Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 141

October 27, 2015

It’s Here! My Great Course on How to Publish Your Book

I am thrilled to announce that my 24-lecture series on how to publish your book is now available from The Great Courses. It is the closest I have ever come to offering an A-to-Z comprehensive course for writers who want to learn as much as possible about the publishing business and career-long strategies for successful authorship.

The course is available in several formats:

audio download (least expensive)

video download

CD

DVD (most expensive)

All formats come with streaming access to the course, as well as a printed or digital 192-page guidebook. The course is also available to Audible users.

Here’s a 3,000-word description of the course; below is a quick overview of each lecture, each about 28-30 minutes in length.

1. Today’s Book Publishing Landscape. Take an in-depth look at the world of writing and getting published: the history of the business, the competition in the modern market, and the major and minor players in the industry.

2. Identifying Your Fiction Genre. Understanding where your fiction book falls in the general categories of literature is an essential step to getting published, as there is a plethora of genre-specific publishing houses.

3. Categorizing Your Nonfiction Book. Delve into the various genres of nonfiction writing, and learn how to determine which publishing house best aligns with your nonfiction manuscript.

4. Researching Writers’ Markets. The modern publishing markets are far more complex than they were even a few decades ago. Learn about the different agents and publishers, and discover the tools out there that can help you find the right ones for you.

5. What to Expect from a Literary Agent. Learn how to acquire an agent, what to expect from an agent, and what standard and non-standard practices you may encounter if you choose to go that route.

6. Writing Your Query Letter. The query letter is your first impression and often what catches an agent or publisher’s attention, so it’s important to create a memorable one. Learn what elements comprise a good query letter, what components the publisher or agent requires, and how to stand out from a sea of queries.

7. Writing Your Novel or Memoir Synopsis. Once you’ve nailed a query letter, you will need to provide a synopsis. Condensing your entire story into a one-page overview while still keeping it compelling and intriguing is not easy. Learn what your synopsis needs to focus on and accomplish to be successful.

8. The Importance of Author Platform. A platform generally refers to an author’s visibility and reach to a target audience: who is aware of your work, where does your work appear, and how many people see it.

9. Researching and Planning Your Book Proposal. A book proposal is essentially a business plan that persuades a publisher to invest in your book. Publishers look for a viable idea with a clear market, paired with a writer who has credibility and marketing savvy.

10. Writing an Effective Book Proposal. Once you’ve completed the research required, analyze how to effectively incorporate your findings in a compelling manner.

11. Submissions and Publishing Etiquette. While each publisher and agent has their own requirements for you to follow when submitting your work for consideration, there are rules that apply universally and will often result in rejections when not followed.

12. Networking: From Writers’ Conferences to Courses. Just like with a job search, networking can be an important and useful component to getting published.

13. Pitching Your Book. Learn the three types of pitches you should have ready, examine strong and weak pitch examples, and get tips on how to prepare for pitches without succumbing to nerves or stage fright.

14. Avoiding Common Manuscript Pitfalls. Many agents and editors rely on their experience and instinct and can tell within the first page whether or not a manuscript is worth reading further.

15. Hiring a Professional Editor. Explore the different stages of writing and reviewing, examine the different types of editing you can consider, and learn what an editor can and can’t do to make your work publishable.

16. How Writers Handle Rejection. Learn why you might be rejected, even if you’ve done everything correctly. Dissect some of the common reasons for rejection, how to let go of rejection or react to it in a constructive manner, and what your options are if you’ve been rejected

17. Overcoming Obstacles to Writing. Rejections are not the only obstacles to becoming a published author. Look at common dilemmas writers face, and learn how to create time for writing no matter what your daily schedule looks like.

18. The Book Publishing Contract. If you get to the point of the process where publishing contracts are being drafted, it’s important to understand the terminology and protect your rights.

19. Working Effectively with Your Publisher. While most aspiring writers are thrilled to get to this point in the publication process, it’s also important to know what will be expected of you once a publisher agrees to move forward.

20. Becoming a Bestselling Author. Marketing your book is a huge part of becoming a bestseller, and much of the onus of marketing will fall on you.

21. Career Marketing Strategies for Writers. Author websites, blogs, newsletters and emails, and social media will be your responsibility.

22. The Self-Publishing Path: When and How. When is self-publishing a viable option for your book? Learn what steps you should take if you choose to self-publish, and learn about the tools you will need to succeed.

23. Principles of Self-Publishing Success. Understand the role of metadata, pricing, and reviews to help your book get noticed.

24. Beyond the Book: Sharing Ideas in the Digital Age. Consider the many ways besides a book to write, publish, and share ideas in the digital age.

The Great Courses has made this course available at a significant discount upon its release, but the discount doesn’t last forever. Visit their site to purchase or find out more.

October 26, 2015

The Business Model of Literary Journals (or Lack Thereof)

Rachel Ford James / Flickr

When I began my publishing career, it was easily the one ethical guideline that reputable journals, magazines, publishers, and agents all agreed on: no reading fee, ever. Writers should never be charged for the opportunity to submit their work.

I worked at Writer’s Digest for a decade, so this was a rule of thumb I repeated often at conferences and workshops. It helped writers avoid scams and target their efforts at the most reputable outlets. (Writer’s Digest is the publisher of the Writer’s Market series, including Novel & Short Story Writer’s Market and Poet’s Market.)

About the same time I left Writer’s Digest, a new startup entered the scene: Submittable. Submittable has two standout benefits: (1) it allows publications to streamline and automate the submissions review process internally, and (2) it gives writers a single portal from which to submit their work to many publications at once, remember what’s out on submission, and see the status of those submissions at a glance.

This efficiency and frictionless submissions process has come with a cost: submissions can be made with very little effort by the writer—which increases the volume of submissions that journals receive—and publications have to pay to use Submittable. Here is the current cost if you’re a literary journal.

Professional Plan

300 entries/month and 8 staffers/readers

$160 per year

Premier Plan

800 entries/month and 20 staffers/readers

$325 per year

Enterprise Plan

2000 entries/month and unlimited staffers/readers

$1100 per year

When I worked at the Virginia Quarterly Review, I oversaw the implementation of Submittable. The journal was opening to submissions after a long period of being closed, and it didn’t take even a month before we required the most expensive Submittable plan. I had already loosened my position on reading fees prior to arriving at VQR (the publishing world is not the same as when I started in the mid-1990s), but after witnessing what happened when the gate was opened—and what type of material arrived—I was ready to argue for the ethicality of reading fees.

(Note that I am using the term “reading fee” to mean any fee a writer must pay for their work to be considered; journals prefer to call them “service fees” when the fee is clearly tied to submission through an online portal.)

How Much Does It Really Cost to Submit Your Work?

I’m writing on this topic because of conversations I’ve recently had with writers who feel mistreated and ill-used by reading fees. This article in The Atlantic will give you an idea of how the argument plays out.

First, I think it’s important to look at what the reading fees would really add up to if you were submitting to 20 of the most popular literary journals:

Ploughshares: $3 if you’re not a subscriber, but you can submit by mail for free

Tin House: no fee

Paris Review: no fee, mailed submissions only

New England Review: $2 or $3 if you’re not a subscriber

The Georgia Review: $3 if you’re not a subscriber, but you can submit by mail for free

Kenyon Review: no fee

The Antioch Review: no fee, mailed submissions only

The Southern Review: $3, but you can submit by mail for free

Gettysburg Review: no fee

The Cincinnati Review: no fee

The Hudson Review: no fee

Virginia Quarterly Review: no fee

The Iowa Review: $4 if you’re not a subscriber, but you can submit by mail for free

Alaska Quarterly Review: no fee, mailed submissions only

Creative Nonfiction: it’s complicated, but usually $20; you can submit by mail for free if not submitting based on a theme

Glimmer Train: $18, and they offer annual opportunities to submit with a $2 fee

The Sun: no fee, mailed submissions only

Agni: no fee

The Missouri Review: $3, but you can submit by mail for free

Ninth Letter: no fee

By reviewing this list, a few things become clear:

Not even half of these journals charge a fee.

Those that do charge a fee still allow for free submissions through the mail.

It is still easy to submit your work widely without paying reading fees.

It’s also clear that the journals are making an effort not to charge writers who are active subscribers.

The journals charging $2, $3 or $4 are doing the logical thing to remain sustainable: They are covering their cost to use Submittable, and possibly pay staff or readers to go through the increased number of submissions they’re receiving. (Keep in mind Submittable is taking a percentage: 99 cents plus 5 percent for each writer who pays to submit work.)

I admit the situation gets more ethically complex when journals run a series of themed contests that require more substantial fees, such as Glimmer Train or Creative Nonfiction. Still, there are workarounds for writers, and the journals are quite self-aware about what they are asking writers to do. The Glimmer Train editors state on their site:

There is no such thing as a profitable literary journal. To the best of our knowledge, all surviving literary journals are supported by universities and/or by individuals who love short fiction and are willing to put their own time and money into them. Besides making it possible to pay higher prizes to writers, reading fees (and your subscriptions) help keep Glimmer Train Stories a first-class publication credit.

And so we come to the crux of the issue.

Literary Journal Economics

A literary journal’s costs are rarely, if ever, covered by subscriptions, but by a combination of grants, institutional funding, and donations. Even extremely well-regarded, award-winning journals (such as McSweeney’s) have found themselves on the edge of the precipice—and continue in part due to dogged persistence and commitment from their founders and staff, who repeatedly raise the funds needed to continue.

Some literary journals are able to continue partly because the staff work without pay, or little pay. Interns work for free in exchange for experience and connections. Some may donate their time in order to have the prestige or credit for their CVs or resumes.

It’s a misnomer to talk about a business model for print literary journals; they’re nonprofits and continue mostly due to charity and goodwill. Earlier this year, I wrote at length about some of the existential problems now facing them: Are Literary Journals in Trouble?

Sometimes it seems that journals are running out of goodwill among writers. I’m seeing a lot more finger-pointing and public expressions of frustration (see post above). Writers feel exploited and taken advantage of, especially those struggling to find full-time jobs under a load of student debt. We have it so hard already—how dare you charge a reading fee?

I have two thoughts about this:

Writers don’t seem to realize their struggles and literary journals’ struggles are two sides of the same coin. The journals don’t have sufficient funding or support, but they still have to put together a viable P&L. Writers’ lack of funding or support affects their ability to prop up literary journals’ fragile business model. Someone has to pay—so who should it be?

Writers have expectations that simply don’t apply in the publishing world of 2015. (Same goes for literary journals, too, of course.)

Thinking Beyond the Literary Journal

In book publishing conversations, I often talk about “thinking beyond the book,” to help writers see beyond the very traditional methods of telling a story or reaching readers.

Except for a few elite publications, literary journals reach a couple thousand people at best. Gaining entry into their pages still means something, of course—it’s a necessary rite of passage for emerging writers who want to be taken seriously by a particular literary community. You need certain credits for teaching jobs, for promotion, for consideration by other official entities (grants, fellowships, residencies, and so on).

But: It’s only one way to crack the nut. It’s entirely feasible to build up a reputation and publication record (and a writing career) that’s respectable without ever placing one piece in a traditional print literary journal. (I’m thinking right now of Ashley Ford, who I first met while she was a Ball State creative writing student. Her first pieces appeared in well-known online publications—PANK, Rumpus—and she became a staff writer at Buzzfeed. She’s now a full-time freelancer and writes for Elle, has a book deal, etc.)

Writers who complain about how hard it is, how unfair it is, how much they struggle, or how much they’re exploited: I have some sympathy—because there are unethical practices out there—but only up to a point. Unless you’ve achieved financial independence (through the benefit of family or otherwise), wanting to be a full-time writer means treating your writing like a business, approaching it with some level of entrepreneurship, and educating yourself about the industry. If you don’t like the costs or the time and effort involved, then you’re complaining about the rules of a game I assume you willingly entered.

And I have almost zero tolerance for pointing the finger at publications that are struggling just as hard as writers to stay afloat. I agree there’s a difference between publications that have the ability to pay (and/or absorb costs), and those that don’t, but writers continuously have trouble understanding the difference between the two, understanding the business model of the average journal or magazine, or recognizing the dramatic change underway in all types of publishing business models.

October 22, 2015

5 Reasons You’re Experiencing Writer’s Block

by Kai Schreiber | via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s post is an excerpt from Fire Up Your Writing Brain by Susan Reynolds (Writer’s Digest Books).

We’re going to go there, right now, even though it might lead to automatic resistance: Writer’s block is a myth.

It is not something that always existed; in fact, the concept originated in the early nineteenth century when the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge first described his “indefinite indescribable terror” at not being able to produce work he thought worthy of his talent. Romantic English poets of the time believed their poems magically arrived from an external source, so when their pens dried up and the words did not flow, they assumed the spirits, the gods, and/or their individual muses were not visiting them with favor.

French writers soon latched onto the idea of a suffering connected to writing and expanded it to create the myth that all writers possessed a tortured soul, unable to write without anguish. Later, the anxiety (the artistic inhibition) that often accompanies writing was blamed on, or turned into, neurosis, depression, alcoholism, and drug addiction. On good days, writers suffered for their art, and never so much as when they allowed psychological issues to thwart their ability to write.

Here’s the simple truth: The very nature of the art of writing incorporates uncertainty, experimentation, and a willingness to create art from the depths of who we are. Writing is a mentally challenging occupation which requires more hard-core, cognitive expenditure than many other lines of work.

Here’s another truism: Lots and lots of adults don’t like to think; once they have an occupation that provides a living and keeps them relatively happy, they prefer to live in a mentally remote world where they have a job they can do, sans hard-core thinking.

But writers have to think and think hard—and we have to think beyond mastering craft into creating works full of meaning, purpose, and nobility—and then editing and selling them. So, to even assume that this should go smoothly—particularly in the slogging middle—is to be misguided.

Writing is not for sissies, and if you intend to write novels, screenplays, or plays, it will not be easy, and you will often come up against a wall of resistance. Just don’t call it “writer’s block,” call it what it is: not being prepared to move to the next level.

That being said, a discouraging loss of steam strikes even the best and most prolific writers. Even though it’s natural, and fairly predictable, one must never linger, which is why this chapter will offer a spate of ideas to break the spell and get your writing brain back on track. But we begin, of course, with reasons why all writers get stalled.

1. You’ve Lost Your Way

All writers reach a point when they lose their way, their work veering off into unforeseen directions or experiencing a surprise (like when a character you didn’t anticipate shows up). Rather than permitting this to sabotage your momentum, take a day or two to rethink your story (or project). Identify the holdup, and loosely dance around it a few days. If it’s a character issue, go to the library, pull some of your favorite books off the shelves, and see how writers you admire dealt with similar problems. If it’s a setting issue, visit the place in question, or a similar site, and spend some time absorbing elements that you can weave into the story.

If you’re stalled because you lost your way, try the opposite of what you usually do—if you’re a plotter, give your imagination free rein for a day; if you’re a freewriter or a pantser, spend a day creating a list of the next ten scenes that need to happen. This gives your brain a challenge, and for this reason you can take heart, because your billions of neurons love a challenge and are in search of synapses they can form. You can practically feel the dendrites fluttering their spiny little arms.

If you’re having trouble identifying the problem, your perspective may be too constricted. Try pulling back. Think about how the story is working on a larger scale, give yourself credit for getting this far, and then hone in on what you think may be the hitch. Maybe you think your character has turned into a caricature or the plotline is too weak. If that’s the case, look through the previous fifty pages for ways you can tweak it to achieve what you want. Often the brilliance is right there, just waiting for you to claim it.

2. Your Passion Has Waned

It happens. Because writing a novel requires immersion—thinking about it, crafting it, dreaming about it, obsessing about it—your brain may be on overload or just bored. It doesn’t mean that your writing is boring; it means that you’ve worked and reworked the material so much that it now feels, sounds, or reads boring—to your mind.

A pair of fresh eyes would likely have a more objective opinion, though it’s not time to ask for outside eyes. Asking now may invite uninformed opinions (no one will have invested as much as you have to date) that make you question everything, and editing while writing can stifle creativity. Wait until the first draft is complete and it’s time to edit, before allowing yourself, or others, to question your creative decisions or, worse yet, to nitpick.

Lots of writers discard projects at this stage, often lamenting that they just lost the juice they needed to keep going. They chalk it up to choosing the wrong project, the wrong genre, the wrong topic, the wrong characters, or whatever. That may be the case, but if feeling bored about a third of the way in becomes a pattern, it’s likely more about you than about the story, characters, or subject matter.

Remember, your writing brain looks for and responds to patterns, so be careful that you don’t make succumbing to boredom or surrendering projects without a fight into a habit. Do your best to work through the reasons you got stalled and to finish what you started. This will lay down a neuronal pathway that your writing brain will merrily travel along in future work.

If you’ve lost steam and fear it’s because you’ve chosen the wrong subject, take a day or two to do, read, or think about something else. Before you go back to the manuscript, ask yourself these three probing questions to reveal the real reason you chose this topic, these characters, this storyline, this theme, and so on:

What drove me to write about this in the first place?

Why did I feel that this was worth a year of my time?

What is it that I wanted the world to know?

If your reasons remain solid, true, and important enough to you, you’ll likely spark a few “grass fires” into your neuronal forest, which will send you rushing to your desk to get words on paper.

3. Your Expectations Are Too High

A mistake many novice writers make is in setting their sights too high, expecting perfection when they have yet to write a complete novel or screenplay. The best advice anyone can give inexperienced writers is to write a first draft as quickly as possible, as good books are not written, but rewritten and rewritten and rewritten. Once you have a first draft, you have a solid base on which to build, and all the “problems” you anticipated will work themselves out as you massage and craft your raw material.

What stops many writers midway is attempting to make the first draft the best they can write. Some believe it’s the way real writers write, which is generally not true; and some believe that perfecting each chapter will relieve them of the need to rewrite, which is also not true. Imposing this unreasonable need for perfection is bound to cause anxiety—and a great deal of frustration.

The more pressure you put on yourself, the higher your anxiety level rises and the more writing becomes a signal of danger, which transmits a message straight to your limbic system, triggering fight-or-flight reactions. When that happens, the limbic system stops forwarding messages to the cortex, which is where conscious thought, imagination, and creativity are generated. Instead, your amygdala releases stress hormones, like cortisol and adrenaline, and soon, your heart rate is skyrocketing, your ability to feel emotionally safe enough to write is eroded, and your ability to concentrate vanishes. Who wants that? Who wants to re-create that? Small wonder that you are feeling a resistance to writing.

Instead of setting your sights too high, give yourself permission to write anything, on topic or off topic, meaningful or trite, useful or folly. The point is that by attaching so much importance to the work you’re about to do, you make it harder to get into the flow. Also, if your inner critic sticks her nose in (which often happens), tell her that her role is very important to you (and it is!) and that you will summon her when you have something worthy of her attention. That should divert her attention and free you to dive back into the writing pool.

4. You Are Burned Out

It is quite possible that you’ve simply tapped yourself out. We all have our limits, be they physical, mental, emotional, and all of the aforementioned. Eventually your body, brain, or emotions are going to rebel and insist on downtime, which may come in the guise of what you may call writer’s block.

But keep this in mind: You aren’t blocked; you’re exhausted. Give yourself a few days to really rest. Lie on a sofa and watch movies, take long walks in the hour just before dusk, go out to dinner with friends, or take a mini-vacation somewhere restful. Do so with intention to give yourself—and your brain—a rest. No thinking about your novel for a week! In fact, no heavy thinking for a week. Lie back, have a margarita, and chill. Once you’re rested, you’ll likely find the desire to write has come roaring back.

Have you ever wondered why ideas seem to come easier when you’ve stopped concentrating and gone off to rest, shower, or mow the lawn? When you’re working on a task that requires higher level cognitive functioning, like writing, which requires intense concentration, your brain focuses like a laser on the task at hand, blocking out distractions and relying on existing neuronal connections. But when you break concentration and do something that doesn’t require focused cognitive functioning, your brain is more susceptible to distractions and thus “lets in” a broader range of information, which can lead to imagining more alternatives and making more diverse interpretations—fostering a “think outside the box” mentality and creating the milieu for an aha moment. Scientists have even found that when your brain is a little fuzzy from exertion, it’s a lot less efficient at remembering connections and thereby may be more open to new connections, new ideas, and new ways of thinking.

5. You’re Too Distracted

Few of us have the luxury of being free from distractions. Most of us have jobs, spouses, kids, and responsibilities that occupy a huge amount of our brain space. If your productivity has stalled, or your frustration level has peaked at a new high, it may be that too many other things are on your mind. For many, bill paying and prior commitments begin to nag. There’s just too much on your desk—and in your brain. When those distractions mount, it’s often easier and more productive to just stop writing and go take care of your life, to do whatever it is that is causing you to feel pressured.

Take note that, unless you’re just one of those rare birds who always write no matter what, you will experience times in your life when it’s impossible to keep to a writing schedule. People get sick, people have to take a second job, children need extra attention, parents need extra attention, and so on. If you’re in one of those emergency situations (raising small children counts), by all means, don’t berate yourself. Sometimes it’s simply necessary to put the actual writing on hold. It is good, however, to keep your hands in the water. For instance, in lieu of writing your novel:

Read novels or works similar to what you hope to write.

Read books about the setting or historical context of your novel.

Keep a designated journal where you jot down ideas for the novel (and other works).

Write small vignettes, poems, or sketches related to the novel.

Whenever you find time to meditate, envision yourself writing the novel.

Instead of feeling like a failed writer, be patient and kind toward your writing self until the situation changes. The less you fret and put a negative spin on it, the more small pockets of timemight open up. And, since you have been wise in keeping your writing brain primed, you may find it easier to write than you imagined.

For more about sparking your creativity, check out Fire Up Your Writing Brain.

October 21, 2015

5 On: Dana Kaye

In this 5 On interview, publicist Dana Kaye discusses why not to pretend to be a publicist, the question of gender bias in publishing and publicity, marketing mistakes and misconceptions, and more.

Dana Kaye (@Dana_Kaye) received her B.A. in fiction writing from Columbia College Chicago. After college, she worked as a freelance writer and book critic. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, Time Out Chicago, Crimespree Magazine, Windy City Times, Bitch Magazine, and on GapersBlock.com. This experience has been crucial to her publicity career: she has the contacts and necessary industry insight to form pertinent, widespread media campaigns.

Dana is known for her innovative ideas and knowledge of current trends. She frequently speaks on the topics of social media, branding, and publishing trends, and her commentary has been featured on websites like the Huffington Post, Little PINK Book, and NBC Chicago.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: What subject matter interested you the most when you were a freelance writer?

DANA KAYE: This may come as a shocker, but books, of course! My favorite pieces to write were author profiles or features. Not only did I love learning about their process and backstory, they were always so excited to be featured. Even the household names I interviewed seemed genuinely grateful that I was writing about them.

I would think, maybe incorrectly, that anyone who’d spend money on a fiction-writing degree would have to be passionate about writing. Why did you switch from writing to, as one of your online bios reads, “the other side of the press kit”? What kind of thoughts fed into that change in direction, and do you remember the moment when you said “this is definitely it” to taking the decisive step?

You are correct, I am passionate about writing and storytelling, and that’s why I pursued a degree in creative writing. But being on the other side of the press kit doesn’t mean I stop writing or telling stories (I mean, I’m the one who writes the press kits, after all!).

What I loved about reviewing books was that I had the opportunity to tell people what to read and bring awareness to lesser known books. However, I began to realize that reviewing books wasn’t the best way to do that; I had pressure from my editors to review certain books, and if I was assigned something, I had to review it, regardless of whether or not I liked it. I began exploring different options, and publicity/marketing seemed like the perfect fit.

When I pitch media, in essence, I’m telling the story of the author and the book and conveying why the editor or producer should want to share that story. I use the same mechanics to craft those pitches—omit needless words, use active verbs, know your audience, etc.—it just takes on a different form.

When do you most enjoy your job, and when do you least enjoy your job—even if your worst day is still pretty good?

There is no greater feeling than launching the career of a debut author or boosting a midlist author onto the bestseller lists. It’s the same reason I loved writing about books as a freelancer: I get to play a small role in helping someone’s dream career become a reality.

The worst part of my job is the fact that there’s only so much I can do. I’ve worked on books where we’ve executed a dream campaign—interviews on national morning shows, reviews in national newspapers, etc.—but because of something having to do with sales or marketing or the retailers, the book didn’t sell. Even though I knew we did our part (and did it well), it was still a huge blow when I received the sales figures at the end of the month. There are also times when, for whatever reason, the media is just not biting. Or we’ll have great media coverage but something will happen in the news cycle (Boston bombing, Hurricane Sandy) that will cause our coverage to get bumped. We can do our job to the best of our ability, but there are still things out of our control.

That and bookkeeping. Bookkeeping is the worst.

There’s a lot of valuable information in the form of blog posts at your website under 365 Days of Publicity. (I like “Top 5 Time/Money Wasters.”) That series, which should be its own book, ran in 2012. Will there be more blog posts in the future?

I’m so glad you liked the series! I thought about doing it as a book, but always thought a writer’s wall calendar would be better. Something to think about.

I did the series in 2012 in response to all the misinformation I was reading from other authors and PR firms. The blog posts also showcased my writing style and point of view as a publicist, which, in turn, expanded my brand.

Since then, I’ve focused that energy on writing for other sites like Publishing Crawl, NBC Chicago, and now Jane Friedman’s site.

In interview models like this one—an email Q&A exchange—how would you advise authors regarding their responses beyond trying to steer back to the book, and can you point to any interviews you’ve read over the years that they might use as examples to learn from in either direction: what to do, what not to do?

The toughest part about written interviews is conveying your voice. It’s important to write how you speak and not be overly formal just because the interview is written.

There are some fun written Q&As on Booklist’s website. One is the “You’re Doing it Wrong” interview with Lee Child and Joe Finder, and another is the “You’re Doing it Right” interview with Lisa Unger and Gregg Hurwitz. (Caveat: Gregg is a client and this was a result of our pitching. *Pats back.*)

5 on Publishing

I just finished reading Catherine Nichols’s piece on Jezebel, Homme de Plume: What I Learned Sending My Novel Out under a Male Name. In it, she writes, “Within 24 hours [my six submissions under the name] George had five responses—three manuscript requests and two warm rejections praising his exciting project. For contrast, under my own name, the same letter and pages sent 50 times had netted me a total of two manuscript requests.” Do you see a similar bias on the publicity side when approaching people about your clients?

Wow, what a fascinating piece!

If I’m answering based on my personal experience, no, I haven’t seen a clear bias. The same is true for authors of different races or sexual orientations. The people we pitch tend to focus on the book, on whether it sounds interesting, and on whether it will be a good fit for their audience. But maybe I’m seeing publishing through rose-colored glasses.

There are stats out there to back up this bias, like the Vida study conducted this year. Women buy more books than men, but males dominate the world of literary criticism and the books lining bookstore shelves. While it’s an important discussion to have, it’s not something I focus on or push in my media outreach.

If a (traditionally published) author doesn’t have a company publicist actively selling her book and she wants to try promoting it herself, is it a detriment to send press releases from her own email account or to make calls to radio or TV producers herself? How big of an ethics issue would it be to make a fake email account for a fake publicist in order to create the illusion of having that kind of “I’m legit, I promise” go-between? I know someone out there has to have considered it.

I really, really hope people aren’t making up fake publicists to send out email pitches. Lying is not the way to start a business relationship (and publicity is all about creating relationships).

Most reporters or producers I know aren’t fazed by authors pitching themselves. It’s when the authors aren’t professional or don’t understand pitching best practices that it gets a little dicey. I can say with confidence that a media person would rather hear from a professional author than a non-professional publicist.

If authors want to play a more active role in publicizing their titles, my recommendation is to do the research (find out what the outlets cover, who the best contact is, etc.) and to always keep your in-house person looped in on what you’re doing. As a publicist, there’s nothing worse than talking to an editor about coverage for a book, only to have the author send out another (usually less-than-professional) pitch a few days later.

On average, what kind of jump in sales can an author expect to see after six months with a publicist?

No idea. Increasing sales of a book is like launching a missile: everyone—publicity, sales, and marketing—has to turn their keys. As I mentioned earlier, you can have a great publicity campaign, but without the support of sales and marketing, you may not see the leap and sales you hoped for.

You don’t take on self-published books for reasons you explain here. But among the traditionally published authors who appreciate your particular model (social media, out-of-the-box ideas, etc.), how do you decide who and who not to take on as clients?

I consider three factors: Do I like the author? Do I love the book? Can I execute a campaign that will achieve the author’s goals? I’ll never take on a book just because I love the author or because I can market the product. I have to be able to stand behind the author/book I’m pitching.

Two part question: (a) What is the biggest or most common misconception authors have when it comes to publicity, and (b) what is the biggest or most common mistake authors make when it comes to self-promotion?

(a) That all publicity is good publicity. You should only pursue media coverage that is going to build your brand, reach your target audience, and generate sales.

(b) Not keeping their eyes on their own paper. Authors are too focused on what other authors are doing rather than focusing on what’s best for them.

Thank you, Dana.

October 20, 2015

The Feel of Real: Researching a Novel

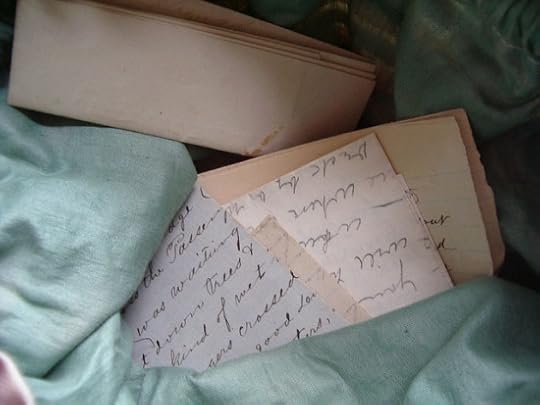

by nancy waldman | via Flickr

In today’s guest post, Maggie Kast (@tweenworlds), author of the novel A Free, Unsullied Land, discusses the role research plays in the development and evolution of a historical novel.

I’ve often been advised to write the story first, then do the research. The idea is not to get bogged down in facts while discovering the story’s narrative arc, its unique logic and necessity, its essential argument. Annie Dillard has written that writing is like “a miner’s pick,” an instrument of exploration and discovery, and so it is for me. I don’t know where I’m going until I get there, and many paths I try turn out to be dead ends. Research can kill the search, replacing story with history. So I turn from the Internet, that bottomless source of facts, and seek imaginative connections between what happened and why. Of what did the queen die? There will be plenty of time later to change that hot dog to lap cheong sausage, put the Eiffel Tower in the correct arrondissement or switch out a car for a horse and buggy. The advice against research has served me well.

But research need not be limited to objective facts or historical events. Subjective experience and memory are other forms of research that tether fiction to the real and help to satisfy what David Shields has called reality hunger, today’s yearning for the feel of reality, its touch and taste.

In 2003 my mother died, and her letters came to me, some written before she met my father, some when they were courting. Hidden between the lines on the yellowed, typewritten sheets, I found a person I had not known—a lively, sassy girl who had a clever way with words. Language for her was both gift and burden, and she suffered when they could not connect to the anguish at her core. Unable to speak or even feel her anger at her tough and disapproving mother or her fear of her temperamental and over-affectionate father, my mother knew one thing. She wanted out.

She got her wish, but at a price. The mother I knew, competent and generous, had sacrificed her verve for a safer life as stable wife and mother, later writer and community activist. I wanted to bring the girl of the letters to life, to give her adventures she never had and probably never wanted, to let her great potential play out in fiction. These letters were my first source for A Free, Unsullied Land, a novel about Henriette Greenberg’s coming of age in Chicago, 1930. Henriette is not my mother, but details of her experience, filtered through me, contribute to the sensory aspect of her world.

This process, theft and filter, is fraught for me with guilt. I take my parents’ material for my own and twist it into new form. I imitate my mother’s way with words; a few I steal. Though my parents are gone, some people living will surely take offense, and that I will regret. But I think Ma might like the time I’ve spent hanging on her words and inhabiting her world. I’ve made use of her wit and intelligence as well as her conflicts. To me the novel is a tribute to my parents, and I can only hope that they’d agree.

The letters revealed more about things of which I’d heard, like Ma’s delight at drinking “dark stuff” or “light stuff” in Prohibition’s speakeasies, her fear and dislike of the family dinner table, and her sense of entrapment by family pressures as she agonized over wedding invitations—whom to invite and whom to exclude. Foods that Ma made, like finger rolls stuffed with creamed chicken, and others that she talked about, like Mrs. William Vaughn Moody’s Lion and the Lamb, made their way into the novel. The jazz Ma loved, like Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke; the gutbelly blues of Bessie Smith, and the piano music of Jelly Roll Morton play in the background throughout the novel. Songs Ma sang, about a “thief and a gambling woman, drunk every night, ” or a canary with circles under his eyes, all contribute to the novel’s soundtrack.

Eventually the letters, like all research, threatened to overpower the story. I discarded many scenes they’d inspired and put the letters aside. More physical sources stepped in as touchstones to the real, and I found that some research could serve as prompt to my imagination. I went to see the house where Ma grew up and imagined her bed covered with childhood’s stuffed animals, then conflated this house with one where my grandmother later lived, with its screened porch, formal dining room, and kitchen filled with smells of baking bread and roasting meat.

Once a story is more or less in place, historical research comes into play. It can provide an anchor, a sort of proof that life and fiction intersect, however briefly. Today’s hunger for the real demands evidence, as though science had bled over into fiction. Critics and interviewers almost always ask writers if their stories are based on personal experience, and fictional movies often demonstrate a documentary base with archival footage or stills. I share not only hunger but delight at this intersection, as when Barbara Kingsolver, in Poisonwood Bible, grounds a fictional telling in a central factual chapter, telling the history of the CIA’s collaboration in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in Congo, with names named and dates cited.

When I decided to take Henriette to Scottsboro, Alabama, to protest the unfair trials and repeated convictions of nine young African-American men accused of raping two white women, I had to immerse myself in the long and convoluted history of this miscarriage of justice, which did not end until Governor Wallace pardoned Clarence Norris (the last still alive) in 1956, and the Alabama Board of Pardon and Parole pardoned others posthumously in 2013. When I found a telling quote, like Wade Wright’s summation for the prosecution in the second Scottsboro trial, where he said, “Show them, show them that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York,” it begged to be included. Whenever I found a luscious detail that gave the feel of real, I reshaped the writing to rope it in. The fact reworked the fiction, but the fiction also transformed the fact, altering it until the two could not be told apart. I wanted readers to learn this history, this ancestor of today’s racial abuses as well as the struggle against them, and I had to find the complex balance between Henriette’s motivations and my own.

It turned out I’d been too fearful of facts. When Fomite Press accepted my novel, editor Marc Estrin suggested that it would have broader scope with the addition of more historical material. I consulted desperately with fellow writers about whether I would lose the story (they thought not) and then read some excellent historical novels, like Colum McCann’s TransAtlantic and Amy Bloom’s Lucky Us. I got to work and added scenes and summaries about the 1927 execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Bonus March on Washington in 1932, the rise of Hitler, and other events of those tumultuous years. The result, I think, is a better book, and I am glad I took this final step.

It turned out I’d been too fearful of facts. When Fomite Press accepted my novel, editor Marc Estrin suggested that it would have broader scope with the addition of more historical material. I consulted desperately with fellow writers about whether I would lose the story (they thought not) and then read some excellent historical novels, like Colum McCann’s TransAtlantic and Amy Bloom’s Lucky Us. I got to work and added scenes and summaries about the 1927 execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Bonus March on Washington in 1932, the rise of Hitler, and other events of those tumultuous years. The result, I think, is a better book, and I am glad I took this final step.

October 19, 2015

Join Me for a Free 1-Hour Class on the Secrets of Storytelling

One of the highlights of my career at Writer’s Digest was working with Jerry B. Jenkins, the New York Times bestselling author of the Left Behind series.

As WD’s editorial director at the time, in charge of acquiring about 30 titles per year, I contacted a number of people out of the blue, with no previous relationship, just hoping I’d just get lucky. Writer’s Digest wasn’t exactly the sexiest publisher on the block. Our home office was Cincinnati, not New York; our advances were meant to be earned out; very few agents submitted work to us.

I still remember the day I sent Jerry a cold email, and he responded. And not only did he respond, but he mentioned being a longtime fan of Writer’s Digest. I hadn’t known that bit of information, but as soon as I did, I realized it was my lucky day.

In 2006, we released his book for writers, Writing for the Soul. It was the first and only book deal of mine that Publishers Weekly reported.

I’m grateful for the many relationships that I was able to start and develop while at Writer’s Digest, and I’m happy to say that Jerry and I have remained in touch.

On October 22, I’m delighted to be hosting a one-hour class with Jerry B. Jenkins on the secrets of storytelling.

He’ll be revealing the common plot mistakes he sees writers make, as well as his own personal storytelling tips—solutions that changed everything for him once he discovered them.

In case you don’t know Jerry’s story, he began as a midlist writer with average sales and became a bestselling author with the luxury of turning down offers such as my own (but fortunately he had a soft spot for Writer’s Digest!).

You can now reserve your seat for this free live class (webinar format), taking place on October 22 at 1 p.m. Eastern Time. Even if you can’t make the live event, all those who register will have access to the recording.

Seats in the live class are limited to the first 1,000 writers who sign up. The last time Jerry offered this free session, nearly 1,300 people signed up.

Why is this webinar free?

Jerry is launching a full-length online course on fiction writing, so after the webinar is over, he’ll pitch you his course. There’s no obligation, and the webinar is primarily devoted to instruction, as well as answering your questions. I receive an affiliate payment for students I refer to his course. I trust Jerry’s work and his skill in teaching writers.

I look forward to introducing you to Jerry, one of the nicest and most successful writers you’ll ever meet.

October 16, 2015

Feeling Like an Old Geezer at the New Social Media Party

I tend to pride myself on being open to new experiences, whether it’s traveling to a new country or engaging with new technology or digital media.

But with some of the emerging social networks, well, it’s been tough. I get asked by writers at conferences what the “up and coming” social media networking tool will be, and I feel like shrugging. Even though I’ve tried them all a bit, it’s hard to see how they’ll be hugely relevant. And I don’t care about them. Don’t I have enough to do already?

Simultaneously, I’m thinking: Uh-oh. This is a sure sign I’m getting old.

I have to remind myself: I originally signed up for Twitter in 2008, mucked around a bit, and abandoned it for nearly a year because I didn’t see the point. When I finally returned, I was in a better mindset to appreciate it. And now of course it’s hard to imagine life without it. (More on my Twitter story here.)

Here are a few of the “new” social media networks I’ve been mucking around in lately. For the most part, they’re not really “new,” just new to people of a certain age. They offer potential for writers who want to enjoy being an early adopter and creating a space for themselves in a community or environment that hasn’t become completely filled with marketing and promotion messages.

1. Snapchat

Snapchat is kind of like instant messaging on steroids. You can send annotated photos and videos to friends, with one big catch. After they’re viewed, they disappear. For that reason, the network tends to favor privacy and close connections.

I’ve long been disregarding Snapchat, for several reasons:

The whole point of Snapchat is that everything you send or post is completely ephemeral. Your messages self-destruct after a certain period of time. Even if you wanted to keep something around for friends to see, you can’t. From my POV, this is great if you’re a kid trying to hide things from your parents—or an adult who needs risky pictures to disappear.

The app is not intuitive. It’s not clear how to navigate it or use it, it’s not clear how reciprocal friending is, or who exactly you’re sharing things with, and if they can share things with you. Frankly, I think this is exactly the appmaker’s intention.

I have fairly limited interest in documenting my life through selfies and short videos (a major pastime of Snapchat users), and almost none of my friends are using it anyway.

What long confused me about Snapchat is that celebrities, musicians, and other public figures use it to connect with fans. But how could such an intensely private network be used to broadcast?

Well, this is going to be confusing, but try to come along for the ride anyway. There are two ways to share your photos/videos on Snapchat. You can (1) share with select friends—and whatever you share will disappear after being viewed, or you can (2) create and share Stories that are public, at least to the extent that all of your Snapchat friends can see that Story. Stories are available to be viewed for 24 hours and can be viewed repeatedly, unlike other stuff on Snapchat.

So, in a nutshell, Snapchat users can friend their favorite celebrities (I assume the celebrities are not friending back, so it’s a Twitter follow model, not a Facebook friend model), and can then see their Stories show up.

That makes it sound like it’s easy to go friend celebrities or people you don’t know on Snapchat. It’s not. In fact, it’s hard to find anyone on Snapchat if you’re not already connected somehow. However, there is a separate area where major media brands have their own “channels” (for lack of a better word) with their own stories; you’ll find CNN, Cosmopolitan, People, The Food Network, and more.

Yesterday I had a Twitter conversation with Jeffrey Yamaguchi about Snapchat, and I have to credit him for inspiring me to do this post in the first place. He thinks, and I agree, that authors could and should be experimenting with the Snapchat Stories feature.

What would such a thing look like? Well, below is an example from someone who’s been written about in the New Yorker for using Snapchat.

You can find me on Snapchat under the username janefriedman.

2. The List App

2. The List AppThe List App is getting a lot of attention right now because it just officially opened to the public, and it’s very straightforward: You create lists with it, which anyone who uses the app can read, like, save, relist, or comment on.

The lists might be very personal lists, informational lists, quirky creative lists, or collaborative lists—what’s so wonderful about this app is that it prizes creativity, imagination, and community. It has both a practical, useful side as well as a whimsical side. And it’s beautifully designed. (Hat tip to Chris Kubica for making me aware of this app.)

A few people or companies to consider following, to see and understand the potential: NPR, The New Yorker, Mollie Katzen (the cookbook author), McSweeney’s Lists, Susan Orlean.

The app allows you to include images and links with your lists, and you can also create lists that remain in draft-mode or private.

3. Periscope (and Blab)

3. Periscope (and Blab)The Periscope app allows you to broadcast your phone’s video feed so that anyone can watch and listen. (You can also save the broadcasts and make them available later.)

Michael Hyatt is the one person I’ve seen using Periscope consistently and well for professional/career purposes, and I recommend taking a look at one of his posts, What I Love About Periscope.

Periscope is kind of like a cheap way to have your own TV or radio show. Not to belabor the obvious, but you need to have the right personality to do well in a live environment, have something interesting to say (or something interesting to show), and/or something interesting to discuss.

I have not broadcast any Periscope sessions myself, but I have an account on the service should I ever become inspired.

Also see: Blab. This is very similar to Periscope, only it brings together several people for a live broadcast conversation.

After you use the apps above, I bet posting on Facebook will feel like chiseling on stone tablets, and Twitter like writing on papyrus scrolls!

Seriously, though: None of these networks are a must, but they all offer creative opportunities; I see them as a way to explore new ideas and find like-minded people, as with all social media sites.

What are your experiences with the above networks? What new social networks are you using? Let me know in the comments!

October 15, 2015

Using Newbie Attorneys in Your Fiction

by Brian Turner | via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is an excerpt from Closest to the Fire: A Writer’s Guide to Law and Lawyers, available this fall from Karen A. Wyle, herself an attorney and author of the novel Division.

Is your novel’s protagonist fresh out of law school? Here’s what you need to know about what happens when newly minted lawyers enter the work force.

New Attorneys in Paperwork Hell

In large and many mid-size law firms, associates in their first two or three years of practice rarely see the light of day, let alone the inside of a courtroom. They work very long hours to meet their ever-increasing quota of billable hours, because not everything they do counts as billable.

By the way, there’s not necessarily a consensus on the difference between billable and non-billable hours. One possible metric: if someone other than an attorney could easily and properly perform the task (e.g., making copies), any time the lawyer spends on that task is non-billable (though larger firms may itemize time spent by nonlegal staff). And any personal break of more than a few minutes shouldn’t be billable—which doesn’t mean attorneys always keep track of and deduct those breaks.

New associates in large firms may spend months or even years in “document review” for a single huge case. Document review is even duller than it sounds. These unfortunate associates spend their time going through huge amounts of paper, microfilm, and/or digital files, looking for information that can answer interrogatories (written questions sent by the opposing party’s attorney) or for documents that come within a “request for production” or “subpoena duces tecum” (written requests for documents or occasionally other items, again sent by opposing counsel). And when the opposition answers their requests for documents, then these same associates must wade through the avalanche of material provided, looking for those few documents that are worth using in a deposition or at trial.

If you want your protagonist to have a professional identity crisis early in their career, stick them in document review. You could also have your young attorney crack under the strain and start doodling on or annotating the documents. Extra points if you can figure out some plausible way these alterations wouldn’t be noticed until trial, though that’s highly unlikely.

New associates may also spend a great deal of time on legal research and summarizing their research in legal memoranda. As they gain seniority, they may draft more important documents, such as trial briefs (arguing the law to the trial judge) and appellate briefs (the principal vehicle for asserting trial court error to appellate courts). They may also act as second chair at a trial, lugging files to and from court, taking notes, and handing exhibits to the attorney actually trying the case.

New Attorneys in Trial Work

Some new attorneys actually do try cases. The best quick path to trial experience is to work for the prosecutor’s office or for the office of the public defender. While most criminal prosecutions end in a plea bargain, there are so many criminal cases in most counties that both prosecutors and defense attorneys generally try cases years before junior associates in private practice.

A small, small-town practice will also offer more trial work than the law-firm life. And then there’s good old nepotism: a young lawyer in Daddy’s (or, increasingly, Mommy’s) law firm might get to try cases before their peers.

Less likely but still feasible ways for your protagonist to get thrown into trial work ahead of schedule could include an urgent request from a friend who (possibly for reasons of local and/or judicial politics) doesn’t trust other available attorneys; or the sudden incapacity of the more senior lawyer who was supposed to try the case, where the young attorney is intimately familiar with the details and it’s for some reason impossible to delay the trial. (Delays of trials, called continuances, are extremely common, with multiple continuances possible in a single case, so you’ll need to have a reason that no continuance will be granted.)

Of course, your new lawyer might try hanging up a shingle as a solo practitioner. However, unless the community is isolated or impoverished enough to be short of lawyers, it’ll be hard for the newbie to drum up any business. It might help if they have lifelong contacts with the community; but on the other hand, having everyone know the new lawyer as the Henry boy or the Jameson girl, who should really still be wearing short pants or puffy skirts, could be a hindrance when it comes to the locals entrusting them with their funds or their freedom.

In most law firms, even if the firm handles work in several areas of the law, an associate will be assigned to only one at a time. Some firms rotate young associates through different departments, while others hire new attorneys to work in a specific area and stay there. Someone in a very small firm may handle any business that walks through the door, from contract disputes to divorces to negligence to criminal law, but so general a practice is the exception even for small firms and solo practitioners. It’s often better business to develop a reputation for expertise in one or two areas.

Paralegals and Secretaries

To whom can an attorney turn for help with paperwork, legwork, or other tasks?

Law firm support staff typically include secretaries, receptionists, office managers, and the often-indispensable paralegals. Paralegals may do much of the grunt work otherwise assigned to new associates, from witness interviews to document review to preliminary legal research. If, however, they’re called upon to write legal documents, they never sign anything they write; and it would be quite risky for a lawyer to send out a paralegal’s work product without reviewing it first. Larger law firms handling family law (divorce or custody) work, insurance defense, and/or criminal law may have a private investigator on retainer or even on staff. A smaller firm in these areas of practice would hire an independent investigator as needed.

Junior associates will almost certainly share a secretary with one or more other attorneys. This can be quite frustrating if, as is often the case, the secretary also works for a senior associate or a partner. Even though the senior attorney may be the one expecting the newbie to turn out work in a hurry, the newbie’s work is last on the secretary’s priority list. This will be a more important obstacle if your story is set before personal computers became standard equipment for professionals. If every document a lawyer turns out has to be typed (from  handwritten or audiotape drafts) by a secretary, and then revised by the same secretary, that secretary holds the lawyer’s fate in her (in that era, almost certainly her) hands. The evolution of a new lawyer’s relationship with an experienced and possibly prickly secretary could be an important secondary theme in your story.

handwritten or audiotape drafts) by a secretary, and then revised by the same secretary, that secretary holds the lawyer’s fate in her (in that era, almost certainly her) hands. The evolution of a new lawyer’s relationship with an experienced and possibly prickly secretary could be an important secondary theme in your story.

For more expert guidance in using attorneys in your fiction, pick up a copy of Closest to the Fire, available in print and digital editions.

October 13, 2015

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published

It’s the most frequently asked question I receive: How do I get my book published?

This post is regularly updated to offer the most critical information for writers new to the publishing industry, and to provide a starting point for more fully exploring what it means to try and get meaningfully published.

I’ve also created an Amazon list of the best resources on this topic.

If you’d like an in-depth guide on how to get your book published, consider my book on the topic: Publishing 101: A First-Time Author’s Guide.

This post focuses on traditional publishing.

In a traditional publishing arrangement, the publisher pays you for the right to publish your work for a specific period of time. Traditional publishers assume all costs and pay the author an advance and royalties.

How do you find or get a traditional publisher to work with you? You must persuade them to accept your work and offer you a contract. You can do this by pitching them via mail or at a conference, or by finding a literary agent.

If you’re wondering how much it “costs” to publish, then you’re not thinking of traditional publishing, but self-publishing. I have a separate post on how to self-publish.

A Brief Note for Young Writers

I receive emails daily from tween and teenage writers who wonder about age requirements for getting published. You don’t have to be any particular age to write and publish a book. When I worked at a traditional publishing house, I even signed an author who was still in high school, but his parents also had to sign his publishing contract because he was a minor. However, before you decide to jump into the publishing world, consider the following:

You get better at writing as you do more of it. Focus on your writing, not so much on publishing.

Look for a teacher or mentor who can guide you. Seek out other writers your own age and share work with each other. Start a writing group at your school if there isn’t one.

If you’re itching to get your writing out there, and want readers beyond your own circle, consider Wattpad. It’s a friendly community of writers and readers, with many people your own age.

5 Basic Steps to Getting a Book Published

Getting your book published is a step-by-step process of:

Determining your genre or category of work.

Assessing the commercial potential of your work.

Researching the appropriate agents or publishers for your work.

Reading submission guidelines of agents and/or publishers.

Submitting your materials to agents and/or publishers.

1. Determine Your Work’s Genre or Category

First, are you writing fiction or nonfiction? Novelists (fiction writers) follow a different path to publication than nonfiction authors.

Novels and memoirs: Finish your manuscript before approaching editors/agents. You may be very excited about your story idea, or about having a partial manuscript, but it’s almost never a good idea to pitch your work to a publishing professional at such an early stage. Finish the work first—make it the best manuscript you possibly can. Seek out a writing critique group or mentor who can offer you constructive feedback, then revise your story. Be confident that you’re submitting your best work. One of the biggest mistakes new writers make is rushing to get published. In 99% of cases, there’s no reason to rush.

For most nonfiction: Rather than completing a manuscript, you should write a book proposal—like a business plan for your book—that will convince a publisher to contract and pay you to write the book. Find out more information on book proposals and how to write one. You need to methodically research the market for your idea before you begin to write the proposal. Find other titles that are competitive or comparable to your own; make sure that your book is unique, but also doesn’t break all the rules of the category it’s meant to succeed in.

Fiction genres

Some of the most common novel genres are: young adult, romance, erotica, women’s fiction, mystery, crime, thriller, and science fiction & fantasy. Work that doesn’t fall into a clear-cut genre is sometimes called “mainstream fiction.” Literary fiction encompasses the classics you were taught in English literature, as well as contemporary fiction (e.g., Jonathan Franzen, Margaret Atwood, or Hillary Mantel). But there’s a lot of disagreement as to what “literary fiction” is.

Here’s an excellent summary of novel genres.

Nonfiction categories

Some of the most popular nonfiction categories are business, self-help, health, and memoir. Within the publishing industry, nonfiction is often discussed as falling under two major, broad categories: prescriptive (how-to, informational, or educational) and narrative (memoir, narrative nonfiction, creative nonfiction). You can get a sense of what nonfiction categories exist by browsing Amazon’s categories (see lefthand navigation) or simply visiting a bookstore.

2. Assess Your Work’s Commercial Potential

There are different levels of commercial viability: some books are “big” books suitable for Big Five traditional publishers (e.g., Penguin, HarperCollins), while others are “quiet” books, suitable for mid-size and small presses. The most important thing to remember is that not every book is cut out to be published by a New York house, or represented by an agent, but most writers have a difficult time being honest with themselves about their work’s potential. Here are some rules of thumb about what types of books are suitable for a Big Five traditional publisher:

Genre or commercial fiction: romance, erotica, mystery, crime, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, young adult

Nonfiction books that would get shelved in your average Barnes & Noble or indie bookstore—which requires a strong hook or concept and author platform. Usually a New York publisher won’t sign a nonfiction book unless they anticipate selling 10,000–20,000 copies minimum.

Works that can be a tough sell—again, if you’re looking at traditional publishers:

Books that exceed 120,000 words, depending on genre

Poetry, short story, or essay collections–unless you’re a known quantity, or have a platform

Nonfiction books by authors without expertise, authority, or visibility to the target audience

Memoirs with common story lines—such as the death of a loved one, mental illness, caring for aging parents—but no unique angle into the story (you haven’t sufficiently distinguished your experience—no hook)

Literary and experimental fiction

To better understand what sells, buy a subscription to PublishersMarketplace.com, and study the deals that get announced. It’s a quick education in what commercial publishing looks like.

If your work doesn’t look like a good candidate for a New York house, don’t despair. There are many mid-size houses, independent publishers, small presses, university presses, regional presses, and digital-only publishers who might be thrilled to have your work. You just need to find them. (See Step 3.)

The Question of Quality

If you write fiction or memoir, the writing quality usually matters above all else if you want to be traditionally published. Read in your genre, practice your craft, and polish your work. Repeat this cycle endlessly. It’s not likely your first attempt will get published. Your writing gets better with practice and time. You mature and develop.

If you write nonfiction, the marketability of your idea (and your platform) often matter as much as the writing, if not more so. The quality of the writing may only need to be serviceable, depending on the category we’re talking about. (Certainly there are higher demands for narrative nonfiction than prescriptive.)

Deciding If You Need an Agent

In today’s market, probably 80 percent of books that the New York publishing houses acquire are sold to them by agents. Agents are experts in the publishing industry. They have inside contacts with specific editors and know better than writers what editor or publisher would be most likely to buy a particular work.

Perhaps most important, agents negotiate the best deal for you, ensure you are paid accurately and fairly, and run interference when necessary between you and the publisher. The best agents are career advisers and managers.

Traditionally, agents get paid only when they sell your work, and receive a 15% commission on everything you get paid (your advance and royalties). Avoid agents who charge fees.

So … do you need an agent?

It depends on what you’re selling. If you want to be published by one of the major New York houses (e.g., Penguin, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, etc), probably.

If you’re writing for a niche market (e.g., vintage automobiles), or have an academic or literary work, then you might not need one. Agents are motivated to represent clients based on the size of the advance they think they can get. If your project doesn’t command a sizable advance (at least 5 figures), then you may not be worth an agent’s time, and you’ll have to sell the project on your own.

For a fuller discussion of literary agents, click here.

3. Research Publishers and Agents Appropriate for Your Work

Once you know what you’re selling, it’s time to research which publishers or agents accept the type of work you’ve written. Again, be aware that most New York publishers do not accept unagented submissions—so this list includes where to find both publishers and agents. This is not an exhaustive list of where you can find listings, but a curated list assuming you want to focus on the highest-quality sources.

WritersMarket.com. Thousands of listings can be found here—it’s by far the best place to research book publishers. You’ll have to pay a modest monthly fee to access their database. You can also purchase the print edition, which comes with free access to the online database.

PublishersMarketplace.com. This is the best place to research literary agents; not only do many have member pages here, but you can search the publishing deals database by genre, category, and/or keyword to pinpoint the best agents for your work. Subscription required.

AgentQuery.com. About 1,000 agent listings and an excellent community/resource for any writer going through the query process. Free.

QueryTracker.net. About 200 publisher listings and 1,000 agent listings. Basic service is free.

Duotrope.com. Geared toward the literary market; very useful if you’re shopping around poetry, short stories, essays, or literary novels. Subscription required.

4. Read the Submission Guidelines and Prepare Your Materials

Every agent and publisher has unique requirements for submitting your materials. The most common materials you’ll be asked for:

Query letter. This is a 1-page pitch letter that gives a brief description of your work. (More on this below.)

Novel synopsis. This is a brief summary (usually no more than 1-2 pages) of your story, from beginning to end. It must reveal the ending. Here’s how to write one.

Nonfiction book proposal. These are complex documents, usually 20-30 pages in length, if not double that. For more explanation, see my comprehensive post.

Novel proposal. This usually refers to your query letter, a synopsis, and perhaps the first chapter. There is not an industry standard definition of what a “novel proposal” is.

Sample chapters. When sending sample chapters from your novel or memoir, start from the beginning of the manuscript. (Don’t select a middle chapter, even if you think it’s your best.) For nonfiction, usually any chapter is acceptable.

The All-Important Query Letter

The query letter is the time-honored tool for writers seeking publication. It’s essentially a sales letter that attempts to persuade an editor or agent to request a full manuscript or proposal.

Here’s my 4,000-word definitive post on writing a query for a novel.

See my favorite how-to post on novel queries by Marcus Sakey.

For special considerations related to memoir, reference this post.

5. Submit Your Materials

Almost no agent or editor accepts full manuscripts on first contact. This is what “No unsolicited materials” means when you read submission guidelines. However, almost every agent or publisher will accept a one-page query letter unless their guidelines state otherwise. (If they do not accept queries, that means they are a completely closed market.)

After you send out queries, you’ll get a mix of responses, including:

No response at all, which is usually a rejection.

A request for a partial manuscript and possibly a synopsis.

A request for the full manuscript.

If you receive no requests for the manuscript or book proposal, then there might be something wrong with your query. If you succeed in getting your material requested, but then get rejected, there may be a weakness in the manuscript or proposal.

How Long Should You Keep Querying?

Some authors are rejected hundreds of times (over a period of years) before they finally get an acceptance. If you put years of time and effort into a project, don’t abandon it too quickly. Look at the rejection slips for patterns about what’s not working. Rejections can be lessons to improve your writing.

Ultimately, though, some manuscripts have to be put in the drawer because there is no market, or there isn’t a way to revise the work successfully. Most authors don’t sell their first manuscript, but their second or third (or fourth!).

Protecting the Rights to Your Work

You have nothing to fear in submitting your query or manuscript to an agent or publisher. If you’re worried about protecting your ideas, well, you’re out of luck—ideas can’t be protected under copyright, and no publisher or agent will sign a nondisclosure agreement or agree to talk with a paranoid writer who doesn’t trust them. (Just being blunt here.)

If you’re worried about protecting your copyright, then I have good news: your work, under law, is protected from the moment you put it in tangible form. You can find out more about protecting your rights here.

Do you have to “know someone” to get your work read or considered?

No, but referrals, connections or communities can certainly help! See the related question below about conferences.

The Self-Publishing Option

Typically, writers who get frustrated by the endless process of submission and rejection often look to self-publishing for satisfaction. Why waste countless months or years trying to please this or that picky agent/editor when you can easily get your book available on Kindle (or as print-on-demand) at almost no cost to you?

Such options may afford you the ability to hold your book in your hands, but it rarely leads to your physical book reaching bookstore shelves—which ends up surprising authors who’ve been led to believe otherwise.

Self-publishing requires significant and persistent effort into marketing and promotion, not to mention an entrepreneurial mindset. It usually takes a few books out on the market before you can really gain momentum, and most first-time authors don’t like to hear that—they’re not that committed to writing without an immediate payoff or some greater validation.

Finally, most self-published authors find that selling their book is just as hard—if not harder than—finding a publisher or agent.