C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 26

June 7, 2019

A Web of Images

One of my guilty pleasures is cover design. Although that’s not my official responsibility at Five Directions Press—I handle copy-editing, book design, and typesetting, whereas our covers are in the capable hands of Courtney J. Hall, who knows her way around Photoshop better than I ever will—I’ve come up with ideas for the covers of all my own novels except for the current version of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel. That last is Courtney’s, and the moment I saw it I fell in love with it. She also produced those beautiful fonts for the Songs of Steppe & Forest series, and she’s the person I tap for suggestions, critiques, and the final go-ahead, since no cover goes onto a Five Directions Press book without her approval.

One of my guilty pleasures is cover design. Although that’s not my official responsibility at Five Directions Press—I handle copy-editing, book design, and typesetting, whereas our covers are in the capable hands of Courtney J. Hall, who knows her way around Photoshop better than I ever will—I’ve come up with ideas for the covers of all my own novels except for the current version of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel. That last is Courtney’s, and the moment I saw it I fell in love with it. She also produced those beautiful fonts for the Songs of Steppe & Forest series, and she’s the person I tap for suggestions, critiques, and the final go-ahead, since no cover goes onto a Five Directions Press book without her approval.That said, in my spare time I love to explore images and their potential as book covers. I have covers for books I may not write for years, the stories of which are limited to a main character, a love interest (maybe), and a vague goal. The cover, like the title and the cork boards filled with character images that sit next to my manuscripts on screen, are essential writing tools. They spark thoughts and symbols, emotions and descriptions, themes and personalities. My primary approach to the world is visual: change a character’s picture, and I develop a new sense of that character’s essential self.

So where do I find the images for my covers? For sure, Shutterstock loves me, because I spend far too much of my not so generous royalties there. Pixabay, with its ever-growing store of royalty-free photographs, is fantastic as well. But for Songs, as you can see from the Song of the Siren cover to the right, I decided to go with public domain art from nineteenth-century Eastern Europe and Russia.

Public domain art has one big advantage: unless owned by a museum or library that chooses to assert its rights, it can often be used without copyright issues and free of charge. But it also has one huge disadvantage: many of the files available online are too small and too fuzzy for a book cover. By the time you blow the image up to the minimum needed for a trade paperback, what you have left is a collection of visible dots. E-books, being computer-based, have a greater tolerance for poor image quality, but even an e-book cover can look unacceptable if the original picture is too small.

Public domain art has one big advantage: unless owned by a museum or library that chooses to assert its rights, it can often be used without copyright issues and free of charge. But it also has one huge disadvantage: many of the files available online are too small and too fuzzy for a book cover. By the time you blow the image up to the minimum needed for a trade paperback, what you have left is a collection of visible dots. E-books, being computer-based, have a greater tolerance for poor image quality, but even an e-book cover can look unacceptable if the original picture is too small.As it happens, I got lucky with most of the Songs covers. The one for Song of the Siren comes from a large file readily available on Wikimedia Commons and via the National Museum of Warsaw. Most of the others come from Wikimedia Commons as well. And in the process of tracking them down, I learned quite a bit about Russian realist art and the group known as the Wanderers and a good deal more besides. That in itself has become a great source of pleasure.

Song of the Shaman gave me fits, though, not least because nineteenth-century Russian artists didn’t paint a lot of shamans. After weeks of searching, I found one painting by a Polish artist resident in the Russian Empire, but no matter what I did, I couldn’t track down a version of the file that was usable for a book cover. I even purchased a personal license from a stock photo site for a high-resolution image of the painting, wanting to check it out before I decided whether it would be worth the higher charge for publishing use, only to discover that the high-resolution version looked worse than the doctored (but too small) Wikimedia Commons file. Missing paint, dull covers, too little contrast between the frame and the art, you name it: the problems added up to a series of flaws that either lay beyond the bounds of even Photoshop’s magic or would take so much time to fix that the end product wouldn’t be worth the effort expended.

So with a sigh of regret I gave up that idea. And I’m glad I did, because not long afterward I remembered another painting from circa 1905, perhaps not so obviously a shaman but still appropriate to the book’s theme (and, not coincidentally, a perfect depiction of its heroine, Grusha). And when I searched Wikimedia Commons, after a couple of tries I discovered a version large enough that I could compress it into a nice, sharp image without Photoshop doing what it typically does during compression: adding fake dots of its own. I had to tweak the colors and position the painting just right and even airbrush out a hand, but the results are exactly what I hoped for.

And soon you’ll get to see it. But I’m not quite ready for a cover reveal yet. First I have to ensure that the novel itself is ready for prime time. Then I need to work with the other authors in Five Directions Press to figure out the best publication schedule. By September, though, I hope to have a complete text and a plan. Stay tuned!

Images purchased by subscription from iClipart.com.

Published on June 07, 2019 06:00

May 31, 2019

Crossing the Streams

It’s ages since I last saw Ghostbusters, but there are still lines I remember with fondness. The title of this post recalls one of them.

In the movie, crossing the streams is a bad thing. The term refers to the streams of energy emitted by the ghostbusters’ weapons, and crossing them has awful if unspecified (at least, I remember the threat as being unspecified) consequences.

But in real life, crossing streams—in the sense of bringing in a different perspective–allows people to see what they might otherwise miss. This point was brought back to me recently in an unexpected way.

As I mentioned last week, the novelist P. K. Adams and I are planning a joint project. As part of the initial stages, we are outlining general ideas for the plot and dividing the main characters between us. But this is historical fiction, and even for a historian that means research. No one can anticipate the answer to every question that might arise, and in this case I’m very familiar with one side of the story (although I’m researching that too!) and have at most a general knowledge of the other.

So not to give too much away at this early stage—in part because the story is still in flux, so who knows where it will ultimately go?—I was reading a set of documents about Tudor England that happened to include letters from Ivan IV “the Terrible” (r. 1533–84) to King Philip of Spain and his wife, Mary Tudor, as well as Mary’s successor and sister, Elizabeth I.

The correspondence in itself is not news: I first heard about it as an undergrad—not least because the story behind it was too good to leave out of a survey course: Ivan IV, having wreaked havoc on his own land, was trying to arrange a bolt hole in case the people at home lost patience with him to the point that he had to flee if he wanted to keep his head. And Elizabeth, in particular, assured Ivan several times that he could, if he wanted, find a refuge in England. She promised financial support and even a guarantee that no one would attempt to convert him from his own Russian Orthodoxy to Protestantism.

The correspondence in itself is not news: I first heard about it as an undergrad—not least because the story behind it was too good to leave out of a survey course: Ivan IV, having wreaked havoc on his own land, was trying to arrange a bolt hole in case the people at home lost patience with him to the point that he had to flee if he wanted to keep his head. And Elizabeth, in particular, assured Ivan several times that he could, if he wanted, find a refuge in England. She promised financial support and even a guarantee that no one would attempt to convert him from his own Russian Orthodoxy to Protestantism.Whether she meant any of it, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know. But that’s not the point. Because I had heard of Ivan’s requests for asylum but never read the actual letters, I’d accepted the usual conclusion: that Ivan felt an exceptional closeness to the kings and queens of England, expressed by his use of the terms “brother” and “sister” in reference to them.

But as soon as I read the letters from the perspective of a historian of Muscovy, I knew that the usual assumption was untrue—or at least unproven. Ivan is not particularly cordial in his missives to the English court (that is, the letters produced on his behalf by his clerks). He chides Elizabeth, in particular, for focusing too much on the mercantile interests of her own ignoble subjects at the expense of princely affairs. He repeatedly emphasizes, in a manner one can only consider derisive, that she is a “maid” (that is, a virgin) who hides behind her maiden state and gives her counselors free rein. Indeed, as a never-married royal woman ruling in her own name, Elizabeth must have seemed completely unnatural to Ivan despite his own mother’s (ultimately unsuccessful) grab for power.

So where do the “brothers” and “sisters” come in? The same place that the “crossing streams” come in. The men (and they were all men) who wrote Ivan’s letters for him were trained in the formulas of steppe diplomacy, like all the other bureaucrats and bureaucracies that emerged from the remnants of Genghis Khan’s empire. And those formulas drew heavily on the fictive kinship that determined power relations in the nomadic hordes. In the early years, Muscovite princes addressed the Mongols as “fathers” and described themselves as grateful, obedient “sons.” After the conquests of the mid-sixteenth century, the tsars became the “fathers” and the high-ranking descendants of Genghis were demoted to “sons.” But in the middle—and in general between states regarded as equal—rulers addressed each other as “brother” and, in the case of the strange English with their Tudor queens, “sister.”

That’s all it means: no special closeness at all, just a recognition of equality. A similar origin lies behind the odd description of Russia and its ruler, in other letters directed at European powers, as “white” (a usage retained in today’s Belarus—White Russia). That comes from steppe diplomacy too, and it has nothing to do with race. In Chinese—and therefore Turkic—cosmology, “white” is the color associated with the west. We think of Russia as an eastern state, barely part of Europe, but if your center is located at Karakorum or Sarai, Russia is almost as far west as you can imagine.

That’s all it means: no special closeness at all, just a recognition of equality. A similar origin lies behind the odd description of Russia and its ruler, in other letters directed at European powers, as “white” (a usage retained in today’s Belarus—White Russia). That comes from steppe diplomacy too, and it has nothing to do with race. In Chinese—and therefore Turkic—cosmology, “white” is the color associated with the west. We think of Russia as an eastern state, barely part of Europe, but if your center is located at Karakorum or Sarai, Russia is almost as far west as you can imagine.And that’s why it sometimes pays to cross the streams. Strange things may emerge from the shadows, and not all of them are scary.

Images: ghost with placard (edited in Photoshop), iClipart.com, no. 294239; Viktor Vasnetsov, Ivan the Terrible (1897), public domain via Wikimedia Commons; white tiger (symbol of the west), iClipart.com no. 311747 (iClipart images purchased via subscription).

Published on May 31, 2019 06:00

May 24, 2019

The Discipline of Outlining

As I mentioned a couple of months ago, I’ve been discussing the possibility of a joint writing project with P. K. Adams, aka Patrycja Podrazik. It seemed too good a coincidence of interests to waste: how many other authors in the United States have written novels set during the reigns of King Sigismund (Zygmunt) the Old of Poland and his co-ruling son, Sigismund Augustus (Zygmunt August)? How many other novelists could even name the major figures at the sixteenth-century Polish-Lithuanian court?

As I mentioned a couple of months ago, I’ve been discussing the possibility of a joint writing project with P. K. Adams, aka Patrycja Podrazik. It seemed too good a coincidence of interests to waste: how many other authors in the United States have written novels set during the reigns of King Sigismund (Zygmunt) the Old of Poland and his co-ruling son, Sigismund Augustus (Zygmunt August)? How many other novelists could even name the major figures at the sixteenth-century Polish-Lithuanian court?Well, now that Song of the Shaman has had its final revisions, although it won’t appear until early next year, and Patrycja’s Silent Water is close to publication, we’re getting serious about our joint project. Silent Water takes place almost twenty-five years earlier than my Song of the Siren, starting right after the marriage of Bona Sforza to Sigismund the Old in 1518. Still, a quarter-century is not much of a difference when we’re talking about events 450 years in the past, and Patrycja is a lovely writer, so if you enjoy my novels, you should definitely seek out hers. Silent Water is a murder mystery, much more puzzle than gore—and let’s just say that Juliana and Felix would feel quite at home in its world.

By now, you’re probably wondering what all this has to with outlining. Or was I just losing it when I came up with the post title? I have, after all, written before about why I seldom outline my novels, not least because it rarely turns out to be a worthwhile use of my writing time. Sure, I like to establish a goal my characters can aim for, and I certainly put some effort into figuring out who they are and what they want. But beyond that, I like to throw them into the thick of the action and see what they do and say; that’s how I find out who they are and, as a result, figure out where the story needs to go to reach that predetermined goal and how it can realistically get there.

Which is fine for me, of course, but for collaboration the free-form approach doesn’t work so well. As co-writers, Patrycja and I need to decide who’ll write what and where to start, not to mention where we’re heading and what paths to take. Even the research is shared, because she knows more about Poland and I about Muscovy. So there’s not much point in duplicating our efforts, especially since she reads Polish whereas I read Russian, meaning that each of us has access to sources barred to the other. In short, we have to plan, because the “tumble into the story and see where it goes” approach is likely to take us both into a thick forest where we wander about in circles with no hope of reaching our destination.

Patrycja, bless her, is a far more disciplined writer than I am (perhaps that’s why she can write murder mysteries, whereas my books tend to orient themselves to espionage and romance). So we’re constructing an outline—in the literary sense of paragraphs telling a story that will ultimately run to ten or even twenty pages, not the 1.A.b.* one-page wonder most of us learned in middle school. We worked out the main points over the phone; we hope to meet in person soon to flesh things out; meanwhile, we go back and forth via e-mail as suits our individual work and writing schedules. Right at this moment, the ball is in my court, which explains why this topic is on my mind.

Patrycja, bless her, is a far more disciplined writer than I am (perhaps that’s why she can write murder mysteries, whereas my books tend to orient themselves to espionage and romance). So we’re constructing an outline—in the literary sense of paragraphs telling a story that will ultimately run to ten or even twenty pages, not the 1.A.b.* one-page wonder most of us learned in middle school. We worked out the main points over the phone; we hope to meet in person soon to flesh things out; meanwhile, we go back and forth via e-mail as suits our individual work and writing schedules. Right at this moment, the ball is in my court, which explains why this topic is on my mind.So far it’s been fun, as I think about how Character A would respond to Plot Point B or strip in Cultural Information C to explain what makes Plot Point B possible. Kind of like my usual free-form writing without the dialogue and detailed settings. And I’m sure it’s a good exercise, for me as well as for our project.

Will I be able to stick to the outline once the writing starts? Ah, that’s much more difficult to predict. If I do, it will certainly be a first. I have to hope I don’t drive Patrycja crazy with my stops and starts and rethinks. But if the outline is strong enough, maybe I’ll get the dithering out in the planning stages and learn something new—about writing and about myself. So wish me luck!

As for the project itself, it’s new and barely formed, so we want to keep it under wraps for a while. Let’s just say that it will be a murder mystery—the first of three, if all goes well—and it will involve not only Russians and Poles but a few wandering Englishmen. The ship depicted at the top of the post might be considered a clue. Gotta appeal to that Tudor fan base somehow....

While you’re waiting, check out Patrycja’s two-part series on Hildegard of Bingen, The Greenest Branch and The Column of Burning Spices. Silent Water will be available for preorder on June 15 (release date August 6), but you can get a sneak peek of the prologue on P. K. Adams’ website, as well as information about the earlier books. And while you’re there, check out the lovely review she wrote (unasked!) about The Shattered Drum. You can see why we decided that we might just be kindred novel-writing souls.

Images: 16th-century painting of The Great Harry, an English carrack, by an unknown artist; Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Sigismund I the Old (1768–71). Both public domain because of the date of their creation, via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on May 24, 2019 06:00

May 17, 2019

The Power of Conscience

What would you do to protect your friends and family from danger? This is the question that confronts Deborah Tyler and her stepbrother-in-law Nels Anderson in Ann Weisgarber’s new novel,

The Glovemaker

. As Weisgarber explains in our interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, the small community of Junction, Utah—eight families, including Deborah’s—often receives fugitives from the law.

What would you do to protect your friends and family from danger? This is the question that confronts Deborah Tyler and her stepbrother-in-law Nels Anderson in Ann Weisgarber’s new novel,

The Glovemaker

. As Weisgarber explains in our interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, the small community of Junction, Utah—eight families, including Deborah’s—often receives fugitives from the law.Most of the men are God-fearing Mormons, avoiding trial and certain conviction for the plural marriages that were not crimes when they entered into such arrangements. But a woman alone can never feel certain about the intentions of a stranger pounding at her door—especially in the middle of winter, when no ordinary traveler, polygamist or otherwise, wants to brave the icy rocks and treacherous blizzards that lie between Junction and the rest of Utah Territory.

Even if the visitor is harmless, aiding his escape puts the person who responds to him at risk. So the community exists in a web of secrets in which every member takes a chance on behalf of the others but resists sharing information, so that all concerned can honestly declare their innocence of any wrongdoing.

Balanced on this fulcrum of truth and lies, caring and concealing, responsibility and lawbreaking, Deborah and Nels seek a way to protect themselves and those they love. But as the situation slips ever farther from their control and they find out more about what drove their visitor and his pursuer, they confront a deeper and more timeless question: when does an enemy become just another person who needs help?

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

When a strange man knocks on Deborah Tyler’s door one January evening in 1888, she faces a difficult decision. She can guess that her visitor is a criminal, because who else would travel to her isolated Utah community in the dead of winter? And her husband, who normally handles such situations, left home five months ago and has not returned. She is tempted not to answer, but that will only send the unwanted traveler to the next house in Junction, endangering her younger sister and her sister’s children.

Besides, most of the criminals who arrive on Deborah’s doorstep are not thieves or murderers but polygamists evading arrest for what the US government has recently outlawed as a felony. Deborah has little sympathy for plural marriage or the men who practice it, but she is a loyal Mormon who distrusts those inclined to persecute her faith and cares about the families left destitute when their breadwinners flee.

Deborah makes her choice. But the next day, a federal marshal arrives in pursuit. Threatened with prosecution for aiding and abetting a felon, Deborah fights to protect herself, her community, and those she loves from unpredictable consequences that draw her ever deeper into a web of secrets and lies.

The Glovemaker (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019) asks important questions about love and loyalty, faith and independence, the power of love and of family. And through Deborah and her struggles, Ann Weisgarber brings vividly to life the joys and terrors of life in a small, isolated community on the US frontier, the moral compromises we all face, and the capacity of one strong woman to adapt in a time of rapid change.

Published on May 17, 2019 08:31

May 10, 2019

The Other Front

As I’ve mentioned a few times over the past year, World War II is having its “moment” in terms of historical novels. Admittedly, as the number of shows on the History Channel and nonfiction works attests, World War II has never failed to attract interest from either scholars or the general public. But in the first five years of my podcast, I rarely received pitches for books set during the war. These days, it seems to be the background for every other book that heads my way.

Now, admittedly, I’ve loved some of the books: Gwen Katz’s Among the Red Stars and Kate Quinn’s The Huntress, in particular—both of which explore the lives of the Soviet women pilots who fought so effectively from their flimsy biplanes that their enemies called them the “Night Witches.” Many other authors have also found new and surprising takes on this well-worn subject. Almost without exception, though, the WWII novels that crossed my desk in the last fifteen months or so have focused on the European side of the conflict.

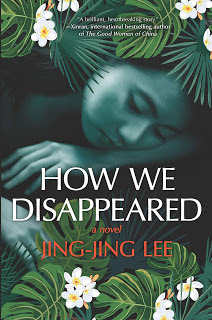

Not so the two I’m chatting about today. Jing-Jing Lee’s

How We Disappeared

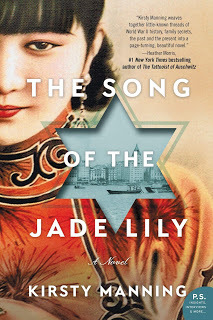

(Hanover Square Press, 2019) and Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

(William Morrow, 2019) have little in common except a dual-time framework in which a young person searches for hidden information about what happened to his/her family during the war and a release date this month. But both explore the war on the Pacific Front and how it affected women who became caught up in the dangers of living in occupied territory.

Not so the two I’m chatting about today. Jing-Jing Lee’s

How We Disappeared

(Hanover Square Press, 2019) and Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

(William Morrow, 2019) have little in common except a dual-time framework in which a young person searches for hidden information about what happened to his/her family during the war and a release date this month. But both explore the war on the Pacific Front and how it affected women who became caught up in the dangers of living in occupied territory.

Much of How We Disappeared takes place in Singapore, not a location we in the United States often think about in terms of WWII, between 1941 and 1945. This part of the story follows the life of Wang Di, eldest daughter of a Chinese family that emigrated to escape poverty and whose homeland has since fallen under Japanese control. Her name means “Hope for a Brother,” a constant reminder that she can never equal in importance the sons her parents eventually produce. Even so, her family protects her from the invading Japanese army, first by trying to arrange a marriage for her and later by keeping her within the confines of their house, until one drastic mistake leads to Wang Di’s capture. A seventeen-year-old virgin, she is loaded onto a truck, carted away to a house, and forced into service as a “comfort woman.” From then until the end of the war, Wang Di never knows whether she will survive the night, or whether she wants to.

This harrowing tale is interwoven with a second story from 2012, in which Kevin, aged twelve, learns of a secret from his dying grandmother. In this more contemporary thread, we also see Wang Di in old age. She has a secret of her own to unravel: where her recently deceased husband went every year on February 12. Her secret and Kevin’s are connected—by the personality of Wang Di, of course, but also by the immediate and long-term effects of occupation by a hostile power.

The Song of the Jade Lily, in contrast, takes place mostly in Shanghai. A twenties-something financial whiz named Alexandra accepts a job there, in part to get away from a disintegrating relationship with her boyfriend. Alexandra, of Chinese descent, grew up in the care of her Jewish grandparents, Romy and Wilhelm. After Wilhelm’s death, Alexandra moves to Shanghai, where she makes use of the opportunity thus offered to solve the mystery of her mother’s past and therefore her own. But we readers watch the story unfold from 1938 through 1954, interspersed with moments when Alexandra searches for or stumbles over one truth or another.

The Song of the Jade Lily, in contrast, takes place mostly in Shanghai. A twenties-something financial whiz named Alexandra accepts a job there, in part to get away from a disintegrating relationship with her boyfriend. Alexandra, of Chinese descent, grew up in the care of her Jewish grandparents, Romy and Wilhelm. After Wilhelm’s death, Alexandra moves to Shanghai, where she makes use of the opportunity thus offered to solve the mystery of her mother’s past and therefore her own. But we readers watch the story unfold from 1938 through 1954, interspersed with moments when Alexandra searches for or stumbles over one truth or another.

Because I was a friend of the writer Annabel Liu, who lived in Shanghai as a child, I knew in general about the Japanese occupation of the city and the suffering inflicted on the local population. What I didn’t know was that right before and during the war Shanghai was one of the few places that freely accepted Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution in Europe. Romy and her fictional family are among these refugees.

Not long after the novel opens, Romy loses one brother to murder during Vienna’s version of Kristallnacht and another to the concentration camp at Dachau, although the family members have no idea what conditions in the camp are like and continue to hope that the second son can join them. Meanwhile, they settle into their new home, making friends with Dr. Ho and his two children, Li and Jian—all of whom will play vital roles in Romy’s life.

Here too, the invasion of the Japanese Army threatens to upset the refugees’ hopes for a better future. Romy’s father, a doctor, manages to remain in practice, although as the war drags on, he finds it ever more difficult to secure the medical supplies his patients need. Romy’s fate is kinder than Wang Di’s: she pursues an education and acquires training in both Western and traditional Chinese medicine. Even so, the tendrils of war are everywhere, and they entangle her friends Li and Jian, as well as another friend—Nina, also a refugee—in ways that sweep Romy, too, into the web of power and its abuses.

To say more about either novel would give too much away. Both are well thought through, interesting, nicely written, and innovative in the sense that they look beyond the European theater and recognize that the horrors of World War II didn’t stop at Paris, London, or Stalingrad. Personally, I preferred Song of the Jade Lily, in part because what happens to Wang Di in How We Disappeared—although wholly supported by the historical evidence—is so wrenching and heart-breaking that the problems addressed in the contemporary story pale by comparison. It’s not that the problems are small in themselves—on the contrary. But they can’t quite measure up to the complete dehumanization inflicted on the innocent Wang Di. It might, in the end, have worked better to let her story stand alone. In that sense, the two halves of Jade Lily achieve a better balance.

Your reaction, however, may be just the opposite. Certainly you can’t go wrong with either of these books. If nothing else, you will discover a side of World War II that you may not have imagined. And that’s always a good thing, right?

My thanks to Shara Alexander and Maria Silva, the publicists who sent me copies of these novels with no obligation on me to post a review. As always, the opinions expressed here are entirely my own.

And as I’ve mentioned before, if you have been my friend on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), that will be the main venue for my writing-related posts going forward. I’ve deactivated my Catriona Lesley account, so if you search for it, you will not see my profile. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and @NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Now, admittedly, I’ve loved some of the books: Gwen Katz’s Among the Red Stars and Kate Quinn’s The Huntress, in particular—both of which explore the lives of the Soviet women pilots who fought so effectively from their flimsy biplanes that their enemies called them the “Night Witches.” Many other authors have also found new and surprising takes on this well-worn subject. Almost without exception, though, the WWII novels that crossed my desk in the last fifteen months or so have focused on the European side of the conflict.

Not so the two I’m chatting about today. Jing-Jing Lee’s

How We Disappeared

(Hanover Square Press, 2019) and Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

(William Morrow, 2019) have little in common except a dual-time framework in which a young person searches for hidden information about what happened to his/her family during the war and a release date this month. But both explore the war on the Pacific Front and how it affected women who became caught up in the dangers of living in occupied territory.

Not so the two I’m chatting about today. Jing-Jing Lee’s

How We Disappeared

(Hanover Square Press, 2019) and Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

(William Morrow, 2019) have little in common except a dual-time framework in which a young person searches for hidden information about what happened to his/her family during the war and a release date this month. But both explore the war on the Pacific Front and how it affected women who became caught up in the dangers of living in occupied territory.Much of How We Disappeared takes place in Singapore, not a location we in the United States often think about in terms of WWII, between 1941 and 1945. This part of the story follows the life of Wang Di, eldest daughter of a Chinese family that emigrated to escape poverty and whose homeland has since fallen under Japanese control. Her name means “Hope for a Brother,” a constant reminder that she can never equal in importance the sons her parents eventually produce. Even so, her family protects her from the invading Japanese army, first by trying to arrange a marriage for her and later by keeping her within the confines of their house, until one drastic mistake leads to Wang Di’s capture. A seventeen-year-old virgin, she is loaded onto a truck, carted away to a house, and forced into service as a “comfort woman.” From then until the end of the war, Wang Di never knows whether she will survive the night, or whether she wants to.

This harrowing tale is interwoven with a second story from 2012, in which Kevin, aged twelve, learns of a secret from his dying grandmother. In this more contemporary thread, we also see Wang Di in old age. She has a secret of her own to unravel: where her recently deceased husband went every year on February 12. Her secret and Kevin’s are connected—by the personality of Wang Di, of course, but also by the immediate and long-term effects of occupation by a hostile power.

The Song of the Jade Lily, in contrast, takes place mostly in Shanghai. A twenties-something financial whiz named Alexandra accepts a job there, in part to get away from a disintegrating relationship with her boyfriend. Alexandra, of Chinese descent, grew up in the care of her Jewish grandparents, Romy and Wilhelm. After Wilhelm’s death, Alexandra moves to Shanghai, where she makes use of the opportunity thus offered to solve the mystery of her mother’s past and therefore her own. But we readers watch the story unfold from 1938 through 1954, interspersed with moments when Alexandra searches for or stumbles over one truth or another.

The Song of the Jade Lily, in contrast, takes place mostly in Shanghai. A twenties-something financial whiz named Alexandra accepts a job there, in part to get away from a disintegrating relationship with her boyfriend. Alexandra, of Chinese descent, grew up in the care of her Jewish grandparents, Romy and Wilhelm. After Wilhelm’s death, Alexandra moves to Shanghai, where she makes use of the opportunity thus offered to solve the mystery of her mother’s past and therefore her own. But we readers watch the story unfold from 1938 through 1954, interspersed with moments when Alexandra searches for or stumbles over one truth or another.Because I was a friend of the writer Annabel Liu, who lived in Shanghai as a child, I knew in general about the Japanese occupation of the city and the suffering inflicted on the local population. What I didn’t know was that right before and during the war Shanghai was one of the few places that freely accepted Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution in Europe. Romy and her fictional family are among these refugees.

Not long after the novel opens, Romy loses one brother to murder during Vienna’s version of Kristallnacht and another to the concentration camp at Dachau, although the family members have no idea what conditions in the camp are like and continue to hope that the second son can join them. Meanwhile, they settle into their new home, making friends with Dr. Ho and his two children, Li and Jian—all of whom will play vital roles in Romy’s life.

Here too, the invasion of the Japanese Army threatens to upset the refugees’ hopes for a better future. Romy’s father, a doctor, manages to remain in practice, although as the war drags on, he finds it ever more difficult to secure the medical supplies his patients need. Romy’s fate is kinder than Wang Di’s: she pursues an education and acquires training in both Western and traditional Chinese medicine. Even so, the tendrils of war are everywhere, and they entangle her friends Li and Jian, as well as another friend—Nina, also a refugee—in ways that sweep Romy, too, into the web of power and its abuses.

To say more about either novel would give too much away. Both are well thought through, interesting, nicely written, and innovative in the sense that they look beyond the European theater and recognize that the horrors of World War II didn’t stop at Paris, London, or Stalingrad. Personally, I preferred Song of the Jade Lily, in part because what happens to Wang Di in How We Disappeared—although wholly supported by the historical evidence—is so wrenching and heart-breaking that the problems addressed in the contemporary story pale by comparison. It’s not that the problems are small in themselves—on the contrary. But they can’t quite measure up to the complete dehumanization inflicted on the innocent Wang Di. It might, in the end, have worked better to let her story stand alone. In that sense, the two halves of Jade Lily achieve a better balance.

Your reaction, however, may be just the opposite. Certainly you can’t go wrong with either of these books. If nothing else, you will discover a side of World War II that you may not have imagined. And that’s always a good thing, right?

My thanks to Shara Alexander and Maria Silva, the publicists who sent me copies of these novels with no obligation on me to post a review. As always, the opinions expressed here are entirely my own.

And as I’ve mentioned before, if you have been my friend on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), that will be the main venue for my writing-related posts going forward. I’ve deactivated my Catriona Lesley account, so if you search for it, you will not see my profile. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and @NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Published on May 10, 2019 06:00

May 3, 2019

Investigating the Qing

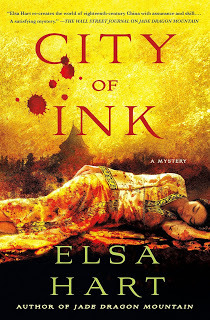

I first discovered Elsa Hart’s novels through my friend Ann Kleimola, who has made so many wonderful suggestions for how to improve first my Legends of the Five Directions and now my Songs of Steppe & Forest novels. “You have to read Jade Dragon Mountain,” she wrote. (I’m paraphrasing: that was the gist of her e-mail, not the text.)

I first discovered Elsa Hart’s novels through my friend Ann Kleimola, who has made so many wonderful suggestions for how to improve first my Legends of the Five Directions and now my Songs of Steppe & Forest novels. “You have to read Jade Dragon Mountain,” she wrote. (I’m paraphrasing: that was the gist of her e-mail, not the text.)To be honest, I’m pretty sure she’d recommended both Jade Dragon Mountain and Elsa Hart when the novel first came out in 2016. I’d meant to follow up, but too many books got in the way, and by the time I cleared the pile, I’d forgotten about this one. But when she mentioned it again, I went after it right away, purchased it as an e-book, and ... devoured it within three days. I was hooked.

I tracked down Elsa and talked her into an interview about the third book, City of Ink. Meanwhile, she sent me the second in the series as well. I read The White Mirror and loved it even more than Jade Dragon Mountain, if that’s possible—not least because it takes place in the mountains separating China from Tibet, a terrain my steppe nomads would appreciate. I can now attest that City of Ink is even better than its predecessors. So you can imagine how much time will lapse between my learning that book 4 has arrived and my starting it—yes, zero minutes would be an excellent guess.

So what makes this series so special? First, there’s the setting, which is unusual yet brought so vividly to life that I felt I could look out the window and see the locked bamboo gates and the exhausted examination candidates lining up, eyes red and quill pens in hand. Second, the characters—always crucial for me—especially Li Du, the calm and thoughtful but persistent librarian detective, and his friend Hamza, a very different and much more dramatic figure who makes his way along the Silk Road through the power of his storytelling. Individual characters in each mystery are also deeply thought out, with believable and often conflicting motives. Third is Li’s own story, which we understand in greater depth with each book.

But fourth and supreme are the puzzles, some of the best I’ve seen and essential to every good mystery novel. It’s rare for an author to give me all the clues yet fool me three times in a row, but Elsa Hart has managed to do exactly that. So listen to our interview, but don’t expect spoilers. Then read the series, in order. I promise you won’t be disappointed.

As ever, the rest of this book comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

If there is one thing more fun than discovering a new (to oneself) author, it is discovering a new author with a series already well underway. In City of Ink (Minotaur Books, 2018), the third of Elsa Hart’s mystery novels set in early eighteenth-century China during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor and featuring former imperial librarian Li Du and his storytelling friend Hamza, Li has returned to his former home of Beijing.

His intention is to learn more about the events that led to his own exile from the capital years before, the result of guilt by association. But he soon discovers that the imperial library has been closed since his departure, and to make ends meet, he takes a job with his former brother-in-law, in charge of the North Borough Office. When, on the eve of the imperial examinations, a young woman is murdered at a tile factory in the North Borough, Li accompanies the investigator to the scene of the crime. The case appears clear-cut, since the victim turns out to be the wife of the tile-factory owner, and she is found with a man whom everyone assumes to be her lover. Clearly, this is a crime of passion, committed by the jealous husband. The authorities rush to endorse this explanation, since crimes of passion are not punishable under the law and the whole matter can be neatly swept under the rug before the imperial examinations begin.

But no case associated with Li Du is ever what it seems. As he and Hamza chase the real solution through the locked alleys of Beijing and past the city walls into the surrounding territory, Hart’s richly informed, beautifully detailed, and wonderfully complex yet satisfying story plays out against the backdrop of early Qing China, with its rebels, dynasts, foreign visitors, and ordinary folk with conflicting motives—not to mention Li Du’s own troubled past.

Published on May 03, 2019 06:00

April 26, 2019

Lost Worlds

For the last couple of months, I’ve been working with fellow Five Directions Press author and New Books in Fantasy host Gabrielle Mathieu as she revises her latest novel, Girl of Fire, for publication. It’s a historical fantasy set on a planet other than our own—somewhat medieval, somewhat magical, but not directly connected to anything on Earth. In return, she’s been helping me with Song of the Shaman, due out next year.

For the last couple of months, I’ve been working with fellow Five Directions Press author and New Books in Fantasy host Gabrielle Mathieu as she revises her latest novel, Girl of Fire, for publication. It’s a historical fantasy set on a planet other than our own—somewhat medieval, somewhat magical, but not directly connected to anything on Earth. In return, she’s been helping me with Song of the Shaman, due out next year.One question we keep batting back and forth is where the boundary lies between too much and not enough information. But that question is really a subset of world building. How does an author convey the rules and substance of a world outside the reader’s experience? More specifically, how does one convey information without stopping the action cold?

Obviously, authors of science fiction and fantasy have to deal with world building. But so do historical novelists. By definition, a world that existed decades or centuries before we were born lies outside our experience. How do we make it real for ourselves, then communicate that reality to our readers?

We research, of course. We read documents and studies; we search the Internet for images; we visit museums or watch films and TV shows to get a sense of the physical objects associated with the period; we look for diaries and letters and, if we’re lucky and aren’t working on an era too far in the past, talk to people who lived then. We can’t expect to shed our modern perspectives entirely, but we can, and should, do our best to explore the differences between past approaches to life and present ones.

We research, of course. We read documents and studies; we search the Internet for images; we visit museums or watch films and TV shows to get a sense of the physical objects associated with the period; we look for diaries and letters and, if we’re lucky and aren’t working on an era too far in the past, talk to people who lived then. We can’t expect to shed our modern perspectives entirely, but we can, and should, do our best to explore the differences between past approaches to life and present ones.All fine and good. The difficulty lies in the doing. Lengthy descriptions deflect attention from the story, and as a general rule people don’t talk about things they take for granted (known among authors as the “You know, Bob,” problem—as in having a character say something like, “You know, Bob, that girl who grew up in our house—the daughter of Mom and Dad?—she’s our sister”). No, really? Who’d have guessed?

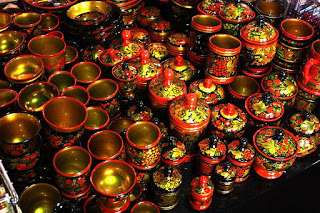

But if people don’t say things that seem self-evident to them, they do interact with their environments pretty much nonstop. And those actions and assumptions reveal a lot about how characters believe their world should work and therefore how they perceive its underlying rules. These assumptions inform even the most basic details of characters’ lives. And detail is the best way to convey them. Let’s take a simple example.

A character picks up a cup and notices it’s empty. He looks around for something to fill it. What will he choose: wine, beer, milk, tea, cider from his own orchard? The choice reveals something personal about this character’s tastes, but also about his circumstances and values—whether he’s wealthy or poor, whether he lives on the land or not, the part of the world he calls home or the possibility of trade or even the time period, since tea and wine and cider weren’t always available everywhere. The drinking vessel, too, tells a tale: a crystal glass conveys a quite different message from a goblet chased with gold or a cup roughly formed from unfired clay.

A character picks up a cup and notices it’s empty. He looks around for something to fill it. What will he choose: wine, beer, milk, tea, cider from his own orchard? The choice reveals something personal about this character’s tastes, but also about his circumstances and values—whether he’s wealthy or poor, whether he lives on the land or not, the part of the world he calls home or the possibility of trade or even the time period, since tea and wine and cider weren’t always available everywhere. The drinking vessel, too, tells a tale: a crystal glass conveys a quite different message from a goblet chased with gold or a cup roughly formed from unfired clay.Perhaps the cup is cracked. The character could try to fix it herself or summon a repair person or, moving up the social ladder, ring the bell to call someone else to summon the repair person. That person may race to respond to the summons, if it comes from a wealthy household known for its generosity, or shrug and dismiss it out of hand. After all, she’s worked for this person before and it didn’t go well.

If she accepts the job, she must travel to the house—hut? castle? apartment? cottage?—by whatever means of transport characterizes that society. She may go quickly or slowly, motivated by urgency or reluctance, respect or disdain. She may believe she has no choice but to obey. She may jump at the chance to prove her skill. She may want to undercut the better-known or more senior artisan in town. Each motive has different consequences and reveals different assumptions about this character’s place in the larger society.

Characters will also have views about how the cup ended up empty or broken, which they can share with other characters or, if they don’t trust those around them or anticipate ridicule, keep to themselves. Careless servants? Mischievous house elves? Thirsty children? The interpretations say a lot without elaboration.

Characters will also have views about how the cup ended up empty or broken, which they can share with other characters or, if they don’t trust those around them or anticipate ridicule, keep to themselves. Careless servants? Mischievous house elves? Thirsty children? The interpretations say a lot without elaboration.That’s just one routine element of life, but there are many. How often have you said, to yourself or someone else, the equivalent of “Oh, it would rain on my special day!” or “Of course all the traffic signals were red. I was running late!” Well, characters can do that too. Some may blame the weather, others their own sins; some call on God, whereas others perform spells or ride winged horses into spiritual realms. Still others favor logic and deride all statements of otherworldly intervention.

The mental explanations your creations provide or the dialogue they exchange reveal how they think: no detailed explanations needed. Ground a setting or an experience or even the weather in a character’s unique view of the world, and you can get a lot of information out in chunks so small and painless that readers won’t even notice them going down.

And when those options fail, you can always fall back on that old chestnut, the “fish out of water.” People inside a family, a group, or a society don’t ask basic questions about how it operates—although you can throw them a curve ball in the plot that will force them to re-examine what they think they know. But those from outside the sub-world—whether they are young and uninformed, elderly and forgetful, or accustomed to operating by different rules—must seek explanations for behavior that puzzles them if they are to succeed at their goals. And the people who have to deal with those newcomers will ask questions too, if only at the level of “why on earth didn’t you” [fill in the blank].

So break it up, make it personal, and above all, keep it relevant to your characters’ concerns of the moment. That’s how you get around the dreaded information dump and bring a lost world to life.

For an example of an author who handles this task particularly well, read Elsa Hart’s mystery series, set in early Qing China and discussed in my latest interview on New Books in Historical Fiction. It went up too late for a discussion in this week’s post, but check back next Friday to find out more.

For an example of an author who handles this task particularly well, read Elsa Hart’s mystery series, set in early Qing China and discussed in my latest interview on New Books in Historical Fiction. It went up too late for a discussion in this week’s post, but check back next Friday to find out more.Images: Khokhloma ware © 2009 Politkaner; Goblet © 2013 Jonathan Cardy; Clay cups © 2017 Sidheeq; Waterford crystal glass © 2008 TR001—all Creative Commons 3.0 or 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

And as I’ve mentioned before, if you have been my friend on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), that will be the main venue for my writing-related posts going forward. I’ve deactivated my Catriona Lesley account, so if you search for it, you will not see my profile. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and @NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Published on April 26, 2019 06:00

April 19, 2019

Good Night, Sweet Prince

I lost a dear friend this week. I’d known him since he was two months old. He was born in Chicago, and he entered my life in August 2001. In that more innocent time before 9/11, when it never occurred to us that anyone could be so evil as to turn a plane full of innocent passengers into a weapon, we thought nothing of having him flown from the Midwest to the East Coast. Sir Percy and I drove to the local airport to collect him. He was in a closed-off area, so we opened his carrier. I can still remember how he walked out, his little legs trembling with anxiety. Even so, he came straight to us, ready to love and to trust a pair of strangers who knelt waiting to welcome him.

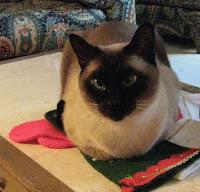

I lost a dear friend this week. I’d known him since he was two months old. He was born in Chicago, and he entered my life in August 2001. In that more innocent time before 9/11, when it never occurred to us that anyone could be so evil as to turn a plane full of innocent passengers into a weapon, we thought nothing of having him flown from the Midwest to the East Coast. Sir Percy and I drove to the local airport to collect him. He was in a closed-off area, so we opened his carrier. I can still remember how he walked out, his little legs trembling with anxiety. Even so, he came straight to us, ready to love and to trust a pair of strangers who knelt waiting to welcome him. Jahan, you see, was a cat. But not just any cat. He was the King of Cats—in his own mind and ours. A Seal Point Siamese with a powerful yowl and an equally strong sense of his own presence in our home and in our hearts. He lived with us for more than seventeen years—until last Saturday, when those same legs trembled so much with muscle loss, the result of kidney disease and a thyroid tumor and, as we discovered close to the end, another tumor in his belly that sucked all the nutrients from his body, including his heart. Throughout those seventeen years, he acted as self-appointed host to our guests, our unswerving companion, our resident acrobat and sometime clown, and the teacher of younger cats who entered our household, temporarily or to live. We will miss him more than he can know.

Jahan, you see, was a cat. But not just any cat. He was the King of Cats—in his own mind and ours. A Seal Point Siamese with a powerful yowl and an equally strong sense of his own presence in our home and in our hearts. He lived with us for more than seventeen years—until last Saturday, when those same legs trembled so much with muscle loss, the result of kidney disease and a thyroid tumor and, as we discovered close to the end, another tumor in his belly that sucked all the nutrients from his body, including his heart. Throughout those seventeen years, he acted as self-appointed host to our guests, our unswerving companion, our resident acrobat and sometime clown, and the teacher of younger cats who entered our household, temporarily or to live. We will miss him more than he can know.There is, of course, a twist that reflects the reality of pet ownership. Despite the glowing rhetoric about crossing Rainbow Bridges and the like, Jahan’s long life didn’t end because of the laws of nature or because God called him home (although his atrial fibrillation might have caused that soon enough). It ended because his family and his wonderfully supportive veterinarians decided that to keep him longer would cause a degree of suffering that was no longer justified by the quality of his life. In four and a half decades of cat ownership, Sir Percy and I have once made that call too soon and once too late, but this time I think we got it right.

So it’s not the old, sick, incapacitated Jahan whose life I wish we could have extended for a few more weeks, days, or months—the one who could no longer walk without staggering and sometimes not even then. That Jahan is, I hope and believe, in a happier place—one where pain and discomfort can no longer trouble him.

No, the Jahan for whom I grieve is that kitten from the carrier who slipped under our covers the first evening and slept with us every night after that, including his last. It’s the adult Jahan who could reach the top of our ten-foot cabinets in two leaps (he's the one on the right), who would not think of jumping on the counter or the table to steal Sir Percy’s bacon but did not hesitate to grab it with an outstretched claw and knock it to the floor, who waited for my interviews to start before yelling at the squirrels outside or announcing his arrival (step by step) as he came up my office stairs, who sat in front of my computer screen every afternoon at 4:30 pm just in case that was the day I would forget to feed him, who tolerated the twice-daily pills and the twice-weekly trips to the vet for fluids so long as he got treats afterward, and who sat on my lap each morning while I tackled the crossword puzzle, gazing at the paper as if he could read the clues. If he were here, I would hug him and cry into his fur, and he would stare at me, not understanding but tolerating my human emotions without judging them.

But he’s not here, and he never will be again. It’s the end of an era, one that began when both he and I were much younger, and in that sense his departure also marks the inexorable passage of time. I have only memories and photographs of him now. So here I include several of those I’ve posted on this blog over the years, as well as one from ten years ago, when he was in his heyday. And as Horatio says to Hamlet, “Good night, sweet prince, and may flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.”

And thank you to all the doctors and staff at our local veterinary hospital, who made his last day as painless as possible.

Images © 2008-18 C. P. Lesley.

As I mentioned last week, if you have been my friend on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), that will be the main venue for my writing-related posts going forward. I’ve deactivated my Catriona Lesley account, so if you search for it, you will not see my profile. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and @NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Published on April 19, 2019 06:00

April 12, 2019

Bookshelf, April 2019

It’s been four months since my last bookshelf post, and I’ve made it through most of the November and December listings, with two exceptions. I’m still looking forward to Ann Weisbarger’s The Glovemaker, which is next in my interview list after Elsa Hart’s City of Ink, and Adrienne Celt’s Invitation to a Bonfire, which we rescheduled to late June to follow the book’s release in paperback.

Meanwhile, a whole new group of titles has appeared, meaning that I have little time to read anything but books for interviews (oral and written), books for blog posts, and books for myself and other Five Directions Press writers. But don’t think for a minute that I’m complaining: having major presses send historical novels unasked is a lovely place to be! So, here’s the current lineup, with at least three more August titles waiting in the wings for a later post.

Meanwhile, a whole new group of titles has appeared, meaning that I have little time to read anything but books for interviews (oral and written), books for blog posts, and books for myself and other Five Directions Press writers. But don’t think for a minute that I’m complaining: having major presses send historical novels unasked is a lovely place to be! So, here’s the current lineup, with at least three more August titles waiting in the wings for a later post.

The deluge of World War II books continues. Three have landed on my desk recently, two of them scheduled for release in May and exploring the impact of the war on countries in the Pacific Front. Right now, I’m reading Jing-Jing Lee’s harrowing debut novel,

How We Disappeared

, set in Singapore, where a young woman is wrenched away from her family and forced into service as a “comfort woman” in 1942. Like Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

, much of which takes place in Shanghai in 1939, How We Disappeared contrasts its wartime story with a more contemporary perspective—here a twelve-year-old boy watching his grandmother die in 2000; in Song of the Jade Lily, a young woman visiting her grandparents in 2016. I’ll be writing more about them together on the blog in early May.

The deluge of World War II books continues. Three have landed on my desk recently, two of them scheduled for release in May and exploring the impact of the war on countries in the Pacific Front. Right now, I’m reading Jing-Jing Lee’s harrowing debut novel,

How We Disappeared

, set in Singapore, where a young woman is wrenched away from her family and forced into service as a “comfort woman” in 1942. Like Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

, much of which takes place in Shanghai in 1939, How We Disappeared contrasts its wartime story with a more contemporary perspective—here a twelve-year-old boy watching his grandmother die in 2000; in Song of the Jade Lily, a young woman visiting her grandparents in 2016. I’ll be writing more about them together on the blog in early May.

A third May release also employs a dual-time perspective and addresses one of the long-term effects of the war: the stationing of US troops in Japan, here in 1957. A love affair between a Japanese teenager and an American sailor ends in an unwanted pregnancy, and the consequences ripple down to the present. I’ll be talking with Ana Johns about

The Woman in the White Kimono

for New Books in Historical Fiction at the end of May.

A third May release also employs a dual-time perspective and addresses one of the long-term effects of the war: the stationing of US troops in Japan, here in 1957. A love affair between a Japanese teenager and an American sailor ends in an unwanted pregnancy, and the consequences ripple down to the present. I’ll be talking with Ana Johns about

The Woman in the White Kimono

for New Books in Historical Fiction at the end of May.

But not every book that crosses my desk is set in World War II. One of my great delights this year has been the discovery of Elsa Hart’s mystery series set in early eighteenth-century China, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Starting with Jade Dragon Mountain and continuing with The White Mirror and last year’s

City of Ink

, the series follows the adventures of a former imperial librarian named Li Du and his friend Hamza, a storyteller who travels the Silk Road. In City of Ink, the topic of my next interview, Li Du has returned to Beijing, looking for answers to the incident that led to his own exile from the capital five years before. When the wife of a tile-factory owner is found murdered alongside a man assumed to be her lover, Li Du becomes involved in an official capacity, charged with determining whether this really is, as it appears to be, a crime of passion. Hart does a wonderful job of crafting richly detailed, deeply satisfying solutions to her mysteries, blending political, historical, religious, and cultural explanations into a seamless whole. I can’t wait to talk to her, never mind for the arrival of the next book in her series.

But not every book that crosses my desk is set in World War II. One of my great delights this year has been the discovery of Elsa Hart’s mystery series set in early eighteenth-century China, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Starting with Jade Dragon Mountain and continuing with The White Mirror and last year’s

City of Ink

, the series follows the adventures of a former imperial librarian named Li Du and his friend Hamza, a storyteller who travels the Silk Road. In City of Ink, the topic of my next interview, Li Du has returned to Beijing, looking for answers to the incident that led to his own exile from the capital five years before. When the wife of a tile-factory owner is found murdered alongside a man assumed to be her lover, Li Du becomes involved in an official capacity, charged with determining whether this really is, as it appears to be, a crime of passion. Hart does a wonderful job of crafting richly detailed, deeply satisfying solutions to her mysteries, blending political, historical, religious, and cultural explanations into a seamless whole. I can’t wait to talk to her, never mind for the arrival of the next book in her series.

Another pleasant surprise is Lauren Willig’s

The Summer Country

, set in mid-nineteenth-century Barbados. I’ve been a fan of Willig’s writing ever since her first book, The Secret History of the Pink Carnation, but due to other commitments, including those listed above, I’ve rather fallen by the wayside as she’s finished, altogether, twelve Pink Carnation novels, The Ashford Affair, The English Wife, and two co-written books. I’m very much looking forward to catching up on her work before interviewing her in mid-July. This latest novel follows Emily Dawson, a vicar’s daughter and poor relation to a well-off merchant family, as she inherits a sugar plantation that, when she reaches the island, she discovers has been burned and abandoned. As Emily struggles to learn what happened and why her grandfather never told anyone in his family about the plantation’s existence, she stumbles into a thicket of secrets that, as the back cover puts it “challenge everything she thought she knew about her family, their legacy, and herself.”

Another pleasant surprise is Lauren Willig’s

The Summer Country

, set in mid-nineteenth-century Barbados. I’ve been a fan of Willig’s writing ever since her first book, The Secret History of the Pink Carnation, but due to other commitments, including those listed above, I’ve rather fallen by the wayside as she’s finished, altogether, twelve Pink Carnation novels, The Ashford Affair, The English Wife, and two co-written books. I’m very much looking forward to catching up on her work before interviewing her in mid-July. This latest novel follows Emily Dawson, a vicar’s daughter and poor relation to a well-off merchant family, as she inherits a sugar plantation that, when she reaches the island, she discovers has been burned and abandoned. As Emily struggles to learn what happened and why her grandfather never told anyone in his family about the plantation’s existence, she stumbles into a thicket of secrets that, as the back cover puts it “challenge everything she thought she knew about her family, their legacy, and herself.”

Last but not least, although it’s due for release only in late August and should really be listed with those books, is Gill Paul’s

The Lost Daughter

, about the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, focusing on the last days of Grand Duchess Maria, the third daughter of the tsar. A follow-up to 2016’s The Secret Wife, about Maria’s older sister Tatiana, The Lost Daughter is another dual-time story in which a woman sets out to discover (in 1973), the meaning behind her father’s deathbed confession, “I didn’t want to kill her.” Although we now know, thanks to DNA evidence, that in fact no member of the tsar’s immediate family escaped the slaughter in Ekaterinburg, including Maria and the better-known Anastasia, I’m still drawn to novels set in Russia at any time—for obvious reasons—so I will definitely cover this one, although probably in a written Q&A, given that my interview schedule is already packed into the fall.

Last but not least, although it’s due for release only in late August and should really be listed with those books, is Gill Paul’s

The Lost Daughter

, about the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, focusing on the last days of Grand Duchess Maria, the third daughter of the tsar. A follow-up to 2016’s The Secret Wife, about Maria’s older sister Tatiana, The Lost Daughter is another dual-time story in which a woman sets out to discover (in 1973), the meaning behind her father’s deathbed confession, “I didn’t want to kill her.” Although we now know, thanks to DNA evidence, that in fact no member of the tsar’s immediate family escaped the slaughter in Ekaterinburg, including Maria and the better-known Anastasia, I’m still drawn to novels set in Russia at any time—for obvious reasons—so I will definitely cover this one, although probably in a written Q&A, given that my interview schedule is already packed into the fall.

On another note, if you have been connected with me on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), now would be a good time, as I am making some changes there, and that will be the main venue for any writing-related posts. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Meanwhile, a whole new group of titles has appeared, meaning that I have little time to read anything but books for interviews (oral and written), books for blog posts, and books for myself and other Five Directions Press writers. But don’t think for a minute that I’m complaining: having major presses send historical novels unasked is a lovely place to be! So, here’s the current lineup, with at least three more August titles waiting in the wings for a later post.

Meanwhile, a whole new group of titles has appeared, meaning that I have little time to read anything but books for interviews (oral and written), books for blog posts, and books for myself and other Five Directions Press writers. But don’t think for a minute that I’m complaining: having major presses send historical novels unasked is a lovely place to be! So, here’s the current lineup, with at least three more August titles waiting in the wings for a later post. The deluge of World War II books continues. Three have landed on my desk recently, two of them scheduled for release in May and exploring the impact of the war on countries in the Pacific Front. Right now, I’m reading Jing-Jing Lee’s harrowing debut novel,

How We Disappeared

, set in Singapore, where a young woman is wrenched away from her family and forced into service as a “comfort woman” in 1942. Like Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

, much of which takes place in Shanghai in 1939, How We Disappeared contrasts its wartime story with a more contemporary perspective—here a twelve-year-old boy watching his grandmother die in 2000; in Song of the Jade Lily, a young woman visiting her grandparents in 2016. I’ll be writing more about them together on the blog in early May.

The deluge of World War II books continues. Three have landed on my desk recently, two of them scheduled for release in May and exploring the impact of the war on countries in the Pacific Front. Right now, I’m reading Jing-Jing Lee’s harrowing debut novel,

How We Disappeared

, set in Singapore, where a young woman is wrenched away from her family and forced into service as a “comfort woman” in 1942. Like Kirsty Manning’s

The Song of the Jade Lily

, much of which takes place in Shanghai in 1939, How We Disappeared contrasts its wartime story with a more contemporary perspective—here a twelve-year-old boy watching his grandmother die in 2000; in Song of the Jade Lily, a young woman visiting her grandparents in 2016. I’ll be writing more about them together on the blog in early May. A third May release also employs a dual-time perspective and addresses one of the long-term effects of the war: the stationing of US troops in Japan, here in 1957. A love affair between a Japanese teenager and an American sailor ends in an unwanted pregnancy, and the consequences ripple down to the present. I’ll be talking with Ana Johns about

The Woman in the White Kimono

for New Books in Historical Fiction at the end of May.

A third May release also employs a dual-time perspective and addresses one of the long-term effects of the war: the stationing of US troops in Japan, here in 1957. A love affair between a Japanese teenager and an American sailor ends in an unwanted pregnancy, and the consequences ripple down to the present. I’ll be talking with Ana Johns about

The Woman in the White Kimono

for New Books in Historical Fiction at the end of May. But not every book that crosses my desk is set in World War II. One of my great delights this year has been the discovery of Elsa Hart’s mystery series set in early eighteenth-century China, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Starting with Jade Dragon Mountain and continuing with The White Mirror and last year’s

City of Ink

, the series follows the adventures of a former imperial librarian named Li Du and his friend Hamza, a storyteller who travels the Silk Road. In City of Ink, the topic of my next interview, Li Du has returned to Beijing, looking for answers to the incident that led to his own exile from the capital five years before. When the wife of a tile-factory owner is found murdered alongside a man assumed to be her lover, Li Du becomes involved in an official capacity, charged with determining whether this really is, as it appears to be, a crime of passion. Hart does a wonderful job of crafting richly detailed, deeply satisfying solutions to her mysteries, blending political, historical, religious, and cultural explanations into a seamless whole. I can’t wait to talk to her, never mind for the arrival of the next book in her series.

But not every book that crosses my desk is set in World War II. One of my great delights this year has been the discovery of Elsa Hart’s mystery series set in early eighteenth-century China, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Starting with Jade Dragon Mountain and continuing with The White Mirror and last year’s

City of Ink

, the series follows the adventures of a former imperial librarian named Li Du and his friend Hamza, a storyteller who travels the Silk Road. In City of Ink, the topic of my next interview, Li Du has returned to Beijing, looking for answers to the incident that led to his own exile from the capital five years before. When the wife of a tile-factory owner is found murdered alongside a man assumed to be her lover, Li Du becomes involved in an official capacity, charged with determining whether this really is, as it appears to be, a crime of passion. Hart does a wonderful job of crafting richly detailed, deeply satisfying solutions to her mysteries, blending political, historical, religious, and cultural explanations into a seamless whole. I can’t wait to talk to her, never mind for the arrival of the next book in her series. Another pleasant surprise is Lauren Willig’s

The Summer Country

, set in mid-nineteenth-century Barbados. I’ve been a fan of Willig’s writing ever since her first book, The Secret History of the Pink Carnation, but due to other commitments, including those listed above, I’ve rather fallen by the wayside as she’s finished, altogether, twelve Pink Carnation novels, The Ashford Affair, The English Wife, and two co-written books. I’m very much looking forward to catching up on her work before interviewing her in mid-July. This latest novel follows Emily Dawson, a vicar’s daughter and poor relation to a well-off merchant family, as she inherits a sugar plantation that, when she reaches the island, she discovers has been burned and abandoned. As Emily struggles to learn what happened and why her grandfather never told anyone in his family about the plantation’s existence, she stumbles into a thicket of secrets that, as the back cover puts it “challenge everything she thought she knew about her family, their legacy, and herself.”

Another pleasant surprise is Lauren Willig’s

The Summer Country

, set in mid-nineteenth-century Barbados. I’ve been a fan of Willig’s writing ever since her first book, The Secret History of the Pink Carnation, but due to other commitments, including those listed above, I’ve rather fallen by the wayside as she’s finished, altogether, twelve Pink Carnation novels, The Ashford Affair, The English Wife, and two co-written books. I’m very much looking forward to catching up on her work before interviewing her in mid-July. This latest novel follows Emily Dawson, a vicar’s daughter and poor relation to a well-off merchant family, as she inherits a sugar plantation that, when she reaches the island, she discovers has been burned and abandoned. As Emily struggles to learn what happened and why her grandfather never told anyone in his family about the plantation’s existence, she stumbles into a thicket of secrets that, as the back cover puts it “challenge everything she thought she knew about her family, their legacy, and herself.” Last but not least, although it’s due for release only in late August and should really be listed with those books, is Gill Paul’s

The Lost Daughter

, about the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, focusing on the last days of Grand Duchess Maria, the third daughter of the tsar. A follow-up to 2016’s The Secret Wife, about Maria’s older sister Tatiana, The Lost Daughter is another dual-time story in which a woman sets out to discover (in 1973), the meaning behind her father’s deathbed confession, “I didn’t want to kill her.” Although we now know, thanks to DNA evidence, that in fact no member of the tsar’s immediate family escaped the slaughter in Ekaterinburg, including Maria and the better-known Anastasia, I’m still drawn to novels set in Russia at any time—for obvious reasons—so I will definitely cover this one, although probably in a written Q&A, given that my interview schedule is already packed into the fall.

Last but not least, although it’s due for release only in late August and should really be listed with those books, is Gill Paul’s

The Lost Daughter

, about the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, focusing on the last days of Grand Duchess Maria, the third daughter of the tsar. A follow-up to 2016’s The Secret Wife, about Maria’s older sister Tatiana, The Lost Daughter is another dual-time story in which a woman sets out to discover (in 1973), the meaning behind her father’s deathbed confession, “I didn’t want to kill her.” Although we now know, thanks to DNA evidence, that in fact no member of the tsar’s immediate family escaped the slaughter in Ekaterinburg, including Maria and the better-known Anastasia, I’m still drawn to novels set in Russia at any time—for obvious reasons—so I will definitely cover this one, although probably in a written Q&A, given that my interview schedule is already packed into the fall.On another note, if you have been connected with me on Facebook but have not liked my author page (@C. P. Lesley), now would be a good time, as I am making some changes there, and that will be the main venue for any writing-related posts. Other pages to follow are @Five Directions Press and NB Historical Fiction. Twitter links remain the same.

Published on April 12, 2019 07:25

April 5, 2019

Changing Times