Michael Lopp's Blog, page 39

November 25, 2014

Organizational Lessons from Slime Mold

Via Kabir Chibber on Quartz:

Explore, remove hierarchies, and remember what you did wrong and tell someone:

November 5, 2014

FriendDA Updates

I’ve made small changes to the FriendDA based on feedback to this post.

All the proposed changes in the post have been put into the latest version of the FriendDA.

I’ve changed the Creative Commons license to be ShareAlike – it is no longer No-Derivatives.

There’s a Github repository that contains the current Markdown and HTML versions. Fork away.

These changes, I believe, will make the FriendDA slightly more useful. Thanks to everyone who contributed feedback.

October 29, 2014

Brief Thoughts on Marvel

Marvel announced their Phase 3 plans for the Marvel Cinematic Universe yesterday and the best way to describe my reaction is they succeeded in diffusing my excitement about Avengers – Age of Ultron and I’m pretty excited about that sequel.

Some brief thoughts on the state of Marvel:

In 2009, Disney paid four billion dollars for Marvel. It turns out this was a tremendous deal. Check it out…

The first Avengers had a production budget of $220 million and worldwide total lifetime gross of $1.5 billion.

The last Iron Man (released last summer) had a production budget of $200 million a worldwide total gross of $1.2 billion.

Guardians of the Galaxy (released this year) had a production budget of $170 million and, so far, a worldwide total lifetime grow of $752 million.

You can check out the rest of the portfolio’s performance on Box Office Mojo, but the point is: it appears they’ve already made their money back in five years and then some.

Four billion dollars still felt aggressive in 2009, but think about what they were buying. They weren’t just buying a catalog of heroes, they were buying a massive collection of stories about these heroes, their origins, their adventures, and often, their deaths.

These stories have been tested. Marvel (and DC) have no issue mucking with continuity to improve the quality of the universe. It’s called retroactive continuity (or retcon) and it allows writers to resolve errors in chronology and reintroduce popular characters.

I think of retcons as bug fixes. It’s the writers not only making sure the stories all fit together, but also that the stories are relevant and entertaining. When you add the fact that comics are a visual medium, you understand that Marvel wasn’t just buying a catalog of heroes, they were buying a whole universe of compelling and tested scripts and story boards.

The cherry on top is the Marvel Cinematic universe is a retcon unto itself. The script writers of the movies are picking and choosing their facts and stories and knitting together what looks like decade long plot lines designed specifically for the big screen.

Can’t wait.

October 26, 2014

FriendDA v2?

If you don’t care about the FriendDA you should stop reading this now.

The FriendDA was written in late 2008 and it was intended as an experiment to place a smidge of formality on the discussion of perceived precious ideas. Happily, the FriendDA has legs. Since the original publication there has a small, but steady flow of traffic to site, a group of folks have taken up the task of translating the document to various languages (FriendDA in Hebrew), and I’ve made small changes to the original text none of which I believe has not changed the original intent.

I was recently approached with the idea that the FriendDA with small modifications could offer some legal protection and while this contradicts one of the core tenets of the FriendDA, the idea of increasing the usefulness of the FriendDA is appealing to me.

The FriendDA really isn’t for me. It’s intended to be a useful social tool for others who want to stop the moment before they share their important idea and say, “FriendDA?” With the response being either, “What’s that?” or “Of course.” In the “What’s that?” case, the point is to talk about the intent of the FriendDA which briefly is:

I’m disclosing a bright idea to you

Don’t screw me

Or else

None of the consequences are intended to be legal – they’re intended be social. The point of the FriendDA is for we humans to learn to deal with our trust issues sans legal intervention. Still, the idea of giving the FriendDA more teeth is interesting to me and I want your opinion.

There are three changes (in bold) being proposed to the .7 version of the FriendDA. The first two are:

Line 9: Adapting some or all of The Idea for your own purposes unless I say you can.

Line 15: The term of this agreement shall continue until I or someone I authorize makes The Idea public.

I have no issue with either of these changes. The first prevents the Advisor from adapting The Idea for someone else’s purposes which would be nefarious and screw-ish. The second change makes it clear that that the term lasts until the Keeper of the Idea takes the Idea public.

The last change is the big one:

Line 18:

Was: This agreement has absolutely no legal binding. However, upon breach or violation of the agreement, I will feel free to do any of the following:

Proposed: This agreement may possibly have some amount of legal binding. However, it is likely that upon breach or violation of the agreement, I will do no more than any of the following:

The paragraph from the introductory article that this change directly contradicts is:

The FriendDA is a non-binding, warm blanket agreement that offers absolutely no legal protection. I’d suggest if the idea of legal protection is even crossing your mind that the FriendDA is totally inappropriate for your current needs.

A legal advisor suggests,

Therefore, while the doc at friendda.org does say that “This agreement has absolutely no legal binding….” – it actually might. It has all the parts required for a binding contract, namely mutual promises (which can be seen as consideration) and an intent for the parties to be in agreement about what can happen if the agreement is breached, even if they’re mostly psychological. And the agreement also has definite terms and obligations on both parties. Therefore, noting that it might be legally binding makes it a positive to state what will happen if the Advisor breaches.

Again, the proposed change gives the FriendDA slightly more teeth and if you care about the FriendDA, I’d like your opinion on this last change. Once I’ve gathered enough signal, I’ll update the site along with a new subsection which tracks changes from version to version.

Thank you,

Rands

October 25, 2014

Hundreds of People Running Into a Solid Spinning Metal Fence

October 24, 2014

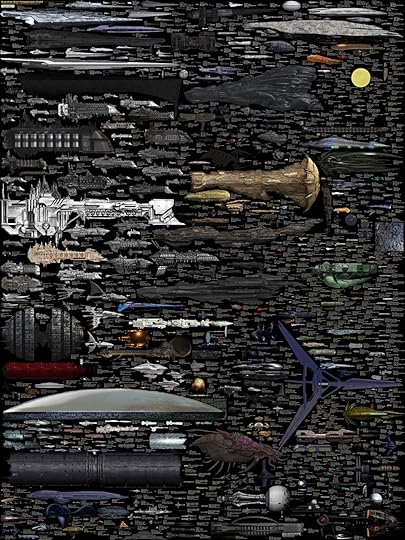

Ship Sizes Across the Universe(s)

October 18, 2014

“We sense when there has been care taken with a product.”

October 16, 2014

The First Addition to the Cloud Classification System in Half a Century

But soon after launching the site, Pretor-Pinney received a couple pictures that didn’t quite fit into existing classifications. One image, taken from the 12th floor of an office building in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, looked positively apocalyptic — a violent and undulating thing menacing the city skyline. “They struck me as being rather different from the normal undulates clouds,”

October 15, 2014

The Old Guard

Dunbar’s Number is a favorite blunt diagnosis for the pains that affect rapidly growing teams. The number, which is somewhere between 100 and 250 describes a point at which a group of people can no longer effectively maintain social connections in their respective heads. What was simple from a communication perspective becomes costly. What was a familiar family that you saw wandering the hallway becomes Stranger Town.

It resonates. It intuitively feels right that we have a threshold for the number of relationships we can maintain in our heads. If your team or company is rapidly growing, it’s worth thinking about how you’re going to help the team feel connected, but I think there is a more interesting emergent behavior during rapid growth, and it’s led by The Old Guard.

They Won

Here’s the poetic origin story of The Old Guard:

A small group of inspired people has an idea, and just about everyone tells them the idea is really stupid, but that’s exactly the same response to the idea that they hear every other day. This small group ignores these naysayers and doggedly pursues the idea, even though on a daily basis it feels like the world is specifically designed to prevent them from succeeding.

It’s a war. The small group is at war with conventional wisdom; they are at war with every comparable startup that is remotely in the same space. But, most importantly, they are at war with themselves. In addition to fighting to bring the idea into the world, they are fighting amongst themselves.

Each day, this small group is learning who they are as part of their struggle to survive. They are learning each person’s strengths and weaknesses. They are figuring out how each person communicates, and each of these essential lessons is learned under the constant threat of irrelevance. These lessons are hard earned – some folks don’t make it – and those who survive this period of painful definition are tightly bound together. They share the same mental scars and they tell the same stories because they have an intimate shared history.

And then the Old Guard starts winning.

The New Guard

After years of struggling, the dream that became the idea becomes the business. A corner is turned and the question changes from, “Are we going to survive?” to “How are we going to scale?” As part of this acceleration program comes the arrival of eager new faces who have heard the stories of success in the face of adversity. They are inspired by these stories and they want to figure out how they can help.

When the New Guard shows up, they notice, well, beautiful, beautiful chaos. Ideas are coming from every direction, decisions are collaborative and high velocity because the team is small enough that you can efficiently ask everyone’s opinion. It’s intoxicating. Execution is shared and it’s terrifying fast because there is little desire to bicker because most everyone still believes they are on the brink of disaster. That’s mainly because they’ve lived in this world so long.

The organization of the Old Guard is instinctively flat. There is rapid and organic error correction because everyone has line of sight on everything. The cost of gathering situational awareness is low because the Old Guard has borderline mystical abilities to figure things out. This is because they’ve got a near-complete mental catalog of the people, their knowledge, and their abilities.

The Old Guard has recognized experience, but more importantly, each day the Old Guard demonstrates to the New Guard that they have instinct. They can rapidly make important decisions with the barest of facts and they have a sense of urgency motivated by their deeply rooted belief that this is the home that they built with their hands and, again, they believe this precious thing could be destroyed in a moment.

The Old Guard’s instinct is well earned and essential, but instinct doesn’t scale without help.

New Guard Friction

The divide that is created between the Old Guard and New Guard is interestingly paradoxical See, the Old Guard recognizes there’s simply too much to do and there is no way the expertise now needed to evolve is under the roof. The problem is these new hires are a cure to a disease that the Old Guard both created and loves. I’ll explain.

The Old Guard hires eager people to build more amazing things, but each additional human creates a growing knowledge and communication tax. The team needs to spend time to make sure each new person understands the company, how things are done, who is responsible for what, and they eventually need to know their responsibilities. Pretty simple, right? Standard on-boarding, right? What about when it’s 10 people? Or 100? Multiply all their educational and communication needs with the fact that each of these new folks is going to add their own unique signal to the communication tapestry, each person is slightly altering the culture simply with their presence, and, oh yeah, everything is going to change in six months anyhow because the team is growing so fast.

The addition of these new people to the existing population transforms the comfortable chaos into legitimate chaos. Decisions start to happen more slowly, responsibility and ownership become opaque, execution becomes stove-piped, and work is duplicated because the organism has likely crossed Dunbar’s number. Situational awareness has become expensive because learning can no longer occur via osmosis.

The New Guard, armed with their new hire spirit and their lack of historical organization instinct, starts on important work that the Old Guard both desires and hates at the same time.

The New Guard:

Starts to write things down both for themselves and for those who will come after them.

Sits down with different teams and agrees to contracts on how they will get work done.

Imports language from prior companies to support and define their various emerging causes. This language often comes in the form of important sounding, but equally mystifying, acronyms.

And they do a lot of this work via the scheduling of meetings.

The Old Guard’s healthy network of informational sources inside of the company (who are also primarily Old Guard) provides an increasingly worrying diagnosis: the New Guard is creating a lot of process that smells like big company bullshit. The Old Guard worries: they worry that all these eager new faces in their company are fundamentally changing the culture.

Here’s the rub: The Old Guard can’t scale their company without the help of the New Guard, but the Old Guard’s instincts about what works in this particular organism are based on lessons from the past rather than the requirements of the future. When the Old Guard is tested, when something goes sideways in the company, they fall back on what has always worked in the past, and while this strategy feels familiar and fast, it might not allow them to scale.

A Culture Quandary

The critique of this time of the rising power of the new Guard and their increasing skirmishes with the established Old Guard manifests in different ways: “We’re moving slower”, “I don’t know what’s going on”, “We feel like a big company”, or “We’re forgetting who we are.”

In order to build a healthy company that scales, you’re going to need to build infrastructure and process that is going to connect the various parts of your company. This work is going to feel heavy and unnecessary to those who’ve historically been able to do this work effortlessly and instinctively.

It is entirely possible that too much process or the wrong process is developed during this build-out, but when this inevitable debate occurs, the debate should not be about the process. It’s a debate about values. The first question isn’t, “Is this a good, bad, or efficient process?” The first question is, “How does this process reflect our values?”

The largest battles that I’ve seen at prior companies between the New Guard and the Old Guard exist because the Old Guard has not effectively documented and shared the values that the company embodies. This creates the following dialog:

Old Guard: I feel this process is heavy.

New Guard: I’ve seen this process work at a great many companies and here are the metrics to prove it.

Old Guard: Yeah, something doesn’t feel right.

New Guard: What the hell does feel have to do with it?

What is missing from this dialog is a discussion. The process feels heavy because in this particular hypothetical company, we value velocity over completeness. Whether they’ve written them down or not, the Old Guard embodies the initial values of the company and when they say, “It feels off…” what they are poorly articulating is, “This process that you’re building does not support one (or more) of the key values of the company.”

The Old Guard is the cultural bellwether of the company. I believe that culture is a slippery thing to fully define, but I do believe it is the responsibility of the Old Guard to not only take the time to define the key values that are the pillars of that culture, to communicate the nuance of those values over and over again, and, lastly, when it becomes apparent they are no longer serving the company, they must be willing to let those values evolve.

October 10, 2014

We’re still behaving like the rebel alliance, but now we’re the Empire.

Pete Warden on why nerd culture must die:

And that’s where the problem lies. We’re still behaving like the rebel alliance, but now we’re the Empire. We got where we are by ignoring outsiders and believing in ourselves even when nobody else would. The decades have proved that our way was largely right and the critics were wrong, so our habit of not listening has become deeply entrenched.

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers