C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 24

October 25, 2019

Untold Stories

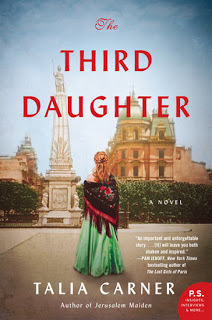

Literary inspiration comes from many places. As Talia Carner explains in my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, part of the inspiration for her most recent novel,

The Third Daughter

, came from a collection of short stories written by the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. These stories, collectively called Tevye and His Daughters or Tevye the Dairyman, were once the inspiration for the well-known Broadway musical and Hollywood film Fiddler on the Roof.

Literary inspiration comes from many places. As Talia Carner explains in my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, part of the inspiration for her most recent novel,

The Third Daughter

, came from a collection of short stories written by the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. These stories, collectively called Tevye and His Daughters or Tevye the Dairyman, were once the inspiration for the well-known Broadway musical and Hollywood film Fiddler on the Roof.In the musical, Tevye has five daughters, three of whom seem determined to defy his plans for them. One marries a poor man despite her father’s agreement to contract her to a well-off butcher. A second talks Tevye into accepting her marriage to a Jewish revolutionary, who then ends up in Siberia as a result of his political activities against the tsarist system. A third runs off with a Russian who has won her heart after Tevye refuses to accept her wedding to a gentile.

But what happened to the other two girls? That was the question that started Talia Carner on her journey toward the novel that became The Third Daughter. As tends to happen in fiction, the story changed along the way. The second and third daughters fused into one, and the fifth daughter disappeared altogether, leaving three girls. The Ukrainian pogrom that ends Fiddler on the Roof opens The Third Daughter, as the dairyman and his wife and their one remaining daughter struggle to find a safe place despite having lost most of their household goods. Names are changed, as are details, but the essence of the original story remains—at least in the first chapter or two.

The most striking innovation is Carner’s incorporation of another of Sholem Aleichem’s stories, “The Man from Buenos Aires,” a trader of unspecified goods whose business she matches to the history of Zwi Migdal, a little-known trafficking organization that operated entirely within the law in Argentina from 1870 to 1939. In doing so, she takes a beloved production and turns it into a searing indictment of the brutality inflicted on Jews within the Russian Empire and its consequences, including for women victimized by those willing to profit from their misfortune.

So listen to the interview. Read the Q&A Talia produced for my blog last month. But most of all, read the book. I guarantee you won’t be able to put it down.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. As revealed by the title of Talia Carner’s latest novel, The Third Daughter (William Morrow, 2019), her heroine, Batya, has two older sisters. Both ran off with men their parents could not tolerate, placing a heavy burden on Batya to compensate for her sisters’ failings by making her parents happy.

When her family is forced to flee its home in a Ukrainian village to escape a pogrom, losing most of its goods, Batya helps out by taking a job at a local tavern.

There she meets Yitzik Moskowitz, a smooth-talking, well-respected, and obviously well-off visitor who soon convinces Batya’s father to give his third daughter’s hand in marriage. Moskowitz promises to wait two years before making Batya his wife, but he insists she travel with him now, because who knows when he will return to Ukraine?

Although only fourteen, Batya agrees to accompany her future husband on his journey. But after one night on the road, she discovers that what the “Man from Buenos Aires” wants from her has nothing to do with marriage. After a hideous journey across the Atlantic, Batya ends up in an Argentinean brothel, enslaved to the legal trafficking organization Zwi Migdal. For a while, she longs for death. But strong and resilient, she learns to adapt and even finds solace in unexpected places.

Drawing on a series of stories by Sholem Aleichem, some of which became the basis for the popular musical Fiddler on the Roof, this fifth novel by a committed social activist is not always an easy read. But it is an essential and compelling read, not least because despite being set in the late nineteenth century its story is as contemporary as yesterday’s headlines.

Image: Marc Chagall, The Fiddler (1912–13), public domain via Wikimedia Commons. This series of paintings by Chagall inspired the sets of the original Fiddler on the Roof.

Published on October 25, 2019 06:00

October 18, 2019

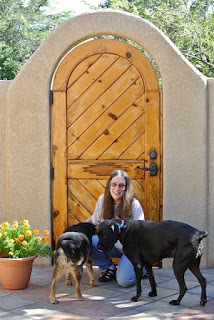

Interview with Joan Schweighardt

I love talking with other authors—both for my New Books in Historical Fiction podcasts and here on the blog via the written word. But it’s a special pleasure to host a fellow Five Directions Press author.

I love talking with other authors—both for my New Books in Historical Fiction podcasts and here on the blog via the written word. But it’s a special pleasure to host a fellow Five Directions Press author.I met Joan back in 2016, when I interviewed her about her reissued novel The Last Wife of Attila the Hun . Time went by, she needed a new publisher, and in due course she joined our writers’ coop. As an editor and former publisher, as well as a talented writer, she’s a natural fit for us. And although we didn’t know it at the time, she also has a particular gift for social media. All those lovely articles about books and readers and related matters that show up on our Facebook page come from her.

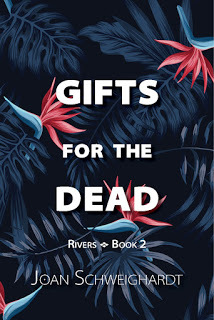

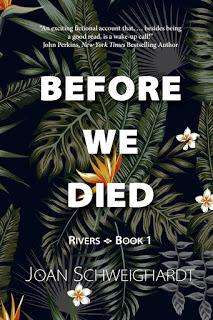

Best of all, we just published Gifts for the Dead , the second novel in her Rivers trilogy ( Before We Died is the first). So read on to find out more about both books.

Gifts for the Dead is a follow-up to your previous novel, Before We Died. Without giving away spoilers, what do we need to know about that first book to understand this new one?

Gifts comes furnished with enough of the relevant info from Before We Died to make it make sense as a standalone novel. Basically readers learn that in the first book, Jack and Baxter Hopper, two young Irish American brothers, leave their jobs as longshoremen on the docks of Hoboken, NJ and travel to the rain forests of South America to become rubber tappers, in the year 1908. They embark on this trip because they are young and adventurous, but also because they are looking for a way to distract themselves from the grief they have suffered since their father’s sudden death in an apartment building fire. And since the rubber boom is in full swing at that time, they believe they can make some quick money too. They are absolutely unprepared for the realities of the rubber tapping industry, which include not only the dangers inherent in working in the deep jungle but also the greed of the barons at the top of the industry hierarchy. As a result of these dangers, Jack Hopper eventually returns to Hoboken—without his brother.

Gifts comes furnished with enough of the relevant info from Before We Died to make it make sense as a standalone novel. Basically readers learn that in the first book, Jack and Baxter Hopper, two young Irish American brothers, leave their jobs as longshoremen on the docks of Hoboken, NJ and travel to the rain forests of South America to become rubber tappers, in the year 1908. They embark on this trip because they are young and adventurous, but also because they are looking for a way to distract themselves from the grief they have suffered since their father’s sudden death in an apartment building fire. And since the rubber boom is in full swing at that time, they believe they can make some quick money too. They are absolutely unprepared for the realities of the rubber tapping industry, which include not only the dangers inherent in working in the deep jungle but also the greed of the barons at the top of the industry hierarchy. As a result of these dangers, Jack Hopper eventually returns to Hoboken—without his brother.Where are Nora Sweeney and Jack Hopper at the beginning of this novel? What do each of them want, and what keeps them from getting it?

Jack returns from South America so very ill with a combination of jungle diseases and infections that all he really wants in the first pages of Gifts for the Dead is to continue along on his path into oblivion. Nora, who was to have married Baxter, wants Jack to live. Nora has known the Hopper family since childhood, and she is uncommonly close to Maggie, Baxter and Jack’s mother. Maggie has already lost her husband, and now, with Jack’s solo return, it seems she’s lost one son as well. Nora feels that losing Jack would be more than Maggie could bear.

And what about them as individuals? Let’s start with Nora, whose story is told in first person. How would you encapsulate her personality and her background?

Nora’s parents died of consumption when she was four, and she was raised by her Aunt Becky, an advocate for various political issues, particularly workers’ rights. Aunt Becky knows just enough about child rearing to glean that it’s not a good idea to leave a four-year-old alone for hours at a time. As she doesn’t have the money for a sitter, she drags Nora along with her to her various political events from the get-go. Not surprisingly, Nora grows up to be politically oriented herself. When we first meet her, she is a proud suffragette. She is also alone, because as soon as Nora is old enough to manage without a guardian, Aunt Becky flees to Boston to get on with her own life. Nora sees herself as flawed, but also fearless and somewhat invincible. The reader will see her other side as well.

And Jack? What drives him in this book—and in general? What made him the man he is today?

Even as Jack recovers from his illness, he cannot get over the loss of his brother. And he can’t talk about it either. For one, he is harboring a secret about what actually happened to Baxter in the deep jungle, and he is not ready to share it. For their part, Nora and Maggie have come to respect—or at least tolerate—his reticence, and to imagine that if forced to open up, Jack might fall back into the same mental stupor he was in when he first came home. Jack’s guilt and regret drive the decisions he makes throughout the book. And for all of them, but for Jack in particular, Baxter is always the elephant in the room.

And what drew you to write about the Amazon (that’s the river, not the mega-store) in the early twentieth century?

Two things occurred at about the same time: One, a freelance job I had with a local publisher required me to read a slim diary written by an early twentieth-century rubber tapper, probably the only one in existence. I knew nothing about the rubber boom in South America before then, and I found the information fascinating. And two, around the same time I decided to put aside my fear of snakes and bugs and travel to the rain forests of Ecuador with a group of environmentalists and sustainability advocates. This “perfect storm” was life-changing for me. As soon as I returned from the rain forest I began reading everything I could find about the flora and fauna of Amazonas, the history of rubber in South America, the city of Manaus, Brazil, which was the hub of the rubber boom back then, and on and on. And all the while I was reading, I was imagining the characters I would need for my own retelling of the rubber boom story. When I had a first draft of book 1, I returned to South America to spend time in Manaus and to travel the rivers with a private guide to see, among other things, rubber trees.

Most of the story in Gifts for the Dead, however, takes place in Hoboken, NJ. Why there, and what kinds of research did you need to do?

While the rain forest informs all three books, I still needed a location for my main characters to hail from. I grew up in New Jersey, so I was familiar with Hoboken, and I knew it had an active shipyard and train station and ferries running into Manhattan back in the early twentieth century. It was the perfect location for characters who would do a lot of traveling. But the more I learned about Hoboken, the more I realized I had to learn. Since Gifts for the Dead unfolds between the years 1911 and 1928, it necessarily covers the First World War—among other events. Hoboken played a huge part in the war, for a variety of reasons, not least of which is that doughboys from all over the country departed for Europe from Hoboken once Woodrow Wilson declared war. Hoboken at that time was home to three immigrant communities: Irish, German, and Italian. As you can imagine, German Americans took some abuse during the war for having connections to Germany. This was true in the whole country, of course, but particularly in Hoboken.

What can we expect in Rivers 3?

The third Rivers book will be called River Aria, and yes, it does concern itself with opera. How do I go from the rubber boom to WWI and its aftermath to opera? I can’t say without giving away some of the stuff that happens in Gifts for the Dead. I can say the last book follows the lives of the same characters—plus or minus one or two—and it takes place in the same two locations, with the addition of a third location, Manhattan, right across the river from Hoboken. I’m about three drafts in, with at least two more to go.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Thank you very much.

Joan Schweighardt is the author of five stand-alone novels and the Rivers Trilogy. In addition to her own writing projects, she writes, ghostwrites, and edits for individuals and corporations. Find out more about her at http://www.joanschweighardt.com.

Like her on Facebook

Follow her on Twitter

Find her on Instagram

Published on October 18, 2019 06:00

October 11, 2019

Writing Wayland

About a year ago, I interviewed Lee Zacharias for New Books in Historical Fiction about her novel

Across the Great Lake

, then recently published by the University of Wisconsin Press.

About a year ago, I interviewed Lee Zacharias for New Books in Historical Fiction about her novel

Across the Great Lake

, then recently published by the University of Wisconsin Press.This week I received a message from a friend of Lee’s, also with a new novel. I couldn’t offer her an interview, because my schedule for the network is already overbooked, but I did invite her to submit a guest post for my blog—and here it is. You can find out more about her work and how to contact her by paging down to the end. Thank you, Rita, and I wish you all success with your books!

From Rita Sims Quillen:

First and foremost, I am a poet, having published five books of poetry, but I had always dreamed of moving to fiction. When my husband first told me the tale of his grandfather’s incredible adventures during WWI, I thought, I don’t even know what that war was about. In school, we study the Civil War—crazy but clear—and World War II with its two fronts—crazy but clear—but WWI? It seemed a very complex war, more irrational than the other two, if that makes any sense. And I couldn’t recall anything really about the time period except the big flu epidemic. I did remember that from history class.

When I decided I was going to try to write my first novel, Hiding Ezra (Little Creek Books, 2014), it would be built around the basic true story of my husband’s grandfather deciding that his family needed him a lot worse than the Army did, but I could find nothing in the library to help me understand his predicament or the times he lived in. I did read some books and articles about the war, and also specifically about the flu epidemic, but I found nothing about deserters, nothing about the reaction of real people here at home in southwestern Virginia, nothing about what challenges the first modern draft presented. So I knew I was going to have to find out what I needed to know some other way.

So I began to look for newspaper accounts of the day. I ended up spending 4 summers—when I was out of school—squirreled away in local libraries readings newspaper accounts of that time. I read the Kingsport Times News, the Bristol Herald-Courier—the Scott County, VA, paper of the day—and several other coalfield papers, starting from the summer of 1918 and going all the way through to the fall of 1922. Every day’s paper, cover to cover. On microfilm. Now you see why it took four years.

But then I was ready to write Hiding Ezra, having come to understand that my husband’s grandfather was part of a huge sociological phenomenon—175,000 men that went AWOL for similar reasons—and that incredible events besides the flu epidemic were occurring: a coal strike, a wheat shortage, the coldest winter in decades.... History came alive, as sharp and clear and real as my own life, and I had to make others see it, too, with new eyes, to understand what incredible hardship had occurred in this forgotten and often overlooked war. It is the story of thousands of families—a story that had to be told

Now, fast forward a few years, and the long-awaited sequel, Wayland (Iris Press, 2019), is out. With this novel, I returned to the story of many of the characters I loved from the first novel, but without the restrictions of a true story to impose its own requirements and confinements! People say, what’s your new novel about? My mind whirls. The answer would be too long if I told it all. It’s about characters from my first novel, Hiding Ezra, that I love dearly and wanted to give some joy, peace, hope that they didn’t have in that novel. It’s a love story wrapped inside a marriage in trouble. Wayland is a study of sociopaths and mental illness, in general, versus eccentricity. It’s about the world of the hobos and their culture during the Great Depression in a tranquil and quaint little community in the Appalachian Mountains. It’s about the beautiful, unique, and good-hearted country people of my community, people of deep faith and deep thoughts about life’s most important questions. The book is an illustration of the way that the Bible and its language are so integral to the daily lives and daily thoughts of Appalachian people in the world I grew up in.

The subject receiving the most attention, however, and the one that took tons of research and thought was pedophiles and how they choose, then manipulate, their victims and their families in order to gain the trust necessary for the kind of access they need to fulfill their twisted fantasies. In hobo Buddy Newman, I wanted to create an unforgettable and engrossing evil character. I used Shakespeare’s conniving, diabolical Iago as inspiration for the way he pitted people against one another, whispering in vulnerable ears whatever lies that would take him closer to his target. I thought about Hannibal Lector and his cruel games, about Faulkner’s Abner Snopes and his furious resentment of those who were more successful, his psychotic violence and sense of entitlement.

The subject receiving the most attention, however, and the one that took tons of research and thought was pedophiles and how they choose, then manipulate, their victims and their families in order to gain the trust necessary for the kind of access they need to fulfill their twisted fantasies. In hobo Buddy Newman, I wanted to create an unforgettable and engrossing evil character. I used Shakespeare’s conniving, diabolical Iago as inspiration for the way he pitted people against one another, whispering in vulnerable ears whatever lies that would take him closer to his target. I thought about Hannibal Lector and his cruel games, about Faulkner’s Abner Snopes and his furious resentment of those who were more successful, his psychotic violence and sense of entitlement.

But the bottom line is, I wrote a book to entertain and keep you on the edge of your seat as you watch the tale unfold— suspense! If I can do that while also giving you the ability to recognize a pedophile’s efforts at grooming your child or grandchild, well, that’s a good year’s work. If you’d like to read sample chapters and much more info about all my work, I hope you’ll stop by my website.

Rita Sims Quillen—poet, musician, songwriter, and novelist—is the author of Hiding Ezra and Wayland, as well as several poetry collections. She lives and farms in Scott County, Virginia. Find out more about her, including her social media links, at http://www.ritasimsquillen.com.

Published on October 11, 2019 07:45

October 4, 2019

Unwedded Bliss?

I tend not to think of the 1950s as history. After all, I regularly spend many mental hours in the 1550s—or earlier—and I remember the second half of the 1950s, so how can it be the past, in the same way that Muscovite Russia is a time long gone? But as I read Sofia Grant’s new historical novel, Lies in White Dresses, I realized that indeed the world she portrays has ceased to exist, in the same way (if not perhaps to the same degree) as the court of Ivan the Terrible has ceased to be.

I tend not to think of the 1950s as history. After all, I regularly spend many mental hours in the 1550s—or earlier—and I remember the second half of the 1950s, so how can it be the past, in the same way that Muscovite Russia is a time long gone? But as I read Sofia Grant’s new historical novel, Lies in White Dresses, I realized that indeed the world she portrays has ceased to exist, in the same way (if not perhaps to the same degree) as the court of Ivan the Terrible has ceased to be.Most notable is the vast difference in our ideas of what must remain private, the shame associated with marriages that don’t work (and some of the reasons why at least one of those marriages doesn’t work) or with even such simple things as physical defects or mental imbalances. In a life before the Internet, never mind social media, views about sharing the details of one’s life were much stricter.

In some ways, that was a good thing. The endless scandals that bring down otherwise competent politicians and threaten the lives of princesses were less frequent then. But so were exposures of deeds that claimed real victims: spousal abuse, harassment at work. And women of talent and ability often felt compelled to follow the path of marriage and child-rearing, lest they face blame for their failure to get (or keep) a man. Even divorce carried a stigma, although by 1952 that had started to fade.

Sofia Grant and I explore these themes and more in our New Books Network interview. And don’t miss the Q&A I ran here on this blog when she published her first historical novel, The Dress in the Window.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Francie Meeker and her best friend, Vi Carothers, bought into the promise offered to middle-class, especially white, women in the mid-twentieth-century United States: find a man with a good career, marry young, stay at home, raise the children, keep house, and all will be well.

By 1952, despite some successes, reality has killed this dream. So at the beginning of Lies in White Dresses (William Morrow, 2019)—the sparkling new novel by Sofia Grant, who is also the author of The Dress in the Window and The Daisy Children—Francie and Vi are boarding a train to Reno, Nevada. There, after six weeks residency, they can file for divorce.

On the train they meet a young woman, June Samples, traveling with a small child. Unlike Francie and Vi, June has almost no means of support. Vi takes a liking to the younger woman and, when they reach Reno, she invites June to share her hotel suite.

The first night, a babysitting job brings the threesome to the attention of Virgie, the hotel keeper’s daughter and a self-styled detective. Then, not long after their arrival, the local police report that Vi has drowned. Virgie is convinced she knows what happened. But who will believe a twelve-year-old girl?

Compared to medieval Europe or Han Dynasty China, the 1940s and 1950s do not seem so long ago. But as Sofia Grant makes clear in this page-turning novel, in many respects the previous century was indeed a different world.

And on another note, if you missed my previous interview with Linnea Hartsuyker about her Viking saga, you can find more information about that and a link to the interview on the Literary Hub.

Published on October 04, 2019 09:41

September 27, 2019

Bookshelf, Fall 2019

Yes, indeed, fall is here, and a new crop of books has arrived to keep my shelves nice and full. In addition to Sofia Grant’s Lies in White Dresses (on which more next week, when that interview posts), Talia Carner’s The Third Daughter (interview completed this week, not sure yet when it will go live on the New Books Network), and Georgie Blalock’s The Other Windsor Girl, scheduled for a written Q&A here in early November, I have the following titles lined up—all eventually destined for interviews, or so I hope.

Yes, indeed, fall is here, and a new crop of books has arrived to keep my shelves nice and full. In addition to Sofia Grant’s Lies in White Dresses (on which more next week, when that interview posts), Talia Carner’s The Third Daughter (interview completed this week, not sure yet when it will go live on the New Books Network), and Georgie Blalock’s The Other Windsor Girl, scheduled for a written Q&A here in early November, I have the following titles lined up—all eventually destined for interviews, or so I hope. Order is alphabetical, as we’re still working out details of the schedule. So far, I’ve had time to read only one. To find out which one, read on.

Like half the rest of the world, I discovered Tracy Chevalier through The Girl with the Pearl Earring. Loved the book, even more than the movie, and squealed with glee when her publicist wrote to me about her latest novel, A Single Thread, set in Britain in 1932. Here Violet Speedwell, one of the many women left alone by the Great War, chooses to move to Winchester rather than spend any more of her life caring for her embittered mother. There Violet becomes involved with a society of embroiderers associated with the cathedral. But as she settles in, the specter of a new war threatens, placing everything she has worked for at risk.

Like half the rest of the world, I discovered Tracy Chevalier through The Girl with the Pearl Earring. Loved the book, even more than the movie, and squealed with glee when her publicist wrote to me about her latest novel, A Single Thread, set in Britain in 1932. Here Violet Speedwell, one of the many women left alone by the Great War, chooses to move to Winchester rather than spend any more of her life caring for her embittered mother. There Violet becomes involved with a society of embroiderers associated with the cathedral. But as she settles in, the specter of a new war threatens, placing everything she has worked for at risk.

Yes, another Uhtred novel—no. 12, I believe. But really, can one ever have too much Uhtred? In Sword of Kings, King Edward (successor to Alfred the Great) is dying. Uhtred wants nothing more than to stay and guard Northumbria, his home and now the last outpost standing against the Saxon kings’ complete control of England. Apart from anything else, he’s getting on in years, and war doesn’t have the appeal to him that it did in his teens and twenties.

But once again, the oath he has sworn to Aethelstan calls Uhtred south and into the battle among the rival candidates for Edward’s throne.

Although its title, Bound in Flame, sounds like a bodice ripper, the cover images of Kathryne Kayne’s new novel redirect us to Hawai’i in 1906-9. There a young woman, Letty Lang, struggles to reconcile her love of animals, her campaign for female suffrage, a romantic relationship that she may have to protect from her own otherworldly powers, and a special tie to her native land, recently and forcibly annexed by the United States. The flames represent, more than anything else, the island’s many volcanoes—but perhaps also the fire of Lily’s own nature. This first volume in a new series about the ranching women of early twentieth-century Hawai’i, stands out for me because so few writers have chosen to tackle this subject in fiction.

Although its title, Bound in Flame, sounds like a bodice ripper, the cover images of Kathryne Kayne’s new novel redirect us to Hawai’i in 1906-9. There a young woman, Letty Lang, struggles to reconcile her love of animals, her campaign for female suffrage, a romantic relationship that she may have to protect from her own otherworldly powers, and a special tie to her native land, recently and forcibly annexed by the United States. The flames represent, more than anything else, the island’s many volcanoes—but perhaps also the fire of Lily’s own nature. This first volume in a new series about the ranching women of early twentieth-century Hawai’i, stands out for me because so few writers have chosen to tackle this subject in fiction.

I heard about Lara Prescott’s debut novel, The Secrets We Kept, on NPR Weekend Edition, during the author’s interview with Scott Simon, one of my heroes. When I saw it listed again on a list of most awaited fiction for the fall of 2019, I knew I had to follow up. Doctor Zhivago, the CIA in the United States and Russia, female typists working for the CIA? How could a historian of Russia resist? I’ll be talking to the author, I hope, sometime in December and January, after her hectic book tour calms down.

In January of this year, I featured

The Black Ascot

, by the ultra-productive mother-son team that publishes as Charles Todd, on this blog. I loved that book and was amazed to realize that it was no. 21 in a series I’d never heard of, never mind that the author(s) also had a second series centered on a World War I nurse named Bess Crawford, with ten books, and a couple of stand-alone novels as well. So when their publicist pitched me on Bess no. 11, A Cruel Deception, I knew I had to follow up. This is the one book I just finished, in advance of an interview in mid-October, and I really enjoyed it.

In January of this year, I featured

The Black Ascot

, by the ultra-productive mother-son team that publishes as Charles Todd, on this blog. I loved that book and was amazed to realize that it was no. 21 in a series I’d never heard of, never mind that the author(s) also had a second series centered on a World War I nurse named Bess Crawford, with ten books, and a couple of stand-alone novels as well. So when their publicist pitched me on Bess no. 11, A Cruel Deception, I knew I had to follow up. This is the one book I just finished, in advance of an interview in mid-October, and I really enjoyed it. Here the war has ended, and Bess’s matron sends her to France to find out what has happened to the matron’s son. Bess assumes the worst, and she’s not far off track there, but the solution to the puzzle takes her in directions that are at once not anticipated at the beginning and completely in line with what we now know about the experience of soldiers stuck in the trenches for far too long.

Bess is smart and independent, empathic and caring, blunt when it counts and tactful when she needs to be—a heroine I want to learn more about, as soon as I shrink those book piles down to a reasonable size....

Image: Cat watching sunset from Pixabay (no attribution required).

Published on September 27, 2019 06:00

September 20, 2019

Body Language

This week I had the pleasure of meeting in person, for the first time, a writer with whom I’ve been corresponding by e-mail for the last three and a half years. She’s a member of Five Directions Press, so the other two founders—that is, the rest of my writers’ group—have also been in e-mail contact with her since 2016, but only I have had the chance to talk with her via Skype in connection with the New Books Network.

The meetings went very well, but that’s not the point of my post. What I realized once again based on these relatively brief encounters, which lasted altogether no more than six or seven hours spread across a weekend, is how much body language and expression affect understanding and, in a sense, what a difficult task we novelists assign ourselves. Even scriptwriters have the advantage of knowing that their words will be given life by actors who may not look exactly like the characters in the writers’ heads but who, if talented, can convey all the nuances of emotion that stance and expression and voice communicate so much more effectively than words on a page.

I know: this isn’t exactly earth-shattering news. Most of us know, if we stop to think, how readily text messages and e-mail lead to misunderstandings. Why else do we constantly expand the range of emojis in the vain hope of underlining that, yes, that snarky comment was intended as a joke—something we would never need to do in real life because tone and laughing face make the point for us.

Nevertheless, when we sit down to write—and even to read—it’s worth thinking about how much work goes into revealing not just what characters say but what they mean. On a movie screen, we can guess: an actor smiles, and we know right away whether that smile conveys joy, naiveté, surprise, sarcasm, or any one of a dozen other reactions or combinations of reaction. We know even when the character says something quite different.

But a writer can’t keep saying “he smiled” or “she frowned.” It gets boring. “She smiled sarcastically” or “he frowned in contemplation” is permissible once in a while, but used too often it draws attention to itself in the wrong ways. Shouldn’t the reader be able to tell from the dialogue if a character is angry or thoughtful, sarcastic or sincere?

But a writer can’t keep saying “he smiled” or “she frowned.” It gets boring. “She smiled sarcastically” or “he frowned in contemplation” is permissible once in a while, but used too often it draws attention to itself in the wrong ways. Shouldn’t the reader be able to tell from the dialogue if a character is angry or thoughtful, sarcastic or sincere?Novelists and short story writers do have one asset unavailable to script- and screenwriters and even ordinary listeners: the internal monologue. When a character means one thing and says another, we can show what goes through that person’s head. We can also illustrate different interpretations through dialogue: Character A says this, and Character B reacts with that. And we have action verbs, which get to body language: a person who struts leaves a different impression from one who strolls, strides, or minces.

That’s part of the fun of writing fiction, at least for me. How do I differentiate my characters through language, gesture, mode of thought, appearance? How do I fill them out and bring them to life so that readers can relate to these imaginary people as friends, family, or no one they’d ever want to associate with in real life?

Yet sometimes, I’d just like to sit them down for a cup of coffee. Or turn them over to a crackerjack film director and her handpicked cast to see what the professionals could do with them. Because what counts is the body language, when all’s said and done.

Images purchased from iClipart.com.

Published on September 20, 2019 06:00

September 12, 2019

Fictional Furry Friends

This week I’d intended to write a post about Gill Paul’s new novel, The Lost Daughter —which, although not exactly a sequel to the same author’s The Secret Wife , addresses a similar theme. But the plan is to coordinate my post with Jennifer Eremeeva’s interview with the author, and that’s not yet live on the New Books Network. So check back next week for a look at Romanov grand duchesses and their (maybe) fates.

As I was racking my brains for an alternative topic, serendipity intervened in the form of an unexpected but highly entertaining conversation about dogs and their potential place in my current work in progress, Song of the Sisters (Songs of Steppe & Forest 3). I didn’t initially plan for the inclusion of a dog, but the more I think of it, the more I love the idea. Here’s a brief background as to why.

After months of holding off on sharing my opening of Sisters with my writers’ group, I decided this month that I’d done as much as I could without input. The value of giving half-baked chapters to trusted writer friends is that they hold up a mirror, revealing where I’ve supplied too much information and where not enough, the places where the energy flows and where it stalls. Especially because I have spent so long roaming the wild forest that is Muscovite history, I have a tendency to demand too much background knowledge from my readers. I need people who can say “huh?” without worrying that by doing so they will hurt my feelings.

After months of holding off on sharing my opening of Sisters with my writers’ group, I decided this month that I’d done as much as I could without input. The value of giving half-baked chapters to trusted writer friends is that they hold up a mirror, revealing where I’ve supplied too much information and where not enough, the places where the energy flows and where it stalls. Especially because I have spent so long roaming the wild forest that is Muscovite history, I have a tendency to demand too much background knowledge from my readers. I need people who can say “huh?” without worrying that by doing so they will hurt my feelings.I haven’t received specific responses yet, but I did get enough feedback that I can see (or imagine, since this particular comment has not been made) a story problem that I have yet to solve. Songs 3, unlike its predecessors, is intended as a kind of Muscovite comedy of manners à la Georgette Heyer. There are a few political hijinks—I’d bore myself to tears otherwise—but mostly it’s a contest among cousins for control of a household and their own futures. I’ve worked on the female leads, and at least one important character received a thorough treatment (and makeover, in response to criticism from that same writers’ group) in Song of the Shaman. But Igor, the antagonist, is new—and, as I’m coming to realize, undeveloped. Cue the dog.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m well aware that Igor’s going to need more than a dog to make him a believable human being, even as an antagonist. But a writer can do so much with a dog. It expresses the hidden feelings of everyone present, reveals likes and dislikes, separates the sensitive souls from the distinctly insensitive ones. And unlike cats, which lived on the sidelines of medieval life thanks to the bizarre association that the Christian Church made between them and the Devil, dogs played an important role in Muscovite Russia just as they did throughout Europe and many other places in the world.

Most of them were working dogs, of course: scent hounds and sight hounds, guard dogs and coursers. The fancy breeds we think of today didn’t exist then, but dogs are dogs and people are people, and there’s nothing like a dog to open up a character who, for one reason or another, hides any hint of uncertainty behind an over-confident mask.

So meet Laika, a Polish hunting dog of a type attested from the thirteenth century. She looks like what would happen if you crossed a Doberman with a Labrador retriever, and if anyone can reach Igor’s stubborn heart, she can.

So meet Laika, a Polish hunting dog of a type attested from the thirteenth century. She looks like what would happen if you crossed a Doberman with a Labrador retriever, and if anyone can reach Igor’s stubborn heart, she can. Although you never know, she just might take a shine to my heroine Darya instead. After all, who has the good treats?

Images: Polish Hunting Dog CC BY 2.5, A. Balcerzak and Lukas3, via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on September 12, 2019 13:24

September 6, 2019

Interview with Talia Carner

One of the delights of hosting New Books in Historical Fiction is learning about places, times, and events that I know nothing about. That was true for the story behind

The Third Daughter

, Talia Carner’s wonderful new novel—released just this past Tuesday. And tragic as that story is for her heroine, the novel is absolutely compelling. So when you finish reading her answers, rush—don’t dawdle—to secure your copy. (Just to clarify, I could not interview Talia for the podcast because of too many other commitments, so we agreed to this Q&A instead.)

One of the delights of hosting New Books in Historical Fiction is learning about places, times, and events that I know nothing about. That was true for the story behind

The Third Daughter

, Talia Carner’s wonderful new novel—released just this past Tuesday. And tragic as that story is for her heroine, the novel is absolutely compelling. So when you finish reading her answers, rush—don’t dawdle—to secure your copy. (Just to clarify, I could not interview Talia for the podcast because of too many other commitments, so we agreed to this Q&A instead.)The Third Daughter is your fifth novel, and it’s quite distinct from the four that came before, which themselves cover a wide range of time periods, places, and subjects. How do you select topics for your novels?

Stories find me. I don’t seek them out. Each time I am far along through a novel and think that maybe it’s my last one, the next one presents itself. Each takes hold of my head and heart and compels me to sit down to what turns out to be three to six years’ work. I’ve long realized that the seeds of every story had sprouted in my psyche years earlier, where they fermented…. All it takes is a passing comment, a line in a newspaper, or a visual cue, and the idea blooms, takes hold on me and doesn’t let go until I crawl under the skin of a new protagonist and tell her story.

And while indeed my novels seem to be painted on large canvases that cover a wide range of time periods and countries, the common denominator is that each deals with a universal social issue, mostly unique to women. In each of my novels I rise and fall with the protagonist’s spirit as she struggles—and prevails against—the forces that shape her life, be they psychological, political, social, geographical, legal, economic, or religious.

What has fascinated others—and I hadn’t noticed until it was pointed out to me—is that each subject has been one rarely, if ever, explored before in fiction. It was an interesting revelation to me, and I learned something about myself: While I strictly avoid personal disagreements on any topic, I have more courage than I had thought I possessed when it comes to writing. I’ve taken on the US legal system, the Chinese government, God, the Russian mafia—and now, the huge scourge of our society in the form of sex trafficking.

You’ve written that a short story by Sholem Aleichem first made you aware of Zwi Migdal, the legal trafficking organization that forms the center of The Third Daughter. What caught your attention when you read his tale, and how did you go about turning the idea into a book?

I’ve mentioned above that the seeds of a novel begin to bloom years or even decades before I write it. Since childhood I had a strong sense of right and wrong, and when I encountered social injustice it evoked strong emotions in me.… I first became aware of the magnitude of global and historical sexual exploitation at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing. A tiny, aging Filipina with an operatic voice cried to the heavens about her enslavement by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII, as one of thousands of girls and women captured in the Pacific Rim. Then a teenager, she had been imprisoned in a “comfort station” to serve the soldiers’ sexual needs.

The plight of kidnapped women forced into sexual slavery touched me deeply, and in my head it was narrated by the Filipina’s haunting voice. In subsequent years I read about sex trafficking and attended presentations by UN-affiliated NGOs in New York City, where I live.

A snippet of the history of girl victims lured from beleaguered Eastern European Jewish communities to South America had come to my attention through Hebrew literature, and I even tried to inquire about it on a visit to Buenos Aires in 2007. I got no traction, and let it go. However, my interest was reawakened in 2015 when I stumbled upon the short story by Sholem Aleichem, “The Man from Buenos Aires” (now in my own translation on my website). In the story, the author reports about his encounter on the train with a shady, sleek character who brags about his entrepreneurial success but never reveals the nature of his business. I suspected what the venture that brought this fellow his riches might be: sex trafficking. I Googled the subject, and that is when I first encountered the name Zwi Migdal. I was appalled to find out that it had been a legal trafficking union and that it had operated with impunity for seventy years. It was shocking to realize how much information about it was hiding in plain sight. Most appalling to me was that the estimated 150,000 to 220,000 Jewish women who had been exploited by members of this organization had been forgotten, lost in the goo of history.

Tell us about Batya, your heroine. What kind of person is she when the book opens, and how do things go so terribly wrong for her?

Since Sholem Aleichem’s short story about the man from Buenos Aires appeared in the same “Railroad Stories” collection as those of Tevye the Dairyman, it was a natural creative process to continue the stories Tevye didn’t tell. In the collection, he first said to the author that he had seven daughters, then six, and ended up telling the stories of five. I pictured a daughter whose story wasn’t told. Batya has an inner strength that, at fourteen, she’s yet unaware of. She’s sensitive and has a clear sense of what’s expected of her, yet has no vision of a future different from her mother’s life. Growing up in a warm home where her parents, in spite of the hardships and strife they suffered, showed caring and were protective, she had liked to play and laugh. What shapes Batya, though, when we meet her, is the disappointment that her two older sisters caused their parents, when each rejected the tradition of letting her father select her match, and instead fell in love with a man of her own choosing. The two sisters’ actions threw the devoted Batya into a specific orbit: she must make up for their betrayals by being even more obedient to her parents.

Their emotional well-being is severely challenged when the family is exiled during a pogrom, losing their footing along with their meager belongings. Batya finds herself in a position to be the one who helps them secure food and shelter by working in a tavern. And then a greater chance to bring them happiness presents itself, if Batya accepts the marriage proposal of a wealthy stranger.

Things go terribly wrong because the millions of Jews living and persecuted in the Pale of Settlement within the Russian Empire found mates for their children through word-of-mouth, loose connections, and distant introductions. The bride and groom often met for the first time under the chuppah, the wedding canopy. In Batya’s case, the parents had a chance to meet the potential “groom” in person and be extremely impressed. Unfortunately, Batya’s unsophisticated, trusting father, like most Jews at the time, falls victim to a trafficker’s sleek double-talk. Even Batya’s no-nonsense mother is seduced by the stranger’s gifts and promises. In Batya’s love for her parents, she lets their excitement push aside the natural trepidations any fourteen-year-old would ordinarily feel.

Yitzik Moskowitz is only one representative of Zwi Migdal, but since he is the one who draws Batya into the trafficking scheme, what can you tell us about him? How does he live with himself?

Yitzik Moskowitz views himself as a successful entrepreneur who spots a need in the market and is smart enough to know how to fill it. He is proud of his ability to find and sort the right “merchandise” and of the many skills that let him demonstrate his ability to do his job well. According to him, pimping is “a profession that demands the whole of you—your character, your perseverance, and your expertise in many areas, from finance to personal hygiene.” For him, running his operation means being “a skilled manager and a comforter of hysterical females.” He does not concern himself with why the females are “hysterical,” because he justifies his actions by the fact that, in the end, he’s taken the girls and women out of the starvation of Eastern Europe and its bloody anti-Semitism and given them a better life.

Interestingly, many “family men” like Moskowitz sent their sons to boarding schools in Europe, where the youngsters acquired a good secular education, made contacts with sons of elite families, cleansed themselves from their families’ foreign accents, and returned to live in South America as upstanding citizens working in noncontroversial businesses.

How did you track down Zwi Migdal’s history, as well as the broader story of legal prostitution in Argentina and its effect on sex trafficking from Eastern Europe between 1870 and 1939? And having done the research, how did you pare it down to keep it from taking over the book?

Once I knew the name of the organization, I found a tremendous amount of information available in translated documents, nonfiction books, and academic publications. Armed also with photos from that time and place, my imagination took a short leap to paint the pictures that brought the material to life: I could hear the sounds, smell the smells, feel the weather on my skin, and view entire scenes. Most importantly, once I sat in front of my computer, the emotions related to Batya’s difficult situation flowed directly into the keyboard, seemingly without first sifting through my brain.

Over the previous years, I had been to Buenos Aires three times, but I don’t know Spanish. I hired two freelance researchers in Argentina, and since the story had taken place in the late 1800s, I had them identify for me specific buildings in photos. For even finer texture, I presented both researchers—a man and a woman—with the same questions about clothes, food, and architecture and was able to extrapolate more nuanced details when crossing their answers. If Batya walked from point A to point B, I had my researchers verify the names of the streets 120 years earlier.

For historical accuracy, I consulted the director of Jewish archives in Buenos Aires, who, thankfully, knew English. She also read the final manuscript.

Once the protagonist, Batya, started dancing tango, what choice did I have but to learn it myself? I needed to write with authenticity about tango—and the complex passions associated with this form of dance. For almost a year I took private tango lessons and occasionally spent an evening at a milonga in a close embrace with total strangers (also my reason to quit tango once my research was done).

The challenge of paring down a mountain of information presented itself in every scene and every chapter. I stayed inside Batya’s head and reported only what she saw, experienced, or knew. I never stepped out from backstage to whisper to the reader in my authorial voice…. I thought I had done a good job of trimming the material until my editor, with her magic wand—or ruthless pen—chopped out more paragraphs and even a few scenes, resulting in a manuscript that—I had to admit—sparkled.

After considering suicide early on, of necessity Batya finds a way to cope with the terrible situation in which Zwi Migdal places her. What keeps her going?

Batya’s love for her family and her promise to take them out of the hell of Russia is her motivation to make the sacrifice and keep on living in her own private hell. Little by little, we also watch as her faith in God returns. Not fully—she’s forever perplexed about His plans and intentions—but she always assumes His presence. The realization of her hope can only be accomplished if He wishes it so, and as events turn and seemingly progress in her favor, she begins again to view His benevolence.

What will your next project be?

All I can say is that a road sign I glimpsed in France three years ago has brought me back there four times already to research a historical event. Like my previous novels, this event has not yet been explored in fiction. Now I must wait a year or two for a large window of time to open in my busy book tour, book groups’ chats, and interviews schedule to actually write this novel.

Talia, thank you so much for your rich and full answers to my questions. I wish you all success with The Third Daughter, your previous books, and that French novel to come!

Talia Carner, the former publisher of Savvy Woman magazine, was a lecturer at international women’s economic forums. An award-winning author of five novels and numerous stories, essays, and articles, she is also a committed supporter of global human rights. Carner has spearheaded groundbreaking projects centered on female plights and women’s activism.

Find out more about her at http://www.taliacarner.com, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Photograph of Talia Carner © Robbie Michaels. Reproduced with permission from William Morrow Books.

Published on September 06, 2019 06:00

August 30, 2019

Aging Heroes

One of the interesting problems some authors tackle is that of aging—or maturation, although the two concepts are not inextricably linked and certainly not the same thing. Even in my Legends of the Five Directions novels, I had to consider how marriage or motherhood or the experience of war would change my characters.

One of the interesting problems some authors tackle is that of aging—or maturation, although the two concepts are not inextricably linked and certainly not the same thing. Even in my Legends of the Five Directions novels, I had to consider how marriage or motherhood or the experience of war would change my characters.But those novels covered five years. Linnea Hartsuyker’s Golden Wolf trilogy, set in Viking Norway, ranges over twenty. In the ninth century, a man could go from youth to old age in that time.

It’s not true, as is often believed, that the human life span was shorter then. Many more children died before the age of five, and those who did not had to survive disease and childbirth or warfare, depending on gender. That pulled the averages down. Nevertheless, a person could live to be eighty even in the premodern world, although given the standards of medical care he or she needed excellent genes and a large dose of luck.

This is one of several topics that Linnea and I discuss in my latest interview on New Books in Historical Fiction. So give it a listen and find out how she handled the emotional and physical changes that beset her aging heroes, fourteen years after the end of her second book, The Sea Queen, and twenty after The Half-Drowned King.

And if you purchase the paperback edition of The Sea Queen (and the future paperback edition of The Golden Wolf—not the UK edition currently listed on Amazon), you’ll find at the back a written Q&A conducted by yours truly. The one on The Sea Queen ran originally on this blog last year. But The Golden Wolf interview will be brand-new, so do look for it when the paperback comes out.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

When I spoke with Linnea Hartsuyker back in 2017, her epic saga was just beginning. The first novel opens with her hero, Ragnvald, seeing a vision of a golden wolf who will unite the feuding kingdoms of Norway under one rule. The vision sets the course of Ragnvald’s life, bringing him into the service of Harald Fair-Hair, a young and confident warrior whose counselor and friend Ragnvald becomes. Meanwhile, Ragnvald’s sister, Svanhild, sets off on a different course, one that offers her a life of adventure not often available to women but pits her against her beloved brother.

When I spoke with Linnea Hartsuyker back in 2017, her epic saga was just beginning. The first novel opens with her hero, Ragnvald, seeing a vision of a golden wolf who will unite the feuding kingdoms of Norway under one rule. The vision sets the course of Ragnvald’s life, bringing him into the service of Harald Fair-Hair, a young and confident warrior whose counselor and friend Ragnvald becomes. Meanwhile, Ragnvald’s sister, Svanhild, sets off on a different course, one that offers her a life of adventure not often available to women but pits her against her beloved brother.Twenty years later, Harald has come close to achieving his goal. One more wedding stands between him and a unified Norway. Svanhild and Ragnvald have returned to fighting on the same side, but two decades of wounds and battles, as well as old patterns, are catching up with the older generation. And the three of them have produced a large and varied group of children, most of them sons at or near adulthood, ready to challenge their parents’ ways and dreams. As fathers struggle with sons, mothers with daughters, brothers and cousins among themselves, and husbands with wives and concubines, Ragnvald stubbornly clings to the force of his vision and his dedication to the principles that have guided his life.

Like its predecessors, The Half-Drowned King and The Sea Queen, The Golden Wolf seamlessly blends Old Norse folklore with creative imagination to paint a picture of ninth-century Norway from the inside. Linnea Hartsuyker assembles a cast of characters that, however different they and their world may appear to a modern readership, tackles problems we all can recognize.

Published on August 30, 2019 06:00

August 23, 2019

The Red Pearl

Once in a while, life gets in the way of my writing, and that’s been the case for the last month or more. Too many work projects with tight deadlines, a couple of new Five Directions Press titles in the works, four New Books Network interviews over the course of five weeks—I’ve barely had time to keep up this blog, never mind work on the outline for my joint project with P. K. Adams or Songs of Steppe & Forest 2 and 3.

All good stuff, of course, but time consuming. So it was a happy accident to receive an e-mail from Chloe Helton, eager to talk about her new historical novel, The Red Pearl . So without more ado, let me turn over the virtual mike to her, and she’ll provide a quick introduction and excerpt.

* * *

Thank you, Carolyn, for allowing me to share The Red Pearl with your readers!

Thank you, Carolyn, for allowing me to share The Red Pearl with your readers!

If you’re hoping to finish off your summer with a crackling, suspenseful read, take a peek at an excerpt of The Red Pearl. You’ll find a marriage on the rocks, a little bit of lost love, the trials of wartime, and the main event—espionage.

During the American Revolution, a meek innkeeper’s wife, Lucy Finch, becomes privy to some explosive secrets. Read more below! And if you want the rest of the book, you can visit my website or find it on Amazon.

Boston, 1778

For a moment, when I woke up, I was back at home. My mother had started to boil water for the porridge, and the faint smell of cinnamon shimmered near my nose. My father’s heavy boots sounded on the steps, and he hummed as he went down. My father was always humming, just as my mother was always praying. Between the two of them, his song and her prayer, there was never silence in the house.

But I wasn’t at my father’s home anymore, and it was silent now. I hadn’t lived with my parents in almost six years. When I married Jasper, I’d vowed never to speak to my father again, and although I had eventually broken that promise, I still kept my distance. When Ma got sick in ’77, the bitterest winter I’d ever lived through, I stayed there awhile to help her. Not much since then.

No, I was not at home. Jasper’s arms were around me, his body the only warmth in our bed now that we were nearing winter, his face nuzzled in my hair. In the beginning, I told myself it was only for warmth that I let him wrap around me like a parasite, but now we did it every night, even during the summer. I’d begun to accept it, just like I now tolerated the rough taste of stone fence, a drink of hard cider and rum, now that I was a tavern-keeper’s wife.

When I started to move, Jasper mumbled something. He wasn’t much of an early riser, but the sun was splashing through the windows now and we couldn’t let the guests wake before us. It had become my responsibility to make sure of that. “Up,” I urged, nudging his shoulder. “Imagine if Robby gets in the kitchen before we do.”

Now he blinked. Robby, our hired boy, was an honest worker, but he was useless without direct and clear orders. If he tried fiddling with the pots and pans without my direction, they’d all be broken before we even made it downstairs. “Didn’t we just fall asleep?” he groaned.

“Oh, enough. You’re terrible in the morning.”

“Come back down,” he said, wrapping an arm around my waist to pull me. “Lay next to me just a minute longer.”

I couldn’t have resisted, really, even if I wanted to. He was too strong. I brushed a hand through his clipped black hair. There had been days when I yearned for another kind of man, shaggy blonde hair and sharp blue eyes, but although he crossed my mind every day, almost, he was now little more than a ghost swirling in the morning fog. I was here with Jasper, who was dark and quiet and excruciatingly clean-shaven. There was drink to brew and mouths to feed here and I wasn’t a girl anymore.

“Jasper,” I said. I hadn’t been planning to mention this, but he was the one who pulled me back down to bed. “Are you planning to let those Tory meetings go on long?”

“What d’you mean?” he mumbled, his eyes barely open. “If they pay for it, they can have their meetings. And you shouldn’t call them that.”

It had been a long while since the word “Tory” was something to gape at. A group of half-a-dozen men had been holding clandestine late-night meetings in our pub for the past few weeks, and you couldn’t tell by looking at them but the various chatter that caught my ears as I poured their drinks made things clear. Nobody who supported the revolution called the Continental army “rebels” and “hooligans”. It was unclear what they met about, but their leanings were no mystery, at least not to me.

“They might scare the others away, is all I mean. You know how our city is; think what would become of us if our neighbors discovered loyalists under our roof.” In Boston, of all places, it was no good to play both sides.

He rubbed his eyes, apparently realizing that he actually had to participate in this conversation. “We don’t know that for certain. All that matters is that they’re fine customers. Pay on time, leave coins on the bar for us when they leave, and they don’t shout and fight like the patriots do. It wouldn’t be so bad if we scared off a few radicals, now would it?”

He’d never listen. Jasper Finch refused to take a side in the war, and yet it was impossible not to. We had married while the harbor was closed after the Tea Party, and I’d watched him buy smuggled rum and sugar, because if the Crown had its way we would all have dry throats and empty bellies: fair retribution, in their eyes, for our act of rebellion. So the rum had to be snuck in bales of hay, among other methods, and Jasper struggled for months with the books in order to keep bringing those goods in. And yet, he claimed to be neutral, as if such a thing were possible in Boston, where the spark of revolution had first been lit, and where it still echoed through the streets even after every last redcoat had scampered away in terror behind General Howe.

To house Tories in our inn, even if he was doing naught more than accept their business, wouldn’t do him well. There was no city that hated the British more than ours. “I suppose not,” I lied. “I know it’s best to be neutral.”

“Neutral,” he repeated, satisfied. “That will get us through this.”

I remembered my father saying much the same. Jasper knows not to pick sides, he’d told me, unlike that boy of yours. And that was why I was in this soft bed in a tavern called The Red Pearl rather than with Sam on the battlefield, wiping sweat from my forehead as I threw pitchers of water on the cannons. My father had not wanted that life for me, so I was here.

“Well, I suppose it is time,” Jasper said finally, grunting as he pulled himself out of bed. “Sometimes I wish I could sleep all day.”

Funny, because in this place, where the dusty wooden walls closed us off from the war that raged outside, it seemed we were asleep all day. “Someday, when we’re very old and we have a son and a sweet daughter-in-law to take care of us, we’ll do just that. Sleep from dawn till dusk.”

“With you, I would,” he smiled.

My heart skittered, and he pecked me on the cheek. “I hope Robby hasn’t tried to make porridge already.”

“God’s bones,” Jasper cursed. “It would taste like pig slosh.”

With that, we hurried downstairs.

Hungry for the next chapter? Click here to get a new chapter in your inbox every week, or find it on Amazon!

Thank you, Chloe. I wish you all success with your novel!

All good stuff, of course, but time consuming. So it was a happy accident to receive an e-mail from Chloe Helton, eager to talk about her new historical novel, The Red Pearl . So without more ado, let me turn over the virtual mike to her, and she’ll provide a quick introduction and excerpt.

* * *

Thank you, Carolyn, for allowing me to share The Red Pearl with your readers!

Thank you, Carolyn, for allowing me to share The Red Pearl with your readers!If you’re hoping to finish off your summer with a crackling, suspenseful read, take a peek at an excerpt of The Red Pearl. You’ll find a marriage on the rocks, a little bit of lost love, the trials of wartime, and the main event—espionage.

During the American Revolution, a meek innkeeper’s wife, Lucy Finch, becomes privy to some explosive secrets. Read more below! And if you want the rest of the book, you can visit my website or find it on Amazon.

Boston, 1778

For a moment, when I woke up, I was back at home. My mother had started to boil water for the porridge, and the faint smell of cinnamon shimmered near my nose. My father’s heavy boots sounded on the steps, and he hummed as he went down. My father was always humming, just as my mother was always praying. Between the two of them, his song and her prayer, there was never silence in the house.

But I wasn’t at my father’s home anymore, and it was silent now. I hadn’t lived with my parents in almost six years. When I married Jasper, I’d vowed never to speak to my father again, and although I had eventually broken that promise, I still kept my distance. When Ma got sick in ’77, the bitterest winter I’d ever lived through, I stayed there awhile to help her. Not much since then.

No, I was not at home. Jasper’s arms were around me, his body the only warmth in our bed now that we were nearing winter, his face nuzzled in my hair. In the beginning, I told myself it was only for warmth that I let him wrap around me like a parasite, but now we did it every night, even during the summer. I’d begun to accept it, just like I now tolerated the rough taste of stone fence, a drink of hard cider and rum, now that I was a tavern-keeper’s wife.

When I started to move, Jasper mumbled something. He wasn’t much of an early riser, but the sun was splashing through the windows now and we couldn’t let the guests wake before us. It had become my responsibility to make sure of that. “Up,” I urged, nudging his shoulder. “Imagine if Robby gets in the kitchen before we do.”

Now he blinked. Robby, our hired boy, was an honest worker, but he was useless without direct and clear orders. If he tried fiddling with the pots and pans without my direction, they’d all be broken before we even made it downstairs. “Didn’t we just fall asleep?” he groaned.

“Oh, enough. You’re terrible in the morning.”

“Come back down,” he said, wrapping an arm around my waist to pull me. “Lay next to me just a minute longer.”

I couldn’t have resisted, really, even if I wanted to. He was too strong. I brushed a hand through his clipped black hair. There had been days when I yearned for another kind of man, shaggy blonde hair and sharp blue eyes, but although he crossed my mind every day, almost, he was now little more than a ghost swirling in the morning fog. I was here with Jasper, who was dark and quiet and excruciatingly clean-shaven. There was drink to brew and mouths to feed here and I wasn’t a girl anymore.

“Jasper,” I said. I hadn’t been planning to mention this, but he was the one who pulled me back down to bed. “Are you planning to let those Tory meetings go on long?”

“What d’you mean?” he mumbled, his eyes barely open. “If they pay for it, they can have their meetings. And you shouldn’t call them that.”

It had been a long while since the word “Tory” was something to gape at. A group of half-a-dozen men had been holding clandestine late-night meetings in our pub for the past few weeks, and you couldn’t tell by looking at them but the various chatter that caught my ears as I poured their drinks made things clear. Nobody who supported the revolution called the Continental army “rebels” and “hooligans”. It was unclear what they met about, but their leanings were no mystery, at least not to me.

“They might scare the others away, is all I mean. You know how our city is; think what would become of us if our neighbors discovered loyalists under our roof.” In Boston, of all places, it was no good to play both sides.

He rubbed his eyes, apparently realizing that he actually had to participate in this conversation. “We don’t know that for certain. All that matters is that they’re fine customers. Pay on time, leave coins on the bar for us when they leave, and they don’t shout and fight like the patriots do. It wouldn’t be so bad if we scared off a few radicals, now would it?”

He’d never listen. Jasper Finch refused to take a side in the war, and yet it was impossible not to. We had married while the harbor was closed after the Tea Party, and I’d watched him buy smuggled rum and sugar, because if the Crown had its way we would all have dry throats and empty bellies: fair retribution, in their eyes, for our act of rebellion. So the rum had to be snuck in bales of hay, among other methods, and Jasper struggled for months with the books in order to keep bringing those goods in. And yet, he claimed to be neutral, as if such a thing were possible in Boston, where the spark of revolution had first been lit, and where it still echoed through the streets even after every last redcoat had scampered away in terror behind General Howe.

To house Tories in our inn, even if he was doing naught more than accept their business, wouldn’t do him well. There was no city that hated the British more than ours. “I suppose not,” I lied. “I know it’s best to be neutral.”

“Neutral,” he repeated, satisfied. “That will get us through this.”

I remembered my father saying much the same. Jasper knows not to pick sides, he’d told me, unlike that boy of yours. And that was why I was in this soft bed in a tavern called The Red Pearl rather than with Sam on the battlefield, wiping sweat from my forehead as I threw pitchers of water on the cannons. My father had not wanted that life for me, so I was here.

“Well, I suppose it is time,” Jasper said finally, grunting as he pulled himself out of bed. “Sometimes I wish I could sleep all day.”

Funny, because in this place, where the dusty wooden walls closed us off from the war that raged outside, it seemed we were asleep all day. “Someday, when we’re very old and we have a son and a sweet daughter-in-law to take care of us, we’ll do just that. Sleep from dawn till dusk.”

“With you, I would,” he smiled.

My heart skittered, and he pecked me on the cheek. “I hope Robby hasn’t tried to make porridge already.”

“God’s bones,” Jasper cursed. “It would taste like pig slosh.”

With that, we hurried downstairs.

Hungry for the next chapter? Click here to get a new chapter in your inbox every week, or find it on Amazon!

Thank you, Chloe. I wish you all success with your novel!

Published on August 23, 2019 06:00