Jason Lewis's Blog, page 4

May 10, 2015

Expedition Base Camp Darwin Style

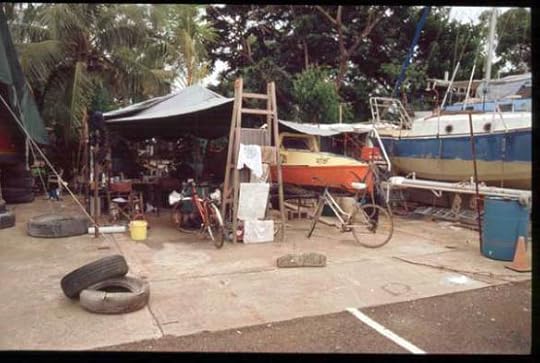

Expedition base camps are usually unremarkable places dedicated to the utility of adventure. Not so the Dinah Beach Cruising Yacht Association in Darwin, Australia with it’s overabundance of rare and exotic characters. For those waiting patiently for book 3 to be published (August 15), this excerpt is for you.

“How long have you been in Australia, Andy?”

Trimmed white beard, jug handle ears, and a gammy leg, the old Glaswegian had his shirt off, sporting a barrel stomach covered in a thick fleece of chest hair.

“Thirrrty-six years,” he replied happily.

“You’ve kept your accent well.”

“Och aye. Too tight even tae give that away!”

Belly shaking with laughter, he turned to climb the ladder to his single hull sailing boat, one of forty or so dilapidated vessels propped up on stilts in the Dinah Beach car park. Having been recently laid off and given the heave-ho by his wife of twenty-six years, Andy had split from Freemantle and made the club his home. Like Alcoholic Rodney in the catamaran opposite, he had absolutely no intention of going anywhere. Rent was cheap. The bar was within teetering distance, and sold the cheapest and coldest beer in town. It was the ideal retirement set-up. When I’d asked how much longer he thought it would be before his boat was ready to launch, Andy had pressed his whiskery face to mine, and hissed “Yearrrs!” with hearty optimism.

In the event the club lost patience with the liveaboards and forced them to expedite repairs and return their hulks to the sea, Andy had taken the precaution of drilling a hole through the bottom of his. The aperture was three inches in diametre, guaranteeing his craft never went near water again. And it had another use. At regular intervals throughout the evenings, we’d hear the Clink! Clink! Clink! of another beer can clattering into the dustbin below.

Lourdes and I had spent almost a week at our new residence, the thirty-by-fifteen-foot concrete pad next to Andy’s. Scavenging local materials, we’d erected a makeshift shelter of tarpaulins supported with driftwood, the corners anchored to car tyres weighted down with gravel. Moksha was rolled down the road on her cradle and given pride of place. What gear we’d managed to salvage was spread out on the ground to be inventoried, creating an obstacle course of pots, pans, charts, books, Tupperware containers, and other paraphernalia. At the back of the lot, behind Moksha, we pitched our tents between the piles of refuse left by previous occupants.

Such was our new expedition base camp.

It was also an office-cum-workshop. A stack of abandoned pallets served as a desk to order parts, write proposals for replacement gear, and fill out visa application forms. Another stack became a workbench to strip down the wind generator, service the pedal units, and resuscitate all manner of corroded electronics with the help of Australia’s answer to WD40, a potent engine spray called “Start Ya Bastard.” A local supporter, James Walker, loaned us deck chairs and a fridge to preserve food in the tropical heat. We cooked meals on camp stoves.

In spite of the open-air appeal, certain drawbacks of running a business alfresco quickly became apparent. The boatyard was hot, humid, and noisy—birds screeched in the nearby bushes, doves cooed, geese cackled and honked on the adjacent property. From dawn until dusk, our brains shuddered to the sound of sawing, hammering, and chiseling, and our ears convulsed to the whine of power tools. A two-foot-long monitor lizard, mottled brown with primrose yellow underside, shared our tent space, feeding off dead rats poisoned by Andy. And being the wet season, the skies opened like clockwork at two o’clock every afternoon, producing a river running through our camp. During these gully-washers, we dashed around shoring up the tarps, preventing reservoirs of rainwater from collecting on the roof, and doing whatever else we could do to keep our fragile little abode from collapsing.

To our fellow Dinah Beach denizens, the notion of pedalling a boat to East Timor, a shorter but otherwise comparable voyage to the club’s once infamous annual race to Ambon in the Maluku Islands, was ridiculous to the point of insulting. “But why?” they would ask, shaking their heads. Some, like Captain Seaweed, a sun-roasted Swede in a permanently affixed captain’s cap, even became irate—which struck me as odd. As a haven for those clearly ill-suited to society’s norms, giving sanctuary to ex-cons, cons on the run, and misfits in general who could otherwise expect to be rounded up if found wandering the streets, the Dinah Beach Cruising Yacht Association seemed to me the perfect home for the expedition.

A few, like Andy, “got” the concept of human power and offered to help. Leon from Darwin Ships Stores found cheap and used equipment to replace what had been trashed or stolen, including lifejackets from the Royal Australian Air Force. Kris, a shipwright who lived on a homemade junk anchored in the creek, replaced Moksha’s spirit guide with a turtle native to the waters we’d be pedalling through. The majority of people, however, treated us with thinly veiled skepticism. As we’d found in the past, it took the endorsement of the media to win over the Average Joe. A current affairs programme, ABC Stateline, ran a story, and suddenly we were worth speaking to.

I was in the club workshop one day, grinding off a pedal corroded to a crank arm, when I heard a voice behind me. “So vot heppens in der rof wezzer?”

It was Captain Seaweed, his breasts sagging and folds of skin hanging off his shoulders like an old bull elephant. He had just two teeth left in his head. His eyes were cerulean blue and sunk back into their sockets.

Without waiting for a reply, he added, “Ent vot ebout der waater?” He was the type that talked at you, not with you, delivering his sentences in the monotone machinegun chatter of Scandinavians.

I gave answers, but when I tried to explain our route, I was interrupted. “If ya goin’ up dare to Indonesia, oy’d floy der Shveedish flag oy would. Doze crazy facking baarstards, dey’ll shoot’ya if ya say you’re Hamerican hor Heenglish. Floy der Shveedish flag. Dey never done nothin’ to nowan!”

He had a point, albeit a paranoid one. Ninety-eight percent of Indonesia’s 220 million inhabitants were Muslim, the highest percentage of any country in the world, and Islam produced more than its fair share of fanatics. A number of these, members of the radical Jemaah Islamiyah group, had recently been turfed out of Ambon and Maluku following bouts of religious cleansing between Christian and Muslim communities. It was this same looney tunes outfit that had slaughtered two hundred and two people, including one hundred and fifty two foreign nationals, in the 2002 Bali bombings.

From then on Captain Seaweed became one of our biggest allies. An accomplished sailor, he was a wealth of information on the hazards of the Beagle Gulf, the body of water immediately north of Darwin. Most crucially, he photocopied detailed charts of the Apsley Straits, the narrow sea passage between Bathurst and Melvin Islands, which offered the best route to clear the eastern edge of Timor to reach Dili.

* * *

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Expedition Base Camp Darwin Style appeared first on Jason Lewis.

April 12, 2015

Lake Nasser Arrest – Part 5

Concluding excerpt from To the Brink , published August of this year. Read part one , two , three, and four.

Of course, I wasn’t out of the woods yet. Entering Egypt illegally was still a serious enough offence to get me slung out of the country, but at least the paperwork miraculously catching up to me staved off the grim possibility of rotting away in an Egyptian cell. And with the arrival of the fax, Major Hassan was a changed man—perhaps because his own neck was also off the block. Gone was the icy demeanour. He began laughing and joking, asking me about my family, and telling me about his:

“Eef you come Cairo, ees my mobile number. You meet my wife and cheeldren!”

Escorted by two orderlies, I was sent off to complete formalities with five other security agencies: Public Security, National Guard, State Security Service, Tourism and Antiquities Police, and the army. The whole process took seven hours. Finally, at one thirty in the morning, I was ushered back ino the Mubahath el-Dawla compound.

“I have good fren Aswan immigration,” the major said, rising wearily from behind his desk. He was drunk with fatigue, as was I. “My men will take you now, while still dark.”

His contact would be standing by the side of the road leading into Aswan, waiting to stamp my passport with an entry stamp “borrowed” from his office. Major Hassan didn’t have to do this, I realized. It was a personal favour. Stirred with gratitude, I fossicked in my pile of gear and presented him with the Nepalese kukri.

Observing ritual, the intelligence officer refused.

“Please,” I insisted, pushing the knife towards him. “I want you to have it, major. If it wasn’t for you, I’d have to backtrack to India.”

As per Arab custom, the major was obliged to reciprocate. He reached for the camel whip on his desk. “Dis here, very useful.” He pointed to a small indentation in the end of the lash. “Bedouin put poison. Keel enemy more quickly.”

“Very handy,” I agreed, thinking of some of the more obnoxious Ethiopian or Tibetan children I could put it to good use on if I ever found myself back in those countries.

Then the major shook my hand, smiled, and said, “I weesh we could haff meet under better circumstances, Meester Jason. But go now, and feenish dis great joorney.”

END

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Lake Nasser Arrest – Part 5 appeared first on Jason Lewis.

February 22, 2015

Lake Nasser Arrest – part 4

Part four of a five-part excerpt taken from To the Brink , the concluding volume of my circumnavigation trilogy, published April of this year. Read part one, two, and three.

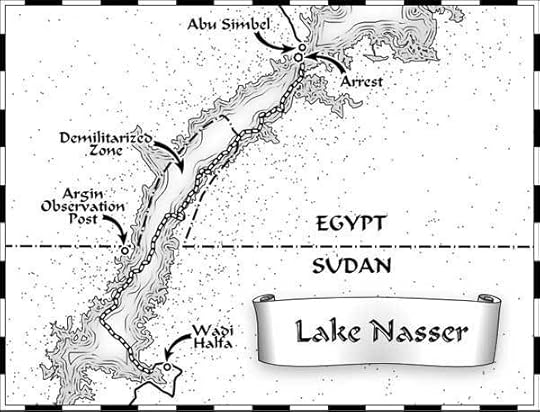

It was time to come clean about my intent to cross the border illegally. I explained about the expedition, and my plan to kayak Lake Nasser at night. At the end of the confession, I motioned to the map case on the major’s desk, and said, “Can I show you something?”

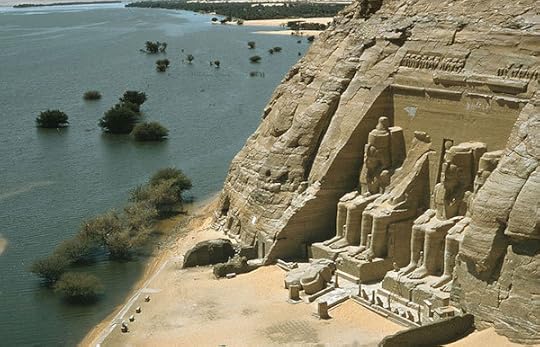

I pulled out a laminated letter and offered it to him. Glancing at the letterhead, Major Hassan grunted, “Ah, the UNESCO.” Written in 1994 by the then Director General, Frederico Mayor, the letter appealed for people, organizations, and governments to assist the expedition on its way around the world. This was my ace in the hole, the ultimate Get Out of Jail Free card. UNESCO had been instrumental in saving two temples built in thirteenth century BCE by Ramses II, relocating them stone by stone to Abu Simbel, before the Nile was flooded to form Lake Nasser.

“But dis name.” The major pointed to the first paragraph. “Pe-dal-for-the-Pla-net. Is not the name you say.”

This was true. I’d given name Expedition 360. “But I can explain,” I pleaded. “You see, we changed the name of the expedition in 1999—”

But the major wasn’t listening. He was back to yelling at his phones.

He left the room a little while later, leaving me in the care of the list-making orderly nursing his bandaged thumb. Perhaps still aggrieved at his injury, the man sidled over to where I was sitting, raised a hooked finger to my face, and whispered, “Jew spy!” He crossed his wrists, the sign for imprisonment, and bared a gold-capped tooth at me. “Forrrteee yerrr!”

Tens of thousands of innocent people languished in jails around the world, forgotten victims of politic crossfire, attempted extortion, or simply mistaken identity. If you were a big enough fish to come up on the political radar screen, either thanks to friends in high places, or a media campaign launched on one’s behalf, there was reason to believe your government would get involved. Otherwise, that’s where you would stay, potentially for the rest of your life. I imagined the response I could expect from the British Consulate in Cairo on hearing of my arrest, especially after warning me not to cross the lake without permission. Serves the idiot bloody well right!

With the prospect of spending the rest of my natural life in prison, all feeling drained from my body. My disbelieving gaze came to rest on a photograph propped on the bookcase beside the major’s desk. A serious looking boy and a smiling girl stared back, the major’s children, I guessed, and my thoughts turned to my own family, and to a far country. Being summer, the days would be long, stretching well into evening. My parents would be outside on the lawn, enjoying the last of the sun before it dipped behind the towering beach trees to the west. Trilling birds would be settling in for the night, roosting in the hawthorn bushes. The air would be filled with the aroma of freshly cut grass from nearby hayfields, blending with the lingering trace of honeysuckle blossom. In the local Spyway Inn, patrons would be lounging in the beer garden, quietly sozzled on IPA, the rolling green flanks of Eggardon Hill peppered with puff pastry sheep rising up behind.

Will I ever set eyes on any of this again? I thought miserably.

On the afternoon of the second day, some thirty-six hours after being seized by the fishermen, another military official entered the room. He was exceptional in that he wore uniform; in all other respects, he looked like the orderlies—pinched, hawk-like, dead hamster moustache, and smoking feverishly. The major brought him up to speed on the situation, gabbling in Arabic and going over the lists of gear. It was at this point that I twigged what was happening. I was about to be handed over to a different branch of the Egyptian military, and transferred to another detention centre, presumably in Cairo, for further interrogation.

Sitting there, contemplating this new turn of events, I heard a fax machine in a nearby room whir to life. The same orderly who’d been plying the major with cups of tea walked in holding two sheets of paper. Major Hassan took the dispatch and began reading it slowly. Every few seconds, he glanced up and eyed me through the cigarette smoke. My pulse quickened. Was this more bad news?

“Meester Jason.” He twirled the pages at me. “Ees from Cairo. You ask permission to cross Lake Nasser?”

I nodded. “Yes. Six weeks ago. But I heard nothing back.”

For the first time since the whole ordeal began, something approximating a smile took shape on the major’s face. “Yes, well, never mind. Application ees approved. Seems you tell trooth.”

To be concluded …

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Lake Nasser Arrest – part 4 appeared first on Jason Lewis.

February 11, 2015

Lake Nasser Arrest – part 3

Part three of a five-part excerpt taken from To the Brink , the concluding volume of my circumnavigation trilogy, published April of this year. Read part one and two.

A flunky I hadn’t seen before appeared, carrying a sheaf of paperwork and a mug of tea in a saucer. He placed them in front of the major, who was now speaking rapidly into a telephone, one of several that lined his desk. This is bad, I said to myself. The inventorying of equipment continued. Lists were made. Then yet more lists. The orderly going through my gear handed the major a burgundy booklet he’d found in my waterproof money belt. This was a back up passport, one free of Israeli stamps that would better my chances of getting into Syria.

Still barking at the phone, the major took the passport and placed it with the other. How would I explain this?

Hours passed. Phones rang. Major Hassan had up to three handsets on the go at once, working the phones like a telemarketer. Who was he talking to? I lost all track of time. During lulls in the interrogation, I found myself nodding off, having barely slept in three days. Suddenly, there was a commotion behind me. The orderly had cut himself unsheathing my kukri knife, slicing this thumb to the bone. Needing an excuse to ingratiate myself in what appeared to be increasingly dire circumstances, I dressed and bandaged the wound with supplies from my first aid kit.

I reckoned that I’d been sitting in the same chair for around eighteen hours when an orderly brought me a glass of water, and escorted me to a bunkhouse. I slept for an hour. Then I was roused for more questioning.

Back in the office, an exhausted Major Hassan was still working the phones. Cups of cold coffee cluttered his desk. A marble ashtray overflowed with cigarette ends. My cameras and GPS were in a row in front of him.

Seeing me, he signaled for me to sit, and then swivelled the LCD screen of the camcorder. The display was dark, but I could hear a voice—my voice—whispering to the camera. I was describing crossing the border, and congratulating myself on avoiding detection. “I’m now heading north towards Aswan,” the voice was saying. “So, I really, really hope the Egyptian security forces don’t see me.”

The lights of Argin, the border surveillance post, were clearly visible in the background. I’d even filmed the GPS coordinates of the twenty-second parallel to verify my circumnavigation route. The dumb tourist card was played out. Major Hassan began fast forwarding through the footage.

“Where?” He stopped to play a section. “Sudan or Egypt?”

A procession of white-robed boys was trooping into shot: the goatherds who’d stumbled on my position the first day.

“Sudan. I think.”

He listened to their conversation. “No. Massri. Egypt boyz. Dey say you make reconnaissance.”

I noticed my Russian topographic maps were spread out on an adjacent table. Covering the entire southwest-to-northeast-aligned lake to Aswan, the maps took in a wide swath of southern Egypt, including the sensitive border region.

Sher’s kayak had also drawn attention.

“We use dis for special operations,” the major said, nodding at the boat parked along the back wall. He handed me my GPS. “Now. Show me.”

No more “Pleases,” I noticed. No more “Never minds.”

I pressed the power button and the waypoints shimmered into view, revealing my precise route up the lake.

Meanwhile, more equipment lists were being made. Then more questions:

“Why are you here in Egypt?”

“What are you looking for?”

And again: “You work for … who?”

Several Arab countries, including Syria, automatically refuse entry to anyone with an Israeli stamp in their passport.

To be continued …

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Lake Nasser Arrest – part 3 appeared first on Jason Lewis.

January 29, 2015

Lake Nasser Arrest – part 2

Part two of a five-part excerpt taken from To the Brink , the concluding volume of my circumnavigation trilogy, published April of this year. Click here for part one.

Major Hassan shook his head in disbelief. This idiot tourist had somehow strayed across the border, the border it was his job to prevent anyone from going anywhere near. He hammered on his keyboard and read from the screen, “How did you cross the border?”

“No one stopped me.” I replied truthfully, although I chose not to mention that I’d paddled at night. “But I am still confused”—I reached forward and showed him my map—“exactly where the border is.”

Using the ring finger of his left hand, which I noticed bore a gold wedding band, he traced the twenty-second parallel. “Up from here.” He wagged another finger. “Is forbidden.”

“And where are we now?”

His finger travelled the forty miles north to Abu Simbel.

“Oh, I see.” I laughed nervously, pretending to only now comprehend. “I suppose that means I’m in trouble, no? I’m just glad you didn’t shoot me!”

Major Hassan said nothing. No smile. No laughter. He furrowed his brow, took a deep drag on his cigarette, and went back to scrutinizing my passport. In a corner of the room, one of his henchmen was going through my gear, pulling out the contents of the dry bags and placing them in different piles. Electronics was already the biggest.

The major glanced over at the growing mound of gadgetry: laptop, GPS, satellite phone, EPIRB, video camera, cell phone, RBGAN satellite modem, digital still camera, solar panels, memory cards, video cassettes, power adaptors, leads, extra batteries, and two compasses—one handheld, the other from my cockpit. He pointed and rattled off something in Arabic, whereupon the orderly retrieved the laptop-sized satellite terminal I used to send video footage back to the expedition website.

“What this?” he asked.

I considered trying to pass it off as a battery pack, but the compass embedded in the front cover would give it away. I told him the truth.

The major had been tactful and diplomatic at first, introducing himself politely (“Hello, my nem ees Major Hassan”) and asking harmless questions. His demeanor was starting to change. He stared at me through the swirling galaxies of blue silvery smoke, his eyes narrowed to reptilian slits. “I do not be leaf your story,” he said, fingered the whip ominously.

“What part of it?” I asked.

“Any of it!” The major leaned forward and pointed to the last page of my passport. “Your family name Levi?”

“No, Lewis.”

“You work for … who?”

I shook my head. I was beginning to see where this was going. In its written form, Lewis bore a loose resemblance to the Hebrew name of Levi. Egyptians hated Jews even more than the Sudanese, a long-standing hostility stretching back to pharonic times that had been more recently inflammed by repeated military defeats at the hands of the Israelis since 1948. “No, I don’t work for anybody,” I protested.

The major tightened his jaw in irritation, and nodded at the pile of electronics. “Then, what these. I ask you again, who you work for?”

To be continued …

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Lake Nasser Arrest – part 2 appeared first on Jason Lewis.

January 8, 2015

Lake Nasser Arrest – part 1

The following is an account of my arrest and subsequent interrogation by Egyptian security forces after paddling a kayak illegally across Lake Nasser from Sudan in 2007. It is the first of a five-part excerpt taken from To the Brink, the concluding volume of my circumnavigation trilogy, published April of this year.

“What contree, you?”

I blinked at the mesmerizing eddies of smoke swirling towards the fluorescent ceiling tube. “UK,” I replied. “I’m English.”

Mid-forties, hair thinning and cheeks pitted, my interrogator sat behind a large mahogany desk, cigarette smoldering between his fingers, leafing through my passport. He looked coldly efficient in his narrow framed glasses, yet so far the major had been courteous, disproving Mazar’s assurances of being beaten on sight by the Egyptian military. Perhaps he was just treading carefully? Egyptians were paranoid about their tourism industry. The curtains were drawn and the air conditioning turned up full blast. For the first time since crossing the Himalayas, I was freezing.

Three hours earlier, a white motorboat had pulled up on the beach where I lay face down, being used as a mattress by the fishermen. Major Hassan and two henchmen jumped out, revolvers drawn. The fat skipper immediately began waving his pudgy hands and yammering, boasting of his ruse. Bastard will no doubt be rewarded handsomely for this, I thought bitterly. The henchmen bundled me into the launch along with my gear, and after a short ride down the coast, we disembarked in a little harbour below the Mubahath el-Dawla detention centre, General Directorate for State Security Investigations. It was the same inlet I’d paddled into earlier under cover of darkness, where the night watchman had shone the flashlight.

http://www.jasonexplorer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/lake_nasser_capture-Wi-Fi.m4v

It was then I noticed the camel whip coiled on the major’s desk. How many prisoners had been coerced into spilling their guts by this instrument of torture, I wondered? Putting my passport down, the intelligent officer began fiddling with the mouse on his desktop computer. His English was better than my Arabic, but this wasn’t saying much. For many of the questions, he had to resort to using a Windows translation program.

Without looking up, he said, “So, going … round Egypt?”

This is what I’d communicated to the fishermen: that I was sightseeing. The problem with this story was that my passport contained neither an entry stamp for Egypt, nor an exit stamp from Sudan. All I had was an expired Sudanese visa, leaving me in political limbo. The major would find all this out in due course. My only hope in the meantime was to play the dumb tourist card.

“Yeah, just paddling around. I think I might have got lost, though. Is this Egypt or Sudan?”

He stared at me, his eyebrows raised. “You choking?”

“No, no, I’m not.”

“Dis Egypt.”

“I thought it was Sudan.”

“No, no!” He stabbed his desk with a finger. “Egypt!”

“Oh dear, then I really am lost.”

He turned his attention back to my passport. “Where is—” And he made a stamping motion with his fist, a reference to the missing visa and entry stamp for Egypt.

I took a deep breath. “Well, I was in Sudan, doing some kayaking around the lake—for tourism—and I must have gone too far north. So, this is definitely not Sudan?” I winced.

To be continued …

All Rights Reserved – © 2015 Jason Lewis

The post Lake Nasser Arrest – part 1 appeared first on Jason Lewis.

December 14, 2014

Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part three

Third and concluding excerpt (read part one and two) from To the Brink, published April 2015:

Later that day, we paddled to the Muslim village of Pota. April and I recounted our experience to the village elders.

“Sihir!” one of them hissed. Witchcraft.

More than a hundred people were crowded around us, the faces of the women painted ghoulishly with the white paste Indonesians used for skin bleaching.[1] The atmosphere had been excitable as we set up camp: lots of laughter and whooping, and “Hello Meester! Hello Meesees!” When the elders arrived, the crowd regained its composure.

“Dukun santet,” said another elder. Black shaman. This was Haji, a smiling octogenarian in a blue shirt, purple lava-lava, and Peci, a black fez hat. “Indonesia beeple superstitious,” he continued. “You break promise in village? You make disrespect? They revenge with”—he nodded sagely and wagged a finger—“dukun santet.”

Translating was his son, a pint-sized forty-year-old with the flitting eyes of a blackbird. He went on to explain how someone seeking retribution could retain the services of a black shaman, a witch. First, you obtained a strand of hair from the intended victim’s head, or something they’d been standing on. Then the dukun santet would concoct the spell. The customer had a variety of options to choose from. Fire was one; if you lit a match or a cigarette and pointed it at your enemy’s house, within a few days the building was sure to burn to the ground. Another was to cause their crops to fail, or livestock to die.

“Or snake,” said Haji, raising another finger. Like fire, snakes could be sent long distance, and, after eliminating the target, retrieved the same way. The most crucial ingredient in any of the methods used was for the client to believe unequivocally in the spell they had commissioned. Otherwise, it wouldn’t work. This struck me as an ingenious escape clause for the shaman. If the magic failed—which, presumably, it always did, unless the victim happened to croak anyway—the fault ultimately lay in the client’s lack of conviction, avoiding the irksome business of having to fork over a refund.

Being the target of a grudge wasn’t entirely beyond the realms of possibility. Lourdes and I had had our public spat in Riung, and perhaps I’d further offended the owners of the losmen by refusing to pay full price for a room just for sleeping outside on the grass. But the notion of black magic at play, albeit entertaining, was absurd.

“What a load of mumbo-jumbo,” I whispered to April.

It wasn’t until four days later in Labuan Bajo, another tin-roofed town with an open sewer policy, that the truth was finally revealed. According to the “Fun Facts” of the Sea World website I googled in the town’s Internet café, sea snakes were attracted to light. That explained so many of them entering our camp. The snakes had been drawn like moths to our headlamps.

When I told April, she seemed relieved. After all, it solved a mystery that had been playing on both our minds and had us both badly spooked. Then her face fell, clouding with uncertainty.

“Okay,” she said softly. “But where did they disappear to in the night, then?”

* * *

[1] In Indonesia, skin lightening is promoted as an “opportunity enhancer” and social indicator of wealth, status, and beauty by a multi-million-dollar cosmetics industry. I’d found the same to be in Central America, where darker skin is considered by the social elite to be inferior, even ugly.

All Rights Reserved – © 2014 Jason Lewis

The post Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part three appeared first on Jason Lewis.

November 6, 2014

Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part three

Third and concluding excerpt (read part one and two) from To the Brink, published April 2015:

Later that day, we paddled to the Muslim village of Pota. April and I recounted our experience to the village elders.

“Sihir!” one of them hissed. Witchcraft.

More than a hundred people were crowded around us, the faces of the women painted ghoulishly with the white paste Indonesians used for skin bleaching.[1] The atmosphere had been excitable as we set up camp: lots of laughter and whooping, and “Hello Meester! Hello Meesees!” When the elders arrived, the crowd regained its composure.

“Dukun santet,” said another elder. Black shaman. This was Haji, a smiling octogenarian in a blue shirt, purple lava-lava, and Peci, a black fez hat. “Indonesia beeple superstitious,” he continued. “You break promise in village? You make disrespect? They revenge with”—he nodded sagely and wagged a finger—“dukun santet.”

Translating was his son, a pint-sized forty-year-old with the flitting eyes of a blackbird. He went on to explain how someone seeking retribution could retain the services of a black shaman, a witch. First, you obtained a strand of hair from the intended victim’s head, or something they’d been standing on. Then the dukun santet would concoct the spell. The customer had a variety of options to choose from. Fire was one; if you lit a match or a cigarette and pointed it at your enemy’s house, within a few days the building was sure to burn to the ground. Another was to cause their crops to fail, or livestock to die.

“Or snake,” said Haji, raising another finger. Like fire, snakes could be sent long distance, and, after eliminating the target, retrieved the same way. The most crucial ingredient in any of the methods used was for the client to believe unequivocally in the spell they had commissioned. Otherwise, it wouldn’t work. This struck me as an ingenious escape clause for the shaman. If the magic failed—which, presumably, it always did, unless the victim happened to croak anyway—the fault ultimately lay in the client’s lack of conviction, avoiding the irksome business of having to fork over a refund.

Being the target of a grudge wasn’t entirely beyond the realms of possibility. Lourdes and I had had our public spat in Riung, and perhaps I’d further offended the owners of the losmen by refusing to pay full price for a room just for sleeping outside on the grass. But the notion of black magic at play, albeit entertaining, was absurd.

“What a load of mumbo-jumbo,” I whispered to April.

It wasn’t until four days later in Labuan Bajo, another tin-roofed town with an open sewer policy, that the truth was finally revealed. According to the “Fun Facts” of the Sea World website I googled in the town’s Internet café, sea snakes were attracted to light. That explained so many of them entering our camp. The snakes had been drawn like moths to our headlamps.

When I told April, she seemed relieved. After all, it solved a mystery that had been playing on both our minds and had us both badly spooked. Then her face fell, clouding with uncertainty.

“Okay,” she said softly. “But where did they disappear to in the night, then?”

* * *

[1] In Indonesia, skin lightening is promoted as an “opportunity enhancer” and social indicator of wealth, status, and beauty by a multi-million-dollar cosmetics industry. I’d found the same to be in Central America, where darker skin is considered by the social elite to be inferior, even ugly.

All Rights Reserved – © 2014 Jason Lewis

The post Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part three appeared first on Jason Lewis.

October 25, 2014

Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part two

The second of a three-part excerpt (read part one here) from To the Brink, published early 2015, in which the Expedition 360 team encounter sea snakes and black magic on a remote island off the north coast of Flores, Indonesia:

A third snake suddenly appeared. I grabbed the video camera and began filming. “What is going on?” I said. Snakes gave me the same heebie-jeebies as spiders. “Why all these snakes?”

It didn’t make sense. At the first sight of a human, virtually every wild animal I’d ever come across had turned tail and scarpered, millennia of extermination rendering them wary of engaging Homo sapiens. So why were these snakes taking such an interest in us?

“Third snake over here,” I narrated to the camera. “Fourth snake over there.” We were surrounded. Our enchanted little island was becoming less so by the minute.

“No wonder this place is uninhabited,” remarked April.

We found ourselves standing back to back in a defensive position. The snake in my viewfinder had turned away from the water and was now gliding up the shingle towards us.

“Watch to your left!” April warned.

“I know, got it. This is starting to freak me out.”

“Yeah, I’ve got a bit of prickly skin. This doesn’t make me feel comfortable at all.”

I switched the camera to night vision mode to better track the snakes in the darkness.

“Just keep an eye on that one,” said April, pointing to a length of black hosepipe slithering off the edge of my screen.

“Yup. There’s two of them right here,” I replied. “They’re going for the boat.”

It was a nightmare. The prospect of trying to extract lethal snakes from our cockpits made my head reel.

“Actually,” April said, “they can move a little quicker than you think.”

“Yeah, they’re beginning to wake up.”

The two heading for the boat altered course and made straight for us, crossing and re-crossing each other’s paths, heads raised, weaving back and forth.

“It’s like they’re working as a team.” I could hear the desperation rising in my voice. “Hunting us in a pair.”

“I know it!”

April and I began inching down to the water’s edge to make a last stand. With our backs to the sea, we had less area to defend. This was assuming the snakes didn’t take to the water, quite possible considering they were amphibious.

“Okay, here comes one,” said April, pointing to the nearest, now a few feet away.

“Son of a bitch!”

“What do we do, kill them?”

As a vegetarian of nine years, my rule of thumb was not to kill or eat anything that shat or had a face—both indicators of higher intelligence than, say, a potato. But the situation was getting out of hand. We had no antivenom with us. If either of us was bitten, it was a three-day journey to the nearest hospital at Ende.

“I’d say we’re getting to that point,” I conceded.

“Watch! Watch!” April shouted. Even backing away, the snakes were gaining on us.

I reached for a stout piece of timber from the fire and dispatched the lead snake, crushing its head in a cloud of sparks.

“Where’s its buddy?”

“Here he comes.”

“Very sorry, Mister Snake.” Again, I swung the timber. The snake convulsed into a pretzel, then was still.

The others were nowhere to be seen. Treading carefully, I picked up the two carcasses and threw them under a tree above the high tide mark. If one of us was indeed bitten during the night, at least one of the snakes would accompany us to Ende to be identified for the right antivenom—assuming the victim survived that long, of course. We then slipped the covers over the cockpits, and retreated to the safety of the tent.

In the morning, April described the dreams she’d had during the night. Snakes dominated all of them: “Hanging off my legs, gnawing at my flesh.” It was the Lariam talking, the same lucid dreaming as on the Coral Sea voyage.

Gingerly, we crawled out of the tent, taking care not to disturb any visitors that might have crept under the groundsheet for warmth in the night. I started a fire for tea, while April took a walk down the beach. A minute later, she was back, her face drained of colour.

“They’re gone,” she whispered.

“What are?”

“The snakes.”

For the first time I noticed a dead tree partially submerged in the shallows, its grey skeletal limbs poking out of the water like the ribcage of an elephant.

“That tree,” I said. “I don’t remember that tree being there when we came in yesterday.”

I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. April, too, looked rattled.

“Maybe they got washed out to sea?” she said.

I shook my head. “Impossible. It’s only neap tides, and I threw them way above the high tide mark.”

To be concluded in part three, posted Wednesday Oct 29.

All Rights Reserved – © 2014 Jason Lewis

The post Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part two appeared first on Jason Lewis.

October 17, 2014

Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part one

In August of 2005, April and I found ourselves camping on an idyllic islet off the north coast of Flores, Indonesia, during a 7-month kayaking expedition from East Timor to Singapore. An experience that first night on the island left us badly shaken, and our skepticism of black magic and blind acceptance of Western scientific thought both in doubt. This is the first of a three-part excerpt from my upcoming book, To the Brink (published April 1, 2015).

Ahead of us was the most beautiful islet either of us had ever seen, a tiny jut of wind-swept grass surrounded by pristine coral beaches. The whole thing measured less than a hundred by three hundred feet, an unsullied pearl set in the balmy waters of the Flores Sea. We made a circumnavigation, looking for signs of human habitation. There were none.

“Looks perfect,” I hollered from the rear cockpit.

After all the confrontation of the last weeks, it would be a quiet spot to decompress for a few days and not have to deal with anyone other than each other. Pulling the Libra ashore, April and I gathered driftwood to boil a pan of water, then clambered to the highest point, a limestone bluff with a three-sixty-degree panorama, and sat drinking our evening tea.

“And all is right with the world again,” I murmured happily, gazing at the twenty-two other islands scattered like gems over a bed of blue velvet.

April smiled. “Yes. This is paradise.”

We sat there until dark. Rising to my feet, I heard something in the wind. “Did you hear that?” I said.

April nodded. “Yes. Like human voices.”

“Almost like laughing.”

“Yeah. Weird.”

We scoured the island. It didn’t take long. Were the voices coming from Riung? This seemed unlikely. Riung was eight miles away and the wind was blowing in the wrong direction.

Back in camp, we resurrected the fire and boiled some noodles.

“Maybe we can sleep outside tonight?” April suggested. “There don’t seem to be any mosquitoes.”

Nor would there be a problem with security, another reason we usually zipped ourselves in the tent every night, our passports and money safely wedged under our heads as we slept.

As we sat in the firelight, taking it in turns spooning from the pan, I watched a column of ants carry a moth to some subterranean doom. The insect was still very much alive, flailing its legs and fluttering its wings. Seeing its futile efforts, I thought of frenzied Lilliputian hordes overcoming Gulliver, and a strange sense of foreboding swept through me.

After dinner, I fired up the GPS, and was about to walk down to the water’s edge for a clear signal when something moved at my feet. White underbelly with black and white-banded flanks, the five-foot snake was identical to one I’d seen while swimming in the Solomons. I pointed my headlamp at the flattened tail. “Banded sea krait.”

“Jeepers,” said April. “Are they venomous?”

“Sea snakes? Ten times more so than a rattlesnake.”

Flicking its tongue, the serpent slithered past and disappeared into the fleshy-leafed vegetation behind the Libra.

April breathed a sigh of relief. “Well, looks like he’s not too interested.”

“Rather knocks the idea of sleeping outside on the head, though, doesn’t it?” I said.

After helping April set up the tent, I turned my attention back to the GPS. Every 24 hours, I would send our latitude and longitude position to my father as part of a date-time group in a satellite text message. The army protocol had become a nightly ritual, ensuring that if anything went wrong, someone would at least know where to start looking for us.

I heard a shout. “Oh Jeez! There’s another.” A snake with the same black and white markings was approaching from the opposite direction.

April laughed nervously. “What we don’t know, of course, is what they eat to get so big.”

“And then what eats the snakes,” I said.

“Komodo dragons?”

This wasn’t as far-fetched as it sounded. The same species of giant monitor lizard that inhabited the islands between Flores and Sumbawa a mere hundred miles to the west had been sighted around Riung. Our little island was too small to sustain a permanent population, but the dragons were strong swimmers and known to visit other islands in search of food.

To be continued. Part two will be published Saturday October 15.

All Rights Reserved – © 2014 Jason Lewis

The post Black Magic and Sea Snakes – part one appeared first on Jason Lewis.