Michael Lopp's Blog, page 42

June 30, 2014

All Hail Jaqen H’ghar

No spoilers as long as you don’t click on links

I’m a fan of Jaqen H’ghar. The very minor character who was featured primarily in season 2 of Game of Thrones, I feel had a disproportionate impact on Arya Stark and I’m delighted to see that at the end of of Season 5 there could be further exploration of this complex and compelling character.

During my recent vacation, I realized that I wanted to re-watch all scenes involving Jaqen and Arya and the process wasn’t incredibly hard. Fire up the Game of Thrones wiki, find his page, and then map references to episodes. Using that as a script, I fire up iTunes and scrub episodes to watch these selected scenes. Voilà.

This experience revealed something interesting about the show to me. While there are certainly dependencies which tie the different plots together, the different narratives, I believe, can stand on their own. Imagine just a cut of Games of Thrones that contain scenes involving Theon Greyjoy – would that be good TV?

The point: I would pay good money for a recut Game of Thrones where I could choose the character that I wanted to follow – and that’s it – that’s the only scenes I’d see. I doubt this would be viable without first seeing the show proper, but I think it’d be a great way to explore a specific character.

June 28, 2014

One Night Ultimate Werewolf

As I’ve written about before, I’m a fan of Werewolf. In fact, as part of a leadership training program I developed several years ago, we made the class of leads-to-be play Werewolf because it’s, well, a great way to see how people lie.

There are problems with the classic game as written about on Boing Boing:

The two biggest problems with classic Werewolf are the need for a non-playing moderator, and the fact that players who are killed early in the game (sometimes before they get a chance to do anything at all) are in for lots of downtime.

One Night Ultimate Werewolf gets around some of the annoying parts of the classic game by making the game fast and eliminating the need for a moderator – I’m going to give it a whirl. Still, I like the longer running games where there is ongoing complex battle of wills involving the remaining players. When the game goes on for many nights, you get to see how someone truly… lies.

June 27, 2014

Anger Gets Results

From Yves Morieux and Peter Tollman via qz.com:

All of this means that strong emotions in the workplace may not mean what you think they do. Don’t assume you understand their meaning until you’ve examined the context in which people are doing their work, and have found out what they’re actually doing.

Non-intuitive spot-on thinking.

June 17, 2014

Busy is an Addiction

There’s a seductive dark side to The Builder’s High. The high afforded us by our brain when we are productive is delicious. For me, it’s comparable to the endorphin rush after a good workout. A foul mood vanishes, the weight of stress is lightened, and what was complex and difficult to fathom appears knowable.

Of course, I want more.

The issue, just like exercise, is that each time you build, the high becomes slightly harder to achieve. Part of your hormonal reward is based on the fact the thing you just built has never been built before. It’s novel and your brain commensurately rewards the new because it has learned after millions of years of evolution that doing so is collectively good for our species.

The situation arises: you enjoy the highs, but you are unable to create enough new to support these highs, so you trick your brain into rewarding you for doing far less – you convince your brain of the dubious value of being busy.

Gosh, I Feel… Great

Monday morning. I roll over to my nightstand and grab my iPad. Has anything blown up in the last six hours? No texts and no urgent emails. A quick scan of news sites shows me what the planet current cares about and then I head into my cave after making a pot of coffee. Another deeper email scan to deal with the first round of mails that need attention followed by a glance at my calendar – the day is full. Nine meetings, blocked out for lunch, currently done at 6pm. Another quick scan of the planet and I’m in the car.

After decades of following this protocol, I’m certain of what I’m doing – I’m building mental momentum. I’m convincing my brain through a constant firehose of content of one thing: We are going to be super busy today – it’s going to be awesome. How about a hit of the good stuff? Now, I can rationalize this morning preparation as gathering context and mentally preparing for the day but what I’m really doing is overclocking my brain. This is why I’m drinking coffee. I want to make sure by the time I hit the office, I’m working at 112%, I’m walking fast in the hallways of the office with a smile on my face, I am ready to fully crush this day.

What I am really describing is a chemical addiction to the endorphins produced by my body that are supposed to reward productivity, but I have figured out how to force their creation via my advanced state of busy.

On the Topic of Busy

Rands, I’m a manager. I want to be a exemplar of the behavior I want to inspire in others. We need to have a sense of urgency and I am the living breathing example of that urgency. There are a great many forms of healthy busy. Yes, you can have a calendar packed full of meetings, but in your hurry to be urgent inspiration to others, give me your honest opinion. Are you happy that your day is going to be spent in conference rooms? Are you content knowing that the day will pass and, chances are, you’re not going to write a single line of code because your time will be spent dealing with the humans?

Engineers start their leadership journey hating meetings because of the questions like the ones I ask above, but over time, we start to convince ourselves of the value of these meetings. Like writing code, we start to associate our value with being invited to and attending these meetings. Admit it, if you’ve been a leader for while, it’s a source of pride that you’re booked all day – you’re important – you’re so… busy.

What I am describing is how I’ve lived years of my life. I’ve replaced the concrete act of building with a vast array of abstract tasks and acts that I believe are strategically important to the team, the product, and the company, but I’ve also learned to constantly question the motivation being the busy: Am I doing this because it’s actually important? Or because I like the rush with being busy?

4am

For me, I know when I crossed a threshold into unhealthy busy. It happens at 4am. My eyes open and I’m deeply worried about… something. Let’s be clear what is happening here: at a time when my body should be resting and repairing, my brain believes the correct course of action is to wake-up in the middle of the night to work. These 4am worry sessions are a clear sign that I’m am losing the chemical arms race with my brain.

As an industry, we’ve created an impressive amount of institutionalized drama around getting things done. In large companies, we’ve got armies of people whose job it is to make sure that we understand the importance of that critical deadline. We’ve got leadership motivating us by telling us someone is going to eat us, so we better hurry. There are important people who’ve invested their money and are eager to see a return on their investment. We are surround by stimuli built to drive us harder and faster.

My advice is not that we should eagerly and fervently build the next thing, my advice is to constantly take the time to stop and understand the true nature of your busy.

June 15, 2014

An Unreasonable Request of Impossible Data

The last winter in the United States was goofy. While a majority of the USA was completely frozen, California spent a good portion of the holiday with terrifyingly warm temperatures. We’re talking shorts and flip-flops on Christmas. Now, if you were frozen, you are wondering why I say it’s terrifying. It’s because I am my own best weather station. The fact there was no rain for months in a state that leads the nation in production of fruits, vegetables, wines, and nuts, no rain isn’t bad because my plants are dying, no rain is a historic disaster on many levels.

Having lived in California for my entire life, I was panicky about the weather forecast in early December. When the forecast remained sunny and clear for weeks and weeks when it should be cold and pouring, I become increasingly concerned. Problem is, in the Internet age, we have worldwide satellite imagery at our fingertips that gives a firehose of data down to the micro-climate, but weather prediction – and specifically weather apps – still blows.

Give Them a Break

Let’s first give weather people and weather apps a break. It’s a matter of unreasonable expectations combined with a very hard problem. What your average weather information seeking human is looking for is the answer to a very specific question, “Please tell me with high certainty this specific weather-related fact for this extremely specific location (like where I am standing right this second) and predict this specific fact in this location for every single moment for at least five days in the future.”

These facts, this forecast, in the modern age is built using a combination of computer-based models that describe the atmosphere and a generous dose of human input that is required to pick the best possible forecast model based on pattern recognition skills, knowledge of model performance, and knowledge of model biases. Sounds hard, right?

Even with all of this amazing technology at our disposal, the tried and true approach for figuring out the current state of weather is, well, looking outside. Attempting to determine what might occur at your favorite location likely involves your favorite weather website where you look for the basic forecast. For a more complete forecast, you might have downloaded a weather application and it is here where the unreasonable request of impossible data results in some of the, well, varied application design that you’ll find in iOS.

There are well intentioned engineers and designers behind each of these apps, but this is collectively a design mess. Still, when you understand they are trying to competently answer every impossible question using incredibly complex data for humans who are used to the Internet knowing everything, you can cut them some slack.

Persistent High Pressure

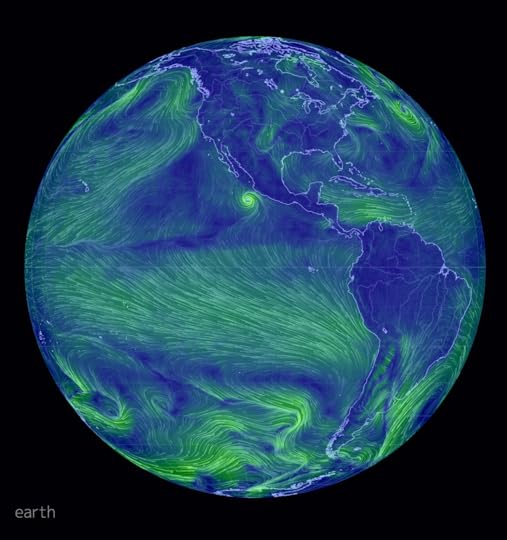

It was during the long winter of no rain that I started to look for new online resources that didn’t explain how long we were screwed, but why. It was the Dad who found Earth Wind Map and it was during California’s long dry spell that I kept returning. Take a look:

What this more current image doesn’t show is that during the long dry spell there were these incredibly persistent high pressure regions parked over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of the northern US states. These regions were keeping whatever potential weather was being created circling up there around Alaska while we Californians worked on our tans while wrapping presents. Whenever a 10 day forecast would talk about potential rain, I’d fire up Earth Wind Map and confirm, “Is there a chance?” High pressure region not moving? No chance.

Earth Wind Map is built on public data using off-the-shelf open source technology to visualize one set of very complex data: how is the wind moving around the planet? That’s it. No precipitation. No temperature. Just the wind. Compare Earth Wind Map with this:

Earth Wind Map elegantly deploys a common design principle of simplification. It’s just… the wind. There are lots of knobs and dials you can tinker with on the site to look at different aspects of the wind, but the front page is a well-designed visualization about wind. It does not tell me how windy it is where I’m standing right now, but it turns out those wind patterns are the ones which are going to push precipitation one way or the other. That’s useful information, but I need more to get answers to my unreasonable questions.

Rain Soon

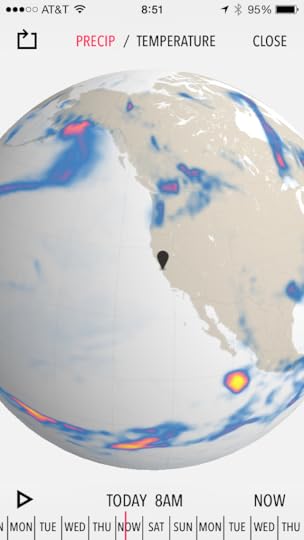

The Dark Sky weather application started as a kickstarter project with a simple goal: using my precise location, tell me when it will rain and for how long for the next hour or two. The killer feature in the initial release was a notification. Several minutes before it started to rain where you were standing, Dark Sky would notify you, “Rain soon.”

Let’s be clear. With this notification, Dark Sky was only doing slightly better than you sticking your head outside and looking at the sky. You weren’t going to better build your day around a comprehensive forecast, you mostly were better prepared for a real time decision regarding whether or not your upcoming walk would involve an umbrella.

But it felt like magic. Your phone would vibrate, you get a text from Dark Sky that read “Rain soon” and soon there would be rain. Dark Sky employed the same approach as Earth Wind Map – build one thing well. Build trust by answering one question elegantly.

Now, subsequent versions of Dark Sky have expanded their feature set to include additional features including a five-day forecast, but it remains my go-to weather application for its beautiful neon map, which shows rain for a brief window in the past and future. I don’t know if Dark Sky answers your questions, but it has begun to answer mine.

Curate Your Curiosity

I’m delighted to see the vast array of weather applications being shipped and, chances are, I’ve seen each and every one. The apps that remain on my phone are similar in terms of design philosophy: they’ve chosen to answer a few questions elegantly… beautifully.

More importantly and completely unintentionally, their intentional sparseness requires me to care more about what I’m asking. Weather prediction is a complex problem sitting on top of an ever-changing pile of even more complex data, and the more you understand this complexity, the more informed your questions.

I don’t need weather apps to answer all my questions. I need them to quickly, reliably, and elegantly answer a handful of questions. Combined, these answers start to draw a picture that I can only complete by being endlessly curious. It’s the best strategy to find answers to my endless unreasonable requests.

June 1, 2014

Chaotic Beautiful Snowflakes

You arrive at work. You sit down at your desk and you scan your inbox for potential disasters. Two mails pique your interest. You write brief responses to nudge the engineers in the right direction. Nothing else is urgent so you walk to the kitchen to get breakfast. You sit down with three fellow engineers who are also working on your product. During conversation over the course of breakfast, you discover that you and Phil are working on exactly the same problem, so you decide that Phil is going to take point and you two will chat once he’s done.

Nice, crossing that off my list.

Walking back from the kitchen, you see Joey, who runs the design team. He stops you to ask, “Why are we meeting at 1pm?” You explain that you’re unclear about the workflow for the feature you’re working on. He explains that the team met late yesterday afternoon and he thinks he has a working paper prototype, which he conveniently hands to you. You glance at it and say, “Yeah, this is exactly what I need. No meeting necessary, but this is wrong. You mean that, right?”

Joey nods, “Yeah, good catch. Thanks.”

It’s been an hour since you arrived. You’ve checked your email, eaten, and unexpectedly crossed two significant to-dos off your list simply by walking around the office. The only things that were planned were your rough arrival time and your intent to have breakfast.

Everything else… just happened thanks to proximity and serendipity.

Non-Obvious Work

You are a single hypothetical you. You are a unit of a person who surprisingly has their shit together this morning, and while you haven’t written a single line of code yet, you’ve created a significant amount of work. Let’s recap:

You sent two emails that need to be digested and acted on by the recipients.

You and Phil had an ad-hoc meeting in the kitchen where you discovered and fixed a duplicate effort problem and assigned the work to Phil.

You and Joey had a hallway design meeting where you iterated on a design and killed an unnecessary meeting. Sweetness.

And you ate.

My point: you are a software engineer. You worked very hard to learn about the science of computers. You enjoy the calm, rational aspects of developing software and I’ve just written 396 words about an hour of a hypothetical morning and described a slew of unplanned work you never planned.

And that’s just you.

You’re part of team of 23 engineers who have also spent this morning walking around the building and bumping into people, talking, discovering, making decisions, and it feels organic and natural. And it is. All of these random interactions are a sign of a healthy team, but you are underestimating the amount of both obvious and non-obvious work it’s creating for unsuspecting others.

You Squared

In the 1970s, a systems engineer at TRW named Robert J. Lano invented the N-squared chart. The diagram is used to “systematically identify, define, tabulate, design and analyze function and physical interfaces.” One of the simple byproducts of a well-designed N-squared chart is that you quickly understand how fast complexity increases as you add more functions to a system. The chart visually documents what Big O notation achieves in describing the complexity of algorithms. In the case of a O(N2) algorithm, its performance is directly proportional to the square of the size of the input data set.

You, your productive morning, and all the other yous walking around the building are a wonderful N-squared problem. While not mathematically sound, the fact is that you significantly underestimate the amount of work that you generated this morning. You could document and communicate the obvious work, but you can’t document all the unexpected side effects of your actions. In a large population of people, it’s close to impossible for an individual to perceive and predict the first order consequences of their well-intentioned actions, let alone the bizarre second order effects once those consequences get in the wild.

Humans – engineers especially – significantly underestimate the cost of getting things done in groups of people. We focus on the obvious and measurable work that needs to be done: iterate on a design, write the code, test, iterate, deploy, and we put a huge discount on the work required to share that process with others.

Engineers have a well-deserved reputation for regularly being off by a factor of three in their work estimates, and that is partly due to the fact that we are really shitty at estimating the non-linear chaotic work (and fun) that exists in keeping a group of humans pointed in the right direction.

On Leadership

It is entirely possible that I am permanently biased regarding the necessity for leadership in a large group of people. I am actively watching zero leadership experiments in progress at Medium, GitHub, and Zappos, but I am a firm believer that you need a well-defined leadership role to deal with unexpected and non-linear side effects of people working together. You need someone to keep the threads untangled and forming a high-functioning web rather than a big snarl of a Gordian knot.

There are a slew of good reasons to hate crap leadership. There are leaders who hoard the information they discover. There are leaders who have crap judgement and perform awful analysis and make precisely the wrong decisions. There are leaders who are genetically bad at communication. And there are those who are simply a waste of air and space; they define their existence by creating unnecessary work for others to make themselves look productive.

It is likely that you’ve run into one of these leaders and their distasteful anti-human behaviors, and this has tainted your opinion of leadership. It is equally likely that you remember these crap leaders a lot more than the leaders who quietly and effortlessly helped. The ones who gave you the data you needed when you needed it. The ones who pointed you at precisely the right person at the right time. The ones who served as a sounding board, worked hard, and when they made a decision, you found their judgement reasoned and fair.

Whether your opinion is that leadership is mostly positive or negative, you’ve certainly come upon the question: “What does my lead do all day?” A portion of every leader’s day is the detection, triage, and resolution of work we never planned. Sometimes it’s a complex people-related fire drill, sometimes it’s a simple clarifying conversation. But speaking as a leader, I can confidently say that it’s 9:23 am and I have a full calendar of meetings, but I don’t actually know what I’m going to do today. It’s an essential part of the gig.

Chaotic Beautiful Snowflakes

Working as a team is hard work. Let’s forget about product market fit, let’s ignore web scale architectures, and let’s blow right by your last valuation. The work isn’t hard because of the things you know; it’s hard because of the unknowable. This piece is not an argument for more leaders, it’s a request to appreciate that the unknowable arrives – every single day.

You are a beautiful snowflake with your own unique behaviors that affect your team on a daily basis in ways you can’t even imagine. Let’s multiply this “uniqueness” by the 23 other snowflakes wandering the building. And then let’s throw our hands in the air and ask, “How in the world are we going to get anything done with all these unique goddamned snowflakes bumping into each other and creating additional unexpected work that we can never plan for?”

So, take a moment. Think about your last hour at work. Think about what you were planning on doing and what you actually did. Did you do what you expected? Probably not. The hard work of great leadership isn’t just managing the expected tasks that we can predict, it’s the art of successfully traversing the unexpected.

May 29, 2014

Briefly, Internet Trends 2014

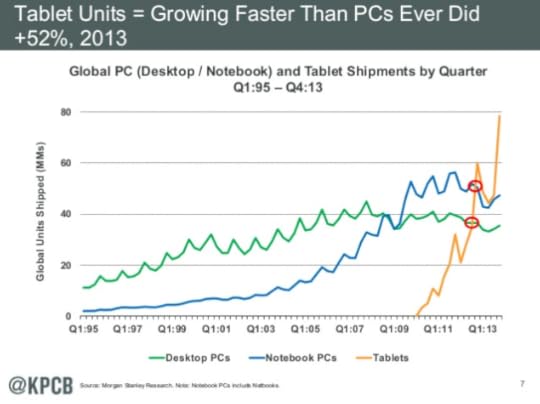

Coming in at 164 slides, Mary Meeker (partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers) delivers a massive annual State of the Internet deck each year and it’s worth reading a couple of times. The report provides framing and background to many of the tech-related news stories of the past year. My brief notes:

I’ve been hearing a theory that tablets are going to be squeezed out by every better smartphones and portables. Here’s another theory: tablets are a force of nature and not going anywhere:

In eight years, “Made in the USA” smartphones went from 5% market share to 97%. (Slide 10)

$38 billion in mobile advertising spend in 2013. (Slide 16)

+95% of networks compromised in some way (Wait, what?) (Slide 18)

We’re nowhere near the number of IPOs and amount of venture financing that occurred during the tech bubble. (Slide 21 & 22)

81% of high school freshman graduated in 2012, up from 74% five years ago.

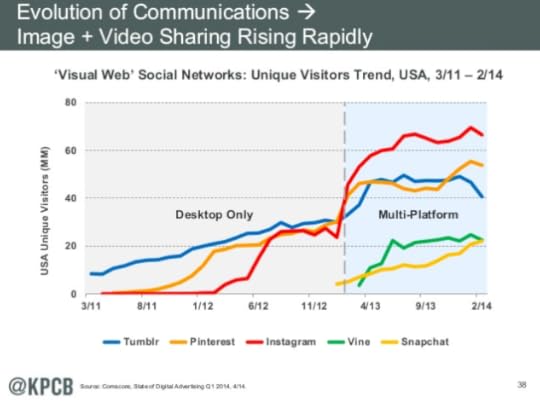

People like to look at pictures (Slide 38):

While $1.3B is nothing to sneeze at, digital music track sales are down 6% year of year. (Slide 50)

1.8B+ photos uploaded a day! (Slide 62)

There are 10 sensors in the Galaxy S5 (Gyro, fingerprint, barometer, hall, RGB ambient light, gesture, heart rate, accelerometer, proximity, compass). (Slide 67)

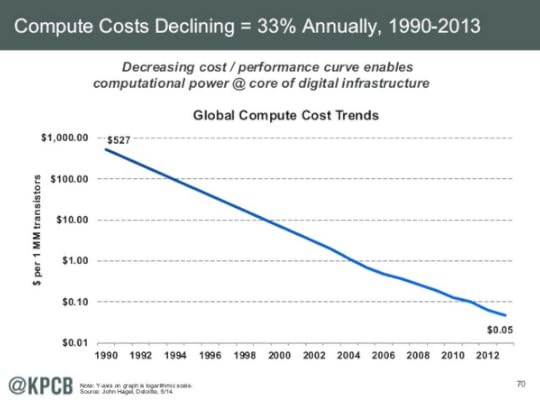

Computing costs have, apparently, decreased at 33% annual for the past 23 years. (Slide 70)

Still trying to figure out what this means, but it’s important, “A fan base shares, comments, curates, creates”. (Slide 114)

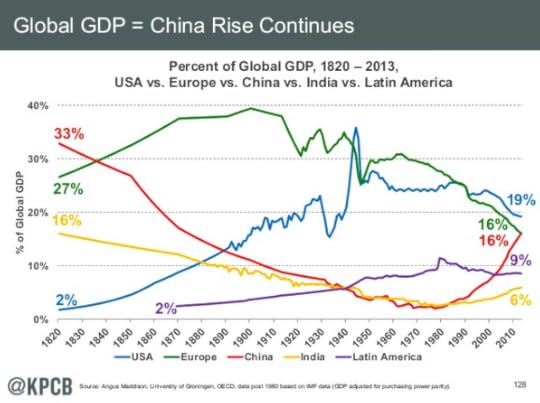

Holy crap China. (Slide 128)

May 28, 2014

Most People Tend to Move Toward the Status Quo

Compelling Wednesday morning piece from Quartz that explains both the four kinds of distinct decision-making styles as well as three common traps leaders who no longer find themselves making pivotal decisions as a leader.

Coming up short on ingenuity, the other key measure of leadership decision making, can also be a blind spot for many people. Often, they fail to see the extent to which they stay within the comfort zone of the status quo. They don’t know what they don’t know. From the vantage point of their comfort zone, new ideas appear as more work and disruptions than they are worth.

Syncing is a Notoriously Difficult Problem to Solve

And it’s also free as part of the recently released Vesper 2.0:

There is no charge. No subscription. You just create an account using your email address as your identity and it works. I’m as suspicious of a free lunch as the next guy — probably more so, in fact. But Vesper Sync is not a free lunch, because Vesper is not a free app. Sync should be a feature, not something you have to pay extra for.

May 21, 2014

I Think in Outlines

One of the key tenets I talk about regarding understanding the engineering mindset is that software engineers think in terms of flow charts. This isn’t exactly correctly – engineers think in code, but most of the planet does not, but, chances are, they understand the concept of a flowchart. You’re in a state. When certain conditions exist, you can move to another state. Sometimes… branches or decisions occur.

A key aspect of a flow chart is that fact it is visual. You can draw it. You can walk up to the white-board and clearly visually describe the part of the system that needs explanation. I find this often a better means of explanation than sitting down how the code is organized and how it works. There’s tool in the domain of explanation and organization which I’m not certain is the domain of engineers, but serves the same purpose: outlines.

I remain in a troubling post-Things world where I’m using a bizarre combination of Asana, Field Notes, and my brain to keep track of the world. This is an inefficient system that until recently has been creating just enough value to quiet the productivity rage. However, stuff has recently started falling through the cranks; it’s not clear what belongs in Asana versus Field Notes versus my brain. Yeah, I recently gave Atwood’s three things concept a try and it did shine a clear light on the three things, but – fact – there are more than three big things to tackle each day.

The current experiment is Workflowy.

As data structures go, a text outline is simple. You have one or more items in a list. An item is defined as some amount of text that may also have one or more sub-items. The only difference between an item and a sub-item is that a sub-item has a parent item. Again, simple.

You can layer all sorts of delicious visuals, features, and meta-data on top of these items, but the mental mode is the same: I have this item and if it happens to have sub-items, it means that the item and the sub-item are somehow usefully related. This simple organization mechanism… calms me down.

I think in outlines. If you I’m building a Keynote presentation, I’m indenting slides. If I’m writing in a Field Notes, I’m organizing the page with headers and details. A quick scan of my Sent folder reveals extensive uses of bulleted and numeric lists. Outlines. Everywhere.

My outlining predilection might be genetic. I was organizing things is list and sub-lists for years before I stumbled on ThinkTank and discovered there was actual software for what I was doing in text files. The demand for outline process clearly wasn’t huge since both ThinkTank and it’s Mac cousin MORE died years ago and have been replaced by… what? Outline mode in Word? It’s crap.

It’s early on, but Workflowy so far hits the sweet spot in terms of simplicity, obviousness, and unexpected power user features. I’ve yet to read a single line of documentation, but I am already well into the development of a large outline for complex on-going project. It works exactly how I’d expect an outline to work, it stays out of my way, and it occasionally reminds me that by the way, there are some cool power use features you might want to check out.

While I’m delighted Workflowy exists, I remain concerned. Given the lack of a vibrant outline application market, I am clearly in the minority of humans who find value in outlining, but an outline is how I think.

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers