C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 6

April 7, 2023

You Want Murder with That?

A couple of months ago, I wrote about the joys and discomforts of switching sides and talking about my own books on the New Books Network rather than asking questions of other people. Here I’m back in my familiar chair, talking with G.P. Gottlieb about the latest of her Whipped and Sipped Mysteries, a fun contemporary series featuring the amateur detective Alene Baron and her police officer boyfriend, Frank, who solves murders for a living.

One thing I love about this series—in addition to the recipes at the end of each volume—is that Alene’s life inside and outside the café she owns are just as important to the story as the crime of the moment. For someone whose main preoccupations are taking care of her kids, her ailing father, and her employees, this seems very true to life. Murder is both horrifying and compelling, but for Alene solving one is at best a fascinating distraction—one that Frank and her family and friends often urge her to leave to the professionals. Read on—and listen to the interview—to find out more about Alene’s latest case.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from the New Books Network.

In Charred, the third of G.P. Gottlieb’s Whipped and Sipped Mysteries, her heroine, Alene Baron, has a lot on her mind. Chicago is in lockdown, a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, complicating Alene’s already hectic life. The vegan café she owns can serve only takeout, and her three kids complain constantly about school via Zoom and the near-absence of opportunities to interact with their friends. Alene’s ex-husband is, as ever, no help. Her aging father also requires assistance, a reality complicated when his usual caretaker falls ill with the virus. Alene struggles to find time even to visit the café, never mind bake. But with her livelihood at stake, she must keep showing up, no matter how many conflicting demands tug her in other directions.

On the up side, Alene’s romance with Frank, a police officer, is progressing—although they have yet to make the relationship permanent. And conflict among her staff members has eased, even though they still argue about the best approach to the pandemic and the homeless man who regularly stations himself outside the café and insults staff and customers as they go in and out, among other issues.

All that changes when Kofi, the boyfriend of a Whipped and Sipped staff member, stumbles over a charred corpse while searching for wood he can use in his artwork. Kofi’s girlfriend begs Alene not to involve the police, despite Alene’s protests that keeping secrets will undermine her relationship with Frank. Soon Alene has no choice but to find out what’s behind the mysterious death, even if it means delving into the long-buried secrets of her own family.

March 31, 2023

Life as a Battlefield

Jacqueline Winspear is known to millions as the author of the Maisie Dobbs novels, which feature an intelligent, compassionate, upwardly mobile detective whose experience as a battlefield nurse during World War I informs her understanding of both the victims and the perpetrators of the cases she investigates. In

The White Lady

, Winspear examines the long-term effects of war on those forced to become killers if they want to survive.

Jacqueline Winspear is known to millions as the author of the Maisie Dobbs novels, which feature an intelligent, compassionate, upwardly mobile detective whose experience as a battlefield nurse during World War I informs her understanding of both the victims and the perpetrators of the cases she investigates. In

The White Lady

, Winspear examines the long-term effects of war on those forced to become killers if they want to survive. As she notes during our recent New Books Network interview, both Maisie Dobbs and Winspear’s latest heroine, Elinor White, were not so much created as encountered—Maisie at a traffic light and Elinor as a memory of a woman the author met in childhood. You’ll need to listen to the interview to hear those stories, but read on to learn a bit more about Elinor, recruited into espionage at the age of eleven and still fighting for justice and for peace more than thirty years later.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

It’s just after World War II, and Elinor White (born Elinor de Witt, which also means “white”), a single woman in her mid-forties, lives as a recluse in a village near Tunbridge Wells. One day in 1947, while on a walk, she encounters a recent arrival named Rose Mackie and is drawn to Rose’s three-year-old daughter, Susie. When thugs from London threaten Rose and Susie, Elinor brushes off the skills she polished during the two world wars and, with the help of a former colleague who has risen through the ranks at Scotland Yard, sets out to discover exactly what the thugs have planned for Rose’s husband, Jim. While trying to put a stop to it, she uncovers a web of intrigue and corruption that reaches to the very top of society.

This story occurs alongside an exploration of Elinor’s past, beginning with her girlhood in Belgium under German occupation during World War I and extending to her service as an intelligence agent against the Nazis twenty or so years later. Eventually the two threads of Elinor’s history and present intersect, revealing the achievements and the regrets that drive her.

Here, as in her Maisie Dobbs series, Jacqueline Winspear demonstrates a deep and multifaceted understanding of the effects of war on those forced to fight. Her books are thought-provoking, emotionally satisfying, and well worth your time.

March 24, 2023

Beyond the Magic Castle

We don’t often think of fairy tales as having much connection to real life. We talk about the fairy-tale endings of rom-coms or even real people living fairy-tale existences, but most of us recognize those seemingly idyllic situations as illusions. Life contains happiness but also sorrow, and relationships are always complicated. Even less do we see the magical elements—lonely, haunted castles; witches riding brooms and casting spells; princes turned into frogs—as anything more than delightful escapes from our prosaic everyday lives.

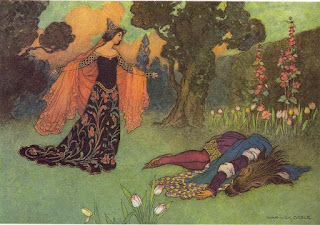

We don’t often think of fairy tales as having much connection to real life. We talk about the fairy-tale endings of rom-coms or even real people living fairy-tale existences, but most of us recognize those seemingly idyllic situations as illusions. Life contains happiness but also sorrow, and relationships are always complicated. Even less do we see the magical elements—lonely, haunted castles; witches riding brooms and casting spells; princes turned into frogs—as anything more than delightful escapes from our prosaic everyday lives.But as Molly Greeley shows in her wonderful new novel, Marvelous—the subject of my latest interview on the New Books Network—at least one well-known fairy tale, Beauty and the Beast, grew out of an extraordinary set of historical circumstances. Before Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm—and long before Disney’s singing Belle—the story of Pedro Gonzales (Petrus Gonsalves) and his wife, Catherine, circulated out from the sixteenth-century French court of Henri II, acquiring layers of magic and meaning that gradually obscured the real-life couple at the heart of the tale. Stripped of its veils—although still fictionalized—it becomes a story for grownups who know that it takes more than a magic wand to make a marriage work. And watching Pedro and Catherine struggle with their own preconceptions and problems as well as the complex demands placed on them and the often careless insults meted out to them by their world makes for a rich and rewarding adventure.

As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

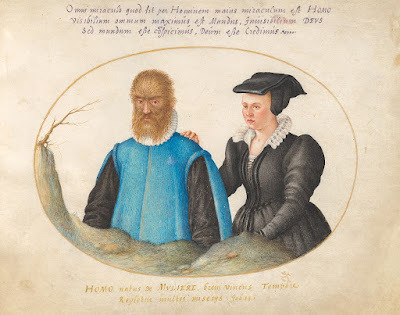

Once in a while, a novel comes along that is both different and special. Marvelous is such a book. Retellings of fairy tales are not unusual, and some of them are quite good. But here Molly Greeley explores the real-life story that gave rise to one of the best-loved tales, Beauty and the Beast. In doing so, she raises issues of inclusion, trust, acceptance, the effects of trauma, and basic humanity—all in a gentle, non-preachy way.

Pedro Gonzales, later known as Petrus Gonsalvus or Pierre Sauvage (Pierre the Savage, which itself says a great deal about other people’s views of him), was born on Tenerife, the largest of the Canary Islands, around 1537. We know from early on that he was abandoned by his mother as an infant, presumably because he was born covered in hair—a rare genetic condition that was seen at the time as evidence that a child was the spawn of a devil. His adoptive mother, Isabel, belongs to the indigenous people of Tenerife, the Guanche, whose culture and religion have been all but obliterated by the conquering Spaniards. So she and her son, Manuel, are also, in a sense, outcasts.

When Pedro is around nine, pirates kidnap him, and he winds up at the court of the French King Henri II and Henri’s wife, Catherine de’ Medici. Henri, charmed by Pedro’s combination of strangeness and acumen, takes the child under his wing and gives him a royal education, as well as financial support. But the effects of Pedro’s abandonment, early mistreatment, and capture—heightened by the suspicion and disrespect of his fellow nobles, most of whom see him as little better than a trained monkey—leave him feeling perennially unsure of himself.

When Catherine de’ Medici arranges his marriage to her namesake, the beautiful sixteen-year-old daughter of a merchant who has fallen on hard times, Pedro has no idea how to talk to this girl who is half his age. Her discomfort—how many teenage girls want to marry, sight unseen, a taciturn man in his mid-thirties who looks like a Wookie?—plays into Petrus’s fears, and the newlywed couple struggles to find a connection. But when fate deals Catherine a hand she has both anticipated and feared, she rises to the challenge, and Pedro begins to realize that she is nothing like the mother he lost.

Greeley does a great job in conveying the sensory experience of her two leads and, by alternating Pedro’s view with Catherine’s, charting their individual growth, which in turn creates a credible portrayal of their developing relationship. If you love books focused on family and identity, as well as stories set just a little off the beaten path, this is definitely a novel for you.

Images: Nineteenth-century rendering of Beauty and the Beast and sixteenth-century depiction of Petrus Gonsalves and his Catherine, both public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

March 17, 2023

Interview with Kristen Loesch

As I write this post, Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified aggression against its neighbor Ukraine has entered its second year. With President Vladimir Putin apparently set on turning the country he leads into an international pariah, it is simultaneously dispiriting to recall and difficult to believe that just over thirty years ago, the Soviet Union dissolved into its constituent republics—the very agreement that Putin seeks to overturn, although at the time it sparked great joy and hope.

Thus it seems fitting that Kristen Loesch, the author of The Last Russian Doll, begins her debut novel in that period of celebration but quickly reverts to the Soviet experiment that preceded it, deftly intertwining the two threads as they build to a dramatic conclusion. I would have loved to chat with her for the New Books Network, but an overcrowded schedule made that impossible, so read on to find out more.

In the current climate, it’s hard to remember the optimism sparked by the changes that Russia underwent in 1991. What made you decide to set your story there and to contrast it with the preceding century?

It may have all started when a friend of mine showed me her handwritten correspondence with someone she knew who was living in Moscow in 1991. The sense of destiny, of inevitability, in those letters was wondrous to behold. This was around the time I had completed a YA thriller set in contemporary Moscow, a manuscript that wasn’t in any way fit for publication. I’d already been toying with the idea of pivoting to a historical novel—I studied history with a focus on Russia and Eastern Europe for my undergraduate degree, and in my postgraduate work I looked at civil society in post-Soviet Russia. Profoundly moved by those letters, I decided to pluck the main character out of that present-day YA thriller and place her in 1991 Moscow instead. Needless to say, she became very different by the end of that process (she is Rosie, and more on her below!).

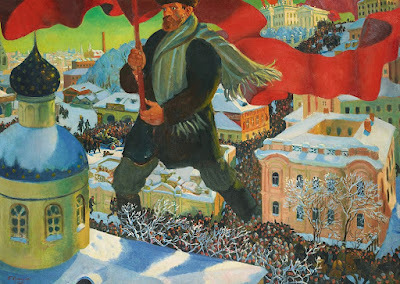

As for choosing revolutionary Russia (and the ensuing decades) for the second narrative, I think whenever you examine the end of an era, it’s always illuminating to look at its genesis as well. It’s like holding up a mirror: Much of the optimism, as you say, for true political change, for an overhaul of society, for the disruption of the status quo, also existed in 1917. And I think I liked the idea of the fall of the Romanov dynasty and the collapse of the USSR acting as bookends. In between these two major events, of course, is a unique and devastating period of Russian history, the lessons of which should never be forgotten; that is where the majority of the novel takes place.

You have two heroines and two heroes, one each for past and present. Tell us what we need to know about Rosie at the beginning of the novel.

At the outset of the story, Rosie is in incredible pain, and she is in denial of it. She’s a workaholic who keeps herself busy, keeps herself distracted, to avoid feeling that pain, confronting uncomfortable truths, and engaging with her trauma overall. She maligns her mother for always turning to fairy tales, but Rosie tells herself her own stories about her life and her future as a coping mechanism. To Rosie, her mother is a prime example of how pain can overwhelm a person, can drag them under, and on some level Rosie is terrified that that will happen to her.

You could say that she’s someone who’s very out of touch with her true self, with her desires, with her deeper emotions, and that’s by design. Having become what her father (whom she idealizes) wanted her to be, Rosie’s real quest is not only to understand her family, to grapple with the past, or even to heal her wounds, but also to discover who she wants to be.

And who is Antonina? What is most vital to know about her?

First of all, Antonina was named after Tonya in Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago! (I always liked Pasternak’s Tonya; I feel she gets the short end of the stick.)

Tonya is, at the beginning of The Last Russian Doll, somebody who has no idea of her own strength. As a privileged young bride, she starts out innocent and a bit dreamy, sort of mournfully drifting through life without much agency or ambition. Until she meets Valentin, the greatest passion she ever feels for anything is for poetry, long walks, and reminiscing about her childhood home. In a way, she seems like a “doll” both inside and out. But Tonya is, as we learn throughout the novel, capable of so much more than she appears to be on the surface. Her challenges are incredible, but so is she.

Rosie’s counterpart is Lev, although she also has a boyfriend in London. Antonina’s is Valentin, and she initially has a husband. How would you characterize these male characters of yours?

Lev, as a member of the military in 1991, is the embodiment of many of the tensions that existed in Russia at that time. I think on the one hand, he’s been brought up to fear change; but on the other hand, deep down, he knows that the time has come. Part of his struggle is reconciling his upbringing, his lifestyle, his whole identity, with the often troubling reality of the military, the secret police, and the regime itself. His family are hardliners, but they’re losing their grasp on him, and alongside Rosie we begin to see the cracks appear.

Valentin, who begins the book as a Bolshevik orator in prerevolutionary Russia, is one of my favorite characters. You could call his idealism, his politics, his devotion to the cause very naïve, in the same way that his initial infatuation with Tonya is naïve. Valentin is a romantic; he believes in a utopia, he believes in happy endings (partly in response or reaction to a lonely childhood). In drafting his character, I had the thought that he’s not unlike Victor Laszlo from the film Casablanca; like Laszlo, he has the ability to stir great emotion in people; his passion is often contagious; but also like Laszlo, he can be blinded by his principles.

The final version of The Last Russian Doll contains much more of Valentin’s perspective than the original version(s), and I loved writing those scenes.

Another important connecting force—although we won’t say what connects him!—is Alexey Ivanov. Sketch his character and his role in the story, please.

As a famous writer and historian in 1991, Alexey starts off as an unobtrusive if enigmatic presence. He’s elderly, he’s mild-mannered, and he’s easily dismissed and overlooked by Rosie, who only sees him as a means to an end; he’s her ticket back to Russia. But as the story unfolds, we understand that there is more to Alexey than what he chooses to show to Rosie in the opening scenes of the novel. Alexey is one of the threads that binds the two narratives (Rosie’s and Tonya’s) together—but it takes time to discover how. I will add that people who know the landscape of Soviet dissident literature may pick up on a few biographical similarities between Alexey Ivanov’s character and the real-life figure of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, but these similarities are superficial and arbitrary. Alexey is not based on anyone in real life.

As the title suggests, dolls play an important role in Raisa’s quest. The image of nesting dolls does appear, connecting the female characters to one another. But most of the dolls are rather creepy porcelain look-alikes. Talk to us about them, and why you decided to use them in your story.

Matryoshkas are lovely and inherently interesting, with their many layers, but I’ve never found them creepy or uncanny. Porcelain dolls, by contrast, have always unsettled me. That’s probably why I was first drawn to writing about them! But in terms of using dolls in the story, Tonya’s character was originally inspired by the Russian fairy tale “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” which features a talking wooden doll. Wanting to use dolls as a motif in the novel and to explore related themes (the interior versus the exterior; outer beauty versus inner; surface versus substance), I started to research them, and discovered that there is quite a proud tradition of porcelain doll making in Russia, one that receives almost no attention (by contrast to nesting dolls, which have come to symbolize Russia to the rest of the world, for better or worse). The more I learned about porcelain dolls, the more fascinated I became, and when I realized that their heads are often hollow—and that you can remove the top of the scalp to look inside the head—I just knew that that was where Rosie’s mother was going to hide her darkest secrets.

For further reading on Russian porcelain dolls, check out the fantastic nonfiction book The Other Russian Dolls: Antique Bisque to 1980s Plastic by Linda Holderbaum.

This novel has just come out. Are you already working on something new?

I’m currently revising my second novel, which is a gothic murder mystery set in 1930s Shanghai and 1950s Hong Kong. It’s partly inspired by my grandfather’s tumultuous early life in northern China and his harrowing escape following the Communist Revolution, as well as my grandmother’s experiences under Japanese occupation. I also wrote a tiny, 200-word “microfiction” story for the online journal Flashback Fiction about a young Chinese woman who swims from the mainland to Hong Kong—and that young woman has become the main character of my second novel! (A bit of parallel, there, with what happened with Rosie!) Overall, it’s been a joy and a revelation to draw on my family history and heritage for this project, and I’m incredibly excited for what will come next.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Kristen Loesch holds a BA in History, as well as a Master’s degree in Slavonic Studies from the University of Cambridge. The Last Russian Doll is her debut historical novel. Find out more about her at https://kristenloesch.com.

Images: Leaders of the Soviet republics signing the Belovezh Accords, which dissolved the USSR, by U. Ivanov, RIA Novosti archive, image #848095, CC-BY-SA 3.0; Boris Kustodiev, Bolshevik (1920), public domain; collection of bisque dolls from St. Petersburg by Ninara from Helsinki, Finland, CC BY 2.0, all via Wikimedia Commons.

March 10, 2023

Interview with Sherry Thomas

It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of Sherry Thomas’s Lady Sherlock series, despite having encountered them almost by accident. As with Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell, the charm of Charlotte Holmes more than makes up for the fact that I am not in fact nearly so enchanted with the original Conan Doyle stories. Since the moment I picked up

A Study in Scarlet Women

—even the title is a delightful nod to the series’ light-heartedness—I have embraced this slightly skewed but always entertaining view of the Great Detective.

It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of Sherry Thomas’s Lady Sherlock series, despite having encountered them almost by accident. As with Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell, the charm of Charlotte Holmes more than makes up for the fact that I am not in fact nearly so enchanted with the original Conan Doyle stories. Since the moment I picked up

A Study in Scarlet Women

—even the title is a delightful nod to the series’ light-heartedness—I have embraced this slightly skewed but always entertaining view of the Great Detective. I talked with Sherry Thomas when the previous book, Miss Moriarty, I Presume? , came out, and you can hear that conversation at the New Books Network. But whether you listen there or not, do read on to find out more about the series as a whole and the latest installment, A Tempest at Sea , in particular. And if you read madly all weekend, you’ll be ready when the book releases next Tuesday, March 14, from Berkley Publishing!

This is your seventh mystery featuring Charlotte Holmes. People who’d like to know more about the series can listen to our podcast interview on the New Books Network, but can you provide a short summary/refresher of who Charlotte is and how she becomes Sherlock Holmes?

Of course! Everybody under the sun has a take on the great consulting detective and the Lady Sherlock series is my entry into the wild, wild world of Sherlock Holmes pastiche.

Believe it or not, I’d originally intended for my gender-bent Holmes to be a teenage girl living in the suburbs of contemporary Austin, TX. But then my YA editor told me that mysteries don’t sell very well in YA, so I decided that I would write my Lady Sherlock for the adult commercial market. In order to capitalize on my historical romance readership, my Lady Sherlock mysteries would be set in the Victorian era, in the 1880s, the time period of the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories.

But that was when women had very limited public roles. What kind of a woman would become a consulting detective? Wouldn’t her family object? And what about the general public? Would they entrust their thorniest problems to a female investigator?

Thus was born Charlotte Holmes’s backstory. In pursuit of some agency over her life, a scandal erupts and she becomes an outcast and has to run away from home in order to avoid being locked up for the rest of her life.

Thus was born Charlotte Holmes’s backstory. In pursuit of some agency over her life, a scandal erupts and she becomes an outcast and has to run away from home in order to avoid being locked up for the rest of her life.But then her downfall turns into her salvation, as in this new wilderness she finds herself, and she encounters the lovely Mrs. Watson, former demimondaine, who encourages her to monetize her powers of observation and deduction. Who, in fact, puts up her own money so that Charlotte can hang out her shingle as Sherlock Holmes, consulting detective. The nominal Sherlock Holmes is explained away as a bedridden invalid and Charlotte, his “sister” and oracle, then very logically receives clients on “his” behalf and leaves the house for investigations when such is called for.

And why does Charlotte board the Provence?

Professor Moriarty featured very little in the canon stories but has become an iconic character for any modern Sherlock Holmes adaptation. So in the first six Lady Sherlock books, those two potential archenemies orbited ever closer to each other, until things came to a head in book 6, Miss Moriarty, I Presume?

Professor Moriarty featured very little in the canon stories but has become an iconic character for any modern Sherlock Holmes adaptation. So in the first six Lady Sherlock books, those two potential archenemies orbited ever closer to each other, until things came to a head in book 6, Miss Moriarty, I Presume?In the wake of those events, Charlotte has been lying low. Until she gets something of an irresistible offer—help the crown retrieve an important dossier of documents, and the crown will tell Moriarty to back off.

But this dossier proves harder to find than she originally anticipates, and her last lead leads her straight to the RMS Provence. She is in disguise, trying to find the dossier while eluding Moriarty’s minions. But during a storm-tossed night in the Bay of Biscay, a murder happens aboard the Provence. So now instead of investigating a murder, she has to try to avoid being swept up in the investigation as well.

One character we didn’t get to talk about during the interview, because we ran out of time, is Charlotte’s sister Olivia (Livia) Holmes. Livia is quite different from Charlotte in personality. How would you characterize her and her role in the novels? And what does she seek from her steamship voyage?

Charlotte is fearless and largely immune to peer pressure—she is Sherlock Holmes, after all. Livia, on the other hand, stands for all the wonderful women I’ve met in my life and career who do not see how wonderful they are and who have lost a portion of their self-belief along the way because they have for one reason or another been criminally undervalued.

Charlotte ran away from the oppressive Holmes household. Livia, however, is the dutiful, browbeaten daughter who has stayed. Their wonderful cousin Mrs. Newell invites Livia to accompany her on this ocean voyage. At the beginning of the trip, all Livia is hoping for is a lovely respite from her parents. But at the end of the books, she will be asking for a great deal more.

Trouble starts even before everyone boards the steamer, and Livia is the one who witnesses it. Who is Roger Shrewsbury, and how does he come into conflict with his future fellow passengers, the Arkwrights?

Roger Shrewsbury is one of the people Livia despises the most, because he unwittingly compromised Charlotte, leading to Charlotte’s exile from polite society. But he isn’t remotely evil, just a complete dumbass, one from a privileged enough background to have never really needed to grow up.

On the day of the Provence’s departure from Southampton, when passengers are gathered in the hotel lobby, waiting to be ferried to the pier, Shrewsbury simply can’t stop staring at Miss Arkwright. And when her brother—Mr. Arkwright, an Australian millionaire—angrily demands why Shrewsbury is so rudely gaping, Shrewsbury blurts out that it’s because he has seen Miss Arkwright before, as the centerpiece at a bachelor party—the naked centerpiece, no less.

Even today, in most places and most circles, this would be a bombshell announcement, let alone in Victorian England, where people covered up piano legs because they were, well, legs.

Needless to say, trouble ensues!

To Charlotte’s and Livia’s dismay, their mother, Lady Holmes, also finds her way onto the boat. What troubles them about her being there?

On a most visceral level, Livia is dismayed because it tries her soul to be around Lady Holmes, especially as the unmarried daughter Lady Holmes deeply disdains.

Charlotte, who is in disguise and does not have to deal with Lady Holmes as a dutiful daughter, is more concerned about how and why Lady Holmes has turned up on the Provence.

Lady Holmes has no use for foreign travel. And she has no money to afford tickets for herself and her maid. Yet here she is, on a steamer bound for Egypt and India. Who put her on the Provence and what is their purpose?

No Lady Sherlock novel would be complete without Lord Ingram Ashburton. He too is traveling by sea, with his children and their nanny. Will you tell us a bit about his contribution to this story?

This is Lord Ingram’s most prominent outing in the entire series. Charlotte, in disguise, has to maintain a low profile. Which leaves Lord Ingram to participate in the murder investigation in an official capacity, and we will be seeing a good bit of how it unfolds from his point of view.

Last but not least, we have Mr. Gregory, who is assigned to help Charlotte whether she needs him or not, and Inspector Brighton, who has been more adversary than assistant in previous books. What can you tell us about them?

Readers first met Inspector Brighton, a ruthless Scotland Yard investigator, in book 5 of the series. In this book he is headed to Malta to train the local constabulary in modern detection methods and the Provence happens to be his ride. So when the murder happens, the captain asks him to take charge of the matter.

Mr. Gregory is referred to at times as The Great Lover in the book. He is a very handsome older gentleman who has had a storied career as a seducer in the crown’s more clandestine services. 😀

I love this entire series, so I hope Charlotte will accept many more cases. Will she, and will you give us a hint of what mystery will occupy her next?

Thank you! I have just recently signed the contract for books 8 and 9 in the series, so there will be two more books at least.

And I wish I could tell you more about what will happen in book 8, but I am still trying to wrap my own head around what seems a very fractured plot at the moment. (No worries, it’s always like that at the beginning of a Lady Sherlock book.) But from what I have written so far it seems like Charlotte herself might be in a bit of trouble, as in she might have to account for her movements and whatnot to the police.

We shall see!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

It is my very great pleasure. Thank you for having me and thank you for your support of the series!

Sherry Thomas is the author of historical romances, YA fantasy, and the Lady Sherlock series, which begins with A Study in Scarlet Women. Find out more about her at https://sherrythomas.com.

Photograph © Jennifer Sparks Harriman.

March 3, 2023

Defeating Infantile Paralysis

One of the tragic side-effects of the politicization surrounding COVID-19, its origins, and the remarkably rapid development of vaccines aimed at preventing infection has been the resurgence of polio—another highly transmissible, devastating disease that was once close to eradication. In part, the vaccination campaign for polio was so successful that most people now, although they have heard of the disease, have never encountered anyone stricken by it. They have no idea just how terrible—and terrifying—it was in the days when it appeared to be both incurable and impossible to prevent.

One of the tragic side-effects of the politicization surrounding COVID-19, its origins, and the remarkably rapid development of vaccines aimed at preventing infection has been the resurgence of polio—another highly transmissible, devastating disease that was once close to eradication. In part, the vaccination campaign for polio was so successful that most people now, although they have heard of the disease, have never encountered anyone stricken by it. They have no idea just how terrible—and terrifying—it was in the days when it appeared to be both incurable and impossible to prevent.In my latest interview for the New Books Network, Lynn Cullen takes us back to that time in the 1940s when even the world’s most dedicated scientists did not know how polio moved through the body, how it was transmitted from one person to another, and how it wreaked so much havoc on vital organs. In particular, Cullen follows the career of one woman, Dorothy Horstmann, a doctor and medical researcher who devoted her life to finding out how polio worked and where intervention might be successful. She went on to apply the same skills to other illnesses, but only after she devoted more than twenty years to studying the disease known as infantile paralysis, although it did not only affect children. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was one notable example.

It’s a gripping tale, a fictionalized but mostly true story, and one particularly relevant to our time. So give the interview a listen, and then read the book.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The essential contribution of this novel can be summarized in one sentence: like most of its future readers (I assume), I had never before heard of Dorothy Horstmann and her fundamental role in the research that led to the near-eradication of polio, despite having benefited hugely from her work. Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and into the 1960s, she devoted her considerable talents and endless hours to tracking how polio spread throughout the body, but like the other remarkable women portrayed in this novel, she was forced because of her gender to play second fiddle to Doctors Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, her academic colleagues. Their contributions, of course, were also real and worthy of acclaim, but it was Dr. Horstmann—too often dismissed as “Dottie” or “Dot,” as if she were someone’s secretary—who made the crucial discovery that early in its path from the digestive to the nervous system, the polio virus created antibodies in the blood. That finding made the polio vaccine possible by defining an entry point for medical intervention.

Reading this novel has a particular resonance at this moment, when polio outbreaks are again affecting US cities because of vaccine hesitancy and the final eradication of the disease has been deterred in certain countries by political concerns—not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic, which has changed everyone’s experience of quarantine and disease. But I would like to emphasize that this is, first and foremost, a novel, centered on complex characters, a gripping plot, and the age-old battle between science and nature. I don’t know, for example, whether Dorothy’s love interest is a real person or the author’s way of contrasting the attractions of home with the pull exerted by fulfilling work. In the end, it doesn’t matter, because The Woman with the Cure works as a story, provoking questions about the choices its heroine makes and what we might do in similar circumstances—and that’s what counts.

February 24, 2023

Interview with Joanna Lowell

In college, I read romances, both historical and contemporary, by the bucketful. These days, not so much. A romance novel has to have a real hook in terms of characters and plot if it’s to draw me in, and those characters and that plot need to be strong enough that the final falling in love—which is, after all, the most predictable part of a romance novel—seems not only inevitable but part of a resolution to broader problems presented in the story world. If the book also features sparkling dialogue and a sense of humor, I’m hooked.

In college, I read romances, both historical and contemporary, by the bucketful. These days, not so much. A romance novel has to have a real hook in terms of characters and plot if it’s to draw me in, and those characters and that plot need to be strong enough that the final falling in love—which is, after all, the most predictable part of a romance novel—seems not only inevitable but part of a resolution to broader problems presented in the story world. If the book also features sparkling dialogue and a sense of humor, I’m hooked.Artfully Yours is such a book. Nina Finch is a talented artist, but late nineteenth-century English society has little use for women painters, especially those of limited means and reduced social standing. Her brother Jack also has artistic aspirations, but after a series of misfortunes, he has turned his talents to forging the great masters and lured—not to say forced—Nina into helping him. As a result, Nina has redirected her aspirations toward baking Victoria sponges and gooseberry tarts to sell from a shop of her own.

But she can’t turn her back on the brother who raised her, and when it becomes clear that London’s foremost art critic, a duke’s son who goes by the name of Mr. Alan De’Ath (yes, the pun on “death” is deliberate, and he is in reality Lord Alan), has Jack’s forgeries in his gun sights, Nina agrees to accept the position of Alan’s amanuensis so she can keep track of his investigation and save Jack’s neck—and her own. With her pet marmoset, Fritz, she infiltrates Alan’s household, where she runs into a cast of eccentric characters, including a group of woman painters led by a cross-dressing firebrand determined to bend the artistic elite of London to her will.

It's all delightfully tongue-in-cheek, and although we can predict that Nina and Alan are meant for each other, how they will cross the vast divide that separates them remains far from clear well into the book. So too does the family secret, hinted at early on, behind Alan’s ongoing conflict with his aristocratic relatives. And if that’s not enough to draw you in, the antics of Fritz and the many humans desperate to wring a good review out of Alan will keep you flipping pages right to the end.

Joanna Lowell was kind enough to answer my questions, so read on to find out more.

This is your third historical romance set in 1880s England. What draws you to this particular period?

My aunt gave me two big volumes of Arthur Conan Doyle when I was young, so Sherlock Holmes stories were my gateway to late Victorian London. All the gaslights and broughams! I’ve read other things since—novels of the late Victorian period or set in the late Victorian period, and also histories—and I still find the end of the nineteenth century fascinating. That may be partly because I grew up at the end of the twentieth century (1980s/90s). There’s something familiar about the fin de siècle feeling. People looking toward the future and imagining new realities. By 1881, London had nearly five million people. It was by far the biggest city in the world. There was enormous wealth and staggering poverty. Everything was speeding up due to industrialization, which was fueled by exploited workers and by raw materials thieved from the colonies. Class struggle intensified. Imperial wars raged. Women mobilized for political rights. We can see so many throughlines to the present, but it’s very much not our time as well. Different laws. Different social norms. (And of course, the gaslights and broughams!) That tension is very generative for me. I want to write characters that speak to readers now, and I also want to transport readers into the past so they can feel the (fictionalized) historical context come alive.

Some of the characters from the two previous novels are mentioned in passing in this one. Could you give us a quick summary of The Duke Undone and The Runaway Duchess?

The Duke Undone is the story of an aspiring artist from London’s East End and an angsty duke haunted by his demons and struggling to repair a brutal family legacy. They come from completely different places and stations in life, and they meet by chance when Anthony is sprawled passed-out drunk and naked in an alleyway. Lucy paints him from memory, just for herself, but one thing leads to another, and she sells the picture. Anthony sees it and is most displeased. A confrontation ensues, and the two realize they each have the power to help or hurt the other. Lucy is trying to save her condemned home and launch her painting career. Anthony is trying to find his missing sister while seeming to comply with the rules set down in his father’s will. They strike a bargain and get much more than they bargained for.

The Duke Undone is the story of an aspiring artist from London’s East End and an angsty duke haunted by his demons and struggling to repair a brutal family legacy. They come from completely different places and stations in life, and they meet by chance when Anthony is sprawled passed-out drunk and naked in an alleyway. Lucy paints him from memory, just for herself, but one thing leads to another, and she sells the picture. Anthony sees it and is most displeased. A confrontation ensues, and the two realize they each have the power to help or hurt the other. Lucy is trying to save her condemned home and launch her painting career. Anthony is trying to find his missing sister while seeming to comply with the rules set down in his father’s will. They strike a bargain and get much more than they bargained for.

The Runaway Duchess unfolds across the moors of Cornwall. It follows Lavinia, the mean girl introduced in The Duke Undone. She escapes the horrible duke she just married by stealing someone else’s identity. Pretending to be another person makes her think more deeply about who she is. She realizes that she wants to change, and that she’s falling for the man she’s deceiving—not a great way to begin a relationship! (Even if you’re not a runaway bride.) Neal is true-hearted and sunny and doesn’t want to play games or get involved with a spoiled London socialite. He hopes to settle down with a fellow botanist. When the truth comes out, he and Lavinia are already too entangled for either of them to walk away, but finding a way forward requires a whole new order of growth.

The Runaway Duchess unfolds across the moors of Cornwall. It follows Lavinia, the mean girl introduced in The Duke Undone. She escapes the horrible duke she just married by stealing someone else’s identity. Pretending to be another person makes her think more deeply about who she is. She realizes that she wants to change, and that she’s falling for the man she’s deceiving—not a great way to begin a relationship! (Even if you’re not a runaway bride.) Neal is true-hearted and sunny and doesn’t want to play games or get involved with a spoiled London socialite. He hopes to settle down with a fellow botanist. When the truth comes out, he and Lavinia are already too entangled for either of them to walk away, but finding a way forward requires a whole new order of growth.

Neal is best friends with Alan De’Ath, the art critic. Alan plays a role in the last quarter of The Runaway Duchess. He’s the hero of Artfully Yours, which brings the series back to the London art world.

Introduce us to your heroine, Nina Finch. What does she want out of life, and what is her reality when the novel opens?

Nina wants peace and quiet, a life that’s simple and sweet and free of risk. Her dream is to run a village bakery. She’s practical and organized, and she has it all planned out. The problem isn’t that she doesn’t know her own mind, it’s that her heart tells her she can’t leave her brother. Jack raised her after their mother died. When the novel opens, they’re living in a noisy, chaotic curiosity shop. Jack has a forger’s workshop upstairs. He trained Nina to paint in the style of Old Masters, and they make their living off their forgeries. This means there’s always the threat of discovery and punishment hanging over their heads. It’s horribly anxious-making for Nina. She worries for Jack, and that worry—along with her powerful loyalty—makes it difficult to imagine leaving unless he comes with her.

How did Nina’s brother Jack wind up in his current predicament?

Jack would say it’s because the deck was stacked against him from the start. He was as talented as his fellow students at the Royal Academy of Art but, unlike most of them, he lacked financial resources. Stepping up to care for Nina meant that he had to change how he was living, and ultimately led to his losing his place at the Royal Academy. He and Nina both understand this as a major sacrifice, one that bonded them together and put Nina in his debt. Jack realized he could make the most money forging art, and so he established himself in the Royal Academy’s shadow. He got caught fairly early on, and his experience in prison made him angrier and left him with even fewer options, so he went back to forging, with Nina’s reluctant help. I don’t entirely disagree with Jack’s social critique, but his refusal to take responsibility for his decisions and the way he manipulates Nina create a central tension in the book.

Alan De’Ath is in every way Nina’s opposite. Without giving away any of his secrets, give us a sense of him at the moment when he enters her life.

Alan is an art world insider, one of the most respected critics in England. He thrives in London’s elite and bohemian circles. Born into an aristocratic family, he inhabits a place of privilege, operating with confidence and social ease. For all that, he’s a very guarded person. He has dozens upon dozens of friends and acquaintances, but he’s careful to show them only what he wants them to see. He uses humor as a mask. When he meets Nina, things have just started to crumble. His extremely troubled family relationships (past and present) are threatening his ability to live the life he built for himself. He’s trying to use his wits, as usual, to fix the situation. Only in this case, he’s going to have to dig deeper, and that terrifies him. He felt vulnerable once and doesn’t want to feel that way ever again. This avoidance is going to compound his problems.

Tell us, please, about the Sisterhood and the part they play in this novel.

The Sisterhood is a group of women artists that Lucy Coover (heroine of The Duke Undone) started with her friends while they were students at the Royal Academy of Art. They’re dedicated to making art education more equitable for women, and to supporting each other and other women in the art world. They’re friends with Alan, and so Nina finds herself interacting with them. They’re the first contemporary artists she’s ever known, and meeting them forces her to see forgery in a new light. It also gives her a glimpse into a way of living that appeals to her and that she never thought possible for herself.

And perhaps Fritz deserves an introduction. What made you decide to include a marmoset?

Many of the human relationships in Nina’s life have been changeable and explosive, so she feels particularly close with her animal friends. I wanted her to have one comrade in particular that traveled around with her, providing support and also causing some mischief. Virginia Woolf lived with a marmoset named Mitz. Sigrid Nunez wrote a wonderful book about her, Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury, which I highly recommend. I created Nina’s marmoset, Fritz, in homage to Mitz. The animals most present in my life at the time of writing were the neighborhood squirrels, so Fritz has some squirrel in him as well.

Many of the human relationships in Nina’s life have been changeable and explosive, so she feels particularly close with her animal friends. I wanted her to have one comrade in particular that traveled around with her, providing support and also causing some mischief. Virginia Woolf lived with a marmoset named Mitz. Sigrid Nunez wrote a wonderful book about her, Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury, which I highly recommend. I created Nina’s marmoset, Fritz, in homage to Mitz. The animals most present in my life at the time of writing were the neighborhood squirrels, so Fritz has some squirrel in him as well.

For all the sparkling humor—of which there is a good deal—Alan makes an important point about forgery and its effect on art. Could you summarize that for us, please?

Jack sees forgery as a victimless crime. So long as the fake isn’t discovered, buyer and seller both get what they want. Where’s the harm in that? Alan thinks that forgery harms art itself, that allowing a fake Rembrandt to stand as a real Rembrandt does a disservice to our understanding of what makes painting matter. But beyond that, he thinks forgery hurts living artists. There was a growing demand for artworks by famous dead painters in the nineteenth century. This was linked to the rise of national museums and business elites who wanted to establish prestige through private art collections, and forgers took advantage of the opportunity, creating fakes galore, which fed the buying frenzy. Alan wishes this would all settle down, and attention could turn to riskier, contemporary work, such as the paintings and sculptors by the members of the Sisterhood. Fewer forgeries of old stuff, more room for new stuff.

What are you working on now?

A beach-set queer Victorian romance. It’s part of the same series. There’s more art, there’s also lots of seaweed, and bicycles with big front wheels.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Joanna Lowell lives among the fig trees in North Carolina, where she teaches in the English department at Wake Forest University. She is the author of The Duke Undone, The Runaway Duchess, and Artfully Yours. When she’s not writing historical romance, she writes other things as Joanna Ruocco. Find out more about her at https://www.joannalowell.com.

Images: William Powell Frith, A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881 public domain, and photograph of a marmoset © Carmem A. Busko CC BY 2.5, both via Wikimedia Commons.

<font size="4"><span style="font-family: georgia;">@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536869121 1107305727 33554432 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0pc; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; font-family:Symbol; mso-ascii-font-family:Symbol; mso-fareast-font-family:Symbol; mso-hansi-font-family:Symbol;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</span></font>

February 17, 2023

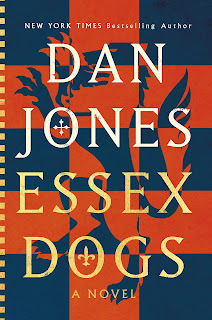

Interview with Dan Jones

Despite having interviewed Bernard Cornwell three times for the New Books Network, and as a result having enjoyed all of his Saxon Chronicles, I am not a big fan of war books in general. So I agreed to read Dan Jones’s

Essex Dogs

, which released this past Tuesday, with some trepidation. I was pleasantly surprised.

Despite having interviewed Bernard Cornwell three times for the New Books Network, and as a result having enjoyed all of his Saxon Chronicles, I am not a big fan of war books in general. So I agreed to read Dan Jones’s

Essex Dogs

, which released this past Tuesday, with some trepidation. I was pleasantly surprised.For those who love gritty descriptions of battles and campaigns, behind-the-scenes peeks at the daily life of soldiers in all its filth and profanity, and the push-and-pull between the medieval equivalent of enlisted men and their noble officers, there is plenty here for them to love. Dan Jones is first and foremost a historian, and his grasp of the details and his easy confidence in describing scenery, events, and the many hardships of a military operation on foreign soil make for a compelling tale. The novel follows the English army during its first major campaign of the Hundred Years War, from its landing on the coast of Normandy to the crucial battle at Crécy in August 1346. Suffice it to say that several historical characters—including King Edward III’s son, the chivalric hero known as the Black Prince—appear in an unfamiliar but amusing light.

The story moves fast, and the main characters—a small group of fighting men who call themselves the Essex Dogs—emerge as distinct individuals, each with his own past, personality, and problems. But it is their leader, variously referred to as FitzTalbot and Loveday, who dominates the story. On the rebound from personal tragedy, in a struggle to stay alive under difficult circumstances, and intent on fulfilling what he perceives as a sacred trust from the group’s prior leader, known only as the Captain, Loveday is determined to keep his small group together no matter what fate throws at them.

What follows is an interview between Dan Jones and his publicist, Ben Peterson (questions in bold). Although I normally insist on conducting my own interviews, I made an exception in this case because Ben has asked the same questions I would have, so it seemed pointless to require a busy author to spend time repeating himself.

You’re best known for writing books about British history. What prompted and inspired you to write your first novel, Essex Dogs, and why now? How did you prepare?

For some years I’ve been yearning to try my hand at fiction set in the Middle Ages. And plenty of my readers had been asking me when I was going to get around to doing it. As though it were the obvious natural progression in my career. I suppose it figures. My nonfiction books are built on narrative structures borrowed from screenwriting. They celebrate character and explore history through strong, colourful scenic narrative. They smuggle big ideas in under the guise of in-your-face entertainment. These are traits shared with fiction.

I conceived this novel in several stages. The idea of writing about a rogue band of freebooter-soldiers known as the Essex Dogs came to me while I was dozing on a flight from Prague to London in 2017. I began writing about them, but could not settle on the right adventure for them to have. So I shelved the project, and forgot about it until the winter of 2018/2019, when I rented a house in Normandy, quite near Saint-Lô. During a New Year’s Day walk on Omaha Beach with friends, I began to think that having the Dogs take part in Edward III’s 1346 landing a little further up the coast (near Utah Beach) might be viable and fun. A medieval D-Day, kind of like Saving Private Ryan but in fourteenth-century costume. Medieval American hardboiled. Yeah. That felt cool.

Yet even then I dithered. It was not until that summer, after a wide-ranging conversation over dinner with George RR Martin, a history lover whose works of fiction I admire enormously, that something clicked. I went home and started work. George had nothing to do with the writing of this story. His contribution ended at being an inspiration and a personal hero. But it was an important contribution all the same.

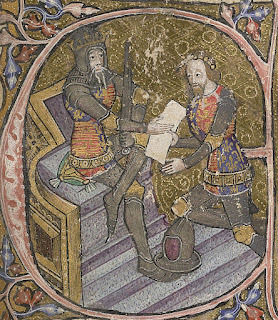

The novel is based on the Hundred Years’ War. How much of the book is based on actual events, and which parts are complete fiction? Which characters really existed, and who’s invented? Did the Essex Dogs and its members really exist?

The Crécy campaign of 1346 is every bit a real historical campaign. On 12 July Edward III—who claimed to be the rightful king of France as well as England—landed 15,000 men on the Normandy beaches. It was his “medieval D-Day.” For the weeks that followed, his troops marched and burned and pillaged their way through Normandy, raiding cities and indulging in a chevauchée—a terror campaign designed to frighten and intimidate French people and to disillusion them with their leaders. (This is exactly the same tactical approach to warfare that Vladimir Putin adopted in the first weeks of the recent invasion of Ukraine.) The English came within a few miles of Paris, before forcing a crossing of the river Seine and then heading north towards the Somme, now pursued by a hastily assembled but very large French army. The two armies collided near the Forest of Crécy in late August. It was a spectacular battle with an improbable outcome.

So that much is known. But the historical accounts we have for these events are mostly written either by royal/noble/clerical/knightly participants in the war; or else by chroniclers sympathetic to such a class of people and interested in the ideals of chivalry rather than the “ordinary” experience. It would be impossible to write a straight nonfiction book about the adventures of a medieval Easy Company—such as the Essex Dogs are—because there are no soldiers’ diaries from this age. That’s why I chose fiction and elected in my approach to invent an imaginary “platoon” but have them interact with real historical characters such as King Edward, his son the Black Prince, the earls of Warwick and Northampton, and so on. It’s a similar approach to that adopted by one of my favourite American writers of historical fiction, James Ellroy. Think of American Tabloid: the three viewpoint characters are running blind through history, running into grotesque imagined versions of the Kennedy brothers, J. Edgar Hoover, Jimmy Hoffa, Howard Hughes, etc., etc. My Essex Dogs do exactly that, only in the white heat of a war for medieval France.

What was your process for weaving together fact and fiction? How did you create dialog and what research and sources were involved? Did you learn anything new or come across something that surprised you?

Well, as I’ve hinted above, all the plot points in Essex Dogs are real. I’ve pulled them from the sources of the time, which I know pretty well: we’re talking chronicles, letters, administrative records, and such. At the start of each chapter I’ve inserted snippet quotes from those sources to show you how fact and fiction intersect. But the Essex Dogs, my imaginary platoon, come at the events from a perspective not seen/cared about by the men who wrote those original sources. So there are many times when, in exploring the ordinary soldier’s view of events, my chapters run deliberate counterpoint to the official history. That also means there are a ton of Easter Eggs and jokes hidden in the text for aficionados who know their medieval history. (It doesn’t matter if you don’t spot them, it won’t spoil the read.)

As for dialog, that’s a really interesting point. There is no way to accurately mimic fourteenth-century speech on the page and remain intelligible to approx. 99.89% of modern readers. I also loathe the affected “Hollywood” rendering of “ye olde” dialog, which is about weird passive verb structures, phoney formality, and vaguely archaic vocabulary. For example, “be not troubled, my liege, the French want not this fight, I warrant.” Ugh. Gross. And lame.

I approached this as a translation task. Dialog in Essex Dogs is blunt, modern, often bracingly military and somewhat profane. The main concession I’ve made to fourteenth-century manners of speech is to include a colourful repertoire of high blasphemy—for in the later Middle Ages, cursing was done by references to God’s wounds or St Anthony’s bloody toenail, rather than leaning on scatology and urology. I had a ton of fun doing that. A TON. Maybe too much. You will have to be the judge.

Which characters did you enjoy writing the most and why? Which parts of the novel were the most challenging to write?

In light of the above, the earl of Northampton was my favourite. He’s the one noble character in the book who speaks a language the “grunts” can understand. Think General Patton’s speech to the Third Army in 1944, and you’ve got the general idea. When we first meet Northampton, he seems to be quite an atrocious individual because he doesn’t sugar-soap his speech like the other nobles do. Yet as the story goes on we learn that this man, the constable of the army (therefore roughly the fourth in chain of command), is the only one who can really communicate—and even sympathise—with the ordinary troops. And he’s prepared to put himself in harm’s way to lead them. I kind of love the guy, and I definitely lit up whenever he walked into a scene.

That being said, Northampton is not one of the Essex Dogs, and they were obviously my viewpoint characters. I spent most time living inside the head of Loveday, the leader, who is nursing a lost love and a lost brother-in-arms. Loveday consistently conveys the deeper themes of the book that transcend the period—about loyalty and regret, about the uncomfortable conflict between what you might call toxic masculinity and the deep-rooted male urge to be a good role model—a heroic father-figure and a brother. So he’s very dear to me. So too is Romford, the sixteen-year old, very damaged, very abused, a fiend and an addict, a sexually uncertain teenager figuring out a brutal world, but also at times just a tender little boy. Romford was the one who made me cry. When I was writing the last three chapters of the book I cried so much I almost shorted out the electronics on my laptop. Romford did that.

What are some of your favorite historical novels, and what about them do you find appealing?

Well, I mentioned Ellroy already. His American Underworld trilogy (American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand, Blood’s A Rover) made a huge impression on me when I read it—it was a different sort of historical fiction than I’d seen before. Don Delillo’s Libra I guess kind of the same thing. I love Mary Renault’s visions of the Bronze Age world—her book The King Must Die took the Minotaur story and told it like nothing I’d ever known. Of course, right now there’s a really interesting creative moment around the Middle Ages, particularly among American writers, who I suppose are drawn to previous ages of great change when it felt like DOOM was coming down the line pretty fast. Lauren Groff’s Matrix and Otessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona impressed me. Then, of course, there are the medieval big guns. Bernard Cornwell has given me some great advice on the couple of occasions we’ve spoken, and I think his work is sensational. I’m a big admirer of Ken Follett. George RR Martin—goes without saying. What connects them all? World-building. Heart. Thrills. Ideas.

Essex Dogs is the first novel in a trilogy on the Hundred Years’ War. What do you have in mind for the other two novels?

Volume 2 is called Wolf Moon. It follows continuous from Essex Dogs. Only now, rather than marching into the unknown, the Dogs find themselves caught up in the siege of Calais—a brutal eleven-month blockade of a small port on the French coast.

Why are they there? Why does the king care so much about taking it? What are they really fighting for? All this will be revealed as in Wolf Moon we peel back another layer of the war and discover who really wants it to last for a hundred years.

Wolf Moon is about money, merchants, and the medieval “deep state,” which cares nothing for chivalry or the loyalty to kings, only about the naked pursuit of power and profit. We will travel inside and outside Calais, from the siege city built outside the walls, to the pirate ships patrolling the harbour, and into the dark corners of oligarchs’ houses, where the deals that shape—and end—lives are made.

And at the end, we hear the first, faint, chesty rattle of a natural disaster that is sweeping towards the Dogs and their world—and which will set the stage for the epic third book in the series, The Last Knight.

When can we expect your next nonfiction book and what will you be taking on?

I’m writing a biography of Henry V. It’s the missing link between my big chronicles of medieval England: The Plantagenets and The Wars of the Roses. It’s a huge project and a challenge. But that’s the way I like it.

Images: Miniature of Edward III granting Aquitaine to his son, Edward the Black Prince, and of the Battle of Crécy from the Chronicles of Jean de Froissart public domain via Wikimedia Commons; map of Edward III’s chevauchée in Normandy in 1346 CC-BY SA 4.0 Goran tek-an, via Wikimedia Commons.

February 10, 2023

The Other Side of the Desk

One of the perks of having hosted New Books in Historical Fiction for more than ten years—as long as I’ve been publishing novels, although both twists along the road of life seem like turns I took yesterday, not in 2012—is that once in a while I get to shift gears and talk with one of the other hosts about a new book of my own. With Song of the Storyteller officially released as of January 17, the time has come to let the world know of its existence. G.P. (Galit) Gottlieb, the host of New Books in Literature and the author of three charming contemporary novels collectively known as the Whipped & Sipped Mysteries, offered to conduct this interview. It went live just before January gave way to February, and you can find the results at both the New Books Network (NBN) and various podcast subscription services such as Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

One of the perks of having hosted New Books in Historical Fiction for more than ten years—as long as I’ve been publishing novels, although both twists along the road of life seem like turns I took yesterday, not in 2012—is that once in a while I get to shift gears and talk with one of the other hosts about a new book of my own. With Song of the Storyteller officially released as of January 17, the time has come to let the world know of its existence. G.P. (Galit) Gottlieb, the host of New Books in Literature and the author of three charming contemporary novels collectively known as the Whipped & Sipped Mysteries, offered to conduct this interview. It went live just before January gave way to February, and you can find the results at both the New Books Network (NBN) and various podcast subscription services such as Spotify and Apple Podcasts.This isn’t my first interview for the New Books Network. I previously talked with Joan Schweighardt about The Swan Princess and with Galit about Song of the Siren and Song of the Sisters. You can find those previous conversations, if you’re interested, by searching for C. P. Lesley on the NBN site. Each time, I gain more insight into how my guests may feel when it’s their turn at the far side of the microphone—or, more often, just the receiving end of a telephone call. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I was shy as a teenager, and although I thought I had conquered that particular source of anxiety, my first forays into podcasting terrified me.

That was 140 or so interviews ago, and I have long since learned to take the host position in stride. But I was surprised by how nervous being a guest still makes me. That was especially true this time, because it was my first wholly unscripted conversation: I had no idea what Galit would want to know. And like many historians, I tend to ramble, so I worried that I would go down a conversational rabbit hole and emerge twenty minutes later to the online equivalent of glazed eyes.

Of course, none of that happened. Long before we actually started recording, I had relaxed into chat mode. Galit was as delightful as ever; she asked wonderful questions, and I mostly managed to rein my naturally discursive tendencies while answering. I didn’t say everything as perfectly as I would have liked, or tip my hat to every nuance, and I hem and haw more than I would have thought possible. But I did manage to get at least a few big points across. And the next time a guest forgets what she meant to say or tells me how nervous she is, I will be able to extend my condolences and assure her that I know exactly what she’s going through.

Galit and I talk mostly about the historical backdrop of the novels: the boyar politics, the religious differences, the bride show itself, a few of our favorite characters, what’s next for the series. So whether you listen to the interview first (you can find it at the link above) or read the book and then listen, I hope you’ll enjoy them both for different reasons.

You’ll also find out a little more about me, my background outside fiction, how I came to write these novels, and why I use a pen name to do so.

Image: Song of the Storyteller ad © C. P. Lesley; Ivan IV’s first bride show, from the 16th-century Illustrated Chronicle Codex (Litsevoi letopisnyi svod), public domain via Wikimedia Commons; covers for G. P. Gottlieb’s novels © D. X. Varos, reproduced under the fair use doctrine.

February 3, 2023

Finally, a Truce

Well, it took fifteen weeks, a mesh screen door, a ton of patience, and even a couple of Eagles victories, but I’m happy to report that my older cat, Mahal, has more or less agreed to live and let live with the kittens introduced into her life, against her will, in mid-October.

It helps, I’m sure, that the boys have quadrupled in size during the intervening four months and can now defend themselves if need be. If nothing else, knowing that they can hold their own makes us more comfortable with the idea of letting the threesome work it out without human interference. Decades of living with cats have taught me much about how to read their behavior, but I’ve also developed a deep appreciation of how much I don’t know about how cats communicate with one another.

The crucial turning point, in this case, seems to have been time—assisted by that mesh screen door. Made of nylon, it includes zippers and attaches to the existing frame, allowing people to pass through at will and cats to see, hear, and smell one another. In this case, we set it up in the room where the kittens had spent their first two weeks, so that most of the furnishings already bore their scent. Mahal had her own food and water dishes, her own cat box, a steady supply of Feliway pheromones (not sure how much difference those actually made, but they are supposed to calm cats), and frequent visits from her humans. She could watch us as we went about our daily tasks and, most important, interact with the kittens but not attack them.

They, in turn, were forced to respect her space, dialing down the opportunity for conflict. (I would be the first to admit that Mahal had ample cause for complaint, since the boys thought nothing of cleaning out her food dish, drinking up her water, or soiling her cat box.)

You may wonder why we put Mahal behind the screen, when she was the long-time resident. The answer is two-part. First, she was the one whose behavior we wanted to modify, and shutting them up and leaving her the run of the house would convince her she had won the day rather than give her an incentive to change. But more fundamentally, kittens are like children. They’re busy figuring out the rules of their world and what’s expected of them. The last thing we wanted to do was convince them that they should spend the rest of their lives immured in a single room. Instead, we wanted them to feel comfortable exploring and bonding with us—just as Mahal already did and continues to do.

At first, she did her best to leap at them whenever they appeared. The first time we let her out, she hunted for them and attacked them, and we had to return her to her cave. But then something interesting happened. She started calling for attention.

Was she calling for the kittens? I don’t know. But the kittens were the ones who responded, dashing from wherever they happened to be to station themselves outside her door. Throughout December and January, the three cats gradually moved closer, even touching noses through the screen. The next time we let Mahal out, she hissed only once, when Rafi—who has made it his prime objective to climb the screen and break into her room—dashed in the moment the door came down, then ran past her on his way back out again. And last Sunday, when we let her out again, we could watch her and the boys sussing each other out, advancing and retreating, visibly testing how close they can get to each other without crossing a boundary only they can see.

And that’s the main thing we wanted: a détente. Knowing Siamese, I suspect they will eventually snuggle on the couch, but if we can maintain “no teeth, minimal claws,” the rest can develop at its own pace—or not. A cold war is better than a hot one, and a working truce better still.

So here I raise a glass to Mahal. It’s not easy dealing with such a fundamental change when you’re the cat equivalent of seventy-five. Some great cat treats and a nice belly rub for you. And despite the occasional setback—such as the one that occurred a few days after I drafted this post—we feel confident we will get you through this, sooner or later.

Images: Mahal relaxing on the couch, sending good thoughts to the Eagles, who had just won their division title; Rafi (front) and Ruslan relaxing while they wait for the next summons—both © 2023 C. P. Lesley.