C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 5

June 16, 2023

Making Stuff Up

I’ve made no secret of the fact that one reason I chose to set my historical novels during the childhood of Ivan the Terrible—who became the nominal ruler of Russia a few months after his third birthday and held the throne until his death at fifty-four—was because the history of that period is so dramatic that the stories almost tell themselves. When I began, I intended to start not long after Ivan’s accession to the throne and end with the suspiciously convenient death of his mother, Grand Princess Elena Glinskaya, four and a half years later. That is, indeed, the span of my first series, Legends of the Five Directions.

But when I found myself with a group of characters whose stories I’d planned to tell but had no room for—having had entirely unrealistic ideas of just how much I could cover in a single book—I was having too much fun to quit and decided to bring the series forward into the even more troubled and chaotic years that followed Elena’s death. That brought me, in due course, to the bride show held for the by then sixteen-year-old Ivan and, as of the current novel, the Great Moscow Fire that followed it. Or more accurately, as I discovered when I began to research the topic, not one fire but a series of three that wreaked havoc on Moscow from mid-April to late June, killing thousands and destroying the livelihood of many more.

This was sixteenth-century Europe, so governments thought nothing of catering to the wealthy and ignoring the woes of the poor. But in this case, so many people lost family members as well as all their belongings that the survivors lost patience with the callousness of those in charge and rioted in the streets. And because this was a time when people liked to blame their misery on sorcery, rumors circulated accusing the tsar’s grandmother, a Serbian princess (rightly or wrongly, Serbians were considered particularly likely to indulge in witchcraft), of turning herself into a bird and flying over Moscow, dripping liquid derived from a human heart to set the city ablaze.

An incredible story, to be sure, and from a historical standpoint highly questionable, not only because of its content but because of when the story appears in the official annals. If I were writing an academic article, I would exhibit extreme skepticism, mining the tale for evidence of who might have gained from spreading such nonsense decades after the last embers of the Great Fire fizzled into ash.

But I’m writing a novel, and the story is wonderfully indicative of how people dealt with trouble back then (and sometimes even today). The question for me is, as always, how to blend the lives and thoughts of my fictional characters into the broader historical arc created by the royal coronation and wedding, followed so closely by the near-destruction of Moscow.

Like most of us, my characters aren’t anticipating disaster; their problems, however important to them, seem quite small next to the larger drama playing out behind them. Yet they must interact with that bigger world, using outside events to solve their issues and get to where they need to go. How do they cope with tragedy? What strengths and weaknesses do they reveal? Do they resist the pressure of the maddened crowd or give in to the prejudices of their day?

I don’t know yet. But I’m about to find out. No doubt Yuri and Anna, like their predecessors, will surprise me. Just a few days ago, a cat showed up in the story and demanded, as cats will, a place at Anna’s side. I have yet to discover what role Mila the Cat will play, although I’m sure she will tell me when I need to know.

But as I write in almost every historical note, the most outrageous events in my novels are almost always historically attested. The old adage really is true: you can’t make this stuff up, because no one would believe you if you did.

As for the most outrageous coincidence in this particular novel, I think I’ll save that for a future post.

Because of changes to Wix, which hosts my main author website, and my own desire to consolidate my author persona in one secure location, I will be transferring my blog to my main site, https://www.cplesley.com, at the end of June 2023. The older posts—dating from June 2012!—will continue to be archived here for as long as I can make that happen.

Image: Apollinary Vasnetsov, Boyar Houses at Night (1918) looking distinctly smoky, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

June 9, 2023

Reimagining Tragedy

I encountered Katharine Beutner’s new novel,

Killingly

, through a NetGalley recommendation and was instantly hooked. I graduated from Mount Holyoke College, and although that was a long time ago now, I still have fond memories of South Hadley and its environs. But I had never heard of this case of a missing student, either when I lived on the campus or in the years since. Fortunately, the author agreed to speak with me for a New Books Network interview, which posted just this week, around the time of the book’s release.

I encountered Katharine Beutner’s new novel,

Killingly

, through a NetGalley recommendation and was instantly hooked. I graduated from Mount Holyoke College, and although that was a long time ago now, I still have fond memories of South Hadley and its environs. But I had never heard of this case of a missing student, either when I lived on the campus or in the years since. Fortunately, the author agreed to speak with me for a New Books Network interview, which posted just this week, around the time of the book’s release.To be clear, this novel draws on a historical event, and some of the characters and details are also historical. But the book itself is, as advertised, a psychological thriller that includes fictional characters and a lot of (fascinating) speculation about what happened to Bertha Mellish, the missing student, and what might have been going on in her family that precipitated the story events. Read on—and, of course, listen—to find out more

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

In 1897, a Mount Holyoke College junior named Bertha Mellish disappears from campus overnight, leaving no word for her family. It’s a time when female college students are still considered “queer” (in the old sense of peculiar as well as the modern understanding of the word), although the college administrators insist that their primary purpose is to produce excellent wives and mothers. But even this community of oddities considers Bertha strange, by which the other girls mean that she pays too little attention to parties and boys, too much to her schoolwork and social causes.

Bertha’s only true friend is Agnes Sullivan, a young woman from a poor Boston family who has been forced to conceal her Catholic upbringing to gain admission to the college. Agnes, a would-be doctor (an even greater anomaly in late 19th-century culture than a woman with a college education, although not inconceivable), grieves Bertha’s absence but insists she has no idea where Bertha might be. Dragging the rivers and lakes turns up nothing, supposed sightings of the missing girl lead nowhere, and the police would be willing to write the case off as closed if only her relatives and the family doctor would let it go.

Almost from the beginning, it’s clear that Agnes knows far more than she lets on, but finding out what really happened to Bertha and why is a long, winding trail of suspense. Through the overlapping stories of Agnes, Bertha’s sister Florence, Dr. Henry Hammond, and the inspector whom Hammond hires to find the missing girl, Katharine Beutner keeps us on the edge of our seats as she unravels their tangle of secrets and lies. Perhaps the most intriguing element is knowing that however fictional the plot and many of the characters, the story derives from the real-life disappearance of a Mount Holyoke student in 1897, the mystery of which has never been solved.

Image of Mount Holyoke College’s Seminary Hall in 1886 public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

June 2, 2023

Interview with Amy Barry

As detailed by Amy Barry in her latest historical romance—

Marrying Off Morgan McBride

, released just this week—Epiphany Hopgood, better known as Pip, has been having a hard time finding a husband in her small home town of Joshua, Nebraska. It’s 1887, and a woman’s future is pretty much limited to husband and children. So at the “ripe” age of 22, Pip is desperate enough to answer an ad in Matrimonial News for a mail-order bride, even though the man advertising describes himself as a “bullheaded backwoodsman with a surfeit of family.” After all, he wants a woman with a mind of her own, and Pip has that. He wants a good cook, and if there is one area where Pip excels, it’s in the kitchen.

As detailed by Amy Barry in her latest historical romance—

Marrying Off Morgan McBride

, released just this week—Epiphany Hopgood, better known as Pip, has been having a hard time finding a husband in her small home town of Joshua, Nebraska. It’s 1887, and a woman’s future is pretty much limited to husband and children. So at the “ripe” age of 22, Pip is desperate enough to answer an ad in Matrimonial News for a mail-order bride, even though the man advertising describes himself as a “bullheaded backwoodsman with a surfeit of family.” After all, he wants a woman with a mind of her own, and Pip has that. He wants a good cook, and if there is one area where Pip excels, it’s in the kitchen.But when Pip reaches Montana, she discovers that her bridegroom, Morgan, has no idea she exists. And as we might expect, things go downhill from there. But the whole journey, including its final resolution, is tremendous fun. Amy Barry was kind enough to answer my questions, so read on to find out more.

This is your second historical romance featuring the McBride family. Could you tell us a bit about the first, Kit McBride Gets a Wife?

It’s 1886, and the four McBride brothers live high in the Elkhorn Mountains of Montana, raising their irrepressible little sister Junebug, who has had more than enough of looking after a passel of grumpy mountain men. She’s sick of doing their laundry and of cooking and cleaning for them. So she secretly orders up a mail order bride for Kit, her hulking blacksmith of a brother. A brother who cares more for book reading than finding a wife to help Junebug out. But Junebug has no plans to sell some poor woman a false bill of goods—she tells the truth about her brother—snoring, cantankerousness, and all. When Maddy Mooney arrives in their mountain meadow, she’s not what any of them expected. But she might be exactly what Kit (and his little sister) needs.

It’s 1886, and the four McBride brothers live high in the Elkhorn Mountains of Montana, raising their irrepressible little sister Junebug, who has had more than enough of looking after a passel of grumpy mountain men. She’s sick of doing their laundry and of cooking and cleaning for them. So she secretly orders up a mail order bride for Kit, her hulking blacksmith of a brother. A brother who cares more for book reading than finding a wife to help Junebug out. But Junebug has no plans to sell some poor woman a false bill of goods—she tells the truth about her brother—snoring, cantankerousness, and all. When Maddy Mooney arrives in their mountain meadow, she’s not what any of them expected. But she might be exactly what Kit (and his little sister) needs.Kit and Morgan’s sister, Junebug, is the motivating factor in both novels. What makes her so determined to find wives for her brothers?

Junebug is no one’s fool, and she’s certainly no one’s maid or wife. So why should she act the housewife for her brothers, doing all the womanly chores? As far as she can see, they need wives to milk the cows and cook their dinners and wash their pestiferous underwear. And Junebug needs a woman or two around. Because no girl wants to be outnumbered by mountain men. Especially mountain men like her brothers, who are grumpy in the extreme and never let her go fishing when there are chores to be done, and there are always chores to be done.

Junebug herself is a wonderful character. Tell us a bit about her.

Junebug’s mother died when she was young, and her father ran off and left her in the care of her four older brothers, rough mountain men who didn’t have the slightest clue about raising a girl. Morgan is the eldest, and he’s been Junebug’s rock through her hardest days. Even if he is a captious, nagging, irascible blockhead of a parental figure. Junebug is a force of nature, completely untamed, without any citified manners. She’s wilier than her brothers, with less scruples, and a much bigger vocabulary. They don’t stand a chance.

Introduce us, please, to Epiphany (Pip) Hopgood. We know early on why she answers the advertisement for a mail order bride, but what is it about her personality that makes her the perfect heroine for your purposes?

Pip has always been too much for her hometown. She’s too tall, too big, too loud, too opinionated. She’s like a square peg in a round hole. After being rejected by every single eligible bachelor in the county (even the ones old enough to be her grandfather), Pip begins to wonder if maybe it’s not her that’s the problem. Maybe it’s the men. So she’s on the hunt for a man who doesn’t mind “too much” woman. She’s more than a match for Morgan McBride. In fact, she’s even more than a match for Junebug. Maybe …

The men in Joshua, Nebraska, spurned Pip as a potential bride, mostly because of her looks, but Morgan feels differently. What does he see that they missed?

Morgan isn’t looking for dainty and girly and mannered. He doesn’t care a fig for a frilly pink dress and a well-turned ankle. He’s a rougher sort of man, the kind used to being holed up for the winter in a cabin with a bunch of mountain men. When he meets Pip, he doesn’t see any of her “flaws” as flaws. In fact, her height, sharpness, quickness, and stubbornness knock him flat. And if he doesn’t like the feeling … well, he certainly can’t resist it …

What does Morgan really want out of life, since he’s clearly not looking for a wife?

Morgan inherited a bunch of kids to raise after his ma died, and he’s been chafing under the responsibility ever since. He longs to get them raised so he can light out of the mountains and live a life alone on the trail, free. He’s spent six years playing parent, with no one who understands the burden he carries, and he’s sick of it. He wants to be responsible for no one and to no one. Or so he tells himself.

The trip to Buck’s Creek is as eventful for Pip’s grandmother as it is for Pip herself. What does Granny Colefax hope to gain from the journey to Montana?

Pip’s grandmother is a firecracker of a woman who has no intention of being stored in the attic like a bit of old furniture now that she’s aging. She takes the opportunity to chaperone Pip as a chance to run away from her staid life back in Nebraska. She’s going to start anew, and that includes remembering how it feels to be a woman and doing a bit of courting. She’s letting her hair down and showing her granddaughter how life should be lived. One mountain man at a time.

The end of this novel indicates that Junebug hasn’t entirely given up on her matchmaking. Are you working on the next book now, and what can you tell us about it?

Oh, I’m hoping you’ll get to come back to Buck’s Creek again soon. Let’s just say, Beau and Junebug get into a little competition over who can find the best mail order bride, and it gets out of hand. There might not be one, or two, but maybe Seven Brides for Beau McBride. Fingers crossed, readers like the McBrides enough to want more marital mayhem!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

My very great pleasure!

Amy Barry writes sweeping historical stories about love. She’s fascinated with the landscapes of the American West and their complex long history, and she’s even more fascinated with people in all their weird, tangled glory. Amy also writes under the names Amy T. Matthews and Tess LeSue and is senior lecturer in creative writing at Flinders University in Australia. Find out more about her books at https://amy-barry.com.

Images of cowboy (1888) and a cattle ranch in the Elkhorn Mountains of Montana public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 26, 2023

Interview with Alison Goodman

Like Alison Goodman, as she notes below, I first encountered Regency London through the novels of Georgette Heyer, which I discovered in my early teens. Even now, I go back to my favorites every so often, although as I have matured, so have my views on which stories I consider favorites.

Like Alison Goodman, as she notes below, I first encountered Regency London through the novels of Georgette Heyer, which I discovered in my early teens. Even now, I go back to my favorites every so often, although as I have matured, so have my views on which stories I consider favorites.Heyer wrote her first novel at eighteen, and her early heroines were teenagers. Over the course of her long life, the heroines aged into their twenties, but women over thirty remained bit players—chaperones, governesses, and, worst of all, poor relations, doomed by the dreaded word “spinster” to secondary status even in their own families. So to encounter Alison Goodman’s 40-something unmarried twins—Lady Augusta Colebrook and her sister, Lady Julia—is a pleasant surprise. That the two women, each in her own distinctive way, resist the society that would relegate them to back rooms and lace caps just adds to the fun. And then there’s the disgraced Lord Evan Belford, escaped convict and highwayman, a charmer in his own right.

Alison Goodman was kind enough to answer my questions, so read on to find out more, then seek out The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies when it comes out on Tuesday. You won’t be disappointed. In fact, I can’t help thinking that if Heyer were writing today instead of in the last century, this is exactly the kind of story she would produce.

Your previous novels cover quite a range, from contemporary mystery to fantasy—including the Dark Days Club series, which might be considered Regency historical fantasy. How did this path lead you to The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies?

It has been quite a winding path through many genres to The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies. I suppose it is because I love to challenge myself when I write, and part of that is to write in different genres or to mash them together in ways that I hope will create surprise and delight. I would say the path to The Ill-Mannered Ladies started when I was twelve years old and my mother gave me my first Georgette Heyer historical novel. I immediately fell in love with historical fiction, and particularly books set in the Regency era. So, that love of all things Regency has been sitting in me for a long time. It first showed itself in my Dark Days Club series, which is like Pride and Prejudice meets Buffy, and is now in full throttle with The Ill-Mannered Ladies. The Ill-Mannered Ladies has no fantastical element like the Dark Days Club series, but it is as historically authentic and accurate as that earlier series and has as much action, romance and adventure. Plus it’s funny.

Lady Augusta Colebrook is quite a character. Tell us a bit about her.

Lady Augusta, or Gus as she is known to her twin sister Julia, is the main character and narrator of The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies. She is 42 years old, unmarried, smart, and a wee bit snarky. She is bored by the high society life she leads and is looking for purpose in her life beyond what society says a woman of her age and rank is allowed to do. And so, the Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies is born—Gus and her sister decide to use their privilege and invisibility as “old maids” to help other women in peril.

Her sister Julia is quieter and more biddable, yet she always seems to come through in a pinch. How would you describe her?

Julia is, I think, very much the “middle” child. She is the peacemaker between her fiery older twin, Gus, and their younger brother Lord Duffield or Duffy, as his family calls him. Julia seeks harmony and peace in her life, but that does not mean she won’t answer the call to adventure. She has a grounded serenity, and if Gus is ever in any trouble, Julia will come out swinging on her twin’s behalf. She has a lot of quiet gumption.

The twins, like many twins, have a special bond. Among other things, they often communicate without words. Why did you include that element?

I love the idea of a secret language between twins, which has been well documented in real twins, and it provides a lot of fun in the book. Gus and Julia communicate through their expressions: a flick of an eyebrow, a frown, a particular smile. Their secret language gives them an advantage in both social situations and on their adventures, and it really adds to their closeness as sisters in the novel.

Do introduce us to Lord Evan Belford. He is an absolute delight.

Ah, Lord Evan. What a honey! He’s had a bit of rough time of it: fought a duel twenty years earlier as a young man and apparently killed his man so was charged with murder, found guilty, and transported to Australia. Now he’s back in England for his own reasons and happens across Gus and Julia on one of their adventures. And when I say “happens across,” I mean he attempts to hold up their coach and Gus accidentally shoots him. However, he is exceptionally forgiving and so starts a wonderful partnership. His circumstances have forced him to live outside the privilege of his upbringing as the son of a marquess and so he is a rather appealing blend of gentleman and rogue.

Ah, Lord Evan. What a honey! He’s had a bit of rough time of it: fought a duel twenty years earlier as a young man and apparently killed his man so was charged with murder, found guilty, and transported to Australia. Now he’s back in England for his own reasons and happens across Gus and Julia on one of their adventures. And when I say “happens across,” I mean he attempts to hold up their coach and Gus accidentally shoots him. However, he is exceptionally forgiving and so starts a wonderful partnership. His circumstances have forced him to live outside the privilege of his upbringing as the son of a marquess and so he is a rather appealing blend of gentleman and rogue.In contrast, neither the twin’s brother, Lord Duffield, nor Evan’s, Lord Deele, could be considered at all delightful. Could you give us a brief description of them?

To be very brief, Duffy is Mr. Pompous! He is very much a man of his time—literally titled and very much entitled. Since their father’s death, he is the head of the Colebrook family and he believes it is his right to control his unmarried sisters’ lives. As you can imagine, that does not sit well with Gus at all. Lord Deele is Lord Evan’s younger brother but through circumstances has inherited the family title and wealth and is guardian to their younger sister. He, too, feels that as head of the family he can control the women within it, with disastrous consequences. Both of these characters are emblematic of the misogyny of the period but also have their own needs and goals that, unfortunately, get in Gus’s way. And woe betide anyone who gets in Lady Augusta Colebrook’s way!

Sketch for us, please, the cases that occupy Augusta and Julia in this book.

Without giving too much away, I have structured the novel into three cases (a nod to the wonderful Conan Doyle), each with its own story, but each also part of the overarching story. The first case takes Gus and Julia to a country house to save a wife in dire peril. The second takes them to Cheltenham and a nefarious situation in a brothel. And the third case takes them to a heinous asylum. I call the novel a serious romp, because it is fun and full adventure but also deals with some of the darker aspects of the Regency period.

This novel leaves Lady Augusta with an uncompleted mission. Are you working on the next book now, and can you give us any hints about what to expect?

I am, indeed, working on the next book and having as much fun with this one as I did while writing The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies. It’s another serious romp, this time with two longer cases rather than the three cases in the first book (yes, I’m having fun playing around with structure again!). Anything more, I think, would start to head into spoiler territory for the first book, so I will end by saying you can expect Gus and Julia to be just as resourceful, ill-mannered, and indomitable.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Alison Goodman is the award-winning author of eight novels—The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies, the Dark Days Club trilogy, the fantasy duology EON and EONA, Singing the Dogstar Blues, and A New Kind of Death. She lives in Melbourne, Australia. Find out more about her at https://www.alisongoodman.com.au/.

Portrait of Alison Goodman © Tania Jovanovic. Images of Regency ladies, gentleman, and highwayman public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

May 19, 2023

Overlooked Women Artists

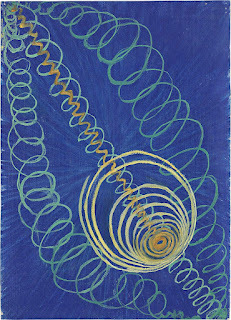

Although as a Russian specialist I had long known of the abstract art that became popular in the early twentieth century as part of the Bolshevik experiment, I hadn���t realized until I read this novel that the first abstract painters included a group of five Swedish women, three of whom���Hilma af Klint, Anna Cassel, and Cornelia Cederberg���were painters.

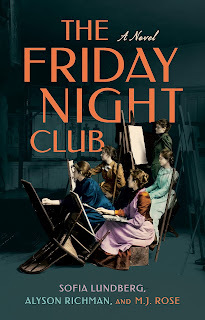

The Friday Night Club

���so called because the women met every Friday���counterposes the historical story and letters of the group with a contemporary timeline featuring Eben Elliott, an employee of the Guggenheim Museum charged with organizing an exhibit of Klint���s paintings.

Although as a Russian specialist I had long known of the abstract art that became popular in the early twentieth century as part of the Bolshevik experiment, I hadn���t realized until I read this novel that the first abstract painters included a group of five Swedish women, three of whom���Hilma af Klint, Anna Cassel, and Cornelia Cederberg���were painters.

The Friday Night Club

���so called because the women met every Friday���counterposes the historical story and letters of the group with a contemporary timeline featuring Eben Elliott, an employee of the Guggenheim Museum charged with organizing an exhibit of Klint���s paintings. Like the Friday Night Club itself, the novel is a collaboration among three authors���Sofia Lundberg, Alyson Richman, and M.J. Rose. I was eager to find out more about both their subject and their writing process, so read on to find out what they have to say.

Although I���ve long known about Wasily Kandinsky, it was news to me that Hilma af Klint preceded him and the other, better-known abstract artists. Indeed, like one of your characters, I at first confused Klint with Gustave Klimt. What made you all want to write a novel about Hilma and her collaborators?

Although I���ve long known about Wasily Kandinsky, it was news to me that Hilma af Klint preceded him and the other, better-known abstract artists. Indeed, like one of your characters, I at first confused Klint with Gustave Klimt. What made you all want to write a novel about Hilma and her collaborators?The inspiration for our novel, The Friday Night Club, first came about after a visit to the Hilma af Klint exhibit, Paintings for the Future, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2019.

At the museum, one of us noticed a small caption underneath a black-and-white photograph of Hilma that mentioned the artist had created a special group called the Friday Night Club, which consisted of her and four other women���Anna Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Mathilda Nilsson, and Sigrid Hedman���who gathered each week to provide one another artistic and spiritual sustenance and often performed s��ances in an attempt to channel spirits to guide them in their work. None of the other four were mentioned anywhere else in the exhibit, and, as we later learned, for all intents and purposes, they have since been relegated to being just a footnote in the now famous and celebrated Hilma���s personal history. Immediately, the question of who these four women were began to simmer, and the idea of a novel started to unfold around our desire to discover more about them.

The three of you collaborated on this novel. The end product is seamless, but what was the experience of collaboration like? What pluses and minuses come from working together?

It was actually seamless. While all three of us would divide and conquer our research���Sofia Lundberg in Sweden examining the journals and written materials of Hilma af Klint and Mathilda Nilsson in the Royal Swedish Archives, and Alyson Richman and M.J. Rose using materials written in English���we transcended the distance between us to work on a unified objective. We wanted to learn what drove these women to come together to seek higher knowledge and to pursue an artistic endeavor like The Paintings for the Temple, at a time when women had such few opportunities, outside of their traditional roles as wives, mothers, and homemakers. There really weren���t any minuses to the collaboration because we all had tremendous respect for each other as writers and we were always exchanging information we were uncovering through our research. Probably the only challenge was trying to make sure when we began working on each of our sections each morning that we retrieved the most current manuscript from Dropbox!

How did you decide to counterpose the late nineteenth-/early twentieth-century story of Hilma and her friends with a twenty-first-century (fictional) story about the (real) exhibit at the Guggenheim that inspired your work?

Being an art lover usually means being curious about the shows themselves and how they���re curated���so we wanted to build upon those parallels. The idea of showing the creating of the modern-day exhibit was part of the idea from the beginning. Once we began doing our early research about the Friday Night Club, or De Fem as they called themselves, we realized there were serious questions about how the group helped Hilma. And it seemed only natural that those questions should be explored in the present-day storyline.

Spiritualism plays an important part in this novel, represented by the characters Mathilda and Sigrid. Could you talk a bit about that element and what, if anything, it meant for you as authors?

At least one of us is heavily interested in spiritualism and we knew it had to play an essential part of the book once we learned through our research that every Friday night this group of creative women held s��ances in an effort to speak to the spirits and find artistic guidance and inspiration for their work.

Since Hilma, although underestimated, has still received more recognition than her fellow painters Anna Cassel and Cornelia Cederberg, could you tell us a bit about them?

Anna Cassel and Cornelia Cederberg���s early artistic training mirrored Hilma���s. They both received artistic training in Sl��jdskolan (now known as Konstfack), a premier art school in their teenage years, and this is actually where they met each other. After they graduated, only Anna and Hilma were accepted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, which was a very big milestone for a woman and aspiring artist in the nineteenth century. Anna leaned toward landscape painting, and from what we learned from our research and interviews with family members, she was perhaps more reserved than Hilma but still extremely determined to carve out a unique life for herself as an artist.

We learned Cornelia also made a significant contribution within the group as she was responsible for making the automatic drawings during the Friday night s��ances. She also allegedly created many of the shapes that occur in Hilma���s paintings.

And what of the fictional Blythe and Eben Elliott? Could you give us a brief description of them and how their story parallels or contrasts with the lives of ���The Five���?

Eben and Blythe are both art historians and lovers in the past who attended graduate school together at the Courtauld in London. She is very engaged in spiritualism, and Eben doesn���t believe in it���and that is part of what drove them apart. In some ways we think their relationship will mirror some of our readers who will come to this story as skeptics but in the end might wonder if there is another realm out there.

Where do the three of you go next? Will there be more collaborations?

We are each working on our own novels now but very much hope we can find another topic to collaborate on!

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Images: Photograph of Hilma af Klint (1895), Late Summer (1903) and Primordial Chaos, no. 16 (1906���7) by Hilma af Klint���all public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sofia Lundberg is an internationally bestselling author, journalist, and former magazine editor. Lundberg is the shining new star of Scandinavian fiction, translated into nearly forty languages. She lives in Stockholm with her son.

Alyson Richman is a USA Today and #1 international bestselling author. She is an accomplished painter, and her novels combine her deep loves of art, historical research, and travel. She lives on Long Island with her husband and two children.

M.J. Rose is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author. She grew up in New York City exploring the labyrinthine galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the dark tunnels and lush gardens of Central Park.

May 12, 2023

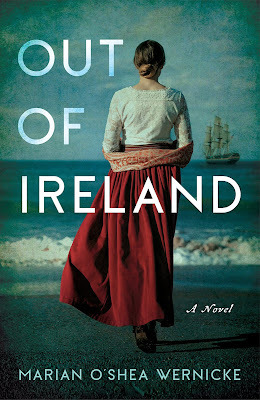

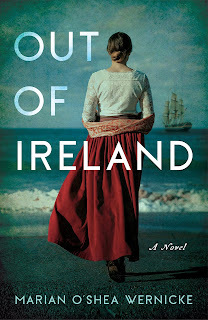

Out of Ireland

The United States, as people say, is a nation of immigrants. There have been waves of immigration from various parts of the world, as well as a shameful history of involuntary immigration, but—although some people like to deny this part—what most of us have in common is that our ancestors came from somewhere else.

The United States, as people say, is a nation of immigrants. There have been waves of immigration from various parts of the world, as well as a shameful history of involuntary immigration, but—although some people like to deny this part—what most of us have in common is that our ancestors came from somewhere else.People don’t pick up and leave home unless driven by a need more powerful than the natural love of all things familiar. Poverty, hatred, fear, desperation, the yearning for a better life—these are natural sources of tension and drama. As Marion O’Shea Wernicke discusses in our New Books Network interview, she found inspiration in her grandmother’s story. Read on—and listen—to find out more.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Most people have heard of the Irish famine in 1848 and of the resistance movement against British sovereignty that consumed much of the twentieth century. In this attempt to understand her great-grandmother’s life, Marian O’Shea Wernicke examines the years between the famine and the Easter Rebellion of 1916. In the process, she creates a compelling tale of a young Irish girl, Mary Eileen O’Donovan, whose impoverished family forces her to marry a neighboring farmer in his forties when Eileen, as she’s known, has barely passed her sixteenth birthday.

Most people have heard of the Irish famine in 1848 and of the resistance movement against British sovereignty that consumed much of the twentieth century. In this attempt to understand her great-grandmother’s life, Marian O’Shea Wernicke examines the years between the famine and the Easter Rebellion of 1916. In the process, she creates a compelling tale of a young Irish girl, Mary Eileen O’Donovan, whose impoverished family forces her to marry a neighboring farmer in his forties when Eileen, as she’s known, has barely passed her sixteenth birthday.In material terms, it’s a good match, but it is not what Eileen wants from life. A bookish girl, she has ambitions of studying to become a teacher, but pressure from her family puts paid to those plans. Eileen grudgingly agrees to wed John Sullivan and does her best to make him a good wife. When she becomes pregnant, the couple’s newborn son unites them for a while, but John’s morose nature and frequent drunkenness make him a difficult man to love, especially for an idealistic girl.

When the crops fail and Eileen’s younger brother falls foul of the Fenians, Eileen and John decide their only choice is to emigrate. But leaving Ireland turns out to carry a high price as well …

May 5, 2023

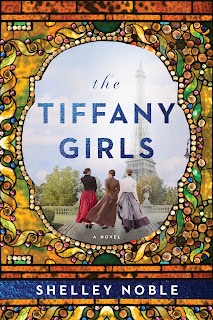

Interview with Shelley Noble

It’s 1899, and Louis Comfort Tiffany is preparing a series of dramatic artworks made of colored glass to show at the Paris World Exposition the next spring. His workshop is unusual by the standards of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: not only does he hire women artists, but he pays them at rates similar to those of his male employees. Shelley Noble’s new novel,

The Tiffany Girls

, due out on Tuesday, follows the intertwined stories of three of these women: Emilie Pascal, Grace Griffith, and the real-life Clara Driscoll—whose obituary was republished by the New York Times earlier this year. Shelley was kind enough to answer my questions, so read on to find out more.

It’s 1899, and Louis Comfort Tiffany is preparing a series of dramatic artworks made of colored glass to show at the Paris World Exposition the next spring. His workshop is unusual by the standards of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: not only does he hire women artists, but he pays them at rates similar to those of his male employees. Shelley Noble’s new novel,

The Tiffany Girls

, due out on Tuesday, follows the intertwined stories of three of these women: Emilie Pascal, Grace Griffith, and the real-life Clara Driscoll—whose obituary was republished by the New York Times earlier this year. Shelley was kind enough to answer my questions, so read on to find out more.I noticed on your website that you have published, in addition to a lot of contemporary novels, a historical mystery series set in the early twentieth century. Did this lead into The Tiffany Girls, and if not, what did spark your interest in Tiffany and his female staff?

My latest Gilded Age Manhattan series literally led me to the Tiffany Girls. I was researching turn-of-the-century (19th–20th) psychology for A Secret Never Told, which dealt with a group of particularly murderous psychoanalysts, when an article about the discovery of Clara Wolcott Driscoll’s family letters appeared in the feed. Being easily enticed into unexpected rabbit holes, I opened the link and read about the almost simultaneous discovery of two batches of her personal letters (1906) that shed light on this little-known department in the Louis C. Tiffany Glass Company and led to an exhibit and book titled A New Light on Tiffany. I was captivated. The Tiffany Girls became my next novel.

Emilie Pascal is the first of your women artists that we meet and the most troubled. How would you characterize her personality and her goals as an artist?

Emilie is passionate and driven—passionate about art, about creativity, about life. But she has seen how passion can destroy, and she is determined to succeed in her art no matter what she must sacrifice.

And what takes Emilie away from Paris?

Her father, a respected Parisian portrait painter, is abusive and is finally outed as a notorious art forger. He is sought by the police and Emilie knows she must reinvent herself far from the scandal if she is to realize her future as an artist. She has seen an exhibit of Tiffany’s glass works, has heard of his division of anonymous women artists, and determines to become one of them.

Grace Griffith helps Emilie out from the moment of their first meeting, but the two don’t entirely share the same goals. What does Grace want from life, and what stands in her way?

Grace is down-to-earth with “the new woman” notions. She is fair and compassionate, and is one of the best drafters in the women’s division, but she aspires to be a political cartoonist and change society through her drawings. Of course, she can do this only under a pseudonym, because journalism is still a male domain. But one day …

Each of these young women has a male interested in her—indeed, Emilie has more than one. But both are reluctant to encourage romantic relationships. Why, and what can you tell us about Emilie’s Leland (and Amon) and Grace’s Charlie?

Women of the time were just encountering widening work opportunities. “The new women” of the early twentieth century were interested in getting an education and pursuing a career, not only as teachers and nurses but as shop “girls,” typewriter “girls,” telephone “girls,” and so on. No married women need apply. And when a working girl became engaged or wed, she was immediately let go. Many of the girls at Tiffany’s were anxious to be married, but those who wanted careers had to make the decision to stay single. Grace and Emilie are both young, pretty, and intelligent, and they naturally attract young men. Charlie is older, a seasoned journalist, a bit world weary, but he sees Grace’s potential and nurtures her career. The glassblower Amon calls to Emilie’s passion, but she is afraid to allow him to get too close. Leland is cultured, rich, an art dealer who is charming and comfortable with an artistic eye. Of course, both men appeal to Emilie’s warring nature. But neither Grace nor Emilie is willing to sacrifice her goals by ceding them to matrimony.

Clara Driscoll is the third of the Tiffany Girls to merit inclusion in your book description. She’s in a very different place in her life from Emilie, Grace, and their cohort, though. What’s most important for us to know about her?

Clara was an actual person, the manager of the women’s division, but she was also an artist, responsible for some of Tiffany’s most iconic pieces. She did this, as did all the women, mostly without receiving personal recognition for her work. But from everything we know, she never resented Tiffany. It took several workers to complete a lamp or window or decorative item, a collaborative effort. But Tiffany was the driving genius of the work, and I like to think that his artists recognized that.

Last but not least, we have Louis Comfort Tiffany, who is simultaneously the center of the women’s working life and peripheral to their personal stories. Was he fun to write? What should we take away about him and his art?

Tiffany himself was harder to write. He was definitely the center of his artists’ world; he is also a bit of an enigma. We have bits and pieces about him: he had to fight his father (the jeweler) constantly in order to be free to follow his own art. He was a philanthropist, loved the new automobiles and fast speed, was evidently a loving husband and father, and stuttered when he became upset. He did leave a few writings about art, and these helped me with his work and attitude to his art and artists. What I did imagine was that, most of all, besides being an artist and creator of brilliant works, he was also human.

And what of you? Are you already working on something else?

I’m currently working on a new historical novel about three women who in the early 1900s must overcome scandal, the male patriarchy of New York society, the overbearing morality of the times, and their own preconceptions about each other to establish the first women's only club in Manhattan.

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

Shelley Noble is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of sixteen novels of historical fiction, historical mystery, and contemporary women’s fiction—most recently, The Tiffany Girls. Find out more about her at https://www.shelleynoble.com.

Images: poster for the 1889 Exposition universelle de Paris, photographs of Clara Driscoll in 1901 and of her famed Dragonfly lamp all public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Photograph of Shelley Noble from the author’s website.

April 28, 2023

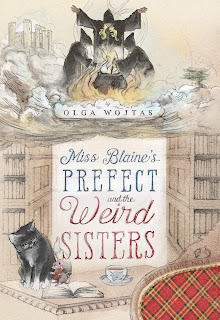

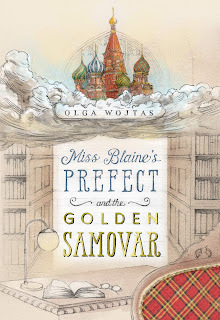

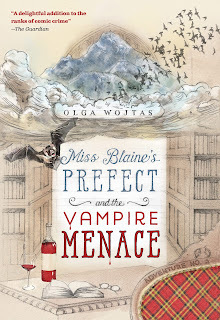

Interview with Olga Wojtas

A time-traveling Scottish librarian with a chip on her shoulder because the school she proudly attended (the Marcia Blaine School for Girls) was panned in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and a feminist philosophy that she does her best to inflict on a past where it is very much unwelcome—who could resist such a heroine? Certainly not me. Olga Wojtas’s tongue-in-cheek approach to history—a trait she shares with her main character, Shona McMonagle—makes a nice change from the more serious historical fiction that so often crosses my path. I have yet to read the second novel,

Miss Blaine’s Prefect and the Vampire Menace

, but I have read the first and the third.

A time-traveling Scottish librarian with a chip on her shoulder because the school she proudly attended (the Marcia Blaine School for Girls) was panned in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and a feminist philosophy that she does her best to inflict on a past where it is very much unwelcome—who could resist such a heroine? Certainly not me. Olga Wojtas’s tongue-in-cheek approach to history—a trait she shares with her main character, Shona McMonagle—makes a nice change from the more serious historical fiction that so often crosses my path. I have yet to read the second novel,

Miss Blaine’s Prefect and the Vampire Menace

, but I have read the first and the third.Miss Blaine’s Prefect and the Golden Samovar (book 1) takes place in the Russian Empire on a date that is never specified but can be deduced from clues in the text. Shona knows she has a mission, but not what it is, and much of the action involves her swanning about St. Petersburg high society trying to figure it out before her assigned week ends and she is summoned back to contemporary Edinburgh in disgrace. It’s all very lighthearted, especially the contrast between Shona’s view of her own near-omnipotence and the reality that lies right under her nose.

Book 3, Miss Blaine’s Prefect and the Weird Sisters, has just come out. For this one, Shona remains in Scotland but travels far into the past, where she encounters Macbeth. Yes, that Macbeth. Also Lady Macbeth, King Duncan, the three witches—I could go on, but you get the idea. There’s even a cat with three names, in an unspoken but, I assume, not unintended nod to T.S. Eliot. To celebrate her latest publication, Olga Wojtas agreed to answer my written questions, so read on to find out more about Shona and her various missions.

This is the third novel featuring your time-traveling librarian, Shona McMonagle. What was your inspiration for this series?

I’m a journalist and a news junkie and was getting stressed out by current events, so I decided to write a comic romp where the reader could relax knowing that everything would work out and there was no jeopardy. Normally there’s character development in novels, with the protagonist going on a literal or metaphorical journey. I don’t have anything like that—my heroine is exactly the same at the end of her missions as at the beginning and has learned nothing. A great influence was P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster books, where Bertie constantly gets into terrible scrapes and has to be bailed out by Jeeves.

Shona goes first to tsarist Russia and then to fin-de-siècle France. How do you pick your settings?

I studied Russian and developed a love of its literature, especially Tolstoy. That was the inspiration for the first novel because I could steal some scenes: the grand ball; the duel in the forest; the drama involving a train. The second novel was inspired by the time I lived in Grenoble in France, which is in a valley surrounded by mountains. It had a vampire theme, and I imagined a French village surrounded by mountains so high that the sun never reached it. There’s a vampiric link with Aberdeenshire in Scotland, which led me to introduce a real person, the Scottish-American opera star Mary Garden. She became Debussy’s muse in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century, which suggested the time period.

Before we get to the current novel, tell us a bit about the Marcia Blaine School for Girls and its proprietor. And how does The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie get in there?

Before we get to the current novel, tell us a bit about the Marcia Blaine School for Girls and its proprietor. And how does The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie get in there?The Marcia Blaine School for Girls is where Miss Brodie teaches in Muriel Spark’s novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. It was based on James Gillespie’s High School in Edinburgh, Scotland, the school Dame Muriel attended and where I went as well. I’ve fictionalized the school even further, giving it the motto Cremor cremoris, the crème de la crème. My heroine, Shona, is appalled by Dame Muriel’s novel, which she believes has brought the school into disrepute. A librarian in Edinburgh’s Morningside Library, she spends her time preventing the book falling into the hands of readers. One day the school’s founder, Miss Blaine herself (who Shona calculates must be over two hundred years old but appears to be a woman in her prime, like Miss Brodie) turns up in the library, and Shona finds herself sent on a time-traveling mission. The aim of every Blainer is to make the world a better place, and time traveling means they can make previous worlds better as well.

From the title of this novel, it’s pretty clear that Shona will meet Macbeth and the three witches. What is her mission, to the extent that she knows herself?

It has to be said that Shona rarely, if ever, has a proper grasp of what her mission is. She occasionally muses that it would be easier if there were written instructions, but this usually results in a pain in her big toe as though someone has trodden on it very hard, so she tries not to complain too audibly. In this instance, she knows that Shakespeare’s Macbeth is historically inaccurate but finds events panning out in such a way as to suggest they’re following the play. She’s afraid that this may change the whole course of history, so she decides that her mission must be to prevent King Duncan being murdered when he comes to stay with the Macbeths.

Your three witches are, shall we say, a little more approachable than their Shakespearean counterparts. Describe for us, please, Ina, Mina, and Mo.

They’re sisters, Ina being the eldest and Mo the youngest. Ina and Mina always talk in verse, catalectic trochaic tetrameter to be precise. (Think of the Shakespeare version: “When shall we three meet again? / In thunder, lightning, or in rain?”) Unfortunately, Mo has never mastered poetry, and her two big sisters constantly mock her for this failing. They also tell her she’s a rubbish witch, but when there’s a genuine crisis, it turns out that family is the most important thing.

Another character we meet early on is a black cat known alternately as Hemlock, Spot, and Frank. Please say a bit about him and his multiple identities.

He’s a typical cat in that he’s conned two households into thinking that he belongs to them, so that he gets fed twice. He mooches between the witches’ cavern, where Mo has named him Hemlock, and Glamis Castle, where Lady Macbeth has named him Spot because of the white spot on his chest. However, he explains to Shona that he’s not actually a cat but an inadvertent time traveler called Frank, who can’t stand William Shakespeare.

Shona does, in due course, meet Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. What should we know about them in your rendering of the tale?

First of all, that there’s no such person as Lady Macbeth. Her real name was Gruoch, which is the name I use. Second, she and her husband speak Scottish Gaelic—his name literally means “son of life.” They’re a devoted couple, although she’s very definitely the one in charge. He does what he’s told, or at least he tries to. She usually has to sort things out.

I assume that Shona will embark on additional missions. Do you know where Miss Blaine will send her next?

I do.

Ah, were you looking for a bit more? In that case, I can exclusively reveal that the title of the next episode may well include the word “gondola.”

Thank you so much for answering my questions!

A great pleasure—thank you!

Olga Wojtas is the author of the Miss Blaine’s Prefect series and of cosy crime novellas. She lives in Edinburgh, Scotland.

April 21, 2023

Long Shadows

As anyone who read my written interview with C.S. Harris to celebrate last year’s release of When Blood Lies, the previous installment in this gritty historical mystery series set during the second half of the Napoleonic Wars, must realize, I am a hard-core fan of the Sebastian St. Cyr novels.

As anyone who read my written interview with C.S. Harris to celebrate last year’s release of When Blood Lies, the previous installment in this gritty historical mystery series set during the second half of the Napoleonic Wars, must realize, I am a hard-core fan of the Sebastian St. Cyr novels.A large part of my enjoyment comes from following the maturation of Sebastian himself, as well as his relationships with various family members and love interests. But there are many other recurring characters—Hero Jarvis and her father; the actress Kat Boleyn; the Earl of Hendon, forever befuddled and somewhat appalled by the unconventional behavior of his heir; the Dowager Duchess of Claiborne; the pain-riddled surgeon Paul Gibson and, most recently, his live-in lover and fellow physician Alexi Sauvage—whose development I eagerly follow. So when I learned that another book in the series was in the works, I actively pursued the opportunity to feature the author on my New Books Network channel.

And the result was a wonderful conversation about how a young woman who set out to be an archaeologist wound up writing historical mysteries set in the 1810s. Read on—and most of all, listen—to find out more, including a hint as to what to expect from the next installment, What Cannot Be Said.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Fans of Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin, know that the individual tales that form his saga combine complex, fast-paced, often political mysteries with a series of revelations about his family’s history that it would be churlish to reveal. All this takes place against the background of the Napoleonic Wars, mostly in Regency-era London with its vast social gap between the aristocratic rich and the starving, crime-ridden poor.

The eighteenth of Sebastian’s adventures, Who Cries for the Lost, begins a few days before the Battle of Waterloo, a cataclysmic event—unknown to the characters, obviously—that will end Napoleon’s military ambitions once and for all. A mutilated body is fished out of the Thames River and taken to Paul Gibson—a friend of Sebastian’s who served as a surgeon during the Peninsular War—for an autopsy. When Paul’s lover identifies the victim as her former husband and an aristocrat, the creaky wheels of the London policing system grind into gear. The Thames River Police may provide as much hope for justice as the costermongers and wherry boatmen of the city deserve, but a nobleman falls under the jurisdiction of Bow Street.

As the number of corpses rises and pressure from the Prince Regent in Carlton House intensifies, Sebastian must race to solve a series of baffling, seemingly disconnected murders before the outcry demanding a solution leads to the arrest and execution of his friends. Meanwhile, the country anxiously awaits reports from the Duke of Wellington’s army on the Continent, further stoking the tension, even as Sebastian confronts the reality of his nation’s past misdeeds during the war and wonders whether those atrocities explain the crimes being committed in the present.

April 14, 2023

Bookshelf, Spring 2023

What follows is just a few of the many books that have recently been or are still on my bookshelf for the spring. I’d also like to remind you of Erica Neubauer’s Intrigue in Istanbul, which I included in my winter list although it came out just last week. Other Spring 2023 highlights include Molly Greeley’s Marvelous, Sherry Thomas’s Tempest at Sea, Kristen Loesch’s The Last Russian Doll, and C.S. Harris’s Who Cries for the Lost—all covered (or due soon to be covered) elsewhere on this blog.

What follows is just a few of the many books that have recently been or are still on my bookshelf for the spring. I’d also like to remind you of Erica Neubauer’s Intrigue in Istanbul, which I included in my winter list although it came out just last week. Other Spring 2023 highlights include Molly Greeley’s Marvelous, Sherry Thomas’s Tempest at Sea, Kristen Loesch’s The Last Russian Doll, and C.S. Harris’s Who Cries for the Lost—all covered (or due soon to be covered) elsewhere on this blog.And now, on to the May and June novels I have been enjoying. All forthcoming books this time around, although I've made my way through a fair number of older novels as well in the last few months.

Amy Barry,

Marrying Off Morgan McBride

Amy Barry,

Marrying Off Morgan McBride

(Berkley, 2023)

This classic historical romance matches Epiphany Hopgood, better known as Pip, with Morgan McBride—a free-ranging cowhand who has been stuck for years on a farm in Montana looking after his younger siblings. Pip, a fabulous cook whose outward appearance fails to attract the men of Joshua, Nebraska, answers an ad for a mail-order bride, not realizing that the person who placed the ad was not the intended groom but his young sister, Junebug, desperate for help in the kitchen.

When the truth comes out, Pip insists on staying, because the alternative is to return to a place where she’s never felt wanted. And sparks fly, both angry and passionate, as a result. As with all romance novels, we have a pretty good idea of where things will end up, but the road to get there is long and winding, and the antics of the irrepressible Junebug will keep you laughing along the way. You can find out more from my blog Q&A with the author on June 2, just after the book’s release.

Katharine Beutner, Killingly (Soho Press, 2023)

As a Mount Holyoke alumna, I couldn’t resist this psychological suspense novel based on the true-life disappearance of Bertha Mellish, a student, from the campus in 1897. As the author notes in the book, the result is deeply fictionalized—it would have to be, given that the real case was never solved and the little hard evidence that remains of what happened is tantalizing but not conclusive—but that doesn’t make the story any less compelling. On the contrary, Beutner fleshes out the bare bones of the incident, delving into Bertha’s past in Killingly, Connecticut, as well as her relationship with Agnes Sullivan, a would-be doctor from a poor Boston family who has been forced to conceal her Catholic upbringing to gain admission to the college. Through the overlapping stories of Agnes, the missing girl’s sister Florence, Dr. Henry Hammond, and the inspector whom Hammond hires to find Bertha, Katharine Beutner keeps us on the edge of our seats as she unravels their tangle of secrets and lies. I’ll be talking with her on the New Books Network in time for the novel’s release in early June.

Sofia Lundberg, Alyson Richman, and M.J. Rose,

The Friday Night Club (Berkley, 2023)

This co-written novel explores the lives of a little-known group of Swedish abstract painters. Three of the five—Hilma af Klint, Anna Cassel, and Cornelia Cederberg—were artists who drew their inspiration from the seances conducted by the other two during their regular Friday meetings. For reasons explained in the novel, the women’s artworks received so little recognition in their time that Klint secreted her paintings, stipulating that they could be viewed only twenty years after her death.

This story is interlaced with a contemporary timeline featuring Eben Elliott, an employee of the Guggenheim Museum in New York charged with organizing an exhibit of Klint’s paintings—a choice that brings him face to face with his own past. Even more impressive than the interweaving of these disparate story threads is the collaboration of the novel’s three authors. Like their nineteenth-century counterparts, they have created a single, seamless work of art. They will be answering my written questions on the blog the Friday after their book’s release on May 16.

Shelly Noble,

The Tiffany Girls

Shelly Noble,

The Tiffany Girls

(William Morrow, 2023)

We tend to think of Tiffany’s as a jewelry store, but its founder, Louis Comfort Tiffany, was perhaps best known for his dramatic artworks composed of colored glass. He was also unusual in that he both hired women artists and paid them the same rates as men. This novel juxtaposes the stories of three “Tiffany Girls,” as they were called at the time: Emilie Pascal, who flees France to escape possible criminal charges accrued by her abusive father, an art forger; Grace Griffith, who enjoys the security of her work at Tiffany’s but yearns to use her talents in producing political cartoons for the local papers; and Clara Driscoll, the real-life director of the women’s division and an artist in her own right. The result is a rich portrayal of working-class life in New York around the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Shelly Noble will be answering my questions here on the blog in just a few weeks, after her novel comes out on May 9.

Ginny Kubitz Moyer, The Seeing Garden

(She Writes Press, 2023)

Nineteen-year-old Catherine Ogden appears to have everything: youth, wealth, birth, breeding, and beauty. No one in New York high society is surprised when she attracts the attention of William Brandt, an up-and-coming business tycoon from California. It’s 1910, and the job of women like Catherine is to marry well and make their families proud.

After a visit to the Brandt estate near San Francisco, Catherine accepts William’s proposal of marriage. But is it William himself who appeals to her, or his house and gardens? As the wedding day draws closer, Catherine must decide whether to fulfill her own expectations of marriage or those of her family.

The author’s descriptions of the landscape and its effect on Catherine are exquisite. I look forward to talking with her about both her setting and her richly realized characters on the New Books Network in July. The novel, though, will come out in May.

Marian O’Shea Wernicke,

Out of Ireland

Marian O’Shea Wernicke,

Out of Ireland

(She Writes Press, 2023)

This fictional look at the US immigrant experience in the late nineteenth century follows the life of a young Irish girl, Mary Eileen O’Donovan, whose impoverished family forces her into marriage when Eileen, as she’s known, has barely passed her sixteenth birthday. Giving up her ambitions to become a teacher, Eileen tries to be a good wife to John Sullivan, her much older husband. When the crops fail and her younger brother falls foul of the Fenians, she and John decide their only choice is to emigrate. After considerable effort, they reach the United States, only to discover that their troubles are just beginning. Find out more by listening to my New Books Network with the author, due in mid-May.