Mad Kings and Murderers

Reading historical mysteries has many benefits beyond the pure fun of solving an intellectual puzzle: who, among many possible suspects with means and motive, actually killed the victim? And yes, it sounds odd to use the term “intellectual” in reference to something as emotionally fraught and socially disruptive as murder, but that’s the point of reading a novel rather than living an experience in real time. Real-life killings evoke a whole range of responses—rage, grief, terror. A victim in a book is just a body; at best, we learn enough about the character to feel sorrow for that person’s passing, to appreciate the mourning of those left behind. The detective, amateur or professional, focuses on the suspects, and therefore so do we.

Reading historical mysteries has many benefits beyond the pure fun of solving an intellectual puzzle: who, among many possible suspects with means and motive, actually killed the victim? And yes, it sounds odd to use the term “intellectual” in reference to something as emotionally fraught and socially disruptive as murder, but that’s the point of reading a novel rather than living an experience in real time. Real-life killings evoke a whole range of responses—rage, grief, terror. A victim in a book is just a body; at best, we learn enough about the character to feel sorrow for that person’s passing, to appreciate the mourning of those left behind. The detective, amateur or professional, focuses on the suspects, and therefore so do we.In a historical setting, though, we also—if the author has paid due attention to the differences between present and past—get a sense of changing times and attitudes. Is a death attributed to sorcery or demonic possession? Does the killer, in the views of those involved, express innate evil or human frailty? Was the murder “justified” because the victim violated society’s laws? Or is the killer the one whose defiance of the rules demands the imposition of extreme penalties?

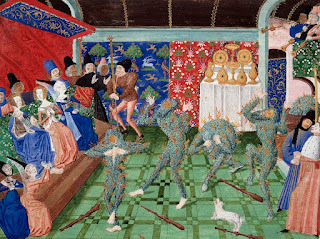

Tania Bayard explores these questions and more in her Christine de Pizan novels, the subject of my latest New Books Network interview. Set in fourteenth-century France, often at the royal court in Paris, the murders take place in and reflect the concerns of a medieval world taking its first steps toward the Renaissance. The king—Charles VI, known as “the Mad” ever since his attack on his own men in the midst of battle—suffers from a series of psychotic episodes that most of the populace attributes to witchcraft and sorcery. Constant in-fighting between the queen, the regent, and various relatives who would like to replace the regent fuels the general sense of fear and uncertainty.

Tania Bayard explores these questions and more in her Christine de Pizan novels, the subject of my latest New Books Network interview. Set in fourteenth-century France, often at the royal court in Paris, the murders take place in and reflect the concerns of a medieval world taking its first steps toward the Renaissance. The king—Charles VI, known as “the Mad” ever since his attack on his own men in the midst of battle—suffers from a series of psychotic episodes that most of the populace attributes to witchcraft and sorcery. Constant in-fighting between the queen, the regent, and various relatives who would like to replace the regent fuels the general sense of fear and uncertainty. Even without that immediate context, the lingering results of past decisions by the king, ongoing hostilities with neighboring lands, changing views of women (stridently opposed by many in the Church and the universities), endemic poverty and disease, and the increasing power of merchants in a society still ruled by warrior aristocrats play into views of justice and mercy and sin that govern people’s reactions to sudden, unexplained death.

And in a strange way, we can see our own pandemic-tinged world, with its ongoing war between superstition and science, dimly reflected in Bayard’s vividly realized medieval kingdom and refracted through the persona of her fictionalized heroine—the poet, scribe, philosopher, and defender of women’s right to be considered fully human and capable Christine de Pizan (1364–c. 1430).

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. The interview is also featured on LitHub.

There is a great temptation, when writing about the past, to sanitize its circumstances and attitudes to make the characters more palatable to present-day readers. Tania Bayard, who has written four mystery novels set in fourteenth-century France, does not make that mistake. Her Paris is filthy and smelly, with muddy streets and refuse lying in heaps, horrible diseases, stray dogs, and dead rats in the gutters. Her characters, too, wallow in prejudices and superstitions of all sorts. And those streets are filled with beggars, prostitutes, thieves, cheats, and would-be sorcerers and witches, ready to prey on upstanding citizens.

Yet fourteenth-century France, in these novels as in real life, also contains farsighted thinkers, gifted artists of all sorts, and would-be scientists. One of the shining lights is Christine de Pizan, a scribe at the court of Charles VI “the Mad” who will soon establish a name for herself as a poet and early feminist. Contrary to the stereotypes of medieval women as passive and obedient, Christine works hard to support her family and resolutely challenges the prejudices of the men around her, especially her frequent bête noire and sometime supporter, Henri Le Picart.

In Murder in the Cloister, the sudden death of a young nun causes the prioress to summon Christine, who has already solved three crimes affecting the royal family, to find out what happened. On the surface, Christine has been hired to copy an important manuscript, but her investigations turn up not only secrets and lies but ongoing sources of tension among the nuns. And even as she races to untangle the mystery before more deaths occur, she must counteract Henri’s efforts to protect—or is it undermine?—her and what she fears is his undesirable influence on her young son.

In Murder in the Cloister, the sudden death of a young nun causes the prioress to summon Christine, who has already solved three crimes affecting the royal family, to find out what happened. On the surface, Christine has been hired to copy an important manuscript, but her investigations turn up not only secrets and lies but ongoing sources of tension among the nuns. And even as she races to untangle the mystery before more deaths occur, she must counteract Henri’s efforts to protect—or is it undermine?—her and what she fears is his undesirable influence on her young son.Bayard has taken some flak for her decision to adopt a historical person as her fictional detective, but as she notes during this interview, any character she could have invented would have been less complex and less credible than Christine, who defied both her own society’s expectations and our own limited view of medieval women. So relax, don’t worry too much about the details of the crimes being fictional, and enjoy parachuting into a fully imagined past that you can hope never to experience in real life.

Images: Charles VI attacking his own men and of Le Bal des Ardents (The Ball of Burning Men), from a 14th-century book of hours, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.