Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 144

September 7, 2015

2 Stammer Verbs to Avoid in Your Fiction

by Hernán Piñera | via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by editor Jessi Rita Hoffman (@JRHwords).

As a writer, you’ve probably heard the advice about avoiding passive voice and colorless verbs, such as is, was, went, and so on. But you may not be aware of what I call the “stammer verbs” that mar the novels of many budding authors.

I call them that because they halt the flow of a scene. Just as stammering halts speech, stammer verbs halt the flow of a written sentence. The author uses these verbs as if stammering around while searching for the genuine words she’s intending.

As a book editor, I find two verbs in particular repeatedly used in a stammering way by many beginning novelists. Let’s take a look at these little suckers and identify why they pose problems for your story.

Turned

Ever notice how often you write “he turned” or “she turned” when you’re describing a character in your novel doing something? I suspect we all do this, in our first drafts.

The king placed the scroll back on the table. He turned and walked to the window.

Libby stared at her brother, unable to believe what she had just heard. She turned, went to the door, and walked out.

Notice how turned adds nothing to the description in these two examples. The reader assumes, if a character is going to move from point A to point B in a scene, he or she will probably have to make a turning movement. That’s understood, so it need not be explained. Stating it merely slows down the action and spoils the vividness of the scene.

In the first example, rather than say he turned and walked to the window, it’s tighter writing to simply say he walked to the window. Better yet would be to describe how the king walked: he strode to the window, or he shuffled to the window.

The king placed the scroll back on the table. He shuffled to the window.

In the second example, She turned, went to the door, and walked out could be tightened to read She went to the door and walked out. A further improvement would be to get rid of went (a colorless verb) and to tell us how Libby walked:

Libby stared at her brother, unable to believe what she had just heard. She stormed out the door.

Libby stared at her brother, unable to believe what she had just heard. Crying, she hurried out the door.

Notice I didn’t suggest She walked sadly out the door, because it’s better to nail the exact verb you’re looking for than to use a lackluster verb (like walked) and try to prop it up with an adverb (like sadly).

Began

Began is another stammer verb that tends to creep into our writing unless we keep a watchful eye. Like turned, it’s typically misused as a way of launching into description of an action:

Jill sat down with a thud. She began to untie her shoelaces.

Jon put down the letter. He began to stand and pace the room.

There’s no reason to slow down the action in either of these examples with began. See how much tighter this reads:

Jill sat down with a thud. She untied her shoelaces.

Jon put down the letter. He stood and paced the room.

Or perhaps better still:

Jon put down the letter. He paced the room.

Unless something is going to interrupt Jon or Jill between the start and the completion of their action (standing, taking off shoes), there is no reason to say began. Can you see why began would be okay to use in the following sentences?

Jill began to take off her shoes as a spider made its way up her shoelace.

Jon put down the letter. He began to stand, but the man shoved him back down into the chair.

In these examples, began is appropriate, because something is being started, then interrupted. That’s not the case when began is just used as a stammer word.

Turned and began … Once you become sensitive to how these two stammer verbs infiltrate story writing, you’ll find yourself recognizing them as they pop up and naturally weeding them out. Like so many writing problems, the remedy is greater awareness.

Your turn: Are there other “stammer verbs” that annoy you? Tell us about additional verbs you would identify as “stammering” in place of efficient storytelling.

September 2, 2015

Learning to Practice Self-Care as Writers

photo by Arnold Poesch

Many times when I consult with writers, I find myself granting them permission to do less work, or to put less pressure on themselves. It always reminds me of how fond Alan Watts was of saying, “The nice thing about hitting your head with a hammer is it feels so good when you stop.” To feel unburdened and happy, we sometimes have to feel the opposite way to appreciate it.

Over at the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, Carmiel Banasky writes about the connection between self-work and self-care. She writes:

We “surrender” ourselves to our art, T.S. Eliot wrote. I hate to argue with the Master, but I’m not sold on the metaphor of war that’s implied. Instead, I think of my dynamic with writing as the most equal relationship I’ve ever been in. There is a give and take. Sacrifice, yes, but not “a continual extinction of personality.” If writing means an increase of empathy, then it cannot mean the killing or erasure of the empathizer.

Read her full piece, “Do we become better people as we become better writers?”

Also this month at Glimmer Train:

Autograph Seekers by Caleb Leisure:

On Literary Heroes and Loneliness by Siamak Vossoughi

September 1, 2015

Self-Publishing Beyond the Book: Serializing, Podcasting, and Merchandising

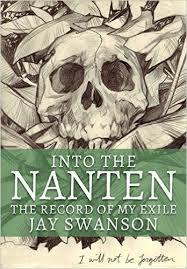

Fantasy novelist Jay Swanson (@jayonaboat) has been writing and self-publishing fiction since 2011. His first trilogy (The Vitalis Chronicles) received strong reader reviews, but what really caught my attention was his recent launch of a real-time fantasy blog, Into the Nanten.

Here’s the premise: The Nanten is a jungle so hostile that to enter it willingly is considered suicide. Marceles na Tetrarch is exiled to the Nanten for murder, and he goes searching for a man who was exiled there 20 years ago, Brin Salisir. It’s rumored that Salisir went into the Nanten to find a cult risen from the darkest dregs of humanity. What Marceles doesn’t know is if the rumors are true.

To call Into the Nanten a live blog is to really understate what it is—a multimedia universe of offerings (as we discuss below). After the first “season” ended, Swanson successfully Kickstarted funds for the second season, starting on Sept. 9. He was gracious enough to answer my questions about the nature of his project, and what has worked to build word of mouth for it.

The first season of Into the Nanten was an ambitious undertaking—I mean, you manage a full-fledged site for the serialization, have an illustrator doing incredible artwork, have a merchandising component, and promote the content on multiple social media channels. You’d written other books before, of course, but what made you pursue this type of more complex production—and what level of confidence did you have in your multimedia approach?

Insanity is a common source of confidence, thankfully. I’ve been wanting to serialize something in my world for a long time and have a number of projects that I started but never made the cut. Examples would include a book of parables (I think I have 60 or so finished), and another book on the history of magic in my world from the perspective of a later-era anthropologist. That one was tons of fun to write—I did the whole thing by hand while living in Paris—but is (a) a bit too meta to use as an introduction to my world, and (b) contains too many spoilers.

I’ve always been one for ambitious projects—it doesn’t feel right if I’m not challenged to complete something. I’ve had my hand in web and graphic design for a long time, so approaching Into the Nanten felt like pulling a lot of disciplines I enjoy into one single project.

My confidence hasn’t ever wavered in the face of the creation process, but there have been moments in the execution that I wasn’t so sure were going to come through. I’ve had a few ulcer-inducing incidents, like photoshopping and uploading an entry from the back of a taxi on the way to O’Hare, laptop tethered to my cell phone in rush hour traffic.

I definitely try to avoid those.

During your first year, did you find there was a particular strategy or tactic that really increased your discoverability and led to more readers?

It feels like we work pretty hard for each reader, but once we’re in front of people they tend to stay. Cutting through the noise is the single greatest challenge in the project overall—and ultimately that’s the underlying purpose for it in the first place. There aren’t a lot of things out there like Into the Nanten, so we’re carving our audience out by hand. The biggest successes have come from direct communication—whether through the Kickstarter or in person at conventions. You can see the light turn on when you explain the concept to people, and as long as they enjoy reading in the journal format, it’s a really easy sell.

I carry business cards around with me everywhere, the backs of which prominently display a variety of artwork from the first season. I have to order them by the hundreds now because they tend to just walk off. There are no analytics for business cards, and I wouldn’t suggest them for just any project, but they certainly generate strong responses up front. Before these, I’ve never had a set of business cards that people wanted to take in triplicate.

I would say that the “traditional” ways of finding an audience haven’t worked well for us: Facebook ads, Google Adsense, and the variety of other options (from Goodreads to BookBub). We could probably experiment more, but the return on investment on those services has been weak at best for us.

Obviously the first season of Into the Nanten went well enough that you were able to raise $7,000 from 111 people to support a second season. How would you describe these supporters?

Generous. Magnificent. Superfluously wonderful.

Our Kickstarter backers are a mix of known entities and total surprises. Some were friends or family, some discovered us through the Kickstarter, and a surprising number were fans who didn’t even want anything in return. After a lot of people backed us without claiming a reward, I posted an update to remind people to do so in case they’d missed that step—almost immediately I received a response that basically said “I love this story and just want to give back!” That wound up being how around 10% of our backers felt.

Aside from the Kickstarter income, what’s so far been the biggest source of revenue for this project?

Surprisingly, book sales. We’ve been slow to get the online store up, but the No. 1 seller both at conventions and online right now is the paperback copy of Into the Nanten. It’s surprising because, being full color, it’s pretty expensive to produce and thus to sell ($29.99). There were a lot of people who told me it was too costly, but my hands were effectively tied if I wanted bookstores to carry it. Few people who have picked it up have even blinked at the price point—I know because I sold out of them in person at Sasquan two weeks ago.

Surprisingly, book sales. We’ve been slow to get the online store up, but the No. 1 seller both at conventions and online right now is the paperback copy of Into the Nanten. It’s surprising because, being full color, it’s pretty expensive to produce and thus to sell ($29.99). There were a lot of people who told me it was too costly, but my hands were effectively tied if I wanted bookstores to carry it. Few people who have picked it up have even blinked at the price point—I know because I sold out of them in person at Sasquan two weeks ago.

We won’t be using advertising on the website at any point, largely because I don’t want to break up our attempt at an immersive experience. I also think that advertising is a flawed system for monetizing content and hope to find alternate ways to keep the project alive (some of which we have brewing in the lab right now).

I’m really excited to see how things go when we release Shadows of the Highridge, a standalone novel that ties into Into the Nanten which we’ll make available in October. It grows the scope of the project significantly, and will give people a new insight into Salisir’s history that they would never get through Marceles’ perspective. My hope is that Into the Nanten, being free, is a low-barrier way to give people a taste for my world and my writing that leaves them wanting more.

I know you’ve only just released the audio edition of Into the Nanten, so it might be too soon to say, but what impact have you seen from that effort?

I’ve gotten a lot of great feedback from the people that have listened to it so far. Audio opens us up to an entirely different market, which is why I think it’s necessary. I have a handful of friends who have told me for years that they would never read my books, but that they would listen to them. Most of them have already devoured Into the Nanten. I’ve discovered the same is true at conventions and in random conversations—there are a lot of people out there who get excited about new audio projects who prefer not to read.

We’ll see what happens. I know we’ll learn a lot as we work to run the world’s first real-time fantasy podcast this year (at least we think it’s the first).

Biggest surprise so far with this project?

I’m still vertical.

Perhaps the second biggest surprise is that it worked. At its core, Into the Nanten is a really entrepreneurial project, so there’s been plenty of room for failure. There still is. Without the support of our friends, fans, and Kickstarter backers, we’ll die in the water pretty quickly. I guess that’s where the adventure lies for me and, in the end, what has made it such a satisfying project.

I’ve survived so far. Now to see if we can keep Marceles alive as well.

Read the beginning of Into the Nanten, and find out more about Jay.

August 28, 2015

Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before Using Copyrighted Material

by Kit Logan via Flickr

Note from Jane: This guest post is by attorney Bradlee Frazer has been updated to address reader questions and offer more information about fair use. Be sure to read his previous posts:

Q&A on Copyright—plus his 101 post on copyright

Guidelines on using trademarks in your work

You might also want to reference my post: When Do You Need to Secure Permissions?

Authors create copyrights when they express their ideas into or onto a tangible medium. This means the author has the right to make copies of the work; the right to create derivative works; the right to distribute copies of the work; the right to publicly perform the work; the right to display the work; and, in the case of sound recordings, the right to perform the work by means of a digital audio transmission.

If you are the sole owner of the copyright to a work, you are the only one who may lawfully do these things or sell/license the rights to someone else to do these things. Conversely, doing one or more of these things without the copyright owner’s permission is called copyright infringement.

One defense against copyright infringement is fair use. Fair use allows you to use someone’s copyrighted work without permission. However, invoking fair use is not a straightforward matter.

The fair use doctrine is defined here. To bring your otherwise unauthorized use within the protection of the doctrine, there are two separate and important considerations. First, your use must be for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research.”

This is the first prong. If your use falls into one of these categories, then you move to the second prong of the test. A court will consider the following four factors to determine if your use is a fair use:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (emphasis added)

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

If your use falls into one of the enumerated categories AND you are able to prevail factually on at least two of the four second-prong factors, you might succeed in proving that your use is fair and thus not copyright infringement.

Here’s an example.

Let’s say you are writing a novel for commercial publication and you wish to reproduce the lyrics to the song “Little Red Corvette” by Prince in the book. You are not reproducing the sheet music, and you are not including a sound recording of the song with the book. You are merely causing the literal words of the lyric to appear as prose within your book. Here is the analysis:

Do you own the copyright to the work? No. The author and copyright claimant of these song lyrics are Prince Rogers Nelson (Prince’s real name).

Do you have Prince’s permission? No.

Is your use for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research”? No. You are writing a novel.

Is the purpose and character of the use commercial or noncommercial? Commercial.

What is the nature of the underlying work you are reproducing? Is it highly creative and subject to strong copyright protection, or is it less creative or perhaps even not subject to copyright protection at all? This is a highly creative work that is entitled to strong copyright protection.

Did you use the whole lyric or just a few words? You used the whole lyric.

Will your use of the lyric cause Prince to lose money, e.g., people will not download the song on iTunes anymore? No, your use will likely not cause Prince to lose money.

Of all the fair use factors, you would only perhaps win on one of them, the last one, so if Prince sued you, you would likely not be able to successfully invoke the fair use defense. Other defenses may be available, but probably not fair use.

In each case where you wish to use someone else’s work, and wish to invoke the fair use defense, you should ask those seven questions.

Not all situations call for invocation of the fair use defense. For example, if you only want to use the title of another work, that’s not copyright infringement because titles and short phrases (fewer than ten words or so) are not subject to copyright protection. Similarly, facts are not protected by copyright, and you may use plain, unadorned, uncreative lists of facts without copyright infringement liability. If someone had, for example, prepared an alphabetical list of the fifty states, that list of facts (state names) is not protected under copyright law.

What about using quotations—is it okay?

A question like “is it OK” is hard for a lawyer to answer because in truth, the only way to know for sure if something is “OK” is by getting sued and then winning that lawsuit. Then, the judge has told you, in essence, “Yes, your behavior is OK.”

A better way to ask the question is: “If I get sued for quoting another book without seeking permission, what defenses may I posit in the lawsuit to increase the chances I will not lose?”

Answering that question is possible, and the answer is that if you copy ten or fewer words from another book you may likely be able to defend yourself under the doctrine that titles and short phrases are not subject to copyright protection. If you use more than 10 or 15 words, then you should ask those 7 questions above to determine how and if you might be able to invoke fair use as a defense if you get sued for copyright infringement. This is why I tell clients to always seek permission, and to remember that attribution alone is not permission.

The big question: How risk averse are you?

Anytime you use any third-party content without permission (including quotes), you run the risk of getting sued. No amount of opining by me or another lawyer can change that fact. No one has to get permission from a judge or lawyer to sue you when you use their “stuff.”

Remember, under U.S. law:

Fair use is just and only a defense you assert after you’ve been sued.

Public domain is just and only a defense you use after you’ve been sued.

An argument that the underlying work you copied is not copyrightable subject matter because it is too short to merit copyright protection (“10-15 words or less”) is just and only a defense you use after you’ve been sued.

The arguments about the length of the quotes all fall within the realm of one of more of these defenses, but that’s all they are—defenses you use after you’ve been sued.

So, again, to my point: how risk averse are you? If you are very risk averse, you should seek and obtain permission or not use the quotes since you have no control over if they will sue you. Yes, you may have one or more defenses in that lawsuit, but do you want to get sued at all?

If you are very risk tolerant, you may wish to use the quotes hoping they will never catch you and never sue you, and if they do sue, you trust that you can assert one or more of these defenses.

Also remember that attribution is not permission and does not create a defense. Also remember that celebrities (even dead ones) can sue you for something called “a right of publicity violation” in addition to suing you for copyright infringement.

Not saying you can’t. Also not saying you can. No one knows if you can until you get sued—and win.

Can I quote a famous person if they’ve said something publicly?

Remember the definition of copyright. Answering this question turns on whether someone owns a copyright in the spoken words, i.e., have the words been reduced to a tangible medium by someone? The fact that they’ve spoken the words publicly has no bearing on the analysis. Factors to keep in mind:

If the quote is very old, say, more than 100 years old, even if it is in a tangible medium, it is likely that the copyright in that work has expired and that the quote has now entered the public domain.

If you’re using the quote as a means to sell your book, you could get sued for a right of publicity violation. (However, it is typically defensible to use someone else’s name or likeness for news, information, and public-interest purposes, but that doesn’t always rule out a violation.) Right of publicity laws vary in each of the fifty states (and publishing something online is like publishing in all states), so you have to be careful.

The right of publicity can apply to people who are dead—it varies from state to state. In general, the right of publicity survives the person’s death, in some states for as long as 75 years after they die. Some states may even be longer!

What if I’m quoting or referencing facts?

Plain, unadorned facts are not copyrightable subject matter. For example, if Sue writes down a list of the fifty U.S. states and places that list in her book, I may copy that list exactly from her book and my defense, if she sued me, would be that such a list is an unadorned list of facts and thus are not subject to copyright protection. If, however, Sally, made the list creative and made a photo collage out of it or something, copying the collage might be copyright infringement, but the underlying facts themselves are still not protected by copyright.

What about quoting, paraphrasing, or linking to online work?

There are three issues here: quoting, paraphrasing, and linking, but there is nothing fundamentally different about online works that changes the analysis. Some human being wrote the words that appear online, and that human being (or her employer or her assignee) owns a copyright in the work. If someone copies and reproduces most or all of those words somewhere else online (a) without permission; (b) without being able to invoke the Fair Use Defense; (c) without being able to argue that the original words were not copyrightable subject matter; or (d) without invoking some other defense, then that is copyright infringement.

For example, the Huffington Post can argue that it is a news outlet, and news outlets get greater latitude to argue the Fair Use Defense. Also, you can summarize another’s works without committing copyright infringement if you do not literally replicate the exact words and all you do is convey the same underlying ideas.

Lastly, in most cases you may link to another’s work, as long as you do not literally copy and reproduce all or most of the actual words at the linked story on your site.

What about recipes from cookbooks?

To the extent the recipe is just a list of facts (amounts and ingredients), it is not subject to copyright protection. When a recipe or formula is accompanied by an explanation or directions, the text directions may be copyrightable, but the recipe or formula itself remains uncopyrightable.

What about using quotes from TV, film, or advertisements?

Television, film, and advertisements are all copyrightable subject matter, and copying from them without permission is subject to the same analysis.

Please comment or e-mail me at bfrazer@hawleytroxell.com if you have any questions.

August 27, 2015

When Structure Sets You Free

by eljoja | via Flickr

Note from Jane: This fall, I’m delighted to be offering a 10-week course on The Art of the Personal Essay, taught by writer and Sweet Briar professor Nell Boeschenstein. Nell has an MFA in creative nonfiction writing from Columbia University, where she taught writing for two years. She also worked as a producer for the public radio programs Fresh Air with Terry Gross and BackStory with the American History Guys. Her work has appeared The Guardian, Newsweek, The Believer, The Rumpus, The Millions, Guernica, and The Morning News.

I don’t know about you, but for me writing often goes like this: chasing a thought in one direction and then another and then another and each time running headlong into a dead end. Or I’ll spend hours staring at the screen and come away from those hours with only a paragraph. Or I’ll write a few paragraphs I like only to realize that they are entirely irrelevant to the project at hand. Any or all of these exercises in frustration can go on for days. Depending on the scope of the project, they can sometimes last for weeks, even months. But inevitably one day when I’m about to throw in the towel, a ray of sunlight at last finds its way through the clouds of my brain, illuminating the latest answer to the perennial question that grays my hair. That question? Structure. Once I have figured out structure, every other challenge of the writing process seems a walk in the park by comparison.

Oh, structure. No moment is more rewarding than that of when it reveals itself. And yet, I’ve also found this beautiful moment to be something of a double-edged sword, and I am teaching myself to be wary. This is because every time I find the structure for a piece, some part of me becomes convinced I’ve found the ultimate key to unlocking the structure of not only the essay at hand, but of all future essays I will write. Four times out of five, I will try to superimpose the structure of my last essay onto the next one I try to write.

Spoiler alert: this rarely works. Perhaps this is trite to say, but structure is not a candidate for the cookie-cutter approach. True, there are some tried and true structures you see over and over again (the longform nonfiction in the New Yorker, in particular, comes to mind), but the fact of the matter is that every essay has its own lock to its own door and thus requires its own key. That’s not to say that structure emerges with each essay mysteriously from the mists of The Process as if The Process were a mystical unknown. Yes, sometimes you stumble across a key as you muddle your way through the writing woods, but lately I’ve found that a more reliable method of unlocking structure is (if we want to further extend the metaphor) to go to the proverbial key store like a normal person and have one made. An effective method of finding structure is simply to read for it: to look for a structure that sparks your imagination or admiration, and to challenge yourself to write a piece that cribs that structure. The idea is that constraints just might set you free.

Spoiler alert: this rarely works. Perhaps this is trite to say, but structure is not a candidate for the cookie-cutter approach. True, there are some tried and true structures you see over and over again (the longform nonfiction in the New Yorker, in particular, comes to mind), but the fact of the matter is that every essay has its own lock to its own door and thus requires its own key. That’s not to say that structure emerges with each essay mysteriously from the mists of The Process as if The Process were a mystical unknown. Yes, sometimes you stumble across a key as you muddle your way through the writing woods, but lately I’ve found that a more reliable method of unlocking structure is (if we want to further extend the metaphor) to go to the proverbial key store like a normal person and have one made. An effective method of finding structure is simply to read for it: to look for a structure that sparks your imagination or admiration, and to challenge yourself to write a piece that cribs that structure. The idea is that constraints just might set you free.

It’s an approach I’ve found useful. For example, nearly a year ago I read an essay about rain on The Awl that approached the subject from disparate angles, making an essay like a mosaic. It was a poetic structure that appealed to my affinity for associative thinking. The parts also built on themselves in such a way that, when you got to the end, you had to stop and wonder, Wait: How did she do that? I wanted to figure out how to do that. A few weeks later, I tried my hand at the mosaic structure. The structural parameters I had set for myself freed my mind to make unexpected connections, and I was pleased with the way that the piece turned out.

More recently, in the past month, I have read two wonderful essay collections: Let Me Clear My Throat by Elena Passarello and Limber by Angela Pelster (both from Sarabande Books). Each collection begins with a short essay that wallops the reader with the themes ahead in the book. The essays are so tight it’s as if they have corsets on. Fearing that I was becoming too prone to writing too long, I set about writing my own corseted essay. I finished a draft last week. The jury is still out on whether or not the piece is successful, but the exercise was rejuvenating. That’s another way of saying that it pushed me. It challenged me. It also saved me from having to think too much about structure because I’d gone into the project with that pre-determined. And for that I am grateful.

More recently, in the past month, I have read two wonderful essay collections: Let Me Clear My Throat by Elena Passarello and Limber by Angela Pelster (both from Sarabande Books). Each collection begins with a short essay that wallops the reader with the themes ahead in the book. The essays are so tight it’s as if they have corsets on. Fearing that I was becoming too prone to writing too long, I set about writing my own corseted essay. I finished a draft last week. The jury is still out on whether or not the piece is successful, but the exercise was rejuvenating. That’s another way of saying that it pushed me. It challenged me. It also saved me from having to think too much about structure because I’d gone into the project with that pre-determined. And for that I am grateful.

Learn more about Nell’s 10-week course, The Art of the Personal Essay, starting Sept. 28.

August 26, 2015

5 On: Sandra Gulland

In this 5 On interview, Sandra Gulland discusses the delicate process of blending fact and fiction, the allure of unhappy endings, the publishing industry then vs. now, preparation for public readings/signings, and more.

Sandra Gulland (@sandra_gulland) is an internationally bestselling author of biographical historical fiction. She is known for the depth and accuracy of her research, as well as for creating novels that bring history vividly to life. She is published by Simon & Schuster and Doubleday in the US, and HarperCollins in Canada. The popular Josephine B. Trilogy about Napoleon’s wife, Josephine, published in fifteen countries, is under option for a television drama series. Mistress of the Sun and The Shadow Queen, set in the mid-seventeenth-century French court of Louis XIV, the Sun King, are published internationally as well.

Gulland is now writing two young adult novels about Josephine’s daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, for Penguin. A self-confessed “Net nerd,” she has created her own e-book imprint—“Sandra Gulland INK”—in order to ensure that her novels remain available worldwide.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: When you decided you wanted to devote the bulk of your time to writing, you were able to quit your job because, you said, “My husband is my patron. And his business enabled me, at that point in our life, to give up money work.” But you added that publication didn’t necessarily happen right away, and then you made a reference to van Gogh, who “never sold a painting.”

What was the period of writing but not publishing like before your work sold? Were you comfortable with the arrangement, or did you experience any doubts about the decision you’d made? Did you set a deadline (“If I don’t get published in X number of years, I’ll go back to work”)? (I ask this as someone whose spouse has made it possible to stay home and write and who feels like a mooch at least once every other week.)

SANDRA GULLAND: I’d always been self-supporting, and I really disliked being dependent financially, but writing was important to me, so it was worth it. It helped that my husband was supportive, insisting that I write even if I never sold a book.

When I was in the doldrums, despairing about the possibility of ever getting published, he was the one who said, “Think of van Gogh!”

I don’t recall ever having a fallback plan or a deadline. I am compulsively persevering, so I suspect I simply had faith.

After compiling stacks and stacks of mental and physical files and folders of information on the person or people you’re researching for a novel, how do you decide which of their arcs to explore?

After compiling stacks and stacks of mental and physical files and folders of information on the person or people you’re researching for a novel, how do you decide which of their arcs to explore?

In deeply researching a person’s life, it’s fairly easy to uncover the significant threads. The relationships with the people they love, of course. Family. Health is another that is often overlooked—yet it can be central. I find it especially worthwhile to explore a character’s aspirations—her dreams and fantasies. This was key to understanding Napoleon, for example, who was such a dreamer, and Louise de La Vallière (of Mistress of the Sun), who was profoundly religious.

Some subjects, however, simply do not translate into good fiction, and should not be used, even if it is something central to the character. For example, the disastrous inflation in France after the Terror meant that everyone became a scavenger, a wheeler and dealer—including Josephine. I hinted at this in the Trilogy, but I dared not do very much with it. The ups and downs of a national economy do not make for readable fiction.

Ultimately, I’m looking for those threads, those moments, that illuminate the character, that make the story come alive.

You said in a Simon & Schuster discussion, “I am a fan of what I would call literary historical novels—slow, gritty but poetic novels that often end unhappily.” Do the novels you enjoy happen to end unhappily, or do you enjoy the novels in part for their unhappy endings? And, generally, what makes a sad ending appealing to readers, do you think?

As a rule, literary fiction tends to end unhappily, and I like to read literary fiction, so the two go hand in hand. There’s something rather poignant about closing a novel tearfully. That said, I don’t seem to be averse to a happy ending these days. The stories of each of my heroines do not end happily, at least not in the traditional sense, yet they are satisfying.

Creating characters from scratch and plopping them in the past is one thing, but you write about real people with real pasts. Can you describe the process of creating a fictionalized story for someone you’ve thoroughly researched? In your novels, how much is historical fact and how much is fiction, and how do you decide where to veer off?

Like many writers, I find plot difficult, and I mistakenly thought that writing biographical historical fiction would be easy, given that the plot would already exist. How wrong I was! If anything, it’s more of a challenge, because one must create plot within the confines of fact.

I first create a detailed timeline of events. This can run to hundreds of pages.

Then I identify the key events and look for story arcs.

And then the fun begins: sculpting the facts to create story. I’m currently fond of using story beats as outlined by Blake Snyder in Save the Cat, and so I’m identifying the “Catalyst,” the “Promise of the Premise,” and so forth.

In identifying key themes, I must also decide what not to include. The worlds of the past were densely populated, each moment swarming with characters. I must cut, cut, cut!

I think of facts as the bones of the story. When I deviate—as I must, since a compelling story is the goal—I will acknowledge it in the Author’s Note. That said, there is always a great deal that is not known. I like to think that the scenes I create whole cloth could have possibly happened. In fact, I think a writer of fiction can get close to the truth in this way.

History, in particular any dramatic telling of it, is undeniably alluring. It’s almost impossible to not be drawn to the mystery of a time we can never experience in any way but through storytelling. But the people who were alive in what’s now to us a historical period were no more interesting to themselves than we are to ourselves: getting up in the morning, putting on the clothes that were fashionable (or not so fashionable) at the time, taking or avoiding appointment cards.… Who from our time do you think will inspire historical fiction writers in a hundred years, and what seemingly mundane details of our daily lives do you think will be interesting to future readers?

I think that the types of daily life details that will be of interest to writers in the future will be the things we now find interesting about the past: how long it takes to get from one place to another; the way we are divided into small “enclaves” (i.e. countries); the curious types of food we eat; our short lifespan; our barbaric medical practices; our bizarre beliefs. The things that they may well neglect to convey might be the annoyance of having to crawl under desks to connect wires and the variety of cellphone ring tones.

5 on Publishing

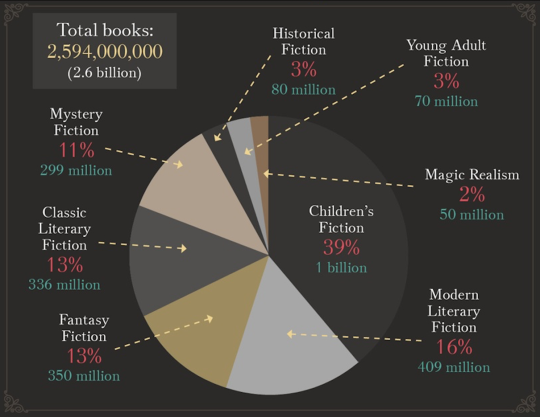

I thought I had it tough, from a publishing and readership standpoint, as someone who enjoyed writing literary-ish fiction. But this genre popularity chart created by creative search agency Mediaworks shows historical fiction sells even less than literary fiction. Obviously, a relevant question is whether how many people buy historical fiction has to do with how much historical fiction is available compared to the other genres, but that’s for another time. (It just needed saying.)

To the question: Do you write the way you want to write and you’re fortunate that readers love your natural style, or while writing do you have to consider the business end of the work, think about what will likely attract readers, and then write to that attraction?

It has always been discouraging to look at publishing statistics. There are no guarantees; there is no crystal ball. Nobody really knows.

When my agent began looking for a US publisher for my Josephine B. Trilogy, the “publishing wisdom” was that historical fiction simply did not sell, so I was roundly rejected everywhere. And then, much to everyone’s surprise, came the 1997 runaway bestseller Cold Mountain, by Charles Frazier, and suddenly historical fiction was hot. I doubt that I would have been published in the US had it not been for the success of Cold Mountain. Too, the Trilogy was rejected by all the big publishers in Europe and the UK, until a German publisher bought it, and then suddenly everyone wanted it. Publishing is much more emotional than scientific, and as maddening as that can be, I think it’s a good thing.

But to answer your question: writing a novel is such a big commitment, I have to be compelled to do it from passion or interest or compulsive curiosity, and preferably all three. Writing for potential sales does not work for me, and in any case, I very much doubt that such a work would sell.

That said, some very good writers have come to their best work in seeking a popular audience—Elmore Leonard, for example. Whatever motivates one to write can be a good thing.

Why historical fiction? I simply got hooked on Josephine’s story and one thing led to another. I think readers enjoy learning something while being under the enchantment of a story. I certainly do.

I aim to write accessible literary fiction—which I think of as Lite Lit, a term only I find amusing, apparently.

What helped the Josephine B. Trilogy sell so well was, simply, Josephine. Hers is a marquee name, and that helps when writing biographical historical fiction. Not only is Josephine known to virtually everyone, but she is a very sympathetic heroine and her life was astonishingly romantic and dramatic. All the high-concept story elements are there.

My two novels since Josephine—Mistress of the Sun and The Shadow Queen—are not about marquee historical characters, and their stories, although compelling, don’t have the epic arc of Josephine’s life, and hence have not enjoyed broad popular appeal. If commercial success was what motivated me, I would have to seek out only marquee subjects. (Unfortunately, this is more important for writers of historical fiction now than in the past.) I very much enjoy having a wide and enthusiastic readership, but that is not what motivates me.

My two novels since Josephine—Mistress of the Sun and The Shadow Queen—are not about marquee historical characters, and their stories, although compelling, don’t have the epic arc of Josephine’s life, and hence have not enjoyed broad popular appeal. If commercial success was what motivated me, I would have to seek out only marquee subjects. (Unfortunately, this is more important for writers of historical fiction now than in the past.) I very much enjoy having a wide and enthusiastic readership, but that is not what motivates me.

A reading, you’ve said, is more like a talk, an opportunity for the author to engage with the audience. What five pieces of advice would you give authors about to deliver their first reading/talk?

Most writers are introverts and find public speaking daunting. Take heart! Introverts are, as a rule, excellent public speakers, but only because they prepare like crazy.

Here is my process:

WRITE. Put a lot of time into writing a good talk. Write out every word of your presentation. Aim for only about five to ten minutes of reading, and the rest of it talk, leaving time for about fifteen minutes of Q&A at the end. Type the sections of your book you plan to read into your speech.

In general, people love to laugh, and self-deprecating humor goes over well. Remember that you are there to entertain. Readers enjoy personal accounts about the process of creation.

People like to be participants, so ask questions: engage the audience.

Prepare a few funny questions to suggest at the end, should your audience be shy to speak up during the Q&A.

Your entire talk/reading should be about thirty to forty minutes.

EDIT. Read your talk out loud slowly. Edit the passages you are going to read from your book to make them easy for you to read, as well as easy for listeners to understand. Change words you find difficult to pronounce or stumble over. Think of this as theater. A passage read out loud comes across differently from a passage one reads to oneself silently, so adjustments must be made.

PREPARE. Convert your talk to large bold print, and break each paragraph into sentences. Print out your talk and assemble it in a binder. Dog-ear each page so that the pages are easy to turn.

If the group is going to be at all large, ask to have a mic. This allows you more emotional range in your reading.

REHEARSE. A natural, relaxed presentation is achieved with lots of preparation. A few days before your talk, read in front of a mirror, sweeping up from the page with each sentence to meet your own eyes. The day of the talk, do this two or three times. Slow down as you read—don’t race through it.

Try on what you’re planning to wear—is it comfortable? Flattering?

PRESENT. Getting comfortable with public speaking comes with practice.

When I was first published, I read and was greatly helped by Never be Nervous Again, by Dorothy Sarnoff, who advises speakers to think of the following mantra before a talk: “I’m glad I’m here, I’m glad you’re here, and I know what I know.” Try it!

Plan what you will do in case only one or two people show up. Consider this your rite of passage: every author goes through it.

In the 1970s you were a book editor for a Toronto-based publisher, and now you’re on the author side of things. How would you characterize the publishing industry then vs. now?

Now most everything is done on computer, of course. Every time I publish a book I need to learn new vocabulary and procedures.

The biggest difference is that today your entire career depends on the sale of your most recent book, which can now be tracked. The big-box bookstores, which control the industry by virtue of their size, will place an order in line with the sales of your last book. Period. This means that authors and publishers don’t dare take risks, and that there is ever more pressure to write for sales. It also means that publishers are not likely to invest in an author’s career over time. A well-published mid-list author may have to change his or her name in order to be published as a debut novelist if his or her last book had disappointing sales. This is scary stuff!

And then, of course, there is the phenomenal rise of ebooks and online venues, principally Amazon. This has had a negative effect on brick-and-mortar bookstores, especially the independent bookstores. (I would very much like to see the model adopted in Germany and France, where independent bookstores thrive because discounting is against the law.)

All this is sad and doesn’t bode well for a healthy literary environment.

There is an upside, however: it is now also possible to respectably self-publish.

How often do you think about whether, or how well, your books are selling, or whether your next book will succeed or flop? Or is there a point at which such concerns fade and you’re able to go from one project to the next with a healthy amount of confidence?

I am long past retirement age, and I fortunately don’t depend on book sales to pay the rent, but by the same token I don’t want my “team”—my agent, editors, and publishers—to lose money. They have invested in me, after all. Before I even begin a novel, I chat about it with my agent and editors. Some subjects have failed to get a green light. These I may pursue in the future, for my own sake—and self-publish, if need be.

Once I begin, I feel the weight of trying to get the WIP to work as a novel, but I don’t think about whether or not it will succeed commercially. This has never been a concern while writing. Instead, I’m focused on the page.

That said, once my novel is finished to my liking (and this takes years), I’m very concerned about whether or not my agent and editors like it, and then—my biggest hurdle—whether or not my beta readers give it a thumbs-up. Once I’ve satisfied all these gatekeepers, I feel that I can safely assume a modicum of commercial success.

What is your writer to agented-writer story? How long did it take you to find an agent, what was the querying process like for you (How many queries sent? How many times did you revise and send different versions of the same query? Did you have an easy time or a hard time writing queries?), and what do you think resulted in that first contract: was it a perfected query letter, the right manuscript, or coming across the right person?

I’ve always thought that I was simply lucky in getting an agent because I was quickly taken on by someone who was new to the profession and needed to build up a list.

Looking back, however, I realize that I was more persevering than lucky. I’d been pestering this particular agency with a proposal every year. Publishing is in my bones, and I was determined to be published come hell or high water! (Fortunately, these early proposals were rejected.)

Ultimately, for me, it was the right manuscript plus the right person at the right time.

Napoleon, when interviewing generals, would ask, “Are you lucky?” He believed that you created your luck, and I think there is some truth in this. Perseverance is key.

Thank you, Sandra.

August 25, 2015

Beware of One-Size-Fits-All Advice for Social Media

Have you ever been in the following situations?

At a writing conference, someone asks, “Should I be tweeting?”

You attend a writing class where someone suggests Instagram is where all the young people are, thus authors should be using it.

On a message board, a new writer asks, “Should I start a Facebook author page?”

In response to such questions, you’ll often find a lot of conflicting advice. Over at Writer Unboxed, here’s my post explaining why there’s so much disagreement on social media use.

August 24, 2015

How Outlining Can Bring Out Voice

by KayVee.INC | via Flickr

Today’s guest post, from editor Gabriela Lessa (@gabilessa), explains how to use outlining to generate a strong voice for your characters.

“I got some rejections where the agents said they liked the premise but it lacked voice. How do I fix voice?”

As a freelance editor, I hear this question a lot from my clients. It’s something that seems to baffle authors. What exactly is voice? How do you see if your character has a voice? How do you fix it?

The whole “it’s a subjective business” thing can be frustrating to hear, and voice might seem like the most subjective issue of all. It probably is. But when you’re completely lost, even if you’re not exactly a plotter, outlining helps a lot.

How can something as mechanical as outlining help with something as subjective as voice? By allowing you to really get to know your characters. Most of the time, lack of voice comes from not knowing your characters well enough. If you, the creator, don’t know these people you’re creating, it’s unlikely your reader will really want to know them. Voice comes from consistency (even if that means being completely inconsistent, if that’s your character’s main trait). Voice comes from personality. It’s not enough to throw in a few punch lines and call your character sarcastic, or to add a few current slang words and think you have a teenager. Voice comes from dialogue, internal thinking, and, most of all, reactions. Voice affects your plot. Only when you have a complete, believable person will you have a character with a voice. That’s where outlining comes in handy.

Before you begin, it’s important to know that not everything that goes into your character outline goes into your novel. If you outline well, less than half of the information will make it into the manuscript. But you need it anyway. Every detail counts when building your complex, three-dimensional people.

But where do you begin? How do you create people from scratch?

Begin with the big stuff. Fill in the gaps later.

1. Character Arc

You’ve probably heard about this one. You’ve probably seen some sort of graph about it (which can be very helpful, by the way). There are several approaches to this, and you can pick the one you feel comfortable with. Regardless of the chosen method, it all comes down to asking the big, important questions that will affect your plot.

Who are your main characters when the story begins?

Who will they be when it ends?

What is keeping them from getting to that ending (both internal and external obstacles)?

What are their fundamental flaws?

These are questions that must be answered for your story to make sense. So write it all down. To sum it up in one question: What do you need to know about your characters in order to have a plot that makes sense? That’s the first thing you should outline.

2. Main Traits

This is where your characters stop being just pawns in your plot and begin their transition to believable people.

Start with the basics, like physical description. You certainly do not need a big chunk of physical description in your manuscript (please don’t do that). But you need to know every detail about these people. Some won’t make a difference. But some will. Being a short, skinny boy in an adventure is not the same as being a big, strong boy. A story about a woman who is considered the most gorgeous lady in town when she’s a size 14 and has wild hair is a completely different story than that of a size 6 platinum blonde. So write down the physical stuff and see if it matches the character arc. Would such a small boy have the strength to beat a monster? Would a woman like this have a low self-esteem? Make sure it’s coherent.

Once you match your characters’ physical traits to their arcs, it’s time to map out their main psychological traits. What would be the main characteristics you’d notice about these people? What kind of qualities would they need to have to match the arc you built for them? Consider what would really stand out about their personalities. Ask yourself how people like these would react to each main event you have planned for them. Would they care about the inciting incident you planned? Would the crisis you imagined really be a crisis for people with these personalities?

Finally, it’s time to write down your characters’ back stories. Where did they grow up? How were their families? Do they have jobs? How did they get to this point? This is the moment to look back at everything that brought your characters to the inciting incident. Their history should help you understand how they got to this point.

Once you’ve done this, you should have people that make sense. Their history should match their personality. When you finish step two, you should be able to identify cause and consequence in everything your characters are and in everything they do throughout your plot. This is the time to think about reactions. Everything that affects the way your characters react to a big event goes here.

3. Details

This is the fill-in-the-gaps part. This is the part that makes your characters really unique.

You should know anything that you would know about your family and closest friends. Birthdays (and whether they like to celebrate them), likes and dislikes, favorite foods, favorite drinks. It might seem unimportant now. But wouldn’t it be weird to read a story that unravels through the course of two years, with a main character who loves parties and celebrations, and never see a birthday party? These details make characters believable.

And finally, a very important question to ask: Do your characters have any quirks and habits? Hair-twirling, nail-biting, lip-chewing—all of that counts. This is the stuff that will make your beats. Many authors hear they should use beats instead of dialogue tags to show more, so they dump random actions in the middle of dialogue in the hopes of showing. It’s true, beats do help show and they do bring out voice. But only when done right. Beats have to in fact show something worth showing. If you have a very confident alpha man, it’s unlikely he’ll be scratching his head or looking down at his feet when talking to a woman. If your heroine is known for being completely relaxed, it doesn’t make sense for her to bite her nails and chew her lips all the time. Beats are not there just to fill in for dialogue tags. They’re a great way to build voice. And you can only build voice when beats bring out your characters. When reactions show personality, you have voice.

This might seem like a lot of work for details that won’t even be in the manuscript. But the good news is there’s no rule for how you go about this. You can create spreadsheets. You can write it all down on Post-its and fill your wall with them. You can have one long Word document where you write it all down. And most importantly, this is flexible. You can go back and forth. You can add details as you get to know your characters. As long as you have it all written down, you can always go back and see if the details match the main traits, and if the main traits match the character arc. As long as they complement each other, you will have strong, three-dimensional characters your readers can see as real people. After all, loving and hating these fictional people is the best part of reading!

August 20, 2015

How to Sell Digital Products & Services Directly from Your Website: Advice for Authors and Freelancers

I’ve been building and refining my website (JaneFriedman.com) for nearly a decade, gradually increasing its customizations and complexity. I started with a social streaming splash page, later moved to WordPress, added free WordPress plugins to extend the site’s functionality, and used bare-bones hosting through GoDaddy.

My setup today is more complex. This past month, I bought an SSL certificate for the site and integrated Stripe payments. I’m also on a more expensive hosting package.

Website tools and resources have came a long way since this site first went live. While I still advocate for an incremental approach to site building—don’t make things complicated unless they need to be—it’s also easier to have a fairly sophisticated site without spending a fortune (or having deep experience in site building).

For me, one of the biggest complexities was integrating e-commerce functionality—the ability for someone to purchase directly from my site without leaving it (e.g., clicking a button and ending up at PayPal). But it wasn’t as complex as I was expecting.

If you want to sell products and services directly through your website, here’s how to do it quickly and without hiring outside help. Those of you with a self-hosted WordPress site can probably start selling direct through your site within 24 to 48 hours—without knowing code. However, I know this may still be complicated for anyone without a digital media background, so at the end of this post I’ll mention a couple of alternatives.

1. Make it easier on yourself: get good hosting.

You can’t use a free WordPress.com site if you want to use many of the tools I’m about to suggest. That means you need to self-host your site. If you’re not sure what that means, read my post on how to self-host your site, which includes a tutorial on how to set up a self-hosted site in ten minutes.

While you can get cheap WordPress hosting (less than $100/year), if you don’t have much experience with running your own site, you might be better off with managed hosting. Even I’ve chosen managed hosting for a range of reasons.

This site runs on Media Temple Managed WordPress Hosting. I’m on a legacy plan that’s no longer available, but it allows me to host up to three different sites. Media Temple’s WordPress hosting offers several qualities that I find indispensable.

Quick staging areas: If you want to set up a test site, redesign your site, or do anything that shouldn’t be immediately live, Media Temple makes it easy to set up a WordPress staging area in one click.

Automated backups: Your site is automatically backed up daily. If something goes wrong at any time, you can immediately restore your site using the backup. Again—one click.

Easy SSL certification: SSL certification is a necessity if you plan to sell directly from your site, so that visitors’ private information is protected and transmitted securely. (When you’re visiting a site, look to see whether the URL begins with http:// or https://. That s in https:// indicates you’re on a secure site.) I was able to buy and add an SSL certificate to my site within 24 hours. I wasn’t required to do anything technical; MediaTemple automatically installed it.

Find out more about Media Temple Managed WordPress Hosting. (Disclosure: I’m an affiliate with Media Temple and have been a happy customer since 2011.)

2. Get a customizable WordPress theme.

I’ve recommended free WordPress themes f0r writers here, but once you get serious about customization of your site, you’ll likely end up buying a premium theme—unless you know how to code your own WordPress theme. (And I don’t!)

Some of the more powerful WordPress themes allow you to build customized column- or row-based layouts for each page, with integrated buttons, icons, and widgets. I like and use the premium version of Vantage (a SiteOrigin theme that uses Page Builder). But there are other similar options, such as Make from Theme Foundry and Headway.

More flexible layouts tend to be essential once you build landing pages for courses, products, or books. You can see my books page here, and an example course page here.

3. Integrate e-commerce functionality (payment forms and processors).

Once your site has an SSL certificate (see your host’s FAQ for how to add one), the tricky part is integrating a store or payment form, shopping cart, and/or payment processor to facilitate transactions or purchases directly from your site.

If you’re selling courses or services that don’t require delivery of a digital product, then a quick way to get started is to buy the premium WordPress plug-in Gravity Forms. Gravity Forms is considered one of the top WordPress plug-ins of all time for being easy to use, intuitive, customizable, and powerful. When you add Stripe (a payment processor) into the mix, then essentially you’ve just given yourself a way to build a checkout form—with a payment method—that your customers can use to complete a purchase. (If you don’t want to use Stripe, Gravity Forms integrates with other payment processors as well.)

If you need to deliver digital files or products immediately or automatically upon purchase—this is often the case with ebooks and other informational products—you can layer on Easy Digital Downloads (another WordPress plug-in). It’s free to use initially, but for increased functionality, you’ll end up paying a one-time fee.

4. Or start more quickly with alternatives to full integration.

If you don’t want to mess with the suggested solutions in item 3, take a look at these alternate shopping carts or product-payment facilitators:

Gumroad — I’ve used this, and it works fine. It’s just doesn’t look streamlined with my site because I can’t adequately customize the design.

PayHip — Specializes in ebooks.

MoonClerk — Highly recommended by others in online marketing.

Using these services often means the payment or transaction is not happening on your site, although you can get pretty close to making it look like it does! None of these services requires you to have an SSL certificate unless you’re embedding its form/tech on your site. But these solutions will eat into your revenue a bit, since you’re adding a middleman into the mix—you’ll pay either a monthly fee or a revenue percentage.

There’s also the old standby, PayPal. You can just embed a PayPal button that says “Buy Now,” and your customers will be directed off your site to pay. (This is what I’ve been doing for the past year.)

How to sell subscription-based products

I’ve been experimenting with Chargebee, which is a powerful accounting and administrative tool if you plan to sell any type of product that has a recurring fee (monthly, annual, or something else)—but it’s only for fairly serious businesspeople, since the minimum monthly fee is $49/month. MoonClerk can also handle recurring payments and has lower-cost plans.

When you want to charge later, not up front (invoicing)

I use Wave (free!) to invoice clients for services rendered. A good portion of my income is from services that I bill for after the work is completed, so it’s important for me to have a robust online invoicing system that keeps track of who has paid and who hasn’t, with automatic direct deposit to my banking account. Wave has payment processing built in and allows customers to pay immediately with a credit card. On your invoices, you can also include information about paying through PayPal if your customers prefer that method–you can even include instructions on payment by check. (Wave’s invoicing system is highly customizable.)

Shortcuts that don’t involve WordPress self-hosting

If all this seems more daunting than empowering, here are two very easy options:

Use Squarespace. You’ll pay a monthly fee, but it’s a managed hosting environment and integrates e-commerce functionality.

Use Rainmaker. This is a more high-powered option (and more expensive), but it’s a ready-to-go WordPress-based system that has been engineered for e-commerce—including product sales, subscription services, and online education.

What about selling print books?

If you want to sell print books directly off your site, reconsider your strategy. I recommend doing so entirely through online retailers such as Amazon, which have finely tuned order, shipping, and fulfillment systems that work in your favor as well as theirs! For my time and energy, the hassle of selling print books isn’t worth the extra profit. However, if this is something you’ve done successfully, please comment on this post or get in touch directly to share your experience.

What tools have you used to facilitate purchases from your website? Share in the comments.

August 18, 2015

How to Find an Editor as a Self-Published Author

by suzumi3 | via Flickr

In today’s guest post, indie author Teymour Shahabi explains how to find an editor for the draft of your self-published book and what to look for in an editing relationship.

In traditional publishing, submitting your draft to an editor is an inevitable step on the road to bookstore shelves. But how much editing is required for self-publishing? Does a self-published author need to find an editor? And if yes, when and where, and how?

First things first:

Do you need an editor?

The answer is yes.

The greatest benefit of an editor is that he or she is not the author. An editor is someone else. Some editors are professional writers, but every single one of them is a professional reader. As a writer, you’re probably a voracious reader, but you can never be a true reader for your book. By bringing forth a book into the world, you’re asking other people to read something you’ve never read. If you sincerely want the book to be the very best that it can be, then you must ask someone else to read it first. You owe it to your book, to yourself, and to your readers.

What an editor does is discover your characters, your situations, and your images without seeing any of the creative process that brought them to life. Where you might see all the crossings-out and labors, all the accidents and decisions, the editor sees only a page. This is the clarity you need, and you can never achieve it for your own writing, simply because you envisioned it first. The editor will tell you what an attentive, an educated, and, most importantly, a new reader will experience while reading your book.

When should you hand your manuscript over?

It’s difficult to answer this question without first addressing what an editor actually does. Editors can review the content of your writing (characterization, pacing, plot, etc.), which is often referred to as content editing; the form of your writing (the grammar, the punctuation, etc.), which is often referred to as copyediting; or both. (By the way, proofreading is indispensable, but it’s the final step of checking for typos and other glitches once the book is ready for print—any writer who thinks that proofreading is editing is in grave danger of getting ripped off.)

So when should you look for an editor? Logic indicates that content editing should come before copyediting, though what exactly you need might depend on the book. But in every situation, you need to hand over your manuscript at the point where there’s no improvement left for you to make on your own.

In other words, you should edit, tweak, and refine until you reach the point where the next change no longer enhances your book. Most likely, you’ll know the point when you reach it (you’ll start to feel that you’re running on a treadmill, as opposed to covering new ground).

But it might be helpful to ask non-professional readers (or “beta readers”) to take a look at your draft before turning to an editor. To use a painting analogy: paint as many coats as you have to before applying the varnish. (You could always paint over the varnish, but wouldn’t that be a waste?)

How do you find an editor?

There are about as many ways to find an editor in today’s world as there are to find love. Instead of casting a wide net through search engines and outsourcing databases, it’s usually better to focus your efforts by targeting specific communities, such as the Editorial Freelancers Association.

Just as in dating, a seal of approval from someone trustworthy is ideal: you can ask for recommendations in places where authors get together (such as WritersCafe.org). One useful list is available here at JaneFriedman.com; Joanna Penn also has a list.

Don’t just reach out to one editor; contact several. When choosing the right person for the job, there are at least three considerations you should keep in mind: book, business, and (bedside) manner.

1. Book

The single most decisive factor should be the quality of the edit itself: Will this editor help improve your book? In order to assess this, nothing beats a sample edit (even if you have to pay for it). Testimonials and credentials (such as experience at a major NY publisher) can help you narrow your list, but you should submit the same sample to a variety of editors and compare their work side by side. Some editors will push too hard, and some won’t push hard enough; some will simply “get” your writing, while others will seem to speak another language entirely. In my experience, the editor’s résumé is far less revealing than the quality of the sample edit. In fact, the higher an editor’s pedigree, the more reluctant the editor might be to provide a sample edit. Don’t be afraid to insist: no one should expect you to invest in a car without a test drive!

2. Business

An edit is a business transaction. This means that money will exchange hands. Therefore, you need to approach the edit as both a writer and a businessperson (an increasingly common role in the age of self-publishing). Compare the deals you’re offered. Editors with brand-name backgrounds might offer less user-friendly terms (such as hourly rates, which are less predictable than fixed contracts), while less established professionals might offer discounts and extras (such as book formatting and publishing consulting). Don’t be afraid to ask. Hiring an editor is a professional investment. A sample edit will allow you to estimate the value of the service, but never forget about the price.

3. (Bedside) Manner

Technology may have changed the way books are produced and distributed, but ultimately the connection between reader and writer is one of the most enduringly personal in history. You need to pay close attention to an editor’s manner and decide if the relationship is likely to be pleasant, professional, and productive. Is the editor overly curt or slow to respond to your emails? If the comments in the sample edit are too harsh, how will you make it through hundreds of pages of red-inked barbs? Beyond the financial expense, editing can be an intensely emotional journey; make sure that your editor will be a good travel companion.

No matter how much the industry changes, authors will always need editors. But always remember that an editor is more like a therapist, rather than a surgeon. The editor doesn’t hold the scalpel, and you’re not lying helpless: as soon as you step out of the edit, the book’s life is entirely in your hands.

For more on editors:

5 Ways to Find the Right Freelance Editor by Stacy Ennis

What Is a Developmental Editor and What Can You Expect? by Katherine Pickett

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers