Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 146

July 16, 2015

Using Pinterest to Market Children’s Picture Books

Today’s guest post is by author and publisher Darcy Pattison (@FictionNotes).

Two years ago, I committed to indie publishing of my children’s picture books and middle grade to YA novels. As I wrote here, the first eighteen months were devoted to production, distribution and accounting. The last six months, my focus has switched to marketing.

Often for indie books, people will say that the book’s quality—or lack of quality—is the reason marketing efforts for a title won’t work. So, let me start by explaining that my marketing process includes sending the books out for review in major review journals for children’s literature. My books have been reviewed in Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and School Library Journal—all favorable reviews. One book, Wisdom, The Midway Albatross received a starred PW review. Another book, Abayomi, The Brazilian Puma was named a 2015 National Science Teacher’s Association Outstanding Science Trade Book. Starting from that basis, I wanted to see what I could accomplish through online marketing.

Imitating Best Practices for Adult Books

I knew that indie authors who focus on adult writing had already figured out many ways to succeed. However, I didn’t know if the same advertising and promotional activities would work for children’s picture books or novels. It made sense to try these things, even if I suspected they worked best for romance writers.

I knew that indie authors who focus on adult writing had already figured out many ways to succeed. However, I didn’t know if the same advertising and promotional activities would work for children’s picture books or novels. It made sense to try these things, even if I suspected they worked best for romance writers.

Another piece of advice is to maximize a particular channel by creating a sequence of iterations. Often writers give up too early when they should tweak copy, photos, offers, and so on. However, I decided that my criteria would be sales; if no sales resulted from an effort, then I wouldn’t pursue it. Limited sales would be evaluated as I went to determine if extra tweaking might result in reasonable results.

Here are online ads I’ve tried without any sales:

Facebook fan page promoted post

Facebook ads

Facebook video ads for mobile only

Google Adwords

Giving away review copies of iBooks.

I targeted various demographics to try to get results, but nothing worked.

Here are things I’ve tried that have minimal sales, less than 100 copies:

mailing/newsletter list

setting a first book in a series as free on Kindle and iBookstore

Bookbub ad for the first picture book in series.

The recent Bookbub ad was successful according to their terms. For a free book in the children’s category, they email to 500,000 customers and expect between 2,450 and 10,350 downloads. My book had 12,000 free downloads across all platforms, beating their top predictions. However, sales in the month since then have been less than 100 copies for the promoted book, never mind the other books in the series.

Looking at My Traffic Stats for Trends

After trying some of the major strategies that indies use to advertise adult books, I decided it was time to dig deep into my website statistics to see who was visiting my website already. Because they’d already shown interest, they might be more likely to buy books. I looked at sources of referral traffic, amount of time on page, number of pages viewed by visitors and so on.

I was startled that over 10% of the traffic to my website for the past year came from Pinterest. Organic traffic from Google search engines pulls the most traffic, followed by those accessing the pages directly. From social media, though, Pinterest was the winner by a huge margin. Here’s my Pinterest account.

I saw the power of Pinterest in action on my own website. One post, 39 Villain Motivations had received over 10,000 repins from July 2014 to April 2015. Even with a mediocre image, it was popular. Advice from Pinterest experts said that for popular posts, you should create an improved image and repin that. The post has now been repined over 19,000 times!

And that wasn’t an isolated experience. Other successful Pins from my website include:

How to Mock up a Children’s Picture Book – over 4000 repins

5 Ways to Keep a Characrer Consistent – over 3000 repins

Plot: Characters v. Patterns – over 3000 repins

As a marketing channel, Pinterest isn’t often considered, even though Promoted Pins have been available for a while. After looking deeper at the platform, I realized it might be a good place to try something for children’s books. Here are some reasons:

Demographics. Pinterest demographics are 80% women; children’s book buyers are overwhelmingly female, whether classroom teachers or parents.

Longevity of a Promotion. In rough terms, the half-life of a tweet is about 5 minutes; a Facebook post lasts 15 minutes; the half-life of a Pin, however, is three months. For the amount of effort, the longevity of a pin makes Pinterest a winner.

Success of others. Even a casual glance at the education category on Pinterest showed many lesson plans from the Teachers-Pay-Teachers platform. Others were clearly reaching teachers on this platform.

One thing struck me: I’d only casually played at Pinterest. What if I really paid attention to the details? What could I accomplish? I am working now to maximize my account, boards and pins. (Read my tips on using Pinterest for authors.)

In the process, I’ve started to understand the possibilities of Pinterest.

Using Pinterest to Market Children’s Books

Pinterest is a visual medium, showcasing stunning images; picture books are composed of stunning images. Add this fact to the points made above about demographics, longevity and inspiration of other marketers, it makes sense to try to market children’s picture books on Pinterest. But how? I studied Pinterest to see what was already there and imitated some of the trends I saw.

Boards with book covers. The most commonly seen thing is book covers. I created a group board, Nonfiction Children’s Books and other children’s book authors joined in the fun of pinning their book covers. To join the group board and be able to pin, email darcy@darcypattison.com.

Pins of themed picture books. Over and over, I saw pins with 8-12 picture books grouped around a theme: pirates, grief, Japan, first day of school and so on. In fact, I finally started a board of Themed Picture Books. It’s a great reference if you’re looking for books on a certain topic, but it doesn’t help an author sell a certain picture book.

Lesson plans for one picture book. I also found that my most popular book, The Journey of Oliver K. Woodman (Harcourt) had lots of lesson plans for it. I created a board to collect those.

These three types of boards featuring children’s picture books created some interest, but not a lot. Certainly no book sales.

Then, an inspiration struck.

Creating a Preview of a Picture Book on Pinterest

Starting this week, I’m trying a new experiment: a Pinterest preview of a children’s picture book.

What if I put an entire picture book on Pinterest as a preview, as a way for people to see and read the entire book? It’s an innovative marketing concept, one wholly appropriate for children’s picture books. Unproven, it may lead nowhere. But I firmly believe that no one will find the best way to market children’s books without experimenting.

I had just given away 12,000 ebooks, with virtually no sales. The advantage to a Pinterest preview is that it can’t be downloaded. If someone wants to read the book with a child or in a classroom, they must buy it. It retains the advantage of giving away an ebook, but the book only lives on Pinterest. I could also send reviewers to the board to read the book, instead of sending an easily pirated PDF into the world.

I had just given away 12,000 ebooks, with virtually no sales. The advantage to a Pinterest preview is that it can’t be downloaded. If someone wants to read the book with a child or in a classroom, they must buy it. It retains the advantage of giving away an ebook, but the book only lives on Pinterest. I could also send reviewers to the board to read the book, instead of sending an easily pirated PDF into the world.

First, I created pins. Current wisdom says vertical pins of 735 x 1102 pixels (or a 4 x 6 ratio) work best. I created a Photoshop template with an explanation that this pin was from a set that included a complete picture book preview. On Pinterest, any pin might be repinned. I couldn’t count on Pinners to only repin the cover of the book; any page might suddenly capture attention and repins, so I had to be ready for repins to be out of order.

Using the template, I created 32 separate pins. (Related: Why do picture books have 32 pages?)

Next, I had to decide where to send people when they clicked on the pins. My goal is sales. My first instinct was to alternate between links to Amazon and the iBookstore. However, Pinterest strips all Amazon affiliate links while leaving the iBookstore affiliate links. I had planned to use those links to monitor clicks. So, instead, I’m sending them to my webstore on MimsHouse.com, my indie publishing house. Each listing there has links to all online distributors, which gives customers options to purchase on their favorite site. The advantage is that my website analytics will let me monitor links and clicks.

Descriptions are crucial for a pin. Following Pinterest limits, I created five descriptions of under 500 characters each. Actually, they were under 400 characters, because I wanted to follow a best-practice of including a link in the description.

I went to Pinterest and created a board for I Want a Dog, making sure to include keywords in the board’s description. I wanted to make sure everything was perfect before it went live so I set it to secret initially.

I chose the Education category for the board. I could’ve chosen Kids and Parenting, but that category seems to be dominated by photos of babies. The category of Film, Music and Books is dominated by best-selling movies and music. Books run a poor third place in this category. Education seemed more suited to my needs.

Finally, while uploading the pins, I had to remember that Pinterest will not allow you to rearrange pins. The first pin up will be the last shown. That meant I started with a couple promotional pins—read the entire picture book series—then added pages 32, 31, 30 and so on to the front cover. If you mess up on this, you’ll have to delete every pin and start again, so be clear on the order you want.

After uploading a pin, I edited that pin to add a link to iBookstore or Amazon, and to add the description.

Evaluating the Preview Pinterest Book

Over the next few months I’ll evaluate the success of this experiment, based on the following criteria:

Sales. I’ll monitor the statistics from my website to see if anyone clicks through to buy.

Repins. I’m interested to see which, if any, images pick up traction as repins. If one image starts to shine, I’ll likely try a Promoted Pin for it.

Website referrals. A few pins refer people back to my website. For those, I’ll be able to see referrals on my analytics.

Will this result in sales? I don’t know. It’s a different concept, one I hope is perfect for marketing a children’s picture book. But it’s unproven. All we can do is take risks and try.

If you’re on Pinterest, go take a look at the preview of I Want a Dog. Of course, if you enjoy it, please repin one (or more) of the pages.

July 15, 2015

5 On: Steve Brewer

In this 5 On interview, Steve Brewer discusses the highly coveted experience of having a book adapted to film, his personal writing and editing challenges, the tricky experience of using a pen name, and more.

Steve Brewer (@BrewerRules) is the author of more than twenty-five books, including the Bubba Mabry mysteries and the recent comic crime novels A Box of Pandoras and Lost Vegas. The first Bubba book, Lonely Street, was made into a 2009 Hollywood comedy starring Robert Patrick, Jay Mohr, and Joe Mantegna. In 2013, Random House imprint Alibi announced a three-book deal with Brewer. The trilogy is published under his pen name, Max Austin, and started in April 2014 with Duke City Split. The latest, Duke City Desperado, published in June 2015.

Brewer teaches part-time in the Honors College at the University of New Mexico. He’s taught classes at the Midwest Writers Workshop, SouthWest Writers, and the Tony Hillerman Writers Seminar, and regularly speaks at mystery conventions. He was toastmaster at Left Coast Crime in Santa Fe, NM, in 2011. He served two years on the national board of Mystery Writers of America and twice served as an Edgar Awards judge. He’s also a member of International Thriller Writers and SouthWest Writers.

A graduate of the University of Arkansas–Little Rock, Brewer worked as a daily journalist for twenty-two years, then wrote a weekly syndicated column for another decade. The columns produced the material for his humor book Trophy Husband. Find out more at Amazon and his blog.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: You finish a first draft of a novel in about three months. That seems fast to me, as someone who takes at least six months and at most a year to finish a first draft. What is your first-draft method? Do you create an outline? Follow a reliable formula?

STEVE BREWER: After I dream up the initial story idea, I do an outline of the plot. One paragraph for each chapter. The outline for a three-hundred-page book is usually about twenty pages. Once I’ve got that clothesline to hang things on, I start writing the first draft, trying to produce thirty to forty pages a week. I intentionally go fast, trying to capture the flow, and then spend six months on the revisions.

Imagine a desolate world in which only one book from every author is allowed. This is the book that will represent you forever. Which single book of yours do you save, and why?

It’s got to be Lonely Street, my first novel and the one that was made into a 2009 movie. Lonely Street introduced bumbling private eye Bubba Mabry, who has since appeared in eight other books.

While writing Lonely Street, I was already thinking of a series. Bubba Mabry is such a likeable character, despite his many shortcomings, that I thought readers would want more. He’s a goof, a bumbler, but he’s also human in a time when too many good guys come off like superheroes. Plus, he’s funny as hell.

After a few Bubba books, I started doing standalone mysteries as well. Those are my main focus these days—books about crooks with a different cast of characters for each. Bubba is told in first-person with lots of recurring characters. It’s more fun for me to make up a whole bunch of new people and to jump from one character to another as the story unfolds.

When you made the switch from mystery to crime, your agent persuaded you to adopt the pen name Max Austin. Joyce Carol Oates, to explain her submission of the novel Lives of the Twins under the pen name Rosamond Parker, writes in a 1987 New York Times essay, “There is the possibility, however quixotic, of making a fresh start—in [Romain] Gary’s words, ‘renewing’ oneself—and not being held to severe account for it.” Have you experienced a fresh writing start as Max Austin, whether in the freedom to use a new voice or an opportunity to not feel beholden to a style, genre, or approach Steve Brewer’s readers might expect?

Because I started writing these novels before I had any sense of Max Austin, I didn’t really get that sensation. Instead, I felt the pressure to pull together three disparate storylines into a fourth book in a way that made sense. That one, not under contract yet, is called Duke City Heat.

And, actually, the pen name happened the other way around. I was writing these standalone novels set in Albuquerque, each starring a different cast of crooks, and my agent suggested we shop them around under a pen name. When Random House/Alibi picked up the books, they kept the pen name and marketed the books as a trilogy.

And, actually, the pen name happened the other way around. I was writing these standalone novels set in Albuquerque, each starring a different cast of crooks, and my agent suggested we shop them around under a pen name. When Random House/Alibi picked up the books, they kept the pen name and marketed the books as a trilogy.

Also, I don’t consider myself having made a “switch from mystery to crime.” It’s a continuum, and all my books have elements of mystery and suspense. But I did decide, a few years ago, to specialize in books about crooks. I always find the bad guys (no matter how foolish they are) to be more interesting than the good guys.

What—if anything—about the craft of writing, so many years into it, challenges you now? That is, what’s the most hair-yanking aspect of writing a new novel? And has what challenges you changed over the years?

I’ve been trying to write fiction for nearly thirty years now, so there aren’t many problems I haven’t already encountered. That gives a writer a confidence, I think. The biggest challenge always is boiling the story down to its essential elements. I try to name that tune in as few words as possible. As Elmore Leonard said, “Try to leave out the parts that people skip.”

When I started writing fiction at age thirty, there was a huge learning curve. I’d been a journalist since I was eighteen years old, and all I’d learned about writing there gave me a leg up over most people who are just starting out, but I still didn’t understand dialogue and pacing and dramatic structure. I did, however, know the value of rewriting. That’s where the game is won. With practice, I got better at first drafts, but I still do seven or eight revisions before I show a new manuscript to my agent/editor.

What is your standard rewrite process? What are you adding, what are you taking out, what are you likely to tweak and tweak and tweak (the way some poets will mull over “period or comma?”), and what usually needs the least amount of attention?

I write in scenes, and I always try to come in late and get out early. That is, I trim away the throat-clearing at the beginning and the wrapping-up at the end of each scene. You usually don’t need them. Just give the readers the dramatic parts. So, mostly I trim stuff. Sometimes, I go too far and have to put stuff back.

5 on Publishing

In October 2013, you wrote a blog post that was optimistic about the pen name Max Austin. In February 2015, you wrote, “I wish now I’d fought to publish under my real name.… I’ve published two dozen books under my own name and developed a small following, but that hasn’t yet translated into sales for Max Austin. In some ways, it feels like starting over after more than twenty years in the business.” Have you considered reclaiming Steve Brewer, and what would it mean professionally if you did?

I’m waiting to hear whether Alibi will want more titles in the Duke City series. If so, I’ll continue to be Max Austin for a while. Once I’m done with Alibi, however, I’m going back to my own name for all my books. It’s important to sales of my backlist.

You maintain a blog site under your real name, and when I searched, I couldn’t find a website for Max Austin. This is what I did find (which had me craving wine before I’d even had lunch):

Have you received any pressure to put more marketing efforts behind the Max Austin name? And is your Goodreads bio, which begins, “Max Austin is the pseudonym of writer Steve Brewer,” a way of raging against the pseudonym?

I think my publisher distributed that tagline, so there was no rage involved. I’m happy for people to make the connection between Max Austin and me. I’m very proud of the new books. That said, I didn’t want to build a website for a brand that is likely to be temporary. Now, if my publisher wanted to build such a website …

In June you gave a lecture, “How to Screw Up Your Writing Career,” during which you discussed the seven deadly sins of writers. Starting with the beginning of your fiction-writing career, what were a couple of your biggest screw-ups, whether or not they’d fall into the “deadly sins” category?

I changed agents too many times, trying to find a champion, before I figured out that you have to be your own champion. Like most newbies, I was in too big a hurry to show my stuff to agents and publishers while I was still learning the craft. I wrote two very bad books while learning. My third attempt at a novel (never published) landed me an agent. My fourth attempt was Lonely Street.

How did having Lonely Street adapted to film affect (a) immediate book sales and (b) your overall writing career?

Sad to say, it didn’t make a lot of difference in either. The movie looks good on my bio, and Lonely Street remains in print, but otherwise I’m just limping along like everyone else.

Sad to say, it didn’t make a lot of difference in either. The movie looks good on my bio, and Lonely Street remains in print, but otherwise I’m just limping along like everyone else.

Many writers fantasize about not only publishing a book, but about having their published book become a movie. How did Lonely Street happen and what was that like?

A young moviemaker named Peter Ettinger, who grew up here in Albuquerque, wrote the screenplay and directed the movie. He was specifically looking for stories set in Albuquerque, and this was years ago, before Breaking Bad. It took years, but he got LS made. And I got a nice payday.

The years before the movie went into production were a roller coaster. I’d get word that some actor or studio was interested in the project, and I’d be bouncing around the house. Then that was out, and some new actor would be interested. More bouncing. I finally learned that this is the way Hollywood works. Everybody is an optimist. This was a good lesson in dealing with other producers who have optioned my non-Bubba work over the years. I’m pretty calm about it all now.

When LS finally got made, I spent a couple of days on the set in Los Angeles, and it was a lot of fun to hang out with the actors and the crew and the technical people. Everyone was very nice to me, and I ate way too much of the free food that floats around a film set.

Peter and the producers got cross-wise during the editing process, and they forced him to add some slapstick stuff that he (and I) didn’t like. The movie did the film festival circuit, then in 2009 went to DVD, where it’s still available. The lack of a wide theatrical release was disappointing, but you won’t catch me complaining. I know lots of authors who’d like to get Hollywood’s attention. I’ve been lucky.

Peter and I stay in touch, and he would like to make others of my books into movies one day. Fingers crossed.

July 14, 2015

A Conversation With the SELF-e Team: Exploring Payment for Authors

iStockphoto: Quintanilla

Note from Jane: Earlier this month, I featured a guest post on how self-published authors can distribute their ebooks to libraries, through the SELF-e program from Library Journal and BiblioBoard. That post wasn’t without controversy, since the program doesn’t pay authors for licensing of their ebooks. I invited to the folks behind SELF-e to comment further on the program, to start a dialogue about its purpose and to offer greater transparency about it. Porter Anderson offered to host a conversation, which you’ll find below. (Full disclosure: Porter is a paid consultant with Library Journal, which he discusses in further detail.)

For those catching up, SELF-e is a service for self-published authors who would like to have their ebooks available to patrons in American library systems. The key objection voiced about SELF-e is its business model: the service is free to independent authors who submit their ebooks but offers no royalty payments to those authors for checkouts of their ebooks.

Access to libraries has been difficult for independent authors so far. While SELF-e’s program gives authors automatic availability to librarians at the state level, and a chance at national-level consideration, the author community is right to place a high premium on the principle of authors being paid for their work.

Library Journal’s SELF-e Select is the curated collection of indie ebook submissions for the national library system.

I spent an hour in conversation on this with:

Ian Singer, vice-president and group publisher of MediaSource/Library Journal

Guy Gonzalez, director of content strategy and audience development of MediaSource/Library Journal

Mitchell Davis, chief business officer of BiblioLabs/BiblioBoard, and formerly a founder of BookSurge, which was bought by Amazon and integrated into CreateSpace.

This is the team behind SELF-e. It’s a partnership between Library Journal and BiblioBoard. It has no outside funding. Its costs during its year-and-a-half of development have been covered by the two companies without revenue. The easiest way to think of the partnership is to see Library Journal as the editorial component, evaluating and curating submissions, and BiblioBoard as the technical enabler and sales channel. SELF-e stands on the BiblioBoard platform, which is designed as an interface between libraries and their e-patrons—it’s the system many libraries use to allow patrons to access ebooks, historical databases, learning materials, videos, and other digital library materials.

Library Journal is a client of Porter Anderson Media, my consultancy. This means that I am bringing it to authors’ attention as a consultant on retainer. This is not an affiliate relationship, so my compensation does not depend on how many authors use the service. Therefore, my brief is to familiarize authors with the availability of this new development, not to pressure them to enroll in it. I believe that SELF-e can be a boon to some, but it’s not for all authors.

In the course of my discussion with Singer, Gonzalez, and Davis, two key points were made.

SELF-e is designed in response to libraries’ acquisition needs, particularly in terms of local author communities.

The program is still in its early stages, and it’s possible that royalty payments for authors might be considered later.

From left are Library Journal’s Ian Singer and Guy Gonzalez, and BiblioLabs’ Mitchell Davis.

How Libraries Acquire Materials: The Need for Curation and Scale

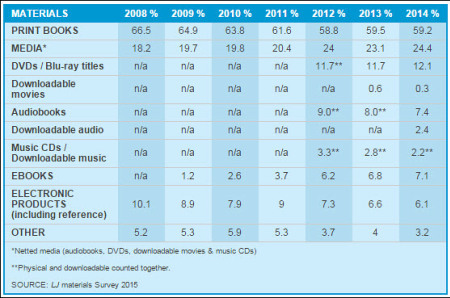

We all know that digital is gaining. One of the services of Library Journal is an annual “Materials Survey” that sorts out US public libraries’ budgets and collection breakdowns. In her report from March, Barbara Hoffert writes:

Trending of Materials Budget Breakdown, Average Findings Based on Population Served, 2014. Library Journal Materials Survey 2015

This year, print books account for just 59% of the budget on average—a figure that has, however, held steady in this survey’s findings over the last three years. Meanwhile, ebooks have jumped from 1% of the budget in 2009 to 7% today. Almost all respondents [libraries] now offer ebooks, up from 66% five years ago.

Singer says that it was very much a grassroots aspect of that ebook jump that prompted the inception of SELF-e about 18 months ago.

“What we know about library acquisition,” Singer says, “is that libraries need to feel comfortable in making purchase decisions. That led us to figure out a way to lend Library Journal’s status in the market to helping them feel more comfortable in acquiring certain self-published titles. That, coupled with our understanding of various models of acquisition in libraries made us know that we’re not selling one and one and one and one book. Instead, we’re going to create collections that will comprise 200 titles to start with, and grow over time.”

That combo of requirements—curation and large volumes of titles—Singer says “led us to the conclusion that the pricing model of not paying royalties in exchange for the broad marketing and discovery opportunity that getting content into public libraries would provide to self-published authors” was the way to go. “We’re creating a trusted link to make it comfortable for public libraries to provide self-published materials for the first time…It did not make sense for us to build a royalty scheme at present.”

But is it possible to consider splitting some of what libraries pay SELF-e with the authors?

“It could well be possible in the long term,” Singer says. At this early stage, he points out, no money is coming in. “But as we generate more overall usage,” he says, “we will certainly take a very hard look at remunerating those titles that are circulating more than others.”

Meanwhile, one of the costs of SELF-e is the evaluation of each manuscript submitted for the national collection. That’s an expense not charged to authors. And if the author’s work is selected, they then get to use the SELF-e badge on their book covers and sites to help promote their work.

Davis says, “This is not a business yet. This is a cost center right now. We have done nothing but work on this and invest money in it for a year-and-a-half, and we’re just beginning to get to the point that people can recognize it and know what it is. We’re trying to change the way independent authors get their books discovered and that’s a big undertaking to tackle. And there will be all sorts of permutations to this thing as it grows and becomes something that’s mainstream and real. But we just released it.”

Davis says, “This is not a business yet. This is a cost center right now. We have done nothing but work on this and invest money in it for a year-and-a-half, and we’re just beginning to get to the point that people can recognize it and know what it is. We’re trying to change the way independent authors get their books discovered and that’s a big undertaking to tackle. And there will be all sorts of permutations to this thing as it grows and becomes something that’s mainstream and real. But we just released it.”

Gonzales cautions against calling it a start-up, “because people might assume there’s tons of investment capital.” No venture capital or other outside funding has been involved in the development of SELF-e.

“We have funded it completely out of the other parts of our businesses because we believe in it and we believe in its potential. But it’s a long road and we’re right at the beginning,” says Davis.

A Focus on Local Libraries

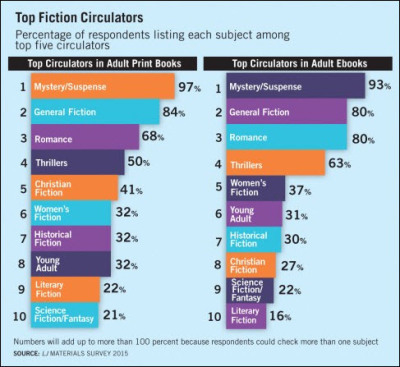

From Library Journal’s Materials Survey, 2015, a look at top circulation in print (left) and digital (right) books among US libraries responding

It’s at the local level that SELF-e had its inception.

Singer says that the initial development was a response to libraries’ needs to interact with their local independent authors. Many librarians have wanted to be able to house and offer local writers’ work, but simply had no way to acquire and then offer it to their patrons. SELF-e provides that mechanism.

“Simply submitting your title to your local library using the SELF-e system is a way for you to have your content in your local library,” says Singer. “And we’re not getting paid for that. We do get paid for the initial sale of the platform to a library.” But that’s a one-time payment, Singer adds, not an annual fee.

“What we’ve been doing for the last year,” Singer says, “is establishing the value proposition, this ecosystem that exists between libraries and their local, self-published authors. We’ve spent more than a year investing in that message, and we’ve succeeded.”

At the local level, Davis says there are already more than 40 library systems using BiblioBoard and SELF-e to interact with local authors. They include some of the top library systems in the country, libraries that are influential as thought leaders among the other institutions. And this is the functionality that he was describing when he spoke to Schwartz for a Library Journal piece in June, about the experience of the Los Angeles County Library system. He told her:

In the last 15 years…millions of books were self-published. Librarians know there are good books in there, but they don’t have the bandwidth to sort through them. So it seemed like a perfect marriage for LJ to become a readers’ advisory service for self-published books. I think that solves a really huge problem for librarians: it lets them make self-published books available with confidence and without a lot of hassle. It also solves a problem when local authors want their ebook in their local library and libraries have had to turn them away. Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) told us they were getting multiple emails a week and would have to say no. SELF-e lets the librarian say yes and engage their writing community more viscerally.

The national curated collection called SELF-e Select, then, is an outgrowth of that grassroots capability provided by BiblioBoard and Library Journal to libraries which are trying to interact with their local author communities.

Gonzalez puts it this way:

The very first and foremost problem SELF-e solved is a way to enable libraries to acquire, archive, and share locally produced content. From that, Library Journal’s evaluation and curation of that locally sourced content from around the country becomes these [SELF-e Select] collections we offer, and that’s the discovery aspect. The first step is that platform, which enables libraries to acquire, archive, and share local content. And then there’s LJ’s evaluation and curation that enables some of that local content to be shared nationally.

Davis, for BiblioBoard’s participation, expands on the point this way:

When a library licenses BiblioBoard, they not only gain the ability to take books from local authors for SELF-e, they also get the ability to work with local filmmakers, local musicians, they get the ability to curate summer reading collections—a whole laundry list of things they can do around engagement. They also become a potential customer for us on some of the other content we make available from more traditional publishers, film studios, national libraries and archives; so there is a business value to us today in SELF-e. We’re solving a problem, and that introduces us to new libraries and makes them aware of the suite of things we offer, to turn them into customers.

SELF-e has been developed not as a revenue vehicle but as a discovery platform for authors. The partners are clear on the fact that it is (a) new, (b) still developing with chances to tweak the model along the way, and (c) reversible.

“Authors can remove their books,” says Gonzalez, “but if they do they probably were not right for SELF-e in the first place. We’re not looking for ‘one and done’ authors. This service was built for authors who are looking to expose a piece of their writing to new readers and build off that by selling them other books, print books, or to build audience for a future book.”

Davis says that people should think about SELF-e not in how it may compare to OverDrive or other commercial library services, but more how it might compare to BookBub (where authors pay to give their books away free or sell them at a discount) or other “permafree” promotions that most successful self-published authors agree are important marketing tools to gain readership.

“Of course, any authors who are doing well financially in the library market today or who have a plan they believe is going to work to create royalties in the library market,” Davis says, “should not sign up for SELF-e. This service was not built for those authors.”

Davis says that, even for the Big Five publishers, library royalties are “a small part of their overall revenue.” When you get past the Big Five, the revenue generated from library channel sales is low in terms of dollars, “even for traditionally published books.” However, Library Journal Patron Profile surveys support that people who discover an author in the library are inclined to go on and purchase a book from that author. In that context, Davis argues, the library can be more valuable as a marketing platform than as a revenue source.

Davis also says that the self-publishing companies that have attempted to provide commercial library distribution services have generated little in the way of author royalties. (In fact, if there are any self-published authors reading this who have stories that reflect library revenue, share them in comments; we would welcome your input.)

Davis maintains that “since practically there’s very little in the way of author royalties flowing from libraries, once you can philosophically get over the issue of royalties in the library market, it becomes a powerful marketing opportunity.”

As before, I’m available for questions in our comments. SELF-e team members are also open to direct inquiry at support@mediasourceinc.com.

July 8, 2015

How Publishers Make Decisions About What to Publish: The Book P&L

Photo by gonzalo_ar / via Flickr

Note from Jane: Last year, I wrote and published the following article in Scratch magazine. It has been edited and updated for my site.

In a widely shared excerpt from his memoir, My Mistake, publishing industry veteran Daniel Menaker described his first experience trying to acquire a book at Random House. His boss told him, “Well, do a P-and-L for it and we’ll see.”

P-and-L. P&L. Profit and loss. However you refer to it, the P&L is a publisher’s basic decision-making tool for determining whether a book makes financial sense to publish. It’s a mixture of the predictable (such as manufacturing costs) and the unpredictable (namely, sales). Nearly every established book publisher uses a proprietary P&L that it doesn’t disclose. (You can find one rare example here, from an outside-of-New-York publishing house, Berrett-Koehler.)

When I started working at F&W Publications (now F W) in 1998, P&Ls weren’t required before signing a book unless the book had to survive primarily on bookstore sales. (At the time, F&W sold many books through its own book clubs and specialty retailers.) By 2001, P&Ls were required for every single title, partly because the publisher went from family ownership to corporate ownership—and because the business was changing.

As an acquiring editor, it was my responsibility to put together the P&L for every title I proposed and to make sure it would hit the target profit margin before wasting the pub board’s time with a proposal. Pub board was a weekly assemblage of key company players in editorial, sales, and marketing who gave the green light to contract authors and titles. When I started negotiating author contracts, my marching orders were to ensure the author advance didn’t go beyond what the P&L indicated would be earned out through sales of the first print run. (This isn’t the case at every publisher, but I worked for a fiscally conservative house.)

Things have changed dramatically in the 15 years since I saw my first P&L. For starters, more than half of book sales now happen online—but the underlying math remains the same. While no author should ask her publisher to see her book’s P&L, understanding the principles of a P&L can help you better appreciate what financial pressures publishers are under, how a book can quickly become a financial liability if the first print run doesn’t sell through, and why advances might look low to you, but high to a publisher.

Click on the image to view full size.

The following P&L is my creation—a from-scratch, stripped-down version of the form a publisher might use. In the breakdown below, I’ll point out areas where I’ve greatly simplified to get the larger point across. Ready to follow along? Visit the Google Doc and use the following text to understand its components.

Title Data

For our example P&L, we’ll use the specs of a typical debut novel issued as a trade paperback original. An average trade paperback is 5.5″ x 8.5″, between 200 and 300 pages (80,000 words), and retails for $14.99 to $17.99.

Why aren’t we going with hardcover? It’s less risky to debut an author in trade paperback; readers are more willing to try an unknown author if the price of the experiment is less than $20.

Author Advance and Sales Quantity

It is nearly impossible to separate the discussion of the advance from sales projections, so we’ll tackle these together. You should be able to make an educated guess at what the publisher thinks it will sell based on your advance (with one caveat, to be explained in a moment).

Daniel Menaker’s discussion of the P&L determined the publisher’s projected sales by working backward from the author’s advance of $50,000. The advance was probably higher than what the author, George Saunders, would ultimately earn out through royalty payments.

Note: Authors receive an advance against royalties; as books sell, authors earn a percentage of sales for each copy sold (a royalty), which is applied against the advance they received. Only once the advance is fully earned out do authors start actually receiving royalty payments. Industry insiders estimate 70 percent of authors do not earn out their advance. Authors do not have to return their advance if the book doesn’t earn out.

For a variety of reasons, it’s fairly common for Big Five houses to offer an advance they know won’t earn out. If you want to look at publishers in an altruistic light, by offering an advance that won’t pay out, they’re essentially agreeing to pay a higher author royalty rate than what’s stated in the contract. (Put another way: they’re fully aware they’re paying an advance that will never be earned back.)

That said, most publishers will calculate an advance after agreeing on a projected sales quantity, which is based on several criteria:

past sales of the author (or comparable authors, for a debut title)

the recent performance of the book’s genre/category for the publisher

subrights deals (such as foreign rights and sales) or the potential for such

whether the title was auctioned (in an auction, several houses compete for a title, which often leads to the publisher overpaying).

At pub board meetings, the sales and marketing team may commit to specific sales figures by channel. Bookstores, including Amazon, represent the majority of sales for most Big Five titles. Depending on the title or publisher, there may be expectations for direct-to-consumer sales (sales directly to readers through the publisher’s website, for instance), specialty sales (e.g., Home Depot, Anthropologie), and mass-market sales (e.g., Walmart).

Note that P&Ls may be done for a specific time period, such as the first six to twelve months of anticipated sales, or for the lifetime of the book.

Author Royalty

For our example P&L, we have greatly simplified the royalty calculation. Most P&Ls apply a different royalty rate to different types of sales. Authors earn a different rate depending on the format (hardcover, paperback, or ebook) and also depending on the sales channel. P&Ls also take into account escalators, which are the sales thresholds at which an an author earns a higher royalty rate. For example, royalties for a trade paperback might look like this:

1–5,000: 8.0%

5,001–10,000: 10.0%

10,001–20,000: 12.5%

20,001 and higher: 15.0%

Hardcover royalties typically start at 10 percent.

Our P&L is for paperback and ebook sales; we’ll pay our author, G. Scott Fitzgerald, an advance that’s roughly equivalent to royalties earned from sales of the first print run.

Specific Title Costs

Any realistic P&L will include the hard costs involved in producing a specific title. In our example, we’ll include basic costs for freelance (copyediting and proofreading), cover design (fees for illustrators or photography, as well as freelance graphic design if needed), and a modest marketing budget. (If we really believed in Mr. Fitzgerald’s book, we’d be looking at a marketing budget well into the five figures.) Other costs that might be included here (not an exhaustive list): ghostwriting, permissions costs if not covered by the author, indexing if not charged against the author, and interior art or illustration costs.

Manufacturing Costs

This is one of the more predictable cost areas. An editor may ask the production department for a manufacturing cost estimate for a title, or the editor may use scale charts that show the unit cost (cost per book) of producing a title based on paper trim size, page count, and print run. As the print run decreases, the unit cost increases. Most publishers have preferred trim sizes to maximize efficiency and savings when printing and shipping. If your book is an unusual trim size, requires interior color printing, or has a high page count, its manufacturing costs will go up.

A good rule of thumb for manufacturing cost: $1 per paperback and $2 per hardcover for offset printing of a black-and-white book at a standard trim, unless you have a very large print run.

Freight costs must also be factored in; estimate about eight cents per unit, assuming domestic printing.

Overhead Costs

Some publishers apply overhead costs to their P&Ls—either specific dollar amounts or a corporately determined percentage that applies to all titles. These costs vary greatly, and may include costs for internal (staff) editorial and design, legal fees, and other infrastructure costs (expensive Manhattan rent, company parties in West Egg, etc.).

Profit & Loss

Here’s where the magic happens! (I won’t say if it’s dark magic or not.) Based on all the data we’ve input into our form, we calculate the financial risk of the debut of The Great American Novel by our next hot author, G. Scott Fitzgerald. A breakdown of the math:

Retail price. Pulled directly from title data.

Gross units sold. Pulled directly from sales quantity. These numbers are only as reliable as the person giving the estimate, and are sometimes based on comparable sales of another title in the publisher’s list. (This is why it can be hard for an author with a bad sales record to get another deal.)

Returns %. Any bookstore can return a book to the publisher for a full refund, whether the sale was made one day ago or ten years ago. Every publisher applies its own average percentage here based on historical return rates by category. The average industry return rate used to be 30 percent. This percentage has declined as ebooks sales have increased, as Amazon sales have grown (Amazon doesn’t return), and as chain bookstores have decreased their orders.

Net units sold. How many books are sold after returns are factored in.

Average discount. Our example P&L has tremendously simplified the discount field. Publishers negotiate specific discounts and co-op costs with each account or retailer. Co-op costs are the fees that retailers expect from publishers for in-store marketing and promotion of books. (Not long ago, there was a prolonged kerfuffle between Simon & Schuster and Barnes & Noble about these fees.) We’ve applied a fairly standard 52 percent, since our novel is primarily a bookstore-driven book, and most bookstores receive about a 50 percent discount, in addition to co-op (if any).

Gross sales. How much money the publisher makes from book sales (with our 52 percent discount), before returns.

Returns. Subtracts money lost from returns.

Net sales. How much money the publisher makes from book sales after returns.

Manufacturing cost for net units. How much it costs to produce the books that are sold, including specific title costs.

Royalty. What the author earns, assuming he receives 8 percent of every print book sale, based on retail price. Some authors receive a percentage of every sale based on net receipts, or what the publisher receives after discounting. For ebooks, most authors earn 25 percent net. In this example, if we intend for our boy G. Scott to earn out his advance from the first print run, he should receive an advance of about $9,000.

Total cost of sales. Totals the author royalty and the manufacturing cost on the print side.

Overhead. Directly pulled from data above.

Net earnings $ and net earnings %. This is how much profit the book will earn for the publisher (in both print and ebook formats), expressed in both dollars and as a margin percentage.

Does the Great American Novel Pass the P&L Test?

It all depends on the publisher’s measuring stick. Let’s say our editor in chief refuses to contract any book that doesn’t make at least $20,000 or a 45 percent margin. This book might be rejected unless we could find evidence that a higher quantity will be sold, or unless we could somehow cut costs.

A good publisher will typically look at each title as part of a larger season of titles. If your imprint releases 20 titles every season, you should have a mix of higher-earning titles and “quieter” books that are more financially risky. If an editor acquires nothing but books that net the publisher $13,000 each, she might not keep her job for very long. But one or two low-earning books can be subsidized by better-selling titles. That’s why you often hear about the celebrity or blockbuster titles subsidizing the other titles a publisher produces.

At this point, it’s both fun and depressing to play the what-if game:

What if bookstores take a lower quantity than projected?

What if the first print run has to be lowered when the book goes to press because the Barnes & Noble buyer doesn’t like the cover?

What if there are unexpected editorial costs?

What if this becomes a breakout title and the book goes back to press for another 20,000 copies?

What if a mass-merchandiser takes 10,000 copies, but at a higher discount of 75 percent?

What About E-books?

A few important notes about ebook sales:

The discount on ebooks is 30 percent if you’re a Big Five publisher.

The ebook royalty at a Big Five publisher is 25 percent of net receipts, not retail price.

There are no manufacturing, returns, or freight costs associated with ebooks; some publishers may apply conversion/formatting fees or overhead associated with ebook production.

Pricing varies, but $12.99–$14.99 is common for a newly released work.

Our example P&L assumes our Great American Novel sells 1,500 copies in ebook form, which is the industry average of 30 percent ebook sales. Note that a significant portion of the total cost of sales in the print column is a shared cost across both formats (the specific title costs plus overhead, which add up to $16,000).

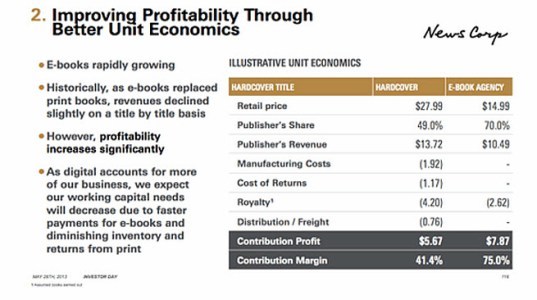

Last year, a slide from a HarperCollins presentation on hardcover-versus-ebook profitability was leaked and made its way around publishing blogs (see below). The slide makes clear what agents and authors have been arguing: the publisher has a higher profit on ebooks, mainly because the author royalty is lower. (You’ll also notice the profitability is being calculated on a hardcover, not a paperback; hardcovers have always been more profitable than paperbacks due to high markup.)

Try It for Yourself

Would you like to run your own P&L? To preserve the formulas working in the background, only modify those cells highlighted in yellow. The spreadsheet will recalculate everything automatically. Don’t forget to change the manufacturing cost when changing sales quantities. Estimate $1 for each paperback unit and $2 for each hardcover unit.

And don’t forget to pick up a copy of The Great American Novel. G. Scott Fitzgerald could really use the royalties.

July 3, 2015

What It Means to Write Realistic Dialogue

If you’re writing a scene with dialogue, it can be tempting to have the conversation follow a very logical flow, what writer Samsun Knight describes as a “call and response” method. But that’s usually a mistake. When people talk to each other, they rarely answer each others questions directly, and non sequiturs are common. Knight says:

In reality, nobody ever talks to anyone else. What speech actually achieves is a communication between one person and that person’s idea of the other. Most of the time there is no difference, no discernible difference, between such verisimilitude and the truth. But the best dialogue will manifest this disparity in subtle, slender ways. It will show how, in speaking, we fail to speak.

Read more about Knight’s insights into realistic dialogue in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin.

For more writing inspiration:

Jennifer Egan: I Knew

Spencer Hyde: Find Your Voice

Or review the latest Glimmer Train bulletin

July 2, 2015

How Self-Published Authors Can Distribute to Libraries

iStockphoto / padchas

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post from Porter Anderson (@Porter_Anderson) explains the terms of a new program—a partnership between Library Journal and BiblioBoard—to help distribute self-published ebooks into the library market. My own self-published book, Publishing 101, is enrolled in the SELF-e program.

The problem self-published authors have run into at libraries has been a lot like the problem they run into at bookshops: no way to break through the barrier of mainstream competition, no way to stand out.

Many librarians are eager to offer self-published material to their patrons, but with some estimates suggesting that as many as 600,000 indie titles are being launched per year in the United States, no one has time to read those ebooks and sort the good from the rest.

SELF-e can’t help you in the bookshop. But it can put your ebook into libraries.

SELF-e can’t help you in the bookshop. But it can put your ebook into libraries.

SELF-e offers the independent author a chance to put his or her ebooks in front of librarians at the state and/or national level. Most importantly, when those librarians get their chances to peruse these ebooks, they’ve been vetted, carefully evaluated and selected by Library Journal.

Library Journal is best known as the national publication for the library community. It not only covers issues in the business but also generates reviews that librarians depend on in making choices for their collections.

I’ve agreed to work with SELF-e as a client of my Porter Anderson Media consultancy, so I can help get the word out to writers for exactly that reason: This is a new, national-class service that promotes independent authors at no cost to them and in a critical discovery forum that previously has been out of reach to indies.

One key criterion for me: This is available not only to US authors but to anyone, anywhere, writing in English.

If this is all news to you, don’t worry, you’re not behind. Only last weekend were attendees at the American Library Association’s annual conference in San Francisco getting demos of how SELF-e works for them on the library side.

Let’s take it step by step. I’ll give you the basic details of how this works, and then will watch the comments below for your questions.

What Is SELF-e About?

From Library Journal’s SELF-e

At the Self-e website, be sure to review Is SELF-e Right For Me? This gives you several criteria to consider, including:

You must have the e-rights to your book.

SELF-e will not pay you a royalty when your ebook is checked out by a library patron. It costs you nothing to get into this arena for discovery but it also will not pay you in royalties.

The way SELF-e works financially is that participating libraries subscribe to its services in order to gain access to its curated collections of independent ebooks. The costs of running the program, then, are borne by the libraries.

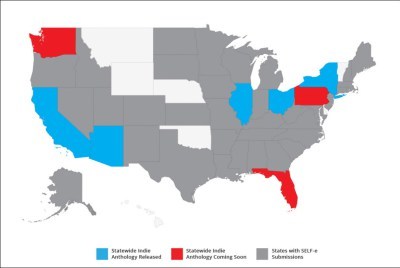

On this page, you can see where in the States authors already are active in submitting their ebooks. You can also see where “Statewide Indie Anthologies” are being released or coming soon. Here’s what that means:

When you submit your ebook to SELF-e, you can elect to automatically be included in your Statewide Indie Anthology. Everyone, in other words, can have his or her work made available to local libraries, and this is a big help to librarians who for years have had no good channel for submissions from local authors.

You also can opt to be considered for the Library Journal SELF-e Select, the collection that is curated and offered to libraries nationwide. And in case you’re wondering, there are more than 9,700 library systems in the United States today.

When you’re ready, here is the basic submission page.

When you’re ready, here is the basic submission page.

Side note: You’ll notice you can submit your work as part of a contest currently underway for ebooks submitted to the program. If you’d like to be entered in the four-genre competition, start on this form—watch for the “Winner” badge on the upper left.

The process of submission is quick (15 minutes), and easy to follow.

The way ebooks are displayed by the program to librarians is via the work of BiblioBoard, which specializes in digital resources for libraries. BiblioBoard’s work is utilized by close to 2,700 libraries and reaches some 30 million patrons.

Let me touch on a couple of questions that I’ve heard from authors about SELF-e.

What the Fine Print Means

SELF-e’s terms of agreement are found on this page. I urge any author considering the program to read them, of course.

Some authors have concerns after reading the first entry, the “Grant of Rights.” The legal language can be a little daunting, naturally, so I asked Library Journal’s vice-president and group publisher, Ian Singer, how we could boil down just what kind of license an author is granting to SELF-e in order to participate.

Singer says, in response:

Library Journal SELF-e selected titles may be purchased only by public libraries. That’s the “exclusive nature” of the license grant we seek. As there is no payment to authors for the selection or promotion services Library Journal renders, Library Journal needs a license—which is non-exclusive, meaning that an author can distribute to public libraries or any other wholesaler, distributor, retailer.

Another more specific concern I’ve heard seemed worth putting to Singer. Let’s say that your ebook goes into library collections thanks to being in Library Journal SELF-e Select, and library patrons flip for it. They’re checking it out right and left. Hottest thing since Beatrix Potter. Then a major traditional publisher gets in touch with you talking about a nice-sounding contract. But, of course, the publisher wants that super-popular ebook to come back out of those libraries. Can you get back out of SELF-e?

Singer:

At any time, an author can request his/her title(s) be removed from a Library Journal SELF-e selection module.

So yes, you can get out of the arrangement at will. The terms provide Library Journal with 180 days to get a title out of circulation, allowing libraries that may have entered it in their collections to remove it.

Who Else Is Participating in the Self-e Program?

Elaine Russell

Meet Elaine Russell, whose Across the Mekong River is not only in the new Library Journal SELF-e Select national collection but has been tagged as a “highlighted” title by the evaluators: highest honor. Russell tells me that she heard about SELF-e through David Vandagriff’s Passive Voice blog and found the submission process very easy.

One thing that makes Russell a good fit for library exposure is that she has ebooks for readers “from children’s and YA to adult,” an unusual range that librarians can appreciate.

“I began writing about 20 years ago after a career in environmental consulting,” she says. “A number of my short stories and the first Martin McMillan novel were traditionally published. But as the publishing industry changed and contracted, I grew frustrated and impatient with the difficulty of getting traditional publishers for my other works. … I am still open to traditional publishing, but I don’t regret my choice to self-publish.”

Whether authors today are found working in libraries as much as they once were for research (Russell still does research at libraries), or simply hold a special place in their memories as their first big contact points with the world of books as kids, the logic of the library patron base as a hub for author discovery makes good sense.

SELF-e is offered as a discovery channel for self-publishing authors who, for the most part, have had no way to reach this broad patron base before. If you feel it’s right for you, it’s ready for your submission. And if you’d like to drop a comment or question here, please do.

July 1, 2015

5 On: Nathan Bransford

In this 5 On interview, Nathan Bransford discusses (among other things) the ongoing emphasis on author platform, publisher and author marketing responsibilities, and in what way being a literary agent influenced his writing.

Nathan Bransford (@NathanBransford) is the author of How to Write a Novel (October 2013), Jacob Wonderbar and the Cosmic Space Kapow (Dial, May 2011), Jacob Wonderbar for President of the Universe (Dial, April 2012), and Jacob Wonderbar and the Interstellar Time Warp (Dial, February 2013). He was formerly a literary agent with Curtis Brown Ltd. and now works in finance. He lives in Brooklyn.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: You ask your readers in one of your blog posts whether they would choose to have commercial success (and make “bazillions of dollars” from their writing) or win a major award and be widely respected (but make very little money). Which would you choose?

NATHAN BRANSFORD: It depends on the day, but I think I’d go for mass appeal rather than critical acclaim. I’d rather a large number of people like my book than a small number of tastemakers.

Before writing Jacob Wonderbar and the Cosmic Space Kapow, you’d written another novel you said didn’t work out. Was it also a middle-grade novel—is that the genre you’ve always automatically gravitated to as a writer?

Before writing Jacob Wonderbar and the Cosmic Space Kapow, you’d written another novel you said didn’t work out. Was it also a middle-grade novel—is that the genre you’ve always automatically gravitated to as a writer?

No, it was a science fiction novel for adults. I don’t think I’ll always write science fiction, but for some reason the ideas I’ve gravitated to the most have been science fiction. Maybe it’s because I’m a lazy researcher and with science fiction you get to make everything up!

How did your experience as a literary agent influence how you write? Do you think about editor reactions and marketability as you’re writing (and write to those concerns), or are you able to be fully and freely creative?

Being an agent definitely influenced me, but probably in the opposite way people might think. Because of my experience I knew to not worry about editor reactions and marketability, because you can’t predict what people will think about your novel, and you certainly can’t predict what the trends will be a year or two in the future while you’re writing a novel. All you can do is to write the best novel possible and let the chips fall where they may.

You’ve said, “There’s that old saying: ‘I don’t like writing, I like having written.’ I’m definitely one of those types of writers.” I recently used that Dorothy Parker quote myself in “Writer’s Lament: O’ Writing!,” as an illustration of writing having become, for many, a special kind of torture. It’s something we probably don’t anticipate when we start out—when writing is still (and only) fun, creative, freeing, and an invigorating use of the imagination. When did it become, for you, not a purely entertaining activity, but instead, “I don’t like writing, I like having written?”

I wouldn’t say it’s always torture, and I do think writing a book is fun on the whole; it’s more that, at some point when you’re writing a novel, the initial heady rush that greets a new project will wear off, and it eventually starts to feel more like work. That usually hits me when I’m fifty to seventy-five pages in, where it starts getting hard to keep the plates spinning and I start confronting some of the serious challenges that come with an interlocking plot and pushing things forward. It gets hard and challenging (especially the editing—oh the editing, MY GOD, THE EDITING!), but it’s so gratifying when it’s finished.

I’d like to use your own blog against you again. Melissa Grey (@meligrey), author of The Girl at Midnight, outlines in a guest post on your website the five things she learned while writing her debut novel. What five things did you learn while writing Jacob Wonderbar?

Trust your instincts.

If you don’t have fun writing it, they’re not going to have fun reading it.

Don’t listen to the “Am I crazies,” as in, “Am I crazy to be spending all my weekends writing this book when I have no idea whether it’s any good or not?” Whatever happens, you’ll be glad you wrote it.

Make sure the reader sees your characters’ best and worst qualities.

When in doubt, add space monkeys.

5 on Publishing

One of the first pieces of advice industry professionals like to give writers, as if it isn’t a given, is “First, write a good book.” The lesson: the writing is the thing. Is it fair, then, to insist that authors be or become active on social media when some of them, if not many, may not be good at it? It can probably be argued that a good book will sell with or without the author’s social media presence, but one might also argue that those who aren’t good at social media could actually lose a sale here and there, or alienate potential readers. “Gee, I was going to buy The Lovely Parade, but I looked at the author’s Twitter feed and the guy is a snooze.”

It behooves all authors to think about what they can do to help sell their book. That has always been the reality of the book business—some of the most beloved authors in history also happened to be fantastic self-promoters.

That said, social media is just a tool; it’s not the be-all and end-all. Instead of trying to do every single thing to promote your book and not doing any one thing well, do what you like the most and you’re best at. If you’re great at social media, then do that. If you’re a great networker, do that. If you have media connections and can generate attention that way, do that.

All authors need a web presence, and I think, given the time involved, social media has significant bang for the buck. But at the end of the day, it’s your book and it’s your life, and you don’t have to have a Twitter account. Do what you think is best.

Jane Friedman wrote in a recent blog post,

One of the growth areas you’ll find here [in traditional publishing] are no-advance deals and digital-only deals that offer a low advance, if any at all. Such arrangements reduce the publisher’s risk, and this needs to be acknowledged if you’re choosing such a deal—because you aren’t likely to get the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution.

What’s the least an author can or should expect, even in these not-so-good-case scenarios?

I think it’s a case-by-case decision, but the basic questions authors should be asking themselves (and asking themselves honestly), are:

What is this publisher doing for me that I couldn’t do, or don’t want to do, myself?

Am I comfortable with what I’m giving up to make that happen?

I hesitate to make any hard and fast rules because everyone’s situation is different. But ultimately you have to decide what’s the right course for your book.

We hear a lot about writers being rejected by agents, but obviously agents are also rejected by publishers they hope will accept the work. Will you take us through what the process was like for you (or is like for an agent) to sell a book that took more than one communication with a publisher? Did it start with an email, a phone call, lunch? And where did it go from there?

The lunches and networking are ongoing. It helps to get a sense of editors not just in terms of their taste but also as people, so you can get a sense of what they might like. I had a huge spreadsheet with every editor in publishing with the genres they edited and what they were like as individuals, which I consulted when drafting submission lists. Whenever I had lunch with an editor, I would update it with that information.

Every book was different, but I’d come up with a submission plan and generally email editors the book and pitch letter, and then follow up with whomever I didn’t hear back from.

Hopefully you have a quick offer, but if not you move down the list of editors.

Publishers want authors to have a platform. It stands to reason, then, that agents will also want authors to have a platform. Would a fiction writer without a niche-market message (and, therefore, probably without the same kind of platform a nonfiction writer might have) simply add in the bio section of the query letter, “I have a Facebook account with X number of friends, a Twitter account with X number of followers,” etc.? If the numbers are low, is it better to not mention the accounts at all?

And what if a writer has instead managed to prove a different promotional skill, such as writing and sending press releases and securing interviews and book reviews? Should that be included in a query? Would it be valuable to an agent and/or editor?

I think it’s really important to think of a platform beyond social media and not to overthink it when it comes to fiction especially.

A platform is a rough combination of your authority as an author (whether your expertise or your credentials) and the number of eyeballs you can summon to read your book to give it an initial boost. That doesn’t have to be through social media. If you have a fan base through some other platform, if you are well-connected, if you are active on a conference circuit, a platform can take many forms.

But you don’t need a platform to sell a novel. You really, really don’t. It can help, but at the end of the day it’s the book that counts. That’s not a platitude, it’s really true.

So yeah, if you don’t have a platform, don’t try to convince an agent you have one, and don’t apologize for not having one. Just pitch your book.

And if you do have a platform, mention it, but don’t belabor it. The book is still by far the most important thing.

You’ve said, “I don’t know that publishers have quite cracked how best to market books in the new era and rely a great deal on old methods (such as sending out advance copies for review) that perhaps aren’t as relevant as they used to be.” Why do advance copies not work, and how would you recommend publishers market books in this era?

It’s not that advance copies can’t work, I just don’t know that publishers always think about them in a strategic way for each individual book. I’ve heard horror stories from authors where their publisher basically sent out 100 advance copies to their same old advance copy Rolodex and called it a day.

Russ Grandenetti from Amazon had a great quote in a New Yorker article last year where he basically said that in an era of self-publishing and book abundance, it’s the publishers’ job “to build a megaphone.”

In the old bookstore world, it made sense to focus your marketing activities around a few books that were at the front of the store (which publishers pay for), to secure reviews (i.e., sending out advance copies), and to essentially take a flyer on the rest of your list and drop them into the ocean to see what happens. But now, with the Internet and e-bookselling, publishers are competing against all media, and without a physical bookstore, book buying is no longer a zero-sum activity.

I don’t have all the answers when it comes to marketing, and there are some publishers who are doing some interesting and innovative things, but it seems to me that publishers could do a better job of utilizing their brands in an era where being a traditional publisher is a true differentiator. Instead, many of the major publishers are divided up into myriad imprints that don’t mean much to consumers.

And ultimately it’s a mindset shift. I’m not sure I understand why publishers would acquire books they don’t intend to market well. Authors can’t do it all.

Thank you, Nathan.

June 29, 2015

How Authors Can Evaluate Hybrid Publishers

This week, I’m a guest on Beyond the Book, a podcast series on the business of writing and publishing. Chris Kenneally and I discuss the growing field of so-called “hybrid” publishers, and how authors can smartly evaluate them.

A brief snippet from what I had to say:

A lot of authors right now, or at least the trend that I’m seeing, is they think that they can design their own covers or use templated interiors. I think that is OK for some projects. But if a hybrid publisher is really just slapping on a template cover or design, and they’re not really going through a formal design process, you have to ask, what is [it] that you’re paying for, if not for something that’s truly custom and suited to your work?

I know that there are a range of publishers—it’s kind of like a sausage factory. (laughter) They’re just pushing the books through this templated system, rather than … treating each book as a unique product in itself.

Listen to the 20-minute conversation on hybrid publishers, or read the transcript of our conversation.

June 25, 2015

The 4 Hidden Dangers of Writing Groups

photo by ToGa Wanderings / via Flickr

Note from Jane: Last week, I ran a comprehensive guest post on how to find the right critique group. To help add to the nuance and complexity of that issue, I’m happy to feature the following guest post by Jennie Nash (@jennienash), the Chief Creative Officer of Author Accelerator.

Writers love the idea of writing groups. Writing is, after all, a very lonely pursuit. You sit alone in a room wrestling your ideas onto the page, struggling to fend off the constant attacks of doubt. Your regular friends probably don’t quite get what you are doing and can’t help. So it makes perfect sense to join other writers who can help you navigate the joys and sorrows of the creative process.

Unfortunately, the reality of writing groups is far more complicated than that. Underneath the good intentions there are serious dangers lurking.

In my work as a book coach I often see the damage that writing groups do, and it is not benign. Writing groups can cause fatal frustration, deep self-doubt, and sometimes years of wasted effort. In this post I’m going to outline the most common dangers of writing groups, and will also propose some ways you could improve your group to give you more of what you need—and less of what you don’t.

To illustrate my points, I’m turning to wisdom shared in Creativity, Inc by Ed Catmull, President of Pixar and Disney Animation. In this book, Catmull shows the many ways that the powerhouse studio has managed creativity, and in the process produced some of the most resonant and beloved stories of our time. He talks about the concept of management on a really big scale—department hierarchies and multi-million dollar movie projects—but the fact of the matter is that we all must manage our own creativity if we are going to do any good work, and his wisdom applies to all of us.

To illustrate my points, I’m turning to wisdom shared in Creativity, Inc by Ed Catmull, President of Pixar and Disney Animation. In this book, Catmull shows the many ways that the powerhouse studio has managed creativity, and in the process produced some of the most resonant and beloved stories of our time. He talks about the concept of management on a really big scale—department hierarchies and multi-million dollar movie projects—but the fact of the matter is that we all must manage our own creativity if we are going to do any good work, and his wisdom applies to all of us.

1. No one tells the truth and no one really wants to hear it.

Most writing groups tiptoe around glaring weaknesses in the work being shared and sometimes tell outright lies about it, because they don’t want to hurt people’s feelings. All the writer hears is praise or vague criticism that isn’t very actionable, and so they assume that what they are writing is solid (if not awesome) and they plow on creating fundamentally flawed work.

Praise is wonderful—it feels good to hear it—but it is not very helpful for the writer committed to writing a book that engages the reader. Writers must find a way to welcome criticism, even harsh criticism, but writer’s groups tend not to foster this skill, and as a result, no one grows, no one learns, and people become deluded about their work—believing it to be better than it is.

At Pixar, truth-telling is a central part of the creative process. As Catmull writes:

In the very early days of Pixar, John, Andrew, Pete, Lee, and Joe made a promise to one another. No matter what happened, they would always tell each other the truth. They did this because they recognized how important and rare candid feedback is and how, without it, our films would suffer. Then and now, the term we use to describe this kind of constructive criticism is “good notes.”

Before we get to the good notes part, let’s look at the promise to tell the truth. That’s the critical thing a good writers group needs—not an implicit promise, but an actual commitment. Every single member of your group needs to understand the promise about telling the truth, believe in it, commit to it, and welcome it when it is their turn in the hot seat. This starts with a shift in mindset, which Catmull describes beautifully:

Naturally, every director would prefer to be told that his film is a masterpiece. But, because of the way [our group] is structured, the pain of being told that flaws are apparent or revisions are needed is minimized. Rarely does a director get defensive, because no one is pulling rank or telling the filmmaker what to do. The film itself—not the filmmaker—is under the microscope. This principle eludes most people, but it is crucial: You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your idea, you will take offense when they are challenged. To set up a healthy feedback system, you must remove power dynamics from the equation—you must enable yourself, in other words, to focus on the problem, not the person.

Try the following fixes for your writing group: