C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 11

April 22, 2022

On the High Seas

I’ve always considered Death on the Nile—currently a blockbuster movie, following on the recent success of Murder on the Orient Express—one of my favorite Agatha Christie novels. Both stories are versions of the closed-room mystery, where the number of suspects is constrained by circumstances (a boat on the river, a train trapped in a blizzard) and tension rises as it becomes increasingly clear that anyone may be guilty and the innocent cannot escape from the killer.

I’ve always considered Death on the Nile—currently a blockbuster movie, following on the recent success of Murder on the Orient Express—one of my favorite Agatha Christie novels. Both stories are versions of the closed-room mystery, where the number of suspects is constrained by circumstances (a boat on the river, a train trapped in a blizzard) and tension rises as it becomes increasingly clear that anyone may be guilty and the innocent cannot escape from the killer.

As Erica Ruth Neubauer notes in my latest New Books interview, all three of her Jane Wunderley novels use this format to a degree, but none more so than Death on the Atlantic, where Jane and her love interest, Redvers, embark on a trans-Atlantic cruise. Their task is to unmask a spy, who may be either passenger or crew, but Jane soon becomes involved in helping a fellow passenger who is being, in modern parlance, “gaslighted” into believing that her missing husband never existed. Jane knows that’s not true—she saw them together—but given the fellow passenger’s reputation for elaborate pranks, what actually happened remains far from clear. What does soon become clear to Jane, though, is that even on a large boat, making enemies on a ship when there’s a killer aboard and no way off except over the side into the freezing ocean is not good for one’s health.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

From the years leading up to and into the French Revolution, we move forward in time to 1926. Jane Wunderly, who left her home in the United States earlier in the year on a journey that took her first to Cairo, then to the English countryside, is heading back home in the company of Redvers, the enigmatic businessman she first met in Egypt. In fact, she is posing as Redvers’ wife—or should we say, he is posing as her husband, because they go by the name of Mr. and Mrs Wunderly—even though Jane has decidedly ambivalent views of matrimony, the result of bad experiences in her past.

Despite her doubts, Jane enjoys being included in Redvers’ current mission: to identify a spy reported to be traveling on the Olympic, the magnificent sister ship of the Titanic. The settings are luxurious, the gig comes with magnificent clothes supplied by Redvers’ employer, and the biggest threat to Jane’s peace at first appears to be Miss Eloise Baumann, a loudmouthed New Yorker who dominates every conversation. But the ship has barely left port when Jane encounters an heiress who claims to have lost her husband—on board the Olympic, in the middle of the Atlantic. No one else wants to help, and even Redvers tells Jane to keep out of it and concentrate on the spy. But Jane is determined to solve both mysteries, and soon she has to wonder whether every trip to the deck will end with someone pitching her overboard

Erica Ruth Neubauer mixes a gift for creating complex and engaging mysteries with a delightful sense of humor. To avoid spoilers, I recommend starting with Murder at the Mena House and reading forward, but all three of these novels are well worth your time.

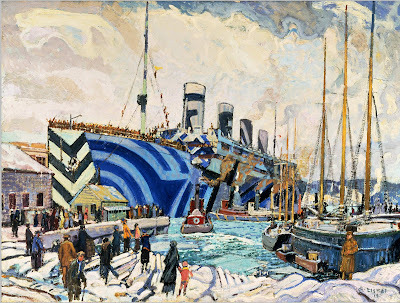

Painting of the HMS Olympic by Arthur Lismer, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

April 15, 2022

Interview with Jody Hadlock

It was tough for women in nineteenth-century America—and, indeed, throughout most of history. A woman who gave into a man, even a man who promised to marry her, and ended up pregnant soon discovered that all the burden and the shame fell on her. He could, if he chose, denounce her as loose and walk away scot-free.

It was tough for women in nineteenth-century America—and, indeed, throughout most of history. A woman who gave into a man, even a man who promised to marry her, and ended up pregnant soon discovered that all the burden and the shame fell on her. He could, if he chose, denounce her as loose and walk away scot-free.Such is the situation that Annie—the heroine of Jody Hadlock’s debut novel, The Lives of Diamond Bessie —finds herself in. When we first meet her, she has been renamed Elisabeth and confined to a convent near Buffalo, NY. She soon gives birth to a daughter, whom the nuns wrest from her arms before she has a chance to protest, and when she escapes, intending to make enough money to reclaim her baby, she discovers that only the “world’s oldest profession” will allow her to support herself. The child’s father denies all responsibility. Adapting her convent name, Annie establishes a new life for herself as Bessie. But before long, she learns that her daughter has died.

After a long period of mourning, Bessie leaves New York for Chicago, where she enters a high-class brothel. She’s doing very well for herself when a chance encounter with a handsome grifter sends her off on a different trajectory.

It would be unfair to go farther into the plot than this. Suffice it to say that Bessie’s complex story is well told, even riveting. At times I wanted to shake her for her willful pursuit of a love that seemed too good to be true, but her goals were crystal clear, and I never stopped pulling for her to attain them.

The Lives of Diamond Bessie is your first novel. What made you decide to write fiction?

I’d always wanted to write a novel, but I didn’t know what I wanted to write until I learned about Bessie’s story. I also love history, going back as far as junior high when I was a member of the Junior Historians of Texas, and I read a lot of historical fiction, so it’s no surprise, to me that my first novel is historical.

And what drew you to this particular story?

I learned of Diamond Bessie during a visit to Jefferson, Texas, which is three hours east of Dallas. I’d never heard of Jefferson, even though I grew up in a Dallas suburb. I was amazed to learn that it was a booming inland riverport in the mid-1800s. At Jefferson’s historical museum there was a full-page newspaper article about Bessie and Abe Rothschild on display. It was published in a Dallas newspaper in the 1930s. I thought, “Why in the world was this paper interested in something that happened nearly sixty years earlier in a tiny town a few hours away?” And I had another thought, but I don’t want to give away the plot for those not familiar with the story. I was immediately hooked and knew I had found what I wanted to write.

When we first meet Bessie, whose birth name is Annie, she’s living in Buffalo, New York, with a group of nuns who call her Elisabeth. Explain, please, what she’s doing there and what her life with the nuns is like.

In the nineteenth, and for some of the twentieth, century, if you were a young woman and had sex outside of marriage or were even just considered “at risk” of doing so—or God forbid, you got pregnant out of wedlock—you were often sent to a place for “fallen” or “wayward” women. One of these was the Sisters of Good Shepherd, founded by nuns in France and brought to the United States in the mid-1800s.

I found a few memoirs written by women who had lived in these convents, which informed the first few chapters of my novel. Young women, and even young girls, who were sent to these places were told they were starting new lives. They were given new names and were forbidden from talking about their pasts, including their families. They were supposed to have a fresh start. Unfortunately, there are many accounts of abuse in these places, which had incredibly strict rules.

Not much is known about Bessie leading up to when she became a prostitute, so the first part of my novel is more fictional than fact. My main character was known as Bessie in real life as a prostitute. Most demi-mondaines used a stage name. For her fictional time at the convent, I decided on the name Elisabeth, one of the patron saints of pregnancy, and I used the French spelling of the name because the convent in Buffalo was founded by French nuns. Bessie is also a nickname for Elizabeth.

Bessie escapes early on, intending to return home but ending up in Watertown, New York. What is her situation at this point, and how does it determine her future path in life?

Bessie knew she couldn’t return home to Canton in far upstate New York and she also couldn’t stay in Buffalo because, if found, she would have been taken back to the convent. In real life, Bessie ended up in Watertown. I portray her as arriving with nothing, not knowing anyone, and how the societal constraints at the time affected the choices she ends up making.

After a while, Bessie leaves New York for Chicago, where she eventually runs into Abe Rothschild. Tell us about him.

Abe, the antagonist of the story, was a real person—and a cad. He was the eldest son of a wealthy businessman in Cincinnati and worked as a traveling salesman, known as a “drummer” back then because they drummed up business. Unfortunately, Abe liked gambling more than work. Bessie had to have seen some good in him in the beginning, so I had to write him as three-dimensional, so to speak, and not just as being a horrible person. It was difficult because I don’t like him!

Without giving away spoilers, can you hint at why your title is The Lives of Diamond Bessie, not The Life of Diamond Bessie? And why did you decide to add this supernatural dimension to your book?

The title came from a fellow writer at the Aspen Words summer conference. There were six of us in one of the workshops, critiquing each other’s full manuscripts. The title of my novel at the time was Land of Lost Souls, which I liked. The workshop leader, the late Vanity Fair and Simon & Schuster editor George Hodgman, suggested that it be just Diamond Bessie. That’s when a fellow writer suggested The Lives of Diamond Bessie because of the way the story is structured. As soon as he said it, I knew it was the perfect title. And luckily my publisher agreed!

My novel has a supernatural element because I wanted the story to continue after the “big event.” I didn’t want it to end on that tragic note and because so much happens afterwards. I decided this was the best way to tell the whole story.

This novel just came out. Do you already have another in the works?

Yes, it’s a story I learned of while researching Diamond Bessie. I don’t want to give too much away, but it will be set in the United States and Russia from the late 1850s to the 1880s and will probably feature two women as the main characters. I was planning to visit Russia next year (in 2023), but with the situation in Ukraine now, I don’t know if I’ll be able to make it there. If needed, hopefully I’ll be able to finish my research remotely. I also have another idea for a novel, which would also be set in the 1800s, but it’s very much in the embryonic stage.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Thank you for including me!

After studying journalism at Texas A&M University, Jody Hadlock was a television news reporter and anchor in Bryan-College Station, Texas; Charleston, South Carolina; and San Antonio, Texas. The Lives of Diamond Bessie is her first novel. Find out more about her and her writing at http://www.jodyhadlock.com. She can also be found on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/jodyhadlock.

Map of Jefferson, Texas, in 1872 public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

April 8, 2022

Interview with C.S. Harris

Fans of Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin, will know that the individual tales that form his saga combine complex, fast-paced, often political mysteries with a series of revelations about his family’s history that it would be churlish to reveal in a post like this. All this takes place against the background of the Napoleonic Wars, mostly in Regency-era London with its vast social gap between the aristocratic rich and the starving, crime-ridden poor.

Fans of Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin, will know that the individual tales that form his saga combine complex, fast-paced, often political mysteries with a series of revelations about his family’s history that it would be churlish to reveal in a post like this. All this takes place against the background of the Napoleonic Wars, mostly in Regency-era London with its vast social gap between the aristocratic rich and the starving, crime-ridden poor.In When Blood Lies , the seventeenth installment, Sebastian’s encounter with his own past is particularly poignant. With Napoleon incarcerated on Elba and Europe at peace, Sebastian sees the perfect opportunity to seek out his long-lost mother (this information is itself a bit of a spoiler, but it’s included in the book’s short description), Sophia. So he travels to Paris in the hope of engineering a reconciliation with her or at least obtaining answers to his questions. He has no sooner established her whereabouts, however, than he stumbles over her body on the river bank near the Pont Neuf. She manages to say his name, proving that she recognizes him, then loses consciousness.

Sebastian has Sophia carried back to the home where he’s staying with his wife and children, only to watch his mother die before she can say anything more. In the interim, he discovers that she was murdered. He urges the local police force to find her killer, but with the Bourbons in charge of Paris, the police have little interest in tracking down the murderer of someone they consider a loose woman—and one associated with Napoleon, to boot. So Sebastian and his wife are on their own, determined to solve a murder that the local authorities refuse to acknowledge in a foreign city rife with political tension and rumors of Napoleon’s imminent return.

For reasons outside my control, I ended up reading this series out of order, which I do not recommend. Each book builds on the one before, and you will enjoy them most if you start with What Angels Fear and go from there. But even out of order, this is a remarkable story, not just engaging but engrossing, not to say impossible to put down. The murders themselves tend toward the gruesome (When Blood Lies is an exception in that regard), but you can skip over those parts and focus on the mystery or, if all else fails, Sebastian’s complex and constantly evolving interactions with the members of his immediate family.

Read on to learn more about the series and its main characters from the author herself.

This is Sebastian’s seventeenth adventure, although only four years have passed since we first met him in What Angels Fear. Before we get to him and what we can safely reveal about this story, where does the inspiration for the whole saga come from?

Because my PhD is in 18th- and 19th-century European history, I knew I wanted to set my mystery series in that period. My particular area of expertise—France in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras—struck me as just too depressing. So I thought, why not move across the Channel to Regency England? With Sebastian, I can explore the era’s social tensions, intellectual and creative developments, and political and military developments, but in a setting that isn’t as brutal or emotionally wrenching as, say, Paris in 1793. As for Sebastian’s personal saga, that just came to me over time as I lived with him, his family, and his friends in my head for a few years.

Sebastian himself is the central figure. Talk a little bit, please, about his somewhat unusual abilities and why you decided to assign them to your hero.

When Sebastian was still just an idea in my head, my daughter was a freshman biology student and volunteered to take an extensive DNA test for extra credit. They told her she had something called “Bithil Syndrome” (this came over the phone from an excited seventeen-year-old, so I could have the spelling wrong). It’s characterized by extremely keen hearing and eyesight, the ability to see well in the dark, and quick reflexes—all characteristics I’d noticed in her from the time she was little. So naturally I thought, What a cool syndrome to give a hero. I’ve been accused of making it up, but I didn’t; most people don’t realize there are thousands of rare syndromes that don’t come up in Google. (That daughter, BTW, is now a flight surgeon in the USAF.)

And what can you tell us about Sebastian himself? He’s been through some tumultuous times since that first novel.

When the series begins in early 1811, Sebastian is very damaged by the things he has seen and done in the war. For Sebastian, bringing justice to the victims of murder becomes a path to atonement. But at the same time as he is struggling to come to terms with his past, he must also deal with a series of truly shocking revelations about his mother, the man he thought was his father, and the woman he has long loved. So over the last four years of his life, he’s done a lot of growing and changing. It’s one of the things that helps keep it interesting for me as a writer and—I hope—for my readers.

Anyone who reads the book blurb for When Blood Lies will know that Sebastian is married by now. His wife, the former Hero Jarvis, is an interesting character in her own right. Tell us a bit about her background and her personality.

Anyone who reads the book blurb for When Blood Lies will know that Sebastian is married by now. His wife, the former Hero Jarvis, is an interesting character in her own right. Tell us a bit about her background and her personality.I really love Hero. I suspect in many ways she’s the woman I would like to be. She’s very tall (I’m really short) and has an enviable, unflappable sense of who she is. Her father, Jarvis, is Sebastian’s nemesis, so she sometimes finds herself caught between two people she loves. And she has more than a touch of her father’s ruthlessness in her, too, although she combines it with a sense of social responsibility and empathy he utterly lacks.

And what brings Hero and Sebastian to Paris in March 1815?

When the series begins, Sebastian thinks his mother is dead, that she was lost in a boating accident when he was 11. But by 1815 he knows the truth—that she ran off with a lover. Since that discovery he’s been looking for her, to ask her for the answers to some very important questions. Now that the war is over (or so everyone thinks) and their son is old enough to comfortably make the journey, he and Hero join the hordes of British aristocrats who at that time were flocking to Paris—which is where Sebastian has learned she’s now living with her lover, one of Napoleon’s generals.

The background to the whole series has been the Napoleonic Wars. At the beginning of this novel, Napoleon is in exile on Elba, but it’s not a spoiler to say he doesn’t stay there. How does his escape affect the atmosphere in Paris and your characters’ lives at this particular moment?

This aspect of When Blood Lies was intriguing to write. At first there are rumors that Napoleon is planning a return, but almost everyone expects him to fail spectacularly if he tries (these reactions are all historically accurate and taken from the letters, diplomatic dispatches, newspapers, and memoirs of the time). Then, once news of his escape reaches Paris, everyone still thinks it’s basically a joke, that he’ll quickly be stopped. They keep thinking this for days. So as Sebastian is frantically trying to figure out who killed his mother and why, Napoleon keeps getting closer and closer (remember, news traveled slow in those days), until people start to panic and everyone from the British ambassador’s wife (the Duchess of Wellington) to the recently restored Bourbon king frantically try to flee Paris. It’s human nature when the “unthinkable” starts to happen—whether it’s a pandemic spreading rapidly around the world or a sociopath making moves to take over a modern democracy—there is this tendency for people to think, “Oh, it can’t happen.” Except that it can and frequently does.

This novel just came out, but as we know, publishing takes a while. What are you working on now, and will there be an eighteenth Sebastian St. Cyr mystery?

I’m currently finishing writing the eighteenth Sebastian St. Cyr. I should have been done by now, but my house in New Orleans was wrecked by Hurricane Ida and I’ve spent the last six months repairing it, traveling back and forth between Louisiana and Texas, and moving into a new house in San Antonio. But the book will still be out in 2023, so no worries!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Candice Proctor, aka C.S. Harris and C.S. Graham, is the USA Today bestselling, award-winning author of more than two dozen novels, including the Sebastian St. Cyr Regency mystery series written under the name C.S. Harris, the C.S. Graham thriller series co-written with Steven Harris, and seven historical romances. She is also the author of a nonfiction historical study of women in the French Revolution. Find out more about her and her writing at https://csharris.net.

Candice Proctor, aka C.S. Harris and C.S. Graham, is the USA Today bestselling, award-winning author of more than two dozen novels, including the Sebastian St. Cyr Regency mystery series written under the name C.S. Harris, the C.S. Graham thriller series co-written with Steven Harris, and seven historical romances. She is also the author of a nonfiction historical study of women in the French Revolution. Find out more about her and her writing at https://csharris.net. Images: Joseph Beaume, Napoleon Leaving Elba (1836); Fashion Plate, La Belle Assemblée (1814); Charles de Steuben, Napoleon’s Return from Elba (1818), all public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

April 1, 2022

Long Live the King?

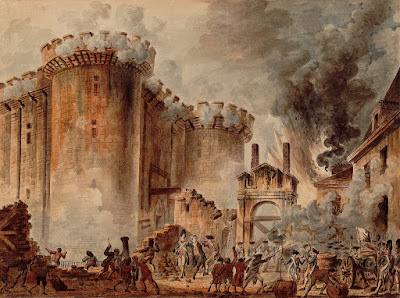

The French Revolution is not at present quite the publishing powerhouse it has sometimes been, but it still draws a good deal of attention. It’s such a dramatic setting, so it’s no wonder that many novelists succumb to the lure. I myself set The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel there—or at least in a virtual version of there—before turning my focus to sixteenth-century Russia and the steppe.

The French Revolution is not at present quite the publishing powerhouse it has sometimes been, but it still draws a good deal of attention. It’s such a dramatic setting, so it’s no wonder that many novelists succumb to the lure. I myself set The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel there—or at least in a virtual version of there—before turning my focus to sixteenth-century Russia and the steppe.Eva Stachniak’s The School of Mirrors ends with the Terror, but it opens in Paris a good forty years before the forces of reform become radicalized, in the wildly extravagant court of Louis XV (r. 1715–1774). The king, approaching forty, has an official mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who no longer wants a physical relationship. She does, however, want to ensure that no one who replaces her in the king’s bed can threaten her position as the main power behind the throne. So she endorses a scheme to lure innocent girls, no older than thirteen or fourteen, out of poverty and into a school that will train them to sate the king’s appetites.

As Eva Stachniak explains during our New Books Network interview, her heroine Véronique has a real antecedent, although this story is fiction. And as in real life, the heroine’s brief relationship with the king has consequences that both spool out into history and reveal the callousness and excess that lit the flames of revolution.

As Eva Stachniak explains during our New Books Network interview, her heroine Véronique has a real antecedent, although this story is fiction. And as in real life, the heroine’s brief relationship with the king has consequences that both spool out into history and reveal the callousness and excess that lit the flames of revolution.The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

France in 1755 is a country of extremes. The streets of Paris are filled with the poor and downtrodden, whereas just a few miles away lies the Palace of Versailles, with its renowned Hall of Mirrors where courtiers under the eye of Louis XV while away the hours amid endless extravagance. Once known as Louis the Beloved, the king has steadily lost ground with his people, and even his long-term relationship with Madame de Pompadour has entered a new phase. To retain her power and appeal to the king’s changing appetites, Madame enlists the help of Dominic-Guillaume Lebel, Louis’s valet de chambre. He sets up a school in Deer Park (Parc-aux-Cerfs), near the palace, where carefully selected thirteen- and fourteen-year-old girls from poor families can master basic literacy, painting, music, dance, embroidery, manners, and court protocol. Those who succeed in pleasing the king leave with a dowry and an income for life. Even those who fail receive some kind of financial settlement.

Véronique Roux, a printer’s daughter fallen on hard times, enters the school and does well—until a chance remark leads to her hasty dismissal. Years later, a little girl named Marie-Louise—who, as we know from the book jacket, is Véronique’s daughter, sired by the king and wrenched from her mother at birth—is summoned to Versailles and turned over to two of Madame de Pompadour’s servants for her education. Marie-Louise wants nothing more than to find the parents who abandoned her, without knowing who they are, and through her story we see the connections of Louis XV’s failures as a ruler and how they lead to the French Revolution in 1789.

Eva Stachniak takes the element of the real-life school at Deer Park and builds it, through the fictional characters of Véronique and Marie-Louise, into a powerful indictment of both a monarchy in decline and the radicals who sought to overthrow it at all costs, even when their initial idealism caused them to turn against one another.

Images: Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XV (1730); François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour (1756); and Jean-Pierre Houël, The Storming of the Bastille (1789), all public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Images: Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XV (1730); François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour (1756); and Jean-Pierre Houël, The Storming of the Bastille (1789), all public domain via Wikimedia Commons. March 25, 2022

Interview with Andrea Penrose

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I discovered Andrea Penrose’s Wrexford & Sloane series of Regency mysteries by accident, through an Amazon recommendation. I read them all and had the chance to interview her for the New Books Network when the latest, Murder at the Royal Botanic Gardens, came out with Kensington Books last fall.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I discovered Andrea Penrose’s Wrexford & Sloane series of Regency mysteries by accident, through an Amazon recommendation. I read them all and had the chance to interview her for the New Books Network when the latest, Murder at the Royal Botanic Gardens, came out with Kensington Books last fall.Somewhere along the way, I discovered that she had written a second series—also set during the Regency and featuring an earl, Lord Saybrook, and his initial adversary, later wife, Lady Arianna Hadley. The combination of Russians and chocolate persuaded me to give Lady Arianna a try, and soon I had polished off that series too. And now, to celebrate the release of Lady Arianna no. 7, A Swirl of Shadows , the author herself is here to answer my questions. I’m delighted to welcome her.

What was your inspiration for this series?

The Regency era in and of itself was a core inspiration. I love the time period because it was a fabulously interesting time and place—a world aswirl in silks, seduction, and the intrigue of the Napoleonic Wars. Radical new ideas were clashing with the conventional thinking of the past. People were questioning the fundamentals of society, and as a result they were fomenting changes in every aspect of life. Politics, art, music, science, social rules—the world was turning upside down, especially as women were really beginning to challenge the boundaries of their traditional roles in society.

I really like writing about people who are both strong and vulnerable. We all have strengths and weaknesses, and how we learn to balance those conflicting elements is, to me, an integral part of the human experience. An author can, of course, play with those tensions in any era, but for me the Regency presents a particularly interesting time in which to do so with an unconventional heroine.

Lady Arianna Hadley is a fascinating character. She develops over the course of the series, but tell us what you’d like readers to know about her going in.

Arianna has a gritty backstory, and in the first book she has come to England to seek revenge. Strong, clever and resourceful, she’s had to look out for herself for most of her life, and so trust doesn’t come easily for her. But she has a strong moral compass and a passion for justice, having had personal experience with injustices. That makes her an excellent sleuth.

Her initial interactions with the Earl of Saybrook are, shall we say, more confrontational than collegial. What can you tell us about him, and why don’t they get along at first?

Like Arianna, Saybrook is a complicated person. A titled aristocrat, a former military intelligence officer, and a brilliant botanist, he’s an outsider in the beau monde because his mother was a foreigner. When readers first meet him, he’s recovering from a serious war wound in London and is asked by the government to investigate the poisoning of the Prince Regent at a fancy supper party—where, disguised as a male chef, Arianna did the cooking. During their first encounter, their verbal fencing takes a sharper edge, but circumstances force them to become reluctant allies to find the real culprit, which leads them to uncover an even more sinister plot … and develop a a grudging friendship.

I have to admit that what first drew me to these books was the combination of Russians and chocolate, more specifically cacao. We’ll get to the Russians in a minute, but what made you want to include the chocolate?

In a sense, it happened by accident! For a very different project, I had stumbled across the fascinating fact there there was edible chocolate in the Georgian/Regency era. (The common perception is it was invented in 1847.) Sulpice Debauve, the personal physician to Marie Antoinette, concocted disks of flavored chocolate and spiked them with her medicines because otherwise she refused to take them. To make a long story short, he went on to open a chocolate shop in Paris in 1800. (You can read a long history of chocolate on my website under the “Diversions” tab.)

My agent loved the chocolate info and suggested we send out a proposal for a “chocolate mystery” set in the Regency. I pondered the idea, saw some really interesting possibilities, and came up with Arianna—who wasn’t at all the heroine that my agent expected! She had envisioned a cozy mystery series revolving around the proprietor of a chocolate shop who gets involved in solving mysteries in her town. I had different ideas. I wanted to write an edgier type of series that dealt with both the glittering ballrooms of London and the dark side of the beau monde, where the misuse of power and privilege was rampant.

As I said, my agent was surprised—but she really liked the sample chapters I did, and we sold it to Penguin Putnam. The line ended up being reorganized, and they didn’t offer to continue the series. But I loved writing it so much that I decided to continue the stories as a self-published series.

The overall background to these novels is the political negotiations—and machinations—surrounding the end of the Napoleonic Wars. By the time we get to A Swirl of Shadows, Arianna and Saybrook are being encouraged to travel to St. Petersburg. Why? And what do they find when they get there?

Tsar Alexander was a really interesting and important figure in the Regency era. Handsome and charming, he was also mercurial and enigmatic. He was a key leader in defeating Napoleon, but his own personal weaknesses made him vulnerable to intrigue and schemers. Actual history records that he did fall under the spell of a woman mystic and that her influence threatened his reign. In A Swirl of Shadows, the British government asks Arianna and Saybrook—who know Alexander from a previous mystery in Vienna—to journey to St. Petersburg to stop an American adventuress from orchestrating a clever plot that will topple the tsar from his throne and threaten Europe’s new-found peace.

However, when they arrive, they find things aren’t at all what they seem, and with the Imperial Court a viper’s nest of intrigue and betrayals, Arianna and Saybrook must cobble together a band of unexpected allies in order to beat the devil at his own game.

The person doing the encouraging, not to say arm-twisting, is Lord Grentham, who has been present from the beginning of the series. Give us a capsule description of him, please.

Grentham has been a really interesting character to develop. As Britain’s top spymaster, he’s ruthlessly cold and pragmatic, and I intended him to be a foil for Arianna and Saybrook’s more finely honed sense of fair play and justice. But it turns out he had other ideas about that and is a far more nuanced character. It’s funny how that can happen to an author!

I can’t let you go without asking about Arianna’s friend Sophia. Who is she, and why does she decide to accompany them to St. Petersburg?

I can’t let you go without asking about Arianna’s friend Sophia. Who is she, and why does she decide to accompany them to St. Petersburg?Sophia also has hidden facets. She and Arianna are very different personalities, shaped by the fact that they both had have painful experiences in the past. At first, they are wary of each other, but as often happens in real life, seemingly mismatched people can develop a very interesting friendship.

With Sophia, I have enjoyed playing with taking a person’s core vulnerability and turning it into a strength. Sophia demands to accompany Arianna and Saybrook to St. Petersburg because she feels that her particular expertise will be invaluable to them. There are also very personal reasons involved, but I shall leave them for readers to discover!

This novel just came out. What are you working on now, and can we look forward to another Lady Arianna adventure?

I’m currently working on a new Wrexford & Sloane mystery, which is also set in the Regency era. There’s also another possible project percolating, but for now it’s just in the “thinking” stage. We’ll see where it goes. As for Arianna, I am in the first stages of sketching out a new plot for her and Saybrook. So stay tuned!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Andrea Penrose is the bestselling author of Regency-era historical fiction, including the acclaimed Wrexford & Sloane mystery series. Find out more about her at https://andreapenrose.com.

Images: Thomas Lawrence, Alexander I (1814–1818), and Efim Tukharinov, The Rotunda (of the Winter Palace, 1834) both public domain; photograph of cacao pods © Tamorlan, own work, CC BY 3.0—all via Wikimedia Commons.

March 18, 2022

Mad Kings and Murderers

Reading historical mysteries has many benefits beyond the pure fun of solving an intellectual puzzle: who, among many possible suspects with means and motive, actually killed the victim? And yes, it sounds odd to use the term “intellectual” in reference to something as emotionally fraught and socially disruptive as murder, but that’s the point of reading a novel rather than living an experience in real time. Real-life killings evoke a whole range of responses—rage, grief, terror. A victim in a book is just a body; at best, we learn enough about the character to feel sorrow for that person’s passing, to appreciate the mourning of those left behind. The detective, amateur or professional, focuses on the suspects, and therefore so do we.

Reading historical mysteries has many benefits beyond the pure fun of solving an intellectual puzzle: who, among many possible suspects with means and motive, actually killed the victim? And yes, it sounds odd to use the term “intellectual” in reference to something as emotionally fraught and socially disruptive as murder, but that’s the point of reading a novel rather than living an experience in real time. Real-life killings evoke a whole range of responses—rage, grief, terror. A victim in a book is just a body; at best, we learn enough about the character to feel sorrow for that person’s passing, to appreciate the mourning of those left behind. The detective, amateur or professional, focuses on the suspects, and therefore so do we.In a historical setting, though, we also—if the author has paid due attention to the differences between present and past—get a sense of changing times and attitudes. Is a death attributed to sorcery or demonic possession? Does the killer, in the views of those involved, express innate evil or human frailty? Was the murder “justified” because the victim violated society’s laws? Or is the killer the one whose defiance of the rules demands the imposition of extreme penalties?

Tania Bayard explores these questions and more in her Christine de Pizan novels, the subject of my latest New Books Network interview. Set in fourteenth-century France, often at the royal court in Paris, the murders take place in and reflect the concerns of a medieval world taking its first steps toward the Renaissance. The king—Charles VI, known as “the Mad” ever since his attack on his own men in the midst of battle—suffers from a series of psychotic episodes that most of the populace attributes to witchcraft and sorcery. Constant in-fighting between the queen, the regent, and various relatives who would like to replace the regent fuels the general sense of fear and uncertainty.

Tania Bayard explores these questions and more in her Christine de Pizan novels, the subject of my latest New Books Network interview. Set in fourteenth-century France, often at the royal court in Paris, the murders take place in and reflect the concerns of a medieval world taking its first steps toward the Renaissance. The king—Charles VI, known as “the Mad” ever since his attack on his own men in the midst of battle—suffers from a series of psychotic episodes that most of the populace attributes to witchcraft and sorcery. Constant in-fighting between the queen, the regent, and various relatives who would like to replace the regent fuels the general sense of fear and uncertainty. Even without that immediate context, the lingering results of past decisions by the king, ongoing hostilities with neighboring lands, changing views of women (stridently opposed by many in the Church and the universities), endemic poverty and disease, and the increasing power of merchants in a society still ruled by warrior aristocrats play into views of justice and mercy and sin that govern people’s reactions to sudden, unexplained death.

And in a strange way, we can see our own pandemic-tinged world, with its ongoing war between superstition and science, dimly reflected in Bayard’s vividly realized medieval kingdom and refracted through the persona of her fictionalized heroine—the poet, scribe, philosopher, and defender of women’s right to be considered fully human and capable Christine de Pizan (1364–c. 1430).

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. The interview is also featured on LitHub.

There is a great temptation, when writing about the past, to sanitize its circumstances and attitudes to make the characters more palatable to present-day readers. Tania Bayard, who has written four mystery novels set in fourteenth-century France, does not make that mistake. Her Paris is filthy and smelly, with muddy streets and refuse lying in heaps, horrible diseases, stray dogs, and dead rats in the gutters. Her characters, too, wallow in prejudices and superstitions of all sorts. And those streets are filled with beggars, prostitutes, thieves, cheats, and would-be sorcerers and witches, ready to prey on upstanding citizens.

Yet fourteenth-century France, in these novels as in real life, also contains farsighted thinkers, gifted artists of all sorts, and would-be scientists. One of the shining lights is Christine de Pizan, a scribe at the court of Charles VI “the Mad” who will soon establish a name for herself as a poet and early feminist. Contrary to the stereotypes of medieval women as passive and obedient, Christine works hard to support her family and resolutely challenges the prejudices of the men around her, especially her frequent bête noire and sometime supporter, Henri Le Picart.

In Murder in the Cloister, the sudden death of a young nun causes the prioress to summon Christine, who has already solved three crimes affecting the royal family, to find out what happened. On the surface, Christine has been hired to copy an important manuscript, but her investigations turn up not only secrets and lies but ongoing sources of tension among the nuns. And even as she races to untangle the mystery before more deaths occur, she must counteract Henri’s efforts to protect—or is it undermine?—her and what she fears is his undesirable influence on her young son.

In Murder in the Cloister, the sudden death of a young nun causes the prioress to summon Christine, who has already solved three crimes affecting the royal family, to find out what happened. On the surface, Christine has been hired to copy an important manuscript, but her investigations turn up not only secrets and lies but ongoing sources of tension among the nuns. And even as she races to untangle the mystery before more deaths occur, she must counteract Henri’s efforts to protect—or is it undermine?—her and what she fears is his undesirable influence on her young son.Bayard has taken some flak for her decision to adopt a historical person as her fictional detective, but as she notes during this interview, any character she could have invented would have been less complex and less credible than Christine, who defied both her own society’s expectations and our own limited view of medieval women. So relax, don’t worry too much about the details of the crimes being fictional, and enjoy parachuting into a fully imagined past that you can hope never to experience in real life.

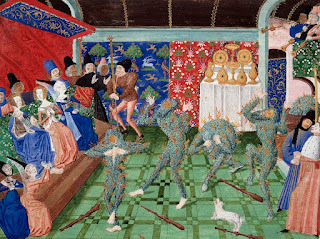

Images: Charles VI attacking his own men and of Le Bal des Ardents (The Ball of Burning Men), from a 14th-century book of hours, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

March 11, 2022

Mysteries Past and Present

Donnell Ann Bell was nice enough to post this comparison of mysteries set in the present versus the past on her blog last week. But once you’re done reading it here, do check out her other posts—and her books, if you like contemporary suspense novels—as well.

Imagine the following scenario: two sisters decide to leave the big city to spend the summer at their second home. They travel with several children and assorted family members. Along the way, someone attempts to ambush them, then flees before they can ascertain whether the objective was robbery or murder. The sisters don’t recognize the attackers and therefore can’t be sure why they’ve been targeted, although they do have an enemy and suspect him of giving the orders.

So far, we could be looking at an incident from any novel with elements of mystery or suspense. But what happens next depends greatly on when and where the attack takes place. In the modern world, the sisters would call the police from a cellphone, probably even while the assault was underway—unleashing the full panoply of sirens, all points bulletins, computer searches, DNA tests, and police raids. The search might not lead to an arrest in real life, but in a novel readers would experience a dramatic, high-tension chase as the investigation proceeds to its logical conclusion.

As it happens, though, these sisters live in sixteenth-century Russia. They have no police to call and no phones with which to summon them. There are bailiffs who make arrests, but who bears responsibility for supervising a particular stretch of road remains unclear. The local authorities have never heard of fingerprinting, never mind genetic testing or computerized records. And the robbers, having escaped, can vanish into the vast, uncharted countryside and return to fight another day.

Therein lies the drama, from the perspective of a historical novelist. The technological advances that drive a modern detective or suspense novel certainly have their advantages, especially in real life, but from a fictional standpoint at times they make cases almost too easy to solve. Against such detailed information, imagine the possibilities offered by the past, where characters can plausibly flee into the woods and set themselves up as bandit chieftains, disappear for months on end without communicating by e-mail or texting or even through letters, misrepresent themselves as scions of noble or royal houses without being detected, or break into a home or an office without leaving a trace that anyone investigating the crime can detect.

It would be hard to pull off any of these plot points now, yet I’ve used some version of them all in my Legends of the Five Directions and Songs of Steppe & Forest novels. The incident described in my opening paragraph comes from my latest novel, Song of the Sinner, and involves the heroine of that book, Solomonida, and her younger sister Darya, who have left Moscow in the hope of escaping the attention of their bullying cousin Igor, intent on grabbing their property and in general making them pay for daring to thwart his plans for marrying them off, whatever they think of his choices. Like the trip to the country, Igor’s motivation is timeless: he wants to benefit himself, no matter the cost to others.

But the means he uses to attain his goals are not those of the modern world, and the counter-measures adopted by Solomonida and Darya are different, too. The attempted ambush fails because they travel with an armed escort, a normal precaution taken by aristocrats at the time, and the escort remains with them to guard their estate against these or any other criminally minded sorts. Igor doesn’t have to worry about surveillance cameras and drones, and his rank protects him even when he’s fingered in a later assault on the hero. But his own inability to read trips him up time after time, as does his tendency to discount potential opposition from women and members of the lower classes, a category that in his mind includes even the highest-ranking civil servants—men (and yes, in those days they were all men) who in our own time would head corporations, excel in the law courts, or resolve international crises.

So if you are writing a story where the only means of stopping your villain is to use the latest bells and whistles, a contemporary saga is the way to go. But if you really want to push your protagonists to the limits, consider taking a time machine into the past. You may be surprised by the vistas that suddenly open up before you.

Images from Pixabay, no attribution required.

March 4, 2022

The Power of Family

In these troubled times, with Russia launching a military attack against neighboring Ukraine in a misguided attempt to restore—literally or figuratively—the Slavic portion of the old Soviet empire, it seems like a strange coincidence that my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview explores the disintegration of that Soviet empire’s predecessor and the early days of Bolshevik power. But this is, in fact, part of the complex history of Russia’s relationship with its neighboring states and, more broadly, with Europe. So the subject of this novel, conceived at least two years ago, is more pertinent to the present than it may appear at first glance.

In these troubled times, with Russia launching a military attack against neighboring Ukraine in a misguided attempt to restore—literally or figuratively—the Slavic portion of the old Soviet empire, it seems like a strange coincidence that my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview explores the disintegration of that Soviet empire’s predecessor and the early days of Bolshevik power. But this is, in fact, part of the complex history of Russia’s relationship with its neighboring states and, more broadly, with Europe. So the subject of this novel, conceived at least two years ago, is more pertinent to the present than it may appear at first glance.The history of the Russian Revolution, including the assassination of Emperor Nicholas II and his wife and children, has been so thoroughly researched that spoilers are not really possible. But what Bryn Turnbull does in The Last Grand Duchess is to focus in on the Romanovs as a family—their strengths and weaknesses, their conflicts and desires, and above all their deep and lasting devotion to one another even as events spin out of their control. Although elements of the story are fictional, as one would expect, Turnbull hews pretty close to the facts, and in doing so she both raises questions—suppose the daughters had married foreign princes before the revolution?—and offers explanations of otherwise troubling points in their history (why the emperor and empress did not send their children out of the country when that was still possible, for example).

Above all, she individualizes the five younger members of the family, who have at times been caricatured as the sick princeling Alexei and an undifferentiated OTMA, comprising the four daughters. She also manages to produce a balanced and convincing portrayal of Rasputin. So although you probably know how the story ends, read the novel anyway. And as we work our way through another episode of imperial overreach, you may even find it eerily prescient.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from the New Books Network.

Interest in the events leading up to the Russian Revolution of 1917 has only increased since the centenary of the Romanovs’ assassination in 1918. Bryn Turnbull tackles this familiar story from the perspective of Emperor Nicholas’s eldest daughter, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895–1918).

The novel opens with a prediction, made on the day of Olga’s birth, that the infant grand duchess would “not live to see thirty.” From there it moves to 1907, when the young heir to the throne, Tsarevich Alexei, is on the brink of death due to uncontrolled bleeding, the result of his hereditary hemophilia. Enter Grigori Rasputin, who enacts a miracle cure, saving the boy’s life and earning himself the undying gratitude of the desperate empress.

With this central conflict established—including the secrecy maintained around the nature of Alexei’s illness for as long as he remained heir to the throne—we shift forward in time to Nicholas II’s abdication in March 1917. The two stories of the revolution and the years that preceded it intertwine, with accounts of Olga at parties or nursing during World War I interspersed between chapters detailing the increasing confinement of the family after the revolution, from the Alexander Palace in Petrograd to a house in Siberia, then their transfer to the mansion in Ekaterinburg where the assassination took place.

Olga makes a compelling narrator, old enough to see what’s going on and have opinions about it but young enough to enjoy life, whether that means flirting at her coming-out party, chatting with a handsome wounded army officer, or riding a sled down Snow Mountain, a structure built by her and her siblings at the interim house in Tobol’sk. She is intensely family-focused, devoted to Russia, and charmingly naive due to her sheltered upbringing. Indeed, if one thing comes through in this richly described and thoughtful novel, it is the love of Nicholas II, his wife, and his children for one another—even if their insistence on staying together dooms them all.

Many factors, of course, lay behind the Russian Revolution, and The Last Grand Duchess hints at poverty, disillusionment, the massive casualties of the Great War, and Bolshevik determination as well as Nicholas’s limitations as a ruler, Alexandra’s shortcomings, Rasputin’s ambition, and the “ministerial leapfrog” to which those failings gave rise. But the strength of fiction lies in its ability to draw us into the minds and hearts of a small group of people, and in this case, that group is Olga and her immediate family. It’s a journey well worth taking.

February 25, 2022

Perils of an Empty Throne

I met Patrycja Podrazik, who writes under the name P.K. Adams, not long before the release of her second novel featuring the eleventh-century mystic, physician, and theologian Hildegard of Bingen. I have since interviewed her twice for the New Books Network, once on the Hildegard novels, and a second time for her historical mystery series set in sixteenth-century Poland. And if you’ve been following this blog, you’ll know that we have also co-written a historical mystery/suspense novel about the early interactions between Muscovy, the lands to its west, and the Tudor sailors who “discovered” Russia in 1553. So it’s a pleasure to welcome her today as my guest.

I met Patrycja Podrazik, who writes under the name P.K. Adams, not long before the release of her second novel featuring the eleventh-century mystic, physician, and theologian Hildegard of Bingen. I have since interviewed her twice for the New Books Network, once on the Hildegard novels, and a second time for her historical mystery series set in sixteenth-century Poland. And if you’ve been following this blog, you’ll know that we have also co-written a historical mystery/suspense novel about the early interactions between Muscovy, the lands to its west, and the Tudor sailors who “discovered” Russia in 1553. So it’s a pleasure to welcome her today as my guest.Adam’s Silent Water begins with the arrival of Caterina Sanseverino, a widowed Italian noblewoman, in Kraków in April 1518. Caterina is traveling with Queen Bona Sforza, on the route to her wedding with Poland’s King Zygmunt I. Fast forward to Christmas 1519, and Caterina, now established in her position at court, encounters a series of puzzling murders, and her resolution of the mystery leads to her recruitment for a difficult political task by Queen Bona during a later visit to the Polish capital in 1545. That task in turn pushes Caterina into investigating another set of deaths in Midnight Fire . By the time this third novel— Royal Heir , released two months ago—opens, Caterina is enjoying her old age in Italy, and her son takes center stage.

There is, of course, a particular irony in publishing this post a day after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, an attack based on the pretext that Ukraine is no more than a breakaway province that needs to be reintegrated into the whole. Although the long complex history of Ukraine as part of the joint Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom is more visible in Midnight Fire than in this new novel, another century would pass before the Cossack rebellion that led to Ukraine’s request for Russian suzerainty.

There is, of course, a particular irony in publishing this post a day after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, an attack based on the pretext that Ukraine is no more than a breakaway province that needs to be reintegrated into the whole. Although the long complex history of Ukraine as part of the joint Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom is more visible in Midnight Fire than in this new novel, another century would pass before the Cossack rebellion that led to Ukraine’s request for Russian suzerainty.And with that, I turn the virtual mike over to P.K. Adams, with thanks for sending me this post laying out the historical background of her Jagiellon Mysteries and why she decided to use this troubled political situation in writing Royal Heir. But do listen to the interviews to find out more about the series—and, of course, read the books!

An uncertain succession to the throne is a challenge familiar to monarchies throughout the ages. It has opened doors to ambitions, struggles, and acts of deception and violence that have cost lives, changed states’ borders, and sent their history on a new course. In fact, such is the dramatic potential of a vacant (or soon to be vacant) throne that it has inspired works of fiction for centuries, and, in more recent times, has given rise to enormously popular TV series and movies.

How lucky, then, that a crisis of this kind unfolded in Poland-Lithuania in the second half of the sixteenth century, the period in which my series Jagiellon Mysteries is set. Lucky for me, that is, not for the state or the people who lived in it at the time. After nearly a century known as the Golden Age—most of it under the rule of the last two Jagiellon kings, Zygmunt I (the Old) and Zygmunt II August—Poland had reached the peak of its size and political influence. Its possessions stretched from the Baltic in the north to the shores of the Black Sea in the south. It had a vibrant artistic life influenced by the ideas of the Italian Renaissance. Polish scholars took degrees at western European universities, and foreign intellectuals flocked to study and debate at the Cracow Academy (now Jagiellonian University).

However, by the 1560s, dark clouds began to gather on the horizon. The long-standing conflict between Zygmunt August and the powerful noble class had hamstrung the administrative and judicial reforms needed to strengthen the state. Moreover, after the premature death of his beloved second wife, Barbara, the king contracted a loveless marriage to Catherine Habsburg that quickly fell apart, and with it vanished the hope for an heir. In his mid-forties, with flagging health and an increasing lack of interest in the affairs of state, the king no longer guaranteed the stability of his kingdom. Still, while he was alive, Poland-Lithuania could consider itself reasonably secure from outside threats. One can only imagine, however, the anxiety with which magnates, officials, and ordinary men and women thought about the inevitable moment when the throne became vacant and powerful neighbors—the Habsburgs, in particular—reached for the trophy that was the crown of the dual monarchy.

However, by the 1560s, dark clouds began to gather on the horizon. The long-standing conflict between Zygmunt August and the powerful noble class had hamstrung the administrative and judicial reforms needed to strengthen the state. Moreover, after the premature death of his beloved second wife, Barbara, the king contracted a loveless marriage to Catherine Habsburg that quickly fell apart, and with it vanished the hope for an heir. In his mid-forties, with flagging health and an increasing lack of interest in the affairs of state, the king no longer guaranteed the stability of his kingdom. Still, while he was alive, Poland-Lithuania could consider itself reasonably secure from outside threats. One can only imagine, however, the anxiety with which magnates, officials, and ordinary men and women thought about the inevitable moment when the throne became vacant and powerful neighbors—the Habsburgs, in particular—reached for the trophy that was the crown of the dual monarchy. When I considered ideas for the third book in the Jagiellon Mystery series, telling a story tied to the uncertain succession seemed like a no brainer. Although there is no historical record of an assassination plot, the last decade of Zygmunt August’s life (he died in 1572) must have been rife with scheming and planning for what would happen if he failed to produce a legitimate heir. The drama would only have been heightened by the king’s increasingly reckless personal life, especially as contrasted with that of his God-fearing sister (and heir presumptive) Princess Anna. Zygmunt’s sexual exploits in that period became legendary and included the kidnapping and seducing of one of Anna’s own ladies-in-waiting. He also embarked on a scandalous affair with the daughter of a bourgeois Warsaw family, which resulted in the birth of a child. Of course, there could have been no question of the succession passing on to a baby who was born out of wedlock and whose paternity, although strongly suspected, could not be established beyond any doubt precisely because her parents were not married.

The plot of Royal Heir, which is set in the autumn of 1563, revolves around an attempt by a group of disgruntled noblemen to force Zygmunt August to abdicate so they can elevate his half-brother to the throne. The protagonist, who in this novel is Caterina’s son Julian Konarski, accidentally stumbles onto the scheme when he witnesses the fatal beating of a young man in a dark alley in one of Kraków’s less savory neighborhoods. But when he begins to dig deeper, the details of the plot fail to add up: Zygmunt August’s only half-brother (and an illegitimate one at that) died years ago, and an eavesdropping session conducted in the plotters’ lair reveals that their plans toward the king may be far less gentle than mere abdication.

Prompted by his youthful idealism, Julian begins a desperate race to a stop an act of regicide and avert a coup d’état. His love interest, Magda, bravely aids him in his quest, but by the time they realize the formidable nature of those they are up against, their lives, too, are in terrible danger.

P.K. Adams is the author of The Greenest Branch and The Column of Burning Spices, a pair of novels about the life of Hildegard of Bingen, and of the Jagiellon Mysteries. Find out more about her at https://www.pkadams-author.com.

February 18, 2022

Pushing the Envelope

Yesterday I changed the water bottle in our garage cooler. This was a stretch for me, in part because the bottle is heavy but also because, in a family with two mechanically minded members, I am the outlier. I felt certain that if a way existed to spray water across the floor, the car, and myself, I would find it. But I was the only person around at the time, and it needed to be done, so after a bit of investigation I decided to tackle the problem.

As things turned out, the process was simple enough that even I couldn’t mess it up, but it got me thinking about the demands that we as novelists impose on our characters. Except perhaps in a romantic comedy (where everything would go wrong, bringing hero and heroine together), reading about changing a water bottle, even one containing five gallons or so, would be a complete snore. Protagonists in novels have to surmount the kinds of obstacles that would cause most of us to run screaming for the hills. Just to cite a few examples published by Five Directions Press, plots can include an eighteen-year-old asked to defeat an ancient demon bent on destroying the humanity she once created (Gabrielle Mathieu, Girl of Fire); a sheltered sixteen-year-old girl confronting a known murderer intent on kidnapping two royal princes (my own Golden Lynx); and a pair of young men who embark on a voyage to the Amazon River in search of cash, only to endure a series of disasters that eliminates one member of their group after another (Joan Schweighardt, Before We Died).

So what is it with writers? Are we sadists in nerd clothing? “Psychologically distoybed,” in the words of West Side Story? Desperate for adventure but too wedded to our computers (and too isolated by nature) to seek it for ourselves?

Well, maybe some of the last. It is a great deal of fun to invent these extreme circumstances and throw oneself into imagining how a given character might cope with them. Channeling bad guys (and gals) is deliciously freeing too, so long as one can stash them away in their cages at the end of the day. And of course, one can never rule out hidden sadism or other forms of psychological disturbance. The general public probably already has its suspicions of people who claim to hear fictional beings chattering in their heads, even if those writers don’t themselves believe that the beings exist in any meaningful way.

But the real reason we torture our characters is simple: it makes for a good story. As readers, we get to sit back and watch, turn over potential responses in our minds, guess what the characters may do. We can live life in the fast lane without leaving our seats, and in doing so, we can explore emotions we hope never to experience: the yearning for revenge; the terror of facing a superior opponent; the moral quandary of balancing safety or reward against awareness of others’ needs or adherence to the social rules we were raised to respect. We can watch others make appallingly bad choices or rise to heroic heights we can only dream of reaching. In doing so, we prepare ourselves to face future crises. And no one is hurt in the process.

Or, to riff on Nancy Kress’s marvelous summary in her writing manual

Dynamic Characters

(“In life we want tranquillity; in our fiction we want an unholy mess, preferably getting unholier page by page” [159]), in life we want to worry about nothing worse than spilling water on the garage floor. In a novel, we want, if not murder and mayhem, at least an angry demon, a ruthless politician, or an environment filled with tarantulas, piranhas, and a jaguar or two. Much better to face such threats on the page than in real life!

Or, to riff on Nancy Kress’s marvelous summary in her writing manual

Dynamic Characters

(“In life we want tranquillity; in our fiction we want an unholy mess, preferably getting unholier page by page” [159]), in life we want to worry about nothing worse than spilling water on the garage floor. In a novel, we want, if not murder and mayhem, at least an angry demon, a ruthless politician, or an environment filled with tarantulas, piranhas, and a jaguar or two. Much better to face such threats on the page than in real life!