Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 143

September 23, 2015

5 On: Eddie Wright

In this 5 On interview, Eddie Wright discusses artistic collaboration, why he adapted his novella into a graphic novel, marketing straight fiction vs. marketing comics, and more.

Eddie Wright (@eddiewright86) is an author, comic book writer, blogger, and editor. His work has been called “stunningly original,” “authentic,” “bizarre,” and “brilliant.”

You can read his writing in the novella Broken Bulbs, in his comic series Tyranny of the Muse, in BOOM! Studios’ Regular Show comic series, in the upcoming Lake Imago comic series (with Jamaica Dyer), and elsewhere.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: Of the superhero comics you read as a kid, which were you most likely to run to the store for when the new one came out, and what was it about superhero comics that appealed to you as opposed to something like my old favorite, Archie Andrews and his teenybopper bunch?

EDDIE WRIGHT: The Punisher and Batman were my favorites. I’ve always liked the lone-vigilante thing over the superpowered hero or team thing. I like weirdos with troubled minds, and those guys fit the bill.

As a kid, superhero comics appealed to me because they were fun stories about awesome people who could do incredible things. When I was little, I was obsessed with action movies, funny cartoons, horror, and science fiction, and superhero comics could be all those at the same time.

Archie is cool though. I always liked the whole Riverdale gang and read that stuff as well.

What inspires the stories you tell in any form? What gets you excited to write?

I like to explore different ideas and try to find some kind of authentic truth. Regardless of what form the story takes, I try to remain as honest and real as I possibly can. I want stories to be entertaining, but I want them to resonate and communicate something that resonates in me. It’s really about figuring things out for me on the page and hoping people get it.

You said in an interview, “When I realized I could start writing and maybe actually turn it into a career, I wrote a book.” What did you initially envision as your writing future (and what your professional life would look like), and how has reality matched up?

When I decided to publish Broken Bulbs I really don’t know what I envisioned. I’m not sure why I did it or why I thought anybody would read it. But I did, and they did.

When I decided to publish Broken Bulbs I really don’t know what I envisioned. I’m not sure why I did it or why I thought anybody would read it. But I did, and they did.

It’s honestly very strange, now that I think of it. I’ve always wanted to write for a living, and teaching myself how to make it work on the Internet has resulted in some kind of writing career. I write and edit as my day job, and do these weird stories and comics as the side gig.

When I first started this whole thing back in 2008 or so, I was a video editor with aspirations of being a professional writer. I found out about self-publishing and decided to give it a go, which forced me to learn how to do so much in service of the book. How do I design a cover? How do I put together pages? How do I design a website? How do I manage and edit a blog? How do I promote myself? How do I network with other creative people?

I had to learn it all. If I hadn’t jumped in blindly, I probably would still be working in video and not be a pro writer. Being clueless caused everything, and with this whole comics thing, I’m sticking with that strategy. It seems to be working out so far.

Tyranny of the Muse was created when you thought your novella, Broken Bulbs, would make a good comic book. What in text-on-the-page fiction reveals itself to be something meant for graphic art and comparatively limited text?

I’ve always been a pretty visual writer, and when I write prose I try to create a feeling that evokes some kind of sensory connection. I want readers to feel like they’re standing in the main character’s shoes and feeling his world. I want them to experience it; I want them to smell it.

But at the same time, I think overly descriptive writing is boring. So I often describe things in a way so the reader can feel how a character feels about those things or considers them, rather than explain what color the wall is and what pattern is on the carpet.

With comics, the art can create the same feeling, but readers can actually see it. My comic scripts are very similar to my prose in that I don’t overly describe anything. I let the characters’ feelings and dialogue dictate the visuals.

Collaborating with an artist on a story seems, in theory, like a lot of fun. Then again, it could also turn into a deeply complicated, potentially competitive relationship, like the one between Eloise creator Kay Thompson and illustrator Hilary Knight. What has been your experience working with illustrators? Are the relationships typically easy, or are struggles to be expected?

Collaborating is interesting. It’s a relationship like any other. So far, I’ve been lucky with the artists I’ve worked with. They seem into what they’re drawing and understand my intentions. Struggles are definitely to be expected because you’ve got more than one human being in the mix. When two or more people are involved in anything, there’s going to be some friction. But the friction isn’t really contentious.

It’s creative work. It’s how I think great things are made. There’s discussion, disagreement, and conversation. Never fighting or pettiness. I’m sure people have gone through that, but I haven’t. I’m pretty easygoing when it comes to collaborating. I like it. And I feel like as long as I’ve done my job communicating my intentions clearly—which really is a writer’s job, period—then we’re in good shape.

5 on Publishing

You didn’t make it a priority to pitch Tyranny of the Muse to editors or publishers. Why?

I self-published Broken Bulbs, so I figured why the hell not just do it? I grew up playing in punk bands and going to little punk shows in Elks Lodges and firehouses where a bunch of teenagers performed music and sold tapes, CDs, T-shirts, stickers, and all that. None of those kids asked for permission before doing it. They just did it. That type of thinking is in my blood. It’s what I know. Just put it out and see what happens.

I self-published Broken Bulbs, so I figured why the hell not just do it? I grew up playing in punk bands and going to little punk shows in Elks Lodges and firehouses where a bunch of teenagers performed music and sold tapes, CDs, T-shirts, stickers, and all that. None of those kids asked for permission before doing it. They just did it. That type of thinking is in my blood. It’s what I know. Just put it out and see what happens.

But, as my writing career takes shape, working with publishers and editors is making more sense for me. I’ve always been open to working with publishers, and I have no problem with that sort of thing, I just didn’t consider it at the start, and I don’t let it stop me from trying. So, I have ended up working with the publisher Alternative Comics to release Tyranny of the Muse both digitally and in print. But that wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t established the series at first. It’s really about taking the leap.

There’s marketing/selling your fiction vs. marketing/selling comic books or graphic novels. Are the processes and avenues very different, and is one easier or harder than the other?

Marketing and selling fiction vs. comics is definitely different because there is a world and community around comics that doesn’t exist in fiction for me.

There are definitely pockets of shared interests in fiction, but not like there are in comics. There’s a built-in audience for certain kinds of comics and a world to reach out to. In fiction, you really have to find your own way and build your own thing, especially if your work doesn’t neatly fall into a specific genre.

I imagine if you write standard horror or science fiction or fantasy, it’s different—but if you write some weird amalgam of the three, you’re a tough sell.

How beneficial, or even critical, is it from a sales standpoint to attend conferences and expos?

For me, it’s been very beneficial to attend comic shows. It’s great to be able to pitch the book to readers in person, see their reactions, and sell it to them. It makes the whole thing feel more real.

When you’re trying to do it all online, the only way you can tell if anybody is interested in your stuff is if they “like” or comment, or something like that. But in person, you can have a conversation about it. It’s very good for the morale, especially if someone tells you that they already know about your stuff because they saw or read it online. That feels good.

Outside of conferences and expos, what do you actively do to promote your work, and what have you found to be most effective?

I do the usual stuff: Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, my own website, and an email mailing list. I try to promote myself without being obnoxious. This is the hardest part of it all, I think. It can feel like you’re just screaming at nothing a lot of the time, and often you are. But being authentic is the best way to approach this side of the life. Set aside some time and poke around on Twitter. Follow people who are doing what you do, talk to them, share their stuff, be sincere. You’ll find some traction that way.

Also, building a substantial email list is a huge benefit. I think that’s probably the best way to market yourself online because you have a captive audience that isn’t bound by the weird algorithms of some social media company.

In your history of trying to sell your work, what got your hopes up or made you confident—”This will be the thing! This will do it!”—only to send you crashing down? How did you handle it initially and what did you learn from it?

I’m in a constant state of teetering on the edge of crashing down all the time. But somehow I keep doing it. I’m probably the most negative optimist I know. Everything feels like, “This will be the thing! This will do it!” and nothing feels like it works to the extent you think it will.

The important part is stepping back and taking a look at the successes, even the minor ones, which, at this level, they all are. People buy my stuff. People have read it. People like it. Publishers are interested in words I write. People I don’t know have looked at things I made up and thought about them and considered them real and legitimate and connected to them and felt something.

The life of a creative person is a life of constant internal struggles that I don’t think will ever go away despite whatever level of “success” you achieve. It’s all a battle between what you want to do, what you have to do, what you can do, what you just did, and how you can do it better—all with a substantial dusting of “how the fuck am I going to pay the rent?” It’s fun.

Thank you, Eddie.

September 22, 2015

An Interview with Richard Nash: The Future of Publishing

Note from Jane: I conducted this phone interview with publishing industry leader Richard Nash in 2014; it originally appeared in Scratch magazine. For those interested, I’ve started another publication for writers, The Hot Sheet.

When I hear Richard Nash speak, I always remember it long after: the way everyone in the audience is completely alert from beginning to end, how his energy fills the room and crackles, and the way he gleefully uses a series of F-bombs to emphasize key points. After listening to Nash, I immediately feel smarter as well as more confident that publishing will be all right as long as he’s somehow in it.

Nash is the former publisher of Soft Skull Press, for which he was awarded the Miriam Bass Award for Creativity in Independent Publishing by the Association of American Publishers in 2005. Over the better part of a decade, he shepherded books onto bestseller lists across the globe, and Utne Reader put him on its 2009 list of fifty visionaries changing the world. It’s hard to attend any publishing industry event without seeing him on the agenda. Former Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson called Nash’s “Publishing 3.0” talk “the best I have ever seen.”

While I was at the Virginia Quarterly Review, assisting with the planning of an entire issue focused on the business of publishing, I immediately suggested Nash for the cover story. I wanted to challenge him to turn one of his famous talks into essay form. To my delight, he agreed, with the slight warning that it might be akin to transcribing a “fever dream.” In Spring 2013, VQR published Nash’s long-form essay on how the book-publishing industry must evolve in the digital era, “What Is the Business of Literature?” It became the most popular article at the VQR website for the year, and was later translated into several languages.

Over the last several years, since his departure from Soft Skull, Nash has worked at a series of publishing startups, including Cursor, Small Demons, and Byliner. Last year, he transitioned to being a full-time consultant (at about the same time I did!).

Jane Friedman: So how is your transition going to full-time consultant?

Richard Nash: I have to find out what my business model is. Basically, it’s a freemium business model. [Laughs.] That’s what I have: I am a one-man freemium operation. I now have four or five clients that pay me real money by the hour or day, and then about ten or twelve startups that pay me in equity—you know, Monopoly money. And then I do a bunch of favors. Not probably dissimilar from your business model.

Yes, that well describes where I’ve ended up myself.

I could turn around and have another startup in six months, but I’m setting the threshold higher than I once might have. You really have to go through a few of these startups to grasp what it means that most startups fail. You always think your startup is the special snowflake. [Laughs.] Oh, look at all those snowflakes falling on the ground and falling in some undifferentiated mush and slush. My special snowflake will appear under the magnifying glass of some Nobel Prize–winning physicist! And everyone will be awestruck and bank-account-emptying in response.

You usually need [to experience] more than one startup to realize that doesn’t happen. So I’m just trying to be more pragmatic. The reality is that a single startup is one Powerball ticket, whereas what I’m trying to do with advising a bunch of early-stage startups is get ten Pick 4s. [Laughs.] And then, with more mature companies, pay the bloody rent.

I read a write-up of your talk at The Next Chapter in Stockholm , where you were invited to talk about the future of the book. I’d like to probe a little into something you said, where you discussed how the book has been limited in its ability to turn culture and creativity into money, and how important that is for us to see. This idea of thinking beyond the book when it comes to business and income—could you elaborate on that?

I don’t mean multimedia. There’s a tendency to say, “Oh, here’s all this new technology, which means the book is becoming something else.” The book isn’t becoming something else any more than plays became something else when film came along. Today no one runs around saying publishers should start Hollywood studios and the book is over, like here’s our Film-O-Book! [Laughs.] The Book-O-Vision.

Technology will continue to permit new modes of storytelling, but it also permits new modes of cultural engagement. For a couple of decades now, perhaps longer, the main thing that management consultants and poets had in common is that they made far more money giving a talk for a class than they did in royalties from their books. In both cases, the book served as a verification, validation, a hurdle. The book is sort of like a marathon—we venerate the person who finished it. So the book is useful in that regard, and you can sell it at events and increase the revenue that event creates—but at that point it is functioning more like a T-shirt after a concert, a souvenir of the experience of having encountered the famous poet or the iconic business figure.

I’m less interested right now in exploding the book, or what kinds of book-y container-ish things writers can create, than in understanding their whole mode of cultural engagement more holistically. And looking at it from a freemium standpoint.

You’re not suggesting that writers give away their work, though?

Certain activities you engage in, you may do for free, and certain activities you engage in are going to be very, very expensive. It’s free to walk into the Prada store at Broadway and Prince, but it is extremely expensive to buy a dress. It is less expensive to buy cufflinks or a blouse. It tends to be that most people who go in there buy nothing—which is also true of the Apple store.

What are some examples of more expensive activities writers could engage in?

Work with your local restaurant and do four events a year where you converse with ten people who are paying $150 to have a dinner party conversation with you.

Take the novelist and poet Jim Harrison. Harrison has had a fairly steady hardcover and paperback sales track record over the last twenty to thirty years. I know Grove is always trying to figure out, “How are we going to sell more Jim Harrison copies?” And the answer is: it is really fucking hard to bend a demand curve for somebody who’s been in the culture for thirty years. [You can’t expect] some deus ex machina to descend [and move] the point along the demand curve for Jim Harrison-ness—where there are twenty thousand people who want to engage for fifteen dollars—to where there are suddenly forty-thousand people who want to engage.

But the thing is, there are all kinds of other places on the demand curve that are completely underutilized. So in the case of Harrison, I remember several years ago Googling him, and the second entry was a Wine Spectator article, which I read and I discovered that he is an epic gourmand. He has arranged these four-day bacchanalian orgies of food and wine in Florida in the winter with a bunch of food cronies.

If Jim Harrison picked a bottle of wine for you to drink while reading the beginning of his next book, you could get one of those wooden unvarnished boxes, stick the signed hardcover of the book and a little explanatory note from Jim in there, and sell each one of them for three hundred dollars, easy.

You can also have a ninety-nine-cent download, and you’re going to get more people to read him. Are you going to cannibalize a little bit of paperback sale? I don’t think so at all, actually. Even if [you do], from a revenue standpoint and from a readership standpoint, both numbers have gone way up.

I’ve been trying to advocate for this with publishers for years, but basically they just don’t seem able to handle it—not at scale. On an ad-hoc basis, you’ll see a few publishers trying a few things.

I wonder if you’ve noticed Coffee House Press and some of the things they’ve been doing? They did a blog post for VQR this spring where they discussed their switch from “we publish books” to “we connect writers and readers and produce literary experiences,” and so they’re doing things like putting writers in residency at libraries and museums.

Philosophically, that’s exactly what I’ve been preaching. Practically, that’s definitely one of the things. I think partnering is critical, because there’s only so much time in the day. And there’s only so much expertise that you can have in-house. And nonprofits to some degree have always been doing this. They’re the classic example of tiered participation.

Let’s talk about the issue of a book’s value and pricing—not necessarily ebooks and the Hachette-Amazon dispute (we’ll get to that later), but what you call the commodification of the book. You’ve had a lot to say on this topic that I think authors should know about.

All the research that’s been done in the last twenty, thirty, or forty years around decision theory and behavioral economics has exemplified that nobody knows what anything is worth. So everything is about signaling and manufacturing the appearance of value. But the book business does a terrible fucking job of doing it.

We have all these weird, different, hybrid, and crazy fruits—Neil Gaiman fruit and John Ashbery fruit and Philip Roth fruit. And what do we do? We put them all in this one little rectangular square sort of thing and charge almost identical prices for it, begging people to do price comparison, because what else do they have? You don’t know what’s inside the book in many cases.

So part of why I’m saying “go beyond the book,” is that there’s a whole universe of ways you can engage with your culture. Some of those can and should be monetized, and anyone who thinks, “Oh, well, gosh, how tawdry to charge for that,” I’m like, have you looked at the book? Everyone’s like, “The book is getting commodified by Amazon.” No, it fucking isn’t!

If the human race ever created a commodity, it was the fucking book. It was the first time we mass-produced facsimiles. The fundamental business model of the book as a physical object is identical to Corn Flakes and tires and two-by-fours and sneakers. The entire industry has the shape of a manufacturing industry. And that problem was solved up until the last twenty years by simply not creating that many products.

Today, it’s a miracle anybody is making money with a quarter of a million SKUs going into retailers every year. The book has become a not necessarily good way to capture the value that you create by telling your stories. And so authors need to find other modes of engagement, and especially those modes of engagement that are uncopyable, because the value of copies is just declining.

It reminds me of Kevin Kelly’s post, this was many years ago—

“1,000 True Fans,” right?

That too, but he also talks about all of the things that are better than free , like immediacy, personalization, authenticity. So he talks about all these ways to add value to something.

Absolutely.

It’s definitely the area where I see the most pushback from writers—like this is not what they signed up for. They just want to write.

And some people would say, “I’m shy.” And it’s sort of like, not all this stuff has to be public. There are all sorts of ways—you could create personalized postcards that you mail people.

I’m not sure all writers are capable of these things.

For people who are like, “I don’t know how to do that,” the answer is “You gotta fucking figure it out.” Years ago, you didn’t know how to write a poem. Ten years ago you didn’t know how to write a novel. And you went to a lot of effort to try and figure that out, you did a lot of research, so that’s what you gotta do in these situations.

No one wants to just sit and write! Not even Beckett wanted to just sit and write. Seriously. Beckett acknowledged that one of the reasons he did those TV plays for German public TV stations in the 1970s was to get out of the fucking house. If Beckett can’t abide just sitting down and writing, then any writer can find emotional and cultural stimulation by engaging with society. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Why is it that you want to write? Because you have something you want to say on some level. On some level you want to be loved by some percentage of the world. How about you get out there into the world and feel it? Do chefs say “I just want to be left alone and cook”?

I find that writers can lose all creativity and imagination as they think through how they’re going to charge for premium experiences or make money aside from selling books. They have a narrow idea of what engaging with readers or society looks like.

I blame publishing. I feel like we’re in this Stockholm syndrome. Publishers really were the manufacturing business, and the last thing you want is a couple of the guys in the assembly line running around and talking to the retailers and fucking things up. So writers were typically told, “Look, don’t worry about all that crazy stuff in the sausage factory, we’ve got it all taken care of.” Writers were infantilized and told, “Go do that weird little thing that you do.” So these false narratives evolved around the writer.

Could you provide some words of wisdom or calm regarding the Amazon-Hachette dispute? You probably noticed that Authors United released a new letter this morning, directed at the Amazon board members. It felt futile.

It is futile! Everything I have described is the reason authors shouldn’t be worried about this Amazon business. Every other dimension of the revenue-generating activities an author can do, that we have discussed, Amazon is incapable of helping with.

Publishers are completely foolish to be taking Amazon on regarding price. Price is existential for Amazon; it’s the only thing they know how to do—make things cheaper and more convenient. Trying to tell them “Oh, stop making them cheap and convenient” is like telling the scorpion not to sting you while crossing the river. It’s just what it does.

Amazon should be left to do what it does, which is be the Walmart. Focus your efforts instead on high-value experiences rather than on commoditized products.

It’s refreshing to hear you say that.

You don’t persuade people to pay more in a price-driven environment. And bookstores traditionally have been price-driven environments. Amazon is a price-driven environment because Amazon fucking learned from the book business!

Again, it’s this fantasy we’ve had that we’re in the culture business, when we [publishers] are in fact the structure of a manufacturing business. And Amazon came in. What was attractive to Bezos was how uniform our pricing and packaging was. Here was a market with a large but not insane number of suppliers; a large number of SKUs, all of which were virtually identical from a physical standpoint; and a distributed warehousing system. He wanted to get into e-commerce in a big way, and the easiest, the most commoditized business he could go for was the fucking publishing business.

So it’s just insane to be claiming that he’s commoditizing us when we were the commodity business that he just took to its logical conclusion. Trying to walk him backward, and trying to walk the industry back into the 1980s, is ludicrous when we have all these opportunities to walk our business forward into the twenty-first century, using Bezos as fucking UPS. Let him be the guy responsible for shipping $15 books around the country, and let him be the guy with the $9.99 download.

So what’s ahead, assuming we can stop moving the industry backward?

The stuff I’ve been talking about until now I have immense confidence about because I’m not the only one saying this stuff. It’s basically empirical; it’s out there. Now, I have no clue what it means to go on to the next step. All I know is that it feels really important.

The two analogies I’m able to come up with are health and education. What they have in common with long-form reading is a cost-benefit profile that skews the costs toward the short term and the benefits toward the long term. Most of the value of reading long-form narrative is that stuff tends to have a fairly high cost in the short term, as far as the amount of time taken to engage with it, but tends to have a significant amount of value over the long term, in terms of how it helps our understanding of emotion, personality, and character; how we’re able to follow extended arguments; how we’re able to move backward and forward across time.

We’ve seen a lot in the area of health that is being called “the quantified self.” This comes out of a lot of research around feedback loops—that when the brain is given feedback it is better able to make better choices. What the quantified self says is: you don’t even have to be harangued into sleeping more. If you have a device that measures how you sleep each night, the mere fact of being confronted with the actual evidence of what happened last night will change your behavior. It’s these nudges. One of the classic ways of giving nudges is just giving people information about what they’re doing.

So how do we easily acquire information about how we read?

Obviously Amazon is a bit of an impediment to that, but the reality is that no one’s going to just be interested in an app that only tells them about book reading. They’ll be interested in apps that tell them about all their text reading, and that includes the web. Over a period of time, we will find ways to allow our reading to be trackable.

Over the long run, this approach to services—I feel like that’s where the money is going to be. It’s very hard to make money at selling digital things, but it is much easier to make money out of renting digital services, and I suspect that the power of digital is going to be much more around the ability to get people to read more and have really cool ways of monitoring your reading that you’re willing to pay $2.99 a month for. And most of the value being created from stories is going to be through physical objects that are up-priced and via experiences that will be priced all over the map.

Some of the pushback in the area of quantified self has to do with privacy, so the trick is to focus on the user owning the information. Most of the conversation that has gone on with reading has focused on giving that data to the producers—that the producers will write better books if they know how people are reading them. Maybe, I haven’t seen evidence of that, maybe a little bit of evidence in the narrow world of pedagogy. I am deeply skeptical that that data is going to be useful around anything other than the most practical how-to areas [of the book market]. The value in data around reading is for the reader, not the writer.

September 21, 2015

Truth-Telling and Platform-Building

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by Lisa Bennett (@lisapbennett).

When I finally came around to learning something about the business of platform-building, I soon discovered that there is a mountain of advice out there.

But one point, above all, seemed clear: If you want to attract an audience to your site, you need to offer something people want. Writing advice. Financial advice. Relationship advice. Parenting advice. Leadership advice. Cooking advice.

I’ve never imagined myself qualified to give other people advice—or even particularly interested in it. I just happen to be someone who finds the process of discovery more interesting than how-to tips. But I fell into it all the same.

And the result, for me, was not good.

In grief about the loss of my dear mother, saddened by the demise of a significant relationship, worried about how climate change will affect my children and others’, I started thinking about how to channel what was present for me into something that would be useful to people. And that led to a tagline about how people rise to challenges big and small.

Of course, this was not entirely false. I am fascinated with what loss teaches us; how we grow from facing the reality that things often don’t go our way; and how many seemingly ordinary people do rise in extraordinary ways to the challenges they face in life.

But when I was honest with myself, the truth was I did not feel like a person who should be trying to dole out insights and inspiration to other people.

I am still in grief, I am still sad, I am still afraid, and I am often confused.

Attempting to offer insights to others from this place, even if I was basing it on other people, seemed ridiculous. It also seemed like only half the story: an offering of the light without the dark in life. In a word, it felt fake.

That, I realized, was why I was experiencing writer’s block. Why I was starting and stopping. Going in circles. Feeling unable to push the “publish” button.

And then I realized, or more likely rediscovered, that it was OK to let the idea that I should put things in a pretty box go. The writing I did from those dark but deeply human places of grief, sadness, and fear was actually the writing that most interested me. It seemed most real, most meaningful—and contrary to what I might have expected, not depressing or self-absorbed. It usually went somewhere. It tended to be healing in itself.

So I have decided to let myself out of my self-imposed prison. To give myself permission to write just what is—knowing that this is the plane on which many of us would rather connect anyway.

This is not to say I think writers can disregard the realities of publishing and audience-building in today’s platform-crazy world. But it is to say one must not let it overwhelm the reason one wishes to write in the first place, which for me is the desire to explore, and the hope to connect.

September 17, 2015

An Interview With Bo Sacks: The Magazine Industry and the Future of Publishing

Note from Jane: I conducted this sit-down interview with magazine industry veteran Bo Sacks in spring 2014; it originally appeared in Scratch magazine. For those interested, I’ve started another publication for writers, The Hot Sheet.

When I started my first job in magazine publishing, in 2001, my boss gave me a set of instructions for my first day. One of the items was “Subscribe to the Bo Sacks e-newsletter.” I obeyed, and I started receiving three reads in my email inbox every weekday morning about news, trends, and upheaval in the publishing industry. Before long, I felt like an insider, and whenever I hired someone, I told her to subscribe too.

Bo Sacks has been working in the publishing industry since 1970, when he founded a weekly newspaper with a group of friends. He was also one of the founders of High Times magazine, a groundbreaking magazine about a law-breaking topic: marijuana. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Sacks led manufacturing and production at a wide range of magazines and publishers, including McCall’s, TIME, New York Times Magazine Group, and Ziff Davis. Today, he focuses on private consulting and his email newsletter, which reaches about 16,000 people.

Although the bulk of his career has focused on print manufacturing, anyone who reads or meets Bo Sacks quickly learns that he sees a publishing future filled with opportunity, not disaster. Still, he is not a Pollyanna. When Bo first met my partner, Mark, whose job for the last 15 years has been facilitating the production of print books, Bo asked him right away, “Do you expect to retire from that job?” Mark said no. To which Bo responded with another question: What was Mark doing to become employable in the future, when there’s no longer a market for his skill set? Mark didn’t have an answer. Bo said, “You need to subscribe to my newsletter.”

When I relocated to Charlottesville, Virginia, and discovered that I lived in the same town as Bo, I hoped to find a good excuse to email him and introduce myself. I eventually did while working on a freelance piece for Writer’s Digest. Bo immediately invited me out for coffee. A few months later, when I asked if he would sit down for this interview, he agreed and added that we should make an evening of it. So my partner and I had dinner with Bo and his wife, Carol, at their home. Carol also has a long career in magazine production, and Bo refers to her as his CFO. They have a room devoted to their wine collection, and walls covered with built-in bookshelves. After the dishes were cleared, Bo and I lingered at the dining room table (drinks still flowing) for our interview, while our partners ventured elsewhere to chat.

Jane Friedman: How did you end up starting a newspaper as your first job?

Bo Sacks: I was sitting in Syracuse, New York, with two journalism students—and this is immediately after the Kent students got shot. We were sitting around wondering what we should do, and much to my surprise, one of them said, “Let’s start a newspaper.”

How old were you?

Nineteen. None us knew anything. We started the Express, a 50,000-weekly-circulation tabloid that went to every college in Nassau and Suffolk counties. We learned as we went.

This is when I found out that there are alcoholics even in the business world. Our schedule was to distribute Thursdays, so we took our mechanical boards to the printer at 6:00 a.m. Thursday. I’m 19 years old, I’m sitting there with my printer, and he reaches into his desk drawer, pulls out a bottle of Dewar’s and wax paper cups, and we start to drink. I didn’t know this is not how you do business—I had no idea. This tradition went on for a year and a half.

How did you get funding for the Express ?

Self-funded, $500 each. $1,500 started the enterprise. We bartered for everything. Each partner made $25 per week. We had 50 members. It was an extraordinary, dedicated staff who worked for nothing, for the joy of being part of the publication—anti-war, pro-pot, very liberal. Very humorous.

I would hit ten bars a night to sell advertising. And bartenders aren’t stupid. They say, “Hmm, very interesting, come in the back room.” They’d pour me a drink, we’d negotiate a deal, and I’d go off to the next bar. That experience served me well when I got to big publishing in the late 1970s, early ’80s. Your senior managers almost always got liquid lunches. And so when I got to McCall’s, I guess I was 27.

That’s young.

I was director of manufacturing years ahead of anybody in that job.

Was a woman able to play that game?

In the early days, women weren’t production managers, but at about that time, they started to make their way in. They were always paid less than men were paid.

My boss had a major impact—there was the Association of Publication Production Managers, and they had a golf outing every year where a girl jumped out of a big cake. My boss was the one who said no. And it changed everything. The old-timers were really put out and upset, but he was president of the organization at the time, and he made it stick. And they’ve never had a girl out of the cake since then.

But it was still a man’s world, and the women got angry and left the association and started their own—Women in Production, in New York City. [My wife] Carol was an early president of Women in Production. They grew to be a robust, excellent organization that included men. They held the best event of the year, the Luminaire Awards at the Waldorf Astoria. It was the most prestigious award for production professionals to get in New York City. Later on, Women in Production merged with the Association of Publication Production Managers, so everybody came back together.

What was your path to High Times?

After the Express folded, I went out to Tucson, AZ, to start another newspaper with a partner, the Arizona Mountain Newsreel, which lasted for about ten years, but it couldn’t support me and my partner. So I came back to New York City, and me and a few other fellows started High Times. It was such a controversial magazine that we had to start our own distribution network. Nobody would carry it back then.

How is it possible to do your own distribution?

We called it the Alternative Distribution Network, which was record stores, hairdressers, and odd retail outlets. We were doing massive volume. In all the time that I was there—I don’t know what their sales are now—I don’t think we sold any less than 80 percent of what we distributed to newsstands, which was a staggering accomplishment. [Newsstand sales today average about 20 to 30 percent of what’s distributed.]

Did you face any legal problems?

No. We believed every now and then there was an undercover cop in the mailroom, but at that time there were no more drugs in our office than at Chase Manhattan Bank. Everybody had his own little stash, but there was never any bulk in the office. All of the photographs—which were real—were photographed elsewhere. [The centerfold of High Times typically features a picture of cannabis.]

Bo Sacks with Cheech and Chong at the Friar’s Club after shooting the High Times cover

You were there for quite a while, from 1974 to 1980.

Everything I know uses that experience as a foundation. It’s fascinating to me that when we started High Times, we used a linotype [hot lead] to set type. But we struggled with meeting schedules due to many things, including the nature of our product. So, as a production person responsible for meeting schedules, I had to come up with solutions. So I got a Compugraphic cold type machine. I was the first kid on my block to have one. By today’s standards it was primitive, but it was computerized typesetting nonetheless.

So High Times was technologically innovative?

Extremely, in every way, from distribution to manufacturing. We were also the first people I know to own a fax machine, although in those days it wasn’t called a fax machine, it was called a Qwip. You had to take a chemically treated piece of paper and wrap it around a drum to receive, and you had to call the person and say, “Okay, send now!” and you put your phone on the cradle and the thing would actually burn an image on the drum. To save time, we would Qwip our paginations over to QuadGraphics, the High Times printer then and now.

So your beginnings as a publishing futurist—someone who is thinking progressively about the industry and pointing out how it’s going to evolve—that might be said to have started at the High Times ?

I have the natural personality to think ahead because I was a Star Trek fan, a science fiction fan. That leads you, by the very nature of those things, to be an alternative thinker. That clearly parlayed into manufacturing magazines. “This is how we do it, but why couldn’t we do it a different way?” In every way that I could streamline the process by using technology, I would. And that worked in every step of my career.

I know you have a really interesting story about starting your newsletter—how it started with AOL.

I was working for Ziff Davis, and they had me coordinate with AOL to insert diskettes into magazines; and not only on-sert [attaching to the outside of the magazine], but insert into bound magazines—extremely difficult since plastic diskettes break easily. After the success of the inserting and on-serting, AOL gave me an account. This was about 1988 or ’89, and I was chagrined, stunned, stupefied by sending words over the phone [via dial-up modem].

I’m a magazine guy. I know all about putting words on paper. But to send words through the phone seemed very near like magic. But I had this concept, this theory, that if I understood how to send words over the phone, I’d have an advantage over other production managers who didn’t know how to do that. So that is the only reason I started my newsletter.

There was no World Wide Web, but there were FTP sites like Gopher, and I would find white papers on manufacturing of magazines and forward them to my only other friend who had an email account at that time. He worked for Time Inc., and he had been my college roommate, and we would chat about it. So the newsletter was just me and my college roommate, and then another Time Inc. person, and then there were three, then four, and five. And it mushroomed.

Hardly anyone I know has the kind of focus and dedication it takes to do a newsletter for 20 years. Why have you kept up with it for so long?

I always felt the knowledge and the process [of doing the newsletter] would make me a valuable employee. In those days, I never for a second thought I would be self-employed.

And every night, as you know, the newsletter goes out like religion. There are only two times in the last 20 years it didn’t come out. Once, when we were vacationing in Australia, I used the AOL 800 number but couldn’t get a connection. The other time was on my honeymoon, and it just seemed prudent not to work on my honeymoon. I think that was a success.

Recently on Twitter, I saw a journalism student create a guest-speaker bingo card with phrases that come up a bit too frequently in journalism talks. One of the spaces was labeled with the quote “It’s an exciting time to be a journalist.” Do you think that’s an overused phrase?

Is it a catchphrase? Yes. Is it the truth? Absolutely. It is the most exciting time in publishing’s history. We’ve had a mundane experience up until 20 years ago. Twenty years ago, you did the exact same thing that your boss did. And your boss did the exact same thing that his boss did. There was very little change in our industry.

I like to say the same thing with a different phrase, equally ridiculous: “This is the next golden age of publishing.” I believe that to the fullest. More people read now than ever before. There are billions of people online reading now, and in the next five years, there’ll be billions more online and reading. If we’re all smart, that’s an opportunity of unprecedented order.

Now that everyone can communicate, they will communicate, so that creates a lot of competition, a lot of noise. Does that seem like the challenge?

Print used to be the least expensive, easiest way to reach a mass audience. It was easy to print, and many people did. And there was lots of junk printed.

Now everybody can be online, but at the end of the day, it’s only quality that will achieve a steady revenue stream. And that’s what seems to be happening right now. We’re not done, but quality writing is rising to the top.

Of course, that leaves out my waiter theory. I believe that the great writers are still waiting tables because they haven’t had the ability to be discovered. Just like the greatest actors are still waiting tables. They didn’t get that lucky break. But that has nothing to do with technology.

Discoverability is a buzzword right now in book publishing: How people discover things to read as bookstores close. Do you think that’s as big of an issue as it’s being made out to be?

It’s as big of an issue as it ever was. There have been many titles—and maybe great ones—that just sat on the shelf, and the right people didn’t get the opportunity to read them and promote them.

So you don’t think it’s a bigger problem now than it was before?

I think it’s an identical problem. The way you get discovered is by luck or fate or who you know, or by the dollar volume that you have, or all three. Or, something is so unique, it just goes viral.

If you walk into a bookshop with a hundred thousand titles, you have a discoverability problem. You can scan a shelf and clearly find one or two things you want, but in scanning that shelf, you missed the hundred other shelves. So now [with digital reading] we’re talking about that, but multiplied. It’s the same problem. Some will get found and cherished and passed on. And others won’t.

There’s all this conversation about print versus digital in publishing. How much is that a distraction?

It’s a terrible distraction. Everything is as it was; only the substrate has changed. And I believe the substrate is irrelevant to the message. We as publishers are agnostic or should be agnostic to the substrate. We just want to sell you good words. I’m indifferent to how you choose to read those words. And that’s what’s happening, despite our fears and worries. Reading is not going to go away. And we should be respectful of the individual’s right to read on whatever substrate she wants.

I’ve heard you say before that print is going to be more of a luxury.

It has to be, because it’s such an expensive process and increasingly will be so. It’ll be less expensive to ship digitally, but not because it’s free—it’s not free. There are servers, there are computers, there is all kinds of infrastructure—it’s a misnomer to think that digital is free. It’s not. But at the end of the day it’s less expensive than printing. And so in order to print you need to be willing to pay the price of printing, and that means that’s what’s left in print has to be considered a luxury item.

Here’s a question I hear a lot: What’s the future of literary magazines? Many are general interest, they can be hard to tell apart, they don’t necessarily have a strong brand. People might not be able to tell the Kenyon Review from the Ontario Review from the Paris Review from the Georgia Review —

One of them that you just mentioned is famous. And the others less so.

Correct. The Paris Review .

And that’s a product of branding. So what can we learn from that lesson? That the way to succeed as a literary journal is to develop a recognizable brand, and that’s not different than any other form of publishing. The key to success is to develop a recognizable, trusted brand. If you can do that, that’s three-fourths of the battle.

This is difficult for the literary community. They’re, like, “Don’t say the word brand . This is art .”

They have a choice. They can be gifted into their existence by grants. Or they can make it in the hard, cruel commercial world of business. If you want to make it in the business world without relying on grant money, you have to run a brand. I think of it as a noble endeavor—saying, “my journal is great and worthy of success. And here’s why. Because it has X, Y, and Z. We deserve to succeed.”

What worries me is that, as someone who has religiously read the New Yorker since college (and I still do), I’m getting further and further behind, and I’ve dropped all my other subscriptions— Harper’s, Atlantic, New Republic, Entertainment Weekly, Wired —slowly, over the last decade. And I notice that my time is getting sucked up in a lot of other reading. It’s not necessarily that I’m reading less, but that my choices are very different. I’m also consuming a lot of TV. You’ve probably seen the trend articles proclaiming “This is the Golden Age of TV.”

Did you see the David Carr article [about all of his TV watching]?

Exactly!

Wasn’t that amazing? His quote about magazines—I’m watching TV and all these magazines are stacking up and I don’t read them.

Yes, so this is my concern.

You said that you’re reading just as much, but you’re just not reading the things you used to read. So that doesn’t make your brain any smaller, and you’re not spending less time stimulating your mind.

I guess I’m concerned for those publications that need reader commitment to survive. I’m not committed to publications any more. I’m committed to this last one, but not to paying money to more than that one. I’ll read other magazines online if the content is free.

I would suggest that you will read anything that’s worthy of you reading it. You used to think the Atlantic was worthy of your money and reading, but you’re spending your time somewhere else because you’ve found worthy reading elsewhere.

If you do not have excellence, you will not survive in print. There’s plenty of indifferent writing on the web—it’s free entry, and it doesn’t matter. But quality will out there, too. Really well-written, well-thought-out editorial will be the revenue stream. You must have such worthiness that people give you money when they don’t have to, since they can get entertained elsewhere for free.

We haven’t touched on the role of advertising in all of this—the other major source of revenue aside from subscriptions. Magazine ad revenue is fading.

It’s not fading; it’s changing. It’s fading from the magazine universe, but marketing is bigger than it’s ever been. Those [ad] dollars that were spent in publications are not not being spent. They’re being used elsewhere. And delivering more of what advertisers have always wanted, which is a direct, one-to-one relationship with consumers.

What do you think about native advertising? [Native advertising is when a publication is paid by an advertiser to write and run a story that looks like editorial content. Sometimes it’s referred to as sponsored content.]

It’s increasingly successful. I find it a despicable practice. I think it’s a path to dupe the common reader. I really believe that, over a period of time, the public will wise up to what’s being done and there’ll be a backlash against those publications that do it, including the New York Times.

Do you find it more acceptable if it’s transparent and clearly marked?

I have nothing against something that says at the top, “This is an advertorial.” Native advertising is nothing more than an advertorial—we have now coined a more palatable phrase for an old practice. The bottom line is, publications are desperate for revenue, and desperate people do desperate things. This is a desperate move on the part of publishers to recapture the revenue that was once theirs. It’s not sustainable. And if it is sustainable, it’s a black mark on all publishers.

Of the magazines that are operating in print, digital, or both, are there a few you can mention that you think have a long life ahead of them?

August Home [publisher of special-interest magazines, such as Woodsmith and Cuisine at Home] is a great example of a broad view of publishing. Don Peschke [the publisher] repurposes his content with great vision. I’m impressed by Utne and Mother Earth News. Their particular niche is literate and concerned people—not a bad niche to attract. None of these guys is pretentious. They cultivate and take care of their readership. And they’ll survive. They respect their readers, and that may be what it comes down to—respecting your readers and the people who pay you.

Next step: Go subscribe to the Bo Sacks newsletter.

September 16, 2015

Back to Basics: Writing a Novel Synopsis

Photo by reamyde / Flickr

Note from Jane: The following post is an old favorite; I’ve updated it to be more specific and useful.

It’s probably the single most despised document you might be asked to prepare: the synopsis. The synopsis is sometimes required because an agent or publisher wants to see, from beginning to end, what happens in your story. Thus, the synopsis must convey a book’s entire narrative arc. It shows what happens and who changes, and it has to reveal the ending.

Don’t confuse the synopsis with sales copy—the kind of material that might appear on your back cover or in an Amazon description. You’re not writing a punchy marketing piece for readers that builds excitement. It’s not an editorial about your book.

Unfortunately, there is no single “right” way to write a synopsis. You’ll find conflicting advice about the appropriate length, which makes it rather confusing territory for new writers especially. However, I recommend keeping it short, or at least starting short. Write a one-page synopsis—about 500-600 words, single spaced—and use that as your default, unless the submission guidelines ask for something longer. Most agents/editors will not be interested in a synopsis longer than a few pages.

While this post is geared toward writers of fiction, the same principles can be applied to memoir and other narrative nonfiction works.

Why the novel synopsis is important to agents and editors

The synopsis ensures character actions and motivations are realistic and make sense. A synopsis will reveal any big problems in your story—e.g., the whole thing was a dream, ridiculous acts of god, a genre romance ending in divorce. A synopsis will reveal plot flaws, serious gaps in character motivation, or a lack of structure. A synopsis also can reveal how fresh your story is; if there’s nothing surprising or unique, your manuscript may not get read.

The good news: Some agents hate synopses and never read them; this is more typical for agents who represent literary work. Either way, agents usually aren’t expecting a work of art. You can impress with lean, clean, powerful language (Miss Snark recommends “energy and vitality”).

Synopses should usually be written in active voice, third person, present tense (even if your novel is written in first person).

What the novel synopsis must accomplish

First, you need to tell the story of what characters we’ll care about, which includes the protagonist. Generally you’ll write the synopsis with your protagonist as the focus, and show what’s at stake for her.

Second, we need a clear idea of the core conflict for the protagonist, what’s driving that conflict, and how the protagonist succeeds or fails in dealing with that conflict.

Finally, we need to understand how that conflict is resolved and how the protagonist’s situation, both internally and externally, has changed.

If you cover those three things, that won’t leave you much time for detail. You won’t be able to mention all the characters or events. You’ll probably leave out some subplots, and some of the minor plot twists and turns. You can’t summarize each scene or even every chapter, and some aspects of your story will have to be broadly generalized so as to avoid detailing a series of events or interactions that don’t materially affect the story’s outcome.

To decide what characters deserve space in the synopsis, you need to look at their role in generating conflict for the protagonist, or otherwise assisting the protagonist. We need to see how they enter the story, the quality of their relationship to the protagonist, and how they might change, too.

A good rule of thumb for determining what stays and what goes: If the ending wouldn’t make sense without the character or plot point being mentioned, then it belongs in the synopsis. If the character or plot point comes up repeatedly throughout the story, and increases the tension or complication each time, then it definitely belongs.

The most common novel synopsis mistake

Don’t make the mistake of thinking the synopsis just details the plot. That will end up reading like a very mechanical account of your story, and won’t offer any depth or texture; it will read like a story without any emotion.

Think what it would sound like if you summarized a football game by saying. “Well, the Patriots scored. And then the Giants scored. Then the Patriots scored twice in a row.” That’s sterile and doesn’t give us the meaning behind how events are unfolding. Instead, you would say something like, “The Patriots scored a touchdown after more than one hour of a no-score game, and the underdog of the team led the play. The crowd went wild.”

The secret to a great novel synopsis

A synopsis includes the characters’ FEELINGS and EMOTIONS. That means it should not read like a mechanic’s manual to your novel’s plot. You must include both story advancement and color.

Incident (Story Advancement) + Reaction (Color) = Decision (Story Advancement)

Common novel synopsis pitfalls

Don’t get bogged down with the specifics of character names. Stick to the basics. Use the name of your main characters, but if a waitress enters the story only briefly, call her “the waitress.” Don’t say “Bonnie, the boisterous waitress who calls everyone hon and works seven days a week.” That’s a huge and unnecessary tangent. When you do mention specific character names, it’s common to put the name in caps in the first instance, so it’s easy for agents or editors to see at a glance who the key figures are.

Don’t spend any time in the synopsis explicitly explaining or deconstructing the themes the story may address. This synopsis tells the story; it doesn’t try to interpret what it means. (But it does tell us the characters’ feelings or reactions.)

Avoid character backstory. A phrase or two is plenty to indicate a character’s background; you should only reference it when it effects how events unfold. This may mean, if you’ve written a story with flashbacks, you probably won’t include much, if any, of that in the synopsis. However, if the flashbacks are really about what happens in the book rather than why something happens, then they may belong in your synopsis.

Avoid including dialogue, and if you do, be sparing. Make sure the dialogue you include is absolutely iconic of the character or represents a linchpin moment in the book.

Don’t ask rhetorical or unanswered questions. Remember, your goal here isn’t to entice a reader.

Don’t split your synopsis into sections, or label the different plot points. In rare cases, there might be a reason to have subheads in the synopsis, due to a unique narrative structure, but try to avoid sectioning out the story in any way, or listing a cast of characters upfront, as if you were writing a play.

While your synopsis will reflect your ability to write, it’s not the place to get pretty with your prose. That means you should leave out any lyrical descriptions or attempts to impress through poetic description. You really can’t take the time to show things in your synopsis. You really have to tell, and sometimes this is confusing to writers who’ve been told for years to “show don’t tell.” For example, it’s OK to just come out and say your main character is a “hopeless romantic” rather than trying to show it.

How to avoid novel synopsis wordiness

Synopsis language has to be very stripped down. Here’s an example of what I mean.

Very Wordy

At work, Elizabeth searches for Peter all over the office and finally finds him in the supply room, where she tells him she resents the remarks he made about her in the staff meeting.

Tight

At work, Elizabeth confronts Peter about his remarks at the staff meeting.

How to start your novel synopsis

Identify your protagonist, the protagonist’s conflict, and the setting by the end of the first paragraph. Then you’ll have to decide which major plot turns/conflicts must be conveyed for everything to make sense, and which characters must be mentioned. (You should not mention all of them.) Think about your genre’s “formula,” if there is one, and be sure to include all major turning points associated with that formula. The ending paragraph must show how major conflicts are resolved—yes, you have to reveal the ending! No exceptions.

Additional resources

How to Write a Synopsis of Your Novel (one of the best advice articles I’ve seen)

How to Write a 1-Page Synopsis

The Anatomy of a Short Synopsis

How to Write a Synopsis Without Losing Your Mind

The Synopsis: What It Is, What It Isn’t, and How to Write It

More than 100 synopses are critiqued at the Miss Snark archive on synopses writing (great critiques by a very experienced literary agent).

I also offer a synopsis critique service.

September 14, 2015

The State of the Publishing Industry in 5 Charts

Preface from Jane: Last week, I quietly launched a new publication for authors, The Hot Sheet, in partnership with Porter Anderson. It’s a 2x/month email newsletter that helps you better understand what’s happening in the publishing industry without having to read a dozen different sites, blogs, or message boards. Find out more about The Hot Sheet.

Over on my Pinterest account, I keep tabs on data, charts, and infographics related to the media industry—and every so often, I reflect on what the most recent stats are telling us. (My last roundup was in March 2014.)

Here are the most interesting charts to me right now.

Source: At the most recent Digital Book World, Jonathan Nowell of Nielsen presented a look at print book sales from 2004–2014. This slide in particular focuses on nonfiction categories.

Takeaway: It’s stated right on the slide—the decline in nonfiction print book sales pre-dates ebooks. Meaning: The Internet has slowly been eating away at the market for information delivered through the print book, particularly reference and travel. Probably no surprise there for those inside the industry, but some authors keep pitching nonfiction books as if it were 2007, rather than 2014. On the bright side, Nowell’s presentation showed print sales increases in the categories of religion and cookbooks.

Source: This is from the same Nielsen presentation as the previous chart, only focused on print fiction sales.

Takeaway: Ebooks have affected the print sales market for all fiction categories. The genres most severely affected: fantasy, general fiction, mystery/detective.

However, Nowell took time to point out that—across three of the biggest bestselling authors from 2008–2014—ebook sales have increased their overall sales, rather than cannibalizing sales.

Side note: If you’re curious whether any charts showed growth, rather than a decline, then juvenile sales are way up. Click here to see the full presentation.

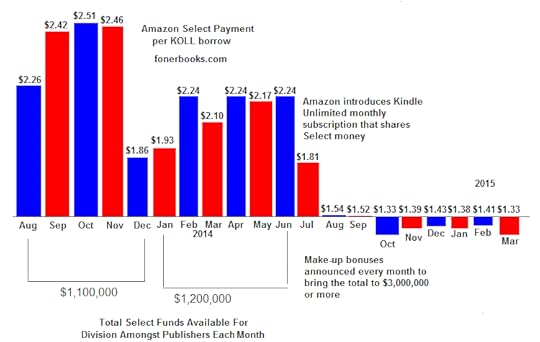

Source: Foner Books put together this visual based on Amazon KDP Select payments to indie authors for book borrows before and after the debut of Kindle Unlimited, the all-you-can-eat ebook subscription service offered by Amazon.

Takeaway: The last year has hinted that the ebook subscription model is experiencing some strain. This graph shows how Amazon payouts dropped in conjunction with the rollout of Kindle Unlimited, which obviously forced Amazon to change their payments to a pages-read model over summer 2015.

Almost without exception, Big Five (New York) publisher titles are not included in Kindle Unlimited, but some of their titles are included in ebook subscription competitors Oyster and Scribd. Scribd has had to reduce the number of romance titles available (due to the voracious reader demographic of that genre), as well as limit the number of audiobooks a subscriber can borrow under their basic plan.

Scribd and Oyster continue to pay on a full royalty model, meaning authors receive the same royalty for a borrow as they do a sale. Kindle Unlimited also pays on a full royalty model—but not for books available via KDP Select.

More than a few people are asking how long ebook subscription models can pay a full royalty—since greater success in engaging users/subscribers means costs can outpace revenue.

Source: From Statista, this graph shows shipments of e-book readers worldwide from 2008–2012 in millions of units, and offers a forecast until 2016.

Takeaway: Current wisdom is that people are moving to tablets/phones for reading, and that’s where ebooks will be primarily read. People inclined to use e-readers already have one, and the technology isn’t advancing in such a way that people are compelled to buy a new e-reader like they are a new phone or tablet. WSJ’s The Rise of Phone Reading expands on this trend.

Source: This is from Nielsen’s deep dive into the children’s market in 2014: children are reading ebooks at a younger age. (Nielsen is about to release a new report this week—follow #kidsbooksummit for reports.)

Takeaway: When you pair this chart with other studies showing that most kids use smart phones and tablets, one wonders when we’ll see corresponding growth in the juvenile ebook market. So far, juvenile ebook sales lag behind adult ebook sales by a significant margin.

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to take a look at my new publication, The Hot Sheet.

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to take a look at my new publication, The Hot Sheet.

Do you have interesting charts or graphs to share about what’s happening in the publishing industry? Share in the comments.

September 11, 2015

The Value of Agent-Assisted Self-Publishing

Last year, I wrote a feature article for Writer’s Digest magazine that explored the intersection of literary agents and self-publishing. I researched how literary agents are helping their established clients who self-publish, as well as when or how they offer services to new authors whose work doesn’t find a traditional publisher. I also addressed how authors benefit (or not) by having an agent help them.

Before self-publishing with an agent’s assistance, ask the following questions:

Who covers the costs associated with self-publishing? In most cases, the author covers the cost, but sometimes the agent will cover expenses and deduct them from the author’s earnings.

Who controls rights to the self-published work? (It should be the author.)

How long must you commit to giving the agent 15 percent of sales on the work? (It shouldn’t be indefinitely.)

How/when can the agreement be terminated?

To learn more about assisted self-publishing with agents, as well as a list of agencies that offer such services, read my full article, now available for free at Writer’s Digest.]

Also related: Agent-Assisted Self-Publishing and the Amazon White Glove Program

September 10, 2015

Taking the Risk to Write Deeply About Your Family History

Note from Jane: This fall, I’m delighted to be offering a 10-week course on writing about your family, taught by writer and professor Benjamin Vogt. Benjamin has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, an MFA from Ohio State University, and has taught nearly 60 English classes while receiving four awards for his work with students. Benjamin’s writing has appeared in over 50 publications, such as Creative Nonfiction, Orion, and The Sun, as well as in eight anthologies, including The Tallgrass Prairie Reader (University of Iowa Press).

For years I’ve been working to discover my life. Wait. I mean writing a memoir. Wait. I mean researching where I come from and who I carry with me. Lots of recent research shows that emotional and other psychological trauma can be passed on genetically to future generations; if these experiences can be passed on, what others might linger in my blood or color the way I act or think or perceive the world? Who am I?

I spent the first ten years of my life in Oklahoma, and every time we went back to visit family after moving to Minnesota, it was complete gut-wrenching torture. As soon as we crossed the border from Kansas, the soil turned red and my heart sank. For most of my life I hated Oklahoma and the small town I came from, filled with old people and old stories and backwater tendencies. When we unearthed thousands of photos cleaning out my grandmother’s house in my twenties, I suddenly realized how little I knew about myself, how important it was to know where I was from, how much I’d want to know as I got older but was quickly losing. I hoarded black-and-white pictures of people and places no one recognized, each one an ember I would stoke. It took years after my grandmother’s passing for me to leap into Oklahoma like she had always wanted, to discover just how wonderfully complicated that home was, and how to honor a past (and myself) that I misunderstood.

It was not and still is not an easy journey, and it took all sorts of research to develop stories that opened up the well of writing within me. I also have had to come to terms with the fact that what I’m writing will upset some people—exploring how my ancestors helped destroy other cultures, from Native Americans to prairie wildlife, is an essential part of honestly and authentically knowing who we are and living better lives. Bravery, and a better story, comes with research.

Prairie dogs

I interviewed my great aunts and learned about farm life—making sausages with pig intestines, Sunday ice cream socials, a chivaree gone bad after chickens were let loose in a house, how each windmill has a distinct voice. I heard the story of my grandmother, who as a child witnessed the spirit of her own grandmother lift up through the bedroom floor on out the window late one night when she passed away. I got tours of various homesteads, walked fields where I cried and touched the same rusted barn light switches my family once touched.

I visited regional libraries and churches to learn about my Mennonite heritage, the persecution of Mennonites in Europe, their immigration and integration into American culture. I discovered that a fire had destroyed the church record book, the genealogy for many families dating back centuries, except for those few pages that held my family’s history. I now know who “died of diarrhea” in the 1700s.

I read one hundred books on Mennonites, prairie, wildlife, Oklahoma’s cultural history, outlaw gangs, oil, Native Americans, Custer’s attack on a Cheyenne village (where peace chief Black Kettle’s body floated down the same creek my grandmother was baptized in decades later).

I walked Oklahoma’s diverse landscapes, from prairie to sagebrush to mountains buried up to their necks, to salt flats and bat caves and hills shimmering with crystals. It took my breath away. These travels even helped my marriage, sharing those spaces with my wife, learning about my past together.

Glass Mountains

And when I began putting it all together I discovered my story in the stories of complete strangers, related or not. I found the story of our country and the Great Plains I’ve called home most of my life. I’m still finding the stories as I bear witness through language, a language that time fades and warps and twists until truth is a strange, exhilarated mingling of fact and fiction; such a mingling defines who we are when we take the great risk to look deeply at our lives.

Learn more about Benjamin’s 10-week course, All in the Family, starting September 28.

September 9, 2015

5 On: Allyson Rudolph

In this 5 On interview, Allyson Rudolph (@allysonrudolph) discusses some of her favorite experimental fiction, the day-to-day life of an associate editor at a publishing house, common problems she sees in fiction and nonfiction, her commitment to increased diversity in media and the arts, and more.

Allyson Rudolph is associate editor at The Overlook Press, where she acquires an eclectic mix of fiction and nonfiction. Before joining Overlook, she worked at Grand Central Publishing, Hyperion, and various academic and association presses in Washington, DC.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: You co-founded, with Meredith Haggerty, the League of Assistant Editors Tumblr to help connect young (but not new) agents and editors. As a (twenty-nine? thirty?)-year-old associate editor at a traditional publishing house, you already have a long history of working as an editor. What fueled your passion for editing or the publishing business in general? When you were in high school, were you an avid reader, or were you more interested in working on the yearbook or the school newspaper (for example)?

ALLYSON RUDOLPH: Twenty-nine! For now.

I didn’t notice until after I got into publishing that I’ve been editing—or at least working with writers and readers on their writing and reading—for most of my life. In elementary school I was a reading buddy for English language learners. I was on the newspaper in middle school and became the managing editor of my high school newspaper as a sophomore. (There were no juniors and seniors at my school at the time—long story—so that’s not as impressive as it sounds.) I line-edited my peers in that position and learned a lot about how to tell someone, sensitively, that their modifiers are dangling. In college I was a paid writing tutor at my school’s award-winning writers’ center; some of my frequent “clients” from that center still send me work they want feedback on, and one sent me flowers when I graduated, which is just the nicest feeling.

I loved working with students whose high schools hadn’t prepared them well for college-level writing—I watched one kid’s grades go from Cs to As after we had a big “what’s a thesis statement” conversation. No one had taken the time to tell him that college essays revolve around a set of structural (and cultural) expectations, and it seemed insane that I’d be the person to help him unlock that, but I was. What a privilege, right?

I was also an annoyingly avid reader. I was not the most social kid (see above, on dangling modifiers) and my favorite childhood activities were reading and daydreaming on the swing set in the backyard. And I was raised by two great, diverse readers who kept me in books and who were able to guide me to appropriate adult reading when I’d bled the kids’ and YA sections of my library dry.

Despite all that, it never once occurred to me, until I was already working in publishing, that I could or should pursue editing as a career. I was never curious about how the books I loved were made until I found myself, quite unintentionally, working in the industry. But, like, not on books anyone read voluntarily. And not as an editor. It took years and years before I began acquiring and editing books that will appear in bookstores.

Among the manuscripts you’ve edited, what kind of work do most of them need? Is there a popular problem area for writers?

This is such a good question!

So, first: to a large extent, I get to pick what I’m working on. Most of the writing I work with is already very, very good—or at least I think it is—or I wouldn’t be editing it. There are certain problems I know I am not good at editing, and so I tend not to pursue projects that have, for example, clunky dialogue. Or clunky sentence-level writing, in general, for fiction.

There are a number of things, though, especially in fiction, that I find myself commenting on over and over. Unearned emotion is a big pet peeve for me—if your main character is going to have a breakdown, or agonize over something for years, or change the whole course of her life because of some Thing that happened to her, that Thing needs to have the same weight as the concomitant breakdown/agony/life-change. Or, the character needs to be written so the reader believes she would react in an outsized way.

I also comment a lot on pacing, in fiction. I feel strongly that my role as a fiction editor isn’t to tell writers that they’re right or wrong. I’m more like a professional reader, with fiction—my goal is to share my reactions to the book I’m reading, as I’m reacting. When action is starting to drag, I’ll note that. If things seem to be moving extra fast, I’ll note that. Sometimes I have ideas about how to edit things to address my concerns, sometimes I’m just saying “this feels weird to me.”

With nonfiction, I’m obsessive about logic and argument structure. I think nonfiction writers are often inclined to jam everything they know or have found, every quote, every tidbit, onto their pages. I spend a lot of ink asking, “Is this point doing work for you? Is it pulling its weight? What is it contributing to the argument you’re making?” If it’s not germane, I want it gone.

I’m also a tyrant about pronouns and specificity in nonfiction. If you are using a pronoun, I need to know right away what it refers to. Don’t make me guess. On any given page of a nonfiction edit, I’ve usually circled a handful of pronouns and written “Who?” or “What?”

Your bio lists experimental fiction as one of your interests. Do you mean reading it or writing it, and what author would you immediately point to if someone new to reading experimental fiction wanted a good example of it?