Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 142

October 12, 2015

How Authors Can Find Their Ideal Reading Audience

by Dan Machold | via Flickr

Today’s guest post, from writing coach and author Angela Ackerman (@angelaackerman), discusses techniques for identifying and connecting with your target reading audience.

Today’s writers have never had a more global reach; ebooks and digital distribution have made it easier for authors to find readers in other countries as well as their own.

Of course, the potential of a global readership only matters if an author knows how to access it, and this is where many marketing plans fall short. Given the endless buffet of books to choose from, it can be hard to get a book the attention it needs.

The Benefits of Fishing with a Smaller Net

It can be tempting for an author to rig a marketing freighter with big nets and start trawling for a readership. But your goal is not to seek out any old catch you can. To get the most out of your marketing efforts, you want to attract a specific type of reader suited to your book. This means you need to know who they are and where they hang out.

To Answer the Who, We Need the What

When it comes to understanding which readers are most likely to enjoy your book, you first need to look at what makes your book special, and this means thinking beyond genre, which is simply a guidepost to a readership. You must answer this question:

What makes my novel stand out from all others like it?

Let’s look at an example. The romance genre is by far the biggest. Yet, a reader of a steamy romance featuring a modern-day female pirate captain may not be as interested in a romance between an dog breeder and animal rescue worker who meet on the show dog circuit.

But you know who would read that romance? People who love dogs. Dogs, show dogs, the world of professional dog breeding—these are the unique elements that will attract a specific type of romance reader to this book. Once you understand the what, you know the who.

Authors tend to suffer book blindness when it comes to our own work. It can be difficult to see what sets your novel apart. If that special quality seems elusive, outsource and ask a few readers what really stood out to them as they read. Or, figure it out on your own. Here are a few ideas on what form this unique element might take:

A theme or cause that commands attention: PTSD among war veterans, the tipping point of pollution and waste, terrorism on home soil, homelessness, cyber-bullying

An area of interest: boating, falconry, ghost-hunting, ranching life, UFO sightings, tango dancing, life during WWII

An intriguing character talent or skill: martial arts, empath abilities, archery, songwriting, eidetic memory, mentalism

A specific passion or hobby: nonprofit work, sustainable living, medieval live-action role-play, coin collecting

A stand-out element or concept: ciphers and code-breaking involved in a murder mystery, a rash of out-of-body death experiences taking place in a small town, a cult that practices cannibalism

Another clue to this special element is your research for the book. What information did you need? What websites are in your bookmarks? Or, what personal knowledge do you have that made research unnecessary? Often the special element is something you have a personal interest in, which is why you chose to include it into your story.

The Next Question Is Where

Once you know the types of people suited to your book based on a standout element, you need to figure out how to find them and which people are influential with this particular audience (businesses, bloggers, other authors, and organizations, to name a few). Ask yourself:

What groups or organizations are involved in this special area?

What businesses tie into this element?

What blogs exist that tackle this interest or idea?

Who is talking about this concept or thing online?

What movies or TV shows focus on this element?

What products cater to people interested in this special thing?

Armed with a list, head over to Google and search for leads. Think of keywords that will likely pull up big sites. Add +blog or +forum or +club or whatever gathering place or group you think might exist. If you need help with figuring out search terms, try Soovle. It will start with your subject of interest and show you the most popular search terms used at Wikipedia, Bing, Yahoo!, YouTube, and more.

Also, find books like yours, written by authors who you can possibly collaborate with in the future for marketing, and investigate how they connect with their audience and where. Chances are their readers are a good fit for your novel. If you need help finding books like yours, try Yasiv, which provides an image web of books Amazon users typically buy together. If your book is quite new and doesn’t have a lot of connections yet, find one like it and use that title as the reference point. Here’s one of mine so you can see how it works:

When looking for an audience, try also thinking beyond books. If “dragons in modern society” is your standout element, brainstorm what other businesses, artists, and organizations cater to this interest group (dragon lovers). Book promotion is great, but cross-promotion with a sister-industry can open up new audiences. In the case of dragons, there’s dragon fantasy art, dragon-themed merchandise (clothing, collectibles, games, etc.), movies, and TV shows—I even found a link to a dragon museum. And running an advanced search on Twitter shows people, hashtags, and groups that are actively talking about dragons.

Suddenly audience research gets a whole lot easier, doesn’t it?

Now Comes the Hard Part: Connection

Once you find potential audiences and influencers, you have to actively do something to reach them. And to be honest, this is the part where 80 percent of authors drop the ball. The reason is simple: connection takes time.

As we all know from the barrage of “buy my book!” promotions online, the direct sell doesn’t work. It’s white noise; we see so much of it in our Twitter and Facebook feeds, we just skip past it. And yet still authors do this spaghetti promotion day in and out because they’re looking for the shortcut solution to sales. All they’re really doing is wasting time—time that could be put into building a community.

Connection is simple: find like-minded people and start conversations. Ask questions. Comment, add value, entertain, discuss your common interest, share relevant links, and just be present and authentic. Choose the social media platforms, reading sites (like Goodreads), blogs, forums, and other communities where your audience hangs out and make it about them, not you. In other words, don’t treat them like your meal ticket. Get to know them. Show you care. Add to the community. Then, when a natural opportunity arises, share that you are an author, and when it sparks an interest, share your book.

With influencers, give first. Share their posts and links, work at raising their profile (and use their online handles on social media so they know). Leave comments and start conversations that show you are interested in helping them grow. Usually reciprocation happens naturally, and when the time is right, you can approach them about possible cross-promotion opportunities.

It really is that simple—and hard. It takes time, and a person has to be genuine. But ask anyone who is successful at this and she will tell you building a community that cares and invests in one another far outweighs costly ads, spaghetti promotion, or other tactics.

The whole reason we write is to connect with people in a meaningful way, right? So, be yourself, enjoy the people you get to know, and trust the rest will follow.

The whole reason we write is to connect with people in a meaningful way, right? So, be yourself, enjoy the people you get to know, and trust the rest will follow.

You can visit Angela’s site, Writers Helping Writers, or check out her new project, One Stop for Writers, a library and brainstorming tool for authors.

If you’re interested in exploring this topic further, you might also enjoy this post: Finally, A Social Media Marketing Strategy That Puts You Right in Front of Your Target Market.

October 9, 2015

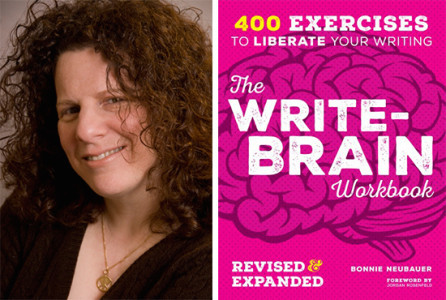

Strengthening Your Creativity Muscles: Q&A with Bonnie Neubauer

When I was an editor at F+W Media from 1998–2010, I acquired hundreds of books, mostly for the writing reference shelf. In the early 2000s, I had the good fortune of meeting Bonnie Neubauer, who specializes in writing exercises and creativity, and we worked together on a very special project called The Write-Brain Workbook. It’s a full-color book of 366 one-page writing exercises, each page uniquely formatted and designed. I’ll never forget working on that project because it was an enormous undertaking; we ended up assigning pages to multiple designers at the company.

But the effort was worth it; the book has been successful enough that Writer’s Digest has just released a second edition on its ten-year anniversary. I took the opportunity to connect again with Bonnie to discuss her own creativity practices and goals, her favorite means of gathering writing prompts, and myths about creativity.

JANE FRIEDMAN: Congratulations on the ten-year anniversary of The Write-Brain Workbook! I’m sure over the years you’ve received a lot of feedback from writers about the book’s exercises. What patterns have you found in people’s response to the book?

BONNIE NEUBAUER: Thanks, Jane. It’s beautiful and, after ten years of wishing, it now has workbook-size pages so you can truly write right in the book.

BONNIE NEUBAUER: Thanks, Jane. It’s beautiful and, after ten years of wishing, it now has workbook-size pages so you can truly write right in the book.

Most of the feedback I’ve received over the years comes from writers as well as teachers. Often the letters and emails take the form of a confession about not writing or the fear of writing, followed by a heart-felt thank you for how the exercises in the book have helped liberate them. Every time I read one of these notes, my eyes well up because I know how great it feels to unlock something hidden within or unleash a part of yourself that had been blocked.

I frequently hear from writers who are very visual learners or who have learning challenges, especially ADHD. They tell me that it’s the only book that works for them. I guess it will come as no surprise that I, too, have quite a short attention span. I am an auditory learner, however, and that’s where the word-play and bad pun titles of all the exercises come from.

My favorite feedback, however, always comes in my writing workshops. During an exercise, when an attendee’s posture changes, her lips curl into a smile, and her pen starts to move really fast, I know that she has discovered or rediscovered the joy of writing. It’s a beautiful thing to witness.

Do you have a daily or consistent creativity practice of your own? What’s it like?

I do my best to do something toward my creative goals every single day. When I miss a couple days, I feel off both physically and mentally. It’s hard to explain, but my anxiety increases, and my patience and concentration decrease. I actually feel like a part of myself is amiss. The closest thing I can compare it to is when athletes (I am not one; I am a computer potato) talk about how their mood is enhanced when endorphins are released through exercise. I get that feeling every day through my commitment to consistent creative expression. Also, it’s never an effort. Taking time away from it is where the effort comes in. It’s a bit hard for me to shut off my creativity. I have to concentrate really hard to keep it at bay. And when it’s time to turn it back on, it usually takes a good portion of a day.

There are two ways to reignite my creativity that work best for me. One is to pull out my Story Spinner, generate a writing exercise, set a timer for ten minutes, and simply write. I usually do three of these unexpected-topic, random idea, timed writings before I feel like I have returned. The other thing I do is clean off my desk. I hate to clean, so it brings out the rebel in me. Before I know it I am shirking that task and doing something that makes me happy. And that something is always creative.

There are two ways to reignite my creativity that work best for me. One is to pull out my Story Spinner, generate a writing exercise, set a timer for ten minutes, and simply write. I usually do three of these unexpected-topic, random idea, timed writings before I feel like I have returned. The other thing I do is clean off my desk. I hate to clean, so it brings out the rebel in me. Before I know it I am shirking that task and doing something that makes me happy. And that something is always creative.

My practice begins every morning in the shower. As the water flows, I let my brain go on a stream-of-consciousness vacation. I don’t force any thoughts or try to direct my brain to solve a problem. Instead, I let my mind relax. By the time my hair is conditioned, I am usually repeating a new idea over and over in my head so I don’t forget it. I keep a white board and marker close by to record these ideas. That sets the tone for the rest of the day. I always carry a notebook with me so I can catch my ideas as close to when they happen as possible.

I believe it’s better to be creative two minutes a day, every day, than to create for large chunks of time once or twice a week. This is how I build and maintain my momentum.

Do you have any favorite exercise or prompt books from other writers—or perhaps other, atypical sources of inspiration?

One of my favorite means of inspiration is to go to library used book sales. Armed with lots of allergy meds—I am allergic to mold and some types of ink—and some huge shopping bags, I head right to the nonfiction sections. I grab older books off the shelf that happen to catch my eye. I flip them open to random pages, and if I see something I like—typically an illustration—I put it in my “to buy” pile. Two shopping bags (okay, I confess, usually three shopping bags) and $25 later I am armed with a ton of inspiration. One recent visit netted a book on hand-weaving, one on noncompetitive activities for youth ministers, a psychological color test, a rhyming dictionary, and a picture book on the history of the telephone—to name but a few of the gems.

Is there a persistent myth about creativity or the muse that you wish you could eradicate?

It really bothers me when people say they aren’t creative. Everyone is, in some fashion. I am just as guilty every time I say I am tone deaf or that I have two left feet and that no one could ever possibly teach me how to sing or dance. I wish, more than anything, that we would all learn how to let go of limiting beliefs, stop comparing ourselves to others, cease worrying about what others think, and just let ourselves go and be free to experiment and play. Oh dear, I think I am showing my age. I sound a lot like a hippie from the late 1960s, early 1970s. But it’s true. If we could see life as a big playground, we’d be a lot happier and probably a lot healthier, too.

It really bothers me when people say they aren’t creative. Everyone is, in some fashion. I am just as guilty every time I say I am tone deaf or that I have two left feet and that no one could ever possibly teach me how to sing or dance. I wish, more than anything, that we would all learn how to let go of limiting beliefs, stop comparing ourselves to others, cease worrying about what others think, and just let ourselves go and be free to experiment and play. Oh dear, I think I am showing my age. I sound a lot like a hippie from the late 1960s, early 1970s. But it’s true. If we could see life as a big playground, we’d be a lot happier and probably a lot healthier, too.

I know you believe that momentum is a writer’s best friend. Tell us what that means.

It’s funny; I was never enthralled with science when I was in school, but some of the terms really stuck with me. Momentum is one of them. It has to do with something growing stronger as time passes. The word conjures up an image of a huge wave that is building with intensity and strength. And I hear its roar, too. For me, momentum is the creative process. Every time you create, you add to its power. The more you create, the stronger it gets. The more committed you are to it, the better you feel and the better you get at it. It’s self-perpetuating. And it’s why I honor my commitment to create every day.

Want to exercise your creativity?

Want to exercise your creativity?Download 5 sample exercise pages (PDFs) from The Write-Brain Workbook.

Or, order your copy now!

October 8, 2015

My First Year of Full-Time Freelancing

In June 2014, after 15 years of conventional full-time employment, I struck out on my own as a full-time consultant and freelancer. I’ve had a very successful first year, increasing my previous annual income by roughly 50 percent.

In the issue of Writer’s Digest currently on newsstand (November/December 2015), I’ve written a feature article on how writers can become their own boss, by reflecting on how and why I was able to make the leap; I also interviewed other freelancers who’ve made the transition within the last few years. As a sidebar, I offer a transparent look at my income, and list the exact dollar figures I earn by source.

Here are a few other things I’d like to share—not in the article—about my experience so far.

1. The Short-Term Pressure to Say Yes and Long-Term Need to Say No

I had about three months to prepare for full-time freelance, when I was still earning a full-time salary but had a definitive “last day” on the calendar with my employer. During that time, not knowing how things would go, I more or less said yes to every potential opportunity, while also proactively looking for a few of my own. For my first half-year of freelance, I said yes, yes, yes to everything or everyone external.

It wasn’t necessarily the wrong thing to do, but it was driven by income anxiety rather than by strategy or what would be an efficient use of my time and energy. It was also driven by lack of confidence that I could succeed and be profitable at things I wanted to pursue. No doubt this is a problem all freelancers have throughout their career: the pressure to take on the paying work you could have right now, rather than invest in something that pays much further down the road.

I have to keep reminding myself that every “yes” to something I’m not that excited about means saying “no” to something else important to me. Of course, over time, as reputation and status grow, you get to call more and more of the shots.

2. Attracting the Right Kind of Work (or Client)

While I was working at F+W Media years ago, the annual budget review meeting was notorious for executives asking, “Can we raise the price on that?” It became tiresome after a while, and I understood the wisdom of it then—but I understand it even better now.

Charging a low price to attract a large number of clients/customers can be less efficient than charging a high price to a fewer number of clients/customers. Price also communicates something about the value of what you’re providing. Obviously, there is a limit to how far you can price-hike before people think you’re deluded or trying to rip them off, and the pricing also has to be informed by the market you’re targeting. (I’m fairly conscious of services provided to unpublished writers who may never see a return on investment and are not exactly pursuing a high-income profession.)

The hard part: I often value my time more highly than many of those who might pay me. Or, put another way, I see the earnings potential in an hour of my time as far greater than what many should pay me or want to pay me. That’s a business challenge I continue to address, but one solution is to be far more specific about the type of work I try to attract.

Also, I like the advice that Michael Ellsberg has offered on this: Look for your happy price, or the price at which you feel happy (not resentful) doing the work.

3. The Accounting, The Accounting, The Accounting

I wish I had done more legwork upfront on setting up proper business accounts, separate business credit cards, and more. I’m only recently catching up on this. Here are the tools I discovered that you could use to help track business expenses and income:

Wave: free web-based accounting and invoicing (will allow you to import transactions from bank accounts and credit cards)

Ally: free online checking (but be careful: they don’t permit business accounts; however, it’s a good way to begin separating out your writing/freelance income and expenses if you’re a sole proprietor)

Chase Ink Business credit cards: these are the credit cards recommended by the Points Guy to maximize rewards

If you’ve experienced the transition to full-time freelance, I’d love to know about your experience and advice in the comments.

October 7, 2015

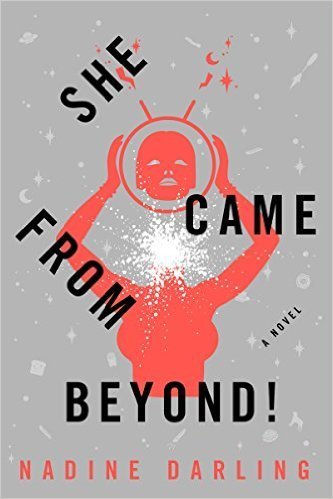

5 On: Nadine Darling

In this 5 On interview, debut author Nadine Darling discusses her revision and query process, blogging, writing with children in the house, and more.

Nadine Darling (@darling_nadine) was born in San Francisco, CA, and really enjoys going on and on about how much the nineties sucked/were awesome. She currently resides in Boston, MA, with her family and too few dogs. She Came from Beyond! (Overlook Press, October 2015) is her first novel.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: You say in your blog profile that you love beautiful books. What title immediately comes to mind when you think “beautiful book”?

NADINE DARLING: Oh, my god, The Shrine at Altamira by John L’Heureux. I read the review in the San Francisco Chronicle while I was laid up in a hospital bed after being hit by a car in 1992. I bought the book in the SF State book shop in 1993, as a senior in high school. Every fucking word is a revelation. There’s such restraint—this incredible restraint—until the end, with this horrible, unthinkable release. I believe that after I read that book I understood writing was inevitable for me, and, I’m sorry, I know that makes me sound vaguely like an asshole. But, that was it. After that it was just a matter of time.

I don’t have kids, and even without them I can have a hard time getting into an uninterrupted (mentally speaking) writing zone. You have seven children, including step-children. What does it take for you to get into a writing headspace, and how do you manage your writing time? Note: I would also ask a male novelist with children this question.

I don’t have time to do shit, ha. I should be in bed right now, actually, but I love you and I drank the biggest coffee, so here we are.

My husband, Ken, and I were watching a documentary a while ago about this photographer who goes to great lengths to set up his pictures—cranes and shit, the perfect light, the perfect everything. And, in one scene, he wants to take this one picture with a four-week-old baby sleeping on a motel bed, and it’s very stylized, the mom is sitting on the bed in a housecoat staring at the baby, and the shot is taken from outside the motel with the door wide open, everything bathed in the neon light of the motel sign. But, every time the baby’s dad tried to lie her down on the bed, she would wake up, crying—she was naked, and it was cold. And, this photographer, this guy who’s used to getting his way, is just standing there, silently seething. So, we’re watching this, and Ken says, “Haha, that baby doesn’t give a fuck about that guy’s picture.”

And that’s as close as I can get to explaining writing when you have kids; they could not give less of a shit about your art. Which is not to say that you can’t find a way to make art while having kids, but it’s on you, completely. No child has ever said, “Hey, write that story, my thing can wait.” Even my step-kids, man. I can explain it to them and tell them why I need time and why I need them to watch the babies or whatever, and they’re still like, “Yeah, where’s the orange juice? Are there any AA batteries? Can you find them?”

Where did the idea for She Came from Beyond! come from?

Where did the idea for She Came from Beyond! come from?

I wanted to write about Oregon, because Oregon is the place of my spiritual birth—and that sound you’re probably hearing is my sister, who lives in Oregon, laughing her ass off. We’re from San Francisco! One of the most beautiful places on earth. But then I stepped off a Greyhound in southern Oregon, and it was like, oh, okay, I’m home.

I didn’t live in a particularly scenic place, or anything, but there it was, bam. I wanted to write about living there because it was this banal magic. And I wanted to write about my secret dream job, which is being a horror host. I love horror movies, science fictions, all that stuff from the eighties, and I know a lot about it, just from being a nerd and being obsessed. I’ve always loved the idea of hosting some terrible horror movie and having those little bumpers before and after the commercials with comedy and information about the movie and actors. So I gave Easy, the main character, that lead and that life. I was curious about being a celebrity who’s only a celebrity to really lonely sad people—the kind of kid I was, probably. I would die, probably, if I met Tom Atkins from Halloween III: Season of the Witch. That is the truth. Or, like, any of the stars of Creepshow. One of whom was actually Tom Atkins.

And being a stepmom, too, that was something I wanted to explore because it’s so weird. In the best-case scenario, which we actually have, you’re only really asked to be a glorified babysitter, but it goes so much deeper than that. It’s incredibly complex, because you end up loving them as much as you love your biological children, but there’s always these boundaries, and it’s kind of this furious balance. I mean, now, for us, we have it all figured out—but the beginning is very odd. They don’t make handbooks for that shit, man. But they shouldn’t make handbooks for that, because you have to figure it out for yourself, and every case is different.

What about writing challenges you the most, and has the challenge changed over time?

Everything is time, now. Sometimes I daydream about the time I used to have. When I was pregnant with my first kid, I quit my job in my fourth month to try to write a book—a different book—but then I ended up sitting home gaining seventy-five pounds and watching Sex and the City and Gossip Girl. Sleeping until noon, the whole bit. I get so angry at that past-Nadine! That idiot! Now I could write three books in that time. But, anyway, whatever. The main thing I used to struggle with was being distracted, or, I guess, a kind of fear of success. I would sabotage myself when it started to get good because I was freaked out by trying to get an agent, etc. It was easier to not try.

What piece of advice has been most valuable to you as a writer?

No one ever gave me advice, which is awesome because I was enough of a shit as a kid to have done the opposite. I accepted some general advice, though, which, I guess, applies. “Sleep on it,” is good. I try to put distance between me and whatever I’m writing before I share it with someone because good stuff comes to me in the shower and I need to add it. And I always write down an idea right away because my memory is garbage now. My mom always said “everything will be all right,” and that’s one to live by, you know, because you can torture yourself as much as you want about a thing, but in the end you have a choice, and the thing passes and it’s on to the next.

My advice to other writers, though, is to not write when you feel terrible about writing. Not to make yourself write. I mean try, of course, but if you’re half an hour in and you’re miserable, do something else. I’ve never written anything good while feeling resentful of writing. And, the reader can tell, I’m pretty convinced. Nobody wants to sit down and read your struggle-writing. Can you imagine? This is why no one publishes grocery lists. Because if it was a chore, it reads like a chore.

5 on Publishing

Many authors have been wondering lately how beneficial blogging really is, whether they should bother contributing time and writing energy to a saturated blogosphere. As the publication of your book got closer, you decided it was important to become more active online and started a blog. Your posts—and many of them make me laugh out loud at least once (usually more) while I’m reading—range from film critiques to book recommendations to critiques on our own society. They’re posts I think a lot of people would enjoy, but there are a lot of blogs a lot of readers would enjoy—if they would only read them. How effective has blogging proven to be thus far as a marketing tool, and what do you to do attract readers?

Yeah, ha, no one reads my blog. I had some anxiety in the beginning, like, oh, shit, I need a following, what can I do? What is my gimmick?

So, the blog started as a hybrid of book reviews and beauty products. Like, I would review a book and then, in the same blog, some kind of skincare product or makeup that was somehow connected to the book. I reviewed Sarah Blake’s poetry book Mr. West and an OPI nail polish that was gold, because Sarah signs her book with a gold Sharpie.

And, I mean, it was a clumsy concept right out of the gate. I was limiting myself to books which would pair with a beauty product in a way that was appropriate. The book I read right after Mr. West was The Book of Laney by Myfanwy Collins, a book about a girl whose brother was involved in a school shooting. And, it’s a fantastic book, of course, but I couldn’t very well segue from that subject matter to, like, you know, a fucking leave-in conditioner. So, the blog had to evolve.

I can honestly say that I write the blog for myself, which is great because, as I mentioned, no one reads it. I mostly go on and on about movies that were ridiculous to me, and a lot of times I feel as though I’m the only one who feels that way. Like the movie Rudy. People die over that movie, and I was rolling my eyes so hard all through it. It’s like that Seinfeld episode where Elaine is the only person who hates The English Patient, and everyone in the movie theater is crying and she’s staring up at the screen and in her mind she’s screaming, “Die, die, die, why won’t you just die?!” I was pretty much the only person who ever hated Good Will Hunting, basically. I’ve never wanted to punch a movie in the face as much as I wanted to punch that movie in the face. And I live in Massachusetts, now, so that’s a problematic view.

Anyway, I blog what I want with no agenda. No one’s writing me a check for it. You know, yet.

Between the first draft of She Came from Beyond! and its submission to your agent, how many revisions would you say the book went through, and how many people read it to offer constructive feedback and aid in the revision process?

Zero. And that doesn’t mean I’m any sort of prodigy or whatever, because I’m not. I wrote about things that I know and that I understand. I didn’t have to research a character’s mental illness, because I grew up neck deep in it.

I was on a panel of debut novelists last week and we got this same question from the audience. I’m sitting next to Cecily Wong, who wrote Diamond Head, which is about four generations of a Chinese/Hawaiian shipping dynasty, and she’s saying, yeah, this was twenty or more revisions, easily. But, there I am, with no revisions. Because, look, no one’s going to be up my ass if I mistake the year C.H.U.D. came out, right? Or Chopping Mall? I sort of had the luxury of winging it to a great extent, so I can’t sit here and be like, yeah, damn, it really sucked having to look that up on my phone—those were precious moments I’ll never get back.

My book is based in the present, and the situations were situations I felt really comfortable with. You know, therapists, family members being committed—I’m your woman. I’m the expert on that type of dysfunction.

I probably had concerns about writing a full-length manuscript, if only because I had had my best luck with short stories—I think there was a certain fear of writing ten thousand words and then just being abandoned there with something that was either too long or too short. I mean, what could you do? Pad the shit out of it? Add a long lost twin or something? This was unwarranted, for the most part. Sometimes I think anxieties like that are just ways for your brain to scare you out of doing a thing you really want to do. Because, honestly, if we dwell on the scariest, most negative possibilities of anything, we wouldn’t even be able to get out of bed in the morning.

It’s sort of embedded in me from childhood the idea that there’s secretly no point in doing anything, and that’s the absolute worst. You have to fight against that feeling really hard because if you don’t it can become your reality. It’s so easy just to settle back with that Eeyore feeling—”Oh, woe is me”—and not take responsibility for yourself and your opportunities.

All of the changes from my editor, except for misspellings and whatever, were suggested edits, and all of them made a great deal of sense to me. I think there was only one suggestion I didn’t end up taking, and even then I understood where she was coming from. So, basically, a hard copy of the manuscript came back to me with all these little notes—some of them very simple, like “?” or “I love this”—and then I went into my manuscript on the computer, tracking changes, and fixed things, switched words, whatever.

This, surprisingly, was the part of the process that gave me the most anxiety, but I can’t say why because I’m not sure why. After she sent me the annotated manuscript, I think I set it aside and didn’t touch it for a week or two weeks. I definitely thought it would be a stressful experience, but avoiding it was also stressful. Finally, my husband opened the envelope and flipped through the pages and said, “There’s barely any notes. Can you just please get this over with?”

So, I looked, and he was right, and I think I knocked it out in a few hours. There were a couple of places in which the editor wanted padding—more explanation, I guess—and two characters actually became one character, which, in the end, seemed so obvious. After that it was just a matter of writing acknowledgements and going over the first-pass pages very carefully, looking for typos. We had a proofreader, but it was just extra security to have as many eyes on the page as possible.

Even the best book can never find an agent if the query letter fails. How much work went into your query letter, and are you willing to share the letter that got the agent?

I would, but I don’t think I have it anymore. My husband wrote it; he really has a gift. He’s a writer, too. He really understands what it takes to turn a head—just switching a word, or the position of the word; and your query letter has to be in the writer’s voice, because it’s really the first taste of your writing that an agent sees. It has to have the energy of the book. You can’t write a fun book and have a tight-ass query—it’s too much of a leap—and you need to get that manuscript into as many hands as possible. Also, you know, if you can, in your letter, explain how your book can be sold, what its tagline is—that just makes it so much easier for the agent.

So Kenny looked at what I had written—the bio, the summary, the book itself—and he remixed it all into this perfect letter. And it was so much better than anything I could have done, because, at that point, I think I was too close to it. I was going to overthink it, and it was going to sound robotic, and whoever got that letter was going to smell my fear. I mean, I guess that advice—have your husband do it—isn’t the best or the most realistic for most people, but I understand the concept of the query a lot better now. It’s sort of like, don’t get cute. If something feels really stilted and uncomfortable, it’ll read even worse.

What’s your opinion of book review sites that charge a fee? (This includes Kirkus.)

I didn’t even know it was a thing until recently, and that was after Kirkus reviewed SCFB!, which was one of our biggest What the hell?! moments, as I don’t think any of us really expected it. I don’t know that much about it, so I don’t want to be a blowhard about it. I would assume—again, without knowing anything—in theory, that it might be sort of a boon for a self-published author in terms of publicity and credibility, especially with a site like Kirkus.

Now I’m curious, actually, and I want to look up the prices of lesser known sites! I mean, for what it’s worth, having our Kirkus review opened up a lot for us, at the very least in terms of confidence. I wrote letters to people asking for blurbs with a lot more ease because including the link for the review was kind of a veiled way to say “Hey, this is a thing” and “I’m not a stalker.” (Which is not to say that writers who self-pub are stalkers or not a thing.)

And it was the beginning of something, now that I think about it. My agent, Sarah, called me when we got the Kirkus review, and she was crying. And then I was crying. But we’re both Pisces, so that’s not really a huge thing for us, crying.

What thoughts do you have as your first novel publishes? What excites you the most, and what concerns you the most? How does the reality of publishing a novel compare to the rough-draft-period fantasy?

I don’t have a hell of a lot of concerns right now, to be honest, because shit’s gonna happen whether I worry about it or not. As I write this, I have a launch in like five days, and I have to buy a big thing of OxiClean for an audience-inclusive comedy bit. Then there’s a tea party in New York. And the Boston Book Festival. And a thing at Tufts Library. And a thing at Papercuts J.P. in Jamaica Plains. And then a thing at Porter Square Books.

That’s all exciting, and it’s going so quickly that sometimes I have to stop and say to myself, “This is happening.” It’s as good as or better than the fantasy, mainly because I’m choosing to say yes to as much as I possibly can, and when stuff is unexpected, we’re not getting taken down, because, look, who’s gonna give a shit in a hundred years that the books were a week late from the printer? What are you gonna do about it, make everyone around you feel like garbage? Have a coffee or something, take it easy. When my kid gets frustrated and throws herself on the floor about something, I’m like, “Okay, but now what?” And life is just a constant variation on that, right? So, you’re on the floor, but now what?

Thank you, Nadine.

October 6, 2015

Before You Launch Your Author Website: How to Avoid Long-Term Mistakes

Note from Jane: This Thursday, I’m teaching a 2-hour live online class on how to get your author website up and running in 24 hours or less using WordPress. Even if you can’t attend live, you’ll get access to the full recording, plus all Q&A. Find out more and register.

As I’ve written repeatedly in the past, an author website is a long-term investment in your publishing career. It should be something you own and control, and that grows with you from title to title. To accomplish that, here are three ways to avoid long-term pain and suffering if you’re preparing to establish your first author website.

1. Buy a domain based on your author name, not your book title.

Let’s assume you plan to write more than one title during your career. You don’t want to be in the position of either creating an entirely new website when your next book releases, or entirely redesigning your site because it’s focused on just one title.

Authors build brand equity with each new title they release. A website built on your author name helps develop name recognition with readers and the industry—as well as search engines!

Possible exceptions

Sometimes an author releases a book that’s meant to become a recognizable brand unto itself. Pottermore is an example of that—although keep in mind that series didn’t have its own website until quite late in the game.

Other times, an author or publisher wants to develop a unique online experience of the book. Far From the Tree by Andrew Solomon has its own site here—it offers special functionality and interactivity that would be hard to incorporate into your average author site. (But note that the author site is not replaced by a book-specific site. Here’s Andrew Solomon’s author site.)

Honestly, though, few books benefit from this type of treatment or even merit it. It takes tremendous marketing effort to see a book-based website take off; if you’re not planning to invest years in it, focus on launching or improving your author website instead.

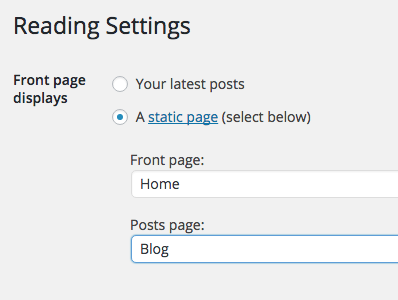

2. If you’re not going to blog, choose the right platform or theme, and modify your settings accordingly.

Two of the most popular and free website-building platforms for authors (Blogger and WordPress) tend to put blogging front and center. But most authors either aren’t actively blogging and/or shouldn’t focus their homepage on blog posts.

Two of the most popular and free website-building platforms for authors (Blogger and WordPress) tend to put blogging front and center. But most authors either aren’t actively blogging and/or shouldn’t focus their homepage on blog posts.

The good news is that it’s easy to modify WordPress site settings to disappear the blog altogether. (Go to Reading Settings, and under Posts page, choose —Select— if you won’t be blogging.) Also, you can look for a theme that makes it easy to build a beautiful homepage focused on your books.

I don’t recommend using Blogger for author websites unless you intend to be very blogging focused.

3. Install Google Analytics and Use Google Search Console From the Start

Google Analytics tracks and reports your website traffic. The tool is free and only requires that you have a Google account in order to get started. It’s best to install it from the very beginning even if you don’t see a need for it; Google Analytics starts tracking on the day it’s installed and can’t be applied retroactively. Most authors, once they’re a couple years in, want and can benefit from the data that Google Analytics offers.

Something not done as often, but that’s also valuable, is registering/claiming your site through Google Search Console. You can connect Google Search Console and Google Analytics for improved reporting. While Google Search Console is more advanced than what most authors will be able to understand, it still offers functionality you’ll want over the long term. In the short term, use it to send you alerts when Google has problems properly indexing/accessing your site for search purposes.

For those of you who’ve dealt with website maintenance for a long time: What do you wish you knew from the start? Anything you’d like a “do over” on? Let us know in the comments.

October 5, 2015

5 Observations on the Evolution of Author Business Models

Note from Jane: If you enjoy this post, then take a look at The Hot Sheet, an email newsletter I write and edit to help authors understand new developments in the publishing industry.

Over the last four days, I’ve been attending and speaking at the NINC conference, which is open only to NINC members. To be a NINC member, you must be a novelist with at least two books published. Most members have published far more than that—even over a hundred titles.

While NINC is not limited to women, most authors at NINC are in fact women who actively publish romance and women’s fiction. While a mix of traditionally published and indie published authors attended, most sessions were heavily oriented toward self-publishing and digital distribution. Representatives were on hand from Amazon KDP, Amazon CreateSpace, Audible, IngramSpark, Kobo, B&N NOOK, Apple iBooks, Draft2Digital, Reedsy, ALLi, BookBub, and others.

This was my first time speaking at NINC, and it’s by far the most professional and established group of authors I’ve ever spoken to. The absence of the aspiring or first-time author was especially stark for me, since that’s who I’m much more accustomed to encountering. It felt like that might be the case for other speakers as well; one often heard speakers say from the podium, “But of course you all know this already,” as they self-consciously hurried to present more advanced information while the room collectively tapped its impatient foot.

After four days of immersion with this very experienced group of authors, I have a few observations about the business of authorship as publishing becomes increasingly digital-driven. (Ignore any recent misleading articles from the New York Times reporting the contrary.)

1. The Importance of Series in Marketing, Promotion, and Overall Career Growth

My guess is that the large majority of NINC members are actively writing at least one series, if not more, and also releasing new titles on a very regular basis (every three to six months). Having more titles gives an author far more flexibility and options when it comes to marketing. You can make your first-in-the-series book free (to bring in new readership to a series), run more types of promotions because of more diverse pricing across your list, and do bundling and box sets.

The branding and promotion benefit offered by a series is a huge advantage; authors of standalones are hard pressed to match it unless they’ve managed to build up significant brand awareness or strong direct reach to readers. Years ago, when I first talked with Sean Platt (before he released Yesterday’s Gone in episodes and seasons), he was convinced that the path to success was following the narrative model that’s evolved for binge-worthy TV, with seasons-long story arcs and episode cliffhangers.

Sometimes in the industry we divide authors into indie versus traditional or genre versus literary. The more important difference I’m seeing is series versus standalone, not that one must choose, but when trying to gain any traction as a new author, publishing standalone after standalone feels much more Sisyphean than starting with a series.

I’m starting to hear established authors advise new indie authors to wait to go to market until they have three titles ready to publish. When first-time authors come to me for marketing advice, more and more I feel at a loss to help them. I’m inclined to say “Come back when you have a few books, all targeted to the same readership, and maybe we’ll have something to talk about.”

How long it will take before more literary authors consider the series approach for themselves? It’s certainly working for Hilary Mantel! Or, if a series approach doesn’t appeal, perhaps a serialization model, which is how The Martian and 50 Shades of Grey began. (I covered the serialization trend at length here.)

If I wanted to give this post a click-baity headline, I could say “How Much Longer Can Standalone Novels Survive?” but I don’t think they’re going away any more than movies are going away now that TV is doing so well. Still, when authors consider how they can turn writing into a full-time living, I’m not sure this trend toward series can be ignored. David Gaughran has commented on this at length.

Culturally speaking, it’s interesting to reflect on why things are headed in this direction. For a while now, Hollywood has been very risk-averse, series- or sequel-oriented, and more likely to make movies based on existing intellectual property. We excoriate them for doing so—but perhaps consumer demand pushes them in this direction. Maybe many of us desire to revisit and explore characters and storylines already familiar to us. Mantel’s work is undeniably original, but how many times have we now revisited the Tudors? Maybe it’s more convenient or comforting to go back to stories and characters we know—and to reimagine them ourselves (think: fan fiction). Do we have less time and headspace to consider stories without an immediate or reassuring connection? I don’t mean this in a judgmental way in the least; instead, I rather like exploring this idea and how it might shape authorship.

2. The Use of Social Media as a Data-Driven Marketing and Promotion Tool

The NINC members all use social media in one form or another, but there were no sessions focused on using it. When it was brought up during a session, it was always as a means to an end—that end being book sales.

Frankly, this attitude is refreshing; you get away from all the soft, mushy talk about community-building and relationship-building, and really get down to brass tacks. What effect does your activity have on sales? It is measurable, and Courtney Milan gave an excellent presentation on exactly how to measure.

First, you need to have an Amazon affiliate account and generate tracking links for each social media environment and every channel where you might offer a buy link (e.g., your website, your email newsletter, your book’s end matter). That way you can see which links are driving purchases.

Second, you need a link shortener so you can see how often your links get clicked. Those two tools working together give you all the insight you need into how well your social media use (as well as other promotional activity) leads to purchases.

Serious authors are taking the time to do this—because it saves their time later and increases the effectiveness of their long-term marketing and promotion. To see an example of this in action, read this post on the launch of a book called Traction.

NINC and indie authors are also active advertisers on both Facebook and Twitter, and truly understand what it means to run consistent and targeted placements across social media in connection with book launches as well as price promotions. While such tactics are widely seen as only applicable to indie authors, proactive traditional authors could learn a lot from indie techniques, and perhaps persuade their publishers to partner with them on targeted campaigns. (If you’re interested in getting your feet wet with Facebook advertising, then here’s a three-part video series that will lay the groundwork. Be aware that it ultimately promotes a full-length paid course.)

3. Where Innovation (and Power Plays) Happen: Ebook Retailers and Distributors

As I mentioned in the opening to this piece, nearly every ebook retailer, distributor, and service provider was at NINC to meet with authors and to discuss large-scale trends, metadata, title optimization, new features, and merchandising/promotion opportunities.

Not that long ago, it would’ve been unthinkable that an author would be able to talk directly with a retailer or distributor about sales optimization. (Not that your average non-entrepreneurial author would even be interested in the first place—that’s traditionally the domain of the publisher.) Now you’ll find retailers and distributors assuring authors that they’re working on new features and innovations to help sell more books. I sat in on a session presented by Draft2Digital (an ebook distributor), and it became clear the service was beloved by the NINC membership because they are so customer-service oriented, make the authors’ jobs easier, and continue to innovate. (I’m pretty confident even traditional publishers would love to have some of the features offered by Draft2Digital for their own digital housekeeping purposes!)

Yet—and this is not to undercut the very real advances made by ebook retailers/distributors—we’re still talking about rather simple, commonsense improvements, e.g., alerting customers when their favorite author releases a new book. (A no-brainer, I think everyone would agree.) Such progress receives overwhelmingly positive response from authors, but we’re truly in the early days (dark ages) of what’s possible in ebook retailing.

Also, whereas authors were overly dependent on their publishers for success prior to the ebook revolution, will power now overly shift to these services? Obviously, people often talk about Amazon as having too much power, but it’s not necessarily just Amazon who can and will affect how well authors sell in the digital market.

Gareth Cuddy of Vearsa gave an excellent talk in which he encouraged authors to sell their work direct from their site, using tools such as Aerbook, Payhip, or Gumroad. While I’m a fan of selling direct in theory, I’m not sure authors’ direct sales can ever compete with what they potentially stand to gain through Amazon’s algorithms and frictionless purchase process. (See Suw Charman-Anderson’s blog post about challenges in selling direct.)

4. The Next Frontier: International Sales

There were two fascinating moments at NINC regarding foreign markets, translations, and sales in other territories:

There are now 1 billion Apple devices in the world, each with the iBooks app installed. More and more people are reading on mobile devices, and some suggest this favors Apple book retail over Kindle retail in the long term. A panel of NINC authors reported growing sales via the iBookstore—and even one author is well-known for her Apple iBookstore sales outpacing her Kindle sales, although this is certainly an outlying case. The Apple iBookstore offers books in 51 territories; Kindle is currently in 14 territories.

When Draft2Digital gave an overview of their sales stats, they reported roughly 70 percent US sales and 30 percent non-US sales. I found this interesting, but I don’t have much context for it; e.g., what’s the split for books sold through Amazon or distributed via Smashwords? It would be nice to know. But in any event, let that sink in: one-third of sales happening outside the US, and most countries are nowhere even close to the US level of ebook reading and adoption. (The closest is the UK.)

5. The Writing Is Still the Focus

I rarely meet a writer who would like to spend less time writing—and that holds true at NINC, where authors are perhaps more business focused than at any other conference I’ve attended. NINC offered an entire session for author assistants—people who help authors with administrative, business, and marketing tasks. Authors at NINC often bring along such assistants, as well as business managers (who may be spouses), and it impressed upon me the now-frequent observation that self-publishing is a misnomer. It requires some level of support both to write and to manage your business so that it produces a full-time income.

I’ve been seeing more people online (and elsewhere) put out their shingle as author assistants, or offer some form of one-time or ongoing support service. Kate Tilton is one example, and I expect to see more of this in the future.

If you’re interested in more useful takeaways from NINC, check out Elizabeth Spann Craig’s write-up.

Also, The Hot Sheet, an email newsletter that I write and edit with Porter Anderson, helps authors understand new developments in the publishing industry. Subscribe via email.

October 2, 2015

How to Balance Your (Writing) Life: A Guide for the Perplexed

When I worked at Writer’s Digest, we typically published books in three key categories:

how to write better (craft & technique)

how to get published

inspiration / self-help

This last category I always felt wary of; it encompasses your bestsellers and worstsellers. It’s about the stuff that surrounds the actual writing, such as how to balance the demands of authorship with other demands in your life—or how to make sure you write in the first place. It often tackles the psychological battles.

Such territory is incredibly subjective and very personality-driven.

That’s why I like this 30-point list from David James Poissant—How to Balance Writing, Family, Work, and Life: An Unhelpful Guide for the Perplexed—which plays on our desire for this type of advice, but also on the paradoxes that lie within it. For example, a few items:

7. Throw away your television.

16. Okay, don’t throw away your television. You’ll miss it when the tornado’s on the way. But, at least, like, unsubscribe from premium cable.

30. Results vary. Side effects range from obscurity to the Nobel Prize.

Read the full 30-point list over at Glimmer Train.

Also this month at Glimmer Train: Revision as Therapy: I Didn’t Understand My Book Until After I Sold by Matthew Salesses

October 1, 2015

Getting Self-Published Books Into Libraries

by Dick Thomas / Flickr

Over the last year, there’s been much more discussion of how self-published authors can get their books into library systems. Partly, I think that’s a function of new services and distribution agreements (such as SELF-e), but it’s also one of the last remaining channels that remains fairly difficult for an indie author to access.

In my latest column at Publishers Weekly, I address what independent authors need to know about getting their book into the library market. I start by saying:

While indie authors can gain some access to libraries by making their books available through major library distributors, that doesn’t mean that those books will be purchased. In many ways, getting self-published titles into libraries hasn’t changed since the e-book revolution: authors still have to prove that they have quality products that fit the collection. And, unfortunately, authors still face the stigma of self-publishing: there’s a long history of patrons offering to donate handwritten poetry collections or memoirs to their libraries.

September 30, 2015

Interview with Chuck Sambuchino: The Keys to Publishing Success

When I was still at Writer’s Digest as editorial director and publisher, I oversaw the Writer’s Market series and had an upfront seat from which to observe the excellent work of Chuck Sambuchino (@ChuckSambuchino), who launched the Guide to Literary Agents blog—now one of the biggest blogs in publishing—and who edits the Guide to Literary Agents and Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market annual guides.

In addition to his editorial work at Writer’s Digest, Chuck also authors humor books. His books have been mentioned in Reader’s Digest, USA Today, the New York Times, the Huffington Post, Variety, New York magazine, and more; his humor book on garden gnomes was optioned by Robert Zemeckis. His newest humor book, When Clowns Attack, just released this month.

Chuck recently took the time to answer some questions about his own career, as well as lessons for writers about the publishing industry today.

JANE FRIEDMAN: You’ve been networking with and researching agents for a long time now. What significant changes have you seen in agenting or in the market since you entered the industry?

CHUCK SAMBUCHINO: I came to Writer’s Digest ten years ago, and I can certainly say that it’s more difficult to sell books now than it was then—simply because people are buying fewer books now. That’s why agents and editors are only looking for the best of the best debut novels. You really have to turn in an excellent, polished product. And that’s why nonfiction publishers are only looking for projects where it’s a unique combination of a good idea plus good author platform.

But what’s interesting in all this is that the number of literary agents in the country has not gone down; I believe it’s gone up. And I think that’s just because you’ve got a percentage of people who really, really want to be part of the publishing industry and see books succeed, and agenting offers a good entry route (rather than being an editor or publicist), in my opinion.

But from a fiction writer’s perspective, these changes shouldn’t really affect anything. A fiction writer’s job today, just like it was ten years ago, is to write something magnificent.

Your own work presents an interesting case study for the multi-genre approach, which I usually recommend against, at least for unpublished writers. Can you speak to the advantages and/or disadvantages for your career in writing and publishing many different types of work?

That’s true. I create writing reference books for Writer’s Digest. I write pop humor books for traditional publishers. And I even have a kid-lit agent and a screenwriting manager trying to sell stuff. So you’re right about the diversity of my work. Personally, I think it’s exhausting to fire in many different directions. I don’t do it for the logic or money. I do it because it’s more fun and I have writing A.D.D. Trying new things excites me, even if it’s not the 100 percent best career decision at any given moment. But I’m doing okay with it all, so I am a case study of how it can work if you put in the time and effort.

You’ve authored several books (When Clowns Attack releases this month), and of course also continue to edit the annual market guides at Writer’s Digest. So you’ve had a lot of experience year after year of launching and marketing books. Can you give us an idea of how you put together a marketing game plan, and/or what you consider the must-do tasks?

The books are different, so each one requires a different strategy, and I will show you how I lay out some marketing plans below. But real quick, let’s discuss two things:

Although I am writing in different categories (in this case, writing reference and nonfiction humor), the titles can still help each other. There is some opportunity for sales to bleed over. Certainly some people who notice me for writing advice will enjoy a good gift book. And certainly some people who notice me for the humor books have a small interest in writing. There is some overlap, although it’s hard to say how much. The point is all promotion can help all books in little ways, if you let it.

The other thing I need to mention is that just because you do something one year doesn’t mean you can do it the next. For example, look at this interview we’re having right now. Let’s imagine I emailed you next fall and said “Hey, the 2017 Guide to Literary Agents is now out—want to do an interview?” You may say yes, but I am guessing part or all of you would think “But didn’t we already cover that ground in our interview last year?” So when you’re seeking promotion for a second book (or third or fourth), you want to think about both new promotional opportunities and the familiar ones, because you can’t really ask everyone who’s helped you with coverage in the past to do it for every book.

Now let’s look at some promotional specifics for each of my three new books that came out this fall. The “must-haves” for each include:

a blog giveaway contest

newsletter mentions

mentions to my social media networks on Facebook and Twitter.

The 2016 Guide to Literary Agents: I held a big giveaway contest on my GLA Blog. All readers had to do was comment to try to win a free book. The contest got 200 comments and was a success. I helped my own cause by allowing anyone who tweeted news of the contest to have two entries into the contest instead of one. Doing things like this encourages others to promote for you. I also mentioned it twice already as the lead news item of my big Guide to Literary Agents newsletter. After that, it becomes a matter of contacting other publishing-related or agent-related sites and doing guest blogs, usually accompanied by giveaways. So I’m guest-blogging for agent Carly Watters’s blog and agent Linda Epstein’s blog and thriller writer James Scott Bell’s joint blogging site, The Kill Zone. In terms of what I guest blog about, it’s a matter of finding nice little excerpts from my books or blog posts, or coming up with new blog ideas that I put aside for a special opportunity.

The 2016 Guide to Literary Agents: I held a big giveaway contest on my GLA Blog. All readers had to do was comment to try to win a free book. The contest got 200 comments and was a success. I helped my own cause by allowing anyone who tweeted news of the contest to have two entries into the contest instead of one. Doing things like this encourages others to promote for you. I also mentioned it twice already as the lead news item of my big Guide to Literary Agents newsletter. After that, it becomes a matter of contacting other publishing-related or agent-related sites and doing guest blogs, usually accompanied by giveaways. So I’m guest-blogging for agent Carly Watters’s blog and agent Linda Epstein’s blog and thriller writer James Scott Bell’s joint blogging site, The Kill Zone. In terms of what I guest blog about, it’s a matter of finding nice little excerpts from my books or blog posts, or coming up with new blog ideas that I put aside for a special opportunity.

The 2016 Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market: This book is solely for writers and illustrators of children’s books and novels, so it requires some special targeting. When I put together some guest blogs to send out, I contacted specific kidlit sites, such as Debbie Ridpath Ohi’s InkyGirl site and Adventures in YA Publishing. And then I send them specific guest posts that they will like. For example, I just sent Debbie a post called “5 Literary Agents Seeking Picture Books NOW.” Besides that, I reach out to every SCBWI regional advisor in the country and say, “The new CWIM is out. Please let me know if you want a copy for a giveaway contest online in the next few months. And if you are having a regional conference in the next year, I can send a copy for a door prize giveaway. Thanks.” That helps push it out to specific markets. I will also do a giveaway of it (like the GLA book) on my GLA Blog in the coming months.

The 2016 Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market: This book is solely for writers and illustrators of children’s books and novels, so it requires some special targeting. When I put together some guest blogs to send out, I contacted specific kidlit sites, such as Debbie Ridpath Ohi’s InkyGirl site and Adventures in YA Publishing. And then I send them specific guest posts that they will like. For example, I just sent Debbie a post called “5 Literary Agents Seeking Picture Books NOW.” Besides that, I reach out to every SCBWI regional advisor in the country and say, “The new CWIM is out. Please let me know if you want a copy for a giveaway contest online in the next few months. And if you are having a regional conference in the next year, I can send a copy for a door prize giveaway. Thanks.” That helps push it out to specific markets. I will also do a giveaway of it (like the GLA book) on my GLA Blog in the coming months.

When Clowns Attack—A Survival Guide: This one is the trickiest, because there are not central anti-clown humor hubs online. So it requires a more focused and targeted approach. After the usual blog giveaway and such, I will be writing blogs on my own site, rednosealert.com, and then sharing news of those posts to people on Twitter one by one. I just search for different phrases, such as “I hate clowns.” You’ll turn up hits all over, and I engage them by saying “I hate clowns, too.” If there is some sort of conversation, I point them to my new website, and they see an article like “5 Ways to Clown-Proof Your Office,” and then there’s a picture and buy link for the book. I also will reach out to pop culture sites (some cold, some through referrals and my publicist) and ask them to excerpt the book.

When Clowns Attack—A Survival Guide: This one is the trickiest, because there are not central anti-clown humor hubs online. So it requires a more focused and targeted approach. After the usual blog giveaway and such, I will be writing blogs on my own site, rednosealert.com, and then sharing news of those posts to people on Twitter one by one. I just search for different phrases, such as “I hate clowns.” You’ll turn up hits all over, and I engage them by saying “I hate clowns, too.” If there is some sort of conversation, I point them to my new website, and they see an article like “5 Ways to Clown-Proof Your Office,” and then there’s a picture and buy link for the book. I also will reach out to pop culture sites (some cold, some through referrals and my publicist) and ask them to excerpt the book.

All Books: You can sell a lot of books on the road, so I packed my fall with conference speeches and instruction. Besides being at my hometown (Cincinnati) book fair in October, I am teaching at six different writers conferences from September through November. (See them all here.) When I speak publicly, I get the chance to instruct on writing, but also make people laugh—and the former will draw people to consider buying the GLA or CWIM, while the latter will draw people to consider buying When Clowns Attack.

Here’s a very unfair question, but I hope you’ll play along. By the time I left Writer’s Digest, I had experienced a 180 on the role talent plays in writing careers. When I started, I felt like talent was essential. When I left, I came to see it as a squishy, hard-to-pin-down quality. This has become a vexing issue, because so many writers basically want me to say whether they have what it takes. Where do you come out on this issue?

This is difficult to answer because in every case, the answer is both yes and no—it depends on the case and the book and the writer. Let’s look at some more details.

Do you need talent to get your fiction traditionally published—i.e., to get an agent and sell to Doubleday? My answer is basically yes. Hardcore writing talent is more in demand than ever before in this crowded marketplace. Talent is always subjective, but I think the answer is yes.

Do you possess extraordinary talent if your work becomes a bestseller? My answer is basically no. One agent recently said to me, “I believe a bestseller can be completely manufactured. All you have to do is print 250,000 copies of the book and make it your lead title and push it down readers’ throats, and they’ll buy it.” And the agent was basically right. Bestsellers often happen because (1) the author’s name is one the populace recognizes, so they buy the book without scrutiny, or (2) the book is just visible everywhere (every bookstore, in Target, Walmart, etc.), so a reader thinks, Hmmm, this book is everywhere—maybe I should see what the fuss is about, or (3) it’s a Fifty Shades of Grey situation where it takes off for any strange reason (in this case, I think, the lack of a breakout erotic mainstream book in many years and the fascination [naughtiness!] that came with that), so a reader thinks, Hmmm, this book is everywhere—maybe I should see what the fuss is about. So right there we’ve examined three possible ways for a book to become a bestseller without the writer having oodles of talent. But again, this is a massive gray area (like the book—ha), because you look at a book like Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why , and that was just another contemporary YA debut that came out and kind of piddled along sales-wise. But it was really good, and word of mouth slowly slowly slowly drove it to the bestseller list, where it has remained for years. So that is a case of a bestseller that I attribute to talent.

Do you need talent to get your nonfiction published? My answer is basically no. If you’re on TV or your pop culture website blows up overnight or your name is Chelsea Handler, you can sell a book easily. Platform is everything in the nonfiction realm. However, the exceptions really start coming in when you examine non-celebrity memoir as well as narrative nonfiction. Those books need to be superbly written to get published, most of the time.

For years, you’ve collected and run stories on your blog and in Writer’s Digest magazine about breaking in—how debut authors eventually got their first deal. What themes come up again and again in these stories?

Get in this for the long haul.

Educate yourself. Study how great stories are written, and read lots of writing advice.

Get involved in your writing community and make friends (and meet critique partners).

Write more than one book.

Don’t give up.

Edit, revise, edit, revise.

Ask for feedback from others and realize some of the story critiques you get (even the stuff you don’t like) is dead on.

What’s the best advice you’ve been given, and what’s the worst advice you’ve been given?

I can’t think of any terrible advice I’ve heard, so let me throw out two helpful notes that stuck with me. Seven and a half years ago, I heard a novelist at a conference say “We all have a time-related excuse to not write.” What he was saying was: I know you may have kids, I know you may be caring for a sick relative, I know your job may wear you out—but you need to get past that excuse or it will drag you down forever. And he was dead on about that point.

Another quote is one attributed to writer David Mamet, I believe, but I cannot verify that online. Anyway, it’s the quote/question, “What have you done for your career today?” The quote basically says that there is always something you can be doing to help your books and your career—will you put in the work and do it?

To read more of Chuck’s work, visit his blog, or take a look at his fall releases:

When Clowns Attack

2016 Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market

2016 Guide to Literary Agents

September 28, 2015

How to Effectively Handle Time Shifts in Your Story

by árticotropical / Flickr

Note from Jane: This post is an excerpt from The Mind of Your Story by Lisa Lenard-Cook.

Everything that happens in your fiction should occur at the moment when it will evoke the greatest response from a reader. This means that even if your fiction’s timeframe begins at point A and then moves forward till it ends at point B, the story doesn’t need to progress lineally. Instead, your story should move forward emotionally, building momentum toward its climax.

Yes, scene A may have occurred in time before scene B, but your fiction may achieve far more emotional impact if scene A occurs after scene B. In other words, the placement of each scene must be relevant to its emotional impact in the mind of your story.

Consider any story by Alice Munro and you will see what I mean. Munro begins almost all of her stories in a particular moment that takes place long before or after its primary timeframe. She then moves back and forth in her story’s mind until she arrives at another particular moment, also often long before or after the story’s primary timeframe.

The climactic moment of a fiction affects not only that moment but every moment that came before and all that will come after. Like a stone dropped into a pond, it ripples outward. Nothing is the same once the climax has occurred. It’s the largest kairos—moment in emotional time—in a fiction.

Remember that your main goal is to keep your fiction moving ever forward. Sometimes, however, the best kairos occurs in a character’s—and the fiction’s—past or future. It’s at these moments that we go back or forward in time, either via a flashback or a time shift. The key is to ensure each time shift occurs at the right moment in your fiction.

A character’s past and future are always relevant to her present. Not only are we products of everything that has gone before in our lives, but our hopes and dreams for the future affect what we do now as well. And just as certain parts of our own lives are more relevant at one moment than another, the moments of our characters’ pasts and futures must be relevant to the moments in which we reveal them. In other words, the time shift you choose to reveal must color your fiction in some important way at the moment you reveal it.

This means that a number of questions will come into play whenever you think it’s appropriate to move around in time. Let’s look at each of them individually.

1. When Is a Time Shift Appropriate?

As any agent or editor will tell you, it’s best to get your story’s “present” going at a good pace before you slip into its past. One of the errors I often see in early drafts of novels is a time shift in the first five pages. A good rule of thumb is to get at least one-tenth into your narrative before you begin going back in time. In a 75,000-word novel, this would translate to 7,500 words, well into your story’s present narrative. The main reason for this is so that readers become emotionally invested in your protagonist, but it’s also important to make sure your readers feel thoroughly grounded in time and place before moving them off somewhere.

This said, time shifts can occur anywhere throughout a fiction. Just don’t drop into flashback arbitrarily, because there doesn’t seem anything better to do at the moment. This leads to the next question:

2. Why This Time Shift Now?

You can’t shift time simply because there doesn’t seem to be anything going on in your fiction’s present. As I said above, the past you choose to reveal must color your fiction in some important way, but more than this, it must color your fiction at this moment in its telling in some important way. This particular flashback must matter now, at this particular moment.

As an illustration, I had a great deal of fun moving back and forth in time in my short story, “Men on White Horses.” In the passage that follows, I move from a photographic display on the protagonist’s refrigerator directly back in time to her childhood:

The front of the nonworking refrigerator serves as impromptu photo display. Here are Franny’s grown daughters, Leslie and Marie, and here’s her sister Frieda, pretending she’s about to fly off the Whirlpool Trail. They could hike that trail in their sleep, and in her dreams Franny still does, the sheer drop down to the swirling water below never signifying danger as it ought to but instead something familiar and true.

Their father told them that when he’d been a boy, he sometimes found arrowheads along the trail. Animals—deer and wolves, he said—had made the trail down to the river, and then the Indians, stalking the animals, widened it with their stealthy footsteps. Now, us, he said. We’re followers, not pathmakers. Listen. Pay attention. Sooner or later, you’ll find an arrowhead of your own.

Franny strained to pay attention. She reminded herself to pay attention. And yet when something unexpected happened it always surprised her. Like that time Frieda had suddenly shoved her against the sheer wall along the trail …