C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 21

May 22, 2020

Joining the 2020s

I last upgraded my computer in January 2010. It’s possible to nurse a Mac computer that long, even while using it every day, despite Apple’s ruthless jettisoning of hardware and software features that work perfectly well but don’t encourage people to shell out large sums on a schedule that suits the company’s bottom line.

I last upgraded my computer in January 2010. It’s possible to nurse a Mac computer that long, even while using it every day, despite Apple’s ruthless jettisoning of hardware and software features that work perfectly well but don’t encourage people to shell out large sums on a schedule that suits the company’s bottom line.Sir Percy’s iMac is even older, and although I haven’t started up the 2005 predecessor of today’s computer since his hard drive died and was replaced with an unformatted disk that required intensive forays into the wilds of target disk mode, software upgrades, and old manuals, the predecessor came through then at the venerable computer age of twelve.

I’ve been putting off the upgrade for several reasons. The hardware costs double what I’d pay for a cheap PC, but it lasts three to four times as long, so that seems like a fair trade even if gathering the necessary sum requires effort. The real deterrent has been the software, some of which has undergone “improvements” that in fact do not improve the user experience but degrade it. In particular, the move of several essential programs to an online subscription model led me not even to consider buying a new machine. What can I say? I’m a Scotswoman. The thought of being unable to access my own files unless I cough up $X a month feels like highway robbery to me.

All strong reasons to wait. Nevertheless, this month I took the plunge. I do, after all, depend on my computer not only for my job but for my hobby of choice (writing fiction). And as much as I still love my existing iMac, it has started to show the effects of age. Startup takes so long that I turn the machine on before I even eat breakfast, and the one time I needed help from tech support we had to give up midway on the restart in Safe Mode. The hard drive, which once seemed enormous, has become cramped enough that I routinely copy files to a backup disk and delete them from the main machine. And software upgrades, including security patches, lead to constant excitement as to whether the system will reboot. Features in various programs that appear either vital or useful come with disclaimers that they won’t run on my setup.

So when I got a better than expected royalty check for my nonfiction book, I decided it was time. If all goes well, a brand-new iMac will arrive at my house around the time this post goes up. Then the real fun begins. What can I transfer seamlessly? What must I jettison or replace? Will programs that do run on the new machine be less buggy there or more? Good thing we have a three-day weekend coming up.

So far, she typed with fingers crossed, the old computer does still boot, despite occasionally threatening to give me a heart attack because I’ve hit the power switch four times without result. So long as it does, I can shift the newer programs over and still (I hope) access the old ones in a pinch. But I remember the last time I did this, ten years ago, and I know from experience to expect a wild ride for a while. So wish me luck as I make the transition!

Image purchased by subscription from Clipart.com, no. 110337376.

Published on May 22, 2020 06:00

May 15, 2020

The Three Ms of Writing Historical Fiction

Most of the time, I write my own blog posts or share them with authors via questions and answers. But once in a while, I get the opportunity to feature someone else’s views on historical fiction and the writing of it. Today I have a guest post by Ben Wyckoff Shore, whose novel

Terribilita

just came out with Cinder Block Publishing.

Most of the time, I write my own blog posts or share them with authors via questions and answers. But once in a while, I get the opportunity to feature someone else’s views on historical fiction and the writing of it. Today I have a guest post by Ben Wyckoff Shore, whose novel

Terribilita

just came out with Cinder Block Publishing. Ben raises a question of interest to all historical novelists: how do we recreate not only the material and political circumstances that characterize a particular segment of the past but the psychological assumptions about how the world works that determine how our characters react to those circumstances. Emotions don’t change over the millennia, but what provokes them definitely does. So here I turn over the post to Ben, with thanks for his suggestions about three ways to access what he refers to as the “zeitgeist of the past.”

Three Ms of Historical Fiction That Will Help You Nail the Zeitgeist of the Past

Ben Wyckoff Shore

A major challenge of writing historical fiction is getting the zeitgeist right. Getting the zeitgeist right is one of the most powerful things you can do as a writer to set your book apart and goes far beyond placating the fact-checking history buffs (love you folks).

By zeitgeist, I don’t just mean atmosphere: I also mean the outlook and perspective of those who lived a hundred, two hundred, or even five hundred years ago. History may be written by the victors, as the maxim goes, but there are countless other historical perspectives to present. Understanding and conveying these will add depth to your characters, giving you the tools to portray history from their varied, complex perspectives and worldviews. It will also inspire your characters’ visceral motives, their challenges and their fears—enabling you to craft a story that will truly transport your readers.

To dig up these treasured perspectives we must get as close to the horse’s mouth as possible. During the process of writing and researching my novel, Terribilita, set in nineteenth-century Italy, I found that the very best way to burrow back in time is to tap into primary resources by delving into what I call the three Ms: Memoirs, Museums, and Media.

Memoirs

Most memoirs are fantastic primary sources that provide an extraordinary amount of detail into the day to day of your time period. However, to get that illusory “historical perspective,” we must really focus on memoir selection, as not all memoirs are created equal. Some of the best memoirs are not from the prominent and the powerful of the era, and in fact, some of the less famous accounts from the era will be more aligned with the everyman perspective.

In preparation for writing Terribilita and specifically writing a mercenary character, I read a memoir by a British army officer who was embedded with a renegade portion of the Ottoman Army called the Bashi-Bazouks. Twelve Months with the Bashi-Bazouks by Edward Money (1857) gave me a tremendous amount of insight into what motivated these fighting men, the honor codes they obeyed, and their exotic styles of combat. The author Edward Money is not a household name, and his book won’t show up on any bestseller lists, but this read allowed me to crawl into the skull of a soldier of fortune.

The best way I’ve found to find these insider memoirs is through Google Advanced Book Search. This free tool allows you to search by subject using keywords and, more importantly, publish date, which will yield authors that were alive and kicking during your chosen era. By the way, Bashi-Bazouk is Turkish for “crazy-head.”

Museums

While my wife and I were in Italy last summer for a friend’s wedding, I hijacked our vacation and dragged her to the island of Caprera. This raw, rocky island off Sardinia is where Giuseppe Garibaldi lived out his final years. Garibaldi was the Risorgimento general who helped unite the many Kingdoms of Italy into one nation. He is a major influence for the characters and the time period of Terribilita. By walking his island and through his house, now a beautiful museum, I was able to get a better sense of the man who led a movement, which created a country. The museum holds his clothes, his weapons, his letters, and his grave. Take any opportunity to get up close and tactile with history: it will make your composition all the more vivid. Another word of advice with regard to museum mongering: talk to the people who work there. I’ve found they know a whole lot more than what is shown in the exhibits. Museums may be closed for the moment, but they will be back.

Media

Finding contemporaneous media is an excellent way to tap into your chosen epoch. I found a July 15, 1859, edition of the New York Herald, which reported on the Battle of Solferino (critical to the story of Terribilita) from the varied perspectives of each of the warring nations. Napoleon III is hailed as a genius, a scoundrel, and a lucky S.O.B. in different sections of the same publication. This newspaper also featured a map of the battlefield and the troop movements. Thanks, eBay. Although I was set back $35—a large markup from the original price of 2 cents—I now have a memento to frame and hang on my wall as a fond memory.

It may well be true that the victor’s truth usually becomes the lasting version of history most of us tell and retell. But there are other versions out there waiting for writers to bring back to life. We just need to know where to look.

Ben Wyckoff Shore is the author of the historical fiction novel Terribilita, his first published work. Ben enjoys reading and writing about very flawed, very human characters. He likes all sorts of dogs but especially underdogs. He has a B.A. from Tufts University and a Masters from Dartmouth College, and he lives in New York with his wife, Mariana. Find out more about him at https://www.cinderblockpublishing.com.

Published on May 15, 2020 07:27

May 8, 2020

Alone at Longbourn

I think most of us know that Jane Austen in general and Pride and Prejudice in particular have a few fans. And that some of those fans write novels about Austen’s characters or set in Austen’s world. Elizabeth (Lizzie) Bennet—everyone’s favorite, as Janice Hadlow notes in my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview about her just-published novel,

The Other Bennet Sister

—has entire series centered on her as well as individual novels about her married life with Mr. Darcy and his younger sister, Georgiana.

I think most of us know that Jane Austen in general and Pride and Prejudice in particular have a few fans. And that some of those fans write novels about Austen’s characters or set in Austen’s world. Elizabeth (Lizzie) Bennet—everyone’s favorite, as Janice Hadlow notes in my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview about her just-published novel,

The Other Bennet Sister

—has entire series centered on her as well as individual novels about her married life with Mr. Darcy and his younger sister, Georgiana. But Lizzie is easy to love. She’s attractive, witty, graceful, and sparkling. She dances well, and although less technically proficient at the piano than others, including her earnest sister Mary, she plays with such spirit that no one notices her flaws. Like her creator, Lizzie has a gift for skewering the smug with a well-turned phrase. She seldom finds herself at a loss in any situation. No doubt even she sometimes suffers from embarrassment or makes an error, but most of the time she has the enviable ability to do and say the right thing.

Not so Mary—characterized by Austen herself as awkward, plain, and pompous. Bookish in a time when reading was not a quality much valued in young women, serious and rather literal-minded, Mary doesn’t have a place in her family or in the social world the Bennets occupy. She appears only occasionally in Pride and Prejudice, always under circumstances that disadvantage her. Again quoting Hadlow, Austen doesn’t much like Mary, and it shows.

It seems natural to wonder what life looks like through this under-valued character’s eyes and imagine what might happen to her in later years. But doing so convincingly is a more difficult proposition. This is where Hadlow excels: the years that went into this obvious labor of love produce a richly textured, wholly believable, and sympathetic Mary whose winding emotional path at last brings her into contact with the perfect person for her. It would be churlish to reveal more about who that is and how they meet, but I will say that Mary’s story develops within a series of contrasting futures extrapolated from the original novel. There are some intriguing parallels between this book and Pamela Mingle’s The Pursuit of Mary Bennet (2013), but many more differences. If you liked that earlier novel, I’m pretty sure you will like this one too.

Moreover, in recasting and extending Austen’s well-known novel, Hadlow ends up affirming a point made by Maya Rodale in another recent interview about romance novels more generally: that happy endings need not be restricted to the beautiful, the rich, the witty, or the titled. Even the Mary Bennets of the world deserve to find someone who loves and appreciates them. And that’s an encouraging thought, especially in a time when so many of us can hardly get together with our nearest and dearest, never mind search the world for a long-time partner.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction:

It is well known that the novels of Jane Austen (1775–1817), which enjoyed at best a modest success during her lifetime, have become ever more popular in the last fifty years or so. They support a small industry of remakes, spinoffs, and retellings. As Janice Hadlow notes while discussing The Other Bennet Sister (Henry Holt, 2020), one reason for that interest lies with Austen herself. A genius at characterization, Austen drops tiny pearls of insight into one secondary character after another throughout her novels, and these seeds, when properly nurtured, can develop in unexpected ways.

The Other Bennet Sister focuses on the life of the middle sister in Pride and Prejudice. Stuck between an older pair—beautiful, gentle Jane and pretty, sprightly Lizzie—and a younger duo whose good looks and sheer love of life compensate for a certain lack of decorum, Mary is bookish, awkward, and plain. In a family where the daughters’ only acceptable future requires them to marry well without the plump dowries that would make them attractive to men of their own gentry class, Mary’s traits doom her (at least in her mother’s eyes) to an unhappy and lonely spinsterhood. Even her scholarly father underestimates Mary, because she lacks the wit and self-confidence that so distinguish Lizzie, his favorite.

Hadlow has given deep thought to what it would mean to grow up as Mary—what she wants, how she feels, which twists of fate and family turn her into the character we meet so briefly in Austen’s novel. But then The Other Bennet Sister goes beyond Pride and Prejudice to imagine how the Marys of the world might find happiness, even in the early nineteenth century. It is a captivating and heartening story, and you need not be an Austen fan to appreciate the journey.

Image: Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, as illustrated by Hugh Thomson (1894). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on May 08, 2020 06:00

May 1, 2020

Interview with Michelle Cox

Back in 2016, I interviewed Michelle Cox for New Books in Historical Fiction. At that point, she already had two books in her Henrietta and Inspector Howard mystery series, set in 1930s Chicago: A Girl Like You and A Ring of Truth. You can find out more about those books by clicking on the interview link above. Today, we’re discussing the three later novels in the series, especially

A Child Lost

, released just this week.

Back in 2016, I interviewed Michelle Cox for New Books in Historical Fiction. At that point, she already had two books in her Henrietta and Inspector Howard mystery series, set in 1930s Chicago: A Girl Like You and A Ring of Truth. You can find out more about those books by clicking on the interview link above. Today, we’re discussing the three later novels in the series, especially

A Child Lost

, released just this week.This is your fifth of your detective novels featuring Henrietta von Harmon and Clive Howard. Could you give us a brief overview of Henrietta and Clive, how they got together, and where they are at the beginning of book 4, A Veil Removed—which came out last year?

Sure! Henrietta and Clive are very much from opposite sides of the tracks, as it were. Henrietta is from an impoverished family living in the grip of the Great Depression in Chicago. Her father has killed himself, leaving a chronically depressed wife and eight children behind. As the oldest child, Henrietta is always out working, trying to make money any way she can. Against her better judgment, she takes a job as a taxi-dancer at a dance hall. When her boss, Mama Leone, turns up dead, Inspector Clive Howard arrives on the scene to investigate. He offers her a job going under cover for him at a Burlesque Club, which she accepts, and from there, many adventures, both mysterious and romantic, begin.

In the end, Clive ends up proposing to Henrietta, and she accepts, despite the fact that he is many years her senior. What she doesn’t realize until the next book, however, is that Clive is not just a city detective, but he is also the heir to the fabulous Howard fortune and estate in Winnetka. This causes yet another layer of friction between the two, as Henrietta feels oddly betrayed by this omission.

It’s obviously something they eventually resolve, however, because at the beginning of Book 4, A Veil Removed, Henrietta and Clive, newly married, abruptly end their honeymoon in England to attend the funeral of Clive’s father, Alcott Howard. Alcott has supposedly died as a result of a freak accident, but Clive suspects something more sinister …

Much of A Veil Removed revolves around the death of Clive’s father, Alcott. Without giving away spoilers, what can you tell us about that situation?

Much of A Veil Removed revolves around the death of Clive’s father, Alcott. Without giving away spoilers, what can you tell us about that situation? While cleaning out his father’s study, Clive discovers several damaging letters that point to him being the potential victim of blackmail, furthering Clive’s suspicion that his father’s death was not an accident. His mother refuses to accept this theory and begins to conclude that Clive is mentally deranged from grief. Clive manages to convince Henrietta, however, so the two then begin a clandestine investigation, two of their main suspects being Bennett, Alcott’s right-hand man at his firm, and Carter, Alcott’s personal valet. Things quickly become more dangerous than either Clive or Henrietta first realized.

Another important thread in book 4, which continues into A Child Lost—the fifth book—has to do with Henrietta’s younger sister, Elsie. At the beginning of A Veil Removed, she is not—as we would say these days—in a good place. Why, and how does Henrietta help her resolve it?

At the beginning of A Veil Removed, Elsie finds herself the victim of a foiled elopement with the rogue Lt. Harrison Barnes-Smith, who has cruelly tricked and seduced her. Henrietta, with the help of Clive’s sister, Julia, thwarted the elopement, and now attempts to save Elsie from not only her own depression but from her wicked grandfather’s attempt to marry her off to the highest bidder. Their idea is to enroll Elsie at Mundelein College—a new, all-women’s Catholic school in the city.

As we move into A Child Lost, Elsie is still a student at Mundelein and toying with the idea of taking vows as a nun. Why is that?

Elsie toys with being a nun because she sees this as her only way to be free from her grandfather’s schemes to marry her off. She longs to be able to study and to teach the poor, which she knows she won’t be able to do if she is the wife of some wealthy North Shore tycoon. Nor does she think she will be “left alone” to her own devices.

But her encounter with Gunther and Anna undercuts that goal. Who is Gunther, and what do we need to know about him and Anna to understand this fifth book?

Gunther is a German immigrant working as the custodian at Mundelein. He befriends the shy Elsie before the other girls arrive for the start of the term and encourages her to read and think for herself. A friendship begins between them, which borders on a romance until Elsie finds and reads Gunther’s journal, which mentions, many times, a mysterious woman named Anna.

And where are Clive and Henrietta in A Child Lost?

For a reason I won’t mention, Henrietta is quite depressed at the beginning of A Child Lost, and Clive, desperate to cheer her up, begs a colleague at the Winnetka police for a case that he and Henrietta can work on together as a fledgling detective team.

The case given to them is the investigation of a spiritualist who is operating in an abandoned school house on the edge of town and who is accused of robbing people of their valuables. Meanwhile, Elsie begs Henrietta to help her and Gunther find a missing woman who is connected to the Anna mentioned above, a search which leads them to Dunning, an infamous, real-life asylum in Chicago.

Are you working on Henrietta and Inspector Howard, no. 6?

Well, I have it outlined, but I haven’t started actually writing it. I’m taking a little break from the series to write not one, but two, stand-alone novels, separate from the series—still in 1930s Chicago, but not based on any of the series characters. After they’re finished, I would love to jump back into the series because I really miss spending my days with Henrietta and Clive!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Michelle Cox is the author of the multiple award-winning Henrietta and Inspector Howard series as well as “Novel Notes of Local Lore,” a weekly blog dedicated to Chicago’s forgotten residents. She suspects she may have once lived in the 1930s and, having yet to discover a handy time machine lying around, has resorted to writing about the era as a way of getting herself back there. Find out more about her and sign up for her newsletter at http://www.michellecoxauthor.com.

Published on May 01, 2020 06:00

April 24, 2020

Journey to Sicily

The Five Directions Press motto is “Literary Journeys along Paths Less Traveled.” In this time of stay-at-home orders, long-distance learning, and quarantines, a literary journey is the only kind most of us can hope to undertake.

The Five Directions Press motto is “Literary Journeys along Paths Less Traveled.” In this time of stay-at-home orders, long-distance learning, and quarantines, a literary journey is the only kind most of us can hope to undertake.But even in normal times, books open a window onto worlds we cannot reach by other means: alien planets, magical lands that never existed, the past of every country on earth. Through books we can travel to Jonathan Swift’s Lilliput, Louisa May Alcott’s New England, the French or Russian revolutions, Arthur C. Clarke’s future.

So today I offer a literary journey to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. It’s 1799, and Ignazio Florio awakens to an earthquake in progress: “The earthquake is a hiss that starts in the sea and wedges itself into the night. It swells, grows, then becomes a roar that tears through the silence.”

The members of Ignazio’s family survive, although their house is badly damaged. He and his brother Paolo decide to move to Palermo and establish a spice business. A journey across the sea in a small boat, and the deed is done. They reach the city that will shelter them through competition and disease, war and change, for generations.

And why spices? I’ll let Stefania Auci, author of The Florios of Sicily —an international bestseller beautifully translated by Katherine Gregor and available in English from HarperVia as of this week—answer that question.

Cinnamon, pepper, cumin, aniseed, coriander, saffron, sumac, cassia …

No, spices aren’t just for cooking. They’re medicines, they’re cosmetics, they’re poisons and memories of faraway lands few people have seen.

Before reaching a sales counter, a cinnamon stick or a ginger root has to go through dozens of hands, travel on the back of a mule or a camel in long caravans, cross the ocean, and reach European ports.

So the spices themselves are on a journey, a fragrant and evocative voyage from their home in the East Indies to their eventual destination, where they convey a sensory aura of distant places to those who encounter them.

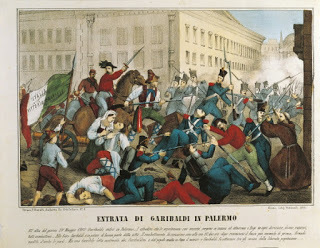

The Florios start with spices, but they don’t end with them. Each of the book’s seven parts charts one stage in their developing enterprise: Spices, Silk, Bark, Sulfur, Lace, Tuna, Sand. The whole becomes a family saga, as Paolo and Ignazio yield the stage to their children and grandchildren. Meanwhile, the world around them is changing as well. Napoleon seeks to conquer Europe. Giuseppe Garibaldi aims to unify the disparate Italian states into a single kingdom, a goal that requires him to subdue Sicily and Naples.

Amid political, economic, and personal turmoil, the Florios press on. So while we’re all locked away at home, take a literary journey to nineteenth-century Sicily. You may find that life looks a whole lot brighter when you’re done.

Image: Giuseppe Garibaldi Entering Palermo (1860), public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on April 24, 2020 06:00

April 17, 2020

Discovering Agnes Pelton

Over the course of eight years, I’ve been very fortunate in—and grateful to—the guests who agree to talk about their new novels during my podcast interviews. But some authors stand out, and Mari Coates, whom I talked to a couple of weeks ago and whose interview went up on Monday, is one of those.

Over the course of eight years, I’ve been very fortunate in—and grateful to—the guests who agree to talk about their new novels during my podcast interviews. But some authors stand out, and Mari Coates, whom I talked to a couple of weeks ago and whose interview went up on Monday, is one of those. While investigating her website in preparation for writing up potential questions, I discovered that her family had a long-time friendship with the subject of her biographical novel, The Pelton Papers . How that relationship came about became the basis of a fascinating and informative conversation.

Now I have to confess: before reading Mari Coates’ book, I had never heard of the painter Agnes Pelton. I immediately looked her up and discovered an extraordinary and beautiful body of work, as well as a touring exhibit currently off-limits to the public at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (thank you, coronavirus). But you can see the description and some of the featured pieces on the museum’s website.

I also had not heard—or, if I had heard, did not remember—that Pelton’s grandmother was involved in a major scandal in late nineteenth-century New York. Which is, in a way, how Pelton came to be, since her mother fled to Germany to escape the trauma and encountered her father, another ex-pat fleeing traumas of his own.

I also had not heard—or, if I had heard, did not remember—that Pelton’s grandmother was involved in a major scandal in late nineteenth-century New York. Which is, in a way, how Pelton came to be, since her mother fled to Germany to escape the trauma and encountered her father, another ex-pat fleeing traumas of his own.Many of Pelton’s more dramatic and mature art works are not yet in the public domain, but you can see her style developing in the two works from 1915 and 1917 included in this post. And by all means listen to the interview and conduct your own exploration into the works of the “desert transcendentalist” who, almost sixty years after her death, has yet to attain the recognition that is her due.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. You can also find a short transcript on the Literary Hub and listen to the interview there if you wish.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. You can also find a short transcript on the Literary Hub and listen to the interview there if you wish.Like the better-known and perhaps luckier Georgia O’Keeffe, the American painter Agnes Pelton also found her unique vision in the western desert. As Mari Coates details in our conversation, Pelton and O’Keeffe took art classes from the same teacher and had parallel careers in several ways, yet Pelton is relatively unknown despite a number of major exhibitions during her lifetime and one traveling the United States even as this interview airs.

But Pelton’s time in the California desert is only a small part of the captivating story traced in The Pelton Papers. Born in Germany, where her ex-pat parents connected while escaping family scandals and tragedies, Pelton came to New York at the age of seven. A sickly girl in a dark and brooding house, she survived her childhood with a deeply religious grandmother, an absent father, a strong-minded mother who supported the family by giving music lessons, and no social life to speak of by losing herself in colors and paint. That set her on a path that led, through training in modernism and more traditional instruction in Italy, to a deeply spiritual, intensely personal understanding of her own artistic mission. In this beautifully written novel, Mari Coates—whose own family had a long and productive friendship with Pelton—draws on stories she heard growing up and numerous other sources to portray an emotionally complex, sometimes troubled, but always gifted heroine whose resilience and eventual triumph will warm your heart.

Images: West Wind (1915) and Room Decoration in Purple and Gray (1917), public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on April 17, 2020 06:00

April 10, 2020

Writing Up a Storm

Just over a year ago, Patrycja Podrazik, who writes as P. K. Adams, and I decided to collaborate on a novel—or novels. I’ve mentioned this joint project on the blog before, but now that we’ve passed our first milestone, I thought I’d bring you into the process a little more.

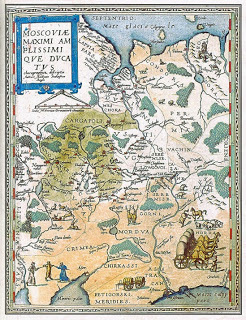

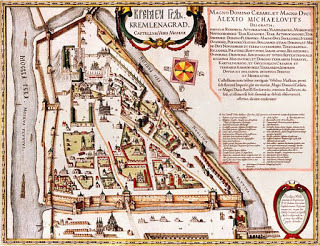

Just over a year ago, Patrycja Podrazik, who writes as P. K. Adams, and I decided to collaborate on a novel—or novels. I’ve mentioned this joint project on the blog before, but now that we’ve passed our first milestone, I thought I’d bring you into the process a little more.The decision was relatively simple: she writes mysteries set in sixteenth-century Poland; I write political romances set in sixteenth-century Russia—that makes us the only two novelists we know producing Tudor-era fiction in English about eastern Europe and beyond. And we like each other’s work.

That said, our acquaintance with each other up to that point didn’t go far beyond a New Books in Historical Fiction interview. So we worked on finding out more. A couple of long phone calls and e-mail exchanges led to an in-person meeting at the Historical Novel Society in June and, eventually, a detailed outline of the book we planned to write.

That in itself was a departure for me, as I wrote on this blog last spring. My outlines look more like doodles. At best, I have a list of story events—intended to spark ideas and keep me focused on an endpoint but otherwise useful primarily as a measure of just how far any given story has deviated from its original plan. With Song of the Sisters, that’s 180 degrees. Most of the others haven’t veered that far off course, but only The Shattered Drum and Song of the Siren made it to the end without a major overhaul. Song of the Shaman went round in circles for a while before I figured out at last how to get it where it needed to go.

That in itself was a departure for me, as I wrote on this blog last spring. My outlines look more like doodles. At best, I have a list of story events—intended to spark ideas and keep me focused on an endpoint but otherwise useful primarily as a measure of just how far any given story has deviated from its original plan. With Song of the Sisters, that’s 180 degrees. Most of the others haven’t veered that far off course, but only The Shattered Drum and Song of the Siren made it to the end without a major overhaul. Song of the Shaman went round in circles for a while before I figured out at last how to get it where it needed to go. But following the characters’ bliss doesn’t work so well when someone else has to come in and write the next chapter. Hence the detailed outline, which we followed most of the time. We did adjust the plan as needed, especially in the second half of the manuscript, but by then we’d learned a lot more about each other—our strengths and weaknesses and quirks. We knew more about the characters, too, as well as the details of past scenes that we didn’t want to repeat. By then, the story had progressed to the point where a good ending writes itself, so the changes were more like wrinkles on a surface than fundamental shifts. The last ten chapters or so we exchanged one at a time, offering comments and suggestions until we both felt comfortable that the text said what we wanted it to say.

We settled on a working title early on, These Barbarous Coasts—a reference from one of the early English travelogues produced by George Turberville, who traveled to Russia with the Muscovy Company and was, to put it bluntly, not impressed by what he found there. The title was mostly so I could engage in my preferred form of editing: creating an e-book and reading it through, marking whatever jumps out at me. Patrycja eventually confessed that she’d never liked it, and we came up with a new name: The Merchant’s Tale.

But the big news is that the first draft is done—and in record time. We applied fingers to keyboard right around New Year’s Day, and 85,000 words and 28 chapters later, we reached the end on April 7. It’s a good, solid beginning, too—not perfect, because no rough draft is (or why would they be called “rough”?), but respectable, even engaging. And we’ve established a good working relationship. Indeed, we know far more about each other as writers than we did fourteen months ago.

What else can I tell you without revealing too much? A Polish merchant, traveling to Moscow to see his long-promised bride and her brother, encounters a group of English sailors, subjects of the Tudor king Edward VI. The Englishmen had set out from London intending to find a northeast passage to the Orient, but a series of accidents dumps them in Russia instead. They end up at the court of Ivan the Terrible, where his in-laws, later known as the Romanovs, take an interest in the English merchants. Life looks good. But this is a novel, so you know trouble finds them.…

What else can I tell you without revealing too much? A Polish merchant, traveling to Moscow to see his long-promised bride and her brother, encounters a group of English sailors, subjects of the Tudor king Edward VI. The Englishmen had set out from London intending to find a northeast passage to the Orient, but a series of accidents dumps them in Russia instead. They end up at the court of Ivan the Terrible, where his in-laws, later known as the Romanovs, take an interest in the English merchants. Life looks good. But this is a novel, so you know trouble finds them.…Images: Anthony Jenkinson's map of Moscovia (late 16th-century); 17th-century map of the Moscow Kremlin (based on a 1604 drawing) public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on April 10, 2020 06:00

April 3, 2020

Interview with Stacey Halls

In March last year, I wrote a post about Stacey Hall’s captivating debut novel,

The Familiars

. I was delighted to receive her second novel, due out from MIRA Books next Tuesday, but I’d already signed up to interview another author for my podcast. So I asked if Stacey would be willing to answer some written questions, and she was kind enough to say yes.

In March last year, I wrote a post about Stacey Hall’s captivating debut novel,

The Familiars

. I was delighted to receive her second novel, due out from MIRA Books next Tuesday, but I’d already signed up to interview another author for my podcast. So I asked if Stacey would be willing to answer some written questions, and she was kind enough to say yes.So read on for my questions and her answers, and definitely seek out The Lost Orphan. I promise you: I couldn’t put it down!

The Lost Orphan is your second novel. What can you tell us about your earlier book, The Familiars?

The Familiars is set during the Lancashire witch trials that took place in the north of England in 1612. It’s about two women—one of whom is accused of witchcraft, which was a crime punishable by death—and how they try to save each other’s lives. I grew up in Lancashire, and the witches are very much a part of the fabric and history of the area, so I knew about them from a young age. Eleven people were accused of witchcraft; one of them died in prison, one was acquitted and ten were executed. I had the idea for the story when I visited Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire, an Elizabethan property that has views of Pendle Hill, which is synonymous with the witch trials. I wanted to write a story about the trials told from the point of view of someone who lived in this house, who was trying desperately to save someone.

The Lost Orphan—called The Foundling in the UK—opens in London in 1754. A young woman named Bess Bright is taking her newborn baby, Clara, to the Foundling Hospital. Who is Bess, and what has driven her to surrender her infant daughter?

The Lost Orphan—called The Foundling in the UK—opens in London in 1754. A young woman named Bess Bright is taking her newborn baby, Clara, to the Foundling Hospital. Who is Bess, and what has driven her to surrender her infant daughter? Bess is a shrimp seller from Billingsgate Market, which is London’s fish market. She is a street hawker, selling her produce from a basket she carries on her head. The portrait Shrimp Girl by William Hogarth inspired her job—I came across the painting while researching the period, and thought this girl just looked luminous.

She has a baby daughter after a one-night stand with a merchant, and as she is unmarried and lives with her father and brother, and has to work, she is forced to surrender the baby to the care of the Foundling Hospital. She is a victim of circumstance—there was a lot of shame around illegitimate pregnancy at that time, perhaps not as much as in the Victorian era, however her low status and poverty leave her no choice but to give up her child.

Clara almost doesn’t make it, because entrance to the hospital depends on a lottery system. What can you tell us about that?

Lottery night was devised as a “fair” admissions process in the hospital’s early years. Women were invited to the hospital with their babies, where they would draw colored balls from a bag while wealthy revelers watched. The color of the ball determined whether or not their child was admitted—a white ball meant their child got a place, red put them on the waiting list, and black meant they’d lost. It was such a striking image, with such high stakes that determine the course of the lives of the woman and her child, that I made it the first chapter of the novel.

Six years pass, and Bess slowly gathers her savings. But when she goes to reclaim her child, what does she discover?

Bess is told that child 627—all the children were Christened on admission and given new names, but Bess remembers her daughter’s number—has been collected by her “mother,” who has given Bess’s name and address. The child’s father is dead, so Bess sets out to find out who has claimed her daughter and why.

At this point, the novel switches from Bess’s point of view to that of Alexandra Callard. Who is she, and what connects her to Bess?

I can’t say much without giving away who she is! I don’t want to spoil it for anyone.

And tell us, please, about Dr. Mead and his part in the story.

Dr. Mead is Alexandra’s friend, who works at the Foundling Hospital and lives not far from her in Bloomsbury. His grandfather (also Dr. Mead) is the only “real” character in the novel—he was one of the Foundling Hospital’s founding members and physician to the royal family—but he only appears in one scene.

What are you working on now?

I’m writing my third novel, which is set in Edwardian Yorkshire and is about a nanny who goes to work with a wealthy but troubled family there.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Stacey Halls was born in 1989 and grew up in Rossendale, Lancashire. She studied journalism at the University of Central Lancashire and has written for publications including The Guardian, Stylist, Psychologies, The Independent, The Sun, and Fabulous.

Stacey Halls was born in 1989 and grew up in Rossendale, Lancashire. She studied journalism at the University of Central Lancashire and has written for publications including The Guardian, Stylist, Psychologies, The Independent, The Sun, and Fabulous. Her first book, The Familiars, was the bestselling debut novel of 2019. The Lost Orphan is her second novel. Find out more about her and join her reading club at http://www.staceyhalls.com.

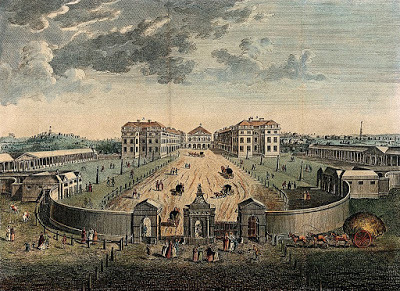

Images: William Hogarth, Shrimp Girl (1740s), public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Foundling Hospital. London (1753), https://wellcomeimages.org via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on April 03, 2020 06:00

March 27, 2020

Bookshelf, Spring 2020

Hard as it is to believe, another season has come and gone, and Spring has officially arrived. A strange spring, with a rather bizarre epidemic that blew up out of nowhere and is at once mild and deadly, requiring unprecedented measures of quarantining and self-isolating and social distancing to restrain its rapid spread long enough to allow the world’s medical systems to catch up and wreaking havoc on the global economy.

But for all of us confined to our homes until further notice, books offer one reliable refuge. Here from my bookshelf are several literary journeys to a variety of times and places, from the contemporary Cotswolds to nineteenth-century Sicily and the New York art scene, ca. 1910. I’m sure you can find something here to lighten the pressures of life in lock-down.

Stefania Auci,

The Florios of Sicily

, trans. Katherine Gregor (HarperVia, 2020)

Stefania Auci,

The Florios of Sicily

, trans. Katherine Gregor (HarperVia, 2020)This family saga was a bestseller in Italy, hence its translation and republication here. It came to me for a potential interview, but I couldn’t fit it in even though the subject matter looks fascinating and I love to explore literary places that don’t come my way very often. I’m not quite sure when I’ll get to it, because I have a lot of interviews underway at present—including two for New Books in History that I have yet to schedule. But if anywhere can offer an escape from a world hovering on the brink of disaster into a past filled with sunshine and passion, nineteenth-century Sicily must be that place. Just the cover makes me think of summers at the beach.

Mari Coates, The Pelton Papers

(She Writes Press, 2020)

A look at Agnes Pelton, a twentieth-century American artist whose work I didn’t know before encountering this lovely, lyrical exploration of her life. Born in 1881, Pelton survived a sickly childhood and lived to be almost eighty. Over her long career, she developed from a mostly realistic painter, if with hints of fantasy, into a “desert transcendentalist” who combined the spiritual principles of Vasily Kandinsky and Madame Blavatsky to create abstract works rich in brilliant colors. I’ll be talking with the author next week for New Books in Historical Fiction, so check in and give us a listen once that interview goes live around the middle of April.

Michelle Cox,

A Child Lost

Michelle Cox,

A Child Lost

(She Writes Press, 2020)

Book 5 of a series that began in 2016 with A Girl Like You, by an author I interviewed regarding the first two back in 2017. By now, Clyde and Henrietta are married, but the cases keep on coming, even though Clyde has resigned from the Chicago police to work in his family business. Set in the 1920s, this series explores the seamier side of city life as well as the mansions on the North Shore.

It would be unfair to give away spoilers, but check back on the blog early in May to see what the author is willing to reveal about A Child Lost as well as its immediate predecessors—A Promise Given and A Veil Removed.

Janice Hadlow, The Other Bennet Sister

(Henry Holt, 2020)

The thirst for Austen spin-offs continues unabated, and information about this one landed in my in box unexpectedly this week. Like Pamela Mingle’s charming The Pursuit of Mary Bennet (William Morrow, 2013), this novel by a long-time BBC administrator tackles the least attractive middle sister, Mary. It’s garnering rave reviews, and I’m as big an Austen fan as anyone—especially Pride and Prejudice. So I look forward to seeing Hadlow’s take on a perennial favorite. I’ll be talking with her for my May interview.

Stacey Halls,

The Lost Orphan

Stacey Halls,

The Lost Orphan

(William Morrow, 2020)

Captivating, beautifully written novel about a young woman forced to give up her illegitimate newborn daughter, Clara, to London’s Foundling Hospital (the original UK title is The Foundling). That’s hard enough, since the hospital holds a lottery to determine which of the many unwanted babies it will keep, and Clara barely makes the cut. But when, after five years, Bess manages to scrape together enough of her earnings as a shrimp seller to retrieve Clara, she learns that someone claiming to be her baby’s mother took Clara the very day Bess left her daughter in the hospital’s care.

Bess decides to get her baby back. This story about two eighteenth-century women, each desperate in her own way, twists and turns in the most satisfying and unexpected ways, but at its heart it’s a tale of motherhood, its trials and triumphs. Stacey Halls will join me here next week to talk about this and her previous novel, The Familiars.

And just for fun—because what’s better than a brand-new mystery series with twenty books already written?—Agatha Frost,

Pancakes and Corpses

(Pink Tree Publishing, 2017).

And just for fun—because what’s better than a brand-new mystery series with twenty books already written?—Agatha Frost,

Pancakes and Corpses

(Pink Tree Publishing, 2017). I love historical fiction; don’t get me wrong. I love interviewing authors and thinking about their books. But once in a while it’s nice to put my brain on hold and let a gifted contemporary writer sweep me into a world where it makes perfect sense that a café owner and baker (or a lighthouse librarian, like Eva Gates’ Lucy, with the help of a resident Burmese cat) could be continually confronted by dead bodies and cases only she can solve.

I came to this book via Courtney J. Hall, one of my two co-founders at Five Directions Press, who loves the entire series. When I saw on Twitter that Agatha Frost was giving away six of her titles for free because of the pandemic, I downloaded them, then sprang for the first two in the series so I could get in at the beginning. I started this one a few days ago, but now that I have a bit of free time between interviews, I hope to tear through the rest of it. And if the end is as good as the beginning, I have lots more to go....

Published on March 27, 2020 06:00

March 20, 2020

Working from Home

With the sudden need for “social distancing” in response to the coronavirus outbreak, many people have to work from home who never did before. It’s not an easy transition, especially for a natural extrovert (which as a novelist I am not, or I would spend fewer hours alone in my office communing with imaginary people). Not knowing whether the new situation will last for weeks or months only makes the adjustment harder. But it can be done.

With the sudden need for “social distancing” in response to the coronavirus outbreak, many people have to work from home who never did before. It’s not an easy transition, especially for a natural extrovert (which as a novelist I am not, or I would spend fewer hours alone in my office communing with imaginary people). Not knowing whether the new situation will last for weeks or months only makes the adjustment harder. But it can be done.I know. I started working from a home office in 1994, and I love it. At the time, it was a practical decision: my son had just turned six, and we’d come through an entire month’s worth of ice storms. The schools closed day after day, and when they did open, they started two hours late, which for morning kindergarten was the same as not opening at all. I’d given up a teaching job because the scheduling didn’t work, and being unemployed made that January possible for my family. But when I saw the ad for an editorial position in my specialty that let me work remotely, I wasted no time in submitting an application. I’ve never looked back.

So for those of you facing this reality for the first time, I thought I’d use this post to offer a few suggestions for making teleworking feasible. I hope you’ll find them useful—and by all means share your own tips in the comments. There are many more things I could say, but I’ll focus on these five.

Be dedicated. Sure, one advantage of working from home is that you can monitor food bubbling in the slow cooker and run the laundry in the background, but those distractions can grow until they eat up the workday. It’s important to keep them in their place. You made it through the day without cleaning the bathroom before, and you can do it now. To paraphrase an advice book I read back in the 1990s, “If you can complete the chore in 90 seconds, do it. Otherwise wait till the workday is done.”

Of course, a particular hurdle right now is that so many schools and child care centers are closed, which further complicates life for working parents, even teleworking parents. But if you can swap time with another parent (preferably a co-parent) or find an older child or relative to babysit or, with kids over the age of eight or so, get the young ones involved in projects or caught up in a good book, you can clear enough individual hours to keep domestic life from overwhelming the time available for work. This is a good time to loosen restrictions on TV watching and similar activities, so long as the kids understand that it won’t always be that way.

Stay connected. Exactly how this happens depends in part on your job and your personality, but it’s an essential element of making teleworking less burdensome. When I started, I had all my editors on speed-dial and talked to them several times a day. Now it’s e-mail that keeps me in touch. Others rely on video-conferencing or Messenger. It’s not the same as hanging around the water cooler, and working from home may mean you don’t get the latest gossip or updates on company policies, but it will help you avoid stir-craziness and a sense of isolation.

Be flexible. It’s not going to be perfect. It never is, but the domestic sphere has its own special challenges. The cat barfing on the rug in the middle of the video conference, the kid having a meltdown right when you’re humming on that memo, the spouse walking around chatting just when you picked up the phone to call your boss—these are all examples of what P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster described as life sneaking up on us with a sock filled with sand. Good news: the person on the other end of the call probably has similar issues—or will soon. Laugh, if possible, and share the silly story, then move on.

Separate work from life. The nice thing about an office elsewhere is that you can walk out and lock it at the end of the workday. Home offices don’t come with that perk. But you can create it. Keep your office e-mail off your phone and tablet; change your clothes; pour a glass of wine (in moderation!); pick up a book, which can’t interrupt you with demands for answers to work-related questions. Even starting the same domestic chore—cooking, for example—that threatened to distract you at 10 AM can signal to your brain that the workday is over and relaxation can begin. And last but not least,

Enjoy the upside. For as long as you’re teleworking, you can’t get stuck in traffic. You don’t need to dress up for work. There’s no charge for lunch, and you can eat whatever you have on hand. You can start the coffee pot whenever you want, play the music you like in the background, have a cup of tea whenever the fancy strikes. Instead of spending time at staff meetings, you can monitor what’s going with your kids. And you still have a job. With so many people losing their sources of income due to the shuttering of businesses, that may be the biggest benefit of all.

Who knows? By the time the crisis ends, you may be just a bit sorry to get back in the car or on the train and leave that cozy home office behind.

Images of home offices purchased by subscription from Clipart.com, nos. 37476468 and 110224490.

Published on March 20, 2020 06:00