C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 14

September 24, 2021

Death in Shanghai

One of the many rewards for me of well-executed historical fiction is that it opens a window onto times and places I know little about. At the end of a long day of editing or even in the midst of a writing vacation, I have little mental energy left to read academic history about anything except the period of greatest interest to me and most relevance for my novels—often I can’t handle even that. But a well-crafted story written by someone who has delved into the specifics of Tang China or the American West or Mughal India pulls me in and along, allowing me to revel in the experiences associated with foreign travel.

One of the many rewards for me of well-executed historical fiction is that it opens a window onto times and places I know little about. At the end of a long day of editing or even in the midst of a writing vacation, I have little mental energy left to read academic history about anything except the period of greatest interest to me and most relevance for my novels—often I can’t handle even that. But a well-crafted story written by someone who has delved into the specifics of Tang China or the American West or Mughal India pulls me in and along, allowing me to revel in the experiences associated with foreign travel.Garrett Hutson’s Death in Shanghai series is a good example of this point. He vividly recreates the atmosphere of Shanghai in the 1930s—a port city with a thriving international community and a degree of cultural openness equivalent to New York, Paris, or London. As he notes during my latest interview for the New Books Network, in the 1930s society aimed at freeing itself from Victorian restrictions through increasing gender equality and diversity, among other things, before the 1950s turned back the clock.

But although this theme gives impetus to character development in the books—especially that of the hero, Douglas Bainbridge, who struggles to balance the demands of a rigid upbringing against the reality of the city he adopts as his home—at their heart these are tension- and conflict-laden murder mysteries that move at a rapid pace yet provide satisfying and believable solutions to the problems they raise. So kick back, pour some tea or rice wine, and enjoy the ride.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Despite the deluge of novels about World War II that has characterized the last few years, the period leading up to the war on the Pacific Front has received far less attention. One welcome exception is the Death in Shanghai series penned by Garrett Hutson, the latest book of which is No Accidental Death (Warfleigh Publishing, 2021).

The series revolves around Douglas Bainbridge, a naval intelligence officer assigned to a two-year immersion program in Chinese language and culture. Doug has defied the expectations of his affluent but rigid parents by joining the US Navy instead of taking over the family business, and although he has already developed fluency in Mandarin, he is not emotionally prepared for the rich and varied life that awaits him in Shanghai’s International Settlement when he arrives in May 1935. It doesn’t help that he has barely unpacked his suitcases before a childhood friend, met by chance in a bar, winds up dead in the streets—with the local police all too willing to assign responsibility for the murder to Doug. Doug sets out to clear his name in that first novel, The Jade Dragon, in the process establishing a chain of tangled alliances and favors that help him through the sequel, Assassin’s Hood.

By the time No Accidental Death opens in July 1937, Doug has completed his immersion program and moved on to his dream job as intelligence officer on a naval vessel in the Yangtze fleet. His new position takes him away from Shanghai more than he likes, but it remains his home port. He’s eager to disembark and reunite with his beloved Lucy Kinzler and his cohort of friends. But soon a crewman from Doug’s ship is killed under mysterious circumstances and the Fleet Admiral charges Doug with solving the crime. Once again, Doug must place duty above pleasure—this time in the midst of an ongoing battle between the Japanese Navy and the Chinese National Army for the control of both Shanghai and Beijing.

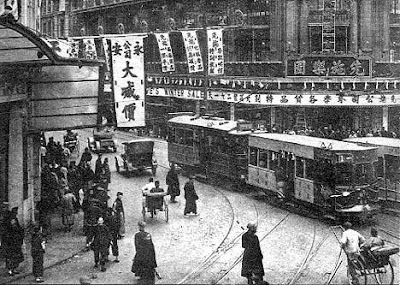

Image: Nanking (East Nanjing) Road, Shanghai, in the 1930s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

September 17, 2021

Interview with Jai Chakrabarti

As anyone who reads this blog knows, I am not a huge fan of fiction set during World War II. The circumstances of the war were so horrific, and the effects so traumatic, that it gives me nightmares—not what I’m looking for in light reading at the end of the day. That the journal I edit often publishes articles about the Holocaust in the East, where the worst atrocities took place, only increases my desire to keep my distance from the war when I have a choice.

As anyone who reads this blog knows, I am not a huge fan of fiction set during World War II. The circumstances of the war were so horrific, and the effects so traumatic, that it gives me nightmares—not what I’m looking for in light reading at the end of the day. That the journal I edit often publishes articles about the Holocaust in the East, where the worst atrocities took place, only increases my desire to keep my distance from the war when I have a choice.That said, I do recognize the long shadow cast by World War II on those who took part in it and on the generation that followed. For that reason, I agreed to read Jai Chakrabarti’s debut novel, A Play for the End of the World , which traces the way that those formative experiences influenced the course of his characters’ lives. Read on to find out more.

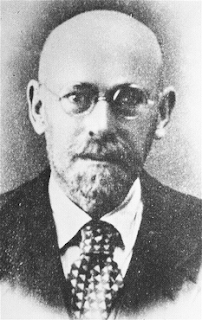

Where did you learn about Janusz Korczak and the performance of Rabindranath Tagore’s The Post Office in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942?

Many years ago, my wife and I had been living in Jerusalem on a travel grant. It was our last day in the city, and we wanted to visit Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum, while we still had the chance. It was there in the Art in the Ghettos exhibit that I first learned the story of Janusz Korczak—doctor, educator, and the head of a Warsaw orphanage with nearly two hundred children. In July 1942, weeks before the Great Deportations would begin, Korczak decided to stage a play by the revered Bengali author Rabindranath Tagore, and he invited the Jewish community of Warsaw to witness the performance. I found this to be an extraordinary coincidence—that I as an Indian man married to a Jewish woman—would encounter a play from my childhood in a Holocaust museum. At that moment, I knew I wanted to learn more, and this curiosity would eventually lead to years of research and take me to Poland and to the village in India where the play was composed.

What made you decide to turn that performance into the center of a novel? And, having decided, how did you go about crafting this particular tale?

I’m fascinated with the role of art in periods of societal and political turmoil. I believe Janusz Korczak thought of the performance of The Post Office as a kind of transgressive act that would also uplift his children and the Jewish community. At the same time, art can also be used to exploit or manipulate, and we experience a degree of this later in the novel when a professor in India decides to stage The Post Office in a village fighting political oppression. I wanted to explore these polarities, and I also learned that I was most interested in the aftereffects of trauma—much of the story takes place thirty years after the performance in Warsaw—so the play’s Warsaw performance and its echoes gave me a structure to work with.

Jaryk Smith, your main protagonist, is a fictional—I assume—survivor of Korczak’s orphanage. Tell us about him as a character.

As far as we know, none of the children from Janusz Korczak’s orphanage survived Treblinka, so Jaryk Smith, portrayed initially as a child under Korczak’s care, is indeed a fictional character. Jaryk survives a harrowing experience in Poland and relocates to New York City in the 1940s. He lands a job at a fish market and then eventually finds work at a synagogue, where he does maintenance, helps to keep the books, and organizes events for the Jewish High Holidays. He loves to listen to classical music and lives a life full of the same rituals of work and friendship. This rhythm is interrupted as he begins to unexpectedly fall in love.

Jaryk’s best friend is Misha, the only other survivor of that 1942 performance. They are reunited in the Displaced Persons camp and travel to New York together. Can you characterize their relationship for us?

Misha, who’s ten years older, sees himself as Jaryk’s older brother even though they aren’t biologically related. Misha feels it’s his responsibility to look out for Jaryk, especially in their early years in New York when they find an apartment in Brighton Beach. Misha is bold, loud, and extroverted in a way that Jaryk is not, and Misha’s friendliness and gregariousness often allow Jaryk to stay comfortably in the shadows. But as Jaryk falls in love, Misha believes Jaryk will be the one who’ll start a family and carry on their stories.

In 1972, Jaryk also loves a woman named Lucy, who has come to New York from the US South. But despite their immediate and intense attraction to each other, their relationship struggles against the power of Jaryk’s past. Why is that?

Jaryk is dealing with the effects of childhood trauma. As he finds himself drawn toward Lucy, he struggles at times to be vulnerable and to enter fully into the relationship. Misha’s death also shocks Jaryk and forces him to confront his own feelings without the benefit of his old friend’s guidance and support. Finally, Jaryk develops a sense of duty toward a village in India, and helping the villagers eventually comes into conflict with his love for Lucy.

The center of the novel has less to do with World War II and its horrors than with the decision of an Indian professor, Rudra Bose, to replicate the performance of The Post Office in a Bengali village not far from Shantiniketan, where Tagore spent a significant part of his life. What does Bose expect from this production?

I think that Rudra Bose is hoping for a couple of outcomes. First, he’s hoping that the performance of the play generates the kind of publicity that will help to protect the villagers and prevent them from being displaced. But he’s also hoping that the notoriety associated with the performance will elevate his own political ambitions. He sees the performance in the village as a stepping stone toward a much larger political movement that he will help to lead.

I think that Rudra Bose is hoping for a couple of outcomes. First, he’s hoping that the performance of the play generates the kind of publicity that will help to protect the villagers and prevent them from being displaced. But he’s also hoping that the notoriety associated with the performance will elevate his own political ambitions. He sees the performance in the village as a stepping stone toward a much larger political movement that he will help to lead.Jaryk originally resists taking part in the Indian production. Why is that, and what changes his mind?

Originally, Jaryk sees the Indian production as something Misha would have engaged in. At first, the idea of traveling to India to help co-direct the production of a play seems almost absurd because it’s so outside the rituals and boundaries of his life. But when Misha dies and Jaryk travels to India and begins to form relationships with the villagers, he also realizes that the performance of the play can help improve their situation; this sense of purpose motivates him to stay on and work for change.

And what of you? This novel came out in September 2021. Are you already working on something new?

Knopf will be publishing my collection of short stories in 2022, and I’m working on final edits to some of the stories now. I’ve also begun a new novel project that’s still in the early stages.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Jai Chakrabarti was born in Kolkata, India, and now splits his time between Brooklyn, NY, and the Hudson Valley. His short fiction has appeared in numerous journals, has been anthologized in The O. Henry Prize Stories and The Best American Short Stories, and won a Pushcart Prize. A Play for the End of the World is his first novel. You can find out more about him at https://www.jaichakrabarti.com.

Photographs of Janusz Korczak (1940), the children of his orphanage (1920s), and Rabindranath Tagore (1925) public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Photograph of Jai Chakrabarti © Peter Dressel, reproduced with permission.

September 10, 2021

The Ravages of Time

It often surprises my interview guests to learn that when I agree to take on a book, I read it cover to cover. There’s a reason I do that (in addition to my general love of reading, especially when it comes to historical fiction): novels have their own kind of emotional truth, so the true meaning of a book doesn’t always correspond to its subject.

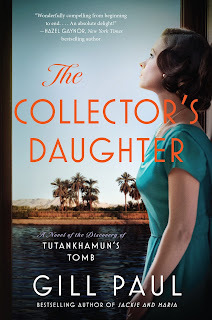

It often surprises my interview guests to learn that when I agree to take on a book, I read it cover to cover. There’s a reason I do that (in addition to my general love of reading, especially when it comes to historical fiction): novels have their own kind of emotional truth, so the true meaning of a book doesn’t always correspond to its subject.That’s especially true of a deeply moving, profoundly felt novel like Gill Paul’s The Collector’s Daughter , the subject of my latest New Books Network interview. Yes, the book explores the events surrounding and following the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922, and that is an interesting topic in and of itself—especially to lifetime fans of Elizabeth Peters’ Egyptology novels like me.

But the heart of The Collector’s Daughter is something quite different. It asks the question, in the author’s own words, “Can you still love someone when they no longer remember your shared past and may have an altered personality because of changes that have occurred in their brain?” The answer for Evelyn Herbert and her husband is a resounding yes, but the question affects us all—in our relationships with parents, spouses, or our own selves. And that makes this novel worth every minute you spend on it.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings almost a century ago revolutionized the study of ancient Egypt and its pharaohs. The splendors that surrounded the burial of this relatively minor ruler, interred in a hastily arranged tomb, sparked a furor of speculation, scholarship, and outright chicanery and draw crowds even today. For a long time, though, no one knew that the first modern person to enter the tomb was not Howard Carter, the famed archaeologist who located it, but Lady Evelyn (Eve) Herbert, the twenty-one-year-old daughter of Lord Carnarvon, who funded Carter’s expedition.

In The Collector’s Daughter (William Morrow, 2021), Gill Paul approaches the story of Carter’s discovery from the perspective of its long-term effects on those involved in the find. We meet Eve first in 1972, fifty years after these life-changing events, when she has just awoken in a hospital after suffering the latest in a series of strokes that sap her physical and mental strength. She barely recognizes the man sitting next to her, although she soon concludes (correctly) that he is her husband, Brograve.

As Eve fights her way back to health, Brograve attempts to jog her memory with photographs and tales, each of which sets off a trip into the past where we see what actually occurred and contrast it with Eve’s foggy recollections. Meanwhile, Brograve is doing his best to shield his wife from the demands of an Egyptian archaeologist determined to track down missing artifacts from the tomb—on behalf of her government, her university, or herself? We’re not quite sure of the archaeologist’s motives, only that she has secrets of her own.

The tale of Tutankhamun’s tomb, the accidents that followed its discovery, and how Eve came to be the first person to enter its suffocating atmosphere three thousand years after the ancient Egyptian priests sealed the sarcophagus is beautifully told. But what really sets The Collector’s Daughter apart is its haunting exploration of memory loss and its impact on Eve and Brograve’s long and loving marriage. This is definitely a book that you don’t want to miss.

Image of Horus pectoral from Tutankhamun’s tomb public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

September 3, 2021

The Mechanical Jeeves

About a month ago, one of my fellow Five Directions Press writers shared on our group’s Facebook page a link to a post by the BBC that asked the provocative question, “Can Technology Help Authors Write a Book?”

Being something of a geek when it comes to writing software, I read the BBC post with interest. It features a program called Lynit, now in beta testing, that supposedly allows authors to track characters, plot arcs, and more.

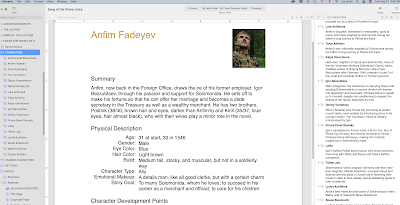

Now, I have nothing against Lynit, which I haven’t tried. But I was surprised to see this approach presented as something new. Not long after I began this blog in 2012, I wrote a post on my own favorite writing program, Storyist. It’s Mac-only on a desktop but has well-regarded iPad and iPhone versions, and it not only stores information about characters, plot, settings, research, and pretty much anything else I might need as reference—including pictures of my characters on a virtual corkboard—but supplies useful prompts about sources of conflict (in plot sheets), sensory information (settings sheets), and character development (character sheets). All these can be linked and displayed as index cards or outlines—leaving numerous different ways to approach a story to suit the needs of different writers.

In Storyist, the novel itself lives in a single manuscript composed of chapters and scenes that can be dragged into new positions or exported to styled RTF for Word import or to Kindle/ePub formats for reading. I use it every day I write; indeed, I keep my blog posts in it too, because it doesn’t throw in all the junk that Word does, which can complicate copying the text to Blogger, and it lets me stash a year’s posts in one place. Eventually, when I have a final draft, I import that RTF into InDesign or Affinity Publisher for typesetting.

But I don’t produce final e-books in Storyist, which has sufficient formatting controls for basic reading but not for publishing, in my view. For that I use Scrivener, which has a Windows version as well as Mac and tablet apps; many authors love it as much as I love Storyist. Its exact mix of features is, as one would expect, somewhat different, but it too stores research files and a separate manuscript with chapters and scenes. It supplies sheets for storing information on plot, characters, and setting, although they are more rudimentary than Storyist’s. It also stores each clipping of the manuscript as a separate file that must be compiled before use, which gives a writer a great deal of flexibility on export but can be annoying when you suddenly realize that what looks on screen like a single document is actually 150 disconnected pieces. Both Storyist and Scrivener can support more than one manuscript in a given file.

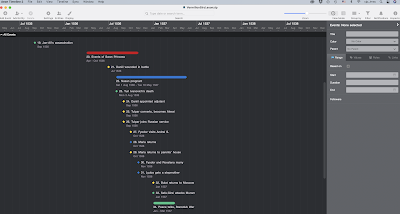

One plus of Scrivener is that it can link to the third program I use—much more intermittently than either of the two previous ones, but that says more about the way I write than the value of the program—Aeon Timeline. Of the three, this is the setup closest to Lynit. As the name suggests, Aeon Timeline allows you to visually display story events and character development over periods ranging from hours to centuries. I used it especially for my novels The Swan Princess (three point-of-view characters operating more or less independently, making it important to know where each one was relative to the others at a given point in the story) and Song of the Sinner (spans 1543–46, with a gap in the middle, during which the hero and heroine are out of contact with each other). I also use it when I’m plotting a story against a detailed historical background, so that I can chart where my invented lives intersect with reality, as in The Vermilion Bird. I haven’t used Aeon Timeline enough to test its limits, but it does allow writers to define their own calendars, so it should be possible to adapt it for all kinds of fiction.

Because, as I said above, I’m rather a geek about writing and publishing software, I have also in the past dipped a toe into Dramatica and Story Weaver, as well as other writing programs too numerous to mention. But do any of them really “help authors write a book”?

Well, yes, if what you mean by “help” is keeping track of information that can be easily lost—that passing mention to a character’s physical characteristics or age, the neat site you found online that explained Tatar wedding customs or calculated the date of Easter according to the Julian character in 1552, the great “what if?” option that came to you the night before which you don’t want to forget, even ideas for other novels that can be stowed in a note to keep you from haring off after them instead of focusing on the book underway. Both Storyist and Scrivener are great for those kinds of tasks, and having the information in the same program as your manuscript so you can click over to the note to check and back again to your writing can prove very handy. Similarly, on those occasions when you need to plot out a character arc or overlapping plot lines, Aeon Timeline or (probably) Lynit would simplify that work.

But alas, whatever their strengths, I don’t think any of these programs can really help you turn a story into a novel. To make that happen, you need to sit down, start typing, let the ideas flow, share the results with respected fellow writers, establish a small library of great books on the craft of writing to which you return over and over, and—last but far from least—revise, revise, revise. And the time put into learning a slew of programs might better be spent typing rough drafts. It’s too easy to get lost in the weeds of technology and forget that its fundamental purpose is to facilitate the act of writing, not to influence its content.

Writing a novel, whether it’s 50,000 words or 100,000, is a marathon, not a sprint, as they say. No piece of software can change that reality. What they can do is provide a good valet or butler, always at hand with a tray or a freshly pressed coat. Think P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves with a dash of Star Trek’s Commander Data, and you’ll just about know what to expect.

Images are screenshots of my own copyrighted work, except for the last, purchased via subscription from Clipart.com.

August 27, 2021

Getting the Word Out

Long-time readers may have noticed that I don’t write too many social media or marketing posts. That’s because I’m actually terrible at marketing. Between work and my novels and the blog and my podcast, I don’t have a lot of free time. But if I’m to be completely honest, I also don’t choose to spend much of the little free time I do have on marketing, even though I know from other people’s experience that it would help me sell books. As a result, I don’t have a lot of surefire tips to share with other aspiring writers.

Another discouraging reality is the speed at which the Internet Age changes: Facebook is hot, then it’s everywhere, then it’s passé and replaced by TikTok, which next year will no doubt give way to something else. It’s a full-time job just keeping up, never mind leaping ahead of the curve. And the more entrenched a writer becomes in one community, the harder it is to pick up and move to another, where the old relationships must be rebuilt.

That said, after nine years of publishing fiction, I have learned a few things about what works and what doesn’t. Since this blog goes beyond interviews with other authors (enjoyable as those are), news about my ongoing projects, and historical tidbits to include publishing, media, and marketing, I thought I would take today to mention some of the insights I’ve acquired.

1. Produce a good book.

Without this step, you have nothing to sell, yet it’s the one budding writers pay the least attention to. The joy of finishing is extreme, and I revel in it as much as the next person, but it’s a rare book that succeeds without extensive critiquing and rewriting. This is as true of novels being sent to a literary agent for representation as for those destined for self-publication in any form. Be prepared to write draft after draft before a first novel is done. After that, the process gets easier, but multiple revisions are still required to make a book sing.

Without this step, you have nothing to sell, yet it’s the one budding writers pay the least attention to. The joy of finishing is extreme, and I revel in it as much as the next person, but it’s a rare book that succeeds without extensive critiquing and rewriting. This is as true of novels being sent to a literary agent for representation as for those destined for self-publication in any form. Be prepared to write draft after draft before a first novel is done. After that, the process gets easier, but multiple revisions are still required to make a book sing.Once you finish the writing, your project will need competent copy editing (and yes, most of the time, you get what you pay for), production, cover design, and e-book formatting. Only then should the question of marketing even arise.

2. Make use of existing contacts.

Sad but true: nothing beats a built-in audience. The journal I edit has acquired 2,500+ followers on Facebook and Twitter with posts that rarely exceed one per month. Why? Because people already knew about it. It took a decade to build that audience outside of social media, but once built, it transferred without so much as a hiccup.

For writers starting out, that means emphasizing local events, like-minded friends, neighbors, and relatives. I know authors who have sold books through their hairdressers, and more power to them. I had some luck with my local libraries and the Rotary Club, although my best audience is other scholars in my field (the ones who rightly assume I don’t distort history in the service of fiction, although I have encountered a few skeptics). The advantage of the Internet Age is that everything is international, but that means billions of people trying to connect at the same time. The noise level alone tends to drown those starting out, although worldwide availability pays off in the end.

For writers starting out, that means emphasizing local events, like-minded friends, neighbors, and relatives. I know authors who have sold books through their hairdressers, and more power to them. I had some luck with my local libraries and the Rotary Club, although my best audience is other scholars in my field (the ones who rightly assume I don’t distort history in the service of fiction, although I have encountered a few skeptics). The advantage of the Internet Age is that everything is international, but that means billions of people trying to connect at the same time. The noise level alone tends to drown those starting out, although worldwide availability pays off in the end.3. Focus your efforts.

This extends from the point raised above: that social media change faster than haute couture fashion. There’s no hope of remaining on top of everything, but if you avoid social media altogether, you’re unlikely to get out of your own local box.

The solution is to pick one or two things you can commit to on a regular basis. For me, it’s my blog (steady, every week), Facebook (3–5 times a week with selected groups), and Twitter (same as Facebook with the addition of #1linewed—a group effort that invites writers to share one line of a work-in-progress that includes a word set by the coordinator each week; search for the hashtag to see it in operation). And, of course, my podcast interviews, which post 1–2 times a month and which I lucked into back in 2012, when podcasting was up-and-coming. Alas for others, podcasting is everywhere now, so if you pursue it, go with an established group like the New Books Network rather than starting out on your own.

For you, it may be TikTok videos or Instagram or something entirely new. The point is to try out various options until you find a half-dozen or so you like enough to keep up with them, then go for it.

4. Forget about e-mail lists.

I don’t mean this literally. If you have a group of trusted friends or avid readers who want to find out when each of your books sees the light of day, by all means let them know! That’s part of point 2, using the connections you have. My publisher sends press releases to people who sign up for them, and I forward those to friends and neighbors who have said they want to stay informed.

But I no longer bother with newsletters myself. Instead, I contribute to the group posts my writers’ coop produces. I can’t tell you how many times a week I’m inundated with unwanted “news” because someone got hold of my e-mail address and signed me up without my permission (which is illegal, by the way). I usually don’t bother to unsubscribe, because I prefer not to upset authors I may want to interview one day. I don’t read the newsletters, though, and seeing them irritates me. You’ll still see advice to keep lists of e-mail addresses in various author marketing venues, but think about it: who under 50 even checks their e-mail regularly these days?

5. Try book teasers instead.

This advice assumes you have an artistic sense, an understanding of fonts and copyrighted images, experience with publishing software, and an ability to write dramatic lines. If you don’t, find someone who does. But if you do, these are a lot of fun to create and give readers a sense of your book. They pull people in without being a hard sell, which is the secret to marketing in general. And you can rerun them on social media in sequences, providing useful memory joggers for those who may be interested but distracted by the many other calls for their attention.

A similar approach—although I’ve never tried them—involves video trailers. My sense is that these work best if you already have an online presence and want to expand it. The technical demands are higher than those of book teasers, and there is more competition for eyes on a site like YouTube, whereas on Twitter and Facebook things flash past too quickly for anything with motion in it. YouTube also switches from one video to another in ways that make it hard to stay in touch with a single author even if you know who to look for. But other sites may be easier. If your mind naturally turns toward short videos, it would be worth experimenting to see what works for you.

6. Help other writers.

There is, of course, a danger in being caught up in social contexts made up solely of authors shouting their wares to other authors. But authors are also readers, and they have high standards for what they embrace. They can leave wonderful reviews, tout you on their sites, interview you, endorse your books—in return for sharing the publicity, which helps them too. And in my experience, most authors are wonderful people. Sure, some refuse to help, but many love to assist those starting out. If nothing else, it’s good karma, and we can all use a bit of that.

7. Keep writing.

It takes time to establish a reputation for producing good work, as noted above, as well as time to master the craft of writing. Once you do find readers, they will hope for more than one book. And with so many other prospects out there, you want to hook their attention while you can, so they will come back again and again. The only way to ensure that is to keep producing great books for them to read. Or, to paraphrase a well-known saying, “a writer’s greatest asset is her backlist.” So whatever happens, don’t give up.

In the last nine years, I have published eleven well-regarded novels, produced well over 100 podcast interviews, written 400+ blog posts, and seen my blog readership go from 100 to 11,000 a month. Even so, I’m still waiting for my annual book sales to get out of the triple digits.

Some people would probably advise me to quit, but why would I? I don’t write to sell books; I write because I love watching and recording the developments in my fictional world. Sharing the results with others is just the icing on the cake. And if anything I’ve written here helps you, so much the better.

There are other avenues to get the word out that I haven’t mentioned, of course. Feel free to share your tips and suggestions in the comments below.

Images from various sources, many previously published on this blog (and attributed in the original posts) and all either purchased via subscription, copyrighted by myself, or sent to me for distribution (the blog award).

August 20, 2021

Interview with Michelle Gable

It’s probably fair to say that Nancy Mitford and her sisters are not quite the household names in the United States that they are in the United Kingdom—and were, even during my childhood there. Too bad, because they were a fascinating family who participated (on all sides) of the twentieth century’s two great conflicts—the rise of communism and the Second World War.

It’s probably fair to say that Nancy Mitford and her sisters are not quite the household names in the United States that they are in the United Kingdom—and were, even during my childhood there. Too bad, because they were a fascinating family who participated (on all sides) of the twentieth century’s two great conflicts—the rise of communism and the Second World War.Michelle Gable knows all about them, and they star in her latest novel, The Bookseller’s Secret . Nancy, in particular, emerges from her period working in the Heywood Hill bookstore with experiences that will no doubt surprise many readers, as well as a manuscript that will launch her into literary celebrity. Read on to find out more.

You mention in your Author’s Note that you have long wanted to write a novel about Nancy Mitford. What is it about her and her family that made you yearn to fictionalize their story?

I’ve adored Nancy Mitford since reading The Pursuit of Love … probably back when I was in college! I knew the novel was based on her family but didn’t fully appreciate the full breadth of the Mitford craziness until I picked up The Sisters by Mary S. Lovell about twenty years ago.

I could yammer for hours about the mind-boggling Mitford girls but, in short, Nancy was one of six beautiful sisters (and one lonely brother): Nancy the novelist, Pamela the countrywoman, Diana the Fascist (and “most hated woman in England”), Unity the Hitler confidante, Jessica the Communist, and Deborah the Duchess. The Mitford girls were so notorious that their mom often “joked” she got nervous whenever a headline began, “Peer’s daughter…”

This book focuses on a specific time in Nancy’s life, between 1942 and 1945 (although you do tell us what happens to her beyond that). Why zoom in on that period of her life?

Nancy lived a long and often complicated life, so it was necessary to zero in on one time period. When tossing around ideas for this book, my agent suggested I write about Nancy’s time at the Heywood Hill bookshop in London, in the 1940s. I love any novel set in a bookstore, as well as new “takes” on the World War II genre, so this seemed like a perfect fit. Even better that I was struggling with my fifth novel, and Nancy was struggling with her fifth while she was working at the shop. She ended up publishing The Pursuit of Love shortly after the war ended up, and it made her a star.

The Bookseller’s Secret is not, however, only a tale of the 1940s. Tell us about Katharine Cabot and why you decided to tell her story in parallel with Nancy’s partially fictional one.

All my books have dual timelines—I like the challenge! Also, I’m forever intrigued by the connections and similarities between past and present.

Unlike the characters in the historical portions of the novel, Katie is entirely fictional. While we have vastly different backgrounds, Katie does share much of my writerly angst. Through Katie, I worked out many of my own career frustrations, to the point my agent and editor asked me to please tone it down!

In the book, Katie is a struggling writer who takes a break from her tumultuous personal life to visit her college roommate in London. She’s also hoping for some writerly inspiration. Katie’s friend lives in Mayfair, around the corner from the famed Heywood Hill bookshop, where, as I mentioned, Nancy Mitford worked during the war. People think of Nancy Mitford as being from a titled, upper crust family, which she very much was, but she was constantly in need of money. The Mitfords were a crumbling sort of gentry. In the novel, Katie is shocked to discover this tidbit and it’s the bookshop that unites these disparate characters and time periods.

Katharine, when we first encounter her, is recovering from one of those dinner parties that are excruciating to participate in but funny to read about later. What do we find out about her and her issues in this early scene?

That she has a lot of them! To name a few: she and her fiancé have broken up, she’s struggling with her writing career, and she has a deep inferiority complex about her sister and is vaguely “scared” of several family members. Basically, she’s looking to fly under the radar at Thanksgiving dinner but is instead thrown into the spotlight.

She’s also getting over a long relationship with Armie. She flees to London and soon runs into Simon Bailey. How would you compare and contrast these two guys?

Armie is a striver and very competitive. He comes from an immigrant family and feels added pressure to “succeed.” Despite their competitiveness, there’s a huge amount of comfort and respect between Katie and Armie because they’ve known each other for so long.

Simon is the sexy new thing but, compared to Armie, he’s a bit more laidback, at times awkward, despite his good looks. Unlike Armie, Simon pursued a career he was passionate about, without much thought to income, even though he certainly did not grow up with a lot of money. Armie comes from a tight-knit family, whereas Simon was raised by a single mom who has many personal problems.

The two men are pretty dissimilar, and I think this is what wakes Katie up to the idea that perhaps breaking up with Armie wasn’t only the right thing for him, but also for her. He was the literal boy next door, and she viewed him as an ideal partner, mostly because she didn’t really allow herself to consider otherwise.

It’s through Simon—and a chance encounter with the bookseller of your title, recommended to Katharine by her friend JoJo—that the past and present threads intertwine. Can you tell us a bit about those connections?

Because I made Katie Nancy-Mitford-obsessed, it was so easy to have her stumble into that shop and want to dig deeper. I would’ve done the same! Writers are notorious for going down research rabbit holes, and this innate desire helps connect Katie to the past.

Do you already have another novel underway?

Though I vowed no more WWII novels, I couldn’t help myself! My next book will take place in Rome, near the end of the war. It’s based on a woman who created propaganda to feed to the Germans and is an exploration of female friendship as well as how misinformation not only affects those receiving it, but those creating it.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Michelle Gable is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of A Paris Apartment, I’ll See You in Paris, The Book of Summer, and The Summer I Met Jack. Her latest novel, The Bookseller’s Secret, came out with Graydon House on August 17, 2021. Find out more about her and her books at https://michellegable.com.

Photograph © Joanna DeGeneres. Reproduced with permission.

August 13, 2021

Happily Ever After

At one point late in Zara Raheem’s lovely debut novel, The Marriage Clock, the heroine’s father explains: “Leila, if you want to be happy, you must realize that there is no such thing as love before marriage. True love exists only after marriage. Simple as that.”

As someone who at this point has been married far longer than she was single, I understand exactly what Leila’s father means—although she, at twenty-six, cannot. It’s the philosophy that powers my novels—especially the Legends of the Five Directions series, where all the major characters either endure or benefit from arranged marriages. Yet it runs counter to the belief system of modern romance literature in all its forms, including the Bollywood films that are Leila’s life guides of choice.

My point is not to endorse arranged marriage per se. Zara Raheem does a wonderful job of exposing the downsides of such contracts even as she reveals their upsides through the story of Leila’s parents. In my novels, too, some arranged marriages work well, but others are torture—in the cases of Maria and Solomonida leaving residues of fear and self-doubt that haunt them for years. Maria’s story comes out in The Vermilion Bird. How Solomonida handles that legacy is the topic of next year’s Song of the Sinner, now in the final stages. The matching character in Raheem’s novel is Tania, who married to please her parents at eighteen and divorced four months later, only to discover that no family in her ethnic/religious community will accept a divorced woman as a bride, whatever her story.

But the deeper point made by Leila’s father is, I think, worth highlighting. Whatever we read in romance novels, see in films or on TV or social media, getting a proposal of marriage is not, in fact, the Happily Ever After ending portrayed in the media. A wedding marks not the end but the beginning of a relationship, the long and difficult but oh-so-rewarding journey toward a shared future with another person who will become more knowable over time yet never completely predictable. That’s half the excitement of marriage: that even after fifty years a spouse can surprise you. Set that against the comfort of being with someone who still sees you as you were at 20 or 25 or 30—whenever you first met.

That’s what I want for my characters. That’s why I love to write about marriage, which is so much more interesting to me than hormones and often silly arguments that could be resolved if one person just said what s/he thought to another. That’s why I put them through hoops, force them to grow, before I reward them with love from a partner who has also made an effort to deal with his or her weaknesses. That, too, doesn’t mark the end but only a stage in the process—one reason, perhaps, why my characters appear again and again.

But, you may ask, where’s the conflict? Conflict is, as others have noted, the life blood of fiction. Think about it, though. If characters are well rounded, conflict between them naturally occurs. Put two fully formed human beings in a room, give them a reason to care passionately about a joint enterprise, and conflict is inevitable. The issues are how well a couple handles its differences, how quickly each partner recovers, and how stubbornly they fight on. The last often reflects personality and commitment, but the others can be learned. And by the time your characters have made some progress, they’ll have reached the end of the book.

Fiction thrives on drama, and an arranged marriage definitely ups the ante on a relationship. That’s another reason, besides historical authenticity—most marriages in the sixteenth century were arranged—that I imposed it on my characters in the Legends series. Although few of my Songs of Steppe & Forest heroines end up in arranged marriages, fighting the expectation or overcoming the results of such a connection drives most of them, one way or another.

It’s clear that Zara Raheem uses the threat of an arranged marriage to push her heroine forward for similar reasons. And the results are hilarious, from the Muslim speed-dating event (improbably hosted in a bar) to the tone-deaf prospect who launches into Bollywood songs in the middle of a café and the uniquely twenty-first-century problem of finally falling for a guy only to be ghosted the next day. Leila’s mother, desperate to secure her daughter’s happiness as she understands it but also to spare herself the agony of accusations that she has failed as a mother; the helpful but competitive aunties; the perfect cousin and hapless would-be grooms; the matchmaker who picks just the wrong match; the supportive if often clueless college friends; the trip back to the homeland and a large family of strangers with different views on just about everything; and Leila’s growing understanding of herself and what she really wants in life and, eventually, a partner—the novel is filled with entertaining encounters, evocative descriptions, and sympathetic portrayals.

But when all is said and done, The Marriage Clock is not really about marriage. It’s about blending cultures, weighing the demands of family against the needs of self, understanding the meaning of love, and learning how to take a stand without offending people you care about. And those are problems every one of us can relate to, whatever we think of Happily Ever After.

Let me note that when I say “marriage,” I have in mind any lifetime commitment. It is true that proclaiming said commitment to all and sundry, in addition to the legal ramifications of tying the knot, do impart a certain sense of finality that both supports the couple in its efforts and spotlights problems as they arise (leaving socks around the room for a week is cute, but “forever” feels very different). But I recognize that not everyone everywhere has that option, and those relationships can be just as interesting and as complex as any other.

Images purchased through subscription from Clipart.com.

August 6, 2021

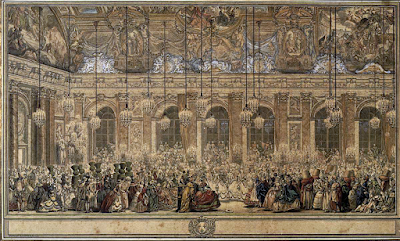

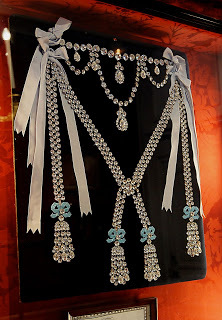

The Necklace That Brought Down a Monarchy

A few years ago, Martha Hoffman, founder and owner of Cuidono Press, sent me Precious Pawn, one of her historical fiction titles set in prerevolutionary France. The topic interests me, so I had every intention of reading it, but life got in the way and I never quite got around to it—until the author’s next book came out a few months ago. Then I did read Precious Pawn, a fictional rendition of an actual eighteenth-century memoir discovered by the author, Mary Martin Devlin, in an archive. In this novel, Diane de Fautrière, the young (as in fourteen-year-old) and beautiful daughter of an ambitious but impoverished nobleman, catches the eye of King Louis XV of France before losing out to Madame de Pompadour. I won’t say more, except that this painting of a court ball in 1745 captures the moment when her fate takes an unexpected turn.

Diane is in every way a young woman of her times, and that setting—the luxurious and often scandalous court at Versailles—is fascinating. Even more fascinating from this reviewer’s perspective is the novel that follows, The La Motte Woman . Its heroine, born only about twenty years after Diane, couldn’t be more different. As I read Jeanne’s fantastical but mostly true story (Jeanne, it soon becomes clear, is not a reliable narrator of her own life), I kept thinking of Becky Sharp, the anti-heroine of William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair—only to discover during my interview with the author for New Books in Historical Fiction that indeed, Thackeray based his character on the real-life Jeanne de la Motte. Read on to find out more about the story—and do listen to the interview, which is a lot of fun and includes a discussion of the first book. But the most fun comes from reading the novel: Jeanne is a character for the ages, and I guarantee that by the time you reach the end, you—like her former lover, Beugnot—will rejoice that she managed to escape the debacle she created.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Jeanne de St.-Rémy has a grudge against the world. Born into the French royal family—if admittedly by a somewhat labyrinthine route—she spends years of her childhood so disinherited and ignored that at the age of six, she is begging in the streets of Paris. A lucky accident brings her to the attention of the Marquise de Boulainvilliers, who adopts the little waif, raises her as a daughter, and helps her prove her claim to be considered a relative of King Louis XV through a legitimized descendant of the previous royal family, the Valois. The marquise even helps Jeanne secure a pension, but Jeanne remains unsatisfied. She will settle for nothing less than full acceptance into the court at Versailles.

Through a series of affairs and a forced marriage to Nicolas de La Motte, who becomes Jeanne’s loyal partner if not the husband of her heart, Jeanne ploughs through all obstacles on her path. Her greatest conquest is the Cardinal-Prince Louis de Rohan, a high-ranking aristocrat whose campaign to regain his influence with the new king, Louis XVI, is repeatedly challenged by a hostile Marie Antoinette. When Jeanne learns of a magnificent diamond necklace, a creation so elaborate and enormous that its purchase price would bankrupt a nation, the stage is set for a scandal that will bring down the very monarchy Jeanne is so desperate to enter.

With a keen eye and a vivid appreciation for detail, Mary Martin Devlin creates, in The La Motte Woman (Cuidono Press, 2021), an indelible picture of how three clashing obsessions—Jeanne’s quest for the validation of her heritage, Rohan’s yearning for his appointment as prime minister, and the jewelers’ determination to produce a unique and, in their minds, perfect work of art—intersected to destroy the reputation of Queen Marie Antoinette, with catastrophic results for the French monarchy as a whole.

Images: Charles-Nicolas Cochin, A Masked Ball Given to Mark the Marriage of the Dauphin (1745); The Queen’s Necklace (Reconstructed), photograph © Jebulon—both public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

July 30, 2021

Mysteries Galore

It’s no surprise to anyone that the mystery genre, both contemporary and historical, has a large following among readers. Indeed, even novels not classified as mysteries work best if the authors keep readers in suspense about what drives the obsessions of individual characters or how a hero(ine) will succeed in defeating the main antagonist and achieving his or her goals.

But although I try to maintain elements of mystery in my own novels, that is not the focus of this post. I also love to read a good generic mystery, whether it revolves around murder or another, less extreme crime. I have my favorite authors, at times featured on this blog—classic writers like Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie but also Elizabeth Peters, Laurie R. King, Rhys Bowen, and Deanna Raybourn, to name a few. I also enjoy crime writers who don’t have the muscle of big publishing houses behind them. P.K. Adams, with whom I am now co-writing murder mysteries of my own, is one example. Here are three others I’ve read recently or am currently enjoying who are published by smaller presses.

In the interests of full disclosure, I found out about all these authors on Facebook (room for another post there), so I know them in a rather casual way. But I make it a point never to recommend a book I didn’t genuinely enjoy, so in that sense these novels are no different from any other, except in the way I learned of their existence. The only one who even knows I bought her books is A. E. Wasserman, and that’s because I plan to interview her for New Books in Historical Fiction whenever I can clear some space in my schedule.

Sheila Lowe,

Poison Pen

(Write Choice Ink, 2021)

Sheila Lowe,

Poison Pen

(Write Choice Ink, 2021)This recently revised and re-released novel, originally published in 2007, kicks off the Claudia Rose series (currently eight books) with a bang. Claudia works as a forensic handwriting analyst, often testifying in court, so it’s not an enormous stretch when she’s called in to verify a suicide note left by Lindsey Alexander, an utterly self-centered and widely disliked publicist known to Claudia. The suicide note is written in printed capitals on a fresh piece of paper, not Lindsey’s usual style at all, but without a printed document to use for comparison, Claudia struggles to fulfill her task.

Then the man who hired her to prove the suicide note a fake winds up severely battered in Lindsey’s apartment, and Claudia is the one who finds him minutes after the attack. In conjunction with LAPD detective Joel Jovanovic (pron. Yo-VAN-o-vich), Claudia gradually gets drawn into both the twisty yet ultimately satisfying plot and to Joel himself, all the while trying to stay one step ahead of the killer.

Saralyn Richard, A Palette for Love and Murder (Black Opal Books, 2020)

I’m halfway through this one and loving it, so I just bought the first book as well (Murder in the One Percent [2018]). As a result, I’m a bit out of sequence, but so be it. Both of these are set in the Brandywine Valley in southeastern Pennsylvania, an area I know well, and that’s definitely part of the fun. Both also feature Detective Oliver Parrott, a young (20s something) African-American officer on the Brandywine police force a little bewildered by the opulence of his new work environment.

In this second book, Parrott is investigating the theft of two paintings by Blake Allmond, an artist in his fifties from an old and wealthy Pennsylvania family on the brink of achieving international recognition. Allmond shows up dead in New York City before Parrott even has a chance to interview him, and although the murder is not Parrott’s case, it certainly ups the ante. Parrott is a thoroughly likable and sympathetic character, as is his new wife, Tonya—a Navy SEAL just returned from Afghanistan and suffering from PTSD. I can’t wait to find out how this case plays out and to follow the series from now on.

A. E. Wasserman,

1884: No Boundaries

(Archway Publishing, 2015)

A. E. Wasserman,

1884: No Boundaries

(Archway Publishing, 2015)This, the only historical fiction writer in the trio, is the one I plan to interview for my podcast. For that reason, she sent me this book, although I purchased two others—the delightful novella The Notorious Black Bart: The Journey Back, 1883 and the latest, 1888: The Dead and the Desperate, which I have yet to read. But the series begins here, with the twenty-one-year-old Lord Langsford entertaining his boyhood friend Heinrich von Dieffenbacher, on a visit with his father from Germany. Langsford, despite his recent marriage to the beautiful Regina, has a secret that he conceals even from Heinrich, an eyewitness to one of its early manifestations: Langsford’s only deep, heartfelt passion was for someone he knew from their all-male boarding school (possibly Heinrich himself, although the identity of Langsford’s love has yet to be revealed). But homosexuality, a term not even invented in the 1880s, is still a crime under British law as well as a moral abomination in the eyes of society, including Langsford himself. Hence his early marriage—a vain attempt to control and rechannel his desires.

Meanwhile, Heinrich falls madly in love with a London shopgirl, a match that would be barred to him as the son of a count, even if his father had not chosen to observe a family tradition dating back to the time of Charlemagne that promises Heinrich to the Catholic Church. The moment Heinrich’s father discovers the unwanted attraction, he hauls his son back to Germany without giving Heinrich a chance to say goodbye. But it’s when Heinrich tries to escape his heritage and return to London that he becomes involved in a murder and assassination plot that only Langsford can unravel.

These novels straddle the line between murder mystery and suspense: sometimes we know the identity of the murderer but not the motivation or the context; other times the author chooses a more traditional path, with an investigation that uncovers an unsuspected but plausible villain. But what also distinguishes them—in addition to Langsford himself, a complex and intense Sherlock Holmes type—is their placement in history writ large. Whether it’s a planned assassination of Otto von Bismarck, anarchist bombings by Irish radicals, or politicking to manipulate transcontinental railroads, the background to the books informs and highlights the personal issues of Wasserman’s complex characters.

July 23, 2021

Bookshelf, Summer 2021

Here we are, close to the middle of summer, so I thought this would be a good time for another bookshelf post. I’ve been reading nonstop, so many of the books that were originally on my list have already moved through the system, so to speak, giving rise to blog Q&As and New Books Network podcast interviews that you can find by checking the month-by-month archive on the right, beneath my book covers. But between now and the official beginning of fall around September 21, I still have quite a few titles on my list.

Jai Chakrabarti,

A Play for the End of the World

(Knopf, 2021)

Jai Chakrabarti,

A Play for the End of the World

(Knopf, 2021)Given my repeated complaints that the major publishers never seem to tire of books set during World War II, it may seem odd that I have three such books on my shelf at the moment. But each of them has a unique approach to the subject that appeals to me. Jai Chakrabarti’s A Play for the End of the World, due for release on September 7, begins in a Warsaw orphanage in August 1942, four days before the staff and children are evacuated to Treblinka, where all but two of them will perish. The directors of the orphanage, who can already anticipate what will happen, try to prepare the children by staging a production of Rabindranath Tagore’s The Post Office, a play about death and how to prepare for it. Thirty years later, those two survivors are invited to restage the play in Bengal, and through the prism of their journey—in particular, Jaryk’s, the younger former orphan who follows to reclaim his friend’s ashes—we see not just the effects of what they went through in 1942 but all the years between. In this way, the book is less about the war than about the postwar experience of those who lived through it. If all goes well, I’ll be hosting a written Q&A with Jai Chakrabarti in mid-September.

Mary Martin Devlin,

The La Motte Woman

Mary Martin Devlin,

The La Motte Woman

(Cuidono Press, 2021)

Of all the books on the list, this is the only one that’s already out—just last month—and it’s a gem. Set before the French Revolution, it follows the career of a real-life woman, Jeanne de La Motte-Valois, who was reportedly the inspiration for William Thackeray’s Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair. Born into poverty as the descendant of a legitimized son of King Henri II, Jeanne is determined to reclaim the position to which she believes she’s entitled. To that end, she manipulates a series of lovers, most notably the powerful Cardinal-Prince Louis de Rohan, and launches a scandal that ultimately sweeps up Queen Marie Antoinette and contributes directly to the overthrow of the monarchy in 1789 and the queen’s execution four years later. You can hear us talking about it in a couple of weeks on the New Books Network.

Michelle Gable, The Bookseller’s Secret

(Graydon House, 2021)

This is the second book set, at least partially, during World War II—much of it also in 1942—but it takes a quite different approach from Chakrabarti’s. This dual-time story contrasts the life of a fictional contemporary author with one big hit and a bad case of writers’ block to the wartime experience of the real-life Nancy Mitford, who after four not very successful novels is supporting herself by working at a London bookstore. She’s also tasked with spying on various members of the French government in exile, as a result of which she forms a long-term relationship with a French count that contributes to the breakup of her unsatisfactory marriage. The focus is not, however, on the war so much as the process by which Nancy breaks out of her doldrums to write The Pursuit of Love, the novel that makes her famous and mirrors in interesting ways the contemporary half of the book. The Bookseller’s Secret is due to release on August 17, so check back around the 20th to see if Michelle Gable has answered my questions.

Gill Paul, The Collector’s Daughter

(William Morrow, 2021)

I’ve been a big fan of Gill Paul’s novels ever since I read The Lost Daughter, her 2019 reimagining of how the life of Grand Duchess Maria—one of the four daughters of Emperor Nicholas II—might have worked out if she had not been assassinated by the Bolsheviks in 1918. Jennifer Eremeeva conducted that interview for the New Books Network, and I hosted a written Q&A here when Gill’s next novel, Jackie and Maria, came out last year. But I was determined to talk to her in person, and that will happen in conjunction with this year’s release, due on September 7, of The Collector’s Daughter. This beautifully written, thoroughly engrossing story focuses on Lady Evelyn Herbert—the daughter of Lord Carnarvon, who funded Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Eve, as she was known, harbored a desire to become an archaeologist and was present at the opening of the tomb. Indeed, she was the first person to enter the sealed chambers in three thousand years. But the novel begins and ends with Eve in her seventies, exploring the nuances of her long and happy marriage and how it withstood her increasing loss of memory, the result of strokes caused by a car accident in 1935. The book flips back and forth between Eve as a young woman and Eve struggling to recover from each setback, and in that respect it is truly a tale for the ages. Stay tuned for more information about our New Books in Historical Fiction conversation sometime in mid-September.

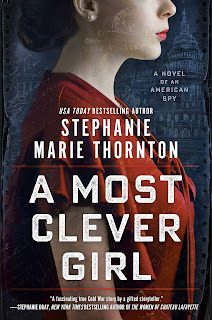

Stephanie Marie Thornton, A Most Clever Girl (Berkley, 2021)

Here is the third book connected with the 1939–1945 period, but it too is really about the postwar environment—the consequences of the war, if you like. Two American double agents, one operating in the Cold War world of 1963 and the other attempting to infiltrate fascists during World War II, find their loyalties tested as they balance the conflicting demands of love and country, the United States and the USSR. Even though the 1960s (and even the 1940s) are far removed from my area of interest as a historian of early modern Russia, the espionage and Soviet angles—especially given that both spies are female—are enough to draw me in. Thornton’s new book releases in mid-September, but I will be interviewing her on this blog toward the end of that month or in early October due to the number of other commitments I already have.