But is she really insane, or is this just another example of “inappropriate” behavior by women being punished in the same crusade that swept up Zelda Fitzgerald and many others in the 1920s and 1930s?

I know what I think. I recommend that you read this taut and enthralling book and make up your own mind. Lucia’s life is history, available for anyone to discover. But as so often happens in good fiction, The Joyce Girl takes her rather sordid and unhappy past and shines a light on the family and the society in which she lives. And that’s what makes the novel such a gripping literary journey.

Image: James Joyce in 1918, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on June 05, 2020 06:00

May 29, 2020

Interview with C.W. Gortner

I had heard C.W. Gortner’s name long before I read his previous novel, The Romanov Empress. And really, as a historian of Russia (albeit specializing in a much earlier period), how could I resist a topic like that one?

I had heard C.W. Gortner’s name long before I read his previous novel, The Romanov Empress. And really, as a historian of Russia (albeit specializing in a much earlier period), how could I resist a topic like that one?I really enjoyed the novel, which examined the life of Maria Feodorovna, the Danish princess who became the wife of Emperor Alexander III after his older brother died, leaving Sasha (his family nickname), as heir to the throne—not least because Alexander III has a rather poor reputation as a reactionary ruler in stark contrast to his supposedly enlightened father and inoffensive but ultimately indecisive son. So when Gortner’s publicist offered me a digital copy of The First Actress, his latest book on the life of Sarah Bernhardt, I leaped at the chance.

Indeed, I enjoyed the new book even more than The Romanov Empress. It’s fast-moving, well researched, and fascinating. I certainly knew of Sarah Bernhardt, that she was considered a great actress and lived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But I realized by the beginning of chapter 2 how much more I had to learn, and I have seldom had a more pleasurable time filling in the gaps. So read on as C.W. Gortner answers my questions about this novel and where he plans to take us next. I bet you too will find out a few things you didn’t know!

You have written a wide range of historical fiction—including, most recently, The Romanov Empress. What drew you to Sarah Bernhardt’s story?

I’ve known about Sarah since childhood. Both my maternal grandparents were actors, so I’m attracted to the profession, and her name was often cited at home, usually when I was being overdramatic. In addition, I write about controversial women and have portrayed an actor before: Marlene Dietrich in Marlene. As a novelist, I love exploring both the art and its personalities, and Sarah was a pioneer in acting. She changed the rules, setting a more realistic standard, and became the first internationally renowned celebrity for it. But, as for most famous actors, her journey was full of challenges and setbacks. She’d always been on my radar as a potential subject, as many people have heard of her but don’t know her personal story. She turned out to be an ideal subject for me, a courageous and eccentric woman who refused to conform to the norms of her time.

I’ve known about Sarah since childhood. Both my maternal grandparents were actors, so I’m attracted to the profession, and her name was often cited at home, usually when I was being overdramatic. In addition, I write about controversial women and have portrayed an actor before: Marlene Dietrich in Marlene. As a novelist, I love exploring both the art and its personalities, and Sarah was a pioneer in acting. She changed the rules, setting a more realistic standard, and became the first internationally renowned celebrity for it. But, as for most famous actors, her journey was full of challenges and setbacks. She’d always been on my radar as a potential subject, as many people have heard of her but don’t know her personal story. She turned out to be an ideal subject for me, a courageous and eccentric woman who refused to conform to the norms of her time. Her early life was difficult, especially her relationship with her mother. What can you tell us about that?

Well, it was a rough era for women. The majority didn’t have access to education, while employment options were very limited, unless you wanted to be a governess or seamstress. The mid-nineteenth century in Paris is often referred to as the era of the courtesan for a reason. Without means to make a living, some enterprising women resorted to the world’s oldest trade, except becoming a courtesan required more than beauty and the willingness to put a price on your body. Courtesans had to excel not only in carnal expertise but also in social charms; they established salons to entertain and attract a loyal clientele, which paid the bills. These women were, in essence, entrepreneurs.

Sarah’s mother, Julie, never achieved great wealth as a courtesan, so she expected her daughters to follow in her footsteps. Age put an expiration date on a courtesan’s livelihood and a successor was necessary to see her through her maturity. Sarah’s refusal to be Julie’s successor put a lifelong strain on their relationship. When Sarah did enter the courtesan trade, it was forced on her and she paid a steep price. Julie disapproved of Sarah’s impulsive decision to pursue acting instead, as actors were not well-regarded; indeed, in some circles, they were less socially accepted than courtesans. For Julie, her daughter’s work on the stage was reckless and doomed to failure, given that most actresses never found success.

An important part of her childhood was spent in a convent, in part because of that conflict with her mother. What did the convent mean for Sarah, and what did she take away from it?

Being dispatched to the convent was the result of Sarah’s early rebelliousness yet it turned out to be a refuge, where, ironically, she discovered women could be self-sufficient. Anti-conception was primitive, so courtesans often bore illegitimate children, but again, the era was no easier on children. For a courtesan to raise her child at home, where she maintained her salon, was impossible; her suitors were usually married, with families of their own. The last thing they wanted was her child underfoot, though it should be noted that if the child turned out to be theirs, some of the men made financial provision for it. Still, courtesans fulfilled an expensive male fantasy, so many either gave up their children to orphanages or had them reared far away. It was standard practice, though it caused havoc on the child, who often never knew who their father was and never saw their mother until they were old enough to be useful. Sarah’s childhood wasn’t exceptional for her circumstances, but her experience in the convent was. She received a decent education, was introduced to acting through the Nativity play, and the nuns encouraged her artistic inclinations, recognizing something extraordinary in her. The convent’s effect on her was profound; because of her time there, Sarah learned she could create a different existence than the one her mother demanded of her.