Jason Lewis's Blog, page 8

August 15, 2012

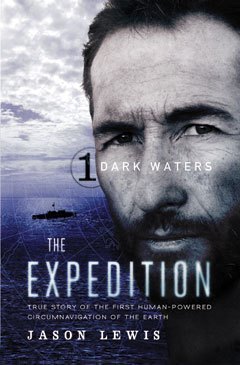

Dark Waters ebook launched in North America

Marking time in the event of electrical failure

Dark Waters, chronicling the first human-powered circumnavigation of the Earth, now available for download in US & Canada on the following devices and platforms:

Amazon Kindle

Barnes & Noble Nook

Apple iTunes

Google Play

Kobo

Includes 26 color photographs, high resolution maps and blowup plans of Moksha, the pedal-powered boat that crossed the Atlantic and Pacific.

Last Sight of Land – Atlantic Departure

August 8, 2012

Fundraising Casualties – the expedition #adventure #travel book excerpt 10

The London Boat Show, January 1994

Our planned departure date of May 1 came and went. Every day we postponed for lack of sponsorship was one less day to bike to Vladivostok in easternmost Russia, and launch Moksha before the Northern Hemisphere winter set in. Not thrilled about the prospect of freezing to death in Siberia, we decided to fix a cut-off date. If a title sponsor hadn’t stepped up to the plate by June 1, we would either postpone until the following spring, or abandon the effort entirely. While the latter seemed almost unthinkable after the thousands of man-hours already invested, the former posed an equally dismal prospect: another soul-destroying year surviving on social security handouts and living in derelict housing.

They were desperate times, and desperate times can lead to reckless measures. Moksha still needed to be furnished with hundreds of bits of incidental gear – cups, plates, cutlery, saucepans, a kettle, food storage containers, batteries, a poo bucket for inclement weather, sponges for bailing, a handheld foghorn, fishing line, hooks – all of which cost money we didn’t have. Taking matters into my own hands, I tried legging it from an East London marine supplier clutching a rubber bucket, two sponges, and a scrubbing brush. I got about twenty yards before being rugby tackled by a security guard outside Woolworths, bucket and sponges bouncing into the road, and a pair of old biddies looking on in disgust.

I was arrested and hauled off to Plaistow Police Station to be formally charged. I’d hit rock bottom, and braced myself for the worst. But after a stint in a holding cell, the booking officer became so intrigued by how a two pound fifty bucket to crap in was integral to the success of a human-powered circumnavigation of the planet, he let me go with a caution. My real punishment was yet to come, being read the riot act by Steve, justifiably livid at the integrity of the project so nearly compromised.

Sensing the whole thing was about to die on its feet, our families, and Steve’s girlfriend, Maria, came to the rescue. The loan, repayable when sponsorship eventually materialized, was enough to pay off Hugo, finish Moksha’s construction, and at least get us on our way. In many ways they had every reason not to. At the London Boat Show in January, when Moksha was brought in as a special feature by the show’s organizer, numerous whiskery old sailing buffs had walked away shaking their heads after examining Moksha. One even declared the circumnavigation attempt to be one of the most sure-fire ways of committing suicide he’d ever seen.

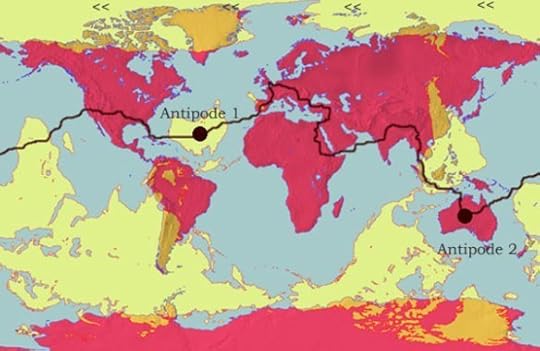

Even then, we still didn’t have near enough money for the entire trip. Faced with running out of funds in Eastern Europe, we changed the circumnavigation to a west-about route: biking south through France, Spain, and Portugal, before launching Moksha off the Algarve Coast and crossing the Atlantic to North America. Being a relatively young nation where the pioneering spirit was still celebrated, the US would hopefully offer a broader bite at the sponsorship apple. Properly financed, we could then pedal across the Pacific to Australia, aiming for a sister point to one already reached on the Atlantic. By hitting at least one pair of antipodes, defined as two points diametrically opposite each other on the Earth’s surface, the expedition would meet the criteria for true circumnavigation laid out in 1971 by Norris McWhirter, founding editor of Guinness Book of Records: crossing all lines of longitude, the equator at least twice, and covering a minimum distance of 21,600 nautical miles, a distance equivalent to the circumference of the equator, thereby coming as close as possible to the geographic ideal of a great circle.

The route change produced another casualty, however. Still broke, having to sell his power tools to buy food, and dossing on the floor of an old water tower in Putney, Chris’s continuing incentive to work on Moksha hinged around his promised role as support team driver. The revised route meant smooth roads as far as San Francisco. A full-on support team was no longer needed.

Another acrimonious falling-out ensued. Feeling he’d been used, Chris blew his top and stormed off the project. Steve took the news badly, angry that Chris should “abandon ship” before Moksha was fully finished. Although completed to design specifications, myriad small tasks still needed doing: painting, drilling holes for radio antennas, installing solar panels, sewing canvas compartment covers, fabricating a bed for the sleeping compartment, and so on.

I felt caught in the middle. In the overall interests of the expedition, my loyalty to Steve remained firm. Privately, however, as with Hugo, I didn’t always agree with his methods, especially when it came to handling people whose goodwill and continued patronage we so relied upon, broke as we were. Those who fell by the wayside, claiming they’d been burnt, left a distinctly bad taste in the mouth.

Then again, Steve’s single-mindedness and determination were what got the whole thing off the ground in the first place.

* * *

Expedition 360 route showing antipodes, criteria for true circumnavigation

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

August 4, 2012

The Expedition book, Dark Waters, Launched in US and Canada!

Very proud to announce North American print publication of Dark Waters, first in The Expedition trilogy chronicling the first human-powered circumnavigation of the Earth.

Dark Waters (The Expedition trilogy, book one)

Discounted to $11.50 in the US on Amazon. Also available on BN.com or signed copies direct from the publisher.

Indigo are carrying it in Canada for $12.96 CAN.

Ebook version out very soon.

DESCRIPTION: He survived a terrifying crocodile attack off Australia’s Queensland coast, blood poisoning in the middle of the Pacific, malaria in Indonesia and China, and acute mountain sickness in the Himalayas. He was hit by a car and left for dead with two broken legs in Colorado, and incarcerated for espionage on the Sudan-Egypt border.

The first in a thrilling adventure trilogy, Dark Waters charts one of the longest, most gruelling, yet uplifting and at times irreverently funny journeys in history, circling the world using just the power of the human body, hailed by the London Sunday Times as “The last great first for circumnavigation.”

But it was more than just a physical challenge. Prompted by what scientists have dubbed the “perfect storm” as the global population soars to 8.3 billion by 2030, adventurer Jason Lewis used The Expedition to reach out to thousands of schoolchildren, calling attention to our interconnectedness and shared responsibility of an inhabitable Earth for future generations.

THANKS: Including the circumnavigation itself, the expedition project is now 20 years in the making. Thousands of people have contributed in myriad ways to make it happen. Special thanks for bringing this story to the written page go to Kenny Brown (photos), Tammie Stevens (editor), Rob Antonishen (maps), and Anthony DiMatteo (editing). Thanks also to all who read and gave feedback to early drafts.

July 31, 2012

Sea Trials Farce – the expedition #adventure #travel book excerpt 9

Leaving Salcombe marina for three days of “sea trials”

The following afternoon we re-launched Moksha into Salcombe harbour, loaded her with three days of provisions, and headed for the open sea – centreboard firmly in place this time.

For Steve, this was to be his first night at sea, ever. He had more experience of overland travel having ridden a bicycle more than a mile since leaving school. I had more experience of boats having actually been in one.

After pedalling for what seemed an eternity, the dark outline of Bolt Head refused to get any closer. We switched. Within minutes, Steve’s face was clenched in similar frustration. It was mind-numbing stuff. We exchanged glances, and cracked up laughing.

“Fucking boring isn’t it.”

“To put it mildly.”

“Look,” I said, furthering our mutual cause. “We know this is going to be a nightmare once we get out on the Atlantic proper. So why prolong the agony?”

Steve nodded. “It’s opening time in half an hour, too.”

More sniggering, and by eight o’clock, thanks mainly to the incoming tide, we were back in the Kings Arms, warming up next to the fire with Stuart and Kenny.

Stuart raised his glass. “Well, here’s to successful sea-trials, eh lads!”

“Aye, awl fifteen minutes o’ them,” Kenny muttered derisively.

The drinks flowed, and as the evening wore on, the heat of the fire and the drone of background chatter conspired and I found myself slipping into a soporific coma. But something in the back of my mind was needling away. Something crucial we’d forgotten.

At a quarter to eleven, I remembered what it was.

“Shit! Steve, the interview with Sky Sports!”

We leapt to our feet and dashed outside to the public phone box. Squeezing inside, Steve dialled the number from a scrap of paper while I rummaged for a ten pence coin.

We were just in time.

“Putting you straight through,” the producer said brusquely. “You’re on in ten seconds.” In the background, we could hear the lacquered voice of a male presenter leading into the interview.

“…And now joining us on the line from the English Channel, we have Steve Smith and Jason Lewis preparing for their historic circumnavigation attempt with three days of sea-trials. Good evening gentlemen!”

“Hi there,” replied Steve.

“So we’re looking at some footage taken earlier today of you pedalling around Salcombe harbour. Water looks nice and calm. The conditions must be very different out at sea, right?”

My expedition partner squinted into the glass of the telephone box, but only his moon-like reflection loomed back. “Yeah. It’s a bit windy…”

“Of course. And Jason, tell us what you had for dinner tonight.”

My mind went blank.

Steve grabbed the mouthpiece. “Porridge.”

“Porridge?” The presenter laughed. “Funny choice for an evening meal isn’t it?”

There was a loud crash. A figure burst out of the back door of the pub, one of the rugby players who’d been drinking in the public bar all afternoon. He began vomiting noisily against the low wall beside us.

“What’s that?” The presenter’s interest was suddenly peaked. “Sounds like someone being sick.”

Steve smirked. “Yes, it’s err… Jason. Doesn’t quite have his sea legs yet.”

“Or maybe your porridge wasn’t to his liking Steve, eh? Ha! Ha!”

Smart-arse, I thought.

“Finally lads, is there anything from land you’re missing already?”

I jerked my thumb towards the pub and tapped my watch. Last orders were in five minutes.

“A couple of beers in a nice warm pub would be nice,” replied Steve, trying to keep a straight face.

“Yes, I’m sure. Ha! Ha! You’ll have to work a bit harder for that now won’t you boys, eh? Maybe in a couple more days once you hit land again. Ha! Ha!”

More like about five seconds once we get off the phone you fathead…

* * *

Cap’n Stevie Smith at the helm

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

July 26, 2012

Pedal Sub Sunk! – the expedition #adventure #travel book excerpt 8

Moksha capsize drill in Exeter canal basin

By mid-April, Moksha was ready for a proper sea-trial. First, however, we needed to make sure she would automatically self-right in the event she capsized. Before taking her down to Salcombe, we took advantage of the hand-operated crane at the museum to flip her over in the River Exe. After an initial unmanned test roll, Kenny and I clambered inside the cabin and buckled up using seat belts reclaimed from the Ballistic Cleaning van. Kenny had borrowed a camera to film. Steve and Chris operated the crane.

As she tilted to ninety degrees, water began spewing in around the sliding hatch. My head was resting on the plywood roof, hair swimming in a rising pool of water.

“You okay Kenny?” I shouted, watching the proboscis flip upside down.

“Yeah. This seat’s comin’ apart, tho.”

The water was up to my eyes. “Jesus!”

Then, a gut-wrenching spin – “Woooooaaaahhh!” – and we were suddenly upright again, torrents of water cascading everywhere.

What happened next was one of the most humiliating episodes in the entire expedition. Having benefited so greatly from the loan of the workshop, we’d decided to stage a media event to raise publicity for the museum, which was struggling to avoid closure.

The idea was to pedal Moksha around the sheltered canal basin, letting press photographers snap the world’s first two-man ocean pedal boat going through her paces, and then wrap up with interviews.

Chris Court from the Press Association was there on the dockside. He was joined by a carrot-headed journalist claiming to be from Yachting Monthly, and several other reporters from local papers. The next evening, when we pedalled out of Salcombe estuary to spend our first night at sea, one of the Sky Sports television channels would run a live interview patched through from our newly installed VHF radio, running some of Kenny’s pre-recorded footage in the background.

Cautiously, I pedalled out into the muddy-brown river, swollen and turbulent with recent rain. Steve stood in the cockpit posing for the cameras.

“Over here Steve. Give us a wave!” yelled the snapper from the Western Daily News.

“Can you turn the boat around and come towards me, please?” This was the Dorset Evening Echo.

Steve leaned his head into the cockpit. “Did you hear that Jase?”

“Yup, just give me a second.” I shoved the rudder hard over.

Nothing happened. I tried pulling and pushing my hands in opposite directions, but there was still no response.

“Err… Jason…”

The current was turning the boat.

“We need to turn around, mate!”

“I – I can’t! The rudder’s jammed or something!” I tried pedalling backwards. It was hopeless.

The flood run-off was sweeping us sideways down the river, faster and faster, the water sloshing and gurgling all around. And now there was another sound, like low, rolling thunder.

“Jase!” shouted Steve. “There’s a fucking waterfall!”

Pedalling like the clappers, the best I could do was head broadside to the current, aiming for a concrete wall bordering a builder’s yard.

KERRUUNNNCH! The sickening sound of splintering wood echoed across the basin. Moksha was now drifting stern first, all control gone. Steve scrambled out onto the foredeck, frantically snatching at low-lying willow branches. Our disgrace was complete when a noisy black inflatable appeared and plucked us off the lip of the dam just in time. Blushing furiously, we were dragged back to the waiting line of journalists, all of them sucking on the ends of their pencils, trying desperately not to laugh.

The next morning an article appeared in The Daily Star tabloid,entitled: PEDAL SUB SUNK!

According to the Yachting Monthly reporter, in reality a scumbag hack who’d clearly never been anywhere near a sailboat in his life, ‘A pedal powered submarine was swept out to sea by high winds … before capsizing and sinking’.

As well as learning a lot about the nefarious workings of the press that day, we made our acquaintance with an essential feature of the operational workings of the boat. Steering depended entirely on something called a centreboard, that three-foot-long piece of timber we’d left behind in the workshop.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

July 18, 2012

Enter the Guildford Street Gang – the expedition #adventure #travel book excerpt 7

The expedition’s UK patron, HRH The Duke of Gloucester, christens Moksha prior to the River Thames launch. 1994.

As well as fallings-out, another feature of being continually broke planning an expedition was the need to learn a staggering array of new skills we couldn’t afford to pay anyone else to do. This meant learning how to use a computer, no mean feat back in the days of MS DOS, writing proposals, press releases, public speaking, public relations, drawing up budgets (ever-hopefully), pitching to potential sponsors, applying for visas, researching route options, first aid training…

One thing beyond us, however, was how to film it. After two early camera operators fell by the wayside, a magical solution transpired from north of the border in the form of Kenny Brown, a native Glaswegian and budding documentary filmmaker. We met for a show-and-tell one March evening at the Chandos pub, north of Trafalgar Square. Steve and I couldn’t understand a word Kenny said. The thick Scottish brogue firing off at a thousand words a minute proved utterly unfathomable:

“Soonds loch an amazin’ adventure yetois haegot gonnae thur.” [1]

“Uh, I’m sorry?”

“So when daeyetois think yoo’ll beheadin’ aff ‘en?”[2]

“Eh? What was that again?”

He was an intriguing character to look at. A pointy nose, shaped like a turnip pulled out of the ground at an awkward angle, was set above a mouth too small for its head, the top of which was shaved entirely apart from a forelock of brown hair sprouting out like a proboscis. His eyes were shrewd and constantly moving, scrutinizing, suggesting a razor sharp mind at work.

Being at a loss to understand a single word he was saying, the proboscis transfixed me instead. Occasionally, when he leaned forward for his beer, it slipped and dangled over his glass like some tubular sucking device. Fascinated as a child by the emergency stop cords on trains, it was all I could do not to reach out and give it a good yank to see what might happen.

Kenny worked part time as a bicycle messenger to supplement his filmmaking aspirations, and lived in a spartan North London squat with eleven others. His milky complexion was maintained by an exclusively vegan diet, upheld with strict Calvinist-like fervour along with a number of other austere opinions, not least a violent dislike of slackers, hippies, and anything remotely touchy-feely. As Steve began outlining our plans to interview schoolchildren along the way for a film on world citizenship – “To encourage empathy, tolerance, and compassion between cultures” – I noticed Kenny squirming in his seat. From what could be deciphered from the rapid-fire volleys, his main interest in the project was the biking, the filming and “Taykin’ phoo-oos.” Everything else was fluff.

Despite the language barrier and emotional allergies, Kenny’s show-reel was inspired, and his no-nonsense, can-do attitude clearly an asset. He was duly invited to join. A week later, I became the squat’s thirteenth member, partly to concentrate on the media effort with Kenny, but also to create breathing space between Steve and I. We’d be living in each other’s pockets for the next three years as it was. The last thing we wanted was to start the expedition needing a holiday from each other.

Encompassing four floors of a rambling Russell Square town house, the Guildford Street squat quickly became the nerve centre for the press campaign, filming, bike equipment, food, and other overland logistics. Though the place was functional, comfort was not a word to use in the same sentence to describe it. The walls and floors were stripped bare. There was no heating. During the freezing months of March and April, Kenny and I spent our days bundled up in every piece of clothing we owned, tapping away at a pair of prehistoric computers salvaged from a skip, writing sponsorship proposals until the early hours of the morning. Exhausted, we would then roll up on the floor and grab a few hours sleep.

Gulag-like conditions aside, the squat’s other denizens yielded a veritable treasure trove of artists, authors, musicians, blaggers, and petty criminals. The Guildford Street Gang was always ready to lend a hand in the effort, in some cases becoming semi-permanent fixtures. There was Jim, a disc jockey and editor of the mordant political magazine Squall, who volunteered as the expedition’s unpaid press officer; Catriona, a voluptuous redhead, whose adroit handle on English prose knocked our sponsorship proposals into shape; Fingers, an amateur boxer turned professional thief, who specialized in cheque fraud; and Martin, a mild-mannered vegetarian chef and skilled bike mechanic, who offered to set up our bicycles and assemble the food for the Atlantic crossing.

The combined effort produced a very different outcome to what otherwise might have been had the expedition actually managed to hook a title sponsor, as money, and the way it twists agendas, never came into it. At our first major press event on the River Thames, when the expedition’s UK patron, HRH The Duke of Gloucester, christened the boat Moksha, the Guildford Street Gang expedited logistics.[3] The groundswell of an organic support network was a characteristic of the expedition that stuck early on, becoming central to its identity over the years. It kept the whole thing real, a human-powered expedition to its core.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

[1] Sounds like an amazing adventure you two have got going there.

[2] So when do you two think you’ll be heading off then?

[3] Moksha is a Sanskrit word meaning freedom, or liberation, from all worldly desires, ignorance, and suffering. For Hindus and Buddhists, it represents the last state of transcendence before nirvana, the final release from Samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth (reincarnation). The choice of name was inspired by Aldous Huxley’s book, Island.

Cinematographer Kenny Brown uses air mattress to stay afloat mid-ocean.

July 13, 2012

Sponsorship Struggles Begin – The #expedition #travel book excerpt 6

Hugo Burnham

It was the spectacular indifference of the UK business community, patronage we’d naïvely assumed would be a shoe-in considering the Unique Selling Point on offer, which sowed the early seeds of demise with the boat builders. Steve was sending them as much money as he could. Even so, by Christmas, proper compensation for their efforts was looking no more likely than it had a year previously. Hugo and Chris were becoming understandably disgruntled, and relations were stretched to breaking point.

Our visits to help work on the boat didn’t improve matters. As well as being ham-fisted with power tools, we unknowingly dragged them into working their weekends when all they really wanted was to be taken out to the pub and rewarded for their efforts.

Like the proud parents of an angelic child whom the rest of the world sees as an abomination demanding never-ending attention, Steve and I had fallen into the trap of assuming that everyone working on the project – which already bore the hallmarks of a Frankenstein monster – shared the same enthusiasm of working long hours and drawing unemployment to keep body and soul together.

Money troubles aside, in January Steve decided Hugo needed to be relieved of his role as support team leader, a position that involved transporting a camera crew and supplies through the wilds of Siberia. The boat builder’s fierce independence, natural distrust of authority, and caustic satire made for amusing repartee, but for occasions when everyone needed to be singing from the same hymn sheet, they were considered potential liabilities.

Steve and I drove down from London to the Marshwood Vale for a meeting with Hugo at The Bottle Inn, home of the world-famous nettle eating competition – an appropriate venue for the task at hand. Having known him since the age of five, I asked to be the one to break the grim news. Also, I knew of Hugo’s particular dislike of Steve’s self-styled leadership, and having been through similar ordeals letting band members go in years gone by, I knew it best to tell a person straight up, giving the reasons afterwards.

My request, however, was denied. As expedition leader, Steve wanted to do it himself.

It was dark by the time we arrived. The public bar, with its low oak beams and smoke-stained ceiling, was near empty. We bought a round of Palmers IPA and planted ourselves on a pair of stools next to a roaring fire. Ten minutes later Hugo breezed in, ordered a pint, and took a stool opposite. The atmosphere bristled with tension. He knew something was up.

Steve began: “Is there anything about your attitude, or approach to being support team leader, you feel needs to change, Hugo?”

Oh no, I thought, not a trick question. Just tell him he’s off the team!

Hugo cocked his head to one side and twiddled his waxed moustache. “Err… nope.” He looked nonplussed. “Can’t think of anything.”

Half an hour later, the meeting broke down, everyone bent out of shape. Poor old Hugo stormed off into the night, unsure of what was being asked of him. Steve was exasperated with Hugo for remaining stubborn enough not to submit to self-critique. I was furious with Steve for essentially trying to get Hugo to sack himself.

Would it have made a difference being more upfront? Who knows. Either way the result was the same, and the fallout horrendous. A childhood friendship between Hugo and I was forfeit. Our parents, who had known each other for decades, were forced to take sides. To cap it all, relations between Steve and I were badly strained, leaving the smouldering embers for future resentment to flare.

Chris was also put in a difficult position. Obliged by his friendship with Hugo to down tools, he was forced to make an impossible decision: show solidarity with his boat-building partner and walk off the job, or stand by his commitment to a project he felt proud to be a part of, and ultimately responsible to. Not least, because the very thing he and Hugo were creating, in a sense, defined it.

Fortunately for the expedition, he chose the latter. But it cost him a friendship too.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

#Sponsorship Struggles Begin – The #Expedition #travel book excerpt 6

Hugo Burnham

It was the spectacular indifference of the UK business community, patronage we’d naïvely assumed would be a shoe-in considering the Unique Selling Point on offer, which sowed the early seeds of demise with the boat builders. Steve was sending them as much money as he could. Even so, by Christmas, proper compensation for their efforts was looking no more likely than it had a year previously. Hugo and Chris were becoming understandably disgruntled, and relations were stretched to breaking point.

Our visits to help work on the boat didn’t improve matters. As well as being ham-fisted with power tools, we unknowingly dragged them into working their weekends when all they really wanted was to be taken out to the pub and rewarded for their efforts.

Like the proud parents of an angelic child whom the rest of the world sees as an abomination demanding never-ending attention, Steve and I had fallen into the trap of assuming that everyone working on the project – which already bore the hallmarks of a Frankenstein monster – shared the same enthusiasm of working long hours and drawing unemployment to keep body and soul together.

Money troubles aside, in January Steve decided Hugo needed to be relieved of his role as support team leader, a position that involved transporting a camera crew and supplies through the wilds of Siberia. The boat builder’s fierce independence, natural distrust of authority, and caustic satire made for amusing repartee, but for occasions when everyone needed to be singing from the same hymn sheet, they were considered potential liabilities.

Steve and I drove down from London to the Marshwood Vale for a meeting with Hugo at The Bottle Inn, home of the world-famous nettle eating competition – an appropriate venue for the task at hand. Having known him since the age of five, I asked to be the one to break the grim news. Also, I knew of Hugo’s particular dislike of Steve’s self-styled leadership, and having been through similar ordeals letting band members go in years gone by, I knew it best to tell a person straight up, giving the reasons afterwards.

My request, however, was denied. As expedition leader, Steve wanted to do it himself.

It was dark by the time we arrived. The public bar, with its low oak beams and smoke-stained ceiling, was near empty. We bought a round of Palmers IPA and planted ourselves on a pair of stools next to a roaring fire. Ten minutes later Hugo breezed in, ordered a pint, and took a stool opposite. The atmosphere bristled with tension. He knew something was up.

Steve began: “Is there anything about your attitude, or approach to being support team leader, you feel needs to change, Hugo?”

Oh no, I thought, not a trick question. Just tell him he’s off the team!

Hugo cocked his head to one side and twiddled his waxed moustache. “Err… nope.” He looked nonplussed. “Can’t think of anything.”

Half an hour later, the meeting broke down, everyone bent out of shape. Poor old Hugo stormed off into the night, unsure of what was being asked of him. Steve was exasperated with Hugo for remaining stubborn enough not to submit to self-critique. I was furious with Steve for essentially trying to get Hugo to sack himself.

Would it have made a difference being more upfront? Who knows. Either way the result was the same, and the fallout horrendous. A childhood friendship between Hugo and I was forfeit. Our parents, who had known each other for decades, were forced to take sides. To cap it all, relations between Steve and I were badly strained, leaving the smouldering embers for future resentment to flare.

Chris was also put in a difficult position. Obliged by his friendship with Hugo to down tools, he was forced to make an impossible decision: show solidarity with his boat-building partner and walk off the job, or stand by his commitment to a project he felt proud to be a part of, and ultimately responsible to. Not least, because the very thing he and Hugo were creating, in a sense, defined it.

Fortunately for the expedition, he chose the latter. But it cost him a friendship too.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

July 10, 2012

Presenting “The Banana Boys” – The #Expedition #Book excerpt 5

Chris Tipper (L) and Hugo Burnham (R) stapling hardwood veneers

With Chris and Hugo working in Exeter, surviving on the dole and the proceeds of loose change thrown into a donations box outside their workshop, Steve and I based ourselves in London, also surviving on the dole, a target of endless abuse down the pub.

“What the bloody hell are you two thinking?“ roared Lofty, our six-feet, six-inch Yorkshireman friend over a beer at The Dove in Hammersmith. Tears were streaming down his cheeks from laughing so hard. “I mean, thirty-five quid a week on the Rock ‘n Roll isn’t going to get you around the world now is it? Word of advice lads, forget the whole pea-brained idea.”

Finally, as if disclosing classified information, he leaned forward and hissed, “Joost admit it, you two losers aren’t going anywhere – apart from the bar that is. Now get the fookin’ beers in!”

As a used car salesman buying old bangers for a pittance at South London car auctions and then flogging them for scandalous sums through the free ads paper Loot, Lofty wasn’t one to talk about going anywhere, either.

But this was typical of the UK’s home-grown brand of Tall Poppy Syndrome, a nationwide condition whereby anyone caught breaking ranks and trying to sneak their life off in a new direction was automatically branded a turncoat, a traitor. And heaven forbid they actually become successful. Convention called for people to keep their heads down in their little rut. If you tried to make a run for it, the mob would drag you down like a pack of wolves, back into the shit pit with them.

Secretly, it made us even more determined to prove them wrong.

A few people took the idea seriously, Steve’s father being one. Stuart had the energy of a five-year-old trapped inside a fifty-five-year-old body. Raised in the George Muller orphanage in Bristol until the age of fifteen, he wore the grizzled mantle of a survivor, beaten into shape by the brutish conditions and regular thumpings of the bible. He quickly became a walking, talking evangelist for the expedition.

Perhaps inadvertently expressing a piece of his own wounded soul, Stuart had a remarkable talent for making a person feel genuinely needed, especially when it came to forking out the cash. His local pub, The Prince Alfred in Queensway, was a favourite early hunting ground. Introducing himself with a winning smile and tip of his leather Crocodile Dundee hat to a group of complete strangers, he could sweep aside the initial scepticism – on occasion, outright hostility – and within five minutes have them all eating out of his hand. Even during the embryonic stages when the expedition was still just a fantasy, his infectious enthusiasm regularly had customers handing over ten pounds for a vinyl name on a boat that didn’t even exist yet.

This was the early seed money that helped purchase materials to start building the boat. Steve then set out to bicycle 1,700 miles from London to Marrakech, completing his goal in an impressive seventeen days, adding a further £3,250 of individual pledges to the pot. At the same time, a concerted letter-writing campaign to marine equipment manufacturers yielded a steady trickle of paints, resins, rope, polycarbonate windows, bilge pumps, watertight bulkheads, a compass, and so on. In return, we promised the ultimate in field-testing, and photographs of their products in action. Mars UK donated 4,000 Mars Bars. My father talked the British Army out of 250 MRE (meals ready to eat) ration packs.

Despite early successes with equipment, there was still the small matter of where £150,000, the budget for the entire project, would come from. Over the next twelve months, more than 250 tailored proposals were submitted to a wide range of prospective title sponsors, each one followed up persistently by phone. They were met with an equally persistent stream of rejections:

“It’s a wonderful idea … truly inspirational,” read the response from a popular battery manufacturer. “Linking longevity to our brand is a perfect fit. However, the three years proposed for the event is a little too long even for one of our batteries!”

Translated as: Hey guys, we’ll all be pushing up daisies by the time you finish this thing…

Or, one from a well-known insurance corporation:

“The opportunity of associating our company with your daring adventure is a little too risky for our sponsorship strategy at this time.”

Translated as: Watching your boat sink a mile out from shore on national television, with you guys wearing one of our shirts, will do little for customer confidence…

More often than not, it was just a form letter:

“After careful consideration, we regret to inform…”

Translated as: Bugger off you scroungers and get a job like everybody else…

Even Richard Branson turned us down because, according to his PR people, “Richard would want to do this himself.”

Translated as: Just bugger off.

Then, in early February, our prayers were answered. A £30,000 offer came through from Fyfe’s Bananas to be a supporting sponsor. With one backer in place, attracting others would be easy.

There was, however, a slight catch. The deal involved turning the boat into a giant banana, painted yellow, and pedalling our first ocean as “The Banana Boys.”

It was too humiliating a prospect to consider seriously.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis

Stuart Smith, Steve’s dad, our early fundraising evangelist

July 5, 2012

Raising the Dream – The Expedition Book excerpt 4

By ten o’clock, there was still no sign of Chris and Hugo. The two photographers were trading anxious glances, perhaps wondering if they were the unwitting victims of a prank by their picture desk editors: “I need you to drive to the Arse End of Nowhere and shoot a story about a couple of nutters planning to use a pedalo to go around the world. You know, one of those things they rent out for five quid an hour on the Serpentine Lake in Hyde Park. Come in number ten, your time is up!”

It certainly sounded like a hoax.

Just then, a flatbed lorry with orange flashing lights rumbled through the marina entrance, a creaking Land Rover lashed to the top. An equally dilapidated looking trailer bore something resembling an oversized canoe, painted white. If it weren’t for the Automobile Association stickers on the side of the cab you’d be forgiven for thinking the gypsies were in town.

The ramshackle procession ground to a halt and the driver’s side door burst open, letting a waft of smoke billow out into the crisp morning sunlight. The driver emerged looking wild-eyed and shaken, and staggered off in the direction of the public lavatories. Next came three characters stepping straight off the pages of a Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comic book.[1] The leader was the spitting image of Freewheelin’ Franklin, a pirate with crooked teeth, ponytail reaching down past his backside, and a two-prong waxed goatee dangling from his chin like the whiskers on a catfish. Fat Freddy followed, freckled, with a ginger Afro. The last of them, Phineas Freakears, was tall and lithe with a large rudder for a nose, and locks of dark hair hanging around his head like lampshade tassels.

Spotting Steve and I by the water’s edge, the trio altered course in formation and floated towards us as if on a cloud. All of them were grinning like Cheshire Cats.

“Aarrr, yer mangy dogs!” roared the pirate.

“Thought you boys weren’t going to make it,” Steve replied tersely.

“’Course we’d bloody make it Smithers!” retorted Hugo. “Mainly thanks to good ol’ Eddie here and his AA card.”

The ginger Afro bobbed and grinned and strafed the air with a machine gun laugh. “Hehehehehe! Got a call from Chris just after midnight last night, asking if I’d kept up my AA membership. Next thing I knew we were all in the Toll House having a – hehehehehe! – lock-in, waiting for the recovery van to arrive.”

“Bloody lucky,” said Chris, alias Phineas, looking furtively over his shoulder to make sure the driver was out of earshot. “The AA guy twigged we didn’t have any money for fuel, but we’d sprinkled some sugar around the petrol cap. Spun him a yarn about having an argument with some skinheads in the boozer. Bastards must’ve poured sugar in the fuel tank after they got kicked out. What could he do?”

“Worked bootifully!” boomed Hugo. “Couldn’t start the motor could ‘e? He’d blow it good ‘n proper loik. Had to call for a flatbed.”

Steve was now smiling, won over by the latest ingenuity that kept the expedition moving forward on financial fumes.

An hour later, the virgin hull slipped off the back of the trailer into the reservoir. Standing waist-deep on the boat ramp, Chris wrestled the one-inch stainless steel propeller shaft through the deep-sea seal leading into the hull. He then fastened a two-bladed, fifteen-inch aluminium propeller to the end.

Steve and I climbed gingerly aboard, the hull wobbling unnervingly. A fighter-pilot-style cockpit of polycarbonate windows served as a protective shell, at the rear of which a builder’s breezeblock doubled as a seat. The propulsion system comprised the A-frame of a cannibalized bicycle flipped upside down and bolted to the keel. Both the crank arms and front sprocket remained attached. But instead of a back wheel, the chain powered an industrial gearbox turning the drive through ninety degrees. This, in turn, spun the propeller shaft.

Steering was like operating a sports kite. Two lengths of rope ran forward from the top of the rudder to a set of pulleys either side of the cabin. The pulleys turned the lines 180 degrees back to the pedaller, who pushed and pulled a pair of handles salvaged from an old angle grinder in alternate directions for port and starboard.

With the photographer from The Times perched on the roof, nervously clutching his camera, Steve lowered himself carefully onto the breezeblock, and pressed his bare feet to the pedals. There was a squeal of complaint. Then the boat moved forward, grudgingly. Only a few feet, but it moved. And we were still afloat.

The expedition now had sea legs.

[1] Cartoon strip hippies from San Francisco with a talent for smoking vast quantities of marijuana and defying authority.

All Rights Reserved – © 2012 Jason Lewis