C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 10

July 1, 2022

Designer of Dreams

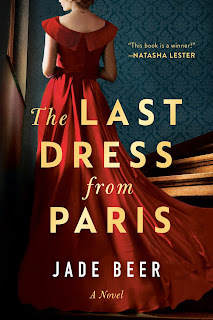

To paraphrase Sir Percy Blakeney in the 1982 BBC production of The Scarlet Pimpernel—still the best of the various versions of this classic, including the original novel—fashion never was my forte. I’m an academic by temperament and by training, so even if I did have the wherewithal to dress myself in haute couture gowns, it would both look and feel odd. Standing out in a crowd is one thing; appearing to have come from another universe something quite different.

To paraphrase Sir Percy Blakeney in the 1982 BBC production of The Scarlet Pimpernel—still the best of the various versions of this classic, including the original novel—fashion never was my forte. I’m an academic by temperament and by training, so even if I did have the wherewithal to dress myself in haute couture gowns, it would both look and feel odd. Standing out in a crowd is one thing; appearing to have come from another universe something quite different.But despite the choices I’ve made in my own life, I can appreciate a beautiful dress for the work of art that it is, and that applies especially to the mid-twentieth-century creations of Christian Dior. The gown in this gorgeous book cover is just one example.

Because he made his mark starting in 1947 and died ten years later, most of the images of Dior’s gowns are not yet public domain, although this collection of toiles (physical blueprints for planned gowns made out of cheap linen or cotton to test the structure of the dress) from the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris is one exception. In my most recent interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, the author Jade Beer talks about how an exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams (2019), which included a similar setup as well as many finished pieces—inspired her latest dual-time novel. Read on to find out more.

As always, the rest of this post first appeared on New Books in Historical Fiction.

London, 2017. Lucille will do anything for her beloved grandmother. So when Granny Sylvie volunteers to send her to Paris to retrieve a beloved Dior creation left in the city many years ago, Lucille accepts. Why not escape for the weekend, when home means dealing with her hostile, demanding boss and a mother so uncaring that she’s forgotten Lucille’s birthday for five years in a row? Not long after arriving in Paris, however, Lucille discovers that the one dress is actually eight, and two of those are missing, including the Maxim’s, which she was specifically tasked with bringing back to London. Soon she is searching all over the city, in the company of her new friends Veronique and Leon, while her boss screams his frustration over the phone.

This present-day story intertwines with one set in Paris in 1952, featuring Alice Ainsley, the young, newlywed wife of Britain’s ambassador to France. Alice’s wealth and her position in society require her to look and act the part of the perfect hostess. Who better to dress her for that role than Christian Dior, whose New Look is taking the fashionable world by storm? Alice soon becomes the envy of her insulated social set, but her apparently blissful existence conceals great insecurity and hurt. Her husband has lost interest in her since the honeymoon, and the couple only grows farther apart over time.

Jade Beer does a wonderful job of interweaving these two timelines, keeping us guessing as to how they connect well into the book. And the contrast between Lucille’s modern approach to life, even when it lets her down, and Alice’s more limited options, despite her apparent prosperity, reveal the vast gulf between the 1950s view of women and our own, as well as the subtle ways in which one generation’s choices influence those of the next.

Images: Photograph by Joe DeSousa of the Christian Dior Exhibit at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, 2017, CC0 1.0 universal public domain; photograph of the outfit known as the Bar Suit or the Maxim’s (after a restaurant in Paris favored by the avant-garde), 1947, from an exhibit held in Moscow in 2011 © shakko, CC 3.0, both via Wikimedia Commons.

June 24, 2022

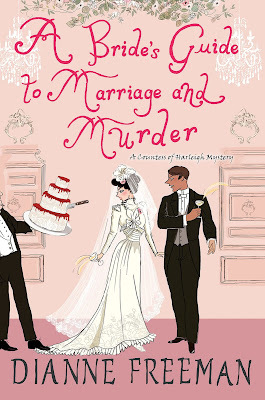

Interview with Dianne Freeman

I love historical mysteries, especially the cozy variety—even more when the author has a sense of humor in addition to great characters and twisty plots that make sense in the end but require a good bit of deduction to work out (or take me completely by surprise. So I was delighted to come across Dianne Freeman’s Lady Harleigh Mysteries, which do all those things with an aplomb that makes the writing look much easier than I know it to be in reality.

I love historical mysteries, especially the cozy variety—even more when the author has a sense of humor in addition to great characters and twisty plots that make sense in the end but require a good bit of deduction to work out (or take me completely by surprise. So I was delighted to come across Dianne Freeman’s Lady Harleigh Mysteries, which do all those things with an aplomb that makes the writing look much easier than I know it to be in reality.Better yet, Dianne agreed to answer my questions about her series. You’ll have to read fast if you’re going to get books 1–4 out of the way before A Bride’s Guide to Marriage and Murder appears next Tuesday, June 28, but by all means give it a try. You won’t be disappointed!

How did you come to write this series?

I wrote what I wanted to read. Historical mystery is my favorite genre, and I love a mystery that really pulls me into the protagonist’s life. An amateur sleuth serves that purpose beautifully because they’re really meant to be doing something else, not solving a crime. As for my protagonist and the historical era, I’ve long been fascinated by the transatlantic marriages between American heiresses and British aristocrats near the end of the nineteenth century. I wanted a slightly older character, so the story begins ten years after the wedding. Frances has more maturity and experience, but she’s still a bit of a fish out of water.

Your main character is Frances Wynn, Countess of Harleigh—who despite her English title is actually an American. How did she acquire her title, and what can you reveal about her personality?

Frances married into the title. As new money New Yorkers in the Gilded Age, Frances and her family didn’t stand a chance of breaking into Mrs. Astor’s society. Her mother, Daisy Price, decided to put Frances on the path of the earlier American heiresses and look for a titled gentleman with financial troubles somewhere in Europe who was willing to marry her daughter in exchange for a healthy infusion of cash.

She found Reggie Wynn, who was then heir to the Earl of Harleigh, and the exchange was made. For Frances, marriage to Reggie was a gamble, but remaining in New York meant becoming a spinster, or if she were lucky, marrying a man her father brought home from the office. She took the risk. I think this action alone tells you that Frances isn’t one to sit back and wait for life to happen. She likes to take care of those she loves and she likes to take charge of any matter that concerns her, though that often means she has to work her way around the rules that govern an aristocratic woman of that era.

And how does a countess get involved in solving a series of murders?

First, she was accused of one, and because she had no intention of spending any time in prison, she was highly motivated to find the real killer. The second murder happened just outside her garden gate. Frances suspected it had something to do with her sister, and her protective instincts came into play. Her investigations might have ended there if she hadn’t realized she was actually rather good at it. The fact that she could work with her next-door neighbor, George Hazelton, who was something of a sleuth himself, made every day an adventure. How could she give that up?

Her partner in these investigations is George Hazelton. What can you tell us about him?

George is the brother of Frances’ best friend, Fiona, and the third son of an Earl. This puts him in the awkward position of being an aristocrat without a fortune. He could marry into money, of course, but George chose to make his own way in the world. He studied law, and now does “something” for the government. We learn more about George with each book, so to avoid spoilers, he must remain mysterious for now. I can tell you he enjoys working with Frances.

This fifth novel opens with the most marvelous line: “Family, like a rich dessert, is a treat best enjoyed in small portions.” What’s going on in Frances’s life that makes her feel this way?

Thank you! She is getting married, which means bringing her family together. In this case, at her house. She loves them, but one member in particular has been in her home for too long. That would be Daisy Price, her mother. Daisy managed Frances’ life the last time she was single, and she doesn’t see why she shouldn’t do so again. Frances disagrees. When you add her father, her brother, and Aunt Hetty into the mix, it’s no wonder she wishes she and George had eloped.

This is a murder mystery series, so there must be a body. Set the scene for us, please. Who is the victim on this occasion?

The dearly departed is James Connor. He was an Irish immigrant who made an enormous fortune in the Nevada silver mines—owning them, that is. With his wealth and power, he’s used to getting his own way and has no qualms about bullying people to do his bidding. He has few friends, many enemies, and one man he’s actually feuding with—Peter Bainbridge. Connor and Bainbridge have kept their fighting to character assassinations. Both employ agents to spy on their foe and report any unseemly or embarrassing news to the papers. The public has been enjoying reading about the follies of these two powerful men for years. Though they came to blows once, their animosity would never lead to murder—would it? Another of Connor’s enemies might have murdered him, thinking Bainbridge would be blamed. Unfortunately, it’s Frances’ brother, Alonzo, who is caught with the murder weapon when Connor’s body is found.

The long-suffering Inspector Delaney, who has endured a good deal of what he sees as interference from Frances and George, is back in this book. How would you describe him?

Long-suffering is a good start. Delaney is a seasoned pro, capable of handling any murder investigation. Frances and George may get in his way, but they do come in handy. They have access to the aristocracy, who often refuse to speak with the police, and they don’t have to operate strictly within the law—both attributes Delaney takes full advantage of. He made it clear that his patience has its limits when Frances and George pushed him too far in A Fiancée’s Guide. They may be chastened, but Frances’ father, who arrives to torment Delaney in A Bride’s Guide to Marriage and Murder, is another story.

This novel just came out. Are you already planning another Countess of Harleigh mystery?

Yes, A Newlywed’s Guide to Fortune and Murder releases next year. This time Frances finds herself in the middle of an intrigue when she agrees to sponsor Lady Wingate’s niece, Kate, for a presentation to Queen Victoria. Since her husband’s death, Lady Wingate has been unwell and hasn’t left the house for months. Her friend, Lady Esther, is convinced one of the woman’s stepchildren is drugging her and tapping into her fortune. Kate isn’t above suspicion either. She’s about to enter high society and stands to gain an inheritance upon her aunt’s death. Hundreds of young ladies would kill to be in her shoes. Frances has to wonder if that’s exactly what’s happening. She, George, and Lady Esther join forces to flush out the villain and keep Lady Wingate from following in her husband’s footsteps—directly to the grave.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Dianne Freeman is the award-winning author of five historical mystery novels featuring Lady Harleigh—most recently, A Bride’s Guide to Marriage and Murder. Find out more about her at https://difreeman.com.

June 17, 2022

Happy Birthday to Us

Ten years ago this month, Five Directions Press published my—and its—first novel, The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel . Two weeks later, ten years ago almost to the day, I started this blog. And that November, I conducted my first podcast interview for New Books in Historical Fiction. So this is a year of anniversaries, for me personally and for two entities (my writers’ coop and my podcast channel) that have come to mean a great deal to me—and not only in terms of bringing my work to the world.

According to the wisdom of the Internet, the metal associated with a tenth anniversary is tin or aluminum. Compared to silver, gold, or diamonds, this always appeared to me a ho-hum choice, about which not much could be said except that it was better than paper. But, again according to the Internet, tin or aluminum stand for strength and endurance. That sounds better, don’t you think? So let’s go with that interpretation. Keeping anything going for ten years, especially as we mark the halfway point of the third plagued by Covid, seems well worth a celebration.

Anniversaries also invite retrospectives. While checking on dates, I reread that first post and was amused to see how relevant the questions I asked then still are, despite the many changes that have affected publishing and marketing in the last ten years.

Now as then, my nonfiction book still sells more copies in a year than all my novels (now numbering twelve) combined, lagging only during the worst year of the pandemic, when most college classes moved to Zoom. Social media still dominate marketing, although Instagram and TikTok are rapidly displacing Facebook and Twitter. With only so many hours in the day, I rarely have time to visit GoodReads or even Pinterest.

At the same time, the market for books has become even more crowded, further restricting opportunities to break out. The sense that more people are talking than listening has only increased. My sales were higher in 2012–2014, when I had only three books, than now, when I have four times that many. I still have my fans, I “own” the Amazon listings for 16th-century Russian fiction, but sales spike when I release a new title, stay higher than normal for a month or two, then drop off once more.

One bright light has been the New Books Network, which got off to a slow start in 2007, was still little known when I joined in 2012, but since then has grown steadily. In September 2021, a combination of people being stuck at home eager to produce podcasts and people stuck at home eager to listen to folks chatting about books doubled the number of downloads in just thirty days. We are now big-time, with an average of three to five million episodes served each month. I’m glad to be a part of that, and I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all the authors who’ve spoken with me about their work, all the publicists who helped set up interviews, and of course, the many, many people who tuned in to listen.

One bright light has been the New Books Network, which got off to a slow start in 2007, was still little known when I joined in 2012, but since then has grown steadily. In September 2021, a combination of people being stuck at home eager to produce podcasts and people stuck at home eager to listen to folks chatting about books doubled the number of downloads in just thirty days. We are now big-time, with an average of three to five million episodes served each month. I’m glad to be a part of that, and I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all the authors who’ve spoken with me about their work, all the publicists who helped set up interviews, and of course, the many, many people who tuned in to listen.

Another bright light is Five Directions Press. We began as a writers’ group of three who decided, because of our particular blend of skills, to take a chance on producing our own work as a coop rather than brave the choppy seas of traditional agented publishing. At one point, we had more than doubled our numbers; we still stand at five, all actively writing. And although no one has yet cracked the marketing code and put out a bestseller, we have learned a huge amount about how the process works, what does and doesn’t yield results. More important, we have supported one another through the ups and downs of writing, offering comments, contributing to the newsletter and social media accounts, supplying reassurance during the down times and congratulations when things go well, and talking up one another’s books whenever possible. As I say in every acknowledgments to one of my novels, I can’t imagine the last ten years without Ariadne Apostolou, Courtney J. Hall, Claudia H. Long, Gabrielle Mathieu, Joan Schweighart, and Denise Allan Steele.

Then there is, of course, this blog. If you’d asked me, back in 2011, whether I would ever start a blog, let alone post once a week—without fail—for ten years, I would have laughed in your face. But it’s been a wonderful learning experience, not just in patience and perseverance but also in achieving comfort with talking about my own writing and life as well as structuring conversations with other authors. For all the high-intensity appeal of social media, I much prefer the greater space offered by the blog format. Perhaps it’s a generational thing; perhaps it’s my natural affinity for the much longer novel format. But either way, I like the challenge of finding a topic, stripping it to its essence, and figuring out how to present the central issue in a way that readers need not be specialists to appreciate. It’s a bit like teaching, without the requirement of grading—something I never liked. It also lets me interact with far more of my fellow writers than I could fit into my schedule for the New Books Network.

Last big question: in the end, would I make the same choices again? Retrospectives are always deceiving, because we cannot return to the state of knowledge we did (or did not) possess at an earlier time, but on the whole, my answer would be yes. It would be lovely, of course, to have a contract with a Big Five publisher—especially if (a far from guaranteed result) it meant funding my retirement with royalties from my novels. But I don’t write to sell books; I write because I love to tell stories about this long-past society that is so unfamiliar to most Americans and even many Europeans, yet so full of dramatic possibility and tension. Having written the books for my own pleasure and worked on them with my friends at Five Directions Press, I see it as a simple decision to share them with those who enjoy them. I can do that because after almost thirty years in publishing, I know how a professionally produced book should look, and the coop makes skills like cover design affordable. It’s not a model that would work for everyone, but it works for me.

So let’s raise a glass to ten wonderful years, with hopes for many more to come!

Images © C. P. Lesley, Colleen Kelley (Five Directions Press logo), and the New Books Network (New Books in Historical Fiction logo).

June 10, 2022

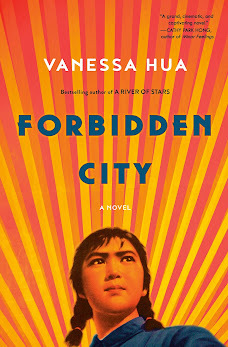

Interview with Vanessa Hua

When Vanessa Hua’s publicist pitched

Forbidden City

, I looked at my schedule, already jam-packed for the summer, and hesitated. But as a lifelong student of Russia and the Soviet Union, as well as a novelist fascinated by China’s long history, in the end I couldn’t resist. I devoured the book in three days, sent in my questions for Vanessa Hua, and received her answers within forty-eight hours. So clearly, this pairing and this interview were intended to happen.

When Vanessa Hua’s publicist pitched

Forbidden City

, I looked at my schedule, already jam-packed for the summer, and hesitated. But as a lifelong student of Russia and the Soviet Union, as well as a novelist fascinated by China’s long history, in the end I couldn’t resist. I devoured the book in three days, sent in my questions for Vanessa Hua, and received her answers within forty-eight hours. So clearly, this pairing and this interview were intended to happen.And in a happy side note, I was paging through the New York Times Sunday Magazine a few weeks ago, and there was Vanessa Hua, talking about the Chinese concept of mamahuhu and what it means for her family. I immediately thought, “Wait, I know her!”

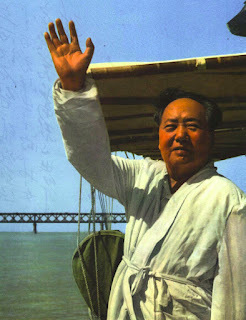

You’ll have to find that column yourself, but read on to learn more about her wonderful novel about Chairman Mao, his maneuvering against President Liu Shaoqi, the Cultural Revolution that resulted, and Mao’s love of ballroom dancing—all told from the perspective of an idealistic young woman.

What drew you to writing a novel about the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and how did you decide to approach your subject from this particular angle?

Years ago, a teasing glimpse of black-and-white documentary footage intrigued me: Chairman Mao surrounded by giggling young women in tight sweaters. As I would learn, the peasant-turned-revolutionary was a fan of ballroom dancing—and young women, who partnered with him on the dance floor and in the bedroom.

When I looked for more information about these ingenues, I couldn’t find much. In his memoir, Mao’s doctor said, “To have been rescued by the Party was already sufficient good luck for such women. To be called to the Chairman was the greatest experience of their lives. For most Chinese, a mere glimpse of Mao standing atop Tiananmen was a coveted opportunity, the most uplifting, exciting, exhilarating experience they would know … Imagine, then, what it meant for a young girl to be called into Mao’s chambers to serve his pleasure!”

I suspected—I knew—the relationships had to be more complicated—especially for those who he kept on as his “confidential clerks.” For example, Zhang Yufeng was eighteen years old when she met the Chairman at a dance party—in the liminal years between girl and woman, and so young by comparison to Mao, then in his late sixties. In time, she would handle and read aloud the reams of documents that the Chairman commented upon daily. Toward the end of his life, as his speech became garbled by illness, she served an important role, interpreting what he said. People who wanted to meet with Mao had to go through her. How did she survive the political intrigue all those years? What unacknowledged role did she have in making history?

My protagonist, Mei, is emblematic of the millions of impoverished women who have shaped China in their own ways, yet remain absent from the country’s official narrative. I wanted to write a story from the perspective of someone relegated to the margins, yet who would have as much intelligence, ambition, and yearning as those leaders.

How much of this novel is historical, and how much fiction?

I believe that fiction flourishes where the official record ends, and that research should serve as the floor—and not the ceiling—to the imagination. For the first time, I grappled with the challenges of writing a historical novel.

I believe that fiction flourishes where the official record ends, and that research should serve as the floor—and not the ceiling—to the imagination. For the first time, I grappled with the challenges of writing a historical novel.Many details in my book are recorded in history: Mao kept nocturnal hours, relied on sleeping pills, wrote poetry, and occasionally took to his bed, depressed. Dancing girls from cultural troupes served him. He also swam in the Yangtze River in July 1966, a feat heralding his return to power during the Cultural Revolution. The characters of the Madame, President, Defense Minister, and Premier are very loosely based on those in Mao’s inner circle; their rivalries and alliances existed, though my novel departs in the particulars.

Your heroine is unnamed when we first meet her. She tells her story in retrospect, from the standpoint of 1976 in San Francisco’s Chinatown, when Chairman Mao has just died, and addresses it to an equally anonymous “you.” We find out only late in the book who the “you” is, so I don’t ask you to explain that part. But why relate the story within this frame?

I started writing Forbidden City in 2007 and finished final edits last year—about fourteen years, or nearly a third of my life! I knew from almost the beginning I wanted a retrospective narrator, reflecting on her turbulent teenage years. But I didn’t realize who she was addressing until relatively late in the lifespan of the project, sometime after its sale in 2016. I can’t remember what inspired me to experiment with it, but once I understood who she was telling the story to, why she needed to tell it now, it added urgency and depth to my novel.

After the prologue, we snap back to 1965, when your heroine is fifteen years old. She was born Song Mei Xiang—although she goes by several names during the course of the novel. What is she like, as a personality, and where is she in her life when we first meet her?

Mei was born in 1949, the year the Communists came to power, and she’s grown up dreaming of becoming a model revolutionary. Though she’s the lowliest daughter in the lowliest family, she’s also smart and resourceful, which is how she maneuvers her way out of the village and navigates the rivalries in the dance troupe and at the Lake Palaces.

By novel’s end, she’s a survivor, but as she—and we—learn, survival comes at a cost.

Mei Xiang gets her wish. She’s taken from her village to Beijing, to a part of the Forbidden City where the Communist elite has established itself. What is her role there?

She becomes the Chairman’s companion and confidante, trained as part of an elaborate prank to humiliate the President. She tries to make herself indispensable to him, but her time beside him is fraught with peril and precarity. As the Cultural Revolution unfolds, she influences him in ways that later haunt her.

What are her impressions of the Chairman and why does she cling to him despite a rather rocky beginning and an enormous age gap (he’s seventy-two when they meet)?

She’s raised to believe he’s a god; she looks at his portrait every day on the wall of her home. But after she meets him in person, she has to confront him as a man and not a god. When she joins his inner circle and becomes his confidante and companion, her youthful idealism collides with the reality of who he is—his intelligence, his tenderness, but also his cruelty and selfishness—she becomes disillusioned.

There are many other interesting characters I’d love to ask you about—Teacher Fan, Secretary Sun, Midnight Chang and the other girls in the dance troupe, not to mention Madame Mao. Do you have a personal favorite, and if so, what can you tell us about him or her?

That’s like asking me which of my twins is my favorite! They both are. Likewise, all my characters are my favorites—all born from my imagination! All of them represent “What ifs” I dreamed up and mulled over. As I mentioned, I started this project in 2014, so these characters have been my longtime companions.

This novel just came out. Do you already have another in the works?

Yes, I’m working on a novel about surveillance and suburbia and also putting together an essay collection.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Vanessa Hua is a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of the novel A River of Stars and a story collection, Deceit and Other Possibilities. A National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, she has also received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, and a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, as well as awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, among others. She has filed stories from China, Burma, South Korea, and elsewhere, and her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic. She has taught most recently at the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.

Photograph of Mao waving before his 1966 swim across the Yangtze and propaganda painting of Mao and his closest cadres during the Cultural Revolution public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

June 3, 2022

Trapped in the Fens

I hadn’t heard of Catherine Lloyd before her publicist sent this book my way, but I soon discovered that she has eight previous novels, set during the Regency in the English village of Kurland St. Mary. I tore my way through those in short order, caught up in the lives of Major Robert Kurland and the local vicar’s daughter, Lucy Harrington, as they solved one mystery after another—several in Kurland St. Mary itself, but others in London or Bath.

I hadn’t heard of Catherine Lloyd before her publicist sent this book my way, but I soon discovered that she has eight previous novels, set during the Regency in the English village of Kurland St. Mary. I tore my way through those in short order, caught up in the lives of Major Robert Kurland and the local vicar’s daughter, Lucy Harrington, as they solved one mystery after another—several in Kurland St. Mary itself, but others in London or Bath.When I finished with those, I started the new series: a different cast and a slightly later time period, but the same blend of characters operating in the midst and at the edge of high society, creating a clash of expectations and prospects that fuels tension that explode into murder. As Catherine Lloyd notes during our interview for the New Books Network, Major Kurland is dealing with the aftermath of a devastating blow during the Peninsular War that almost cost him his leg. Lucy Harrington struggles to keep house for her father, a position where she has great responsibility but insufficient authority, without losing track of her own needs and goals. Caroline Morton grew up in privilege as an earl’s daughter, only to see her prospects dwindle, then disappear, because of her father’s extravagance. But these are the leads: the secondary characters caught up in each case have problems of their own, all magnified by the goldfish-bowl effect of a rural village or an isolated country estate. Memories are long and reputations set in stone, and watching those immutable exteriors war with changing human needs and desires is for a historian where the fun lies.

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

As we soon find out in this opener to a new series set in 1830s London, Lady Caroline Morton’s illustrious heritage has been tarnished by the financial ruin and suicide of her father a few years earlier. The economic opportunities available to young women—especially noblewomen—in Victorian Britain are extremely limited. Caroline’s family has offered to support her, but life as a poor relation doesn’t appeal to her. As a result, she has broken with tradition and taken a position as companion to a wealthy but less-cultured widow, Mrs. Frogerton. One of her responsibilities is to prepare Mrs. Frogerton’s teenage daughter for her debut into society.

Caroline is settling into her new life when her Aunt Eleanor arrives to announce that she’s sponsoring a house party and expects Caroline to attend. To sweeten the deal, Aunt Eleanor invites Mrs. Frogerton and her daughter as well. Miss Morton (she considers the “Lady” inappropriate for a paid companion) can’t refuse when it’s pointed out that the house party provides a perfect setting to introduce Miss Frogerton to London’s high society. Caroline also wants to check on her younger sister, still living at their aunt’s house.

Caroline’s worst fears are realized when, not long after her entry to the estate, she encounters the man she was engaged to marry, only to have him turn his back on her without so much as a greeting. Bad turns to worse, including the troubling disappearance of a trusted servant, followed by a gruesome murder that Aunt Eleanor and her family insist must be an accident. Only the country doctor agrees with Caroline that an investigation is warranted. Meanwhile, the killer appears to be leaving clues in the nursery as to the identity of the next victim.

All this takes place in a classic locked-room setting, where torrential rains flood the Fens and prevent anyone within the house party or on the staff from leaving the estate. Catherine Lloyd weaves a gripping tale that pits a vividly imagined and complex set of characters against one another and the elements. If you’re a fan of historical mysteries, you won’t be able to put this one down.

Image from a Gothic novel (Sir Walter Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor [1819] public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 27, 2022

When History and Fiction Intersect

Many thanks to Joan Schweighardt, who ran this interview with me on the Five Directions Press site today. Alas, three months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the cross-linked post below is as relevant as it was the day it went up.

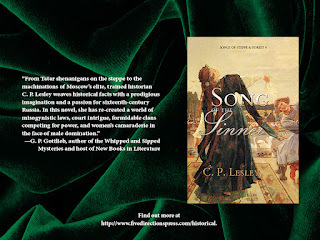

Your new novel is the fourth book in your Songs of Steppe & Forest series. Can you tell us something about the series as a whole and the newest title, Song of the Sinner, in particular?

The series as a whole explores the boundaries that constrict women’s lives in Tudor-contemporary Eastern Europe—specifically, Russia and the surrounding lands in the 1540s. Unlike my first historical series, where the main characters had arranged marriages—as most people did at the time—in this one I wanted to explore less traditional paths to happiness. These characters embrace love without marriage or emphasize their religious vocations or pursue lovers whom others consider unsuitable. Solomonida, the heroine in Song of the Sinner, strives to balance her love for a man from a lower social class against her belief that she should sacrifice her own needs on behalf of her daughter. Something a lot of contemporary mothers struggle with as well! She also fears that commitment means loss of control over her own fate and even her body, because her first husband was a manipulative brute.

Your Russian-based fiction is an extension of your academic career. Can you tell us the story of how you came to be a scholar regarding all things Russian.

Your Russian-based fiction is an extension of your academic career. Can you tell us the story of how you came to be a scholar regarding all things Russian. I’ve always loved languages, and when I discovered that my northern New Jersey high school offered Russian, it sounded exotic and fun. So I signed on. When I got to college, I fell in love with the culture and the history—which is a long series of dramatic events worthy of the movies. So when I decided to apply to grad school in history, it made sense to focus on Russia. But I was always more interested in pre-industrial times; hence my specialization in early modern Europe, sixteenth-century Russia in particular. In addition to my novels, written under a pen name to separate them from the academic stuff, I translated and published The Domostroi: Rules for Russian Households under Ivan the Terrible , which is a set of instructions written (probably) in the sixteenth century on how to manage a large urban household, including everything from proper behavior in church to recipes and ways to keep the servants from stealing food and other household goods.

You recently wrote an essay titled The Tangled History of Russia and Ukraine. Which of your novels would you recommend to readers who want to further explore that history from a fictional perspective?

My novels portray a world where what is now Ukraine is firmly situated within the Polish-Lithuanian dual monarchy, as it was in the sixteenth century, revealing the falsehood of current statements that Ukraine is simply a Russian province with no history of its own. They also reveal principles of political life that, despite many changes over the centuries, still operate in today’s Russia—the preference for oligarchy, for example. And they do this in a lighthearted, non-preachy way. I would suggest readers start with The Golden Lynx, which sets the stage for the books that follow. The heroine of that series is a Tatar princess, sent to Moscow without adequate preparation, so she needs explanations of the workings of Russian society that also benefit the reader. The second novel in that series, The Winged Horse, offers a historically accurate view of Crimea very different from anything you might have seen in the news media eight years ago, when the Russians snatched it from Ukraine. (Coincidentally, Winged Horse came out in the spring of 2014, right after the annexation.) The hero of The Vermilion Bird and The Shattered Drum has also spent time in the steppes north of Crimea, in service to a renegade would-be khan.

The other book worth taking a look at in this connection is Song of the Siren, which begins in Renaissance Poland before moving eastward to Muscovy. The heroine of that book, Juliana Krasilska, is firmly convinced that Moscow is a backwater compared to Kraków. That’s not entirely fair, but it does give a clear sense of the separate cultural trajectories of Muscovite Russia and Ukraine, which spent several centuries under Polish influence.

Because you are a historian who has focused all her adult life on a particular part of the world through time, the reader can trust that the settings, clothes, food, weapons, etc. that your characters come into contact with are utterly historically accurate. What about the characters themselves? Do you attempt to get into the minds and hearts of the czars and other personages we might know? Or are they more or less part of the staging on which your fictional characters come alive?

I try to give historical characters the widest berth possible. As a historian, the idea of putting words into the heads and mouths of people who actually lived makes me squirm. It’s not always possible, however, to avoid historical personages entirely. In those cases, I do my best to keep their words in line with their known deeds and emphasize to my readers that we have almost no information about the personal lives of even the best-documented figures in sixteenth-century Russia. That includes Ivan the Terrible himself, although naturally we know more about what he did (or is supposed to have done) than we know about most of his subjects. So in that sense, yes, I restrict the real people to the background and let my fictional characters take center stage.

You have one more book to go in your Steppe & Forest series. Did you know in advance that this series would encompass five books?

I knew from the beginning that the first series, Legends of the Five Directions, would end with the fifth direction (Center). But this series is actually open-ended. I happen to be close to finishing book 5, but I’m working on the plot for book 6, Song of the Steadfast, and I have rough ideas for at least two more books beyond that. Those last two, if I get to them, will move into the 1550s. I can imagine as many as ten, but anything beyond Songs 8 is so hazy as to be almost invisible at this point.

Although Song of the Storyteller is a work in progress, can you tell us a bit about what to expect?

Absolutely. This may be my favorite of the whole series. Lyubov Koshkina, known as Lyuba, first appeared as a six-year-old in The Vermilion Bird, and at the end of that series, she informed me that she was the unnamed narrator of the Legends books as a whole. Here we encounter her just as she is finishing The Shattered Drum and considering what she will write next. She decides to tell her own story: her memories of when, as a sixteen-year-old girl, she was summoned to the first bride show held for Tsar Ivan the Terrible (think The Bachelor, but the prize is a royal crown, not a rose). Her father desperately wants her to win, but Lyuba has fallen in love with a dashing Tatar prince. Her job is to get herself dismissed from the bride show without insulting the tsar while dodging the dirty tricks sure to be played against her by various rivals and their families. And since her best friend, Anna, has also been summoned against her will, Lyuba has to find a way to fulfill her own goals without undermining her friend’s.

Do the novels in your historical series work as standalone reads?

They do, in the sense that I ensure you can pick up any one of them and know what’s going on without having to have read the preceding books. The historical novels are all connected, though, and people have told me that they benefited from knowing that minor characters in one book were central to earlier ones. Some readers also enjoy catching up with old friends. So if I’m asked, I suggest starting with either The Golden Lynx or Song of the Siren. If you like the first book in the series, then you’ll probably like the others as well.

Do you know yet what you will write next?

I’m three chapters into Song of the Steadfast, but I’m taking a break to work out the political background before moving forward. Each Songs of Steppe & Forest novel centers around a romance—in this case, Anna Kolycheva (Lyuba’s best friend, as mentioned above, and Solomonida’s daughter) and a young man named Yuri Vorontsov—but the books are not only romances. Here the political infighting is between the young tsar’s uncles and his recently acquired in-laws, played out against the backdrop of three devastating fires that struck Moscow between April and June 1547. Once I figure out exactly what happened and how I can fit my fictional characters into the history, I’ll get going again. I’ll also be rewriting parts of Song of the Storyteller this summer so that it feeds seamlessly into the sixth book.

Images: 17th-century depiction of Ivan the Terrible (r. 1533–1584); Konstantin Makovsky, The Tsar Chooses a Bride (1886), both public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 20, 2022

Bookshelf, Spring 2022

A lot of books on my shelf this quarter, although actually I’ve read most of them—and a few more besides. But they have my interview schedules on both the podcast and the blog jam-packed; they are all good reads; and they are coming out in the next month or two, so this is definitely the time to give them a shout-out. None of these are out yet, although they are all available for pre-order. I’ll supply links when I post the follow-up interviews.

Anne Louise Bannon, Death of an Heiress (Healcroft House, 2022)

Anne Louise Bannon, Death of an Heiress (Healcroft House, 2022) I’ve been waiting for this one after enjoying the first three Old Los Angeles mysteries. There’s something very appealing about the idea of LA as a pueblo small enough to cross on foot, and Maddie Wilcox—the intrepid doctor/winemaker/crusader for justice whose memoirs form the backbone of the series—is a perceptive and clear-eyed observer. Bannon does a good job of conveying the atmosphere of what in the 1870s is still the Wild West, with saloon keepers and brothel owners, prejudice and superstition, and a general attitude among the citizenry that women should mind their place and keep their mouths shut, not going wandering about the pueblo at all hours healing injuries and hunting murderers.

This novel opens in 1872 with an heiress whose legacy is under assault from her brother and the murder of a Native American healer, ruled an accidental death by the prejudiced judge called in to handle the inquest. The threads connecting these two events are long and twisty, but the resolution seems just right. I’ll be talking with the author after the book’s release on June 14, with a New Books in Historical Fiction (NBHF) interview to run in mid-July.

Jade Beer, The Last Dress from Paris (Berkley, 2022)

In 2017, Lucille agrees to fulfill an urgent request from her ninety-year-old grandmother, Sylvie: accept a free ticket to Paris and retrieve a dress made in the 1950s by the noted designer Christian Dior. When Lucille reaches her destination, she discovers that the one dress belongs to a set of eight, all owned by Sylvie, but was sold years ago—as her grandmother has known all along. The hunt is on to find the missing dress and see the entire set conveyed back to London.

This present-day story intertwines with chapters, each named after one of the eight Dior creations and set in the 1950s, that gradually reveal how the dresses came into Sylvie’s possession and the complicated truth that lies behind her request to Lucille. This book releases on June 21, and I’ll be hosting an NBHF interview with the author around that time.

Dianne Freeman, A Bride’s Guide to Marriage and Murder (Kensington, 2022)

The fifth in an absolutely delightful historical mystery series featuring Frances Wynn, the dowager Countess of Harleigh, set in Gilded Age Britain. The daughter of a wealthy American, Frances was sold off at eighteen to an impoverished earl, who promptly spent her fortune on wine, women, and impressing Edward, Prince of Wales—the future Edward VII. After an initial, understandable reluctance to commit herself to another husband, Frances has yielded to her attraction to her next-door neighbor George Hazelton—an English gentleman but not a nobleman, employed on slightly mysterious assignments for the Crown.

In this book, they are all set to marry, and Frances believes her only problem is her interfering mother. But the night before, she learns that two warring robber barons both plan to attend. Sure enough, the more disreputable of the pair is murdered during the wedding. The police suspect Frances’s younger brother, forcing her and George to cancel their honeymoon in the hopes of solving the crime. Meanwhile, the long-suffering Inspector Delaney does his best to keep them from meddling in his investigation, with the usual mixed results. This latest installment comes out on June 28, which leaves you plenty of time to devour the first four entries in this light-hearted and engrossing series in preparation. I’ll be hosting a written Q&A with the author here on June 24.

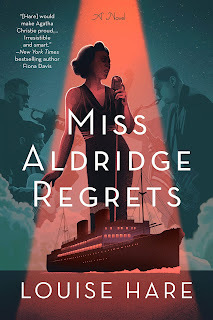

Louise Hare, Miss Aldridge Regrets (Berkley, 2022)

Another murder mystery with an interesting twist. Lena Aldridge is a mixed-race singer who has never known her mother. It’s 1930s London, and the Great Depression has made work difficult to find for almost everyone. After a series of theater jobs, Lena has fallen on hard times, reduced to singing in a crummy Soho bar owned by her best friend’s husband. Her father, a pianist, has died a few months before, and when the bar owner is murdered one evening, Lena accepts what seems like a too-good-to-be-true opportunity to travel all expenses paid to New York for a starring role in a Broadway show. What happens next defies her expectations in both good and bad ways.

The twist is that the first person we meet in the novel is not Lena but the murderer, who reappears from time to time throughout the novel commenting on and evaluating decisions without revealing their identity. I did eventually figure out what tied the threads together, but even then Hare managed to deliver more than one surprise at the end. This book comes out on July 5, and I’ll be hosting a written Q&A here on July 22.

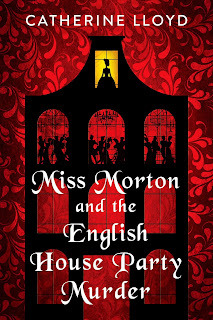

Catherine Lloyd, Miss Morton and the English House Party Murder (Kensington, 2022)

I had not heard of Catherine Lloyd before her publicist sent this book my way, but a little digging turned up the fact that she has eight previous novels in a separate series, set during the Regency in the English village of Kurland St. Mary. I’ve now read most of those and enjoyed them, as well as this latest opening to a second series.

As the title suggests, the new novel features Lady Caroline Morton, whose illustrious heritage has been tarnished by the financial ruin and suicide of her father a few years earlier. We are now in early Victorian Britain, but the economic opportunities of young women—even noblewomen—are still extremely limited. Caroline’s family would support her, but life as a poor relation has its drawbacks, and she has taken a position as companion to a wealthy but less-cultured widow, Mrs. Frogerton. But when Caroline’s cousin insists on celebrating her birthday with a house party and invites Mrs. Frogerton and her daughter to attend, Miss Morton (she prefers to avoid the “Lady” as inappropriate to a woman with a job) can’t refuse. A succession of uncomfortable encounters with her past culminate in the troubling disappearance of a trusted servant, then an outright murder that hardly anyone else will admit could be anything but an accident—all taking place in a classic locked-room setting when floods prevent anyone within the house party from leaving the estate. This well-written mystery will make its debut on May 31, and I’ve timed a podcast interview with the author to run on the New Books Network in early June.

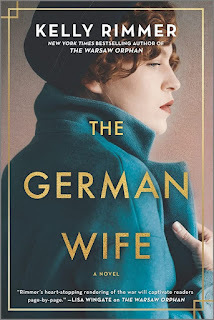

Kelly Rimmer, The German Wife (Graydon House, 2022)

Despite my frequent complaints about the ongoing avalanche of books set during World War II, they keep coming my way, and once in a while one of them catches my attention. At first, I thought this one was set in the 1950s, which is the reason I agreed to take a look—and one part of it is. But the action then is counterposed to the 1930s and 1940s, in both the United States and Germany, and the story moves seamlessly back and forth between the two countries and two points of view: Sofie Rhode as the German wife of the title and Lizzie Miller, a hard-scrabble woman from the Dust Bowl who doesn’t take kindly to German scientists showing up in her home town right after the war.

Rimmer’s portrayal of Sofie, a woman who inwardly resists Nazism yet nonetheless finds herself on the wrong side of a war she doesn’t want, is the high point of the novel—thought-provoking and compelling without pulling punches. Lizzie, too, emerges as a fully formed if troubled person, haunted by her past. You can find out more about the book, due June 28, from our written Q&A, scheduled for July 8.

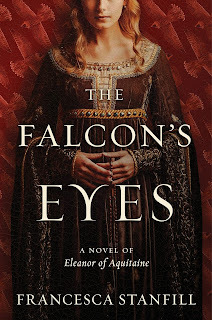

Francesca Stanfill, The Falcon’s Eyes (Harper, 2022)

Another unexpected find—very long at 800+ pages but nonetheless captivating. Isabelle, a young countess living in Provence in the twelfth century, has neither looks nor fortune nor a pliant demeanor to guarantee her a husband. Her parents have reconciled themselves to keeping her at home as a drudge for the rest of her life, but an unexpected marriage proposal from Lord Gerard de Meurtaigne—who has money but not the aristocratic heritage Isabelle can provide—sends Isabelle’s life in a new direction. Her parents insist she accept, and she does, even though she has never set eyes on her prospective bridegroom. What else is a medieval woman to do?

At first, Isabelle’s marriage pleases her more than she expected, but soon elements of darkness creep in to disturb her happiness. What happens next should be experienced, not divulged, but we know from the beginning that Isabelle attends the death of Queen Eleanor of England and Aquitaine, the shining example of a twelfth-century alternative to Isabelle’s conventional upbringing. The road between those two opening scenes takes Isabelle through a lifetime of challenges, but it’s well worth following to the end. The chance to do so comes with the novel’s publication on July 5; I will be interviewing the author in July, but exactly when and in what format remains undetermined.

May 13, 2022

Interview with Connie Hertzberg Mayo

It’s New York at the turn of the twentieth century, and Lilian Dolan is living in a small apartment with her younger sister, Marie. To support them both, Lilian talks her way into a job as a nursing assistant at the New York Cancer Hospital. She wants to become a nurse, so this seems like a good opportunity for her, and she has support from her cousin Michael, if not from her mother, because of an unspecified conflict that becomes clear only toward the end of the novel. But many of the hospital nurses shun her, and although Lilian establishes a rapport with several of the patients, her yearning to find out more about medicine brings her into contact with a new head surgeon who clearly has more insidious intentions toward her than Lilian herself is prepared to face.

It’s New York at the turn of the twentieth century, and Lilian Dolan is living in a small apartment with her younger sister, Marie. To support them both, Lilian talks her way into a job as a nursing assistant at the New York Cancer Hospital. She wants to become a nurse, so this seems like a good opportunity for her, and she has support from her cousin Michael, if not from her mother, because of an unspecified conflict that becomes clear only toward the end of the novel. But many of the hospital nurses shun her, and although Lilian establishes a rapport with several of the patients, her yearning to find out more about medicine brings her into contact with a new head surgeon who clearly has more insidious intentions toward her than Lilian herself is prepared to face. In addition to the details of medical care at the time, this novel manages to incorporate an astonishingly vast swath of New York city life: the gay scene in its various manifestations, race relations, sexual harassment, and the right to euthanasia all play a part without ever overwhelming the story. At its heart is Lilian—brave, alert, intelligent, naïve, and loving. Following her pursuit of happiness and self-worth is a journey well worth taking.

Your first novel, The Island of Worthy Boys, was set at a charity school in late 19th-century Boston. The Sharp Edge of Mercy takes place in turn-of-the-century New York. What draws you to this time period?

I love the stuffy Victorian morals of this era, especially in cities, because there is such contrast between how people “should” behave and the gritty reality of urban life. It was also a time of enormous technological change—telegraph, telephone, recorded music, electricity and so much more—which reminds me of today, just with different technology.

And what inspired this particular story?

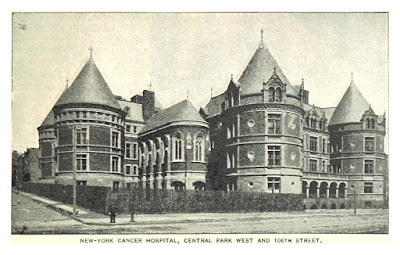

I wanted to write a novel about medical ethics, and when I heard about the New York Cancer Hospital, which was the first cancer-only hospital in the country, I knew it would be a great setting for a story with that theme.

When we first meet Lilian Dolan, your heroine, she’s moved away from her mother and is living in a small apartment with Marie, her sister. Give us a brief overview of their situation, please, at this early point in the novel.

Lillian is pretty young herself—she’s nineteen. And like many young people, she sees the world in black and white. She has judged her mother harshly for some decisions her mother made and left with her fourteen-year-old sister Marie. Marie is blind and cognitively impaired from a bout with scarlet fever, so Lillian has taken on quite a challenge in caring for her sister while working full-time.

And how would describe Lilian, as a character? What does she want in life?

Lillian wants to be a nurse, but she is too young to start a nurse training program. She’s very smart and has a strong stomach, so she will be well suited to be a nurse someday. In a different era, she would probably become a doctor. There were some female doctors at the time, but it was not easy.

She becomes a nursing assistant at the New York Cancer Hospital. What is this job like for her?

Her job duties are menial, and although she doesn’t mind them, she just can’t stop her mind from wondering about all sorts of things related to the patients and the hospital. This doesn’t win her many friends at the hospital.

It’s clear even from the short description on your website and the back of the book that this is at its heart a novel about sexual harassment—an experience all too familiar to contemporary women as well. How does that theme play out in your novel?

When the new surgeon at the hospital takes interest in Lillian, she is enormously flattered even though in the back of her mind, she starts to see red flags. They engage in Socratic debates about all the things that Lillian has been wondering about. Of course, he is a predator that understands how much Lillian craves intellectual validation. Once Lillian understands that she is in over her head, she doesn’t know how to extricate herself. I think this is a position that a lot of smart young women find themselves today, so I hope this resonates.

This novel just came out. Do you already have another in the works?

My third novel is outlined, but I have not had any time to work on it recently. It’s set in Boston in 1958, so a departure from my usual turn-of-the-century timeframe. Boston took a brownstone neighborhood called the West End by eminent domain and completely destroyed it to put up buildings for Mass General Hospital and midrange apartment buildings that the former residents couldn’t afford. My story is about three families that live together in one of those brownstones, and each family has a reason why moving will be catastrophic for at least one family member. The story also includes a young, idealistic draftsman on the city planning board who slowly realizes what this will mean for the West End residents.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Thank you for the opportunity!

Connie Hertzberg Mayo is the author of The Island of Worthy Boys, which won the 2016 Gold Medal for Best Regional Fiction from the Independent Publisher Book Awards. Her latest novel, The Sharp Edge of Mercy, was published by Heliotrope Books in May 2022. Find out more about her and her writing at https://conniemayo.com.

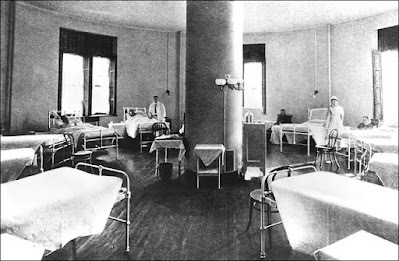

Images: Interior (1880s) and exterior (1893) of the New York Cancer Hospital, today the Memorial Sloane-Kettering Cancer Center, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 6, 2022

A Civil War Veteran at Scotland Yard

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I found this series by serendipity and read it first out of curiosity, then with increasing enthusiasm. What drew me in was the combination of complex but satisfying plots and the growing friendship between a rural English policeman and a US Civil War surgeon turned reluctant earl—each with his inner strengths and conflicts.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I found this series by serendipity and read it first out of curiosity, then with increasing enthusiasm. What drew me in was the combination of complex but satisfying plots and the growing friendship between a rural English policeman and a US Civil War surgeon turned reluctant earl—each with his inner strengths and conflicts.Lord Redmond and his buddy Daniel Haze have now reached their seventh adventure, with the eighth due for release in another month or so. They are the creation of the incredibly prolific Irina Shapiro, who graciously took an hour away from crafting their adventures to talk with me for a New Books Network interview. As you’ll hear, she has a lot of interesting insights into her characters. Read on, then listen, to find out more.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Jason Redmond, a US Civil War surgeon, never expected to step into his father’s shoes as the heir to an English earldom. When he first shows up to claim his inheritance, with a scrawny twelve-year-old former drummer as his ward, Jason plans to inspect the property, then return to his home in New York. But the discovery of an obviously murdered body in the local church first casts suspicion on Jason, then involves him—first in performing the postmortem and later in helping the parish constable, Daniel Haze, solve the crime. By the end, Jason has decided to stay in England for a while.

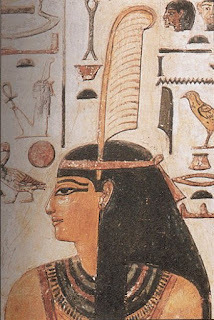

Six books and as many cases later, Haze has moved to London for reasons explained in Murder at Ardith Hall. When the corpse of Blake Upton, a renowned Egyptologist, is traced to a ship in the London Docks, it seems only natural that Daniel should involve his friend Jason in finding out who among the potential suspects had the means, motive, and opportunity to dispatch the Egyptologist to his eternal rest in the arms of Osiris. And in this variation on a locked-room mystery—the archaeologist must have been killed just before the Sea Witch docked—a surprising number of passengers and crew have something to gain from Upton’s murder. Moreover, the grisly means used to kill Upton point to someone familiar with ancient Egyptian funerary customs. Jason and Daniel have their work cut out for them if they are to find the culprit before the impatient head of Scotland Yard decides that Daniel’s first case as an inspector will also be his last.

Six books and as many cases later, Haze has moved to London for reasons explained in Murder at Ardith Hall. When the corpse of Blake Upton, a renowned Egyptologist, is traced to a ship in the London Docks, it seems only natural that Daniel should involve his friend Jason in finding out who among the potential suspects had the means, motive, and opportunity to dispatch the Egyptologist to his eternal rest in the arms of Osiris. And in this variation on a locked-room mystery—the archaeologist must have been killed just before the Sea Witch docked—a surprising number of passengers and crew have something to gain from Upton’s murder. Moreover, the grisly means used to kill Upton point to someone familiar with ancient Egyptian funerary customs. Jason and Daniel have their work cut out for them if they are to find the culprit before the impatient head of Scotland Yard decides that Daniel’s first case as an inspector will also be his last.Irina Shapiro has a gift for tricky but ultimately satisfying plots and for delving into her characters’ inner lives. Jason and Daniel have come a long way since their first appearance in Murder in the Crypt a few years ago, but let’s hope they have many adventures yet to come.

Images: The Egyptian goddess Maat and London Streetscape, 1878, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

April 27, 2022

Interview with L.C. Tyler

After two years of masking and social distancing while obsessively charting surges and death rates, encountering L. C. Tyler’s The Plague Road evokes an eerie sense of familiarity. The coincidence is not what it seems: this is the third novel in a series set in seventeenth-century England featuring one John Grey; and the series first appeared several years ago, before COVID was anywhere on the horizon. But Felony and Mayhem has decided to republish the books in the United States, and The Plague Road released earlier this week. I didn’t think about the parallels when I first heard about it; I was more struck by the somewhat unusual attention to the Stuart era. Nor do I want to misrepresent the series, the strength of which is the characters of John Grey and his childhood friend, Lady Aminta Pole. Read on to find out more.

After two years of masking and social distancing while obsessively charting surges and death rates, encountering L. C. Tyler’s The Plague Road evokes an eerie sense of familiarity. The coincidence is not what it seems: this is the third novel in a series set in seventeenth-century England featuring one John Grey; and the series first appeared several years ago, before COVID was anywhere on the horizon. But Felony and Mayhem has decided to republish the books in the United States, and The Plague Road released earlier this week. I didn’t think about the parallels when I first heard about it; I was more struck by the somewhat unusual attention to the Stuart era. Nor do I want to misrepresent the series, the strength of which is the characters of John Grey and his childhood friend, Lady Aminta Pole. Read on to find out more.The Plague Road is the third book of seven already published in the UK. Why did you pick Restoration England for the backdrop to this series?

At the time I decided to start the series (it was some years ago now), nobody much seemed to be writing crime novels set in the seventeenth century. I thought I might have spotted a gap in the market. Things have truly moved on. Though still not quite as crowded with fictional detectives as the Tudor period, both the English Republic and the Restoration are now receiving a lot of attention. Which, I suppose, they deserve. Particularly during the last days of Oliver Cromwell and the early years of Charles II, it was a great time for plotting and counter-plotting, with the Sealed Knot, the Action Party, the Levellers, the Fifth Monarchists, and many other subversive groups all very active and full of double agents. The Restoration also launched a period of loose morals, flamboyant clothing, political dishonesty, unnecessary wars, and unconcealed greed. All bang up to date, and more than enough to frame the plots for several series …

This book was originally published in 2016, so any echoes of the current pandemic are pure coincidence. But is there anything you’d like to say about that element of the story?

Yes, I clearly had not foreseen COVID when writing The Plague Road, though pandemics occur regularly and it should have occurred to me that we might see another major one in my lifetime. The plague was, of course, much more frightening than COVID because, if you caught it, the death rate was so very much higher and, though plenty of people sold guaranteed remedies for the plague, none of them worked. The medical infrastructure we rely on now was nonexistent. The doctors largely fled London when the Plague struck. Plague victims might be cared for at home (if any of your family were still alive) or in a “pest house,” such as the one at Tothill Fields that John Grey visits in the book. Pest houses were fairly grim places and very overcrowded. The way I describe the physician having to walk across the beds to get to patients, because there was no room to walk between the beds, is based on contemporary descriptions. On the other hand, unlike COVID, the Plague does seem to have been relatively easy to avoid if you were rich enough and weren’t obliged to live in close proximity to Plague victims. The royal court, like the doctors, simply left London. Samuel Pepys sent his wife to the country but remained at his desk, and although he had several frights such as his hackney coach driver collapsing halfway through a journey (Pepys ran off as fast as he could), he survived to tell the tale. I mean literally, in this case. The Diaries are always worth reading.

More generally, what is John Grey’s London like in 1665?

It was very different from what it would be a couple of years later, since most of the houses, churches, and civic buildings would be swept away by the Great Fire in 1666. 1665 was therefore the last year of the ancient medieval city—half-timbered houses, narrow lanes filled with rubbish of all types, all dominated by the massive nave and stumpy tower of Old St Paul’s. It would have been crowded, smelly, and noisy—side by side with the many elegant gardens and the Palace of Whitehall, there were plenty of workshops, slaughterhouses, and tanneries. London at that time possessed only one bridge—London Bridge—which had been rebuilt and patched up many times. The bridge was one of the great sights of the city and was noted for two things. First, there were rows of houses, up to seven storeys high, built on it. They encroached on the road and made the crossing a dreadful bottleneck for travelers. Second, the arches of the bridge were also very narrow and dammed back the Thames, so that at each tide water rushed through them at high speed. “Shooting the arches” in a small boat was something that you could do if you were young and drunk enough and wanted to impress the girl you were with. London Bridge was proverbially “for wise men to pass over, and fools to pass under.” If you were still alive on the far side of your chosen arch, you could celebrate by visiting one of the new restaurants (“ordinaries”) or one of the coffee houses that were just coming into fashion. The theaters had recently reopened after the ban on acting during Cromwell’s time, and for the first time ever actresses were permitted on stage. So London was crowded, smelly, and dangerous, but you could have fun.

And John Grey as a character? What can you tell us about him, as your window on the novels?

In the first book in the series (A Cruel Necessity) John Grey has just finished his studies at Cambridge University and is about to begin training as a lawyer in London, though he finds himself being dragged, partly by circumstances and partly by inclination, into the world of espionage. He is bright and personable, but still somewhat naive and a bit too trusting. The Plague Road begins some seven years later, during which time he has both become a fairly successful lawyer and has worked as a spy, first for Cromwell and then for Charles II. During those seven years he’s had to learn a lot of things and does actually have the scars to show for it. I wish I could tell you exactly what he did between books 2 and 3, but I made the decision to jump forward from Cromwell’s death to the Plague Year, and I will probably now never know what he got up to, though every now and then Grey drops hints that he was in Brussels or the West Country on a particular date. Anyway, by 1665 he has become one of spymaster Lord Arlington’s most trusted men and capable of fighting (Arlington once blackmailed a fencing master into giving Grey lessons) or of talking his way out of most things. His personal life is, however, a complete mess, as is obligatory these days for all fictional detectives—see below.

And what is Grey’s central problem in this novel?

1. That he did not marry the woman that, clearly, he was meant to marry. 2. That somebody has tried to dispose of a body in a plague pit, even though the knife sticking out of the corpse’s back suggests death by some cause other than the Plague. 3. That his boss, Lord Arlington, only ever gives him half the information that he needs.

We learn early on that the victim, Charles Fincham, is both actor and spy, which is an interesting combination. Was that common at the time?

Spies—both men and women—came from every possible walk of life. They were recruited wherever and however the government could do it. Some were professional. Some were amateurs. Some had served as soldiers during the Civil War and failed to find any other way of living during peacetime. Some accepted employment as a spy as an alternative to being hanged for some minor (or major) offense. Some spied out of conviction for a cause. Most did it to a greater or lesser extent for the money. Actors and writers do seem to have featured quite prominently, being good at impersonation and at coming up with plausible stories. The playwright Aphra Behn is one of the better known examples. She undertook at least one mission to Bruges for the government in the 1660s, for which she was probably never paid, and may have done other work for Arlington and his assistant Williamson in the following decade—like John Grey, Behn has a gap in her life history when we know little about her.

Is the plan to publish all seven John Grey novels in the US? And what are you writing now?

I suspect that whether all of the John Grey books are published in the US will depend very much on how many people buy them. (Yes, dear reader, that is a hint.) I’ve just finished writing John Grey #8, which is set in the world of the Restoration theater and the immoral and licentious court of Charles II. Prepare to be mildly shocked.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Excellent questions! Thank you for asking them!

L.C. Tyler is the award-winning author of the Ethelred Tressider and John Grey series, as well as the standalone novel A Very Persistent Illusion. Find out more about him and his books at https://lctyler99.wixsite.com.

Panorama of London (1647), focused on London Bridge, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.