Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 148

June 2, 2015

How to Repurpose Your Book or Blog Content for Profit and Promotion

by nikname | via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is adapted from How to Blog a Book: Write, Publish, and Promote Your Work One Post at a Time, by Nina Amir (@NinaAmir), published by Writer’s Digest Books.

Here’s a bit of information the book industry doesn’t like to reveal: Books don’t provide a huge source of income. In fact, most authors, with the exception of those who consistently hit the bestseller lists, supplement their book royalties with additional sources of income that may or may not be related to their publishing efforts.

As an author who has just produced or may be in the process of producing amazing amounts of content, you have a great advantage: You can turn all that content into money-making products. These “information products” can provide you additional income and a business that revolves around your book. This strategy also works for long-time bloggers who are often sitting on as much information as a book would contain.

What Are “Information Products”?

Information products provide consumers with the information they need or want, solve problems, offer expert advice, educate, or in some way provide a service, tip, or tool.

Whether you have a book or a blog, you have a treasure trove of content. You can repurpose the content into special reports, videos, recordings (MP3s, CDs, or DVDs), e-books, workbooks, teleseminars, webinars, home-study courses, or online courses. You also can create related services, such as coaching and consulting.

Types of Information Products

What types of information products might you create? Here’s a quick list.

1. Tip Sheets or Booklets

Do you offer a lot of tips on your blog or in your book? Pull these into a tip sheet that consists solely of beneficial advice in little snippets. Include twenty tips on a page, and convert it into a PDF. Or compile thirty days’ worth of tips or one hundred tips and turn this into a short book or booklet. If you have a bit more to say, consider producing a tip booklet that offers one tip per page with a little bit of copy explaining the tip. You can publish them inexpensively as a PDF, an e-book, or a printed and saddle-stitched (stapled) booklet.

2. Special Reports

These are short, informative documents, usually under ten pages, on one highly focused topic. Often they are written for professionals. For example, I created one on how to build author platform; I used to give it away to those who signed up for my mailing list, but now I sell it for $10. I created it out of several blog posts I edited together, along with a little extra copy to flesh it out. Create a cover, and you’re in business. (Explore services like Canva for free or inexpensive ways to create cover art.)

For special reports, consider what your readers want or need to know. What problem can you solve for them? What could you tell them in a few short pages? Maybe something interesting, new, or newsworthy has happened that relates to your book or blog; this could be additional content used for a special report.

3. Audio and Video Recordings

You can create educational videos or audio recordings and sell them. I highly recommend you videotape or record almost everything you do—teleseminars, webinars, workshops, Google Hangouts on Air, speeches, and radio interviews. You then can sell them or use them as information products.

Creating audio recordings is simple: Purchase a decent digital recorder, and record yourself reading blog posts, talking about your book, or telling people how to do different things related to the topic of your blog or book. You can also record on your computer or smartphone (but purchase a good mic). Aside from selling the recordings (in CD or digital form), you also can upload some as blog posts so people can listen to them, and upsell readers on additional audio recordings are available for sale.

Easy audio-editing software is available for free, such as Audacity. If you are working with video, you can start with Moviemaker or iMovie, or try Camtasia.

4. Self-Study Courses and Online Education

If your book lends itself to teaching, demonstrations, or classes, combine your written material with your audio and video to create self-study or online courses. Workbooks are also popular, either as stand-alone instruction or as part of teleseminars, workshops, or coaching. People are willing to pay more money for online education than for books.

5. Coaching and Consulting

If your book or blog teaches people how to do something, or if it focuses on some sort of system for accomplishing a task or goal, consider providing coaching and consulting services. (By the way, if you want to do this, get a book out right away. Nothing will give you more credibility as an expert than becoming a book author.)

6. Short Books

Short books are increasingly your ticket to branding, expert status, platform, customers and clients, and cash. We’re not talking a magnum opus—you can produce 4,000- to 20,000-word e-books for Kindle. Just as you plan out a longer book (or a series of blog posts), do the same for your short books. You can also repurpose a blog post series into a short book.

I did this with my book 10 Days and 10 Ways to Return to Your Best Self: A T’shuvah Tool Bridging Religious Traditions. I took ten blog posts I’d written as a series, added an introduction and conclusion, edited the copy, and then tacked on some promotional material for my other short books at the end. When done, I had a 72-page book I printed on a short-run digital press and then at CreateSpace as well.

Think about how easy it becomes to produce books from blogged content if you plan those posts as a series you know you will turn into a book.

7. Membership Sites and Continuity Programs

If you’ve ever purchased a course and needed login credentials to access it, that information product likely was hosted on a membership site. If you’ve joined a membership site, such as Michael Hyatt’s Platform University, all the information, including the forum, is provided via a membership site.

If you decide to create a variety of courses or to produce a continuity program such as a “university,” an association, or an organization that requires yearly or monthly payment to become a member, you need a membership site plugin. A variety of them exist, such as Wishlist, MemberPress, MemberMouse, and Magic Members, to name just a few. These plugins provide you with password-protected pages and landing pages that allow you to place all your content—videos, audio recordings, workbooks, reports, forums, etc.—in a secure place that only those who pay can access.

8. Giveaways

Any of the aforementioned informational products can become giveaways to help you build your mailing list. Or you can simply excerpt material from your blogged book as a free enticement to sign up. It’s best if you package it as something new and interesting, or add a video or audio element.

The Technical Aspect

You of course need a mechanism for selling your information products. You can create a page on your website with a shopping cart system so readers or visitors can purchase these items any time, day or night, by downloading them. You may want to sign up for a service like 1ShoppingCart.com so an auto-responder sends the purchased items immediately, or simply use PayPal and send them out manually. You also can use E-junkie or ClickBank. These services deliver digital downloads. Like PayPal, they provide a code you place on your site that creates “buy buttons,” and the rest is handled via their services.

Marketing and Promoting Your Information Products

No matter what type of products and services you choose to produce, be sure you promote them well. Most membership plugins offer templates or ways to create sales pages, or splash pages. You might want to invest in something like LeadPages, which offers professional templates.

Just as you launch a book, you launch your products and services for the best results. To learn more about this, read Jeff Walker’s Launch and generally educate yourself on how to succeed as an online marketer.

Just as you launch a book, you launch your products and services for the best results. To learn more about this, read Jeff Walker’s Launch and generally educate yourself on how to succeed as an online marketer.

All the products mentioned here—and many others that I have not mentioned—work for you night and day, 24/7, if you set up an effective storefront. It’s a way to leverage your knowledge.

To find out more about writing, publishing and promoting your work online, check out How to Blog a Book: Write, Publish, and Promote Your Work One Post at a Time, by Nina Amir.

June 1, 2015

The Yearning to Learn From Our Lives

photo by Sigrid Estrada

Some of you may recall the controversial essay published in February about an MFA instructor who left teaching, then felt free to say what he really thought of his students. It is full of half-truths and a few moments of insight, but those moments of insight don’t really make up for the rest of it. (God help the new or inexperienced writer who tries to differentiate the half-truths from the insight.)

Contrast that piece with this wonderful meditation by Lisa Gornick, “An Analyst Teaches the Personal Essay,” in the latest bulletin from Glimmer Train. Gornick was asked to teach a personal essay course because of her background as a psychoanalyst. She says:

We all yearn to learn from our lives so we do not stumble like Sisyphus up the same hill over and over but, instead, discover the art of living well. For those interested in the therapy situation or the personal essay as a means to this end, there are pages to be borrowed from one another. The personal essay can provide an artful account of earned insight often more useful than tomes of session transcripts or the bastardized synopses of years of therapeutic work. Conversely, for the writer, the therapy situation can provide a road map for the diversions into defensiveness and self-deception, the way we fight self-knowledge as we seek it.

Read the full essay by Lisa Gornick.

For more from Glimmer Train:

The Fire and the Snow by Jennifer Tseng

The Writometer by Clare Thompson-Ostrander

May 29, 2015

The Age-Old Cynicism Surrounding the Dream of Book Writing

I’ve known about this joke for nearly as long as I’ve worked in book publishing. It goes like this: “More than 80% of people say they have a book inside them. And that’s exactly where it should stay.”

While speaking and tweeting at the International Digital Publishing Forum at BEA this week, I had the opportunity to hear Jane McGonigal speak. (She’s well-known for this TED talk.) She shared this statistic:

More than 90% of young people in the United States say they want to write a book someday.

I tweeted the stat, and while there were some people who considered that inspiring, the more common response looked like this:

That’d be inspiring if more wanted to learn basic grammar and improve their reading skills.

But do they want to READ one?

Jane McGonigal saw the responses later and said:

oh my gosh your followers are very cynical about young people wanting to write books! Wow! (Reading their replies)

Unfortunately, every generation is quite the same in this regard, which is nicely expressed in the following 1900s quotation: “The world is coming to an end. Children no longer obey their parents and every man wants to write a book.” (A Twitter response reminded me of it.) This type of complaint dates back to when the printing press was invented, when many warned that the bad books outnumbered the good.

McGonigal’s talk was meant to inspire publishers to think more imaginatively about how to engage young people in reading—by making the experience match the positive emotions that come from gaming (such as creativity, curiosity, awe and wonder, excitement, surprise, and joy, among others). She emphasized that younger people aren’t interested in passive consumption—they want to engage, respond, create. And this message fits what you’ll hear if you talk to the folks at Wattpad, where 40 million people (predominantly young adults) go to read and write.

I’ve had more than one conversation with adult writers who just don’t understand why anyone would take Wattpad seriously.

But it’s a mistake not to take it seriously. (If you’ve never heard of Wattpad, I encourage you to watch this video to begin to understand it.) It’s where young people are learning to write, in front of a “live” audience if you will, and going on to publish with traditional houses.

Why do we feel the need to place value judgments on how young people read or write? Dare I ask why we believe someone must become a serious reader before it’s okay for them to begin creating/writing? How much reading should be required before you get the green light to write? Doesn’t writing make you a better reader? (I must say at this point that I have never formally studied these issues; if there are educators who can comment intelligently on this, please do.)

What I observe in the reaction:

There’s an overabundance of books and it’s just as upsetting now as it was in the 1400s. With digital publishing tools, even if you can’t get a publisher, the manuscript doesn’t have to collect dust under the bed. You can publish it. And as Clay Shirky has said, the question today isn’t “Why publish this?” It’s “Why not?”

We think young people are not as smart, hard working, or [fill in the blank]. Every generation thinks the one after it is somehow deficient. Today’s young people are especially under this burden, as they’re constantly referred to or identified by the fact they grew up with the Internet, or digital devices, which tend to take the blame for the many evils in the world. We’re all fretting about whether or not we’re slowing down enough to read a book—even though we’re likely reading more than ever, just in different formats and mediums.

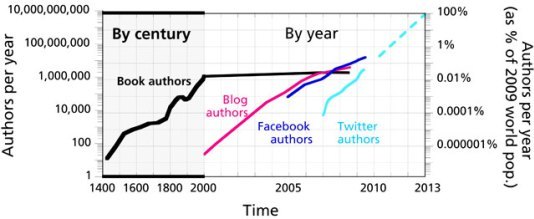

We are potentially entering a new era—what has been called the Era of Universal Authorship (see graph below). And one of the tweeted responses did in fact acknowledge this subtext: “That [statistic] is a bit depressing. Not just the competition. That takes away from the notion of writer as identity.”

Exactly. If everyone is a writer, then what makes any particular writer special?

That’s a pretty damn scary thought for the “serious” writers out there—who can also be the ones who cringe at the masses who wish to write or ridicule them for their attempts. If everyone is a writer, and no one is a reader, then who will read us? Who will care about our special snowflake work? Who will put us on a pedestal if everyone else is writing? And won’t the good work get crowded out?

Our culture used to have the same qualms about the spread of literacy. There were elitist objections that books would be misread by unworthy and ignorant readers. We somehow progressed in our thinking, so much so that we’re now erring in the opposite direction. (You can hardly go a week without seeing claims of how important fiction or novel reading is because it increases empathy or some other social good. It’s a tiresome argument that smacks of desperation, but that’s another post for another day.)

In any event: Trying to stop the era of universal authorship is pointless. We’re not going back to a time where we all passively consume media again. Writers who want to be visible or differentiate themselves in the market will have to:

Have an authentic and engaging connection with their readership (and before even that, of course, they’ll have to find out who their readers are or where they are!)

Think beyond the book artifact when it comes to what they create

Of course, those two things have been the topic of my blog for a very long time now.

May 28, 2015

What Marketing Support Looks Like at a Big 5 Publisher

by Mace Ojala | via Flickr

Today’s guest post is by author Todd Moss (@toddjmoss).

One of the unexpected surprises of being a new author is how much goes into promoting your books. I was lucky to be published by Penguin’s Putnam imprint for my debut novel, The Golden Hour. Yet even with the backing of a hefty Big Five publisher, I discovered that delivering the manuscript is just the beginning.

One of the unexpected surprises of being a new author is how much goes into promoting your books. I was lucky to be published by Penguin’s Putnam imprint for my debut novel, The Golden Hour. Yet even with the backing of a hefty Big Five publisher, I discovered that delivering the manuscript is just the beginning.

In 2013, Putnam offered me a generous multi-book contract for a thriller series about Judd Ryker, a crisis manager in the State Department inspired in part by my experiences working inside the U.S. Government. In the first installment, Ryker is sent to the West African nation of Mali to try to rescue an American ally who has been overthrown in a coup d’état.

During the sixteen (long!) months between signing the contract and the actual release of the first book in September 2014, Penguin provided an enthusiastic marketing team and two professional publicists. I couldn’t have asked for more support from Putnam, and I’m exceedingly grateful for all they did to help propel The Golden Hour to the Washington Post bestseller list.

The book’s success helped turn a fun, mostly weekend project into a second career. I still love my day job running a Washington DC think tank, so I tightly plan my schedule to allow me to do both. Yet, even with Penguin’s mighty PR machine, there’s still plenty the author is expected to do to create visibility and connect with readers.

Social Media

Putnam helps me by crafting graphics and giving advice when I ask, but I built and manage my own website, created a Facebook author page, and was already fairly active on Twitter. I’m on Twitter nearly every day in short bursts and try to post on Facebook about once per week. I’m taking the long view on social media, as I’m not yet convinced the hours I spend on it greatly impact sales, but I find it energizing to engage directly with fans and other writers. I also created an email database of some five hundred friends and colleagues who want to know the latest and support my writing life. I’m still trying to figure out the right frequency for communicating with this list (how to keep friends in the loop without annoying them), so for now I’m hitting them only once or twice per year.

Print, Radio, and TV

Putnam’s publicists created a press kit and helped me to place articles in USA Today, the Daily Beast, and on NPR’s Goats and Soda. They booked me on MSNBC’s The Cycle and the Diane Rehm Show on NPR, and arranged nearly fifty (!) back-to-back radio interviews over two days. This was tremendous. Yet I’m still tapping my own networks to get in the newspapers or on radio and TV, especially outside of the immediate weeks surrounding a launch.

Public Appearances

I’d heard that traditional book tours are becoming a thing of the past, so I wasn’t expecting much. Still, Putnam arranged a book launch at Politics & Prose (a humbling rite of passage for any Washington DC author) and a brief but exhilarating tour to bookshops in Phoenix and Houston. Turnout at each was mostly friends (and friends of friends!) since, by definition, no one knows debut authors. I hope turnout will grow over time as my fan base expands. With encouragement from the publisher, I also organized a further seventeen public appearances at schools and professional organizations, plus several private events with book clubs, arranged by friends.

over time as my fan base expands. With encouragement from the publisher, I also organized a further seventeen public appearances at schools and professional organizations, plus several private events with book clubs, arranged by friends.

I recently delivered the third manuscript in the series and am starting on the outline for the fourth. But mostly I’m now gearing up to promote book two, Minute Zero, for its release September 15. This time, Ryker is headed to Zimbabwe, where an aging dictator is trying to cling to power through force and fraud. Again, Putnam is doing the heavy lifting on marketing and publicity. But this time around, I’m more prepared to do my part, since I’ve realized that being an author is so much more than just writing books.

May 27, 2015

Is Self-Publishing a Viable Option for Literary Fiction Writers?

by editrrix / via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company. Don’t miss Sangeeta’s earlier contributions, including:

Self-Publishing Children’s Picture Books: Two Literary Agents Weigh In

Should Children’s Book Authors Self-Publish?

Even though it’s become quite easy for writers to use Amazon KDP or other platforms to publish an e-book—and use print-on-demand technology to create a professional-looking print book—it’s still rare for literary fiction writers to self-publish.

I asked literary agents Vicky Bijur and Ayesha Pande if and when literary writers should consider this option, how it might affect their long-term careers, and what digital trends we might see in terms of marketing literary fiction.

Sangeeta Mehta: Sales of self-published literary fiction are anemic compared to that of genre fiction, but is this a reflection of the industry as a whole—or because the success of literary writing depends on established, traditional systems that aren’t accessible to self-published writers?

Vicky Bijur: One theory: Genre fiction is read in digital form to a greater degree than literary fiction. That is, readers of genre fiction are used to reading e-books; literary fiction readers a bit less so. Also, there may be many more online blogs/websites, etc., devoted to genre fiction; it may be harder for a reader to find out about literary fiction that is available only digitally. Literary fiction is still review-driven; even though the traditional review media are shrinking, it is still really important to catch the attention of traditional critics, and I think it’s very hard for e-book originals to do that. As recently as 2008 or so a self-published author might still have been selling books to independent bookstores out of the trunk of her car. With the severe reduction in the number of independent bookstores, it much harder to get traction even if your book is in print form.

Ayesha Pande: My response here is based purely on anecdotal evidence: It seems readers of literary fiction have a bias for print books; many readers tell me they want to keep the books, put them on their shelves, read them again and share them with others—none of which is possible with an e-book. In addition, sales of literary fiction still do depend on reviews and self-published books don’t tend to be reviewed by book reviewers, mainly because there are simply too many of them.

Many literary writers embrace the idea of independent publishing, of signing with a small, independent press rather than a media conglomerate. What do you think is preventing these same writers from being as supportive of “indie” publishing? Is it the stigma it continues to face in some circles and writing programs? The onus of having to design and promote their own work in addition to honing their craft? Or the romantic notion that writing is an art, not a business?

AP: A combination of all of the above, but most particularly the understanding that writers are frequently not the best promoters of their own work. There is a skill set required to publish a book and effectively promote it, and most writers I know, who happen to write mostly literary fiction, simply don’t feel qualified to do that. In addition, they would rather spend their time and energy honing their craft rather than learning an entirely new one—publishing and promoting books.

VB: I think there is legitimate concern that if you self-publish you lose all the marketing push that traditional publishers can provide: co-op money for bookstore placement, advertising, early galley mailings to the stores, and so forth. Also, there is something to be said for having the blessing of the gatekeeper and the literary cachet that comes with that.

When considering debut literary writers for their list, most publishers are thinking less about short-term sales and more about the kind of awards and prestige these writers might bring the company down the road. It’s also far easier to market a debut author than one with a track record. By self-publishing, would debut literary writers compromise their most valuable asset: potential? Could self-publishing prevent these writers from landing residencies and being accepted into writing colonies, which are often more favorable to early-career writers?

VB: I can’t help with this question. I don’t know how these residencies look at self-publishing.

AP: I’m not sure I agree that publishers are not thinking about sales; they are running a business after all and ultimately they are anticipating that publishing the book will be profitable for them. Writers who have self-published their book and sold only modest numbers of copies will in all likelihood have a harder time persuading publishers that their books can produce viable sales as compared to debut authors who are starting with a clean slate. I can’t speak with authority about self-publishing being a deterrent to receiving residencies—but I would speculate that to qualify for those it’s the merit of the work that would be the foremost determining factor.

Many agents won’t consider representing a self-published work unless sales are in the high five- or six figures. However, very few works of literary fiction achieve such lofty sales, even with the marketing muscle of a large publisher. Do you have a sales number in mind when considering self-published works? Or would a positive review (from Kirkus or PW, both of which accept self-published books), or an award be more likely to sway you in one direction or the other?

AP: A writer having self-published their work, especially a first novel, wouldn’t necessarily deter me from considering her for representation. I would read the book and assess the merit of the work and make my decision based on that. Many excellent novels do not find publishers and there are many promising authors out there whose work deserves to be published and read. In fact I represent an author who successfully self-published his first two novels.

VB: When Lisa Genova approached me with Still Alice in 2008, which she had self-published, I didn’t care about how many copies she had sold. Here’s what I cared about: I couldn’t put down the book; my twenty-three year-old assistant couldn’t put down the book; I thought Lisa’s background as a neuroscientist with a Ph.D. from Harvard University provided her with an instant platform; she had the savvy and the sophistication to have hired a PR firm for her self-published book; she was writing about a topic that had a huge audience; she had already made deep connections within the Alzheimer’s community. That is, the book was spectacular, and it was clear the author was a superstar.

VB: When Lisa Genova approached me with Still Alice in 2008, which she had self-published, I didn’t care about how many copies she had sold. Here’s what I cared about: I couldn’t put down the book; my twenty-three year-old assistant couldn’t put down the book; I thought Lisa’s background as a neuroscientist with a Ph.D. from Harvard University provided her with an instant platform; she had the savvy and the sophistication to have hired a PR firm for her self-published book; she was writing about a topic that had a huge audience; she had already made deep connections within the Alzheimer’s community. That is, the book was spectacular, and it was clear the author was a superstar.

Would you recommend self-publishing to a mid-career client whose option clause has been satisfied by her current publisher—and whose new work isn’t garnering interest from other publishers—as a way of keeping her writing momentum going? Or, rather than publish on their own, is these writers’ time better spent submitting to well-known journals or to new online literary platforms such as Literary Hub or The Offing?

VB: It used to be that writers were discouraged from doing a “small book” in the middle of a career of bigger books, because the chain bookstores—the brick and mortar stores—kept close track of sales, and low sales would hurt the prospects for a writer’s future books. I am not sure that it matters any more if a mid-career book that is published only as an e-book does not do as well as the author’s traditionally published books. I know that often a writer has a book he or she feels must get written before he or she can move on.

AP: I would probably advise such an author against self-publishing in mid-career unless it’s truly the only remaining alternative. A good novel takes a very long time to write and I would ask the author to consider working on building her platform—via residencies, publications in journals, awards and fellowships—or on writing and rewriting—and rewriting—again.

According to The Guardian, literary criticism is still heavily male-dominated, and self-publishing is allowing women to break the book industry’s glass ceiling. If this is the case, shouldn’t more female literary writers take the leap and carve a new space for themselves in the indie landscape?

AP: I don’t think self-publishing is the way for women writers to respond to literary criticism being male dominated. I think we need more diversity in the ranks of literary critics and we need to pressure publications to provide us with a more diverse array of voices.

VB: I am not sure what you mean by “carve a new space in the indie landscape.” What is the point of “carving a new space in the indie landscape” if there is no money to be made there? I would not want to create a ghetto for female literary writers.

Although they aren’t necessarily self-publishing, many writers of literary fiction are experimenting on digital platforms. For example, David Mitchell wrote and delivered his short story “The Right Sort” entirely in tweets, Teju Cole crowdsourced his short story “Hafiz” on Twitter, and the Twitter Fiction Festival is continuing to gain traction. Other writers are publishing digital shorts or flash fiction through their current publishers or online literary sites. What digital trends do you foresee in literary fiction?

VB: I wish I had a crystal ball! I think we cannot begin to imagine how the publishing world will change in the next five years. The word is that e-book sales are plateauing. We may all be reading shorter fiction on our phones or even on our watches. We are waiting to see if Oyster and Scribd will turn into the Netflix of books.

AP: I see writers of literary fiction making increasing use of digital platforms to access and communicate with their readers. Audio seems to be experiencing a revival. Medium, a publishing platform, is attracting many talented authors who are posting their work in the hopes of attracting the attention of readers and publishers. Serialization is something that many publishers are experimenting with.

Vicky Bijur (@VBLA) started her agency in 1988 after working at Oxford University Press and with the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. She represents fiction and non-fiction. In the last few months, three of her books have been on the NY Times bestseller list: Hush Hush by Laura Lippman and Still Alice and Inside the O’Briens by Lisa Genova. Vicky has served as president of the Association of Authors’ Representatives and is currently Chair of its Ethics Committee. She is especially proud of the films that have been made of Drive by James Sallis; Still Alice by Lisa Genova; Every Secret Thing by Laura Lippman; and The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel.

(@VBLA) started her agency in 1988 after working at Oxford University Press and with the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. She represents fiction and non-fiction. In the last few months, three of her books have been on the NY Times bestseller list: Hush Hush by Laura Lippman and Still Alice and Inside the O’Briens by Lisa Genova. Vicky has served as president of the Association of Authors’ Representatives and is currently Chair of its Ethics Committee. She is especially proud of the films that have been made of Drive by James Sallis; Still Alice by Lisa Genova; Every Secret Thing by Laura Lippman; and The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel.

Ayesha Pande (@agent_ayesha) has worked in the publishing industry for over twenty years. Before becoming an agent Ayesha was a senior editor at Farrar Straus & Giroux. She has also held editorial positions at HarperCollins and Crown Publishers. She is a member of AAR (Association of Author’s Representatives), PEN, the Asian American Writer’s Workshop, and sits on the advisory board of the German Book Office. She has attended numerous writing conferences including Muse and the Marketplace, Aspen Summer Words and the Miami Writer’s Institute. She has taught college level courses in editing. She holds a master’s degree from Columbia University. She represents a wide array of fiction, nonfiction and YA.

Ayesha Pande (@agent_ayesha) has worked in the publishing industry for over twenty years. Before becoming an agent Ayesha was a senior editor at Farrar Straus & Giroux. She has also held editorial positions at HarperCollins and Crown Publishers. She is a member of AAR (Association of Author’s Representatives), PEN, the Asian American Writer’s Workshop, and sits on the advisory board of the German Book Office. She has attended numerous writing conferences including Muse and the Marketplace, Aspen Summer Words and the Miami Writer’s Institute. She has taught college level courses in editing. She holds a master’s degree from Columbia University. She represents a wide array of fiction, nonfiction and YA.

May 26, 2015

Is Self-Publishing a Good Springboard to Traditional Pub?

Over at Writer Unboxed, I’ve contributed a post to help authors understand how and when they can transition to traditional publishing from self-publishing. Here’s a brief snippet:

Back in ye olden days of self-publishing (before e-books), the message to authors was simple: Don’t self-publish a book unless you intend to definitively say “no” to traditional publishing for that project. Yes, there was a stigma, and in some ways, it helped authors avoid a mistake or bad investment.

Today, with the overselling of self-publishing, too many authors either:

Decide they won’t even try to traditionally publish, even if they have a viable commercial project, or

Assume it’s best to self-publish first, and get an agent or publisher later.The assumption of #2 is one of the worst in the community right now. As far as #1, some authors end up self-publishing for the instant gratification (we have a serious epidemic of impatience), or to avoid what’s increasingly seen as a long, exhausting, and dumb process of finding an agent or securing book contract (which, of course, offers less profit than self-publishing).

I support entrepreneurial authorship, and authors taking responsibility for their own career success. But I would like to see more authors intelligently and strategically use self-publishing as part of well thought out career goals, rather than as a steppingstone to traditional publishing.

Read my full post: How to Secure a Traditional Book Deal By Self-Publishing.

May 22, 2015

Meet Me in Charlottesville on May 23

Tomorrow at 4 p.m., I’ll be at New Dominion Bookshop in Charlottesville, VA, sharing stories about growing up in rural Indiana with a Russian Jewish father. (The video above, showing me and my dad, features a sneak peek at some home videos I’ll be showing! If you can’t see the video, click here.)

Elizabeth Derby did a wonderful write-up and preview in Cville Weekly.

The event is part of a nationwide 9-city book launch for Every Father’s Daughter. I’ll be giving away a signed copy of the book with signatures from other contributors, including the book’s editor, Margaret McMullan, and Phillip Lopate. I’ll also bring matzos to snack on.

May 21, 2015

How to Evaluate Hybrid Publishers

by LaurPhil / via Flickr

Starting this month, I’ll be writing a regular column for Publishers Weekly/PW Select on topics of interest to indie authors and the self-publishing community.

My first column tackles the issue of hybrid publishers, or those services that don’t really fit the definition of traditional publisher or self-publishing service. It can be difficult to evaluate such companies and determine if the value they’re providing is worth the investment. I offer a beginning list of considerations.

Read the full piece, Not All Hybrid Publishers Are Considered Equal.

May 20, 2015

5 On: Josip Novakovich

In this 5 On interview, Josip Novakovich discusses expectations vs. reality, the role of writing instruction, trends in writing, and more.

Josip Novakovich (Croatian: Novaković) is a Croatian-American writer. He was born (in 1956) and grew up in the Central Croatian town of Daruvar, and he studied medicine in the northern Serbian city of Novi Sad. At the age of twenty he left Yugoslavia, continuing his education at Vassar College (B.A.), Yale University (M.Div.), and the University of Texas at Austin (M.A.). He has published a novel (April Fool’s Day), three short story collections (Yolk, Salvation and Other Disasters, Infidelities: Stories of War and Lust), two collections of narrative essays (Apricots from Chernobyl, Plum Brandy: Croatian Journeys) and two textbooks (Fiction Writer’s Workshop, Writing Fiction Step by Step). Novakovich has taught at Nebraska Indian Community College, Bard College, Minnesota State University Moorhead, Antioch University in Los Angeles, and the University of Cincinnati, and is now a professor at Pennsylvania State University.

Novakovich is the recipient of the Whiting Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, two fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts, an award from the Ingram Merrill Foundation, and an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation. He was anthologized in The Best American Poetry, the Pushcart Prize collection, and O. Henry Prize Stories.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: Was there ever a point at which you felt you had “made it” as a writer?

CHRIS JANE: Was there ever a point at which you felt you had “made it” as a writer?

JOSIP NOVAKOVICH: My moods ebb and flow. I felt like I had made it when HarperCollins signed me up for two books—but that lasted only a few days, that sensation. And when I got the Whiting Award, I imagined for a day or so that writing and publishing would be easier than it had been. Now I just have the impression that writing, at least mine, is a permanent state of shortcomings.

You use your texts on writing as a guide for your classes. What value do writing classes add to the development of writing skills?

Well, that’s pretty individual. Some people respond well to coaching, and others hate it and do better on their own. For most developing writers it’s good to be in a workshop now and then to see how others read their work, to see how they communicated, what carries across the I and Thou divide. And sometimes there are even a few technical tidbits one picks up in a workshop, such as how to cross out superfluous and implied words.

You’ve said you recently began using more sentence fragments “like my students.” This sounds suspiciously like a writing trend. What do you see happening in today’s writing that is exciting or interesting, and what do you wish today’s writers would stop doing (in addition to overusing fragments)?

Well, in some cases hypertextuality and multi-mediality, all sorts of links in the work leading out of it to other sites and information—that seems exciting and mind-expanding.

I am tired of the present tense and the “you” POV, though. To begin with, the present tense is usually a violation of grammar in current fiction usage. He now stands in the door and waits for Helen. . . . The present simple works if we say often, and if we mean repeated action. But if we mean this moment, we should correctly write: He is now standing and waiting. . . . But that is not how people usually put it when they write in the present tense.

Past tense gives you confidence that the event is over and you can relate it and shape it, but the present action, while immediate, is unformed, and frequently that is how the writing these days appears to be, unformed and unplotted and unconsidered and untold. I shouldn’t generalize, but often that is how it is.

How do you approach the writing of a short story collection? Do you write the stories as they come to you and then select the ones that fit into a unifying theme, or do you first identify a theme and then write to it? Is there a “right” way to do it?

How do you approach the writing of a short story collection? Do you write the stories as they come to you and then select the ones that fit into a unifying theme, or do you first identify a theme and then write to it? Is there a “right” way to do it?

I just write stories and then I put them together, sometimes even if they don’t quite fit. It’s a collection, usually, not of linked stories, in my case. Of course, linking is preferable, usually, as you can claim it’s a novel, and your agents and editors will love you then.

Is crossing genres something you would advise or discourage in other writers?

I have often crossed genres from fiction into nonfiction and back, and then called the work fiction. It’s good to fertilize stories with genuine impressions and observations and journalism. The other way round, to invent in a piece of nonfiction, not so.

5 on Publishing

One of the first rules of marketing or promoting your published writing is, “Have an author website.” Why don’t you have one?

I used to have one, but I didn’t heed the warning that the carrier was discontinuing services and to move it to another one, so I lost it, and somebody in Japan bought the rights to my domain name, josipnovakovich.com, and I never felt like pursuing the issue to get it back. I think with Google, Facebook, etc., anybody who wants to find information will find it, and websites won’t change much.

You’ve been called “the best American short stories writer of the decade” by Kirkus Reviews. How easy (or how much of a challenge) is it for you to find desired publishers for your work at this point?

At the moment it is hard again, as my book sales with HarperCollins haven’t been great, and they have been low with my last publisher, Dzanc, but next round I will be a better promoter of my work.

It’s difficult for many writers to condense their own novels into one or two compelling paragraphs for a query letter. Is this something that can be taught, and do you have any tips/ideas based on what has worked for you?

It’s difficult for many writers to condense their own novels into one or two compelling paragraphs for a query letter. Is this something that can be taught, and do you have any tips/ideas based on what has worked for you?

It does depend on the novel. A thematically sharply focused novel is easy, as is a well-plotted novel, but psychological and literary ones often can’t be amiably squeezed into a paragraph. Well, what would you say about Remembrance of Things Past? Or War and Peace? Give me a zinger for one of these.

Have you had work you knew was good rejected by publishers? If so, what did you do with the rejected/unpublished material?

Well, yes, I have had and have such work, and I sometimes neglect it for a couple of years and then give it another spin. Maybe revise again, or maybe just send again, and place somewhere. In some cases, I know I have a good story and nobody bites, and then I publish it online or in a small journal when solicited for work.

Do you think you would ever self-publish?

Sure. I think the more effective the internet is, the more likely it is that I will. But then I’ll have to have a website, won’t I?

Thank you, Josip.

May 19, 2015

Begin Your Novel with Action: A Good Rule?

by Ralph Aichinger / via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is adapted from The Irresistible Novel by Jeff Gerke (@JeffGerke), published by Writer’s Digest Books.

You’ve probably heard the adage that you must begin your novel with action—even if it’s not the main action of the book. While this rule is fairly well-accepted in fiction teaching circles, not everyone agrees with it.

What does it mean to begin a novel with action? Usually, car chases and explosions come to mind. But a lot of novels don’t have a single car chase and nary an explosion in the whole book, so then what would “action” constitute? It could be a ballgame, an argument, a stage performance, someone’s death, or a mysterious discovery. So long as it strikes the right tone for the novel to come, any of these would be good choices.

But what if the writer doesn’t want to begin with anything active happening at all? Must a novel begin with action of some sort? Is there no other option?

We know there are great ways to begin a novel that are not action by almost anyone’s definition.

Call me Ishmael.

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Granted, those are just opening lines, not opening scenes, and those are drawn from novels of yesteryear. But the point remains that it’s possible to have a great novel that doesn’t begin with a tank blowing up.

What about a novel that begins with the unique voice of the narrator? What about a novel from the lyrical prose school of fiction?

My fourth novel begins with the hero finding out that he’s been assigned to kill someone—but the scene itself consists mainly of thinking and talking, not your typical description of an action-packed beginning.

Why It’s Often Smart to Begin with Action

Those who advocate beginning a novel with action want your reader to be immediately engaged in your book. The boring beginning, they argue, could prevent your reader from becoming your reader at all. Sometimes I’ll read a book’s first page—or even just its first line—to see if it hooks me, and if it doesn’t, I put it down and keep looking.

Would you keep reading a novel that began like this:

Ruth had already gone upstairs twice that morning to try to wake Johanna. Both times her sister had grumbled something that led her to believe—wrongly, as it turned out—that she really was going to get up. Why do I always fall for it, every single day, Ruth scolded herself as she climbed the stairs for the third time.

Now, this is the beginning of The Glassblower by Petra Durst-Benning, and on the day I wrote this, it was the No. 1 book in Amazon’s historical romance category, so apparently it was selling just fine.

But I personally wouldn’t keep reading it, and not just because I’m not a fan of romance novels. It’s just boring to me. It feels mundane, safe, and even tedious, which is what my life too often feels like as it is. I don’t come to fiction for more of that. There’s nothing of danger or intrigue here. I would just keep looking.

Would you continue reading a novel that begins like this next one:

It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the atters and charcoal ruins of history.

Wow. Well, I personally would keep reading that. It has both action and surprise, both danger and the unexpected. I wonder what in the world is going on, and I feel my brain perk up with all its information about staying safe when around open flame. Apparently, readers have been able to stick with this book fairly well over the years. It’s the opening of Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury.

Give your reader danger, action or surprise in the beginning, and he’ll have a hard time not sticking with your book.

Agents and editors are like that, too. They may have 63 other proposals they’re trying to get through before lunch, and if a novel doesn’t grab them right away, they lay it aside and move on to the next one in the stack. Even if the first line or two grabs him, when an agent or editor sees a novel that begins with someone thinking or a description of the clouds or a massive information dump about the history of something, he knows the odds are this book isn’t a winner.

Readers want to be swept away by a novel. Unless a novel has been recommended strongly by people they trust—or written by someone they’re related to—they’re not going to give that novel much of their time if it doesn’t grab them right away. Starting with action is the most surefire way to engage. The other way to engage is to begin with something unexpected or fascinating happening. But it’s in your best interest to begin with either action or surprise—or both.

How Do You Engage the Reader from the Beginning?

I don’t see any question that the very first line, paragraph, page, scene, and chapter of a novel must engage the reader. She’s got a hundred other things she could be doing and a billion other entertainment choices vying for her attention. My great commandment of fiction is that you must engage your reader from beginning to end. Well, how can you engage the reader at the beginning?

I’m going to go really vague here, but hopefully it will be helpful: You engage your reader by writing something interesting. (I almost wrote “You engage your reader by writing something engaging,” but that would be circular and frustrating. Aren’t you glad I didn’t write that?)

Seriously, though, you’ll find 101 ways to engage someone in a story you want to tell. You can engage through pyrotechnics or poetry, through mayhem or music, through action or anguish. Yes, a car chase or explosion might be engaging, but so might the consumption of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, if written well enough.

The point isn’t what sort of engagement you use. The point is that you engage.

If starting with traditional action fits your novel and engages the reader, do it. If starting with nontraditional action, like cracking a safe or finding the last Easter egg, fits your book and engages your reader, it’s all good. And if you can pull off an opening that doesn’t have action by any definition and yet nevertheless fits your novel and truly engages the reader, then you should do it.

I have begun some of my novels with action, some with nontraditional action, one with a discovery, one with a cryptic discussion, and one with a decision.

In my opinion, the point isn’t to begin with action, but to engage. However you feel like accomplishing that, either through action or surprise, so long as you do accomplish it, I’d call it a win.

To learn more about engaging your reader, check out The Irresistible Novel by Jeff Gerke, recently released by Writer’s Digest Books.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers