C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 15

July 16, 2021

Choreographing the Royal Wedding

Writing historical fiction, even about a period one knows well, demands a lot of research. Many novelists, including myself, enjoy that part almost as much as plotting the story and creating characters. Of course, there are times when all I want is a quick answer: How much can you see through a mica pane? How would a sixteenth-century doctor treat an arrow wound? Exactly how do you store spider webs so you have them on hand to treat a future injury?

Writing historical fiction, even about a period one knows well, demands a lot of research. Many novelists, including myself, enjoy that part almost as much as plotting the story and creating characters. Of course, there are times when all I want is a quick answer: How much can you see through a mica pane? How would a sixteenth-century doctor treat an arrow wound? Exactly how do you store spider webs so you have them on hand to treat a future injury?But establishing the broader picture can be important too. Each novel addresses different areas of life and therefore raises new questions that demand answers. For that situation, works offering comprehensive, in-depth examination of specific topics provide the perfect solution. This is when I put on my rather dusty historian’s cap and dive into the academic literature.

For my current work-in-progress, Song of the Storyteller (Songs of Steppe & Forest 5—and yes, 4 is still to come out, but it’s in the final stages), Russell E. Martin’s A Bride for the Tsar: Bride-Shows and Marriage Politics in Early Modern Russia has become a kind of bible. There are other books I turn to with every new addition to the series, but this one has a particular relevance for the current story. So it’s no surprise that I jumped at the chance to interview Martin for New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies on the appearance of his latest study about what happened after the bride show, The Tsar’s Happy Occasion: Ritual and Dynasty in the Weddings of Russia’s Rulers, 1475–1725.

Just as I expected, he has a lot of fascinating things to say about the important political statements that could be conveyed by a royal wedding. And you thought it was all about heart-shaped confetti and gift registries.

So give the interview a listen. It’s a lot of fun. The book, too, is a great read, filled with stories of family conflicts, international intrigue, disgruntled nobles, and dirty tricks. But whether you have the mental energy to tackle a serious study after a long day at work or not, you can watch one of my heroines carrying the bride’s train a few books from now.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Russian & Eurasian Studies.

The dominant impression of Russia in the news media and politics, even today, is that it is and always has been an autocratic power controlled by a single despotic ruler. But historians of the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries have long realized that this vision was to some extent a myth projected by the central authorities to support a system that was in fact oligarchic but competitive in nature. A fundamental step in recognizing the gap between that myth and reality was the identification of marriages between aristocratic clans as a determinant in political alliances, followed by a new understanding of patron-client relations and other interpersonal connections within the elite.

In The Tsar’s Happy Occasion: Ritual and Dynasty in the Weddings of Russian Rulers, 1495–1745 (Cornell University Press, 2021), Russell E. Martin explores the ways in which the weddings of tsars and lesser members of the royal family worked to integrate brides and their families into the elite while moderating tensions among the nobility. The whole occasion was elaborately choreographed and developed over time as the needs of the original dynasty, the Daniilovichi, to extend and sustain the lineage by managing the number of heirs gave way to the new Romanov dynasty’s attempts to establish its legitimacy, followed by a squabble for power between two branches of the later Romanovs (Peter the Great and his descendants). And the stakes were high—the book is full of examples of poisoned brides, recalcitrant exiles, bridegrooms executed for failing to judge the balance correctly, and more. Through this in-depth but beautifully written study, we gain a new appreciation of the importance of ceremony and ritual in creating and promoting visions of how the world does and should work at specific points in time.

July 9, 2021

Shakespeare in Love

As a historian and a historical novelist, I always, in a sense, have a foot in the past. I have also read enough about the past to know that I really wouldn’t want to spend much time there, especially as a woman who, by the standards of most centuries before our own, definitely does not know her place. Yet even I sometimes think, “Oh, if I could just spend one day in 1530s Moscow—suitably vaccinated and dressed, with a translator chip to handle the language and some kind of handy but undetectable recording device. What I could do with the sounds and smells and sights of this place that I have studied most of my life yet can never experience in the flesh!”

I’m sure most of my fellow writers of historical fiction feel the same way. The past is, as David Lowenthal memorably noted, “a foreign country”—and one we can never visit. All our research into attitudes and lifestyles and even events come up short at the insurmountable barrier that time as we know it flows in one direction. The results of all that work are more than speculation but less than fact, which is the reason that historical fiction can be plausible and well informed but never accurate, in the scientific sense.

Still, the yearning to travel in time lingers, and there are few better ways to satisfy the urge than through reading a thoughtful, funny novel like Jessica Barksdale Inclán’s The Play’s the Thing, in which a junior professor (also named Jessica) struggling with the need to get tenure and the aftermath of certain bad decisions in her personal life wakes up one morning in Shakespeare’s clothes cupboard. She’s half-convinced she’s crazy, or at least caught in an astonishingly detailed dream. But as the author explains in my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview, the character Jessica plows through with the help of soap, water, a good memory of all she’s read about Shakespeare’s life and world, and a strong sense of humor that serves her well. Will she make it home or change her definition of home? To find out, you have to read the book.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. You can also find a transcript featuring parts of the interview on LitHub.

In a sense, those of us who love historical fiction live vicariously in the past. Many of us also fantasize about traveling in time—meeting our favorite writers in the flesh, hanging around with royalty, living the aristocratic lifestyle. We tend to forget or understate the very real benefits of the present, amenities we take for granted (indoor plumbing, central heat and air conditioning, refrigeration) and intangibles such as human rights and the presumption of innocence, still implemented in patchwork fashion across the globe.

Professor Jessica Randall, modern-day heroine of The Play’s the Thing (TouchPoint Press, 2021), experiences this conundrum firsthand. One evening, while she is doing her best to stay focused on a dreadful amateur production of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, she allows herself a brief escape—only to end up in an Elizabethan theater, watching an original performance of the play with (as she realizes only later) the Bard himself in the role of Shylock. She stumbles out of that setting and back into her seat in the twenty-first-century auditorium, but later that evening, turned somnolent by student essays and one too many glasses of wine, Jessica finds herself locked in what turns out to be William Shakespeare’s cupboard. When he at last deigns to unlock the door, he informs her that she is the latest among hundreds of screaming Jessicas who have been making his life hell for months.

Will assures Jessica that she will soon vanish into the ether and return whence she came. She’s convinced it’s an elaborate dream, because how could it be real? But when dawn arrives, she is still in 1598, Will is asleep on the mattress next to her, and she can hear rats rustling under the filthy straw. Perhaps it’s not a dream after all. At that point, to keep herself sane on the off-chance that she can’t find a way home, Jessica decides she’d better apply her knowledge of the future to clean up Shakespeare, his rooms, and her own act before those rats in the corner give them both bubonic plague.

Jessica Barksdale Inclán approaches her main character’s dilemma (there’s a funny story in the interview about how author and character come to have the same first name) with a deliciously light touch. The dialogue sparkles, Jessica’s struggles and flaws never fail to ring true, and the contrast between her unmistakably modern views and Will Shakespeare’s Elizabethan take on life are simultaneously revealing and thought-provoking. If you’re looking for a scientific explanation of time travel (assuming that such a thing exists), you won’t find it here, but the novel is, in every respect, a fun read. It will stay with you long after you reach the end.

Image: Procession of Characters from Shakespeare’s Plays, unknown nineteenth-century artist, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

July 2, 2021

Interview with Joy Lanzendorfer

Although California certainly had a long history before 1848, the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in that year caught the attention of many on the East Coast who might otherwise have stayed at home. In her new novel,

Right Back Where We Started From

(Blackstone Publishing, 2021), veteran writer Joy Lanzendorfer traces the effects of that initial push westward on three generations of one California family. She has a lot of interesting things to say, so without more ado, I launch into my questions!

Although California certainly had a long history before 1848, the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in that year caught the attention of many on the East Coast who might otherwise have stayed at home. In her new novel,

Right Back Where We Started From

(Blackstone Publishing, 2021), veteran writer Joy Lanzendorfer traces the effects of that initial push westward on three generations of one California family. She has a lot of interesting things to say, so without more ado, I launch into my questions!At its heart, this is a novel about the history of California, told through the lives of three women: Vira Sanborn; her daughter, Mabel; and her granddaughter, Sandra. What drew you to write this book in this way?

Sandra is loosely based on my grandmother, who was a dramatic presence in my life. I heard lots of stories about her and my grandfather growing up, but I never knew which of those stories were true. It made me think about family myths and how generational identity feeds into personal identity. If you grow up believing stories about your family that aren’t true, and you build the foundation of yourself on top of that, what does that say about who you are? This is Sandra’s struggle in Right Back Where We Started From.

At its core, this is novel about what happens when women pursue greed and ambition with the same ruthlessness as men. It’s a matriarchal story about a grandmother affecting a daughter and a daughter in turn affecting her child, and how dark and messy those dynamics become when mixed with American ideas about success and wealth.

Your story begins, in effect, in the middle, in 1913. Mabel is talking to Sandra, then called Emma. Why start there?

I needed a scene to show the formation of Sandra’s beliefs about herself. In that chapter, which occurs when she’s a child, Mabel is reinforcing the myths that their lives are based on, which is that their family was once rich and successful and it was all stolen from them. It was important to show that Sandra has been fed these beliefs and to suggest to the reader that they aren’t entirely true, which is why the scene ends with Mabel making the dubious claim, “Don’t worry, your mama will always tell you the truth.”

The scene underscores the complexity of their mother-daughter relationship. The major way Sandra feels love from her mother is when she talks about how great their family used to be, because Sandra is special by association and is therefore receiving attention and validation. It’s the major way Mabel and Sandra connect emotionally, and so these beliefs are an important part of Sandra’s adult identity later on.

We next connect with Sandra at twenty-six, in a funny scene where she is in Hollywood and dressed in a sandwich board advertising an orange juice company. What’s going on here, and what does it reveal about Sandra?

When we meet Sandra as an adult, it’s 1932 Hollywood. She has a job wearing a sandwich board over a scanty orange dress to advertise Rayo Sunshine, a new juice shop that’s opened up, which happens to be shaped like a giant orange. Sandwich boards aren’t a common way to advertise anymore, although we still pay people to wave signs and dance around on street corners. Sandra is supposed to hand out coupons for a free glass of orange juice. She figures she’ll use the opportunity to try to get discovered by a Hollywood producer and goes over to Paramount Studios to hand out her coupons. She thinks she has invented a new way to get attention (and get paid for it at the same time), but soon learns that there are few tricks that haven’t already been tried when it comes to people seeking fame.

Early on, we get a sense that all is not as it seems in the Sanborn family. Sandra receives some letters from her ex-husband that cast doubt on her own beliefs about her background. What does she discover?

The letter that is forwarded from her ex-husband is from a man named John Hollingsworth, who Sandra has never heard of before. In the letter, he says that he’s her father. This is shocking to Sandra, who has always been told that her father was Arthur Beard, a rich prune rancher who died in the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. But the letter includes a picture of Mabel as a young woman, so Sandra knows John Hollingsworth at least knew her mother. Thus she’s confronted with a mystery—who is John Hollingsworth, and is he really Sandra’s father?

She doesn’t respond to these disturbing letters, although she keeps them for years. Why doesn’t she follow up, and why not just throw them away?

This is the key to Sandra’s psychology, basically. She knows, on some level, that she hasn’t been told the whole story about her family, but she’s invested in the idea that she comes from special stock. To admit that might not be the case is truly scary to her. So her solution, when presented with John Hollingsworth’s letters, is to ignore them. And yet deep down she knows there’s something to the letters, so she doesn’t throw them away either. She’s essentially in denial. And since she isn’t willing to look at the truth, the book begins to tell you what she can’t face: the real story of her family.

We then jump back in time to Portland, Maine, in 1851, where Vira Webb and Elmer Sanborn meet under extraordinary circumstances. Please fill us in both on the lightning incident and what causes the Sanborns to leave Maine for California.

You can read the chapter here (it’s a quick read). It’s the story of how Sandra’s grandparents meet and involves Elmer saving Vira when she’s almost struck by lightning. It’s a play on the idea of being struck by love, but despite the wonderful way they meet, reality will soon set in when Elmer decides to take Vira with him to the California Gold Rush.

In alternation with chapters featuring Sandra, we follow Vira throughout her cross-country journey, then switch to Mabel as a girl and young woman. What can you tell us about her?

Mabel is probably the most difficult character in the book. She grows up very cloistered as a young lady in Victorian San Francisco society. Vira is determined to keep Mabel safe and find her a good marriage, and Mabel chafes at the constraints. She can’t even take a walk by herself, and she feels like her future is planned out for her. So she does what any teenager would do: she rebels. She sneaks out. It puts her in a disastrous situation that leads to her downfall and being disinherited by her parents.

When we meet Mabel again, she’s a different person, someone who has had to do a lot of hard things to survive. She regrets her teenage rebellion but is very angry that one mistake caused her to lose everything. She’s determined to regain what she lost, but the wild side of Mabel, the passionate part that makes her run toward adventure, is still there, leading to some bad decision making.

All three of these women, sooner or later, realize that their ambitions can only be achieved through the men in their lives. Each of them responds in ways that undermine their relationships with their husbands. What can you tell us about this element of the novel?

Someone told me there isn’t a lot of romance in this book, but I think most of the relationships start out great. It’s just that the novel reflects the transactional nature of marriage in the past. In Vira’s case, marriage means losing power. She’s shocked Elmer wants her to go with him to the Gold Rush, which to her means leaving everything she knows for “the uneven gamble of striking it rich.” But she doesn’t have much choice in the matter, so she tries to be a good wife and believe in her husband’s promises. When that trust is broken dramatically in the Nevada desert, she resolves to take control of the marriage—which doesn’t end well.

In Sandra’s case, she meets Frederick during the Great Depression. He’s a German immigrant, a photographer, and—like Sandra—a charismatic and manipulative person. Sandra is attracted to him, but she also wants to marry someone rich. Frederick isn’t interested in being rich. So again, there’s a power dynamic that has to do with the economics that come with marriage and the imbalance between men and women. Marriage is about love, but it’s also a partnership, and in these cases, these partnerships are on unequal footing. It leads to some problems, let me tell you…

This novel came out in May 2021. Do you already have another one in the works?

Yes, I do. I’m working on a novel about a school bombing. I have an essay collection in the works too. I just need the time to work on them both!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Joy Lanzendorfer writes both fiction and nonfiction, which she has published in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post, on NPR and with the Poetry Foundation, and in many other venues. She holds an MA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. Right Back Where We Started From is her first novel. Find out more about her and her writing at http://www.ohjoy.org.

Image: A woman and three men panning for gold in California, 1850—public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

June 25, 2021

Interview with Jonathan Kos-Read

I agreed to read Jonathan Kos-Read’s debut novel,

The Eunuch

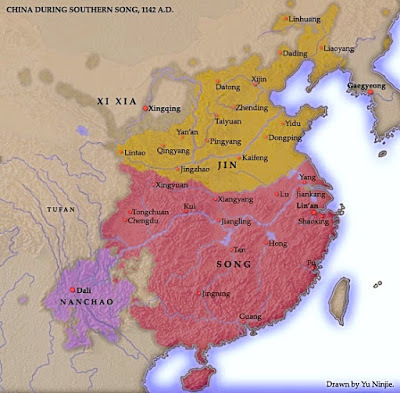

, because it is set in early twelfth-century China, a period when a Manchurian people known as the Jurchen had established control over the northern portion of the once-unified empire. This setting appealed to me because, in language and culture, the Jurchen had links to the Mongols—and therefore to the Tatars who form such an important element of my Russian novels. (The Mongols also conquered the Jurchen, who returned four hundred years later as China’s last dynasty, the Qing.)

I agreed to read Jonathan Kos-Read’s debut novel,

The Eunuch

, because it is set in early twelfth-century China, a period when a Manchurian people known as the Jurchen had established control over the northern portion of the once-unified empire. This setting appealed to me because, in language and culture, the Jurchen had links to the Mongols—and therefore to the Tatars who form such an important element of my Russian novels. (The Mongols also conquered the Jurchen, who returned four hundred years later as China’s last dynasty, the Qing.) I discovered only later (and I know, this says a lot about me) that Jonathan Kos-Read spent much of his career as an actor in Chinese film and television. But now he has turned to fiction, and I am delighted to share his answers to my questions. He has a lot of interesting points to make, so be sure to read right through to the end. Then go buy the book!

You appear all over the Internet because of your acting career and your long residence in Beijing. What made you decide to write a novel?

First, as an actor of course I’m expected to write screenplays. And of course, I did. I wrote two of them. Poured my heart into them. Sweated blood over them. And in the end three people read them: a producer, my best friend, and my mom. A screenplay isn’t the finished product. It’s the “instruction manual” for the finished product, which is the actual movie. So even if you write Citizen Kane, only a hundred people are ever going to read it. And they will hate or love the actors and the director, not you. You the writer are just a random unknown throwaway in the credits. Let’s be honest, how many names of authors of instruction manuals do you know? So after having written those two screenplays, I swore never again to write another “instruction manual.” I would only write the final product.

Second, again as an actor, most of your acting life consists of doing it in bad screenplays. I mean, maybe you’re lucky and you do Shakespeare your whole life or you constantly work with Martin Scorsese. But for the rest of us, our entire working life consists of getting handed a script, reading it, sighing, and thinking “again?” And I don’t mean just bad. I mean literally like don’t rise even to the level of basic competence. Are literally not even stories. That’s true everywhere—Hollywood, Bollywood, Chinawood, everywhere. And it’s mostly because you have writers writing under intense, brutal time pressure. And then they must give these hastily constructed—basically not finished—stories to their bosses, producers, who (almost always) know nothing about storytelling. And who not only know nothing but in fact think knowing nothing is fine because they know the money side of the business—the distribution, the financing, etc. So they then take these already bad, unfinished stories and make them worse. I’ve been a professional actor for twenty years. I’ve acted in almost two hundred films. I guarantee you this is true.

After that process has occurred—the one that has produced a piece of garbage of a screenplay—us actors get handed the result. And if you want to be a successful actor or even work regularly—you must take these awful scripts and try to find some sort of contorted logic to fill in all the logical gaps, all the unrealistic (un-human) behavior of the characters, or even just the parts that are so boring you don’t think you can read another page—and then make the acting work, or you must rewrite them and hope nobody notices or the director agrees to it. And that process teaches you a lot about writing. So in my head I have this vast compendium, not figuratively but in fact literally, of almost every mistake a storyteller can make. And so I decided I was going to write a story that threaded the very very narrow path that avoided every single one of those mistakes, and at the end, just by virtue of avoiding them, it might actually be interesting. It was like a test of myself and whether I was wrong about what constituted a story, what was interesting, what was structure, and just how to construct something that would get people to read the next sentence, turn the next page, and then be satisfied when they read the last word. It would be a check on my deep cynicism and the creative heart that had died inside me from being an actor all these years. Reading great books and watching great movies taught me a lot. But acting for twenty years in bad ones taught me more.

Finally, I’ve always loved reading, and inside every reader is a writer. So I dreamed one day people would be reading the novel I wrote.

And out of China’s long history, what drew you to the twelfth-century Jurchen (Jin) Dynasty for your setting?

I grew up in the ’80s in the US during the height of the cold war. Mutually Assured Destruction. We used to do “nuclear attack” drills at school, where we would avoid windows and hide under our desks. So I was always drawn to stories about that time period. But I was more drawn to the ones about the natural outgrowth of Mutually Assured Destruction—the spies, the silent wars, the complicated plots, the “wilderness of mirrors” that James Angleton described.

The Jin Dynasty was a period like that. There were two enormously powerful empires, arguably the two most powerful in the world at the time, the Jin in the North and the Southern Song in the south, and there was a clear border on the Huai and Yangzi Rivers. They were so powerful that a war between them really would have been mutually assured destruction. So the sparse records we have from the time—more from the Southern Song, a lot less from the Jin—hint at this same existence of plots and double plots and intrigues and spies, that same wilderness of mirrors. So I thought what a great time and place for a murder mystery. With that constant intrigue and tension, nationalism, racial politics, and spying as the backdrop for the investigation. Not the main plot necessarily, but the dark dangerous water through which the detective would swim.

Your title refers most explicitly to Enchenkei Gett, your protagonist and main point-of-view character (although there are interesting resonances to the title that we won’t explore here). Tell us who Gett is and what makes him the ideal focus of your story.

Gett is a eunuch. And when I was designing the plot and the mystery and the solution, I kept coming back to the idea that the main character should be a eunuch. I wasn’t sure why at first, but as I plotted more, I realized it was because the murder at the center of the book is about sex, lust, betrayal, and superstitions and philosophies about sex that Chinese people had (and still have). So I was attracted to the idea of a protagonist who had to navigate those waters blind. He has no intrinsic understanding of lust or sex. No gut feeling for it. He must rely on pure intellect. For him, solving a mystery about sex, being a eunuch is a great disadvantage, or should be, but it would also give him a unique and dispassionate entry into the motivations of all the characters. Eunuchs were relatively rare in the Jin. But I liked the idea so much that I went through with it. And his backstory as a castrated spy who emerged from the dark intrigues of the Jin/Song cold war allowed me an interesting way to insert him into the Jin court—and insert him in a way that emerged naturally from the environment of the world and the time.

The book opens with a murdered concubine, soon identified as Diao Ju. As with all murder mysteries, the fundamental questions of who killed her and why are the central focus of the book. But what can you share about her that sets up your story?

My answer to this question may seem strange to you, and you most likely will disagree or even take offense. But hear me out. And I’m willing to discuss it (and be wrong), as long as someone has read the book. My background, even though I’m an actor, is in Molecular Biology. That is what I studied in university, and I worked in a molecular evolution lab for almost two years as an intern. From an evolutionary standpoint, wars in ancient times, even among prehumans and apes, were always fought by males for access to resources or women. The thing that people may find offensive is my opinion: I think this is still true. And I think it was also true in 1153 when the book takes place. There are layers and layers of complexity accreted over the reasons that countries go to war. But I have lived in many countries. And the number one most common passionate, deep emotion felt by men, always repeated with no exceptions in any country, is: You outsiders cannot have access to our women. For the most part we live in civilized societies, and it doesn’t lead to violence. But the threat of it is always there. Always just under the surface.

Diao Ju was a curious, secretly well-read nineteen-year-old girl from a small place who crossed that line—Chinese to Jurchen, to the emperor—because she wanted to see all that the world had to offer. She saw that the world was a big, fascinating, interesting place. She had read enough about it to know it was bigger than the world she knew. And she was gutsy and ruthless enough to reach out and grab her opportunity to live that bigger, more fascinating life—outside her village, outside her culture, outside her race. And even more rare, she was smart and driven enough to succeed in that larger, more competitive world. That, always and everywhere, is a dangerous choice to make. Because eventually a man pushes back and says, “No, you can’t have our women.”

Gett has to navigate a complex web of relationships linking government bureaus and the officials who run them. Even the documents he studies often don’t mean what they say, and part of the fun is watching him interpret hidden messages. How would you characterize what today we might call his work environment?

Haha. How would I characterize it? I would characterize it as a normal working environment for anyone who has ever worked at or near the top of a zero-sum, high-reward organization. There are only a few spots at the top. And everyone who occupies one of those spots is very very smart and very very ruthless. And only the very smartest and most ruthless can remain in those spots. That is true in palaces, hedge funds, the White House, everywhere there is great power. I suspected it was true from reading a lot of history. But I confirmed it working in show business. At the real top—where I have been a very few times (and both didn’t like and was not sufficiently smart or ruthless to stay in it)—it really is this same kind of zero-sum coded game where even the most basic things like figuring out what people mean, what they don’t mean, what they might potentially mean in the future become crushingly difficult. Wouldn’t want to live there, but I like writing about it. And I think it’s the kind of environment that makes for great stories.

You portray a deep, underlying tension between the Han Chinese and their Jurchen rulers, who consider themselves racially superior. How does that play out in the early stages of this case?

Having lived in two foreign countries for all my adult life, I’m fascinated by how people who look different, speak different languages, and have different cultural assumptions—or (and this is important) assume they do—how these people view each other. Almost invariably it makes life more difficult. It makes every argument, every question, every interaction potentially about the difference and more dangerously about which culture, race, language is dominant. To live in a world like that, to navigate it successfully is hard. But it’s the only world I know. So the simple answer is it makes Gett’s job harder—not only does he have to figure out what happened, he must do it in a way that either manipulates those prejudices if they are helpful or massage his way around them with great difficulty if they impede him.

One of Gett’s frenemies, for lack of a more historically appropriate word, is an Italian known as Sulo. How did he get there, and what does the presence of a Westerner add to the novel?

Haha. Frenemy. That’s really true. He got there because Italians got everywhere. Simple as that. And people in power, especially emperors, love to use outsiders for their security—they’re less likely to betray because they have nowhere to go. They’re hated outsiders. There is no soft landing for them. If he dies, they die. So there is an alignment of incentives. It’s the same principle the Ottomans used when they made janissaries—Christian soldiers captured young and brought up to be the elite bodyguards and fighting units of the Byzantine emperor. It’s the same principle the Chinese examinations were based on—bring talented common people into government who have no support structure, who owe everything to the emperor. So Sulo the Italian can stay in his job because what you incent, you get. The emperor trusts him.

I think Sulo adds three important things to the story.

First, this kind of person has always existed. I’m one of them. There are a lot now, but in the history of the world, if you look closely, there were never none. And that’s something that gets lost in a lot of historical narratives. I wanted to rectify that.

Second, because he’s an outsider, albeit for a different reason, he and Gett can be frenemies. Because ultimately everybody needs a friend. For a story to be interesting, your characters can’t trust everyone, but they also can’t trust no one. That’s boring. There must be people who sit on the edge. Characters with whom the interactions, plans, confidences are necessary, sometimes both practically and emotionally, but risky.

Third, if this ever gets adapted into a movie, I know who they’re casting to play Sulo. I’m not so stupid as to not give myself a character in the adaptation of my own book.

Are you planning to write another novel? If so, what can you tell us about it?

Yes, I am. I don’t want to say too much more. But Gett has been exiled far into the north where a huge battle between the Jin and the Mongols occurs. A hundred thousand soldiers are slaughtered in a day … but one of them is murdered.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Jonathan Kos-Read grew up in Los Angeles. He studied acting in high school, then molecular biology in university. For the last twenty-five years, he has worked in the Chinese entertainment industry in Beijing. He now lives in Barcelona with his wife and two daughters. The Eunuch is his first novel.

Images: Map of Jin/Song China © Yu Ninjie; Jin (Jurchen) Dynasty jade hair ornament in the Shanghai Museum © Rolfmüller, both CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

June 18, 2021

Interview with A. M. Linden

As someone who receives a great many pitches for recently released and forthcoming historical novels, I am often struck by an odd sense of disconnect. For reasons that I’m sure have more to do with marketing than editorial decisions, certain historical periods get far more than their share of attention—World War II and the early Tudors, I’m looking at you—and other times and places, equally filled with drama but less familiar, are considered not to have even the potential for mass appeal.

There must be a logic to this style of decision making, because the favored settings seem to sell lots of books. But as a reader, I much prefer new and less well-traveled paths that will take me to places I have never visited or know little about. So I was delighted to receive A. M. Linden’s The Oath, first of her Druid Chronicles, which takes us back to Britain on the brink of Christianization and the transfer of power from Celts to Anglo-Saxons. Read on to find out more.

You have such an interesting history. How did writing a fiction series get into the mix?

I began the story that evolved into the Druid Chronicles as a way to balance the formal writing I did at work with something that was just for fun. Once I’d come up with my characters and needed to flesh them out, however, I fell back on the adage “write about what you know.” It is, therefore, not an accident that two of the major characters are the medieval equivalent of health-care professionals. More seriously—and I say this from my heart—there is a reason that the heroes and heroines of this series make great sacrifices and fight all odds for the sake of the story’s children, and that is because of the privilege I’ve had to work with families of children with special needs and so have seen firsthand what real heroism is. Returning to your question, I guess I just took a mix of the good, the bad, and the funny of what I’ve seen around me, used it to make up my characters, and set them loose in Anglo-Saxon England.

And what made you want to write about eighth-century Saxons and Celts, including Druids, in particular?

The early medieval period is “long ago and far away,” and yet its mythology is so much a part of our literature that the era has always had, at least for me, a familiar feel. It was those two traits that made eighth-century Britain such a compelling setting when I began writing this series. As for Druids, again it was mythology—in this case conjuring images of nature-worshipping wise men and women—that led me to make them the driving force in a story about the struggle between Christian monotheism and pre-Christian polytheism.

The novel opens with a history of Theobold and his reign in the fictional realm of Derthwald. It sets the stage for what’s to come (and is interesting in its own right), but why start there?

While The Oath and the subsequent books in the series are set in fictional locations and populated with imaginary characters, the Druid Chronicles is intended to be historical in the sense that it is, at least in part, an examination of the interplay between sociopolitical events and its protagonists’ lives. In addition to providing the story’s setting and explaining why this particular kingdom doesn’t show up in the actual historical record, The Oath’s prologue outlines Theobold’s rise from warlord to king and introduces his power-hungry nephew, Gilberth. What’s most important, however, is that it ends at the pivotal juncture between the kingdom’s history and the story’s current events—the aftermath of the battle Theobold waged against a war band of pagan Celts led by Rhedwyn, a charismatic Druid priest who is, among other things, the biological father of Caelym, the series’ main protagonist. This is the point at which the lives of the story’s central characters first intersect. Following that battle, in which Rhedwyn and most of his followers were slaughtered, Annwr, the sister of the Druids’ chief priestess, was captured by Theobold’s warriors, then sold as a slave, while Caelym was left to fill Rhedwyn’s position and will eventually be sent to rescue Annwr.

The next person we meet is Caelym, who might be considered the central character of this book, since the oath is his. Tell us a bit about him and where he is in chapter 1.

At the opening of The Oath, Caelym, a young Druid priest, has just reached the outer walls of the Abbey of Saint Edeth the Enduring, a convent in the northeastern corner of the Kingdom of Derthwald. Caelym is both extremely gifted and extraordinarily handsome—traits that have combined to make him more than a little conceited, and he is prone to show off when the opportunity arises. That said, he is absolutely sincere in his religious beliefs and is prepared to face any hardship to obey the dictates of his shrine’s chief priestess. With only an ambiguous prophecy and a map drawn from legends, Caelym must find Annwr. He has set out on this quest believing the intense Druidic training that he’s undergone has prepared him for the dangers he will face but will need to overcome his pride and accept help from unlikely sources if he is going to succeed.

Caelym is searching for Annwr, whom he imagines as young and beautiful. He’s in for a bit of a surprise, but how did Annwr come to be missing and why is he searching for her?

In the aftermath of the battle between Theobold’s army and Rhedwyn’s war band, Annwr and two other priestesses were sent out of their hidden sanctuary to gather precious herbs for Rhedwyn’s funeral bier. When the three young women were discovered by a band of Theobold’s warriors, Annwr was captured, carried off, and sold to become Aleswina’s nursemaid. The other priestesses were drowned in a river trying to escape, and because a shawl that belonged to Annwr was found with their bodies, it was believed that she had drowned as well. Fifteen years later, their oracle tells the cult’s chief priestess, Feywn, he has had a vision that Annwr is alive and being held prisoner by the Saxons. Hearing this, Feywn orders Caelym to find Annwr and rescue her.

Annwr, also known as Anna, lives near the Abbey of St. Edeth the Enduring, which is the home of your third major character, Aleswina. What is her story, including the relationship between her and Annwr?

The daughter of King Theobold and Queen Alswanda, Aleswina was four years old when her parents died within a day of each other—Alswanda allegedly in childbirth and Theobold, overcome with grief, by either jumping or falling off a cliff. Her cousin, Gilberth, who assumed the throne of Derthwald on Theobold’s death, discharged all his uncle’s guards and servants, including the nursemaid who’d attended Aleswina since her birth. That nursemaid, a Saxon, was replaced by the newly captured Annwr. If Aleswina had been old enough to bear children when Gilberth came to power, he would have married her to cement his hegemony over her mother’s kingdom. As it was, he kept his little cousin confined to her nursery, where she lived in isolation with Annwr for the next seven years. With only each other for company—and both left deeply traumatized by the events that brought them together—Annwr came to love Aleswina as a daughter, while Aleswina was desperately attached to Annwr from the first. When Aleswina is sent to a cloistered convent at the age of thirteen, she takes Annwr with her and the two manage by a combination of stealth and exploitation of Aleswina’s royal status to meet together in the convent’s garden. Now nineteen, Aleswina is still a novice, and she is running out of excuses to avoid taking her final vows, a change in status that would mean she could no longer keep her beloved servant in a cottage on the abbey grounds.

A big part of the background to this novel is cultural conflict between Britons (that is, Celts) and Saxons, exemplified by a struggle between the ancient pagan religion of the Druids and Christianity. What do readers need to know about this issue to understand the novel?

The conversion of the indigenous Celtic population of the British Isles to Christianity took place during the time of the Roman occupation, and while there were presumably holdouts, it was essentially complete prior to withdrawal of the Roman forces at the end of the fourth century. Conversion of the Anglo-Saxons occurred at different times and under different circumstances in the various kingdoms that were established in their takeover of the area we now know as England, but for all intents and purposes this second wave of conversion was complete by the end of the sixth century. With the male Saxon warrior class being the dominant political power and a patriarchal form of Christianity ascendant, the underlying questions in The Oath are whether a tiny, demonized minority who believe their chief priestess is the embodiment of the supreme Mother Goddess can escape persecution—and what will become of Aleswina, who is caught between incompatible cultures.

Are you already working on the second novel in the series? What can you tell us about it?

Book 2, The Valley, begins a generation earlier than the other novels in the series and recounts the events that set the main story in motion. Llwddawanden, the valley of the book’s title, is a hidden sanctuary where the remnants of a once powerful Druid cult have carried on their ancient ritual practices supported by a small but faithful following of servants, craftsmen, and laborers. Narrated from the viewpoint of an elderly priest who’d been Caelym’s teacher and mentor during his formative years, it interweaves the story of our hero’s growing up with mounting conflicts within the shrine’s highest ranks. Besides Herrwn and Caelym, central characters in The Valley include Ossiam, an enigmatic oracle; Olyrrwd, a cynical physician; Feywn, the shrine’s beautiful supreme priestess; Arianna, Feywn’s rebellious and headstrong daughter; Feywn’s sister, Annwr; and Annwr’s daughter Cyri. The Valley is completed and is scheduled for publication by She Writes Press on June 28, 2022.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Thank you! These have been the questions I’d have hoped a friend who liked the book would ask.

A. M. Linden is the author of The Druid Chronicles, a five-volume series that began as a somewhat whimsical decision to write something for fun but became a lengthy journey that included creative writing classes, research into early British history, and travel to England, Scotland, and Wales. Additional information about the books is available at https://www.druidchronicles788ad.com.

June 11, 2021

Merchants Set Sail

As I’ve mentioned more than once, in addition to my Legends and Songs of Steppe & Forest series, for the last two years I’ve been co-writing The Merchants’ Tale (originally titled These Barbarous Coasts) with fellow historical novelist P.K. Adams. In that vastly different world that preceded the coronavirus pandemic, we met in person, but we communicate mostly via e-mail, Facebook Messenger, and video calls. Through it all, we have established a good working relationship, and the pages flew off our computer screens even before we settled in to polish each chapter until it shone. We revised the book twice, then sent it out to half a dozen willing volunteers and revised it again based on their comments. This week marks a milestone: with that fourth revision essentially complete, we started querying agents. And that in turn sparked some thoughts on the process of finding representation that I thought might be worth sharing here.

This will be my fourth agent search. The first, conducted under conditions that now appear almost medieval, did land me an agent, but in the end he couldn’t sell the book. It wasn’t his fault: one publishing company held the rights to that type of story, and its acquisitions department resisted his efforts to persuade them to take it on. It was the 1990s, when these negotiations still took place through the mail, with printed samples and self-addressed envelopes. Before getting the positive response from the agent who took me on, I accumulated a folder full of rejections, everything from handwritten notes to the already ubiquitous form letters. A few of the form letters were personalized with suggestions for improvement; most were generic. After all, when you want to end a conversation, why risk getting the other person upset?

By the time my next novel was ready (around 2008), my agent had moved away from fiction, so I needed to find someone else. I’d learned a lot about writing, and the second search was both less restrictive in terms of publishing venues and productive of more personalized letters and requests for the full manuscript. In the end, though, I abandoned the search. I could tell from the responses I was receiving that the book was still not ready, even though I had rewritten it several times and even worked with a book doctor, who taught me a great deal about story structure that I have since put to good use. But at the time, I couldn’t figure out what else I might do that would fix it. I had to complete my next novel before I finally saw the solution that had escaped me for years.

By 2008, the technology of querying had already changed: Word attachments replaced printed copies, and communications were via e-mail. But it was still common to get e-mail responses from agents, who were not yet totally overwhelmed by the volume of submissions from hungry authors. When I set out to query The Golden Lynx in January 2012, I found myself in very different circumstances. Website forms and auto-responses (or no responses) had replaced one-on-one e-mail exchanges for everyone in the first stage of querying, a desperate attempt by agents to fend off a deluge of messages.

Again I moved higher up the query chain, receiving detailed rejections listing potential problems with marketability or objections to specific plot points among the requests for full samples. Some agents swore they would take on the project if they knew an editor who would consider a book set in medieval Russia. (I still don’t understand why Ivan the Terrible isn’t dramatic enough to sell a novel, so perhaps that was just a nicer than average brush-off.) While I was still in the midst of querying, though, my writers’ group decided to launch Five Directions Press as an experiment, with The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel—the rewritten object of the 2008 search—as its inaugural publication. So I halted the hunt for an agent and added The Golden Lynx to our originally small list of titles.

Again I moved higher up the query chain, receiving detailed rejections listing potential problems with marketability or objections to specific plot points among the requests for full samples. Some agents swore they would take on the project if they knew an editor who would consider a book set in medieval Russia. (I still don’t understand why Ivan the Terrible isn’t dramatic enough to sell a novel, so perhaps that was just a nicer than average brush-off.) While I was still in the midst of querying, though, my writers’ group decided to launch Five Directions Press as an experiment, with The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel—the rewritten object of the 2008 search—as its inaugural publication. So I halted the hunt for an agent and added The Golden Lynx to our originally small list of titles. Enter 2021, and here we go again. Will it work this time? Hard to tell. On the plus side, I’ve written a lot of novels since 2012, and based on the reviews I get, I have honed my craft enough to be taken seriously. I revised my earlier books, which I can recognize as half-baked in a way I couldn’t twenty years ago, and turned them into something that readers love. I’ve acquired a group of loyal fans, a monthly blog audience of about 10,000 views a month, a podcast with more than 100 episodes, and a co-writer who has serious sales of her self-published books. And with The Merchants’ Tale, we have two built-in audiences: people who can’t get enough of the Tudors and those fascinated by the Romanovs, whose ancestors populate this series alongside our fictional characters. Marketed the right way, this proposal could make a lot of money for someone, and ultimately that’s what publishers want.

On the minus side, the situation with queries doesn’t seem to have improved since 2012. If anything, the pandemic has made things worse: millions of would-be writers in lock-down seizing their chance to produce the Great American/British/Russian/you-name-it Novel. Many US agents are already so overwhelmed they have closed their electronic doors to new submissions; their counterparts in the UK and Europe are beginning to follow suit.

So wish us luck! In the long run, The Merchants’ Tale will find a safe harbor, but let’s hope it doesn’t get battered by storms along the way.

Images: Alexander Litovchenko, Ivan the Terrible Shows His Treasures to the English Envoy Jerome Horsey (1875); Anthony Jenkinson, Map of Russia and Tartary (1562), both public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

June 4, 2021

Sherlock Holmes Goes Gothic

Long ago—or so it seems, but everything before the pandemic now has the aura of a different universe, one where we routinely gathered in the streets without masks and hugged neighbors and friends in greeting—I walked into a just-opened Borders bookstore (remember those?) and stumbled across Laurie R. King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice.

Long ago—or so it seems, but everything before the pandemic now has the aura of a different universe, one where we routinely gathered in the streets without masks and hugged neighbors and friends in greeting—I walked into a just-opened Borders bookstore (remember those?) and stumbled across Laurie R. King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice.The premise—in which a bored and lonely fifteen-year-old girl encounters the Great Detective during his retirement and impresses him with her reasoning skills to the point where he takes her on as his apprentice—hooked me from the get-go. By the time I discovered the series, King had already reached book 7 (The Game). Once I finished the first, I bought the rest, then settled in for the long haul, gobbling up each new installment as it hit the shelves.

When I got the chance to host New Books in Historical Fiction, Laurie R. King was on my short list of interview guests (by then, the series had reached no. 12, Garment of Shadows). You can hear our conversation on the New Books Network, although the interview gods decided that San Francisco was in some weird foreign territory, so the sound is not what it should be. In it, we also discuss her take on Sherlock Holmes and earlier books in the series, including the hilarious but underappreciated Pirate King (no. 11). And since I haven’t missed a single book in the series, when I saw no. 17 show up on NetGalley, it took about two seconds for me to request an advance copy.

I assume that most people know—but here’s the deal, just in case—that publishers use NetGalley to provide free copies of new books to readers in return for honest feedback and early reviews. Hence this overview of Castle Shade , which I will also post on GoodReads and NetGalley itself.

In some ways, Castle Shade reminds me of Pirate King—which, like many other fans, I underestimated at first but warmed up to on a second reading. Shade is billed as King’s stab at a Gothic novel, a claim borne out by the setting: a recently decrepit castle atop a Transylvanian mountain, next to a village where rumors of vampires are circulating. But beneath the details of castle life and local folklore lurks a classic King mystery, one that Russell and Holmes alternately cooperate and compete to resolve.

In brief, the setup is as follows. Holmes and Russell have just left Monaco, the site of Riviera Gold (no. 16), and are on a train heading east, except that when the book opens, the train is not heading anywhere; it’s stuck in a station. Russell, being disinclined to spend weeks of her young life traveling from Italy to Romania, solicits help from the conductor. Soon she and Holmes are on their way back to Vienna, before finding more reliable transportation southeast. The summons to Castle Bran, the Transylvanian mountain fortress mentioned above, comes from Queen Marie of Romania, one of the many descendants of Britain’s Queen Victoria on one side and of Emperor Alexander II of Russia on the other.

Queen Marie has received a threat aimed at her teenage daughter, and that is only the most worrying of the troubling incidents that afflict Castle Bran whenever the queen spends her time there. Marie enlists the help of Holmes, skeptical but unwilling to refuse royalty, who in turn recruits Russell to, as he puts it, “be my inside informant into the mysterious realm of the adolescent female.” It takes some persuasion, but in the end Russell agrees there might be something worth investigating in the reports of walking undead and countesses who bathe themselves in the blood of their victims. The chase is on—or should we say, given the context, the game is afoot?

One element sets this book aside from its predecessors and imparts some of the improvisational quality of Pirate King: every so often, King presents a character’s backstory in the style of a fairy tale, in a chapter of its own. I saw this approach as a creative and helpful way to handle the historical novelist’s perennial problem of how to get across essential context without indulging in the dreaded “information dump.” Other readers may feel differently, but it does fit the generally otherworldly atmosphere of the book.

The one area where I would like to see more development—not just in this novel but in the series as a whole—is the relationship between Russell and Holmes. They’ve been together for ten years and married for five, yet they still come across more as business partners than as husband and wife. I don’t expect (or, frankly, want) intense romance, which would fit neither the characters nor the genre, but every time I start one of these books, I hope for more exploration of the couple’s feelings than the occasional statement that one of them cares for or experiences anxiety about or misses the other. I could say all those things about my cat—and at times do—but that doesn’t mean I feel the same way about her as I do about my husband.

So far, only A Murderous Regiment of Women, Locked Rooms, and Garment of Shadows have taken steps in that direction. But maybe we’ll get there next time. And if that’s the reason why I withhold the fifth star, it’s also just one element of a series that has brought me great enjoyment for almost two decades. I’m glad I read Castle Shade. I thank the publisher for the opportunity. And when no. 18 rolls around, you can bet I’ll be first in line.

In an amusing side note, Castle Bran has been in the news lately because, if you happen to live in Romania, you can get a Covid vaccine along with your tour of the castle. Vlad the Impaler as Vlad the Medic? Or should we say that Count Dracula's fanged teeth have acquired a new, life-giving purpose?

Images: photograph of Castle Bran © Pmatlock, CC BY-SA 3.0; Vlad the Impaler (1560) public domain; both via Wikimedia Commons.

May 28, 2021

The Price of Friendship

Whether we like it or not, each of us lives with the knowledge that someday we will not be here. After fifteen months of pandemic-imposed lockdowns and surging death rates, now at least temporarily mitigated in the United States and much of Europe by vaccinations, that message has a particular relevance.

Whether we like it or not, each of us lives with the knowledge that someday we will not be here. After fifteen months of pandemic-imposed lockdowns and surging death rates, now at least temporarily mitigated in the United States and much of Europe by vaccinations, that message has a particular relevance.Even those of us who are not religious in the traditional sense comfort ourselves with the belief that our names will live on in the memories of families and friends. But suppose your friends—perhaps with the best of intentions, but possibly not—construct a story of your life and your untimely death that at best gives undue weight to your failings and at worst wholly ignores your strengths?

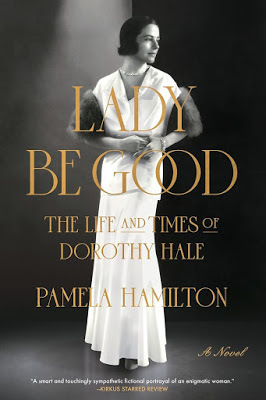

That question drives Lady Be Good, Pamela Hamilton’s debut novel about the dancer, actress, artist, and socialite Dorothy Hale. To find out more about Hale, her life, and why Hamilton suspects the entire story has not yet been told, read on, then listen to my latest interview on New Books in Historical Fiction. By the time you’re done, you may want to quiz a few of those dear friends and family members about just what they’ll have to say when something happens to you.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The name of Dorothy Hale is not well known these days. In the 1920s, she enjoyed a career on Broadway as a dancer, including in a leading role with Fred Astaire. When an accidental injury ended that career, she auditioned, successfully, for the filmmaker Samuel Goldwyn and landed a part opposite Ronald Coleman, who would later star in Lost Horizon. But Dorothy’s film career did not take off, and she moved into art, writing, and museum work in support of her second husband, Gardner Hale, a well-known fresco painter and portraitist, until his tragic death in 1931.

Dorothy survived the stock-market crash of 1929 with her wealth intact and remained a light of New York society into the 1930s. Her closest friend—Clare Boothe, who married Henry Luce in 1935—branched out from an active career in magazine publishing, including a stint as managing editor of Vanity Fair, to write and produce a Broadway play titled The Women. The play lampooned members of their social circle, evoking both amusement and outrage. Dorothy Hale then starred in Boothe Luce’s next play, Abide with Me. When Hale fell to her death from the window of her apartment building in October 1938, Boothe Luce commissioned a commemorative painting from their mutual friend Frida Kahlo.

This painting, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1939), was the spark that lit the imagination of Pamela Hamilton, a long-time producer for NBC News. She began to research Hale’s life and death and uncovered the kind of anomalies that delight both fiction and nonfiction writers. For reasons explained in this interview, Hamilton decided to turn her findings and her speculations about their meaning into a novel, and Lady Be Good: The Life and Times of Dorothy Hale (Köehler Books, 2021) is the result. Against the backdrop of New York high society, the Algonquin Set, the art world, and politics under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, this novel paints a picture of a vivacious, determined woman and offers an alternative vision of her final hours.

May 21, 2021

Advice to the Lovelorn

As I mentioned about a month ago, my friend and fellow Five Directions Press writer Claudia H. Long has started an advice column for characters on her blog. Many of the characters are her own, but she accepts questions from other authors’ troubled creations, which she answers in the persona of Madam Mariana, a time-traveling and super-savvy source of well-considered and often-humorous counsel.

As I mentioned about a month ago, my friend and fellow Five Directions Press writer Claudia H. Long has started an advice column for characters on her blog. Many of the characters are her own, but she accepts questions from other authors’ troubled creations, which she answers in the persona of Madam Mariana, a time-traveling and super-savvy source of well-considered and often-humorous counsel.Yesterday Madam Mariana fielded a plea from Darya Petrovna Sheremeteva, the heroine of Song of the Sisters, my own latest novel—released this past January and woefully under-promoted due to a family medical crisis (not Covid!), since happily resolved, that struck at just the wrong moment.

Let's start with a word about Darya: she is a twenty-five-year-old Russian noblewoman, the younger of two surviving children, each of whom has the same father but a different mother. She has spent the seven years before the story begins nursing their elderly father, while her older sister, Solomonida, maintained the family’s connections with the outside world. This experience has heightened Darya’s religious sensibility while leaving her somewhat naive about society, especially men, and its expectations. By temperament, too, she is naturally inclined to do what others expect of her, although in reality she’s much less deferential than she appears at first glance. She dislikes confrontation, but she knows how to exert authority, because she has managed her family’s household since the age of fourteen. Although her older sister returned to the house when Darya was sixteen, Solomonida’s responsibilities at court meant that Darya bore primary responsibility for keeping the servants in line.

Darya has never known her own mother, who died giving birth to her, and her stepmother (her father’s third wife) died when Darya was fourteen. As a result, Solomonida, six years older and widowed, represents Darya’s only source of female comfort and advice. When their obnoxious cousin Igor shows up, waves a will that gives him control of the estate, and announces his plans to advance his career by marrying Darya off to a man of his choosing (while stashing Solomonida in a convent), the battle lines are drawn and the two sisters begin to use every weapon they can muster to thwart Igor’s schemes.

Alas, the position of women, even aristocratic women, in sixteenth-century Russia places severe limits on the sisters’ ability to control their own fate. The son of their father’s best friend arrives with a parallel claim to the estate, but his help does not come without cost. Soon he has disappeared, leaving Cousin Igor more determined than before to marry Darya off before she escapes his clutches altogether. Hence her plea to Madam Mariana, reproduced here.

Moscow, September 7051 [1543]

Deeply respected Madam Mariana!

I am at my wit’s end. At twenty-five years old, beyond marriageable age, I was reunited with the love of my childhood, Nikita, but on the very afternoon when he declared his desire to wed me—as my father intended!—the government called him back into service.

I don’t know when I will see him again, but it hardly matters. The next day, I learned from my neighbor that he has been promised to another for years. My heart is broken. How can he dishonor me so?

My wicked cousin, who controls our ancestral estate, insists on finding me another spouse. But I know that no crony of my cousin’s will do for me. I tried to take monastic vows, but the abbess turned down my request and advised me to practice obedience by submitting my will to my cousin’s. When he seeks only a powerful patron at court? What kind of spiritual exercise is that?

Now I am stuck dodging potential husbands, each less suitable than the one before. My cousin swears he will force me to become his bride if one more candidate withdraws his offer. Other than throwing myself in the Moscow River, which would be a terrible sin, what can you recommend?

Yours in humility and hope,

Darya Petrovna Sheremeteva

P.S. I have already deployed several of the more effective methods of discouraging unwanted suitors—or at least their mothers.

And what does Madam Mariana have to say? You can find her answer on Claudia H. Long’s blog, as well as her advice to quite a few other distracted damsels, not to mention a married woman with man trouble and a desolate dog—all tearing their hair out at the hands life has dealt them.

And what does Madam Mariana have to say? You can find her answer on Claudia H. Long’s blog, as well as her advice to quite a few other distracted damsels, not to mention a married woman with man trouble and a desolate dog—all tearing their hair out at the hands life has dealt them.To find out what those “methods of discouraging unwanted suitors” may be, of course, you’ll need to read the book. For buy links, check out its dedicated page on the Five Directions Press website. We’ll have an audio excerpt up there soon, but you can read a print excerpt by clicking the cover.

And of course, you can listen to the free interview on New Books in Historical Fiction, with thanks to G.P. Gottlieb for acting as host. We talk about the second book, Song of the Shaman , as well, while the first book in the series has its own interview.

And one more thing! I just discovered that the New Books in Historical Fiction interviews (and indeed, many New Books Network interviews) are now on Spotify. So just search for the channel you want, and you can listen to the interviews there, too.

Images: Sergei Solomko, The Meeting (1880s); Konstantin Makovsky, The Young Nun (1890s), both public domain via WikiArt.

May 14, 2021

Reawakening Sherlock Holmes

Although I’m no more immune than anyone else to the appeal of Sherlock Holmes as a character in film and on television, I have to admit that I have never quite warmed to the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories. Some of the modern book series based on the great detective and his faithful sidekick, Dr. John Watson, however, have won my heart. In this respect, the situation with Holmes is the opposite of Jane Austen’s novels—another well-trodden fictional pathway where, other than films and TV productions based on the originals, the many spinoffs seldom give Austen’s creations a run for their money (although I have featured a few that stand out).

Although I’m no more immune than anyone else to the appeal of Sherlock Holmes as a character in film and on television, I have to admit that I have never quite warmed to the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories. Some of the modern book series based on the great detective and his faithful sidekick, Dr. John Watson, however, have won my heart. In this respect, the situation with Holmes is the opposite of Jane Austen’s novels—another well-trodden fictional pathway where, other than films and TV productions based on the originals, the many spinoffs seldom give Austen’s creations a run for their money (although I have featured a few that stand out). I have long been a fan of Laurie R. King’s series featuring Mary Russell as Sherlock’s partner and wife, eliminating Watson but retaining Mycroft Holmes as a kind of bête noire for Mary and imparting a new twist to Mrs. Hudson. On that, more next month, when I talk about the latest book in the series, Castle Shade, which I’m reading as an advance copy from NetGalley.

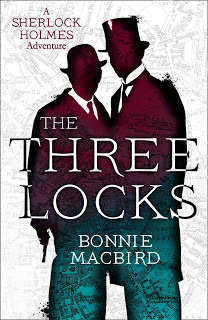

Bonnie MacBird takes a very different approach from King, but she too is now a favorite. As she insists during my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview, her goal is to stay within the bounds established by Conan Doyle while inventing new cases of her own and adapting the series to long-form fiction.

She does an admirable job. In The Three Locks —the only one in the series I’ve read so far—the main characters and their relationship sound and act like the late Victorian males they are, yet we get the occasional glimpse into parts of their pasts and their personalities that Conan Doyle chose not to reveal. These are not the middle-aged and measured gentlemen portrayed by Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce but closer to the Robert Downey Jr./Jude Law version: active and enthusiastic men in their thirties willing to risk life and limb as need be.

The mysteries are twisty and colorful, with complicated plots and satisfying solutions. Each one addresses a deeper theme: the benefits and costs of the artistic temperament; the power of spirits, whether material (i.e., alcoholic) or immaterial (ghosts of the past); the consequences of moral compromise; the pressures of illicit love. And MacBird talks easily and well about everything from her writing choices to her research. So give her interview a listen, then dive into one of her books. It’s all tremendous fun, and even in the midst of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, here’s a visit you can enjoy—and to 221B Baker Street, at that!

You can also find a transcript of the interview on LitHub Radio.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Sherlock Holmes is one of the rare literary characters who has achieved a kind of cultural immortality. As Bonnie MacBird notes in this interview, display an image of a deerstalker hat and a pipe almost anywhere in the world, and people can identify the great detective without a second thought. So is it any wonder that an entire industry is devoted to expanding the Conan Doyle canon?

Not all these attempts succeed, but MacBird’s novels are a gem. The Three Locks (Collins Crime Club, 2021), fourth in her series and set in 1887, opens with a mysterious package delivered to Dr. John Watson. London is in the midst of a heat wave, Watson’s friend Holmes has withdrawn in one of his periodic funks, and the package offers the rather disgruntled doctor a welcome distraction. Its appeal increases when Watson discovers that it contains an engraved silver box sent by his father’s half-sister, an aunt he did not know he had, and represents his mother’s last gift to him. But as he struggles to discover the key to unlocking the box, Holmes appears, warning of danger.

Watson’s drive to prove Holmes wrong (he rejects his friend’s suggestion that the aunt’s letter may be a forgery and the lock designed to cause harm) must compete with the demands of two other cases. The wife of an escape artist requests help in protecting her husband from an angry rival, her former lover—a case that becomes more urgent when the escape artist’s most dramatic stunt goes awry, causing his death. Then the rebellious daughter of a Cambridge don goes missing, to the great distress of the local deacon who has unwisely fallen in love with her.

Holmes initially dismisses the second case, although he takes a personal interest in the first. But when a doll made to resemble the young woman is found in the Jesus Lock on the Cam River, with a broken arm and an illegible threat written in purple ink on its cloth chest, the hunt is on, for both the don’s daughter and the person who wishes her harm. In time, it becomes clear that the two cases are connected—and that Holmes must defeat not only a cunning murderer but the over-zealous local police.

Image: Sidney Paget, “Sherlock Holmes,” for The Strand (1891), public domain via Wikimedia Commons.New Books in Historical Fiction