Jason Lewis's Blog, page 9

July 2, 2012

Raising the Dream – The Expedition Book excerpt 3

One year later… Ardleigh reservoir, Suffolk

The morning air was clear. A stiff northeasterly blew unchallenged across the Broads from the North Sea, slicing to the bone through our meagre wool jerseys. We’d been at the reservoir since dawn, waiting for the boat builders to arrive with the recently completed hull. Today was a big day. By the end of it, we would know two things: whether the strange-looking contraption floated, and whether a customized propeller could move it though the water.

Chris had called the night before to say they’d run into a few technical difficulties. The trailer lights had died in the middle of Bridport, about the time they’d worked out that eight pounds between them wasn’t near enough to buy fuel for the 275-mile journey to Suffolk. Towing a three-tonne trailer plus the hull, Hugo’s long wheelbase Land Rover made eight miles to the gallon at best.

“Lucky we ran out of petrol opposite the Toll House pub,” chuckled Chris, sounding happy at the turn of events. “The landlord’s given us a lock-in. And bitter’s only eighty-eight pence! Oh yeah, and we’re calling round to see if anyone’s got an AA card––”

The line went dead. Whether cheap booze or the Automobile Association amounted to a solution would remain a mystery until they showed up – if indeed they ever did.

It had been a busy year since meeting up in Paris. In the spring, Steve had left his job to begin planning the expedition full-time. Four months later, I followed suit by dissolving Ballistic Cleaning Services Inc., bringing to an end nearly a decade of pedigree cleaning care. To the great relief of our families, the idea to kayak from Scotland to Canada had been shelved early on. A call to the Maritime Museum in Exeter to enquire whether they knew of an ocean-going row boat for sale had produced a far more sensible way of crossing the big wet bits.

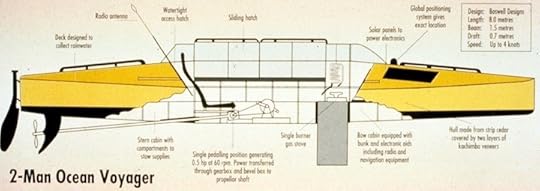

After listening to Steve’s ambitious circumnavigation plans, the curator, a naval architect by trade, offered to design a human-powered vessel from scratch. Calling on his extensive knowledge of the twenty or so rowing boats that had crossed the Atlantic since 1896, some of which were displayed in the museum, Alan Boswell drew up the blueprints for a twenty-six-foot craft, powered by propeller, with enough storage space to sustain two people with food and provisions for up to 150 days without resupply.

“Another advantage of a pedal-powered vessel,” Alan wrote in a follow-up letter, “is that since you will be cycling across continents, you will be fantastically fit for pedalling, but not for rowing, when you get to the ocean sections.”

Connecting with Alan had been the first in a series of lucky breaks, elevating the idea from drunken talk to at least drawing board status. David Goddard, the museum’s founder and director, generously provided a storage shed for the boat’s construction. The icing on the cake was reconnecting with my old childhood pal, Hugo Burnham, recently graduated from the prestigious wooden boatbuilding college at Lowestoft. Along with his friend Chris Tipper, also a newly qualified shipwright, we now had a relatively inexpensive way of building what commercial boatyards had quoted £26,000.

Further bolstered by the donation of otherwise pricey hardwood from the Ecological Trading Company, one of the few businesses in the country importing timber harvested only from sustainably managed sources, construction commenced. Four months later, a cold-molded hull, comprising strip cedar planks sealed with epoxy resin and overlain with hardwood veneers, emerged from the workshop.

It was time to stick it in the water.

The Times and The Daily Telegraph had agreed to turn up and run picture stories, announcing our plans to the wider world for the first time. Publicity was all-important to secure the sponsorship needed to embark on the expedition proper.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Chris (L) and Hugo (R) working on Moksha’s superstructure

June 28, 2012

The Big Idea – The Expedition Book excerpt 2

“It’s incredible isn’t it,” Steve exclaimed, “how no one’s thought of it yet?” As he’d already pointed out, the Earth had been circumnavigated using everything from sailboats, to airplanes, to hot air balloons. Yet the purest, most ecologically sound method of all and doable for centuries, without using fossil fuels, was still up for grabs. “It may even be an original first!” he continued excitedly.

My old college pal Steve Smith and I were slumped on the kitchen floor of his flat in Paris, drinking Kronenbourg 1664 at two in the morning. A map of the world lay between us, paddled by the slowly revolving shadow of an ornate ceiling fan that gave the apartment an air of French colonial panache.

“So, you reckon all the other big firsts in exploration and adventure have been done?” I asked.

Steve had clearly done his homework, proceeding to reel off some of the more notable feats of the last century: Amundsen beating Scott to the South Pole in 1911; Hillary and Norgay summiting Everest in 1953; Armstrong setting foot on the moon in 1969. By 1992, however, it was slim pickings with the exception of the deep oceans and outer space. Nearly every square inch of the planet’s surface had been trampled upon, sailed across, flown, or driven over. Explorers and adventurers were fast becoming a rare breed, increasingly reliant upon inventive wordage to pass off a gimmick, or variation on a well-worn theme, as something genuinely different.

“It won’t be long before the media,” he finished off dryly, “run a story about the first blind-folded transsexual to snowboard down Everest in a thong.”

I smiled. “That’s been done already hasn’t it?”

“Not on a dustbin lid.”

Earlier that afternoon I’d flown from London, taking up Steve’s invitation for “a bit of piss up – you know, just like old times.” I should have smelt a rat right there. We’d barely seen each other since our final year at university. Why the grand reunion now all of a sudden?

The reason soon became clear after we rendezvoused at Charles de Gaulle Airport, and began lurching our way into the centre of the city on the metro. Clutching the steel bar above his head and raising his voice over the clattering wheels, Steve pitched the most ingenious, hair-brained, inspirational, irresponsible, guaranteed-to-give-your-mother-a-cardiac-arrest idea I had ever heard:

A human-powered circumnavigation of the globe…

Those few words hung suspended in the carriage for a moment, like a spell, putting goose bumps on my skin. I mean… to travel as far as you can go over land and sea, to the very ends of the Earth itself, under your own steam. No motors or sails. Just the power of the human body to get you there and back again. It had to be the ultimate human challenge.

As Steve continued outlining his plan, my head filled with wildly romantic images: riding bicycles across the barren steppes of Central Asia, trekking through the frozen wastes of the Himalayas, staring into the flames of a roaring campfire after a hard day hacking through the Amazonian rainforest. What about the oceans? I wondered. Rowing? Swimming? Paddling a Boogie Board? And why was Steve asking me of all people to join him?

I had absolutely no experience as a so-called “adventurer.” I’d travelled before, but never far off the beaten track: Kenya for three months after school, Cyprus during college, and the US for a spell immediately afterwards. From the age of sixteen, I devoted myself to singing in a grunge band that played in all the usual London toilets: the Falcon in Camden, the Half Moon in Putney, the Bull and Gate in Kentish Town. It was fun in the early days when we hadn’t taken ourselves too seriously. The first outfit, Dougal Goes to Norway, was a cover band distinguishable from the rest only by our Viking helmets and kilts – nothing on underneath. Later, we tried to make a proper go of it, releasing a vinyl EP. But with the entire band of five, plus two dogs and three cats, crammed in a two bedroom semi-detached house in Staines—The Shitehouse, as it was known—it had all become a bit of a grind.

I paid for my music habit with “Ballistic Cleaning Services Inc.,” a window cleaning business under contract with various restaurants and hotels in the West London area. When not leaning off ladders buffing windows, my partner Graham and I could typically be found wheezing up and down the A332 between Egham and Bracknell in the pride of the fleet, an X-reg Morris Marina van costing fifty quid from a scrap yard off the Old Kent Road. Spray-painted with the slogan “Get Realistic. Go Ballistic!” the company jalopy had no registration, road tax certificate, or insurance. But it was mechanically sound. And apart from one occasion when a rear wheel fell off and overtook us along Ascot High Street, it had never let us down.

Surely, however, these weren’t suitable qualifications for an undertaking such as this?

I shot Steve a sidelong look. “You sure you want me as your expedition partner?”

He nodded.

“And it’ll take around three years to complete you say?”

“If we can find sponsorship.”

Taking a swig, I surveyed my old friend. Like many of our deskbound graduate peers, he looked anaemic, badly in need of some sun. But while others were already turning paunches, Steve remained athletic and trim, not an extra ounce of fat on his body. And he still had the same steady cobalt gaze.

The first time we met I was supine on a stranger’s bed in one of the halls of residence, my arm around a girl, the other around a bottle of vodka. As the party wore on, I became dimly aware of the bed’s owner – Steve as it turned out – glaring at me from across the room.

Steve took an instant dislike to “that unruly farm boy” who’d soaked his bed in vodka. In time, however, attending the same biology and geography lectures, we became good friends. After a weekend poaching trout on Dartmoor when we should have been sitting through stultifying lectures on tor formation at a local field studies centre, we began taking off on spontaneous rambles around London. A three-day hike on the Chilterns in south Oxfordshire was one. Disembarking the train at Princes Risborough, we discovered neither of us had a sleeping bag, or a tent. It was the middle of January. Night-time temperatures were well below freezing. That first night we slept on the floor of a pub, sneaking back through the lavatory window we’d left ajar before being turfed out. The second night we lucked out, chancing upon a hay barn. Otherwise, we would have likely frozen to death.

Such was our early friendship, defined by episodes of kamikaze impetuousness swaggering along the knife-edge of fate – the sharper the edge the better.

Further fuelled by beer, brainlessness and a shared bent for challenging authority, we developed a penchant for egging each other on in a series of puerile college pranks, culminating in the erection of a fifteen-foot-high penis made from cardboard, party balloons and a pink bed sheet on an ornate spire at the entrance to campus. The pathetically limp protest directed at a visiting politician, made even more so by a light drizzle, was the best we could deliver as an anti-establishment statement at the time.

Then we went our separate ways: Steve into a career as an environmental scientist, myself into the giddy world of crooning in dive bars and cleaning windows.

“So where did you get the idea?” I asked.

Steve pursed his lips and shook his head at the memory. “I was working for the OECD at the time.[1] At first I thought I’d be making a difference, writing reports for politicians to integrate environmental sustainability into their economic development policies.”

Like a growing number in his field, Steve was alarmed by the ballooning number of human beings on the planet, ten billion by 2050, all aspiring to the same level of prosperity as the average Westerner – as seen on TV. Conservative estimates for meeting consumption demands without further depleting resources or biodiversity from 1994 levels was set at eight additional Earths.

“But the reports fell on deaf ears,” he went on. “An inhabitable planet for future generations is a lovely idea, the economists said, but we simply can’t afford it.”

Instead of falling into line with offers of promotion and salary increases, Steve took a stand.

“I felt like grabbing those short-term-thinking fuckwits by their starched collars and saying, ‘haven’t you seen the data on climate trends and species extinctions? We can’t afford not to do something. We’ll be next!’”

Small wonder he was duly assigned to a very different field of study: assessing the environmental impact of creosote on motorway fence posts. Their plan worked. Steve became disillusioned, staring out of the window, his mind wandering…

“That’s when I thought: what if I were free to do anything, anything at all, what would I be doing with my life right now?

He knew it had to be something to do with travel, and adventure, and on a big scale.

“And what bigger than around the world?”

The mode of propulsion was a stumbling block. It needed to be inexpensive, with minimal harm to the environment.

“Engines and I don’t get along. And if animals were involved, they’d all be dead within the month.”

Then it came to him. The Eureka Moment. The cheapest, least technical, lowest impact power of all. Human power.

“So, what do you think Jase? You up for it?”

I looked out through the kitchen window, past the wrought-iron balcony into the Paris night. The blank spaces on the map with no roads or towns marked I found utterly captivating. And a sabbatical from music might revitalize the songwriting juices. Moreover, if we left sooner rather than later, I might avoid a thorny court case for crashing the Ballistic cleaning van into a Rolls Royce off the Fulham Road and having to do a runner.

But there was something else.

I cast my mind back to when I was sixteen, sitting in the warm, dusty office of the school’s career advisor.

“What profession interests you?” he’d enquired.

“Why?” I answered.

“Why what?”

“Why a career?”

The advisor stared at me. “It’s what people do. To earn a living.”

“Right. But what’s the endgame? The point of it?”

Put another way, I might have asked whether it was just about ‘the job, the family, the fucking big television, the washing machine, the car, the compact disc player, the electronic tin opener, good health, low cholesterol, dental insurance, mortgage starter home…’[2] Wasn’t there more to life than this?

Apparently there wasn’t, as the careers advisor sighed and sent me on my way.

My fear was blindly subscribing to the whims of an increasingly materialistic society, with its shallow mediocrity and hollow indulgences, offering no deeper meaning or purpose than the indiscriminate production and consumption of Stuff, the treadmill existence of human battery hens.

The Industrial Revolution had produced impressive leaps in technological advancements, for the West in particular, improving people’s quality of life beyond question – healthcare, economic well-being, education, and so on. But where were the corresponding ethical advancements? Where was the philosophical framework to give value and meaning to these improvements? Our uniquely large brains had created systems and machines to make life safer and easier, but that was as far as it went. Human existence, and thus technology, boiled down to acquisition of power and resources. The key to success involved manipulating, exploiting, and generally competing against one’s fellow man and other species with Darwinian zeal, employing the very same qualities that won us pole position in nature’s league table in the first place.

But if Darwin was right, and natural selection is the blind chauffeur behind the wheel of evolution, driving human existence with no set route or destination in mind, why did people demand something “other” to give meaning to their lives? Like turning to a god, or some other invisible force pulling the strings according to a more intelligent design, providing people with a moral compass and higher purpose.

Life. How to live it?

Years after meeting with the career advisor, this still seemed to me the question that needed answering before any other, certainly before what cookie-cutter career to select from the corporate vending machine. In a twenty-first century world imperilled by the myopic attitude of humans, the search for a unifying Philosophy for Life, one that offered a big picture perspective on how to live sustainably on a crowded planet, was a quest worthy of the dangers that lay ahead.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” I said.

Steve grinned. “Great!”

“There is, however, one other question I have before signing on the dotted line.” I stabbed at the Atlantic and Pacific oceans on the map. “These blue areas––”

“Yes! Yes! The big wet bits,” he interrupted enthusiastically.

“Right, the um… big wet bits. How do we get across those then?”

“Easy. We’ll kayak from Scotland to Greenland, across to Canada, and then––”

“You’re crazy. Neither of us has kayaked before!”

“Oh shit, Jase. How hard can it be? I mean, all you gotta do is go like this, and we’ll get there eventually.” And with these reassuring words, he lurched to his feet and began whirling his arms around his head in the manner of a paddling kayaker.

I roared with laughter. “I was wrong. You’re not crazy. You’re fucking insane!”

Clearly, neither of us had any idea of what we were getting into. But, as we found ourselves reminding each other frequently from that point on, lack of experience isn’t a good enough reason not to try. Besides, as the sagacious old comic strip character Hagar the Horrible once noted, “Ignorance is the Mother of all Adventure.” And if I’d known what I was letting myself in for, I probably would have never agreed to join.

[1] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

[2] Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

The Big Idea – The Expedition Book Excerpt 2

“It’s incredible isn’t it,” Steve exclaimed, “how no one’s thought of it yet?” As he’d already pointed out, the Earth had been circumnavigated using everything from sailboats, to airplanes, to hot air balloons. Yet the purest, most ecologically sound method of all and doable for centuries, without using fossil fuels, was still up for grabs. “It may even be an original first!” he continued excitedly.

My old college pal Steve Smith and I were slumped on the kitchen floor of his flat in Paris, drinking Kronenbourg 1664 at two in the morning. A map of the world lay between us, paddled by the slowly revolving shadow of an ornate ceiling fan that gave the apartment an air of French colonial panache.

“So, you reckon all the other big firsts in exploration and adventure have been done?” I asked.

Steve had clearly done his homework, proceeding to reel off some of the more notable feats of the last century: Amundsen beating Scott to the South Pole in 1911; Hillary and Norgay summiting Everest in 1953; Armstrong setting foot on the moon in 1969. By 1992, however, it was slim pickings with the exception of the deep oceans and outer space. Nearly every square inch of the planet’s surface had been trampled upon, sailed across, flown, or driven over. Explorers and adventurers were fast becoming a rare breed, increasingly reliant upon inventive wordage to pass off a gimmick, or variation on a well-worn theme, as something genuinely different.

“It won’t be long before the media,” he finished off dryly, “run a story about the first blind-folded transsexual to snowboard down Everest in a thong.”

I smiled. “That’s been done already hasn’t it?”

“Not on a dustbin lid.”

Earlier that afternoon I’d flown from London, taking up Steve’s invitation for “a bit of piss up – you know, just like old times.” I should have smelt a rat right there. We’d barely seen each other since our final year at university. Why the grand reunion now all of a sudden?

The reason soon became clear after we rendezvoused at Charles de Gaulle Airport, and began lurching our way into the centre of the city on the metro. Clutching the steel bar above his head and raising his voice over the clattering wheels, Steve pitched the most ingenious, hair-brained, inspirational, irresponsible, guaranteed-to-give-your-mother-a-cardiac-arrest idea I had ever heard:

A human-powered circumnavigation of the globe…

Those few words hung suspended in the carriage for a moment, like a spell, putting goose bumps on my skin. I mean… to travel as far as you can go over land and sea, to the very ends of the Earth itself, under your own steam. No motors or sails. Just the power of the human body to get you there and back again. It had to be the ultimate human challenge.

As Steve continued outlining his plan, my head filled with wildly romantic images: riding bicycles across the barren steppes of Central Asia, trekking through the frozen wastes of the Himalayas, staring into the flames of a roaring campfire after a hard day hacking through the Amazonian rainforest. What about the oceans? I wondered. Rowing? Swimming? Paddling a Boogie Board? And why was Steve asking me of all people to join him?

I had absolutely no experience as a so-called “adventurer.” I’d travelled before, but never far off the beaten track: Kenya for three months after school, Cyprus during college, and the US for a spell immediately afterwards. From the age of sixteen, I devoted myself to singing in a grunge band that played in all the usual London toilets: the Falcon in Camden, the Half Moon in Putney, the Bull and Gate in Kentish Town. It was fun in the early days when we hadn’t taken ourselves too seriously. The first outfit, Dougal Goes to Norway, was a cover band distinguishable from the rest only by our Viking helmets and kilts – nothing on underneath. Later, we tried to make a proper go of it, releasing a vinyl EP. But with the entire band of five, plus two dogs and three cats, crammed in a two bedroom semi-detached house in Staines—The Shitehouse, as it was known—it had all become a bit of a grind.

I paid for my music habit with “Ballistic Cleaning Services Inc.,” a window cleaning business under contract with various restaurants and hotels in the West London area. When not leaning off ladders buffing windows, my partner Graham and I could typically be found wheezing up and down the A332 between Egham and Bracknell in the pride of the fleet, an X-reg Morris Marina van costing fifty quid from a scrap yard off the Old Kent Road. Spray-painted with the slogan “Get Realistic. Go Ballistic!” the company jalopy had no registration, road tax certificate, or insurance. But it was mechanically sound. And apart from one occasion when a rear wheel fell off and overtook us along Ascot High Street, it had never let us down.

Surely, however, these weren’t suitable qualifications for an undertaking such as this?

I shot Steve a sidelong look. “You sure you want me as your expedition partner?”

He nodded.

“And it’ll take around three years to complete you say?”

“If we can find sponsorship.”

Taking a swig, I surveyed my old friend. Like many of our deskbound graduate peers, he looked anaemic, badly in need of some sun. But while others were already turning paunches, Steve remained athletic and trim, not an extra ounce of fat on his body. And he still had the same steady cobalt gaze.

The first time we met I was supine on a stranger’s bed in one of the halls of residence, my arm around a girl, the other around a bottle of vodka. As the party wore on, I became dimly aware of the bed’s owner – Steve as it turned out – glaring at me from across the room.

Steve took an instant dislike to “that unruly farm boy” who’d soaked his bed in vodka. In time, however, attending the same biology and geography lectures, we became good friends. After a weekend poaching trout on Dartmoor when we should have been sitting through stultifying lectures on tor formation at a local field studies centre, we began taking off on spontaneous rambles around London. A three-day hike on the Chilterns in south Oxfordshire was one. Disembarking the train at Princes Risborough, we discovered neither of us had a sleeping bag, or a tent. It was the middle of January. Night-time temperatures were well below freezing. That first night we slept on the floor of a pub, sneaking back through the lavatory window we’d left ajar before being turfed out. The second night we lucked out, chancing upon a hay barn. Otherwise, we would have likely frozen to death.

Such was our early friendship, defined by episodes of kamikaze impetuousness swaggering along the knife-edge of fate – the sharper the edge the better.

Further fuelled by beer, brainlessness and a shared bent for challenging authority, we developed a penchant for egging each other on in a series of puerile college pranks, culminating in the erection of a fifteen-foot-high penis made from cardboard, party balloons and a pink bed sheet on an ornate spire at the entrance to campus. The pathetically limp protest directed at a visiting politician, made even more so by a light drizzle, was the best we could deliver as an anti-establishment statement at the time.

Then we went our separate ways: Steve into a career as an environmental scientist, myself into the giddy world of crooning in dive bars and cleaning windows.

“So where did you get the idea?” I asked.

Steve pursed his lips and shook his head at the memory. “I was working for the OECD at the time.[1] At first I thought I’d be making a difference, writing reports for politicians to integrate environmental sustainability into their economic development policies.”

Like a growing number in his field, Steve was alarmed by the ballooning number of human beings on the planet, ten billion by 2050, all aspiring to the same level of prosperity as the average Westerner – as seen on TV. Conservative estimates for meeting consumption demands without further depleting resources or biodiversity from 1994 levels was set at eight additional Earths.

“But the reports fell on deaf ears,” he went on. “An inhabitable planet for future generations is a lovely idea, the economists said, but we simply can’t afford it.”

Instead of falling into line with offers of promotion and salary increases, Steve took a stand.

“I felt like grabbing those short-term-thinking fuckwits by their starched collars and saying, ‘haven’t you seen the data on climate trends and species extinctions? We can’t afford not to do something. We’ll be next!’”

Small wonder he was duly assigned to a very different field of study: assessing the environmental impact of creosote on motorway fence posts. Their plan worked. Steve became disillusioned, staring out of the window, his mind wandering…

“That’s when I thought: what if I were free to do anything, anything at all, what would I be doing with my life right now?

He knew it had to be something to do with travel, and adventure, and on a big scale.

“And what bigger than around the world?”

The mode of propulsion was a stumbling block. It needed to be inexpensive, with minimal harm to the environment.

“Engines and I don’t get along. And if animals were involved, they’d all be dead within the month.”

Then it came to him. The Eureka Moment. The cheapest, least technical, lowest impact power of all. Human power.

“So, what do you think Jase? You up for it?”

I looked out through the kitchen window, past the wrought-iron balcony into the Paris night. The blank spaces on the map with no roads or towns marked I found utterly captivating. And a sabbatical from music might revitalize the songwriting juices. Moreover, if we left sooner rather than later, I might avoid a thorny court case for crashing the Ballistic cleaning van into a Rolls Royce off the Fulham Road and having to do a runner.

But there was something else.

I cast my mind back to when I was sixteen, sitting in the warm, dusty office of the school’s career advisor.

“What profession interests you?” he’d enquired.

“Why?” I answered.

“Why what?”

“Why a career?”

The advisor stared at me. “It’s what people do. To earn a living.”

“Right. But what’s the endgame? The point of it?”

Put another way, I might have asked whether it was just about ‘the job, the family, the fucking big television, the washing machine, the car, the compact disc player, the electronic tin opener, good health, low cholesterol, dental insurance, mortgage starter home…’[2] Wasn’t there more to life than this?

Apparently there wasn’t, as the careers advisor sighed and sent me on my way.

My fear was blindly subscribing to the whims of an increasingly materialistic society, with its shallow mediocrity and hollow indulgences, offering no deeper meaning or purpose than the indiscriminate production and consumption of Stuff, the treadmill existence of human battery hens.

The Industrial Revolution had produced impressive leaps in technological advancements, for the West in particular, improving people’s quality of life beyond question – healthcare, economic well-being, education, and so on. But where were the corresponding ethical advancements? Where was the philosophical framework to give value and meaning to these improvements? Our uniquely large brains had created systems and machines to make life safer and easier, but that was as far as it went. Human existence, and thus technology, boiled down to acquisition of power and resources. The key to success involved manipulating, exploiting, and generally competing against one’s fellow man and other species with Darwinian zeal, employing the very same qualities that won us pole position in nature’s league table in the first place.

But if Darwin was right, and natural selection is the blind chauffeur behind the wheel of evolution, driving human existence with no set route or destination in mind, why did people demand something “other” to give meaning to their lives? Like turning to a god, or some other invisible force pulling the strings according to a more intelligent design, providing people with a moral compass and higher purpose.

Life. How to live it?

Years after meeting with the career advisor, this still seemed to me the question that needed answering before any other, certainly before what cookie-cutter career to select from the corporate vending machine. In a twenty-first century world imperilled by the myopic attitude of humans, the search for a unifying Philosophy for Life, one that offered a big picture perspective on how to live sustainably on a crowded planet, was a quest worthy of the dangers that lay ahead.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” I said.

Steve grinned. “Great!”

“There is, however, one other question I have before signing on the dotted line.” I stabbed at the Atlantic and Pacific oceans on the map. “These blue areas––”

“Yes! Yes! The big wet bits,” he interrupted enthusiastically.

“Right, the um… big wet bits. How do we get across those then?”

“Easy. We’ll kayak from Scotland to Greenland, across to Canada, and then––”

“You’re crazy. Neither of us has kayaked before!”

“Oh shit, Jase. How hard can it be? I mean, all you gotta do is go like this, and we’ll get there eventually.” And with these reassuring words, he lurched to his feet and began whirling his arms around his head in the manner of a paddling kayaker.

I roared with laughter. “I was wrong. You’re not crazy. You’re fucking insane!”

Clearly, neither of us had any idea of what we were getting into. But, as we found ourselves reminding each other frequently from that point on, lack of experience isn’t a good enough reason not to try. Besides, as the sagacious old comic strip character Hagar the Horrible once noted, “Ignorance is the Mother of all Adventure.” And if I’d known what I was letting myself in for, I probably would have never agreed to join.

[1] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

[2] Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Book Excerpt 2 – The Big Idea

“It’s incredible isn’t it,” Steve exclaimed, “how no one’s thought of it yet?” As he’d already pointed out, the Earth had been circumnavigated using everything from sailboats, to airplanes, to hot air balloons. Yet the purest, most ecologically sound method of all and doable for centuries, without using fossil fuels, was still up for grabs. “It may even be an original first!” he continued excitedly.

My old college pal Steve Smith and I were slumped on the kitchen floor of his flat in Paris, drinking Kronenbourg 1664 at two in the morning. A map of the world lay between us, paddled by the slowly revolving shadow of an ornate ceiling fan that gave the apartment an air of French colonial panache.

“So, you reckon all the other big firsts in exploration and adventure have been done?” I asked.

Steve had clearly done his homework, proceeding to reel off some of the more notable feats of the last century: Amundsen beating Scott to the South Pole in 1911; Hillary and Norgay summiting Everest in 1953; Armstrong setting foot on the moon in 1969. By 1992, however, it was slim pickings with the exception of the deep oceans and outer space. Nearly every square inch of the planet’s surface had been trampled upon, sailed across, flown, or driven over. Explorers and adventurers were fast becoming a rare breed, increasingly reliant upon inventive wordage to pass off a gimmick, or variation on a well-worn theme, as something genuinely different.

“It won’t be long before the media,” he finished off dryly, “run a story about the first blind-folded transsexual to snowboard down Everest in a thong.”

I smiled. “That’s been done already hasn’t it?”

“Not on a dustbin lid.”

Earlier that afternoon I’d flown from London, taking up Steve’s invitation for “a bit of piss up – you know, just like old times.” I should have smelt a rat right there. We’d barely seen each other since our final year at university. Why the grand reunion now all of a sudden?

The reason soon became clear after we rendezvoused at Charles de Gaulle Airport, and began lurching our way into the centre of the city on the metro. Clutching the steel bar above his head and raising his voice over the clattering wheels, Steve pitched the most ingenious, hair-brained, inspirational, irresponsible, guaranteed-to-give-your-mother-a-cardiac-arrest idea I had ever heard:

A human-powered circumnavigation of the globe…

Those few words hung suspended in the carriage for a moment, like a spell, putting goose bumps on my skin. I mean… to travel as far as you can go over land and sea, to the very ends of the Earth itself, under your own steam. No motors or sails. Just the power of the human body to get you there and back again. It had to be the ultimate human challenge.

As Steve continued outlining his plan, my head filled with wildly romantic images: riding bicycles across the barren steppes of Central Asia, trekking through the frozen wastes of the Himalayas, staring into the flames of a roaring campfire after a hard day hacking through the Amazonian rainforest. What about the oceans? I wondered. Rowing? Swimming? Paddling a Boogie Board? And why was Steve asking me of all people to join him?

I had absolutely no experience as a so-called “adventurer.” I’d travelled before, but never far off the beaten track: Kenya for three months after school, Cyprus during college, and the US for a spell immediately afterwards. From the age of sixteen, I devoted myself to singing in a grunge band that played in all the usual London toilets: the Falcon in Camden, the Half Moon in Putney, the Bull and Gate in Kentish Town. It was fun in the early days when we hadn’t taken ourselves too seriously. The first outfit, Dougal Goes to Norway, was a cover band distinguishable from the rest only by our Viking helmets and kilts – nothing on underneath. Later, we tried to make a proper go of it, releasing a vinyl EP. But with the entire band of five, plus two dogs and three cats, crammed in a two bedroom semi-detached house in Staines—The Shitehouse, as it was known—it had all become a bit of a grind.

I paid for my music habit with “Ballistic Cleaning Services Inc.,” a window cleaning business under contract with various restaurants and hotels in the West London area. When not leaning off ladders buffing windows, my partner Graham and I could typically be found wheezing up and down the A332 between Egham and Bracknell in the pride of the fleet, an X-reg Morris Marina van costing fifty quid from a scrap yard off the Old Kent Road. Spray-painted with the slogan “Get Realistic. Go Ballistic!” the company jalopy had no registration, road tax certificate, or insurance. But it was mechanically sound. And apart from one occasion when a rear wheel fell off and overtook us along Ascot High Street, it had never let us down.

Surely, however, these weren’t suitable qualifications for an undertaking such as this?

I shot Steve a sidelong look. “You sure you want me as your expedition partner?”

He nodded.

“And it’ll take around three years to complete you say?”

“If we can find sponsorship.”

Taking a swig, I surveyed my old friend. Like many of our deskbound graduate peers, he looked anaemic, badly in need of some sun. But while others were already turning paunches, Steve remained athletic and trim, not an extra ounce of fat on his body. And he still had the same steady cobalt gaze.

The first time we met I was supine on a stranger’s bed in one of the halls of residence, my arm around a girl, the other around a bottle of vodka. As the party wore on, I became dimly aware of the bed’s owner – Steve as it turned out – glaring at me from across the room.

Steve took an instant dislike to “that unruly farm boy” who’d soaked his bed in vodka. In time, however, attending the same biology and geography lectures, we became good friends. After a weekend poaching trout on Dartmoor when we should have been sitting through stultifying lectures on tor formation at a local field studies centre, we began taking off on spontaneous rambles around London. A three-day hike on the Chilterns in south Oxfordshire was one. Disembarking the train at Princes Risborough, we discovered neither of us had a sleeping bag, or a tent. It was the middle of January. Night-time temperatures were well below freezing. That first night we slept on the floor of a pub, sneaking back through the lavatory window we’d left ajar before being turfed out. The second night we lucked out, chancing upon a hay barn. Otherwise, we would have likely frozen to death.

Such was our early friendship, defined by episodes of kamikaze impetuousness swaggering along the knife-edge of fate – the sharper the edge the better.

Further fuelled by beer, brainlessness and a shared bent for challenging authority, we developed a penchant for egging each other on in a series of puerile college pranks, culminating in the erection of a fifteen-foot-high penis made from cardboard, party balloons and a pink bed sheet on an ornate spire at the entrance to campus. The pathetically limp protest directed at a visiting politician, made even more so by a light drizzle, was the best we could deliver as an anti-establishment statement at the time.

Then we went our separate ways: Steve into a career as an environmental scientist, myself into the giddy world of crooning in dive bars and cleaning windows.

“So where did you get the idea?” I asked.

Steve pursed his lips and shook his head at the memory. “I was working for the OECD at the time.[1] At first I thought I’d be making a difference, writing reports for politicians to integrate environmental sustainability into their economic development policies.”

Like a growing number in his field, Steve was alarmed by the ballooning number of human beings on the planet, ten billion by 2050, all aspiring to the same level of prosperity as the average Westerner – as seen on TV. Conservative estimates for meeting consumption demands without further depleting resources or biodiversity from 1994 levels was set at eight additional Earths.

“But the reports fell on deaf ears,” he went on. “An inhabitable planet for future generations is a lovely idea, the economists said, but we simply can’t afford it.”

Instead of falling into line with offers of promotion and salary increases, Steve took a stand.

“I felt like grabbing those short-term-thinking fuckwits by their starched collars and saying, ‘haven’t you seen the data on climate trends and species extinctions? We can’t afford not to do something. We’ll be next!’”

Small wonder he was duly assigned to a very different field of study: assessing the environmental impact of creosote on motorway fence posts. Their plan worked. Steve became disillusioned, staring out of the window, his mind wandering…

“That’s when I thought: what if I were free to do anything, anything at all, what would I be doing with my life right now?

He knew it had to be something to do with travel, and adventure, and on a big scale.

“And what bigger than around the world?”

The mode of propulsion was a stumbling block. It needed to be inexpensive, with minimal harm to the environment.

“Engines and I don’t get along. And if animals were involved, they’d all be dead within the month.”

Then it came to him. The Eureka Moment. The cheapest, least technical, lowest impact power of all. Human power.

“So, what do you think Jase? You up for it?”

I looked out through the kitchen window, past the wrought-iron balcony into the Paris night. The blank spaces on the map with no roads or towns marked I found utterly captivating. And a sabbatical from music might revitalize the songwriting juices. Moreover, if we left sooner rather than later, I might avoid a thorny court case for crashing the Ballistic cleaning van into a Rolls Royce off the Fulham Road and having to do a runner.

But there was something else.

I cast my mind back to when I was sixteen, sitting in the warm, dusty office of the school’s career advisor.

“What profession interests you?” he’d enquired.

“Why?” I answered.

“Why what?”

“Why a career?”

The advisor stared at me. “It’s what people do. To earn a living.”

“Right. But what’s the endgame? The point of it?”

Put another way, I might have asked whether it was just about ‘the job, the family, the fucking big television, the washing machine, the car, the compact disc player, the electronic tin opener, good health, low cholesterol, dental insurance, mortgage starter home…’[2] Wasn’t there more to life than this?

Apparently there wasn’t, as the careers advisor sighed and sent me on my way.

My fear was blindly subscribing to the whims of an increasingly materialistic society, with its shallow mediocrity and hollow indulgences, offering no deeper meaning or purpose than the indiscriminate production and consumption of Stuff, the treadmill existence of human battery hens.

The Industrial Revolution had produced impressive leaps in technological advancements, for the West in particular, improving people’s quality of life beyond question – healthcare, economic well-being, education, and so on. But where were the corresponding ethical advancements? Where was the philosophical framework to give value and meaning to these improvements? Our uniquely large brains had created systems and machines to make life safer and easier, but that was as far as it went. Human existence, and thus technology, boiled down to acquisition of power and resources. The key to success involved manipulating, exploiting, and generally competing against one’s fellow man and other species with Darwinian zeal, employing the very same qualities that won us pole position in nature’s league table in the first place.

But if Darwin was right, and natural selection is the blind chauffeur behind the wheel of evolution, driving human existence with no set route or destination in mind, why did people demand something “other” to give meaning to their lives? Like turning to a god, or some other invisible force pulling the strings according to a more intelligent design, providing people with a moral compass and higher purpose.

Life. How to live it?

Years after meeting with the career advisor, this still seemed to me the question that needed answering before any other, certainly before what cookie-cutter career to select from the corporate vending machine. In a twenty-first century world imperilled by the myopic attitude of humans, the search for a unifying Philosophy for Life, one that offered a big picture perspective on how to live sustainably on a crowded planet, was a quest worthy of the dangers that lay ahead.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” I said.

Steve grinned. “Great!”

“There is, however, one other question I have before signing on the dotted line.” I stabbed at the Atlantic and Pacific oceans on the map. “These blue areas––”

“Yes! Yes! The big wet bits,” he interrupted enthusiastically.

“Right, the um… big wet bits. How do we get across those then?”

“Easy. We’ll kayak from Scotland to Greenland, across to Canada, and then––”

“You’re crazy. Neither of us has kayaked before!”

“Oh shit, Jase. How hard can it be? I mean, all you gotta do is go like this, and we’ll get there eventually.” And with these reassuring words, he lurched to his feet and began whirling his arms around his head in the manner of a paddling kayaker.

I roared with laughter. “I was wrong. You’re not crazy. You’re fucking insane!”

Clearly, neither of us had any idea of what we were getting into. But, as we found ourselves reminding each other frequently from that point on, lack of experience isn’t a good enough reason not to try. Besides, as the sagacious old comic strip character Hagar the Horrible once noted, “Ignorance is the Mother of all Adventure.” And if I’d known what I was letting myself in for, I probably would have never agreed to join.

[1] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

[2] Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

June 24, 2012

Croc Attack – The Expedition Book excerpt 1

5:17 pm: Rounding the southern edge of Lookout Point, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, like whenyou know you’re being watched.

I glanced behind.

Two lidless eyes and a snub nose, gliding behind my kayak.

Fear gripped me instantly. Not the jittery type like when you come across a large spider in the bath. But the primal, fundamentally hard-wired horror of being hunted, considered prey. And the last fifty yards to shore, which should have been a winding down and quiet reflection on the entire Pacific crossing, instead became an adrenaline charged eruption of pumping arms and hammering heartbeat.

If it takes me in the water, I thought, I’m finished…

I tore frantically at the surface, snatching occasional glimpses behind. The predator was gaining easily.

My paddle blade touched sand. In a single movement, I yanked the Velcro fastenings on the spray-skirt, sprang from the cockpit, and spun to face my pursuer.

Nothing.

It was gone.

My blistered and swollen hands were shaking, stomach churning.

Shock. Yes, it must be shock kicking in…

Twenty-two miles was also a fair distance to paddle in five and a half hours, and a leak in the canvas hull had obliged frequent bailing. The sun played its part, too, radiating with savage ferocity from the mirrored surface of the Coral Sea, sapping every ounce from overstretched, protesting muscles.

For now, though, I was safe on the beach, as long as daylight held.

I dumped the first load at the high tide mark – double-bladed wooden paddle, spray-skirt, and waterproof bags – turned to get another load, and froze.

At fifteen feet long, the way the thing bored through the slashing surf resembled a giant battering ram lathered in black pitch, brought to life by some abominable spell. With unswerving intent, the reptile swaggered towards my kayak parked at the water’s edge, the monster in a low budget horror movie that just keeps coming.

I snatched the paddle and started running towards the water. What I would do when I got there I had no idea. I just knew my water, food, and satellite phone were about to be dragged out to sea. That would be it. Game Over.

This was a remote stretch of Queensland’s northeast seaboard, 120 miles north of Cooktown, the last coastal settlement on the Cape York Peninsula before Papua New Guinea, four hundred miles to the north. I was well aware estuarine crocodiles populated these waters. It was hard not to be. Every other sentence out of a local’s mouth had a croc in it.

“There’s some big lizards out there mate,” an aboriginal guide, Russell Butler, told me earlier in the day setting out from the beach at the Lizard Island Research Centre. “Watch yourself, orright?!”

The chance meeting already seemed a lifetime ago. As I ran, an eighties disco anthem I’d been humming all afternoon began looping in my head.

“Last night a deejay saved my life…

Last night a deejay saved my life from a broken heart.”

My head often played tricks like this when the shit hit the fan. Black, sadistic humour, pretending everything was okay, situation normal. A defence mechanism to allow a person to keep functioning.

Nearing my boat, the croc was just yards away on the opposite side. Huge. Not so much the length as the width, a good four feet at the midriff, dark oblong scales forming a pattern of raised armour on the topside, merging to a smooth cream underbelly.

Using the hull as a protective shield, I reached over with my paddle and prodded its snout.

“Shoo, go on now, bugger off…”

The reptile responded by opening its mouth, revealing rows of ragged teeth set porcelain-white against a cavernous backdrop. It expelled a low hiss.

Up until now, the creature only appeared to have an issue with my kayak.[1] That was about to change. Tail raised, mouth ajar, the croc lunged towards me. At the same time I stabbed. Gin trap jaws snapped over the paddle blade.

A tug of war ensued. The harder I pulled, the tighter its grip. At 1,500 pounds, the animal only had to flick its head and the paddle would be torn from my hands. In desperation, I thrust away from me, into its throat. The blade came free. Then I swung it as hard as I could. A sharp splintering of wood, and I found myself holding the fractured end.

Shit!

Maybe I’d actually hit the eye like I was aiming for. Or, after five attempts at crossing the Pacific, enduring 8,320 miles of gale force winds, monstrous seas, blood poisoning, insanity, and countercurrents sweeping me back for weeks at a time, the sea gods had decided enough was enough.

The croc turned and slipped back into deeper water.

Adrenaline surged and my belly heaved.

I threw up.

“Get off the beach now,” the voice commanded urgently. I’d retrieved my satellite phone from the rear compartment of the kayak, and called my Aussie outback expert in Cairns, John Andrews. “They’re bastards, wily as hell. They can’t climb, though. You’re best off looking for higher ground. If you camp on the beach, it’ll wait until you’re asleep. Then it’ll come ‘n getcha.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. A few months earlier, a family had been camping less than a hundred miles to the northwest in Bathurst Bay. In the early hours of the morning, thirty-four-year-old Andrew Kerr found himself being dragged from his tent – pitched thirty yards from the water’s edge – by a fourteen-foot saltie. Alicia Sorohan, a sixty-year-old grandmother, leapt onto the animal’s back, forcing it to release. The crocodile then turned on her, breaking her nose and arm. Fortunately, her son arrived on the scene and dispatched it with a revolver – something I didn’t have.

It was dark by the time I hobbled with the last of my gear up the steep, narrow path to the top of the headland. My feet were swollen. Like an idiot, I’d left my sandals on Bob and Tanya Lamb’s porch. I slumped in the windswept grass, utterly spent, head lolling against a leathery tussock. The Southeast Trade Winds hushed to a whisper, and droves of mosquitoes appeared from nowhere, zinging in my ears. That was fine. I had no intention of sleeping. Far below, glowing orange in the beam of my headlamp, a pair of sleepless eyes patrolled back and forth.

I reached for my Ocean Ring. It was safe, on my left ring finger. I remembered the day I first put it on outside the Golden Gate Bridge, and the pledge I’d made to the sea: From now on, we are one… Had it worked? Perhaps. The Pacific, after all, had finally let me pass.

I cast further back, squinting into the depths of the Southern Hemisphere night, trying to recollect… How did I get to be stranded 25,000 miles from home, at the top of some godforsaken cliff, man-eater at the bottom, being bitten to death by mosquitoes in the first place?

[1] Since hunting was banned in 1974, the “saltie” population in Australia has made a spectacular recovery, particularly in the northern part of the country where fewer people live. Competition for territory has risen accordingly, and my kayak, being roughly the same size and shape as a young male, was likely mistaken for an intruder by the dominant male of the area.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Croc Attack – The Expedition Book Excerpt 1

5:17 pm: Rounding the southern edge of Lookout Point, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, like whenyou know you’re being watched.

I glanced behind.

Two lidless eyes and a snub nose, gliding behind my kayak.

Fear gripped me instantly. Not the jittery type like when you come across a large spider in the bath. But the primal, fundamentally hard-wired horror of being hunted, considered prey. And the last fifty yards to shore, which should have been a winding down and quiet reflection on the entire Pacific crossing, instead became an adrenaline charged eruption of pumping arms and hammering heartbeat.

If it takes me in the water, I thought, I’m finished…

I tore frantically at the surface, snatching occasional glimpses behind. The predator was gaining easily.

My paddle blade touched sand. In a single movement, I yanked the Velcro fastenings on the spray-skirt, sprang from the cockpit, and spun to face my pursuer.

Nothing.

It was gone.

My blistered and swollen hands were shaking, stomach churning.

Shock. Yes, it must be shock kicking in…

Twenty-two miles was also a fair distance to paddle in five and a half hours, and a leak in the canvas hull had obliged frequent bailing. The sun played its part, too, radiating with savage ferocity from the mirrored surface of the Coral Sea, sapping every ounce from overstretched, protesting muscles.

For now, though, I was safe on the beach, as long as daylight held.

I dumped the first load at the high tide mark – double-bladed wooden paddle, spray-skirt, and waterproof bags – turned to get another load, and froze.

At fifteen feet long, the way the thing bored through the slashing surf resembled a giant battering ram lathered in black pitch, brought to life by some abominable spell. With unswerving intent, the reptile swaggered towards my kayak parked at the water’s edge, the monster in a low budget horror movie that just keeps coming.

I snatched the paddle and started running towards the water. What I would do when I got there I had no idea. I just knew my water, food, and satellite phone were about to be dragged out to sea. That would be it. Game Over.

This was a remote stretch of Queensland’s northeast seaboard, 120 miles north of Cooktown, the last coastal settlement on the Cape York Peninsula before Papua New Guinea, four hundred miles to the north. I was well aware estuarine crocodiles populated these waters. It was hard not to be. Every other sentence out of a local’s mouth had a croc in it.

“There’s some big lizards out there mate,” an aboriginal guide, Russell Butler, told me earlier in the day setting out from the beach at the Lizard Island Research Centre. “Watch yourself, orright?!”

The chance meeting already seemed a lifetime ago. As I ran, an eighties disco anthem I’d been humming all afternoon began looping in my head.

“Last night a deejay saved my life…

Last night a deejay saved my life from a broken heart.”

My head often played tricks like this when the shit hit the fan. Black, sadistic humour, pretending everything was okay, situation normal. A defence mechanism to allow a person to keep functioning.

Nearing my boat, the croc was just yards away on the opposite side. Huge. Not so much the length as the width, a good four feet at the midriff, dark oblong scales forming a pattern of raised armour on the topside, merging to a smooth cream underbelly.

Using the hull as a protective shield, I reached over with my paddle and prodded its snout.

“Shoo, go on now, bugger off…”

The reptile responded by opening its mouth, revealing rows of ragged teeth set porcelain-white against a cavernous backdrop. It expelled a low hiss.

Up until now, the creature only appeared to have an issue with my kayak.[1] That was about to change. Tail raised, mouth ajar, the croc lunged towards me. At the same time I stabbed. Gin trap jaws snapped over the paddle blade.

A tug of war ensued. The harder I pulled, the tighter its grip. At 1,500 pounds, the animal only had to flick its head and the paddle would be torn from my hands. In desperation, I thrust away from me, into its throat. The blade came free. Then I swung it as hard as I could. A sharp splintering of wood, and I found myself holding the fractured end.

Shit!

Maybe I’d actually hit the eye like I was aiming for. Or, after five attempts at crossing the Pacific, enduring 8,320 miles of gale force winds, monstrous seas, blood poisoning, insanity, and countercurrents sweeping me back for weeks at a time, the sea gods had decided enough was enough.

The croc turned and slipped back into deeper water.

Adrenaline surged and my belly heaved.

I threw up.

“Get off the beach now,” the voice commanded urgently. I’d retrieved my satellite phone from the rear compartment of the kayak, and called my Aussie outback expert in Cairns, John Andrews. “They’re bastards, wily as hell. They can’t climb, though. You’re best off looking for higher ground. If you camp on the beach, it’ll wait until you’re asleep. Then it’ll come ‘n getcha.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. A few months earlier, a family had been camping less than a hundred miles to the northwest in Bathurst Bay. In the early hours of the morning, thirty-four-year-old Andrew Kerr found himself being dragged from his tent – pitched thirty yards from the water’s edge – by a fourteen-foot saltie. Alicia Sorohan, a sixty-year-old grandmother, leapt onto the animal’s back, forcing it to release. The crocodile then turned on her, breaking her nose and arm. Fortunately, her son arrived on the scene and dispatched it with a revolver – something I didn’t have.

It was dark by the time I hobbled with the last of my gear up the steep, narrow path to the top of the headland. My feet were swollen. Like an idiot, I’d left my sandals on Bob and Tanya Lamb’s porch. I slumped in the windswept grass, utterly spent, head lolling against a leathery tussock. The Southeast Trade Winds hushed to a whisper, and droves of mosquitoes appeared from nowhere, zinging in my ears. That was fine. I had no intention of sleeping. Far below, glowing orange in the beam of my headlamp, a pair of sleepless eyes patrolled back and forth.

I reached for my Ocean Ring. It was safe, on my left ring finger. I remembered the day I first put it on outside the Golden Gate Bridge, and the pledge I’d made to the sea: From now on, we are one… Had it worked? Perhaps. The Pacific, after all, had finally let me pass.

I cast further back, squinting into the depths of the Southern Hemisphere night, trying to recollect… How did I get to be stranded 25,000 miles from home, at the top of some godforsaken cliff, man-eater at the bottom, being bitten to death by mosquitoes in the first place?

[1] Since hunting was banned in 1974, the “saltie” population in Australia has made a spectacular recovery, particularly in the northern part of the country where fewer people live. Competition for territory has risen accordingly, and my kayak, being roughly the same size and shape as a young male, was likely mistaken for an intruder by the dominant male of the area.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Book Excerpt 1 – Croc Attack

5:17 pm: Rounding the southern edge of Lookout Point, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, like whenyou know you’re being watched.

I glanced behind.

Two lidless eyes and a snub nose, gliding behind my kayak.

Fear gripped me instantly. Not the jittery type like when you come across a large spider in the bath. But the primal, fundamentally hard-wired horror of being hunted, considered prey. And the last fifty yards to shore, which should have been a winding down and quiet reflection on the entire Pacific crossing, instead became an adrenaline charged eruption of pumping arms and hammering heartbeat.

If it takes me in the water, I thought, I’m finished…

I tore frantically at the surface, snatching occasional glimpses behind. The predator was gaining easily.

My paddle blade touched sand. In a single movement, I yanked the Velcro fastenings on the spray-skirt, sprang from the cockpit, and spun to face my pursuer.

Nothing.

It was gone.

My blistered and swollen hands were shaking, stomach churning.

Shock. Yes, it must be shock kicking in…

Twenty-two miles was also a fair distance to paddle in five and a half hours, and a leak in the canvas hull had obliged frequent bailing. The sun played its part, too, radiating with savage ferocity from the mirrored surface of the Coral Sea, sapping every ounce from overstretched, protesting muscles.

For now, though, I was safe on the beach, as long as daylight held.

I dumped the first load at the high tide mark – double-bladed wooden paddle, spray-skirt, and waterproof bags – turned to get another load, and froze.

At fifteen feet long, the way the thing bored through the slashing surf resembled a giant battering ram lathered in black pitch, brought to life by some abominable spell. With unswerving intent, the reptile swaggered towards my kayak parked at the water’s edge, the monster in a low budget horror movie that just keeps coming.

I snatched the paddle and started running towards the water. What I would do when I got there I had no idea. I just knew my water, food, and satellite phone were about to be dragged out to sea. That would be it. Game Over.

This was a remote stretch of Queensland’s northeast seaboard, 120 miles north of Cooktown, the last coastal settlement on the Cape York Peninsula before Papua New Guinea, four hundred miles to the north. I was well aware estuarine crocodiles populated these waters. It was hard not to be. Every other sentence out of a local’s mouth had a croc in it.

“There’s some big lizards out there mate,” an aboriginal guide, Russell Butler, told me earlier in the day setting out from the beach at the Lizard Island Research Centre. “Watch yourself, orright?!”

The chance meeting already seemed a lifetime ago. As I ran, an eighties disco anthem I’d been humming all afternoon began looping in my head.

“Last night a deejay saved my life…

Last night a deejay saved my life from a broken heart.”

My head often played tricks like this when the shit hit the fan. Black, sadistic humour, pretending everything was okay, situation normal. A defence mechanism to allow a person to keep functioning.

Nearing my boat, the croc was just yards away on the opposite side. Huge. Not so much the length as the width, a good four feet at the midriff, dark oblong scales forming a pattern of raised armour on the topside, merging to a smooth cream underbelly.

Using the hull as a protective shield, I reached over with my paddle and prodded its snout.

“Shoo, go on now, bugger off…”

The reptile responded by opening its mouth, revealing rows of ragged teeth set porcelain-white against a cavernous backdrop. It expelled a low hiss.

Up until now, the creature only appeared to have an issue with my kayak.[1] That was about to change. Tail raised, mouth ajar, the croc lunged towards me. At the same time I stabbed. Gin trap jaws snapped over the paddle blade.

A tug of war ensued. The harder I pulled, the tighter its grip. At 1,500 pounds, the animal only had to flick its head and the paddle would be torn from my hands. In desperation, I thrust away from me, into its throat. The blade came free. Then I swung it as hard as I could. A sharp splintering of wood, and I found myself holding the fractured end.

Shit!

Maybe I’d actually hit the eye like I was aiming for. Or, after five attempts at crossing the Pacific, enduring 8,320 miles of gale force winds, monstrous seas, blood poisoning, insanity, and countercurrents sweeping me back for weeks at a time, the sea gods had decided enough was enough.

The croc turned and slipped back into deeper water.

Adrenaline surged and my belly heaved.

I threw up.

“Get off the beach now,” the voice commanded urgently. I’d retrieved my satellite phone from the rear compartment of the kayak, and called my Aussie outback expert in Cairns, John Andrews. “They’re bastards, wily as hell. They can’t climb, though. You’re best off looking for higher ground. If you camp on the beach, it’ll wait until you’re asleep. Then it’ll come ‘n getcha.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. A few months earlier, a family had been camping less than a hundred miles to the northwest in Bathurst Bay. In the early hours of the morning, thirty-four-year-old Andrew Kerr found himself being dragged from his tent – pitched thirty yards from the water’s edge – by a fourteen-foot saltie. Alicia Sorohan, a sixty-year-old grandmother, leapt onto the animal’s back, forcing it to release. The crocodile then turned on her, breaking her nose and arm. Fortunately, her son arrived on the scene and dispatched it with a revolver – something I didn’t have.

It was dark by the time I hobbled with the last of my gear up the steep, narrow path to the top of the headland. My feet were swollen. Like an idiot, I’d left my sandals on Bob and Tanya Lamb’s porch. I slumped in the windswept grass, utterly spent, head lolling against a leathery tussock. The Southeast Trade Winds hushed to a whisper, and droves of mosquitoes appeared from nowhere, zinging in my ears. That was fine. I had no intention of sleeping. Far below, glowing orange in the beam of my headlamp, a pair of sleepless eyes patrolled back and forth.

I reached for my Ocean Ring. It was safe, on my left ring finger. I remembered the day I first put it on outside the Golden Gate Bridge, and the pledge I’d made to the sea: From now on, we are one… Had it worked? Perhaps. The Pacific, after all, had finally let me pass.

I cast further back, squinting into the depths of the Southern Hemisphere night, trying to recollect… How did I get to be stranded 25,000 miles from home, at the top of some godforsaken cliff, man-eater at the bottom, being bitten to death by mosquitoes in the first place?

[1] Since hunting was banned in 1974, the “saltie” population in Australia has made a spectacular recovery, particularly in the northern part of the country where fewer people live. Competition for territory has risen accordingly, and my kayak, being roughly the same size and shape as a young male, was likely mistaken for an intruder by the dominant male of the area.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Excerpt 1 – Croc Attack

This blog features excerpts from The Expedition, true story of the first human-powered circumnavigation of the Earth, published North America August 1, and UK & rest of the world January 1, 2013.

Download this excerpt to your tablet/iPad/mobile device as a pdf

Cape York Peninsula, Australia. May 13, 2005

5:17 pm: Rounding the southern edge of Lookout Point, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, like whenyou know you’re being watched.

I glanced behind.

Two lidless eyes and a snub nose, gliding behind my kayak.

Fear gripped me instantly. Not the jittery type like when you come across a large spider in the bath. But the primal, fundamentally hard-wired horror of being hunted, considered prey. And the last fifty yards to shore, which should have been a winding down and quiet reflection on the entire Pacific crossing, instead became an adrenaline charged eruption of pumping arms and hammering heartbeat.

If it takes me in the water, I thought, I’m finished…

I tore frantically at the surface, snatching occasional glimpses behind. The predator was gaining easily.

My paddle blade touched sand. In a single movement, I yanked the Velcro fastenings on the spray-skirt, sprang from the cockpit, and spun to face my pursuer.

Nothing.

It was gone.

My blistered and swollen hands were shaking, stomach churning.

Shock. Yes, it must be shock kicking in…

Twenty-two miles was also a fair distance to paddle in five and a half hours, and a leak in the canvas hull had obliged frequent bailing. The sun played its part, too, radiating with savage ferocity from the mirrored surface of the Coral Sea, sapping every ounce from overstretched, protesting muscles.

For now, though, I was safe on the beach, as long as daylight held.

I dumped the first load at the high tide mark – double-bladed wooden paddle, spray-skirt, and waterproof bags – turned to get another load, and froze.

At fifteen feet long, the way the thing bored through the slashing surf resembled a giant battering ram lathered in black pitch, brought to life by some abominable spell. With unswerving intent, the reptile swaggered towards my kayak parked at the water’s edge, the monster in a low budget horror movie that just keeps coming.

I snatched the paddle and started running towards the water. What I would do when I got there I had no idea. I just knew my water, food, and satellite phone were about to be dragged out to sea. That would be it. Game Over.

This was a remote stretch of Queensland’s northeast seaboard, 120 miles north of Cooktown, the last coastal settlement on the Cape York Peninsula before Papua New Guinea, four hundred miles to the north. I was well aware estuarine crocodiles populated these waters. It was hard not to be. Every other sentence out of a local’s mouth had a croc in it.

“There’s some big lizards out there mate,” an aboriginal guide, Russell Butler, told me earlier in the day setting out from the beach at the Lizard Island Research Centre. “Watch yourself, orright?!”

The chance meeting already seemed a lifetime ago. As I ran, an eighties disco anthem I’d been humming all afternoon began looping in my head.

“Last night a deejay saved my life…

Last night a deejay saved my life from a broken heart.”

My head often played tricks like this when the shit hit the fan. Black, sadistic humour, pretending everything was okay, situation normal. A defence mechanism to allow a person to keep functioning.

Nearing my boat, the croc was just yards away on the opposite side. Huge. Not so much the length as the width, a good four feet at the midriff, dark oblong scales forming a pattern of raised armour on the topside, merging to a smooth cream underbelly.

Using the hull as a protective shield, I reached over with my paddle and prodded its snout.

“Shoo, go on now, bugger off…”

The reptile responded by opening its mouth, revealing rows of ragged teeth set porcelain-white against a cavernous backdrop. It expelled a low hiss.

Up until now, the creature only appeared to have an issue with my kayak.[1] That was about to change. Tail raised, mouth ajar, the croc lunged towards me. At the same time I stabbed. Gin trap jaws snapped over the paddle blade.

A tug of war ensued. The harder I pulled, the tighter its grip. At 1,500 pounds, the animal only had to flick its head and the paddle would be torn from my hands. In desperation, I thrust away from me, into its throat. The blade came free. Then I swung it as hard as I could. A sharp splintering of wood, and I found myself holding the fractured end.

Shit!

Maybe I’d actually hit the eye like I was aiming for. Or, after five attempts at crossing the Pacific, enduring 8,320 miles of gale force winds, monstrous seas, blood poisoning, insanity, and countercurrents sweeping me back for weeks at a time, the sea gods had decided enough was enough.

The croc turned and slipped back into deeper water.

Adrenaline surged and my belly heaved.

I threw up.

“Get off the beach now,” the voice commanded urgently. I’d retrieved my satellite phone from the rear compartment of the kayak, and called my Aussie outback expert in Cairns, John Andrews. “They’re bastards, wily as hell. They can’t climb, though. You’re best off looking for higher ground. If you camp on the beach, it’ll wait until you’re asleep. Then it’ll come ‘n getcha.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. A few months earlier, a family had been camping less than a hundred miles to the northwest in Bathurst Bay. In the early hours of the morning, thirty-four-year-old Andrew Kerr found himself being dragged from his tent – pitched thirty yards from the water’s edge – by a fourteen-foot saltie. Alicia Sorohan, a sixty-year-old grandmother, leapt onto the animal’s back, forcing it to release. The crocodile then turned on her, breaking her nose and arm. Fortunately, her son arrived on the scene and dispatched it with a revolver – something I didn’t have.

It was dark by the time I hobbled with the last of my gear up the steep, narrow path to the top of the headland. My feet were swollen. Like an idiot, I’d left my sandals on Bob and Tanya Lamb’s porch. I slumped in the windswept grass, utterly spent, head lolling against a leathery tussock. The Southeast Trade Winds hushed to a whisper, and droves of mosquitoes appeared from nowhere, zinging in my ears. That was fine. I had no intention of sleeping. Far below, glowing orange in the beam of my headlamp, a pair of sleepless eyes patrolled back and forth.

I reached for my Ocean Ring. It was safe, on my left ring finger. I remembered the day I first put it on outside the Golden Gate Bridge, and the pledge I’d made to the sea: From now on, we are one… Had it worked? Perhaps. The Pacific, after all, had finally let me pass.

I cast further back, squinting into the depths of the Southern Hemisphere night, trying to recollect… How did I get to be stranded 25,000 miles from home, at the top of some godforsaken cliff, man-eater at the bottom, being bitten to death by mosquitoes in the first place?

[1] Since hunting was banned in 1974, the “saltie” population in Australia has made a spectacular recovery, particularly in the northern part of the country where fewer people live. Competition for territory has risen accordingly, and my kayak, being roughly the same size and shape as a young male, was likely mistaken for an intruder by the dominant male of the area.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis