Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 150

April 23, 2015

Be a More Productive Writer While Also Achieving Balance

by Luba M. via Flickr

Today’s guest post is by Jordan Rosenfeld (@JordanRosenfeld) and is an excerpt from A Writer’s Guide to Productivity, published by Writer’s Digest.

Surely you know one or more prolific writers who produce so much material that you wish you could bottle their energy and drink it down later for yourself.

Perhaps you even feel a little envious or resentful of their output: Hey, that could be me if only I didn’t have to [fill in the blank].

It’s easy to believe that a large quantity of writing is a sign of productivity, and thus, if you are not writing reams yourself, you aren’t being productive. But more writing does not necessarily equal better-quality writing, nor does faster writing lead to faster achievement of your goals.

The Pros and Cons of Fast Drafting

For at least six years, I, like millions of other slightly crazed, well-intentioned writers, have participated in NaNoWriMo—National Novel Writing Month—in which writers attempt to produce a 50,000-word novel in thirty days while running on caffeine, blind faith, and a spirit of adventure. The part of me that is like an endurance athlete always thinks this sounds like a great idea and enjoys the endorphin rush of writing toward a fast finish. And it is fun at various stages—particularly at the beginning before reality has set in. But you know what the honest truth is? It kills me every year. By the end of November I am the crankiest, most burned-out, and spent writer I know.

I’m not saying not to do NaNoWriMo—in fact, on the contrary, I think every writer should do it at least once to experience what a true writing marathon feels like. However, just because you write something fast doesn’t mean it will be complete and publishable when you reach the finish line.

So if you are going to undertake fast drafting, be prepared to come out of those sessions with a lot of work left to do. Accept that what you write quickly may need more revision later. And don’t beat yourself up because you didn’t write a fully finished masterpiece in thirty days or less; great works aren’t written in one sitting. Consider, too, that you may need a lot of downtime after the intensity of the process—and that’s time away from your writing, which might ultimately be counterproductive to your overall output.

Set Manageable Goals and Intentions

All of this brings me to a very important topic for making yourself productive in a balanced way: intentions.

When I teach plot and scene to my writing students and clients, I stress the importance of characters having smaller intentions in every scene and larger dramatic goals to move the story along. A character without intentions wanders around her narrative. A plot without goals is a series of interesting but disconnected vignettes.

The same is true for your writing life. Intentions are daily motivators in small, manageable pieces; they spur you into action and carry out your tasks on the way to your goals. Your goals are the big-picture items—to be a published author, to have that story you wrote accepted by The New Yorker, to query literary agents—built from the efforts of your intentions. The more intentions you create for yourself, the more likely you are to follow through.

Don’t Make To-Do Lists

From here on out, I’d like you to stop making to-do lists. Nothing causes more anxiety than a list of items looming like a dictator with instructions to do! You can all but feel a whip being cracked at your rear, can’t you?

Instead, set yourself up with daily intentions. Intentions are a kinder, gentler way to nudge yourself along. In fact, I recommend that you make a master list of action items for the week or month, and keep it in a binder. Each day choose only the most crucial items from the master list and write them on an erasable whiteboard, which will then serve as your daily intentions list. I do believe in creating parameters for your writing so that you are less likely to sit at your desk panicking in front of the blank page because you don’t know where to start. Just don’t create so many parameters that you stymie yourself.

Some examples of the kinds of intentions you can set for a writing session are:

to outline a scene

to write a specific number of words

to write a piece to a specific theme or for a specific publication goal (a contest, a writing prompt)

to finish a non-writing-related project that is keeping you from your writing

to pick up a scene or story where you left off last time.

Try to avoid putting items like this on your daily intentions list:

Finish my novel

Write one hundred pages

Plot out a new seven-book series today.

You have to learn to corral and guard your writing time so that you use it wisely. It also means that you need to be careful not to set yourself up for failure by heaping more on your plate than you are liable to do or capable of completing. Voracious and prolific writing does not equal success.

How to Set Meaningful Long-Term Writing Goals

If you have one big, intimidating goal, such as “Get published by Random House,” that’s fine, but what does it really mean?

Consider the smaller steps that will make your goal possible. If your goal comprises a series of many smaller intentions along the way, then you might begin to look at it as doable. Goals that maybe once seemed out of reach become possible: A novel is written, after all, in a series of small, manageable scenes and chapters, not necessarily in a month.

Next Steps

Buy yourself an erasable whiteboard on which you can write your daily intentions. Don’t keep a long list of all your intentions in an overwhelming list in front of you. (you may have a master list you keep in a notebook, but hide it away.) Every day, erase yesterday’s intentions and copy only intentions from your master list that you can do that day. Try not to overachieve; instead strive to accomplish tasks in manageable chunks. Try to include “writing” on your daily intentions list every day, and remember to start with the most pressing task (anything that is deadline driven or that is driving you crazy) to get it out of the way.

Which of your goals seems more in reach? Break down

this goal into a series of smaller intentions or just the intentions you will set for your next session. What goals do you have that should be pushed off to a later date?

this goal into a series of smaller intentions or just the intentions you will set for your next session. What goals do you have that should be pushed off to a later date?Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend taking a closer look at A Writer’s Guide to Persistence by Jordan Rosenfeld.

The post Be a More Productive Writer While Also Achieving Balance appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jordan Rosenfeld.

April 22, 2015

5 On: Carol Hoenig

In this 5 On interview, Carol Hoenig (@AuthorsGuide) shares her writing influences, reveals what she’ll be looking for when stocking the shelves of her own coming-soon bookstore, and explains what makes an author attractive to the media.

Carol Hoenig is a full-time freelance writer and publishing consultant. Her novel Of Little Faith was published in October 2013. She is the multi-award-winning author of the novel Without Grace, and her book The Author’s Guide to Planning Book Events was named Best of Long Island Author 2012 by the Long Island Press and Outstanding Advocate for the Arts 2013 by the Long Island Arts Council. Her stories are in numerous anthologies, she blogs for The Huffington Post, and she teaches continuing education courses at Hofstra University. In addition, she and a business partner are on a journey to open a bookstore/community center in Rockville Centre named Turn of the Corkscrew, Books & Wine.

5 Questions on Writing

CHRIS JANE: When you decided you wanted to write the story of your battle with religion, which eventually became the novel Of Little Faith, you hadn’t written much, if any, fiction (a lot of poetry, a play). To learn more about how to write a short story, you began reading for instruction rather than for leisure and discovered you needed a compelling plot to surround your core idea. What else did you learn in your early days of teaching yourself to write that has stuck with you, and what writers or stories were most influential to you?

CAROL HOENIG: Well, believe it or not, Of Little Faith started out as a memoir, since I needed to share what I saw and experienced in a bible-thumping fundamentalist believing church, but two weeks into writing it, I realized no one would care what I had to say. That is when, oddly enough, Laura Sumner, the protagonist in Of Little Faith, spoke to me for the first time by saying, “I never meant to hurt anybody.” I needed to explore that.

It was the first novel I’d written, but not the first I had published. I had the first draft written in a month and a half, but it took about seventeen years—and as many drafts—for it to get published. (I had a small publisher on Long Island that wanted to publish it early on, but I backed out of the deal since the editor had an ax to grind with religion and wanted me to change some things in it to satisfy his agenda. I backed out of that deal and had to wait many years before Steel Cut Press came along.)

So, what did I learn? To let the story unfold even if you have an outline; this became all the more apparent when I wrote Without Grace. Even though there’s not much of Grace in the novel, hence the title, she wasn’t why I wrote that work in the first place. I’d planned to use an actual event that had happened in the small town I was from, but when I moved the plot in that direction, the characters put the brakes on and said, “That never happened to us.” It was amazing how the story that needed to come out then flowed. And, by the way, Grace started out living at home with her family, but she served no useful purpose and became all the more powerful when she was MIA.

As for what writers/stories influenced me: Well, of course, To Kill a Mockingbird is a given, but I also like A.S. Byatt’s Possession. It’s so intricate. I like any novel that doesn’t cop out or doesn’t try to please the masses. When I decided I wanted to write fiction, I began reading a lot of bestsellers to learn and found that many of them were just horrid, and instead of showing me how to write, they taught me what to avoid if I wanted to honor the craft. So, I learned from those I didn’t respect as writers as much as those I do. Yes, they are on the bestseller list, but I look at it that many people are satisfied with fast food while missing out on fine dining.

One agent who offered to consider Of Little Faith (and who, because a different agent claimed to have tried to sell it to publishers already, wouldn’t pitch your completed second novel) changed her mind after reading it because she was insulted by the subject matter. I don’t think I’m alone in assuming the more controversial a story is, the better the marketability (controversy = attention, any press is good press, all that). Were you surprised by the reaction, and did it change how you approached writing in the future?

One agent who offered to consider Of Little Faith (and who, because a different agent claimed to have tried to sell it to publishers already, wouldn’t pitch your completed second novel) changed her mind after reading it because she was insulted by the subject matter. I don’t think I’m alone in assuming the more controversial a story is, the better the marketability (controversy = attention, any press is good press, all that). Were you surprised by the reaction, and did it change how you approached writing in the future?

I was surprised and wasn’t sure why such a reaction. It may have been something personal to her, but, no, it didn’t change my approach at all. And, funny enough, I had the opportunity to cross paths with this agent again recently at a luncheon. She remembered me and congratulated me on my successes. Kind of funny, actually.

Did you ever consider contacting any of the publishers the agent claimed to have pitched to verify they’d been told about your manuscript? I understand this is at the top of the faux pas list; however, what’s a writer to do if s/he suspects an agent is demolishing a book’s chances?

I had hoped that the agent would, because I knew that I would only look like a disgruntled wanna be writer. The agent said she couldn’t approach these publishers because it was her reputation on the line, that she couldn’t waste their time with something they’d supposedly already considered, which is why I am grateful to Steel Cut Press for giving me the opportunity.

I would say make it clear at the beginning that you as an author want to be kept apprised of where the agent pitched the manuscript and that you want to know the editors’ comments when they reject it, since it will help you as an author decide whether their points are valid. Sometimes editors simply recently purchased a similar manuscript and cannot accept another one like it. Other times, they may think it just doesn’t fit their list; however, the agent should be aware of that ahead of time. So, make sure your agent will stay in communication with you, but you as an author be sure not to be a pest and call them every day asking what is going on with your manuscript.

What was the most challenging moment, writing-wise, in your time trying to get either novel published, and what helped you keep moving forward even knowing that what you were offering might be a tough sell because it didn’t slide neatly into a category?

Initially, the most challenging was to actually believe that I could consider myself a writer. Here I was, this “kid” from an extremely small town in upstate New York. What did I know about writing? So each time I got a rejection—and in the beginning, all the rejections came to me via snail mail in self-addressed return envelopes where I’d paid the postage—I would be heartbroken, wondering, What do these agents want? Some rejections were without any reasons, but they eventually included more personal supportive replies telling me, basically, that it wasn’t me but them—they just didn’t think they could sell it. It helped a bit, but it was still a rejection, and why couldn’t they sell it? I’d have a good cry, swear that I wasn’t going to keep at it and keep wasting my time, but by day’s end, I had gotten over it and just went back to writing.

And, I guess it was more about the story I wanted to write rather than trying to fit into any category. I don’t consider myself a literary writer, nor do I consider myself to be a commercial fiction writer—I think I’m somewhere in the middle.

Having experienced so many sides of the writing life (writing, publishing, hosting events at Borders for the likes of Kurt Vonnegut and David Baldacci, etc.), it seems there’s little you aren’t prepared for, as a writer. But what still makes you nervous today when you start a new project? What is the one particular writer fear no amount of experience will squash?

I don’t feel any fear. I first write for myself and know that not everyone is going to like it. I suppose uncertainty would be more like it. I do ghostwriting projects for those who don’t consider themselves to be writers but who have a story to tell, and sometimes handling their story can be a bit nerve-racking because they want everything to be told. I try to explain that doesn’t work, that the reader doesn’t care what you said to so-and-so, that it does nothing to advance the story. I have to help educate those who want to have their story published about what to put in and what to keep out.

5 Questions on Publishing

You decided to open your own publishing consulting business following Without Grace’s publication. What lessons learned while getting your own novel published became most valuable or useful to your approach in promoting the work of others?

You decided to open your own publishing consulting business following Without Grace’s publication. What lessons learned while getting your own novel published became most valuable or useful to your approach in promoting the work of others?

I found when I was promoting my novel most interviewers weren’t interested in talking about fiction. However, when I could pull something from it, which I did, that mirrored what was happening in reality, I got the attention of one particular newspaper writer because I was willing to weigh in on the topic. What I got out of it was a long article in the newspaper and most of it was about my novel, while one reference was made about the issue occurring in the region regarding wind turbine energy, of all things. (There is an environmental storyline in Without Grace.)

So, when I do publicity for fiction writers, I try to get them to look at the possibilities of pulling something from the novel that reflects what is going on in reality, if that makes sense, and be willing to discuss it as someone with an informed opinion.

What realistic expectations should an author have when considering hiring a consultant or a publicist?

That it is a team effort. I have had some authors who wanted me to do all the heavy lifting without promoting their own work. In today’s social media environment, that is confounding. Thankfully, Oprah no longer has her daily talk show, because when she did every author I worked with wanted me to get their book in her hands. One author was even willing to pay to have me fly to Chicago, sit in the audience, and then hand her the book when she came out. Uh, right.

It is the educated author on the business side of publishing who is my best client.

You and a business partner will soon open a bookstore in Long Island: Turn of the Corkscrew Books & Wine. Will you consider self-published books, and if so, what will it take for a self-published book to make it onto your shelves? Most bookstores are concerned with returnability, naturally, but will there be other considerations?

Yes, definitely returnability, but it also must be professionally edited. Also, we will first consider local self-published authors since they will send family and friends in to purchase the book while there are other self-published books from authors around the country whose work deserves space on the shelf. My business partner and I will have to decide just how to go about that. We will be doing a lot of hand selling, though, for books we love and will be thrilled to introduce readers to writers who aren’t recognizable names. Many of them are what would be called “midlist authors.”

When you contact reviewers or interviewers on behalf of the authors you’re promoting, what are some of the questions you’re asked about the authors that will help determine whether they’re given reviews/space/time? And what will help an author’s chances, particularly if self-published?

I am always asked who is distributing the book and whether it’s returnable. If it is for radio or television, interviewers like to know if the author has had any media training. Getting attention for any book, whether it is traditionally or self-published, is so difficult so the book has to have as much going for it as possible.

You’ve published with iUniverse (which solicited Without Grace) and a small press (Of Little Faith is with Steel Cut Press). In your experience as a writer and as a publishing consultant, if a person can find good, affordable design, hire an editor, and neatly format their own interior, what are the benefits of publishing with a small press? Does it all come down to perception and improving chances with reviewers and bookstores, or is there more to it than that?

You’ve published with iUniverse (which solicited Without Grace) and a small press (Of Little Faith is with Steel Cut Press). In your experience as a writer and as a publishing consultant, if a person can find good, affordable design, hire an editor, and neatly format their own interior, what are the benefits of publishing with a small press? Does it all come down to perception and improving chances with reviewers and bookstores, or is there more to it than that?

Well, it has definitely changed over the last several years since there are some big-named authors who have decided to bypass the traditional publisher and do it very well, but that is because they have already built their brand. The unknown author should always try to get a traditional publishing deal at first since it will give them so many advantages, but if that isn’t working out and they have taken the time to write a good book, which may take years, then I say go the self-publishing route—but don’t expect to make a living from it. Even most traditionally published authors cannot make a living from their writing alone.

Thank you, Carol.

The post 5 On: Carol Hoenig appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Chris Jane.

April 20, 2015

The Best Websites for Writers

I’m delighted to announce that this site (JaneFriedman.com) has been named a 101 Best Website for Writers in the newest issue of Writer’s Digest (May/June 2015). This is the third year in a row my site has been honored.

If you’re not familiar with this annual feature, 101 Best Websites for Writers has been compiled by the editors at Writer’s Digest for more than 17 years. It’s organized into eight categories:

Creativity

Writing advice (where this site falls)

Agents

Publishing/marketing resources

Jobs and markets

Online writing communities

Genres/niches

Just for fun

I’d like to offer a quick shout-out to a few other winners whose sites I frequent!

Writer Beware by Victoria Strauss

Writer Unboxed, hosted by Therese Walsh, where I’m a columnist

Agent and Editor Wishlist

The Book Designer by Joel Friedlander

The Independent Publishing Magazine by Mick Rooney

The Creative Penn by Joanna Penn

Bo Sacks by Bo Sacks

The entire list is full of worthy and wonderful sites; get your Writer’s Digest issue to see them all.

The post The Best Websites for Writers appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 17, 2015

Updated: The Key Book Publishing Paths in 2015 [Chart]

In 2013, I created an informational chart about the key publishing paths, which was far more popular than I anticipated. I still get many requests to distribute it at conferences, plus interview requests to discuss it.

Given the pace of change, it was time to update it. Read on for an explanation of what’s changed or download now.

One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today:

Should I traditionally publish or self-publish?

This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing—with evolving models and varying contracts.

You won’t find a universal, agreed-upon definition of what it means to “traditionally publish” or “self-publish.”

It’s not an either/or proposition. You can do both. (See this interview with CJ Lyons.)

There is no one path or service that’s right for everyone; you must understand and study the changing landscape and make a choice based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

My chart divides the field into three identifiable forms of traditional publishing and three identifiable forms of self-publishing.

Traditional publishing: I define this primarily as not paying to publish. One of the growth areas you’ll find here are no-advance deals and digital-only deals that offer a low advance, if any at all. Such arrangements reduce the publisher’s risk, and this needs to be acknowledged if you’re choosing such deal—because you aren’t likely to get the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution. The digital-only category is best described with the Wild West cliche: You’ll find very new presses here who don’t know a thing about publishing, as well as established New York houses launching innovative imprints.

Self-publishing: I define this as paying to publish or publishing on your own. Compared to the earlier version of this chart, I’ve gone into more detail about full-service and assisted models. This is where significant growth and innovation is happening. The AuthorSolutions star is fading fast (especially with the pending lawsuit), and more companies are entering the field with premium services and the promise of quality selection or curation. However, there’s still a very high risk of paying too much money for basic services, and also for purchasing services you don’t need. If you can afford to hire a company to help you self-publish, use the very detailed reviews at Independent Publishing Magazine by Mick Rooney to make sure you choose the best service for you.

Feel free to download, print, and share this chart wherever you like. (It’s formatted to print perfectly on 11″ x 17″ or tabloid-size paper.) I will keep developing it as the publishing landscape changes, so leave a comment if you have suggestions for how to make it more helpful.

For more information on getting published, visit these posts:

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published

Start Here: How to Self-Publish Your Book

How to Publish an E-Book: Resources for Authors

10 Questions to Ask Before Committing to Any E-Publishing Service

The post Updated: The Key Book Publishing Paths in 2015 [Chart] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 15, 2015

Free Class on Content Marketing

On April 15–17, the Alliance of Independent Authors is hosting IndieReCon, a free online conference on self-publishing and reaching readers. (They’re also live-streaming the Indie Author Fringe Festival from the London Book Fair.) Speakers include Bella Andre, Victoria Strauss, CJ Lyons, Jessica Bell, Mark Coker, Joanna Penn, Joel Friedlander, Roz Morris, H.M. Ward, and many more.

I offered the session above on on content marketing.

View the full event schedule here.

The post Free Class on Content Marketing appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

Today From Jane: Free Class on Content Marketing

On April 15–17, the Alliance of Independent Authors is hosting IndieReCon, a free online conference on self-publishing and reaching readers. (They’re also live-streaming the Indie Author Fringe Festival from the London Book Fair.)

I’m doing a session on April 15 at 1p ET on content marketing. Other speakers include Bella Andre, Victoria Strauss, CJ Lyons, Jessica Bell, Mark Coker, Joanna Penn, Joel Friedlander, Roz Morris, H.M. Ward, and many more.

View the full event schedule here.

The post Today From Jane: Free Class on Content Marketing appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 14, 2015

Interview with Jane: Understanding the Business of Authorship

My most recent interview is now available with author and editor Ally Bishop, who runs the professional editing business Upgrade Your Story and its related podcast.

In our 40-minute discussion, we cover how to understand your business as an author and expand your personal brand beyond just book sales. Click here to listen.

The post Interview with Jane: Understanding the Business of Authorship appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 10, 2015

Do You Love Your Publisher: Author Survey Results

Last month, author Harry Bingham and I launched an author survey to explore the experiences and current leanings of traditionally published authors in the English language. The Bookseller in the UK originally reported on the survey here; it can catch you up on what we hoped to accomplish with this effort.

So the results are now in. We received 812 responses; you can view the entire dataset here if you’d like to wade through the figures.

The Bookseller has published a report on the results (including publishers’ and authors’ reactions), and Harry Bingham has done a thorough and excellent overview titled Grumbling, But Not Quitting, which accurately sums up the results.

The Major Findings (Not Surprising?)

Authors respect and value their publishers’ editorial and design skills.

Authors question their publishers’ marketing ability or philosophy.

Publishers don’t communicate well with their authors.

Authors value their agents more than their publishers.

Despite their complaints, most authors aren’t leaving their publishers.

Bingham writes in his analysis:

The traditional publishing industry often claims to have authors at its heart, but our results suggest, on the contrary, many authors feel somewhat excluded from it. Since communicating better with authors would not entail significant costs (and might, you’d think, bring some significant benefits), it would seem that our data provides a large clue as to how regular publishers could improve their operations. …

The formula for success is not hard to find. Talk to authors. Involve them. Ask for feedback. Then rinse and repeat. The more you solicit and respond to feedback, the better your results will be.

The Limitations of This Survey

If you look at my original post announcing the survey, you’ll find a few commenters who felt the line of questioning made some bad assumptions. Keep in mind that our goal was to recruit highly experienced authors, particularly those agented and actively working with a Big Five house. We succeeded in part:

Almost 80% have published within the last year

More than 60% have published six or more books

More than 60% have a literary agent

More than half are published by a Big Five house or by one of the larger independent houses (such as Perseus in the United States or Bloomsbury in the UK).

That said, there are limitations in the data:

As with some other well-known author surveys, like from Digital Book World, it’s a self-selecting survey. It’s not scientific, but we believe it is directionally useful.

The survey asked authors to base their responses on their most recent traditional publishing experience. We didn’t ask if authors were working with more than one publisher when they took the survey, or ask for authors to make comparisons among the publishers they’ve worked with. Harry’s analysis does comment on how responses differ when we filter them based on the size of publisher, the size of the advance, or the number of titles published by the author. In most cases, there is no difference in authorial attitudes.

For agent-related questions, we neglected to add a N/A option for those authors without agents, but it was possible for respondents to skip questions.

I highly recommend reading Harry’s analysis, then also take a look at The Bookseller’s report by Sarah Shaffi. You can also join a live chat on Twitter today hosted by Porter (follow #futurechat).

P.S. Earlier this year, I was invited to contribute a 5-minute video to a UK-based Hachette Books digital conference, answering the question: What is the biggest opportunity for publishers in the digital age? Below is the video I sent.

The post Do You Love Your Publisher: Author Survey Results appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 9, 2015

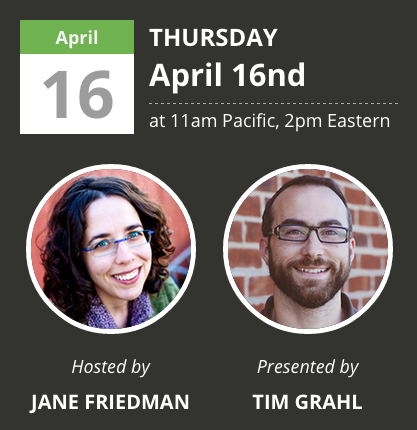

Free 1-Hour Class on Successfully Launching Your Book

The biggest question I get from writers these days isn’t how to get published. It’s how to market a book they’ve already published. And one of the more trustworthy experts I’ve found on this topic is Tim Grahl.

I first became aware of Tim through his many excellent blog posts on social media and online marketing. (Here’s a good post to start with: 3 Myths About Social Media for Authors.) I later met him in person at the World Domination Summit last summer, and found him as down-to-earth and insightful as he is online.

Grahl has worked with a range of bestselling authors, such as Daniel Pink, Pam Slim, and Hugh Howey. He’s also authored a book, Your First 1,000 Copies, which I’ve read. (I was pretty much nodding the whole way through.)

In any case, he knows what leads to long-term, sustainable success when it comes to book marketing, and I’m delighted to be featuring a 1-hour class with him next week. It’s called Predictable Book Sales: The 3-Step Framework to Build a Killer Launch.

You should attend this class if you’ve been writing a book and you want to guarantee you have a successful launch. He’ll cover:

The framework he’s used to launch #1 New York Times bestsellers

The No. 1 goal for every author (hint: it’s not selling books)

The top 5 tools every author should be using to build their predictable book selling machine

I know that many free webinars end with some kind of sales pitch for a course or service. While Tim is seeking to reach more people and build a list of interested people for future classes and services, this particular webinar doesn’t end with a pitch.

I hope you can join us.

Claim your free spot now

The post Free 1-Hour Class on Successfully Launching Your Book appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 8, 2015

5 On: Robert Kroese

In this 5 On interview, author Robert Kroese reveals the process that allows him to write up to three books per year, what makes humor work or flop, and how authors can increase their sales potential.

Robert Kroese’s sense of irony was honed growing up in Grand Rapids, Michigan—home of the Amway Corporation and the Gerald R. Ford Museum, and the first city in the United States to fluoridate its water supply. In second grade, he wrote his first novel, the saga of Captain Bill and his spaceship Thee Eagle. This turned out to be the high point of his academic career.

After barely graduating from Calvin College in 1992 with a philosophy degree, he was fired from a variety of jobs before moving to California, where he stumbled into software development. As this job required neither punctuality nor a sense of direction, he excelled at it.

In 2009, he called upon his extensive knowledge of useless information and love of explosions to write his first novel, Mercury Falls. Since then, he has three more books in the Mercury series; a humorous epic fantasy, Disenchanted; and a quantum physics noir thriller, Schrodinger’s Gat. His latest book is Starship Grifters.

5 Questions On Writing

CHRIS JANE: In a 2013 interview you conducted with author S. G. Redling, you mentioned after playfully admonishing her for genre-hopping (“You know you’re not supposed to do that, right?”) that you were also on the verge of switching genres, from humorous fantasy/sci-fi to thriller. You did, with your novel City of Sand. What challenges do you expect to face having changed genres? And was pleasing your agent, or Amazon, one of the challenges? I ask because City of Sand will be self-published, thanks to your successful Kickstarter campaign.

ROBERT KROESE: The short answer is that I expect not to sell a lot of copies of City of Sand. That book was basically an experiment to see if I could write a “serious” novel, and while I think it turned out well, it’s just too different from my other books (and too hard to describe without spoiling the ending) for many of my readers to take a chance on it.

ROBERT KROESE: The short answer is that I expect not to sell a lot of copies of City of Sand. That book was basically an experiment to see if I could write a “serious” novel, and while I think it turned out well, it’s just too different from my other books (and too hard to describe without spoiling the ending) for many of my readers to take a chance on it.

And to be perfectly honest, a novel like that isn’t nearly as much fun to write as something like the Mercury books or Disenchanted. I’m more comfortable writing humor, and that seems to be what my readers want, so I doubt I’ll be writing another serious novel for a while.

You write in your foreword to Temptation Bangs Forever: The Worst Church Signs You’ve Ever Seen, “There are few things worse than someone failing spectacularly at being funny.”

After you compare trying for funny vs. true funny to a drunk vs. someone who’s pretending to be drunk, you acknowledge that “funny” is subjective. Even so, for humor to succeed, a good number of people have to agree on what gets a laugh. Your books rely in large part on humor, and you commented recently on Facebook that you’ve sold 150,000 (or more) copies of your work, so you’re obviously doing it right.

Can you provide, for any aspiring humor writers, an example of true funny vs. trying to be funny? And do you think funny can be taught?

Humor is ultimately about setting up tension and then resolving it in an unexpected way. Essentially you’re asking a question and then providing an answer that is both satisfying and completely wrong at the same time. To use an extremely tired example: “Q: Why did the chicken cross the road? A: To get to the other side.” The answer is correct, but not in the way you’d expect.

Groucho Marx was a master of this:

“Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend. Inside a dog, it’s too dark to read.”

“I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I’ll never know.”

He sets up a situation and hints at a resolution, but the resolution, while satisfying, is also absurdly, grotesquely wrong. For some strange reason, the human brain loves little tricks like that.

That’s what I try to do in my books: set up tension and then resolve it in an unexpected way. The jokes range from puns and silly wordplay to broad concepts (like the conceit in Mercury Falls that Heaven is essentially just a ridiculously complex bureaucracy), but they all share the dynamic of setting up tension and then resolving it. How funny the joke is depends on how satisfying the resolution is, how unexpected it is, how well you time the punchline with the build-up of tension, and a lot of other things.

In humor writing, phrasing is extremely important. For example, you want the punchline to be delivered as close to the end of the sentence as possible (I think that advice originates with Dave Barry). That’s why it’s called a “punchline.” It has to hit you like a punch, as forcefully and abruptly as possible.

Subtlety is also key. Don’t try to be wacky. Wackiness works on TV; not so much in writing. Be very sparing in the use of exclamation marks. Try to make the joke seem like it just happened, like a magic trick. If the reader can see the effort that went into a joke, you drain it of its power.

So, a final answer to your question: no.

New work from you seems to publish almost annually. How fast/consistently do you write, and what is your editing routine?

New work from you seems to publish almost annually. How fast/consistently do you write, and what is your editing routine?

Faster than annually, actually. I’ve been writing 2-3 books a year for the past three years or so. I have no routine. I fret for weeks or months, trying to come up with an idea for a book that I think will work. Eventually enough of it comes together that I feel compelled to start writing things down. And then more ideas start to flow, and I write compulsively until the book is finished.

My first novel, Mercury Falls, took me three years to write because I had no idea what I was doing. These days I usually finish a book in 6-8 weeks.

I usually start by writing up a very general outline that’s around five or six pages long. This is mostly just a list of plot points that I know I have to hit somehow to get to the conclusion of the book. Once that’s done, I start writing. I sort of edit as I go, which I know most authors consider a bad idea, but it seems to work for me. That is, I’ll write a few chapters, then go back and read what I’ve written and make sure it works in terms of continuity and pacing, make any necessary tweaks, and then write a few more chapters.

I usually find myself diverging from the outline pretty quickly, either because I’ve come up with a better way of getting where I need to go or because I can’t get my characters to do what I want them to do. I never force things; if the plot requires a character to do something that I realize he or she just wouldn’t do, the plot has to give way to the character. Usually this results in a more interesting story that what I had in mind, anyway.

I really don’t know how some people plan out their books in great detail; for me, I often don’t know exactly what a character is going to do until I write the scene. Humor writing in particular has to leave a lot of room for spontaneity: you can’t possibly plan all the opportunities for humor that are going to come up as the plot unfolds. Occasionally I’ll write myself into a corner, but somehow it always comes together in the end.

Because I read everything over so many times as I’m writing, it’s usually pretty clean by the time I’m done. After I write the final chapter, I read the whole thing over a few more times and then send it to three or four beta readers for feedback. After I incorporate their feedback, I’ll read it over once or twice more and then send it to my editor. After he’s done with it, it goes to the proofreader.

I’ve only had an actual development editor for two books, Starship Grifters and City of Sand; for the others, I’ve just had a copy editor (and for some of my self-published books, I’ve had to rely on my beta editors for copy editing and proofreading). So other than the occasional typo or minor continuity error, the final published version is usually almost identical to the version I have on my hard drive. This is one reason that self-publishing is so natural for me: I’ve always cared too much about the quality of the final product to trust an editor to catch my mistakes.

You combine history, science, and religion in your work. You’re also very outspoken on social media, whether the conversation is politics, social issues, or everyday human behavior. How much of what you write is disguised political or social commentary, and what do you most want to say or communicate with your writing?

This varies from one book to another, but for the most part I write to entertain, not to make any kind of serious point. Honestly, it’s hard enough just to write an entertaining novel without trying to “say” something. I did take some jabs at fundamentalist Christianity in Mercury Falls (leading many to conclude that I’m an atheist, which I find pretty funny), and Mercury Revolts is a not-very-subtle commentary on the modern surveillance state (leading one reader to complain about my “liberal politics,” which I find even funnier).

Usually I err on the side of subtlety, though. I envisioned Disenchanted in part as a satire of the publishing industry, something that absolutely no one seems to have picked up on. In the end, what the reader gets out of the book is out of the author’s control, so it’s mostly futile to try to push some kind of agenda. All you can really do is try to write an engaging novel and hope some truth gets through, one way or another.

What are your concerns, at this point, as a writer? What, if anything, causes you stress?

How many times can I just type the word “money”? Being a novelist is a very up and down business, which makes long-term planning extremely difficult. You’re constantly assessing short-term versus long-term rewards. Should I keep my day job, which gives me a steady income but severely limits the amount of time I have to write? Should I take this advance from a publisher, or should I forgo the short-term gain to make a higher royalty by self-publishing? Should I play it safe by writing a sequel to one of my existing books, or take a risk by writing an original book that could sell far more (or far fewer) copies?

The good news is that I have every reason to believe that in the long-term, I’m going to do just fine (thank God for residuals). But in the meantime, there’s a lot of nail-biting and watching the calendar.

5 Questions On Publishing

You write in Self-Publish Your Novel: Lessons from an Indie Publishing Success Story that after deciding you might be able to make a living as a writer, you knew would need more readers. You then set off on a campaign to find them, the details of which are in the book.

You present, immediately, as a business-minded person—and you even have web development experience, you note in the book. A person might think, “Well, of course someone with a head for business will succeed at self-publishing.” And maybe even, “Of course someone who is something of a natural on social media will sell books.”

What advice would you give self-publishers (or authors published by very small presses) who aren’t very right-brained or promotional-social? Can they succeed?

If you’re just starting out, you should focus 95% of your efforts on making your product the best it can possibly be. If this is your first novel, take your time. Put it down several times for a few weeks at a time and then read it over with a critical eye. Find beta readers who will give you honest feedback. Get an editor and proofreader. And for God’s sake, hire a professional cover designer.

If you can’t afford these people, offer to mow their lawn or do their laundry. You are competing in a very tough business with millions of other writers, many of whom are certified geniuses and who have whole teams of professionals on their side. Don’t put out a lousy product. And don’t forget that’s what your book is: to you it may be your baby, but to the strangers you’re trying to sell it to, it’s a product.

If you can’t afford these people, offer to mow their lawn or do their laundry. You are competing in a very tough business with millions of other writers, many of whom are certified geniuses and who have whole teams of professionals on their side. Don’t put out a lousy product. And don’t forget that’s what your book is: to you it may be your baby, but to the strangers you’re trying to sell it to, it’s a product.

Don’t kid yourself with romantic notions about how much your book is “worth,” or how much demand there is for it. If you’re a first-time novelist no one has heard of, absolutely no one is going to pay six bucks for your book. Writer forums are full of authors no one has heard of who refuse to price their book below $4.99 because of some misguided idea that the price of a book should have something to do with how much effort went into it.

I recently heard a self-published author at a conference saying that she refused to sell digital copies of her books because she was worried about piracy. Meanwhile, literally in the next room over was Cory Doctorow (speaking to a far larger audience), who sells millions of books despite the fact that he makes the digital versions of all his books available for free on his website. That woman wasn’t afraid of piracy. She was afraid of failure. And if you’re not willing to risk failure, you are in the wrong business.

That said, if you’re a good writer, you work really hard to put out a quality product, and you are brutally honest with yourself about the business aspects of writing, there’s no reason you can’t succeed. Eventually. I was fortunate in that I released my first self-published novel, Mercury Falls, when there were relatively few ebooks on the market and (thanks to short-sighted publishers) most of the available books were overpriced. These days it’s a bit harder to get noticed. You can’t just publish a book, price it at 99 cents, and expect it to soar up the charts.

There are lots of things you can do to increase your visibility—blogging, being active on social media sites, doing contests and giveaways, sending copies of your book to reviewers, attending conferences and conventions, running promotions on sites like BookBub, participating in discussions on message boards, contributing to anthologies with other authors, etc.—but none of these are a silver bullet.

As the ebook market becomes more saturated, I’ve increasingly become a proponent of the idea that the best advertisement for your books is another book. The more books you have out, the more visible you are, and the more you look like a “real” author. And believe it or not, with practice you might also become a better writer, which is always helpful when trying to sell books.

If you’ve written one good book, write a sequel, or at least try to stay in the same genre. Keep the first book priced low or even give it away. Your strategy should be to get readers hooked on your writing and keep them coming back for more.

While you do this, work on building your email list. Set up a list using MailChimp (it’s free up to 2,000 email addresses). Put a prominent signup form on your blog, and send people to your blog posts from Facebook, Twitter, and wherever else you have an online presence. Also make sure you include a link to your signup form in the back of your ebooks. Your email list should be the center of your marketing efforts. These are your diehard fans; the ones who will buy every book you publish. Don’t spam your list with garbage (and don’t add people without their consent), but whenever you have a new book out or you’re doing some kind of promotion, email your list.

Some authors depend on Amazon or Goodreads to let readers know when an author they like has a new book out, but it’s a mistake to depend on a third party to drive your sales. Amazon is ultimately in business for itself, and you never know when its algorithms are going to change. Facebook offers a good object lesson on this subject. If you talk to any author who has been on Facebook for more than a year or two, you will probably hear horror stories about how much more difficult it is now to reach fans than it used to be. Don’t be a tenant farmer on someone else’s property. Your email list is your meal ticket.

Above all, keep in mind that being a successful writer is a marathon, not a sprint. If you publish a book, market it like crazy, and then sit there watching helplessly as languishes somewhere around 2 million in the Amazon rankings, don’t despair. Keep writing and keep building your email list. Evaluate your work and your marketing to determine what you did right and what you did wrong and make improvements where you can, but don’t obsess over failure. You can’t fail as long as you’re still moving in the right direction.

Why did you hold a Kickstarter campaign to independently publish City of Sand, and would you recommend others go that route (why or why not)?

I’ve done four Kickstarters for four different books. They’ve all been successful, raising between $3,500 and $5,300. I’m currently running one for two sequels to my humorous epic fantasy, Disenchanted. That one funded in four days, but it’s not too late to pledge if you want to get advance copies or other cool stuff. No, seriously. Go check it out. This interview will still be here when you get back. Here’s a line of tildes so you don’t lose your place:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Back? Good! There are a lot of advantages to doing a Kickstarter for a self-published book. First, you make some money in advance of the book release, instead of having to wait for several weeks after the book comes out. Second, it’s a good way to reach new readers, who can find you by browsing through projects on Kickstarter’s website. Third, it’s a way for dedicated fans to get more involved in the project and support you at a higher level.

I’m fortunate to have a small but very dedicated group of fans who love my work and want to see me succeed, and those people have no problem pledging money to get a signed book, or a poster, or a mention on the book’s acknowledgement page. It’s a fair amount of work to set up a Kickstarter, and how successful you are will depend largely on how big your fan base is and how well connected you are to them, either through your email list or social media connections, but it’s definitely a good way to go for most people.

You self-published Schroedinger’s Gat using Amazon’s independent services (CreateSpace, Amazon Digital). What was that experience like, sales and promotion-wise, compared to having one of Amazon’s traditional model imprints (47North) publish your work?

You self-published Schroedinger’s Gat using Amazon’s independent services (CreateSpace, Amazon Digital). What was that experience like, sales and promotion-wise, compared to having one of Amazon’s traditional model imprints (47North) publish your work?

The tradeoff is pretty simple: if you self-publish, you have more control over the final product and pricing, and you generally make a much higher royalty as a percentage of the net price. But you also have to do your own editing, proofreading, cover design, and marketing—or hire someone to do any or all that stuff for you.

Whether that tradeoff is worth it depends mainly on:

how much of a control freak you are;

how much you like/dislike dealing with the business part of publishing; and

how much you expect your publisher to do for you, particularly in terms of marketing.

Don’t assume you’re going to get tons of marketing/publicity support just because you’ve landed a publisher. Generally, the size of the advance the publisher is offering will give you a pretty good idea how hard they are planning to market the book. As my agent once told me, “If the book fails, you want somebody to get in trouble.” If a publisher is offering you less than $15,000, you’re probably better off walking away.

Your website includes a quote from a Huffington Post article by Laxmi Hariharan, who writes of you, “He likens the league of published authors to an elite night club, with gatekeepers, who decide who gets in and who does not.”

What inspired you to make that comparison, and what is it like (having since been traditionally published) to now be a member of that elite club? That is, do you have a different perspective of it than you once had?

The point of that remark was that self-publishing (and KDP in particular) offered a backdoor into what used to be a very exclusive and highly controlled business. These days, the club doesn’t really exist anymore. There are successful authors and unsuccessful authors. Nobody really cares anymore who is published by whom. I suppose there’s still some cachet to being with one of the better known publishers, but the vast majority of my readers don’t have any idea that some of my books are “self-published” and some are “traditionally published.” Nor should they. It makes no difference to them, as long as they enjoy the book.

How does a self-publishing advocate end up with 47North? I (maybe incorrectly) assume you weren’t looking for a publisher, so that relationship must have had an interesting beginning.

Well, what happened is that I shopped Mercury Falls around to a few agents in 2009, got frustrated with the tepid response, and decided to publish it myself. I was starting to hear stories about independent authors having a lot of success on the Kindle platform, so it seemed like a good time to try my hand at it.

My goal was to sell 1,000 copies of that book, and I ended up selling around 5,000. Then one day I got an email from an editor at AmazonEncore, which was Amazon’s first publishing imprint. They offered to re-publish Mercury Falls as an AmazonEncore title, and since my sales were dropping off at that point, I took the offer. That book went on to sell another 50,000 copies.

As Amazon’s publishing endeavor expanded, my books got moved to 47North, which is their sci-fi/fantasy imprint. I’ve published five more books with them since then. I continue to self-publish books as well, though, so it’s not quite accurate to say I’ve “ended up” with 47North. In fact, I recently started a publishing cooperative with several other authors called Westmarch Publishing. We help each other out with editing, cover design, and all the other tasks involved with publishing a book. We’ve already released 15 titles, and we’ve got a lot more slated for 2015.

I expect to continue publishing independently through Westmarch while continuing to work with traditional publishers on some books, depending on which makes more sense for the book in question. Oh, and did I mention you should check out the Kickstarter for my current Westmarch title?

The post 5 On: Robert Kroese appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Chris Jane.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers