Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 334

July 16, 2015

Robin Rhode’s Borne Frieze

The first thing you notice when you walk into Lehmann Maupin Gallery in Chelsea, New York, is a traditional white cube room, with a desk close to the window facing 22nd Street, where the art gallery’s requisite pretty young woman is seated. But then, the rest is unexpected: the large, east-facing wall, where the most audience-friendly work would usually be installed, is one of Robin Rhode’s more challenging pieces: a life-sized stencil-sprayed skeleton is suspended on the wall, its arms raised high like a Christ figure, or on the way to position itself in a “Don’t shoot, I’m unarmed” pose familiar to any American. Threaded along each bony arm is a row of stencilled wire hangers, where observers can attach any projected costume they wish to: this skeletal structure will be the most long-lasting trace we leave when we depart life, but of course, we play hide-and-seek with the fact of our mortality, clothing it in various guises. A spool of actual black barbed wire, its thorny length and jagged hooks curling across the length of the gallery’s wall, is fixed above the skeleton stenciled skull – it is Christ’s crown of thorns, deconstructed.

Borne Frieze is a play on the popular moniker “born free”, used to denote the generation of South Africans born into, or who came of age after the first democratic elections in 1994. The gallery’s publicity material states that the artist builds on his love for “visual and verbal puns”, and that:

Borne Frieze creates a bridge between the political heritage of his home country and the energy, spontaneity, and ephemerality of his artistic practice, which has long included the wall drawing as a key form. By bringing an object, idea, or action forth (borne) to a medium central to Rhode’s practice such as the wall (frieze), the artist evokes the improvisational and vibrant nature of his work.

However, rather than uncritically “imbuing his work with a sense of freedom and change that is evocative of this time,” Rhode is also exploring contradictions: the ways in which the art market and commercial art fairs (like Frieze) offer opportunity, yet entrap artists as part of capitalist production. He may also be commenting on the limited mobility to which the majority of South Africans have access, the barbed wire surrounding that perceived freedom into which he and his generation were born, the weight of the high expectations they must bear, the impossibility of moving forward given the socio-economic conditions they face, and the small windows, open high above, through which a few may escape into the dark night.

In the adjoining room, Rhode has included white chalk drawings of bicycles – playful figures of mechanical (yet animated) objects, some of which show movement and mobility – on walls painted in a light-absorbing matte-black paint. His characteristic use of minimal strokes, and the “speed lines” used to show that the bikes are in motion, reminded me of the Russian futurist artist Natalia Goncharova’s Cyclist, which exhibited her similar fascination with dynamic movement of machinery and the restless pace of urban modernity. In Rhodes’ work, the bicycles are devoid of a human figure, and the mobility they offer is limited: a small screen shows video of him rolling a painted bike around the circumference of the smaller second room of the gallery, leaving a chalk-white line on the black floor – evocative of chalk lines used to denote the position of a body after a violent crime has taken place.

The evocation of a crime is stressed by strewn pages of The New York Times in four different spots in the room. The June 19, 2015 front-page headline announces news of the murders at a historic black church in North Carolina at the hands of a white supremacist – who, himself, evoked Rhodesian and apartheid South African white supremacists as his inspiration. On each front page, Rhode has placed a pair of shoes, spray painted them, and left the ghost of their presence. The hightops that left that trace on three of The New York Times front pages are still present on the Times‘ pages near the south-facing wall, waiting. Next to them, the can of spray paint he used. Positioned above some of the chalk drawings of bikes are white frames of awning windows – the kind that are usually installed high on walls of rooms that are almost below ground-level. Rhode has left the awnings wide open, as if to invite us to sneak out, or for a lover to sneak in. From the third room, where The Moon is Asleep is playing on a continuous, ethereal loop, I hear the voice of a poet, calling out in a restless night, calling out to such a lost love, and finally, resigning to hope lost: “The moon,” he says, “is asleep.”

Another room, also painted completely in black, contains massive sculptures of two lightbulbs – one in chalk, another in charcoal. The lightbulbs lie on the ground, amidst sprawling spools of rope. A strobe light flickers on and off above, lighting the scene momentarily: sometimes we see the bulbs, sometimes they sit in the dark, silent obstacles liable to trip us.

In the video showing Rhode at work, he moves the bike awkwardly and stiffly. The artist labours to push it, willing the wheels – immobilised, perhaps, by the white paint used to blanket it – to roll. It’s a trick bike that promises movement, but is “tricked out” not to make it faster or more stylish, but to hinder progress. The non-present potential rider of this bike won’t get far, though observers may point to the vehicle, and say, “But you had a bike. Why didn’t you get anywhere?” The moon, we know, is fickle; sometimes, it dozes off, and disappears altogether. Some things that appear to be chances and opportunities only wink at us with tempting possibility, only to leave us empty. And this mortality, this game that claims to offer us liberty and yet hobbles us, this illusion of freedom within sweet-sour entrapment, is all that we may have left to make us peddle from one day to the next.

Robin Rhode is also showing work at at the Drawing Center in NYC, from July 16 to Aug 30. He is represented by Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg in South Africa, and Lehmann Maupin in NYC.

His first solo exhibition, Recycled Matter, short films where French performer Jean-Baptiste André “mimes his journey through a range of wall-drawn and theatrical environments, interacting with props and sculptural elements that are remnants of previous artworks taken from Rhode’s studio” was shown at Stevenson, Johannesburg earlier this year.

July 15, 2015

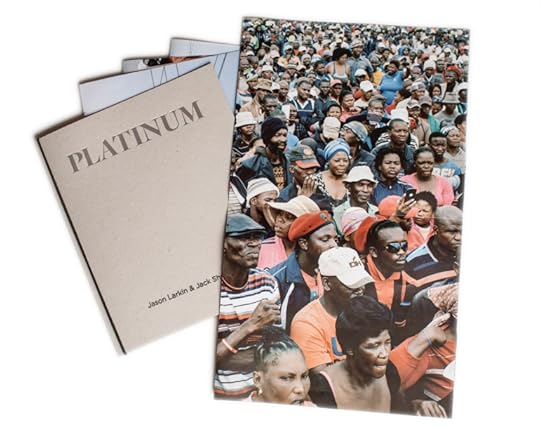

PLATINUM: Public expressions of waiting with patience and pangas

On 27 June, I went to check out the launch of PLATINUM, a mini-publication by photographer Jason Larkin and writer Jack Shenker. It’s a combination of large format posters and “an incisive, wide-ranging essay”, the combination of which explores “the build up to and implications of one of the most critical events in South Africa’s recent history.”

The timing was interesting. I got the launch invite on the same day as the surprise announcement that the President would be releasing the Marikana report. This happened a few days after the most recent of his “injudicious comments”, in which he stunned students at the Tshwane University of Technology when he said that the striking miners had been killers before they were shot on 16 August 2012, referring to the killing of 10 people ahead of the police-led massacre. While it’s crazy that he addressed the students on the deaths of the miners as families were still waiting for the Farlam Commission’s report, even more outlandish was this comment: “Do not use violence to express yourselves, or I might be forced to relook at the apartheid laws that used violence to suppress people.” Haai man. Either he was riling the crowd in preparation for the report’s release (naturally, Julius Malema had to express that he is “flabbergasted” by these comments) or it was just plain irresponsibility that led Zuma, once again, to be in contravention of expected presidential decorum. Both are plausible options I guess, but I digress.

I had wanted to check out the new Fourth Wall Books space in Braamfontein— the company publishes beautifully designed and written books on art, architecture and photography—so I braved the cold and the hit the streets. I could not find parking anywhere and was confused by the queue snaking down and around Smit Street outside AREA3. Turns out it was the launch of Adidas’ YEEZY BOOST 350. Adidas was kind enough to even the playing field in the race to attain a pair by allowing customers the chance to win tickets to buy the exclusive new shoe, and people obligingly lined up to get raffle tickets.

Ironically enough, the book launch got underway with talk of queues. After a welcome by the editor, Bronywn Law-Viljoen, the photographer Jason Larkin (British, internationally recognized for his long-term social documentary projects, lived in Johannesburg from 2011-2013) discussed how what most struck him about his time developing this work was the sheer power behind numbers of people, queuing to affect change. He described the incongruence of pylons and power lines of people, queuing to march and to work, queuing for electricity and for water. There seemed to be some romantic attachment to this image of thousands lined up; I got the impression of a latent wistfulness for a magical shot reminiscent of those first-ever-election photographs. Ja ne foreign photographers huh?

Luckily I had seen another one of his photo series, called Waiting, motivated by “an ever-present sense of people waiting: waiting for jobs, waiting for opportunities, waiting for politics to effect change.” Having this insight into his greater body of work, I appreciated how these sentiments were transposed into the capturing of unconventional Marikana moments—his images of literal public expressions of waiting with patience and pangas. Again, those ever present pylons powering mines in areas where communities have no electricity: somehow, those inaccessible power lines seem to be in tune with the suspended sense of anxiety hovering over the mines, and the nation.

Electricity pylons surrounding the Lonmin platinum mine, Marikana

That this photographer conveys anxiety and palpable violence with subtlety is something I can empathize with, and more seriously, appreciate for not being too graphic. Blame this on police brutality fatigue; it is certainly overwhelming to be constantly and visually reminded of the tragedy and horror and bloodshed that I have now come to associate with the mines.

The series is worth engaging with for the simple fact that it displays in pictures the suspense of suspended development in the platinum industry. The faces of people stuck in these time warp spaces are vast, and with hundreds of expressions on a single A4 sized print, reminiscent of trick collages I remember seeing in a magazine where you had to squint to see the hidden graphics. In this case, I would guess that the hidden visual here is the hypothetical shadow hanging over the mining families’ futures.

This brings me to the publication style itself and the idea of “breaking with traditional format”. The photos are displayed back to back on four posters, neatly tucked into a cardboard cover with the essay printed in a little booklet in the middle. My companion, brimming with sarcasm, was like, “Ya, because everyone wants to put up a poster of the marching miners on their wall.” Miners would totally make the best magazine centerfold, said no one ever. The novelty is cool, but I eye-rolled a bit at the R150 price tag. Luckily, it turns out that they have 500 copies for sale and 500 for free for communities in the Marikana area. That’s cool, and reason enough for me to have purchased one. It usually irks me when foreign correspondents produce and disseminate their best work amongst people who will never get to consume it, poverty porn blah blah, but this is a notable exception. The essay is available in English and Xhosa, and given that the cost of translation is one of the biggest expenses in the publication cycle, this a commendable gold-star was what got me like YASSSS Fourth Wall Books, I’m so down with you for this.

Speaking at the launch was Chris Molebatsi from the Marikana community and David van Wyk from the Bench Marks Foundation. Their description of life in Marikana right now, discussion about the issues faced in the aftermath of the massacre, and the insights given into the relationship between mine management and miners and the greater communities surrounding them, was quite eye-opening. How crazy is this: apparently Lonmin’s response to supporting the widows of the slain miners has been to house them in hostels and employ them, thus preventing them from talking to the media. That made me think about the phrase “corporate social responsibility” in a whole new light. While lives have not changed much in the three years since the massacre, the political space has opened drastically, communities are mobilizing, and trying alternate methods of engagement with both mines and government on a variety of issues ranging from environmental issues to women’s rights.

The essay introducing the images, by writer Jack Shenker, is wide-ranging, peppered with details about the lives of real characters like music-loving Thembisa who works in her aunt’s shebeen in Nkaneng settlement, and Lungisile, a Lonmin rock drill operator who was gifted with a limp and a bullet in the brain courtesy of the SAPS. It is too dangerous to de-lodge it from his skull; he now has to live with the threat of it imploding for the rest of his life. And he’s one of the lucky ones to have lived – he missed his colleague’s funerals during his post-Marikana months in hospital.

Shenker is comprehensive in his descriptions of the area, the people and the political framework that gave rise to the events. The essay concentrates on the boundaries between material corporate interests, responsible policing and “the co-dependent comfort zone of economic privilege that has benefitted a narrow strata of the new South Africa and excluded the majority.” This analysis is not exactly incisive or groundbreaking, but valid nonetheless because of the importance of reiterating questions that arise from accepting life-as-we-know-it. As Catherine Kennedy, director of the South African History Archive, notes, “as a species we are teleological – we make sense of ourselves, and the world around us, through storytelling”; she proposes that Marikana forces us to ask who wrote our rainbow nation’s epically romantic democratic transformation, and how much of it is true.

The real value of Shenker’s essay, however, is how succinctly it locates the massacre into broader neoliberalism-discontent discourse. After Pinochet’s Chile and Thatcher’s Britain, he suggests, “neoliberalism has undergone a process of democracy-proofing that reached its zenith in South Africa.” No longer a theory or ideology, it has come to be an “uncontested reality” leading to the “hollowing out of government sovereignty in neoliberal states, so that popular demands for social justice become impossible to implement.” Tracing the progress of direct imperialism, colonialism and racial domination to how “liberation as political, social and economic empowerment for the masses had morphed into liberation for market forces” is invaluable, and cannot be stressed enough. In this global context, disappointment with the ruling party is somehow mitigated by the reality that “the consequence of South Africa’s neoliberal turn was that democratic freedom, even as it was being feted across the planet, arrived with enough manacles to preclude any meaningful opportunity.”

But what now? If South Africa is living out “the rational destiny of market fundamentalism”, with its prerequisites of gross inequality and mass murder, what is the next step when “democracy gets filtered through the prism of neoliberalism?” Shenker tracks “The Rise of the Marikanas”, focusing on the potential of determined workers movements, with the triumph of the 2014 AMCU wage strike (where workers successfully reached the R12 500 salary demand) as an illustration of just how important victory can be – “because it will affect whether other workers have the confidence to challenge the mass inequality and injustice that exists in South Africa.”

Amidst the shock, horror and trauma of the political developments on the platinum belt, Shanker’s viewpoint is a take on things that I hold in high esteem. Too often, the manifestation of a struggle is hyped up more than the potential it holds and Shenker is right on the money for pointing out that while the rash of revolts sparked after Marikana are not (yet) united, the anti-apartheid protests were similarly fragmented before knotting together as a popular movement that hauled down the system from within. The essay ends with perhaps one of the greatest takes on the trauma that was Marikana:

Perhaps South Africa, in a manner few could have predicted when apartheid came to an end more than twenty years ago, may yet prove to be an inspiration far beyond its borders once again.

It stands to reason that if South Africans once overturned an obscene system of entrenched racism, yet the outcome of that struggle left a bitter taste in the mouths of the masses, then exploitative capitalism may well be the next big thing to be ceremoniously usurped.

*On Thursday July 16th Shenker and Larkin are also launching the publication in London at the Frontline Club, as part of an evening of debate concerning politics, platinum and resistance in contemporary South Africa – see details here.

#RespecTheProducer – Christian Tiger School’s Tapes are made out of Chrome

Sean Magner takes a peek into the world of production duo Christian Tiger School by way of a review of their latest release, Chrome Tapes.This article is part of a series on music producers throughout the African continent called #RespecTheProducer. Check out daily updates on tumblr and follow the Instagram account.

Having emerged from a bedroom of Vredehoek in 2011/2, Christian Tiger School appeared something new and fresh relative to their Cape Town micro-context. Lacing Hip Hop with post-internet/chillwave/blogwave tracks, they had forged a new mould for kids caught up in the new musical intersections being provided by the Internet.

After the release of their debut album Third Floor (Bombaada), Christian Tiger School had already reached a critical mass. Headlining every festival from Durban to Barcelona, the context in which they had emerged was fluid and developing faster than many could keep up with. How, then, do two young Capetonian producers deal with it? Rip it all up and start again is how.

Chrome Tapes is Christian Tiger School’s second album and the first to be released off of New York Label, Tommy Boy Entertainment (De la Soul, Handsome Boy Modelling School). The album is 10 tracks of progressive and immersive electronica. If anything, it’s evidence of a group that understand radical content demands radical form. A group that have finally released something illustrative of their true potential.

Opening track “Mikro Brothers” is a prime example of the new blank canvas. With a sparse gong, we’re welcomed into the world of Christian Tiger School, reimagined. Previous work has also been dense and heady, but the new work exhibits a more mature understanding of aural landscapes where the negative space is as important as the rest. Further progressive tendencies emerge with the inclusion of Okmalumkoolkat. Bringing his unique Zulu-compurra flow on “Damn January”, what we have here is the frontier of both South African music production and South African rap finally converging. It seems almost decades ago that we were crying out amidst the Cape Town electronic music scene: “Where are all the rappers though?”

Personal favourite “Zloz” is a techno behemoth that lumbers and aches over a full six-and-a-half minutes. Deftly accented with a crystalline synth, the track marks the beginning of a progression toward the heart of the album: after segueing through the Fuck Buttons-type seer of “Handmade Mandarin” and the self-referential “Star Search Phezulu”; the epicentre of Chrome Tapes stands tall in all of its resplendent glory. “Chorisolo” raises the tempo to that of the likely heart rate of the dogs in the music video. With a menacing thrust forward, the track erupts into maximalist-yet-refined splendour. The warped vocal track, looped and contorted, is knotted throughout the track and manages to create a hook that is both melancholic and ecstatic.

This part of the album is likely owing to the group’s obsession with dance music and having not listened to that much hip hop in writing the LP. But they haven’t shed their love for hip hop entirely; “Ultimate Frisbee’, “Mikro Kousins” and “Demamp Camp” hark back to the boom bap of tracks past but still manage to reposition the viewfinder forward, incorporating more distinct samples — less murky than on previous releases. While this may signal an opportunity for the group to fall back into their past iterations, “Cinderella Rocafella” is able to provide the perfect concluding chapter. Meeting almost halfway between the progressive electronica and their hip hop roots, the track offers a mission statement over 8 minutes, suggesting the group’s intended trajectory. With a brutal drumline, the track gallops and strides amongst a synth that shines like an expiring supernova only to give way to another, otherworldly, complex creation.

Since Third Floor’s release both Luc Vermeer and Sebastian Zenasi were able to explore their respective musical inclinations and what appeared obvious was that Christian Tiger School were never going to be the same. Too much has happened in the interim. With Seb it was dropping out of UCT Music school and experimenting in other various musical groups like Fever Trails and Yes, in French. Luc further developed his taste for rap, hip hop and everything these genres touch by way of his solo alias, Desert_head. At the same time, the South African music scene over the past three years has welcomed a new wave of rap and hip hop while also seeing its electronic scene blossom and spiral into myriad new avenues.

While their CTS back-catalogue has never really felt basic per se, with the release of their new album Chrome Tapes the contrast is evident, and I don’t think the duo would have it any other way. Chrome Tapes is a bold release, likely to scare off some fans. But it’s nonetheless admirable in its quest for development and progression.

And it’s this progression that was so necessary: Christian Tiger School had routinely become encased in critical cliché: “aural soundscapes”, “LA-Beat-Scene inspired”, etc. It’s all so trite, yet fails to ever recognise what the two producers behind it all are actually doing on their own terms. Chrome Tapes, thankfully is that moment where CTS have owned their creation. They are no longer a sum of their various influences; they’ve transcended stereotype and placed themselves at the new frontier.

* You can stream Chrome Tapes on Deezer or buy on iTunes.

#RespecTheProducer – Christian Tiger Shcool’s Tapes are made out of Chrome

Sean Magner takes a peek into the world of production duo Christian Tiger School by way of a review of their latest release, Chrome Tapes.This article is part of a series on music producers throughout the African continent called #RespecTheProducer. Check out daily updates on tumblr and follow the Instagram account.

Having emerged from a bedroom of Vredehoek in 2011/2, Christian Tiger School appeared something new and fresh relative to their Cape Town micro-context. Lacing Hip Hop with post-internet/chillwave/blogwave tracks, they had forged a new mould for kids caught up in the new musical intersections being provided by the Internet.

After the release of their debut album Third Floor (Bombaada), Christian Tiger School had already reached a critical mass. Headlining every festival from Durban to Barcelona, the context in which they had emerged was fluid and developing faster than many could keep up with. How, then, do two young Capetonian producers deal with it? Rip it all up and start again is how.

Chrome Tapes is Christian Tiger School’s second album and the first to be released off of New York Label, Tommy Boy Entertainment (De la Soul, Handsome Boy Modelling School). The album is 10 tracks of progressive and immersive electronica. If anything, it’s evidence of a group that understand radical content demands radical form. A group that have finally released something illustrative of their true potential.

Opening track “Mikro Brothers” is a prime example of the new blank canvas. With a sparse gong, we’re welcomed into the world of Christian Tiger School, reimagined. Previous work has also been dense and heady, but the new work exhibits a more mature understanding of aural landscapes where the negative space is as important as the rest. Further progressive tendencies emerge with the inclusion of Okmalumkoolkat. Bringing his unique Zulu-compurra flow on “Damn January”, what we have here is the frontier of both South African music production and South African rap finally converging. It seems almost decades ago that we were crying out amidst the Cape Town electronic music scene: “Where are all the rappers though?”

Personal favourite “Zloz” is a techno behemoth that lumbers and aches over a full six-and-a-half minutes. Deftly accented with a crystalline synth, the track marks the beginning of a progression toward the heart of the album: after segueing through the Fuck Buttons-type seer of “Handmade Mandarin” and the self-referential “Star Search Phezulu”; the epicentre of Chrome Tapes stands tall in all of its resplendent glory. “Chorisolo” raises the tempo to that of the likely heart rate of the dogs in the music video. With a menacing thrust forward, the track erupts into maximalist-yet-refined splendour. The warped vocal track, looped and contorted, is knotted throughout the track and manages to create a hook that is both melancholic and ecstatic.

This part of the album is likely owing to the group’s obsession with dance music and having not listened to that much hip hop in writing the LP. But they haven’t shed their love for hip hop entirely; “Ultimate Frisbee’, “Mikro Kousins” and “Demamp Camp” hark back to the boom bap of tracks past but still manage to reposition the viewfinder forward, incorporating more distinct samples — less murky than on previous releases. While this may signal an opportunity for the group to fall back into their past iterations, “Cinderella Rocafella” is able to provide the perfect concluding chapter. Meeting almost halfway between the progressive electronica and their hip hop roots, the track offers a mission statement over 8 minutes, suggesting the group’s intended trajectory. With a brutal drumline, the track gallops and strides amongst a synth that shines like an expiring supernova only to give way to another, otherworldly, complex creation.

Since Third Floor’s release both Luc Vermeer and Sebastian Zenasi were able to explore their respective musical inclinations and what appeared obvious was that Christian Tiger School were never going to be the same. Too much has happened in the interim. With Seb it was dropping out of UCT Music school and experimenting in other various musical groups like Fever Trails and Yes, in French. Luc further developed his taste for rap, hip hop and everything these genres touch by way of his solo alias, Desert_head. At the same time, the South African music scene over the past three years has welcomed a new wave of rap and hip hop while also seeing its electronic scene blossom and spiral into myriad new avenues.

While their CTS back-catalogue has never really felt basic per se, with the release of their new album Chrome Tapes the contrast is evident, and I don’t think the duo would have it any other way. Chrome Tapes is a bold release, likely to scare off some fans. But it’s nonetheless admirable in its quest for development and progression.

And it’s this progression that was so necessary: Christian Tiger School had routinely become encased in critical cliché: “aural soundscapes”, “LA-Beat-Scene inspired”, etc. It’s all so trite, yet fails to ever recognise what the two producers behind it all are actually doing on their own terms. Chrome Tapes, thankfully is that moment where CTS have owned their creation. They are no longer a sum of their various influences; they’ve transcended stereotype and placed themselves at the new frontier.

* You can stream Chrome Tapes on Deezer or buy on iTunes.

July 14, 2015

“El Chapo”‘s (New) Escape

These days the fonda where I usually eat has been packed with Policía Federal officers. The fonda was designated as one of the official restaurants for the troop sent to Oaxaca to contain those who are opposing a reform that would allow a massive teacher layoff. Los Soles is its name, and it’s located just around the corner from the offices of the Truth Commission where I work, so recently I’ve had casual conversations with officers from every part of the country.

While we wait our turn to taste our meals, I like to ask them if they read the crime novels of Élmer Mendoza, or Paco Ignacio Taibo II, or if they watch police TV series like True Detective, or The Killing. None of those who have talked to me know detectives Mendieta, Belascoarán, Cohle, or Holder; but on the other hand I have not seen The Shield, nor El señor de los cielos, the TV series that they always recommend. We also talk about other things, for example, about what they have had to see in their various missions around the country.

This week I was talking to one of these officers about a historical area of Mexicali, created by Chinese immigrants, known as “La Chinesca,” where there is a series of tunnels and underground passageways that connect various local buildings, and that at some point even extended to the nearby city of Calexico, in the United States.

The first time I heard about this place was in 2008, when I was in Culiacán doing some research for my book El cártel de Sinaloa (Grijalbo, 2009). A veteran member of the organization, who had worked during the reign of Miguel Félix Gallardo, told me that the first important job that Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera had was to smuggle marihuana and cocaine into California through Mexicali in the 80s.

According to that informant, El Chapo reactivated the old tunnels in La Chinesca and thus became one of the most efficient drug smugglers of that era. Some said that El Chapo had worked with unusual patience until he created an authentic narco city underneath Mexicali. I always found this tale about La Chinesca, and the topographical genius that later became one of the biggest drug lords in the world, fascinating and cinematographic.

A few months ago, I was also talking about it with Craig Borten, the screenwriter of Dallas Buyers Club, who is writing one of the many Hollywood scripts about the off-center life of El Chapo.

Nonetheless, the story of La Chinesca is very far from what happened this Saturday, July 11th, when, according to the National Security Commissioner, the most important inmate in the Mexican penitential system entered the shower in a maximum security prison and then descended through some secret stairs until he reached a tunnel where a motorcycle was awaiting, which he then used to cover the whole underground distance of the Penal del Altiplano prison, until he arrived into some sort of basement of a modestly built house, where he was finally able to get our and, for the second time, escape his imprisonment.

According to the official report, the tunnel built is 1.5 kilometers long. To give an idea of the engineering feat that this is, Mexico’s largest urban tunnel is 3.5 kilometers long and is being built by Carlos Slim’s companies in Acapulco, Guerrero.

The first obligation of a journalist is to seek out the official version of whatever is that happened, and the second is to not believe in it, until after having researched and contrasted it with other independent sources. Thus, a permanent challenge of Mexican journalism is figuring out what to do with the official fictions that are produced, mainly, on issues related to the world of the narco (as happened with Tlatlaya, Ayotzinapa, the Tec students…).

But beyond this dilemma, and to add to the awe, we can safely establish that El Chapo left the Penal del Altiplano – by whatever methods – just at the same time president Enrique Peña Nieto and ten secretaries form his cabinet, including those of Government, National Defense and Navy, where flying towards Paris.

It is not a coincidence that this evasion happened at the exact moment in which the main eleven official heads were 9,194 kilometers away. Obviously, the operative reaction to try to recapture El Chapo was more chaotic and complicated by this, which could have given him some time to leave the center of the country faster and arrive to a safe dominion.

This not only speaks about the cleverness of the narco boss and of his political operators, but also about a direct challenge to the frivolity and unkemptness of our country’s administration. It is likely that the Secretary of Government, Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, will leave his post after a failure that completely falls under his jurisdiction. But, what will happen with the irresponsible presidential decision to take the whole government to France during almost a week?

The majority of Mexican prisons are ungovernable, or are at least territories where groups of inmates control them as if they were private property. There is the case of the penitentiary of Gómez Palacio, Durango, from where a commando of hitmen got out to execute people in Torreón, Coahuila, and then went back into their cells. Or the one of the municipal jail of Cancún, better known as “Hotel Zeta,” where the gunmen that ended the life of general Enrique Tello were recruited. There is also the case of the jail of Topo Chico in Monterrey, where the recently imprisoned inmates who don’t pay a fee are constantly tortured and get a “Z” tattooed on their butt cheeks.

But, until this weekend, the Altiplano prison was an exception to the rule in this disastrous national statistic.

A few hours after the escape, I phoned Flavio Sosa, social fighter in Oaxaca, who is considered by many human rights organizations to have been the first political prisoner of Felipe Calderón’s government. Sosa participated in a popular revolt and was arrested on December 4th, 2006, and then transferred to the Altiplano prison where, also, he was jailed in the Tratamientos Especiales area, the maximum security zone. There he shared the halls with many drug lords, including Osiel Cárdenas Guillén – before the latter was extradited to the United States. It was there that the inmate Guzmán Loera was imprisoned.

“Do you think somebody can escape the Altiplano without first-level complicities?” I asked him.

“This prison is an unbreakable capsule. And the area where El Chapo was, Tratamientos Especiales, was a capsule inside a capsule. All of the surveillance system must have been relaxed.”

Sosa remembers that in Tratamientos Especiales there were twenty individual cells, divided into two halls. Each one of them is permanently surveilled by video. Inside each cell there is a bunk bed, a cement table and a hole in the ground that is used as a latrine by the inmates, as well as an individual shower, which might discount the version that says that there is a common showering area.

Sosa thinks that the only angle that can be invisible to the camera is the bottom of the bed. He also thinks it is hard to believe that El Chapo would take a shower on a Saturday night, as he says that showers are only permitted at 6 A.M. He also explained to me that there are careful examinations of each cell in this area at least three times a month and that the officers who do it even bang the walls and the floors with a hammer, with the aim of detecting special compartments.

“During one of those tough nights, I thought about how I could get out and I realized that, if I wanted to escape, I would have to agree to it not only with my guards, but also with the other three organisms that are there – the Federales, the jail’s police and a special guard – all of which are under very different bosses, and are usually very distrusting of each other. It was impossible, though it seems in El Chapo’s case, it wasn’t.”

This is what Sosa, who was freed after a year in a half in prison thanks to the social pressure denouncing the unfairness of his arrest, says.

During the time El Chapo was in prison, little was known about the legal process against the Cártel de Sinaloa boss. We only heard anecdotes, like the one from a PAN House member who, it seems, went to visit him, or the one of a letter that he co-signed with other inmates that was addressed to the president of the National Human Rights Commission.

But, in general, the government maintained a suspicious opacity about the enclosure of one of the world’s most persecuted men. Out of those sixteen months he was in jail, now we only know that he escaped. The so-called “arrest of the century” was not followed by a “trial of the century,” in which light could be shed on the political and economical networks used by the boss from Sinaloa to operate. Why?

In the popular reactions in social media, fear and indignation were not the emotions that prevailed after El Chapo’s escape. It seems that his criminal charisma will just increment. Mexico has a plutocrat antihero, whose popularity competes with that of the members of the ruling class.

“The problem is that wherever I go, I realize that people love El Chapo more than Congress members,” said, earnestly, the federal police officer that was talking to me about La Chinesca.

As these and many other questions are answered with time, with my coworkers in Oaxaca we speculate that soon we will be able to eat in Los Soles without having to form a line, because the Secretary of Government (likely by then under the command of Manlio Fabio Beltrones, the Mexican Vladimir Putin) will relocate hundreds of federales who are here, so they can leave the teachers alone and then go look for El Chapo everywhere, even under the earth.

Regarding the cinematographic future of Guzmán Loera, after this second escape, it seems very hard to make an impactful movie based on the “real life” of such a character. The unpunished reality of El Chapo is already a cartoon that has too much literature. Just like the Mexican government has too much corruption.

This article was originally published in the Mexican site / cultural center / caffè-bar Horizontal in Spanish and is translated and republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Follow Horizontal here.

Follow Latin America is a country on twitter and .

Lagos, the city of divides

Lagos, is the only city in Nigeria worthy of being described as a human potpourri. No crevice of the city is left unaffected by the flavour brought by the multifarious peoples who comprise the city’s teeming populace. Whatever beauty or redeemable qualities can be salvaged from the Nigerian contraption can be seen in Lagos. Conversely, also, the inequality and inequity which have come to characterise Nigerian society permeate Lagos. But this mixture of humans is increasingly divided spatially. This has its costs.

Apart from the economic prospects it offers, Lagos has a highly alluring veneer of beauty, culture and sophistication. There’s always something for everyone, or as Madonna sang in the nineties, you only see what your eyes want to see. This is where the successive government regimes in Lagos and the elites within the state share a common interest, apart from the cornering of the state’s largesse: making the ‘’unwanted’’ invisible. Successive governments in the state have been more preoccupied with ‘’beautification’’ projects in public areas than trying to alleviate the living conditions of impoverished families. The famous Lagosian reggae artist, Majek Fashek painted, for me on a personal note, the most resonant comparison of the divide in Lagos when he sang, some decades ago, about his first time visiting the U.S.A. and alighting in the city of New York. Very much like his beloved Lagos, (or ‘Las Gidi’ as he fondly refers to the city as, a portmanteau derived from Las Vegas, to reflect what Majek saw as the many commonalities between Lagos and Las Vegas in terms of the embrace of the culture of hedonism and the existing underbelly of dire poverty and crime masked by the neon lights of artifice) he was befuddled to find that contrary to what he had previously imagined of America as some utopic Shangri-la, it had homeless people on its streets.

This sharp contrast in experiential perspective by the inhabitants of Lagos also has a spatial face to it. The Third Mainland Bridge helps to provide a physical marker to compliment the social barriers already erected in the minds of its denizens. Living on ’’the island’’ in Ikoyi and Lekki is considered preferable to living or mingling on the mainland. Then, a fleeting camaraderie, of sorts, is found in affirming a sense of superiority over those from surrounding states. This behaviour lends strong credence to Paulo Freire’s theorisation in the seminal ‘’The pedagogy of the oppressed’’ that the oppressed not only respect and fear their oppressors but also wish to occupy their position as oppressors in future.

The sad reality, however, is that, regardless of where one lies on the socio-economic spectrum in Lagos, we all suffer to some degree. The have’s, the yet-to become have’s and the have-not’s are unable to avoid the pothole-ridden roads of Lagos. The wealthy or those who cannot afford it pretend they can avoid the roots of the problems plaguing the Nigerian society by papering over the cracks, so we see them buy bigger cars to ply the bad roads only to be accosted by highway robbers. They retreat into their garishly furnished houses but live in constant fear of the outside world, knowing that many around them live in contrasting paupery. That is the cost of the divide. The barrier set up to keep the have-not’s away, to render them invisible so as not to ruin our aesthetic of comfort and ideals of beauty ends up becoming a prison to the wealthy.

It has transformed the socio-cultural landscape of Lagos into a spin-off of the zombie series The Walking Dead, where the rich keep on moving in an almost-peripatetic fashion to areas with higher insularity from the working classes. So the island mainland divide no longer suffices, they retreat to Ikoyi, then to Lekki, then to the ultra-exclusive Banana Island, where a sizeable token fee is charged before non-residents can gain entry to take a look around. The spatial paradox of this is that the divide is in fact a façade because in actuality it is an eliding spectre which try as they might, the moneyed classes cannot escape from.

In Morocco, a judge agrees: #mettre_une_robe_ nest_pas_un_crime

Yesterday, in Inezgane, south of Agadir, on the southern part of Morocco’s Atlantic Ocean coast, a judge decided that two young women were not guilty of… outraging the public through some sort of indecency. Supporters rejoiced. Defense attorney Houcine Bekkar Sbai declared: “I am very pleased with this verdict. This is a victory not only for these two women, but for all members of civil society who mobilized. Extremist thinking is unacceptable and no one can set themselves up as guardians of religion and morals.” Fouzia Assouli, President of the Federation of the League of Women’s Rights, added, “This acquittal is positive and means that wearing this type of clothing is not a crime.”

Now that this trial is over, the two women, constantly referred to as “the girls of Izegane” in the press, have broken their silence: “We have committed no crime or offense, and yet we have been dragged into court, unjustly, in fear and terror, in pain and suffering.”

The judge also found that the police were beyond reproach in this matter. Two women were harassed and terrorized, forced to hide, because of the perception that they were “girls” wearing objectionable clothing, and the police picked them up, held them, and then arrested the two women, and, only after a hue and cry was raised, began looking for and finally arresting men suspected of having harassed and intimidated the two women. And the police acted according to the letter of the law.

Supporters of the two women say the next step is to prosecute those who harassed the two women. Fair enough. What about the police and the letter of the law to which they abided? Supporters and activists have been reduced to arguing that these two women were not provocatively dressed. The next two… well… we’ll see. But for now “the girls of Inezgane” are not going to prison, thanks to the pressure of thousands of women across Morocco, and that is good news.

The Basotho people must have a stake in the production and distribution of their culture

Blankets are to Basotho people a cultural emblem. Our blankets, much like the cow, are central to every rite of passage in our culture; from childbirth to marriage to burial ceremonies and everything else in between. Originally, we made our blankets out of animal hide and furs, adapting them according to the season. In the early 19th century, European woollen blankets were introduced in our lands by traders and missionaries and notably to founding father of the Basotho nation King Moshoeshoe in 1860. These new blankets were infused into our communities and gained relevance as part of our unique heritage.

For generations the love affair we have with blankets has endured. With an elevation of 1400 metres and higher in our tiny Kingdom now known as Lesotho, our blankets are the signature capes we ensconce ourselves in during unforgiving winters and they hang loosely over our shoulders during summer’s tormenting heat. An aesthetic of the people, our politicians and musicians are often seen wrapped in them as they tour our country, seeking to win the hearts of the masses. Blankets for us are a warm blend of style, function and tradition.

But thanks to the capitalist hunger of Europeans in Southern Africa and the rise of industrial technology, people have ascended our mountains to profit from our prized possession. Blanket manufacturer Aranda, producing blankets near Johannesburg, South Africa since 1951, was appointed as the exclusive manufacturer of our heritage blankets in the 1990s. This gives Aranda a near monopoly on the blanket market in Lesotho. Lesotho on the other hand, despite having a relatively large textile industry, has never been able to produce a successful blanket manufacturer locally and yet the blanket is one of our most treasured symbols.

In the fine Western tradition of profiting from other cultures, Sean Shuter, a fashion entrepreneur between New York and Cape Town and a new admirer of the Basotho heritage blankets, recently struck up a deal with the Aranda company to sell their blankets in high-end boutiques around the world. Using photographs of Basotho in their communities — happily donning their prized capes — he will now be the one to tell our blanketed history globally with our people as props in order to market his product and grow his brand. He recently celebrated himself and his discovery on Style.com, boasting enthusiastically about how he learned of the importance of Basotho blankets not from Basotho people, but from the marketing director at Aranda. This is just the latest exoticizing and repackaging of culture by outsiders. It has happened before with Ethiopian, Maasai and Native American styles and it will undoubtedly happen again if we continue to sleep on our cultural wealth.

Photo: Mountain Kingdom

Forward-thinking fashion designers such as Thabo Makhetha have adapted the Seanamarena style (loosely translated as “worn by kings” in Sesotho) blanket for example, into signature coats and other fashionable creations owing to the high quality and intricate patterns of the blankets. Many African designers have embraced Ankara fabric as well. But we as the diviners of culture need to manage more than its relevance, we need a stake in its production. We can choose to recognize the value of our heritage and take control over the distribution of our culture, or we can let the hunters tell the story of how they slayed the beastly lions. When I see someone like Sean Shuter cashing in on my people’s image I’m tempted to cry “cultural appropriation”, but then again, it’s just business I suppose.

July 13, 2015

Kemang Wa Lehulere: History will break your heart

“There still is the demand for black artists to exoticize themselves. The same struggle that Ernest Mancoba was having is still around and oftentimes one does not have to be told to self-exoticize; the mechanisms in which people are shaped into that kind of direction is very sophisticated, but that’s the nature of power itself. I’m very conscious of it. It’s also about refusing the spectacle.”

-Wa Lehulere

Steel structures pulled from worn-out school desks zig-zag across the floor, propping up inverted gumboots with gold soles. Identical busts are placed next to each structure, loosely refereeing to the deeply flawed education system and the Marikana Massacre. The installation is surrounded by paintings from South African art giants Gladys Mgudlandlu and Ernest Mancoba; as well as chalk drawings by his aunt, Sophie Wa Lehulere and a film that documents an ongoing project in Gugulethu.

History will Break your Heart is visual artist Kemang Wa Lehulere’s, latest exhibition. Composed of installations, drawings, video, sculpture and performance, the exhibition is a fractured, layered and deeply personal narrative that recalls the past in order to rethink the present. Wa Lehulere was awarded the prestigious Standard Bank Young Artist Award for 2015.

“I feel like I have to contextualise a few things because people get confused. And of course audiences vary. So we’re not on the same page, all of us. The show is read differently in different cities, according to the audiences and the space.”

Born in Gugulethu and raised by his aunt, Wa Lehuluere has been moving between art and activism and rebelling against the education system since the school bell rang. “My teacher noticed that I was struggling with the curriculum, English in particular, I could not relate to Shakespeare as works of art, they just didn’t speak to me,” he said. “So she began taking books out of the library for me, which is when I started discovering black writers. By the time I arrived at university I was already critical of education as a package, as well as black writers who were erased,” he said.

Wa Lehulere has four solo exhibitions, 50 group exhibitions and six residencies under his belt, in cities such as New York, France, Switzerland and Johannesburg. He’s no stranger but mentions more than once he has come to understand the ‘complexities of what it means to operate in the art world’.

“I’m critically aware of institutional power, the university, the education system, the art world, even Standard Bank Young Artist as an institution so I dance within these things.”

Along with his performing, photographing and filmmaking background Wa Lehulere was also one of the co-founders of Gugulective, a Cape Town based art collective that was established in 2006 to make art accessible in township spaces and allow creatives the space to explore “contemporary art in their urban township context”.

“When we did Gugulective one of my lecturers said, ‘Hey man what the fuck are you guys doing bringing conceptual art to the township? You’re speaking a language people don’t understand’ and I was like what? I mean, the responses I had at Gugulective were the most sophisticated, from an audience that is largely uneducated, they have an incredible ability to read images”.

“There was a performance piece I did where I was digging a hole with an afro-comb in Gugulethu and I discovered these bones, that work I did it again at the KKNK festival in Oudtshoorn and I was almost assaulted for the very same work. When I did this thing in Gugulethu, people thought I was mad, you know digging a hole with an afro comb. In Oudtshoorn, people took on a whole different political meaning, people came at me really angry like, hey fuck you I also want my own land. You know, in Afrikaans. People read it as coming from land politics. I’m still learning about different audiences and it’s not easy”.

History will Break your Heart includes one of the last filmed interviews with Mancoba (1904-2002), one of the first black avant-garde artists in South Africa; as well as Mgudlandlu’s (1925-1979) paintings. She was a self-taught fine artist from the Eastern Cape, whose subject matter includes indigenous birds, rural landscapes and brightly coloured scenes from townships and villages. His work sits alongside theirs, speaking to each other, past and present. “These are artists that have been written out of history. Including them in the exhibition is an act of love,” said Wa Lehulere.

With a range of visual elements from a variety of artists, History will Break your Heart is a fractured collection of work, an intentional approach, which speaks to the nature of South African history.

“Things need to change, it’s 2015. And the change is not about hate towards white people, it’s about saying that we also exist, we’ve been existing, we’re also human beings and both Mancoba and Gladys that’s what they’re fighting for, just a simple desire to be human it’s not about hate, in fact it’s about love. Self-love is very important.”

Follow @KemangWa on Twitter.

#DevPix: 5 things that can’t be ignored about development photography

Since Jorgen Lissner’s searing critique of the use of poverty porn to solicit donations in the wake of the Ethiopian famine, there’s been critical attention paid to the way development organisations use photography.

Guidance has been written; research on the unintended effects of using images that negatively stereotype whole continents has been conducted. And yet – despite this – it’s debatable how much progress has been made. As John Hillary highlighted last year in a follow-up piece from Lissner’s, we might be seeing the return of poverty porn.

On July 9, 2015, the Overseas Development Institute organised a Twitter chat with the hashtag #DevPix (@africasacountry participated) to ask: how can development organisations improve? Here’s five key issues which came up in the discussion.

Showing suffering should be specific

Images used by development organisations are often devoid of context, not even providing so much as a location, nor any details about the person they’re depicting or their life. The underlying message is, then, that the consumers of these images don’t need much information to make out what’s going on: it’s probably Africa, and it’s probably awful.

It’s the approach that Binyavanga Wainana brilliantly sends up in How to Write About Africa: “It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herd of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions.”

@toluogunlesi We must all insist on NGOs using appropriate, contextualising, captions. #DevPix

— Hans Zomer (@Hans_Zomer) July 9, 2015

Captions are important; context is important. What’s actually happening? Who is it, and what are they doing? What’s behind the distress or suffering depicted? Who’s involved?

We need more photos of overhead costs, expat hardship allowances, fortified high security living quarters and competitive benefits. #DevPix

— Amos Odero (@OderoGogni) July 9, 2015

Can #DevPix depict the other side of the story? The exploitation that causes poverty. Let's look at the man in the mirror as MJ put it.

— Minna Salami (@MsAfropolitan) July 9, 2015

Without providing information about the factors driving the problems depicted, development communications both end up marking the global South as a site of rootless, causeless, unavoidable suffering, and tire audiences in the global North who are confused as to why, after so much aid has been given and donations have been solicited, not much has seemingly changed.

Cultivate solidarity, not pity

Images of pity solidify the legacy of colonialism (with which development, and photography, share a sticky history), presenting the global South as an unknown, alien other, in need of saving by benevolent passers-by in the North. If the images used by development organisations make people look subservient, submissive and in need of pity, then the unequal power dynamic between North and South continues: ‘we’ have what ‘you’ need, and (bonus!) it’ll only cost $5 a month.

Basically, I am of the opinion that good #devpix must definitely not appeal to our guilt. People must give out of love, not out of guilt

— Nana Kofi Acquah (@africashowboy) July 9, 2015

It’s about seeing people as equals – something development photography doesn’t exactly excel at.

Ultimately, development is not about YOU & THEM, it is about US & OUR world. When the rain fall it don't fall on one man's house. #DevPix

— Minna Salami (@MsAfropolitan) July 9, 2015

Development organisations should move away from using images that encourage pity in the viewer – and instead use images that inculcate a sense of solidarity.

Best #DevPix show people as political agents, not victims. This creates political solidarity. @c_bracegirdle @ODIdev pic.twitter.com/x43BJkW4aJ

— John Hilary (@jhilary) July 9, 2015

Consent must be meaningful

Consent isn’t just about getting someone to agree to be photographed: it’s also about ensuring that they know how their likeness can be used, and if they’re entirely comfortable with that. On more occasions than I could possibly recall, I’ve used images of people I don’t know doing things I don’t understand to illustrate a document with a very specific list of policy recommendations. I’m not sure how that Sierra Leonean community police officer, those protesting Bolivian women, or those people ambling around Lagos would feel about being the ‘face’ of those messages; I’d feel quite perturbed if an organisation with views divergent from mine used me to illustrate their ideas.

@rich_mallett @ODIdev much more. Take the time to explain all potential results, what others experience, what they think will happen #devpix

— Kate O'Sullivan (@KateOSully) July 9, 2015

#DevPix We equip our researchers with materials like this to show photo subjects how their image could be used. pic.twitter.com/hVh0t1dWJx

— Reboot (@theReboot) July 9, 2015

This dynamic is even more problematic when the fact that a lot of development images are used to solicit funds is taken into consideration. Are the subjects models? Should they get paid? And is anyone comfortable being the ‘face’ of poverty and distress?

Are there any studies where individuals from countries most often portrayed give their opinions on representation? #DevPix @ODIdev @bondngo

— Ruth Taylor (@Ruth_STaylor) July 9, 2015

Giving space for self-representation

Development organisations need to go beyond ‘doing consent well’ – avoiding exploitation is a low bar to set for achievement. Instead, development organisations should be thinking about how the people they depict are involved in image-creation: whether through participatory photo projects, or through the democractisation of content creation that (hopefully) accompanies the growth of social media, there’s options out there to give people the space to represent themselves.

#DevPix A5: Social media has liberated who is behind the lens. This is transformative!

— Liz Eddy (@Liz_EddyDC) July 9, 2015

Why haven’t development organisations got better at incorporating these?

Critically reflect on the industry of poverty-images

Stereotypical images of the global South persist, in part, because local photographers are often overlooked in favour of flying someone in, who most likely knows little about the context. The potential for misrepresentation and erroneous emphasis is rife.

.@ODIdev NGOs SHOULD use local photographers. If you're using local issues to raise money makes plenty sense to involve local talent #DevPix

— tolu ogunlesi (@toluogunlesi) July 9, 2015

But, as some of the participants highlighted, these kinds of narratives can be created by anyone – and it’s not a fair assumption that if you hire someone local, you’ll automatically end up with less biased imagery.

.@ODIdev downside is that often, local photographers conditioned to produce the kinds of images they know/think NGOs love to use #DevPix

— tolu ogunlesi (@toluogunlesi) July 9, 2015

Re #Devpix Q3 "Locals" can perpetuate stereotypes too – c.f. stigmatisation of scrappers in Agbogbloshie (Accra) http://t.co/O7rM8GpnwS

— Janet Gunter (@JanetGunter) July 9, 2015

Indeed, thanks to the efforts of development organisations, the production of images of poverty has become an industry in itself, as Nazia Parvez found in Freetown’s Kroo Bay. As notoriously under-provisioned area, it’s long been subject to the gaze of the documentary photographer and researcher. Today, the people living believe that – as Renzo Marten’s film Enjoy Poverty disturbingly suggests – there’s a market for images of poverty, and it’s something they can sell.

This market potentially ends up distorting the ways in which local photographers, or indeed people living in poverty themselves choose to represent that reality. If NGOs and donors have traditionally wanted a rootless, decontexualised and disempowering kind of image, then it might make sense to give it to them.

—

Though just an hour long, the #DevPix twitter chat proved to be a fruitful discussion for reflecting on the power and pitfalls of development photography, while suggesting resources for doing it better. For a look at the highlights of the chat check out this storify of the conversation: #DevPix: improving how development organisations use photography.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers